University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

WHAT HAPPENS WHEN BOOKS ENTER THE PUBLIC DOMAIN? TESTING COPYRIGHT’S UNDERUSE HYPOTHESIS ACROSS AUSTRALIA, NEW ZEALAND, THE UNITED STATES AND CANADA

JACOB FLYNN,[1] REBECCA GIBLIN[1]** AND FRANÇOIS PETITJEAN[1]***

A key justification for copyright term extension has been that exclusive rights encourage publishers to make older works available (and that, without them, works will be ‘underused’). We empirically test this hypothesis by investigating the availability of ebooks to public libraries across Australia, New Zealand, the United States and Canada. We find that titles are actually less available where they are under copyright, that competition apparently does not deter commercial publishers from investing in older works, and that the existence of exclusive rights is not enough to trigger investment in works with low commercial demand. Further, works are priced much higher when under copyright than when in the public domain. In sum, simply extending copyrights results in higher prices and worse access. We argue that nations should explore alternative ways of allocating copyrights to better achieve copyright’s fundamental aims of rewarding authors and promoting widespread access to knowledge and culture.

Worldwide, copyright laws are routinely criticised for failing to satisfy two of their most fundamental aims: promoting widespread access to knowledge and culture, and rewarding authors.[1] One of the most significant reform initiatives of recent decades has been to extend the duration of rights – a change that has been argued would improve outcomes for both.[2] The Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works (‘Berne Convention’) mandates a minimum term, for most works, of the author’s lifetime + a further 50 years.[3] The European Economic Community extended this to life + 70 in 1993[4] and the United States (‘US’) promptly followed suit.[5] Since then, it has doggedly exported the extension to other nations via ‘free trade’ agreements.[6] Australia adopted the extended term as part of its obligations under the Australia–US Free Trade Agreement in 2005.[7] Canada recently committed to the longer term too, as part of the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement that replaces the North American Free Trade Agreement (‘NAFTA’).[8]

Claims that these extended terms would further copyright’s core aims have been vigorously critiqued.[9] Claims that copyright extensions financially benefit authors are particularly weak. An extension that kicks in half a century after an author dies obviously cannot provide them with any additional rewards – or encourage them to make a single new work. In any event, the additional years of economic rights almost always vest, not in works’ authors, but in their owners and licensees.[10] Thus, the lion’s share of any benefit flows to corporate investors, such as publishers and record labels, rather than creators themselves. It has been argued that those corporations would invest the resulting windfall profits into the creation of additional new works that could not otherwise have been funded. But that has been criticised, including by a team of Nobel Prize-winning economists, for assuming that investors have a lack of access to capital markets and are willing to invest in sub-par projects.[11] This leaves one key economic argument justifying retroactive grants of additional protection: that exclusive rights are necessary to persuade publishers to continue to invest in making older works available – and that, otherwise, they will be underused.[12]

This article investigates that ‘underuse hypothesis’.[13] Not all copyright theories are capable of rigorous assessment, but the underuse claim is a testable hypothesis ‘ripe for empirical analysis’.[14] As developed below, it has previously been the subject of a handful of published studies, but never outside the US context and never by comparing the availability of identical works across jurisdictions with different copyright terms.[15] This study does both, comparing the relative availability of ebooks to public libraries across Australia, New Zealand (‘NZ’), the US and Canada, to evaluate whether the underuse hypothesis is working as promised.

Part II explains the underuse hypothesis in more detail and briefly reviews the literature to have tested it so far. Part III describes our research questions and methods for addressing them. Part IV sets out our results. We find that books are actually less available where they are under copyright than where they are in the public domain, and that commercial publishers seem undeterred from investing in works even where others are competing to supply the same titles. We also find that exclusive rights do not appear to trigger investment in works that have low commercial demand, with books from 59% of the ‘culturally valuable’ authors we sampled unavailable in any jurisdiction, regardless of copyright status. Further, we find that works are priced much higher where they are under copyright than where they are in the public domain, and these differences typically far exceed what would be paid to authors or their heirs. Part V concludes with observations about the implications of these results for future term extension. We argue that, where lengthier rights must be awarded, countries ought to pay much more careful attention to the way they are divided up in order to better achieve copyright’s aims while limiting undesired collateral damage.

A rich tapestry of rationales has been advanced to justify copyright, including that it enhances democratic civil society and operates as protection against unfair competition.[16] But above all others sit the two most fundamental: the ‘utilitarian’ and ‘natural rights’ rationales. Utilitarian theories justify copyright as a way of securing particular economic and social aims, such as the benefits that come from widespread access to knowledge and culture. Prioritising the interests of the broader public, utilitarian theories justify the grant of exclusive rights in order to incentivise investments in information and culture, whilst seeking to minimise the social welfare costs that come from doing so.[17] A purely utilitarian approach would provide the bare minimum necessary to incentivise the desired investments.

The second rationale is grounded in natural rights. Natural rights theories posit that copyright is awarded because it is just and right to do so, typically because the works have sprung from the author’s labour (per Locke),[18] or because they represent a materialisation of her personality (per Kant[19] and Hegel).[20] In naturalist framings, it is the ‘indissoluble personal link’ between creator and work that gives rise to rights, and that justifies broader protection than the bare minimum incentive that would have elicited the work.[21]

These theories are given different weight in different parts of the world. Utilitarian theories are espoused particularly strongly by British Commonwealth countries and their former colonies, including the US. Continental European countries such as France and Germany (and their former colonies too) are the ones most strongly driven by natural rights considerations. However, the copyright laws of every jurisdiction contain elements attributable to both consequentialist and deontological rationales.[22]

This article is primarily concerned with testing the utilitarian rationales for copyright. Insofar as these rationales justify the grant of copyright, it is as an incentive in order to achieve broader aims. Two primary incentives have been identified as necessary. First, copyright is supposed to incentivise works’ initial creation, together with whatever investments are necessary to get them to market and available to the public. Second, it is supposed to incentivise investments in those works’ ongoing availability. After all, society will stop benefiting from works when they can no longer be accessed. As developed further below, it is these investments in ongoing availability that the underuse hypothesis is concerned with.

At the centre of the underuse hypothesis is the argument that, unless investors are guaranteed additional exclusive rights (above and beyond what was necessary to incentivise a work’s initial creation), they will not invest in activities necessary to ensuring works’ ongoing availability, and culture will languish, unexploited.

The underuse hypothesis is a variation on the well-known ‘free-rider problem’.[23] If people can benefit from a creative or informational work without contributing to the costs of creating it, the theory goes, they will ‘free ride’ on the result. Then nobody will have an incentive to contribute to those initial costs, and many works simply will not be created.[24] Intellectual property is particularly vulnerable to free-riding, since it ‘is expensive to create’ but ‘cheaply copied’.[25] If we extend this reasoning beyond the creation of works, and to their maintenance and distribution, we arrive at the underuse hypothesis.[26] As Landes and Posner argue, ‘an absence of copyright protection for intangible works may lead to inefficiencies because of ... impaired incentives to invest in maintaining and exploiting these works’.[27] In other words, publishers are less likely to risk investing in works unless they hold the exclusive rights to do so.

Exclusive rights are available for as long as a work is restricted by copyright, but not once it enters the public domain. At this point, it has been argued, the free rider problem rears its head. If anyone can freely copy public domain works, that interferes with publishers’ incentives to make them available, and will result in less access.

The underuse hypothesis played a key role in 1990s debates about whether the US should extend its copyright term. It was by no means the main impetus or justification for the proposed extension: the prime driver was clearly the European Union’s recent adoption of a life + 70 year term.[28] That had generated an additional 20 years of exclusive rights which would not be enjoyed by the owners of American works unless the US extended its own term to match.[29] But the proposed US extension was strenuously opposed on the basis of the harm it would cause to the public domain, and the underuse hypothesis played a key supporting role in counteracting those claims. By making the case that public domain works are less available than those still under copyright, it weakened the opposition’s claims about the public domain’s economic and social value, changed the cost-benefit calculus, and strengthened the case for extension.

Numerous examples of this use of the underuse hypothesis can be found in the evidence provided to the US Congress. For example, the US Register of Copyrights testified that a ‘lack of copyright protection ... restrains dissemination of the work, since publishers and other users cannot risk investing in the work unless assured of exclusive rights’.[30] The Coalition of Creators and Copyright Owners similarly argued that ‘works protected by copyright are far more likely to be made widely available to the public in a form the public wants to enjoy than works in the public domain’.[31] The US Commissioner of Patents and Trademarks acknowledged that the opposition to term extension was focused around the public harm it would cause, but testified there was ‘ample evidence [showing] that once a work falls into the public domain it is neither cheaper nor more widely available than works protected by copyright’.[32] Notably, although this part of his testimony was provided by way of a written submission, the Commissioner did not provide any examples or citations evidencing this claim. In his oral testimony, he did refer to ‘some evidence ... that the restoration of copyright protection under the NAFTA legislation actually encouraged industry to make available to the public in new editions, and much finer editions, works which otherwise would have remained mouldering in the library’.[33] But here also he failed to provide any source that would enable this evidence to be identified and examined.

The underuse hypothesis is at odds with classical economic theory, of which a core tenet is that investors will continue to produce copies ‘up to the point where the marginal cost of one more copy equals its expected marginal revenue’.[34] In other words, economic theory posits that publishers should rationally continue producing copies of books (or anything else) so long as they can expect to get back more than they put in. Lemley captures the tension between the two theories:

It is hard to imagine senators, lobbyists, and scholars arguing with a straight face that the government should grant one company the perpetual right to control the sale of all paper clips in the country, on the theory that otherwise no one will have an incentive to make and distribute paper clips. We know from long experience that companies will make and distribute paper clips if they can sell them for more than it costs to supply them. ... We can also predict with some confidence that if we did grant one company the exclusive right to make paper clips, the likely result would be an increase in the price and a decrease in the supply of paper clips. Yet supporters of [copyright term extensions] confidently predict exactly the opposite in the case of copyrighted works ...[35]

Despite this clash (and the lack of evidence that the underuse theory works in practice) it received support from both the US legislative and judicial branches. The US House of Representatives report recommending the extension stated, among other reasons, that it would ‘provide copyright owners generally with the incentive to restore older works and further disseminate them to the public’.[36] The Supreme Court of the US, upholding that extension’s constitutionality, observed that Congress had ‘rationally credited projections that longer terms would encourage copyright holders to invest in ... public distribution of their works’.[37] The underuse hypothesis was also widely recognised in academic literature developed around this same time.[38] Thus, although the underuse hypothesis was not the prime driver behind the US term extension, it clearly played a key supporting role in justifying the extension and counteracting opposition. Given the stakes at play, it is crucial to understand the extent to which it is supported by real-world practice.

The 20 years since the US term extension was passed have seen enormous increases in the amount and quality of empirical evidence relevant to copyright law and policy.[39] In that time, six key studies have tested the underuse hypothesis. As developed below, one working paper examining the 19th century US book market reports evidence of publisher reluctance to invest in printing books where they did not have exclusive rights, but each of the five published studies based on more recent data finds the opposite: that works restricted by copyright are actually subject to less investment and narrower dissemination than their counterparts in the public domain.

The best evidence in support of the underuse hypothesis comes from a working paper examining publisher behaviour in the US before 1920, when its law did not yet recognise copyright in foreign books.[40] The study found evidence that, at that time, publishers were wary of publishing foreign works. Their concern was that others could then inexpensively copy their edition and offer it at a lower price, driving the price down and potentially preventing them from recouping their initial investment.[41] The publishing industry solved the problem internally by colluding to informally allow one another exclusivity over particular books.[42]

In 2008, Heald studied the availability of bestselling novels published in the US between 1913–32.[43] Heald sampled 334 books, predominantly from yearly bestseller lists.[44] Of these, 166 were published pre-1923 and therefore in the US public domain,[45] while the remaining 168 were published post-1923 and remained under copyright.[46] Within each group, the 20 ‘most currently popular’ books were also identified to create a ‘durable books’ subgroup.[47]

Heald then compared the books’ availability. As of 2006, he found that public domain books were generally available at higher rates than books under copyright (98% compared to 74%), though both durable books subgroups were fully available (100%).[48] Public domain books were also available in more editions on average than books under copyright (5.2 editions compared to 3.2 editions).[49] For the durable books subgroups, the difference was more dramatic still: public domain durable books were available in an average of 29.1 editions, while their equivalents under copyright averaged 8.9 editions.[50]

Pricing was similar for copyright and public domain books, with the average lowest price for each group found to be identical.[51] However, for the durable books subgroups, the average lowest price of the copyright titles was 81% higher than that of their counterparts in the public domain.[52]

Heald concluded that, contrary to the underuse hypothesis, public domain books were not less available than copyright books.[53] Instead, the data evidenced ‘a highly competitive and robust market’ supporting production of titles in the public domain.[54]

Six years later, Heald released a further study, this time examining the availability of books for sale via online retailer Amazon.[55] He randomly sampled 7,000 titles and estimated the publication date of each based on Library of Congress records.[56] This yielded 2,266 unique fiction books:[57] 72% in the public domain and 28% still under copyright.[58] The sample ended up containing a large proportion of books from the 1850s to 1920s, very few from the 1930s to 1980s, and a higher proportion again from the 1990s and 2000s.[59] It contained 38 books from the 1880s and only 25 from the 1980s, despite the fact that seven times as many books were published in the latter period than in the former.[60]

These results were consistent with Heald’s earlier finding that pre-1923 public domain books were more widely available than post-1923 books that were still under copyright. Based on this data, Heald proposed that books are made widely available when first published, soon ‘disappear’ due to copyright protection (and other factors such as age),[61] and eventually ‘reappear’ upon entering the public domain.[62]

The underuse hypothesis has also been tested in the context of sound recordings. In 2005, Brooks investigated the current availability of sound recordings that had been commercially released in the US between 1890 and 1964.[63] Based on a random sample of 1,500 recordings, he found that just 14% had been reissued on CD by copyright holders.[64] By contrast, 22% had been reissued exclusively by non-rights holders such as foreign labels and ‘small domestic operations operating under the legal radar’.[65] This suggested that exclusive publication rights were not necessary to incentivise investment in making sound recordings available, and actually got in the way of others seeking to do so.[66]

Also in the context of music, Heald has empirically shown that public domain musical compositions are not less likely than copyright compositions to be included in new release films,[67] and in fact more likely to be included on DVD releases.[68]

In 2013, Buccafusco and Heald studied the availability of audiobook recordings of popular novels.[69] Unlike the other studies discussed above, this was not an analysis of the availability of copyright-restricted and public domain works in and of themselves, but rather works derived from pre-existing works (‘derivative works’). Adopting a similar methodology to Heald’s 2008 study, Buccafusco and Heald sampled 171 public domain books and 174 books under copyright.[70] Again, subgroups of durable books were also identified.[71]

Buccafusco and Heald then searched popular online retailers for audiobook recordings of these books and compared availability and pricing.[72] They found that public domain books were more than twice as likely as copyright books to be available as audiobook recordings. Only 16% of the copyright books had at least one audiobook recording available, compared with 33% of the public domain books.[73] For the durable books subgroups, the rates were 80% and 100% respectively.[74]

They further found that, among books available as audiobooks, public domain titles were available in marginally more audiobook editions than were the books under copyright. Copyright books averaged 3.0 recordings per book, compared to 3.3 for titles in the public domain.[75] For the durable books subgroups, the difference was more substantial, at 3.25 editions compared with 6.25 editions, again in favour of the public domain.[76]

Pricing of the two groups was similar: CD recordings averaged USD28 for copyright books and USD26 for public domain books, and MP3 downloads averaged USD19 and USD22 respectively.[77] For the durable books subgroups, the difference was again more material. The average per minute cost for CD recordings was USD0.050 for copyright books and USD0.038 for public domain books.[78] For MP3 recordings, the cost was USD0.036 for copyright books and USD0.028 for those in the public domain.[79]

The study concluded that public domain status does not reduce availability, but in fact seems to increase it.[80] Despite the relatively high cost of producing audiobooks, a far more expensive process than producing physical copies or ebooks, ‘[p]roducers ... are clearly not deterred by their inability to exclude competitors from making competing products. ... A right to exclude is clearly not needed to incentivize the production of audiobooks made from older works’.[81]

The one empirical support for the underuse hypothesis comes from Khan’s working paper, which linked publisher unwillingness to invest in publishing foreign works to a lack of exclusive rights (as discussed above). However, each of the other five studies to have tested the hypothesis has reached the opposite result.

Heald has argued that the high fixed costs associated with 19th century book production may have been what drove publishers’ reluctance to ‘race’ each other to get books to market.[82] If that is correct, we could expect competition to be less of a deterrent to investment as production costs decrease. Interestingly, however, Heald and Buccafusco themselves subsequently found no support for the underuse hypothesis in the case of relatively expensive audiobook production, suggesting that there must be more to the story. The empirical evidence base to date, while limited in number, casts substantial doubt on the underuse hypothesis.

Notably, each of the above studies focuses on the relative availability of copyright and public domain works in a single jurisdiction, the US.[83] Our study tests the underuse hypothesis for the first time across not only the US, but also Australia, NZ and Canada.

Comparing availability across these jurisdictions is of particular interest because of differences in the way copyright terms are determined in each. Before 1978, the US relied upon a copyright renewal system. Works were protected for an initial term, and then granted a second term if the copyright owner opted to proceed with an administrative process to renew them.[84] Renewal rates were low, and copyrights were more likely to be renewed for the more valuable and popular works.[85] That system can skew the analysis because the most valuable works are likely to enter the public domain later than less popular ones that had been created at the same time. For example, comparisons of pre-1923 and post-1923 samples in the US are affected by the fact that, while all pre-1923 works were in the public domain, only the more valuable and popular of the post-1923 works were likely to be still under copyright. By contrast, copyright status in Australia, NZ and Canada over the relevant period has been determined solely by fixed copyright terms, with the consequence that there are no term differences between more and less valuable works of the same age.

Because our study examines ebooks rather than physical books, it also usefully enables us to gauge the willingness of publishers to make non-trivial investments in public domain works. While ebooks are less expensive to produce than physical ones, they still require investments in scanning, formatting and proofreading in order to derive a saleable ebook from the original physical form. Thus, the results we obtain add to the work of Heald and Buccafusco in understanding how copyright status correlates with publisher willingness to invest in new works derived from the originals.

Our study is also the first to test the underuse hypothesis via a title-level analysis: that is, by examining the relative availability of the same works across multiple jurisdictions where their copyright status is different. The intra-US studies described above could not do that for obvious reasons – ie, because a given work can only have one copyright status in a single jurisdiction. This method may open up new possibilities for evaluating the costs or benefits associated with term extension.

In this article we test the underuse hypothesis in the context of the library elending market. If the hypothesis is correct, we should see that commercial publishers invest less in making public domain books (for which they do not have exclusive rights) available than books that are still under copyright. In this section we first explain the library elending ecosystem, then briefly describe how we constructed our sample, collected and cleaned our data, and matched titles to enable cross-jurisdictional comparison. We then set out the questions we used to test the hypothesis.

Today, public libraries commonly offer patrons opportunities to borrow ebooks.[86] This is not as simple as it is for physical books. Acquiring and lending ebooks involves the making of copies and transmissions and, as a result, libraries require a licence from the copyright holder to do so.[87] Direct licence negotiations between every library and every publisher would involve impossibly high transaction costs, so a market has emerged in which ebook ‘aggregators’ negotiate licences with individual publishers in various territories, and then pass them downstream.[88] Public libraries then contract with one or more of these aggregators for the supply of ebooks to lend to their patrons. Library elending has become big business. In 2008, the leading global provider, Rakuten OverDrive Inc (‘OverDrive’) reported 10 million checkouts worldwide (including not just ebooks but also audiobooks, music and video).[89] By 2018, the company had grown to service some 43,000 libraries across 70 countries, and processed 185 million loans of ebooks alone.[90] To put those numbers in perspective, PubTrack Digital reported just 162 million global ebook sales in 2017.[91]

Subscribing libraries license titles from OverDrive for elending via its online ‘Marketplace’ in each country. Since copyright is territorial, and OverDrive does not necessarily have the right to license all titles in all countries, librarians in Canada have access to a different selection of ebooks to choose from in the OverDrive Marketplace than librarians in NZ, who have access to a different selection than librarians in the US and so on.

OverDrive provides access to a small range of free material, but its central ‘Marketplace’ in each country only provides access to titles offered by commercial publishers. That makes it an ideal source for assessing the rates at which publishers (as distinct from individuals or cultural institutions) invest in making older titles available in the form of ebooks. And, because OverDrive charges publishers a percentage of sales, with no hosting or title fees,[92] it imposes minimal additional barriers to inclusion of additional titles.

OverDrive also provides ideal conditions for testing the relationship between availability and copyright status. In related work studying the relative availability of more than 94,000 titles across five countries, we found that Australia and NZ had exceptionally high degrees of overlap in the ebooks available to their libraries, as did the US and Canada.[93] That is, in each of those two country pairings, identical titles were available and unavailable at close to identical rates. However, the countries in each pair have different copyright terms. NZ has (narrowly) managed to hold onto the Berne Convention’s life + 50,[94] but its close neighbour and trading partner Australia grants 20 years more.[95] At the time of writing, Canada also still grants the Berne Convention minimum.[96] In the US however, older works were subject to a system of renewable terms that means some remain under copyright while others have entered the public domain.[97] This provides the conditions for a natural experiment. If the underuse hypothesis is correct, titles ought to be available via OverDrive at higher rates where they are still under copyright, and lower rates where they are in the public domain. The closely related availabilities we have demonstrated for those pairs in our related work means that we can be more confident that the differences we identify in this sample are attributable to copyright status. Further, since public libraries source books for elending almost exclusively from aggregators, our use of aggregator data controls for the possibility that publishers in countries with longer terms might be declining to invest in making ebooks available to libraries because of the possibility of competition from infringing copies.

In constructing the sample, we were interested in capturing titles that were:

1. ‘culturally valuable’; and

2. in the ‘copyright/public domain window’ – that time period where they are still under copyright in some jurisdictions but have elsewhere entered the public domain.

It was important to populate our sample with ‘culturally valuable’ titles because books are published in large numbers and depreciate quickly. Commercial life is typically exhausted 1.4 to 5 years from publication;[98] some 90% of titles become unavailable in physical form within just two years.[99] Had we used a purely random sample of titles in the relevant age bracket, we would have expected almost all of them to have no remaining cultural or economic value and, therefore, even if we had found them to be missing from library catalogues, that finding may not have been of particular interest. Focusing instead on titles with enduring cultural value enables us to draw more meaningful conclusions from our results.

To identify such titles we used the current versions of the Oxford Companions to English, Australian, NZ, American and Canadian literature.[100] These texts contain biographical information for thousands of authors deemed significant by specialist contributors. We treated authors’ inclusion in these Companions as prima facie evidence of their books’ enduring cultural value.

We were interested in authors whose works were in the public domain in some countries but remained under copyright in others. We selected all Oxford Companion authors who had died between 1962 and 1967. That resulted in a novel list of 250 authors, among which some of the most notable included Aldous Huxley, Sylvia Plath and Ian Fleming.[101] Aside from unusual cases (involving, for example, posthumous or pseudonymous publication), all books by these authors have entered the public domain in NZ and Canada, and remain under copyright in Australia. In the US, as developed further below, they can have either status, depending on their original publication date and whether their owners renewed their short initial term.

It may be that the sampled authors have different levels of popularity in different jurisdictions – that there is greater demand for some Canadian authors in Canada, for example, and some greater demand for some Australian authors in Australia. Our preliminary testing found no consistent effect related to nationality and so we have not controlled for this. However, it is possible that differing regional demand could explain some part of the variation in our results.

We collected availability data from OverDrive in April 2018, using a script to query the 250 author names in its distinct ‘Marketplaces’ for Australia, NZ, the US and Canada. While OverDrive has several distinct ebook sources, its ‘Marketplaces’ contain the offerings from commercial publishers we wanted to study. We then cleaned the data, excluding works to which sampled authors made non-substantial contributions (for example, only forewords), those by homonymous authors (the Ian Fleming of James Bond fame was in; the Ian Fleming who wrote management training manuals was out), translations, posthumous publications (to which different copyright rules apply) and so on. For 23 authors, only these excluded categories of works were available, effectively removing those authors from the sample.[102] This left us with 3,224 records authored by our 227 sampled authors and made available by publishers to libraries across Australia, NZ, the US and Canada.

We then took an additional step to verify the copyright status of US titles, which, as noted above, depends on their original publication date and renewal status. When we collected our data in 2018, works were still under US copyright if they had been published between 1923–67 and their initial term had been renewed by the copyright owner.[103] Titles published before 1923, or between 1923–67 but not renewed, were in the public domain. Our sample contains 521 distinct titles available in the US. Of these, 373 were published between 1923–63. We established the copyright status of each title by searching the Stanford Copyright Renewals Database, which contains a complete list of Class A (book) renewals received by the US Copyright Office during the relevant period.[104] Our search found copyright to have been renewed for 272 of the 373 books (72.9%), with the remaining 101 entering the public domain. By way of comparison, the renewal rate for all works ranged from 3% in 1914 to a peak of approximately 22% in 1991.[105] For books, generally, renewal rates averaged around 8%.[106] Landes and Posner have used renewal data as a proxy for determining the rates at which works lose value, arguing that ‘the fact that a small fraction of works are renewed implies that most copyrights have very little economic value after twenty-eight years’.[107] The relatively high renewal rate for the titles in our sample suggests that they were more likely to retain commercial value than the average book of the same age, making them particularly suitable for testing the underuse hypothesis.[108]

To assess comparative availability across jurisdictions, we needed to link records at a title level. To do so, we wrote a matching algorithm that treated two records as referencing the same work if they shared an identical title and at least one identical author. Famous books are sometimes published in multiple editions with, for example, forewords by different contributors. Those contributors are often also listed as authors. By requiring the algorithm to match only one identical author (together with the identical title) we were able to match titles that had the same substantive content.

Matching records at a title level enables us to not only identify the number of distinct works made available, but also to compare availability of the same works across jurisdictions. This is a significant development over the prior literature, which compared groups of books. It allows us to compare like and like: for example, how does the availability and price of Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World compare under copyright and in the public domain? This reduces the difficulties of accounting for different popularity across different samples of works, which complicated Heald’s studies comparing newer to older books.[109] As developed below, for some analyses we additionally used manual matching processes to link titles in different ways (for example, where we were calculating the books available in Jurisdiction X but not Jurisdiction Y).

There are four main licence types by which books were made available to libraries in our OverDrive data: one supplying perpetual access, and the three others providing metered access. We introduce them here to facilitate understanding of the analyses that follow.

1. ‘One copy, one user’ or ‘OC/OU’ licences entitle the purchasing library to lend the title to one borrower at a time for as long as they have access to the elending aggregator’s platform;

2. Loan limited licences entitle the library to lend the title to one borrower at a time a set number of times (eg, ‘26 loans’), for as long as the library has access to the platform;

3. Time limited licences entitle the library to lend the title to one borrower at a time for a set period (eg, ‘12 months’);

4. Time and loan limited licences entitle the library to lend the title to one borrower at a time for a set period or a set number of loans, whichever comes first (eg, ‘36 loans or two years’).

The underuse hypothesis posits that publishers will invest more in making books available where they are under copyright (and thus come with exclusive rights to prevent competition) than where they are in the public domain. We formulated several research questions to test this using various proxies for publisher willingness to invest.

1. How many distinct titles were available to libraries in each of Australia, NZ, the US and Canada? If the underuse hypothesis is correct, we should see fewer titles available where they are in the public domain than where they are still covered by copyright.

2. How many editions of each title are offered in each country? Multiple editions of public domain titles are an indicator of commercial publisher willingness to compete directly on the same titles.

3. Were any books available where they were under copyright, but not where they were in the public domain? And vice versa – were there books available in the public domain, but not where they were under copyright? Through this title level comparison, we sought to identify the direction in which underinvestment (if any) was flowing.

We then asked a further two questions aimed at contextualising the publisher behaviour:

1. How did commercial publisher investments in public domain works compare to non-commercial investments?

2. How did the prices for books made available via OverDrive vary by country and copyright status?

As introduced above, our primary interest in this article is to test the underuse hypothesis in the library elending context. Our first three research questions assess the willingness of commercial publishers to invest in making older books available. Notably, as introduced above, none of the books in our sample are natively digital. Although it is cheaper to digitise texts today than ever before, publishers must still make non-trivial investments in scanning, formatting and proofreading in order to derive a saleable ebook from the original physical form. Here we report an overview of our results, followed by full details below.

First, we measure the number of distinct titles available in each market. We find that most authors had no titles available via OverDrive, in any jurisdiction, regardless of copyright status. This shows the existence of exclusive rights is not sufficient, in and of itself, to incentivise investment in works. We also find that there were more distinct titles available in Canada and NZ (public domain jurisdictions) than Australia (copyright), and that all three outperform the US (mixed copyright and public domain), suggesting that extended rights may actually lead to less rather than more investment.

Second, we measure the number of editions offered in each country. We find a greater number of editions of each title in public domain countries, demonstrating that commercial publishers are willing to invest in making works available even in the face of direct competition.

Third, we identify all cases in which titles were available in copyright jurisdictions but not public domain jurisdictions (and vice versa). Considerably more titles are ‘missing’ where they are under copyright than where they are in the public domain, again suggesting that extended rights may actually lead to less investment than would otherwise have occurred. These results are developed below.

For 135 of the 227 sampled authors (59%), we found that commercial publishers made no ebooks available to libraries to license in any of Australia, NZ, the US or Canada. Authors with zero books included five Pulitzer Prize winners (Van Wyck Brooks, Russel Crouse, Esther Forbes, Frank Luther Mott and Elmer Rice); renowned philosopher Alexander Meiklejohn; and prominent Australians Dame Mary Gilmore and David Unaipon, whose portraits feature on the Australian $10 and $50 bank notes.[110] This is particularly striking since, as noted above, OverDrive only charges publishers a percentage of actual sales (with no hosting or service charges), thus imposing minimal barriers to additional works being made available.

Commercial publishers made at least one ebook available in at least one jurisdiction for the remaining 92 authors. Of these, 30 (33%) had only one title available, and 70 (76%) had eight or fewer (see chart showing titles by author at Figure 1). A number of prolific and well-known writers had just a fraction of their work represented. For example, e e cummings authored over 30 books,[111] but just seven titles were available to libraries for elending. Four-time Pulitzer Prize winner Robert Lee Frost had six distinct titles available to libraries in ebook form, and even these had substantial overlap.[112] Only five of Nobel Laureate TS Eliot’s 80+ titles[113] were available, and there was just one from fellow Laureate Hermann Hesse.

These results are even more striking for the fact that they come from a sample of older books that is disproportionately likely to have ongoing value. If we were to scale up to the entire publishing industry, we would expect overall availability for older books to be considerably worse than the picture painted here. These results show that the existence of exclusive rights is not sufficient, in and of itself, to incentivise commercial investment in works, even when they have ongoing cultural value.

Figure 1 – Distribution of the number of titles among the 92 authors with ebooks available

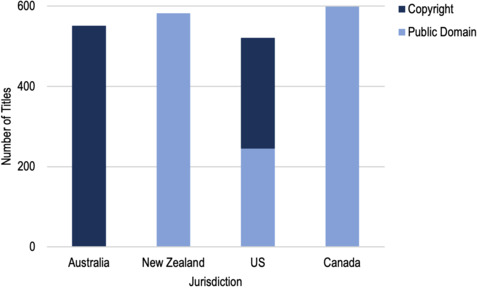

After using our title matching algorithm to link records across jurisdictions, we next compared the number of distinct ebooks available in each. The US had the fewest distinct titles available (521 total, including 276 in copyright and 245 in its public domain), followed by Australia (551), NZ (582), and Canada (599). These results are charted at Figure 2.

These ratios were substantially different to those we detected in our control dataset of 94,328 titles (the ‘large-scale sample’) developed in our related work.[114] There, we found very high degrees of overlap in the books that were available in two pairs of countries: Australia with NZ, and the US with Canada. In that large-scale sample, 99.7% of the books available to NZ public libraries were also available to Australian ones, and 99% of the books available to Australian public libraries were also available to NZ ones. Ninety-seven per cent of the books available to Canadian libraries were also available to US libraries, and 97.6% of the books available to US libraries were also available to Canadian ones. Other country pairings had markedly lower similarities: for example, only 78.8% of books available to US libraries were also available to Australian libraries. These results provide a baseline for the degree of similarity we would expect for each pair of jurisdictions. To the extent that greater differences are found, they are more likely to be attributable to copyright status.

In the large-scale sample Canada had 0.6% more titles available than the US, but in the public domain it had 15% more. NZ had 0.7% more titles than Australia in the control dataset, but 5.6% more in the public domain sample. We also observed that NZ had 10.5% fewer books than the US in the control, but 11.7% more in the public domain sample. However, there was less similarity between NZ and the US in the control sample (65,664 of NZ’s 74,799 titles were also available in the US, 87.8%) and so, while this result is highly striking, we can be less confident that the difference is attributable to copyright status.

These results are particularly interesting given the US’s status as the world’s most valuable book market,[115] with publisher revenues estimated at over USD26 billion in 2017.[116] NZ had access to more titles in the public domain sample despite its book market being worth a fractional 1% of that amount[117] – and Canada had more still. The strong showing by the two public domain countries suggests a marked willingness by publishers to invest in making derivative ebooks available in the absence of exclusive rights.

Notably, even Australia had more titles available to libraries than the US. All sampled titles were under copyright in Australia, compared to a mix of copyright and public domain in the US. We hypothesise that the relative lack of investment in the US market may be partially explained by higher tracing costs and large potential liability for getting it wrong. It is more difficult to determine whether pre-1963 works are in the public domain under the US framework due to its previous renewal system,[118] and those who make an error not only risk costly infringement proceedings but also the threat of statutory damages of up to USD150,000 per infringement.[119] Those factors may be discouraging publishers from investing in public domain works in the US as much as elsewhere.

Figure 2 – Number of titles available and copyright status for each jurisdiction

The analysis above tested the underuse hypothesis by comparing the number of distinct titles available in each jurisdiction. However, it is possible for the same title to be made available to libraries via multiple offerings, perhaps at different price points or by different providers. We have shown in related work that copyright titles usually have only a small number of offerings, since ebook rights in a given jurisdiction are typically controlled by a single publisher.[120] But what about public domain works? Conventional economic theory suggests publishers would keep investing in editions for as long as they can make a profit, while the underuse theory suggests publishers will not invest unless they have exclusive rights. We measured the number of licences offered for the sampled titles to see which theory is better supported by the data. The hypothesis to test was whether titles in the public domain had more licence offerings than the same titles when they are under copyright.

The number of licences per title is not a perfect measure. OverDrive representatives told us in an interview that they aim to discourage multiple editions of public domain works unless subsequent editions add substantial value – for example, through additional editorial content.[121] This policy would not place any downward pressure on the first offering of a work, but could potentially do so for subsequent licences. Having said that, it is enforced haphazardly at best: on our large-scale sample, we found over 160 offerings for Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Adventures of Sherlock Holmes in a single jurisdiction.[122] Thus, although aware that the number of licences per title may underestimate publishers’ willingness to invest in public domain works, it is nonetheless a useful proxy.

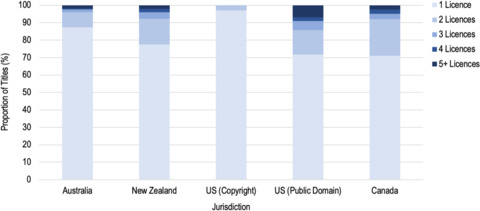

We found that titles were available with more licences in NZ than in Australia. We also found that Canada had more licences than the US. As developed below, these results are highly statistically significant, strongly supporting the hypothesis that titles in the public domain had more licence offerings than the same titles when they are under copyright.

To obtain these results, we calculated how many licences were available for each title in each jurisdiction. This includes titles with no licences at all (ie, titles that were unavailable were counted as having zero licences). For each of the 661 distinct titles in our sample, we compared our two paired jurisdictions (NZ vs Australia, and Canada vs US). NZ had 100 titles for which more licences were available than in Australia, 561 titles for which an equal number of licences were available, and zero titles for which fewer licences were available. We calculated statistical significance by using the non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test, which enables calculation of the significance of such wins (when NZ has more), draws (when NZ and Australia have an equal number) and losses (when Australia had more). The result was highly statistically significant (p<10–9), ie, less than one chance in a billion that this result is due to chance. Canada had 212 titles for which more licences were available than in the US, and 367 titles for which an equal number were available, and 82 titles for which it had fewer. This result was also highly significant (p<10–11), ie, less than one chance in 100 billion of the result being due to chance. Notably, of the 82 titles that had more licences in the US than in Canada, 84% (69 titles) were in the public domain in the US, and just 13 were under copyright.

Since the above analysis involved matching titles, it was not possible to compare the number of editions in the US public domain compared to US copyright (since, definitionally, a given title can only be in one or the other). Accordingly, we did a further analysis that examined the average number of licences per work for the US copyright and public domain groups. We found that 1.03 licences were available on average for each US copyright work. By contrast, works that had entered the US public domain averaged 1.91 licences. That is particularly striking given that the US public domain works include those that were not renewed, indicating a perceived relative lack of value for those works compared to those in the copyright subsample. These results show that competition is demonstrably occurring over public domain titles, and that, as predicted by economic theory, the absence of exclusive rights is not deterring publishers from investing.

Our results observing a greater number of licence offerings for books in the public domain than in copyright is comparable to that of Heald in the context of physical books, where he observed 63% more public domain books than copyright ones.[123] It is also consistent with Reimers’ findings, for a set of historical bestselling fiction titles, that the shift from copyright to the public domain leads to more rather than fewer editions.[124]

Figure 3 – Distribution of number of licences per title for each jurisdiction

Because we were able to identify each distinct title appearing in our sample, and ‘match’ them across jurisdictions, we were able to detect where books were and were not available. To better understand the direction in which underinvestment was occurring, we investigated which of the sampled ebooks were available in a copyright jurisdiction but unavailable in the corresponding public domain jurisdiction (and vice versa). If the underuse theory is correct, we would expect to find titles more available in copyright jurisdictions than where they are in the public domain.

At the time of data collection, all titles were under copyright in Australia, and in the public domain in NZ and Canada. US titles were in the public domain if they were published before 1923, or if published between 1923–63 but not renewed. All others remain restricted by copyright.

In determining whether a title was available in one country but not another, we manually accounted for availability in different forms. For example, William Faulkner’s two book collection Sanctuary and Requiem for a Nun was available in NZ but not in Australia. However, Sanctuary and Requiem were individually available in Australia, so we counted it as available there for this analysis.

We found no ebooks available in Australia (where they would be under copyright) but not in NZ (where they would be in the public domain). However, we identified 12 ebooks that were available in NZ (public domain) but not in Australia (copyright).[125] These included titles by notable authors such as CS Lewis, William Faulkner and Flannery O’Connor.

In North America, we identified 101 titles available in Canada but not in the US.[126] In the other direction, 11 titles were available under copyright in the US but unavailable in Canada,[127] and 27 titles were available in the US public domain but not available in Canada, where they would also be in the public domain.[128] That so many more titles were available in Canada than the US is particularly striking. Canada’s population is a tenth the size of its southern neighbour, making investments in older works relatively less attractive. Nonetheless, Canada is where commercial publishers have invested in making more works available.

These results suggest that, at least for older, culturally valuable works with low fixed and marginal costs of production and distribution, underinvestment may flow from the existence of copyright rights, rather than from their absence.

These first three questions directly tested the underuse hypothesis. Not only did we find no evidence in support, but indeed we found what appears to be a positive public domain effect: that titles are more available, and in a greater number of editions, where they are in the public domain than where they are under copyright. Longer exclusive rights for older, ‘culturally valuable’ titles demonstrably results in less investment than where those titles were permitted to enter the public domain. Furthermore, the mere existence of exclusive rights is shown not to be sufficient to incentivise investment in the absence of some commercial market, and where such a market exists, publishers seem far less put off by the prospect of competition than the underuse hypothesis asserts.

Above, we report evidence that commercial publishers invest more in works that are in the public domain than those for which they have exclusive rights, as well as willingness to compete with one another by investing in multiple editions of the same titles. However, we also observed that just over 40% of our ‘culturally valuable’ authors had even one book available. Here, we further contextualise the observed behaviour of commercial publishers by comparing commercial availability of public domain ebooks to non-commercial availability via Project Gutenberg.[129] Project Gutenberg is a volunteer-run program that digitises public domain books and makes them available to the public online for free – over 57,000 as of November 2018, when we collected our availability data from its website.[130] By comparing availability on the US OverDrive marketplace to that on the US Gutenberg site, we sought to see whether there was any support for the underuse hypothesis: after all, widespread availability from alternative (free) sources may potentially lead to downward pressure on commercial investment.

Across the commercial (OverDrive) and non-commercial (Project Gutenberg) platforms, we found a total of 338 titles by our sampled authors. Of these, 112 (33%) were available via both. That is to say, of the 245 titles made available by commercial publishers on OverDrive, 112 (46%) were also available for free via Project Gutenberg. And, reciprocally, of the 205 titles on Project Gutenberg, 112 (55%) were also available commercially via OverDrive. Of the remaining 226 titles, 133 were available exclusively on the US OverDrive site and 93 were available exclusively via Project Gutenberg. In total, US libraries had commercial access to around 20% more titles from commercial publishers via OverDrive than did the general public via Project Gutenberg.

We also calculated the number of titles made available per author via each platform. While individual authors’ availabilities varied substantially, overall OverDrive had more titles available per author (mean = 4.1, median = 2) than Project Gutenberg (mean = 3.3, median = 1).

Consistent with our previous findings, these results demonstrate considerable willingness by publishers to invest in making ebooks commercially available absent exclusive rights, even in the face of competition from non-commercial sources. Interestingly, it also shows that commercial publishers are investing in making more works available to libraries than the leading non-commercial source is to the public. Having said that, it is striking that close to half the books available via OverDrive are not available via Gutenberg (and vice versa). This may suggest volunteers and commercial publishers apply different criteria in deciding which older texts to digitise.

In our final analyses, we examined the prices charged for books on OverDrive and how they differ according to copyright status. Our hypothesis was that books are more expensive when under copyright than when they are in the public domain. As developed below, we indeed found that titles are considerably more expensive, on average, when they’re under copyright than where they are in the public domain, and that those differences exceed the royalties that would be paid to authors or their heirs.

Comparing OverDrive prices across jurisdictions is challenging. For one thing, there may well be a different number of offerings for a title in a given country. For example, there are eight versions of Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World available to libraries in Canada, but only one available to libraries in the US. Different results will be reached for price analyses depending on whether they include all offerings, some, or just one. Second, books may be licenced on different terms in different jurisdictions. If a title costs USD13 for ‘26 checkouts’ in one jurisdiction, and USD21 for an unlimited ‘OC/OU’ licence elsewhere, which is cheaper? Assumptions inescapably have to be made in order to compare them.

There is no perfect solution to these challenges, and so we respond to them by conducting three distinct analyses. First, we calculate the mean price for each licence type in each jurisdiction. The aim of this analysis is to see whether, at an aggregate level, we can distinguish differences between pricing of public domain and copyright books. This aggregate analysis provides a useful preliminary picture. However, since titles may be licensed on different terms in different jurisdictions, prices may be influenced by those differences rather than copyright status. Thus, in our second analysis, we compare all books regardless of licence terms. We do this by studying the price per circulation of titles as a function of the number of circulations. That is, we calculate an overall price per circulation for all titles in each jurisdiction (ie, the cost to a library of loaning the ebook to a patron once, twice, three times etc). This enables us to compare prices across different licence types, providing a more complete picture of book price. However, as with the first analysis, this provides only an aggregate picture. It does not control for the fact that there are differences in the available titles in the various jurisdictions. For example, Margery Allingham’s Dancers in Mourning is available on an OC/OU licence for USD13.99 in the US, and is not available at all in Canada; that impacts aggregate results in both Canada and the US. Nor does it control for potential differences in price that arise from, for example, the available books in one jurisdiction having different page counts to those in another.[131] Our final price analysis controls for both, by comparing, at a title level, prices of only those books that appear in both jurisdictions of each country pair.

For each analysis we calculated two sets of prices for the US: one for its copyright titles and one for titles in its public domain. We also converted all prices to US dollars, approximating OverDrive’s own currency conversion process.

In this first price analysis we compare the mean prices, in each jurisdiction, of the four main licence types: OC/OU, loan limited, time limited, and time + loan limited. These licences were explained above.[132]

Since this analysis involved unpaired samples with potentially unequal variances, we used the Welch t-test to assess statistical significance of results. We indicate the statistical significance (p-value) in brackets below.

We observed that public domain titles were almost always cheaper than copyright ones, as follows:

• OC/OU titles averaged USD9.06 compared to USD28.63 (p<10–24);

• Loan limited titles averaged USD0.28 per loan compared to USD0.52 per loan (p<10–3);

• Time limited titles averaged USD3.28 per year compared to USD20.99 (statistical significance could not be assessed as there was only one title under this licence in the copyright sample);

• Time + loan limited titles averaged USD0.15 per loan compared to USD0.52 (p<10–9). Note that we calculated these prices by assuming these titles would be lent the maximum number of loans permitted under the licence, usually either 36 or 52.

• OC/OU titles averaged USD14.17 compared to USD28.63 (p<10–15);

• Loan limited titles averaged USD0.22 per loan compared to USD0.52 per loan (p<10–16);

• Time limited titles averaged USD4.43 per year compared to USD20.99 (statistical significance could not be assessed as there was only one title under this licence in the copyright sample);

• Time + loan limited titles averaged USD0.33 per loan compared to USD0.52 (p<10–3).

Interestingly, those differences were reduced or reversed when comparing Canadian prices to those of the US public domain subsample. While all licence types were cheaper in Canada than in US (copyright), OC/OU, time limited and time + loan limited licences were all cheaper in the US public domain than in Canada.

• OC/OU titles averaged USD11.55 compared to USD11.70 (p 0.45, ie, not statistically significant);

• Loan limited titles averaged USD0.21 per loan compared to USD0.46 per loan (p<10–11);

• Time limited titles averaged USD4.26 per year compared to USD2.99. This reverse result (supporting the opposite hypothesis) reached only p 0.14, ie, not statistically significant;

• Time + loan limited titles averaged USD0.34 per loan compared to USD0.38 (p<0.03).

These price differences are striking. US (copyright) titles are more expensive than Canadian (public domain) titles by up to 136%, while US (public domain) titles are almost universally cheaper than the Canadian offerings. These price differences are consistent with those observed in previous studies. For example, Heald reported an 81% premium on physical books under copyright compared to those in the public domain, while Reimers found a difference of up to 35% and Li et al about 100%.[133]

These large differences are unlikely to be explained by the fact that publishers of copyright ebooks pay royalties, which are typically around 10% of the recommended retail price for print books and 25% of net receipts for ebooks.[134] Publisher investments in new forewords or annotations are also unlikely to account for such sizeable differences.

The difference between public domain and copyright prices was lower between NZ and Australia, but still apparent. Loan limited titles were 54% cheaper in NZ, and time + loan limited titles 10.5% cheaper, while the differences between OC/OU and time limited licences were not statistically significant. We hypothesise that this may be due to the Australian market being bigger than that of NZ, and thus it being more worthwhile for publishers to compete for sales via price. See further below the section on ‘Unexpected Publisher Behaviour’ at Part IV(C)(5).

For our second price analysis we calculate each licence’s ‘cost per circulation’. If a title is lent out once, the cost per circulation equals the full licence price, regardless of whether the title is licensed on OC/OU or metered access terms. For two loans, the cost per circulation is the full licence price divided by two, and so on. For OC/OU titles, the calculation proceeds ad infinitum. For metered access titles however it is necessary to factor in the cost of purchasing additional licences upon expiry. For example, for a 26-checkout licence, the cost of 12 checkouts is the cost of purchasing one licence divided by 12. The cost of 27 checkouts is the cost of purchasing two licences divided by 27.[135]

With the per circulation price analysis we again observed that, for the most part, public domain ebooks were priced lower than those under copyright. We calculated prices on 5, 13 and 20 circulations. The price for 13 circulations is particularly notable since, in our related work examining over seven million loans, that’s the median number of times we calculated a library ebook is circulated.[136]

In NZ and Australia, the respective mean prices per circulation were USD2.28 and USD2.58 at 5 circulations (p<0.01); USD0.88 and USD0.99 at 13 circulations (p<0.01); USD0.57 and USD0.65 at 20 circulations (p<0.01).

As between Canada and the US (copyright), the results were even more striking. The respective mean prices per circulation were USD2.50 and USD5.24 at 5 circulations; USD0.96 and USD2.02 at 13 circulations; USD0.62 and USD1.31 at 20 circulations (all p<10–23).

As between the US (public domain) and US (copyright), for 5, 13 and 20 circulations the results were USD1.67 vs USD5.24, USD0.64 vs USD2.02, and USD0.42 vs USD1.31 (all p<10–33).

Finally, we note that as between Canada and the US (total), of which some are in copyright and others in the public domain, Canadian prices are still significantly cheaper (p<0.001) with prices for 5, 13 and 20 circulations being USD2.50 vs USD3.02, USD0.96 vs USD1.16, and USD0.62 vs USD0.76 respectively.

This analysis again consistently shows significant variations between copyright and public domain samples that exceed the amounts that would be payable in royalties or for forewords on copyright titles.

In this final price analysis, we compare prices at a title level. We include only titles that are available in both pairs of countries, and, where there were multiple licences available, we retained only the cheapest option, regardless of the lending model attached.

Since this analysis compares books on a title level, it controls for price differences that might be attributable to there being different titles and editions in the aggregate analyses above.

We treated very similar prices as the same in order to account for minor exchange rate differences. More precisely, if the difference between the two prices was of less than 5% of the maximum of the two prices, we considered the price to be identical.

Sixty-four titles were cheaper in NZ than in Australia, 474 had identical prices, and 12 were more expensive in NZ. We again applied the Wilcoxon test, which found the result was statistically significant (p<0.001).

Canada had cheaper prices than the US for 154 titles, 274 identical prices, and 51 more expensive titles (p<10–12).

This result becomes even starker when we drill down further to compare Canada to the US (copyright) subgroup. There, 128 titles were cheaper in Canada, there were 109 identical prices, and 27 were more expensive in Canada (p<10–18). These results very strongly support the hypothesis that books are more expensive when under copyright than when they are in the public domain.

Consistently, results were much more mixed when we compared the two public domain samples (Canada and US public domain). These titles were in the public domain in both jurisdictions. They were identically priced in 165 cases, cheaper in Canada in 26 cases, and cheaper in the US in 24 cases (p 0.37, ie, not statistically significant).

It is a core tenet of economic theory that, as competitors enter a market, prices will be driven down towards the marginal cost of delivery. Where a work is restricted by copyright there can be no (legitimate) competition, but that changes once it enters the public domain. The lower prices we found in the aggregate for public domain versus copyright titles supports this theory. Within our data however, we also observed some unexpected behaviour: publishers widely maintaining high prices for individual ebooks even where they had entered the public domain and had attracted competition.

We identified 62 examples of publishers offering titles at the same licence and price in two jurisdictions despite the fact that the title was under copyright in one and in the public domain in the other. For example, Random House makes Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World available via a ‘36 loans or 24 months’ licence for USD15.76 in both Australia and NZ. This is despite the fact that alternative ‘52 loans or 24 months’ licences for that same book were also available in NZ for as little as USD0.99.

In some cases, publishers seem to have responded to a work entering the public domain by introducing additional, cheaper licences while simultaneously maintaining their previous offerings. For example, HarperCollins offered Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar via a single licence in the US (USD17.99), where it is under copyright. It offered the book on identical licence terms in Canada at four progressively lower prices (USD7.75, USD4.64, USD2.32 and USD1.54). In such cases, we hypothesise that publishers may not have updated previous offerings once the book entered the public domain – or that they were happy to provide multiple offerings at different price points on the basis that at least some libraries would purchase the more expensive ones. In sum, while we did detect a downward price trend where there was competition for public domain titles, not all publishers behaved as economic theory predicts, and prices tended to remain well above marginal cost even in the presence of competition.

When the US term extension was enacted in 1998, one of the key supporting justifications was that it would improve availability for existing works.[137] However, the theory that additional rights would cause right-holders to invest in the ongoing distribution of their works has not been borne out by the evidence. Above, we canvassed a small but persuasive body of empirical evidence that showed a lack of any support for the underuse hypothesis in the US context. In this article, we contributed to the evidence base by testing the theory outside the US market, and with the first ever cross-country comparison at the title level. Our results show that, at least where fixed and marginal costs of production are relatively low, there is no evidence that the presence of competitors for the same works deters investment. Instead, publishers are investing in making works available where they believe that there is some sufficient market for them, and are not where there is not, regardless of copyright status – just as conventional economic theory predicts. Indeed, our results show that works are more available from commercial publishers when they are in the public domain than when the same books are under copyright. If we factor in that NZ and Canadian book markets are a fraction of the size of the US market, those results are starker still. Not only are additional rights not necessary to incentivise commercial publishers to make marketable works available, they actually correlate with less investment and less availability than for the same works without such rights. The upshot is that where copyright has been extended, libraries are being obliged to pay higher prices in exchange for worse access.

Our results also shed new light on the costs to society that arise from awarding copyrights that far outlast commercial interest. Although the authors we sampled were of sufficient ongoing cultural significance to be included in the most current editions of the Oxford Companions to Literature, just over 40% had even a single digital title made available to libraries, regardless of their copyright status. This shows that commercial exhaustion widely occurs before even the shortest minimum terms of life + 50 years. It also shows that commercial interest in books can be exhausted long before their cultural value.

These results come at a time of growing awareness about the social and economic costs of copyright terms that outlast their owners’ interest. In 2018, for example, the US-based Authors Guild came out against any further extensions of the US copyright term, stating that ‘[i]f anything, we would likely support a rollback to a term of life-plus-50 if it were politically feasible’.[138] Its focus, no doubt, is on securing more direct and effective measures for improving author incomes. However, countries continue to be pressured to extend terms as the cost of trade access. NZ recently avoided having to do so by the slimmest of margins: it had agreed to a 20 year extension as part of the Trans-Pacific Partnership,[139] but that agreement lapsed after the US withdrew,[140] and the replacement treaty eventually ratified in its stead contained no such mandate.[141] Canada probably will not enjoy any such escape, having finally yielded to longstanding US pressure to extend its term in late 2018.[142]

There can be no doubt that radical action is needed to address copyright’s ongoing failures to secure a fair share of economic rewards to authors and promote widespread access to knowledge and culture. But it is increasingly clear that longer terms are not the answer, and indeed contribute to the problem. If it simply tacks another 20 years onto its term, Canada can expect its libraries to have worse access, while doing little or nothing to increase payments into authors’ pockets. So, what are the options for countries obliged to adopt unjustifiable term extensions as a condition of accessing trade markets? One promising line of approach is to rethink the ways in which those extended rights are divided up. In ‘A New Copyright Bargain? Reclaiming Lost Culture and Getting Authors Paid’,[143] Giblin recently drew up a roadmap for an alternative copyright bargain. By introducing new reversion rights for authors, combined with safeguards against orphaning, she argues that it is possible to maintain incentives for creation and distribution, reclaim currently-lost culture, and secure to creators a fairer share – all while remaining consistent with treaty obligations.[144] Faced with new evidence about the costs of current approaches, it may be time for nations which are locked in to costly and counter-productive copyright structures to similarly explore the ‘wriggle room’ left to them by treaties.

|

Ackerley, JR (Joe

Randolph)[1]*

|

Lachance, Louis*

|

|

Akhmatova, Anna*

|

Lambert, Eric

|

|

Aldington, Richard

|

Lane, Red*

|

|

Allen, CR (Charles Richards)*

|

Larsen, Nella

|

|

Allen, LH (Leslie Holdsworth)*

|

Le Franc, Marie*

|

|

Allen, Ralph*

|

Legg, Frank*

|

|

Allen, Sir Carleton Kemp*

|

Lett, Lewis*

|

|

Allingham, Margery

|

Letters, FJH (Francis Joseph Henry)*

|

|

Amato, Renato (‘Michael’)*

|

Lewis, CS (Clive Staples)

|

|

Andersen, Johannes C (Carl)*

|

Liebling, AJ (Abbott Joseph)

|

|

Anderson, John*

|

Lock, Arnold Charles Cooper*

|

|

Asch, Nathan*

|

Low, Sir David*

|

|

Ashton, Julian Howard*

|

Lowe, Eric*

|

|

Auslander, Joseph*

|

Lowry, Robert W*

|

|

Banning, Lex*

|

Loy, Mina (Gertrude Lowy)**

|

|

Barnes, Margaret Ayer*

|

Lubbock, Percy

|

|

Basso, (Joseph) Hamilton*

|

Luhan, Mabel Dodge

|

|

Bataille, Georges[1]**

|

Macbeth, Madge*

|

|

Baume, Eric (Frederick Ehrenfried)*

|

MacDonald, Wilson*

|

|

Beach, Sylvia

|

MacNeice, Louis

|

|

Bedford, Ruth*

|

Mann, Cecil*

|

|

Beebe, (Charles) William

|

Mannix, Daniel*

|

|

Behan, Brendan

|

Marlowe, Mary*

|

|

Bein, Albert*

|

Marshall, Alan John*

|

|

Bell, Clive

|

Marshall, James Vance (Donald Gordon Payne)

|

|

Bemelmans, Ludwig*

|

Masefield, John Edward

|

|

Birkett, Winifred*

|

Maugham, W Somerset

|

|

Blackmur, RP (Richard Palmer)**

|

Maurois, André**

|

|

Blitzstein, Marc*

|

McCullers, Carson (Smith)

|

|

Braithwaite, William Stanley Beaumont*

|

McFee, William (Morley Punshon)*

|

|

Breton, André**

|

McKellar, John*

|

|

Briggs, Ernest*

|

McKinney, Jack*

|

|

Brooke, Jocelyn

|

Meiklejohn, Alexander*

|

|

Brookes, Herbert*

|

Meller, Leslie*

|

|

Brooks, Van Wyck*

|

Miller, E (Edmund) Morris

|

|

Bruno, Frank*

|

Miller, Perry (Gilbert Eddy)**

|

|

Burdekin, Katherine*

|

Morin, Paul*

|

|

Burdon, RM (Randal Mathews)*

|

Morris, Myra*

|

|

Burgess, Thornton W (Waldo)

|

Motley, Willard*

|

|

Carson, Rachel

|

Mott, Frank Luther*

|

|

Casey, Gavin*

|

Mulgan, Alan*

|

|

Charbonneau, Robert*

|

Naish, John*

|

|

Churchill, Sir Winston

|

Niland, D’Arcy

|

|

Clark, Russell*

|

O’Brien, Flann

|

|

Cocteau, Jean**

|

O’Casey, Sean

|

|

Cody, JF (Joseph Frederick)*

|

O’Connor, Flannery

|

|

Connolly, Roy*

|

O’Connor, Frank

|

|

Corkery, Daniel*

|

O’Hara, Frank

|

|

Costain, Thomas B (Bertram)

|

Odets, Clifford*

|

|

Courage, James*

|

Ogilvie, Will (William Henry)*

|

|

Craig, Gordon*

|

Okigbo, Christopher*

|

|

Cross, Zora*