University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

THE HIGH COURT ON CONSTITUTIONAL LAW: THE 2018 STATISTICS

ANDREW LYNCH[1]* AND GEORGE WILLIAMS[1]**

This article presents data on the High Court’s decision-making in 2018, examining institutional and individual levels of unanimity, concurrence and dissent. It does so in the context of the elevation of a new Chief Justice to lead the Court and the appointment of a new member to the bench at the commencement of the year. Recent public statements on the Court’s decision-making practices by the new Chief Justice and others inform discussion of the statistics. This article is the latest instalment in a series of annual studies conducted by the authors since 2003.

This article reports the way in which the High Court as an institution and its individual judges decided the matters that came before them in 2018. It continues a series which began in 2003.[1] The High Court’s decisions and the subset of constitutional matters decided in the calendar year are tallied to reveal how the institution has responded to the cases that came before it and where each individual member of the court sits within those institutional decisions. Not only does this show levels of consensus and dissent, it can highlight the existence, and sometimes the decline, of coalitions between particular Justices. Commentary is offered on the annual tables to place them in the context of the immediately preceding years in which the same judicial actors have featured, and the longer view reaching back to the series’ commencement in the era of the High Court under Chief Justice Gleeson.

The results presented in this article have been compiled using the same methodology that underpins the others in the series.[2] As always, we acknowledge the limitations of an empirical study of the decisions of any final court over the space of a single calendar year, particularly so in respect of the constitutional cases which comprise a small portion of the High Court’s case load. The series is but one example of annual studies of the decision-making in final courts, with the first and most famous being that commenced in respect of the United States Supreme Court in the Harvard Law Review by Felix Frankfurter and James Landis in 1928.[3] Yearly reporting enables developments on the Court to be tracked as they emerge, complementing current debate about the decisions of the Court and the way in which the Justices work with each other to fulfil the institution’s function. The introduction to our article on the 2017 decisions referred to prominent judicial contributions to that debate, noting particularly the attention given by Chief Justice Kiefel to explaining how the Court operates as a multi-member decision-making body which nevertheless respects the judicial independence of its members.[4] We refer readers of this article to that earlier instalment for the broader context provided as to decision-making practices in the current High Court.

Table A: High Court of Australia Matters Tallied for 2018

|

|

Unanimous

|

By Concurrence

|

Majority over Dissent

|

Total

|

|

All Matters Tallied for Period

|

26 (44.07%)

|

24 (40.68%)

|

9 (15.25%)

|

9 (100%)

|

|

All Constitutional Matters Tallied for Period

|

1 (16.67%)

|

5 (83.33%)

|

0 (0.00%)

|

6 (100%)

|

A total of 59 matters were tallied for 2018. 63 cases appear on the Australasian Legal Information Institute (‘AustLII’) High Court database[5] for the year but four of these (identified in the Appendix) were excluded as matters decided by a single Justice.

The manner in which these were decided was through unanimous judgments (44.07% of matters tallied), by separate concurring opinions (40.68%), and by majority over dissent (15.25%). The percentage of matters decided with dissent was half that for 2017, while matters resolved either unanimously or through concurring opinions both increased several percentage points from the previous year.

Just six of the 59 matters (10.17%) tallied for 2018 were constitutional in character. The definitional criteria that determines our classification of matters as ‘constitutional’ remains:

that subset of cases decided by the High Court in the application of legal principle identified by the Court as being derived from the Australian Constitution (‘Constitution’). That definition is framed deliberately to take in a wider category of cases than those simply involving matters falling within the constitutional description of ‘a matter arising under this Constitution or involving its interpretation’.[6]

Our only amendment to this statement as a classificatory tool has been to additionally include any matters before the Court involving questions of purely state or territory constitutional law.[7] There were no matters in 2018 that came within this additional aspect of the criteria.

The six constitutional matters of 2018 declined from 11 such matters (21.57%) in 2017. In terms of the number of constitutional matters tallied, 2018 is on par with 2014 as a year with the lowest number of such matters over the course of these annual surveys since they began in 2003.[8] (It should be noted that, additionally, Gordon J decided a matter concerning the constitutional provisions on parliamentary privilege but this is not included here as a single judge decision.)[9] It might be thought that the reduction in constitutional cases in 2018 was due to a drop off in high-profile controversies of parliamentary disqualification heard by the High Court sitting as the Court of Disputed Returns. However, as Table C below makes plain, the number of cases raising section 44 of the Commonwealth Constitution (‘Constitution’) was the same in both 2017 and 2018.

Last year was remarkable in a different respect. In 2018 no Justice dissented from the Court’s orders in a constitutional case. This is the first year in these annual studies for which no dissent has been recorded in such a matter. Contrast this with 2014 as a year with a comparably low number of constitutional matters – half of those were decided over a minority opinion.[10] The lack of any constitutional dissent in 2018 follows on from our reporting that 2017 ‘saw the least amount of explicit disagreement in constitutional law since this annual series was commenced’.[11] 2018 sets a new benchmark – one that can never be raised.

TABLE B(I): All Matters: Breakdown of Matters by Resolution and Number of Opinions Delivered[12]

|

Size of bench

|

Number of cases

|

How Resolved

|

Frequency

|

Cases Sorted by Number of Opinions Delivered

|

||||||

|

1

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

5

|

6

|

7

|

||||

|

7

|

18 (30.51%)

|

Unanimous

|

4 (6.78%)

|

4

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

By concurrence

|

10 (16.95%)

|

|

2

|

7

|

|

1

|

|

|

||

|

6:1

|

–

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

5:2

|

2 (3.39%)

|

|

1

|

|

|

1

|

|

|

||

|

4:3

|

2 (3.39%)

|

|

|

|

2

|

|

|

|

||

|

5

|

28 (47.46%)

|

Unanimous

|

11 (18.64%)

|

11

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

By concurrence

|

12 (20.34%)

|

|

7

|

4

|

1

|

|

|

|

||

|

4:1

|

2 (3.39%)

|

|

|

2

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

3:2

|

3 (5.08%)

|

|

|

2

|

1

|

|

|

|

||

|

3

|

13 (22.03%)

|

Unanimous

|

11 (18.64%)

|

11

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

By concurrence

|

2 (3.39%)

|

|

1

|

1

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

2:1

|

–

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

TABLE B(II): Constitutional Matters: Breakdown of Matters by Resolution and Number of Opinions Delivered[13]

|

Size of bench

|

Number of cases

|

How Resolved

|

Frequency

|

Cases Sorted by Number of Opinions Delivered

|

||||||

|

1

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

5

|

6

|

7

|

||||

|

7

|

6 (100.00%)

|

Unanimous

|

1 (16.67%)

|

1

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

By concurrence

|

5 (83.33%)

|

|

1

|

3

|

|

1

|

|

|

||

|

6:1

|

–

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

5:2

|

–

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

4:3

|

–

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

Tables B(I) and (II) reveal several things about the High Court’s decision-making over 2018. First, they present a breakdown of, respectively, all matters and then just constitutional matters according to the size of the bench and how frequently it split in the ways open to it. Second, the tables record the number of opinions which were produced by the Court in making these decisions. Immediately under the heading ‘Cases Sorted by Number of Opinions Delivered’ are the numbers one to seven, which are the number of opinions it is possible for the Court to deliver. Where that full range is not applicable, shading is used to block off the irrelevant categories. It is important that readers appreciate that the figures given in the fields of the ‘Cases Sorted by Number of Opinions Delivered’ column refer, as is indicated, to the number of cases containing as many individual opinions as indicated in the heading bar.

These tables should be read from left to right. For example, Table B(I) tells us that of the 28 matters heard by a five-member bench, three were decided 3:2 and one of those featured four sets of reasons. In this way, Table B(I) enables us to identify the most common features of the cases in the period under examination. The most frequent method by which a matter was resolved in 2018 was for a five-judge bench to decide by concurrence. If we unpack that figure by looking to the number of judgments delivered, we learn that of the 12 cases decided in this way, the majority (seven matters) feature two judgments. By contrast, 11 matters are decided 5:0 through delivery of a unanimous opinion.

Table B(I) illuminates the source of the high overall rate of unanimity over the year. Although almost half the Court’s work was done through a five-member bench, there was an unusually high number of matters decided by three judges. All 13 such matters (22.03% of those decided in 2018) came to the Court on appeal from the Supreme Court of Nauru and concerned refugee claims – compared to just three such cases (and one criminal appeal) the year before. Eleven of the 2018 Nauru appeals were decided unanimously.

Interestingly for a year in which disagreement was at such low levels, there was no fewer than seven matters in 2018 that meet the description of a ‘close call’ – that is, a case decided over a minority of more than one Justice.[14] Of those, five came down to a single vote, with the Court deciding two matters 4:3 (both cases featuring four separate sets of reasons)[15] and three matters 3:2 (with two of these decided with three opinions[16] and one with four[17]). By contrast, in 2017, only one case turned on a single vote.[18]

Table B(II) records the same information in respect of the subset of constitutional cases. All six of the constitutional cases were decided by all seven judges. The constitutional matter with the most separate opinions was Burns v Corbett,[19] decided 7:0 but with five opinions delivered across the Court.

TABLE C: Subject Matter of Constitutional Cases

|

Topic

|

No of Cases

|

References to Cases

(Italics indicate repetition)

|

|

1

|

10

|

|

|

4

|

6, 10, 11, 17

|

|

|

2

|

6, 11

|

|

|

1

|

11

|

|

|

1

|

11

|

|

|

1

|

6

|

|

|

1

|

11

|

|

|

1

|

2

|

|

|

1

|

15

|

|

|

Ch III

|

2

|

2, 15

|

|

1

|

15

|

|

|

1

|

15

|

|

|

1

|

15

|

|

|

1

|

15

|

|

|

1

|

15

|

|

|

1

|

15

|

|

|

1

|

15

|

|

|

1

|

15

|

|

|

1

|

15

|

Table C lists the provisions of the Constitution, as well as the state constitutional law issue, that arose for consideration in the six constitutional law matters tallied for 2018. It is assembled by reference to the provisions identified as arising in the matters that are listed under the catchwords accompanying each decision.

Section 44 maintained its dominance in the High Court’s constitutional case load – featuring, as it had in 2017, in four matters, three of which the Court heard as the Court of Disputed Returns and which are included in the tally of constitutional cases in this study. The other two matters concerned issues of the aliens power in section 51(xix), Chapter III jurisdiction and the inconsistency of Commonwealth and state laws under section 109 of the Constitution.

TABLE D(I): Actions of Individual Justices: All Matters

|

|

Number of Judgments

|

Participation in Unanimous Judgment

|

Concurrences

|

Dissents

|

|

Kiefel CJ

|

50

|

20 (40.00%)

|

29 (58.00%)

|

1 (2.00%)

|

|

Bell J

|

38

|

13 (34.21%)

|

24 (63.16%)

|

1 (2.63%)

|

|

Gageler J

|

47

|

20 (42.55%)

|

23 (48.94%)

|

4 (8.51%)

|

|

Keane J

|

40

|

14 (35.00%)

|

25 (62.50%)

|

1 (2.50%)

|

|

Nettle J

|

46

|

20 (43.48%)

|

21 (45.65%)

|

5 (10.87%)

|

|

Gordon J

|

41

|

15 (36.59%)

|

23 (56.10%)

|

3 (7.32%)

|

|

Edelman J

|

43

|

14 (32.56%)

|

26 (60.47%)

|

3 (6.98%)

|

Table D(I) presents, in respect of each Justice, the delivery of unanimous, concurring and dissenting opinions in 2018. While the Court’s membership was consistent over the year, assisting in a direct comparison between Justices, not all judges sit on all cases (which explains why the number of opinions differs between judges). Last year, the Chief Justice delivered the most opinions, 50 of the full tally of 59 matters, and Bell J delivered the least with 38. With the Justices not all sitting on the same matters, the opportunities for unanimity or disagreement inevitably varied.

For the first time since 2013, all members of the Court dissented at least once in 2018. Dissent from the Chief Justice, and also Bell and Keane JJ, has generally been infrequent; much less so for the other members of the Court.

Justice Nettle delivered the most dissenting opinions in 2018 with five of his 46 judgments (10.87%) in the minority. One gets a sense of how disagreement on the Court is currently experienced by looking to the identity of the lead dissenter over the last few years – as a percentage of judgments delivered this was Gageler J in 2017, Gordon J in 2016, Nettle J in 2015, and Gageler J again in 2014. The presence of an individual who year after year finds themselves as the Court’s ‘great dissenter’, delivering a substantial number of minority opinions by a prominent margin from the rest of the bench, has not been the experience of the late French and early Kiefel eras of the High Court.

Three joint dissents were issued: Kiefel CJ and Keane J, in what was the only dissent for both, in Amaca Pty Ltd v Latz;[20] Nettle and Gordon JJ in Mighty River International Ltd v Hughes[21] and Nettle and Edelman JJ in UBS AG v Tyne.[22] As already noted above in relation to Table B(I), of the nine matters decided with a minority opinion, only two of them had a lone dissenter while the other seven saw a ‘close call’ with disagreement expressed by at least two Justices. Again, this puts the current experience of dissent on the High Court into perspective, making a clear contrast with the situation of a regularly isolated individual on an otherwise cohesive bench.

TABLE D(II): Actions of Individual Justices: Constitutional Matters

|

|

Number of Judgments

|

Participation in unanimous judgment

|

Concurrences

|

Dissents

|

|

Kiefel CJ

|

6

|

1 (16.67%)

|

5 (83.33%)

|

–

|

|

Bell J

|

6

|

1 (16.67%)

|

5 (83.33%)

|

–

|

|

Gageler J

|

6

|

1 (16.67%)

|

5 (83.33%)

|

–

|

|

Keane J

|

6

|

1 (16.67%)

|

5 (83.33%)

|

–

|

|

Nettle J

|

6

|

1 (16.67%)

|

5 (83.33%)

|

–

|

|

Gordon J

|

6

|

1 (16.67%)

|

5 (83.33%)

|

–

|

|

Edelman J

|

6

|

1 (16.67%)

|

5 (83.33%)

|

–

|

Table D(II) records the actions of individual justices in the six constitutional matters tallied for 2018. There is little to add to what has already been said about these cases – all six of them were heard by all seven Justices of the Court and one was decided unanimously while the other five were decided by a number of concurring opinions, with one case having as many as five separate statements of reasons (see Table B(II)). While there was an absence of dissent, Justices were willing to express different opinions as to how the law should be developed in reaching the result of the Court.

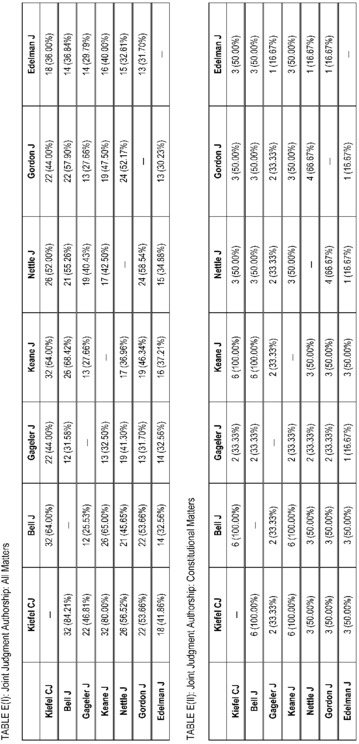

Tables E(I) and E(II) indicate the number of times a Justice joined in an opinion with his or her colleagues. These tables should be read horizontally as the percentage results vary depending on the number of judgments each member of the Court delivered over the year. As mentioned earlier, that Justices do not necessarily sit with each other on an equal number of occasions must be noted as a factor that limits opportunities for some pairings to collaborate. In particular, the much higher than usual number of three-member bench decisions affected opportunities for certain Justices of the Court to join with others. Those caveats duly made, it remains clear that Gageler and Edelman JJ joined less in opinions relative to the joining of other colleagues.

The highest incidence of joining in judgment across all cases of 2018 was that of Kiefel CJ with, respectively, Bell and Keane JJ. Kiefel CJ joined with both those Justices in 32 of the cases they each decided – though these were not the same 32. For the Chief Justice, that meant she joined with both Bell and Keane JJ in 64% of her decisions, while Bell J wrote with Kiefel CJ in 84.21% of the cases she decided and Keane J joined with Kiefel CJ in 80% of the cases he decided. Bell and Keane JJ did not join quite as often with each other as they did with the Chief Justice, but they did so ahead of any other members of the Court. We continue to note, as we have for the last few years, the accord between the publicly expressed views on the value of joint judgments by the Chief Justice, Bell and Keane JJ and their demonstration of this in the decisions of the Court.[23]

Chief Justice Kiefel was the member of the Court that all Justices joined with most – except Gordon J, who decided two more matters by joining with Nettle J than she did with the Chief Justice.

In the constitutional arena, Chief Justice Kiefel, Bell and Keane JJ joined in all six cases. Justices Nettle and Gordon, as in preceding years, joined more with each other on constitutional matters than with others (in four of the six matters). Justices Gageler, Nettle and Gordon joined with Edelman J in just one constitutional matter – the Court’s unanimous decision in Re Kakoschke-Moore.[24]

TABLE F(I): Joint Judgment Authorship: All Matters: Rankings

|

|

Kiefel CJ

|

Bell J

|

Gageler J

|

Keane J

|

Nettle J

|

Gordon J

|

Edelman J

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Kiefel J

|

–

|

1

|

3

|

1

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

|

Bell J

|

1

|

–

|

6

|

2

|

4

|

3

|

5

|

|

Gageler J

|

1

|

5

|

–

|

4

|

2

|

4

|

3

|

|

Keane J

|

1

|

2

|

6

|

–

|

4

|

3

|

5

|

|

Nettle J

|

1

|

3

|

4

|

5

|

–

|

2

|

6

|

|

Gordon J

|

2

|

2

|

4

|

3

|

1

|

–

|

4

|

|

Edelman J

|

1

|

4

|

4

|

2

|

3

|

5

|

–

|

TABLE F(II): Joint Judgment Authorship: Constitutional Matters: Rankings

|

|

Kiefel CJ

|

Bell J

|

Gageler J

|

Keane J

|

Nettle J

|

Gordon J

|

Edelman J

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Kiefel CJ

|

–

|

1

|

3

|

1

|

2

|

2

|

2

|

|

Bell J

|

1

|

–

|

3

|

1

|

2

|

2

|

2

|

|

Gageler J

|

1

|

1

|

–

|

1

|

1

|

1

|

2

|

|

Keane J

|

1

|

1

|

3

|

–

|

2

|

2

|

2

|

|

Nettle J

|

2

|

2

|

3

|

2

|

–

|

1

|

4

|

|

Gordon J

|

2

|

2

|

3

|

2

|

1

|

–

|

4

|

|

Edelman J

|

1

|

1

|

2

|

1

|

2

|

2

|

–

|

The rankings of joining between the Justices indicated by tables E(I) and (II) are the subject of tables F(I) and (II). It should be noted that in some instances the difference between how frequently one judge wrote with various colleagues is not large, maybe just one or two decisions. Accordingly, the ranking of different judges as joining with each other in these two tables needs to be understood by reference to the tables E(I) and (II).

Last year was a remarkable year for decision-making by the High Court. For the first time in these studies, which date back to 2003, there was not a single dissent in any case involving constitutional law. Across all matters, the rate of dissent was also much reduced from 2017, with only half the percentage of dissents in 2018 as compared to the year before. As a result, 2018 saw a corresponding increase in decisions resolved unanimously or through concurring opinions.

What remains most striking though from 2018 is the Court’s record in deciding constitutional matters. Constitutional matters are renowned, as indeed this statistical series has borne out, for their capacity to manifest deep disagreement about fundamental questions of law and policy between the judges of the Court. This reflects the high stakes involved in such matters. At least as regards the federal Constitution, the High Court is the final decision-maker, enjoying the power to overturn parliament by declaring legislation to be invalid.

Constitutional matters also present special challenges for judicial decision-making. They typically require the Court to give meaning to the words of a Constitution drafted in the 1890s which has not been altered on any occasion since 1977. Not surprisingly, these words can be vague or ill-fitting for contemporary circumstances. In the case of the imprecise command in section 92 of the Constitution that trade, commerce, and intercourse among the states ‘shall be absolutely free’, the result was decades of division on the High Court.[25]

These factors mean that constitutional controversies are often overlaid with disagreements about methodology, such as to the appropriate method of interpretation or the relevance of historical materials, or views about the proper governance of Australia, such as to the respective roles and functions of Australia’s central government and the states. These complexities by their nature tend to result in a greater divergence of opinion amongst the judges of the High Court than do other areas of the law, as has been borne out in these surveys since 2003.

How then to explain 2018, in which all constitutional matters were decided without dissent? The first point is to recognise the record of last year does not indicate a simple absence of disagreement. Only one of the six constitutional matters was decided unanimously, with the other five involving concurrence amongst the judges. One of those matters involved five separate judgments, with three others involving three separate judgments. The fact that the orders in these matters rested on a number of different opinions reveals that ongoing disagreements, or at least perspectives, persist on the Court about the law and facts arising in these matters.

Even so, there is no denying that the lack of constitutional dissent in 2018 stands in sharp contrast to the norm. This may reflect the homogeneity of the judges of the Court when it comes to their professional background. The levels of agreement and the trend towards an ‘institutional voice’ that the 2018 statistics and those of recent years demonstrate may reflect successive federal governments appointing High Court judges almost exclusively from the ranks of state Supreme Courts and even more particularly the Federal Court. Of the current bench, only Gageler J did not serve on another court before coming to the High Court.

While the current bench is perhaps the most diverse in the High Court’s history in terms of gender, age and geography, it is interesting that this trend has not been replicated when it comes to the professional background of High Court justices.[26] Governments have eschewed members of academia, and it has been many years since a person was appointed to the High Court directly from the bar or from the ranks of the nation’s solicitors or former politicians. Australia’s major parties appear to have converged on the view that the High Court should be made up of judges elevated from lower courts. By making such appointments, the Labor government’s selections have attracted none of the controversy of past eras.[27] A consequence of this new norm of High Court judges having prior judicial experience may be that they will have developed a conception of the judicial role, and possibly a disposition to certain institutional practices, that is distinct from that which prevailed in earlier eras. Those contemporary predispositions will tend to be compatible with the views expressed candidly by Chief Justice Kiefel about contemporary judicial method on a multi-member court.[28]

In that sense, decision-making on constitutional law in 2018 reflected in part the view of the Chief Justice that the High Court ought, wherever possible, to speak as a singular institution. Her aversion to individualism, at least as the default practice of judgment delivery, is apparent in the 2018 statistics. The high frequency of ‘joining in’ by the Chief Justice and Bell and Keane JJ is particularly notable, as in earlier years. Other judges were more likely to write alone, but nonetheless still came to the same or a similar conclusion as the Court, thereby demonstrating individualism in terms of how they expressed their opinion but not in regard to the outcome of the matter.

This may be a product of the influence of the Chief Justice in changing the way the Court approaches multi-member decision-making. Not so long ago, the judges would have a single conference after hearing a case and then retire to chambers to separately consider and write their judgments. The Chief Justice has indicated that all members of the Court are now ‘willing participants in longer, and sometimes multiple, conferences’ throughout the judgment-writing process.[29] This involves the Justices striving for consensus on occasion in order to meet the institutional aspirations:

We have now found that if views are divergent or there is no clear majority, so long as another meeting is arranged in a short period of time, that problem may be overcome. We are also finding that further meetings, where we can concentrate on the ‘sticking points’, tend to be quite fruitful.[30]

Unsurprisingly, this new institutional approach also aligns with the view of the Chief Justice that a ‘single judgment of the Court or of the majority carries greater authority’ and ‘instils confidence in the Court’s decision’.[31]

The lack of dissent in 2018 in constitutional matters may also be a product of the case load of the Court. This was a year in which the High Court decided very few constitutional cases, and all but two of those involved parliamentary disqualification under section 44 of the Constitution. High levels of agreement may result from the Court deciding less controversial cases involving straightforward applications of the Constitution. This though was not the case when it came to section 44. The language of the section is arcane and difficult to interpret, as the High Court demonstrated in 1992 in its split decision in Sykes v Cleary.[32] High levels of agreement in the section 44 matters may have instead resulted from a different factor.

The section 44 matters resolved in 2018, as was the case in 2017, involved high stakes. They were decided in the context of the eligibility of large numbers of representatives being challenged, and the Court cases generated heated political disagreement and enormous media attention. It was also possible that these challenges would destabilise or even bring down the government given its slender majority in the House of Representatives.

These factors heightened the need for the High Court to speak with a clear voice. The potential disqualification of members of Parliament caused enough political turbulence without the added uncertainty produced by division on the Court, and a lack of clarity about the state of the law and which other members might be disqualified. Such concerns are reflected in the Court’s decisions over recent years on section 44. The Court has avoided split decisions, and a year in which section 44 cases dominated was always likely to be year of comparatively low dissent.

The notes identify when and how discretion has been exercised in compiling the statistical tables in this article. As the Harvard Law Review editors once stated in explaining their own methodology, ‘the nature of the errors likely to be committed in constructing the tables should be indicated so that the reader might assess for himself the accuracy and value of the information conveyed’.[33]

• Falzon v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2018] HCA 2; (2018) 262 CLR 333.

• Re Lambie (2018) 351 ALR 559.

• Re Kakoschke-Moore (2018) 352 ALR 579.

• Alley v Gillespie [2018] HCA 11; (2018) 353 ALR 1.

• Burns v Corbett; Burns v Gaynor; Attorney General for New South Wales v Burns; Attorney General for New South Wales v Burns; New South Wales v Burns (2018) 353 ALR 386.

• Re Gallagher (2018) 355 ALR 1.

• Re Culleton [2018] HCA 33; (2018) 358 ALR 678 – Kiefel CJ sitting alone.

• Wehbe v Minister for Home Affairs [2018] HCA 50; (2018) 361 ALR 1 – Edelman J sitting alone.

• Plaintiff S164/2018 v Minister for Home Affairs [2018] HCA 51; (2018) 361 ALR 8 – Edelman J sitting alone.

• Alford v Parliamentary Joint Committee on Corporations and Financial Services (2018) 361 ALR 410 – Gordon J sitting alone.

The following cases involved a number of matters but were tallied singly due to the presence of a common factual basis or questions:

• Commissioner of the Australian Federal Police v Hart; Commonwealth of Australia v Yak 3 Investments Pty Ltd; Commonwealth of Australia v Flying Fighters Pty Ltd [2018] HCA 1; (2018) 262 CLR 76.

• Burns v Corbett; Burns v Gaynor; Attorney General for New South Wales v Burns; Attorney General for New South Wales v Burns; New South Wales v Burns (2018) 353 ALR 386.

• Amaca Pty Ltd v Latz; Latz v Amaca Pty Ltd [2018] HCA 22; (2018) 356 ALR 1.

• Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Thomas; Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Martin Andrew Pty Ltd; Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Thomas Nominees Pty Ltd; Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Thomas (2018) 357 ALR 445.

• Shrestha v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection; Ghimire v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection; Acharya v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2018] HCA 35; (2018) 359 ALR 22.

• Mighty River International Ltd v Hughes; Mighty River International Ltd v Mineral Resources Ltd [2018] HCA 38; (2018) 359 ALR 181.

• Tony Strickland (a pseudonym) v Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions; Donald Galloway (a pseudonym) v Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions; Edmund Hodges (a pseudonym) v Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions; Rick Tu (2018) 361 ALR 23.

• AB (a pseudonym) v CD (a pseudonym); EF (a pseudonym) v CD (a pseudonym) [2018] HCA 58; (2018) 362 ALR 1.

• Australian Securities & Investments Commission v Lewski; Australian Securities & Investments Commission v Wooldridge; Australian Securities & Investments Commission v Butler; Australian Securities & Investments Commission v Jaques; Australian Securities & Investments Commission v Clarke [2018] HCA 63; (2018) 362 ALR 286.

No 2018 cases were multiple tallied.

The following matters were not tallied as constitutional:

• Minogue v Victoria [2018] HCA 27; (2018) 356 ALR 363 – a question about the validity of legislative provisions for consistency with the ‘constitutional assumption of the rule of law’ was found unnecessary to answer and received no substantive discussion from the Court.

• Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Thomas; Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Martin Andrew Pty Ltd; Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Thomas Nominees Pty Ltd; Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Thomas (2018) 357 ALR 445 – two interveners made submissions concerning section 118 of the Constitution but no issue concerning that section arose for determination.

• Both Minister for Immigration and Border Protection v SZVFW [2018] HCA 30; (2018) 163 ALD 1 and Hossain v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2018] HCA 34; (2018) 359 ALR 1 referred to constitutional provisions but these were not the focus of the decision.

• Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2003 Statistics’ [2004] UNSWLawJl 4; (2004) 27(1) University of New South Wales Law Journal 88.

• Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2004 Statistics’ [2005] UNSWLawJl 3; (2005) 28(1) University of New South Wales Law Journal 14.

• Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2005 Statistics’ [2006] UNSWLawJl 21; (2006) 29(2) University of New South Wales Law Journal 182.

• Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2006 Statistics’ [2007] UNSWLawJl 9; (2007) 30(1) University of New South Wales Law Journal 188.

• Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2007 Statistics’ [2008] UNSWLawJl 9; (2008) 31(1) University of New South Wales Law Journal 238.

• Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2008 Statistics’ [2009] UNSWLawJl 8; (2009) 32(1) University of New South Wales Law Journal 181.

• Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2009 Statistics’ [2010] UNSWLawJl 12; (2010) 33(2) University of New South Wales Law Journal 267.

• Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2010 Statistics’ [2011] UNSWLawJl 42; (2011) 34(3) University of New South Wales Law Journal 1030.

• Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2011 Statistics’ [2012] UNSWLawJl 33; (2012) 35(3) University of New South Wales Law Journal 846.

• Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2012 Statistics’ [2013] UNSWLawJl 19; (2013) 36(2) University of New South Wales Law Journal 514.

• Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2013 Statistics’ [2014] UNSWLawJl 20; (2014) 37(2) University of New South Wales Law Journal 544.

• Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2014 Statistics’ [2015] UNSWLawJl 38; (2015) 38(3) University of New South Wales Law Journal 1078.

• Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2015 Statistics’ [2016] UNSWLawJl 41; (2016) 39(3) University of New South Wales Law Journal 1161.

• Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2016 and French Court Statistics’ (2017) 40(4) University of New South Wales Law Journal 1468.

• Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2017 Statistics’ [2018] UNSWLawJl 39; (2018) 41(4) University of New South Wales Law Journal 1134.

* Professor, Head of School, Faculty of Law, University of New South Wales.

** Anthony Mason Professor, Scientia Professor and Dean, Faculty of Law, University of New South Wales; Barrister, New South Wales Bar.

We thank Trent Ford for research assistance.

[1] Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2003 Statistics’ [2004] UNSWLawJl 4; (2004) 27(1) University of New South Wales Law Journal 88. For a full list of the published annual studies, see the Appendix to this article. An earlier article, by one of the co-authors, examined a larger focus: Andrew Lynch, ‘The Gleeson Court on Constitutional Law: An Empirical Analysis of Its First Five Years’ [2003] UNSWLawJl 2; (2003) 26(1) University of New South Wales Law Journal 32.

[2] See Andrew Lynch, ‘Dissent: Towards a Methodology for Measuring Judicial Disagreement in the High Court of Australia’ (2002) 24(4) Sydney Law Review 470 (‘Dissent’), with further discussion in Andrew Lynch, ‘Does the High Court Disagree More Often in Constitutional Cases? A Statistical Study of Judgment Delivery 1981–2003’ [2005] FedLawRw 16; (2005) 33(3) Federal Law Review 485, 488–96.

[3] For the inaugural study, see Felix Frankfurter and James M Landis, ‘The Business of the Supreme Court at October Term, 1928’ (1929) 43(1) Harvard Law Review 33.

[4] Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2017 Statistics’ [2018] UNSWLawJl 39; (2018) 41(4) University of New South Wales Law Journal 1134, 1135–8 (‘The 2017 Statistics’).

[5] Australasian Legal Information Institute <http://www.austlii.edu.au/> (‘AustLII’). For further information about decisions affecting the tallying of 2018 matters see the Appendix – Explanatory Notes at the conclusion of this article.

[6] Stephen Gageler, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2001 Term’ [2002] UNSWLawJl 8; (2002) 25(1) University of New South Wales Law Journal 194, 195 (citations omitted).

[7] Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2007 Statistics’ [2008] UNSWLawJl 9; (2008) 31(1) University of New South Wales Law Journal 238, 240.

[8] Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2014 Statistics’ [2015] UNSWLawJl 38; (2015) 38(3) University of New South Wales Law Journal 1078 (‘The 2014 Statistics’).

[9] Alford v Parliamentary Joint Committee on Corporations and Financial Services (2018) 361 ALR 410.

[10] Lynch and Williams, ‘The 2014 Statistics’ (n 8) 1080.

[11] Lynch and Williams, ‘The 2017 Statistics’ (n 4) 1140.

[12] All percentages given in this table are of the total number of matters tallied (59).

[13] All percentages given in this table are of the total number of constitutional matters tallied (6).

[14] Brice Dickson, ‘Close Calls in the House of Lords’ in James Lee (ed), From House of Lords to Supreme Court: Judges, Jurists and the Process of Judging (Hart Publishing, 2011) 283, 283.

[15] Kalbasi v Western Australia [2018] HCA 7; (2018) 352 ALR 1; UBS AG v Tyne [2018] HCA 45; (2018) 360 ALR 184.

[16] DL v The Queen [2018] HCA 26; (2018) 356 ALR 197; Mighty River International Ltd v Hughes; Mighty River International Ltd v Mineral Resources Ltd [2018] HCA 38; (2018) 359 ALR 181.

[17] Commissioner of Taxation (Cth) v Tomaras (2018) 362 ALR 253.

[18] Hughes v R [2017] HCA 20; (2017) 344 ALR 187, cited in Lynch and Williams, ‘The 2017 Statistics’ (n 4) 1143 n 32.

[19] (2018) 353 ALR 386.

[20] [2018] HCA 22; (2018) 356 ALR 1.

[21] [2018] HCA 38; (2018) 359 ALR 181.

[22] [2018] HCA 45; (2018) 360 ALR 184.

[23] See Chief Justice Susan Kiefel, ‘Judicial Methods in the 21st Century’ (Speech, Supreme Court Oration, Banco Court, Supreme Court of Queensland, 16 March 2017) (‘Judicial Methods’); Justice Susan Kiefel, ‘The Individual Judge’ (2014) 88(8) Australian Law Journal 554; Justice Virginia Bell, ‘Examining the Judge’ (Speech, University of New South Wales Law Journal Launch of Issue 40(2), 29 May 2017) 2; Justice PA Keane, ‘The Idea of the Professional Judge: The Challenges of Communication’ (Speech, Judicial Conference of Australia Colloquium, Noosa, 11 October 2014).

[25] Michael Coper, Freedom of Interstate Trade under the Australian Constitution (Butterworths, 1983).

[26] Almost a decade ago, professional background was listed alongside gender, ethnicity and geography as an aspect of the Labor Government’s objective of ‘pursuing the evolution of the federal judiciary into one that better reflects the rich diversity of the Australian community’: Attorney-General’s Department, Australian Government, Judicial Appointments: Ensuring a Strong, Independent and Diverse Judiciary through a Transparent Process (September 2012) 1.

[27] For example, the appointments of Justice Edward McTiernan in 1930 or Justice Lionel Murphy in 1975.

[28] Chief Justice Kiefel, ‘Judicial Methods’ (n 23).

[29] Michael Pelly, ‘Chief Justice Susan Kiefel Says High Court Has Changed the Way It Works’, The Australian Financial Review (online, 16 August 2018) <https://www.afr.com/business/legal/chief-justice-susan-kiefel-says-high-court-has-changed-the-way-it-works-20180815-h1412o>.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Chief Justice Kiefel, ‘Judicial Methods’ (n 23) 8.

[32] [1992] HCA 60; (1992) 176 CLR 77.

[33] Louis Henkin, ‘The Supreme Court: 1967 Term’ (1968) 82(1) Harvard Law Review 63, 301–2.

[34] The purpose behind multiple tallying in some cases – and the competing arguments – are considered in Lynch, ‘Dissent’ (n 2) 500–2.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/UNSWLawJl/2019/50.html