University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

THE INGREDIENTS OF SUCCESS FOR EFFECTIVE RESTORATIVE JUSTICE CONFERENCING IN AN ENVIRONMENTAL OFFENDING CONTEXT

HADEEL AL-ALOSI[1]* AND MARK HAMILTON[1]**

Environmental crimes can affect the air we breathe, water we drink, and the land we live on, making it essential to enforce environmental protection laws. Restorative justice conferencing provides a promising way to repair the harm occasioned, offering many benefits over traditional prosecution in court. However, it does have drawbacks and may not be suitable in all cases, raising the question of when it is appropriate to use when dealing with environmental offending. This article sheds light on the benefits and shortfalls of restorative justice in dealing with such offences, as well as proffering indicia that should be considered when assessing offender suitability to engage in conferencing – namely, offender responsibility, as evidenced through contrition and remorse. Such indicia can provide much-needed guidance to the courts, environmental agencies, and lawyers, which will be beneficial for the community and environment as a whole.

Environmental crimes encompass a range of offences that harm, or have the potential to harm, the environment. Broadly, such offences are unlawful acts or omissions that may result in actual or potential harm to the environment. Environmental crimes, which range in severity, include polluting (such as acts contaminating land,[1] air,[2] and water[3]), breaching conditions of an environment protection licence,[4] harming of flora and fauna,[5] and damaging or destructing Aboriginal cultural heritage.[6] Human victims of such crimes include those presently living, future generations, and communities; non-human victims include flora (plants), fauna (animals), ecosystems, and the environment generally. In New South Wales, environmental crimes are usually dealt with by the Land and Environment Court of New South Wales (‘Land and Environment Court’), which has the power to penalise offenders found to have breached the law. Despite the wide availability of orders that the Land and Environment Court can make, it is questionable how effective those orders are in repairing the harm caused to the environment, victims, and the wider community. This is particularly because prosecution provides little, if any, face-to-face dialogue between offender, victims, and other stakeholders,[7] and also because it gives victims little or no input in determining the appropriate penalty that should be imposed on the offender for breaching the law. Restorative justice has much potential in overcoming these limitations of the traditional criminal justice process.

Broadly defined, restorative justice conferencing refers to any process whereby the victim, offender, and any other relevant stakeholders affected by a crime participate collectively in resolving a matter with the assistance of a trained and independent facilitator.[8] It has many benefits in resolving conflict because it provides a forum for the participants to discuss the offence, its impact, and allow the parties to provide input into formulating ways to remedy the harm caused to the environment. Conferencing can also empower victims and repair ruptured relationships. Yet, despite its potential benefits, it has rarely been used in the environmental offending context.

Of course, restorative justice conferencing is not always suitable. Therefore, this article does not advocate for conferencing to replace traditional criminal justice prosecution completely; rather conferencing is seen as complimentary to the process, which we refer to as a ‘back-end model’. It illustrates the importance of embracing restorative justice conferencing as part of the process where offender suitability has been established. This begs the question of what indicia should be used to determine whether conferencing is suitable. There is currently no legislation in Australia guiding the courts in determining offender suitability for conferencing in the context of environmental offending, which may lead to inconsistency and the risk of unsuitable offenders being referred to conferencing. This article fills in the gap by setting out the essential indicia that should be used to assess offender suitability. Such indicia are particularly timely given recent changes to the Land and Environment Court Practice Note: Class 5 Proceedings (‘Class 5 Practice Note’), which contemplates the use of conferencing during criminal proceedings; a contemplation that was not present in the previous version of the Class 5 Practice Note.[9]

The remainder of this article is divided into six parts. To give a background, Part II discusses what restorative justice is, and its benefits and limitations in the context of environmental offending. Part III draws upon the use of restorative justice conferencing to deal with such crimes in New Zealand. That jurisdiction was selected because it provides an exemplary model of the innovative use of conferencing and because New Zealand practice has been influential on Australian environmental courts. Part IV discusses the two reported instances where an Australian court has employed restorative justice conferencing to deal with environmental offending, namely Garrett v Williams (‘Williams’),[10] and Chief Executive, Office of Environment and Heritage v Clarence Valley Council (‘Clarence Valley Council’).[11] These cases highlight the potential of conferencing in repairing the harm occasioned by the offending by facilitating communication between stakeholders and how it allows stakeholder input into the outcomes reached. Williams and Clarence Valley Council are also significant because the offenders demonstrated accepted responsibility for the offending, highlighting the suitability of conferencing. Accordingly, Part V draws upon these cases to proffer indicia that should be used when assessing offender suitability for conferencing, namely, contrition and remorse. Lastly, Part VI summarises the findings of this analysis and reinforces the key ingredients for an effective restorative justice conference.

Restorative justice arose in response to some of the perceived shortcomings of the criminal justice system, in particular, its tendency to neglect victim and offender inclusion in the process.[12] As noted by Zehr, the ‘precedents and roots of restorative justice are much wider and deeper than the initiatives of the 1970s; they reach far back into human history’,[13] and ‘restorative justice represents a validation of values and practices that were characteristic of many indigenous groups’.[14]

However, the birthplace of modern restorative justice practices is said to have first occurred in Ontario (Canada) in 1974.[15] In that instance, which involved the vandalising of 22 properties, the presiding judge in the matter allowed victim-offender mediation.[16] The conference resulted in the offenders offering to pay restitution to the victims.[17] Subsequently, victim-offender conferencing was introduced in the United States in a project conducted in Indiana during 1977 and 1978.[18]

Restorative justice conferencing has since spread throughout the world and been used in a range of circumstances. For example, in New Zealand, family group conferences have been the default response to most juvenile offending since 1989.[19] It arose in response to Maori concerns that the ‘imposed, alien, colonial system’[20] of criminal justice was ‘culturally inappropriate and failed to address underlying issues’.[21] Conferencing facilitated by police in Australia began with a program in Wagga Wagga in 1991.[22] It was a community initiative influenced by the family group conferencing occurring in New Zealand and the reintegrative shaming theory of Braithwaite.[23] This system has since been replaced with a statutory scheme.[24]

There is no universal definition of ‘restorative justice’. As proffered by Hamilton, ‘[r]estorative justice is a multifaceted concept with debate ensuing over exactly what it is and what it involves and, indeed, what it isn’t’.[25] However, it is widely accepted that restorative justice is a theory based on the premise that ‘[c]rime is a violation of people and relationships’;[26] crime is not merely committed against the state.

A widely adopted definition of restorative justice is that provided by Marshall. He defines it as ‘a process whereby all the parties with a stake in a particular offence come together to resolve collectively how to deal with the aftermath of the offence and its implications for the future’.[27] Therefore, restorative justice departs from the traditional principles of the criminal justice approach, which is based primarily on punishing offenders.[28] It also departs from the traditional view that imprisonment is an effective deterrent for future offending.[29]

On an international level, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (‘UNODC’) describes a restorative process as

any process in which the victim and the offender, and, where appropriate, any other individuals or community members affected by a crime, participate together actively in the resolution of matters arising from the crime, generally with the help of a facilitator.[30]

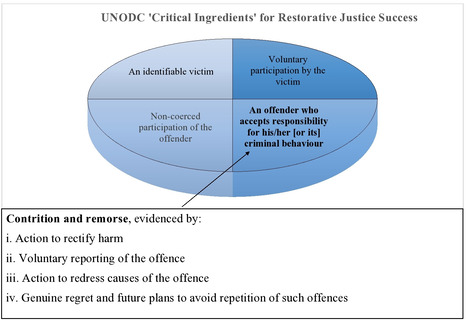

The UNODC has identified four critical elements for the success of any restorative justice process. Although the UNODC’s elements are not binding on Australian courts, they provide useful guidance and are as follows:

2. voluntary participation by the victim;

3. an offender who accepts responsibility for his/her criminal behaviour; and

4. non-coerced participation of the offender.[31]

Our article provides guidance on the third element by setting out indicia that should be used to assess whether an offender demonstrated acceptance for his or her criminal behaviour in the context of environmental offending.[32] It is predicated on the assumption that the UNODC’s critical elements are necessary for restorative justice success to address environmental offending.

The UNODC sets out four main stages that officials (such as police, prosecutors, and judges) can integrate restorative justice conferencing in the criminal justice process:

• pre-charge;

• post-charge but before trial;

• after conviction, but before sentencing the offender; or

• after sentencing the offender (for example, used as an alternative to imprisonment or upon release).[33]

The focus of this article is on the use of restorative justice conferencing after conviction, but before sentencing the offender, which we refer to as a ‘back-end model’ of conferencing. There is not a universal back-end model of restorative justice process; the process works best when it is tailored for the specific context in which it is used. However, there are some typical features of a back-end restorative justice conference. These features include the conference being embedded as part of sentencing and not as a diversion from prosecution; the conference being closed to the public and under the guidance of a trained and independent facilitator; and inclusive in that the relevant stakeholders are welcomed to attend. Voice is an important component of conferencing and the facilitator and stakeholders are to ensure that all voices in the conference are heard.

Typically, a back-end model involves the prosecution bringing charges before the court, the identification of the utility of holding a restorative justice conference (ideally early in proceedings), adjournment of proceedings to allow the conference to occur, and then returning the matter to court for sentencing. The facilitator in Clarence Valley Council, John McDonald, has outlined the four stages of the restorative justice conference using a back-end model, which are illustrated below in Figure 1.[34] It is between stages three and four that the matter is returned to court and may be considered when sentencing the offender.

Figure 1 – Stages in Restorative Justice Conferencing

A back-end model of conferencing can be differentiated from a ‘front-end model’ of conferencing. A front-end model operates as a diversion to prosecution and is commonly used to deal with juvenile offenders who have admitted to the offence by diverting them from court.[35] In this model, a conference is usually held with the offender, victim, facilitator, police, and other relevant stakeholders. Outcomes that may be agreed on may include the offending making an apology to the victim, agreeing to do community service, donating to charity, and so on. Offenders who fail to comply with the outcomes may have their matter dealt with by a court.[36]

While more research is needed on the front-end model of conferencing in specifically dealing with environmental offending,[37] there are some notable limitations with this process that makes a back-end model more appropriate in dealing with environmental crime offenders. In a front-end model, the oversight of the court is lost because, if the conference is successful and the outcomes are adhered to, the matter is not brought before the court. Therefore, the bedrocks of the common law system, such as procedural fairness, and consistent and proportionate punishment, cannot be assured. Building upon this, the threat of prosecution looming may result in some offenders agreeing to outcomes that are more onerous than that a court may have imposed, and lead to non-proportionate and inconsistent outcomes at conferencing.[38] Using a back-end model significantly reduces this problem because the matter is returned to the court following the conference, thereby retaining the courts’ essential supervisory role. The court can amend the restorative justice outcomes to ensure that the statutory purposes of sentencing are met, and that punishment is proportionate and consistent with like cases. The court can also impose further sanctions on the offender in addition to that agreed at conferencing if the outcomes reached appear to be inadequate.

The benefits and limitations of using a back-end model of restorative justice conferencing specifically in the context of environmental crimes are further considered in the following section.

A significant advantage of restorative justice conferencing is the dialogue it facilitates amongst the stakeholders to an offence and its inclusive nature. As noted by Zehr, ‘[r]estorative justice expands the circle of stakeholders ... beyond just the government and the offending party to include those who have been victimized as well as community members’.[39] The main stakeholders are the victim(s) and the offender(s) (in the case of corporate offenders, this includes its directors, managers and employees; in the case of a local council, this includes the mayor, deputy mayor and general manager), and a regulatory authority. Victims of environmental offending are varied and potentially wide-ranging depending on the specific incident. More than one class of victim may be exposed to an environmental offence. Victims may include humans (both currently living and future generations), components of the environment (flora, fauna, ecosystems, etc), communities (both Indigenous and non-Indigenous), and commercial operators. Not all these primary victims have a voice and, therefore, require human guardians to represent them at conferencing.[40]

Additionally, conferencing provides the opportunity for the stakeholders to make solutions, which can be proffered to the court to form the sentence in the matter.[41] Such outcomes may be more innovative than those traditionally made by a court: ‘[i]t is the combined input of many people, especially those most affected, that produces the sort of outcomes the court could not impose and yet are very meaningful to those involved’.[42]

An important aspect of restorative justice conferencing is that an independent person who does not have an allegiance to any of the stakeholders facilitates it; this independence has the added benefit of ensuring impartiality. The United Nations has also developed Basic Principles on the Use of Restorative Justice Programs in Criminal Matters, which sets out safeguards aimed at protecting participants in the process. Some of the principles most relevant in the context of environmental offending include the right of the victim and offender to consult a lawyer, the right to be fully informed before agreeing to participate in a conference, and the right not to participate.[43] Other safeguards are the requirements:

• to ensure any outcomes reached in the conference are made without coercion and contain only reasonable and proportionate obligations;

• that the meeting is not conducted in public and kept confidential (unless the parties consent to disclosure);

• that any outcomes reached should, where appropriate, be judicially supervised or incorporated into a judicial judgment; and

• that any failure to reach an agreement in conferencing not be used against the offender in subsequent criminal proceedings.[44]

Another advantage of restorative justice conferencing is that it can repair the damage caused to the environment. Although it is sometimes difficult to completely repair the damage, for example, where an Aboriginal place or object has been destroyed, this does not mean that conferencing is futile. Actions can be taken to prevent the harm from recurring and help to at least partially restore the environment to its pre-offending state. For instance, the offender may make donations to fund environmental projects focused on the damaged environment,[45] or fund projects designed to raise awareness about the need to protect Aboriginal cultural heritage.[46]

Other key benefits can be gleaned from the key objectives of restorative justice set out by the UNODC, which include:

• giving victims a voice and enabling them to have input into the outcomes to address the harm they have incurred;

• identifying the causes that led to the criminal behaviour;

• encouraging offenders to take responsibility for their actions and the consequences of the offence;

• focusing on repairing the harm done, rather than focusing solely on punishing the offender;

• denouncing criminal behaviour; and

• repairing damaged relationships.[47]

Traditional criminal prosecution tends to silence victims by not giving them an opportunity to express their needs and wishes. As Zehr has argued, modern prosecutions tend not to give victims and offenders the opportunity to participate in the process actively, which results in their needs being neglected.[48] Conversely, victim and offender participation is central to restorative justice. Thus, it has the potential to empower and heal victims by allowing them to ask the offender questions, describe the effect the crime has had on them, and have a say on what they think is an acceptable way to repair the damage caused. A restorative justice conference gives offenders an opportunity to explain the reason for their offending – an explanation that often matters to the victims wanting answers and seeking closure.[49] As well as informing the offender about the impact of the offence on the victims, it may also educate them about the nature, extent, and consequences of the offence on the wider community and the environment. For example, an offender in a conference with Indigenous community members is able to learn about local Aboriginal history and culture.[50] This insight into the harm caused may avoid further environmental harm and lead to actions being put in place to prevent the offending from reoccurring.

Importantly, restorative justice conferencing makes it easier for offenders to assume responsibility for the crime and its consequences. This active acknowledgement and acceptance for the crime committed is superior to a court holding a passive offender guilty and imposing responsibility on him or her.[51] Restorative justice conferencing provides ‘a forum where the defendant acknowledges they have wronged the victim, and the victim’s needs are given some attention by the defendant’.[52] It also creates a forum for offenders to make an apology directly, and in close proximity, to the victim(s). A face-to-face apology allows the audience to assess the genuineness of the apology because they are able to view the offender’s body language, which is an important interpretive tool.[53] A verbal apology can be far more valuable to victims than a written apology in an affidavit or even one given orally from the witness box, circumstances where it is often difficult or impossible to read the offender’s body language and hence determine if it is a sincere apology.

A criminal justice system that integrates restorative justice conferencing does not necessarily preclude a court from imposing other forms of punishment, such as fines and imprisonment. However, its focus is on repairing the harm done rather than punishment. Thus, its emphasis is on the victim and in developing forward-looking outcomes aimed at restoration. This has benefits for the victim, the community, as well as the offender. It also helps prevent reoffending because it steers away from shaming the offender in a stigmatising way. Braithwaite’s concern with the modern criminal justice system is with its potential to deliver stigmatising shame; shame delivered in such a way that the offender is treated as a bad person per se, rather than a good person who has done a bad thing, which is thought to be conducive to reoffending.[54]

Although denunciation is a key objective of the traditional criminal justice system, restorative justice conferencing provides a more flexible way of denouncing criminal behaviour. It takes into account the individual circumstances of the participants and ‘is designed to be a positive denunciation within a larger process, rather than being the sole focus of the intervention’.[55]

Restorative justice conferencing can also help repair relationships ruptured by the crime and facilitate continued interaction between the stakeholders after the meeting. This can help reduce reoffending, identify the underlying causes of the crime, and foster positive relationships into the future.[56] As observed by Clapshaw:

In cases where there has been a discharge of contaminants, odour, dust or fumes detrimental to health and the enjoyment of life, giving neighbours the opportunity to articulate those concerns in a proper forum and agree on appropriate measures to prevent them recurring means the relationship can be rebuilt.[57]

Further, a restorative justice conference provides an opportunity to restore reputation, for example by ‘[c]onfronting the community in the conference and making a formal apology ...’,[58] and responding ‘in a manner that is consistent with personal or corporate values of accountability, transparency and partnership with the community’.[59]

Nevertheless, there are limitations of restorative justice conferencing in dealing with environmental offending that need consideration. A significant drawback is the added costs and time involved in holding a conference; such conferencing ‘is neither easy nor cheap’.[60] The parties may not be able to reach agreement at the conference and, even if they do, the court may reject any or all of the outcomes in the agreement.[61]

In some cases, offenders agree to cover some of the costs associated with conferencing, such as paying for the facilitator’s fees.[62] This can result in some offenders having to ultimately pay an amount that is greater than the penalty a court would have imposed on an offender for breaching the law, and lead to non-proportionate and inconsistent punishment for similar offences. For example, in Canterbury Regional Council v Interflow (NZ) Ltd (‘Interflow’),[63] the corporate offender agreed at conferencing to donate $80,000 to enhance the stream that had been polluted as a result of the offence.[64] The amount donated was more than double what the court would likely have imposed for the breach of the law.[65] Arguably, because attending a conference and the outcomes reached are made voluntarily, a higher compensation payout may be seen as unproblematic and indeed more likely to cover the costs associated in repairing the harm done to the environment. It may even be beneficial for the offender because making a generous allowance to repair the harm may lessen the damage to their reputation and community backlash. Thus, the added time and money involved in a conference may also be seen as a justified investment if the process leads to a better outcome for all those involved.

Conversely, it is possible for the outcomes reached in conferencing to be more favourable to an offender than a penalty imposed by a court. Also, because the outcomes are not binding unless they are made into court orders, any agreement reached in conferencing may not be honoured. A benefit of integrating restorative justice conferencing in the traditional criminal justice system (as opposed to using conferencing as a substitute for prosecution) means that the courts play an essential oversight role in determining the final orders made. When the matter goes back to the court after the conference, the court has the discretion to decline making the outcomes agreed to by the stakeholders into court orders if they are inadequate. A court may even decline to put into court orders outcomes voluntarily reached by the parties that exceed the maximum penalty stated in the legislation. Alternatively, a court can impose a penalty in addition to the agreement reached at conferencing. Maintaining the oversight role of the courts post-conference can assist in achieving consistency in the sanctions imposed on offenders for similar offences. Also, the ability of the courts to make the agreements reached legally binding helps ensure that agreements will be fulfilled because failure to honour binding orders often have legal consequences, such as subjecting the offender to contempt of court proceedings.

Open justice – ‘that justice should not only be done, but should manifestly and undoubtedly be seen to be done’ – is an important principle and feature of the common law legal system.[66] Unlike traditional court trials, which are usually open to the public unless there are some exceptional circumstances, restorative justice conferencing is dealt with privately and therefore is closed to public scrutiny. However, as noted previously, a criminal justice system that integrates restorative justice conferencing means that the court retains the final power in disposing of the matter. Accordingly, because the matter is returned to an open court, members of the public are able to hear the outcomes reached at the conference. Members of the public may also be able to read about the outcomes achieved if a written judgement of the case is available, thereby allowing public scrutiny.

Despite the benefit of conferencing in giving victims a voice and input into the process, it can re-victimise victims. Re-victimisation may occur if an offender does not engage in the process genuinely, does not fully accept responsibility for their offending, or seeks to undermine the effect the crime has had on victims. For example, an offender who has caused damage to a sacred Aboriginal place or object may agree to participate in a conference in the hope that this would lead to a lenient penalty. However, during the conference, the offender may not show remorse and try to diminish the impact of the offending by saying to the victims present: ‘perhaps I did cause some damage to the object, but it was damaged anyway, and I think you are overstating its importance’. Re-victimisation can be avoided by properly assessing an offender’s suitability for conferencing, and the indicia used to assess suitability are discussed later in this article. Before doing so, it is useful to discuss restorative justice conferencing in the environmental offending context in New Zealand and New South Wales to demonstrate the benefits of restorative justice conferencing in dealing with offenders who have accepted responsibility for their offending.

The reason for drawing upon New Zealand is because it has been a leading country in embracing restorative justice conferencing to deal with environmental crimes. It serves as an exemplary model and has been influential in the two Australian environmental cases that have used conferencing. The model of conferencing commonly used in New Zealand is a back-end model discussed above. This means that conferencing does not replace prosecution. Instead, it is integrated into the criminal justice system and occurs as part of the sentencing process, thereby retaining the oversight of the court.

The year 2002 marked the beginning of statutory recognition of restorative justice processes in New Zealand’s criminal justice system. In June 2002, the Sentencing Act 2002 (NZ) commenced operation. Section 8(j) of that Act states that a sentencing judge ‘must take into account any outcomes of restorative justice processes that have occurred, or that the court is satisfied are likely to occur, in relation to the particular case’ (emphasis added). In December that year, section 9 of the Victims’ Rights Act 2002 (NZ) commenced operation. Section 9, as originally enacted, only required a judicial officer, the lawyer for an offender, a member of court staff, a probation officer, or the prosecutor to encourage a meeting between the victim and the offender to resolve issues relating to the offence. This is provided that a suitable person was able to arrange and facilitate the meeting. In December 2014, that section was amended by stating that it applies ‘if a victim requests to meet with the offender to resolve issues relating to the offence’.[67] Upon such a request, and if the necessary resources are available, a ‘member of court staff, a Police employee, or, if appropriate a probation officer must ... refer the request to a suitable person who is available to arrange and facilitate a restorative justice meeting’.[68] Hence, the amendment gave victims greater involvement rights in the process. Between 30 June 2002 and 30 September 2012, conferencing occurred in 33 environmental offending matters.[69] No publications or official reports reveal the number of conferences held after that date, but our research has uncovered nine further conferences that have occurred since 2012 to the time of writing.[70]

It is perhaps the statutory recognition of restorative justice conferencing that has led the courts in New Zealand to utilise conferencing to deal with environmental offending. Conferencing is now relied upon to deal with various environmental offences including pollution offences (such as discharge of offensive odours,[71] discharge of harmful smoke/vapours/fumes,[72] discharge of contaminants,[73] discharge of untreated pig effluent,[74] discharge of human sewage,[75] dust nuisance,[76] operation of an unlawful landfill,[77] and water pollution[78]), and planning offences (such as breach of conditions of development consent,[79] destruction, felling and removal of trees without consent,[80] modification of a Pohutukawa tree,[81] contravention of an abatement order,[82] and disturbance of a foreshore through unlawful earth works[83]).

Additionally, in 2004, the New Zealand Ministry of Justice published eight useful ‘principles of best practice for restorative justice processes in criminal cases’,[84] many of which mirror the UNODC’s ‘critical ingredients’.[85] The New Zealand courts have been guided by these principles and analysis of the relevant environmental offending case law highlights the inclusive nature of restorative justice conferencing. Stakeholders involved in the process include community members,[86] the environment (represented by the council),[87] chairpersons,[88] council officers,[89] councillors,[90] and Indigenous (Maori) people of New Zealand.[91]

New Zealand case law further shows the various types of outcomes reached between the stakeholders in a restorative justice conference, including:

• an apology;[92]

• donations to support a range of organisations (such as community organisations and schools) to fund projects aimed at better protecting the environment;[93]

• publication of a newspaper article educating the community about rural fires and their consequences;[94]

• commitments responding to the offending behaviour (for example dialogue to put the wrong right,[95] a plan to stop the incident reoccurring in the future,[96] an agreement to work with a specific local council to produce a solution to the problem causing the harm,[97] and ongoing consultation[98]);

• payments to compensate for various costs associated with the offending, such as payment of council costs,[99] facilitator costs,[100] and clean-up costs;[101] and

• the undertaking of work (or the payment for that work) to repair the environmental harm caused by the offending and to stop the harm occurring again in the future.[102]

Many of these outcomes are more effective in repairing the harm than the penalty under the relevant legislation and have the additional benefit of being able to amend fractured relationships, which may prevent the offending from reoccurring. As observed by the prosecutor in the Interflow case mentioned in Part II, conferencing was beneficial because ‘[s]o much more was achieved for the stream itself and the Akaroa community than would have been achieved by leaving their involvement at paying a monetary fine and walking away from the damage done’.[103]

As will be seen below, the use of restorative justice conferencing in New Zealand to deal with environmental offending has been influential on Australian courts that have embraced a back-end model as part of the sentencing process.

Unlike New Zealand, there is no legislation providing for the use of restorative justice conferencing to resolve environmental offences in any Australian jurisdiction at the time of writing.[104] Nor are sentencing judges mandated to take into account any outcomes reached in a conference even if the participants were to engage in such a process. This may largely explain why restorative justice conferencing has currently only been used twice in Australia in an environmental offending context. Both instances occurred in the Australian state of New South Wales. The first time the New South Wales Land and Environment Court used restorative justice conferencing was in the 2007 case of Williams; the second time was in 2018 in the case of Clarence Valley Council.

Williams and Clarence Valley Council share many similarities that should be noted. Justice Preston, Chief Judge of the Land and Environment Court, was the trial judge in both cases and both involved offending against Aboriginal cultural heritage in breach of the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 (NSW).[105] The restorative justice conferences in these cases were initiated after the offenders pled guilty but before sentencing, which is consistent with the New Zealand back-end model mentioned above. At this stage, it is usual for the prosecution and defence to lead evidence and make submissions to the court on the appropriate sentence. However, Preston CJ in both Williams and Clarence Valley Council determined that it was best to adjourn the proceedings so that a restorative justice conference could be held. While this created an opportunity for the sentencing judge to consider any of the outcomes reached by the parties after the adjournment,[106] Preston CJ made it clear that a sentencing judge is not bound by any conference outcomes once the matter returned back to the court: ‘the restorative justice intervention is not itself a substitute for the Court determining the appropriate sentence for the offences committed by the defendant’.[107] Another notable similarity between Williams and Clarence Valley Council is that the conferences were both facilitated by John McDonald,[108] a facilitator independent of the Land and Environment Court.

Now that the similarities between these cases have been set out, their specific facts are discussed below separately.

In Williams, the offender Mr Williams (the sole director and secretary of Pinnacle Mines) was prosecuted under the now repealed section 90(1) of the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 (NSW), which provided:

A person who, without first obtaining the consent of the Director-General, knowingly destroys, defaces or damages, or knowingly causes or permits the destruction or defacement of or damage to, an Aboriginal object or Aboriginal place is guilty of an offence against this Act.

Williams had breached section 90(1) three times as a result of his operations. The first two occasions occurred during the construction of a private rail siding to transport ore, which led to the destruction of several Aboriginal artefacts.[109] The artefacts included ‘evidence of quartz stone quarrying, working and tool manufacture, such as stone blades, flakes, cores or flaked pieces. There [were] ... ovens and food processing equipment including grinding dishes and mortar and pestle type equipment’.[110] These artefacts were in two deposits, and therefore their destruction constituted two offences. Before commencing the private rail siding, Williams engaged an expert to prepare a statement of environmental effects. A statement of environmental effects sets out the impact the construction would have on the environment. As part of the preparation of that statement, an archaeologist conducted ‘an archaeological survey of the area upon which the railway siding was proposed to be constructed’,[111] and identified Aboriginal cultural sites.[112] Despite being advised of the cultural sites, and without obtaining consent from the Director-General of National Parks and Wildlife, Williams instructed an earthmoving company to start the construction of the railway siding.[113]

The third breach occurred when a costean was dug across the boundary of a declared Aboriginal place known as the ‘Pinnacles’. That place was described as one where there ‘are three unusual pointy hills that dominate the skyline south of Broken Hill. To the Aboriginal people, the Pinnacles are central to a living Bronze Wing Pigeon story line’.[114] Williams, who was supervising a program of excavating costeans, ‘was aware of the designation of the Pinnacles as an Aboriginal place’.[115] Although Williams observed the excavator contractor to be excavating in an area known to be within an Aboriginal place, he did not direct the contractor to stop excavation,[116] giving rise to the third offence. Williams was subsequently prosecuted for breaching section 90(1) on three occasions.[117]

Williams ultimately pled guilty to the offences,[118] but before sentencing, Preston CJ recommended the parties to participate in a restorative justice conference. Preston CJ reinforced many of the benefits of restorative justice conferencing has over sentencing in the traditional way (as were discussed above):

The conference offers victims an opportunity to meet the offender in a safe, structured setting and engage in a mediated discussion of the crime. With the assistance of a trained facilitator, the victims are able to tell the offender about the crime’s physical, emotional or financial impact; receive answers to questions about the crime and the offender; and be directly involved in developing a plan for the offender to make reparation or restitution for harm caused to the victims ...[119]

Preston CJ also believed that conferencing was suitable in this case because it would allow the victims to be ‘involved in developing a plan for the offender to make reparation or restitution for harm caused to the victims’.[120] Upon obtaining commitment from the relevant stakeholders, a conference was held and attended by the offender and victims (represented by Ms Maureen O’Donnell and other members of the Broken Hill Local Aboriginal Land Council), which enabled:

[C]onstructive dialogue to be established ... Representatives of the Broken Hill [Local] Aboriginal Land Council were able to share information about the Aboriginal objects and the Aboriginal Place and their significance to the Aboriginal people of the area. The defendant was able to share information about Pinnacle Mines’ operations and the business issues confronting the defendant.[121]

At the conclusion of the conference, several outcomes were reached, including:

• the seeking of solutions to prevent the occurrence of similar offences;

• the facilitation of a site visit and tour of Pinnacle Mines for the Broken Hill Local Aboriginal Land Council;

• Mr Williams paying for Ms O’Donnell’s expenses to travel from Broken Hill to Sydney so that she could be present at the sentencing hearing;

• ongoing interaction between the Broken Hill Local Aboriginal Land Council and Pinnacle Mines (presumably to strengthen the relationship between the parties and give the victims greater say on future operations that may impact the Pinnacle Mines);

• if the parties agreed to work together and form a voluntary conservation agreement in the future, Mr Williams’ agreement to provide the Broken Hill Local Aboriginal Land Council with a vehicle to visit the Pinnacle Mines; and

• Mr Williams’ agreement to teach eligible Aboriginal people the skills necessary to work at Pinnacle Mines.[122]

Additionally, Mr Williams paid the facilitator’s costs of $11,000.[123] After the conference, but before sentencing, Mr Williams also agreed to establish a Wilykali Pinnacles Heritage Trust, in which he donated a vehicle, trailer, quad bike and fuel card (cumulatively valued at $32,200).[124] It was also agreed that the Wilykali people, who are the local Aboriginal people of the area, would be involved in any Aboriginal cultural heritage salvage work.[125] These post-conferencing outcomes highlight the potential of restorative justice conferencing in amending the damaged relationship between the offender and victim, as well as its ability to facilitate positive outcomes even after the conference has concluded.

At the time the offences occurred, breach of section 90(1) carried a maximum penalty of $5,500 and/or six months’ imprisonment.[126] Thus, the conferencing outcomes may be seen as desirable because the maximum penalty under the legislation (which the court is unlikely to have awarded) is arguably an inadequate penalty to compensate for the harm Williams caused to the Pinnacles. The expenses incurred did not prevent the court from imposing an additional penalty on Williams when the matter returned for sentencing. Nevertheless, Williams’ participation in the conference and ‘the significant costs’ he had ‘incurred in and as a result of the conference’[127] led Preston CJ to hold that Williams should only be fined an additional $1,400 for all three offences under section 90(1).[128]

In Clarence Valley Council the offender, Clarence Valley Council (‘the Council’), pled guilty to damaging an Aboriginal object (a scar tree) through the actions of its employees. The scar tree was cut into four pieces, including a cut through a lower scar with the remnants transported to the Council’s nursery.[129] The Council knew the scar tree was protected by law and ‘culturally significant to the local Gumbaynggirr people’.[130] Upon realising that removing the scar tree constituted an offence, the Council reported the incident to the prosecuting authority.[131] Subsequently, the Council was prosecuted for the destruction of an Aboriginal object under section 86(1) of the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 (NSW), which states: ‘[a] person must not harm ... an object that the person knows is an Aboriginal object’.

At the end of the first day of the sentencing hearing, the Council ‘readily agreed to participate’ in a restorative conference with the representatives of the Aboriginal communities whose cultural heritage had been harmed by the offence (the victims).[132] Although it is not expressly stated in the judgment why the Council was so eager to participate in the conference, as mentioned above, engaging in the process may benefit offenders who seek to lessen the damage their offending has on their reputation. The Council’s eagerness may also be because one of the guiding principles in the Local Government Act 1993 (NSW) is for a council is to ‘act fairly, ethically and without bias in the interests of the local community’.[133] The cutting down of a culturally significant scar tree is clearly a violation of that principle. This violation prompted the need to rectify that wrong, and participation in a restorative justice conference facilitating interaction with the Indigenous community is one way to right the wrong.

It is not clear from the written judgment who initiated the restorative justice conference; presumably, Preston CJ suggested conferencing, just as his Honour did in Williams.[134] The victims present at the meeting were the representatives of the Aboriginal communities whose cultural heritage had been harmed as a result of the removal of the scar tree.[135] Also in attendance were various members of the Clarence Valley Council including the mayor, deputy mayor, general manager, and the Council field officers who had removed the scar tree. Hence, various levels of the organisation were engaged in the restorative justice conference. The communication between the participants at the conference was described in the judgment as:

respectful, at times emotional, deeply personal, and was undertaken such that all participants had time to talk through their understanding of what happened, the impact it had on all present as Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people, and the impact it has had on Aboriginal communities more broadly.[136]

At the conclusion of the conference, it was agreed that the Council should make a donation ‘to the Grafton Ngerrie Local Aboriginal Land Council to be utilised for work related to increasing awareness of local Aboriginal history and culture both inside the Council and across the Clarence Valley area generally’.[137] When the matter returned back to the court for sentencing, Preston CJ determined the quantum of that donation to be $300,000.[138] His Honour also made a training establishment order, which was agreed to at the conference, requiring the Council to establish a cultural skills development workshop for its field staff and managers.[139] The Court also ordered the Council to publicise its offending by having it publish the details of the offending on several media platforms including newspapers and the Council’s Facebook and website.[140]

Like in Williams, the conferencing outcomes reached in Clarence Valley Council were aimed at physically repairing the harm caused to the environment as far as possible, preventing the offending reoccurring, and amending the relationship between the offender and victim(s). The specific outcomes reached in Clarence Valley Council were focused on:

• supporting the Council’s staff (including senior managers and planners) to engage more effectively with Aboriginal people;

• increasing positive recognition of Aboriginal people in the Clarence Valley Council community;

• improving consultation with local Aboriginal people via the Clarence Valley Aboriginal Advisory Committee;

• creating employment opportunities and youth initiatives for Aboriginal people in the Clarence Valley Council area; and

• establishing the Scar Tree Restoration and Interpretation Project to address the site destruction and the use of the remaining timber from the scar tree.[141]

These outcomes are more beneficial to victims than what a court would have imposed if the matter did not go to conferencing. Even if the court were to have imposed on the Council the maximum penalty for a breach of section 86(1) of the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 (NSW), which is a maximum of $1,100,000 for a corporation, the money would have to be sent to the New South Wales government’s consolidated revenue fund.[142] Once the money is deposited into the fund, the government is not obliged to spend it on the costs associated with the offending.

Notably, the restorative justice conference allowed for apology:

The Council’s Mayor, Deputy Mayor and General Manager and the field operations staff in attendance at the restorative justice conference personally apologised to the Aboriginal people present for what had happened and for the emotional harm caused.[143]

Additionally, the Council published a public apology, in the form of a letter signed by the Mayor and the General Manager, in two local newspapers.[144] The power of making a public apology is that it can be an effective deterrent against future offending.

There are major benefits of integrating restorative justice conferencing in the prosecution of environmental offending. Those benefits were demonstrated in the analysis above of the only two cases in Australia, to date, to have used restorative justice conferencing – Williams and Clarence Valley Council. In both of these cases, the offenders accepted responsibility for their actions, making them ideal candidates for restorative justice conferencing. The need to assess offenders’ suitability to determine if they take responsibility before referring them to conferencing is an issue we turn to next.

As demonstrated above, restorative justice conferencing holds promise in dealing with environmental offending and has advantages that cannot otherwise be achieved by traditional prosecution. However, it was also noted that restorative justice conferencing might not be suitable in all cases, making it essential that offenders are properly assessed before referring them to restorative justice. We recommend that the assessment should be centred upon an offender’s contrition and remorse as the key indicia when determining the suitability of referring the parties to a conference. Figure 2 (below) illustrates how contrition and remorse fit with the UNODC’s ‘critical ingredients’ for restorative justice.

Figure 2 – Offender suitability for conferencing indicia

As emphasised by the UNODC and shown in Figure 2, an essential element of restorative justice success is that an offender ‘accepts responsibility for his/her [or its] criminal behaviour’.[145] Under the New Zealand Ministry of Justice’s principles of best practice for restorative justice, it is also a requirement that the ‘offender must acknowledge responsibility for the offence before a case can be referred to, or accepted for, a restorative justice process’.[146] The effectiveness of conferencing in facilitating dialogue between stakeholders requires the offender taking responsibility for their actions and communicating the reasons for their behaviour to the victim(s). The potential advantages of conferencing are lost, or significantly undermined, if an offender does not accept responsibility for the offence because it can lead to re-victimisation, especially if the offender seeks to diminish the impact of the offending on the victims.[147] Accordingly, it is vital that offenders demonstrate they have accepted liability for the offence before any conference goes ahead.

It is tempting to argue that a guilty plea is the strongest indicator of responsibility for the offence; the plea may demonstrate that the offender believes they have done wrong, and therefore accepts responsibility. As noted by Pain et al in their article drawing a link between guilty pleas and offender culpability:

One factor suggests that environmental crime is well-suited to restorative justice. At least in NSW, where environmental crime largely comprises strict liability offences, a high number of guilty pleas are achieved. Because accepting culpability is an important factor for the legitimacy of any restorative outcome, this suggests that such offenders will be predisposed to such an outcome.[148]

However, we argue that a guilty plea is not of itself a reliable indicator that the offender has taken responsibility for breaching the law. This is because it may have been entered on the belief that conviction is inevitable, especially where the offence is one of strict liability. A strict liability offence, which evidence shows dominate New South Wales environmental law,[149] is where the action comprising the offence (actus reus) is all that is required for conviction; proof of the mental state (mens rea) of the offender is not required. A strict liability offence is relatively easier to prove than offences that need proof that not only did the offender commit the wrongful act, but also that he or she had had the requisite guilty mind at the time of committing the offence. An example of a strict liability offence is section 120(1) of the Protection of the Environment Operations Act 1997 (NSW), which states: ‘[a] person who pollutes any waters is guilty of an offence’. To establish a breach of this section, it is sufficient for the prosecution to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that (a) waters have been polluted; and (b) the pollutant came from the offender’s operations or actions. It is irrelevant whether the offender committed the offence knowingly, recklessly, or even negligently for the purposes of section 120(1).

Another reason an offender may plead guilty is to avail themselves of the discount given for making such a plea. Depending on when the guilty plea was entered, the discount can range from 10 to 25%.[150] It is for its perceived utilitarian value that a discounted penalty is primarily given; a guilty plea, especially one made early, saves court time and resources by circumventing the need for a contested trial. The discount and the inevitability of conviction provide some offenders compelling reasons to enter a guilty plea, even though they may not subjectively believe they are guilty.

Indeed, an offender may enter a guilty plea for a combination of reasons, some of which are not discussed in detail here. This includes entering a plea of guilty on the advice of a lawyer, to avoid the costs of having to defend the charge(s), or simply because the offender wants to get the matter finalised quickly. What is important to note is that the plea should not be relied upon as the indicator that the offender takes responsibility for the offence. A more reliable indicator is contrition and remorse.

Contrition and remorse often go hand-in-hand with acceptance of responsibility. As stated by Kirby J, there ‘can be no real remorse without an acceptance of responsibility’.[151] Contrition is defined as ‘deeply felt remorse; penitence’, whereas remorse is the ‘strong feeling of sadness and regret about something wrong that you have done’.[152] Despite this subtle difference, the courts use the terms contrition and remorse interchangeably, with some judges not detecting ‘any meaningful distinction between’ the two terms.[153] Howie AJ (Allsop P agreeing at [1], Adams J agreeing at [9]) has expressed that ‘[f]or the purposes of sentencing, I do not understand that there is any relevant difference between contrition and remorse, whatever subtle distinction might be draw[n] between the two words in the richness of the English language’.[154]

The courts are generally accustomed to assessing an offender’s contrition and remorse because it is relevant when sentencing the offender.[155] The practice of taking into account contrition and remorse can be traced to the common law, and case law sheds light about the relevance of these two factors. In Neal v The Queen (‘Neal’) it was stated that ‘[c]ontrition, repentance and remorse after the offence are mitigating factors, leading in a proper case to some, perhaps considerable, reduction of the normal sentence’.[156] Neal was influential on the New South Wales Court of Appeal in Camilleri’s Stock Feeds Pty Ltd v Environment Protection.[157] In the latter case, which involved environmental offending, a mitigating factor that substantially reduced the penalty imposed was the offender’s demonstrated contrition and remorse.

Today, legislation in many jurisdictions explicitly states that contrition and remorse must be taken into account when determining an appropriate penalty for an offence. For example, in New South Wales, section 21A(3)(i) of the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act 1999 provides that remorse is a mitigating factor to be taken into account,[158] but only if

(i) the offender has provided evidence that he or she has accepted responsibility for his or her actions, and

(ii) the offender has acknowledged any injury, loss or damage caused by his or her actions or made reparation for such injury, loss or damage (or both).

Drawing upon Land and Environment Court case law, Preston CJ identified a range of actions demonstrating contrition and remorse.[159] This included the speed and efficiency of the offender’s actions to rectify the harm caused (or likely to be caused), whether the offender voluntarily reported the offence to the relevant authorities, and whether the offender took any action to redress the causes of the offending.

When the offender is an individual, such as a director in the case of Williams, assessing their level of contrition and remorse is relatively straightforward. However, how would the assessment be conducted when the offender is an organisation, corporation, or government entity (as in Clarence Valley Council)? Should the assessment be conducted on the directors, employees, or both? What if some of the employees are remorseful but the directors are not? In cases where an entity causes the harm, we suggest that it is the contrition and remorse of those that control that organisation that should be assessed in determining offender suitability for conferencing. This is because these individuals, such as directors and senior management, are the ones who hold the power to bind the organisation to the outcomes agreed at conferencing. Preston CJ has also given guidance when the offender is a corporation, stating that contrition and remorse may be evidenced by looking at the ‘personal appearance of corporate executives in court and their personal evidence outlining the company’s genuine regret and stating future plans to avoid repetition of such offences’.[160]

Although a benefit of restorative justice conferencing is that it provides a forum for the offender to realise the wrong they have committed and apologise directly to the victim(s), it is essential that the offender show remorse before being referred to conferencing. This is particularly to avoid the risk of re-victimisation by engaging in the process with an offender who refuses to take responsibility for their offending and who seeks to undermine the harm caused. An apology made genuinely and voluntarily is a useful indicator of remorse because it evinces regret for the offending. In Williams, Preston CJ was persuaded that restorative justice conferencing was suitable because Williams demonstrated genuine contrition and remorse in various ways. He gave evidence in court that he was ‘sorry’ and ‘seriously remorseful’ for the harm caused by committing the offence.[161] He also showed a commitment to implement steps to prevent the offences from occurring again:

I will ensure that I will get proper archaeological advice prior to undertaking any work where there is a risk of disturbance to or destruction of Aboriginal objects. If it is necessary, I will apply for a consent under s 90 of the National Parks and Wildlife Act before undertaking any work which is likely to result in the disturbance or destruction of Aboriginal objects. Also, if there is to be any additional work which is approaching the boundary of the Aboriginal place, I will ensure that that area is surveyed so as to ensure that the work does not take place within the Aboriginal place.[162]

Additionally, Williams assisted the prosecuting authority by engaging in ‘a videoed walk through interview on site explaining the activities that constituted the offences’.[163]

In Clarence Valley Council, the offender made an apology to the victims both before and during the conference. The Council demonstrated contrition and ‘extreme remorse’ by making an apology that was made ‘unreservedly’ to ‘the Aboriginal communities of the Clarence Valley’,[164] and had made their apology public in two local newspapers before the conference.[165] The Council further showed contrition and remorse by their voluntary and swift reporting of their offending to the relevant regulatory authority.[166] These actions are more reliable in evidencing acceptance of responsibility for the offending than just a guilty plea that, as seen above, can be entered for reasons that do not demonstrate acceptance of liability.

Although it is not being used to its full potential in Australia, a back-end model of restorative justice conferencing, similar to that used in New Zealand, offers an effective way of dealing with environmental crime. Its benefits, many of which cannot be gained in traditional prosecution, include facilitating dialogue between the stakeholders to the offence, repairing the harm occasioned as far as possible, preventing reoffending, building relationships, giving victims a voice in the process, and allowing stakeholders to have input when determining the appropriate way to make amends. There are many lessons and useful guiding principles that can be learnt from the use of New Zealand, which has given legislative recognition to restorative justice processes in its criminal justice system.

Also useful are the United Nations ‘critical ingredients’ for an effective restorative process. In summary, the necessary ingredients set out by UNODC are: an identifiable victim, an offender who accepts responsibility for their offending, and the requirement that both these parties voluntarily engage in the conference.[167] In this article, we have added to the recipe the importance of contrition and remorse as evidence that the offender has accepted responsibility. A plea of guilty should not be used as the sole indicator of suitability for conferencing given its limitations set out above. It is hoped that this article provides those working in the area of environmental crime guidance on when restorative justice conferencing is suitable and to encourage its use as far as possible so that offenders, victims and the community can reap the many benefits it offers.

* Lecturer and lawyer. LLB/Social Science (Criminology) (Hons) (UNSW); PhD (UNSW). Correspondence to Dr Hadeel Al-Alosi: H.Al-Alosi@westernsydney.edu.au.

** Sessional tutor/lecturer and lawyer. BSC, LLB (UoW); MEL, LLM (USyd); MPP (Macq).

Both authors contributed equally in the production of this article. It is based on Mark’s PhD which is being undertaken at UNSW (Law) and is due to be submitted in late 2019.

[1] See, eg, Protection of the Environment Operations Act 1997 (NSW) pt 5.6.

[2] See, eg, ibid pt 5.4.

[3] See, eg, ibid pt 5.3.

[4] See, eg, ibid s 64.

[5] See, eg, Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 (NSW) pt 2.

[6] See, eg, National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 (NSW) s 86.

[7] Even though some courts will allow a victim to read a Victim Impact Statement during the proceedings such practice is not a part of the prosecution of environmental offending before the Land and Environment Court. Some victims may become a witness for the prosecution and provide affidavit evidence about the effect the offending has had on them, but this is not invariably the case.

[8] See United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, ‘Handbook on Restorative Justice Programmes’ (Handbook, United Nations, 2006) 7.

[9] Land and Environment Court of New South Wales, Practice Note: Class 5 Proceedings, 29 March 2018.

[10] [2007] NSWLEC 96; (2007) 151 LGERA 92 (‘Williams’).

[11] [2018] NSWLEC 205 (‘Clarence Valley Council’).

[12] Nils Christie, ‘Conflicts as Property’ (1977) 17(1) British Journal of Criminology 1; Howard Zehr, Changing Lenses: Restorative Justice for Our Times (Herald Press, 25th Anniversary ed, 2015) chs 2–3; Howard Zehr, The Little Book of Restorative Justice: Revised and Updated (Good Books, 2015) (‘The Little Book of Restorative Justice’).

[13] Zehr, The Little Book of Restorative Justice (n 12) 19.

[14] Zehr, Changing Lenses: Restorative Justice for Our Times (n 12) 234.

[15] Ibid 159–60; Michael S King, ‘Restorative Justice, Therapeutic Jurisprudence and the Rise of Emotionally Intelligent Justice’ [2008] MelbULawRw 34; (2008) 32(3) Melbourne University Law Review 1096, 1104.

[16] Zehr, Changing Lenses: Restorative Justice for Our Times (n 12) 159–60.

[17] King (n 15) 1104.

[18] Zehr, Changing Lenses: Restorative Justice for Our Times (n 12) 160.

[19] Zehr, The Little Book of Restorative Justice (n 12) 6, 62.

[20] Ibid 62.

[21] King (n 15) 1104.

[22] Ibid 1105.

[23] Braithwaite’s shaming theory focuses on two types of shame. Stigmatising shame occurs when punishment is delivered in such a way that the offender is treated as a bad person per se, rather than a good person who has done a bad thing. Stigmatising shame is associated with modern court processes and is thought to be conducive to reoffending because it pushes offenders to criminal subcultures which provide criminal role models through which offenders can reject those that have rejected them. Reintegrative shame is shame directed toward the offence and not the offender. When reintegrative shame is delivered with reintegrative gestures or ceremonies to reintegrate the offender back into society, it is thought to be productive: John Braithwaite, Crime, Shame and Reintegration (Cambridge University Press, 1989). For a discussion on the influence of Braithwaite’s theory on the Wagga Wagga program, see King (n 15) 1105.

[24] Young Offenders Act 1997 (NSW) pt 5.

[25] Mark Hamilton, ‘Restorative Justice Intervention in a Planning Law Context: Is the “Amber Light” Approach to Merit Determination Restorative?’ (2015) 32(2) Environmental and Planning Law Journal 164, 164.

[26] Zehr, Changing Lenses: Restorative Justice for Our Times (n 12) 183.

[27] Tony F Marshall, ‘The Evolution of Restorative Justice in Britain’ (1996) 4(4) European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research 21, 37.

[28] Jacqueline Joudo Larsen, Restorative Justice in the Australian Criminal Justice System (Australian Institute of Criminology Reports: Research and Public Policy Series No 127, 2014) 1–2.

[29] Ibid.

[30] United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (n 8) 7.

[31] Ibid 8.

[32] Arguably, restorative justice conferencing may be effective even where an offender does not initially accept blame for the offence. For example, by engaging in a conference, which provides a forum for the victim to express the impact the crime has on him or her, the offender might come to realise the gravity of their offending and the harm it has caused, and subsequently accept responsibility for it. Further research is needed to explore whether, for example, a restorative justice process would be effective where an offender has not accepted responsibility for offending.

[33] United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (n 8) 13–14.

[34] [2018] NSWLEC 205, [13]–[22] (Preston CJ).

[35] Larsen (n 28) 1, 11.

[36] An example from New Zealand is Environment Canterbury’s ‘Alternative Environmental Justice’. Under this front-end/diversionary model of restorative justice, charges are laid against an offender in court and the offender then attends conferencing. If the prosecutor (Environment Canterbury) is satisfied with the outcomes of the conference it seeks leave of the court to withdraw the charges against the offender. For an overview, see Margaret McLachlan, ‘Environmental Justice in Canterbury’ (2014) 37(4) Public Sector 22; Environment Canterbury Regional Council, Resource Management Act Monitoring and Compliance Section: Guidelines for Implementing Alternative Environmental Justice (Report No R12/81, August 2012).

[37] For example, the use of the front-end model of conferencing to derive enforceable undertakings. For an overview, see Christine Parker, ‘Restorative Justice in Business Regulation? The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission’s Use of Enforceable Undertakings’ (2004) 67(2) Modern Law Review 209. re

[38] The juvenile justice system in New South Wales is premised on a diversionary scheme. Young offenders can be referred to youth justice conferencing by the police, the Department of Public Prosecutions and even the courts. There are some safeguards which are built into the scheme which help overcome some of the dangers of the front-end model: the scheme is enshrined in part 5 of the Young Offenders Act 1997 (NSW); outcomes must be realistic and appropriate, with sanctions being no more severe than those that might have been imposed in court proceedings for the offence concerned (this ensures proportionate punishment): at s 52(6)(a); the child subject to conferencing has the right of veto over an outcome plan: at s 52(4); and no further criminal proceedings can be brought against the child for the offence in which a conference was convened and in which the outcome agreement has been successfully completed: at s 58.

[39] Zehr, The Little Book of Restorative Justice (n 12) 21.

[40] Chief Judge Brian J Preston, ‘The Use of Restorative Justice for Environmental Crime’ (2011) 35(3) Criminal Law Journal 136, 143–5.

[41] Deborah Clapshaw, ‘Restorative Justice in Resource Management Prosecutions: A Facilitator’s Perspective’ (2009) 8 Resource Management Bulletin 53, 54–5.

[42] Judge FWM McElrea, ‘The Role of Restorative Justice in RMA Prosecutions’ (2004) 12(3) Resource Management Journal 1, 12.

[43] Basic Principles on the Use of Restorative Justice Programmes in Criminal Matters, ESC Res 2000/14, UN Doc E/2000/INF/2/Add.2 (27 July 2000) annex (‘Preliminary Draft Elements of a Declaration of Basic Principles on the Use of Restorative Justice Programmes in Criminal Matters’) arts 12(a)–(c).

[44] Ibid arts 7, 13–15.

[45] See, eg, Clarence Valley Council [2018] NSWLEC 205 where an outcome of the restorative justice conference was ‘a Tree Restoration and Interpretation Project directly related to the Scar Tree’: at [19] (Preston CJ).

[46] See, eg, ibid where an outcome of the conference (made into a court order) was the donation of $300,000 to Grafton Ngerrie Local Aboriginal Land Council for various activities to raise awareness of Aboriginal cultural heritage: at [120], [130] (Preston CJ).

[47] United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (n 8) 9–11.

[48] Zehr, Changing Lenses: Restorative Justice for Our Times (n 12) 67.

[49] Christie (n 12) 9. See also Hamilton, ‘Restorative Justice Intervention in a Planning Law Context: Is the “Amber Light” Approach to Merit Determination Restorative?’ (n 25) 175.

[50] See, eg, Clarence Valley Council [2018] NSWLEC 205.

[51] United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (n 8) 11.

[52] Chris Fowler, ‘Environmental Prosecution and Restorative Justice’ (Summary, Adderley Head, May 2016) 3.

[53] Mark Hamilton, ‘Restorative Justice Conferencing in an Environmental Protection Law Context: Apology and Corporate Offending’ (2017) Internet Journal of Restorative Justice, 5 Year Celebration Special Issue, ISSN (online): 2056–2985, 7.

[54] Braithwaite (n 23).

[55] United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (n 8) 10.

[56] Ibid; Zehr, Changing Lenses: Restorative Justice for Our Times (n 12) 183–4.

[57] Clapshaw (n 41) 54.

[58] Ibid.

[59] Fowler (n 52) 3.

[60] Ibid.

[61] Ibid.

[62] See, eg, Williams [2007] NSWLEC 96; (2007) 151 LGERA 92, 113 [113] (Preston CJ).

[63] [2015] NZDC 3323 (‘Interflow’).

[64] Ibid [43] (Borthwick DCJ).

[65] The Court stated that the appropriate fine in the circumstances of the case would have been $33,750 but in light of the donation did not impose a fine: ibid [42], [47] (Borthwick DCJ).

[66] R v Sussex Justices; Ex parte McCarthy [1923] EWHC KB 1; [1924] KB 256, 259 (Lord Hewart CJ).

[67] See Victims’ Rights Amendment Act 2014 (NZ) s 6.

[68] Victims’ Rights Act 2002 (NZ) s 9(2) (emphasis added).

[69] Ministry for the Environment (NZ), A Study into the Use of Prosecutions under the Resource Management Act 1991: 1 July 2008 – 30 September 2012 (Report, October 2013) 23.

[70] Interflow [2015] NZDC 3323; Southland Regional Council v Taha Asia Pacific Ltd [2015] NZDC 18010; Auckland City Council v Toa [2015] NZDC 20678; Auckland Council v Andrews Housemovers Ltd [2016] NZDC 780; Tasman District Council v Mytton [2017] NZDC 9820; Bay of Plenty Regional Prosecutor v Withington [2018] NZDC 1800; Southland Regional Council v Baird [2018] NZDC 11941; Auckland Council v MJ Green Ltd [2018] NZDC 17091; Waikato Regional Council v Taharoa Mining Investments Ltd [2018] NZDC 24843. The exact number of conferences occurring after 30 September 2012 is difficult to ascertain due to several reasons. This includes the fact that internet searches do not always reveal official statistics on the use of restorative justice processes in an environmental and planning offending context: see, eg, Ministry for the Environment (NZ) (Web Page) <https://www.mfe.govt.nz/>; Ministry of Justice (NZ) (Web Page) <https://www.justice.govt.nz>; District Court of New Zealand (Web Page) <http:// www.districtcourts.govt.nz/> . Another reason is that not all environmental and planning prosecution sentencing remarks (ie, judgments) are published. Searches were made using New Zealand Legal Information Institute (Web Page) <http:// www.nzlii.org> and the District Court website, which publishes decisions of interest to the public: District Court of New Zealand (Web Page) <http:// www.districtcourts.govt.nz/> . The Ministry of Justice (NZ) (Web Page) <https://www.justice.govt.nz> only publishes Supreme Court, Court of Appeal and High Court judgments.

[71] Auckland Regional Council v Times Media Ltd (Auckland District Court, McElrea DCJ, 16 June 2003), discussed in RM Fisher and JF Verry, ‘Use of Restorative Justice as an Alternative Approach in Prosecution and Diversion Policy for Environmental Offences’ (2005) 11(1) Local Government Law Journal 48, 57; Auckland Regional Council v Avalanche Coffee Ltd (Auckland District Court, Smith DCJ, 28 April 2010).

[72] Tasman District Council v Mytton [2017] NZDC 9820.

[73] Bay of Plenty Regional Council v Thomas (Tauranga District Court, Smith DCJ, 16 March 2010); Canterbury Regional Council v Knight (Christchurch District Court, Jackson DCJ, 18 March 2010); Southland Regional Council v Taha Asia Pacific Ltd [2015] NZDC 18010; Tasman District Council v Mytton [2017] NZDC 9820; Southland Regional Council v Baird [2018] NZDC 11941.

[74] Waikato Regional Council v PIC New Zealand Ltd (Auckland District Court, McElrea DCJ, 29 November 2004), discussed in Fisher and Verry (n 71) 58.

[75] Waikato Regional Council v Matamata-Piako District Council (Morrinsville District Court, Thompson DCJ, 6 May 2005), discussed in Ministry for the Environment (NZ), A Study into the Use of Prosecutions under the Resource Management Act 1991: 1 July 2001 – 30 April 2005 (Report, February 2006) 24.

[76] Manukau City Council v Specialised Container Services (Auckland) Ltd (Auckland District Court, McElrea DCJ, 16 February 2009), discussed in Clapshaw (n 41) 55.

[77] Northland Regional Council v Fulton Hogan Ltd (Whangarei District Court, Newhook DCJ, 6 May 2010), discussed in Ministry for the Environment (NZ), A Study into the Use of Prosecutions under the Resource Management Act 1991: 1 July 2008 – 30 September 2012 (n 69) 63.

[78] Interflow [2015] NZDC 3323.

[79] Waikato Regional Council v Hamilton City Council (Hamilton District Court, Whiting DCJ, 1 March 2005), discussed in Ministry for the Environment (NZ), A Study into the Use of Prosecutions under the Resource Management Act 1991: 1 July 2001 – 30 April 2005 (n 75) 24.

[80] Auckland City Council v L&L’s Co (name suppressed) (Auckland District Court, McElrea DCJ, 11 April 2005), discussed in Ministry for the Environment (NZ), A Study into the Use of Prosecutions under the Resource Management Act 1991: 1 July 2001 – 30 April 2005 (n 75) 25; Auckland City Council v 12 Carlton Gore Road Ltd (Auckland District Court, McElrea DCJ, 11 April 2005), discussed in Fisher and Verry (n 71) 58; Auckland City Council v Shaw [2006] DCR 425; Auckland City Council v Toa [2015] NZDC 20678; Auckland Council v Andrews Housemovers Ltd [2016] NZDC 780.

[81] Auckland Council v MJ Green Ltd [2018] NZDC 17091.

[82] Waikato Regional Council v Huntly Quarries Ltd [2004] DCR 156.

[83] Bay of Plenty Regional Prosecutor v Withington [2018] NZDC 1800.

[84] Ministry of Justice (NZ), Restorative Justice: Best Practice in New Zealand (Report, 2014) 12–26. These principles are: (1) restorative justice processes are underpinned by voluntariness; (2) full participation of the victim and offender should be encouraged; (3) effective participation requires that participants (particularly the victim and offender) are well-informed; (4) restorative justice processes must hold the offender accountable; (5) flexibility and responsiveness are inherent characteristics of restorative justice; (6) the emotional and physical safety of participants is an overriding concern; (7) restorative justice providers (and facilitators) must ensure the delivery of an effective process; and (8) restorative justice processes should only be undertaken in appropriate cases.

[85] United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (n 8) 8.

[86] Such as local residents: Auckland Regional Council v Times Media Ltd (Auckland District Court, McElrea DCJ, 16 June 2003), discussed in Fisher and Verry (n 71) 57; Auckland City Council v 12 Carlton Gore Road Ltd (Auckland District Court, McElrea DCJ, 11 April 2005), discussed in Fisher and Verry (n 71) 58; Auckland Regional Council v PVL Proteins Ltd [2008] DCR 84; Auckland Regional Council v Avalanche Coffee Ltd (Auckland District Court, Smith DCJ, 28 April 2010).

[87] See, eg, Auckland City Council v 12 Carlton Gore Road Ltd (Auckland District Court, McElrea DCJ, 11 April 2005), discussed in Fisher and Verry (n 71) 58.

[88] See, eg, Waikato Regional Council v Huntly Quarries Ltd [2004] DCR 156.