University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

STILL AWAITING CLARITY: WHY VICTORIA’S NEW CIVIL LIABILITY LAWS FOR ORGANISATIONAL CHILD ABUSE ARE LESS HELPFUL THAN THEY APPEAR

LAURA GRIFFIN[1]* AND GEMMA BRIFFA[1]**

In 2017 Victoria became the first Australian jurisdiction to initiate substantive reforms to its civil liability laws, to address barriers faced by plaintiffs seeking to hold institutions liable for child abuse. The new law, based on recommendations arising from a Victorian inquiry, establishes a statutory duty of care owed by organisations to take reasonable precautions against abuse of children under their care or supervision. On its face, the Wrongs Amendment (Organisational Child Abuse) Act 2017 (Vic) looks like a helpful clarification of this complex area of law. However, when viewed within the context of the work of the Royal Commission on Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, as well as common law principles – particularly strict liability in the areas of non-delegable duty and vicarious liability, and the High Court decision of Prince Alfred College Inc v ADC – we see that barriers and uncertainties remain.

[O]nly a legislative response can resolve the current issues and uncertainties in the current law, and in doing so, provide clarity for plaintiffs and defendants by clearly specifying the circumstances in which an organisation will be liable for abuse perpetrated by people associated with that organisation.[1]

Institutional child abuse, including child sexual abuse, has been the focus of a flurry of public and legal activity in Australia in recent years, including the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (‘Royal Commission’), state-level inquiries and reports, as well as a landmark decision by the High Court of Australia and ongoing legislative reforms across various jurisdictions. This attention is both overdue and well-deserved. The incidence and impact of institutional child abuse in Australia are now well-documented. As summarised by the Royal Commission: ‘It is estimated that over half a million children experienced institutional or other out-of-home “care” in Australia during the 20th century’.[2] A total of 60,000 survivors[3] have been estimated as eligible for a national redress scheme, including almost 16,000 Victorians.[4] Institutional child abuse has serious, long-term impacts on victims, often causing decades of psychological suffering and harm,[5] even extending to intergenerational trauma.

For many survivors, legal recognition of the abuse committed against them is a powerful means of validation and healing.[6] Importantly, civil liability confirms responsibility for these legal wrongs, while providing compensation for the harm caused. For the small number of survivors who do pursue legal avenues for compensation, recourse is often sought against the institution where the abuse occurred. This is not only because the institution is more likely to be a defendant with ‘deep pockets’ (or liability insurance) than the individual perpetrator – many plaintiffs also seek recognition of the role and responsibility of the institution in creating the opportunity for the abuse. However, as recently recognised by the Royal Commission:

[M]any survivors do not consider that justice has been or can be achieved for them through existing civil litigation systems or through previous or existing redress schemes that some governments and non-government institutions offer ... [F]or many survivors, existing civil litigation systems and redress schemes do not provide, and have not in the past provided, effective avenues to seek or obtain justice in the form of compensation or redress that is adequate to address or alleviate the impact on survivors of sexual abuse.[7]

In particular, plaintiffs have faced a range of legal barriers to recovery, such as the application of statutory time limits on commencing legal actions, and difficulty establishing an appropriate defendant, particularly in the case of unincorporated non-government organisations such as religious institutions. The latter barrier is commonly known as the ‘Ellis defence’, in reference to the New South Wales Court of Appeal’s decision in Trustees of the Roman Catholic Church v Ellis (‘Ellis’)[8] – a case of child sexual abuse by a priest, where an appropriate defendant could not be established due to the unincorporated nature of the Roman Catholic Church and the fact that church trustees did not manage the appointment or removal of priests.

With regard to the question of when and how an institution may be held responsible for abuse of a child under its care or supervision, three main avenues have been attempted, each with its own hurdles (see Table 1). As recognised by state-level inquiries and the Royal Commission, courts have traditionally been very reluctant to recognise institutional liability for child abuse, under all three avenues.[9]

In response to the various inquiries and reports, states – proudly led by Victoria[11] – have begun implementing a range of legislative reforms seeking to remove or lower these legal barriers. Some legislative measures have targeted the Ellis defence, setting out processes for identifying appropriate institutional defendants or unincorporated associations, including those using trusts to manage funds or property.[12] Others have removed statutory time limitations from child abuse cases.[13] The most complex reforms, though, have been those addressing the question of duty or civil liability. In addition, alongside these legislative reforms is the landmark decision of Prince Alfred College Inc v ADC (‘Prince Alfred’)[14] in 2016, where the High Court of Australia set out its preferred approach to deciding vicarious liability in cases involving intentional criminal acts by an employee – in this case, sexual abuse of a child in a boarding school. Notably, while civil liability reforms apply prospectively, historical child abuse is also addressed by the new National Redress Scheme for Institutional Child Sexual Abuse, established in response to the Royal Commission’s detailed recommendations.[15]

Scholarly commentary and debate has accompanied these public inquiries and reforms, both in Australia and internationally.[16] Similarly, non-scholarly works have announced or commented on legislative reforms, and the decision in Prince Alfred.[17] However, there has not yet emerged any systematic, critical scrutiny of these reforms and the civil law landscape currently faced by victims. Such scrutiny has the potential to inform ongoing developments, as several Australian jurisdictions are still in the process of exploring reform options. As this article will show, these reforms are best evaluated not merely on their face, but with regard to the surrounding common law principles and developments.

This article focuses on Victoria’s reforms – specifically, the Wrongs Amendment (Organisational Child Abuse) Act 2017 (Vic) (the ‘Amending Act’)[18] which came into force on 1 July 2017. While the bill introducing the Act (the ‘Amending Bill’) was announced in the second reading speech as ‘provid[ing] clarity for both organisations and survivors of abuse’,[19] unfortunately it does not achieve this aim. We critically analyse this specific reform, pointing out its shortcomings, and exploring circumstances under which plaintiffs may still struggle to hold institutions liable in cases of organisational child sexual abuse. We show how the Amending Act is best understood in its particular historical context, and in the context of complex common law principles. This requires us to delve into the murky depths of High Court reasoning regarding vicarious liability and non-delegable duty in cases of this nature – specifically, in Prince Alfred and its predecessor, New South Wales v Lepore (‘Lepore’).[20] We argue that while recent legal reforms are welcome and important, a number of significant hurdles remain as a result of the legislative gaps on the one hand, and complex and unclear common law doctrine on the other hand.[21] In light of this ongoing complexity, and the differing approaches now being taken by other jurisdictions, there are still compelling reasons for further Victorian reforms to impose stricter liability on institutions for abuse of children in their care. This may also assist in shaping better reforms in other jurisdictions.

The article is structured as follows. Part II traces the background to the Amending Act, showing how it was enacted as a response to a Victorian-level inquiry and therefore ignored concurrent developments in both the High Court and the Royal Commission. Part III then examines and critiques the content of the Amending Act, specifically the creation of a statutory duty of care in section 91, and the reversed onus of proof regarding breach by the organisation. Part IV analyses the Amending Act’s connection or similarity to non-delegable duty, in the process considering whether non-delegable duty is best understood as imposing strict liability. The remainder of the article lays out the legal principles applicable in cases involving institutional child abuse, where the Amending Act cannot be relied upon because the institution was demonstrably not at fault – that is, avenues for imposition of strict liability on the institution. Part V considers the High Court’s current preferred (Prince Alfred) approach to vicarious liability in cases of organisational child abuse, before outlining the applicable common law regarding non-delegable duty in such cases. Part VI concludes the article, revisiting the overall argument regarding the need for further reform.

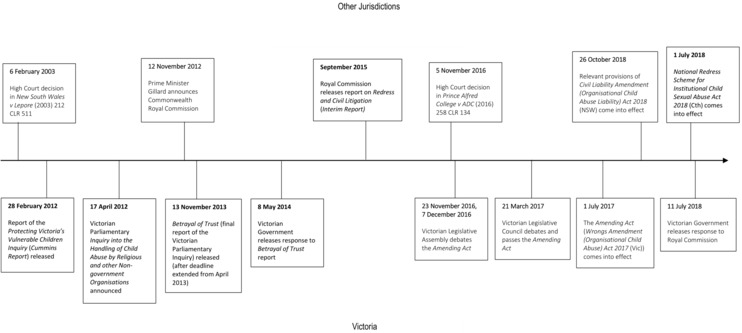

In order to understand the Victorian Amending Act and analyse its shortcomings, it is helpful to place the law in its recent historical context. As we shall see, in this context, the Amending Act is significant as the inaugural state-level effort at civil liability reform. However, as a response primarily to a Victorian inquiry and report, the Amending Act ignored concurrent developments in the High Court and the Royal Commission. This helps to explain its limitations. A brief narrative account, reflected in the timeline in Figure 1, is offered for this purpose. The story is somewhat complex, but invaluable for understanding the analysis in the remainder of this article.

Early in 2011, the Victorian Government announced the Protecting Victoria’s Vulnerable Children Inquiry, tasked with investigating and developing recommendations to reduce the incidence and negative impact of child neglect and abuse in Victoria.[22] Just over one year later, the resulting report was released.[23] This rapidly led to a Victorian parliamentary Inquiry into the Handling of Child Abuse by Religious and other Non-government Organisations, announced on 17 April 2012.[24] The Commonwealth was soon to follow suit, with Prime Minister Gillard announcing a Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Abuse in November the same year.

The final report of the Victorian parliamentary inquiry, entitled Betrayal of Trust: Inquiry into the Handling of Child Abuse by Religious and Other Non-government Organisations (‘Betrayal of Trust’), was released in November 2013 (after an extension was approved).[25] Comprising two volumes and over 700 pages, this report looked comprehensively at many aspects and issues relating to institutional child abuse, from victims’ experiences, to specific organisational processes (such as the Melbourne Response within the Catholic Church),[26] to measures to create child-safe organisations. Part H focused on Civil Justice Reform, with Chapter 26 specifically attending to the ‘Legal Barriers to Claims Against Non-government Organisations’, where the following barriers were identified:

• difficulty finding an entity to sue, because of the legal structures of some non-government organisations [noted above as ‘Ellis defence’]

• application of the statute of limitations to [civil] child abuse cases ...

• inability to establish that organisations have a legal duty to take reasonable care to prevent child abuse by their members

• difficulty identifying a legal relationship between the perpetrator and the entity

• the courts’ exclusion of criminal acts from the notion of vicarious liability.[27]

The first two of these barriers were addressed through dedicated legislative amendments, namely the Limitation of Actions Amendment (Child Abuse) Act 2015 (Vic) which came into effect on 21 April 2015, and the Legal Identity of Defendants (Organisational Child Abuse) Act 2018 (Vic), which came into effect on 1 May 2019.

The remaining three barriers refer to specific principles within common law, where courts have been reluctant to hold organisations liable – as reflected in Table 1, above. In negligence, a duty of care to protect a plaintiff from harm by criminal conduct of another person is often difficult to establish, except where either the plaintiff or the wrongdoer is under the defendant’s care and control.[28] Liability also depends on proving that the defendant breached the duty by failing to take reasonable care,[29] and that the breach caused harm that was not too remote.[30] In tort law more generally, vicarious liability will only be imposed upon an institution where both a) the tortfeasor was an employee of the organisation,[31] and b) the tort was committed in the course of their employment.[32] Betrayal of Trust also briefly discussed non-delegable duty of care, particularly in light of Lepore, [33] where a majority of the High Court held that the non-delegable duty owed by a school to its pupils cannot extend to intentional criminal conduct against a pupil by a teacher.[34] Betrayal of Trust also accurately observed that ‘[t]he case [of Lepore] failed to provide clear guidance on the question of when vicarious liability could be established in these circumstances.’[35]

In exploring potential avenues for reform by considering ‘[e]xisting legislative models for vicarious liability’,[36] Betrayal of Trust then took a curious turn. It drew a model[37] from discrimination legislation – including both the Equal Opportunity Act 2010 (Vic)[38] and the Sex Discrimination Act 1984 (Cth)[39] – where employers or principals are said to have contravened the relevant Acts when their employees or agents do so while acting in the course of employment or while acting as agents. Both of these Acts also provide an exception – the organisation will not be held vicariously liable if it can prove, on the balance of probabilities, that it took reasonable steps or precautions to prevent such conduct. These provisions from discrimination law were titled ‘vicarious liability’ provisions.

Based on this discussion Betrayal of Trust then identified two options for reform:

• legislating [a] non-delegable duty of care in the Wrongs Act. For example, that organisations have a non-delegable duty of care to take reasonable care to prevent intentional injury to children in their care

• a provision regarding vicarious liability in the Wrongs Act based on the examples in the Victorian and Commonwealth discrimination legislation.[40]

After setting out these options, Betrayal of Trust specified Recommendation 26.4: ‘That the Victorian Government undertake a review of the Wrongs Act 1958 (Vic) and identify whether legislative amendment could be made to ensure organisations are held accountable and have a legal duty to take reasonable care to prevent criminal child abuse’.[41] As we shall see below, the subsequent Amending Act followed somewhat of a hybrid approach, in an attempt to address the latter three barriers identified above.

In its May 2014 response to Betrayal of Trust, the Victorian Government expressed support in principle for Recommendation 26.4, stating that it was ‘currently considering options to achieve the objectives of this recommendation’.[42] By late 2016, the Amending Bill was introduced to the Victorian Legislative Assembly. In parliamentary debates, and Attorney-General Pakula’s second reading speech, the Amending Bill was explicitly framed as a response to Betrayal of Trust (specifically Recommendation 26.4) and by extension to ‘the common law [which the report found] has not developed sufficiently in Australia to recognise the liability of organisations for child abuse perpetrated by organisational representatives’.[43]

In fact, in the two months preceding this second reading speech, two important developments had emerged. The first was the High Court’s decision in Prince Alfred, handed down on 5 November 2016. In this decision, the Court acknowledged the confusion generated by its past decision in Lepore, while clearly and unanimously outlining a new approach to determining vicarious liability in cases of organisational child abuse. As we discuss in Part VI below, this decision still left some areas of uncertainty, particularly regarding non-delegable duty. It is significant that the decision did address some of the barriers or difficulties identified in Betrayal of Trust, and yet was effectively ignored while the Amending Bill was being debated.[44]

The second development was the release by the Royal Commission of its interim Redress and Civil Litigation Report.[45] Part IV of this Interim Report focused on civil litigation, covering the same general issues as Betrayal of Trust had, as well as model litigant approaches. Section 15 focused on the ‘duty of institutions’, and considered approaches taken in other jurisdictions, such as the United Kingdom and Canada.[46] A key difference between this report and Betrayal of Trust was the explicit discussion of strict liability – both with regards to vicarious liability, and non-delegable duty. It even articulated and rebutted arguments against the imposition of strict liability in this area,[47] and considered circumstances where courts had been willing to recognise vicarious liability for intentional criminal conduct, comparing these with the case of organisational child abuse.[48]

The Interim Report also considered the discrimination law models proposed in Betrayal of Trust. Ultimately it recommended two kinds of law reform at state level:

• First, legislation should impose a non-delegable duty on certain institutions for institutional child sexual abuse, with a list of recommended institutions that provide care, supervision or control of children (Recommendations 89 and 90);

• Second, (and regardless of whether the first option is undertaken) legislation should impose liability on all organisations for institutional child sexual abuse, with the possibility for an organisation to escape liability by proving that it took reasonable precautions – that is, with a ‘reverse onus’ (Recommendation 91). This echoes what had been recommended in Betrayal of Trust, with its model based on discrimination legislation.[49]

The Interim Report also recommended (in Recommendation 92) that for both options 1 and 2

the persons associated with the institution should include the institution’s officers, office holders, employees, agents, volunteers and contractors. For religious organisations, persons associated with the institution also include religious leaders, officers and personnel of the religious organisation.[50]

By contrast with the later Interim Report, Betrayal of Trust had not paid attention to the significance of imposing strict liability in circumstances of institutional child abuse. Amazingly, the phrase ‘strict liability’ was not used once in the entire two-volume report. Its cursory discussion of non-delegable duty referred to a ‘non-delegable duty of care’ and stated that the imposition of such a duty had been precluded by courts in Lepore.[51] Likewise, in the Betrayal of Trust options for reform (as quoted above), the language of ‘non-delegable duty’ became muddled with language of ‘duty to take reasonable care’,[52] suggesting that the Betrayal of Trust committee did not appreciate or consider the significance of non-delegable duty as potentially imposing strict liability. In considering models of ‘vicarious liability’ from discrimination legislation, which include exceptions where reasonable care is taken by an employer or principal, Betrayal of Trust also strayed from an understanding of vicarious liability as one involving strict liability. The strict liability nature of both vicarious liability and non-delegable duty therefore became lost in Betrayal of Trust.

Yet it was Betrayal of Trust that formed the basis for Victorian law reform. In debating the Amending Bill in late 2016 and early 2017, parliamentarians ignored the recent Interim Report with its clearer view of strict liability and its recommendation for the imposition of a (strict liability) non-delegable duty on institutions. They also ignored the freshly decided case of Prince Alfred, where the High Court had signalled a new potential avenue for the imposition of vicarious liability in cases of institutional child sexual abuse. The Victorian Government even claimed, in its 2018 response to the Royal Commission, that it had ‘already implemented’ the Interim Report’s recommendations on this matter, by introducing ‘legislation to impose a non-delegable duty on certain institutions for institutional child sexual abuse’.[53] The Victorian Government thus appears to retain its confusion about non-delegable duty, vicarious liability and strict or fault-based liability in this area.

With this background in mind, we can better appreciate the irony of an Amending Act specifically aimed at addressing uncertainties created by common law, which is based on a government report (Betrayal of Trust) which displayed confusion regarding liability in this area:

[T]he government agrees with the Family and Community Development Committee [in Betrayal of Trust] that only a legislative response can resolve the current issues and uncertainties in the current law, and in doing so, provide clarity for plaintiffs and defendants by clearly specifying the circumstances in which an organisation will be liable for abuse perpetrated by people associated with that organisation. The bill provides the legislative response that is required.[54]

Of course, this irony is only problematic if the Amending Act itself does not resolve the confusion. As the Fact Sheet on the Amending Act confidently declares, ‘[t]his duty provides clarity for both organisations and survivors of abuse’.[55] Unfortunately, clarity remains elusive. As the rest of this article will demonstrate, the Amending Act appears to address several of the legal barriers identified in Betrayal of Trust and the Interim Report. However, particularly when the Amending Act is viewed in the context of common law principles of non-delegable duty and vicarious liability, we find that Victorian plaintiffs and organisations still face confusion about when an organisation may be held liable for institutional child abuse.

The Amending Act inserts a new Part XIII into the Wrongs Act 1958 (Vic). In this section we examine the key provisions inserted by the Amending Act, with regard to establishment of a statutory duty and the ‘reverse onus’ on organisations regarding breach. We then critique these by examining to what degree they work to establish liability where none would otherwise be arguable by a plaintiff.

Section 91, the heart of the new provisions, creates a direct statutory duty owed by the relevant organisation to the victim:[56]

(1) This section imposes a duty of care that forms part of a cause of action in negligence.

(2) A relevant organisation owes a duty to take the care that in all the circumstances of the case is reasonable to prevent the abuse of a child by an individual associated with the relevant organisation while the child is under the care, supervision or authority of the relevant organisation.

(3) In a proceeding on a claim against a relevant organisation for damages in respect of the abuse of a child under its care, supervision or authority, on proof that abuse has occurred and that the abuse was committed by an individual associated with the relevant organisation, the relevant organisation is presumed to have breached the duty of care referred to in subsection (2) unless the relevant organisation proves on the balance of probabilities that it took reasonable precautions to prevent the abuse in question.

A Note accompanying section 91(3) also provides:[57]

Reasonable precautions will vary depending on factors including but not limited to–

a) The nature of the relevant organisation; and

b) The resources that are reasonably available to the relevant organisation; and

c) The relationship between the relevant organisation and the child; and

d) Whether the relevant organisation has delegated the care, supervision or authority over the child to another organisation; and

e) The role in the organisation of the perpetrator of the abuse.

Section 91(6) also reiterates that the statutory duty in section 91(2) ‘does not apply to abuse of a child committed by an individual associated with a relevant organisation in circumstances wholly unrelated to that individual’s association with the relevant organisation’.[58]

The establishment of a duty of care in section 91 appears to provide progress and certainty for plaintiffs. In particular, it appears to address difficulties faced by plaintiffs under the first of the three avenues of liability (A) displayed in Table 1. A duty of care in negligence can certainly be difficult to establish where the duty involves protection from intentional criminal harm by others. Such a duty has been successfully established in circumstances where the defendant was in a relationship where they exercised ‘care and control’ – either over the third party who committed the criminal conduct,[59] or over the plaintiff.[60] A key factor in judicial decision-making in this area is the factor of control: specifically, the degree of control exercised by the defendant over the wrongdoer.[61] This emphasis on control is consistent with recent High Court reasoning in determining duty of care in novel circumstances more generally.[62]

Absent such a relationship, mere foresight that others may cause harm is not enough to establish a duty.[63] In addition, where the potential class of plaintiffs is effectively indeterminate, a duty will not be recognised.[64] Notably, none of the cases where liability has successfully been established involved child sexual abuse, although several have involved other kinds of criminal assault upon children. The Amending Act captures such instances of physical assault in its broad definition of ‘abuse’ as ‘physical abuse or sexual abuse’.[65]

In these cases, courts have grappled with questions of the extent, nature or scope of the duty of care. For example, a school’s duty of care to protect its pupils from criminal harm by others may only extend so far from the school grounds (ie geographically) or from school hours (temporally).[66] As courts have acknowledged when discussing questions of extent, nature or scope of a duty of care in other contexts,[67] such language effectively blends the reasoning or questions of duty, with those of breach. Likewise, we can view the various (duty and breach) subsections of section 91 as a whole, when assessing how far the Amending Act provides opportunities for establishing liability beyond those already existing under common law principles. Put simply, how much of a difference does the Amending Act make in this area?

The Amending Act defines a ‘relevant organisation’ as ‘an entity (other than the State) organised for some end, purpose or work that exercises care, supervision or authority over children, whether as part of its primary functions or activities or otherwise’.[68] Affiliation with the organisation is also defined broadly in the Amending Act, in section 90(1):[69]

(1) An individual associated with a relevant organisation–

(a) includes but is not limited to an individual who is an officer, office holder, employee, owner, volunteer or contractor of the relevant organisation; and

(b) if the relevant organisation is a religious organisation, includes but is not limited to a minister of religion, a religious leader, an officer or a member of the personnel of the religious organisation ...

In circumstances contemplated by the Amending Act – where the organisation exercises some level of care, authority or supervision over a child, and where an abuser had some affiliation with the defendant organisation – a duty of care to the child to protect them from harm by a person in the abuser’s position may already be arguable. If so, then the legislation makes a duty of care in negligence action easier to establish, rather than creating a duty of care where victims would otherwise be unable to establish one on the basis of existing common law principles. Somewhat confusingly, the Victorian Government has stated that

A stand-alone statutory duty of care has been created to allow an organisation to be held liable in negligence for certain contexts of organisational child abuse. This does not alter other duties under the law of negligence, vicarious liability, or non-delegable duties.[70]

This suggests that the Amending Act is best understood not as intervening in avenue A of liability from Table 1 (a common law action in negligence) but instead as creating an entirely separate avenue of liability.

In a common law action in negligence, questions of the extent or content of a duty of care to protect from harm by a third party would already have required a court to consider the circumstances of the criminal conduct in question, and the level of care or control that the organisation was able to exercise over either the perpetrator, and/or the plaintiff. These aspects are now found in the list of factors to be considered by a court in considering whether the duty was breached by the organisation. Likewise, the exclusion in section 91(6) confirms the reasoning that would already be applied under common law principles: if an individual abused a child in circumstances wholly unrelated to their association with an organisation, then the scope of the organisation’s duty would not likely be held to extend to such conduct. As summarised by Attorney-General Pakula in the second reading speech for the Amending Act:

The nature of the care, supervision or authority exercised by an organisation will also inform a court’s determination of the ‘reasonable precautions’ an organisation is required to take. The more distant an alleged perpetrator’s association with an organisation and with that organisation’s care, supervision or authority over children, the lower the burden may be for the organisation to prove reasonable precautions were taken if the child abuse occurs.[71]

This seems to confirm the reasoning that would be applied by courts under existing negligence principles – either in relation to the scope or nature of a duty of care, or the assessment of breach according to the ordinary ‘calculus of negligence’ principles under section 48 of the Wrongs Act 1958 (Vic).

In contrast, the new section 91(3) inserted by the Amending Act definitely makes a significant shift away from the existing common law principles of negligence, by creating a presumption of breach by the organisation. Ordinarily, breach of duty would need to be proven by a plaintiff, on the balance of probabilities, and according to the general principles set out in section 48 of the Wrongs Act 1958 (Vic). This provision of the Amending Act conforms to the model of so-called ‘vicarious liability’ in discrimination law as set out in Betrayal of Trust[72] and referred to as a ‘reverse onus’ in the Royal Commission’s Interim Report.[73] An organisation is therefore able to avoid liability if it can prove on the balance of probabilities that it took ‘reasonable precautions’ to prevent the abuse.[74]

In his second reading speech for the Amending Bill, Attorney-General Pakula stated that:

‘Reasonable precautions’ has intentionally been left undefined to allow courts to flexibly respond to the circumstances of each case. As the liability that can be imposed by the bill is one in negligence, it is expected that courts will draw on the vast wealth of case law concerning negligence to determine what is and is not ‘reasonable’.[75]

As he noted, courts would also likely be guided by ‘the government’s recently released Child Safe Standards, which are compulsory minimum standards that apply to organisations that provide services for children, and were also released in response to Betrayal of Trust.’[76]

As the Amending Act applies prospectively – that is, it applies only to abuse that occurs after the new provisions came into force[77] – judicial determination of ‘reasonable precautions’ is indeed likely to be heavily informed by the kinds of measures required of institutions under the suite of ‘child safe institutions’ reforms arising from Betrayal of Trust and the Royal Commission.[78] The Amending Act therefore effectively functions in a regulatory sense as a kind of enforcement mechanism for the new mandated precautions expected of organisations to prevent abuse of children under their care or supervision. However, the burden remains on individual victims, who have been abused following institutional failures to take reasonable precautions, to bring their claims to court to have these failures and their harmful consequences recognised.[79]

It is undoubtedly a benefit to plaintiffs to have the onus of proof regarding breach reversed. In the recent cases involving institutional child abuse, and within arguments relying on negligence (that is, in avenue A from Table 1), breach has indeed been a sticking point. For example, in the first instance (District Court) judgment of New South Wales v Lepore, Judge Downs QC found that breach by the school had not been made out.[80] There was no challenge to this finding in the subsequent appeals (which focused on non-delegable duty and vicarious liability instead).[81] Similarly, in the first instance decision of A, DC v Prince Alfred College, Vanstone J found that there was no breach by the school.[82] On appeal to the South Australian Full Court in A, DC v Prince Alfred College, two out of three judges again found that there had been no breach by the defendant school.[83] The question was not then raised on appeal to the High Court.[84] In the case of Erlich v Leifer, which involved sexual abuse of a pupil by a school principal, breach was also not made out.[85]

However, even with a reversed onus, many plaintiffs are still likely to experience problems when relying on a negligence action. In terms of logistics and evidentiary burdens, the defendant organisation will almost always be better equipped than the plaintiff in terms of having the resources and other means to gather the requisite evidence relating to precautions taken. Also, of course, the civil standard of care remains unchanged (the balance of probabilities). The remaining element – causation – may also prove problematic. To establish liability, plaintiffs are still required to prove both a) that the organisation’s failure to take reasonable precautions was a necessary precondition of the abuse; and b) that it would be appropriate for the scope of the organisation’s liability to extend to that abuse.[86] In some cases where courts have been willing to recognise a duty to protect from harm by others, causation has nevertheless been difficult to prove, because the plaintiff could not prove, on the balance of probabilities, that further precautions would have prevented the intentional criminal conduct that took place.[87]

Of course, as intended by the Amending Act, if an organisation can show that it did take reasonable precautions, then no liability arises. This is why alternative avenues of liability (avenues B and C in Table 1) have been significant to plaintiffs in cases involving institutional child abuse – and why they are likely to remain so. The remainder of this article therefore traces the remaining legal landscape faced by potential plaintiffs in cases of institutional child abuse in Victoria. As we will demonstrate, if an organisation can demonstrate that it took reasonable precautions, this does not simply mean that there is no way it can be held liable for physical or sexual abuse of a child under its care. For this reason, the Amending Act – whose purpose is ‘to clarify when an organisation can be held liable for child abuse perpetrated by its personnel’[88] – fails to achieve this aim.

Before charting the legal landscape of avenues B and C from Table 1, it is necessary to address a point of contention or confusion around non-delegable duty. This is partly because the Amending Act has been interpreted by some as creating or imposing a non-delegable duty, and partly because – as traced in Part II above – the Betrayal of Trust report which led to the Amending Act displayed some confusion regarding non-delegable duties. Specifically, it is necessary to clarify whether non-delegable duties can, and should, be understood as imposing strict liability.

In its 2018 formal response to the Royal Commission, the Victorian Government claimed to have ‘already implemented in Victoria’ several recommendations from the Interim Report, including ‘the introduction of legislation to impose a non-delegable duty on certain institutions for institutional child sexual abuse’.[89] Yet, as we saw in Part II above, the Royal Commission in fact had two separate recommendations – first, for the creation of a non-delegable duty imposing strict liability on certain institutions but exempting others, and second, for the Victorian-style ‘reverse onus’ imposition of liability where reasonable precautions were not taken by the organisation. How then could the Victorian Government mistakenly claim that it had in fact followed the Royal Commission’s first option, and created a non-delegable duty?[90]

The Amending Act provides a very broad test for determining an individual’s association with a relevant organisation:[91]

90 When is an individual associated with a relevant organisation?

(1) An individual associated with a relevant organisation–

(a) includes but is not limited to an individual who is an officer, office holder, employee, owner, volunteer or contractor of the relevant organisation; and

(b) if the relevant organisation is a religious organisation, includes but is not limited to a minister of religion, a religious leader, an officer or a member of the personnel of the religious organisation; and

(c) if the relevant organisation has delegated, by means of contract or otherwise, the care, supervision or authority over the child to whom the claim relates to any organisation, includes but is not limited to an individual who is referred to in paragraph (a) or (b) in relation to the delegator organisation or the delegate organisation; and

(d) if the relevant organisation has delegated, by means of contract or otherwise, the care, supervision or authority over the child to whom the claim relates to a specified carer and a permanent care order in respect of the child has not been made, includes but is not limited to–

(i) an individual who is referred to in paragraph (a) or (b) in relation to the relevant organisation; and

(ii) the specified carer.

(2) An individual is not associated with a relevant organisation solely because the relevant organisation wholly or partly funds or regulates another organisation.

There are thus several reasons why the Amending Act could have been interpreted as imposing a non-delegable duty. First, section 90 expressly addresses situations where the care of a child has been delegated, and confirms that the statutory duty applies to all relevant organisations, and a broad range of individuals within those organisations. Second, the express inclusion of contractors alongside employees in section 90(1)(a) is also reminiscent of non-delegable duty. This is because non-delegable duty is typically raised (and thus considered judicially) as an extension of vicarious liability – more specifically as an exception to the ‘first limb’ of vicarious liability, namely the requirement in vicarious liability that the tortfeasor was an employee of the institution rather than a mere contractor. Third, one of the most well-known and common relationships where a non-delegable duty has traditionally been recognised is a school’s non-delegable duty to its pupils. Indeed, courts have confirmed that non-delegable duty is the appropriate duty to be argued – as opposed to a general duty of care in negligence – in circumstances involving schools and pupils.[92] Of course, schools are one of the most common organisational contexts within which child abuse occurs.[93]

It is understandable, then, that the Amending Act could be interpreted as imposing a non-delegable duty, or extending non-delegable duty beyond a traditionally recognised category (school to pupils) to a much broader category of children in institutional contexts. Nevertheless, this would be a misinterpretation, and one based on a misunderstanding of the law of non-delegable duty.

Non-delegable duty is an especially complex and unclear area of tort law. Nonetheless, attempts have been made, by judges and scholars alike, to provide some clarity in this area. In this regard, it is worth quoting at length the discussion provided in the 2002 Review of the Law of Negligence (commonly known as the ‘Ipp Report’):

Although the precise nature of a non-delegable duty is a matter of controversy and uncertainty, one thing is clear: a non-delegable duty is not a duty to take reasonable care. ...

A second thing that is clear about non-delegable duties is that although they are a technique for imposing vicarious liability – that is, strict liability for the negligence of another – they are typically not thought of as a form of strict liability. It is often said, for instance, that although a non-delegable duty is not a duty of care, it is a duty ‘to see that care is taken’. The implication of this statement is that there are steps (typically not specified) that can be taken to discharge a non-delegable duty. By contrast, there is nothing that an employer can do to prevent being subject to vicarious liability for the negligence of its employees. This is because it is a form of liability that attaches automatically to the relationship of employer and employee, and not to anything done by the employer in the course of that relationship. The only way of avoiding vicarious liability is not to be an employer.

The problem that this situation creates is that courts often give the impression, when they impose a non-delegable duty, that they are not imposing a form of strict liability but rather a form of liability for breach of a duty committed by the employer in the course of being an employer. In other words, although it is clear that a non-delegable duty is not a duty of care, courts often seem to think that a non-delegable duty can only be breached by conduct on the part of the employer that is in some sense faulty. As a result, courts do not think that they need to justify the imposition of a non-delegable duty in terms of the justifications for the imposition of strict vicarious liability. Rather, they appear to think that justification is to be found in arguments for imposing liability for ‘fault’ (in some sense).

Thirdly, it is important to understand that a non-delegable duty is a duty imposed on the employer alone. The worker is not, and cannot be, under the duty. The worker’s duty is an ordinary duty to take reasonable care. And even though liability for breach of a non-delegable duty is functionally equivalent to vicarious liability, it is (unlike vicarious liability) liability for breach of a duty resting on the employer. In other words, whereas vicarious liability is secondary or derivative liability (in the sense that it is based on the liability of the negligent worker), liability for breach of a non-delegable duty is, in theory at least, a primary, non-derivative liability of the employer.[94]

It was precisely in response to this confusion, and in order to remedy it, that the Ipp Report recommended a legislative enactment clarifying that liability for non-delegable duty should be imposed strictly and equivalently to vicarious liability. As a result, Victoria enacted exactly such a provision in section 61 of the Wrongs Act 1958 (Vic), which also confirmed that liability for non-delegable duty could extend beyond circumstances where negligence is the tortious conduct involved:

61. Liability based on non-delegable duty

(1) The extent of liability in tort of a person (the defendant) for breach of non-delegable duty to ensure that reasonable care is taken by a person in the carrying out of any work or task delegated or otherwise entrusted to the person by the defendant is to be determined as if the defendant were vicariously liable for the negligence of the person in connection with the performance of the work or task.

(2) This section applies to a claim for damages in tort whether or not it is a claim for damages resulting from negligence ... Despite these clarifications, and ongoing scholarship confirming that non-delegable duty is best understood as imposing strict liability,[95] Betrayal of Trust referred explicitly to ‘non-delegable duty of care’, and listed ‘the duty of care owed by an education authority to its students’ as a recognised category of non-delegable duty.[96] Such language reveals a poor understanding of the law of non-delegable duty, and in the process muddles avenues A (duty of care in negligence) and C (non-delegable duty) for liability. The Royal Commission, in its Interim Report, did not repeat these slippages in its brief discussion of non-delegable duty.[97] It also explicitly reproduced judicial statements that non-delegable duty imposes strict liability upon the defendant.[98]

Hence the non-delegable duty proposed by the Interim Report was intended as an option for imposing strict liability upon institutions for abuse of children under their care. It was for this reason that the Royal Commission recommended that such a new statutory non-delegable duty would extend only to certain kinds of institutions and not others:

Where a person associated with an institution fails to take reasonable care of a child in the care and control of that institution, by that person committing a criminal act against the child a strict liability regime will impose liability on the institution for that failure.

To our minds it would be reasonable to impose liability on any residential facility for children, any school or day care facility, any religious organisation or any other facility that is operated for profit that provides services for children and that involves the facility having the care, supervision or control of children for a period of time. We do not believe that liability should be extended to not-for-profit or volunteer institutions generally – that is, beyond the specific categories of institutions identified.[99]

In contrast, in the Amending Act the Victorian Government created a statutory duty whereby an institution can avoid liability by proving that it took reasonable precautions. That is not the imposition of strict liability, and should not be characterised as a non-delegable duty.

With this confusion cleared, our remaining task in this article is to map the avenues of liability remaining for potential plaintiffs in this area. That is, if institutional liability is not possible under avenue A (a common law action in negligence) or under the new statutory duty, because the institution can prove that it took reasonable precautions and was not at fault, can the institution still be liable?

A victim of institutional child abuse, seeking to hold the institution liable, has two legal avenues when seeking an imposition of strict liability – vicarious liability, and non-delegable duty (corresponding to avenues B and C in Table 1). As we show in this section, while important developments have been made in these areas, unfortunately for both plaintiffs and institutions, many uncertainties and areas of confusion remain.

As mentioned earlier, for a defendant to be held vicariously liable for the tortious conduct of another person, two conditions (known as ‘limbs’) must usually be satisfied: first, the tortfeasor must have been an employee/agent of the defendant employer/principal,[100] and second, the tortfeasor must have committed the tortious conduct in the ‘course of employment’ rather than during a ‘frolic of their own’.[101] In particular because of this second limb, courts in Australia and other common law jurisdictions have traditionally been reluctant to recognise vicarious liability for intentional criminal conduct.[102] As we shall see from the relevant case law, this includes child abuse.

As mentioned above, while the Victorian Amending Bill was being debated in Parliament in late 2016, the High Court had just delivered a landmark judgment: Prince Alfred. This case involved child abuse by a housemaster employed at a boarding school. The case was ultimately decided on a different legal question – namely whether an extension of time under the relevant statute of limitations should be allowed – which the court answered in the negative, for reasons beyond the scope of our discussion here. However, the High Court took this opportunity to outline the suitable approach for determining vicarious liability in cases of institutional child abuse. In doing so, the Court was not only seeking to clarify an area of law which had previously been left in a messy and uncertain state – namely, in the Lepore decision of 2003[103] – but was also attempting to bring Australia more in step with developments in other common law jurisdictions.

In Prince Alfred, then, the High Court – specifically a majority consisting of French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Keane and Nettle JJ – confirmed that in cases of institutional child abuse, the fact that the tortious act is intentional criminal conduct does not preclude it from attracting vicarious liability. Looking at case law in Australia as well as Canada and the United Kingdom, the Court contrasted circumstances where the criminal conduct was carried out in ostensible performance of the tortfeasor’s employment (where vicarious liability may apply, as in Lloyd v Grace, Smith & Co), and circumstances where the employment merely provided an opportunity for the criminal conduct which was otherwise unconnected to it (where vicarious liability may not apply, as in Deatons Pty Ltd v Flew).[104] Between these two extremes, there may be cases where

the role given to the employee and the nature of the employee’s responsibilities may justify the conclusion that the employment not only provided an opportunity but was also the occasion for the commission of the wrongful act. By way of example, it may be sufficient to hold an employer vicariously liable for a criminal act committed by an employee where, in the commission of that act, the employee used or took advantage of the position in which the employment placed the employee vis-à-vis the victim.

Consequently, in cases of this kind, the relevant approach is to consider any special role that the employer has assigned to the employee and the position in which the employee is thereby placed vis-à-vis the victim. In determining whether the apparent performance of such a role may be said to give the ‘occasion’ for the wrongful act, particular features may be taken into account. They include authority, power, trust, control and the ability to achieve intimacy with the victim. The latter feature may be especially important. Where, in such circumstances, the employee takes advantage of his or her position with respect to the victim, that may suffice to determine that the wrongful act should be regarded as committed in the course or scope of employment and as such render the employer vicariously liable.[105]

The two dissenting judges, Gageler and Gordon JJ, also explicitly conceded: ‘We accept that the approach described in the other reasons as the “relevant approach” will now be applied in Australia’,[106] suggesting that despite technically being obiter dictum, the passage above does represent a new consensus for the courts. This clear articulation of the applicable legal principles has been welcomed.[107] It has also brought Australian courts more in line with concurrent developments abroad.[108]

However, there still remains the question of the first limb of vicarious liability – the requirement that the tortfeasor was an employee of the institution. This limb was not discussed anywhere in Prince Alfred, nor in Lepore: it was not a live legal issue, as both cases involved employees of the respective institutions. The language used in the passage from Prince Alfred quoted above reflects the assumption that the ‘relevant approach’ applies in circumstances where the first limb has already been met, as the formulation refers to an ‘employee’ and ‘employer’.

And yet, given that the new Prince Alfred test involves interrogating the particular circumstances of control, authority, etc, it is arguable that contractors would often (and justifiably) fail this test anyway, and vicarious liability would not be imposed. This new approach could therefore be applied as a wholesale approach to vicarious liability in cases of institutional child abuse, doing away with the need for any first limb to be satisfied as a separate requirement. But the High Court did not address, or even appear to contemplate, such a possibility in this case.

As a result, there still remains a degree of uncertainty within the area of vicarious liability – specifically, whether it is necessary for a plaintiff to prove that their abuser was an employee of the institution rather than a mere contractor, when seeking to hold the institution vicariously liable for their abuse. In circumstances where a contractor was placed in a position involving ‘authority, power, trust, control and the ability to achieve intimacy with the victim’,[109] could the institution be held vicariously liable? This is an incredibly important question for victims of clerical child abuse given that ministers of religion occupy an ambiguous status in law, as possible employees of religious institutions. No Australian case involving clerical child abuse has yet tested this point.[110]

As this section has shown, the new test laid down by the High Court in Prince Alfred provides a useful guide for deciding vicarious liability in cases of organisational child abuse. But an important area of uncertainty remains – specifically, whether the first limb remains a separate test to be satisfied, in order for an institution to be held vicariously liable. If it does, then victims abused by contractors rather than employees face further difficulties. However, they still have one possible fall-back line of argument: non-delegable duty (avenue C in Table 1).

As we saw in Part IV above, non-delegable duty has often functioned as an exception to the first limb of vicarious liability, albeit one confined to specific recognised relationships such as school and pupil, employer and employee, or hospital and patient. As we also saw, this area of law is complex and often causes confusion, including for judges. When we focus on the law of non-delegable duty in cases involving intentional criminal conduct – including cases involving institutional child abuse – this confusion continues.

Although Prince Alfred superseded Lepore as the leading authority on vicarious liability in cases of sexual abuse of children in educational institutions, it did not address non-delegable duty in any detail. At first instance, Vanstone J ‘held, by reference to New South Wales v Lepore, that the non-delegable duty of care which the [defendant] owed to the [plaintiff] did not extend to a duty to protect him against the intentional criminal conduct of Bain, in the absence of fault of its own’.[111] The appeal was then apparently mis-argued on this issue:

So far as concerns the [defendant’s] non-delegable duty of care owed to the respondent, the respondent contends that New South Wales v Lepore was wrongly decided. However, submissions for the respondent do not address the matters required to invoke the authority of this Court to reconsider a previous decision. They are addressed to arguments which were rejected by the majority in Lepore.[112]

This means that the leading authority on the issue of non-delegable duty in cases of institutional child abuse is still Lepore.[113]

As already mentioned, Lepore involved pupils bringing actions against schools. The case therefore fell squarely within a recognised category or relationship of non-delegable duty. That category was explained by the High Court in Commonwealth v Introvigne (‘Introvigne’) as follows:

The liability of a school authority in negligence for injury suffered by a pupil attending the school is not a purely vicarious liability. A school authority owes to its pupil a duty to ensure that reasonable care is taken of them whilst they are on the school premises during hours when the school is open for attendance.[114]

However, Introvigne had involved negligence causing personal injury – specifically, negligence which resulted in an unsafe school environment, leading to a student being accidentally injured. Thus, despite the quite broad wording of the non-delegable duty as expressed in Introvigne, the Court in Lepore questioned the applicability and extent of such a non-delegable duty in circumstances of intentional criminal conduct:

It is not and, at no stage of these proceedings, has it been in issue that the duties owed by education authorities to their pupils are non-delegable. As already indicated, so much was established by the decision of this Court in Introvigne. What is in issue is the nature of a duty of that kind.[115]

This is broadly consistent with reasoning applied by courts in avenue A (negligence). As we have already seen above, the High Court has followed a similar trend in cases based on an action in negligence: where harm was caused by intentional criminal conduct by a third party, the scope, nature or extent of the defendant’s duty of care may be in question. Lepore then extended this reasoning to avenue C (non-delegable duty). The desire to set limits on this non-delegable duty (as well as a slippage between a non-delegable duty and duty of care) can be observed in the concerns of Gleeson CJ:

The proposition that, because a school authority’s duty of care to a pupil is non-delegable, the authority is liable for any injury, accidental or intentional, inflicted at school upon a pupil by a teacher, is too broad, and the responsibility with which it fixes school authorities is too demanding.[116]

Using similarly problematic wording, Gaudron J also acknowledged the same need for a limit, even while acknowledging that a non-delegable duty imposes strict liability: ‘To say that, where there is a non-delegable duty of care, there is, in effect, a strict liability is not to say that liability is established simply by proof of injury’.[117]

The judicial reasoning in Lepore is significant for the purposes of our analysis. To begin, we can observe that despite following slightly different pathways or reasoning, four out of seven judges in Lepore stated that a school’s non-delegable duty to its pupils does not extend to a duty of protection from intentional criminal conduct.[118] In this sense Lepore symbolises a ‘dead end’ of sorts: despite non-delegable duty typically functioning as an exception to the first limb of vicarious liability, for victims of intentional criminal harm – even those falling within a recognised non-delegable duty relationship like school to pupil – this exception is of no help.

However, there are factors which complicate this view. The first is that the reasoning followed by some judges in Lepore on the issue of non-delegable duty and its limits may be revisited in future. There are occasional inconsistencies in some of the reasoning followed (such as the slippage between non-delegable duty and duty of care), or tensions between the judgments.[119] There are also tensions between the limited view of non-delegable duty in some judgments from Lepore, and other cases in this area. For instance in his dissenting judgement McHugh J observed that a school’s non-delegable duty ‘extends to protecting the pupil from the conduct of other pupils or strangers and from the pupil’s own conduct.’[120] This is consistent with the cases mentioned in Part III regarding the scope of a duty of care in negligence (avenue A of liability).[121] But read alongside the view that a school’s non-delegable duty includes a duty to ensure that care is taken, including by teachers, we reach an absurd outcome: that a school owes a non-delegable duty to pupils, to ensure that teachers exercise reasonable care and do not cause harm to them through negligent conduct (through avenue C), and a school’s duty of care in negligence extends to protecting pupils from intentional criminal harm by other pupils (avenue A) but not by teachers.[122]

The second complicating factor is the limited interpretation of non-delegable duty by some judges in Lepore, that liability based on such a duty can only arise out of a failure to take reasonable care – that is, out of negligent conduct by someone, whether the school or its employees or contractors:

[T]o describe the duty of a school authority as non-delegable is not to identify a duty that extends beyond taking reasonable care to avoid a foreseeable risk of injury. It is simply to say that, if reasonable care is not taken to avoid a foreseeable risk of injury, the school authority is liable notwithstanding that it engaged a ‘qualified and ostensibly competent’ person to carry out some or all of its functions and duties.[123]

This view of non-delegable duty effectively reduces it to a narrow exception to the first limb of vicarious liability, and only where vicarious liability arises from carelessness (negligence by, say, a contractor).[124] But of course since Prince Alfred, we now know that vicarious liability can arise even for intentional criminal conduct, depending on the circumstances of the case. What might this mean for possible re-interpretations of non-delegable duty in the future? We are yet to see.[125]

To understand the final problem with Lepore’s reduction of non-delegable duty to applying only in circumstances of carelessness (negligence by someone, whether an employee or a contractor) we must revisit the Ipp Report’s recommendation (in Part IV above) regarding non-delegable duty, and the resulting legislative provision in Victoria. Specifically, recall section 61(2) of the Wrongs Act 1958 (Vic) which provides that section 61 (‘Liability based on non-delegable duty’) ‘applies to a claim for damages in tort whether or not it is a claim for damages resulting from negligence’. Thus, Victoria has legislation specifically contemplating that liability in non-delegable duty may arise in circumstances other than negligent conduct.[126] No such provision exists in the Civil Liability Act 2003 (Qld) in Queensland, where Prince Alfred arose, and the equivalent provision in New South Wales legislation[127] did not exist when the case of Lepore arose.

Thus, despite it still being true that no victim of institutional child abuse has successfully relied on an argument of non-delegable duty (avenue C), a question mark effectively still remains over whether such plaintiffs – and Victorian ones in particular – may in future have a chance of encouraging courts to revisit the non-delegable duty ‘dead end’ of Lepore. Of course, even in the most optimistic of scenarios, this avenue is still only open to those victims who were abused in institutional contexts where a non-delegable duty relationship is already recognised – such as a hospital to its patients, an employer to its employee, or a school to its pupils.

This article has proceeded as follows. Part II narrated the recent historical context of Victoria’s Wrongs Amendment (Organisational Child Abuse) Act 2017 – referred to throughout the article as the Amending Act. We saw how this reform was enacted as a direct response to Betrayal of Trust, and that during its debating and enactment, the Victorian parliament effectively ignored concurrent developments in both the High Court and the Royal Commission, specifically the latter’s Interim Report. In order to demonstrate what was mistaken or problematic about the Amending Act, we have analysed it in the context of the various potential avenues of establishing liability for institutional child abuse – as set out in Table 1 in our Introduction. Part III examined in detail the Amending Act’s creation of a statutory duty of care, and the presumption (with its ‘reverse onus’ of proof) of breach by the organisation. In Part IV we compared the new statutory duty with the general law of non-delegable duty, demonstrating why references to the Amending Act as creating or extending a non-delegable duty were understandable but misguided, due to their misunderstanding or ignoring the strict nature of liability under common law non-delegable duty. Part V of the article then traced remaining avenues, based on an imposition of strict liability. This included first, the current position regarding imposition of vicarious liability, based on the new ‘relevant approach’ set out by the High Court in Prince Alfred; and second, the complex situation regarding non-delegable duty and intentional criminal conduct, based on the diverse judgments from Lepore and questions about their applicability in present day Victoria.

Mapping the common law context of the Amending Act has thus enabled us to outline the various potential avenues of liability for survivors of organisational child abuse seeking to hold those institutions liable for their abuse. These avenues, and the main hurdles of each, can now be summarised thus (with a new avenue labelled ‘S’ for statutory duty of care):

S. Negligence action based on statutory duty of care as set out in the newly inserted Part XIII of the Wrongs Act 1958 (Vic). This avenue applies to abuse by a broad range of individuals affiliated with the organisation, and presumes a breach by the organisation. The organisation can avoid liability if it can prove (under the ‘reverse onus’) that it took ‘reasonable precautions’ to prevent the abuse.

A. Common law action in negligence, which would rely on arguing that the institution’s duty of care, in its nature/scope/extent, covered protection from intentional criminal conduct by others. Parallel precedents may exist, depending on the specific facts, but none have yet involved organisational child abuse. The plaintiff must also prove that the organisation breached the duty of care by failing to take reasonable care, and that this breach caused harm that was not too remote.

B. Vicarious liability (for battery), applying the new test from Prince Alfred. The plaintiff needs to establish that the employee abuser was placed in such a position vis-à-vis them that the employment provided the occasion for the abuse, and was taken advantage of by the abuser. (This depends on factors like authority, power, trust, control and the ability to achieve intimacy with the victim, so will depend on all the circumstances of the case.) It is not clear from Prince Alfred, but this test may only apply to employees. So, the first limb requirement for employee status may still need to be satisfied, with the result that victims abused by a contractor may be excluded.

C. Non-delegable duty, the least accessible avenue of all. This avenue was not addressed in Prince Alfred, so the leading authority is Lepore, where a majority of the court indicated that the non-delegable duty owed by a school to its pupils should not extend to protection from intentional criminal harm by a teacher. The reasoning in this case may merit revisiting, particularly in light of Prince Alfred, and its applicability to Victoria is somewhat uncertain. Non-delegable duty typically functions as an exception to the first limb of vicarious liability, as a way to attribute liability to an institution, for acts of contractors. Nonetheless, if this avenue could be argued, it would still only be open to those plaintiffs abused in circumstances of a recognised category of non-delegable duty, for instance as a pupil in a school or a patient in a hospital.[128]

Overall, then, we can see that some plaintiffs will still potentially fall between the cracks of the various avenues of liability. The classic example of this would be clerical child abuse where the religious institution can prove that it took reasonable precautions: if the plaintiff cannot establish that their clergy abuser was an employee[129] (or convince the court that the Prince Alfred test disposed of the necessity to pass the ‘first limb’), then they will not be able to rely on the fall-back argument of non-delegable duty as for instance a pupil in a school may attempt to do. Why this inequality between victims, especially if both situations involved similar degrees of authority, control, and intimacy in the abuser’s position?[130] Statistics from the Royal Commission demonstrate an alarming incidence of clerical child abuse or other kinds of child abuse that occurred outside school settings.[131]

We know that the Child Safe Standards, important as they are, will not successfully prevent institutional child abuse in absolutely all cases (that is, even where institutions have taken reasonable precautions against such abuse). It is problematic to say the least, that survivors in such circumstances – that is, stepping outside the fault-based avenues of liability (S and A) should face uncertain, and possibly different, legal hurdles and complexities based on distinctions like employee/contractor or whether the abuse took place within a school context.

Likewise, the newly established National Redress Scheme for Institutional Child Sexual Abuse provides a valuable mechanism for survivors of historical child abuse to access compensation. But certain categories of victim are excluded, while those with ‘serious criminal convictions’ face ‘special assessment’ hurdles in attempting to claim redress.[132] In addition, since the National Redress Scheme applies only to victims of historical child abuse (where the abuse occurred before 1 July 2018),[133] and the Amending Act applies prospectively from 1 July 2017, any such victim of historical child abuse cannot pursue litigation under avenue S above. Potential plaintiffs who effectively ‘fall through the cracks’ of the National Redress Scheme and the Amending Act, face the ongoing complexity of the remaining avenues of liability (avenues A, B and C).

We have already seen that the Victorian Government (in its factsheet)[134] and the Attorney-General (in his second reading speech)[135] have claimed that the Amending Bill provides clarity to both plaintiffs and organisations. In particular, the parliamentary discussions made much of the ‘appropriate balance’ struck by the ‘reverse onus’ – accompanied by statements that if an organisation can show it took reasonable precautions, it will not be held liable.[136] But this is not true, because actions based on the statutory duty, or on negligence, are not the only possible avenues for liability to attach to the organisation. By casually importing a model of ‘vicarious liability’ with its ‘reasonable precautions’ exception from discrimination law, Betrayal of Trust ignored the complexities and rationales of tort law with its avenues of fault-based or strict liability. In following the model proposed in Betrayal of Trust, the Amending Act appeared to be addressing the difficulties in this area of law – such as liability for contractors as well as employees, or the difficulties of proving breach – but it did so without considering how each hurdle arises within its particular common law setting. As a result, the Amending Act failed to provide the clarity claimed by government officials.

Of course, Victoria’s approach was subsequently picked up by the Royal Commission and listed in the Interim Report as a recommendation to states, explicitly encouraged regardless of whether states also adopted the separate recommendation to enact a statutory (strict liability) non-delegable duty owed by a range of institutions responsible for the care or supervision of children. (As we saw, Victoria then reported that it had already acted upon the Interim Report’s recommendations by enacting a non-delegable duty, misunderstanding the strict liability nature of non-delegable duty both at common law and in the Interim Report.) In its eagerness to lead legislative reform in this area, then, has Victoria’s error indirectly led other jurisdictions astray?

New South Wales offers an interesting contrast here. Its Civil Liability Amendment (Organisational Child Abuse Liability) Act 2018 (NSW) (most of the provisions of which came into force on 26 October 2018) provides two main mechanisms for survivors of institutional child abuse seeking to hold the institution liable: first, a statutory duty of care and presumption of breach, similar to Victoria’s model though with an expanded list of factors to be considered in determining whether the organisation took reasonable precautions;[137] and second, a new approach to vicarious liability, which replicates the test from Prince Alfred but explicitly extends this both to employees and those ‘akin to’ employees. Section 6G specifies: ‘An individual is akin to an employee of an organisation if the individual carries out activities as an integral part of the activities carried on by the organisation and does so for the benefit of the organisation’.[138] The New South Wales legislation therefore clarifies avenues of both fault-based liability (with a reverse onus, to the benefit of plaintiffs) and strict liability (extending Prince Alfred to circumstances where a departure from the first limb is justified based on the abuser’s role within the institution). Of course, this is only one possible way forward – other approaches are possible, whether based on the Royal Commission’s recommended strict liability non-delegable duty, or approaches based on other jurisdictions.[139]

While offering a detailed argument of the need for further reforms in light of the Amending Act and its place alongside common law principles, we have not advocated any specific articulation that such reform might take. There are examples from other common law jurisdictions, which Australian courts or legislatures might proceed to follow, and there is a wide range of policy factors or other rationales which could guide such decisions. Our task has simply been to demonstrate how Victoria’s Amending Act is less helpful than it first appears. The fact remains that Victorian survivors of institutional child abuse and institutions alike are still awaiting clarity in this area.

* Dr Laura Griffin is a Lecturer at La Trobe Law School. She lives and works on Wurundjeri land.

** LLB (Hons), BPsych & GDLP. Gemma is employed as a Legal Officer in a federal&#[1]government agency. The authors are grateful to the four anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback.

[1] Victoria, Parliamentary Debates, Legislative Assembly, 23 November 2016, 4537 (Martin Pakula, Attorney-General) (‘Second Reading Speech’).

[2] Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (Final Report: Preface and Executive Summary, 2017) 39 (‘Royal Commission Preface and Executive Summary’). Prior to the Royal Commission, research from the early 2000s confirmed the alarming prevalence of child sexual abuse in Australian schools: see Michael P Dunne et al, ‘Is Child Sexual Abuse Declining? Evidence from a Population-Based Survey of Men and Women in Australia’ (2003) 27(2) Child Abuse and Neglect 141.

[3] We recognise the importance of language when referring to people who have experienced child abuse as either ‘victims’ or ‘survivors’. With regard to the sources used in this article, a Victorian inquiry report uses ‘victim’, while the Royal Commission uses ‘survivor’. ‘Victim’ is also the term used by the High Court of Australia. For this reason, we use the terms ‘victim’ and ‘survivor’ interchangeably, alongside ‘plaintiff’ or ‘potential plaintiff’.

[4] Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (Redress and Civil Litigation Report, September 2015) 29 (‘Interim Report’).

[5] See, eg, Paul E Mullen et al, ‘The Long-Term Impact of the Physical, Emotional, and Sexual Abuse of Children: A Community Study’ (1996) 20(1) Child Abuse and Neglect 7, 21; Joseph H Beitchman et al, ‘A Review of the Long-Term Effects of Child Sexual Abuse’ (1992) 16(1) Child Abuse and Neglect 101, 118; J D Hawkins, Richard F Catalano and Janet Y Miller, ‘Risk and Protective Factors for Alcohol and Other Drug Problems in Adolescence and Early Adulthood: Implications for Substance Abuse Prevention’ (1992) 112(1) Psychological Bulletin 64.