University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

MARGIN LOANS, IWNSIDER TRADING AND DISCLOSURE OBLIGATIONS: A STUDY OF THE SECURITIES TRADING POLICIES OF THE ASX 100

JULIETTE OVERLAND[*]

Complex legal issues arise when listed company personnel enter margin loans over company securities. Does insider trading occur on a forced sale of company securities if the borrower possesses inside information? If a material number of company securities may be subject to a forced sale, must the listed company disclose it to the market? Are company personnel obliged to inform a listed company they have a margin loan over company securities? There is significant variation in the manner in which listed companies address these issues, which include applying prohibitions, requiring approvals, and obliging notifications. This article undertakes a detailed study of the securities trading polices of the ASX 100 to analyse the ways in which listed companies treat margin loans over company securities. This article proposes law reform and the development of ‘best practice’ recommendations for the treatment of margin loans in the securities trading policies of listed companies.

There is no prescribed manner in which listed companies are expected to treat margin loans over company securities which may be entered into by company personnel, but such arrangements may give rise to a number of complex issues. A forced sale of company securities may give rise to concerns of insider trading where it occurs during a period in which the borrower is not permitted to trade or when they possess inside information. Additionally, a borrower may choose not to respond to a ‘margin call’ if they believe, on the basis of inside information, that it would be more advantageous to allow a forced sale of the securities to occur. If a margin loan is entered into over a material number of company securities, or if it is likely that a material number of company securities may be subject to a forced sale or ‘margin call’, a listed company may be required to make disclosure to the market. However, in the absence of other contractual requirements in place with the relevant company, it is unclear whether directors and other company personnel are generally obliged to inform the company that they have entered into a margin loan over company securities.

This article explores the relationship between margin loans arrangements, insider trading and disclosure obligations, and examines the ways in which these issues relate to the securities trading policies of listed companies. It then undertakes a study of the securities trading polices of the ASX 100, and considers the treatment of margin loans over company securities in those policies to determine whether, for particular company personnel, such arrangements are prohibited, whether approval in advance is required, and whether notification must be given to the company. It examines whether the securities trading policies contain explanations for the various prohibitions, requirements and obligations they contain, and whether there are any additional significant references to margin loans over company securities.

This article analyses the results of the study and proposes reforms to the law and the development of ‘best practice’ recommendations for the treatment of margin loans in the securities trading policies of listed companies, in order to provide greater certainty for company personnel, investors and regulators, as well as the boards of listed companies who are responsible for approving the relevant securities trading policies. The local regulator, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (‘ASIC’) is responsible for the supervision of trading on Australia’s domestic securities markets, on which the securities of the ASX 100 and other listed companies are traded, and has the primary responsibility for detecting insider trading. The Australian Securities Exchange Limited (‘ASX’) governs the admission of companies to the exchange, and publishes the ASX Listing Rules which provide, among other matters, for continuous disclosure by listed entities, supplemented by Guidance Notes published by the ASX, including advice on securities trading policies and the treatment of margin loans in Guidance Note 27.[1] As a result, the findings and recommendations in this article are intended to inform future regulatory developments in these areas.

A margin loan is an arrangement under which a lender advances money to a borrower to enable them to acquire certain financial products, such as listed company securities, against the security of the financial products acquired. Margin loans are generally conditional on an agreed ‘loan-to-value’ ratio being maintained. It was noted by Greenwood J in Storm Financial Limited v Commonwealth Bank of Australia[2] that:

A margin loan is understood in the financial services industry as a loan with a pre-determined limit set by the lender of the proportion the loan balance, owing to a bank, might bear to the value of the securities purchased using the loan. That relationship is described as the relationship the loan bears to the value of the assets or the loan to value ratio or LVR.[3]

If the price of the relevant securities drops so that the loan-to-value ratio falls below the agreed level, the lender may make a ‘margin call’. A borrower who is the subject of a margin call is then required to take action to restore the loan-to-value ratio to the agreed level, which can be done by paying back part of the loan, selling some of the relevant securities, or providing additional security to the lender. If the borrower cannot or fails to take this action, the lender is entitled to have recourse to the relevant securities, and may sell them to recoup or partially recoup the monies owed by the borrower.[4] Margin loans are a popular financing tool used by many investors to fund the purchase of listed securities, enabling them to acquire a larger parcel of securities, securities in a greater number of companies, or a wider variety of total investments, than might otherwise be possible if such purchases needed to be funded solely from the investor’s own funds.

Insider trading is prohibited in Australia on the basis of a ‘market integrity’ rationale, to protect and maintain both market fairness and market efficiency.[5] Proponents of ‘market fairness’ argue that it is unfair for some market participants to have access to price-sensitive information, and to be able to trade on the basis of that information, if it is not also available to others.[6] Ideally, all market participants should have equal access to relevant information when making trading decisions and therefore be exposed to the same trading risks, but company insiders with an ‘unerodable informational advantage’ are able to trade with a reduced risk.[7] Investor confidence in securities markets is arguably reduced if some investors are believed to have the ability to use information which is not readily available.[8] Additionally, in circumstances where price-sensitive information is not released to the market in a timely manner, the prices of financial products cannot be said to accurately represent their true value, and therefore there is an absence of ‘market efficiency’.[9] If those with access to price-sensitive information are able to delay its release to the market to allow themselves time to trade, the efficiency of the market is eroded.[10] Additionally, the participation of some investors in the market may be reduced if those who hold and have access to price-sensitive information are perceived to have a trading advantage.[11] Without confidence in market integrity, investors may choose alternative investments or demand a premium for assuming higher risks, which in turn increases the cost of capital for companies.[12]

The vast majority of countries with securities markets have legislation which prohibits insider trading,[13] and it is prohibited in Australia under section 1043A(1) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (‘Corporations Act’). In Mansfield v The Queen the High Court described the offence of insider trading as follows:

The Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) prohibits trading in securities by persons who possess information that is not generally available and know, or ought reasonably to know, that, if the information were generally available, a reasonable person would expect it to have a material effect on the price or value of the securities.[14]

Despite the use of the term ‘insider trading’, there is no requirement under Australian laws for any particular connection between an insider trader and the relevant company whose financial products are the subject of the trading, or the person or organisation from whom the inside information is obtained.[15] There is an ‘information-connection’ only, which merely requires that the person ‘possesses’ certain inside information.[16] However, most insider trading cases in Australia have involved individuals who would be regarded as ‘true insiders’, due to them having access to the inside information via a connection with the relevant company, or a relationship with a person who had such a connection,[17] with the courts describing certain types of offenders as ‘true insiders’.[18] Company directors and key management personnel are the persons most likely to have access, as part of their positions, to inside information concerning the company.

A question arises as to whether the entry into margin loans, or the sale of company securities pursuant to those arrangements, can give rise to insider trading. This is particularly relevant to consider in the context of a forced sale of securities by a lender after a margin call has been made. There is no defence to a claim of insider trading that the securities were sold as a result of a pressing financial need.[19] However, in addition to the defences and exemptions to insider trading which are contained in the Corporations Act, there are additional exemptions contained in the Corporations Regulations 2001 (Cth) (‘Corporations Regulations’). Regulation 9.12.01 provides that the insider trading prohibition does not have effect in relation to:

(e) a sale of financial products under:

(i) a mortgage or charge of the financial products; or

(ii) a mortgage, charge, pledge or lien of documents of title to the financial products.

The forced sale of company securities by a lender after a margin call will be protected by this regulation, which is not expressly limited to the liability of the lender, and therefore appears to protect both the lender and relevant borrower.[20] Indeed, the Corporations and Markets Advisory Committee (‘CAMAC’) noted that ‘[t]his exemption would cover sales of securities by the lender, and possibly by borrowers, in consequence of margin calls on those securities’.[21] Although CAMAC recommended that this exemption be repealed in order that lenders not be placed in a privileged position compared to other investors,[22] it still remains in force. While the continued existence of regulation 9.12.01 would seem to indicate that insider trading is therefore not relevant to the sale of securities pursuant to a call under a margin loan, these regulations have not been tested judicially, and ASIC commentary indicates a view that there is still potential for insider trading laws to apply.[23]

However, the potential availability of the protection of this regulation to borrowers may have an unintended consequence. If an insider possesses inside information when they receive a margin call, and the inside information indicates that the price of the company’s securities may fall in value in the future, it may be beneficial for the insider to take no action and allow the lender to sell some or all of the company securities under the margin loan.[24] Even if the insider is unable to sell the company securities themselves in order to avoid a future loss because to do so might amount to insider trading, it is clearer that the sale by the lender would not be subject to the prohibition. Accordingly, an insider faced with a margin call may have the option to provide additional security or make other arrangements with the lender in order to avoid the sale of the company securities, but may choose not to do so, in the hope that the lender will sell the company securities to satisfy the margin call in protected circumstances.

There are various company reporting requirements set out in the Corporations Act. Section 298(1) provides that a company must prepare a directors’ report for each financial year, and there are various general and specific matters prescribed that must be included in the report.[25] Under section 300(11) of the Corporations Act, the directors’ report must include, for each director, their relevant interests in shares of the company. There is no requirement, however, for the report to include details of any margin loans or other financing arrangements against which those shares may be secured.

Under section 191(1) of the Corporations Act, a director who has a material personal interest in a matter that relates to the affairs of the company must give the other directors notice of the interest. The Corporations Act does not define ‘material personal interest’, but case law indicates that such an interest must ‘have the capacity to influence the vote of the particular director’.[26] While ASIC considers that, if a director enters into margin loans over company securities, it is a matter that requires disclosure to the board,[27] it is not clear that this will always be the case.

Section 191(2)(a)(i) of the Corporations Act provides that a director does not need to give notice of an interest that arises ‘because the director is a member of the company and is held in common with the other members of the company’. While margin loans may enable a director to obtain or increase a holding in the company, the director’s interest may not always be the same as those of other members, where there is an interest in preserving a particular loan-to-value ratio, or ensuring that a margin call is not made. This may give rise to an actual or perceived conflict of interest for the director but it will not necessarily arise at the time at which the arrangements are entered into, which places the onus on the director to raise the issue of the margin loan at the time when it becomes relevant. It has been noted that ‘[i]t will be difficult in most cases to classify margin lending facilities personally held by company directors as relating to the affairs of their companies’.[28] Thus, it is certainly not clear, where directors of listed companies use margin loans to acquire or hold securities in those companies, whether they are ordinarily required to disclose those arrangements to the company.

ASX Listing Rule 3.1 contains a continuous disclosure obligation for listed companies:

Once an entity is or becomes aware of any information concerning it that a reasonable person would expect to have a material effect on the price or value of the entity’s securities, the entity must immediately tell ASX that information.

The continuous disclosure regime exists to reduce opportunities for insider trading,[29] by compelling companies to disclose information that may materially influence the price or value of their securities, thus making that information generally available.

The obligations in the Listing Rules are also supported by section 674(2) of the Corporations Act, which provides that, where listed entities are subject to a requirement to notify a market operator of certain information, and that information (i) is not generally available and (ii) is information that a reasonable person would expect, if it were generally available, to have a material effect on the price or value of the entity’s securities, it must notify the market operator of that information.

The ASX has indicated that it considers, where a director enters a margin loan over a material number of company securities, that the company may be required, under its continuous disclosure obligation, to disclose the arrangement and additional relevant factors.[30] Whether it is material that the relevant director has entered into a particular margin loan is considered to be a matter for the company to determine in the circumstances.[31] Thus, it is not always clear when listed companies will be required to disclose the existence of margin loans over company securities.

Since directors of listed companies are likely to have access to inside information, any trading by those directors must be the subject of notification to the ASX. A change in the interests of a director of a listed company in the company’s securities must be notified to the ASX by the company within five business days.[32] This obligation is aimed at ensuring that the market is generally aware of trading by directors of listed companies, and to assist in enabling consideration to be given as to whether directors are trading at appropriate times and whether there should be any suspicion that there has been insider trading by directors. In this respect, the company is obliged by the ASX Listing Rules to state whether the director’s trading occurred during a ‘closed period’[33] under its securities trading policy and whether any prior written clearance was necessary or obtained.[34] However, there is no obligation to advise whether the sale of company securities by a director occurred as a forced sale under a margin loan, so it will not ordinarily be clear to the ASX and the market when and whether this has occurred.

Company directors, officers and senior executives are generally encouraged to hold company securities, on the basis that this aligns their interests with those of shareholders.[35] Indeed, many listed companies require directors to obtain a minimum holding upon appointment to the board.[36] The ASX has noted that:

Most people agree that it is generally beneficial for directors and employees of a listed entity to own securities in the entity. It gives them a bigger stake in the success of the entity and helps to align their interests with the interests of investors.[37]

However, as noted above, such persons will often have access to inside information as a result of their position, so the regulation of their trading in company securities can have the dual purpose of reducing the likelihood of insider trading occurring, and reducing perceptions that company insiders can benefit from their access to inside information, at times when it is most likely to be available to them.

Listing Rule 12.9 of the ASX Listing Rules requires all listed companies to adopt and disclose a securities trading policy, which regulates trading in the company’s securities by its key management personnel (‘KMP’).[38] The KMP of a listed company are, of course, subject to insider trading laws regardless of the content of the company’s securities trading policy, but the ASX has noted that ‘the purpose of such a policy is not only to minimise the risk of insider trading but also to avoid the appearance of insider trading and the significant reputational damage that may cause’.[39] Prior to the introduction of this requirement, the ASX Corporate Governance Principles and Recommendations contained a recommendation that listed companies adopt and disclose a securities trading policy.[40] While companies could choose not to do so, those which did not were obliged to disclose that fact in their annual report.[41] Although many listed companies did adopt securities trading policies as recommended, studies revealed a wide variation in the content of the policies.[42] Following a review which ultimately led to the introduction of ASX Listing Rules 12.9 to 12.12 on 1 January 2011, CAMAC noted in its report, Aspects of Market Integrity that:

A more rigorous approach to trading by directors and executive officers during sensitive periods will help bolster investor confidence and market integrity. It would also serve as an effective adjunct to the enforcement of insider trading laws by denying the opportunity for directors and executive officers to transact in the securities of their company during particular price-sensitive periods. It may reduce the opportunity for undetected insider trading.[43]

Under ASX Listing Rule 12.12, a listed company must set out in its securities trading policy, at a minimum:

(i) The company’s closed periods.[44]

(ii) The trading restrictions that apply to the company’s KMP.

(iii) Any trading which is not subject to the company’s securities trading policy.

(iv) Any exceptional circumstances which may permit the company’s KMP to trade during a prohibited period[45] with prior written clearance.

(v) The procedures for obtaining prior written clearance to trade during a prohibited period.

In Guidance Note 27 on Trading Policies, the ASX notes the policy objectives underlying the requirements for listed companies to adopt and disclose a securities trading policy as follows:

Good governance therefore demands that an entity has in place a fit-for-purpose trading policy, tailored to its particular circumstances, that regulates when and how its directors and senior executives may trade in its securities. The purpose of such a policy is not only to minimise the risk of insider trading but also to avoid the appearance of insider trading and the significant reputational damage that may cause.[46]

When considering the entry by KMP of listed entities into margin loans over company securities, the ASX notes several concerns:

It can be embarrassing, both for the entity and KMP, if there is a default and the lender/financier sells some or all of the securities to cover the default. This is especially so if the sale occurs during a prohibited period when the KMP would otherwise be prohibited from selling. However, it can still be embarrassing even if the sale occurs outside of a prohibited period. For example, it may reflect negatively on the business and financial acumen of the KMP in gearing themselves to that extent. If the sale involves a large holding in the entity, it may also overhang or depress the market price of the entity’s securities for a period, which will not please investors. These things in turn may reflect negatively on the entity and its board in allowing this situation to occur.[47]

However, despite the issues which may arise in relation to disclosure, insider trading, and reputation, the ASX refrains from requiring listed companies to prohibit margin loans for KMP, or even from providing ‘best practice’ recommendations for provisions relating to margin loans in securities trading policies. Instead, in 2017, the ASX amended Guidance Note 27 to encourage listed companies to:

Consider carefully whether its trading policy should prohibit KMP and any other employees covered by its trading policy from entering into margin lending or other secured financing arrangements in respect of its securities or, at the very least, require disclosure of such arrangements so that the board and senior management are not caught unawares if there is a default.[48]

In recent times, ASIC has urged listed companies whose securities trading policies do not prohibit directors and officers from entering into margin loans over company securities to carefully consider the appropriateness of such a prohibition.[49] In addition to concerns relating to potential insider trading, disclosure and reputation, ASIC points to conflicts of interest which may drive short-term decision-making and a reluctance to share material information with the market.[50]

It is therefore interesting in this context to consider the position concerning margin loans in overseas jurisdictions.

In the United States of America (‘US’), listed companies must publicly disclose how many company securities each director has pledged as security, which includes margin loans.[51] Further, in 2015, 73% of the top 250 S&P 500[52] companies disclosed that they had adopted ‘anti-pledging’ policies,[53] which prohibit directors and key personnel from using company securities as security for loans, including for margin loans. Such policies have largely been adopted, not because of regulatory requirements to do so, but due to corporate governance recommendations from proxy advisors.[54] Thus, while listed companies in the US are not legally obliged to prohibit or restrict margin loans, many choose to do so in order to retain proxy advisor support.

In the European Union, listed companies must disclose every transaction engaged in by company managers[55] which relates to the shares of the company, once the total value of the transactions reaches €5,000. The transactions which must be notified include the ‘borrowing or lending of shares ... of the issuer’,[56] which include margin loans. Thus, any margin loans entered into by company managers over company securities need to be disclosed once the minimum threshold has been met.

However, in Australia, it remains a matter for each listed company to determine whether or not to prohibit or restrict margin loans, and whether to require any approval or disclosure in relation to margin loans over company securities, as well as to whom such restrictions or requirements should apply. In order to consider how this is occurring in practice, a study has been undertaken on the securities trading policies of the ASX 100.

In the next part of this article, a study of the securities trading policies of the ASX 100 is undertaken in order to determine and analyse their treatment of margin loans over company securities in light of the issues raised and discussed above.

This study used a data sample which comprised the ASX 100 companies, ranked by their market capitalisation, as at 1 September 2019.[57] The ASX 100 represents 74% of Australia’s securities market capitalisation.[58]

As noted above, a company listed on the ASX is required to have a securities trading policy, and to provide the ASX with a copy of that policy for release to the market.[59] However, three of the companies which comprise the ASX 100 are foreign exempt companies, which are not required to adopt and disclose securities trading policies in accordance with Listing Rule 12.9.[60]

Many listed companies choose to make their securities trading policies publicly available via their websites. Accordingly, the relevant data for this study was sought from publicly available sources. The website of each company was searched, and a copy of each company’s securities trading policy was downloaded for review during the first week of September 2019.[61] Accordingly, the securities trading policies of the 97 companies in the ASX 100 which are obliged to have a securities trading policy were obtained and reviewed for this study.

The 97 securities trading policies which were obtained from publicly available sources were reviewed to determine:

(a) whether the policy contains any prohibition on margin loans over company securities; and

(b) if the policy contains a prohibition on margin loans over company securities:

(i) who the prohibition applies to; and

(ii) the nature of the prohibition;

(c) if the policy does not contain a prohibition on margin loans over company securities:

(i) whether there is any requirement to obtain approval in advance or obligation to disclose entry into margin loans to the company; and

(ii) if so, who the requirement or obligation applies to;

(d) whether the securities trading policy contains any explanation for its treatment of margin loans over company securities and, if so, the nature of the explanation; and

(e) whether the securities trading policy contains any other significant references to margin loans.

As at 1 September, the market capitalisation of the companies in the ASX 100 varied from just over $2,000 million up to nearly $140,000 million, and so the 97 companies in this study were categorised into the following groupings according to their market capitalisation – $2,000 million to $5,000 million (22 companies); $5,000 million to $10,000 million (30 companies); $10,000 million to $20,000 million (28 companies); and $20,000 to $140,000 million (17 companies). The 97 companies also fall into 11 different market sectors – Consumer Discretionary (nine companies); Consumer Staples (five companies); Energy (nine companies); Financials (16 companies); Health Care (five companies); Industrials (13 companies); Information Technology (eight companies); Materials (17 companies); Real Estate (nine companies); Telecommunications (two companies); and Utilities (four companies).[62]

When conducting this study, the results were examined to determine if there were any observable patterns relating to the market capitalisation or industry sectors of the relevant ASX 100 companies and commentary on this issue is included throughout this article.

When examining the securities trading policies of the ASX 100 to determine whether margin loans over company securities are prohibited, a variety of variations are observed. Some companies prohibit margin loans, but only in respect of unvested company securities.[63] Some companies apply the prohibition only to directors or the category of persons that can be considered to be KMP. Some companies apply the prohibition to persons who might be likely to have access to inside information as part of their role within the company (‘Company Insiders’). Some companies also apply the prohibition more broadly to all employees. Where companies have securities trading policies which state that margin loans are prohibited unless an approval is obtained in advance, those companies were not treated as prohibiting margin loans for the purposes of this study, but instead as requiring approval in advance of entry into margin loans over company securities.

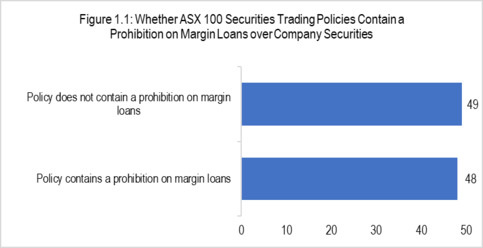

Forty-eight ASX 100 companies have securities trading policies which contain a prohibition on margin loans over company securities (see Figure 1.1).[64] Of those 48 companies, five prohibit margin loans over unvested company securities only, and do not prohibit margin loans over vested company securities.[65] Of the 43 ASX 100 companies which prohibit margin loans over vested company securities, only 12 companies apply that prohibition to all employees.[66] Fifteen companies apply the prohibition to directors or KMP,[67] and 16 companies apply the prohibition to both KMP and Company Insiders (see Figure 1.2).[68] Thus, there are 49 ASX 100 companies which do not prohibit margin loans at all under their securities trading policies (see Figure 1.1), and there are 54 ASX 100 companies which do not prohibit margin loans over vested company securities. There were no observable patterns relating to the market capitalisation or industry sectors of the ASX 100 companies in relation to the prohibition, or not, of margin loans over company securities.

Some companies choose not to prohibit margin loans but instead require certain persons to obtain approval before entering into margin loans. As noted above, where companies have securities trading policies which state that margin loans are prohibited unless an approval is obtained in advance, those companies were not treated as prohibiting margin loans for the purposes of this study, but instead as requiring approval for entry into margin loans over company securities. A distinction has also been made between companies which require certain persons to obtain approval before entering margin loans over company securities, and those which only oblige certain persons to notify them when a margin loan is entered into.

When examining the ASX 100 securities trading policies to determine whether approval is required to enter into margin loans over company securities, a variety of variations were observed. Some companies require only directors or KMP, or Company Insiders, to obtain approval in advance to enter margin loans over company securities. Some companies require all employees to obtain approval in advance to enter margin loans over company securities. Additionally, some companies which prohibit margin loans over company securities for certain persons (such as directors or KMP), place a requirement to obtain approval in advance of entry into margin loans on other persons, such as employees. Of course, where companies prohibit a person from entering margin loans over company securities, there will be no requirement for that person to seek approval to enter a margin loan because it will be a prohibited activity. Also, some companies require certain persons to obtain approval before entering margin loans over company securities, and oblige other persons only to make notification when a margin loan is entered into. Further, some companies which prohibit margin loans only in respect of unvested company securities, require some persons entering margin loans over vested company securities to obtain approval in advance.

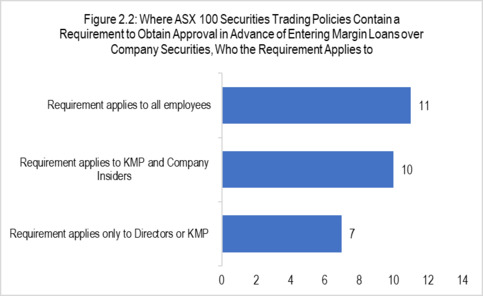

Twenty-eight ASX 100 companies have securities trading policies which require certain persons to obtain approval in advance to enter margin loans over company securities (see Figure 2.1).[69] Of those 28 companies, only seven impose that requirement on all employees.[70] Eleven companies impose that requirement on directors or KMP,[71] and 10 companies impose that requirement on both KMP and Company Insiders[72] (see Figure 2.2).

Of the five ASX 100 companies which have a prohibition on margin loans over unvested company securities only, only two have a requirement for certain persons to obtain approval in advance to enter margin loans over vested company securities.[73] Of those two companies, one requires KMP and Company Insiders to obtain approval in advance to enter margin loans over vested company securities[74] and the other imposes this requirement on all employees.[75]

Of the 69 ASX 100 companies which have no requirement in their securities trading policy to obtain approval in advance to enter margin loans over company securities (see Figure 2.1), 46 have a prohibition on margin loans over company securities.[76] Of those 46 companies, 18 have a prohibition on margin loans over company securities by directors or KMP[77] (three apply the prohibition to unvested company securities only),[78] 16 have a prohibition on margin loans over company securities by KMP and Company Insiders,[79] and 12 have a prohibition on margin loans over company securities by all employees.[80]

Of the 28 ASX 100 companies which have a requirement for certain persons to obtain approval in advance to enter margin loans, two also prohibit margin loans over unvested company securities.[81] One of those companies applies the prohibition to all employees,[82] and the other to KMP and Company Insiders.[83]

There were no observable patterns relating to the market capitalisation or industry sectors of the ASX 100 companies in relation to requirements for certain persons to obtain approval in advance, or not, to enter margin loans over company securities.

Some companies do not prohibit margin loans over company securities, or require approval to be obtained in advance to enter margin loans, but instead contain an obligation for certain persons to notify the company when a margin loan is entered into. Some companies prohibit margin loans over company securities for certain persons, but merely oblige others to notify the company when entering margin loans over company securities. Similarly, some companies require certain persons to obtain approval in advance before entering a margin loan over company securities, but just oblige others to notify the company when entering a margin loan.

Nine ASX 100 companies have securities trading policies which contain an obligation for certain persons to notify the company when entering a margin loan over company securities[84] (see Figure 3.1). Of those nine companies, only two impose that obligation to obtain approval on all employees (see Figure 3.2), and both those companies also have a prohibition on margin loans over unvested company securities.[85] One of those two companies also has a requirement for KMP and Company Insiders to obtain approval in advance to enter margin loans over company securities.[86] Four of the nine companies impose the obligation to notify the company on directors or KMP,[87] and two of the nine companies impose that obligation on both KMP and Company Insiders[88] (see Figure 3.2). One company obliges directors to notify the company of margin loans only if the director’s aggregate holding of company securities is 1% or more – that company does not have any prohibition or requirement to obtain approval in advice.[89]

Of the nine ASX 100 companies which have an obligation for certain persons to notify the company of entry into margin loans over company securities, two also prohibit margin loans for other company personnel over unvested company securities (one for directors or KMP[90] and one for all employees),[91] and one also has a requirement for KMP and Company Insiders to obtain approval in advance.[92]

Of the 88 ASX 100 companies which do not have an obligation in their securities trading policy for certain persons to notify the company of entry into margin loans over company securities, 46 have a prohibition on margin loans over company securities – one for all employees over unvested company securities only,[93] two for directors or KMP over unvested company securities only,[94] 15 for directors or KMP over company securities,[95] 16 for KMP and Company Insiders over company securities,[96] and 12 for all employees over company securities.[97] Additionally, of the 88 ASX 100 companies which do not have an obligation in their securities trading policy for certain persons to notify the company of entry into margin loans over company securities, 27 have a requirement to obtain approval in advance of entering margin loans over company securities – 11 for directors or KMP,[98] nine for KMP and Company Insiders,[99] and seven for all employees.[100]

There were no observable patterns relating to the market capitalisation or industry sectors of the ASX 100 companies in relation to the inclusion of an obligation, or not, to notify the company of entry into margin loans over company securities.

While many companies choose to include an explanation setting out the general rationale for having a securities trading policy, most of which make reference to the need to minimise opportunities for insider trading and ensure compliance with insider trading laws, very few companies include a specific explanation for their treatment of margin loans in their securities trading policy.

Of the 97 ASX 100 companies whose securities trading policies were examined in this study, only 13[101] give an explanation for their treatment of margin loans. Some companies include more than one explanation for their treatment of margin loans over company securities, creating some overlap in the list of explanations which is set out below.

Of the 48 ASX 100 companies with securities trading policies which contain a prohibition on margin loans over company securities, only six give an explanation in their securities trading policy for that prohibition.

Of the 28 ASX 100 companies which have securities trading policies which require certain persons to obtain approval in advance of entering margin loans over company securities, only five give an explanation in their securities trading policy for that requirement.

Of the nine ASX 100 companies which have an obligation for certain persons to notify the company when entering into margin loans over company securities, only two give an explanation in their securities trading policy for that obligation.

Overall, of the 81 companies in the ASX 100 which contain a prohibition, approval requirement or notification obligation in relation to margin loans (see Figure 4.1), only 13 give an explanation in their securities trading policy for the position that is taken (see Figure 4.2). The reasons given as explanations for the various treatments of margin loans include:

(a) the risk that there could be a forced sale of company securities (seven companies);

(b) the risk of the sale of company securities occurring during a closed period (five companies);

(c) the risk of the sale of company securities occurring when the relevant person possesses inside information (seven companies);

(d) the risk of insider trading laws being breached (four companies); and

(e) the risk of compliance with the securities trading policy being compromised or breached (nine companies).

The companies which offer explanations for the position they take in relation to margin loans often include more than one of these reasons, which explains the overlap above (see Figure 4.3). One company[102] gives a particularly detailed explanation for the position that it takes in relation to margin loans:

Most margin loans entitle the lender to dispose of the shares to which the loan is subject in certain specified circumstances without obtaining the consent of or otherwise notifying the borrower. Sometimes this right can be exercised 24 hours after the specified circumstances arise. If a Designated Person were to take out a margin loan and the security for that loan included [company securities], the lender may be able to sell or otherwise Deal in those [company securities]. This would be so notwithstanding that, at the relevant time, there may be a Closed Period or the Designated Person may be in possession of price sensitive information relating to [the company] which is not generally available. This could cause the Designated Person to be in breach of this Policy.

In addition to prohibitions on margin loans over company securities, requirements for approval in advance for margin loans, and obligations to give notification of margin loans, there are a number of additional references to margin loans in the securities trading policies of ASX 100 companies that are worthy of review and discussion.

Forty ASX 100 companies have securities trading policies which contain additional references to margin loans.[103] These additional references to margin loans can be grouped into the following categories: definitions, advice and warnings, insider trading and dealing confirmations, exclusions, market disclosures, conditions, time restrictions, and additional obligations.

(a) Definitions

One company[104] gives a precise definition of a margin loan:

Margin Loan means a loan facility pursuant to which the borrower acquires Securities and over which the lender takes security, entitling the lender, if the LVR exceeds a ratio, percentage or level (however described) that is determined under the terms of the facility, to take action or require the borrower to take action to reduce the LVR.

The policy then separately defines ‘LVR’ to mean ‘the Loan to Value Ratio as determined under the terms of a Margin Loan’.

Other companies have policies which refer to margin loans without specific definitions. This does not of itself appear to be problematic, as it primarily reflects different drafting approaches to this issue, but could cause confusion where arrangements that are caught by one policy are outside the scope of another.

(b) Advice and Warnings

Some companies purport to offer advice to persons affected by the relevant provisions concerning margin loans. A number of securities trading policies state that if company securities are traded under a margin loan where the relevant person is not involved in the decision to trade, the relevant person would not be in breach of the securities trading policy (three companies). Some companies also purport to advise relevant persons about their legal position, such as stating that it is illegal for the person to enter a margin loan over company securities if they have inside information in relation to the company (two companies). This seemingly indicates a desire to protect persons associated with the company from taking action which may place them in breach of the law, and to explain the reasons for including references to margin loans in the policy.

Some companies include a warning about margin loans in their securities trading policies, rather than offering advice. A number of securities trading policies warn relevant persons against entering any margin loans over company securities due to the risk of forced sale of those securities during a closed period in breach of the policy (three companies). Others warn that relevant persons are expected to have sufficient resources to meet a margin call by any means other than the sale of company securities (three companies). Some also warn that if relevant persons have doubts about their ability to meet a margin call by means other than a sale of their company securities, they must take immediate steps to rearrange their affairs to prevent this from occurring (one company). Once again, this seemingly indicates a desire to protect persons associated with the company from taking action which may place them in breach of the law or the securities trading policy.

(c) Insider Trading and Dealing Confirmations

One company specifically notes that the existence of margin loans or similar arrangements may constitute inside information and ‘while not relating directly to the economic performance and prospects of an entity, may be used in connection with various trading strategies by market participants to affect the price of an entity’s securities.’[105]

Some companies specifically confirm that entering into a margin loan over company securities is a ‘dealing’ for the purposes of the securities trading policy (six companies). Of course, it may be the case that entering a margin loan will also arguably amount to a dealing under other policies even without such confirmation, depending upon the drafting of the relevant provisions.

(d) Exemptions

Some companies specifically exclude forced sales by a lender under a margin loan from the operation of the securities trading policy (18 companies), although this may be subject to a requirement that the margin loan was properly approved or notified when entered into. Some companies do note that while the forced sale may be excluded from the operation of the policy, it still remains subject to insider trading laws (four companies). By contrast, other companies specifically provide that the sale of company securities by a lender under a margin loan is covered by the securities trading policy (three companies). While companies are clearly free to draft their policies as considered most appropriate in the circumstances, this variation has the potential to cause confusion for those associated with the company, as well as a lack of certainty for the market in the treatment of margin loans, making this one of the more problematic variations within the securities trading policies.

(e) Market Disclosures

Some companies refer to market disclosure requirements and note that they will disclose margin loans to the market where required to do (six companies) with some noting that this will depend on the materiality of the arrangements to the company and whether the information would, or would be likely to, have a material effect on the price or value of company securities. A margin loan could certainly be material if a significant number or percentage of company shares were to be subject to the loan and there was a real risk of a ‘margin call’ or the lender taking action. Of course, an obligation for the company to make disclosure in such circumstances can arise regardless of whether it is specifically referred to in a securities trading policy.

(f) Conditions

Some companies place conditions on the terms which may be contained in margin loan agreements over company securities. This includes a requirement that margin loans over company securities must not permit title to the company securities to be transferred (two companies), must not be disposed of in a closed period without permission (two companies), must not be disposed of in breach of the securities trading policy (one company), or must not grant a lender the right to sell or compel the sale of company securities at a time when the policy would prevent the relevant person from dealing with the company securities (one company), and that the lender agrees to comply with the securities trading policy (two companies). Other companies, which have requirements for approval in advance, provide that terms and conditions may be imposed as part of that process (two companies). While a breach of these requirements would place the relevant person in breach of the securities trading policy, the lenders proving margin loans are not parties to or subject to the securities trading policies and would not be bound by these requirements.

(g) Time Restrictions

One company, with a prohibition on margin loans for KMP, has a securities trading policy with a provision that allows a person who already has margin loans in place upon becoming a KMP to continue the arrangements for 12 months.[106] This is presumably intended to provide them with some time in order to rearrange their financial affairs in order to come into compliance with the policy.

(h) Additional Obligations

Some companies contain additional obligations to notify the company if a relevant person has a margin loan in place and there is a margin call (one company) or risk of a margin call which cannot be satisfied without the disposal of the company securities (one company). Some companies also require relevant persons to provide additional information about margin loans on request (one company). One company requires relevant persons to certify quarterly that ‘in the event of a margin call during a Blackout Period, sufficient available cash or other acceptable collateral is available to meet these margin calls so as to prevent the sale of [company] securities’.

The study of the securities trading policies of the ASX 100 has shown a significant variation in the treatment of margin loans. Variation exists as to whether margin loans over company securities are prohibited, whether prior approval is required to enter margin loans over company securities, or whether there is a notification obligation once margin loans have been entered into over company securities, and to whom those prohibitions, requirements and obligations apply.

This wide variation in the treatment of margin loans over company securities results in an unsatisfactory lack of clarity on this issue for investors, regulators, and other interested parties. It is difficult, if not impossible, to determine whether the shareholding of a director of a listed company may be subject to margin loans. Additionally, while it is possible to determine how a particular listed company treats margin loans by obtaining and reviewing its securities trading policy, there can be no general expectation as to what that treatment might be.

While directors of listed companies are entitled to structure their personal financial affairs as they see fit, it is argued that the market has an interest in knowing when directors of listed companies have margin loans over company securities. This would make the Australian position more closely aligned with that of the US and European Union. Further, while it may be considered desirable to give the boards of listed companies the ability and freedom to make their own determinations as to how margin loans should be treated in their securities trading policies, it is argued that the market deserves greater certainty in this respect. Accordingly, it is suggested that it would be helpful if there were a ‘best practice’ recommendation which listed companies could be encouraged to adopt.

There is clearly a balance to be struck between allowing persons associated with listed companies to have the freedom to structure their personal financial affairs in the manner they consider the most appropriate, and in a manner that encourages and enables them to invest in company securities, with ensuring that others in the market are not adversely impacted by the results of those decisions.

While the study undertaken and described in this article has focused on the ASX 100, it is acknowledged that other listed companies – particularly those with small capitalisations – may have different requirements than the largest listed companies. For example, smaller listed companies may be more likely to engage in capital raising activities and may need greater flexibility to enable directors and KMP to make personal investments in company securities as part of those capital raisings. Indeed, directors and KMP may be encouraged or expected by other shareholders and investors to participate in a capital raising in order to ensure its success and demonstrate their confidence in the company, and an inability to utilise margin loans or other financing arrangements may limit their ability to participate. Accordingly, a ‘best practice’ recommendation rather than a highly prescriptive approach is likely to be the most appropriate, in order to provide companies with some flexibility to structure their securities trading policies in accordance with their needs while still offering some certainty to regulators, investors and the market.

Accordingly, taking into account the results of the study undertaken in this article, the following recommendations are made:

(a) Recommendation 1 – Listed companies should be required to disclose whether any company securities held by directors have been pledged as security under any loan arrangements, including margin loans.

(b) Recommendation 2 – A set of ‘best practice’ recommendations should be developed for securities trading policies in relation to margin loans over company securities.

(c) Recommendation 3 – The ‘lenders’ exemption’ for insider trading should be removed.

As noted above, section 300(11)(a) of the Corporations Act currently provides that the annual directors’ report for a listed company must include the following details for each director:

(a) their relevant interests in shares of the company or a related body corporate.

In order that details of any margin loans over those company shares must also be included, it is proposed that section 300(11)(a) be amended to read as follows:

(a) their relevant interests in shares of the company or a related body corporate, and any mortgage, charge, pledge or other security interest granted over any of those shares, including any margin loans.

Additionally, section 205G(4) of the Corporations Act provides that a director of a listed company must notify the ASX of any change to their interests in the company’s securities within 14 business days of the change occurring. Section 205G(1)(a) of the Corporations Act specifies the interests as:

(a) relevant interests in securities of the company or a related body corporate.

Consistent with the proposal relating to section 300(11)(a) above, it is proposed that section 205G(1)(a) be amended to read as follows, so that details of margin loans over company securities must also be notified in a timely manner:

(a) relevant interests in securities of the company or a related body corporate, and any mortgage, charge, pledge or other security interest granted over any of those shares, including any margin loans.

As is noted above, the Guidance Note currently suggests that the boards of listed companies should carefully consider whether margin loans should be prohibited or whether disclosure to the board or senior management should be required.[107] Rather than merely suggesting consideration of these issues, it is proposed that the Guidance Note be amended to set out a set of ‘best practice’ recommendations for the treatment of margin loans in securities trading policies, and to state that a listed company should include a statement in its securities trading policy as to whether it complies with those recommendations and, if not, to include an explanation for that non-compliance.

Accordingly, it is suggested that paragraph 5.6 of ASX Guidance Note 27 be redrafted to set out a ‘best practice’ recommendation for the treatment of margin loans. The following is suggested as a potential set of ‘best practice’ recommendations:

In order to provide appropriate certainty to all company KMP, senior executives, employees and other personnel who may be subject to a company’s trading policy, as well as to investors, regulators, and the market, it is recommended that listed companies, adopt the following position in their securities trading policies in connection with the treatment of margin loans, at a minimum:

(a) Directors and KMP should be prohibited from entering into margin loans over company securities, unless approval to enter the margin loan is obtained from the company in advance; and

(b) Company employees and personnel other than directors and KMP are permitted to enter into margin loans over company securities, but have an obligation to notify the company upon entry into a margin loan over company securities, and must comply with any reasonable request from the company for information about the margin loan.

(c) Details of any existing margin loans held by any person who is subject to the securities trading policy must be given to the company within one month of the adoption of this policy.

While listed companies are not obliged to adopt this position in their securities trading policies, a listed company which elects not to do so should set out in its securities trading policy its alternative position in relation to margin loans over company securities and the reasons for doing so.

This is the suggested ‘best practice’ position because, while there will be a prohibition on directors and KMP entering into margin loans over company securities, directors and KMP will be able to do so if they obtain approval in advance. Thus, a company that wishes to allow KMP the flexibility to enter into margin loans in certain circumstances will be able to do so, but it will also ensure that the company has the power to approve and reject requests for approval, as well as ensuring that the company is aware of any margin loans which are entered into through this process. A company that does not wish to have directors and KMP enter into margin loans over company securities will be able to deny approval for any request to enter into a margin loan. There will be greater freedom for employees and personnel who are not directors or KMP to enter into margin loans over company securities, but a company will be made aware of any margin loans which are entered into, due to the requirement that the company be notified upon entry.

As has been discussed, Corporations Regulations regulation 9.12.01 provides that the insider trading prohibition does not have effect in relation to:

(e) a sale of financial products under:

(i) a mortgage or charge of the financial products; or

(ii) a mortgage, charge, pledge or lien of documents of title to the financial products.

This regulation will provide protection in the case of a forced sale of company securities by a lender under a margin loan, and may protect both the lender and the borrower. In order to avoid preferential treatment for lenders, and to ensure there is no additional protection for borrowers, this exemption should be repealed, as was previously recommended by CAMAC.

It has been demonstrated in this article that there is a very wide variation in the treatment of margin loans over company securities in the securities trading policies of the ASX 100. When considering the key issues which formed the basis of the study conducted, it was shown through an examination of 97 securities trading policies that:

(a) Forty-eight ASX 100 companies have a securities trading policy which contains a prohibition on margin loans over company securities, but there is variation in whether the prohibition applies to KMP, Company Insiders, or employees generally, and whether it applies to both vested and unvested company securities. 49 ASX 100 companies do not have any prohibition on margin loans in their securities trading policy.

(b) Twenty-eight ASX 100 companies have a securities trading policy which requires certain persons to obtain approval before they enter into margin loans over company securities, but there is variation in whether the requirement applies to KMP, Company Insiders or employees generally.

(c) Nine ASX 100 companies have an obligation in their securities trading policy for certain persons to notify the company when they enter into margin loans over company securities, but there is variation in whether the obligation applies to KMP, Company Insiders or employees generally.

(d) Eighty-one ASX 100 companies have a securities trading policy which contains either a prohibition on margin loans over company securities for certain persons, a requirement for certain persons to obtain approval before entering into margin loans over company securities, or an obligation for certain persons to notify the company when margin loans are entered into over company securities. Of those companies, only 13 give an explanation in their securities trading policy for the position they have taken.

(e) Sixteen ASX 100 companies have a securities trading policy which does not contain a prohibition on margin loans over company securities, a requirement to obtain approval before entering into margin loans over company securities, or an obligation to provide notification when margin loans are entered into over company securities. Of those companies, five have other references to margin loans in their securities trading policy, and 11 have a securities trading policy which contains no reference to margin loans at all.

(f) There is only one ASX 100 company with a securities trading policy which contains a prohibition on margin loans for certain persons, a requirement for certain persons to obtain approval in advance, and an obligation for certain persons to notify the company when margin loans are entered into. That company prohibits margin loans over unvested company securities for all employees, requires KMP and Company Insiders to obtain approval in advance to enter margin loans over company securities and obliges other employees to notify the company when margin loans over company securities are entered into.

Due to this significant variation, it has been proposed in this article that it would be appropriate for amendments to be made to the Corporations Act so that directors of listed companies who enter margin loans over company securities would be obliged to provide this information to the ASX, and listed companies would be obliged to include this information in their annual directors’ report, for a ‘best practice’ recommendation for the treatment of margin loans over company securities by listed companies to be included in the ASX Guidance Note 27 on Trading Policies, and for the ‘lenders’ exemption’ to insider trading to be removed from the Corporations Regulations. Such developments would be likely to lead to increased uniformity and less variation in the treatment of margin loans in securities trading policies, and would provide increased guidance for listed companies, greater clarity for investors, regulators, and other interested parties, as well as greater certainty for the market. Additionally, it would better conform with the underlying rationale for the adoption and use of securities trading policies – the minimisation of the risk of insider trading and the avoidance of both the appearance of inappropriate trading and any resulting damage to the reputation of the company or relevant parties. Lenders and borrowers under margin loans would also be placed in the same position as other investors in company securities.

The findings of the study undertaken in this article indicate the degree to which ASX 100 companies are acting upon the ASX recommendation that they consider whether KMP and any other employees should be prohibited from entering into margin loans over company securities to require disclosure of such arrangements. While it is encouraging that 81 ASX 100 companies have a securities trading policy which contains either a prohibition on margin loans over company securities, a requirement that approval be obtained in advance of entering into margin loans over company securities, or an obligation to notify the company when margin loans are entered into over company securities, it is somewhat discouraging that the remaining 16 ASX 100 companies which formed part of this study have no such prohibitions, requirements or obligations, particularly as there are 11 ASX 100 companies which have no reference to margin loans in their securities trading policy at all. It is hoped that the findings of the study undertaken in this article will lead to a consideration of appropriate amendments to the Corporations Act and Corporations Regulations, and the adoption of a ‘best practice’ recommendation for the treatment of margin loans over the securities of listed companies, as well as further regulatory scrutiny in this area.

[*] LLB (Hons I) (QUT), PhD (ANU), Associate Professor, Business Law, University of Sydney Business School. The author would like to thank Alexandra Touw, B Com/LLB student at the University of Sydney, and Amelia Burns, JD student at the University of Sydney, for research assistance provided in connection with the preparation of this article. The author would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers of this article for their helpful feedback and suggestions.

[1] ASX, Listing Rules: Guidance Note 27, Trading Policies (at 23 August 2019) 3.

[3] Ibid [9].

[4] Explanatory Memorandum, Corporations Legislation Amendment (Financial Services Modernisation) Bill 2009 (Cth) 9–10.

[5] Mansfield v The Queen [2012] HCA 49; (2012) 247 CLR 86, 90 (WB Zichy-Woinarski QC) (during argument) (‘Mansfield v The Queen’).

[6] Phillip Anthony O’Hara, ‘Insider Trading in Financial Markets: Legality, Ethics, Efficiency’ (2001) 28(10–12) International Journal of Social Economics 1046, 1053.

[7] Victor Brudney, ‘Insiders, Outsiders and Informational Advantages under the Federal Securities Laws’ (1979) 93(2) Harvard Law Review 322, 356.

[8] See, eg, Australian Securities and Investments Commission , ‘Competition for Market Services – Trading in Listed Securities and Related Data’ (Consultation Paper No 86, ASIC, 23 July 2007); Utpal Bhattacharya and Hazem Daouk, ‘The World Price of Insider Trading’ (2002) 57(1) Journal of Finance 75; Laura Nyantung Beny, ‘Insider Trading Laws and Stock Markets Around the World: An Empirical Contribution to the Theoretical Law and Economics Debate’ (2007) 32(2) Journal of Corporation Law 237; Companies and Securities Advisory Committee, Insider Trading (Discussion Paper, June 2001) 1 [0.3]; Lori Semaan, Mark A Freeman and Michael A Adams, ‘Is Insider Trading a Necessary Evil for Efficient Markets?: An International Comparative Analysis’ (1999) 17(4) Company and Securities Law Journal 220, 222.

[9] Eugene F Fama, ‘Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Empirical Work’ (1970) 25(2) Journal of Finance 383, 413–16.

[10] Keith Kendall, ‘The Need to Prohibit Insider Trading’ (2007) 25(2) Law in Context 106.

[11] Bhattacharya and Daouk (n 8); Companies and Securities Advisory Committee (n 8) 15 [1.22]. It is also worth noting that some commentators consider that insider trading creates an efficient market by providing a mechanism for the distribution of information: see, eg, Michael Whincop, ‘The Political Economy of Corporate Law Reform in Australia’ [1999] FedLawRw 4; (1999) 27(1) Federal Law Review 77, 110; Michael Whincop, ‘Towards a Property Rights and Market Microstructural Theory of Insider Trading Regulation – The Case of Primary Securities Markets Transactions’ (1996) 7(3) Journal of Banking and Finance Law and Practice 212.

[12] Ashley Black, ‘The Reform of Insider Trading Law in Australia’ [1992] UNSWLawJl 10; (1992) 15(1) University of New South Wales Law Journal 214, 220.

[13] Franklin A Gevurtz, ‘The Globalisation of Insider Trading Prohibitions’ (2002) 15(1) Transnational Lawyer 63, 65.

[14] Mansfield v The Queen [2012] HCA 49; (2012) 247 CLR 86, 90; see also Juliette Overland, Corporate Liability for Insider Trading (Routledge, 2019) 14; Juliette Overland, ‘What Is Inside “Information”? Clarifying the Ambit of Insider Trading Laws’ (2013) 31(3) Company and Securities Law Journal 189.

[15] The original prohibition of insider trading under the state Securities Industry Acts focused on a ‘person-connection’, with primary liability for insider trading being dependent on a person being ‘connected with a body corporate’. This approach resulted in a distinction between ‘primary insiders’ – those who possessed inside information and had a connection with the relevant corporation (such as directors, officers, substantial shareholders, and those who had some form of business or professional relationship with the corporation) – and ‘secondary insiders’ – generally tippees who knowingly received the inside information from a primary insider. See also Companies and Securities Advisory Committee (n 8) 23–4 [1.58]–[1.62]; Overland, Corporate Liability for Insider Trading (n 14) 44–5.

[16] Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) s 1043A(1)(a). Any person who possesses inside information will be regarded as an ‘insider’ for the purposes of the prohibition on insider trading. As noted by the majority of the High Court, ‘[t]he provisions ... do not refer to who provided the information or to what connection that person had with the corporation in question’: Mansfield v The Queen [2012] HCA 49; (2012) 247 CLR 86, 97.

[17] Juliette Overland, ‘Do Insider Trading Laws Need a Reboot? How Advances in Technology are Turning “Outsiders” into “Insiders”’ (2019) 34(2) Australian Journal of Corporate Law 187, 187.

[18] See, eg, R v Rivkin [2004] NSWCCA 7; (2004) 184 FLR 365, 443 [409] (The Court); R v Doff [2005] NSWCCA 119; (2005) 54 ACSR 200, 212 [57] (The Court); R v McKay [2007] NSWSC 275; (2007) 61 ACSR 470, 480 [53] (Whealy J); DPP (Vic) v O’Reilly [2010] VSC 138, [22] (Forrest J); R v O’Brien [2011] NSWSC 1553; (2011) 91 ACSR 374, 384 [51] (Hoeben J); R v Dalzell [2011] NSWSC 454; (2011) 83 ACSR 407, 418 [102] (Hall J); R v De Silva (2011) 84 ACSR 240, 254 [61] (Buddin J); R v Mansfield [2011] WASCA 132; (2011) 251 FLR 286, 313 [126] (Buss JA); R v Fysh [No 4] [2012] NSWSC 1587; (2012) 92 ACSR 116, 123 [42] (McCallum J); R v Glynatsis [2012] NSWSC 1551, [155] (Johnson J); R v Glynatsis [2013] NSWCCA 131; (2013) 230 A Crim R 99, 104 [25] (Hoeben CJ); Khoo v R [2013] NSWCCA 323; (2013) 237 A Crim R 221, 226 [21] (Bellew J); R v Zhu [2013] NSWSC 127, [189] (Hall J); DPP (Cth) v Gay (2015) 26 Tas R 149, 155 [21] (Estcourt J); R v Joffe and Stromer (2015) 106 ACSR 525, 539–40 [107]–[109] (Hulme J); R v Xiao [2016] NSWSC 240, [176] (Hall J); R v Curtis [No 3] (2016) 114 ACSR 184, 196 [54] (McCallum J); Xiao v The Queen [2018] NSWCCA 4; (2018) 96 NSWLR 1, 20 [114] (The Court).

[19] Corporations and Markets Advisory Committee, Aspects of Market Integrity (Report, June 2009) 21 (‘CAMAC’).

[20] See also, Juliette Overland, ‘The Insider Trading Implications of Directors’ Margin Loans’ [2009] JlLawFinMgmt 4; (2009) 8(1) Journal of Law and Financial Management 20, 22.

[21] CAMAC (n 19) 54.

[22] Ibid 61.

[23] Cathie Armour, ‘ASIC Says It’s Time to Review Margin Loans’, Australian Institute of Company Directors (Web Page, 1 February 2019) <https://aicd.companydirectors.com.au/membership/company-director-magazine/2019-back-editions/february/regulator>.

[24] The potential for this to occur was noted by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission in its submission to CAMAC on the Aspects of Market Integrity Issues Paper: CAMAC (n 19) 55.

[25] Certain general matters are set out in section 299 and certain specific matters in section 300 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth).

[26] McGellin v Mount King Mining NL (1998) 144 FLR 288, 304 (Murray J).

[27] Australian Securities and Investments Commission and Australian Securities Exchange, ‘Disclosure Guidance for Listed Companies’ (Media Release 08-37, 29 February 2008).

[28] Tim Poisel and Andrew Terrett, ‘Transparency and Disclosure: Implications of the Bear Raid on ABC Learning Centres’ (2009) 27(3) Company and Securities Law Journal 139, 150.

[29] James Hardie Industries NV v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2010] NSWCA 332; (2010) 274 ALR 85, 162 [355] (The Court); as noted by the ASX in Listing Rules: Guidance Note 8, Continuous Disclosure: Listing Rules 3.1–3.1B (at 28 February 2020) 6–7.

[30] ASX, ‘Important Information for ASX Listed Entities’ (Companies Update 02/08, 29 February 2008). The ASX also notes that this may require disclosure of ‘the key terms of the arrangements, including the number of securities involved, the trigger points, the right of the lender to sell unilaterally and any other material details’.

[31] Ibid.

[32] ASX, Listing Rules (at 1 December 2019) r 3.19A.2. Appendix 3Y to the Listing Rules is to be used to make the notification. The company is responsible for making and enforcing any necessary arrangements with its directors to ensure that it is able to comply with this obligation: ASX, Listing Rules (at 1 December 2019) r 3.19A.3. Additionally, a director of an Australian listed company must notify the relevant exchange of any change to their interests in the company’s securities within 14 business days under section 205G(4) of the Corporations Act, but if the company has already notified the ASX, the director need not make an additional notification: Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) s 205G(5).

[33] A ‘closed period’ is a fixed period when an entity’s key management personnel (‘KMP’) are prohibited from trading in the entity’s securities: ASX, Listing Rules (at 19 December 2019) r 19.12.

[34] ASX, Listing Rules (at 1 December 2019) r 3.19A.2.

[35] See, eg, ASX Corporate Governance Council, Corporate Governance Principles and Recommendations (Report No 4, February 2019) 14, where it is noted that ‘the holding of securities in [an] entity may help to align the interests of a director with those of other security holders’.

[36] ‘Skin in the Game’, Australian Institute of Company Directors (Web Page, 1 May 2016) <www.companydirectors.com.au/director-resource-centre/publications/company-director-magazine/2016-back-editions/may/skin-in-the-game>.

[37] ASX, Listing Rules: Guidance Note 27, Trading Policies (at 23 August 2019) 3.

[38] ASX Listing Rule 19.12 uses the definition of ‘key management personnel’ in AASB 124 Related Party Disclosure, which provides that ‘[k]ey management personnel are those persons having authority and responsibility for planning, directing and controlling the activities of the entity, directly or indirectly, including any director (whether executive or otherwise) of that entity’: Australian Accounting Standards Board, Related Party Disclosures (AASB 124, July 2015) 7.

[39] ASX, Listing Rules: Guidance Note 27, Trading Policies (at 23 August 2019) 5.

[40] ASX Corporate Governance Council, Corporate Governance Principles and Recommendations (Report No 2, August 2007) Recommendation 3.2.

[41] ASX, Listing Rules (at 1 December 2019) r 4.10.3.

[42] Ian Ramsay and Chander Shekhar, ‘Company Security Trading Policies: An Empirical Study’ (2012) 30(1) Company and Securities Law Journal 55, 57.

[43] CAMAC (n 19) 93.

[44] Closed periods are fixed periods when KMP are prohibited from trading in the entity’s securities: ASX, Listing Rules (at 19 December 2019) r 19.12.

[45] A prohibited period is defined to mean:

i. any closed period; or

ii. additional periods when an entity’s KMP are prohibited from trading, which are imposed by the entity from time to time when the company is considering matters which are subject to Listing Rule 3.1A

: ASX, Listing Rules (at 1 December 2019) r 19.12.

[46] ASX, Listing Rules: Guidance Note 27, Trading Policies (at 23 August 2019) 5.

[47] Ibid 13.

[48] Ibid.

[49] Armour (n 23).

[50] Ibid.

[51] SEC Regulation S-K § 229.403 provides that a listed company must disclose the number of equity securities beneficially owned by each director, and indicate the amount of those shares that are pledged as security: 17 CFR § 229.403 (2006).

[52] The S&P 500 is an index of the largest 500 companies listed on stock exchanges in the US: ‘S&P 500’, S&P Dow Jones Indices (Web Page) <https://us.spindices.com/indices/equity/sp-500>.

[53] Jihun Bae and Ruishen Zhang, ‘Anti-Pledging Policy, CEO Compensation and Investment’ (Research Paper, 9 September 2019) <https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3445348>

[54] Ibid.

[55] The obligation relates to ‘persons disclosing managerial responsibilities’: Regulation (EU) No 596/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 April 2014 on Market Abuse [2014] OJ L 173/1, art 19(1). Such persons are then defined in article 3(1)(25) as a person who is:

(a) a member of the administrative, management or supervisory body of that entity; or

(b) a senior executive who is not a member of the bodies referred to in point (a), who has regular access to inside information relating directly or indirectly to that entity and power to take managerial decisions affecting the future developments and business prospects of that entity.

[56] Commissioned Delegated Regulation (EU) 2016/522 of 17 December 2015 Supplementing Regulation (EU) No 596/2014 [2015] OJ L 88/1, art 10(2)(p).

[57] The ASX 100 list of companies is available at the ‘ASX Top 100 Companies’, ASX 100 List, (Web Page, 1 September 2019) <http://www.ASX 100list.com> .

[58] Ibid.

[59] ASX, Listing Rules (at 19 December 2019) r 12.9.

[60] In accordance with rule 1.11 of the ASX Listing Rules, a foreign company can be admitted to the official list as an ASX Foreign Exempt Listing. In such circumstances, the foreign company is obliged to comply with the listing rules of its foreign home exchange. A company admitted as a Foreign Exempt Listing must comply with the listing rules set out in rule 1.15, and need not comply with the others. Rule 12.9, requiring companies to adopt and disclose a securities trading policy is not included in rule 1.15 and therefore such companies need not comply with it.