University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

THE POTENTIAL OF RESTORATIVE JUSTICE IN PROMOTING ENVIRONMENTAL OFFENDERS’ ACCEPTANCE OF RESPONSIBILITY

HADEEL AL-ALOSI[1]* AND MARK HAMILTON[1]**

Restorative justice conferencing offers promise in dealing with the harm flowing from environmental crimes. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime outlined four critical ingredients necessary for restorative justice to achieve its objectives. One of these critical ingredients is that the offender accepts responsibility for the offence. In another article, we explored this requirement, outlining how contrition and remorse can be evidence of an acceptance of responsibility. In this article, we go further by questioning whether environmental crime offenders who do not accept responsibility for the offending should necessarily be excluded from participating in restorative justice conferencing. As will be seen, the benefits of conferencing with offenders who seem reluctant to accept responsibility may outweigh its disadvantages. This is particularly because the facilitated dialogue can provide a golden opportunity for the offender to come to realise the harm caused by their offending and its impact on victims.

The air we breathe, the water we drink, and the land we live on are all potentially affected by environmental crimes. Such crimes encompass a wide range of illegal activity including pollution of land, air and water,[1] breaching of an environmental protection licence,[2] harming of flora and fauna,[3] and the desecrating of Aboriginal cultural heritage.[4] These crimes can have a wide range of victims, including individuals, whole communities (present and future generations), the environment (such as plants, animals, and ecosystems) and commercial operators. Therefore, there must be effective strategies to respond to and prevent environmental crimes. The traditional criminal justice system is the most common way of responding to and deterring such crimes. However, the problem with traditional prosecution is that it tends to neglect the needs of victims and fails to give them a voice in the process. Hence, the mechanisms of restorative justice (as described in detail below) have much to offer in helping address environmental crimes because they encourage victim input.[5] Although restorative justice can take many forms, it is restorative justice in the form of face-to-face conferencing that we focus on in this article.[6] Essentially, conferencing facilitates a dialogue between the relevant stakeholders. This dialogue has much greater potential than traditional criminal processes to achieve significant benefits for all those involved and in working towards reparations.

If used, restorative justice processes can occur at different stages within the criminal justice system. These mechanisms can be deployed pre-charge, post-charge but before trial, after conviction but before sentencing the offender, and after sentencing the offender.[7] In this article, we are concerned with victim-offender restorative justice conferencing embedded as part of court proceedings and held before an offender is sentenced. We refer to this as a ‘back-end model’ of conferencing to highlight that it is embedded in the prosecution process and not used as a diversion from the criminal justice system, as is the case in a ‘front-end model’ of conferencing.[8]

The United Nations through its Office on Drugs and Crime (‘UNODC’) has developed the ‘Handbook on Restorative Justice Programmes’ as one of a series of practical tools to support countries to implement restorative justice approaches within their criminal justice systems.[9] The UNODC Handbook states there are at least four critical ingredients needed for any restorative justice process: (1) an identifiable victim; (2) voluntary participation; (3) an offender who accepts responsibility for their criminal behaviour; and (4) non-coercion.[10] These ingredients are seen as essential to achieve the objectives of restorative justice processes and to help promote consistency and the effectiveness of such processes specifically in the context of the criminal law (as opposed to civil litigation, family law matters, or resolving conflict within the workplace or at school).

Although we go through each of the UNODC ingredients in this article, we focus on the third ingredient, that is, the requirement that the offender accepts responsibility for the behaviour. This requirement is demanded by other organisations and jurisdictions that have embraced restorative justice practices. For example, in the Canadian ‘Principles and Guidelines for Restorative Justice Practice in Criminal Matters’, it states that an underpinning for using these processes is that ‘[o]ffenders must be willing to accept responsibility for their actions and for the harm caused to victims and communities’.[11] Similarly, one of the principles in New Zealand’s ‘Restorative Justice: Best Practice Framework’ requires that the ‘offender must acknowledge responsibility for the offence before the case can be accepted for a restorative justice process’.[12] In the Australian state of New South Wales (‘NSW’), the Restorative Justice Unit of Corrective Services states that a victim-offender conference will only take place if the ‘offender takes responsibility for the offence’.[13]

Contrition and remorse can be useful indicia that an offender accepts responsibility for their behaviour in the context of environmental crimes.[14] It is of critical importance to demonstrate such acceptance to avoid placing victims in a situation where they are confronted by an offender who continues to deny doing anything wrong. Indeed, the Restorative Justice Unit is guided by a ‘to do no harm’ principle,[15] which is an important consideration when thinking about involving victims in restorative justice processes.

However, we explore how restorative justice conferencing may still be of utility in cases where offenders do not accept responsibility, so long as they do not deny it either. Accordingly, in this article, we explore whether restorative justice conferencing should go ahead in the context of environmental crimes even though the third UNODC critical ingredient is missing. As will be seen, in some cases, restorative justice conferencing may be effective in achieving its objectives by involving offenders who have not explicitly accepted responsibility. This is because, through conferencing, such offenders may gain insight into their offending, in which the gravity of their offending and the impact on victims become clear. Therefore, such offenders should not be automatically excluded from engaging in the process.

To help our analysis, we refer to relevant environmental case law throughout this article, including the only two environmental law cases in Australia that have used restorative justice conferencing.[16] Also informative is New Zealand case law because that country has given restorative justice conferencing legislative recognition since 2002 and conferencing has been used frequently to deal with environmental crimes.[17]

The remainder of this article is divided into four parts. In Part II, we discuss the definitions and origins of restorative justice. The potential advantages and disadvantages of restorative justice conferencing are canvassed in Part III. In Part IV, we explore the UNODC critical ingredients necessary for restorative justice to achieve its objectives. In Part V, we critically analyse the requirement that an offender must accept responsibility for offending in order to be deemed suitable for participation in restorative justice. In doing so, we assess whether this ingredient is too restrictive and thereby impeding the attainment of insight, which can be promoted and reached in conferencing.

There is no universal definition of restorative justice processes and mechanisms. Although several definitions have been proposed in the literature, the commonality among them is that such processes involve those affected by crime collectively working towards repairing the harm caused by the offending. Restorative justice processes can take various forms, which makes developing an agreed upon definition of such processes difficult. This article is focused on restorative justice in the form of victim-offender conferencing, which gives the victim a central role in the process alongside the offender.[18] Marshall’s definition, which is commonly cited and captures the inclusive nature of restorative justice, characterises restorative justice as ‘a process whereby all the parties with a stake in a particular offence come together to resolve collectively how to deal with the aftermath of the offence and its implications for the future’.[19]

At an international level, UNODC provides a similar definition of restorative justice as:

any process in which the victim and the offender, and, where appropriate, any other individuals or community members affected by a crime, participate together actively in the resolution of matters arising from the crime, generally with the help of a facilitator.[20]

A more recent useful definition worth noting specifies that:

Restorative justice involves a voluntary, relational process whereby those with a personal stake in an offence or conflict or injustice come together, in a safe and respectful environment, with the help of skilled facilitators, to speak truthfully about what happened and its impact on their lives, to clarify accountability for the harms that have occurred, and to resolve together how best to promote repair and bring about positive changes for all involved.[21]

Although the roots of restorative justice reach far back in history,[22] its modern roots seem to have developed in 1974 in Ontario, Canada.[23] It was then that restorative justice conferencing was allowed by the presiding judge in a case involving the vandalising of 22 properties.[24] Since then, restorative justice practices have become a common feature of criminal justice systems across the world. For example, in the United States, victim-offender conferencing has been commonly used in Indiana since 1977.[25] In New Zealand, restorative justice arose in response to concerns that the criminal justice system was culturally inappropriate[26] and an ‘imposed, alien, colonial system’ to Maori people.[27] Family group conferences have been the common response to deal with juvenile offending in New Zealand since 1989[28] when legislation commenced aimed at advancing the welfare of families, children and young persons.[29] Family group conferencing involved a government-provided facilitator conducting conferences between the victim, offenders, and their families to find solutions to conflict.[30]

Drawing on the New Zealand family group conferences, police-facilitated conferencing began in Wagga Wagga (Australia) in 1991.[31] The first conference was facilitated by a police officer in a case involving motorcycle theft, which resulted in the offender making arrangements to repair and return the motorcycle stolen.[32] A statutory scheme has since replaced the ‘Wagga Wagga Model’ as it had become known.[33] That scheme is compulsory, applies to juvenile offenders and is a diversion from formal court processes.

More recently, restorative justice practices have been used in other contexts, such as when sentencing Aboriginal offenders in circle sentencing,[34] and for convicted and imprisoned offenders in the form of victim-offender conferencing.[35] Restorative justice has also been used outside the criminal justice system as a way to respond to conflict arising in the workplace[36] and schools,[37] as well as a way to deal with cyberbullying.[38]

The growth of restorative justice initiatives throughout the world arose in response to the criticisms of traditional criminal justice systems during the 1970s. The main criticism was that victims were excluded in the prosecution and therefore their needs were not being met; in the traditional criminal justice system, victims were seen as no more than ‘footnotes to the crime’.[39] There was also concern that offenders found guilty were not being held accountable for their offending in the sense that they were not facing up to what they had done, appreciating the harm they had caused not only to the victim but also society, and not taking steps to repair that harm.[40] This is because offenders, in the hands of their counsel, have no real input into court proceedings and do not have an interactive dialogue with victims.[41]

As noted above, the focus of this article is on a back-end model of restorative justice conferencing. Although there is no universal example of a back-end model of conferencing, it typically has the following features:

• conferencing is ‘embedded as part of sentencing and not as a diversion from prosecution’;

• the conference is ‘closed to the public and under the guidance of a trained and independent facilitator’; and

• the process is ‘inclusive in that the relevant stakeholders are welcomed to attend’ the conference.[42]

The embedded nature of the back-end model of restorative justice conferencing in the context of environmental offending is summarised in Figure 1 below.[43]

Figure 1: Stages in a Back-End Model of Conferencing

As illustrated in Figure 1, the first stage of the back-end model of conferencing is the commencement of the prosecution in court. In the NSW Land and Environment Court, criminal proceedings will usually involve the filing of the summons and supporting affidavits,[44] which outline the charge(s) alleged. As in all typical criminal trials, the prosecution must prove matters beyond reasonable doubt.[45]

The second stage involves establishing the facts surrounding the offending. Those facts can be established collegiately between the prosecution and the offender and reduced into an ‘Agreed Statement of Facts’, which is then tendered to the court and used by the court throughout the case.[46] If the prosecution and the accused disagree about the facts, each party will need to present their version of the facts to the court. The court will make rulings on all aspects of the evidence and will need to reach a final determination as to what version it will accept. Therefore, it can be a more timely and costly process when the facts are contested.

During stage two, the court will also use the facts established to make a determination of guilt. This determination will usually be straightforward where the offender has pleaded guilty. If the accused has pleaded not guilty, the prosecution will have to prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. Arguably, a plea of guilty may be seen as acceptance of responsibility and a plea of not guilty as a denial of responsibility. However, as argued later in this article, whether the accused pleads guilty should not and cannot be seen as determinative of acceptance of responsibility.

Stage three involves an assessment as to the suitability of conferencing in the given case. In a NSW environmental offending context there is no legislative basis for the use of conferencing. However, if a ‘defendant enters a plea of guilty, the prosecutor and defendant are to advise the [NSW Land and Environment] Court of any proposal for, and timing of, any restorative justice process ...’[47] Conferences can also be suggested by the presiding judge, as was the case in Garrett v Williams (‘Williams’).[48] In New Zealand, restorative justice processes are supported by legislation.[49] There is also specific legislation requiring the consideration of holding a restorative justice process if requested by a victim.[50] Likewise, there is legislative support for the court to ‘enable inquiries to be made by a suitable person to determine whether a restorative justice process is appropriate in the circumstances of the case’.[51] The UNODC critical ingredients can help with the suitability assessment.

In stage four, the court is adjourned for a conference to be held by an independent facilitator. The conference can provide offenders with an opportunity to explain the circumstances surrounding the crime and for victims to express the harm suffered as a result of the offending and work together to repair that harm. Experts may be invited to attend if further articulation of the harm to the environment and suitability of outcomes is needed. Other individuals or entities with a stake in the matter can attend conferencing. In some instances, the regulatory or prosecutorial authority will attend, but there is some contestation over the presence of these authorities in conferences.[52]

In NSW there is no legislative provision that explicitly permits the Land and Environment Court to adjourn proceedings for a conference to occur. However, there is legislative power for the court to ensure the ‘efficient management and conduct of the trial or sentencing hearing’,[53] which would extend to an adjournment to enable a restorative justice conference to be pursued. In contrast, in New Zealand, legislation exists that explicitly allows the court to adjourn the proceeding to allow the restorative justice process to occur.[54] At the conclusion of the conference, the facilitator will prepare a report detailing the agreed outcomes reached.

Following the conference, the matter will return to the court for sentencing in stage five. In NSW, although it is not mandated in legislation, the Land and Environment Court may take into account the offender’s participation in a conference and the outcomes reached at that conference when sentencing the offender.[55] An incentive for the offender to engage in a conference is that it might lead the court to mitigate the penalty it imposes. The benefit for the victim of the offender agreeing to participate in a conference is that they would have input in directing any outcomes reached rather than merely accepting a penalty being imposed unilaterally by a court.

There are other benefits of conferencing, too, which are discussed in more detail in Part III.

In this part, we consider the main pros and cons of restorative justice conferencing in the context of environmental crimes.[56] It is useful to outline them again here to reinforce why conferencing is an appealing option to deal with environmental matters.

One advantage of restorative justice conferencing over traditional prosecution is the communication it facilitates between the offender and the victim. Conferencing can facilitate an ‘[i]nteractive conversation [which] allows for immediacy in a question and answer exchange and allows a more genuine exchange than the sterile environment of a court room’.[57] Hamilton highlights three main benefits of this communication: the victim is able to talk about the effect of the crime; the victim can ask the offender questions directly about why they committed the crime; and the offender can explain the circumstances behind the crime, which may assist in giving the victim closure.[58] Having the ability to directly hear the effects the crime has had on the victim means that the offender is in a better position to understand the gravity of their wrongdoing. It is an ‘approach which encourages an offender to gain insight into the causes and effects of his or her behaviour and take responsibility in a meaningful way’.[59] This cognitive and emotional transformation may improve the offender’s relationship with the community and the victims.[60] The offender also has the opportunity to tell the victim why they committed the crime, bringing the victim much-needed closure and the ability to articulate how they believe the harm can be repaired.

Another advantage of victim-offender conferencing over traditional prosecution is its victim-centredness. It shifts the focus away from punishing the offender to meeting the needs of victims. Conferencing is where ‘victims’ views and interests count, where they can participate and be treated fairly and respectfully and receive restoration and redress’.[61] The victim-centredness of victim-offender conferencing is not a feature of all restorative justice processes; some processes focus mainly on offenders and changing their behaviour. Other processes may focus on communities by changing the way that individuals relate to each other and resolve conflict and are therefore primarily targeted at achieving broader social change.

Upon gaining insight, an offender is more likely to provide a genuine apology to the victim. An apology is an expression of sorrow and regret[62] that in itself may help victims heal from harm and trauma.[63] It entails:

1. identifying the wrongful act;

2. expressing remorse and regret for having committed the act;

3. promising to forbear from committing the wrongful act in the future; and

4. offering to repair the harm caused.[64]

Offering an apology can be an indication of acceptance of responsibility for offending and recognition of the harm the offending has had on victims. Nevertheless, an apology should not be expected or forced; it should come naturally when an offender has gained insight into their wrongdoing. Likewise, victims should not feel pressured to accept an apology or offer forgiveness. Forgiveness may show a ‘willingness to overcome resentment or anger’, and it can ‘promote reparative behaviour and de-escalation, increasing well-being and reducing a desire for revenge by victims of injustice’.[65] Restorative justice conferences should not proceed on the basis of ‘some preconceived notion that apology and/or forgiveness is necessary to its success’.[66] Indeed, ‘it is wrong to ask victims to forgive and very wrong to expect it of them. Forgiveness is a gift victims can give. We destroy its power as a gift by making it a duty’.[67]

‘Identifying restorative, forward-looking outcomes’[68] is an objective of restorative justice that focuses on the harm caused and the reparation an offender can make to resolve that harm. Rather than a judge unilaterally imposing punishment on the offender, in conferences all the key players as far as possible have input in devising outcomes to repair the damage done. Thus, conferencing is advantageous because of the wide range of outcomes that can be reached by the parties. Fines have traditionally been the dominant order imposed in cases involving environmental crimes. The monetary penalties are usually directed to consolidated revenue and are not necessarily used to repair the harm occasioned by the offending. An advantage of restorative justice is that it helps the parties develop outcomes that are tailored to restore the damage done and provides victims with the opportunity to articulate what they need for the environment to be repaired.[69] It is desirable that the restorative, forward-looking outcomes agreed to at a conference are made into court orders to ensure that the outcomes are enforceable, which can give victims legal recourse if the offender fails to fulfil the agreed outcomes and the offender may be subject to contempt proceedings. The NSW Land and Environment Court has a wide repertoire of penalties and remedies which it can make into court orders.[70] However, even if outcomes could not be reached in a conference, the process in itself may be beneficial and therapeutic for the participants (especially the victims) because it allows them to be heard and obtain closure.

Nevertheless, there are some notable limitations of restorative justice, including the perception that it is a ‘soft’ approach to crime. On the other hand, some of the outcomes agreed to in conferencing are more demanding than traditional punishments. For example, in Williams, the outcome included a $32,200 donation to establish the Wilykali Pinnacles Heritage Trust, along with other commitments, the dollar value of which was not quantified.[71] This is despite the maximum penalty for each of the three offences being $5,500 and/or six months imprisonment.[72] As another example, in Canterbury Regional Council v Interflow (NZ) Ltd[73] the offender agreed in conferencing to donate $80,000 to repair the harm that had been caused by its offending, whereas the fine likely to have been imposed by a court would have been less than half of that amount.[74]

However, restorative justice conferencing may be ineffective in achieving reparation if the outcomes agreed to are not realistic or achievable. Victims may be left disappointed and with no way to have the orders enforced because, unless the outcomes are made into court orders, they are not binding. Indeed, whether the outcomes will be fulfilled are dependent upon the goodwill of offenders. To help avoid such disappointment, the facilitator should reinforce to the parties the importance of developing realistic and credible outcomes at conferencing that are capable of being fulfilled within a specific timeframe. To help ensure that outcomes are met, they should not be overly harsh or punitive.[75] The problem of restorative justice outcomes being disproportionate to the gravity of the crime can be alleviated by court oversight of the matter, such that the ‘results of agreements arising out of restorative justice programmes should, where appropriate, be judicially supervised or incorporated into judicial decisions or judgements’.[76] The benefit of this is that non-fulfilment of the outcomes will carry consequences and can be legally enforced.[77] For example, in Chief Executive, Office of Environment and Heritage v Clarence Valley Council (‘Clarence Valley Council’),[78] one of the conference outcomes reached was the offender agreeing to fund a project to help repair the damage caused to the sacred scar tree. When the matter was returned to court for sentencing, Chief Judge Preston determined the quantum of that funding to be $300,000 and made the outcome legally enforceable by making it a court order. Non-compliance with the order would result in the offender being subject to a charge of contempt of court.

A criticism of restorative justice conferencing is that it can take longer and be more costly than traditional court proceedings.[79] The added time and expense is primarily due to pre-conference preparations, such as assessing offender suitability, as well as contacting and meeting with the relevant parties to explain the process.[80] Time is then required for the actual conference to be held and post-conference requirements, such as the facilitator writing a report setting out the agreed outcomes and conducting follow-up with the participants. These factors add time to the prosecution process and add to costs, such as in the form of facilitator costs.[81] However, given the potential for better outcomes to be reached in repairing the harm done to the environment, the additional costs associated with conferencing may be a worthy investment. To help ensure it is a worthwhile investment and to avoid wasted resources, each case must be suitable for restorative justice conferencing. In Part IV, we discuss the indicia provided by UNODC that help with the suitability selection process.

The UNODC Guidelines state that there are four main ‘critical ingredients’ required for a restorative justice process to achieve its objectives. They are:

1. an identifiable victim;

2. voluntary participation by the victim;

3. an offender who accepts responsibility for his/her [or its] criminal behaviour; and

4. non-coerced participation of the offender.[82]

At face value, the four critical ingredients seem straightforward and provide essential safeguards to protect victims incurring further harm by engaging in restorative justice processes.[83]

The objectives of restorative justice processes identified by UNODC are:

• supporting victims by giving them a voice in the process and thereby allowing them to express their needs;

• giving victims a say in how an offender is to make reparation and offering those victims assistance;

• helping the participants reach a consensus on how to repair relationships damaged by crime;

• highlighting to the offender the consequences of their offending on the victim and community, and reinforcing that such behaviour is unacceptable;

• helping offenders accept responsibility for their wrongdoing;

• identification of forward-looking outcomes that are restorative;

• reducing recidivism and reintegrating offenders back into the community; and

• the identification of factors leading to crime and referral for crime reduction strategy.[84]

UNODC claims that these ingredients ‘create a non-adversarial, non-threatening environment in which the interests and needs of the victim, the offender, the community and society can be addressed’.[85] The ingredients are also important in protecting the rights of offenders and victims, as well as to prevent re-victimisation.[86]

Below we explore each of these critical ingredients in further detail and demonstrate how each ingredient applies in the context of environmental offending.

The first UNODC critical ingredient for restorative justice to achieve its objectives is ‘an identifiable victim’.[87] Identifying the victim in most cases, such as those involving murder or sexual assault, will usually be straightforward. However, identifying the victim of environmental crimes can be complicated because the direct victims are often non-human and, therefore, cannot report the offence. For example, a river is not able to vocalise its victimisation. Hence, it is pertinent that regulatory authorities are proactive in identifying victims, as well as enforcing compliance with laws and policies designed to protect the environment. Human victims of environmental offending include individuals,[88] present and future communities,[89] as well as commercial operators.[90] Non-human victims can include native vegetation,[91] a river or marine life (such as fish, eels, and birds) that have been harmed or killed because of water pollution, for example.[92]

Notions of ‘victim’ and ‘victimhood’ arise in the sentencing of environmental offending rather than those terms being defined in the legislation regulating NSW[93] and New Zealand[94] environmental offending. For example, in NSW, ‘the extent of the harm caused or likely to be caused to the environment by the commission of the offence’ is a statutory matter to be considered in imposing a penalty.[95] Likewise, in New Zealand, when sentencing an environmental offender, the focus will be on the ‘nature of the environment affected’ and the ‘extent of the damage afflicted’.[96] Therefore, victim participation in an environmental prosecution is through written affidavit evidence and expert statements, and occasionally oral testimony, to help establish the extent of the harm occasioned to the environment through the offending. In this sense, victim participation is not a right arising directly from legislation, but rather a by-product of the sentencing process.[97]

In terms of Aboriginal cultural heritage offending, notions of victimhood are often embedded in the offence itself; without cultural significance to Indigenous communities, there may be no offence.[98] For example, in Williams, Maureen O’Donnell and other members of the Broken Hill Local Aboriginal Land Council participated in conferencing, both as individual victims but also as representatives of the affected local Aboriginal community.[99]

Humans will need to represent the non-human victims of environmental crimes (such as a forest or animal) for the apparent reason that non-human victims cannot vocalise the harm incurred. Human representatives can come from government organisations[100] (such as environment and protection agencies and, local government),[101] non-governmental organisations[102] (for example, a river enhancement trust,[103] and community trust),[104] community members,[105] and Indigenous peoples.[106] The issue of advocacy (who should speak on behalf of non-human entities) and expertise (who should talk about non-human entities) arise in this context. White frames this as the problem of expertise (that is, ‘issues of evidence and expertise from the point of view of identifying who speaks for and on behalf of whom’).[107] The inclusive nature of restorative justice conferencing means inclusivity of voice, with both expert and community voices being included. Yet, considerations of practicality will necessarily require a balancing of such voices as it will not always be practical to hear from everyone. A set of indicia and criteria will need to be developed to decide who will speak for and about non-human entities in the specifics of a given case.

The second UNODC critical ingredient for restorative justice is ‘voluntary participation by the victim’.[108] For the consent to be valid, it must be informed, meaning that victims must have been informed of their rights, told the nature of the process, and have explained to them the consequences of their decision to participate. Where a crime has several victims, each victim must give informed consent. Sometimes not all victims may want to participate in the process. In that case, the conference should go ahead only with the consenting victims.

Voluntary participation also helps to ensure the objectives of restorative justice conferencing are achieved. A victim who is forced to attend conferencing may not be ready to talk about the effect the offending has had on them or to confront the offender. Forcing a victim to participate may be re-victimising for that victim and therefore cause further harm.

The third UNODC critical ingredient for restorative justice to achieve its objectives requires ‘an offender who accepts responsibility for his/her criminal behaviour’.[109] The nature of environmental offending is unique and diverse. Offenders can include individuals and organisations (such as corporations and government entities). The harm inflicted on the environment may be transient and of negligible impact, or it may be long-lasting and devastating, or it may lay somewhere in-between. The offending may be accidental, deliberate, negligent, or reckless. It may occur in the context of a one-off endeavour or as part of an ongoing enterprise. The offending may be an isolated incident, or it may be repeated behaviour. These factors are important when considering the utility of restorative justice conferencing in any given case. Environmental offending may be caused without an appreciation of the gravity of harm to victims.

Alternatively, the offending may have been a result of a breakdown of environmental or information systems designed to prevent breaches of the law. This is especially relevant to environmental offending where activities such as mining and development may be potentially harmful to the environment unless effective internal procedures and practices are utilised to minimise the potential harm to the environment. Other offending may occur without the offender knowing that their actions breach the law. These factors may impact an offender’s willingness to accept responsibility for their offending.

In the case where the offender is an organisation or corporation, the entity will often be liable for the actions of their employees that caused the harm. In such a case, it is not required for every employee to accept responsibility for the entity’s offending. Rather, acceptance must be demonstrated by the entity through those that bind the corporation. So, even though some individual employees may deny responsibility, this will not necessarily prevent conferencing involving the corporation represented by upper management or directors who have accepted responsibility for the offending.

Although we have discussed in depth how acceptance of responsibility can be demonstrated elsewhere,[110] it is useful to set it out again here briefly. As discussed, an offender who shows contrition and remorse can provide strong indicia of this acceptance.[111] In summary, contrition and remorse can be evidenced by an offender who:

1. takes action to rectify harm;

2. voluntarily reports the offence;

3. takes action to redress causes of the offence; and

4. shows genuine regret and develops plans to avoid reoffending.[112]

For example, the offenders in both Williams and Clarence Valley Council exhibited behaviour consistent with contrition and remorse, which led to them being deemed suitable to participate in a restorative justice conference. Both offenders demonstrated unequivocal acceptance of responsibility by, among other things, apologising to the victims. Additionally, both offenders helped in the authority’s investigation of the crime and in the preparation of an agreed statement of facts which sets out the relevant facts surrounding the offending.[113]

Notably, both offenders in Williams and Clarence Valley Council pleaded guilty to the charges.[114] It may be tempting to deem offenders suitable for conferencing because they have pleaded guilty to the offence. Although a guilty plea may be construed as evidence of acceptance of responsibility, it is not always the case because such plea may have been entered for a variety of reasons. For instance, some offenders may plead guilty solely because they were acting on legal advice that conviction was inevitable and that pleading guilty at the earliest opportunity can lead to a penalty discount.[115] Consequently, contrition and remorse are better indicators of acceptance of responsibility for offending than a guilty plea.[116]

The requirement of acceptance of responsibility may be seen as a safeguard of the ‘to do no harm’ principle,[117] even though it is the Restorative Justice Unit which espouses that principle and not UNODC. That is, conferencing will only take place if the ‘offender acknowledges full responsibility [for the offending], demonstrates empathy for the victims of the offence and insight into their offending behaviour’.[118] However, as will be canvassed in Part V of this article, we question whether acceptance of responsibility is too restrictive.

The last UNODC critical ingredient for restorative justice to achieve its objectives is ‘non-coerced participation of the offender’.[119] Like victims, offenders should have the right to choose whether they participate in a restorative justice conference, and such a decision should have been made freely. A refusal by an offender to participate in a conference should not lead to the court imposing a harsher penalty, as doing so would be antithetical to the requirement of non-coerced and voluntary participation.

Non-coercion is a safeguard that can help prevent causing further harm to victims in a conference. It is a safeguard because an offender who is forced into participating is likely to be hostile towards the victim, try to diminish the impact of the crime, not be forthcoming about the reasons for their offending, and/or be unwilling to work towards resolution of the harm occasioned.

Non-coercion should also extend to the formulation of any outcomes reached in conferencing because coercing offenders to agree to any outcome is unlikely to result in compliance and unlikely to elicit a genuine apology. Offenders should be encouraged to formulate and agree to meet achievable targets to repair the harm occasioned by the offending. An offender’s failure to agree to any reasonable outcome should not be used by a court to impose a harsher penalty, especially as there may be situations where the victims may ask for unreasonable outcomes. To avoid unduly harsh or inappropriate outcomes, facilitators should discuss with victims in the pre-conferencing stage what can realistically be achieved in a conference, what the possible penalties are if the matter was dealt with by a court, and why agreeing to outcomes should not be coerced. However, victims should be told of the option of having the outcomes reached made into legally enforceable court orders.

Having reviewed each of the UNODC critical ingredients for restorative justice to achieve its objectives, we argue that the requirement that an offender accepts responsibility for offending before a conference can take place is unduly restrictive. We start this argument by noting that the communicative and educative benefits of restorative justice conferencing can lead to offenders realising the gravity of their offending. Many offenders may not readily accept responsibility, especially when the impact of the crime has not been articulated to them by those most affected by their wrongdoing. Thus, it is questionable whether the third UNODC ‘critical ingredient’ is indeed critical to meet the objectives of restorative justice conferencing.

Insight is the ability to have ‘a clear, deep, and sometimes sudden understanding of a complicated problem or situation’;[120] it also provides ‘a chance to understand something or learn more about it’.[121] Insight can be attained by engaging in a restorative justice conference because the dialogue it facilitates with the stakeholders offers offenders understanding into the causes, gravity, and consequences of their offending. Importantly, this insight can significantly increase the willingness of offenders to accept responsibility and to repair the harm occasioned by their wrongdoing.

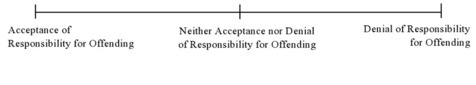

Even though all offenders may have the ability to gain insight by participating in a restorative justice conference, in some cases the risk of re-victimising victims may be too great if the offender denies responsibility outright. Therefore, we suggest that only offenders who explicitly accept responsibility for offending, and those offenders who have not expressly accepted responsibility but have not denied it either, be considered for conferencing involving the victim. To illustrate the kind of offenders that may be potentially suitable for conferencing, despite not fulfilling the third UNODC critical ingredient, we have developed a continuum in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2: Acceptance/Denial of Responsibility for Offending Continuum

On the left-hand side of the continuum are those offenders who have shown acceptance of responsibility, which can be evidenced by contrition and remorse. Provided the other ingredients are met (that is, an identifiable victim, voluntariness, and non-coercion), such offenders would be ideal for conferencing because they are likely to be respectful towards the victims and work with them together to develop outcomes directed at repairing the harm. The offenders in Williams and Clarence Valley Council are both examples of offenders who are ideal and suitable for restorative justice conferencing because of their demonstrable contrition and remorse.

On the other side of the spectrum are those who deny responsibility for their wrongdoing. These offenders may exhibit behaviours denying responsibility by, for example, attempting to conceal the offending, blaming the victims for the harm, or not cooperating in the relevant regulatory authority’s investigation. That is not to say that such offenders would not benefit from engaging in restorative justice conferencing because it may provide an optimal environment for insight to be gained. However, the risk of causing the victim further harm by placing them in a room with a hostile offender who denies responsibility may be too great and not a risk worth taking, especially when the chances of the offender gaining insight are low.

In between the two opposites of the continuum are offenders who neither deny nor accept responsibility for their offending. Even though they may not exhibit contrition and remorse, they do not exhibit behaviour that is consistent with denial of responsibility either. Such offenders, for example, may not have apologised to the victim or shown a hesitancy to do so. They may be offenders who have not understood their actions constitute an offence and have not had the impact of their offending explained to them. A strict application of the UNODC Guidelines would result in these offenders being deemed as unsuitable for conferencing because they have not explicitly or unequivocally accepted responsibility for the offending. Yet, it is these offenders who may have the most to gain from engaging in the process because the open dialogue created in the conference has great potential for them attaining insight into their offending. Accordingly, this insight may lead to better outcomes for the environment, victims, and the community. Therefore, the requirement of acceptance of responsibility for offending should not of itself be a bar to engaging in a restorative justice conference.[122]

Screening offenders to determine their suitability in the pre-conference stage is essential.[123] Provided that all the other UNODC ingredients are met, where the offender has not met the third requirement of acceptance of responsibility, a further assessment should be conducted to determine the potential of them gaining insight and subsequently accepting responsibility for their offending.

The pre-conference assessment should be conducted by an independent and skilled facilitator who considers the offender’s actions as a whole. If during a pre-conference assessment the facilitator comes to the view that conferencing is not suitable, they should inform the court of that view. In that situation, the offender should not be dealt with more harshly by the court because of any unsuitability to participate in a restorative justice conference.

We have developed a list of relevant factors to help determine whether the offender who has not explicitly accepted responsibility would be suitable for conferencing:

• their willingness to hear the victim’s views;

• whether they are hostile towards the victim;

• their capacity and readiness to listen to the victim and understand the impact the crime has had on the victim;

• whether they have shown any desire to repair the harm caused;

• the effectiveness of any previous restorative justice processes the offender has participated in; and

• whether they have exhibited any behaviours that indicate they will deny responsibility and be unlikely to gain insight.

Our list is not intended to be exhaustive, and the reasons for the offender’s actions in each case should also be queried. For example, a failure to apologise to the victim may be because the offender did not have an opportunity to do so or because they do not know the significant detriment their offending had on the environment and human victims. In that case, a conference would provide an ideal setting for dialogue between the participants and an apology to occur.

Additionally, the pre-conference stage should also involve a risk assessment to gauge the potential harm to the victim if the offender does not reach such acceptance of responsibility in conferencing. This pre-conference assessment should be guided by the ‘to do no harm’ principle, which means that where there is a real risk of further harm to the victim, the conference should not be held.

As part of the pre-conference assessment, victims should be informed of the risks and benefits of participating in the conference, including the risk of offenders occupying the centre position of the acceptance/denial of responsibility for offending continuum not accepting responsibility. The facilitator should provide the victim with information on what can be realistically achieved in conferencing to ensure the victim is not disillusioned about what outcomes can be reached and is not disappointed if the offender does not accept responsibility during the conference.

As a procedural safeguard, victims and offenders should be able to withdraw their consent to participate in the conference at any time. This safeguard can help victims to remove themselves from the process if continuation in that process would cause detriment, especially when it becomes evident that the offender is not willing to accept responsibility, thereby diminishing the chances of conferencing leading to insight into their offending. The facilitator should also have the ability to end the restorative justice conference if it is not meeting its objectives. Post-conference follow-up with victims should be held to ensure they have not been harmed during the process and to refer them to any other support if needed.

The most thorough way of establishing the extent to which restorative justice conferencing has provided an offender insight into their offending is through empirical evidence. That is, an interview with an offender or direct observation of the restorative justice conferencing itself. Where this is not possible or practical, evidence of insight may be derived from court judgments themselves. That is, court judgments may be useful in highlighting how conferencing can promote an offender’s insight into offending. This, however, requires those judgments to contain sufficient details of any restorative justice conferencing processes and outcomes. Sufficient detail is not always present. For example, in New Zealand, environmental offending is prosecuted before the District Court.[124] Notwithstanding the fact that the court judgments are made available to the public, including through online sources such as court websites, the restorative justice conference report is confidential, and therefore, not available to the public. There are numerous examples of New Zealand District Court judgments containing scant details of the restorative justice process utilised.[125] This prevents gaining a true understanding of the success or otherwise of the conference and ascertaining the insight into the offending the offender has attained through the conferencing process. One of the few cases where the District Court has provided sufficient detail is Auckland City Council v Shaw.[126]

In that case, the defendant (Shaw) was the sole director and shareholder of a development company who was charged with the felling of a large Pohutukawa tree on land purchased for townhouse development.[127] This action constituted ‘an offence because no resource consent had been obtained from Auckland City Council’.[128] The offence was premeditated and committed with a commercial motive.[129] Shaw was aware of the need for a resource consent and was aware that such consent was unlikely to be granted.[130] The offence was described as being ‘carried out in a cynical fashion and it took considerable council resources to determine who the offenders were’.[131]

He participated in a restorative justice conference with many concerned community members. The conference was conducted by an experienced facilitator and was unusually held ‘in public and in the glare of the cameras’.[132] The conference

allowed many affected people to express their views about the value of the tree to them, and the effects of this offending upon them. That had value for those who were upset at what had happened, for the defendant, who could experience first-hand the effects of his conduct on others, and ultimately for the public in terms of shaping a proposal to ‘put right the wrong’ for the benefit of the community.[133]

At the conference, the tree’s historical significance and visual amenity were explained. Shaw explained that the offence occurred because of financial stress and a desire to sell the property. He said he was leaving the property development industry, offered an apology and expressed he was deeply remorseful for his actions. At the conference, Shaw accepted the criticisms levelled at him by the local residents present, and expressed the desire to repair the harm caused and make things right. This repair was to come through the planting and maintenance of a replacement tree and other tree plantings.[134] Upon the request of the conference facilitator, a second conference was facilitated about four weeks after the first. The purpose of the second conference was to discuss outcomes to repair the harm that had been caused by the offending, including the exact details of the tree planting.[135]

Shaw’s insight can be evidenced by his change of attitude from the commencement of the proceedings to the conclusion of the restorative justice conference. His original position was one of ‘defiance and denial’.[136] Conversely, his attitude post-conference was one of ‘deep regret and remorse’,[137] which can be evidenced through the various public apologies issued (primarily at the restorative justice conferences), listening to the ‘grievances of many people, fronting up to them personally and not seeking to hide behind counsel or excuse his conduct’.[138] The presiding judge was of the view that engagement in the conference had led to Shaw’s ‘change of heart – which is not at all uncommon in restorative justice processes’.[139] The restorative justice conference provided Shaw with a window of insight into the extent of the harm his offending had caused; a window which seems to have been previously shut.

Restorative justice processes offer promise in repairing the harm caused by all sorts of crimes. We focus in this article on the utility of restorative justice conferencing in the context of environmental crimes, highlighting the superiority of conferencing in achieving dialogue between the stakeholders of a crime and in working towards reparation. Not all cases are suitable for conferencing. UNODC provides guidance by suggesting four critical ingredients needed to meet the objectives of restorative justice. These four ingredients are: (1) an identifiable victim; (2) voluntary participation of the victim; (3) an offender who has accepted responsibility for their offending; and (4) non-coercion of the offender to participate.[140]

These requirements seem like straightforward and logical safeguards at first glance. However, upon further examination of the third ingredient, which is also demanded by other organisations, it is evident that the requirement that the offender accepted responsibility before a conference can be considered as an option is too restrictive. This is because offenders who have not accepted responsibility may gain insight during the conference and therefore come to accept responsibility for their wrongdoing. The moment of insight that can be gained by engaging in the restorative justice process has a significant potential of achieving far greater benefits for the victims and community in repairing the harm done to the environment than if the matter was dealt with in the traditional court system.

Consequently, offenders who do not readily accept responsibility for offending should not be automatically excluded from restorative justice conferencing because it is these offenders that have the most to gain from engaging in the process. Rather than make acceptance of responsibility a strict prerequisite, offenders should be assessed on a case-by-case basis to see whether restorative justice conferencing would help them learn the impact of their wrongdoing and come to accept responsibility. To help determine suitability, the pre-conference stage should involve the facilitator undertaking a risk assessment to determine the utility of conferencing, assessing offender suitability, as well as the likelihood of the offender attaining insight, and thereby accept responsibility for their offending. Importantly, the assessment should be guided by the ‘to do no harm’ principle. If the risk of re-victimising the victim is great (because there is little prospect of the offender accepting responsibility), the conference should not be held. Thus, while the UNODC ingredients are insightful, a caveat should be made that allows consideration of allowing offenders who have not explicitly accepted responsibility for offending to participate in a conference. This is to avoid precluding offenders who have a real chance of attaining insight. Only time and practice will reveal whether this approach to restorative justice conferencing in the context of environmental crimes leads to preferred outcomes.

* Academic and researcher. LLB/Social Science (Criminology)(Hons)(UNSW); PhD (UNSW).

** Sessional tutor/lecturer and lawyer. BSc, LLB (UoW); MEL, LLM (USyd); MPP (Macq); PhD (UNSW). Correspondence to Dr Mark Hamilton: mark.hamilton@unsw.edu.au.

[1] See, eg, Protection of the Environment Operations Act 1997 (NSW) pts 5.3, 5.4, 5.6.

[2] See, eg, ibid s 64.

[3] See, eg, Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 (NSW) pt 2.

[4] See, eg, National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 (NSW) s 86.

[5] Hadeel Al-Alosi and Mark Hamilton, ‘The Ingredients of Success for Effective Restorative Justice Conferencing in an Environmental Offending Context’ [2019] UNSWLawJl 51; (2019) 42(4) University of New South Wales Law Journal 1460.

[6] The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (‘UNODC’) describes five common models of restorative justice – victim-offender mediation, community and family group conferencing, circle sentencing, peacemaking circles and reparative and community boards and panels: UNODC, ‘Handbook on Restorative Justice Programmes’ (Handbook, United Nations, 2006) 14–25 (‘Handbook 1st ed’).

[7] Ibid 13–14.

[8] For an overview of front-end models of conferencing functioning as a diversion from prosecution in an environmental offending context, see Margaret McLachlan, ‘Environmental Justice in Canterbury’ (2014) 37(4) Public Sector 22; Environment Canterbury Regional Council, ‘Resource Management Act Monitoring and Compliance Section: Guidelines for Implementing Alternative Environmental Justice’ (Report No R12/81, August 2012); Ministry of Environment (British Columbia), ‘Community Environmental Justice Forums Policy’ (Policy Document, June 2012); Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy (British Columbia), ‘Community Environmental Justice Forums: Questions and Answers’ (Brochure); Ministry of Environment (British Columbia), ‘Community Environmental Justice Forums’ (Brochure, April 2012).

[9] UNODC, ‘Handbook 1st ed’ (n 6). A second edition of the Handbook was released in early 2020: UNODC, ‘Handbook on Restorative Justice Programmes’ (Handbook, United Nations, 2nd ed, 2020) (‘Handbook 2nd ed’).

[10] UNODC, ‘Handbook 1st ed’ (n 6) 8.

[11] Canadian Intergovernmental Conference Secretariat, ‘Principles and Guidelines for Restorative Justice Practice in Criminal Matters’ (Web Page, 2018) <https://scics.ca/en/product-produit/principles-and-guidelines-for-restorative-justice-practice-in-criminal-matters-2018/>.

[12] Ministry of Justice (NZ), ‘Restorative Justice: Best Practice Framework’ (Report, 2017) 11 (emphasis added). This document builds upon the earlier Ministry of Justice (NZ), ‘Restorative Justice: Best Practice in New Zealand’ (Report, 2011), which dictated that a ‘case should not be referred to, or accepted for, a restorative justice process unless an offender has acknowledged responsibility for the offence’: at 16.

[13] Corrective Services, Department of Justice (NSW), ‘Victim Offender Conferencing: Restorative Justice Team’ (Brochure) <https://correctiveservices.dcj.nsw.gov.au/content/dcj/csnsw/csnsw-home/download.html/content/dam/dcj/corrective-services-nsw/documents/victims/Restorative%20Justice%20brochure.pdf> 1.

[14] Al-Alosi and Hamilton (n 5) 1485–8.

[15] Jane Bolitho, ‘Putting Justice Needs First: A Case Study of Best Practice in Restorative Justice’ (2015) 3(2) Restorative Justice: An International Journal 256, 272.

[16] Garrett v Williams [2007] NSWLEC 96; (2007) 151 LGERA 92 (Preston CJ) (‘Williams’); Chief Executive, Office of Environment and Heritage v Clarence Valley Council (2018) 236 LGERA 291 (Preston CJ) (‘Clarence Valley Council’).

[17] Pursuant to the Sentencing Act 2002 (NZ) and Victims’ Rights Act 2002 (NZ). The first recorded use of restorative justice in this context was the case of Auckland Regional Council v Times Media Ltd (Auckland District Court, McElrea DCJ, 16 June 2003), discussed in RM Fisher and JF Verry, ‘Use of Restorative Justice as an Alternative Approach in Prosecution and Diversion Policy for Environmental Offences’ (2005) 11(1) Local Government Law Journal 48, 57.

[18] The extent of victim participation in restorative justice depends on the process used. Participation exists along a continuum: victim as a central participant – one of many participants – indirect victim involvement – a surrogate victim is used – little or no victim involvement. See UNODC, ‘Handbook 1st ed’ (n 6) 16.

[19] Tony F Marshall, ‘The Evolution of Restorative Justice in Britain’ (1996) 4(4) European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research 21, 37.

[20] Basic Principles on the Use of Restorative Justice Programmes in Criminal Matters, ESC Res 2002/12, 37th plen mtg, UN Doc E/RES/2002/12 (24 July 2002) annex [2] (‘Basic Principles on the Use of Restorative Justice Programmes in Criminal Matters’) in UNODC, ‘Handbook 2nd ed’ (n 9) 5.

[21] Chris Marshall, ‘Restorative Justice’ in Paul Babie and Rick Sarre (eds) Religion Matters: The Contemporary Relevance of Religion (Springer, 2020) 101, 103–4.

[22] Howard Zehr, The Little Book of Restorative Justice: Revised and Updated (Good Books, 2015) 19 (‘The Little Book of Restorative Justice’). Restorative justice was prevalent in antiquity, especially in Jewish, Christian and Islamic traditions: see, eg, Marshall (n 21).

[23] Howard Zehr, Changing Lenses: Restorative Justice for Our Times (Herald Press, 25th Anniversary Edition, 2015) 159–60; Michael S King, ‘Restorative Justice, Therapeutic Jurisprudence and the Rise of Emotionally Intelligent Justice’ [2008] MelbULawRw 34; (2008) 32(3) Melbourne University Law Review 1096, 1104.

[24] Zehr, Changing Lenses: Restorative Justice for Our Times (n 23) 159–60.

[25] Ibid 160.

[26] King (n 23) 1104.

[27] Zehr, The Little Book of Restorative Justice (n 22) 62. For an overview of the emergence of New Zealand practices arising from Maori traditions, see Masahiro Suzuki and William Wood, ‘Restorative Justice’ in Antje Deckert and Rick Sarre (eds), The Palgrave Handbook of Australian and New Zealand Criminology, Crime and Justice (Palgrave, 2017) 393.

[28] Zehr, The Little Book of Restorative Justice (n 22) 6, 62.

[29] Children, Young Persons, and Their Families Act 1989 (NZ).

[30] Barbara E Raye and Ann Warner Roberts, ‘Restorative Processes’ in Gerry Johnstone and Daniel W Van Ness (eds), Handbook of Restorative Justice (Routledge, 2011) 213.

[31] King (n 23) 1105.

[32] David Moore, Lubica Forsythe and Terry O’Connell, ‘A New Approach to Juvenile Justice: An Evaluation of Family Conferencing in Wagga Wagga’ (Report, Centre for Rural Social Research, Charles Sturt University, 1995) 10.

[33] Young Offenders Act 1997 (NSW) pt 5.

[34] Criminal Procedure Regulation 2017 (NSW) pt 7. For an overview, see Elena Marchetti and Kathleen Daly, ‘Indigenous Sentencing Courts: Towards a Theoretical and Jurisprudential Model’ [2007] SydLawRw 17; (2007) 29(3) Sydney Law Review 415.

[35] For an overview see Kate Milner, ‘Restorative Justice and Adult Offending: Twelve Years of Post-Sentence Practice’ in Jane Bolitho, Jasmine Bruce and Gail Mason (eds), Restorative Justice: Adults and Emerging Practice (Institute of Criminology Press, 2012) 80.

[36] See, for example, the work of John McDonald at ProActive ReSolutions: ProActive ReSolutions (Web Page, 2021) <http://proactive-resolutions.com> . For the use of restorative justice in a prison workplace for dealing with staff interactions, see Kay Pranis, ‘Healing and Accountability in the Criminal Justice System: Applying Restorative Justice Processes in the Workplace’ (2007) 8 (Spring) Cardozo Journal of Conflict Resolution 659.

[37] See, eg, the work of Maurizio Vespa: Maurizio Vespa: Education Consultant in Restorative Practices and Leadership (Web Page) <http://mauriziovespa.com> Brenda Morrison, Peta Blood and Margaret Thorsborne, ‘Practicing Restorative Justice in School Communities: The Challenge of Cultural Change’ (2005) 5(4) Public Organization Review: A Global Journal 335; Eliza Ahmed and Valerie Braithwaite, ‘Learning to Manage Shame in School Bullying: Lessons for Restorative Justice Interventions’ (2012) 20(1) Critical Criminology 79.

[38] Colette Langos and Rick Sarre, ‘Responding to Cyberbullying: The Case for Family Conferencing’ [2015] DeakinLawRw 11; (2015) 20(2) Deakin Law Review 299.

[39] Zehr, Changing Lenses: Restorative Justice for Our Times (n 23) 37.

[40] Ibid 46–7; Zehr, The Little Book of Restorative Justice (n 22) 24–5.

[41] For further exploration of the notion of restorative justice arising as a reaction to the deficiencies of the criminal justice system, see Kelly Richards, ‘A Promise and a Possibility: The Limitations of the Traditional Criminal Justice System as an Explanation for the Emergence of Restorative Justice’ (2014) 2(2) Restorative Justice: An International Journal 124. The author, at 124:

seeks to destabilise the truth claim that restorative justice emerged in response to the failing of the criminal justice system. While the shortcomings of the traditional criminal justice system may provide a backdrop to the emergence of restorative justice, this article argues that such a possibility makes restorative justice a possibility rather than an inevitability.

[42] Al-Alosi and Hamilton (n 5) 1465.

[43] It should be noted that the illustration is just a summary of the usual process in a back-end model of restorative justice in the environmental offending context; it does not purport to capture the full complexities of the court process and the nuances of procedural differences across jurisdictions.

[44] Land and Environment Court of New South Wales, Practice Note: Class 5 Proceedings, 10 December 2020, paras 10, 12.

[45] This is the threshold that applies to criminal prosecution and can be contrasted with the ‘balance of probability’ threshold applicable to civil proceedings. Offenders are considered innocent until such time they plead guilty or are found guilty by the court: Woolmington v DPP [1935] AC 462.

[46] Land and Environment Court of New South Wales, Practice Note: Class 5 Proceedings, 10 December 2020, para 36(e).

[47] Ibid para 28.

[48] [2007] NSWLEC 96; (2007) 151 LGERA 92, 100 [40] (Preston CJ).

[49] Sentencing Act 2002 (NZ); Victims’ Rights Act 2002 (NZ).

[50] Victims’ Rights Act 2002 (NZ) s 9 states that ‘if a victim requests to meet with the offender to resolve issues relating to the offence’ and the necessary resources are available, a ‘member of court staff, a Police employee, or, if appropriate, a probation officer must ... refer the request to a suitable person who is available to arrange and facilitate a restorative justice meeting’.

[51] Sentencing Act 2002 (NZ) s 24A. ‘Suitable person’ is not defined in the Act.

[52] It is not always the case that the regulatory authority will attend the restorative justice process. In New Zealand, Environment Canterbury (as prosecutor and regulatory authority) has attended conferencing whereas in NSW, the Office of Environment and Heritage was excluded from attending the conferencing in Williams [2007] NSWLEC 96; (2007) 151 LGERA 92 and Clarence Valley Council (2018) 236 LGERA 291. Arguably, a prosecutorial/regulatory authority should not participate in a conference because it may try to influence the outcome of the conference and the conference should be the domain of the offender and the victim. Conversely, an authority may be able to provide expertise, guidance, and advice that can help the offender and the victim in reaching a resolution.

[53] Criminal Procedure Act 1986 (NSW) s 247V, which applies to the criminal jurisdiction of the Land and Environment Court of New South Wales pursuant to the Land and Environment Court Act 1979 (NSW) s 41.

[54] Sentencing Act 2002 (NZ) s 24A.

[55] Williams [2007] NSWLEC 96; (2007) 151 LGERA 92, 105 [64] (Preston CJ); Clarence Valley Council (2018) 236 LGERA 291, 301 [23] (Preston CJ). However, in New Zealand, it is mandatory for a sentencing judge to consider the outcomes of restorative justice processes: Sentencing Act 2002 (NZ) s 8(j).

[56] Al-Alosi and Hamilton (n 5).

[57] Mark Hamilton, ‘Restorative Justice Intervention in an Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Protection Context: Chief Executive, Office of Environment and Heritage v Clarence Valley Council’ (2019) 36(3) Environmental and Planning Law Journal 197, 207.

[58] Ibid.

[59] UNODC, ‘Handbook 1st ed’ (n 6) 8.

[60] Ibid 11.

[61] Ibid 10.

[62] Nicholas Tavuchis, Mea Culpa: A Sociology of Apology and Reconciliation (Stanford University Press, 1991) 23.

[63] An apology was made in the conferences held in these cases: Auckland Regional Council v Times Media Ltd (Auckland District Court, McElrea DCJ, 16 June 2003), discussed in Fisher and Verry (n 17) 57; Waikato Regional Council v Matamata-Piako District Council (Morrinsville District Court, Thompson DCJ, 6 May 2005), discussed in Ministry for the Environment (NZ), ‘A Study into the Use of Prosecutions under the Resource Management Act 1991: 1 July 2001 – 30 April 2005’ (Report, February 2006) 24 (‘Ministry for the Environment Report July 2001 – April 2005’); Waikato Regional Council v Hamilton City Council (Hamilton District Court, Whiting DCJ, 1 March 2005), discussed in ‘Ministry for the Environment Report July 2001 – April 2005’ (n 63) 24; Auckland City Council v L&L’s Co (Auckland District Court, McElrea DCJ, 11 April 2005), discussed in ‘Ministry for the Environment Report July 2001 – April 2005’ 25; Auckland City Council v 12 Carlton Gore Road Ltd (Auckland District Court, McElrea DCJ, 11 April 2005), discussed in Fisher and Verry (n 17) 58–9; Auckland City Council v Shaw [2006] DCR 425, [18] (McElrea DCJ) (‘Shaw’); Williams [2007] NSWLEC 96; (2007) 151 LGERA 92, 104 [59] (Preston CJ); Bay of Plenty Regional Council v Thomas (Tauranga District Court, Smith DCJ, 16 March 2010) [10]; Southland Regional Council v Taha Asia Pacific Ltd [2015] NZDC 18010, [24] (Dwyer DCJ); Bay of Plenty Regional Prosecutor v Withington [2018] NZDC 1800, [37] (Harland DCJ); Clarence Valley Council (2018) 236 LGERA 291, 299 [20] (Preston CJ).

[64] Hershey H Friedman, ‘The Power of Remorse and Apology’ (2006) 7(1) Journal of College and Character 1, 1.

[65] Meredith Rossner, ‘Restorative Justice, Anger, and the Transformative Energy of Forgiveness’ (2019) 2(3) The International Journal of Restorative Justice 368, 379.

[66] Mark Hamilton, ‘Restorative Justice Intervention in an Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Protection Context: Conspicuous Absences?’ (2014) 31(5) Environmental and Planning Law Journal 352, 361.

[67] John Braithwaite, Restorative Justice and Responsive Regulation (Oxford University Press, 2002) 15.

[68] UNODC, ‘Handbook 1st ed’ (n 6) 11.

[69] Some examples of tailored outcomes include donations to various organisations (such as community organisations and schools) to fund projects aimed at better protecting the environment: Auckland Regional Council v Times Media Ltd (Auckland District Court, McElrea DCJ, 16 June 2003), discussed in Fisher and Verry (n 17) 57; remediation of a damaged site: Northland Regional Council v Fulton Hogan Ltd (Whangarei District Court, Newhook DCJ, 6 May 2010), discussed in Ministry for the Environment (NZ), ‘A Study into the Use of Prosecutions under the Resource Management Act 1991: 1 July 2008 – 30 September 2012’ (Report, October 2013) 63; provision of an odour entrapment device and other associated work including the construction of a planted barrier around part of the offending site: Auckland Regional Council v Times Media Ltd (Auckland District Court, McElrea DCJ, 16 June 2003), discussed in Fisher and Verry (n 17) 57; construction of a bund around the offending site: Waikato Regional Council v Taharoa Mining Investments Ltd [2018] NZDC 24843, [101] (Harland DCJ); the installation of a new effluent system: Waikato Regional Council v PIC New Zealand Ltd (Auckland District Court, McElrea DCJ, 29 November 2004), discussed in Fisher and Verry (n 17) 58; remediation of septic tanks: Waikato Regional Council v Matamata-Piako District Council (Morrinsville District Court, Thompson DCJ, 6 May 2005), discussed in ‘Ministry for the Environment Report July 2001 – April 2005’ (n 63) 24; installation of fly screens on neighbouring properties: Waikato Regional Council v Hamilton City Council (Hamilton District Court, Whiting DCJ, 1 March 2005), discussed in ‘Ministry for the Environment Report July 2001 – April 2005’ (n 63) 24; landscaping work: Auckland City Council v L&L’s Co (Auckland District Court, McElrea DCJ, 11 April 2005), discussed in ‘Ministry for the Environment Report July 2001 – April 2005’ (n 63) 25; Auckland City Council v 12 Carlton Gore Road Ltd (Auckland District Court, McElrea DCJ, 11 April 2005), discussed in Fisher and Verry (n 17) 59; replacement of removed tree(s): Auckland City Council v Toa [2015] NZDC 20678, [3] (Harland DCJ); Auckland Council v Andrews Housemovers Ltd [2016] NZDC 780, [10] (Harland DCJ); planting of a tree to replace a tree that was cut down and the payment of an arborist to maintain the tree for five years: Shaw [2006] DCR 425, [76] (McElrea DCJ); establishment of an eco-nursery: Northland Regional Council v Fulton Hogan Ltd (Whangarei District Court, Newhook DCJ, 6 May 2010), discussed in Ministry for the Environment (NZ), ‘A Study into the Use of Prosecutions under the Resource Management Act 1991: 1 July 2008 – 30 September 2012’ (Report, October 2013) 63; planting of native trees in conjunction with a planting plan the offender will develop with the council: Bay of Plenty Regional Prosecutor v Withington [2018] NZDC 1800, [37] (Harland DCJ); and, a scar tree restoration project: Clarence Valley Council (2018) 236 LGERA 291, 299 [19] (Preston CJ).

[70] For an overview see, Mark Hamilton, ‘Restorative Justice Intervention in an Environmental and Planning Law Context: Applicability to Civil Enforcement Proceedings’ (2016) 33(5) Environmental and Planning Law Journal 487. See also Hamilton, ‘Restorative Justice Intervention in an Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Protection Context: Conspicuous Absences?’ (n 66) 203–4. One example applicable to the sentencing of pollution offending is a ‘restorative justice activity’ order: Protection of the Environment Operations Act 1997 (NSW) s 250(1A). Smith and Bateman give as an example of such activity the provision of ‘community facilities in a local park, or swimming facilities near a local river that has been affected by pollution’: Claire Smith and Brendan Bateman, ‘Expanded Powers and Tougher Penalties for Environmental Offences in NSW’, Clayton Utz Knowledge (Web Page, 12 June 2014) <https://www.claytonutz.com/knowledge/2014/june/expanded-powers-and-tougher-penalties-for-environmental-offences-in-nsw>. For an overview of such orders, see Mark Hamilton, ‘“Restorative Justice Activity” Orders: Furthering Restorative Justice Intervention in an Environmental and Planning Law Context?’ (2015) 32(6) Environmental and Planning Law Journal 548.

[71] Al-Alosi and Hamilton (n 5) 1479–80.

[72] National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 (NSW) s 90(1), as at April 2003 (the date at which the offences were committed).

[73] [2015] NZDC 3323 (Borthwick DCJ) (‘Interflow’).

[74] Ibid [42], [46].

[75] United Nations, Basic Principles on the Use of Restorative Justice Programmes in Criminal Matters (n 20) in UNODC, ‘Handbook 1st ed’ (n 6) 33–4.

[76] United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund, ‘Restorative Justice’, Toolkit on Diversion and Alternatives to Detention (Web Page) <https://www.unicef.org/tdad/index_56040.html>.

[77] Following a restorative justice conference and when the judge is sentencing an offender, they should be cognisant of the fact that some outcomes made at conferencing are not possible to be made into a court order (for example, a commitment for the offender to work with the victims in the future). Therefore, such commitments cannot be enforced by the court.

[78] (2018) 236 LGERA 291 (Preston CJ).

[79] Chris Fowler, ‘Environmental Prosecution and Restorative Justice’ (Summary, Adderley Head, May 2016) 3.

[80] For an overview of the preparation needed for conferencing, see Williams [2007] NSWLEC 96; (2007) 151 LGERA 92, 103 [56]–[57] (Preston CJ) and Clarence Valley Council (2018) 236 LGERA 291, 298 [14] (Preston CJ).

[81] $11,000 in Williams [2007] NSWLEC 96; (2007) 151 LGERA 92, 102 [53] (Preston CJ); $13,000 in Clarence Valley Council (2018) 236 LGERA 291, 313 [85] (Preston CJ).

[82] UNODC, ‘Handbook 1st ed’ (n 6) 8.

[83] Indeed, the guiding principle of the Restorative Justice Unit within Corrective Services NSW is ‘to do no harm’: see Bolitho (n 15) 272.

[84] UNODC, ‘Handbook 1st ed’ (n 6) 9–11.

[85] Ibid 8.

[86] Re-victimisation is the way a restorative justice conference can harm a victim. As an example, such harm may come from an offender dismissing or trivialising the effect offending has had on the victim. It is an adaptation from the concept of double victimisation, ‘[t]he way in which the state’s response to victimisation can add further burdens to the victim; for instance, rape victims may be doubly victimised because of the way in which courtroom processes put women “on trial” by suggesting they invited the incident in some way’: Rob White, Santina Perrone and Loene Howes, Crime, Criminality and Criminal Justice (Oxford University Press, 3rd ed, 2019) 88.

[87] UNODC, ‘Handbook 1st ed’ (n 6) 8.

[88] In Environment Protection Authority v Warwick Ronald McInnes [2020] NSWLEC 37 (Duggan J), the defendant was a volunteer of a sporting association and assisted with maintaining the club’s sports ground. The defendant mixed pesticide in a ‘Coke’ soft drink bottle and stored it under the sink within a disabled toilet. A 22-year-old autistic man, who is non-verbal and severely developmentally delayed, was attending the grounds with the group ‘Life Without Barriers’ and was given access to the disabled toilets. He found the Coke bottle and assuming it to be Coke consumed some of its contents. He vomited and was taken to hospital. He suffered mouth and gastrointestinal ulceration, nausea, diarrhoea, and acute kidney injury from consuming the pesticide. In Environment Protection Authority v Hardman Chemicals Pty Ltd [2020] NSWLEC 8 (Robson J) (‘Hardman Chemicals’), employees of the offending company, and employees of neighbouring businesses, became ill because of an air pollution incident. Symptoms included breathing difficulties, burning in the nose and throat, irritation to the eyes, choking, coughing and dry retching.

[89] For example, the Aboriginal communities in Williams [2007] NSWLEC 96; (2007) 151 LGERA 92 (Preston CJ) and Clarence Valley Council (2018) 236 LGERA 291 (Preston CJ).