University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

THE POLITICAL EXEMPTION: A JUSTIFIABLE INVASION OF PRIVACY IN THE POLITICAL SPHERE?

TEGAN COHEN[1]*

This article argues that the ‘political exemptions’ in the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth) pose a threat not only to privacy, but to core democratic values, and are therefore unjustifiable. While the threat to privacy imposed by the exemptions has grown more intense in recent years as new technologies usher in increasingly covert and data-intensive techniques for electioneering, proposals to change the law have gained little traction in Parliament. Instead, supporters of the exemptions maintain that the provisions support the proper functioning of the Australian democratic system. This article examines the operation of the exemptions under contemporary conditions, mapping the coverage of the provisions against the current technological and political milieu, in order to evaluate the effects of the exemptions on democratic processes. The analysis reveals that not only do the exemptions expose voters to a greater threat of privacy invasion, they threaten key democratic values which underpin the Australian political system.

As voters lined up at the polls to cast a ballot in the 2001 federal election, the window for candidates to persuade the undecided among them had firmly closed. The temporary moratorium on television and radio political advertising had commenced a few days earlier. There was no ‘Twitterverse’ in which to tweet, no Facebook feed to scroll, no smartphone with which to enter ‘cyberspace’. Google was in its infancy. Voters from the 35% of households connected to the internet[1] would have needed to go home to update their LiveJournals or log on to MSN Messenger. In any case, the majority of voters had followed the election on analogue TV, radio and in newspapers, rather than the internet.[2] Radio, print, mail-outs and especially TV were the primary conduits for campaign advertising, and relatively few people had been singled out for targeted communications.

A month after the 2001 election, a suite of amendments to the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth)[3] extending the legislation to private sector organisations came into effect.[4] Importantly, the amendments contained broad exemptions for registered political parties and the electoral and political activities of certain other actors.[5] It would have been difficult for the architects of the legislation to imagine what the political campaigning landscape would look like in 20 years. By the time of the 2019 federal election, around 86% of Australian households were connected to the internet.[6] Australians were among the most active social media users in the world.[7] More people followed the election on the internet than on TV, radio or newspapers.[8] Undecided electors queuing to vote could not only peruse the candidates’ websites, but also their Facebook, Instagram and Twitter profiles, and in some cases bespoke apps. Targeted political ads popped up frequently on digital platforms, search engine results, and even the puzzle application Jewels Fantasy.[9] The blackout period for TV and radio political advertising commenced as usual, but the ‘election silence’ was pierced by advertisements on social media and television streaming platforms, which ran all the way up to polling day.

Tectonic shifts in the technology and communications landscape over the last two decades have altered the flows of political communications and expanded the ways in which data about voters can be harnessed by political campaigns, giving rise to novel and heightened threats to the privacy of voters. The challenges posed by data-intensive practices such as predictive modelling and micro-targeting were recently brought to the fore by the Cambridge Analytica revelations, which provoked widespread governmental and regulatory inquiries around the world. In Australia, reports on the use of data mining software in a South Australian election, the United Australia Party’s unsolicited mass texting during the 2019 federal campaign and a foreign state-sponsored attack on Parliament House servers,[10] underlined the gap in the privacy law framework created by the political exemptions. Concerns about the inadequacy of privacy protections in the political sphere have prompted various public figures and bodies to call for repeal of the exemptions.[11] To date, the two major political parties have resisted, citing concerns about the impact on freedom of political communication, and consequently, the democratic process.[12]

The new threats posed by current and emerging data-intensive political campaigning warrant an urgent re-examination of the operation, effects and justifiability of the political exemptions. The exemptions have thus far received limited attention in the legal academic literature. Following its wideranging inquiry into the Privacy Act, the Australian Law Reform Commission (‘ALRC’) recommended the revision or removal of the political exemptions, subject to constitutional constraints.[13] More recently, Paterson and Witzleb compellingly argued that removing the exemptions is highly unlikely to conflict with the implied freedom of political communication in the Constitution,[14] thus effectively rebutting a key justification for the provisions.[15]

This article builds upon previous critiques of the political exemptions by arguing that the law poses a threat to privacy and democratic values, which render it unjustifiable. The article examines the operation of the political exemptions under contemporary conditions and concludes that the exemptions pose a threat not only to voter privacy, but to political equality, the quality of democratic discourse and informed electoral choice. Therefore, in this case the removal of privacy protections is deleterious to the overarching democratic interests the exemptions purportedly serve.

The analysis begins in Part II with a brief overview of the political exemptions and associated justification. In Part III, I outline the key dynamics and shifts in the technological and communication environment which have prompted renewed concerns about the exemptions, setting the scene for the analysis in Part IV of the current operation and effect of the provisions. Based on the analysis, I argue that the exemptions pose a real threat to democratic values of core significance to the Australian system of representative government. In Part V, I conclude by setting out some considerations for law reform in this area.

But for the political exemptions, the privacy implications of data-driven political campaigning would be regulated by the Privacy Act.[16] The Privacy Act governs the collection, use, storage, disclosure and other handling of ‘personal information’[17] by the private sector and federal government agencies. The Privacy Act contains a set of substantive and procedural restrictions (the ‘Australian Privacy Principles’ or ‘APPs’) which are designed to endow individuals with a measure of control over the handling of their personal information. The APPs are targeted at balancing individual privacy and the interests which inhere in the free flow of information.[18] Imbued with this notion of ‘balance’, the APPs are not absolute rights and restrictions, but rather open-textured[19] and subject to extensive exceptions, such as the political exemptions.

The political exemptions apply to four beneficiaries, who are afforded different levels of immunity under the provisions. The four beneficiaries of the exemptions are:

• Registered political parties,[20] which are granted the broadest immunity, in the form of a total exemption from the Privacy Act.[21]

• Political representatives, that is, current members of local councils and current members of state and federal Parliaments. The exemption for political representatives applies to acts or practices ‘engaged in, for any purpose in connection with’ an election,[22] referendum,[23] or ‘participation by the political representative in another aspect of the political process’.[24]

• Contractors of registered political parties and political representatives (and their subcontractors). Contractors and subcontractors are granted an exemption for acts or practices engaged in under a contract with a registered political party or representative for any purpose in connection with an election, referendum, or ‘participation in another aspect of the political process by the registered political party or political representative’.[25]

• Volunteers for registered political parties (but not political representatives). Volunteers are granted an exemption in respect of acts or practices engaged in ‘voluntarily ... for or on behalf of a registered political party and with the authority of the party’ for the aforementioned purposes.[26]

By excluding these actors and activities from the scope of the Privacy Act, the exemptions erode the ability of individuals to exercise a measure of control over their personal information and permit certain political activities to be conducted in a manner inconsistent with the standards established by the APPs. More specifically, the political exemptions reduce transparency by removing obligations on the beneficiaries to provide privacy policies and notices to individuals when their personal information is collected.[27] The exemptions remove various constraints on information handling, such as limitations on the use and disclosure of personal information for secondary purposes,[28] obligations to obtain consent to collect and use ‘sensitive information’,[29] and restrictions on direct marketing, including mandatory opt-out mechanisms.[30] The exemptions deprive voters of procedural rights to obtain access to records of their personal information held by beneficiaries, and to seek correction of those records.[31] Beneficiaries are also excused from complying with data quality and security standards with respect to personal information covered by the exemption.[32] Furthermore, the exemptions take the exempt acts and practices outside the scope of regulatory oversight provided for in the Privacy Act. In sum, the exemptions effectively expose individuals to a greater threat of privacy invasion in the context of electoral and other political processes. As explored below, this threat has been exacerbated by significant developments in data-driven political campaigning practices since the inception of the exemptions.

There are of course circumstances in which a threat to privacy, such as that created by the political exemptions, is tolerable, even necessary. Privacy, either as a legal right or normative value, does not transcend all other interests, rights and values in the Australian legal system. A privacy claim or interest may be overridden by constitutional restrictions. As noted earlier, Paterson and Witzleb recently considered the question of whether the implied freedom of political communication precludes removal of the political exemptions. The authors convincingly concluded that, in light of recent case law, subjecting political parties and representatives to the Privacy Act in its current form is highly unlikely to rise to the level of an unconstitutional burden on the implied freedom.[33] Accordingly, there is no need to engage with the question of constitutionality in this article. Proceeding on the basis that the exemptions are not constitutionally required, the question then becomes whether the privacy threat created by the law is justified by a legitimate interest.

What, then, is the legitimate interest served by the exemptions? The two major political parties have consistently maintained the policy position that the political exemptions are necessary to facilitate political communication and support the democratic process.[34] It is true that the ability of candidates and political parties to communicate their policies, views and fitness for office to the voting public is critical to the democratic process. Further, the ability of parties and representatives to assess popular support for policies, and to develop policies which reflect views and values held by the electorate is integral to the proper functioning of representative government. That political parties and representatives require some access to information about voters in order to perform these functions is incontrovertible. It is in this regard that individual rights to exercise control over personal information may come into conflict with the collectivised nature of democratic decision-making. However, extending the APPs would do little to interfere with the fundamental ability of political parties and representatives to gather information about, and communicate with, the voting public.[35] If the political exemptions were removed, political parties and representatives could still collect personal information about voters ‘in an open and transparent way’.[36] Political parties could still store vast amounts of voter information while complying with their obligation to take reasonable steps to prevent misuse and unauthorised access.[37] Political representatives could still collect voter information for one purpose and use it for a related secondary purpose within reasonable expectations.[38]

The area in which the APPs would likely have an impact is the adoption of certain data-intensive campaigning practices. For instance, political parties and representatives could be prevented from tailoring and targeting communications on ‘sensitive’ grounds by the obligation in APP 3.3 to procure consent before collecting ‘sensitive information’.[39] Complying with such requirements in relation to certain categories of ‘sensitive information’, namely political opinions or philosophical beliefs, might be impractical or undesirable in some circumstances. Furthermore, political parties and representatives would be hindered in their ability to market to unwilling recipients directly, rather than through mass advertising, media coverage and public fora, by the requirements in APP 7 to allow individuals to opt-out of direct marketing.[40] However, while there is an argument that the APPs might inhibit the use of certain modes of direct and personalised communications, it does not necessarily follow that the exemptions provide an overall benefit to the democratic process. To assess whether the privacy threat imposed by the political exemptions is justifiable on democratic grounds, consideration must be given to their broader effect on democratic discourse and values.

The actual effect of the exemptions is largely contingent on the technological, media and political context in which they operate, in particular, the contemporary opportunities and capabilities for collecting, analysing and using personal information available to political campaigns. As this Part explores, that context has undergone significant changes over the last 20 years which have had an impact on the operation and effect of the political exemption.

Australian political parties have long collected, analysed and otherwise used voter data for campaigning purposes.[41] At the time the political exemptions were introduced, the most significant stride in data-driven campaigning practice had occurred in the late 1980s – early 1990s, when the major parties established electronic voter databases that became the backbone of their direct mail and door-to-door canvassing operations.[42] By contemporary standards, the initial methods for compiling and maintaining these databases seem anachronistic. Voter records were built on the basis of the electoral roll, cross-matched against the telephone directory, and supplemented with census and other data sourced from direct contact with voters.[43]

Since the inception of the political exemption, major shifts in the technological, media and political environment have significantly expanded data-driven campaigning capabilities. First, the quantity and availability of information about voters has grown exponentially. The proliferation of smart devices, together with the emergence of ubiquitous digital platforms, have contributed to an explosion of ‘big data’. ‘Politech’ platforms such as NationBuilder[44] and i360[45] automatically pull data from social media platforms and other online sources. Those without the resources to build bespoke databases are able to leverage a suite of commoditised micro-targeting tools offered by digital platforms such as Google and Facebook, built on the enormous data reserves held by those companies.

Second, the potential uses for this glut of data have been expanded by advancements in analytical capabilities, particularly with respect to modelling and micro-targeting. Political campaigners and consultants can use ‘algorithms and observed data to build statistical or machine learning models, in order to predict unobserved actions or preferences’.[46] These modelled characteristics and preferences may inform micro-targeting, which involves the compilation of finely grained voter profiles, narrow segmentation, and targeting of voters with tailored messages,[47] and in some cases, ‘testing, or empirically measuring how well messages perform against one another and using that information to drive content production and further targeting’.[48]

Third, the distribution channels for targeted political messages are at once proliferating and becoming increasingly integrated. Digital platforms, including social media networks, rival traditional broadcast, print and outdoor media (ie, billboards and placards) as the key distribution channels for political communications. Social media platforms provide advertisers with the ability to select their audience on the basis of near or real-time, individual-level data about users on the platform. ‘Addressable’ TV allows advertisers to target screens in specific households using set-top box viewing data, merged with demographic and other data obtained from third party sources.[49] Digital billboard displays can change based on the demographics of the nearby crowd and other contextual factors.[50] Political campaigns can also integrate and coordinate their outreach across multiple, once siloed channels using cross-device tracking to monitor an individual’s behaviour across numerous devices and re-target messages based on knowledge gained from previous interactions.[51]

Fourth, this interconnected, data-rich environment has provided fertile ground for the growth of a complex and dynamic political campaigning ecosystem. Traditional campaigners such as political parties, independent candidates, special interest and lobby groups, and governments have embraced new data-driven techniques to propagate their political messages. In recent years, we have seen the emergence of additional, non-traditional campaigners enabled and equipped by social networking technologies, such as ‘digital foot soldiers’[52] with loose affiliations to a cause or candidate, and ‘satellite campaigns’, ie, unofficial, sometimes ephemeral, organisations which operate outside the auspices of political parties, as new vehicles for political campaigning.[53] Another more sinister development has been the use of social media infrastructure by foreign state actors to conduct covert, data-driven election interference.[54] The activities of these entities are supported by a melange of service providers who collect, aggregate, mine and analyse voter data, and facilitate the distribution of political messages. As new technologies emerge, so too do new technicians and experts on how to apply them.[55] Specialists in data analytics and digital tools occupy an increasingly important role in political campaigns.[56]

Finally, while technological advancements have enhanced the ability of political campaigns to collect, analyse and harness information about voters, the rise of data-intensive practices is not a solely technologically-driven phenomenon. The shift toward hyper-personalisation, segmentation and targeting of political communication is also a response to social, cultural and political forces. In particular, the declining vote share of the major political parties in Australia[57] (and many other countries), and consequent electoral volatility, has meant that forming majorities and winning elections is increasingly an exercise in aggregating ‘marginal gains’.[58] Additionally, political parties are having to contend for voter attention in a more diverse, multiplicitous information environment. Against this backdrop, the incentives for political campaigners to find efficient methods for locating and tailoring messages to persuadable voters are undeniable.

Cheaper and easier access to data, enhanced analytical capabilities and electoral volatility have spurred political campaigners to embrace more data-intensive techniques for campaigning. While the scattergun approach of mass marketing across traditional channels has certainly not been supplanted in Australian elections, the collection and use of data to isolate and directly engage with voters has assumed an important role in contemporary political campaigning.

Although the conditions under which political campaigns are conducted have shifted over the past 20 years, the terms of the political exemptions have remained the same. That said, the actual operation and effect of the exemptions has been altered by the emergence of new actors and the expansion of data-driven capabilities. In this Part, I examine the operation of the political exemptions under contemporary conditions and argue that, in effect, the provisions undermine certain democratic values.

In order to understand the operation of the political exemptions, it is necessary to identify not only which actors and practices are covered by the exemptions, but also those parts of the political campaigning ecosystem which are not. Given the pace of change in political campaigning practice, there is a risk that any attempt to exhaustively delineate the empirical cases which fall in and outside of the exemptions would quickly become obsolete. To avoid this problem, I adopt a typological approach to describe the dynamic data campaigning ecosystem, which provides a framework for systematically mapping the coverage of the political exemptions.

The typology draws out a distinction implicitly recognised in the political exemptions – that is, between political campaigners and service providers. The former encompasses actors who participate in data-driven political campaigning in order to influence the outcome of a democratic process, or further a policy agenda or issue, while the latter covers actors whose involvement is contingent upon being engaged by a political campaigner to provide goods or professional services. A further distinction is drawn between political campaigners based on their function or role in the democratic process, such as to run for elected office, or to promote another interest, issue, candidate or party. The final distinction, again drawn between political campaigners, is between domestic and foreign actors.

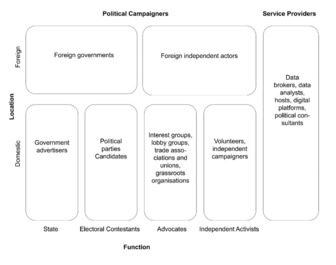

Cross-tabulated, these variables produce seven broad types, illustrated in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Typology of actors involved in data-driven political campaigning

Before proceeding with the analysis, it is worth clarifying that the classifications are conceptual types developed for the purpose of legal analysis, rather than empirical taxa. The purpose of the classification system is to reduce the complex and dynamic political campaigning ecosystem into enduring ‘types’ which can be analysed against the categories created by the political exemptions. Thus, just as empirical entities may fall within multiple categories in the political exemptions,[59] empirical entities may fall within multiple categories in the typology. Take Google as an example, which provides advertisers with targeting, testing and analytics tools, and an advertising platform in its capacity as a service provider. Recently, Google has used pop-up windows and warning alerts on its search engine page to campaign against a new law proposed by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission[60] – an activity which is clearly undertaken in its capacity as a political campaigner (specifically, an advocate).

The core beneficiaries of the political exemptions are a subset of electoral contestants, namely ‘registered political parties’ and ‘political representatives’.[61] The exemptions extend to other actors based on their relationship with one of these core beneficiaries. Specifically, an individual or entity will be eligible for an exemption if they act voluntarily ‘for or on behalf of’ and ‘with the authority of’ a registered political party (a ‘volunteer’),[62] or if they hold a contract with a political representative or registered political party, or a contract with one of their direct contractors (a ‘contractor’).[63] As discussed in the next section, while registered political parties benefit from a total exclusion from the Privacy Act, political representatives, eligible volunteers and contractors are given a somewhat narrower exemption, which is limited to acts and practices performed in connection with certain purposes.

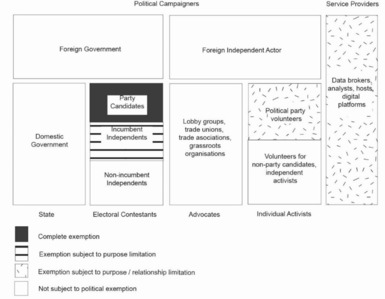

The coverage of the political exemptions is illustrated in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2: Coverage of the political exemption

The exemptions apply unevenly across the political campaigning ecosystem. Large sections of the ecosystem do not benefit from the exclusion. Non-incumbent independent candidates, advocates, non-party affiliated individual activists, domestic governments, foreign governments and foreign independent actors, as well as service providers for any of those entities, are not eligible to be covered by the exemptions. However, before drawing conclusions about the effects of this uneven coverage, it is necessary to consider the operation of the exemptions in the context of the Privacy Act as a whole, in particular, alongside the other exemptions in the legislation.

There are other exclusions in the Privacy Act which remove sections of the political campaigning ecosystem from the purview of the legislation. The small business exemption provides that an individual, body corporate, partnership, unincorporated association or trust that collects, uses or discloses personal information is not required to comply with the Privacy Act if:

• they ‘carry on a business’ which has had an annual turnover of AUD3 million or less; and

• where that business buys or sells personal information,[64] it does so with the consent of affected individuals.[65]

Some service providers may benefit from this exemption; though, it is likely that many of those with significant, data-intensive businesses will fail to meet the conditions vis-a-vis turnover and consent. Certain advocates may also qualify for the small business exemption where their activities amount to ‘carrying on a business’. The concept has been interpreted by the courts to ‘generally involve conducting some form of commercial enterprise, systematically and regularly with a view to profit’.[66] Whilst the requirement for profit-seeking would seem to exclude the activities of not-for-profit advocates, a profit motive is generally viewed as an indicative rather than determinative factor; a point emphasised by the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (‘OAIC’), which clarified that ‘a necessary modification of the concept in the context of the Privacy Act is that the Act can apply to a non-profit entity’.[67] The political campaigning activities of non-profit advocates could therefore constitute ‘carrying out a business’ if they bear the requisite characteristics of commerciality and regularity. However, many advocates established for the purpose of influencing public debate are unlikely to meet these criteria. Although in competition law cases Australian courts have found that political and commercial conduct are not mutually exclusive,[68] it is also clear from the jurisprudence that the mere act of an organisation engaging in political debate which affects its own interests will not in of itself be a ‘commercial act’.[69] In this vein, Finn J observed that

[i]n seeking, directly or indirectly, to contrive or influence outcomes by representations made in public debate, or in the processes of informing the public, [the respondent] was engaging in activities of a political, not of a commercial or trading, character. And this was not the less so because its activities were informed by a degree of self-interest.[70]

Thus, even advocates established to influence political debate and policy in favour of the commercial interests of their members, such as business lobby groups, are unlikely to be ‘carrying out a business’. In sum, advocates who engage solely in political rather than commercial activities, which will be the case for many, or whose activities are irregular or ephemeral, as is the case for ‘satellite campaigns’, will not qualify for the small business exemption, and therefore will be subject to the Privacy Act.

Inversely, some individual activists will be excluded from the operation of the Privacy Act by the exemptions for non-business activities. Specifically, there is an exemption for activities engaged in by an individual for ‘personal, household or family affairs’,[71] and activities undertaken outside ‘the course of a business carried on by the individual’.[72] Any data-driven campaigning activities undertaken by an individual activist will generally be non-commercial and often irregular, and therefore outside the scope of the Privacy Act. Importantly, the non-business exemption is only available to individuals, meaning the political campaigns of non-incumbent independents, which are typically unincorporated associations, are not subject to the exclusion.

The Privacy Act does not extend to foreign governments,[73] neither is it likely to capture foreign independent actors. The extraterritorial provisions of the Privacy Act extend to foreign individuals and entities which ‘carry on a business’ in Australia.[74] Given that ‘carrying on a business’ generally requires regular commercial activity, it seems unlikely that independent foreign entities intent on election interference will meet this criterion. As such, these entities will not come within the scope of the Privacy Act.

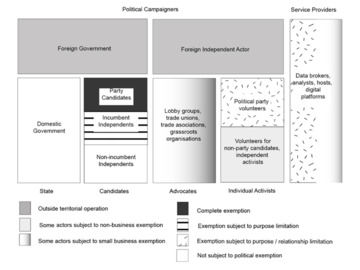

Taken together, the political and other exemptions operate to remove substantial sections of the political campaigning ecosystem from the scope of the Privacy Act, as illustrated in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3: Coverage of the political and other exemptions

As seen in the figure above, even when the other exemptions and exclusions are considered, the political exemptions still operate in a manner which confers an advantage on political parties and incumbent candidates relative to other members of the polity, namely non-incumbent independent candidates, certain ‘advocates’, ‘domestic governments’, and certain ‘service providers’ engaged by those entities. Thus, we can conclude that one effect of the uneven coverage of the political exemption is to provide political parties and incumbent candidates with a relative advantage in targeting and tailoring their political messages to the electorate.

The advantage for political parties and incumbent candidates created by the political exemptions raises questions about political equality and the level democratic playing field. Political equality is a contestable concept, but is used narrowly in this context to denote the equal opportunity of all members of the Australian polity to participate in the democratic process.[75] One aspect of this form of political equality is the ‘level democratic playing field’, which is threatened where incumbency is buttressed by disparate access to, inter alia, resources, media and the law, which in turn can insidiously erode or thwart democratic competition.[76] While the High Court has embraced political equality as a constitutional principle, there is some debate about whether political equality can be sourced in the Constitution.[77] However, its status as an important aspiration in the Australian political culture is relatively uncontroversial. Indeed, Australian federal and state Parliaments have on numerous occasions sought to legislatively shore up a ‘level playing field’ with limits on political donations and political advertising[78] on traditional media;[79] a testament to its status as a shared democratic value and aspiration (albeit one susceptible to competing visions for implementation).

In the contemporary technological and media environment, where data is an increasingly valuable resource for political campaigns, and dominant digital platforms are important channels for the distribution of political communications, disparate access to data resources and new media could undermine the levelness of the democratic playing field. Although, as discussed in Part II, the APPs do not prevent campaigners from gathering information about and communicating with the voting public, they do place some constraints on certain more data-intensive campaigning practices. Therefore, removing those constraints (by means of the political exemptions) does provide a practical advantage in the deployment of techniques like predictive modelling and micro-targeting. In a multiplicitous and crowded information environment, where elections are fought and won on the margins, providing a structural advantage for political parties and representatives to amplify their political communications to the electorate by way of granular tailoring and micro-targeting could threaten political equality.[80]

However, a formal disparity in access to resources and media between some political actors may be justifiable. Placing more stringent limitations on the data-driven political campaigning activities of domestic government actors is arguably necessary to prevent incumbent governments from using state agencies for partisan ends.[81] Restricting the data-driven political campaigning activities of foreign entities may be necessary to preserve election integrity and self-determination, specifically by enforcing the ‘membership rules for political decision-making, ie, the idea that only members of a polity should participate in elections’.[82] On that basis, the question that remains is whether there is a similarly compelling rationale to justify conferring political parties and incumbent candidates with an advantage relative to non-incumbent independents and advocates.

The High Court has previously rejected the notion that the Constitution privileges the political speech of candidates and parties relative to other members of the polity.[83] Recently, in Unions NSW v New South Wales,[84] a plurality of the Court observed that

[t]he requirement of ss 7 and 24 of the Constitution that the representatives be ‘directly chosen by the people’ in no way implies that a candidate in the political process occupies some privileged position in the competition to sway the people’s vote simply by reason of the fact that he or she seeks to be elected.[85]

Notwithstanding the absence of a constitutionally entrenched privilege, there may still be sound policy reasons for conferring a legislative advantage upon political representatives and parties with respect to their ability to communicate with the electorate. Elected representatives serve a critical role in a system of representative government where voting is the principal mode of democratic expression. Representatives have parliamentary duties and responsibilities to provide constituency services, which non-incumbent candidates and advocates do not hold. Political parties also perform a crucial role. As Orr put it, parties act as the main ‘gatekeepers for potential MPs’.[86] They also (among other things) aggregate viewpoints and generate policy.[87] Despite declining party membership and the rise of satellite and other non-traditional campaigners, political parties remain the primary vehicles through which collective political action, ideas and debate are organised and communicated in Australia.[88] As such, there is a significant public interest in facilitating the widespread dissemination of policy pronouncements by these entities. But does the significance of parties and representatives to Australian political life warrant the specific advantage conferred by the political exemptions?

I contend that this question should be answered in the negative. There is no reasonable imperative for granting registered parties and representatives the ability to tailor messages and target voters on sensitive grounds without consent, nor to ignore requests to opt-out of communications. Further, there does not seem to be a rational connection between the special roles and functions of these entities and an entitlement to (among other things) conduct their information handling activities non-transparently, collect all manner of ‘sensitive information’ about the voting public without consent, nor leave that information vulnerable to unauthorised access or malicious attacks. By operating in a manner which privileges the ability of political parties and representatives to tailor and micro-target messages to voters relative to non-incumbent independents and certain advocates, the political exemptions unjustifiably detract from a level democratic playing field.

A key question this raises is whether the appropriate antidote to the political inequality created by the exemptions is to extend its coverage. However, an extension would exacerbate the threats to privacy already imposed by the exemptions. Further, such an approach would not address democratic concerns. Due to an exceedingly broad scope, the exemptions shield contemporary data-intensive practices which have the potential to undermine civic discourse, including through discrimination in the supply of information to voters.

As noted earlier, registered political parties benefit from a total exclusion from the Privacy Act. Political representatives are exempt in respect of acts or practices engaged in:

• ‘for any purpose in connection with’ (the ‘nexus requirement’);

• an election, a referendum or ‘participation by the political representative in another aspect of the political process’ (collectively, the ‘permitted purposes’).[89]

The exemption for volunteers and contractors is limited in a similar manner. An act or practice undertaken by the volunteer or contractor must be for a purpose in connection with an election or referendum, or the participation of the representative or party (their client) in the political process, or facilitating acts or practices of their client for one of those reasons.[90] While prima facie narrower than the exemption afforded to political parties, the exemption for political representatives is still exceptionally broad.

The precise scope of the permitted purposes is subject to some ambiguity, but in any event, encompasses a broad range of matters. The permitted purposes clearly embrace political campaigning for elections and referendums. The third limb of the permitted purposes – participation by the political representative or political party (as the case may be) in another aspect of the political process – extends the exemption beyond these defined processes; though the boundaries of that extension are susceptible to multiple interpretations. It would seem to follow that ‘participation ... in another aspect of the political process’ relates to the performance by representatives or parties of their specific role in the political process. For political representatives, this role is as legislators and elected representatives of their constituents. In its report on the Bill, the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs (‘House Committee’) seemed to adopt this reasoning in its discussion of the rationale for the exemption, stating that

[i]n order for a Member of Parliament to ensure that he or she is properly addressing the concerns and interests of his or her constituents it is necessary to be able to collect information concerning the electorate and its constituents and the issues that are relevant to the life of that community.[91]

However, there is evidence in other extrinsic materials that the legislature intended to go further. When the House Committee suggested that the third permitted purpose be amended to refer to ‘participation in the parliamentary or electoral process’ rather than all ‘political processes’,[92] the Government rejected the recommendation on the basis that it ‘would have the probable effect of significantly narrowing the scope of the exemption’.[93] However, it did not go on to spell out what the suggested amendment would exclude, and what else it had intended to cover. Thus, the retention of the open-ended phrasing leaves some room for interpretation as to the scope of the permitted purposes. For present purposes, it is sufficient to note that the scope is broad, and at a minimum covers the activities undertaken by an incumbent candidate in the course of performing their role as an elected representative.

This broad casting of the permitted purposes has a number of implications. It means that an incumbent candidate is able to repurpose information collected in the course of one ‘political process’ for another permitted purpose under the auspices of the exemption. It follows that data collected by an incumbent candidate in the course of, for instance, fielding a constituent complaint or conducting a survey about the efficacy of community services, could later be used for election campaigning purposes. Importantly, there is no requirement for the purpose of a political campaigning act or practice to be ‘legitimate’ or consistent with the democratic objectives purportedly underpinning the exemption. For example, the exemption allows political representatives to disclose voter data to third parties for a commercial gain. In fact, the Government rejected a suggestion by the House Committee to clarify that the exemptions do not permit the sale of data to an entity not covered by the provisions,[94] leaving it open to representatives to sell voter profiles to say, a third-party campaigner or a media organisation reporting on an election. While the Commonwealth Electoral Act prohibits the sale of data obtained from the electoral roll, as the Australian Electoral Commission (‘AEC’) pointed out, there is a risk this restriction could be circumvented because ‘if the enrolment information provided by the AEC were to be repeatedly merged with personal information from other sources, there would come a point at which it might no longer be legally recognised as enrolment information ...’[95]

In the era of big data, the risk of the source of electoral data being obfuscated is compounded by advancements in data analytical processes, particularly enhanced capacities to link and integrate seemingly disparate datasets to derive new information.

If the political exemption were removed, such activities would be constrained to some extent by the transparency obligations and purposive limitations on use and disclosure in the APPs. More specifically, under APP 5 the political representative or party would be required to notify voters of their purpose for collecting the electoral data at the point of collection.[96] The subsequent sale of data collected for electoral purposes would be prohibited by APP 6, unless the representative or party first obtained consent from the affected voter, or the sale was related to the primary purpose of collection and reasonably expected by the voter, or another limited exception applied.[97]

The scope of the exemption is further widened by the weak nexus requirement. The provisions merely require that the act or practice be for a purpose ‘in connection with’ an election, referendum or participation in another political processes. The relational term ‘in connection with’ has been construed broadly by the courts, such that a range of information processing practices conducted by political representatives for a purpose with an indirect or attenuate relationship to a political process could be covered by the exemption.[98] For instance, the collection of constituent data by a political representative on a speculative basis, without a clear or planned use for a relevant political process, would seem to fall within the scope of the exemption. Big data analytics, which often involves deriving unanticipated insights from enormous datasets, provides a rationale for taking advantage of the weak nexus requirement, and amassing ostensibly irrelevant data about voters.

Again, the APPs would provide some limited privacy protection against such practices. Specifically, APP 3 requires organisations to refrain from collecting data which is not ‘reasonably necessary’ to perform its functions or activities.[99] APP 11.2 requires organisations to destroy or de-identify personal information superfluous to its needs.[100] While these data minimisation principles do not completely remedy the privacy issues arising from big data analytics, their application would go some way toward curbing the excesses of large-scale, indiscriminate data collection.

The broadly drawn scope of the political exemptions clearly has implications for voter privacy by reducing informational control. It also means that the political exemptions operate to shield practices which potentially reduce opportunities for collective deliberation and create opportunities for discrimination in the course of political campaigning.

In contrast to mass media communications, micro-targeted messages are essentially delivered to individuals in ‘private’ spaces. Micro-targeted messages disseminated over digital platforms are often called ‘dark posts’ because they are only visible to individuals who are part of the selected audience for the advertisement. Where a voter receives a micro-targeted message, their experience of the political message is more likely to be an individual rather than collective one. The voter’s views and understanding of the message are more likely to be shaped in the absence of alternative viewpoints and collective deliberation. Whereas the merits and truth of claims made in broadcasted advertisements are able to be scrutinised and evaluated through public discussion, micro-targeting leaves individual voters to parse the content of political communications in isolation. As Tufekci points out, the practice continues ‘a trend started by direct mail ...’ which runs counter ‘to the idea of a civic space functioning as a public, shared commons’.[101]

Micro-targeting, particularly on the basis of sensitive traits, may also be deployed for marginalising or discriminating against voters, such as through ‘political redlining’. The term ‘redlining’ was first used in the 1960s to describe the common practice by banks and other lenders of drawing red lines on maps around areas that would be denied financial services by default, often on the basis of race.[102] Political redlining, a term hatched by Howard, describes a similar process of discrimination whereby, rather than denying loans and other services to residents of certain neighbourhoods, politicians restrict the ‘future supply of political information with assumptions about our demographics and present or past opinions’.[103] Consider, for instance, a scenario where a political representative collects data about the racial and religious backgrounds of their constituents and uses that data to entirely ignore particular groups in their outreach and persuasion efforts. In this case, the political representative uses personal information, not to engage in political communication with electors, but to avoid it. Nevertheless, the initial collection of the data and subsequent use would be conducted for a purpose in connection with the representative’s participation in a political process and election, respectively, and would therefore be subject to the exemption. As noted earlier, there is no requirement for the purpose of an exempt act or practice to be legitimate.

While such practices have theoretically been possible under the political exemptions since their inception, the trends outlined in Part III have expanded opportunities for political campaigners to collect and harness voter data for such ends. Modelling allows political campaigns to infer sensitive traits about wider sections of the electorate. Micro-targeting allows political campaigns to deliberately and covertly target and avoid specific audiences with greater precision, and on a larger scale.[104] The dissemination of ‘dark posts’ reduces the likelihood of voters chancing upon a message not intended for them or someone like them.

While not a total panacea, the obligations in the APPs would provide some protection against discriminatory practices through transparency and consent mechanisms.[105] Under APP 3.3, a political campaign would be prohibited from collecting sensitive information about voters, such as racial or ethnic origin or religious beliefs, without their consent.[106] APP 5 would require that the campaign notify the voter of its purposes for collecting the data.[107] Under APP 7, a political campaign would also be prohibited from using sensitive information for direct marketing unless the voter provided consent.[108] Further, APP 12 would endow individuals with the right to access personal information about them held by the campaign,[109] which would help proactive voters deduce the grounds upon which they are being targeted or avoided. However, the political exemptions remove political parties and representatives from the scope of these obligations and provides a shield against scrutiny, rendering efforts to discriminate and marginalise certain voters from political discussions unlikely to be exposed to public examination and debate.

The lack of transparency surrounding these practices also undermines the capacity of voters to make informed electoral choices. The preservation of informed electoral choice is of core significance to the Australian democratic system. In Lange v Australian Broadcasting Corporation,[110] the High Court explained that the provisions of the Constitution which establish the system of representative and responsible government necessarily protect ‘that freedom of communication between the people concerning political or government matters which enables the people to exercise a free and informed choice as electors’.[111] As Dawson J observed in Theophanous,[112] ‘[J]ust what opportunity must be afforded to a voter for him or her to be sufficiently informed to cast a genuine vote may be a matter giving rise to differences of opinion’.[113] However, Kildea and Smith helpfully identified three relevant areas of voter knowledge: technical information about how to vote and the operation of the electoral system, ‘the basis for choosing between candidates’ and the role of the electoral process in the democratic system.[114] The political exemptions have the potential to adversely impact on the second area of knowledge, and new tools and techniques in data-driven political campaigning have exacerbated that risk.

Without visibility of the basis upon which a political communication has been targeted, a voter’s ability to autonomously engage with the communication is reduced. As Ward noted, where transparency is lacking, voters are deprived of ‘the freedom to make decisions based on reasons or to act after rationally considering all pertinent information’.[115]

A core aim of the Privacy Act and similar legislative regimes is to increase transparency with respect to organisational information handling practices.[116] As noted above, an organisation subject to the APPs is required to maintain a privacy policy and to notify an individual of certain matters at the point of data collection, including their identity, purpose of collection and any intentions to on-disclose the data.[117] Furthermore, organisations are generally required to provide individuals with access to personal information it holds about them upon request.[118] By excluding certain political actors from these transparency obligations, the political exemptions undermine the capacity for informed voter choice intrinsic to democratic processes.

The transparency deficit created by the political exemptions has been exacerbated by technological developments which have expanded the opportunities to conduct data-driven political campaigning activities covertly without the knowledge of voters. In situations where a campaigner collects data directly from a voter, the voter has intrinsic knowledge of the fact of the collection, and in some cases, an opportunity to restrict access to the data. In the contemporary environment, data collection activities which at one time required political campaigns and their personnel to interact with the voter have been rendered invisible by the developments discussed in Part III – passive and continuous data collection through ubiquitous surveillance technologies; algorithmically-driven message testing and tailoring; integrated delivery channels which monitor voter responses. Where these undetectable collection processes come within the scope of the exemption, voters are deprived of both intrinsic knowledge and Privacy Act mandated transparency notice.

Covert data collection is not the only trend expanding the transparency deficit in data-driven political campaigning. Big data has opened up possibilities for voter data to be processed in unexpected and unpredictable ways. Big data logics aim at uncovering hidden correlations and unanticipated insights, from enormous, seemingly disparate datasets.[119] Thus, even where voters are aware of the collection of their data, the use of big data analytics will make it difficult for them to predict the additional information that might be derived from that data, and the ultimate uses to which that data might be put.

It is also increasingly difficult for voters to trace the lifecycle of their data and the entities involved in processing it for political purposes. Where a political party or representative contracts with an organisation to collect data in connection with a political purpose, that contractor will benefit from the political exemption for contractors.[120] If that organisation procured data from other data suppliers, those suppliers may also benefit from the exemption as direct subcontractors.[121] In a scenario where a dataset is compiled from innumerable sources, one transaction could bring thousands of entities within the scope of the exemption. The circuitous, multilayered data sharing arrangements characteristic of the data brokerage industry[122] are in of themselves impenetrable to the average voter. The political exemptions worsen this transparency deficit by removing the obligation for data suppliers who qualify for the exemptions to be open with voters about their data sharing practices.

It is useful to illustrate the consequences of this transparency deficit with an example. Say, for instance, a childcare centre collects information from new parents for the primary purpose of providing childcare services. The act of collecting the data is subject to the Privacy Act, so the childcare centre is required to provide transparency notices to the parents at the time of collection. Now let us say that the childcare centre enters into a contract with a data firm, which itself has been engaged by a political party to gather voter data for political campaigning purposes. Under the contract, the childcare centre agrees to provide the firm with access to its database for the political party’s campaigning purposes. The use and disclosure of the new parent data by the childcare centre will fall within the scope of the political exemption, as the childcare centre will be a ‘direct subcontractor’ of the political party. Ordinarily under the Privacy Act, the childcare centre would need to either obtain consent from the parents or demonstrate that the secondary purpose is directly related to the primary purpose of collection and reasonably expected by the parents.[123] However, by virtue of the political exemptions, the organisation is instead permitted to use or disclose the data without the knowledge of the parents, and in a manner inconsistent with their expectations. Furthermore, the affected parents could then unknowingly be targeted by the political party with messages tailored using information obtained from the childcare centre and an array of other ‘direct subcontractors’.

Another problematic trend in data-driven political campaigning potentially obscured by the exemptions is the leveraging of covert paid or volunteer ‘influence’ networks to disseminate political messages. New digital infrastructure and the availability of encoded social graph information allow political campaigns to situate voters within relational and influence networks, which they can leverage for persuasion and mobilisation by proxy, or ‘network marketing’.[124] Kreiss neatly summed up this indirect or ‘two-step’[125] approach, explaining that

‘[o]n social media platforms, campaigns use data and analytics to identify their supporters, determine their influence, and track their engagement. Campaigns urge their supporters to share political content and make their personal appeals to their friends on these platforms’.[126]

Michael Bloomberg’s 2020 presidential campaign controversially deployed such tactics by commissioning ‘influencers’ on Instagram to create memes in support of the candidate.[127] Furthermore, social media infrastructure and the spread of commoditised ‘politech’ tools has facilitated what Gibson called a ‘more devolved or “citizen-initiated” approach to campaign organization ...’[128] For instance, the ‘My Nearest Marginal’ app developed by Momentum enabled activists to identify and coordinate canvassing activity in marginal seats.[129] Another app called ‘VoteWithMe’, developed for United States (‘US’) elections, matches a user’s contact list against voter rolls to reveal party registration, swing district residence and voting history.[130] Individuals are able to download and use the app to encourage their contacts to vote, all without the direction or even knowledge of the party or candidate they are seeking to assist.

A number of studies have shown that voting behaviour is strongly influenced by offline social networks.[131] Identifying ‘influencers’ within social networks can be an effective way for political campaigns to indirectly disseminate messages to voters through more ‘credible’ sources, whilst avoiding activating ‘persuasion knowledge’ (and potentially cynicism) among the voters.[132] The adverse consequences of such opaque practices can be seen in alleged voter suppression efforts, such as the ‘Do So’ campaign in Trinidad and Tobago, an ostensibly ‘grassroots’ meme engineered by political consultants and designed to inspire one section of the electorate to abstain from voting.[133]

As noted earlier, the exemptions extend to individuals who act voluntarily ‘for or on behalf of’ and ‘with the authority of’ a registered political party.[134] While ‘two-step’ persuasion and ‘devolved’ political campaigning tactics challenge traditional notions of the ‘volunteer’, unpaid members of these persuasion networks may still fall within the scope of the political exemption. Although the language of the exemption for volunteers echoes legal descriptions of fiduciary,[135] including agent-principal, relationships, it is doubtful that the legislative intention was to restrict this exemption to volunteers who act as ‘agents’.[136] However, the language clearly imports a more stringent qualifier than the mere performance of unpaid work voluntarily. It is likely that the acts of the volunteer must be performed in the volunteer’s capacity as a ‘representative’ of the party, and within the scope of the authority granted by the party,[137] in order to qualify for the exemption. Accepting this construction, an individual who downloads and uses the ‘VoteWithMe’ app of their own accord will not be covered. But what about those who comply with a request by a political party to utilise the app? Or Instagram influencers asked to post pro-candidate memes? Both are arguably acting for and with the authority of the party and therefore, such activities could come within the scope of the exemption and its accompanying shield against scrutiny.

The complexity and opacity of contemporary data collection, analytics, exchange and distribution networks poses a fundamental challenge to the ability of voters to properly understand the basis upon which a political communication has been targeted at them. This lack of understanding can impair the voter’s capacity to make informed electoral decisions on the grounds of data-driven political messages targeted at them. As many scholars have pointed out, the informational asymmetries created by big data processes are by no means cured by the current generation of data privacy laws, including the Privacy Act.[138] However, the problem is clearly exacerbated by the political exemption, which removes any requirement for beneficiaries to provide transparency in respect of data-driven political campaigning practices.

After reports emerged that Cambridge Analytica had accessed the data of more than 300,000 Australian residents as part of its extensive harvesting of Facebook profiles, the OAIC launched an investigation into the incident.[139] The investigation culminated in the regulator lodging proceedings against Facebook in the Federal Court for serious and repeated breaches of the Privacy Act.[140] The action followed two years of international reflection and reactions to the controversy, which saw the completion of a wideranging investigation by the United Kingdom Information Commissioner’s Office, a record fine imposed by the US Federal Trade Commission, policy changes on political advertising by Google, Twitter and Facebook,[141] and Cambridge Analytica file for bankruptcy. Against this backdrop, it is perhaps unsurprising that the OAIC took the rather exceptional step of bringing an action against Facebook for its role in what has been widely condemned as an egregious invasion of privacy. What may be surprising to some is that the OAIC would likely have been unable to take such action had the companies involved been engaged by an Australian political party or incumbent candidate to harvest, disclose and use the relevant user data.

Since the inception of the political exemption, transformative technological developments have ushered in a range of covert and data-intensive techniques for political campaigning. As a result, the shield created by the exemptions not only compromises voter privacy, but also poses a serious threat to democratic discourse, informed electoral choice and political equality. While various commentators have rightly called for the repeal of the exemptions, removing the political exemptions alone is unlikely to address the significant privacy and democratic challenges posed by current and emerging data-driven campaigning practices. The Privacy Act, as it pertains to private organisations, is largely an attempt to balance individual privacy against commercial and market interests, and was not designed to address the distinct issues which arise in the electoral context. Furthermore, simply removing the political exemptions without further amendment would likely lead to some unintended or undesirable consequences. For instance, as noted in Part II, political parties and representatives would be required to treat information about political opinions and affiliations according to the same stricter standards that apply to other ‘sensitive information’, such as criminal or health records – an impractical outcome in the electoral context.

A comprehensive reassessment of the concepts, mechanisms and assumptions which underpin the Australian privacy framework is required to ensure the law adequately addresses the privacy threats particular to the electoral context, while taking into account the benefits to the democratic process associated with the collection, use and disclosure of information about voters for political purposes. In 2020, the Commonwealth Attorney-General’s Department commenced a wideranging review of the Privacy Act.[142] The review, which is underway as at the time of writing, presents a fresh opportunity to examine the application of the Privacy Act to the electoral context.

A number of principles should guide such a review. First, any proposal for reform should be built on a nuanced appreciation of current and emerging data-driven practices, taking into account the specific legal, political and cultural institutions which shape the deployment of such practices and enabling technologies in Australia. As several authors have pointed out, the form that data-driven political campaigning takes may vary depending on jurisdictionally specific factors.[143] Second, options for law reform must take into account the information environment at large. Since the Cambridge Analytica-Facebook scandal, a great deal of attention has been directed to the risks of paid online advertising, particularly micro-targeting. However, the leveraging of data-driven techniques and the gaming of social networks to spread political messages ‘organically’ also raises a host of privacy and democratic concerns – issues which could be exacerbated by disproportionate or uneven regulation of other practices. Thus, the potential impact that placing restrictions on one type of practice will have on other forms of data-driven campaigning must be considered. Finally, it is common in policy debates for privacy to be framed as a fundamentally individual interest which needs to be balanced against competing public interests. This paradigm underpins the rationale for the political exemptions, which are framed as a necessary incursion on individual privacy to protect the overriding societal interests in a properly functioning democracy. However, as discussed in this article, incursions on voter privacy can involve adverse consequences for democratic values. The framing of privacy in purely individualistic terms disregards any role that privacy may play in serving broader public interests. It encourages the blunt subordination of privacy rights rather than considered attempts to protect the democratic interests supported by voter privacy. In designing new laws to meet the challenges to voter privacy posed in the big data era, it is therefore important for lawmakers to recognise the instrumental role of privacy in fostering and protecting democratic processes and values.

* PhD Candidate, QUT School of Law. This research is supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program (R[1]RTP’) Scholarship. The author is grateful to Associate Professor Mark Burdon and Professor Nicolas Suzor, as well as the three anonymous reviewers, for their helpful comments on earlier drafts on the article.

[1] Australian Bureau of Statistics, Patterns of Internet Access in Australia, 2006 (Catalogue No 8146.0.55.001, 29 November 2007).

[2] The Australian Election Study found that 26% of survey respondents followed the 2001 election on television, 16% followed newspaper reporting and 16% radio coverage. Only 2% of respondents followed the 2001 federal election on the internet (up from 1% during the previous federal election in 1998): Sarah M Cameron and Ian McAllister, ‘Trends in Australian Political Opinion: Results from the Australian Election Study 1987–2019’ (Report, Australian National University, December 2019) 8.

[3] Privacy Act 1988 (Cth).

[4] The amending act was the Privacy Amendment (Private Sector) Act 2000 (Cth). Before the amendment, the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth) was limited to federal government agencies, credit reporting bodies and credit providers, with globally applied rules regarding tax file numbers.

[5] Privacy Act 1988 (Cth) ss 6(1), 6C(1), 7C, 13(1).

[6] Australian Bureau of Statistics, Household Use of Information Technology, Australia, 2016–17 (Catalogue No 8146.0, 28 March 2018).

[7] David Cowling, ‘Social Media Statistics Australia: April 2019’, Social Media News (Blog Post, 1 May 2019) <https://www.socialmedianews.com.au/social-media-statistics-australia-april-2019/>.

[8] The Australian Election Study found that 26% of survey respondents followed the 2019 election on the internet, 22% followed on TV, 12% radio coverage and 11% newspapers. 2019 was the first time since 1969 that the survey revealed that more people had followed the election via a means other than TV: Cameron and McAllister (n 2).

[9] Ariel Bogle, ‘Clive Palmer's Ad Deluge Shows Google and Facebook Need to Step Up Transparency, Experts Say’, ABC News (online, 22 May 2019) <https://www.abc.net.au/news/science/2019-05-22/clive-palmer-election-advertising-google-facebook-transparency/11133596>.

[10] Ariel Bogle and Matthew Doran, ‘Clive Palmer's United Australia Party is Sending Voters Unsolicited Text Messages’, ABC News (online, 12 January 2019) <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-01-11/clive-palmer-united-australia-party-unsolicited-text-messages/10709106>; Katharine Murphy,‘Why the South Australian Election is the Nation's Most Gripping Contest’, The Guardian (online, 10 March 2018) <https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2018/mar/10/why-the-south-australian-election-is-the-nations-most-gripping-contest>; Jamie Smyth, ‘Australian Political Parties Hit by Cyber Attack’, Financial Times (online, 18 February 2019) <https://www.ft.com/content/9de75c4a-331f-11e9-bd3a-8b2a211d90d5>.

[11] See, eg, Australian Law Reform Commission (‘ALRC’), For Your Information: Australian Privacy Law and Practice (Report No 108, May 2008) vol 2, 1413–36; Commonwealth, Parliamentary Debates, Senate, 22 June 2006, 2340 (Natasha Stott-Despoja); Peter van Onselen and Wayne Errington, ‘Suiting Themselves: Major Parties, Electoral and Privacy’ (2005) 20(1) Australasian Parliamentary Review 21; David Vaile, ‘Opinion: Australia's Privacy Laws: Time to Remove Exemptions for Politicians’, UNSW Newsroom (online, 22 March 2018) <https://newsroom.unsw.edu.au/news/science-tech/australias-privacy-laws-time-remove-exemptions-politicians>.

[12] Kelsey Munro, ‘Australia's Major Parties Defend Privacy Exemption Over Cambridge Analytica’, The Guardian (online, 22 March 2018) <https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2018/mar/22/australias-political-parties-defend-privacy-exemption-in-wake-of-cambridge-analytica>.

[13] ALRC (n 11) 1428–31.

[14] Constitution of the Commonwealth of Australia (‘Constitution’).

[15] Moira Paterson and Normann Witzleb, ‘Voter Privacy in an Era of Big Data: Time to Abolish the Political Exemption in the Australian Privacy Act’ in Moira Paterson, Normann Witzleb and Janice Richardson (eds), Big Data, Political Campaigning and the Law: Democracy and Privacy in the Age of Micro-targeting (Routledge, 2020) 162.

[16] Three other pieces of legislation are relevant: the Spam Act 2003 (Cth), the Do Not Call Register Act 2006 (Cth) (‘DNCR Act’) and the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (Cth). These pieces of the legislative framework have a narrower focus than the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth). The Spam Act 2003 (Cth) imposes restrictions on the sending of unsolicited commercial electronic messages, such as emails and SMS, including requirements to include unsubscribe mechanisms in each message. The DNCR Act 2006 (Cth) establishes a ‘do not call’ register and prohibits unsolicited telemarketing calls and faxes to numbers on the register. The Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (Cth) imposes limited restrictions on the use of electoral roll information obtained from the Australian Electoral Commission (‘AEC’), including a prohibition on commercial use. Both the Spam Act 2003 (Cth) and DNCR Act 2006 (Cth) contain similar political exemptions to the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth), which are formulated differently to the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth) exemptions. Under the Spam Act 2003 (Cth), any messages authorised by a registered political party are exempt from key requirements in the legislation, including the general prohibition on sending unsolicited commercial electronic messages and the obligation to contain a functional unsubscribe facility: Spam Act 2003 (Cth) ss 16, 18, sch 1 s 3. Under the DNCR Act 2006 (Cth), any telemarketing calls authorised by a registered political party, independent current political representative or political candidate and relating to certain matters are exempt from the prohibition on unsolicited telemarketing calls to numbers number registered on the Do Not Call Register: DNCR Act 2006 (Cth) s 11, sch 1 s 3.

[17] Personal information is defined as ‘[i]nformation or an opinion about an identified individual, or an individual who is reasonably identifiable: (a) whether the information or opinion is true or not; and (b) whether the information or opinion is recorded in a material form or not’: Privacy Act 1988 (Cth) s 6(1).

[18] Mark Burdon, Digital Data Collection and Information Privacy Law (Cambridge University Press, 2020) 140–1, 149, 183.

[19] Paterson and Witzleb (n 15) 179.

[20] A ‘registered political party’ is a political party registered under Part XI of the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (Cth): Privacy Act 1988 (Cth) s 6(1). In order to be eligible for registration, a political party must have at least 500 members enrolled to vote or a member who is a Commonwealth Senator or Member of the House of Representatives, and a written constitution: Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (Cth) s 123(1). The states and territories have separate registration schemes for political parties: see Electoral Act 1992 (ACT); Electoral Act 2017 (NSW); Electoral Act 2004 (NT); Electoral Act 1992 (Qld); Electoral Act 1985 (SA); Electoral Act 2004 (Tas); Electoral Act 2002 (Vic); Electoral Act 1907 (WA). Registration under a state or territory scheme does not qualify a political party as a ‘registered political party’.

[21] Privacy Act 1988 (Cth) ss 6(1), 6C(1), 13(1).

[22] The election must be held under an ‘electoral law’, which includes a Commonwealth, state or territory law relating to elections to Commonwealth, state or territory Parliament, or local government authority: ibid ss 7C(1)(a), (6).

[23] The referendum must be held under a Commonwealth, state or territory law: ibid s 7C(1)(b).

[24] ‘Political representatives’ means the current members of a local council, or a state, territory or federal Parliament: ibid s 7C(1).

[27] Ibid sch 1 cls 1, 5.

[28] Ibid sch 1 cl 6.

[29] Ibid sch 1 cl 3.3.

[30] Ibid sch 1 cl 7.

[31] Ibid sch 1 cls 12–13.

[32] Ibid sch 1 cls 10–11.

[33] Paterson and Witzleb (n 15) 173–80. This constitutional justification for the exemptions was also doubted at the time of inception. During consultations on the Bill, the Privacy Foundation noted that

[i]ts advice from constitutional law experts is that the limited right to free political speech which has been recognised in the Constitution ‘does not impose any relevant limitations on governments protecting individuals from how political parties or anyone else collect, store and use personal information.

House of Representatives Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs, Parliament of Australia Advisory Report on the Privacy Amendment (Private Sector) Bill 2000 (Report, 26 June 2000) 53 [5.8] (‘Advisory Report on the Privacy Amendment Bill’).

[34] See, eg, Commonwealth, Parliamentary Debates, House of Representatives, 12 April 2000, 15752 (Daryl Williams, Attorney-General); Munro (n 12).

[35] Paterson and Witzleb (n 15) 179.

[36] Privacy Act 1988 (Cth) sch 1 cl 1.1.

[37] Ibid sch 1 cl 11.1.

[38] Ibid sch 1 cl 6.2.

[39] Ibid sch 1 cl 3.3.

[40] Ibid sch 1 cl 7.

[41] Stephen Mills, The New Machine Men: Polls and Persuasion in Australian Politics (Penguin Books, 1986).

[42] Peter van Onselen and Wayne Errington, ‘Electoral Databases: Big Brother or Democracy Unbound?’ (2004) 39(2) Australian Journal of Political Science 349, 352.

[43] Ibid 353–5.

[44] Reportedly adopted by the Australian Labor Party, the Australian Greens, the Australian Council of Trade Union and at least two independent candidates: Mark Rolfe, ‘GetUp’s Brand of In-Your-Face Activism is Winning Elections – and Making Enemies’, The Conversation (online, 17 May 2019) <https://theconversation.com/getups-brand-of-in-your-face-activism-is-winning-elections-and-making-enemies-116672>.

[45] Adopted by the South Australian Liberal Party in the 2018 State election: Murphy (n 10).

[46] Dan Castleman, ‘Essentials of Modeling and Microtargeting’ in Andrew Therriault (ed), Data and Democracy: How Political Data Science Is Shaping the 2016 Elections (O’Reilly Media, 2016) 1, 2.

[47] Orestis Papakyriakopoulos et al, ‘Social Media and Microtargeting: Political Data Processing and the Consequences for Germany’ (2018) 5(2) Big Data & Society 1, 2.

[48] Jessica Baldwin-Philippi, ‘The Myths of Data-Driven Campaigning’ (2017) 34(4) Political Communication 627, 628.

[49] Varoon Bashyakarla et al, ‘Personal Data: Political Persuasion’ (Research Report, Data and Politics Team, Tactical Tech, March 2019) 88 <https://cdn.ttc.io/s/tacticaltech.org/Personal-Data-Political-Persuasion-How-it-works.pdf>.

[50] Eden Gillespie, ‘Are You Being Scanned? How Facial Recognition Technology Follows You, Even as You Shop’, The Guardian (online, 24 February 2019) <https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2019/feb/24/are-you-being-scanned-how-facial-recognition-technology-follows-you-even-as-you-shop>.

[51] Jamie Bartlett, Josh Smith and Rose Acton, ‘The Future of Political Campaigning’ (Report, Demos, July 2018) 11–12.

[52] A term hatched by Cristian Vaccari and Augusto Valeriani: Cristian Vaccari and Augusto Valeriani, ‘Party Campaigners or Citizen Campaigners? How Social Media Deepen and Broaden Party-Related Engagement’ (2016) 21(3) The International Journal of Press/Politics 294, 306.

[53] Katharine Dommett and Luke Temple, ‘Digital Campaigning: The Rise of Facebook and Satellite Campaigns’ (2018) 71(1) Parliamentary Affairs 189, 196.