University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

RATIONING JUSTICE: TEMPERING DEMAND FOR COURTS IN THE MANAGERIALIST STATE

BRIAN OPESKIN[1]*

Over the past generation there have been significant reforms to the way the state supports the just resolution of legal disputes. Influenced by public sector managerialism, the state has sought ever greater cost-effectiveness by tempering demand for justice in the courts. Using Australia as an example, this article analyses six processes by which the state has modulated this demand, namely, extinguishing, expelling, diverting, incentivising, filtering and demoting. But at what price? Greater efficiencies sometimes come at a cost to other fundamental values, such as access to justice, fair process, impartial decision-making, just outcomes and public trust. This article evaluates these tensions by examining a suite of specific demand management mechanisms that have been widely used in civil and criminal disputes in Australia.

Courts play a fundamental role in liberal states in resolving disputes and developing the legal fabric that underpins social order. They offer a special kind of dispute resolution – one that entails the use of a third party (the judge), deciding on the merits (the law), utilising structures and processes intended to preserve the authority and impartiality of the institution.[1]

Unsurprisingly, judicial process takes time, and with that comes expense for the disputants and the state. For the parties, there are the privately borne costs of legal advice, disbursements, time, and adverse rulings. For the state, there are the publicly borne costs of judicial remuneration, court staff, court houses, libraries and communication technologies. The public and private costs are inflated by the glacial pace of many court proceedings – a pace partially dictated by the commitment to procedural fairness and by the need for reasoned decision-making as an accountability mechanism under the rule of law.

Commencing earlier, but with quickening tempo since the 1990s, many countries have sought greater effectiveness in the delivery of public services, including in the justice sector.[2] One motivation for reform has been to promote access to justice by removing geographic, economic, social and cultural impediments to meeting legal needs. Good laws are of little value if the legal system does not provide a useful method for enforcing them.[3] Another motivation has been fiscal: governments face insatiable demand for finite public resources and are driven to ever greater cost-effectiveness as they seek new ways to keep the wheels of justice turning faster, with less friction, and at lower cost. Managerialism, privatising, outsourcing and downsizing have become familiar themes in public sector management discourse.

A recent expression of this movement in the Australian justice sector is the controversial decision to merge the Family Court with the Federal Circuit Court in service to the goal of improving the judicial resolution of family law disputes.[4] The Attorney-General’s Department claimed that the reforms will ‘[improve] the efficiency of the family law system, reducing the backlog of matters before the family law courts, and driving faster, cheaper and more consistent dispute resolution’.[5] The Attorney-General also stated in Parliament that the measure will ‘assist families to have their matters dealt with quickly, efficiently, cheaply and as safely as possible’.[6] These aspirations are reflected in the objects of the new Act, one of which is ‘to ensure that justice is delivered by federal courts effectively and efficiently’.[7] Structural reforms such as these are analysed further below, but they are one of many mechanisms used by governments today to advance the goal of cost-effectiveness in dispute resolution.

This study has two aims. The first is to examine the processes by which the state has sought greater cost-effectiveness in the justice system by tempering demand for adjudication in the courts.[8] Courts often regard themselves as the ‘central suppliers of justice’, yet they are not the sole means of resolving disputes in society.[9] If an overarching objective of the justice sector is to ‘contribute to a safe and secure community and promote a law-abiding way of life’,[10] courts can be seen as one formal element in a complex system that allows a degree of substitution between component parts. Over the past generation, the relative position of the courts within the justice sector has been eroded as other mechanisms for resolving disputes have been created or enhanced. This study presents a typology of the state’s economising processes and illustrates them through practical case studies.

The second aim is to evaluate these economising processes by reference to the fundamental values that underpin the justice system. An evaluation is needed because action that advances one state objective (eg, cost-effectiveness) sometimes exacts a price in terms of other objectives. However, the tensions and trade-offs are specific to the problem at hand. The evaluation helps to identify where managerialism in the justice sector may be inimical to the public good because it fails to find an appropriate balance.

When analysing the state’s economising processes, this article refers to the conduct of all governmental organs through which the state exerts its authority – executive, legislative and judicial. The executive performs a central role in initiating policy in response to (and sometimes in the face of) advice given by government departments and independent advisory bodies. The implementation of these policies usually requires legislative action, of which many examples are canvassed below. The judicial branch has also been a significant player in the process of tempering demand for the courts. In one sense, this is so because the shortcomings of the judicial system – too slow, too expensive, too unresponsive – may encourage disputants to ‘vote with their feet’ by seeking alternative ways to resolve disputes. More positively, courts have encouraged this movement through a variety of means, including rules of court made under delegated legislative power (eg, allocating litigation costs), the exercise of judicial discretions (eg, granting or refusing leave to appeal) and substantive decisions (eg, supporting active case management).[11] This is not to suggest that courts regularly seek to shed their core functions of dispute resolution, but they are participants in a complex economising process designed to streamline the delivery of justice.

The central themes are examined through the lens of the Australian judicial system, but the phenomena discussed here share common ground with other legal systems in the common law tradition. This can be seen, for instance, in the contemporaneity of major inquiries into civil justice in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States (‘US’) from the late 1990s, and in the similarity of many of their reforms.[12] There is a need for comparative research on these questions, but it is not possible to address them within the confines of this article.

Within Australia, this study does not purport to be an exhaustive examination of the federal, state and territorial components of the judicial system. Rather, it draws on representative case studies to illustrate broader concepts. The examples are taken from different Australian jurisdictions, and from the civil and criminal sides of the justice system, to underscore the point that the state’s economising goals are ubiquitous, even if the mechanisms for realising them are varied. Moreover, to better understand the integrated nature of the justice sector as a ‘system’, this study consciously pursues breadth of coverage, even if this comes at a cost to the depth of treatment of individual elements.

While this study focuses on the processes for tempering demand for the courts, there is a parallel question of supply, which has been considered elsewhere.[13] Governments manage judicial labour through new judgeships, appointing acting judges on short-term commissions, raising mandatory retirement ages, increasing the use of allied personnel to free judicial officers from minor routine work, and enhancing judicial productivity so that more output can be achieved with the same input.[14] These strategies are vital to the efficient functioning of the courts, but they are not canvassed here.

This article is organised as follows. Part II substantiates the claim that there has been a turn away from Australian courts over the past generation, which is evident in government expenditure on the courts and in case lodgements in the courts. Part III presents a typology of the processes by which the state has encouraged this movement, which are presented under six rubrics: extinguishing, expelling, diverting, incentivising, filtering and demoting. Part IV identifies the fundamental values that are implicated in these processes, including access to justice, fairness of process, impartiality of decision-making, just outcomes and public trust in the administration of justice. The core of the study is situated in Part V, which explains the economising processes and illustrates them with case studies in civil and criminal disputes. Part VI concludes by acknowledging the importance of cost-effectiveness in any functional system of dispute resolution while advocating for due weight to be given to other fundamental values when they collide.

There has been a turn away from Australian courts over the past generation. It is evident in civil and criminal matters but is most pronounced in the former. This phenomenon has also been experienced in other common law countries. In the US, Galanter was an early observer of the precipitous decline in the number of trials – federal and state, civil and criminal, jury and bench[15] – and the same has been noted in Canada in specific sectors.[16] In England, Genn has remarked on the long-term ‘decline, and now virtual extinction of trials in the civil courts and with it public determination of the merits of civil disputes’.[17] The Australian evidence is similar, as can be seen in two corroborating sources of data, namely, government expenditure on the courts and case lodgements in the courts.

A Government Expenditure on the Courts

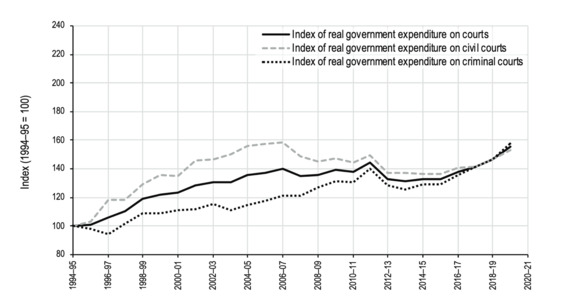

Since 1995, the Productivity Commission has collected data on the effectiveness and efficiency of government-funded social services. Its annual Report on Government Services (‘RGS’) contains statistics on recurrent government expenditure on Australian courts across all jurisdictions and levels of the court hierarchy. In real terms (in 2019–20 dollars), government expenditure on courts rose from $1.4 billion in 1994–95 to $2.2 billion in 2019–20; an increase of 56% over 26 years.[18] Nearly all that growth occurred during the first half of that period, followed by stagnation over the succeeding 10 years and a small uptick in the most recent years. This is shown in Figure 1 (solid line), in which comparison is made between several indices, using 1994–95 as the base year. The change in government expenditure on courts is in line with population growth of 42% over the same period (dotted line), such that per capita expenditure on courts has barely shifted over a generation. This would be unremarkable but for the fact that real government expenditure on all sectors rose by 129% over the same period (dashed line). This signals a significant retreat in expenditure on the courts relative to all areas of government activity (of which the largest components have been welfare, health, education and defence).

Figure 1: Real government expenditure and population, Australia, 1994–95 to 2019–20[19]

A more nuanced understanding can be obtained by disaggregating government expenditure on courts into civil and criminal components. Figure 2 shows that real expenditure is characterised by two distinct periods. From 1994–95 to 2006–07, both civil expenditure (dashed line) and criminal expenditure (dotted line) rose, the former at a much faster rate. However, from 2006–07 to 2016–17, there was an absolute decline in real government expenditure on civil courts (followed by a recent uptick), while real expenditure on criminal courts has continued to rise at a similar rate to the earlier period. The stagnation in real expenditure on all courts (solid line) for the decade 2006–07 to 2016–17 is the net effect of these countervailing forces. Genn’s observation about the decline of civil justice in the United Kingdom thus has its counterpart in Australia.[20]

Figure 2: Real government expenditure on civil and

criminal courts, Australia, 1994–95 to

2019–20[21]

Figure 2: Real government expenditure on civil and

criminal courts, Australia, 1994–95 to

2019–20[21]

B Declining Lodgements in the Courts

A supplementary means of evaluating demand for adjudication is to examine the number of matters commenced in Australian courts. Some small-scale studies have done this for individual courts,[22] but it is more instructive to take a national perspective using annual data on court ‘lodgements’ published by the Productivity Commission.[23] This may be viewed as a proxy for court demand, although it adopts a court-centric view of what constitutes a legal ‘case’ in circumstances where sociologists, economists, anthropologists, and political scientists have differing conceptions about the relevant unit of analysis.[24]

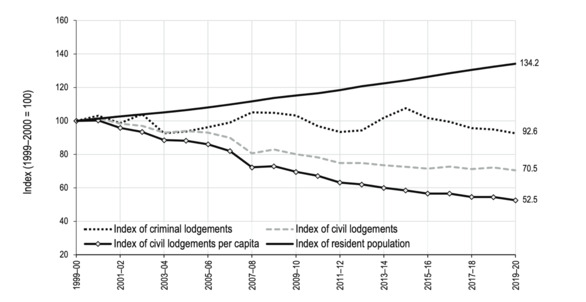

Figure 3 charts the number of civil and criminal lodgements, using indices in which 1999–2000 is the base year.[25] In that year, there were 1.76 million lodgements (53% civil and 47% criminal). By 2019–20 this had fallen to 1.42 million lodgements (46% civil and 54% criminal) – a reduction of some 335,000 cases annually. The number of criminal lodgements (dotted line) shows cyclical fluctuations, but the overall trend is one of stability – in 2019–20 there were just 7% fewer lodgements than 20 years earlier. By contrast, the decline in civil lodgements (dashed line) has been strong and persistent, with a 30% reduction over the same 20-year period.

Figure 3: Court lodgements and population, Australia, 1999–2000 to 2019–20[26]

These changes have taken place against the backdrop of a population that has been rising steadily (solid line). Population growth affects the volume and patterns of human activity in a community. It is self-evident that a jurisdiction of 1,000,000 people will experience a greater volume of crime than one of 100,000, all else being equal, simply because it has ten times the number of potential offenders and victims.[27] The same is true of civil disputes because additional population engenders more commerce, more relationships and more interactions with the potential for disputation. These size effects have repercussions for the judicial system. One would expect them to be manifested in greater demand for adjudication as population grows over time, such that demand per capita remains roughly stable. The fact that this is not the case highlights the dramatic decline in demand. In criminal matters, the 7% fall in lodgements, set against the 34% increase in population, has resulted in a 31% decline in lodgements per capita. In civil matters, the 30% fall in lodgements, set against the 34% increase in population, has resulted in a 47% decline in lodgements per capita. The latter point is illustrated in Figure 3 by the index of civil lodgements per capita (solid line with marker).

In summary, there has been a precipitous decline in civil matters commenced in Australian courts over the past 20 years, both in absolute terms and per capita, while in criminal matters demand has been steady in absolute terms but has still declined significantly per capita. For reasons that will be interrogated below, Australian courts today do not play the same empirical role they did a generation ago.

III SIX PROCESSES FOR TEMPERING DEMAND

The turn from the courts has not been the product of chance. It is principally the result of concerted action by the state to make justice more cost-effective by confining courts to a narrower adjudicatory domain, while providing alternative pathways to quell disputes. These measures have been adopted sporadically over time and space, but hindsight allows them to be drawn together as a purposeful ‘solution’ that puts a price on justice, often at a cost to other system values.

Six processes by which the state curbs demand for the courts are as follows:

1. Extinguishing – existing rights or duties are abrogated so that no legal dispute can arise between individuals, or between individuals and the state.

2. Expelling – legal disputes are shunted from the state-sponsored system of civil or criminal justice, for resolution in the private sphere.

3. Diverting – legal disputes are retained within the state’s justice system but rechannelled for resolution by processes that lie beyond the courts.

4. Incentivising – rewards and punishments are used to influence the behaviour of disputants in deciding what use to make of the state’s judicial system.

5. Filtering – legal disputes are screened so that ‘unmeritorious’ disputes do not reach the courts at all, or do not progress further in the courts than is necessary.

6. Demoting – legal disputes are resolved by the courts but are pushed down to the lowest and most economical tier at which they can be satisfactorily adjudicated.

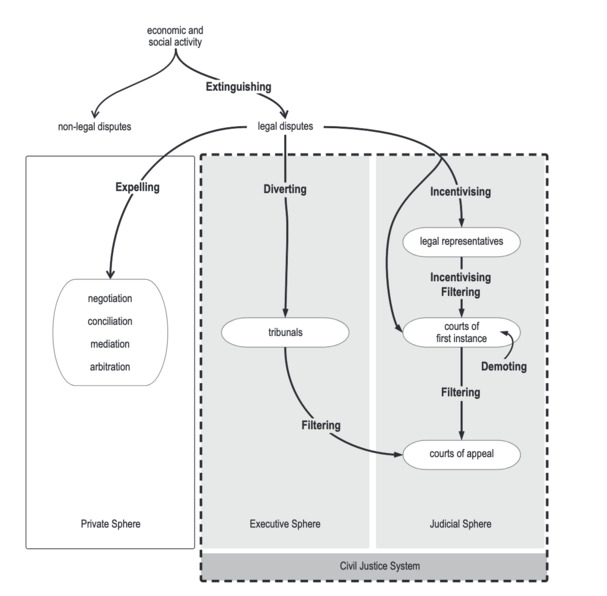

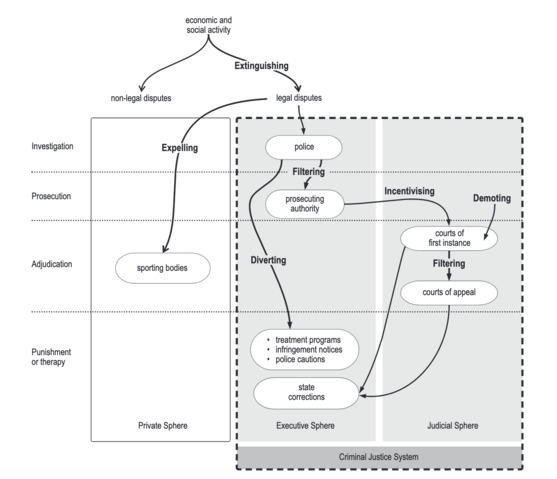

Schematic representations of these pressure points for state intervention are shown in Figure 4 for civil matters and Figure 5 for criminal matters. Human activity gives rise to disputes (some legal, some non-legal), which percolate through various channels according to the restrictions placed in their path. The judicial system is represented by the rightmost of three panels, sitting within the larger system of civil or criminal justice. Some disputes never reach the judicial system because legal rights or obligations are extinguished, or redirected to the private sphere, or channelled to parts of the justice system beyond the courts. Matters that can be resolved by the courts are also subject to restrictions. The modulating processes are marked in the diagram at the point at which they impinge on the operation of the system.

Figure 4: Tempering processes in civil matters[28]

Figure 5: Tempering processes in criminal matters[29]

IV FUNDAMENTAL VALUES OF THE JUSTICE SYSTEM

The goal of cost-effectiveness, to which the economising processes are directed, is not the sole, nor arguably the most important, value of a system of justice. Pursuing this goal may generate tensions with other important values. These cannot be entirely avoided, but a mature legal system seeks an appropriate accommodation between competing values when they clash.

Understanding the interrelationship between fundamental values requires a distinction to be drawn between rules, principles and values, which is best explained by example. In Australia, there is a constitutional rule that no judge may serve in federal judicial office beyond the age of 70 years.[30] Other jurisdictions have different rules on that topic – in the Northern Territory the age limit is 72 years, and in New South Wales and Tasmania it is 75 years.[31] Despite the differences, these rules all stand in service to a higher principle, namely, that judges should be subject to mandatory retirement at a fixed age to avoid the costs of overstaying, such as mental decrepitude in office.[32] Yet that goal might also be achieved by different institutional arrangements, such as judicial terms of fixed duration (eg, the 12-year non-renewable term of judges of the German Constitutional Court).[33] If we abstract to a higher plane, the principle of mandatory retirement at a fixed age (like the alternative of fixed terms) stands in service to the higher value of quality decision-making that delivers just outcomes to the parties according to law. The distinction between rules, principles and values associated with judicial tenure is not merely about their degree of detail, but about identifying the ultimate justifications that specific rules are designed to serve.[34]

The values that underpin the justice system have been extensively discussed, especially in the context of civil justice. Despite differences in nomenclature and classification, there is substantial accord about some elements and discord about others. Some of the key conceptual contributions to the debate have been canvassed by Olijnyk and do not need repetition here.[35] In the context of civil matters, Andrews has identified four cornerstones of the civil justice system, which he lists as access to justice, fairness of process, speed and effectiveness, and just outcomes, with each value harbouring a cluster of lower-order tenets.[36] Shetreet has proposed a five-point typology, which overlaps with Andrews’ list in many respects but differs in others.[37] Shetreet’s values comprise fairness of the adjudication process, efficiency of the justice system, access to justice, public confidence in the courts and independence of the judiciary.

In finding common ground between these accounts (and with some modifications of language), this article proceeds on the basis that a system of justice should strive to respect the following values:

1. Access to justice – the extent to which persons are able to effectively understand their legal rights, protect those rights, obtain an outcome, and have the result enforced.[38]

2. Procedural fairness – processes and practices that give disputants a genuine voice, with respectful treatment, through institutions that demonstrate an ethic of care (reflecting research indicating that litigants consistently value fairness of process above fairness of outcome).[39]

3. Impartiality – decision-making that treats all parties fairly and free from bias, prejudice or preference (to the extent humanly possible).[40]

4. Just outcomes according to law – outcomes based on the merits of the case (rather than according to chance or might), where merit is assessed by legal standards.[41]

5. Public trust in the administration of justice – made necessary because the efficacy of the courts (as the ‘weakest’ of the three branches of government)[42] depends on the continuing acceptance of their authority by the community.[43]

6. Cost-effectiveness – how well the justice system converts resource inputs into outcomes for individuals and the community.

The relationships between these values are complex. This article frequently raises the question whether there is an agonistic relationship between cost-effectiveness and other system values. Similarly, Olijnyk has suggested, in the context of mega-litigation, that value tensions are inherent in large civil actions.[44] Giving parties A and B the fullest opportunity to present their case, without regard to the court resources that consumes, may well promote those parties’ access to justice. However, it might also mean that litigants C and D face a longer wait for their day in court, while plaintiffs E and F may decide that court delays are now so great it is not worth litigating at all.[45] These frictions were pithily summarised in a South Australian case many years ago when King CJ remarked that ‘a party is entitled to his day in court but not to someone else’s day in court’.[46]

However, fundamental values of the justice system do not always work in opposition to each other – sometimes they are mutually supportive. For instance, procedural fairness and just outcomes according to law both bolster public trust in the administration of justice. Likewise, greater cost-effectiveness, through quicker and cheaper dispute resolution, may promote access to justice, as the Attorney-General argued when justifying the 2021 merger of the Family Court and the Federal Circuit Court.[47] It is not possible to examine every dyadic relationship between values here. Rather, this article seeks to illuminate key tensions, and occasional harmonies, between fundamental values when the state takes action to curb demand for the courts.

V CASE STUDIES ON THE ECONOMISING PROCESSES

This Part explains the state’s six economising processes in greater detail and proffers case studies to illustrate their operation in practical contexts. The case studies are taken from different Australian jurisdictions and span both civil and criminal matters.

Courts provide an institutional mechanism for resolving disputes according to law. It follows that the legal rules assigning liability for conduct ultimately determine the availability of court action. These rules expand and contract with legislative intervention and changing perceptions of the judicial function.[48] Historical examples of expansion include the rise of negligence law, civil rights, and the flourishing of judicial review of administrative action. To take a comparative illustration, in the US the unbridled growth of law (‘hyperlexis’) has been credited as a cause of the ‘litigation explosion’ that was observed in the 1960s and 1970s.[49]

Conversely, legislation may abrogate legal rights or extinguish obligations, and thus deny the basis on which disputants can seek redress in the courts. The examples of contraction discussed below are the abolition of common law rights to compensation for personal injuries in the civil sphere[50] and the decriminalisation of certain conduct in the criminal sphere.

1 Abrogating Rights to Compensation for Personal Injuries

Civil liability offers a prime example of the state’s ability to constrain demand for litigation by extinguishing rights. New Zealand demonstrated the high-water mark of this approach in the 1970s when it abolished large swathes of tort law and replaced it with a statutory right to compensation for accidental injuries, regardless of fault.[51] Long before, Australia had enacted a modest version of such a scheme for workplace injuries, where there is still a statutory no-fault system of compensation, funded by employers’ insurance premiums, in lieu of a common law action for damages.[52]

More recently, beyond the field of workers’ compensation, there have been other tort law reforms relevant to the process of extinguishment. In 2002, a national review panel was constituted ‘to examine a method for the reform of the common law with the objective of limiting liability and quantum of damages arising from personal injury and death’.[53] The review was prompted by a so-called ‘insurance crisis’ resulting from burgeoning levels of compensation for personal injury.[54] The resulting Review of the Law of Negligence (‘Ipp Report’) became the impetus for nationwide reforms covering civil liability, quantum of damages and procedure.[55] Although the reforms did not adopt the radical approach of workers’ compensation legislation, they had the practical effect of extinguishing previously valid claims at common law. They did so by adjusting the rules of civil liability – tightening the limitation period, reducing the standard of care, narrowing the scope of the duty of care, broadening defences such as assumption of risk and excluding damages in cases below a minimum threshold.

The impact of these changes on demand for courts in civil matters was stark. Wright examined personal injury litigation before and after the Ipp Report and found there was a dramatic decline.[56] Leaving aside the spate in filings lodged in anticipation of the restrictions taking effect, the rate of filing declined from an average of 4.5 claims per 10,000 population in 1996–2001 to just 1.7–1.8 claims per 10,000 in 2004 and 2005 – a 60% decline in claiming rates.[57] Wright concluded that ‘large numbers of people who are injured through the fault of others, and would once have had substantial claims, no longer seek compensation’.[58]

The reduction in civil litigation through extinguishment comes, however, at a cost to other fundamental values of the justice system. Specifically, it negatively affects access to justice because aggrieved persons who suffer injury or loss are no longer able to obtain a remedy at law, and it may deleteriously affect public perceptions of the administration of justice insofar as injured parties are left to bear the burden of loss caused by the fault of others.

The criminal law prohibits a broad range of conduct of varying seriousness, from murder to flying a kite to the annoyance of others.[59] The types of conduct that attract the opprobrium of criminal sanction have evolved over time because of additions to, and subtractions from, the corpus of criminal law. The question that arises here is the extent to which the subtractions (ie, decriminalisation) have been motivated by the state’s desire to dampen demand for the criminal courts. In Australia, steps have been taken over past decades to decriminalise public drunkenness, vagrancy, sex work, abortion, homosexuality and possession of cannabis. In most cases, the motivations for change have been shifting social mores, new approaches to regulating social problems, and expanding conceptions of human rights.

Nonetheless, the economising effects of decriminalisation have not been far from consideration. Reforms to public drunkenness laws in the 1990s, for instance, overtly sought to reduce the number of cases heard by the lower courts and lessen the amount of police time devoted to dealing with persons apprehended for drunkenness.[60] Moreover, the number of pardons recently granted to men for historical convictions for homosexual offences indicates the scale of state resources that have been expended on such matters in the past – in the United Kingdom alone, 50,000–100,000 pardons have been granted since 2017 under the so-called ‘Turing’s law’.[61]

These instances of decriminalisation have had only a modest impact at a systems level because there have been countervailing forces – the expansion of the regulatory state and the growth of social punitiveness have vastly increased the number and variety of criminal offences regulating human conduct in complex societies.[62] Writing of the US, but in terms relevant to Australia, Husak has noted the expansion of criminalisation in contemporary society through the creation of offences that often lack the moral culpability traditionally associated with notions of crime (kite-flying being a case in point).[63]

This account suggests that decriminalisation can occur in very different contexts. Where it legalises conduct that was once regarded as immoral (drunkenness, sex work, homosexuality, etc), it poses few risks to other values of the justice system because it simply removes individuals from that system. Perhaps the only adverse effect in such cases is on public trust in the administration of justice among people who believe the newly legalised conduct remains immoral.

Besides extinguishing rights and obligations, the state curbs demand for the courts by shunting some legal disputes beyond the state-sponsored justice system, for resolution in the private domain – a process here called expulsion. This is a radical option because the state loses control of the process, while still having an interest in the fair resolution of disputes as a means of maintaining social order. Private resolution also runs a risk of lessening fidelity to ‘the law’ as the merit-base on which disputes are resolved. Genn, for instance, notes that ‘official pressure to divert civil disputes to private dispute resolution’ in the United Kingdom locates civil justice as a private matter and diminishes its public function in serving the rule of law.[64] But this can also be an attraction for the parties because it allows disputants to find a mutually acceptable solution ‘in the shadow of the law’, freed from the formal constraints of domestic legal doctrine and procedure.[65] It must also be acknowledged that private resolution may represent not only a push outward by the state from the justice system, but a pull inward by private institutions seeking dispute resolution business for commercial gain.

Expulsion is more common in civil than in criminal matters because in civil disputes the interests at stake are usually pecuniary, thus allowing more opportunity for private accommodation. In criminal matters, disputes are between the individual and the state, in which the Crown seeks vindication of a public interest by punishing breaches of social order. It is not easy to do this outside state organs. The examples chosen to illustrate expulsion in these very different contexts are alternative dispute resolution (‘ADR’) in civil disputes and the disciplining of perpetrators of violence in sport via sporting bodies, in lieu of pursuing them through the criminal courts.

1 Alternative Resolution of Civil Disputes

The ADR movement originated in the US in the 1960s and was transplanted to Australia in the 1970s and 1980s.[66] It has been hailed as an informal, non-adversarial substitute for court proceedings, but in truth ADR is an umbrella term that covers a continuum of civil dispute resolution practices.[67] These range from facilitative processes (where an ADR practitioner assists the parties to resolve their own dispute – eg, negotiation or mediation), to advisory processes (where a practitioner advises the parties on the facts, law and possible outcomes – eg, conciliation), to determinative processes (where a practitioner hears evidence and makes a decision on the outcome – eg, arbitration). The last of these bears many of the hallmarks of adjudication in the courts, albeit with a private arbitrator, rather than a judge, as decision-maker.

ADR offers benefits for the judicial system by relieving the courts of some of their civil caseload. It has been said that one of the principal responses of the judiciary to the ‘tidal wave’ of litigation has been to seize on ADR ‘as the veritable tabula in naufragio’ (plank in the shipwreck).[68] For the parties themselves, there are other motivations for preferring ADR over litigation. These include the potential for lower cost, quicker resolution, confidentiality, creative ‘win-win’ solutions that could not be sanctioned by the courts, determination of outcomes by consent and preservation of personal or commercial relationships beyond the dispute.[69] Fuelled by these benefits, ADR has seen a robust growth in Australia in the past 30 years.[70] ADR programs can be found in the community sector and in specific industries (telecommunications, financial services, etc) to resolve disputes between consumers and businesses through industry-funded bodies. They can also be found within the civil justice system in tribunals and courts, which are mentioned under the rubric of diversion in Part V(C) below.

Beyond its economising benefits, ADR poses challenges for other fundamental values. The private nature of the dispute resolution means that fair process cannot be assured. Some argue it entrenches existing inequalities of bargaining power between the parties, with consent often being coerced – ‘the civil analogue of plea bargaining’.[71] Moreover, private resolution obscures the outcome from public scrutiny and may detract from a just outcome according to the legal merits of the case. The law may supply little more than a framework for discussion rather than an objective yardstick for fair determination of the outcome.

Contact sports, and more so combat sports, involve the use of force that would breach the criminal law if undertaken in other circumstances, yet the criminal law of assault is rarely invoked in a sporting context. Punishments for breaching the ‘rules of the game’ are generally meted out, if at all, through disciplinary action taken by the relevant sporting body rather than by the courts.[72] This has led to a perception that ‘the sports field is an arena of private conflict, in which the criminal law has no jurisdiction’.[73] Potential breaches of the criminal law are thus expelled from the state-sponsored justice system, to be dealt with elsewhere.

This privatisation of criminal law has been possible because of two kinds of state action. First, police are reluctant to lay charges against sports players because aggression is normalised in Australian sporting culture, and those seeking to enforce the criminal law are seen as unwelcome prowlers.[74] Police regard discipline for violent behaviour in sport as a matter internal to the sporting code and they are unlikely to investigate, at least where private regulation of the sport is robust.[75] The same disinclination likely infects prosecuting authorities.

Second, the courts too have been reluctant to intervene, with several influential decisions of the English courts in the late 19th century carving out an ill-defined sports exemption to the criminal law.[76] The judiciary has held that sporting participants are presumed to consent to physical contact that accords with the rules and culture of the game, and even to some foul play.[77] The courts have stepped in only where the violent acts are so egregious that the law does not allow a victim to consent to them, such as where there is an intention to cause serious injury or death.[78] For the most part, courts have bowed to the convenience of private regulation, stating that ‘in the majority of situations there is not only no need for criminal proceedings, it is undesirable that there should be any criminal proceedings’.[79]

The bypassing of criminal law in favour of self-regulation has been hotly debated in sport. Much depends on the arrangements put in place for specific sports. Australia has taken self-regulation to a high point in the arrangements adopted by the National Rugby League (‘NRL’) and some other sporting codes. There, a private domestic tribunal has been established to deliver a highly formalised system of ‘sports justice’, utilising an NRL ‘judiciary’ as a simulacrum of the state’s judicial system.[80] In that arrangement, there are few conflicts with fundamental values of the justice system because self-regulation has mirrored the values of the state’s criminal justice system.[81] The exception is the achievement of just outcomes according to law, since sports bodies apply the internal rules of their code, not the criminal law. The robustness of the NRL arrangements supports the attitude of the criminal justice system in allowing the sport to police itself, but it has not saved the state’s judiciary much work because few cases of injurious conduct in sport rise to the level of criminality. Other sports, with less formalised systems for punishing violence, may raise greater concerns.

The object of diversion is to keep disputes outside the judicial system, while nevertheless retaining them within the state-sponsored justice system. This differs from the process of expulsion, where dispute resolution is relegated to the private sphere. In this section, civil diversion is illustrated by the role of state tribunals, with their less-formal procedures overseen by ‘members’ who perform quasi-judicial functions. Criminal diversion is illustrated by the way minor criminality, such as traffic infringement, has been almost entirely removed from the courts and transferred to administrative machinery within the state bureaucracy. Similar phenomena have been observed in other jurisdictions, with Galanter describing the process in the US as one of ‘displacement’ of adjudicatory functions to the periphery.[82]

The use of diversion to attenuate demand for the courts has proliferated in recent decades. Other instances of civil diversion are the mandatory use of ADR in civil litigation (arising from pre-filing obligations or referral by a judge during proceedings)[83] and the expanding scope of independent but state-funded ombudsmen to resolve disputes between individuals and government.[84] Other instances of criminal diversion include: police warnings and cautions before charges are laid; education and treatment programs; restorative justice and therapeutic jurisprudence programs;[85] and systems of military justice and parliamentary discipline. Each mechanism brings its own challenges to the core values of the justice system, as illustrated in the examples below.

Across Australia, there are robust tribunal systems that serve as alternative venues for legal decision making in a wide variety of civil and administrative matters.[86] For over 30 years, there has been a steady haemorrhaging of civil jurisdiction away from the courts towards these bodies, in a process described as ‘tribunalisation’.[87] Historically, there were hundreds of specialised civil tribunals, but today their jurisdiction has been substantially centralised in ‘super tribunals’, which may be found in every state and territory (bar Tasmania) and at the federal level.[88] The number of matters heard in these tribunals is substantial. In 2018–19, some 260,818 matters were lodged in the super tribunals, which is 42% of the 622,849 civil matters lodged in corresponding federal, state and territory courts in the same period.[89]

The importance of tribunals in managing the demand for courts arises from the potential overlap in the jurisdiction of courts and tribunals. There is no strict separation of powers at the state level so that, if the legislature so authorises, a state tribunal may exercise state judicial power that could otherwise have been conferred on a state court.[90] This can be done by conferring concurrent jurisdiction on courts and tribunals, while imposing cost disincentives for proceedings in the courts (see Part V(D)), or more radically by conferring exclusive jurisdiction on the tribunal. This situation has incurred the ire of some judges who see this as creating undesirable competition between courts and tribunals for jurisdiction, power and resources.[91]

At the federal level, by contrast, there is a strict constitutional demarcation between the exercise of judicial and non-judicial power.[92] This has had the effect of halting the proliferation of federal tribunals and encouraging the creation of a lower-tier federal court as an alternative avenue for the resolution of smaller civil disputes (see Part V(F)). Nonetheless, the synergy between federal courts and federal tribunals can be seen in their overlapping membership (many federal judges serve as judicial members of the tribunals) and in the operational support given by the Federal Court to tribunals in the fields of competition law, copyright, defence force discipline and native title.[93]

The advantages of proceeding in a tribunal rather than a court include cost, speed, specialisation and informality, but in an institutional setting that respects many fair process values developed in the courts.[94] Yet these benefits do not make ‘tribunalisation’ an unequivocal blessing. Tribunal members typically lack the protection of full judicial independence, making them more politically vulnerable than judicial officers. This danger was demonstrated in 2018 when the Australian Government broke with the settled practice of apolitical merits-based appointments by selecting a suite of conservatively aligned individuals (including former parliamentarians) to sit as members of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal.[95] The tendency to deprive courts of jurisdiction in favour of bodies that lack judicial independence thus weakens the rule of law and may compromise the values of impartiality of decision-making and public trust in the administration of justice.[96]

2 Criminal Infringement Notice (‘CIN’) Systems

Many minor infractions of the criminal law are no longer dealt with in the courts but through the wheels of state bureaucracy – leading to ‘technocratic justice’ that has been said to ‘denude the criminal law of its moral content’.[97] The foundations were laid in the 1950s when fines were introduced for breaches of road traffic legislation. Over time, CIN systems have expanded widely to ‘address the effect of minor law breaking with minimum recourse to the machinery of the formal justice system’.[98]

The essence of a CIN system is that an alleged offender is invited to expiate their liability for an offence by payment of a penalty. The penalty is imposed by an administrative (often automated) process and is fixed in advance by the legislature without regard to the individual circumstances of the offence or the offender. The punishment is typically a monetary penalty, but it may be supplemented by other sanctions such as driver’s licence demerit points or licence suspension.[99] Their expediency benefits the state, as much as the citizen, because the state ‘gains a stream of low-cost penal revenue without overwhelming its courts with routine cases’.[100]

The use of CIN systems has grown exponentially due to the increasing number of agencies authorised to issue infringement notices, the increasing number of offences for which they may be issued, and technological innovations (eg, traffic cameras) that allow more offences to be detected. In just one state, Victoria, as many as 120 agencies (in government, local council, education, health and industry) are authorised to issue infringement notices with respect to 3,261 offences under 50 statutes.[101] In 2016–17, those agencies issued 5.4 million infringement notices (to a population of 6.3 million residents). Only 1.4% of notices were contested by the recipient in the courts.[102]

These statistics suggest that CIN systems have alleviated the lowest criminal courts of much drudgery. Yet the economising benefits come at a cost to fundamental system values and question the quality of justice dispensed in the name of the state. In theory, access to justice is preserved because an alleged offender can elect to challenge an infringement notice in court. But there is substantial evidence that CIN systems operate harshly in relation to the least advantaged people in society, challenging the notion that access to justice is safeguarded.[103] Systems of technocratic justice also test the value of just outcomes according to legal merits because of the twin risks that innocent people will settle claims by paying a modest penalty as a matter of convenience and that penalties will be imposed without due regard to factual circumstances. If a CIN system is seen to be driven by fiscal rather than correctional objectives, it can also threaten public trust in the administration of justice.

The process of diversion considered above covers a range of circumstances in which the state mandates that disputes are to be resolved beyond the courts. There are other situations in which the state gives disputants the freedom to choose the courts but seeks to influence that choice through a suite of incentives and disincentives. The examples used to illustrate this are, in civil cases, the rules regulating the allocation of legal costs in litigation and, in criminal cases, the role of plea bargaining. The former imposes financial disincentives on a party who pursues an unmeritorious civil claim or defence, the latter imposes carceral disincentives on an accused who declines to plead guilty and who therefore puts the state to the expense of a trial.

1 Allocating Litigation Costs in Civil Cases

Civil litigation imposes substantial private costs on disputants; costs comprised overwhelmingly of the bills payable to each party’s legal advisers.[104] The expectation of high legal costs is a major impediment to initiating litigation, especially where the costs are disproportionate to the value at stake. In long-running cases, legal costs can subsume the entire value of what is in dispute, as memorialised in the fictitious case of Jarndyce v Jarndyce in Charles Dickens’ Bleak House.[105]

The parties’ expectations of costs are interwoven with the rules governing the allocation of private litigation costs upon winning or losing the case. These rules need to strike a balance between competing objectives – on the one hand, the cost-effectiveness of deterring worthless litigation, and on the other, the promotion of access to justice to redress legitimate grievances. The balance is achieved through rules for determining who pays and how much they pay,[106] but it is a dynamic environment that has seen many changes in recent years.[107]

As to who pays, Australian law generally follows the English rule of ‘loser pays’, although there are discrete areas (eg, family law) where the ‘American rule’ prevails and each party bears their own costs.[108] As to how much they pay, there are several variations – costs may be recovered from the losing party on a full indemnity basis, on a taxed basis (limited to prescribed fee schedules), or on a fixed cost basis set by the court in advance.[109]

Many of the costs rules purposefully disincentivise litigant behaviour that is inimical to the effective operation of the judicial system. First, the loser pays rule instils in the parties the ‘sober realisation of the potential financial expense involved’.[110] The rule creates a financial deterrent to commencing unmeritorious litigation because it increases the expected cost of losing (the loser gets no damages and pays two sets of legal fees) and thus acts to protect the scarce resources of the publicly funded court system.[111] Second, the courts have guarded the judicial system from abuse of process by using their inherent powers to award costs against parties who waste the courts’ time, although the success of their efforts has been questioned.[112] Third, Australia has so far rejected damages-based billing, whereby a lawyer receives an agreed percentage of the damages awarded to a successful client.[113] This kind of contingency fee is considered too encouraging of entrepreneurial litigation, although ‘no win no fee’ funding arrangements are permitted.[114]

The balancing point between cost-effectiveness and access to justice is not easy to calibrate. In a thoughtful report, the Australian Law Reform Commission many years ago emphasised the role of costs orders in enforcing the courts’ control of the litigation process and encouraging early settlement.[115] It recommended reforms to allow courts to award costs against parties who cause unnecessary delays or unreasonably pursue issues on which they fail, or who bring proceedings vexatiously. However, the report gained little traction and most of its recommendations remain unimplemented. Even if primacy were given to the cost-effectiveness values of the judicial system, comfort may be taken from the fact that costs allocation rules rarely generate conflict with fundamental values of the judicial system (other than access to justice discussed above). This is because the power to award costs must be exercised judicially, with all that this entails in terms of fair process, impartiality and just outcomes according to law.

2 Plea Bargaining in Criminal Cases

In criminal matters, litigation cost rules are an inadequate means of tempering demand for the courts because cost-shifting is highly restricted. Nevertheless, economy is achieved through the incentivising practice of plea bargaining, which has long been prevalent in the US and has gradually diffused globally.[116] A plea bargain is an agreement between a criminal defendant and a prosecutor whereby the defendant pleads guilty to a specific charge in exchange for some prosecutorial concession. The concession might be a less serious charge (charge bargaining), fewer counts of the same charge (count bargaining), a lesser sentence (sentence bargaining) or agreement as to facts that may be relevant to sentencing (fact bargaining).[117]

In whichever guise, plea bargaining is a ‘response to capacity overload in the criminal justice system’,[118] yet its merits are hotly contested. Its adherents note the avoidance of lengthy criminal trials, with the consequent preservation of judicial resources and the prospect of a more favourable outcome for the accused. Its detractors point to the perversion of justice that can arise from the incentive structure, including encouraging innocent persons to plead guilty and subjecting persons to a known but discounted sanction where there is insufficient evidence to secure a conviction at trial.[119] In an analysis by a legal historian, Langbein analogised plea bargaining to medieval torture in Europe, both of which use coercion to obtain confessions of guilt and achieve ‘condemnation without adjudication’.[120] Yet the rhetorical force of the analogy overlooks the fact that plea bargaining may give rise to injustices on both sides of the ledger – when a penal outcome is bargained for, the accused may be subject to more, or less, punishment than is their just desert according to law.[121]

In Australia, the importance of guilty pleas to the criminal justice system cannot be gainsaid. What is less transparent is the role of plea bargaining in underpinning the high proportion of findings of ‘guilt’ in dispositions in criminal cases. Addressing that research gap, Flynn and Freiberg found that at least 87% of guilty pleas entered at all levels of Victorian courts were the result of a negotiated agreement between the prosecutor and the defence.[122] This does not reach the dizzying heights claimed of the US,[123] but nonetheless the criminal justice system would be unworkable if it routinely required trial in even a modest portion of that 87%.

An important contrast between the incentivisation that occurs in civil cases via litigation cost rules and in criminal cases via plea bargaining is their degree of formality. In civil cases, statutes give judges a formal role in managing civil litigation through tailored costs orders.[124] In criminal cases, plea bargaining occurs between defence and prosecution away from public oversight and without statutory or judicial regulation of the process.[125] This ‘behind closed doors’ approach has been facilitated by the High Court of Australia, which has assiduously kept the judiciary at arm’s length from the prosecutor’s decision as to what charges to lay and from the defendant’s decision as to how to plead.[126] In doing so, the cost-effective practice of plea bargaining runs headlong into other fundamental values of the justice system, including access to justice (especially for the least advantaged), fairness of process, impartiality of decision making, just outcomes according to merits and public confidence in the administration of justice.

The fifth process by which the state curbs demand for the courts is by filtering matters that are within the purview of the judicial system, with the objective of ensuring some matters do not proceed to determination or do not proceed further than is necessary. Filtration can be undertaken by different actors. In the first example considered below, lawyers are used to screen out civil cases that lack ‘reasonable prospects of success’, thereby leaving disputants without legal representation in less meritorious cases. This has an analogue in criminal cases, although only on the side of the Crown, where prosecutors must be satisfied there is sufficient evidence to prosecute a case and a ‘reasonable prospect’ of obtaining a conviction.[127] In the second example discussed below, judges are used to curtail appeals in civil and criminal matters by exercising their discretion to grant or refuse leave to appeal. There are other filters on the appellate process too, including the substantive rules that authorise appeals and the legal standard applied on review,[128] but these will not be canvassed here.

The gatekeeping functions discussed below are two illustrations of filtering, but there are other related instances. An important one is the use of case management in civil litigation. Traditionally, the adversarial system left the pace of litigation largely in the hands of the parties and their lawyers, with the judge assuming the reactive role of umpire.[129] Since the 1990s, however, ‘Australian courts have become more active in monitoring and managing the conduct and progress of cases before them, from the time a matter is lodged to finalisation’.[130] Effective case management requires coordinated effort from a variety of court personnel, but judges play a pivotal role in supervising proceedings to avoid ‘undue delay or unnecessary prolongation of trials’.[131] The High Court has endorsed this managerial role, strengthening the discretion of a trial judge to take into account ‘concerns of case management’ when making orders regarding the conduct of litigation.[132]

While case management does not necessarily reduce the number of civil matters lodged in the courts, it does aim to promote their timely resolution. It is therefore part of the state’s armoury of demand management tools, filtering cases out of the judicial system as efficiently as possible. Whether case management has delivered on that promise is a matter requiring empirical evaluation. Reporting in 2000, the Australian Law Reform Commission noted that the effectiveness of case management systems was largely untested in the federal judicial system regarding case duration, case outcomes, and costs.[133] More recently, in proposing a conceptual framework for measuring timeliness in civil justice, Economides, Haug and McIntyre suggested that case management is only one factor amongst many that affect the duration of legal proceedings.[134] They claimed that such institutional practices were commonly the focus of reform initiatives despite the absence of empirical support for their adoption or subsequent evaluation of their impact.[135] These issues do not need to be resolved here, but they demonstrate that judges can be participants in demand management in ways that reach beyond the two illustrations that follow.

1 Lawyers as Civil Gatekeepers

Despite the rise of self-represented litigants, many people who use the judicial system engage legal representatives to guide them because professional knowledge and experience enhance the prospect of a good outcome. By restricting access to legal representation, the state has been able to choke off some demand for the courts, albeit with adverse consequences for access to justice. These restrictions come in many forms, including the decline in public funding for litigation through legal aid[136] and restraints on lawyers’ advertising.[137] The focus here is on reforms requiring lawyers to assess the merits of civil cases before acting for clients, which co-opts lawyers as gatekeepers to the civil courts.

The context of these developments was the ‘civil liability crisis’ discussed in Part V(A). There was concern among parliamentarians that courts were being clogged by damages claims that were speculative in nature or based on hopeless contentions of law, and that cases were being prolonged by defences devoid of factual or legal merit.[138] Lawyers were seen to be part of the problem. Although lawyers have a paramount ethical duty to the court, which prevails over duties to clients,[139] the paramount duty was thought inadequate to the task of curbing civil litigation.

In 2002, the New South Wales Parliament enacted legislation to expand significantly the duties of lawyers in damages cases, in terms that have now been modelled in other jurisdictions and litigation contexts.[140] The crux of the change is that lawyers must not provide legal services on a claim for damages, or a defence to such a claim, unless they ‘reasonably believe ... on the basis of provable facts and a reasonably arguable view of the law that the claim or the defence ... has reasonable prospects of success’.[141] The sanctions for breaching the prohibition include disciplinary action for professional misconduct or a personal costs order against the lawyer.[142]

These provisions require lawyers to assess the merits of a case at the outset – before pleadings, argument or hearing – and to decline to act if the case fails to meet the requisite standard. In such a case, the disputant must decide whether to pursue the claim or defence without the benefit of legal services.[143] The chilling effect on litigation is the raison d’être of the provision, and experience in the US with a cognate provision in the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure suggests that it has that effect.[144] However, benefits to the administration of justice come at the cost of access to justice. There are many landmark cases that had ‘risky origins’, and there is a real danger that the provisions will reduce ‘the readiness of lawyers to assist with novel or difficult cases’.[145] Moreover, the decision to act for a client is made in private by a person who is subject to penalty if overzealous in taking on marginal cases. Those circumstances test the fairness and impartiality of the decision-making process and may weaken public trust in the justice system. If lawyers are to be co-opted as gatekeepers, there is an argument for an exception for public interest litigation, allowing a court to order continuation of a claim without a lawyer’s certification.

2 Judges as Appellate Gatekeepers

In 2019–20, Australian courts finalised 1.23 million matters, but only a tiny number (14,311, or 1.2%) were appeals.[146] What accounts for the small proportion of cases that percolate upward through the court hierarchy? Clearly, no judicial system could function effectively if every primary decision that a party wished to challenge was in fact reviewed by a higher court. The practical necessity for winnowing appeals is achieved in part through the discretion vested in judges to select the cases that may be taken on appeal.

Whenever statute authorises a court to grant leave to appeal, it gives the court a discretionary power to filter. The power is sometimes reposed in the court that made the original ruling, but more commonly, it is given to the court that will hear the full appeal if leave is granted. The discretion might be unstructured in its terms, and hence guided by common law principles that have evolved to control its exercise, or it may be structured by statutory criteria to which the court must or may have regard. The criteria for filtering cases are closely related to the justifications underlying the appellate process itself. Appeals serve two main goals – to supervise the exercise of judicial power by lower courts though the correction of errors and to develop the corpus of law through judicial exposition.[147] The error correction function predominates in intermediate courts of appeal, while the legal development function predominates in final courts of appeal, and this is reflected in the criteria for granting leave.[148]

This filtering can be seen in the High Court of Australia, which sits at the apex of the judicial hierarchy. With very few exceptions, appeals cannot be brought to the High Court without a grant of ‘special leave’. In determining an application for special leave, the Court is required to consider whether the case involves a question of law of public importance or on which lower courts have differences of opinion, or alternatively, that the interests of justice require the Court’s consideration of the matter ‘either generally or in the particular case’.[149] The last two words highlight the ‘tension between the Court’s law-making and adjudicative function’.[150] High Court justices have openly acknowledged that the provision was adopted to ‘winnow out those cases which are unworthy of its attention’, thus allowing better use of the Court’s resources.[151] The data bear this out. Figure 6 shows the number of special leave applications granted (solid line) relative to the number of applications filed (dashed line) over a 24-year period, yielding an average conversion rate of 12%.[152] The area between the two lines represents the extent of judicial winnowing.

Figure 6: High Court of Australia, special leave to appeal, 1996–97 to 2019–20[153]

It is evident that a court of seven justices can render only a finite number of reasoned decisions each year, and therefore any excess must be cast off. This impacts adversely on access to justice, but the way this is done gives minimal offence to other values of the justice system. There is a fair process involving oral or written submissions, impartial adjudication by appellate judges, just outcomes in the exercise of a structured statutory discretion and a high degree of public confidence in the process. This is to be expected because the power to filter is a power that must be exercised judicially.

The final process by which the state manages demand for the courts is by ‘pushing down’ matters within the court hierarchy so they can be disposed of more cheaply and efficiently in lower courts; a process that is here called demotion. Reallocating cases between court levels does not reduce the total demand for adjudication, but it allows demand for the most expensive parts of the system to be better regulated. Pushing down occurs in civil and criminal matters, but this section illustrates the phenomenon in two civil contexts. The first is the adjudication of family law disputes, where the solution has been a structural expansion by creating a new lower court; the second is the increase in the monetary limits of lower courts, where the solution has been one of jurisdictional expansion. The latter mechanism also has a counterpart in the criminal context where there has been a tendency to give magistrates’ courts jurisdiction to determine an ever-greater range of summary offences, as well as indictable offences triable summarily, when previously a defendant had to be tried on indictment in the higher district or supreme court.[154]

Jurisdiction in family law matters has undergone major restructuring over the past 50 years. Prior to 1975, family disputes were adjudicated in state courts, but in that year the Australian Parliament took over the field of family law in the exercise of its federal legislative powers. It created the Family Court of Australia as a specialist federal court with nationwide reach – except for Western Australia, where a state family court was established to administer the federal laws.[155] By 1999–2000, after 25 years of operation, the Family Court had a substantial caseload, with over 123,000 annual lodgements and hefty backlogs. However, from that year its caseload plummeted and it now attracts only one-sixth of the annual lodgements it received at its peak (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Family law lodgements, 1994–95 to 2019–20[156]

This precipitous decline is explained by the fact that in 1999 Parliament created another federal court – the Federal Circuit Court – to provide cheaper, simpler and faster methods of dealing with less complex civil matters.[157] The Circuit Court was intended to ease the workload of the Family Court and change the legal culture towards greater informality of proceedings.[158] To facilitate an appropriate allocation of cases between them, the Family Court and the Circuit Court were given power to transfer matters to each other on their own initiative and without notice to the parties. In relation to downward transfers, the Family Court was authorised to consider, inter alia, whether: the case could be dealt with faster, at less cost, and with more convenience if transferred to the Circuit Court; the financial value of the claim; and the complexity of the facts or legal issues involved.[159] The effect of the reform is evident in Figure 7. There was a rapid increase in lodgements in the Circuit Court in its first few years, which has now tapered off.[160] By 2008–09, the two courts appeared to have reached a stable equilibrium in which the structural changes introduced a decade before had eased the workload of the higher court.

However, as noted in Part I above, the Australian Government’s appetite for structural reform in family law disputes has not abated, and in 2021 the two courts were merged into a new entity called the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia.[161] As with earlier reforms, the changes have been justified by the government’s (disputed) claim that it would allow family law disputes to be ‘dealt with quickly, efficiently, cheaply and as safely as possible’.[162] It is telling that a significant fillip for the proposal was a commissioned report produced by an international accounting firm, whose assessment criteria included the cost of implementing the reforms, the ongoing operating cost of supporting the reforms and the potential efficiency gains for the courts.[163] In other words, a major focus was on the public fiscal benefits of structural change.

2 Expanding Jurisdictional Limits of Lower Courts

Demotion also occurs when legislation alters the relative jurisdictional limits of existing courts. In Australia, nearly all lower and intermediate courts have monetary limits on their civil jurisdiction. Over time, these limits have been raised in real terms, with the effect of extending the jurisdiction of the lowest tier relative to the intermediate tier and of the intermediate tier relative to the upper tier. This allows more civil matters to be commenced lower in the hierarchy, and plaintiffs are incentivised to do so by rules relating to court fees and legal costs.[164]

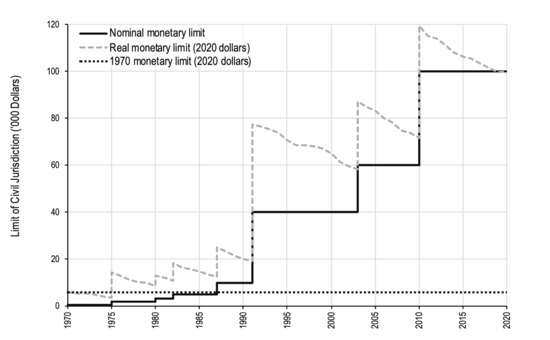

This can be illustrated using the Local Court of New South Wales, which is the lowest tier in that State’s judicial hierarchy. In 1970, its monetary limit on civil claims was $500, which is equivalent to $5,897 in ‘2020 dollars’.[165] However, the Local Court’s monetary limit today is $100,000 – 200 times the nominal value and 17 times the real value in 1970.[166] This has greatly expanded the range of civil matters falling within the Local Court’s jurisdiction.

The accretion of jurisdiction is shown in Figure 8. The nominal monetary limit is represented by the stepped line, which has increased on seven occasions since 1970 (solid line). Each nominal increase draws more jurisdiction to the Local Court, but the real benefit of the expansion is eroded by rising prices until the next nominal increase (dashed line). Despite this, there has been a marked increase in the Court’s real jurisdiction since 1970, represented by the area that lies between the dashed line and the dotted line (the latter being the real value in 2020 dollars of the 1970 limit of $500).

Legislatures have been candid in explaining the purpose of these periodic recalibrations. The Attorney-General justified one such change by the need for the State’s Supreme Court to be occupied solely with work of a complexity that comports with its status. He also emphasised that expanding the jurisdiction of the lowest court enhanced access to justice because it is cheaper and quicker for litigants to have their matters settled in that forum than higher up.[167] What is equally evident is that pushing matters down the court hierarchy is also cost-effective for governments that fund the courts.

Reviewing both the structural and jurisdictional mechanisms described above, it is apparent that pushing civil cases down the court hierarchy can make adjudication more cost-effective for the state and can promote access to justice for the disputants. Generally, it will do so without triggering undue concern about competing fundamental values because dispute resolution in lower courts must still be undertaken judicially. Taken to its limit, demotion might suggest that all cases should be determined in the lowest tier, but there is a point at which just outcomes may be jeopardised. Judicial officers at different levels of the hierarchy have different skills and experience; they also have different resources at hand with which to hear and determine cases before them. A rational system of justice must find a balance point that accommodates the complexity of matters and the capacities of adjudicators so that greater cost-effectiveness is not achieved at the expense of fair process or just outcomes. For the most part, however, that is an unlikely concern.

Figure 8: Monetary limits of the Local Court of New South Wales, 1970–2020[168]

VI CONCLUSION

The preceding discussion has significance for fundamental questions about the justice system – what role do courts play in resolving justiciable disputes, how has that role changed over time and how might it change in the future? An important conceptual contribution to the debate has been the ‘social development model’ of litigation.[169] Building on the work of French sociologist Émile Durkheim and American legal historian James Hurst,[170] this model sees legal institutions as responding to evolutionary changes in society, as it pursues a gradual but inexorable path of modernisation. In that process, the increasing volume and density of populations leads to greater opportunities for conflict as traditional social norms erode, which in turn requires an increasing role for legal institutions and is reflected in growing court caseloads.

Although there was a worrying ‘litigation explosion’ at one period in history,[171] Durkheim’s anticipated effects of modernisation in escalating court caseloads have not been manifested in recent times. As noted in Part II, Canada, the United Kingdom and the US have all faced a marked contemporary decline in court filings, at least in civil matters. This theoretically unexpected turn from the courts is also borne out by Australia’s experience. Examining 26 years of the Productivity Commission’s financial data, we saw that real expenditure on the courts has declined significantly relative to all other areas of government expenditure. Examining 21 years of Productivity Commission court lodgement data, we saw there has been a precipitous decline in civil matters commenced in Australian courts, both in absolute terms and per capita, while in criminal matters demand has been steady in absolute terms but has still declined significantly per capita.

The apparent contradiction between theory and praxis is largely explained by recognising that recourse to the law and recourse to the courts are not synonymous. In a now famous longitudinal study that interrogated Durkheim’s thesis in Spain, Toharia found a dramatic increase in legal activity (using notarised documents as an indicator) at the same time as stagnation in litigation rates.[172] A community’s need to resolve legal disputes does not have to be met solely by resort to the courts – some of those needs may go unmet and some may be resolved by other means. While there are very few studies of the legal needs of the Australian population,[173] the findings of Genn’s empirical research in the United Kingdom, Paths to Justice: What People Do and Think about Going to Law, is apposite: ‘When faced with a justiciable event most people simply want to solve the problem or obtain compensation for harm and loss.’ She concluded that ‘members of the public want routes that are quick, cheap, and relatively stress-free’ because ‘people want to get on with their lives as quickly as possible’.[174]

Where does this leave Australian courts? This article does not provide evidence of a decline in the aggregate legal needs of Australians, which would be a highly implausible (albeit empirically untested) outcome given the continued growth in population and real economic activity (by 43% and 110%, respectively) over the past 25 years.[175] However, it does suggest a declining role for the courts in meeting those legal needs. If courts may still be described as the ‘central suppliers of justice’,[176] the accuracy of the description is shakier than it was a generation ago because of unparalleled change to the arrangements by which justiciable disputes are resolved.

This article has argued that one of the key drivers of that transformation has been the pressure towards greater cost-effectiveness in the delivery of justice. This gained a foothold in Australia in the 1990s, with new sensibilities about public sector management, and it has continued without surcease. Those changes have not been an accident of history but part of a deliberate endeavour to confine judicial resolution of disputes to a minimal core. Although a variety of actors are now involved in giving effect to a transformed system (private lawyers, prosecutors, judges, public servants, etc), most of the fundamental changes have been policy initiatives of the executive, buttressed by legislative fiat. This can be seen in the statutory provisions underpinning abolition of rights to compensation, court-mandated ADR, expanded tribunal jurisdiction, CIN systems, certification of a case’s ‘reasonable prospects of success’, filtering of appeals, creation of new lower courts and expanded jurisdiction of lower courts. In each case, Hansard is replete with justifications based on the cost advantages (to users of the justice system and to the state) of the proposed reforms.

Attention to cost-effectiveness in the justice system is not to be denigrated. Speed and efficiency are vital qualities of a system of justice, encapsulated in the aphorism that justice delayed is justice denied. For utilitarians, cost-effectiveness has moral weight because public funds saved in one sector can be put to account in improving human welfare in others.[177] Governments therefore have had to think innovatively about their role in supporting the just resolution of social conflict. A common thread in that consideration is that courts are often said to be too slow and too expensive in achieving adjudicated outcomes, and this has built pressure to curb demand for their services.

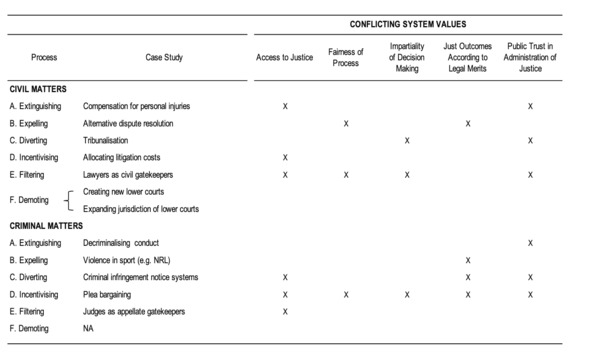

Yet greater cost-effectiveness may come at a price to other system values, such as access to justice, fair process, impartial decision making, just outcomes, and public trust. Using the Australian justice system as its context, this article analysed the processes by which the state tempers demand for justice in the courts and illustrated them by reference to case studies in civil and criminal matters. It also identified other system values that may be adversely affected by these demand tempering processes, as summarised in Figure 9.

Figure

9: Demand tempering processes and fundamental values of the justice

system[178]

Figure

9: Demand tempering processes and fundamental values of the justice

system[178]

As Figure 9 makes clear, reforms intended to make the justice sector more cost-effective can create new stresses at other points in the system. These stresses arise in four ways. They may arise because a legal need is no longer being met at all, or because it is being met privately outside the justice system, or because it is being met within the justice system but outside the judicial system, or because it is being met at a different point within the judicial system (such as in a lower court).