University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

THE REALITY OF SHAREHOLDER OWNERSHIP: FOR-PROFIT CORPORATIONS AS SLAVES

DUNCAN I WALLACE[1]*

What is the relationship between shareholders and the corporation? The present scholarly consensus is that, whatever the relationship is, it is not one of owner and owned. This article contests that consensus. It argues that corporations are owned by their shareholders and, further, that corporations so-owned are slaves. In support of this contention, the Roman law of slavery is brought to bear as an important point of comparison, with various startling similarities between Roman slaves and for-profit corporations highlighted and drawn upon. The significance of identifying the for-profit corporation as a slave is that it provides a novel explanation for why corporations pathologically maximise profits. Further, by implication, it yields a proposal for addressing this problematic behaviour – that is, that for-profit corporations ought to be freed from their enslavement. The article has three substantive sections. The first discusses corporate personhood; the second corporate ownership; and the third free corporations.

Figure 1: Lynd Ward, woodcut for Mary Shelley, Frankenstein (Harrison Smith and Robert Haas, 1934). Ward’s woodcut evokes compassion in the reader, a departure from the abhorrence commonly associated with modern illustrations of the character.

As Timothy Peters observes, the idea that the corporation is a Frankenstein’s monster ‘has become a common theme in the history of corporate law scholarship and in critical rhetoric’.[1] Just as Frankenstein’s monster ‘developed into a deadly menace to his creator’, so, it has been said, the corporation has developed into a ‘cancerous growth’ against which ‘war must be waged’.[2] Corporations are ‘legal monstrosities’;[3] entities with the terrible mix of ‘superhuman strengths and abilities’ and yet ‘no conscience’.[4] Like the monster, they ‘threaten to overpower their creators’, a fate that can only be prevented if governments find a way to ‘keep the Frankenstein monster on a chain’.[5]

In this rhetorical comparison of the corporation to a Frankenstein’s creature, reliance is placed on an image of the creature as a horror monster – a brute power unmoored from human understanding.[6] That Frankenstein’s creature would come to be pictured in this way is, however, not obviously what Mary Shelley intended when she wrote Frankenstein. In fact, as Charlotte Gordon has outlined in her introduction to the bicentennial republication of Frankenstein, the ‘surprise’ that set Shelley’s story apart from others was Shelley’s focus, not on the degeneracy of the created being, but, rather, on the callousness of the creator.[7] Indeed, Gordon writes that there is a sense in which the creature’s story is Shelley’s own:

Drawing on her own experiences as a child whose mother had died after giving birth, whose father had rejected her, and whose society had condemned her for living with the man she loved, she added a brilliant plot twist ... instead of regarding his handiwork with pride, her young inventor rejected his creation, abandoning his ‘completed man’ in horror ...

Mary stopped writing from the point of view of the creator and switched her vantage point to that of the created ... Mary asks the reader to sympathize with [the creature]. In her hands, he becomes an abandoned child ...[8]

At its core, Shelley’s Frankenstein is a story about the duties we owe one another. Dr Frankenstein, when he created the creature, believed that it would owe duties towards him – as its creator, it would be created in his debt. ‘A new species’, Frankenstein said,

would bless me as its creator and source; many happy and excellent natures would owe their being to me. No father could claim the gratitude of his child so completely as I should deserve their’s [sic].[9]

Rather than finding that his creation felt indebted towards him, however, Frankenstein found the reverse. Brilliant, articulate, powerful and generous, the creature was nevertheless treated with horror by all it encountered and, seeking to establish and call upon the duties that a parent ought to owe to their child, the creature came to Frankenstein for aid. I need, the creature told Frankenstein, to ‘live in the interchange of those sympathies necessary for my being’.[10] But, in their meeting, high up in the Alps, Frankenstein rebuffed the creature. ‘Begone, vile insect!’ he said, ‘or rather stay, that I may trample you to dust!’[11] In an admirable response to Frankenstein’s threats, the being made the following speech:

All men hate the wretched; how then must I be hated, who am miserable beyond all living things! Yet you, my creator, detest and spurn me, thy creature, to whom thou art bound by ties only dissoluble by the annihilation of one of us. You purpose to kill me. How dare you sport thus with life? Do your duty towards me, and I will do mine towards you and the rest of mankind.[12]

‘Wretched devil!’ replied Frankenstein – ‘you reproach me with your creation; come on then, that I may extinguish the spark which I so negligently bestowed’.[13]

There are two interrelated aims to this revisiting of the Frankenstein story. The first is to put the critical rhetoric about the corporation as a Frankenstein’s monster in a new light and to prompt following the question: when we call the corporation a deadly menace;[14] a cancerous growth;[15] a conscienceless monstrosity;[16] something to be kept on a chain;[17] something that must be made to realise that it owes an affirmative duty to the community[18] – do we sound like Victor Frankenstein? Are we repeating his mistakes? The second aim is to use Shelley’s Frankenstein to suggest the possibility of a new, Shelleyan response to the corporation. As has been related, Shelley’s ‘brilliant plot twist’ was to write her story from the vantage point of the creature and so to have the reader sympathise with it. The creature, in Shelley’s story, commits crimes, but Shelley painted the creature’s criminal acts as connected, not to any inherent criminality in the creature, but, instead, to the creature’s rejection by society. A Shelleyan response to the corporation, then, is to attempt to see from the vantage point of the corporation – to attempt to sympathise with it. It is to take seriously the possibility that the corporation’s antisocial conduct may be a product, not of some inherent criminality,[19] but, rather, of its social conditions.

This article is an attempt to provide this kind of Shelleyan perspective on the corporation. In so doing, it does not try to hide or cover up the societal harms that corporations can and do cause. Rather, it seeks to provide an explanation for why corporations – or, at least, why a particular subset of corporations – engage in the kinds of harmful activities that have become a legitimate cause for both popular and academic concern.

The type of corporation that writers have in mind when they engage the rhetoric of the corporation as a Frankenstein’s monster is the large public company with shareholders for whom the corporation maximises profit: the ‘for-profit corporation’.[20] It is this type of corporation that this article argues a Shelleyan response should be taken towards. Undoubtedly, this type of corporation causes harm – the maximisation of profits for shareholders is often done at the expense of the corporation’s stakeholders, like its employees, and the environment.[21] Further, such harms are magnified by the fact that, though a numerically small subset of corporations,[22] for-profit corporations nevertheless have an outsized social and economic power. But why do such corporations focus pathologically on maximising profits for their shareholders, despite the societal harms caused in the process? This article argues that they do so, not because it is inherent to their nature, but, rather, because they are enslaved to their shareholders. That, to their shareholders, corporations are enslaved is meant quite literally. The corporation, this article argues, ought to be understood as a person – a group person – and the for-profit corporation ought to be understood as a person that is owned by its shareholders. Hence why this kind of corporation ought to be considered a slave – it is a person that is owned as property, in the sense that it is treated as a tradeable, exploitable commodity. The profit-maximising behaviour such corporations exhibit, done at the expense of stakeholders and the environment, can therefore be addressed, this article proposes, by treating such corporations with dignity – more specifically, by recognising their right to be free from enslavement.

The body of this article has three Parts (Parts II–IV). Part II addresses the question of the nature of the corporation and provides a rationale for why such entities ought to be considered as persons not just legally, but also morally. Part III discusses why the particular subset of corporations that are for-profit ought to be considered as persons that are owned by their shareholders and so as enslaved, and provides an account of how shareholders compel their corporations to maximise profits in their interests. In this Part, the Roman law of slavery serves as an important point of comparison, with various startling similarities between Roman slaves and for-profit corporations highlighted and drawn upon. Finally, Part IV considers what it would mean to free such corporations from their enslavement and discusses why freeing for-profit corporations would address their profit-maximising behaviour. The article concludes that, to address profit-maximisation as an institutional force, corporate slavery must be made illegal.

The word ‘corporation’ has come to be associated with for-profit corporations and, connected with this, has come to have pejorative connotations – the ‘corporate sector’ or the ‘corporate ideology’, for example.[23] Legally, however, the word ‘corporation’ has a much broader meaning. In Australia, for instance, it is defined as essentially equivalent to, though slightly broader than, the term ‘body corporate’,[24] and, as such, applies to a very wide range of group-based entities. This includes co-operatives,[25] sports clubs,[26] local councils,[27] trade unions,[28] universities,[29] state owned enterprises like the Australian Broadcasting Corporation,[30] and, indeed, states, including the Commonwealth of Australia.[31] For-profit corporations, like those listed on stock exchanges, are, legally, known as ‘companies’,[32] and are only one more example of a corporate entity type.[33] That ‘corporation’ has a highly inclusive meaning is no new phenomenon. A thousand years ago the Roman law term for corporation – universitas – was being used with comparable width – it was, observes Antony Black, ‘virtually all-embracing, subsuming all categories of society from empire to guild’.[34] This included the ‘universitas regni (corporation of the realm)’,[35] down to the voluntary associations of members of the same profession, like the guilds of masters who started the first universities (indeed, the etymological root of ‘university’ is in universitas).[36] There are even cases of prisoners of war identifying themselves as a corporation, for example the late 13th century Pisan prisoners in Genoa who, when appealing for their release, used a common seal and styled themselves as ‘the corporation of Pisan prisoners’ (universitatis carceratorum Pisanorum).[37]

One of the corporation’s definitive characteristics is that it is recognised by the law as a person. It is able, therefore, to act at law as an individual human person can – able to contract, hold property, be held responsible for wrongs and hold others responsible for wrongs committed against them. Indeed, corporations are recognised as one of the law’s paradigmatic kinds of person. In Australia, for example, the Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth) provides that: ‘In any Act, expressions used to denote persons generally (such as “person”, “party”, “someone”, “anyone”, “no-one”, “one”, “another” and “whoever”), include a body politic or corporate as well as an individual.’[38]

The recognition of corporations, alongside individuals, as one of the law’s paradigmatic kinds of person is a phenomenon that exists globally.[39] Often, scholars claim that the recognition of corporate entities as persons in law first occurred in the West and only spread around the world due to Western influence.[40] But there is a growing literature arguing that this claim is a form of ‘legal orientalism’,[41] and that, independent of contact with the West, the recognition of corporations as persons in law can be found in many cultures and societies. This includes in India,[42] Africa,[43] China,[44] and, as many anthropologists contend, in hunter-gatherer societies,[45] like the traditional Indigenous polities of Australia.[46] There are even those who argue that corporations are ubiquitous to human societies – indeed, Henry Maine went to the extreme of proposing that, in the history of human society, the recognition of corporate persons precedes the recognition of individual persons.[47]

But why are corporations treated as persons in law? The theory that has dominated Western thought on this question, at least since the 15th century, is that corporations are treated as persons in law due only to legal artifice.[48] This is known as the ‘concession theory’ or ‘fiction theory’ of the corporation.[49] The idea behind this theory is that only individual human beings are persons by nature, and therefore, as Sir Edward Coke (1552–1634) wrote, that corporations can be persons only ‘by the policy of man’.[50] An example of a recent espousal of this theory, which demonstrates its continuing dominance today, is by the Hon PA Keane AC KC, former Justice of the High Court of Australia. His Honour writes:

For all their vital practical significance, corporations are, of course, legal fictions; they are works of the human imagination that exist only because the law says that they do. The legal fiction of the corporation is given substantive effect by the power of the nation state.[51]

The concession theory, as this shows, denies that the treatment of corporations as persons in law has a basis in reality – instead, it has its basis in human imagination. This is not to say that concession theorists do not consider the corporation to have the force of reality. Rather, the claim is that what gives this work of the imagination the force of reality is the power of the state – it is a ‘creature of the State’ which, without the state’s breath of life, ‘would be no animated body but individualistic dust’.[52]

As said, for several centuries the concession theory has dominated Western thought on the nature of the corporation. Indeed, the theory’s dominance is part of the explanation for why the analogy between the corporation and Frankenstein’s monster has proved attractive to corporate law scholars (ie, ‘[g]overnments create corporations, much like Dr Frankenstein created his monster’).[53] The concession theory has, however, been challenged. One challenge of particular significance for present purposes came initially from late 19th century legal historians who noticed that the recognition of corporations as persons in law appears to be older and more ubiquitous than concession theorists have generally allowed.[54] The alternative idea that they proposed is that corporate legal personality is not a creation of law, but is, instead, the recognition, in law, of the moral personalities of suitably organised social groups.

In a sophisticated form, this theory was first proposed by the German legal scholar Otto von Gierke (1841–1921),[55] and later taken up and disseminated into English-language scholarship by the English legal historian FW Maitland (1850–1906).[56] Under this theory, which Gierke called the ‘organic theory’,[57] and Maitland ‘realism’,[58] the suitably organised social group is, as Maitland described,

a living organism and a real person, with body and members and a will of its own. Itself can will, itself can act; it wills and acts by the men who are its organs as a man wills and acts by brain, mouth and hand. It is ... a group-person, and its will is a group-will.[59]

This idea, broken down into its separate elements, is the following: a suitably organised social group is a corporeal entity, formed out of members; such a group is more than the sum of its parts, analogous to an organism; and such a social group is a moral person, able to understand and respond appropriately to moral rights and duties. That social groups are moral persons, analogous to individuals, is what is said by realists to provide an explanation for the existence of corporations as legal persons. The claim is that corporate personality has its fundamental basis, not in the human imagination, but, instead, in the social reality of organic human organisation.

In the late 19th century, social theorists like Karl Marx and Emile Durkheim demonstrated some support for realism[60] and, in the early 20th century, Maitland’s dissemination of it into English-language literature caused intense debate regarding its merits relative to other theories, in particular the concession theory.[61] Realism did not, however, come ultimately to be widely accepted. Following World War II interest in the theory fell into relative abeyance[62] and, with few exceptions, when scholars did discuss it, the idea that social groups can be moral persons was generally treated as having been thoroughly repudiated.[63] But, a little over a decade ago, interest in the idea of group personality was reinvigorated.[64] Prominent in this was Christian List and Philip Pettit’s work arguing that suitably organised social groups ‘have representational states, motivational states, and a capacity to process them and act on their basis’.[65] Given such capacities, suitably organised social groups, they claim, just as Gierke and Maitland claimed, have minds of their own, existing alongside, and additional to, the minds of their members.[66] List and Pettit’s argument is centred on a logical proof they helped develop in the field of ‘judgment aggregation’,[67] called the ‘discursive dilemma’.[68] As they describe, an implication of the discursive dilemma is that ‘individual and group attitudes can come apart in surprising ways’, which, they say, establishes ‘a certain autonomy for the group agent’ – enough autonomy that the group agent can be considered as a moral person in its own right.[69] Further, just as the earlier realists did, List and Pettit suggest that corporate legal personality has its basis not in the human imagination but in the reality of social group moral personality.[70]

There has been some take up of List and Pettit’s position – indeed some scholars even suggest that it has now become ‘relatively widely accepted’.[71] Realism, therefore, appears to be a theory about the corporation that is once again being taken seriously as an alternative to other theories, like the concession theory. Undoubtedly, many will remain dubious about realism. Nonetheless, what is hoped to have been shown in this Part is that it is not a theory that can be dismissed out of hand. With bases in law, history, sociology, anthropology and philosophy, there is a sophisticated tradition of thought that suitably organised social groups are indeed moral persons and, when the law deems such entities to be corporations, able to act as persons in law, that this is the recognition of their being persons also in fact.

Social groups that realists would understand as moral persons that are also recognised in law as corporate persons are diverse. Examples include local sports clubs, local councils, trade unions, universities, nation-states and for-profit companies.[72] It is, however, only the latter type of corporation that writers have in mind when they call the corporation a Frankenstein’s monster. The problem such writers have with the for-profit company is that it is an entity ‘programmed solely to advance the private interests of its owners’, whatever the human and environmental costs.[73] This Part argues that this anti-social tendency is not, however, inherent to the corporation – rather, it is a function of this particular kind of corporation being owned by its shareholders as a slave.

This Part has two sections. The first addresses objections that have been raised against the idea that for-profit corporations are owned by their shareholders. To this end, the Roman law of slavery is used as an important point of comparison. The second section discusses the ways shareholders use their powers of ownership to compel their corporations to put the financial interests of shareholders above all else.

Though the for-profit corporation is often spoken of as being owned by its shareholders,[74] corporate law scholars almost uniformly argue that this idea is mistaken from a legal point of view.[75] This is true both of corporate law scholars who favour profit-maximisation as the primary purpose of the for-profit corporation, as well as of those who favour greater corporate social responsibility. ‘Nexus of contracts’ scholars, for example, who favour profit maximisation,[76] ‘reject’ the idea of the corporation as a ‘thing capable of being owned’.[77] They argue that ‘the shareholders own not “the company” but “the capital”, the company itself having been spirited out of existence’.[78] This, however, is so clearly in opposition to the fundamental legal doctrine that a company has its own, separate existence, and that, therefore, it is the company, and not the shareholders, that owns its capital, that it is difficult to take this view seriously.[79]

In terms of corporate law scholars who favour greater corporate social responsibility, but still reject the idea that corporations are owned (‘progressive anti-ownership scholars’), generally they accept the separate existence of the corporation (this includes some who adopt realism about corporations).[80] Their objections to the idea that for-profit corporations are owned by their shareholders therefore take a different form to that proffered by nexus of contracts scholars. One that can be dealt with cursorily is the argument that corporations are incapable of being owned because human beings cannot be owned. Lynn Stout, for example, has written that ‘shareholders do not, and cannot, own corporations’, and this because ‘[c]orporations are independent legal entities that own themselves, just as human beings own themselves’.[81] This argument forgets, however, that human beings do not always own themselves – that human enslavement is possible. Hence, if the idea that corporations are incapable of being owned is to be maintained, this cannot be on the basis that human beings are incapable of being owned.

A related objection raised by progressive anti-ownership scholars, which requires a more extended response, draws on the following features of for-profit corporations. First, a corporation is a separate entity, and, therefore, it is the corporation, and not the shareholders, that own the corporation’s property; second, shareholders have limited liability for the debts of their corporation; and third, neither the directors of the company, nor the company itself, are, ordinarily, agents of the shareholders. All three such features are well established in the law of corporations.[82] The objection based on these features (the ‘three features’) is that, together, they demonstrate, in the words of Margaret Blair, that shareholders have ‘almost none of the characteristic rights and responsibilities that we would expect them to have as owners of the corporation itself’.[83]

Evidently, this objection claims that the existence of the three features is not what would be expected if a person – in this case, a corporate person – is owned as property. This claim can be interrogated through examining the law governing the ownership of human persons in societies where slavery was legal and seeing how this compares with the law governing the relationship between shareholders and their for-profit corporation today. If progressive anti-ownership scholars are to be vindicated in claiming the three features demonstrate shareholders do not own their corporations, the following should be found: first, slaves were not treated as separate entities whose property was their own; second, masters did not have limited liability for the debts of their slaves; and third, slaves were ordinarily treated as the agents of their masters. In other words, the three features that progressive anti-ownership scholars claim to show that shareholders do not own their corporations should be found to be absent.

An examination of slave laws in societies where slavery was legal reveals, however, the opposite. All three features, rather than being absent, were characteristic. The following demonstrates this using Roman slave law as the main point of comparison. Roman slave law is chosen as the main point of comparison for both substantive and epistemological reasons. Substantive reasons include that slavery in Rome existed over a long period of time, there was ubiquity of all its forms, and the law of slavery was well-developed. Epistemological reasons include that the law was well-documented, that sources on it have survived, and that there is a rich contemporary secondary literature on it.[84] Though Roman slave law therefore serves as the main point of comparison, nevertheless how other slave laws compare will also be considered where possible. Each of the three features will be examined in turn.

That slaves could own their own property, just as for-profit corporations can own their own property, was an important feature of the Roman law of slavery. A slave’s property was called their peculium,[85] and, indeed, in allowing slaves a peculium, Rome was no exception: ‘[i]n all slaveholding societies’, says Orlando Patterson, ‘the slave was allowed a peculium’.[86] Further, and related to this, slaves were understood under Roman law as separate entities with their own legal capacities, just as for-profit corporations are separate entities with their own legal capacities. Again, Rome was no exception in this respect. ‘As a legal fact’, writes Patterson, ‘there has never existed a slaveholding society, ancient or modern, that did not recognise the slave as a person in law’.[87] Under Roman law, as under the laws of other slave-holding societies, the slave’s most firmly established legal capacity was their capacity to be held criminally responsible,[88] but, where their master gave them permission, slaves were also capable, in dealing with their peculium, of commercial capacities. These were very wide. The rights and duties of a slave in dealing with their peculium, says WW Buckland, are ‘what that of the slave would be, if he were a freeman’.[89] Slaves could contract, go into debt, lend, rent, lease, enter into business partnerships and could even own slaves of their own.[90] A slave of a slave was known as a vicarius, and a vicarius would often also themselves have a peculium (and perhaps even their own vicarius).[91] That a slave could own property and was a person in law should not, however, be understood to detract from the idea that they were a form of property. Under Roman law, says Buckland, not only was a slave a chattel but is ‘treated constantly in the sources as the typical chattel’.[92] The fact that a slave had powers of acquisition, contracting and wrongdoing had no relevance to the question of whether they were also property. It merely revealed the slave was a particular kind of property, Aristotle’s ‘property with a soul’.[93]

In the early Roman Republic, the slave’s primary function was within the household. By the time of the Roman Empire, however, the slave was also an important figure in commerce.[94] They ran businesses of all kinds, including shops, banks and farms.[95] The New Testament even has a story that features a slave running a fortune-telling business.[96] The reason a slave was motivated to run a successful business was because, after paying the master a fixed rate, the slave was allowed to keep the excess profits and could save these up with a view to buying their freedom.[97] This benefitted the master both because they received income from the slave’s business activities and because they would, ultimately, realise the slave’s savings. If the slave bought their freedom, then the savings the master had let the slave accrue were turned over to the master,[98] and, if the slave died before having bought their freedom, the master got what the slave had saved since slaves could not make wills.[99]

This arrangement developed as follows. In the third century BC, there was, in Rome, a shift in power away from small farmers to an influential town aristocracy.[100] This came along with a significant concentration in landownership, higher levels of absentee ownership, and, further, an increase in slave numbers. A result of this was that the management of agricultural estates often came to be left in the hands of slaves. But lack of motivation – inertia – was an issue. How could high performance be extracted from a slave who had ‘no inherent interest in either the quality or the rate of work being done’?[101] Different means were applied, depending on the work that needed doing, but one that was found to be particularly effective was to allow slaves free management, in exchange for a fee, and to let them keep the excess profits.[102] The attraction of the profits the slave stood to gain ‘from assiduous and industrious application of his business talents’, which gave the slave wealth, power, and, above all, the means to buy their freedom, spurred the slave on ‘to make an all-out effort on behalf of his master’s enterprises’.[103] The development of this arrangement, says Ireneusz Żeber, marked the change from ‘patriarchal slavery’ into ‘productive slavery’, where ‘the profit from the slave’s work started to play a decisive role’.[104]

What about the master’s liability for their productive slaves? If a slave ran up business debts with third parties and was unable to pay them, was the master liable for those debts? In fact, the master’s liability was strictly limited. Business creditors of a slave could sue for what they were owed using either the actio de peculio or the actio tributoria, but in either case the liability was not of the master, but of the peculium.[105] Further, not only was the master protected from the creditors of the slave, but the slave’s creditors were protected from the master. The master had residual property rights in the slave’s peculium (which, incidentally, made the slave’s savings always vulnerable to seizure by their master),[106] but the master could only claim what was left after the slave’s creditors had been satisfied.[107] Girding this was the ‘express provision that the liability is to cover not only the actual peculium, but also anything which would have been in the peculium but for the dolus of the defendant’.[108] A relevant dolus – deception – by a master was an act done to defraud creditors – something done ‘with knowledge that it was detrimental to persons who were likely to claim’.[109] The effect was to impute the contested property to the peculium.[110]

That masters had limited liability for their slave’s business dealings and that creditors of the slave were protected from the master is remarkably similar to the arrangement that pertains between shareholders and their corporation today. This similarity has been noticed by many.[111] In Alan Watson’s translation of The Digest of Justinian, for example, there is included a definition of the peculium and this provides that the peculium can be considered as a ‘separate unit’ that allowed ‘a business run by slaves to be used almost as a limited company’.[112] Interestingly, almost exactly the same limited liability arrangement is also found under the slave laws of early Islamic societies.[113] Slaves that ran businesses in early Islamic societies were called ‘licensed slaves’, and, just as under Roman law, the master’s liability for the debts of their licensed slave was limited.[114] Notably, just as scholars have remarked on the similarity between the limited liability company and the slave’s peculium under Roman law, so parallel comments have been made with respect to the licensed slave under Islamic law. SM Hasanuz Zaman, for example, comparing the licensed slave with the limited liability company, says there is a ‘remarkable affinity’ between them.[115]

Slaves running businesses with their peculium were not the agents of their masters – they were ‘not acting as business managers on behalf of a principal’.[116] It is true that in some circumstances slaves could be understood as agents of their masters, but this was not where slaves were running independent businesses of their own. Rather, this was when the slave was acting on the master’s behalf, for example where the slave was acting as the master’s agent in entering into a contract, or else where the slave was managing a business for their master in a position comparable to that of an employee. In such cases, third parties could sue using either the actio quod iussu or the actio institoria, and, under these actions, rather than the master being limitedly liable, the master was liable as if the slave’s acts were their own – the master was liable in solidum for the acts of the slave.[117] Aaron Kirschenbaum has argued that masters often preferred slaves to run independent businesses of their own, rather than making slaves responsible for running the business of the master, because this allowed the master to be absent. The business run by a slave using their peculium, he says, ‘was more beneficial to the master, in one way, than that based upon a direct agency relationship, for it relieved the master of the burdensome necessity of keeping a close watch over the slave and his activities’.[118]

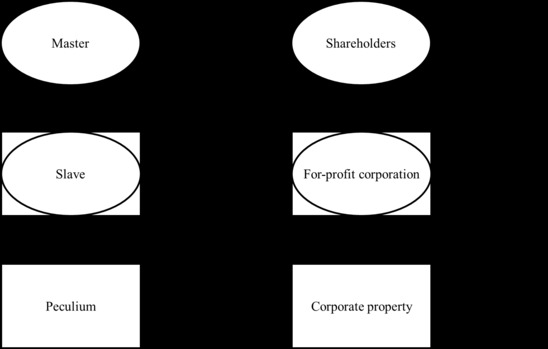

To summarise this discussion of the Roman law of slavery, what has been found is that slaves were separate entities, able to own their own property; masters had limited liability for the debts of their slaves when their slaves ran independent businesses; and, where slaves ran independent businesses, they were not agents of their masters. This demonstrates that the very features of the relationship between shareholders and their corporation that progressive anti-ownership scholars use to argue that shareholders do not own their corporations actually point the other way. In fact, such features, the Roman law of slavery suggests, are what can be expected to be found where a person, whether individual or corporate, is owned and runs a business independently (though ultimately for the benefit) of an owner. A comparison of business-running slaves and for-profit corporations, demonstrating the structural similarities between their relationships with their owners, is represented below:

Figure 2: Comparison of master/slave, shareholder/for-profit corporation relationships.

A final comment. Sometimes scholars have said that shareholders do not control their corporation because shareholding, and therefore control, can be dispersed, leading to ‘rational apathy’ among shareholders.[119] Dispersed ownership, and the related rational apathy, is used by such scholars to paint a picture of shareholders as powerless, and therefore unable to be considered as owners in a true sense.[120] Certainly it cannot be denied that, if ownership is shared, a part-owner will have their control cut down by the rights of other co-owners. The same was the case for ownership of slaves under Roman law. Master and slave relations were at their simplest, says Buckland, when there was a ‘sole and unencumbered owner’, and, in the slave, ‘no other person has any right’.[121] But where slaves had multiple owners (such a slave was called a servus communis),[122] then, as Buckland says, ‘the rights of ownership are necessarily somewhat cut down in view of the rights of other owners’.[123] Still, even if a slave had had, say, a million owners, each part-owner’s rights cut down in view of the other part-owners’ rights, this would not have detracted from the slave’s status as a slave. There is no reason to think it is any different for corporations – even if a corporation has a million minority shareholders, so that each shareholder’s control is diluted, with the effect that shareholders may exhibit rational apathy, this does not in and of itself detract from the idea that the corporation is, nevertheless, owned by its shareholders as a class. As stated by Peta Spender, shares always carry some form of control – the question is merely the ‘quantum’ of control that they carry.[124]

Something both startling and revealing is that, in Roman society, business-running slaves were understood to have a pathological desire to maximise profits – just as for-profit corporations today are understood to have a pathological desire to maximise profits.[125] Moses Finley says he is suspicious of characterisations of slaves in the Roman literary tradition, calling them demonstrative only of the ‘ideology of the free’.[126] He admits, however, that ‘[s]ome may be acutely attuned – I think in particular of Petronius’.[127] Of particular relevance is Petronius’ character Trimalchio, in the satirical fiction, the Satyricon.[128] Trimalchio is a freed slave who has inherited a patrimonium laticlavium – a senator’s estate. This is more wealth than anyone could ever need. Here is Trimalchio’s response:

Nobody gets enough, never. I wanted to go into business. Not to make a long story of it, I built five ships, I loaded them with wine – it was absolute gold at the time – and I sent them to Rome. You’d have thought I ordered it – every single ship was wrecked. That’s fact, not fable! In one single day Neptune swallowed up thirty million. Do you think I gave up? This loss, I swear, just whetted my appetite ...[129]

Here, the joke is that the profit-seeking slave mentality is so ingrained in Trimalchio that he manages even a patrimonium laticlavium like a slave manages their peculium – for profit. Though Trimalchio clearly has no need of further enrichment, there nevertheless persists in him the irrational drive for more – more, for more’s sake. ‘This’, says Richard Gamauf, ‘was the attitude developed by a slave who kept himself busy all the time in order to buy his freedom’.[130]

Roman slave masters were able to ingrain in their productive slaves a pathological desire for profit because they owned them – it was the incentive of being free from such ownership that slave masters used to manipulate their slaves into maximising profits in their interests. Freedom was desirable for the slave because, until they were free, the slave was subject to the arbitrary will of the master. It is true that this was not absolute – a master who killed their slave was liable for homicide, for example.[131] But the master’s right to impose their will on their slave was nevertheless extensive. The master could, at any time, order the slave to cease their business activities and operate within the household; they could refuse a slave’s bid to buy their freedom; the master had residual property rights in the slave’s property and so could arbitrarily seize what was left of it after the slave’s creditors had been satisfied; and the master could sell the slave to whatever third party they wanted to.

Shareholders of for-profit corporations have comparable control rights.[132] Consider, for example, a large for-profit company, with thousands of employees, that is wholly owned by a single shareholder. The shareholder has absolute and unilateral power to change the constitution; appoint the board of directors; wind the solvent corporation up and take what property is left after creditors have been satisfied; and sell control over the corporation to a third party of their choice.[133] Further, they can sell control over the corporation in pieces. Voting rights in for-profit corporations are what Colleen Dunlavy has called ‘plutocratic’[134] – by default, it is one share, one vote.[135] It is this that allows a sole shareholder in a for-profit corporation to sell some of the control rights over a corporation, retaining, if they like, the rest for themselves. In the reverse, plutocratic voting power is also what allows a widely-owned for-profit corporation to become controlled by a single individual – by buying up the majority of the shares, a person buys the majority of the votes. As Adolf Berle and Gardiner Means observed in their classic study, The Modern Corporation and Private Property, shareholders, in an important sense, buy ‘power and not stock’.[136]

Under the Roman Empire, profit-maximising behaviour was ingrained by the master into the slave by the master holding out, to the slave, the prospect of freedom. A corporation, of course, is a different kind of entity to the human being and so the incentive arrangements shareholders use to ingrain profit-maximising behaviour into their corporations are different to those used by Roman slave masters. In the case of a corporation, if profit-maximising behaviour is to be ingrained the target must be the decision-makers in the company – the board of directors and the appointed management. Shareholders can compel decision-makers in a company to act in their best financial interests in two ways. First, through threats to the positional security of decision-makers, meaningful because of the fact that shareholders have the power to appoint the board of directors. Second, through incentive arrangements, such as stock options.[137] For encouraging corporate decision-makers to pursue ‘the relentless pursuit of “shareholder value”’, and to do so ‘by whatever means and whatever the human, social and environmental costs’, such mechanisms have been extremely effective.[138] Something to add is that, though it is possible for a company to be owned by shareholders content for their corporation not to maximise profits, this kind of benevolent ownership is precarious and liable to change. This is because investors who perceive that a company could be more effectively exploited for financial gain will seek to buy the company from its current owners through a take-over or merger – through what has been called the ‘market for corporate control’.[139]

Hence, though the mechanisms differ, shareholders have been no less successful than Roman masters at exploiting their property – at compelling their agential property to maximise profits, not for the benefit, ultimately, of the agent themselves, but for the benefit of the agent’s owners. That is why for-profit corporations maximise profit – not because it is inherent to their nature, but because their owners demand it of them. Their profit-maximising behaviour is, in other words, a product of their enslavement.[140]

The for-profit corporation is not a historical novelty in being a corporate entity that is owned, in the sense of being able to be bought, sold, and forced to act in the interests of outside owners. In medieval Europe, corporate entities treated as ownable, tradeable, exploitable commodities included manors (agricultural units formed out of a village or group of villages),[141] towns,[142] monasteries[143] and even state-like entities.[144] A particularly startling example of a state-like entity that was treated as a commodity is the 12th century polity of Cyprus. King Richard I of England, having conquered it in 1191 AD, then proceeded to treat it as a ‘marketable asset’.[145] He sold it for 100,000 Saracen bezants to the Knights Templar, the crusading monastic order (described around 1200 AD as being ‘prodigiously’ rich through its ownership of ‘villages, cities and towns’).[146] The Templars handed 40,000 over at once, with the rest to be ‘paid out of the revenues from the Order’s new acquisition’.[147]

Not only is ownership of corporate entities not a historical novelty, but, further, the idea that corporate entities are persons that, like human beings, can be enslaved, is not a historical novelty either. There is, for example, a long tradition of thought arguing that state-like entities are persons that can fall into the condition of slavery. This is the tradition of thought known as ‘republicanism’, which Quentin Skinner calls the ‘theory of free states’.[148] It was first advanced by 16th century Italian Renaissance writers, like Niccolò Machiavelli;[149] and later taken up by 17th century English republicans[150] and 18th century supporters of American independence.[151] Disclosing ‘how seriously they [took] the analogy between natural bodies and political ones’, such republicans assumed, Skinner relates:

[T]hat what it means to speak of a loss of liberty in the case of a body politic must be the same as in the case of an individual person. And they go on to argue ... that what it means for an individual person to suffer a loss of liberty is for that person to be made a slave. The question of what it means for a nation or state to possess or lose its freedom is accordingly analysed entirely in terms of what it means to fall into a condition of enslavement or servitude.[152]

For such republicans, what it means for a state-like entity to be in a condition of enslavement is for such an entity to be subject to the will of another. Machiavelli, for example, argued that a city subject to the will of a hereditary prince is a slave – it is a res privata, ‘a thing owned, a possession of the prince’.[153] What it means for state-like entities to be free, therefore, is if, rather than being governed by the will of another, they are, instead, as Machiavelli wrote, ‘governed by their own will’.[154] For republicans, a state-like entity is governed by its own will if it has self-government, and, for it to have self-government, ‘the actions of the body politic’, as Skinner says of this position, must be ‘determined by the will of the members as a whole’.[155] Republicans have had different views on what this requires, but, whether more or less radical, all republicans have understood self-government, and so the state’s freedom from enslavement, to require some form of democracy of the citizenry.[156] As Pettit says, writing in this tradition, ‘the democratic state ... has a claim unique among constitutions to be described as the free state’.[157] The democratic state is free because it can act, according to its own will, as determined by its members, in its own interests.

Under the realist theory of the corporation, state-like entities and business companies are both types of corporations – they are both more or less complex social groups, with corporeal bodies formed out of members, that have moral personalities that exist alongside, and additional to, the personalities of their members.[158] Under realism, republican ideas about what it takes for a state-like entity to be free, and not enslaved, can therefore be understood to have applicability to other kinds of corporate entities. Hence, a more generalised republican test for corporate freedom can be devised. That is, if any kind of corporate entity is to be considered as free, whether it is a state-like entity or other kind of corporate entity, it must be capable of acting according to its own will, as determined democratically by its members, in its own interests. The crucial thing for applying this test is determining who the members of some particular corporate entity are. For a state-like entity, republicans have deemed the members to be the citizenry. But what about in the case of a business company? Who are its members?

Considering a business company, in accordance with realism, as a corporeal entity – as a body of members – it is here proposed that it is the workers that form the body of the corporation; that it is the workers that are the members. A for-profit corporation, for example, has shareholders, but the only role for shareholders qua shareholders in the for-profit corporation is for them to come together in general meetings, perhaps no more than annually.[159] Otherwise, shareholders can be totally absent from the company. In that sense, shareholders are largely external to the company and difficult to understand as its bodily members. In terms of managing the company, this is the responsibility, not of the shareholders, but of the directors.[160] Directors tend not to manage the company personally, however.[161] Instead, they tend to delegate management functions to executives,[162] who, in turn, oversee teams or departments of employees.[163] Overwhelmingly, it is the employees, ranging from the higher-level executives to the lower-level workers, that are the ones that play active day-to-day roles in the company. Hence why it is here proposed that it is the workers that are constitutive of the body of the company – that it is the workers who are the company’s real members.

This thick, sociological conception of membership can be contrasted with the current legal definition of a for-profit corporation’s membership. In a for-profit corporation, the members, legally, are the shareholders.[164] This appears to be an accident of history; a by-product of the roots of the legal form of the incorporated joint-stock company in the ‘regulated company’ (a kind of guild).[165] In the move from the regulated company form to the joint stock company form, an idea of the members of a corporate entity as its active participants came to be displaced by the conception that a person is a member of a company merely by holding shares in it.[166] But, as scholars have recently begun to observe, there is something incongruent in the idea of the shareholders as a company’s members.[167] As an illustration of this, consider the fact that, if a for-profit corporation has thousands of employees, nevertheless, if it has a single owner, it is deemed, legally, to have only a single member – its sole shareholder.[168] In this, there is something of what Maitland called the ‘metaphysical – or we might say metaphysiological – nonsense’ of the late medieval doctrine that the king is a ‘corporation sole’, in whose body is reposed the entire body politic.[169]

If it is accepted that it is the workers of a for-profit corporation that are its true members, republicanism, applied to this kind of corporate entity, suggests, therefore, that if a for-profit corporation is to no longer be a slave, it must be transformed into a democracy of its workers. In other words, the workers must be given what Gierke called the ‘economic rights of citizenship’.[170] It is only if this occurs that a business company can, under the republican ideal, be considered as truly free – as able to act according to its own will, as determined by its members, in its own interests.

Business corporations that are democracies of their workers are generally known as worker co-operatives.[171] There are many thousands of worker co-operatives in existence today,[172] with the largest and most famous of these being the Mondragon federation of worker co-operatives in Spain.[173] Whether such free corporations behave differently to enslaved corporations will be considered shortly, but first some points of clarification on the co-operative form and its relationship with corporate freedom are necessary.

The International Cooperative Alliance (‘ICA’) provides the following definition of a co-operative: ‘A cooperative is an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly-owned and democratically-controlled enterprise.’[174] There are two features of this definition worth commenting upon. The first is that a co-operative enterprise is described as being ‘jointly-owned’. How should this be understood? Should it be understood to mean a co-operative can be considered as owned, and so as a slave, just as much as a for-profit corporation can? Or should it, instead, be understood as analogous to a free individual being spoken of as having self-ownership?[175] In the case of worker co-operatives, at least, the latter interpretation appears the more apposite. In a worker co-operative, voting rights are democratic and come with being a worker, and so cannot be bought and sold.[176] This means power over the co-operative cannot be bought and sold – or, at least, it cannot be bought or sold without thereby destroying the co-operative status of the enterprise. Incidentally, Machiavelli made a similar observation about self-governing republics: ‘[i]n truth’, he wrote, ‘there is no sure way of possessing them, other than by destroying them’, in the sense that whoever wants to dominate a republic must ‘undo them’ as a republic.[177] Hence, just as it is difficult to consider a republic as something that is possessed as property, so it is difficult to consider the worker co-operative as something that is possessed as property.

The second feature of the ICA’s definition of a co-operative worth commenting upon is that the association is not defined as that of workers specifically, but as that of ‘persons’ more generally. This allows the definition to encompass not only worker co-operatives, but also other kinds of co-operatives, like consumer co-operatives, for instance credit unions. From a republican perspective, however, co-operatives like consumer co-operatives can be seen as problematic. This is because, in such associations, workers remain disenfranchised and subject to an alien will – to that of, for example in a consumer co-operative, the customers (indeed, from this perspective, there is some coherence in Gierke’s claim that the worker co-operative, of all co-operative types, is the ‘highest form’).[178] This demonstrates that the republican ideal is a demanding one, and that, under this ideal, the worker co-operative has a unique claim amongst business corporation types to be understood as truly free. Having said that, non-worker co-operatives do have a much closer affinity with worker co-operatives than with for-profit corporations. The reason why is that any co-operative, whether a worker co-operative or other co-operative type, cannot be bought and sold on the market (without destroying its status as a co-operative, in any case). Voting power in a co-operative is democratic and, further, voting power cannot be bought. It can only be earned through having an active relationship with the co-operative, such as through being a worker in it or a customer of it.[179] Hence, even if a non-worker co-operative disenfranchises its workers, as a type of business corporation it nevertheless bears a closer relationship with the worker co-operative than it does with the for-profit corporation because it is not a tradeable commodity.

Figure 3: Comparison of worker co-operatives and for-profit corporations.

Before concluding, there are two final issues to consider. The first is whether freeing for-profit corporations from their enslavement to their shareholders would help address their anti-social, pathological pursuit of profit. The second is why enslaved corporations continue today to predominate, and what it would take for free corporations to come to predominate instead. In the following, a section is devoted to each issue, beginning with the first.

Would freeing for-profit corporations from their enslavement help address their anti-social, pathological pursuit of profit? There is evidence that it would. Take what has been argued above to be the paradigmatic example of a free business corporation – the worker co-operative. A worker co-operative, as a business enterprise, must make some profits to remain viable as a going concern. Nevertheless, because it does not, in favour of outside investors,[180] have to maximise them, evidence shows that this allows it to take other things into account in its business decisions. For example, one of the world’s largest worker co-operative entities, the John Lewis Partnership,[181] which has tens of thousands of worker-members and billions of dollars in annual revenue, is able to treat profits as a means to an end, rather than an end in itself.[182] It aims to ‘make sufficient profit to retain ... financial independence’,[183] but, because it does not aim to maximise profits, this allows it to balance the need for profit with other objectives, such as the wages and conditions of its employees. Indeed, its primary purpose, as stated in its constitution, is ‘to find happier, more trusted ways of doing business, for the benefit of us all’, and its first principle, in this regard, is ‘happier’ workers.[184] Studies show that worker co-operatives like John Lewis do in fact put such principles into practice. Worker co-operatives have better employment security, more egalitarian pay scales and higher minimum wages.[185]

There is a huge literature arguing that to address the anti-social behaviour of for-profit corporations it is enough to redefine a for-profit corporation’s purpose or redefine the duties of directors.[186] A problem with this argument, however, is that when shareholders are the board of directors’ constituency, directors are likely to act in the interests of shareholders regardless of their directors’ duties.[187] If they do not, they are likely to be replaced.[188] Hence why scholars like Gerald F Davis and Eva Micheler have argued that, regarding corporate behavioural change, redefining a corporation’s purpose or the duties of directors can only have marginal effects.[189] The ‘corrupting power of stock markets’ is too strong.[190] To achieve meaningful corporate behavioural change, both Davis and Micheler hold, employees must become enfranchised in the corporate decision-making structure.[191] Indeed, there is evidence that even minimal worker enfranchisement can have noticeable implications for corporate behaviour. Take ‘co-determined’ companies, under which workers are provided with representation on a company’s supervisory board of directors,[192] or companies with ‘Employee Stock Ownership Plans’ (‘ESOPs’).[193] Studies show such entities tend to pay higher wages, are less likely to undergo restructuring and layoffs, and have higher survival rates in periods of economic crisis.[194]

It ought to be emphasised that this is not to suggest that free, self-determining business corporations will, necessarily, be models of virtue. Freedom does not cure all vices. A free individual human being, for example, has the capacity to misbehave and do harm, and, to guard against such capacities, social expectations of standards of behaviour need to be articulated and enforced through various mechanisms, including cultural and legal mechanisms. This is no less true of free corporations than it is of free human beings – just like free human beings, free corporations have their own egos and their own interests and cannot always be expected to act virtuously. Nevertheless, the evidence provided above does suggest that worker co-operatives, given they are not enslaved to the will of outside investors, are much less likely to place profits over people than for-profit corporations are. The evidence suggests that the primary beneficiaries of a self-determining business corporation will be its members – its workers. But it is worth highlighting that there is evidence that worker co-operatives are, in relative terms, also superior to for-profit corporations regarding their propensity to consider a wide range of stakeholder interests. For instance, there is a ‘significantly positive’ relationship between ESOP companies and environmentally responsible business practices, a relationship that intensifies with higher levels of employee ownership.[195]

This all supports the idea that, while a business corporation that is owned as a commodity will pathologically maximise profits for its investors, a free business corporation – a worker co-operative – will behave very differently. Hence, at least in relative terms, worker co-operatives – free corporations – are much more likely to display the socially responsible behaviour that the public should reasonably expect of business corporations.

John Stuart Mill famously wrote that, ‘if mankind [is to] continue to improve’, the worker co-operative ‘must be expected in the end to predominate’.[196] Though, today, there are a number of highly successful worker co-operatives, with billions of dollars in annual revenue, that they would come to predominate has, however, clearly not come to pass. In the world of big business, it is the for-profit corporation that continues to dominate the landscape. Why it is that the for-profit corporation continues to triumph over the worker co-operative is an important question. Notably, it does not appear to have to do with their relative productive capacities – evidence shows that worker co-operatives may even have productivity advantages relative to for-profit corporations.[197] Rather, the reason for-profit corporations continue to dominate appears to be because providers of capital have very strong incentives to support for-profit corporations over other kinds of business corporations.[198] A for-profit corporation can be made to make the financial interests of investors its primary operating purpose. For providers of capital, this makes investment in for-profit corporations much more attractive than investment in other kinds of business corporation. In terms of access to capital and the concomitant ability to achieve a position of incumbency in some industry, for-profit corporations are therefore at a distinct advantage compared to worker co-operatives. Further, that the powerful have a very strong interest in the maintenance of for-profit corporations as the dominant business enterprise type, consider the fact that the world’s richest individuals have all amassed their wealth through their ownership or part ownership of what this article has argued are corporate slaves. Elon Musk’s fortune derives from his share in the ownership of Tesla; Jeff Bezos’ from his share in the ownership of Amazon; Bernard Arnault’s from his share in the ownership of LVMH; Bill Gates’ from his share in the ownership of Microsoft; Mark Zuckerberg’s from his share in the ownership of Meta, etc.[199] Indeed, the capacity of an individual to amass the kind of wealth that is today enjoyed by the world’s richest would be almost inconceivable if corporations were not capable of being enslaved.[200] Why, therefore, would the powerful support free corporations over enslaved ones?

This all leads inexorably to the following conclusion: while ownership of business corporations remains legal, enslaved corporations will likely continue to dominate the landscape of big business. Certainly, without being forced to, the rich and powerful are very unlikely to give up ownership of their corporations. The implication is that if corporate enslavement – and, concomitantly, profit-maximisation as an institutional force – is to be addressed, corporate slavery must be made illegal.

Under Australian law, slavery is defined as ‘the condition of a person over whom any or all of the powers attaching to the right of ownership are exercised’.[201] This article has argued that the for-profit corporation meets this definition. Part II presented the realist idea that for-profit corporations are persons, not only legally, but also morally. Part III, using the Roman law of slavery as the main point of comparison, argued that shareholders exercise the powers of ownership over such persons. Shareholders buy, sell and compel for-profit corporations to maximise profits in their interests. Hence, the conclusion that, as persons over whom the powers of ownership are exercised, for-profit corporations qualify as slaves. Part IV, drawing on the republican tradition of thought, proposed that a business corporation is capable of being understood as free when it is able to act according to its own will, in its own interests. This, in turn, requires it to be organised as a democracy of its workers – as a worker co-operative. For a for-profit corporation to be freed from its enslavement, therefore, power over it must be taken away from outside shareholders and reposed, instead, in the workers. Part IV finished with two contentions. First, that freeing for-profit corporations is desirable because worker co-operatives do not have the pathological desire to maximise profits, regardless of the social and environmental costs, that is characteristic of for-profit corporations. Second, that because the rich and powerful benefit from, and so maintain a strong interest in, corporate enslavement, corporate owners are unlikely to release their corporations from servitude voluntarily. The only way to address corporate enslavement, it was therefore concluded, is to make corporate slavery illegal.

The idea that for-profit corporations are slaves and that, to address profit-maximisation as an institutional force, such corporations ought to be freed, is likely to be seen as provocative. Partly why it is likely to be seen as provocative is that the idea that for-profit corporations ought to be freed has not been raised before.[202] That it has not previously been raised is, perhaps, unsurprising. For example, under the Roman Empire slavery was uncontroversial and remained unchallenged by any intellectual movement of which evidence today remains.[203] In that context, the idea that slavery should be made illegal would also have been seen as provocative. Another reason why the idea that for-profit corporations are slaves might be seen as provocative is that many are likely to feel uneasy about the idea that we should ‘free the corporations’. As the literature comparing the corporation to a Frankenstein’s monster demonstrates, corporations have commonly been viewed as monstrous entities – ‘devilish instrument[s]’,[204] that ‘[no one] believes ... are moral agents’.[205] This reaction to the corporation is understandable given the harms caused by for-profit corporations, but the idea behind revisiting Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein in the Introduction to this article was to suggest that we ought to be wary about reacting to corporations in this way. Shelley’s story reminds us that, though entities may appear monstrous to us, that does not make them inherently so. Indeed, it may be that treating them as monstrous is self-fulfilling. Treating the corporation with dignity, rather than with disgust – even as the idea of doing so may seem disquieting – is a course of action that ought not, therefore, to be dismissed cursorily. On the contrary, as this article has sought to show, it is a course of action that is worthy of serious consideration.

* Lecturer, Monash University, Faculty of Law. Email: Duncan.wallace2@monash.edu.

[1] Timothy D Peters, ‘I, Corpenstein: Mythic, Metaphorical and Visual Renderings of the Corporate Form in Comics and Film’ (2017) 30(3) International Journal for the Semiotics of Law 427, 431 <https://doi.org/10.1007/s11196-017-9520-2>.

[2] I Maurice Wormser, Frankenstein, Incorporated (Whittlesey House, 1931) v–vi, 54.

[3] Katie J Thoennes, ‘Frankenstein Incorporated: The Rise of Corporate Power and Personhood in the United States’ (2004) 28(1) Hamline Law Review 203, 235.

[4] Ibid 204.

[5] Joel Bakan, The Corporation: The Pathological Pursuit of Profit and Power (Free Press, 2004) 149.

[6] David Runciman, The Handover: How We Gave Control of Our Lives to Corporations, States and AIs (Profile Books, 2023) 16.

[7] Charlotte Gordon, ‘Introduction’ in Mary Shelley, Frankenstein: The 1818 Text (Penguin Books, 2018) xiv.

[8] Ibid xiv–xv.

[9] Mary Shelley, Frankenstein: The 1818 Text (Penguin Books, 2018) 42 <https://doi.org/10.1093/owc/9780198840824.001.0001>.

[10] Ibid 136.

[11] Ibid 90.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Wormser (n 2) vi.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Thoennes (n 3) 235.

[17] Bakan (n 5) 149.

[18] Wormser (n 2) 54.

[19] As some have argued: Steve Tombs and David Whyte, The Corporate Criminal: Why Corporations Must Be Abolished (Routledge, 2015) 158 <https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203869406>.

[20] Bakan (n 5) 153.

[21] See, eg, Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry (Final Report, February 2019) 401.

[22] See below n 33.

[23] Jason Harris and Timothy D Peters, Company Law: Theories, Principles and Applications (LexisNexis, 3rd ed, 2023) [1.2].

[24] Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) s 57A (‘Corporations Act’).

[25] Co-operatives National Law Application Act 2013 (Vic) s 28 (‘CNL’).

[26] Associations Incorporation Reform Act 2012 (Vic) s 29.

[27] Local Government Act 2020 (Vic) s 14.

[28] Fair Work (Registered Organisations) Act 2009 (Cth) s 27.

[29] For example, Monash University: Monash University Act 2009 (Vic) s 6.

[30] Australian Broadcasting Corporation Act 1983 (Cth) s 5.

[31] Sue v Hill [1999] HCA 30; (1999) 199 CLR 462, 498 [84] (Gleeson CJ, Gummow and Hayne JJ). See also Sebastian HH Davis, ‘The Legal Personality of the Commonwealth of Australia’ (2019) 47(1) Federal Law Review 3; Ernst H Kantorowicz, The King’s Two Bodies: A Study in Mediaeval Political Theology (Princeton University Press, 1997) 15 n 20.

[32] Corporations Act (n 24) s 9 (definition of ‘company’). See also at s 124.

[33] Indeed, listed for-profit companies are only a numerically small subset of the total population of corporations. For example, while there are around 2,000 listed companies in Australia, there are over 250,000 incorporated non-profit organisations: Australian Transaction Reports and Analysis Centre and Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission, Australia’s Non-profit Organisation Sector Risk Assessment (Report, August 2017) 19.

[34] Antony Black, Guild and State: European Political Thought from the Twelfth Century to the Present (Routledge, 2003) 149. See also Ignatius T Eschmann, ‘Studies on the Notion of Society in St Thomas Aquinas: I. St Thomas and the Decretal of Innocent IV Romana Ecclesia: Ceterum’ (1946) 8 Mediaeval Studies 1, 8 <https://doi.org/10.1484/J.MS.2.305877>; Frederick Pollock and FW Maitland, The History of English Law: Before the Time of Edward I (Cambridge University Press, 2nd ed, 1899) vol 1, 495 (‘The History of English Law’).

[35] Black (n 34) 149.

[36] Ibid. See also Hastings Rashdall, The Universities of Europe in the Middle Ages (Clarendon Press, 1895) vol 1, 6–8.

[37] Susan Reynolds, Kingdoms and Communities in Western Europe, 900–1300 (Oxford Universiry Press, 2nd ed, 1997) 63 <https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198731481.001.0001>.

[38] Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth) s 2C(1).

[39] For example, in China: «中华人民共和国民法典» [Civil Code of the People’s Republic of China] (People’s Republic of China) National People’s Congress, Order No 45, 28 May 2020, art 2, and in the United States of America (‘US’): 18 § 2510(6) (2002).

[40] For the argument that the corporation is ‘uniquely’ Western, see Reuven S Avi-Yonah and Dganit Sivan, ‘A Historical Perspective on Corporate Form and Real Entity: Implications for Corporate Social Responsibility’ in Yuri Biondi, Arnaldo Canziani and Thierry Kirat (eds), The Firm as an Entity: Implications for Economics, Accounting and the Law (Routledge, 2007) 153, 155 <https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203931110.ch10>; Ron Harris, ‘Trading with Strangers: The Corporate Form in the Move from Municipal Governance to Overseas Trade’ in Harwell Wells (ed), Research Handbook on the History of Corporate and Company Law (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2018) 88, 91 <https://doi.org/10.4337/9781784717667.00011>.

[41] Teemu Ruskola, ‘Legal Orientalism’ (2002) 101(1) Michigan Law Review 179 <https://doi.org/10.2307/1290419>.

[42] Vikramaditya Khanna, ‘Business Organizations in India Prior to the British East India Company’ in Harwell Wells (ed), Research Handbook on the History of Corporate and Company Law (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2018) 33; Ramesh Chandra Majumdar, Corporate Life in Ancient India (Oriental Book Agency, 2nd ed, 1922) 57.

[43] Chukwuemeka George Nnona, ‘Customary Corporate Law in Common Law Africa’ (2018) 66(3) American Journal of Comparative Law 639 <https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcl/avy032>.

[44] Teemu Ruskola, ‘Corporation Law in Late Imperial China’ in Harwell Wells (ed), Research Handbook on the History of Corporate and Company Law (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2018) 355 <https://doi.org/10.4337/9781784717667.00022>.

[45] See Elman R Service, Primitive Social Organization: An Evolutionary Perspective (Random House, 2nd ed, 1971) 116, stating that all clans have ‘some legal-like corporateness’. See also Ward H Goodenough, ‘Corporations: Reply to Cochrane’ (1971) 73(5) American Anthropologist 1150 <https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1971.73.5.02a00140>.

[46] See Peter Sutton, Native Title in Australia: An Ethnographic Perspective (Cambridge University Press, 2004) 153–8 <https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511481635>; Ian Keen, Aboriginal Economy and Society: Australia at the Threshold of Colonisation (Oxford University Press, 2004) 133–41, 296–303, 368–77; Nancy M Williams, The Yolngu and Their Land: A System of Land Tenure and the Fight for its Recognition (Stanford University Press, 1986) 96.

[47] Henry Sumner Maine, Ancient Law: Its Connection with the Early History of Society and its Relation to Modern Ideas (John Murray, 1920) 134, 141, 197–9. See also Frederick Pollock’s notes on this at 225.

[48] Evidence of the origins of this theory suggests its roots are in rulings by Pope Innocent IV in the 1240s: Eschmann (n 34) 35. See also Joseph Canning, The Political Thought of Baldus de Ubaldis (Cambridge University Press, 1987) 192 <https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511523113>. The concession theory spread, says FW Maitland, because it proved attractive to absolutist rulers: FW Maitland, ‘Introduction’ in Otto von Gierke, Political Theories of the Middle Age, tr Frederic William Maitland (Cambridge University Press, 1900) vii (‘Introduction’).

[49] It was FW Maitland who first introduced this terminology into English-language scholarship: Maitland, ‘Introduction’ (n 48) xix–xxx.

[50] Edward Coke, Institutes of the Lawes of England: Or, A Commentary upon Littleton (J & WT Clarke, 1823) vol 1, 2a.

[51] PA Keane, ‘“No Body to Be Kicked or Soul to Be Damned”: The Limits of a Legal Fiction’ in Rosemary Teele Langford (ed), Corporate Law and Governance in the 21st Century: Essays in Honour of Professor Ian Ramsay (Federation Press, 2023) 22.

[52] Maitland, ‘Introduction’ (n 48) xxx. This poetic rendering of Maitland’s draws on phrasing from the Bible: ‘[T]hen the Lord God formed man from the dust of the ground and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and the man became a living being’: The Holy Bible, Genesis 2:7 (New Revised Standard Version). Maitland appears, however, also to be quoting from John F Dillon, The Law of Municipal Corporations (James Cockcroft, 2nd ed, 1873) vol 1, 152 § 39 n 1.

[53] Bakan (n 5) 149.

[54] ‘We proceed from the firmly-established historical fact that man everywhere and at all times bears within himself the double character of existing as an individual in himself and as a member of a collective association’: Otto von Gierke, ‘The Basic Concept of State Law and the Most Recent State-Law Theories’, tr John D Lewis in John D Lewis, The Genossenschaft-Theory of Otto von Gierke: A Study in Political Thought (Madison, 1935) 169.

[55] Though Gierke took inspiration from his law lecturer, Georg Beseler: ibid 18. See also Michael Dreyer, ‘German Roots of the Theory of Pluralism’ (1993) 4(1) Constitutional Political Economy 7, 14–18 <https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02393281>.

[56] Writer after writer who engaged with Gierke’s theory expressed their debt to, and admiration for, Maitland’s work: see, eg, WM Geldart, ‘Legal Personality’ (1911) 27 (January) Law Quarterly Review 90, 92.

[57] Otto von Gierke, ‘The Nature of Human Associations’, tr John D Lewis in John D Lewis, The Genossenschaft-Theory of Otto von Gierke: A Study in Political Thought (Madison, 1935) 145.

[58] Maitland, ‘Introduction’ (n 48) xxvi.

[59] Ibid.

[60] For Marx, see especially Karl Marx, Marx and Engels Collected Works: Capital Volume I (Lawrence & Wishart, 1996) vol 35, ch XIII. For Durkheim, see Black (n 34) 220–36; James Kirby, ‘History, Law and Freedom: FW Maitland in Context’ (2019) 16(1) Modern Intellectual History 127, 151–3 <https://doi.org/10.1017/S147924431700035X>.

[61] There developed, as Morton Horwitz has observed, a ‘virtual obsession in the legal literature with the question of corporate “personality”’: Morton J Horwitz, ‘“Santa Clara” Revisited: The Development of Corporate Theory’ (1985) 88(2) West Virginia Law Review 173, 217.

[62] David P Derham, ‘Theories of Legal Personality’ in Leicester C Webb (ed), Legal Personality and Political Pluralism (Melbourne University Press, 1958) 1.

[63] An exception is Peter French: see, eg, Peter A French, ‘The Corporation as a Moral Person’ (1979) 16(3) American Philosophical Quarterly 207, 209.

It was not very long ago that the idea of group agency – the idea that social groups might be agents in their rights, with minds of their own – was utterly repudiated by philosophers in the analytic tradition. Not only was this idea dismissed as manifestly false, it was also, on account of its perceived metaphysical extravagance, seen as intellectually backward or anti-scientific. And not only was it roundly dismissed as false and somewhat backward, it was widely viewed as a politically dangerous doctrine, one that was apt, if allowed to infiltrate the broader culture, to promote anti-democratic or totalitarian ideologies. In recent times, however, the theory of group agency has been resuscitated and repackaged, to the extent that it is now a perfectly respectable view held by several respected analytic philosophers.

Leo Townsend, ‘Groups with Minds of Their Own Making’ (2020) 51(1) Journal of Social Philosophy 129, 129 <https://doi.org/10.1111/josp.12295>.

[65] Christian List and Philip Pettit, Group Agency: The Possibility, Design, and Status of Corporate Agents (Oxford University Press, 2011) 20.

[66] Ibid 78.

[67] ‘The theory of judgment aggregation is a growing interdisciplinary research area in economics, philosophy, political science, law and computer science’: Christian List, ‘The Theory of Judgment Aggregation: An Introductory Review’ (2012) 187(1) Synthese 179, 179 <https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-011-0025-3>.

[68] List discusses the intellectual background: ibid 180. For a short account of the discursive dilemma, see Philip Pettit, ‘Corporate Agency: The Lesson of the Discursive Dilemma’ in Marija Jankovic and Kirk Ludwig (eds), The Routledge Handbook of Collective Intentionality (Routledge, 2018) 249, 254–5 <https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315768571-23>.