University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

DISABILITY DISCRIMINATION IN EDUCATION: INVESTIGATING THE ADR EXPERIENCES OF PARENTS AND PRACTITIONERS

ELPITHA SPYROU[1] AND MARIANNE CLAUSEN[1]

Disability discrimination in schools is prohibited by state and federal anti-discrimination laws. If issues arise, complainants may seek redress through formal or informal complaint pathways. These pathways often utilise confidential alternative dispute resolution (‘ADR’), and as such, little is known about how the conflict inherent in such complaints is resolved, if at all. Despite this gap, the recent Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability made recommendations to amend these laws without inquiring into how these complaints were resolved or whether the advantages of ADR are realised. This article employs thematic analysis to address this gap by exploring the experiences of two participant groups involved in these confidential education complaints about students with disability-related challenging behaviours: parent participants and resolution practitioners.

All Australian jurisdictions recognise that students with disability should have access to primary and secondary education free from unlawful discrimination. This recognition is derived from the concurrent operation of compulsory education schemes[1] and applicable anti-discrimination frameworks.[2] If issues arise when accessing these compulsory settings, including for students with disability-related challenging behaviour, redress may be sought through formal complaint pathways or through other informal mechanisms. Irrespective of which process is used, this article shows that there is an overwhelming reliance on alternative or appropriate dispute resolution (‘ADR’) to resolve the conflict inherent in these education complaints. The popularity of ADR to resolve these matters may be due to the theoretical advantages of resolving conflict outside of court, including by providing parties timely access to justice.[3] Although popular, some scholars have questioned whether the advantages of ADR are being realised,[4] while other scholars suggest that ADR is automatically inappropriate for matters involving competing interests such as these education complaints.[5] This clash of interests may exist because the education of students with disability-related challenging behaviours ‘are examples of students with a high degree of disability and so the issues raised are so complex they are unable to be resolved through informal [ADR] processes’.[6]

The final report of the Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability (‘Disability Royal Commission’) suggested that current anti-discrimination protections in Australia are particularly ineffective for students with disability and who are in compulsory education settings.[7] It also made recommendations to ensure these students are ‘[p]rovide[d] equal access to mainstream education and enrolment’.[8] It also suggested state and territory governments should expand or create complaint management mechanisms within education authorities to respond to these complaints in multiple ways, including through conducting conciliations.[9] These recommendations thereby suggest that current laws are inadequate. Although these conclusions and recommendations exist, the Disability Royal Commission’s terms of reference did not specifically require inquiry into the resolution outcomes of finalised disability discrimination in education complaints. As such, little is known about how the conflict inherent in such complaints is resolved, if at all. This knowledge gap exists because the resolution processes heavily rely on confidential ADR and any resulting settlement agreements are private. This lack of knowledge is compounded by the limited empirical data about this phenomenon in existing literature.

This article addresses this gap by employing thematic analysis to explore the experiences of two participant groups – parents who have made education complaints for these students and conflict resolution practitioners who have been involved in resolving these matters. The primary focus of this article is on addressing what ‘outcomes’ are received in these ADR settings and parents’ reflections on them. We have also added the voices of ADR practitioners as a point of comparison. In doing so, it complements the Disability Royal Commission by investigating the outcomes received and considers whether the advantages of ADR are realised for these education complaints. As such, this article is peering behind confidential walls to understand the process and outcomes of ADR in relation to discrimination in education complaints, and how they are resolved, if at all.

This article commences in Part II with a description about the different complaint pathways that exist to resolve these education complaints. This Part draws a distinction between formal and informal complaint pathways and identifies how the access to Victorian complaint bodies differs from other Australian jurisdictions. Part III unpacks the theoretical advantages and disadvantages of ADR. Part IV explains the method and methodology underpinning the analysis of the interview data, while Part V considers the results of the 16 interviews with the study’s 18 participants. This article is concluded in Part VI with a discussion of the results and explains how expected theoretical advantages of ADR are not realised in these education complaints.

The focus of the present exercise is on the resolution pathways for disability discrimination in education complaints relating to primary and secondary South Australian and Victorian students with challenging behaviour. In the interests of brevity, this article refers to these matters as the ‘education complaints’. The term ‘disability-related challenging behaviour’ is applied broadly and includes students with a disability and who are either threatening during periods of stress, refuse to follow instructions which causes distraction, or who simply require ‘quiet time’ to self-regulate their emotions. The Acts relevant to the complaints examined in the analysis are the Australian Human Rights Commission Act 1986 (Cth) (‘AHRC Act’), the Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth) (‘DDA’), the Equal Opportunity Act 1984 (SA) (‘SA EOA’) and the Equal Opportunity Act 2010 (Vic) (‘Vic EOA’). This inquiry scope is applied because there are, or have been, differences in how these jurisdictions deal with the education complaints. Under these Acts, the student is the person aggrieved; however, given the research relates to minors, the complaints are usually initiated by parents. Therefore, and unless otherwise specified, ‘a complainant’ is a reference to a parent or other family-member advocate. Moreover, this article uses ADR to refer to any process which attempts to resolve the conflict inherent in these matters outside of courts or tribunal hearings.[10] In doing so, it considers the National Alternative Dispute Resolution Advisory Council’s[11] four categories of ADR, that being facilitative, advisory, determinative and hybrid processes, occupying different points along an ADR continuum from the perspective of the role of the ADR practitioner.[12]

II COMPLAINT PATHWAYS: THE FORMAL AND INFORMAL REDRESS MODELS

Australian parents and guardians have a legal duty to ensure their child is enrolled in and attends an approved learning program regularly.[13] Furthermore, every Australian anti-discrimination law protects both enrolled and prospective students who have a disability from unlawful discrimination when accessing education. Although a comprehensive discussion about the operation of these protections is outside the scope of this article, it should be noted that there are four elements to a complaint alleging unlawful disability discrimination in education: (1) the student needs to have a disability as defined by the Acts; (2) the complaint must be against an applicable duty-bearer; (3) there needs to be alleged discrimination, meaning the treatment or conduct is prohibited and no exemption applies; and (4) the alleged discrimination is either ‘direct’ or ‘indirect’ in nature. While these four elements are common features across the nine Australian anti-discrimination Acts, their scope and operation differ. For example, the Anti-Discrimination Act 1977 (NSW) is the only Act which allows private schools to refuse the enrolment of a student simply because they have a disability.[14] This article now turns to consider the formal and informal ways of resolving the education complaints.

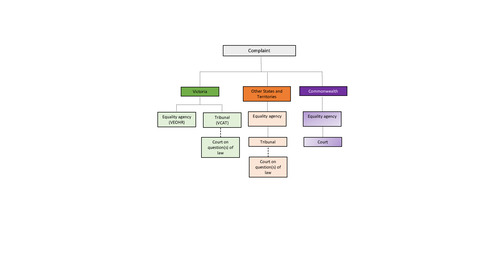

Figure 1: Formal complaint process.

Formal complaint pathways are education matters lodged in accordance with the redress model expressed in the relevant anti-discrimination Act. As illustrated above in Figure 1, there are three common agencies or bodies responsible for resolving these complaints: (1) equality agencies, (2) tribunals or (3) courts. In most other jurisdictions, complaint lodgement with the equality agency is a precondition to tribunal or court access.[15] However, tribunal access is different in Victoria compared to other Australian States and Territories. This difference is because Victoria provides parties a choice: students or their supporters may choose to initiate the education complaint directly with the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (‘VCAT’) or they may first bring the issue to the Victorian Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commission (‘VEOHRC’). What follows is an explanation about the three bodies that comprise the formal complaint pathway for these education complaints.

The equality agencies within the scope of this article are the Office of the Commission for Equal Opportunity (‘OCEO’), the VEOHRC, and the Australian Human Rights Commission (‘AHRC’). Regardless of the level of compulsion to use these equality agencies to seek legal redress, a doctrinal interpretation[16] of the Acts suggests each body responds to complaints similarly.

People wanting to make a complaint to an equality agency must do so in writing.[17] Written complaints are generally achieved through completing an online complaint form,[18] but the OCEO and the AHRC also accept hard copy and emailed complaints.[19] Importantly, the equality agency will only respond to complaints if the matter is within its jurisdiction. Therefore, the alleged breach needs to fall within the scope of the Act and be initiated within the applicable timeframe. For complaints brought to the OCEO and VEOHRC, matters should be lodged within 12 months of the alleged discrimination,[20] whereas complaints under the DDA should be made within 24 months.[21]

Once a complaint has been received, the equality agency either investigates or inquires into the complaint.[22] This is a procedural step to determine whether the body may receive and respond to the complaint. In the South Australian context, however, the Commissioner, or their delegate, needs to determine whether the matter can be resolved through conciliation or whether the Commissioner should refer the matter to the tribunal.[23] A unique feature of the South Australian framework is the requirement that the Commissioner for Equal Opportunity ‘must make all reasonable endeavours to resolve the matter by conciliation’ if the Commissioner forms the view that the complaint may be resolved in this way.[24] This position suggests an emphasis on the value of statutory conciliation offered by the equality agency or a strong desire for discrimination matters to avoid progressing to litigation and tribunal hearings. As Hilary Astor and Christine Chinkin note, in this context, ‘[t]he practices of the organisations that operate these statutory schemes go further than’ the use of conciliation in other contexts.[25] This is because they can compel one or multiple parties to attend and they are ‘structured processes in which the parties meet with the conciliator and attempt to resolve the dispute within the terms of the legislation’.[26]

A doctrinal interpretation of the Acts suggests that complaints are resolved through different ADR processes at the three equality agencies considered in this research. This suggestion of ADR is due to the SA EOA and AHRC Act both prescribing ‘conciliation’ as the resolution method. In contrast, rather than prescribing a specific process, the Vic EOA lists five principles of dispute resolution, including the focus on early, fair and voluntary resolution methods, which complement the nature of the dispute and promote the objectives of the Act. While there appears to be a difference in the resolution methods used by these three equality agencies, the interviews with practitioners revealed a different situation – all bodies resolve disability discrimination in education matters through conciliation, but they do not define this process, ensuring a flexible application to individual matters.[27]

The tribunals currently tasked with jurisdiction over the relevant Acts are the South Australian Civil and Administrative Tribunal[28] and VCAT. While VCAT has been hearing discrimination complaints for more than two decades,[29] the responsible South Australian tribunal has changed three times over the SA EOA’s 40-year history.[30] These tribunals have similar functions, powers, and duties under the Acts, save for how complainants and their supports may access them. Irrespective of how an education complaint is received, it is possible that tribunal staff will engage in some form of ADR before the matter progresses to a hearing. On this point, VCAT may escalate the matter to a hearing, or another form of ADR through either the parties’ suggestion or at the request of a VCAT member.[31] This situation might exist because the Tribunal recognises the benefits of ADR and may require the parties to attend a ‘compulsory conference’ in preparation for a hearing or attempt mediation to resolve the complaint. The functions of the compulsory conference resemble a mixture of facilitative and some advisory ADR principles because the practitioner communicates with the parties to assist in ascertaining the issues, promotes the resolution of the matter, and may identify questions of law and fact that the Tribunal might need to determine in the event a settlement agreement is not reached. Furthermore, the Act prohibits the person conducting the compulsory conference from making any directions.

Although no equivalent tribunal exists federally, and tribunals differ from courts,[32] matters alleging a breach of the DDA may progress from the AHRC to the Federal Court.[33] The ability to do so is by leave and requires the President of the AHRC to terminate the matter,[34] after satisfying themselves that it ‘involves an issue of public importance’,[35] or ‘there is no reasonable prospect of the matter being settled by conciliation’.[36] Additionally, with the court’s leave, special-purpose commissioners, including the Disability Discrimination Commissioner, can appear in the case, although this is rare.[37] If a matter progresses to court, it is also likely that parties would be required to engage in ADR, such as court-connected mediation.[38] There is no direct access to a court for discrimination matters in either South Australia or Victoria. This is the case unless a question of law arises in a matter that is before a tribunal, or the matter is appealed.

If issues between a student, their parent, and school staff exist, but the aggrieved party does not want to make a formal[39] disability discrimination complaint, other resolution avenues exist. Informal complaint mechanisms are matters brought to individuals, bodies, and agencies that are not prescribed within the Acts. This framework of mechanisms includes trying to resolve the conflict at the local school level, or through the body responsible for overseeing the school (ie, government departments, school boards or Catholic education), and education ministers. Victoria has another distinguishing feature given it has the Independent Office for School Dispute Resolution (‘the Dispute Office’).[40] This body was established to assist in resolving ‘complex [educational] issues’ involving Victorian government schools,[41] through using ADR.[42]

Complaints against government schools may also be brought to the South Australian and Victorian ombudsman bodies.[43] These bodies are at no cost but are limited in their investigation and complaint-handling powers. They may make recommendations to the state department to remedy any uncovered errors[44] or may attempt to help the parties resolve the dispute by conciliation.[45]

While ombudsman bodies, overarching school governing bodies and the Dispute Office may receive complaints, these bodies are in addition to the complaint-handling processes prescribed under the three anti-discrimination statutes. Lodging a complaint with these informal bodies or processes does not prevent a discrimination claim under one of the prescribed processes. However, only one formal complaint can be initiated so complainants or their supporters must choose their jurisdiction carefully.

This Part of the article has now explained that there are both formal and informal bodies or mechanisms available to resolve the education complaints. It explained that although this complex matrix exists, staff at the various bodies may use different processes along the ADR continuum to seek to resolve the complaint. This spectrum ranges from statutory conciliation at the equality agency to compulsory conferences or pre-litigation ADR. Having now identified the popularity of ADR in resolving education complaints, this article now considers the theoretical advantages and disadvantages of resolving matters outside of court.

III ADR THEORY

There are academic and practical benefits associated with resolving conflict outside of courts. These advantages have given rise to the reliance on compulsory ADR.[46] Despite these benefits, some argue that ADR is not a ‘panacea’ to the shortcomings of litigation.[47] This Part canvases aspects of this debate with reference to possible realities that may impact parties involved in these education complaints, and which have been identified as theory relevant to our analysis of the interviews.

A Advantages

The issues associated with litigation are multifaceted, given it is perceived as a costly,[48] complex and rigid process from the ‘perspective of personal time costs (that is, stress, loss of profit, loss of opportunity costs), as well as in a direct monetary sense (incorporating legal, expert and other fees)’.[49] Furthermore, certain ADR processes may result in faster resolutions.[50] Measuring these apparent advantages is difficult to do[51] and has been subject to contrary views.[52] That said, a 2017 study about members of the judiciary and their perceptions of court-referred ADR, concluded that judges responded positively to the use of court-referred ADR, even if their workloads increased, which ‘confirms the potential for [court-referred ADR] to improve the efficiency, accessibility and outcomes for the courts’.[53] As illustrated above in Figure 1, no Australian anti-discrimination Act provides direct access to a court, meaning researchers are unable to examine the extent to which this financial benefit exists in the context of education complaints. However, it should be noted that lodging complaints to equality agencies is free and as such minimal monetary costs are incurred, unless the complainant seeks the services of a private lawyer or advocate.

While the financial costs across the complaint matrix are difficult to quantify, there are expected to be non-financial efficiencies associated with ADR. These non-financial benefits are largely individualised in nature, providing an ‘empowering’ process which allows aggrieved parties to tell their side of the story.[54] In theory, this ‘interests-based approach’ enables both legal and non-legal issues to be discussed, providing an opportunity to receive flexible outcomes that may not be available through litigation. ADR has also been linked with restoring party relationships. The majority of literature expounding these benefits is affiliated with facilitative and transformative processes. On this point, and in discussing mediation specifically, Albie Davis and Richard Salem highlight nine ‘innate qualities’ that make ADR an empowering way to settle conflict.[55] While these qualities are dependent on the actual ADR process and model employed, resolving conflict in an interest-based way might result in parties who are more satisfied because they ‘understand their legal rights and options, decide what they want to achieve and move towards mutual agreement early on’.[56] Furthermore, greater levels of satisfaction may result from processes that allow parties control over, and decision-making regarding, how to resolve the complaint.[57] Although such benefits may exist, the rise of compulsory ADR, such as statutory conciliation at an equality agency may be due to the otherwise poor uptake of resolving conflict outside of courts.

Irrespective of the empowering features connected with an interests-based approach, education complaints may not reap these advantages. There is legal ambiguity about the appropriate balance between the right to access education free from unlawful discrimination and the right to safety in the school environment. In discussing the competing obligations that exist under the DDA, and an employer’s industrial relations obligations, Conti J said, ‘finding the correct balance between potentially competing interests would not have been an easy or uncontroversial legislative and regulatory task’.[58] Others suggest that ADR is automatically inappropriate for cases that involve students with a high standard of care: ‘It may be that cases such as Purvis v State of NSW and Minns [v State of NSW] are examples of students with a high degree of disability and so the issues raised are so complex they are unable to be resolved through informal [ADR] processes.’[59] After conducting the analysis that follows, we suggest that an interest-based resolution process is difficult to achieve given these matters involve a clash of interests between the right of the student with disability and the rights of everyone else in the school context. Therefore, we argue that there are irreconcilable interests between parties to these education matters which makes conciliation in its current form an inappropriate dispute resolution method.

B Disadvantages

The criticisms of ADR, particularly in the anti-discrimination context, fall within two categories. First, ADR is seen to create or exacerbate power imbalances. Secondly, its confidential nature, while seen as an advantage to some, is argued by others as stifling the law’s social development.

1 Power Imbalance

The potential exacerbation or creation of power imbalances is a particular concern in these education complaints. This is because parents, who are representing the interests of an individual student, may be pitted against well-resourced and informed educational authorities and bureaucrats who are representing interests of multiple stakeholders.

Power is a complex phenomenon given the various types of control differentials and their potential covert natures.[60] For example, Claire Baylis and Robyn Carroll identify six different categories of power including resources power, strategic power, emotional or psychological power, cultural power, physical power and gender power.[61]

In education complaints, there may be multiple types of power impacting on a parent’s ability to advocate for their child, which may affect negotiation of suitable outcomes. Parents of a disabled child may be negotiating against well-resourced, experienced and informed educational authorities and bureaucrats. In applying Baylis and Carroll’s conceptualisation of power, this could encompass the existence of both resources and strategic power dynamics. For example, a clear power differential would likely exist in conciliations where the parent of the student (who may be unfamiliar with the law and ADR process) is negotiating with representatives from a government department (who may be acting on the Crown’s legal advice). Furthermore, while there may be no financial costs associated with going to an equality agency, parents may need to take time off from paid employment to attend the conciliation. It may be possible that these parents have little or no leave if they have already used their allowances to supervise their child at home while suspended from school. This assumption is supported by research showing that students with disability are being suspended from schools at higher rates than non-disabled peers.[62] This situation may contribute to a deficit in resources power because parents are not being paid to participate in ADR, whereas government bureaucrats representing the Department for Education, or other respondents, continue to be paid. Further, the parents’ personal circumstances and connection with the student means that emotional or psychological power differentials may also be at play. Parents could be experiencing exhaustion and frustration of their advocacy attempts to date. They may also have an emotional perspective regarding what is in their child’s best interests and be experiencing exhaustion because of the various life pressures that may eventuate as a result of supporting a child with disability.[63] These power imbalances and characteristics may mean parents of children with disability are ‘vulnerable’ dispute resolution parties.

Since this original debate materialised, the understanding of vulnerability has developed in academic literature. The modern understanding no longer considers vulnerability automatically applying because of the existence of individual traits.[64] Rather, it is now seen as having a multidimensional nature;[65] anyone can be vulnerable when placed in situations of little control. That said, Teresa Pavia and Marlys Mason suggest that connection with

long lasting, complicated, dynamic vulnerabilities, like those associated with severe disability and impairment, often lead[s] to secondary vulnerabilities in the support group of the vulnerable person. The second vulnerability is not the same as the initial vulnerability, but it is directly related to it.[66]

Given this research mainly involves parents who are representing the interests of their children with disabilities, they may be vulnerable if they have little control over or feel pressure while participating in ADR settings. However, until this study, the extent of this phenomenon has been unknown. In any event, the advisory function of conciliation may counteract the negative effects associated with vulnerability and power imbalances. There is great scope for conciliators to advise parties about their legal rights. This situation raises interesting questions about how parties might be affected by the various legal sources or legal advice. The extent to which disputants are influenced by their legal position, or the degree to which they bargain in the ‘shadow of the law’,[67] is also unknown.

Power differentials and vulnerability can be addressed through legal representation. However, the involvement of legal practitioners in ADR is subject to divergent views. Baylis and Carroll summarise this debate in the following terms:

On the one hand, it is not uncommon to hear mediators complain that some lawyers are unwilling to or incapable of acting in a way that is conducive to the mediation process. On the other hand, in areas where there are serious differences in the parties’ power, the argument is made for legal representation to ensure real and effective participation from both parties and a genuinely consensual agreement.[68]

Therefore, the existence of an ADR practitioner and their ability to provide advice and manage party behaviours might address the existence of these disadvantages of ADR.

2 Public Interest and Social Development Implications

Despite the confidential nature of ADR being viewed as an advantage, it may also be a weakness. ADR fails to establish general norms,[69] and neglects to replicate the broader public policy benefits associated with litigation. This argument is founded on the view that ADR ‘stifles public interest issues and prevents social change through legal precedent’.[70] This reality may have particular implications for disability rights advocates and campaigners,[71] given some believe that ADR does not meet the overall objects of anti-discrimination Acts. This view is held by scholar Anna Chapman who suggests that anti-discrimination bodies are focused on reaching settlement agreements, rather than making determinations about fact and the veracity of the claims.[72] On a related point, these commentators argue that if the intentions of the relevant legislatures were construed broadly as having a ‘remedial effect, then the fact that there are few publicly decided cases each year is detrimental to that objective. This [issue] is exacerbated by the confidentiality of the conciliation process and settlement outcomes.’[73]

Dominique Allen maintains that the ‘limited amount of [discrimination] jurisprudence is a considerable problem for society in general’.[74] In explaining this significance, Allen notes that this has implications for both individual ADR complainants, as well as society at large. This is because there is both a ‘lack of [judicial] guidance about how the court will interpret the law’[75] which affects ‘parties, lawyers and conciliation staff when they are attempting to resolve a complaint and it is an ongoing issue for respondents who do not know what compliance requires’, and fails to offer a deterrent function.[76] This criticism is compounded by theorists who view ADR ‘merely [as] an instrument of social control in liberal legal democracies in that it acts to increase State control in relation to certain types of disputes that raise issues about inequalities fundamental to capitalism’.[77] Additionally, some commentators suggest that ADR focuses on settling disputes rather than enforcing legal rights, which results in ‘second-class justice’.[78] These proponents view settlement agreements as a compromise instead of enforcing rights.[79] For example, Owen Fiss is against settlement because ‘when the parties settle, society gets less than what appears, and for a price it does not know it is paying. Parties might settle while leaving justice undone.’[80] Moreover, Judith Resnik argues that the increased reliance on ADR alters the public’s experiences and logics given ‘[t]he public’s right of access to observe proceedings in courts sustains judicial independence, legitimates public investments in the judiciary, and offers routes to oversight when courts fail to live up to obligations to treat disputants fairly’.[81]

The observation that negotiating parties may receive ‘peace’ rather than ‘justice’ is supported by the above discussion about power imbalances. Parties may settle ‘due to a range of factors, including that they are happy with the offer ... However, their reasons for settling may not be that simple.’[82] For example, and as canvased above, parents may be unaware about what their children are legally entitled to or may be too emotionally drained to continue or pursue the matter.

The focus on ‘peace’ instead of ‘justice’ in dispute resolution has caused some commentators to be sceptical about the potential benefits of non-judicial processes, particularly in the anti-discrimination context.[83] On this point, Beth Gaze and Belinda Smith conclude that ‘it is hard to avoid the conclusion that [the anti-discrimination] system [in most Australian jurisdictions] is not designed to facilitate enforcement of rights, but rather to deter the litigation which is the only means by which rights can be enforced’.[84] Furthermore, depending on the particular type of ADR employed, the applicable process may not require the consideration of legal rights at all.[85] Such processes could include facilitative ADR with minimal involvement from a third-party. This view is grounded on the assumption ‘that ADR processes are settlement-driven and, consequently, that ADR processes necessarily lead to settlements that may result in poor socio-legal outcomes’.[86] In any event, given the interests-based discussion above, these education complaints may be examples where an appropriate balance between the competing interests may not be achieved. Therefore, ‘peaceful’ outcomes may not be possible in these disputes given the law’s multiple shadows, both formal and ‘folk’ law, favour the school respondent over the student and their family-member advocate. For example, Jonathan Crowe et al argue that disputing parties are not only influenced by substantive law while in ADR settings but may also be impacted by ‘folk law’ which they define as ‘the law as depicted in informal sources such as online materials and popular media’.[87]

The confidential nature of the process and outcomes, together with low litigation numbers, potentially fails to promote the broad object of the anti-discrimination Acts. This individualised and private nature may have implications for public interest matters because it could be argued that ADR is attempting to ‘replace the rule of law with nonlegal values’.[88] The confidentiality of the process means that future claimants may be unaware of what a fair and reasonable settlement outcome is. Additionally, ADR’s confidential nature arguably privatises potentially discriminatory conduct because it prevents and restricts public scrutiny.[89] As a result, some argue that the confidential nature limits the law’s ‘ripple’ effect or inhibits judicial development.[90]

The counter arguments to this view are grounded on the basis that it ignores the costs and stresses associated with litigation.[91] Others maintain that these concerns are generic and fail to ‘distinguish between the various processes that comprise the ADR spectrum’,[92] which results in ‘over-simplistic and uninformed conclusions’.[93] For example, Tracey Raymond[94] argues that ADR,[95] specifically the powers and functions of conciliation practitioners, are tools which promote social change.[96] Raymond explains that conciliators can and should recognise and respond to the social context of the dispute and any associated power differentials to ensure that one party is not disadvantaged or privileged over the other.[97] These powers and functions mean that conciliators are not neutral, but are rather independent practitioners who may intervene in negotiations to maximise party control. While this independence differs to the rule of law concept of neutrality, the conciliator’s non-biased involvement may help disputants move beyond self-interests towards a broader social context, thereby promoting social change.[98] Further, in the anti-discrimination law space, conciliators are responsible for upholding the objects of the enacting legislation. This requirement acts as a safeguard which promotes the social context of each dispute. Given the lack of empirical data about education complaints, questions remain about whether the objects of the Acts are being met, whether any outcomes obtained are reinforcing public norms and whether complainants are satisfied.

IV THE STUDY’S DESIGN

A Method and Methodology

The intention of this research project is to understand the experiences of certain participants who have been involved in education complaints across different redress avenues. This empirical work considers the experiences of parents and resolution practitioners. These participants were targeted because the voices of parents are unrepresented in existing data and ADR practitioners offered an interesting point of comparison. Qualitative analysis is appropriate for such exploratory research in a field of enquiry with little existing research. Sixteen semi-structured interviews were conducted by the lead author as part of her doctoral work and they occurred from February 2021 to December 2021. These interviews contain the perspectives of 18 individuals from two distinct stakeholder categories. Participant Group A individuals are parents who made either a formal or informal education complaint on behalf of a student. As foreshadowed in Part II of this article, formal complaints are matters brought to an equality agency under one of the three Acts within the study. Informal complaints are matters which are made to agencies, bodies, education Ministers, or other avenues which are not prescribed within the equality Acts. The second stakeholder group, Participant Group B individuals, are conflict resolution practitioners. In Participant Group A, there were 10 parents or family-member advocates interviewed across eight interviews, equating to 14 hours and 43 minutes of recorded discussion. Participant Group B was comprised of eight dispute resolution practitioners across eight separate interviews, equating to 11 hours and 53 minutes of recorded discussion. The conflict resolution practitioners of Group B were from the OCEO, the VEOHRC, the AHRC and the Dispute Office. The ‘resolution practitioner’ stakeholder group were included in the study as impartial actors in the resolution process. In other words, they do not represent the interest of individual parties.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the associated public health restrictions to travel and social distancing, every discussion occurred and was recorded electronically via the online application Zoom. The Zoom files and raw qualitative data were retrieved and stored in accordance with the University of Adelaide’s storage policy for ‘class 3: confidential or sensitive data’. The University of Adelaide’s Human Research Ethics Committee approved the research in December 2019.[99] All participants provided informed consent to participate in the interviews and had the opportunity to withdraw their involvement in the research within 28 days from the date that they were interviewed by the lead author. No participant withdrew from the research.

Measures were taken to make participants comfortable during the discussions. Such measures included informing participants that they were free to turn off their video camera, may refuse to answer any question and/or could terminate the interview at any point. Two participants noted that they were prohibited from fully explaining the specific settlement outcomes received because they had signed non-disclosure agreements. A third participant noted that they had a non-disclosure agreement in place, but this individual felt comfortable to talk about the outcome in detail given their involvement in the study was on a confidential basis, meaning no personally identifying information would be recorded. Participants were periodically offered breaks during interviews.

Interviews were recorded electronically and the lead author also took contemporaneous notes when conducting the discussions. The lead author transcribed all interviews herself to maintain the confidentiality of discussions. Interviews were transcribed verbatim. This transcription process also allowed the lead author to become more familiar with the interviews, which is an important preliminary step to any qualitative analysis.[100] The following transcription symbols were added to each transcript where relevant.

Table 1: Transcription Symbols

|

Transcription symbols

|

Explanation

|

|

...

|

Untimed pause

|

|

‘quote in italics’ or “quote within

quote”

|

Reported speech or use of air quotes

|

|

–

|

Cut-off speech

|

|

Bold

|

Emphasised speech

|

|

//

|

Beginning and end of overlapping speech or no break between speakers

|

|

:::

|

Preceding sound extended

|

|

[ ]

|

Explanatory notes or indicating changes to the transcribe for

confidentiality reasons

|

These symbols were included to enhance the meaning and value of the transcripts. Identifying material was redacted to maintain participant confidentiality.

The researchers analysed the transcripts using a thematic analysis (‘TA’) approach and according to Virginia Braun and Victoria Clarke’s six-step method.[101] Braun and Clarke have written extensively about TA over the last 15 years and they now refer to their approach as reflexive TA,[102] describing it as ‘a method of qualitative analysis, widely used across the social and health sciences, and beyond, for exploring, interpreting and reporting relevant patterns of meaning across a dataset’.[103] This outcome is achieved by ‘utilis[ing] codes and coding to develop themes’.[104] Braun and Clarke use the adjective reflexive in explaining their approach to TA because they recognise the value of a qualitative researcher who is ‘subjective, situated, aware and questioning’.[105] In doing so, Braun and Clarke see merit in researchers who analyse qualitative data by critically reflecting on their own role, practise and process of the research.[106]

Each member of the research team brought something unique to the study, providing a more comprehensive understanding of the subject matter. This expertise ensured a rigorous thematic analysis could be conducted by combining the knowledge from the fields of law and psychology. The lead author provided a detailed understanding of the legal frameworks and associated research, while the co-author provided insights into human behaviour and thought processes that are relevant for a nuanced understanding regarding participant views about the ADR processes applicable to these education complaints. By combining this multidisciplinary expertise, we offer unique insight into how these otherwise confidential ADR processes are working in practice.

Braun and Clarke suggest a six-part guide to assist researchers to undertake an effective TA. This includes (1) data familiarisation;[107] (2) coding;[108] (3) generating themes;[109] (4) developing and reviewing themes;[110] (5) refining, defining and naming themes;[111] and (6) writing the TA.

Firstly, Braun and Clarke argue that researchers need to familiarise themselves with the data. As discussed above, this process commenced for the lead author by conducting the editing of transcripts herself. However, the co-author and research assistant familiarised themselves with the data by reading and re-reading each de-identified transcript. This step culminated in the edited transcripts being imported into the software program NVivo.

The next step in Braun and Clarke’s guide to TA is the creation of initial codes and coding interesting features across the data set (all interviews). Although this was largely the responsibility of our research assistant, to ensure consistency in coding all researchers individually read the first 20 pages of Participant A1’s transcript. We independently coded interesting points throughout the transcript and later met to share our initial codes. There was broad similarity in the codes used and the research team noted that while the student’s background (behavioural issues and disability) was a dominant code, it was not within the scope of the current study. We decided to focus on the barriers and facilitators for making the education complaint and comments about the process’ advantages or disadvantages. The lead author also methodically reviewed all of the research assistant’s initial codes that addressed this scope.

Following this initial code generation, the co-author completed Braun and Clarke’s third step by searching for themes. Braun and Clarke understand ‘theme development [to be] an active process; themes are constructed by the researcher, based around the data, the research questions, and the researcher’s knowledge and insights’.[112]

The next step in the analysis process was to review these candidate themes. The candidate themes were further developed by the authors and the research question was refined to: how do the expected advantages and disadvantages of ADR compare to the experiences of complainants and conciliators in education complaints? The themes were crosschecked against the individual extracts, as well as across all interviews (the entire data set). This process was concluded by following Braun and Clarke’s suggestion of creating a ‘thematic map’. After this step came the defining and naming of themes, which required the refinement of the patterns based on the overall analysis of the data.

The final step in the analysis process occurred by writing up the findings or ‘producing the report’.[113] This process included the final analysis to the research question and literature and checking all direct quotes against the original audio or video recording.[114]

B Strengths and Limitations

The analysis considers the experiences of 18 participants who have been involved in education complaints about South Australian or Victorian students with disability-related challenging behaviour. We consider disability discrimination complaints about students with challenging behaviours across three jurisdictions and over a five-year period. While this is a limited participant pool, it is informative and suitable for analysis of this type. In accordance with qualitative approaches, the analysis is not representative of all education complaints in Australia. In addition, the small sample prevents the authors from determining the effectiveness of ADR as a method for resolving these complaints. Rather, it provides rich detail of participants who hold relevant insights into the experience of education complaints. It also does not consider the views of school representatives or the voice of the student. That said, the richness of data has allowed us to gain a detailed understanding of participants’ lived experiences through their own words.[115] Participants self-selected to contribute, and this decision may have been prompted by negative experiences. Qualitative analysis is not intended to identify prevalence of issues, so we cannot suggest how common the experiences of participants are. Rather, we have identified patterns in the data that describe how participants have experienced education complaints. A high level of rigour is established by following Braun and Clarke’s method for thematic analysis. The trustworthiness of the analysis is supported by providing quotes from a range of participants and triangulating the accounts of the parent group and the conciliator group. Care was taken to ensure that quotes were used in context and the results were not overstated. Moreover, in a field where little or nothing is known about these complaints, the data value is increased because it addresses a significant knowledge gap in the existing literature to understand the dynamics at play in these ADR settings.

V THE RESULTS

This Part provides thematic analysis about how the law works in practice for education complaints to determine the extent to which the advantages and disadvantages of ADR exist. This Part reports the findings of three main themes that were identified in the analysis and relate to the research question: how do the expected advantages and disadvantages of ADR compare to the experiences of complainants and conciliators in education complaints? The three themes are: (1) outcomes; (2) power imbalance; and (3) emotional toll of process. In comparing the data across the participant pools, there are similarities and divergent views in experiences.

A Outcomes

The participants in the study provided a great deal of information about their experiences and expectations of ADR to resolve these education complaints. These are discussed in the following five sub-themes and are considered with regard to the expected advantages of ADR.

1 Acknowledgement and Apology

The most frequent expectation of parents was their desire for the respondent school to acknowledge that it discriminated against the student with disability. As such, complainants wanted an acknowledgment of their child’s negative experience. The parent participants showed a desire for respondents to reflect and acknowledge their wrongdoing and/or provide an apology. This outcome sought is shown in Participant A1’s account: ‘I just wanted them to acknowledge what happened, I wanted [A1C] to get an apology.’[116]

Participants A9 and A10, who were interviewed together, wanted the school to recognise the humanity of their two children:

[A]ll I wanted was them [the school] to look at – look at these children as – they’re not nuisances ... they’re not um ... You know ... a problem – they’re just human beings, ... and if you just treat them as children and have a little bit of empathy and try to work out how to ... How can we make their day a little bit better.[117]

The practitioner group also stated that acknowledgement of and apology for discrimination can lead to better ADR outcomes in these cases: ‘The most productive ones [conciliation conferences] are where they do kind of start out with ... “this was not our intention, we’re really sorry you’ve had this experience ... we’re sorry that you’ve felt this way”.’[118]

2 Reasonable Outcomes

As discussed above, ADR has the potential to resolve complaints through creative outcomes. Furthermore, ADR theory suggests that if an interest-based approach is used to resolve the complaint, the disputing parties may have greater levels of satisfaction with both the process and any resulting outcome. However, the results varied given parent participants were largely dissatisfied, while practitioners were more positive, and there were conflicting views around what was a reasonable outcome in these matters.

A key concept used in the Acts is ‘reasonable adjustments’, which was often used by participants from both groups. Participants from Group A tended to present themselves and their requests as fundamental and highly reasonable, for example, Participant A6 said: ‘We just thought he had the right to an education and ... the right for him to ... have reasonable adjustments made.’[119]

There seems to be some difference in opinions about whether parties are engaging in the ADR attempt in a reasonable manner. While parents presented their requests as reasonable, practitioners suggested that there may be differing opinions of what is reasonable: ‘I think ... the reasonableness argument is always the most difficult because each party has their own sort of terms on what they think is reasonable or not reasonable.’[120]

Practitioners also suggested that parents’ requests were sometimes unreasonable:

So a parent can sometimes ask for ... things that aren’t practical or reasonable or resource ... they [the school] don’t have the resource for ... often it’s balancing those concepts of what’s unjustified ... hardship on the school as well ... That broader concept of looking at the financial impact, but the impact on other students in the school ... the school as a whole.[121]

These differences in perspectives of the participant groups challenge the possible outcome of a satisfactory agreement between parties. Often, participants reported that these differences of perspectives could be due to or lead to entrenched positions. Participants C1 and B2’s accounts illustrate that pattern: ‘[b]ut I think there are things that are in you know inherent in these situations – which is kind of entrenched perspectives ... kind of ... fundamental breaches of trust ... that can't be resolved’;[122] ‘[y]ou naturally get to a point where it’s clear that the matter’s not resolving; they’re too far apart; ... they’re too ingrained, ... it’s not going to go anywhere from here’.[123]

Managing the parties’ entrenched positions and re-establishing communication between the parties was regularly mentioned as the main challenge for conciliators. Unsuccessful management of these entrenched positions was often suggested to lead to an impasse in terms of reaching an agreed outcome. ADR requires all parties to be able to agree on how to resolve the complaint reasonably and be willing to compromise. The data suggests that there are disparate expectations of ‘reasonable’ and a lack of compromise, which is likely to affect the outcomes of ADR because making concessions is fundamental to successful ADR outcomes.

3 Setting Precedent

While complainants lodged their matters on behalf of their children, or family-member, parents also acknowledged that the motivation for the complaint was broader. The goal in bringing the complaint usually shifted to ‘fighting’ for other children with the same challenges. This pattern is evident in Participant A4’s response, where Participant A4 elaborated on what they refer to as the ‘higher level’ of the reason parents complete a discrimination complaint: ‘Parents end up advocating for all students with disabilities ... they actually see it as ... “I don’t want another child to come into this school ... and to have this experience”.’[124]

The ‘higher level’ purpose or motivation of the parents’ complaint against the respondent often became a key feature of their complaint. They described that a successful outcome of their complaint would prevent future discrimination from occurring in the school. However, this broader expectation may not be in keeping with the individualised and private nature of ADR. The secrecy of the ADR process and outcome does not support an expectation of creating a standard that schools can be held accountable to.

4 The Law and ADR

As explained above, ADR is an alternative to litigation; however, these processes, particularly in the anti-discrimination context, exist within a legal framework. The parent participants suggested improvements to ADR processes applicable to the education complaints that would make it more similar to legal determinations. Participants suggested that their experiences could be improved by independent oversight and keeping the school accountable: ‘They should have ... an external person coming in documenting exactly what was said during those [Student Support Group] meetings with the school ... an external body as part of this whole process ... rather than just allowing it to be under the respondent.’[125]

Participant A7, when referring to her experience in South Australia, recommended a similar improvement to the process:

If you have an independent third body ... that ... utilises legislation ... to overrule and to guide the SA [South Australian] respondent ... when it comes to ... sort of vulnerable age group ... then I think that kind of keeps ... the principal and the SA [South Australian] respondent more honest.[126]

These suggestions are mainly intended to exert control over the respondent ensure they behave appropriately. The parent participants believed that the ADR process left them vulnerable and independent oversight could protect against this vulnerability. Most parent participants conceptualised ADR as being akin to a court case and expected that they would benefit from legal determination, more so than from the ADR process they engaged in to resolve the education complaint.

The practitioners also presented the ADR process as occurring within a legal context and that the legislative framework was helpful. Participant B3 described how the education standards under the DDA were beneficial for students, families, and schools:

So I think that there is a really good framework, um um, for not er only lodging a complaint, but even before lodging a complaint for students to be able to understand you know what rights they have; and their families, as well, but also education providers what responsibilities they have um to students with disabilities.[127]

Participant B4 described how the education standards helped to clarify the legal concept of reasonable adjustments: ‘The standards are often the thing that can really bring parties together ... over ... what does a reasonable adjustment look like.’ [128]

While the practitioner participants had generally positive associations between legislation and ADR, Participant B5 felt the framework was ambiguous: ‘I mean the Act is there and it sets out, you know the obligations ... for organisations ... education providers, in this instance. It’s not specific though – you know it doesn’t tell them exactly what they have to do. So, it’s open to interpretation.’[129]

ADR exists within a broader legal context, which was acknowledged by all participants. Parent participants expected that obtaining a legal determination would improve the ADR process and the outcomes that they would receive. Practitioner participants typically found the legislation helpful to the ADR process in terms of setting expectations.

5 After ADR

Specific ADR processes, such as mediation, are singular events within a broader conflict context. The practitioner participants tended to speak about ADR process, whereas the parent participants commented about the overall conflict. The practitioner participants’ involvement is limited to the ADR process, and they were not involved in ensuring agreements were followed. Conversely, the parent participants’ involvement is ongoing and includes the continuing implications of the ADR.

Practitioner participants often presented the ADR process as being successful when communication improved and plans for the future were made, even in the absence of material improvements:

As I said, they didn’t necessarily get a guarantee of any increased resources, but they had a plan in place for communication going forward between the parents and school ... um for resubmitting plans ... for resources and – ... so they had plans in place of what they were going to do and how they were going to touch base.[130]

Participant B7 acknowledged the difficulty in ensuring that schools delivered improvements as promised:

[S]o although that might be in a written agreement or a ... you know something like that – it’s very hard to actually enforce. Um you might have a school that has the meeting ... uh the school may promise the world in those meetings, but the follow through might not occur.[131]

Parent Participants A9 and A10 highlighted the problem with a lack of authority to implement in settlement agreements:

[B]asically what we wanted to do was – how can we speak to the people who can actually implement change ... you know ... that’s what we wanted, you know, because we’re always speaking to someone who says – ‘oh, I heard what you’re saying ... I agree with everything you’re saying ... but ... I now need to go to someone else’.[132]

Potentially there is a lack of connection between the ADR process and the outcomes of ADR. Moreover, the limited involvement of the practitioner group beyond the ADR process may explain the parents’ differing levels of satisfaction with ADR.

B Power Imbalance

An aspect of participants’ discussions of the ADR process was the presence of power imbalances. These power imbalances related to the discrimination situation as well as the complaint process. Students with disability may require individual accommodations that vary from standard school practices. Practitioners acknowledge the power imbalance inherent in the issue of addressing competing priorities of individual students and the broader school community:

You know it’s it’s [sic] very difficult when it gets to that type of situation where a school feels like they’re putting ... safety procedures in place for the you know, for the benefit of other children um but also it puts the child, with the disability at risk. Um ... You know of the reactions of other children and other families and and you know just how that would make him feel essentially so um ... yeah those competing priorities and um ... needs are one of the hardest things to handle.[133]

Power imbalances were also identified in the complaint process, both by the parent and practitioner groups. From the point of view of parents there was a power imbalance because they were individuals complaining about schools, who were perceived to be more powerful. This is illustrated in A3’s account: ‘I actually think the whole system is not geared to assist a person that has actually been discriminated against ... It’s like ... the big corporations against a little person ... the respondent is always going to win.’[134]

Parent participants also described a power imbalance caused by their level of legal knowledge when working within a process informed by the law. Third-party assistance from a disability advocate or lawyer was described as assisting with the complexity of the processes, alleviating some of the power imbalance caused by a lack of knowledge about discrimination law. Despite being legally trained themselves, A1’s account illustrates this pattern: ‘It was terrific because ... the lawyer could actually identify the advantages of different ... [legal] processes.’[135]

The assistance of lawyers was presented by parent participants as largely beneficial due to their knowledge of the process and legislation. Lawyers were also described as being familiar with participating in ADR processes. The presence of lawyers for the respondent was also interpreted by Participant A4 as an intimidation tactic, intended to dissuade complainants:

[T]he power balance was entirely with the respondent, because there were people that have been in this meeting before. Of course, ... as a parent you come in and you, ... – it’s the first time in this meeting. Um::: and so::: there’s an imbalance that comes with that. The legal representation is there to show::: ... if you::: are – are going to take this down a legal route rout – ‘well look at look all these legal bigwigs that we’ve got – we’re here to play the ... hard game’. It's about ... trying to dissuade you from ...um ah seeking any sort of ... um legal ... ramification, I think.[136]

Parent participants represented themselves as vulnerable in the process of ADR, and the presence of an advocate, regardless of whether they had legal expertise, improved not just their understanding of the process but also strengthened their position. The third-party disability advocate contributed to decreasing the power imbalance, as suggested by A3’s account: ‘Without the advocate they didn’t listen to a word I said.’[137]

Practitioner participants also acknowledged that the presence of lawyers had the potential to create issues of power. They discussed various approaches to ADR where lawyers may or may not be permitted to attend. For example, Participant B1 presented flexible approaches to lawyers being present:

That’s, not to say that they [the respondent] might not have spoken to [lawyers] prior but um – sometimes in tricky circumstances they might ask to bring [lawyers] um and we’ll let that happen, but we won’t let [lawyers] speaking in the joint conference room and let the lawyer speak. – Which is a power we have under the Act and and we do that, where the ... power balance in the conferences is unequal – so that is if the complainant was unrepresented.[138]

Sometimes lawyers were prevented from being involved, due to a perception that complainants would be less likely to have legal representation than the respondent and, therefore, be disadvantaged: ‘Because normally the families are not legally equally represented, so it kind of helps to even out the balance.’[139]

Both participant groups identified aspects of disability discrimination complaints that were vulnerable to the effects of power imbalances. In most cases, the complainants were expected to be the vulnerable party.

C Emotional Toll of Process

A child experiencing discrimination in school is a difficult situation for parents to navigate. There is an emotional toll on the parent, knowing that their child is being treated differently. The parent participants in this study were compelled to take action to advocate for more equitable treatment of their children. In addition to the burden of the situation of the student experiencing discrimination, the process of trying to resolve the dispute through ADR was particularly burdensome to the parent group. ‘So that’s the impact it has on me ... like I’m::: so stressed over it ... but because of what’s at stake I can’t drop it.’[140]

The overwhelming experience of parent participants was negative, however, they felt compelled to continue with the complaint due to the importance of advocating for their child.

Most participants spoke often about the overly complex nature of the process. Participant A8, who left paid employment to home school her two children after failed ADR attempts, explained the nature of the complaint process she went through for her two children: ‘It does feel like the structure of the complaints is ... a labyrinth to ... basically get ...two results – people give up or people leave ... basically.’[141]

Additionally, Participant A10 mentioned that the process could benefit from improved response times: ‘The process is just so slow ... it becomes this back and forth thing with the respondent’s lawyer to our lawyer.’[142]

These examples highlight the difficulty parents experience in navigating the complaint process, even if they have independent legal assistance to aid them.

The complexity and time-consuming nature of engaging with ADR contributes to a situation where complainants are disadvantaged. Pessimism was consistently present in participants’ accounts. Moreover, complainants suggested that their negative experiences translated into physiological and mental health challenges, such as elevated levels of stress and exhaustion. A8’s description of her mental and physical state during the complaint is an example: ‘I just got to the point where I was so ... burnt out ... So you’ve got ... parents who are stressed because their kids are stressed and then you’re dealing with people who aren’t helping and so you just getting more and more stressed.’[143] Participant A3’s description provides another example: ‘I don’t think I could physically::: go through that trauma again – I just can’t do it – um it broke me – um::: and yeah. So the whole – the whole situation was horrible.’[144]

The consistent description of the negative physiological and mental impacts to themselves continue to reinforce complainants’ arguments about the burdensome nature of the process of ADR. This is in contrast to expectations that ADR is a method for resolving conflict in a more efficient and less stressful manner than litigation.

The experience of ADR being burdensome is highly prevalent in the parent participant group, however, it is not present in the practitioner participant group. The parent group were discussing their own personal and emotional experiences, while the practitioner group were discussing professional experiences. The level of emotional investment is different for these two groups. However, there seems to be a general lack of understanding from the practitioners that the process of ADR is particularly burdensome for the parents. While parents described their ADR complaints as stressful, overwhelming, and traumatic, the practitioner group presented generally positive experiences of the ADR process.

Participant B1 described ADR discussions as ‘fair and civil’: ‘Once you set the scene and set the tone and set the expectations, they ... they tend to, ... you know, be quite ... you know, ... be quite um ... fair and civil in discussion, like this, you know.’ This contrasts with Participant A2’s experience: ‘[T]hey were using every opportunity to build a case against my son and me::: ... and it was ... it was horrible and ... um ... I don’t know what to tell you.’[145]

Practitioners’ broad satisfaction with the ADR process seems to differ markedly from the negative experiences of parents within this study. This invites question of the proposed benefits of ADR. The benefits do not seem to manifest for the parent participants in this study, which suggests that ADR may not be appropriate for complaints of this nature.

VI CONCLUDING REMARKS AND RATIONALISATION

To conclude, it is useful to consider what the above analysis suggests about the expected advantages and disadvantages of ADR compared to the experiences of parents and practitioners in education complaints. Before doing so, it should be noted that the current study investigates disability discrimination, which would be complemented by future research investigating harassment and victimisation. This is because it was beyond the research scope to undertake a detailed review of all legislative protections potentially applicable to students with a disability. As such, this article does not consider possible issues of intersectionality. This is because under anti-discrimination law a person may have multiple protected attributes, and not just disability, and the Acts provide legal protections to associates of the person with the protected attribute, including parents of children with disability. Furthermore, future research could usefully explore the views of school representatives. It would also be useful to explore practitioners’ perceptions regarding what they think conciliation encompasses and how they practically work within the confines of their respective legislative frameworks.

Although there is potential for further investigation, the interviews in this study show divergent views between the two participant groups. Further, the interviews contradict multiple assumptions found in ADR theory which thereby suggests the advantages of ADR may not be realised in these education complaints.

First, and as noted above, some researchers suggest that interests-based ADR processes elicit positive levels of satisfaction irrespective of whether a settlement agreement is reached.[146] Moreover, this idea is supported by Robin Wagner-Pacifici and Meredith Hall’s theory of resolving conflict being due to a symbolic event.[147] The process of parties coming together in a formal meeting and creating a common understanding may be such a symbolic event. The conflict may end due to an improvement in the relationship between the complainant and respondent, rather than material changes to the situation. ADR may be a suitable event bringing about an end to a dispute – particularly in cases where complaints are made not to bring about change, but to seek redress for previous experiences. While these assumptions and conceptualisations are focused largely on facilitative processes, the results of this research project show that parents involved in this article are overwhelmingly dissatisfied with both the process and outcomes.

Most parents expressed the view that they initially commenced the ADR process wanting the school to recognise that it discriminated against their child. They also suggested that they were seeking broader change for other students with disability. As such, parent participants seem to be making an education complaint to both acknowledge mistreatment, as well as to bring about change. Practitioners also noted that positive ADR processes and outcomes are linked to schools making this acknowledgment early in the process. However, the ‘reasonable outcomes’ sub-theme suggests a disconnect between the views of these parties, calling into question the willingness of respondents to make this acknowledgment and leave with this shared understanding. This disconnect between the participant groups is further illustrated by practitioners explaining that the most difficult aspect in these ADR events is due to the complainant and respondent having differing and/or entrenched perspectives. This reality thereby queries whether Wagner-Pacifici and Hall’s symbolic event may be achieved in education complaints which could result from the inherent conflict of views between the parties and the persons represented in these matters.

This conflict in interest may be compounded by the self-identification of complainants as being vulnerable in the process, irrespective of the involvement of an ADR practitioner, their own disability advocate, or a lawyer. These findings are evident in the power imbalance theme. On this point, while both participant groups noted that complainants could be affected negatively by power imbalances, the practitioners came to this view on the basis of whether one party was represented by an advocate or a lawyer and the other was unrepresented. This simplistic view does not recognise how Baylis and Carroll’s different categories of power may impact on complainants in education complaints.[148] In other words, practitioners did not elaborate on the dynamic impact of multiple types of power imbalance that may be affecting the parent advocate group.

Further, ADR literature and the National Mediator Accreditation Standards value parties’ right to self-determination above all other principles.[149] The principle of self-determination in this context refers to a party’s ability to agree on how to resolve the dispute and the ability to agree to creative resolution solutions. Despite this emphasis, the results from the study’s parent participants demonstrated that they wanted the school respondent to be held to account through a binding determination and enforceable outcomes, thereby suggesting they were unhappy with the resolution attempt. Therefore, it could be argued that the study’s parent participants do not place the same value on the principle of self-determination. Rather, they are calling for education complaints to be resolved by a legal decision-maker and not through facilitative ADR processes. Contrastingly, practitioners shared a broad positive view that the legal frameworks applicable to these education complaints were appropriate.

While the parents in this study expect that an independent body making a legal determination would assist their case, the law currently limits this potential. This limitation exists because the Acts do not clearly address how competing interests should be resolved, and provide broad exceptions to school respondents. The interpretation of the legislation is also open and the limited anti-discrimination case law that does exist is largely unhelpful for students with disability-related challenging behaviour. In addition, as the ADR practitioner is meant to work within the bounds of the legislative framework and not exercise determinative powers, conciliators are not able to meet the expectations of parents. This is a fundamental conflict between the expectation of parents and the possibilities presented by ADR. Evidence for such conflict questions the suitability of ADR for resolving education discrimination complaints.

Consequently, while there are assumptions grounded in ADR theory that flexible,[150] less legalistic, interest-based outcomes are possible when parties resolve conflict outside of courts, the interview data shows this is not realised for these education complaints. The themes and sub-themes identified in this article therefore call into question the appropriateness of ADR to resolve complaints of this nature, across both formal and informal complaint processes. This is because ADR in its current form, including the impact of the law’s multiple shadows, suggests that parties to these education disputes have irreconcilable interests. As such, these results cast doubt over the suitability of the Disability Royal Commission’s complaint management recommendations, meaning further scholarship is required to consider the appropriate way to meet the conflicting interests and views of these parties.

[1] Adelaide Law School, The University of Adelaide.

[1] School of Public Health, The University of Adelaide. We acknowledge the expertise of PhD candidate, Eric Mercier, who was employed as our research assistant on this article.

[1] See, eg, Education and Children’s Services Act 2019 (SA) ss 3 (definitions of ‘child of compulsory education age’ and ‘child of compulsory school age’), 68–9. See also Education and Training Reform Act 2006 (Vic) s 2.1.1.

[2] See Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth) s 22 (‘DDA’); Discrimination Act 1991 (ACT) s 18; Anti-Discrimination Act 1977 (NSW) s 49L (‘NSW ADA’); Anti-Discrimination Act 1992 (NT) s 29; Anti-Discrimination Act 1991 (Qld) ss 37–9; Equal Opportunity Act 1984 (SA) s 74 (‘SA EOA’); Anti-Discrimination Act 1998 (Tas) ss 16(k), 22(1)(b); Equal Opportunity Act 2010 (Vic) ss 38, 40 (‘Vic EOA’); Equal Opportunity Act 1984 (WA) s 66I.

[3] Anna Chapman, ‘Discrimination Complaint-Handling in NSW: The Paradox of Informal Dispute Resolution’ [2000] SydLawRw 16; (2000) 22(3) Sydney Law Review 321, 322.

[4] See especially Tania Sourdin, ‘Using Alternative Dispute Resolution to Save Time’ (2014) 33(1) Arbitrator and Mediator 61 <https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2721472> (‘Using ADR to Save Time’). See also Carrie Menkel-Meadow, ‘For and Against Settlement: Uses and Abuses of the Mandatory Settlement Conference’ (1985) 33(2) UCLA Law Review 485, 487, citing Thomas Church et al, ‘Justice Delayed: The Pace of Litigation in Urban Trial Courts’ (1978) 2(4) State Court Journal 3; Steven Flanders, Case Management and Court Management in United States District Courts (Federal Judicial Centre, 1977); Maurice Rosenberg, The Pretrial Conference and Effective Justice (Columbia University Press, 1964) <https://doi.org/10.7312/rose94000>. See also Michael Heise, ‘Why ADR Programs Aren’t More Appealing: An Empirical Perspective’ (2010) 7(1) Journal of Empirical Legal Studies 64, 89.

[5] Karen Toohey and Helen Hurwitz, Human Rights & Equal Opportunity Commission, ‘Alternative Dispute Resolution in Education: Case Studies in Resolving Complaints of Disability Discrimination’, Australian Human Rights Commission (Web Page, 2002) <https://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/complaint-information-service/publications/alternative-dispute-resolution-education-case>.

[6] Ibid.

[7] This is evidenced by all Commissioners recommending changes to section 22 of the DDA (n 2) to strengthen the anti-discrimination legislation relating to education. It is further supported by evidence received in public hearings which suggested that students with disability-related challenging behaviour have been excluded from school because of inadequate supports from schools. See especially Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability (Final Report, September 2023) vol 7, 170–3.

[8] Ibid 13 (Recommendation 7.1).

[9] Ibid 21 (Recommendation 7.10).

[10] National Alternative Dispute Resolution Advisory Council, ‘Legislating for Alternative Dispute Resolution: A Guide for Government Policy-Makers and Legal Drafters’ (Guide, November 2006) 100 (definition of ‘ADR’).