|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal Student Series |

GETTING THE RIGHT VOICES HEARD: A PRELIMINARY ANALYSIS OF THE QUALITY AND DIVERSITY OF INFORMATION USED IN PARLIAMENTARY INQUIRIES

JOSIAH FAJARDO

Now is an important time to evaluate the effectiveness of Australian parliamentary inquiries. The workload of committees has grown significantly over the past two decades, raising both the promise of ‘democratic renewal’ through improved public participation and the possibility that an overworked system will produce disillusionment while using up scarce resources.[1] The present study aims to undertake a preliminary exploration of whether the increase in public participation has in fact improved the inquiry process.

By analysing the citations received by entities that submit to parliamentary inquiries, this study provides a sketch of the type of information that committees are considering and how this develops over time. First and foremost, it suggests that while a small number of submitters tend to receive a disproportionate amount of committee attention, it is still relatively easy for new voices to be heard before committees. This finding is consistent with prior studies but is made here with respect to a wider range of inquiries over a much longer time scale. In addition, this study provides evidence that committees do tend to rely upon submissions from the kinds of entities that can provide relevant information on the subject matter of their inquiries, and this trend may be increasing with time.

Ultimately, this thesis demonstrates the justification for and the feasibility and value of semi-automated citation analysis as a tool to gain insight into the quality and diversity of information relied upon by parliamentary committees. Part II explains why quantitative measures of the ‘attention’ committees pay to different submitters can provide an indication of issues with the flow of information to committees. Part III justifies why citation analysis in particular is an appropriate measure of the ‘attention’ received by different submitters and why semi-automated analysis is the best way to implement this metric. Part IV provides a detailed explanation of how the final dataset of inquiry, submission, submitter and citation information was assembled. Part V provides an outline of the key findings of the study and Part VI concludes with avenues for future research.

There is no accepted, objective method to holistically measure the performance of committees due to their multiple objectives and the multiple stakeholders seeking conflicting outcomes from the inquiry process.[2] Instead, past studies of parliamentary committee activity have tended to identify and then measure a subset of desirable features or outcomes of the inquiry process using quantitative and qualitative measures or a mix thereof.[3] Despite their limitations in the context of political institutions,[4] Monk has argued that quantitative methods can provide ‘a new perspective’ and lead to ‘better informed’ debate on ways to improve committee processes.[5]

Therefore, as a preliminary investigation, this study examines quantitative methods of assessing certain features of parliamentary inquiries over time which should, ideally, improve with increased public participation. Specifically, it analyses the frequency with which different individuals and entities who make submissions to inquiries are cited by committees in their final reports as an ‘approximate indicator’[6] of the extent to which committee reports reflect diverse and informed opinions. The committees selected as the subject of this study are the 16 general purpose Senate Standing Committees, as these have existed in a consistent structure since 1994[7] and are the main committees through which the public can provide input on general legislation.[8]

This Part begins by providing background on the challenges presented by increased committee activity and public involvement in inquiries. It then considers the role of parliamentary inquiries in Australia’s democratic system and explains the importance of diverse and informed views reaching lawmakers through the inquiry process. Finally, it provides a preliminary justification for citation analysis as a quantitative method of assessing the ‘market’ for committee attention over time.

Writing in 1999, Dr Gordon Barnhart, as rapporteur for a study group on parliamentary committees organised by the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association, identified the growing challenge faced by Parliament and parliamentarians to fulfil the competing objectives of grappling with large volumes of information in a meaningful way and making the rapid decisions needed to meet the demands of ‘this fast-paced society’.[9] Barnhart and the study group saw parliamentary committees as well-placed to address this challenge.

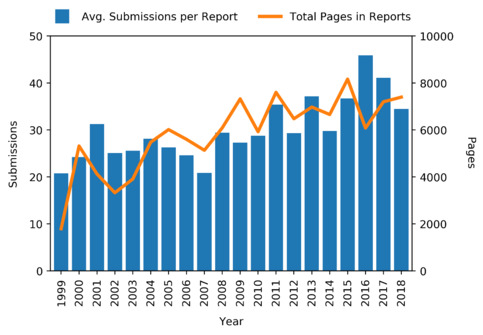

These observations are even more relevant 20 years later. The volume of legislation referred to parliamentary committees has increased: from 55 bills from 1970 to 1989, to 55 in just 2018 alone, with a total of 2327 from 1990 to 2018.[10] This is reflected by a marked increase in the volume of submissions received by committees and the correlated total pages in committee reports since 1999, as shown in Figure 1. The growth in average submissions[11] received by committees per report indicates an increase not only in the overall workload of committees but in public participation in the inquiry process.

Figure 1: Total pages in committee reports and average submissions received per report (other than from ‘individuals’) for inquiries considered in this study.

Incidentally, Figure 1 also provides an initial indication of the utility of the dataset that was assembled for the purposes of this study, as it provides empirical support for the view that public involvement in parliamentary inquiries has, on average,[12] increased over the past two decades – an outcome which until now has been sought after but only observed in anecdotal cases.[13]

Since the process for referring Bills to the Senate committees was standardised with the establishment of the Selection of Bills Committee in 1990,[14] Senate committees have been a conduit for the public to play a more formal role in parliamentary decision-making. Commenting on the growth in public submissions in the 1990s, Halligan, Miller and Power note that these have been ‘a substantial addition to the information and diversity of comment on record for bills, compared to the previous situation’.[15] The authors state that ‘the benefits are clear’, with the caveat: ‘[w]here the quality of evidence is substantial’.[16]

This raises the first key issue accompanying the growth in committee workload and public engagements: receiving more submissions does not necessarily result in receiving better quality information. Morris and Power’s review of submissions to one Senate committee from 2002 to 2007 provides one example of this phenomenon: ‘receiving a large number of submissions from individuals supporting a particular point of view does not always provide committees with proportionate amounts of useful evidence’.[17]

This study will gather evidence as to whether committees are being appropriately discriminatory in the types of submissions being relied upon in final reports. In this study, references to the quality of information in submissions are references to this idea of the amount of useful, accurate information provided that is not otherwise available to the committee.

The second key issue with increased public engagement is that such engagement should reflect the diversity of views within the community, rather than a small subset of organisations that are repeatedly relied upon by committees. There are two reasons why an overreliance on these so called ‘usual suspects’ by committees is problematic.[18] First, it may prevent the committee from adequately accounting for the views of minorities or uncovering new useful information.[19] Second, especially in the context of the Senate committees’ growing workload, it exacerbates ‘witness fatigue’, whereby expert and advocacy organisations that regularly assist inquiries with submissions lack the resources to continue appearing on the same issue.[20]

It is important to investigate whether the quality and diversity of submissions relied upon by committees has improved over time as this is indicative of the extent to which they fulfil their broader role within our democratic system.

This thesis does not aim to provide a comprehensive theoretical framework for understanding the work of parliamentary committees. However, what follows is an argument for why quantitatively measuring the inputs (submissions made) and outputs (citations received) of parliamentary inquiries is at least a logically defensible way of attempting to assess whether the aforementioned growth in public participation has improved committee performance.

The 16 general purpose Senate Standing Committees which are the subject of this study are made up of paired ‘references committees’ and ‘legislation committees’ addressing eight subject areas and their associated departments.[21] For inquiries by both types of committees, submissions are usually invited and oral evidence may be requested from ‘government and non-government agencies known to have an interest in the matter under inquiry’ and ‘[p]ersons or organisations with a specialist knowledge or interest’.[22]

These committees perform a crucial role in Australia’s parliamentary democracy. They provide a forum for Parliament to hold the Executive Government to account.[23] They enable parliamentarians to inform themselves of issues of concern to the public,[24] and to obtain expert advice on the increasingly complex and specialised subject matters about which legislation is required.[25] Furthermore, committees encourage public participation in the democratic process by inviting input from the wider community and by publicising issues that otherwise receive less attention.[26]

In fulfilling these roles, a central tension emerges between the two key issues raised in Part II(A).

It is important that committees receive quality information from experts, well-resourced interest groups and from marginalised individuals and groups whose voices might not otherwise be heard. Each of these sources allows committees to gain new insights into the issue at hand. Regarding experts, Grenfell and Moulds have argued that part of the reason the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security was responsible for ‘a significant number of successful amendments’ to counter-terrorism legislation was because of its ‘strong track record of attracting high quality, detailed public submissions from a range of individuals and organisations with ... legal expertise’.[27]

Similarly, interest groups can be a valuable source of information for committees. Marsh’s 2006 survey of a broad cross-section of interest group submitters to parliamentary inquiries found that 82% gathered new information, either from their members or through general research, in preparing contributions to inquiries.[28]

However, maintaining a diversity of sources from which information is obtained is an important counterweight to prevent an overreliance on particular submitters from undermining the work of committees. Regarding experts, in the context of counter-terrorism legislation similar to that discussed above, Dalla-Pozza notes that for several inquiries conducted from 2002 to 2005 the Senate Committee on Legal and Constitutional Legislation Committee ‘only received the views of ‘professional’ organisations’ and ‘could only present a narrower scope of viewpoints on these legislative proposals’.[29] Dalla-Pozza argued that this ‘paucity of non-government information’ made it more difficult for parliamentarians argue forcefully for changes to the legislation drafted by the Executive.[30]

A more significant risk arises where a ‘vocal minority’ exists whose perspective is given excessive weight by the committee,[31] which can mean that community attitudes towards an issue are not captured and the public loses faith in the inquiry process.[32] An example of this was the strong and public criticism of the report of the Inquiry into Home Ownership in December 2016.[33] The Committee’s majority report made no recommendations despite receiving 86 submissions, and it was labelled by the Labor Opposition as ‘a complete waste of taxpayers’ money’.[34]

In the Greens’ dissenting report, the Committee was specifically criticised for failing to acknowledge the issue of rising house prices ‘despite the evidence from regulators and economists’ and being ‘deaf to [the] concerns’ of economist Saul Eslake who gave evidence regarding the same.[35] The Greens’ dissent also suggested that the Committee had preferred the evidence of ‘those with a vested interest in the property market’ over the consistent evidence of other participants.[36]

Thus, committees must seek to find an appropriate balance of seeking out and relying upon information provided by experts, interest groups and marginalised sectors of the community without allowing a small number of submitters to dominate the discourse.

Resolving the Tension through a Competitive Framework

The relationship between different submitters to a committee inquiry and the ultimate outcomes of the final report can be compared to a market in which various interest groups ‘engage in a competition for attention for public intervention outcomes’.[37]

In his 2006 book Public Policy: The Competitive Framework,[38] Ewen J Michael expands on this analogy and argues government should ‘support the competitive process as a means to pursue the benefits of allocative efficiency for society as a whole’.[39] This goes beyond a ‘pluralist’ theory of democracy in which the competition between different interest groups is a ‘an automatic, self-balancing, social relationship’ that requires no government intervention.[40] Rather, under Michael’s competitive framework, government must prevent certain interest groups from securing a ‘monopoly’ of ‘access to key decision makers’ and misusing their ‘market power’ to distort the flow of information to government.[41] At the same time, the value of the information provided by these groups reaching government is recognised as essential for the market to function efficiently.[42]

This is a useful framework through which to analyse the inputs and outputs of the parliamentary committee system. Extending the market analogy further, this study seeks to explore quantitative measures to monitor for the abuse of market power within the market for the attention of committees. As with the case of actual market regulators, these measures include monitoring the ‘market share’ of entities (that is, the share of citations in final committee reports), and ‘how difficult it is for competitors to enter the market’ (that is, the frequency with which first time submitters are cited).[43]

At this point, there is a prima facie case for conducting citation analysis of Senate Committee reports to provide insight into the extent to which committees are drawing upon the kinds of submitters that can provide useful information and the extent to which the ‘market’ for committee attention remains competitive. What follows in Part III is a justification for this approach in light of previous similar studies.

This study uses citation analysis provide insight into the types of organisations that Senate Committees rely upon and the extent to which new voices are given similar attention to more established submitters. The citation analysis in this study consists of the following core components which were implemented using a semi-automated content analysis program:

1. Classification: Identify the entities making submissions to each inquiry and classify into categories including those identified as likely to provide relevant and quality information, such as expert, interest group, and advocacy organisations.

2. Frequency: Count the frequency with which each submitter is cited in each report as an approximation for the ‘attention’ or ‘access’ achieved by that submitter.

3. Linkage: Link the citation records by entity across the different inquiries over time.

4. Type Categorisation: Analyse citation patterns of the different committees over time to determine which types of entities are most cited, and hence the most ‘heard’.

5. Frequency Categorisation: Analyse the citation patterns over time to determine whether certain entities tend to accumulate more of the citations, and thus receive the most ‘attention’, over time.

6. Pattern Identification: Identify patterns that could be considered consistent with improved quality and diversity of information considered by committees.

This Part begins by explaining how the method outlined above expands upon existing quantitative studies of committee activity to provide further insight about the quality and diversity of information relied upon by committees. It then provides a justification for citations as a metric for the attention received by different submitters over time, first on the basis of general citation analysis approaches to legal and law reform institutions, and then based on the way in which submitters themselves assess their impact. Finally, it justifies the use of automated rather than manual content analysis methods.

In the context of parliamentary committees, past quantitative studies have tended to focus on the types of entities making submissions, and measuring participation (ie, number of submissions) rather than the attention these submissions received (more associated with citations).[44] However, these methods are useful for providing a proxy for the nature or quality of information received by particular inquiries.

An example of using the ‘Classification’ and ‘Type Categorisation’ steps outlined above to draw insights about the quality or usefulness of information available to the committee is Dalla-Pozza’s study of successive inquiries into counter-terrorism legislation. Dalla-Pozza linked the lower proportion of non-government submissions and the reliance on a limited number of ‘professional’ organisations to a resultant ‘paucity of non-government information’ which made it more difficult for parliamentarians argue forcefully for changes to the legislation drafted by the Executive.[45] Dalla-Pozza recognised that such statistical analysis only represented a ‘starting point’ for analysis to be supplemented by qualitative research.[46]

This study provides an example of how classification of submitters into meaningful categories can be used to draw tentative conclusions about the type of information received by the committee, and these can be extended by coupling this classification with the frequency with which said submissions were cited.

In terms of identifying the diversity of input akin to the ‘Frequency’ and ‘Frequency Categorisation’ steps above, the most important study is that of Marinac in 2004. Marinac aimed to test the criticism identified by Paxman in 1999 which encapsulates the antithesis of the diversity of input referred to in Part II:

that bills inquiries regularly attract submissions and witnesses from the same organisations, and ‘witness cliques’ develop around certain issues ... [such that] the same old paths are being trodden as particular issues regularly arise, with predictable outcomes.[47]

Marinac examined the frequency with which witnesses appeared before the Employment, Workplace Relations and Education Committee in the 39th and 40th Parliaments, rather than the submissions the Committee received. The results provided support for the view that there were in fact a handful of ‘usual suspects’ that were far more likely to provide evidence to legislative inquiries.[48] However, they also showed that there were consistently one-off witnesses appearing at inquiries over time.[49] This suggests that, in the context of that committee, while certain submitters had a sizeable share of the market for committee attention, they did not have a ‘monopoly’ as it was still relatively easy for competitors to enter the market.[50]

The use of witnesses as a quantitative measure is closer to citation frequency than simple submission counts, as witnesses provide evidence upon invitation by the committee (often after receiving their written submissions), and this therefore provides an indication that the committee has given consideration to the views of that witness. However, citation frequency can provide even greater insight since it provides a way to rank submitters to the same inquiry based on the attention they received.[51]

Therefore, the methodology proposed is a logical extension of existing quantitative measures of the quality and diversity of input to parliamentary committees.

Citations can be used as a proxy for the attention given to a particular submission by the committee. Citation analysis is based on the reasonable assumption that a citation ‘is a public declaration that the author has read and been influenced by the cited text’.[52] While it does not allow conclusions to be drawn about whether the author agrees with the source cited, it does suggest the information was important or relevant to the subject being considered. Given that this study is primarily concerned with the relevance of and attention paid to the submissions to parliamentary inquiries, citation frequency is an appropriate metric to use.

Determining the quality and diversity of the information provided to and relied upon by bodies undertaking law reform inquiries has been the subject of recent scholarship involving citation analysis. Past studies have examined the type of information relied upon by report authors (eg, quantitative or non-quantitative information),[53] or the character of the individuals and entities making submissions to and being cited by the inquiries.[54] These studies reflect the ‘Classification’ and ‘Type Categorisation’ steps outlined above, since they classify the citations but do not examine the frequency with which particular entities are cited over time.

However, the closest study to the present methodology is Smyth’s analyses of the citation practices of various Australian Courts in a series of articles since 1992.[55] In addition to classifying the types of citations, Smyth also identifies the frequency with which sources are cited over time, allowing him to, for example, rank the secondary sources most cited by the District Court of New South Wales.[56] This analysis involves all the steps in the methodology outline above, except perhaps ‘Linkage’.

With these methods, it will be possible to determine what types of submitters committees tend to cite and hence give attention to, which, as has been demonstrated, can be an indication of the relevance of information received (quality). Further, by analysing entity citations aggregated over time, one can identify whether there are ‘usual suspects’ for each of the 16 committees the subject of this study (diversity).

The final piece of analysis required is an attempt to identify whether past citation frequency influences future citation frequency, which requires the records of entity citations to be ‘Linked’ over time, rather than simply summed or aggregated. This is essentially applying a more ‘bibliometric’ form of citation analysis commonly used in libraries which seeks to create networks of sources within a given corpus of materials.[57] By constructing such a network of submitters within the body of reports, this study will provide a more robust picture of how diverse the viewpoints considered by committees really are.

A key assumption underpinning this study is that citation of a submission by a parliamentary committee reflects the successful communication of information from the submitter to the committee. This assumption is consistent with the way that advocacy organisations which make submissions to inquiries assess their impact in practice.

In Williams’ survey of 11 not-for-profit social justice advocacy organisations who made submissions to parliamentary inquiries, most reported that they determined whether they had made an impact ‘by assessing whether they had been quoted in the report, and whether their recommendations had been taken up by the report’.[58] Queensland Law Society,[59] the Consumers Health Forum (‘CHF’) of Australia,[60] and the Public Interest Advocacy Organisation[61] have all used the citation of their submissions in parliamentary committee reports as evidence of the effectiveness of their advocacy activities. CHF even stated that their ‘submissions and the many subsequent appearances at public hearings and citations in parliamentary reports highlight the value of CHF’s input’.[62]

The justification for using an automated analysis method in the present study is that it allows a far larger dataset to be analysed than would be possible through manual analysis.[63] The ultimate dataset included 1530 reports of parliamentary committees, averaging 72.9 pages in length and 89.6 total citations to various submissions. This totals 111 558 pages and 137 156 citations and was analysed by a single researcher over a period of two months.

By way of comparison, Smyth’s 2018 analysis of District Court citations involved two research assistants reading 3266 cases averaging 50–70 paragraphs in length and averaging about 5–11 citations per case over a period of eight months.[64] This sample size was ‘certainly larger than that used in previous citation studies of Australian courts’.[65] However, Smyth noted that ‘[g]iven the way the data was collected – using research assistants to read each case – the monetary cost of collecting citations on 3266 cases was high’.[66] Thus, the use of automated methods in the present study has enabled a significantly larger dataset to be analysed in a much shorter time frame.

The drawback of automated methods is that the accuracy of Smyth’s analysis is higher than that achieved in the present study: Smyth found a 99% consistency between cases he analysed and those his assistants did, whereas here, the automated classifier had an accuracy of 86.7% compared with manual methods.[67]

Nevertheless, the advantages of automated methods make them preferable so long as ‘measurement error is low enough relative to the systematic variation so that the researcher can make reliable conclusions from the data’.[68] Past automated content analysis studies have used ‘spot checks’ of small but random selections of data,[69] and comparisons to manual analysis of representative samples of the total dataset of a ‘feasible’ size[70] to estimate precision and check whether algorithms operate as expected. These methods were used in the present study.[71]

Having justified the use of citation analysis and a semi-automated implementation of this method, the following Part describes the process used to assemble the dataset of citation counts.

The semi-automated citation analysis in this study follows the structure commonly used in both general data mining and automated text analysis[72] and as well as citation analysis:[73] data collection, data pre-processing, citation classification, and data interpretation and analysis. The method used for the ‘classification’ step involved several standard subprocesses of record linkage,[74] ‘stopword’ identification,[75] and dictionary-based classification.[76] The code used to perform these operations was written in Python.[77]

Consistent with recent recommendations to improve the transparency and replicability of content analysis research,[78] this Part will explicitly document each of the steps involved in the assembly and validation of the final database of report and submission data used for analysis.

The first stage in the citation analysis procedure was to collect the final reports of the inquiries carried out by the 16 general purpose Senate Standing Committees. Each of the eight pairs of committees provides links to the home page of the previous inquiries it has carried out on the Parliament of Australia website.

When the data was collected on 11 March 2019, 1831 past inquiry reports were identified tabled between 15 February 1999 and 8 March 2019, spanning seven Parliaments and just over 20 years. Reports from before the 39th Parliament were excluded due to their inconsistent format. One-page reports, prematurely closed inquiries and reports that made no mention of ‘submissions’ were also excluded, leaving 1748 available completed inquiries. The published links to these inquiries were collected manually from the webpages listed in Table 1. A simple web scraping tool was written to efficiently locate and download as many of the final reports from these inquiries as possible. Ultimately 93.0% (n=1625) of the reports were acquired using this method.

Table 1: Links to completed inquiries and reports by committee

|

Committee

|

Link (www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate)

|

|

Community Affairs

|

/Community_Affairs/Completed_inquiries/2013-16

|

|

Economics

|

/Economics/Completed_inquiries/2013-16

|

|

Education and Employment

|

/Education_and_Employment/Completed_inquiries/2013-16

|

|

Environment and Communications

|

/Environment_and_Communications/Completed_inquiries/2013-16

|

|

Finance and Public Administration

|

/Finance_and_Public_Administration/Completed_inquiries/2013-16

|

|

Foreign Affairs Defence and Trade

|

/Foreign_Affairs_Defence_and_Trade/Completed_inquiries/2013-16

|

|

Legal and Constitutional Affairs

|

/Legal_and_Constitutional_Affairs/Completed_inquiries/2013-16

|

|

Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport

|

/Rural_and_Regional_Affairs_and_Transport/Completed_inquiries/2013-16

|

From each inquiry report, three sets of information needed to be extracted: a numbered list of submissions to the inquiry; the number of times each submission was cited; and the date on which the inquiry was referred to the committee.

Report PDF files were first converted to text using XpdfReader. Then, regular expressions[79] were used to identify the relevant items:

• Submitter names and submission numbers were extracted from an Appendix expected to occur towards the end of the report.

• Footnotes were extracted by searching each page for sequentially increasing numbers, repeatedly reading each page line by line from the bottom of the page.

• Citations of submissions were extracted using a regular expression matched against the entire document and against the footnotes alone.

• The referral date was extracted using regular expressions based on the common terminology used by the committees. Dates could only be parsed in 85.5% of the downloaded reports (n=1389).

This method was based on the fact that most reports included an Appendix at the end of the report with a numbered list of submissions, as in Figure 2. The algorithm would identify and store three numbered submissions from Figure 2. It would then expect the Department of Veterans’ Affairs submission to be referred to throughout as something similar to ‘Submission 2’ or ‘Submission No. 2’.

Figure 2: Standard layout of submission list.[80]

The accuracy of the parsing algorithm was validated by comparing the results to a manually parsed representative sample of one randomly selected inquiry for each of the eight paired committees for each Parliament, a total of 56 inquiries. This indicated that the parsing script had 91.1% accuracy for submission identification, 96.4% accuracy for correct submitter name extraction, 69.6% accuracy for footnote identification and 100% accuracy for referral date extraction, where a referral date extraction had been attempted. Furthermore, the citation counts when comparing entire document search to footnote-only search were identical for 99.99% of submissions. Therefore, given the lower accuracy for footnote identification, the total document search method was used to get citation counts.

Several improvements to the code were made based on errors and irregularities uncovered during the above validation process. For example, in several inquiries the committee skipped or repeated a submission number in the submission list, and the code was modified to account for this possibility. Thus, the accuracy measures above should be seen as an upper bound for the error.

The total number and proportion of reports that were successfully downloaded and submissions extracted, by parliament, are shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Success of report download and submission extraction.

|

Parliament

|

Total

|

Downloaded (#)

|

Downloaded (%)

|

Submissions extracted (#)

|

Submissions extracted (% of downloaded)

|

|

45

|

284

|

281

|

98.94

|

277

|

98.58

|

|

44

|

300

|

286

|

95.33

|

281

|

98.25

|

|

43

|

312

|

300

|

96.15

|

290

|

96.67

|

|

42

|

261

|

252

|

96.55

|

234

|

92.86

|

|

41

|

237

|

229

|

96.62

|

218

|

95.2

|

|

40

|

178

|

158

|

88.76

|

139

|

87.97

|

|

39

|

176

|

119

|

67.61

|

91

|

76.47

|

|

Total

|

1748

|

1625

|

92.96

|

1530

|

87.53

|

This stage required submitters to be classified into categories and to identify when the same submitter had submitted multiple times to different inquiries and link those records. This was accomplished using a combination of rule-based and dictionary-based methods.[81]

Consistent with the discussion on Part II, categories were developed to reflect those that could provide useful information, including ‘experts’, ‘representative’ bodies (interest groups, such as ‘unions’ and ‘associations’) and ‘not-for-profits’ (‘NFPs’), which were intended to capture organisations that may be advocating for marginalised groups. Other categories against which to compare the contribution of experts, representative and NFPs were also developed based on identifiable textual features and appearances in reference dictionaries. The full set of categories ultimately used for classification is shown in Table 3.

Table 3: Categories for submitter classification

|

Category

|

Description

|

Rules

|

|---|---|---|

|

Company

|

Company

|

Contains ‘pty, ltd’ or matches with public or private

company

|

|

Confidential

|

Name not published by Committee.

|

Contains confidential or name withheld

|

|

Department

|

State, territory or Commonwealth department

|

Contains ‘department, attorney general, ombudsman’

|

|

Expert

|

Individual with some form of expertise

|

Contains ‘professor, dr, royal college’ or is based at a

‘university’

|

|

Government

|

Other local, state, territory or Commonwealth entity

|

Contains ‘government, council, city of, commission’ or matches

with a known Government Entity

|

|

Individual

|

Not any other category and matches person

|

Matches names or contains ‘mr, mrs, ms, miss’

|

|

Legal casework

|

Organisation conducting legal casework

|

Recognised legal casework provider or contains ‘legal

service’

|

|

Legal expert

|

Specialist legal organisation

|

Contains ‘Law Society, Bar Association, Law Council’ or

recognised legal experts

|

|

NFP

|

Not-for-profit

|

Matches known charity organisation

|

|

Other business

|

Business other than ‘company’

|

Matches with business type other than company

|

|

Representative

|

Entity that represents a particular interest group

|

Contains ‘union, association’

|

|

Research

|

Research institute

|

Recognised research institute or contains ‘research’

|

|

Other

|

Not matching any other category

|

|

The process of classifying the citations and linking submissions by the same submitter was iterative, and at several stages required manual input to improve the accuracy of the classification and the reference dictionaries. This is consistent with the methodology used by similar projects undertaking content analysis and parsing of datasets in specific fields,[82] as human input of domain-specific knowledge is essential to produce meaningful results.[83]

Furthermore, a number of machine learning and other methods were trialled for classification and matching but ultimately rejected due to the high rate of false positives and higher computation time.[84]

The following steps were involved in the entity matching and classification.

Submissions were classified based on obvious textual patterns. For example, submissions containing ‘Pty Ltd’ were classified as ‘company’ and those containing ‘Professor’ or ‘Dr’ were classified ‘expert’. These relatively simple methods are bound to have false positives and to miss certain entities entirely. However, they aim to extract as much data from the submitter name as possible and are appropriate so long as their limitations are clearly stated – for example, ‘expert’, given the context, simply indicates a person with some form of expertise (possibly medical), rather than an expert on the subject matter of the inquiry.[85]

Three different external datasets were used to assist in the classification of submitter names:

• First, the ABN Bulk Extract dataset was obtained, containing the names, Australian Business Number (‘ABN’) and ‘Entity Type’ of all registered Australian businesses.[86] This list contained over 9 000 000 records, and classifies businesses into 143 entity types, including Commonwealth, State, Territory and Local Government Entities, public or private companies, and partnerships.[87]

• Second, the Australian Charities and Not-For-Profits Commission (‘ACNC’) register records the ABN, name charity size, and various other attributes about all registered charities and NFPs.[88]

• Third, various publicly available lists of common first and last names were combined, the most useful being common first names in South Australia since 1944.[89] These were combined with first and last names from registered ‘Individuals’ in the ABN dataset.

The ABN and ACNC datasets were combined to form an ‘entity’ dataset.

The first barrier to matching different submissions by the same submitter is slight differences in the way their name is recorded by the committee. Therefore, the names were standardised by converting to lower case, removing frequently occurring words in the English language, known as ‘stopwords’,[90] removing all punctuation, and replacing common phrases, especially State and Territory names, with their abbreviations. Further, where a surname was found to be followed by a comma, this was moved to the end of the name. Examples of what this process looks like identified through the validation process are shown in Table 4.

Table 4: Entity standardisation.

|

Original Name

|

Standardised

|

|

New South Wales Aboriginal Education Consultative Group Inc.

|

nsw aboriginal education consultative group

|

|

Bowden, Ms Natasha

|

natasha bowden

|

|

The Australian Institute of Marine and Power Engineers

|

australian institute marine power engineers

|

This standardisation was applied both to the list of submitter names and the reference dictionaries.

Different submissions were matched with each other where their standardised names were identical or where one standardised name was wholly contained within another. Submissions were matched with the entity dataset if the standardised entity name was identical to the submitter name or contained within it. Submissions were also matched if they had both been linked to the same ‘entity’.

Identical matches could be identified in a straightforward way using the merge function of the ‘pandas’ library in Python.[91]

The process for obtaining ‘contained’ matches with entities applies ‘tidy text’ principles,[92] and the following procedure.

1. Each standardised submitter name is divided into n-grams – short sequences of text of length 1, 2 ... n words, where n = length of the submission name.

2. The data is matched to the entity set, selecting only the longest n-grams.

3. Overlapping n-grams are then eliminated.

4. The data is then matched again and the process repeats until there are no more matches.

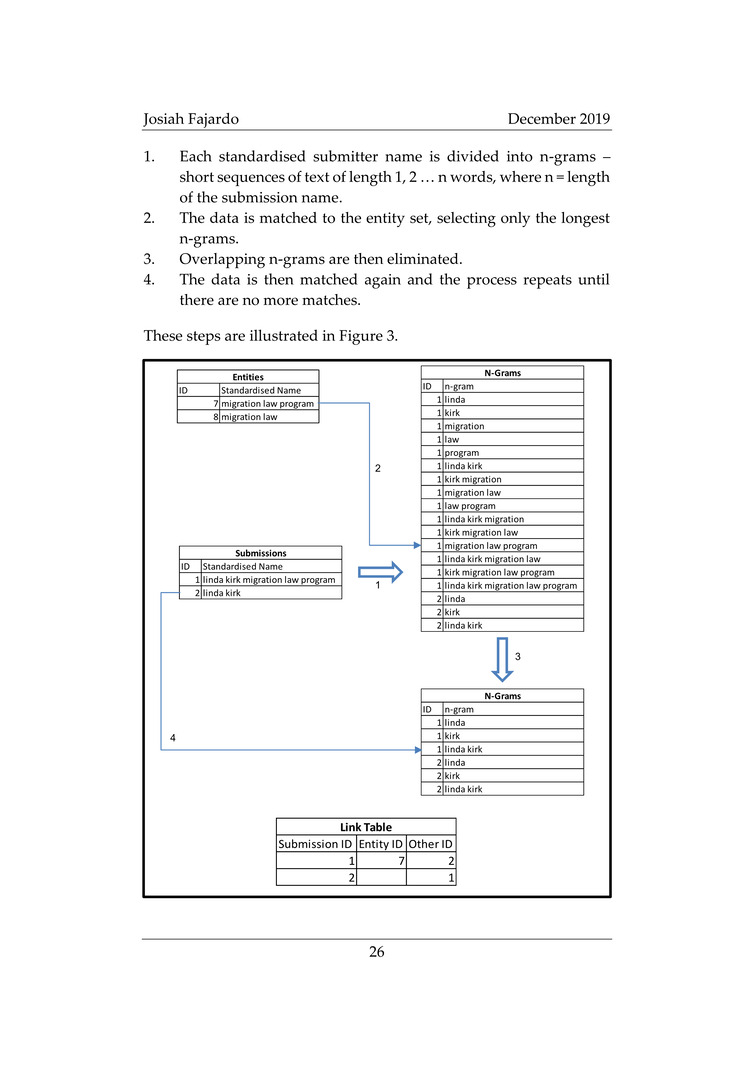

These steps are illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Contained match algorithm illustration.

Because the ABN and ACNC datasets do not necessarily follow the same naming conventions used by the committees, and because some entities, especially significant research centres within universities, do not have their own separate ABN or registered NFP, some entities are not identified using this process. These entities were identified by creating n-grams of the entire submission name table and identifying those of length four or greater which appeared more than five times. This is how many of the ‘legal expert’ bodies were identified – eg, the ‘Migration Law Program’ used as an example in Figure 3.

In addition, because some registered businesses have short, common names, such as ‘project’ and ‘training’, these return a ‘contained’ entity match even where it is very unlikely that the business with that name was the true author of the submission. To remove these entities from the ABN and ACNC dictionary, the matching algorithm was run several times, and entities with high contained match counts, no exact matches and those which, on average, made up a small percentage of the actual submitter name, were excluded.

Entities were classified using the additional typology gained by linking the ABN and ACNC datasets according to the rules in Table 3. Where a record contained at least one first and one last name and fit into no other category, these were classified as ‘individuals’.

Furthermore, universities as an ‘entity’ were removed from the final dataset, except where the submission was listed as simply on behalf of the university itself. This is because universities showed up as the highest frequency submitters, but the reality is that most of the submissions are from sub-entities or individuals within the university, and there is no suggestion that universities as institutions were considered potential ‘usual suspects’.

The classification was validated by randomly selecting a sample of entities and checking whether the classification matched what was obtained from manual inspection. The sample size was 105 submissions, which, when exact matches are included, accounts for approximately 1% of the total submission names requiring classification. While the sample was small, it was representative.[93]

The automated classification was accurate in 86.7% of cases.

In terms of the accuracy of the matching algorithm, the accuracy was scored by giving a score of 1 if the entity had been correctly matched with other submissions by the same entity, and -1 if it matched to the wrong entity. Partial scores were awarded where the matches were substantially correct and some incorrect matches were also linked (eg, ‘nt government’ linked to submissions by the Northern Territory Government alone, and with subsidiary agencies). These scores were then weighted by the number of matches each submission received.

The accuracy of the entity matching algorithm was 72.3%. This gives an indication of the extent to which the ABN, ACNC and submitter name datasets use different naming conventions or entities simply have aliases that are not accounted for. For example, a submission by ‘Optus’ was not matched since its actual business name is ‘Singtel Optus’. Other errors are due to entities that were not removed through the false positive process due to low frequency: such as an organisation called ‘Whitsunday’, which incorrectly matches with a few other submitters based in Whitsunday. This type of error has been substantially minimised through the high frequency false positive removal process, but not entirely eliminated.

The final dataset records the following properties for each submission:

• Submitter name,

• Submission number in report,

• Report ID,

• Date of inquiry completion,

• Referral date of inquiry (available for 86% of inquiries),

• Committee (by subject matter),

• Whether the inquiry was legislative,

• Type of submitter (individual, expert, etc),

• Number of citations by the same submitter or linked entities in the past 5 years, and

• Number of submissions by the same submitter or linked entities in the past 5 years.

There are a number of other variables currently linked to submitters within the dataset that merit further exploration but have not yet been validated, including:

• Sub-categories (eg, charity size, public/private/other company, commonwealth, state, territory or local government executive or department), and

• Associated state or territory.

A cross-section of the detailed results extracted from the dataset are included in Appendix A. However, a complete analysis of the citation trends for each of the 16 committees is beyond the scope of this study. Instead, what follows are some preliminary insights into the quality and diversity of information relied upon across the different committees and over time. Further, due to the distinct nature of legislative and reference committees, the data considered below only takes into account legislative committees.

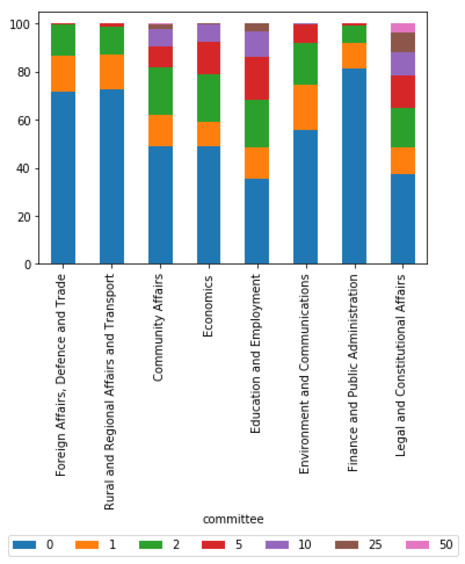

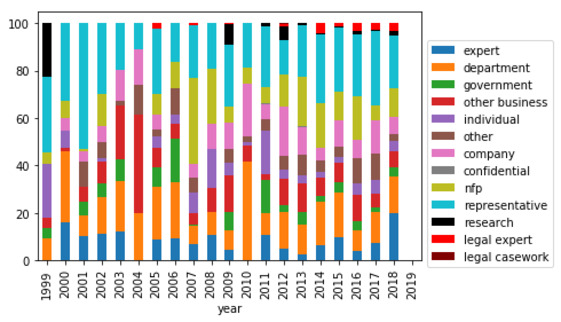

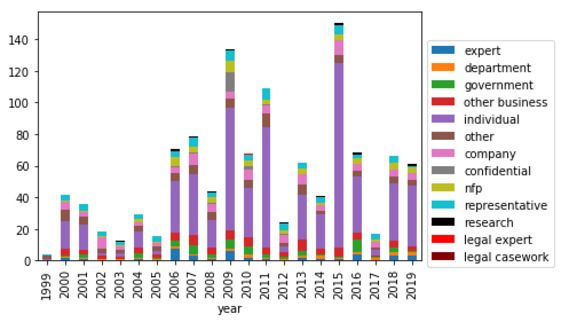

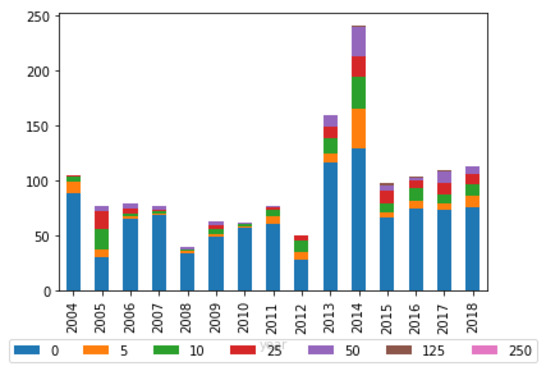

In relation to quality, the data provides some support for the view that committees tend to rely on evidence from entities that can provide them the most relevant information. The three key indications of this, clearly shown in Figure 4, are as follows.

Figure 4: Average percentage of total citations received per report by submitter type (legislative committees)

The Education and Employment Committee tends to cite representative bodies (unions and associations) more frequently than other committees. The most cited non-government entity is the Australian Council of Trade Unions.[94]

The Community Affairs Committee tends to cite NFPs significantly more frequently than other committees. Given that this Committee overseas welfare and health-related issues,[95] these NFPs are likely advocating for the rights of their constituents, and this is reflected in its most cited non-government entities being the National Welfare Rights Network and the Australian Council of Social Service (ACOSS).

The Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee tends to cite legal experts far more frequently than other committees. This is important given the subject matter of the committee is legal in nature. The five most cited non-government entities are all specialist legal organisations, with the Law Council of Australia clearly a trusted, or at least valued, contributor to this committee.

Importantly, the latter two trends appear to be strengthening over time.[96]

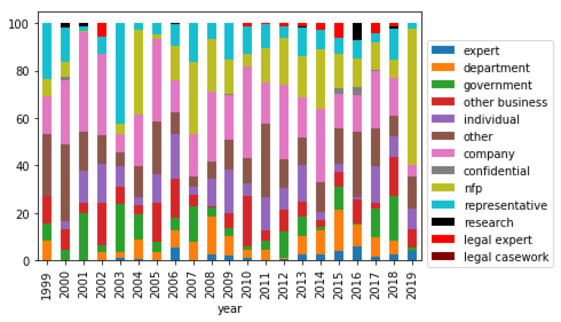

However, these results may be in part due to the fact that the more cited types of entities are also more likely to provide submissions to those committees, as illustrated by Figure 5. Nevertheless, there is no direct correlation between submissions and citations.

Figure 5: Percentage of total submissions received per report by submitter type (legislative committees)

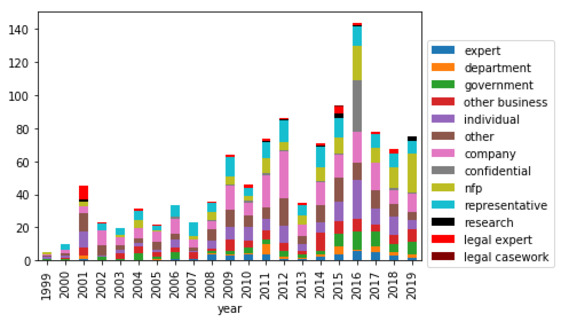

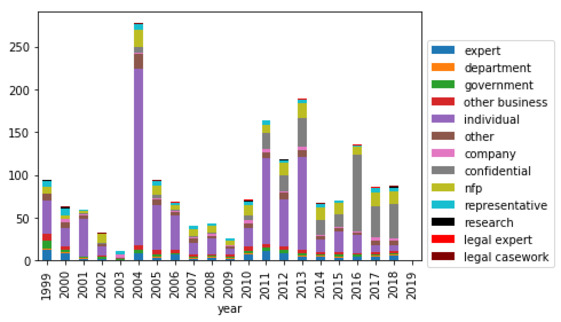

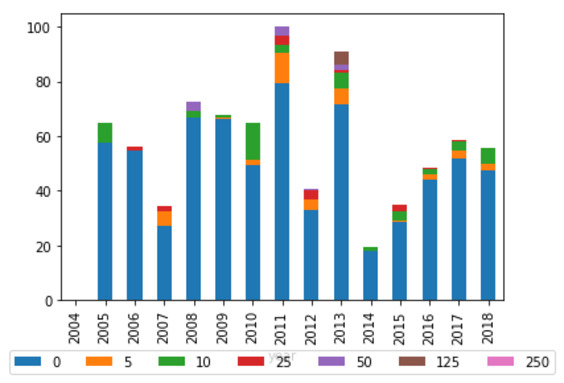

One of the key goals of this study was to determine whether the growing public participation in committees has been undermined by increased reliance on a small subset of submitters. While the graphs in Appendix A do suggest this trend over time, nearly half of all citations for all committees continue to be to submitters who have never been cited before. Averaged over the whole study period, more than half the citations for all committees except the Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee were to entities not cited before (see Figure 6). This is consistent with Marinac’s finding, discussed in Part III above, that while there may be a dominant group of submitters, the ‘market’ is still competitive and open to new entrants.

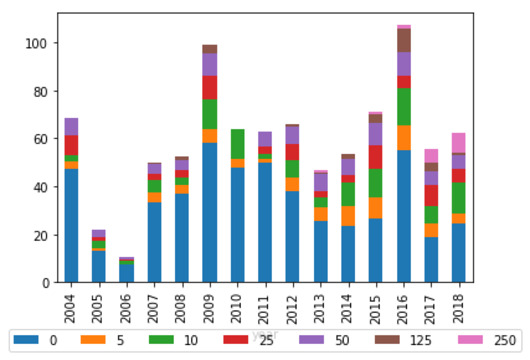

Figure 6: Average percentage of total citations received per report by number of past citations (legislative committees)

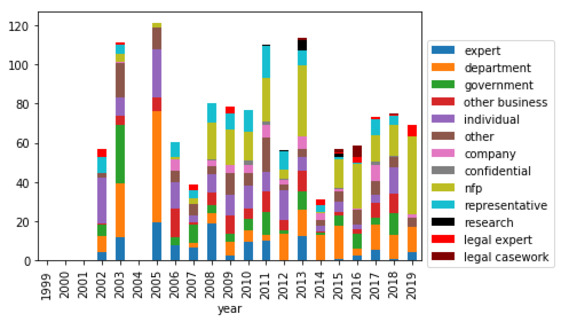

However, there may be an argument to make that persistence plays a role in whether an entity is cited. Figure 7 shows that entities which have never submitted before are less likely to be cited than entities that have merely never been cited before (as in Figure 6). Nevertheless, this may be partially due to the fact that individual persons are more likely to submit to an inquiry as a one-off occurrence, and ‘individuals’ as a category are less likely to be cited in general.

Figure 7: Average percentage of total citations received per report by number of past submissions (legislative committees)

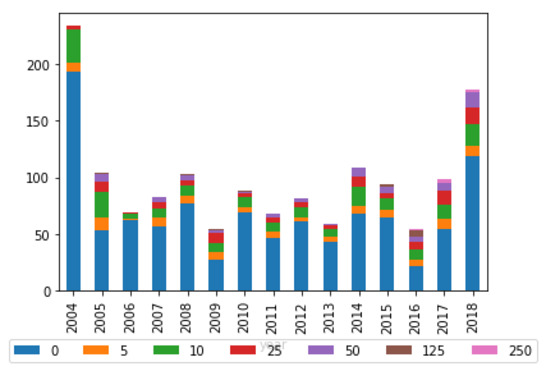

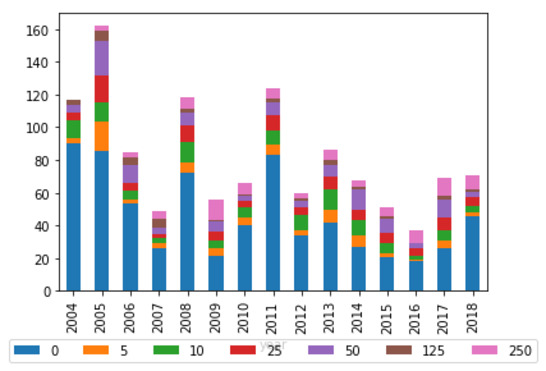

Of all the committees, the Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee seems the most vulnerable to capture by a minority of submitters. As Figure 8 indicates, a significant proportion of citations each report are made to entities that have received over 250 citations in the past five years. Given the findings in Part V(A) above, it is likely that this category represents the Law Council of Australia.

There may be nothing objectionable about an expert body of this kind providing assistance to the committee, particularly if inquiries are often of a very technical legal nature.[97] This is all the more so given that a number of citations consistently are made to entities that have never before been cited.

Figure 8: Average percentage of total citations received per report based on previous citations received, for Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee.

The fundamental limitation is that quantitative data of this kind can only provide potential pathways for further inquiry which need to be confirmed by analysis of the substantive content of the submission and reports of the committees.[98] Much of the analysis of the ‘quality’ of information relied upon by committees rests on the assumption that certain kinds of submitters supply more valuable information. While there is evidence to support this, as outlined in Part II(B)(1), a qualitative analysis of the submissions themselves is needed.

However, accepting the nature of this study as preliminary, there are four key limitations of the quantitative methods themselves:

• The level of accuracy of the matching algorithm should ideally be improved to get a more robust estimate of the way in which past citations influence future citations;

• The focus on submission citations neglects the importance of oral testimony which is requested and cited by committees;

• The citation collection did not handle multiple clustered citations in a sophisticated way – it may inflate the perceived attention received by a particular submitter cited multiple times in one place and minimise the attention received by a submitter who is cited at regular intervals throughout the report; and

• There is no consideration of what other sources committees cite apart from contributions from submissions or witnesses.

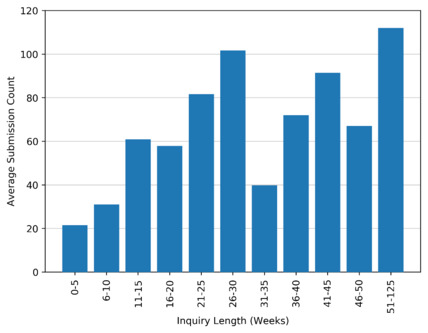

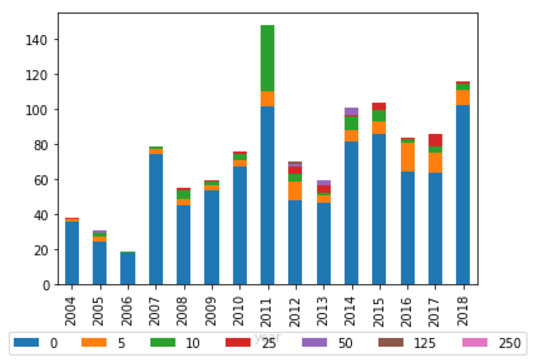

Finally, the preliminary conclusions made from the correlations and trends in the graphs and lists presented here mask the other quantitative variables that are not captured by those particular groupings of the data. For example, from the subset of legislative inquiry reports for which a referral date was successfully extracted, there was significant variation in the number of submissions received depending on the length of time over which the inquiries were conducted, as shown in Figure 9. Further exploration of these other quantitative variables is required.

Figure 9: Histogram showing average number of submissions submitted to legislation inquiries of varying lengths.

Citation analysis provides a useful method for analysing the activity of committees. The results of this study suggest that committees are judicious about which organisations receive their attention based on the subject matter of the inquiries they are addressing. It also suggests that there remains healthy competition for committee attention among organisations and individuals who are newcomers to the committee process, with committees open to citing information received from these entities.

There are several immediate pieces of further research that would provide useful insights based on the dataset assembled for this study.

First, a detailed examination of the change in citation patterns over time could be performed for each of the 16 committees.

Second, since all submissions and associated citations are linked to the date and committee associated with the inquiry, an analysis could be undertaken of how the properties of the committees themselves – such as staffing, budget and the political parties of its members – influences which entities get cited.

Finally, the reason one organisation is cited over another may rest on factors such as media attention, external documents, and other things beyond the activity of the committee itself. The dataset provides a way to identify organisations that, over time, shift from receiving little attention to receiving more attention. A case study analysis of these organisations and their actions outside the committee process could provide insight into these external factors that affect whether their voice is heard.

It is hoped that this study and more research of this nature may assist advocacy organisations in having the maximum input into the parliamentary committee process and thus strengthen the competitive framework of social policy in Australia.

Anderson, Fleur, ‘Young Home Buyers Back to Smashed Avo after No-Change Housing Inquiry’, The Australian Financial Review (online), 16 December 2016 <https://www.afr.com/news/politics/young-home-buyers-back-to-smashed-avo-after-nochange-housing-inquiry-20161216-gtcr5d>

Australian Consumer Commission, Misuse of Market Power (31 October 2018) <https://www.accc.gov.au/business/anti-competitive-behaviour/misuse-of-market-power>

Barnhart, Gordon, ‘Introduction’ in Gordon Barnhart (ed), Parliamentary Committees: Enhancing Democratic Governance (Cavendish Publishing, 1999) 1

Bates, Lyndel and Rob Hansen, ‘Parliamentary Committees Turn Road Safety Research and Ideas into Practice: Examples from Australia’ (2008) 4 International Journal of Health Promotion & Education 122

Belot, Henry, ‘Housing Affordability: Inquiry that Made No Recommendations a “Waste of Money”, Labor Says’, ABC News (online), 16 December 2016 <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-12-16/housing-affordability:-no-recommendations-from-inquiry/8127548>

Bennett Moses, Lyria, Nicola Gollan and Kieran Tranter, ‘The Productivity Commission: A Different Engine for Law Reform?’ (2015) 24(4) Griffith Law Review 657

Blanchard, Antoine, ‘Understanding and Customizing Stopword Lists for Enhanced Patent Mapping’ (2007) 29(4) World Patent Information 308

Boehmke, Bradley C, Data Wrangling with R (Springer 2016)

Christen, Peter, ‘A Survey of Indexing Techniques for Scalable Record Linkage and Deduplication’ (2012) 24(5) IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 1537

Consumers Health Forum of Australia, ‘Annual Report 2012–2013’ (2013)

Dalla-Pozza, Dominique, The Australian Approach to Enacting Counter-Terrorism Laws (PhD Thesis, University of New South Wales, 2010)

Dalla-Pozza, Dominique ‘Promoting Deliberative Debate? The Submissions and Oral Evidence Provided to Australian Parliamentary Committees in the Creation of Counter-Terrorism Laws’ (2008) 23(1) Australasian Parliamentary Review 39

Department of the Senate (Cth), ‘Senate Committees’ (Senate Brief No 4, April 2019) <https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Senate/Powers_practice_n_procedures/Senate_Briefs/Brief04>

Dermody, Kathleen, Ian Holland and Elton Humphery, ‘Parliamentary Committees and Neglected Voices in Society’ (2006) 74 Table 45

Electoral and Administrative Review Commission (Qld), Report on Review of Parliamentary Committees (1992)

Ferrara, Alfio and Silvia Salini, ‘Ten Challenges in Modeling Bibliographic Data for Bibliometric Analysis’ (2012) 93 Scientometrics 765

Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Legislation Committee, Parliament of Australia, Veterans’ Affairs Legislation Amendment (Veteran-centric Reforms No. 2) Bill 2018 [Provisions] (2018)

Forkert, Joshua, ‘Parliamentary Committees: Improving Public Engagement’ (Paper prepared for the ASPG Conference, Hobart, 27–30 September 2017)

Grenfell, Laura and Sarah Moulds, ‘The Role of Committees in Rights Protection in Federal and State Parliaments in Australia’ [2018] UNSWLawJl 3; (2018) 41(1) UNSW Law Journal 40

Grimmer, Justin and Brandon M Stewart, ‘Text as Data: The Promise and Pitfalls of Automatic Content Analysis Methods for Political Texts’ (2013) 21(3) Political Analysis 267

Halligan, John, Robin Miller and John Power, Parliament in the Twenty-first Century: Institutional Reform and Emerging Roles (Melbourne University Press, 2007)

Holland, Ian, ‘Senate Committees and the Legislative Process’ (Parliamentary Studies Paper No 7, Parliamentary Studies Centre, Australian National University, 2009)

House of Representatives Standing Committee on Economics, Parliament of Australia, Report on the Inquiry into Home Ownership (2016)

Humpreys, Ashlee and Rebecca Jen-Hui Wang, ‘Automated Text Analysis for Consumer Research’ (2017) 44(6) Journal of Consumer Research 1178

Kelly, Richard, ‘Effectiveness of Select Committees’ (Standard Note SN/PC/6499, House of Commons Library, 29 January 2013)

Khokhar, Ashfaq et al, ‘Framework for Mining and Analysis of Standardized Nursing Care Plan Data’ (2017) 39(1) Western Journal of Nursing Research 20

Lacy, Stephen et al, ‘Issues and Best Practices in Content Analysis’ (2015) 92 Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 791

Laing, Rosemary (ed), Odgers’ Australian Senate Practice – As Revised by Harry Evans (Department of the Senate, 14th ed, 2016)

Landrum, W Heath et al, ‘Citation Analysis and Trends in Knowledge Management’ (Paper No 90 prepared for the Sixteenth Americas Conference on Information Systems, Lima, Peru, 12–15 August 2010)

Leskovec, Jure, Anand Rajaraman and Jeffrey D Ullman, Mining of Massive Datasets (Cambridge University Press, 2014)

Lewis, Seth C, Rodrigo Zamith & Alfred Hermida, ‘Content Analysis in an Era of Big Data: A Hybrid Approach to Computational and Manual Methods’ (2013) 57(1) Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 34

MacGibbon, David, ‘The Future of the Committee System’ in Gordon Barnhart (ed), Parliamentary Committees: Enhancing Democratic Governance (Cavendish Publishing, 1999) 117

MacGibbon, David, ‘Witnesses’ in Gordon Barnhart (ed), Parliamentary Committees: Enhancing Democratic Governance (Cavendish Publishing, 1999) 99

Margaretten, Mark Stuart, Behavioural Models for Identifying Authenticity in the Twitter Feeds of UK Members of Parliament (PhD Thesis, University of Sussex, June 2018)

Marinac, Anthony, ‘The Usual Suspects? “Civil society” and Senate Committees’ in Kay Walsh (ed), The Distinctive Foundations of Australian Democracy: Papers on Parliament No 42 (Department of Senate, 2004) 129

Marsh, Ian, ‘Can Senate Committees Contribute to “Social Learning”?’ in Kay Welsh (ed), A Light of Reason: Papers on Parliament No 45 (Department of the Senate, 2006) 53

Maru, Olavi, ‘Measuring the Impact of Legal Periodicals’ [1976] American Bar Foundation Research Journal 227

Meuschke, Norman, Bela Gipp and Corinna Breitinger, ‘CitePlag: A Citation-based Plagiarism Detection System Prototype’ (Paper prepared for the 5th International Plagiarism Conference, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 16–18 July 2012)

Michael, Ewen J, Public Policy: The Competitive Framework (Oxford University Press, 2006)

Monk, David, ‘A Framework for Evaluating the Performance of Committees in Westminster Parliaments’ (2010) 16(1) Journal of Legislative Studies 1

Morris, Jackie and Sophie Power, ‘Factors that Affect Participation in Senate Committee Inquiries’ (Parliamentary Studies Paper 5, Crawford School of Economics and Government, Australian National University, 2009)

Ouyang, Tu et al, ‘A Large-Scale Empirical Analysis of Email Spam Detection Through Network Characteristics in a Stand-Alone Enterprise’ (2013) 59 Computer Networks 101

Parliament of Australia, Senate Standing Committees on Economics: Completed Inquiries and Reports: Completed Inquiries 1996–1999 (8 February 2018) <https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Economics/Completed_inquiries/1996-99>

Paxman, Kelly, ‘Referral of Bills to Senate Committees: An Evaluation’ in Kay Walsh (ed), Papers on Parliament No 31 (Department of Senate, 1998) 76

Pearson, Jenny & Associates, ‘Research of the Models of Advocacy Funded under the National Disability Advocacy Program’ (Final Report, Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs, 14 September 2009)

Public Interest Advocacy Organisation, ‘PIAC Annual Report 2015–2016’ (2016)

Python Software Foundation, The Python Standard Library: Regular Expression Operations (18 March 2019) <https://docs.python.org/2.7/library/re.html>

Queensland Law Society, ‘The 2010/11 Advocacy Annual’ (2011)

Ramsay, Ian and G P Stapledon, ‘A Citation Analysis of Australia Law Journals’ [1997] MelbULawRw 24; (1997) 21 Melbourne University Law Review 676

Reader, Nathaniel, ‘Assessing the Policy Impact of Australia’s Parliamentary Electoral Matters Committees: A Case Study of the Victorian Electoral Matters Committee and the Introduction of Direct Electoral Enrolment’ (2015) 68 Parliamentary Affairs 494

Reid, G S, ‘The Parliamentary Contribution to Law-Making’ in Alice Erh-Soon Tay and Eugene Kamenka (eds), Law-Making in Australia (Edward Arnold, 1980) 116

Silge, Julia and David Robinson, Text Mining with R: A Tidy Approach (O’Reilly, 2019)

Sivarajah, Uthayasankar et al, ‘Critical Analysis of Big Data Challenges and Analytical Methods’ (2017) 70 Journal of Business Research 263

Smyth, Russell, ‘What Do Trial Judges Cite? Evidence from the New South Wales District Court’ [2018] UNSWLawJl 9; (2018) 41(1) UNSW Law Journal 211

Tranter, Kieran, ‘Citation Practices of the Australian Law Reform Commission in Final Reports 1992–2012’ [2015] UNSWLawJl 12; (2015) 38(1) UNSW Law Journal 323

White, Philip B, ‘Using Data Mining for Citation Analysis’ (2019) 80(1) College & Research Libraries 76

Williams, Jacqueline, ‘The Effectiveness of Public Participation by Not-for-Profit Organisations in Australia’s Public Life through Submissions to Parliamentary Inquiries’ (Report, St Vincent de Paul Society National Council of Australia, April 2015)

Zamith, Rodrigo and Seth C Lewis, ‘Content Analysis and the Algorithmic Coder: What Computational Social Science Means for Traditional Modes of Media Analysis’ (2015) 659(1) ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 307

Australian Business Register, Reference Data (1 November 2014) <https://abr.business.gov.au/Documentation/ReferenceData>

Australian Government, ABN Bulk Extract (10 October 2018) data.gov.au <http://webarchive.nla.gov.au/gov/20181010002140/https://data.gov.au/dataset/abn-bulk-extract>

Australian Government, ACNC Registered Charities (25 October 2018) data.gov.au <https://data.gov.au/dataset/ds-dga-b050b242-4487-4306-abf5-07ca073e5594/details>

DATA.GOV, Names from Census 2000 (2 March 2018) <https://catalog.data.gov/dataset/names-from-census-2000>

Data.SA, Popular Baby Names (2 May 2019) <https://data.sa.gov.au/data/dataset/popular-baby-names>

Kaggle, English Surnames from 1849 (7 October 2016) <https://www.kaggle.com/vinceallenvince/engwales-surnames>

Sajari, Free Data: A List of First and Last Names (CSV format) (12 September 2014) <https://web.archive.org/web/20141224134311/http://blog.sajari.com/free-data/free-data-list-first-last-names/>

Python Software Foundation, ‘Python Language Reference’ (Version 2.7.15, 29 April 2018) <https://docs.python.org/release/2.7.15>

Anaconda Inc, ‘Miniconda Software Distribution’ (Version 4.6.13, 16 April 2019) <https://docs.conda.io/en/latest/miniconda.html>

Derek Noonburg, ‘Xpdf’ (Version 4.01.01, 14 March 2019) <www.xpdfreader.com>

For full list of Python packages used, see Appendix B.

This Appendix contains the raw output from the analysis of committee activity, grouped by different variables of interest.

Table 5: Average percentage of total citations per report by category

|

|

expert

|

department

|

government

|

other business

|

individual

|

other

|

company

|

confidential

|

nfp

|

representative

|

research

|

legal expert

|

legal casework

|

|

Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade

|

5.1

|

17.3

|

5.4

|

6.5

|

15.4

|

11.8

|

8.0

|

0.5

|

17.3

|

7.1

|

0.9

|

4.6

|

0.0

|

|

Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport

|

0.8

|

14.0

|

5.4

|

9.8

|

11.9

|

8.2

|

17.2

|

0.0

|

9.0

|

21.8

|

1.6

|

0.2

|

0.0

|

|

Community Affairs

|

5.3

|

14.4

|

5.9

|

5.7

|

7.4

|

7.0

|

8.6

|

1.0

|

29.9

|

12.2

|

0.8

|

1.5

|

0.2

|

|

Economics

|

3.4

|

3.0

|

4.7

|

10.3

|

8.3

|

13.7

|

21.8

|

0.7

|

11.9

|

17.9

|

0.8

|

3.5

|

0.0

|

|

Education and Employment

|

7.6

|

15.7

|

5.2

|

9.1

|

5.1

|

6.2

|

9.4

|

0.0

|

13.9

|

24.9

|

1.5

|

1.3

|

0.0

|

|

Environment and Communications

|

1.9

|

7.3

|

8.3

|

8.5

|

9.6

|

13.9

|

22.3

|

0.4

|

15.6

|

10.4

|

0.4

|

1.5

|

0.0

|

|

Finance and Public Administration

|

8.4

|

19.0

|

12.5

|

4.1

|

15.8

|

11.0

|

4.8

|

0.3

|

11.3

|

9.4

|

0.0

|

3.3

|

0.1

|

|

Legal and Constitutional Affairs

|

4.4

|

13.0

|

15.1

|

9.3

|

6.5

|

8.1

|

4.6

|

0.7

|

14.7

|

6.6

|

0.2

|

15.3

|

1.6

|

Table 6: Most Frequently Cited Non-Government Entity Submitters by Committee

|

Committee

|

Name

|

Citations

|

|---|---|---|

|

Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade

|

Medical Association for Prevention of War, Australia

|

44

|

|

Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade

|

The Returned and Services League of Australia Limited

|

38

|

|

Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade

|

Export Council of Australia

|

36

|

|

Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade

|

Slater and Gordon Lawyers

|

33

|

|

Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade

|

Community and Public Sector Union (CPSU)

|

31

|

|

Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport

|

Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA)

|

85

|

|

Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport

|

Greenpeace Australia Pacific

|

52

|

|

Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport

|

National Farmers' Federation

|

51

|

|

Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport

|

Qantas Airways Limited and Jetstar

|

50

|

|

Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport

|

Australian Transport Safety Bureau

|

48

|

|

Community Affairs

|

National Welfare Rights Network

|

252

|

|

Community Affairs

|

Australian Council of Social Service (ACOSS)

|

251

|

|

Community Affairs

|

National Social Security Rights Network

|

134

|

|

Community Affairs

|

Australian Medical Association

|

126

|

|

Community Affairs

|

Law Council of Australia

|

93

|

|

Economics

|

Law Council of Australia

|

224

|

|

Economics

|

Australian Bankers' Association

|

158

|

|

Economics

|

Financial Services Council

|

130

|

|

Economics

|

The Association of Superannuation Funds of Australia Limited (ASFA)

|

129

|

|

Economics

|

Business Council of Australia (BCA)

|

108

|

|

Education and Employment

|

Australian Council of Trade Unions

|

389

|

|

Education and Employment

|

Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry

|

278

|

|

Education and Employment

|

Australian Industry Group

|

197

|

|

Education and Employment

|

ACTU

|

117

|

|

Education and Employment

|

Master Builders Australia

|

110

|

|

Environment and Communications

|

Australian Conservation Foundation

|

127

|

|

Environment and Communications

|

Telstra

|

93

|

|

Environment and Communications

|

Law Council of Australia

|

72

|

|

Environment and Communications

|

Free TV Australia

|

67

|

|

Environment and Communications

|

WWF-Australia

|

61

|

|

Finance and Public Administration

|

National Native Title Council

|

39

|

|

Finance and Public Administration

|

Australian Medical Association (AMA)

|

28

|

|

Finance and Public Administration

|

Community and Public Sector Union

|

26

|

|

Finance and Public Administration

|

Association of Former Members of the Parliament of Australia

|

26

|

|

Finance and Public Administration

|

Law Council of Australia

|

26

|

|

Legal and Constitutional Affairs

|

Law Council of Australia

|

1633

|

|

Legal and Constitutional Affairs

|

NSW Council for Civil Liberties

|

244

|

|

Legal and Constitutional Affairs

|

Australian Lawyers for Human Rights

|

242

|

|

Legal and Constitutional Affairs

|

Australian Privacy Foundation

|

241

|

|

Legal and Constitutional Affairs

|

Law Institute of Victoria

|

209

|

Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade

Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport

Community Affairs

Economics

Education and Employment

Environment and Communications

Finance and Public Administration

Legal and Constitutional Affairs

Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade

Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport

Community Affairs

Economics

Education and Employment

Environment and Communications

Finance and Public Administration

Legal and Constitutional Affairs

Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade

Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport

Community Affairs

Economics

Education and Employment

Environment and Communications

Finance and Public Administration

Legal and Constitutional Affairs

Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade

Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport

Community Affairs

Economics

Education and Employment

Environment and Communications

Finance and Public Administration

Legal and Constitutional Affairs

Table 7: List of Python packages used.

|

Name

|

Version

|

Build

|

Channel/Source

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

alabaster

|

0.7.12

|

py_0

|

conda-forge

|

|

asn1crypto

|

0.24.0

|

py27_1003

|

conda-forge

|

|

astroid

|

1.6.5

|

py27_0

|

conda-forge

|

|

attrs

|

19.1.0

|

py_0

|

conda-forge

|

|

babel

|

2.6.0

|

py_1

|

conda-forge

|

|

backports

|

1

|

py_2

|

conda-forge

|

|

backports.functools_lru_cache

|

1.5

|

py_1

|

conda-forge

|

|

backports.shutil_get_terminal_size

|

1.0.0

|

py_3

|

conda-forge

|

|

backports.shutil_which

|

3.5.2

|

py_0

|

conda-forge

|

|

backports_abc

|

0.5

|

py_1

|

conda-forge

|

|

beautifulsoup4

|

4.7.1

|

py27_1001

|

conda-forge

|

|

blas

|

1

|

mkl

|

|

|

bleach

|

3.1.0

|

py_0

|

conda-forge

|

|

blinker

|

1.4

|

py_1

|

conda-forge

|

|

boto

|

2.49.0

|

py_0

|

conda-forge

|

|

boto3

|

1.9.73

|

pypi_0

|

pypi

|

|

botocore

|

1.12.73

|

pypi_0

|

pypi

|

|

bz2file

|

0.98

|

pypi_0

|

pypi

|

|

ca-certificates

|

2019.3.9

|

hecc5488_0

|

conda-forge

|

|

certifi

|

2018.11.29

|

pypi_0

|

pypi

|

|

cffi

|

1.12.2

|

py27h4d4881a_1

|

conda-forge

|

|

chardet

|

3.0.4

|

pypi_0

|

pypi

|

|

cloudpickle

|

0.8.0

|

py_0

|

conda-forge

|

|

colorama

|

0.4.1

|

py_0

|

conda-forge

|

|

configparser

|

3.7.3

|

py27_1

|

conda-forge

|

|

cryptography

|

2.6.1

|

py27h4d4881a_0

|

conda-forge

|

|

cycler

|

0.10.0

|

py_1

|

conda-forge

|

|

cymem

|

1.31.2

|

py27hc56fc5f_1000

|

conda-forge

|

|

cytoolz

|

0.9.0.1

|

py27h0c8e037_1001

|

conda-forge

|

|

datasketch

|

1.4.3

|

pypi_0

|

pypi

|

|

decorator

|

4.3.2

|

py_0

|

conda-forge

|

|

defusedxml

|

0.5.0

|

py_1

|

conda-forge

|

|

dill

|

0.2.9

|

py27_0

|

conda-forge

|

|

docutils

|

0.14

|

pypi_0

|

pypi

|

|

entrypoints

|

0.3

|

py27_1000

|

conda-forge

|

|

enum34

|

1.1.6

|

py27_1001

|

conda-forge

|

|

freetype

|

2.6.3

|

vc9_1

|

conda-forge

|

|

functools32

|

3.2.3.2

|

py_3

|

conda-forge

|

|

futures

|

3.2.0

|

pypi_0

|

pypi

|

|

fuzzywuzzy

|

0.17.0

|

py_0

|

conda-forge

|

|

gensim

|

3.5.0

|

pypi_0

|

pypi

|

|

git

|

2.21.0

|

0

|