|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal Student Series |

POWER, POLITICS, AND FIELD-LEVEL PENETRATION: A THEORETICAL APPROACH TO CIRCLE SENTENCING IN NEW SOUTH WALES

SARVAM KHANNA

The rules propounded by ‘peak’ legal agencies, including precedents and statutory regimes, are only as effective at the ‘field level’ as the law allows them to be.[1] This manifests as an incongruence between Roscoe Pound’s ‘law in the books’ and ‘law in action’ approaches to understanding legal processes,[2] and is especially apparent in the case of circle sentencing as a means of alternative, restorative justice for Indigenous offenders in New South Wales (‘NSW’). When society is seen as intrinsic to the formation of law,[3] or where law is seen as reflecting societal standards,[4] the needs of marginalised communities within broader society that have plural or differing values will often be overlooked. This is especially true for Indigenous communities and understandings of justice.

This essay’s approach to understanding the role of power in restorative justice processes, specifically circle sentencing of Indigenous offenders in NSW’s Local Courts, is rooted in Legal Realism. It applies a comparative Law and Society (‘L&S’) and Law and Anthropology (‘L&A’) lens to argue that theories are most effective as a tool for sociolegal change when considered in light of pluralised perspectives, including Indigenous epistemologies, rather than in purely abstract silos. Part II provides an overview of the history of circle sentencing and its current implementation in NSW.[5] Part III provides a foundation of the relevant theoretical discourse in the L&S and L&A movements, including differing conceptual understandings of power and approaches to plural legalities. This ‘conversation’ between theories informs Part IV’s detailed analysis of the concept of state power and the over-politicisation of circle sentencing, suggesting that the law’s treatment of circle sentencing has limited its effectiveness at the field level.[6] Part V then provides commentary on the role of theory in catalysing sociolegal change.

Although there is no universally accepted definition of ‘restorative justice,’ legal scholars have described it as a process focused on repairing harm and rehabilitating offenders by addressing the underlying causes of criminality.[7] Two critical features of restorative justice are its social science approach to enhancing participant well-being and satisfaction[8] and its focus on balancing community protection against the autonomy of offenders and victims.[9] Arising out of the broader theory of ‘therapeutic jurisprudence,’ these features reflect the Criminal Justice System’s (‘CJS’) attempts to engage with parallel disciplines, including psychology and social science, as an alternative to purely punitive sentencing mechanisms.[10]

In the 1980s, the CJS shifted from a ‘Rehabilitation Model’ to a ‘Justice Model’ of sentencing, which prioritised ‘restoration of the CJS’ legitimacy’ and limiting over-broad discretion.[11] The Justice Model focuses on freezing an offence to a particular moment, such that extrinsic factors like an offender’s upbringing and certain criminogenic factors are made irrelevant.[12] Despite this, the re-emergence of restorative justice, including through circle sentencing, has revived the CJS’ focus on ‘restoration, reconciliation, and reintegration’ by involving community members and addressing the root causes of criminality.[13] This represents a moral and social shift in society’s attitudes towards criminality. However, punitive sentencing mechanisms have been historically entrenched in both inferior and superior courts, including positive attitudes towards incarceration as a form of deterrence. Given this entrenchment, it is unlikely that a wholly restorative or therapeutic model will prevail in the near future, meaning society must explore how therapeutic justice mechanisms, including circle sentencing, can dove-tail with the current system.

Critics of circle sentencing, and restorative justice more broadly, suggest that appropriating Indigenous worldviews across and between cultures through prescriptively regulating guidelines around circle sentencing is problematic,[14] and that there should be a greater emphasis on procedural safeguards throughout the process.[15] These critiques are further unpacked in Parts IV and V below.

B Current Framework

As a form of restorative justice, circle sentencing prioritises the participation of Indigenous communities in sentencing Indigenous offenders and has been regulated in Part 7 of the Criminal Procedure Regulation 2017.[16] The objectives of the process include but are not limited to: including members of Indigenous communities in sentencing, increasing their confidence in sentencing, and providing more appropriate sentencing options for Indigenous offenders.[17] An essential part of this third objective is affording Indigenous offenders a significant and ‘real’ form of punishment.[18] The regulation also provides ‘suitability’ criteria for circle sentencing, which limits the process to offences finalisable in the Local Court.[19] Eligible offenders must be or identify as Indigenous, are assessed for suitability by a Magistrate and an Aboriginal Community Justice Group, and must consent to participate.[20] The ‘circle sentencing group’ may include the offender, victim, support people, the prosecutor, an Aboriginal program officer, at least three members of the offender’s community, and a magistrate.[21]

Critics contend that circle sentencing constitutes a separate form of ‘Indigenous Justice’, whereby the broader concept of ‘Restorative Justice’ is more concerned with reconciling relationships than navigating the tensions between Indigenous and non-Indigenous punishment systems.[22] Harry Blagg and Thalia Anthony’s concern that circle sentencing operates ‘at the behest of mainstream sentencing regimes’ is compounded by the fact that circle sentencing is regulated underneath the NSW Sentencing Regime.[23] Applying Blagg and Anthony’s understanding, circle sentencing operates as a constituent part of a dominant Western sentencing regime, and participant autonomy is severely limited by court intervention. The entire process operates within and underneath a broader common law sentencing system, with magistrates ‘presiding over’ the circle sentencing group and remaining in control of the process at every stage.[24] This debate is especially relevant to L&A’s approach to pluralised legal regimes, as discussed in Parts IV and V below to suggest that circle sentencing mechanisms are nested in complex power dynamics that impinge not only on their effectiveness, but their capacity as a tool for the cultural and customary separation, or extrusion, of Indigenous sentencing processes from the common law.[25]

Therapeutic jurisprudence is, at its core, a set of principles that focus on real-world intervention in sentencing vulnerable offenders fairly and justly.[26] Just as theory without practice is prone to delegating itself to pure abstraction, a theory-informed approach to understanding therapeutic justice can enrich and enliven new ideas that would otherwise be limited by formalist understandings. These include, but are not limited to, strategies that attempt to address criminality at its roots rather than simply punishing criminal behaviour.[27] The analysis below explores L&S and L&A to better unpack the power dynamics and political dimensions underscoring contemporary circle sentencing discourse. Combined, these theories provide a multifaceted and society-focused approach to elucidating the role of power within the law, and this is especially helpful as a means for understanding the foundations of NSW’s current circle sentencing regime

Similarly to the development of therapeutic jurisprudence, the L&S movement approaches understanding the law through an empirical, social science perspective, with Susan Silbey positing that ‘law, legal practices, and legal institutions can only be understood as products of social context’.[28] L&S’s historical foundations stem from Friedrich Karl von Savigny’s legal positions that the law is a ‘slow, organic distillation of the spirit of a particular people,’[29] and Roscoe Pound’s notion of the distinction between ‘law in action’, describing the informal practices of legal institutions, and ‘law in the books’, describing formal, enacted, and doctrinal law.[30] The law, in this sense, is ‘all around’.[31] The L&S movement departs from prior formalistic understandings of law, looking instead to the positive question of the law as it is over normative questions of what it ought to be.[32]

A relevant consideration arising from a ‘books versus action’ perspective is Marc Galanter’s concept of ‘penetration’—or the reach and effectiveness of rules propounded by ‘peak’ agencies at the ‘field level’.[33] In the context of circle sentencing, this discussion concerns the effectiveness of sentencing rules propounded by ‘peak’ agencies, including superior courts and the legislature, at the ‘field level’. If the law’s penetrative capacity is low, ‘law in the books’ is effectively delegated to the abstract and limited from becoming ‘law in action’ at the field level.[34] While this is not to suggest that law in the books is without its uses or ineffective without practical applications, L&S prioritises the real-world applications of law over the purely formalist. Employing this theoretical understanding, the law may be useful, but cannot be effective if does not meaningfully penetrate at the field level.

Although Galanter proposes courts are peak agencies,[35] this essay will treat the Local Court as a field-level agency given its limited capacity to make and interpret rules. In its criminal jurisdiction,[36] the Local Court instead focuses on applying sentences based on rules handed down by peak agencies, including through precedent and statutory regimes. It is, therefore, a field-level agency.[37] Understanding the Local Court as a field-level agency allows a more nuanced understanding of court hierarchy as opposed to including it in the broader umbrella of ‘courts’ as peak agencies. This subsequently helps to meaningfully visualise the law’s penetrative capacity in a manner that reveals its limitations.

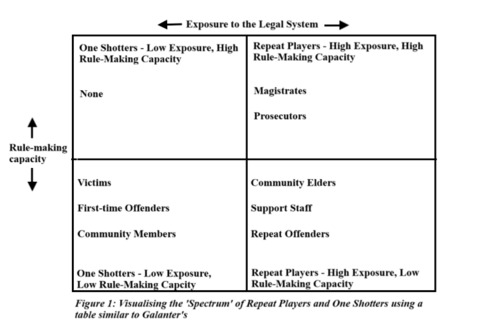

L&S also considers in detail the power dynamics present within society as a reflection of what the law is. This includes Galanter’s observations of ‘one-shotters’ (OSs) and ‘repeat players’ (RPs). OSs and RPs exist on a spectrum of power and wealth, but RPs are often capable of influencing rulemaking by carefully selecting cases and concentrating their efforts on rules and outcomes favourable to them.[38] This represents a skewing of the ‘litigation game’ toward wealthy and powerful RPs, given that the rules that do effectively penetrate are likely to align with the RP’s efforts.[39] In the context of circle sentencing, the powerful RPs represent magistrates and prosecutors, with the other involved parties representing either OSs (e.g. victims, first-time offenders, some community members) or low-level RPs (e.g. support people, repeat offenders, and community elders). An analysis of RP dynamics in circle sentencing helps elucidate where power lies in the process, and this is a valuable means of understanding potential future directions. This is unpacked in detail in Parts IV and V below.

B Law and Anthropology

In contrast to L&S, L&A theorists perceive law as a relationship between institutions and members of society, or as an ‘aggregation of principles, norms, ideas, rules, practices and [legal activities] backed by political power and legitimacy’.[40] Brian Tamanaha argues L&A is encompassed within the broader L&S,[41] propounding an earlier view held by E. Adamson Hoebel that society and culture can inform us of the place of law within the ‘total structure’.[42] Sally Falk Moore expands on L&S’ ideas by proposing that ‘rules’ of law are effective because of societal acceptance. That is, social context affords power to legal and non-legal (or informal) rules,[43] and law equally shapes society.[44] In doing so, Moore errs against Pound’s L&S view that the law is a tool for ‘social engineering’ by suggesting that the law has a complex relationship with human society rather than holding all-encompassing power over it.[45] This highlights an incongruency between L&A and L&S, but comparing the complementary aspects of both theories, including perspectives on where power rests, is an effective means of gaining a holistic understanding of the issue.

This complex relationship presents a point of discord between L&A and L&S. Where L&S scholars use a ‘top-down approach’ that attributes legal institutions as the rulemaking ‘peak,’[46] L&A scholars explore a quasi-horizontal approach involving a mutual interplay between rulemaking and adherence to rules within ‘semi-autonomous social fields’ (SASFs).[47] An SASF may generate internal rules, customs, and symbols in conjunction with obligations that inform their members’ actions but are still subject to the rules of the wider world.[48] In an SASF with plural legalities, complete autonomy or dominance is unlikely, if not impossible.[49] This ‘legal order’ of refractory pressure exertion has practical applications when considering the pluralised values and legal systems present within our own, [50] especially how Indigenous epistemologies, circle sentencing, and customary law interact with the common law.[51] When viewed as fundamental to any legal system, plural legal orders, or ‘inter-legalities,’ can help inform the success of regulatory layers developed through public and private governance and provides an avenue of complementation with the L&S concept of penetration.[52] A legal system like Indigenous customary law will necessarily have differing definitions of what appropriate sentences are, meaning a seemingly successful sentencing regime developed by the Western mind is unlikely to enjoy the same success in Indigenous communities.

Another underlying focus of L&A is dispute resolution, including alternative dispute resolution (‘ADR’). L&A indirectly explores the penetration of rules surrounding dispute resolution outside court as a means of maintaining specific social orders.[53] In accommodating dispute resolution mechanisms under existing common law frameworks, the law reproduces knowledge that reinforces existing hegemonies,[54] indirectly reflecting dominant groups' interests.[55] For example, customary forms of sentencing, including circle sentencing, are subsumed by the dominant common law system, such that any attempt at reconciling the two is curbed by dominant colonial hegemonies.

Theoretical understandings like L&A also provide avenues for reformulating power dynamics and understanding new forms of power, as mentioned above, like Indigenous epistemologies. This includes Indigenous understandings of space as a primary attractor around which all relationships are conceived and a conscious, living thing.[56] In this context, ‘new’ refers not to novel forms of power but those that exist in discord with the current hegemonic power. The concept of law as a double-edged sword, which both reinforces hegemonies and provides avenues to question these, is discussed in detail in Part V below.[57]

Applying the theoretical discourse outlined above to the real-world, field-level example of circle sentencing, issues arise regarding the implications of Pound’s ‘books versus action’ distinction,[58] the politicisation of Indigenous issues and relevant power dynamics, and pluralised legalities.[59] This section analyses circle sentencing’s theoretical dimensions. Part V below explores the concept of law as a tool for social change and how the law can account for inter-legalities.

As mentioned, L&S and L&A take similar approaches to understanding the law. However, their differences enable external interpreters to understand the nuanced application of ‘law in the books’ (the abstract rules) to ‘law in action’ (the field level) in the circle sentencing context. In this sense, ‘law in the books’ refers to broader sentencing regimes in NSW and the subsequent development of circle sentencing regulation.[60] ‘Law in action’ refers to implementing and applying these rules through the circle sentencing process.

Circle sentencing can provide a safe space for victims and offenders and, in some cases, reduce reoffence.[61] However, the law’s penetrative capacity is severely limited by resource allocation,[62] difficulties communicating through barriers constructed by uneven power dynamics, and difficulties arising from the politicisation of circle sentencing which reduces public confidence in its effectiveness. One such political threat to circle sentencing is the oversimplified assertion that it is ‘soft’ or excessively lenient on crime.[63] This has been proven false in practice,[64] but the political pressure remains, leaving the process at constant risk of abolishment. An issue arises here under an instrumentalist L&S approach of conflicts of understanding within society. Where the ‘content and form of law [are] seen as an epiphenomenon of the balance of power within society,’ these power balances dictate societal understandings of law.[65] This presents an issue in both the L&S view of OSs and RPs and the L&A view of pluralised legalities. Where the former considers the key actors in the exercise of power, the latter considers the exercise of power within an SASF to determine modes of change and evolution.

Galanter’s conception of RPs and OSs within legal institutions and on either side of a dispute is helpful in understanding where exactly the power lies in sentencing Indigenous offenders. As mentioned in Part III above, Galanter described RPs as a spectrum, wherein most parties with power are RPs by default, but not all RPs are powerful. [66] Bahaar Hamzehzadeh provides an example of this, using a corporate superstore (Walmart) to represent an RP in a shopping complex, which implements rules and a ‘new order’ that small business owners, employees, and customers must react to.[67] Here, customers and small-business owners are limited in their rule-making capacity and power, but are nonetheless RPs due to their repeat involvement in the shopping complex. Similarly, in circle sentencing, although several players may come in repeat contact with the CJS, those with indirect rulemaking capacity include magistrates and prosecutors as repeat representatives of the court system. Magistrates have the power of control over a circle sentencing group meeting, even without full authority to decide its outcome, through their power to determine participant suitability and commence or terminate meetings if deemed necessary.[68] In this sense, the magistrate continues to ‘preside’ over the meeting, meaning circle sentencing does, in fact, operate at the mainstream sentencing regime’s behest and not as a true diversionary alternative.[69] A potential benefit of a presiding magistrate would be the procedural fairness afforded to offenders and victims under the common law trial process. However, the impact of this power dynamic is that circle sentencing and restorative justice more broadly, represent ‘tools of the [racist] colonising state’ that only possess limited power to mitigate harmful exposure to the CJS.[70] Hence, RPs involved in circle sentencing continually exert their dominant power by ‘controlling’ the process and indirectly advancing the colonial state’s interests.

An L&A approach would focus less on the individual actors involved but rather on how power is distributed within the relevant SASF. This differs from the ‘top-down’ L&S perspective, wherein courts (or other dominant institutions) exert power, presenting a multi-layered, quasi-horizontal relationship to illustrate power flow. Circle sentencing presents difficult circumstances to apply the SASF concept due to pluralised values across Indigenous communities and between the Common Law and Indigenous customary law. This ‘double plurality’ is explored in greater detail in Part V below. The former plurality embodies a significant critique of the process, as some scholars see prescriptive circle sentencing regulation as appropriating Indigenous worldviews across cultures and communities.[71] Moore’s definition may, therefore, apply to individual Indigenous communities as individual SASFs rather than the inaccurate and over-broad social field of ‘Indigenous peoples’.[72] Despite the millennia-long development of Indigenous customary law and Indigenous understandings of relationships and punishment, the imposition of norms developed by peak Western agencies tends to ‘impinge on the [SASF’s] rules and customs’.[73] An L&A scholar would perceive the regulation process surrounding circle sentencing as an attempt at social control despite its apparent end goal being reconciliation and limiting exposure to the CJS.[74] The regulation further represents an attempt to reconcile the inter-legality between the common law and Indigenous customary law by incorporating the latter into the former, restricting the Indigenous community’s law-making autonomy. The effects of this are unpacked in Part V below.

The above analysis of circle sentencing regulation through L&S and L&A highlights several limitations in the current approach, focusing on intrinsic power dynamics and politics. Issues arise regarding whether, in light of these, the statutory rules effectively penetrate at the field level and whether the present inter-legalities represent conflicts in the purposes and means of effective sentencing across legalities. The two issues are interlinked, given that the effectiveness of circle sentencing is restricted by common law courts, which subsume it as a mere alternative to ‘mainstream’ sentencing.[75] The power dynamics explained above are not immediately apparent, meaning applying theory to the law as it is reveals critical limitations that may inform future reform directions.[76]

Part IV, above, explored in detail how L&S and L&A provide differing perspectives to unveil the issues arising from NSW’s circle sentencing regime. This section continues that discussion, exploring how law can look beyond present issues toward sociolegal advancement using a theoretical lens. The critiques of the circle sentencing model outlined above include power imbalances, politicisation, subsumption by colonial systems,[77] penetrative effectiveness, and the appropriation of Indigenous worldviews.[78]

The first step to addressing plural legalities in the L&A approach would be meaningfully acknowledging and respecting Indigenous understandings of space, time, and knowledge. However, the ‘double plurality’ between common law and customary law and between Indigenous communities, as described in Part IV above, presents roadblocks to reform aiming to provide Indigenous communities significant autonomy in trying and sentencing offenders. In this sense, a major roadblock would be the difficulty in affording Indigenous customary law appropriate autonomy without shaking the foundations of common law.[79] This conundrum reinforces Moore’s view that long-established relationships, including colonial ones, are ‘difficult to do away with instantly by legislation or legal measures’.[80] While difficult, however, this ‘doing away’ is not impossible, especially given how reductionist Western epistemologies have historically ‘done away with’ Indigenous ones by imposing Western legal order.[81]

Therefore, the process of reconciling inter-legality, in this sense, will require a long-term commitment to reconciliation and extruding Indigenous Customary Law. This involves separating Customary from Common Law to afford meaningful autonomy to Indigenous communities. Notably, there can be no ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to sentencing Indigenous offenders due to shifting values of what constitutes appropriate punishment across communities. To this end, Blagg and Anthony advocate for a ‘place-based and self-determinative approach’ to circle sentencing.[82] It is also important to acknowledge the qualitative benefits of circle sentencing here, as it provides a forum for offenders to assist with healing and empower communities in a culturally appropriate manner, as well as providing culturally appropriate punishment.[83] For example, some critics claim coming face-to-face with elders is a ‘real’ punishment and can be significantly more effective than Western punishment for offenders raised in Indigenous communities with Indigenous values.[84] Elders also have the power to mitigate and manage power imbalances that arise within the group meeting.[85] However, due to the indirect and unapparent nature of the power dynamics described above, the true disassembly of these must occur from the top-down or inside-out, per the L&S and L&A approaches, respectively. An extrusion-focused approach must account for Indigenous epistemologies and allow Indigenous offenders a meaningful alternative to the CJS that appropriately mitigates the power RPs hold over the process.

In an L&A approach, the law can thus meaningfully act as a ‘double-edged sword’ that allows both those with power and those without to question the existing dynamics.[86] That is, the adoption of Indigenous understandings of the law as universal and dynamic can occur over time through the ‘mutually constitutive interaction’ of divergent worldviews.[87] Both L&S and L&A approaches accommodate shifting power. For example, if the role of the powerful, rule-making RP in circle sentencing were shifted from the magistrate and prosecutor to Indigenous communities and elders, this would provide a drastically different foundation for the sentencing of Indigenous offenders. One way to shift the power in this manner would be to move away from litigation-style trials to ADR, within which circle sentencing is included. This goes to a primary objective of circle sentencing, which is to limit Indigenous offenders’ exposure to Western legal order and afford them culturally appropriate sentences.[88] If the trying of Indigenous offenders through customary means was meaningfully extruded and separated from the common law CJS, the focus would be shifted away from litigation from the beginning rather than after the trial, as is often the case with circle sentencing. However, the more drastic the approach to extrusion, the more likely it is to face strong political opposition, as has been the case with circle sentencing reforms.[89] Therefore, any approach to reconciling the plural values must establish long-term avenues for reconciliation and acknowledgment of Indigenous epistemologies.

The above application of L&S and L&A to the real-world operation of circle sentencing in NSW provides meaningful insight into the value of utilising multiple theories in assessing the penetrative effectiveness of rules propounded by ‘peak’ legal agencies at the field level. Although the two theories provide differing perspectives on the role of power and the accommodation of inter-legalities within the law, exploring them in conjunction provides unique insight into the issues with circle sentencing and avenues for future reform that would not arise otherwise. Ultimately, ‘law in the books’ is delegated to mere abstraction without effectively translating it to ‘law in action,’ and the above theories are an effective means of analysing situations like circle sentencing and creating avenues for reform that accommodates this and increases the law’s penetrative capacity.

[1] Marc Galanter, ‘Why the “Haves” Come Out Ahead: Speculations on the Limits of Legal Change’ (1974) 9 Law and Society Review 95, 97.

[2] Jean-Louis Halperin, ‘Law in Books and Law in Action: The Problem of Legal Change’ (2011) 64 Maine Law Review 46: 46–7; Susan Silbey, ‘Law and Society Movement’ in Herbert M. Kritzer (ed), Legal Systems of the World: A Political, Social and Cultural Encyclopedia (ABC-CLIO, 2002) 860, 861.

[3] Silbey (n 2) 860.

[4] Sally Falk Moore, ‘Law and Social Change: The Semi-Autonomous Social Field as an Appropriate Subject of Study’ (1973) 7 Law and Society Review 719, 721.

[5] Most recently regulated in NSW in the Criminal Procedure Regulation 2017 (NSW) Pt 7 (‘CPR’). See also Criminal Procedure Amendment (Circle Sentencing Intervention Program) Regulation 2003 (NSW); Criminal Procedure Amendment (Circle Sentencing) Regulation 2009 (NSW).

[6] Galanter (n 1) 97.

[7] David Brown et al, Criminal Laws: Materials and Commentary on Criminal Law and Process of New South Wales (Federation Press, 7th Ed, 2020) 1274–5.

[8] Astrid Birgden, ‘Therapeutic Jurisprudence and Offender Rights: A Normative Stance is Required’ (2009) 78 Revista Jurídica de la Universidad de Puerto Rico 43, 43–5.

[9] Ibid 43.

[10] Brown et al (n 7) 387.

[11] Ibid 1263.

[12] Brown et al (n 7) 1263; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), Juvenile Justice and Youth Welfare: A Scoping Study (Report No 6, 1998) 4.

[13] Brown et al (n 7) 1274–5; Allan Borowski and Ian O’Connor (eds), Juvenile Crime, Justice and Corrections (Addison Wesley Longman Australia, 1997) 227.

[14] Juan Marcellus Tauri, ‘Indigenous Peoples and the Globalisation of Restorative Justice’ (2016) 43 Social Justice 46, 53.

[15] Andrew Ashworth, ‘Responsibilities, Rights and Restorative Justice’ (2002) 42 The British Journal of Criminology 578, 582.

[16] CPR (n 5) Pt 7.

[17] Ibid reg 39(a)-(h).

[18] Elena Marchetti and Kathleen Daly, ‘Indigenous Courts and Justice Practices in Australia’ (Trends & Issues in Criminal Justice, No 277, Australian Institute of Criminology, 1 May 2004) 5.

[19] CPR (n 5) reg 33(1).

[20] Ibid reg 40(1)(a)-(e).

[21] Ibid reg 43. For a detailed summary of the circle sentencing process, see reg 34 in Appendix A.

[22] Marchetti and Daly (n 18) 4; Harry Blagg and Thalia Anthony, Decolonising Criminology: Imagining Justice in a Postcolonial World (Palgrave Macmillan, 2019) 262–3.

[23] Brown et al (n 7) 1363, citing Blagg and Anthony (n 22). The ‘mainstream sentencing regime’ above refers to the rules propounded in the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act 1999 (NSW) (‘Sentencing Act’).

[24] CPR (n 5) reg 43(1)(a).

[25] Noting the ordinary definition of extrusion, which refers to the formation of a new object through ‘pushing [it] out’ of an initial one. In this essay, ‘extrusion’ refers to the re-emergence of Indigenous Customary Law from the colonially imposed common law, by which it has historically been subsumed, encompassed, and disempowered.

[26] Brown et al (n 7) 42–3.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Silbey (n 2) 860 (emphasis added).

[29] Cited in Silbey (n 2) 860.

[30] Halperin (n 2) 46-7; Silbey (n 2) 861.

[31] Austin Sarat, ‘“...The Law is All Over”: Power, Resistance and the Legal Consciousness of the Welfare Poor’ (1990) 2 Yale Journal of Law & the Humanities 343: 343–6.

[32] Silbey (n 2) 860.

[33] Galanter (n 1) 97.

[34] John Lande, ‘An Appreciation of Marc Galanter’s Scholarship’ (2008) 71 Law and Contemporary Problems 147, 149.

[35] Ibid 137–8.

[36] Local Court Act 2007 (NSW) s 9(c).

[37] Galanter (n 1) 96.

[38] Galanter (n 1) 125.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Moore (n 4) 719.

[41] Brian Tamanaha, Law as a Means to an End (Cambridge University Press, 2006) 123.

[42] Cited in Moore (n 4) 719.

[43] Ibid 720.

[44] Ibid 719–20.

[45] Ibid 719.

[46] Galanter (n 1) 96–7.

[47] Moore (n 4) 720–1.

[48] Ibid 721.

[49] Ibid 742-3.

[50] Ibid 721.

[51] Ambelin Kwaymullina and Blaze Kwaymullina, ‘Learning to Read the Signs: Law in an Indigenous Reality’ (2010) 34 Journal of Australian Studies 195, 195–6.

[52] Sally Merry and Matthew Canfield, ‘Law: Anthropological Aspects’ in Neil Smelser and Paul Baltes (eds) International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioural Sciences (Elsevier, 2nd ed, 2015) 535, 539.

[53] Ibid 535.

[54] Merry and Canfield (n 52) 537.

[55] Merry and Canfield (n 52) 537, citing Mindie Lazarus-Black and Susan Hirsch, Contested States: Law, Hegemony and Resistance (Routledge, 1st ed, 1994).

[56] Merry and Canfield (n 52) 537; Kwaymullina and Kwaymullina (n 51) 200–1. Courts recognised the approach outlined in Kwaymullina and Kwaymullina (n 51) in Mabo v Queensland (No 2) [1992] HCA 23; (1992) 175 CLR 1, [64] (Brennan J) (‘Mabo (No 2)’).

[57] Merry and Canfield (n 52) 537.

[58] Halperin (n 2) 46-7.

[59] Merry and Canfield (n 52) 539–40.

[60] Sentencing Act (n 23); CPR (n 5).

[61] Emily Doak, ‘Wagga Wagga’s move to circle sentencing benefits Indigenous offenders, community’, ABC News (online, 13 October 2023) < https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-10-13/wagga-wagga-circle-sentencing-benefits-indigenous-offender/102951528>.

[62] Michelle Lam, ‘Understanding, but No Soft Options in the Circle’ (2012) 50 Law Society Journal 27, 28.

[63] Marchetti and Daly (n 18) 5.

[64] Lam (n 62) 28–29.

[65] Tamanaha (n 41) 124; David Nelken, ‘The Gap Problem in the Sociology of Law; A Theoretical Review’ (1981) 1 Windsor Yearbook of Access to Justice 35, 46.

[66] Galanter (n 1) 107. See also Figure 1 in Part III.

[67] Bahaar Hamzehzadeh, ‘Repeat Player vs. One-Shotter: Is Victory All that Obvious?’ (2010) 6 Hastings Business Law Journal 239, 239-40.

[68] The power to determine suitability is outlined in CPR (n 5) reg 34(1)(a), (d) (See Appendix A). CPR (n 5) reg 46 outlines the power to terminate meetings.

[69] CPR (n 5) reg 43(1)(a); Blagg and Anthony (n 22) 262–3.

[70] Joanne Belknap and Courtney McDonald, ‘Judges’ Attitudes about and Experiences with Sentencing Circles in Intimate-Partner Abuse Cases’ (2010) 52 Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice 369, 373.

[71] Tauri (n 14) 53 (emphasis added).

[72] Moore (n 4) 720–1.

[73] Ibid 723 (emphasis added).

[74] Ibid 731.

[75] Brown et al (n 7) 1363.

[76] Silbey (n 2) 860.

[77] Brown et al (n 7) 1357.

[78] Tauri (n 14) 53.

[79] See also Brennan J’s discussion in Mabo (No 2) (n 56) [29] of the Common Law ‘skeleton of principle’. Here, the High Court of Australia grappled with whether the Court could meaningfully adopt rules that contradict the ‘skeleton of [common law] principle’ surrounding the granting of land rights to Indigenous communities. This circumstance is parallel to the adoption of circle sentencing regulation, such that the prescriptive adoption of sentencing regimes contradictory to the ‘mainstream’ could be perceived as catastrophic for the common law ‘skeleton of principle’. This is, naturally, a significant roadblock to the adoption of Indigenous sentencing mechanisms.

[80] Moore (n 4) 739.

[81] Kwaymullina and Kwaymullina (n 51) 197.

[82] Blagg and Anthony (n 22) 258.

[83] Brown et al (n 7) 1365; CPR (n 5) reg 39(d).

[84] Marchetti and Daly (n 18) 5.

[85] Elena Marchetti, ‘Indigenous Sentencing Courts and Partner Violence: Perspectives of Court Practitioners and Elders on Gender Power Imbalances During the Sentencing Hearing’ (2010) 43 Australian & New Zealand Journal of Criminology 263, 268.

[86] Merry and Canfield (n 52) 537.

[87] Merry and Canfield (n 52) 540.

[88] Brown et al (n 7) 1365; CPR (n 5) reg 39(d).

[89] Marchetti and Daly (n 18) 5.

[90] CPR (n 5) reg 34.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/UNSWLawJlStuS/2024/8.html