|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of Technology Sydney Law Research Series |

Last Updated: 15 February 2017

CONSTITUTIONS, POPULATIONS AND DEMOGRAPHIC CHANGE[∗]

Brian Opeskin (Macquarie University, Australia)

Enyinna Nwauche (Rivers State University of Science and Technology, Nigeria)

To be published in: Mark Tushnet, Thomas Fleiner and Cheryl Saunders (eds), Routledge Handbook of Constitutional Law, (Routledge, 2012), ch 35

ABSTRACT

This chapter examines the ways in which constitutions reflect and respond to population change. This reflexive relationship is examined across four domains—the political domain addresses structural issues about government and representation; the socio-economic domain considers individuals’ decision making about fertility, mortality and migration; the ethno-cultural domain examines issues of demographic composition and ethnic diversity; and the scientific domain explores ways in which governments acquire knowledge about populations through national censuses and other means. The relationship between constitutions and populations is complex, but it deserves more attention than it has often received. If constitutions are to provide sound architectures for the governance of people far into the future, they need to have population dynamics firmly in mind in their design and subsequent evolution.

KEYWORDS

Constitutions, population, size of legislature, electoral representation, formation of states, federations, fertility, mortality, and migration, ethnic diversity, census, vital registers, national statistical institutes.

I INTRODUCTION

In late 2011 the world marked the arrival of its seventh billionth human inhabitant. It had taken just 12 years for the last billion people to be added to world population; the next billion is expected to be added within 14 years, by 2025. The United Nations projects that 2.4 billion people will be added to the world’s 2010 population by 2050. Some 97 per cent of this growth will be in less developed regions – mostly in Africa and Asia – and nearly all in urban centres. Europe, by contrast, is projected to decline in absolute population, despite significant immigration.

Changes of this scale generate significant long-term social transformations within countries, as populations change in size, composition, and spatial distribution. It might be expected that constitutions would anticipate or reflect such changes because constitutions are intended to establish an enduring legal architecture for the governance of social and political communities. While many constitutions reveal an awareness of population dynamics, for others the impact can be subtle or fragmented.

The link between constitutions and populations attracted attention in the 1970s and 1980s, after Paul Erlich’s book, The Population Bomb, generated widespread international concern about the Malthusian calamity that might arise from unchecked population growth in a world of finite resources.[1] In that context, several scholars examined how the US Constitution might regulate demographic processes, but the issue has now largely slipped from view.

This Chapter seeks to address this gap. It surveys the nature of population change, globally and in selected case studies, and then examines how population dynamics are relevant to four constitutional domains. The political domain addresses structural issues about government and representation. The socio-economic domain considers how constitutions affect populations through their effects on individuals as economic and social beings, and their decision making about fertility, mortality, and migration. The ethno-cultural domain examines how constitutions address issues of demographic composition, especially ethnic diversity. Finally, the scientific domain explores the ways in which governments acquire knowledge about populations through national censuses and other means, thus informing action within the other domains.

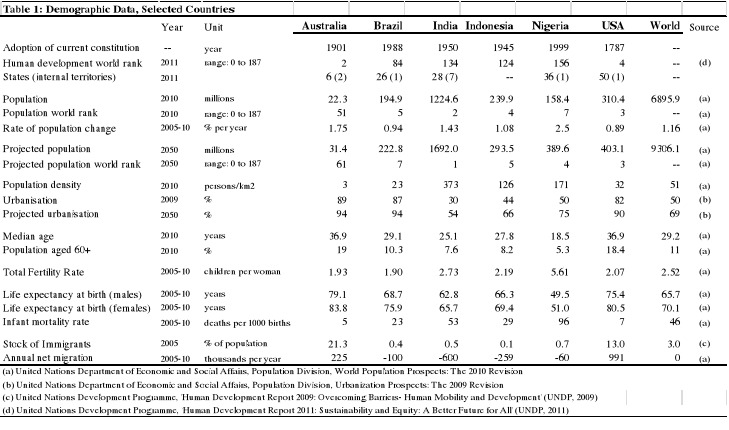

The Chapter focusses on the experience of six countries – Australia, Brazil, India, Indonesia, Nigeria and the United States – a choice informed by the desirability of including some of the most populous countries (they accounted for more than 30 per cent of global population in 2010), as well as representatives of federal and unitary states, old and new constitutions, developed and developing states, and states from different legal traditions. Other constitutions are referred to where relevant.

II THE NATURE OF POPULATION CHANGE

Four attributes of a country’s population affect constitutional design or operation: the size of the population and how it changes over time; the spatial distribution of the population; the structure or composition of the population; and the relative contribution of three population processes (fertility, mortality, and migration), which drive all population change. Demographic change is a highly complex phenomenon and what follows is no more than a sketch of its main features. Key data are presented in Table 1.

Population size

For some 200,000 years, the presence of humans on earth was scarcely noticeable because high death rates kept the population at relatively low and stable levels.[2] World population gradually reached one billion shortly after 1800, but the Industrial Revolution brought social changes that came to be reflected in greatly accelerated population growth. The change from patterns of high fertility and mortality to patterns of low fertility and mortality has been explained by the theory of the ‘demographic transition’. Better nutrition, sanitation, and medicine reduced high rates of mortality, thus removing the pressure to have large families; but the decline in fertility often lagged decades behind the decline in mortality, leading to exponential population growth in the interim. Globally, the rate of population growth peaked in 1970 at 2.07 per cent per annum. Despite the slower rate of annual growth today (1.16 per cent), substantial numbers are added to world population each year – 95 million in 2011 alone.

The demographic transition has been experienced at different times and rates in different societies, and the case studies reflect this varied experience. India and Nigeria are currently growing much faster than the global average, underpinning their projected population growth from 1.23 to 1.69 billion and from 158 to 390 million, respectively, by 2050. By that year, India is projected to be the most populous country in the world (overtaking China), and Nigeria the fourth most populous. All the case study countries will experience significant population growth between 2010 and 2050, but the population of some other countries (e.g., Russia and the Baltic states) is projected to decline. Population size has constitutional salience in the political domain because of its impact on the size of legislatures and on state formation.

Population distribution

The spatial distribution of a population responds to many factors, including differential rates of growth in different localities and the capacity to migrate internally and internationally. Globally, population density averaged 51 persons/km2 in 2010, but this masks large disparities between countries – from just 3 persons/km2 in Australia to 373 persons/km2 in India – and even larger disparities within countries.

One of the most significant demographic trends of our age is the steady urbanisation of the population, as people leave rural areas in search of employment in towns and cities. In 1800, less than 1 per cent of world population lived in cities of more than 100,000 people.[3] Today more than one-third of the world’s population live in cities of that size, 50 per cent live in towns and cities of any size, and this is projected to rise to 69 per cent by 2050. The effects of increasing urbanisation will be most pronounced in developing countries. This can be seen in the case studies, where urbanisation is projected to increase from 30 per cent to 54 per cent in India, and from 44 per cent to 66 per cent in Indonesia, over the period 2009–2050. Population distribution has constitutional salience in the political domain because of its impact on electoral representation and funding for states and other sub-national units.

Population structure

Populations vary in the proportion of males and females at different ages (the age-sex structure) and across other attributes such as education, social status, and ethnicity. With respect to age, countries in the earlier stages of the demographic transition tend to have young populations due to high fertility and low life expectancy. Nigeria and India exemplify this with their low median ages (18.5 and 25.1 years) and small aged populations. Countries that have completed the demographic transition have older populations due to low fertility and high life expectancy. Australia and the United States exemplify this with their high median ages (both 36.9 years) and a high proportion of their populations in older age groups (18-19 per cent are aged 60+). Population structure has constitutional salience in the socio-economic domain if there are mandated social protections (e.g., retirement pensions) for the elderly, or universal free education for the young. In the political domain, changing population structures also affect the size and composition of the voting-age population.

Population processes

All population change is driven by just three processes – fertility (births), mortality, (deaths) and migration. The balance between these components varies from one country to another and over time. Births and deaths are biological processes, and the balance between them reflects different stages of the demographic transition. Historically, some societies experienced fertility rates as high as 10 children per woman if no attempt was made to limit childbirth, but fertility has fallen globally since the 1970s and today averages just 2.52 children per woman. Nigeria and India exceed this average, while fertility in the other case studies is below the ‘replacement level’ of about 2.1 children per woman. Many constitutions make provision for the interrelated issues of fertility, marriage, family planning, and abortion.

Mortality has undergone an ‘epidemiological transition’, from an age of pestilence and famine when lives typically spanned 20–30 years, to an age of degenerative and man-made diseases marked by dramatically increased life span.[4] Global life expectancy at birth is now 65.7 years for males and 70.1 years for females. In Nigeria, life expectancy falls well below this average; conversely, life expectancies in Australia and the United States are among the highest in the world.

Migration is the third demographic process but its patterning is complex because it responds to fluctuating economic conditions and government policy. The cumulative impact of net international migration means that about 3 per cent of the world’s population live outside the country of their birth. For settler societies the figure is much higher – 24 per cent of the population in Australia, and 13 per cent in the United States, are migrants. Conversely, Brazil, India, Indonesia, and Nigeria experienced sizeable net emigration over the period 2005–2010. The regulation of cross-border movement is central to defining social membership, and constitutions thus routinely empower legislatures to make laws on that subject. Migration raises important constitutional questions, especially in Europe, which are dealt with in more detail elsewhere in this volume.

III POPULATION AND THE POLITICAL DOMAIN

Size of the legislature

It is a common experience that the size of legislatures in representative democracies expands over time as the population increases. This is partly a principled response to the desire to maintain a close connection between electors and their representatives, and partly a pragmatic response to the challenges faced by legislators in managing complex modern economies. However, the growth in legislatures is typically less than proportional to the growth in population because, as the size of the chamber increases, parliament is less capable of functioning as an assembly.[5] At some point, there are practical limits to further growth.

The pressure for expansion is felt most acutely in the lower chamber of bicameral systems because these are, in name or function, people’s houses. Yet, upper chambers are not necessarily immune from population pressures, especially where there is a formal nexus between the sizes of the two houses. This is the case in Australia, where the House of Representatives must be twice the size of the Senate (s 24), and thus any measure to increase the size of the former has consequences for the latter.

Constitutions play diverse roles in the process of legislative expansion, some being permissive and others prescriptive. Some constitutions, such as Indonesia’s, do not indicate the number of members in the lower chamber but leave the matter entirely to the legislature (currently 560 members) (arts 2, 19, 22C). Other constitutions, such as Nigeria’s, specify the exact size of the lower chamber (360 members), with no express mechanism for growth other than through the regular processes of constitutional amendment (s 49). Other constitutions stipulate an initial size and leave it to the legislature to alter the number of representatives as it thinks fit. In 1787, the US Constitution specified 66 members of the House of Representatives (art I s 2), but federal law gradually expanded the lower house to its present 435 members, the last expansion occurring in 1911. The only constitutional constraints are that each state have at least one member and that there be no more than one member for every 30,000 people – long since made irrelevant by the country’s rapid population growth. Still other constitutions include a constitutional formula for determining the total number of members, with or without a cap. The Brazilian Constitution (art 45) stipulates that the total number of Deputies in the lower chamber shall be ‘in proportion to the population’ but determined by law, which since 1993 has capped that number at 513. In India, the lower chamber is capped at 530 members from the states and 20 from the territories (art 81).

Electoral representation

Demographic change also affects the spatial dimensions of electoral representation. Although imperfectly realised, the guiding democratic principle is ‘one vote, one value’. The mechanism for achieving this, in systems with single-member electorates, is that electoral boundaries should be drawn to ensure that, as nearly as practicable, each electorate contains the same number of voters.

This conception of political equality is generally absent from representation in upper chambers. In federations, upper chambers usually follow a federal principle by which each state elects an equal number of members regardless of the state’s population – in the United States it is 2; in Brazil and Nigeria, 3; in Australia, 12; while India is atypical in that its Council of States comprises unequal numbers of representatives from each state, ranging from 1–31.[6] Non-federal states may contain similar features: in Indonesia, up to one-quarter of the People’s Consultative Assembly (‘MPR’) is drawn from a regional council (‘DPD’) whose members are drawn in equal numbers from the 30 provinces (arts 2, 22C).

In lower chambers, population proportionality is the dominant organising principle. In Nigeria, for example, the boundaries of each federal constituency shall be such that ‘the number of inhabitants thereof is as nearly equal to the population quota as is reasonably practicable’ (s 72). In some federations, the organising principle operates twice over – seats are allocated to the states in proportion to each state’s population and, within each state, single-member electorates are required to contain equal numbers of voters.[7]

The application of population proportionality to lower chambers is not perfect, and the imperfections come from many sources. First, inequalities arise because of indivisibilities that result from allocating people to a small and finite number of electorates. Second, voter equality achieved at one point in time can deliquesce in the face of dynamic populations, necessitating periodic adjustments. Third, floors and ceilings to state representation in the national legislature can introduce anomalies – the former resulting in over-representation of the least-populous states and the latter resulting in under-representation of the most-populous. In the United States, each state is entitled to a minimum of one seat in the House of Representatives; in Australia it is 5; in Brazil there is a minimum of 8 and a maximum of 70; and in India the proportionality rule does not apply to small states (those under 6 million people).[8] Fourth, the way in which population is defined can have a distorting effect. In 1976 the Indian Constitution was amended to fix the population of the states as at the 1971 census for the purpose of allocating seats in the national parliament to the states (art 81). The data will not be revised until at least 2026, by which time the population figures will be 55 years out of date. The reason for the freeze was ostensibly to prevent the rapidly growing northern states from being rewarded by extra seats, for poor performance in lowering birth rates, in contradiction of the government’s policy of reducing population growth.[9]

State formation in federations

For those countries with a federal constitution, population change may also drive the formation of states within the union. Historically, this is can be seen in the way in which the 13 original states of the United States expanded to 50, growing westward to fill the entire continental land mass. While the US Constitution provides that new states may be admitted into the Union, it left Congress to fashion the conditions of entry. The Northwest Ordinance (1787) addressed this issue by stipulating that a territory could petition for admission as a new state only once its population reached 60,000. This established a precedent by which the United States expanded through the addition of new states.

All federal constitutions provide for the admission of new states, but where existing states already occupy all available land territory, new states can only be added by new territorial acquisitions or, more commonly, by carving out new states from old. The procedures for doing so vary, requiring federal legislation, consent of the affected state legislatures, a referendum of the affected population, or a combination of these.[10] Of the case studies, the Nigerian Constitution is the most onerous, requiring: (a) support from two-thirds of the representatives of the National Assembly, the state legislature, and the local government council from the affected area; (b) a popular referendum; (c) a simple majority of all states of the federation; and (d) a two-thirds majority of each chamber of the National Assembly. With such a high threshold, Nigeria is unlikely to see any short-term alteration to the boundaries of its existing 36 states. By contrast, India’s more liberal provisions have facilitated the merging and splitting of states on many occasions since 1950. This has been a response to pressures of changing population size and composition, including the desire of less-prosperous regions for greater political influence. In 2011, territory-splitting was also attempted unsuccessfully in Brazil’s Para state.

IV POPULATION AND THE SOCIO-ECONOMIC DOMAIN

The socio-economic domain covers an expansive set of constitutional provisions that have both direct and indirect bearing on the demographic processes of fertility, mortality, and migration.

Fertility

Prescriptions, or lack thereof, about marriage, divorce, family planning, sterilisation, and abortion are key examples of the ways in which constitutions can affect reproductive decision-making by individuals and hence the population’s fertility. Marital status is one of the most important determinants of fertility, even in countries with liberal attitudes to ex-nuptial births. The regulation of marriage formation and dissolution therefore has repercussions at a population level. Globally, the marriageable age for females ranges from around 13 years to 20 years. While none of the constitutions under review prescribes a marriageable age, several expressly authorise the legislature to make such laws.[11] In federations, this power may lie with federal or state legislatures, and may be exclusive or concurrent. In Nigeria, the National Assembly’s exclusive power does not extend to marriages under Islamic or customary law, which generally permit marriage at younger ages. In Indonesia, the tension between Islamic law and the secular principles that underpin the constitution has been accommodated in the context of family law through the grant of wide-ranging regional autonomy.

Access to family planning has been a major concern of the international community for many years. At a United Nations conference held in Cairo in 1994, countries affirmed ‘the basic right of all couples and individuals to decide freely and responsibly the number, spacing and timing of their children and ... to make decisions concerning reproduction free of discrimination, coercion and violence’.[12] While this commitment was directed to promoting individual freedom of choice in reproductive matters, the state also has an interest in fertility because of its long-term demographic consequences. Individual interests and state interests do not always coincide, and they may be pro- or anti-natalist. This ambivalence can be seen in the diverse constitutional provisions.

In Indonesia, the human rights chapter introduced in 2000 includes the right of every person ‘to establish a family and to procreate based upon lawful marriage’ (art 28B). In India, a constitutional amendment made in 1976 during the emergency period introduced a new head of concurrent legislative power with respect to ‘population control and family planning’ – thus enabling greater state regulation (art 246, sch 7, List III-20A). Brazil’s 1988 constitution sets out rights and responsibilities, stating that ‘couples are free to decide on family planning’ and that the state must provide ‘educational and scientific resources for the exercise of this right, prohibiting any coercion on the part of official or private institutions’ (art 226(7)). All these provisions have been adopted within the past generation, but concern for family planning is also evident in judicial interpretation of older constitutions, such as the notion of reproductive freedom enjoyed under the US Constitution as a hallmark of personal liberty.

Two aspects of fertility control deserve special mention – sterilisation and abortion. Both procedures have been integral to population control in China under the ‘one-child policy’, which was introduced in 1978 and given a formal legislative (but not constitutional) basis in 2001. Among the case studies, voluntary sterilisation is a common means of family planning in countries such as Brazil. Coerced mass sterilisation as a means of population control has generated great controversy, and India’s experience of it in the 1960s and 1970s ‘has become emblematic of everything that can go wrong in a program premised on “population control” rather than on reproductive rights and health’.[13] Millions of male sterilisations were performed during this period, often coerced by ‘negative incentives’ such as withdrawal of healthcare, education, housing, and employment from families with more than three children. While legislative proposals for compulsory sterilisation were never adopted, the declaration of a state of emergency in 1975 – prompted in part by the ‘population crisis’ – had the effect of suspending constitutional rights that may otherwise have prevented such coercive action (art 359).

The control of fertility through induced abortion is also a controversial issue, as evidenced by the ‘one-child policy’ in China, where 6.3 to 14.4 million abortions have been reported annually since the late 1970s. This has been elevated to a constitutional level in some countries, although others have resisted the pressure to do so. For example, in deliberations leading to the adoption of Brazil’s constitution, church groups sought to include the ‘right to life from conception’ but this was successfully resisted by women’s groups.[14] Where abortion is constitutionalised, approaches vary widely. At one end of the spectrum lie countries such as Ireland and Kenya, whose constitutions expressly ban abortion.[15] In Ireland, there was no constitutional regulation of abortion until 1983, when an amendment acknowledged ‘the right to life of the unborn’. A subsequent referendum to liberalise abortion laws was narrowly defeated in 2002. The Kenyan Constitution also states that abortion is not permitted but, unlike the Irish provision, makes exceptions where there is a need for emergency treatment, the life or health of the mother is in danger, or abortion is permitted by another law. The last qualification has the potential to neutralise legislatively the pro-natalist stance of the Kenya’s constitutional ban on abortion.

Contrasting with the restrictive approaches in Ireland and Kenya is the well-known decision of the United States Supreme Court in Roe v Wade.[16] There the Court held that a constitutional right to privacy in reproductive decision-making arose from the concept of personal liberty protected by the Fourteenth Amendment. This right limited a state’s capacity to criminalise abortion, depending on the gestational stage of the foetus. In the wake of the decision, the rate of legal abortions in the United States nearly doubled, although the approach in recent jurisprudence has been less liberal.

Mortality

The role of constitutions in influencing mortality is perhaps the least obvious of the three components of population change. In individual cases, constitutions may have something to say about end-of-life decisions such as euthanasia, the liberty to refuse unwanted medical treatment, or the availability of the death penalty in criminal cases. However, these are unusual situations and the first two, in particular, are of interest primarily to developed countries with advanced medical systems. More significant at a population level is the capacity of governments to promote public health, provide appropriate health services, and support the wellbeing of individuals as they age. It is notable that the most significant improvements in life expectancy in modern times have come from reductions in child and maternal mortality, which form part of the United Nations’ Millennium Development Goals. Improvements directed to that end may come through constitutional articulation of rights and duties, empowerment of legislatures to make laws on those subjects, and authority to spend on health programmes and services.

Some constitutions impose general duties on the state to take health-related action, such as the injunction in the Netherlands Constitution (1983) that ‘the authorities shall take steps to promote the health of the population’ (art 22). Constitutions that include social and economic rights as part of their fabric may include more specific rights. The Brazilian Constitution includes health and nutrition as social rights, while urban and rural workers have the additional right to a retirement pension, which is an important factor in promoting access to aged healthcare (arts 6, 7(xxiv), 196). The Constitution describes health as the right of all and the duty of the national government, which is to be guaranteed by policies aimed at ‘reducing the risk of illness and other maladies’ through universal and equal access to services. Similarly, the Indian Constitution includes the improvement of public health as a primary duty of the state, but only as a non-enforceable ‘directive principle’ (art 47). Constitutional courts have recognised that realisation of the right to health or medical treatment is often tempered by resource constraints and that governments may ration available resources through policies that attend to the larger needs of society rather than the specific needs of individuals.[17] In some countries, such as Australia, by far the most significant role of government in relation to mortality stems not from legislative powers over health but from financial control exercised by making tied grants to constituent states and appropriating funds for direct government programmes (ss 81, 96).

Migration

Many constitutions guarantee the right of individuals to move freely within the country.[18] This freedom of movement enables the spatial redistribution of the population, such as the rural-urban drift noted above, although some constitutions expressly seek to slow the rate of urbanisation by reducing disparities in the standard of living between rural and urban areas.[19] By contrast, international movement of persons touches a key attribute of sovereignty and is tightly regulated by granting the national legislature exclusive, or sometimes concurrent, power to make laws with respect to immigration and emigration.[20] Many constitutions also make indirect provision for international migration by defining membership of their societies through the concept of nationality or citizenship. Because nationals have a right to enter their own country under international law (which some constitutions also reflect),[21] broader or narrower conceptions of nationality can impact on the size and composition of a population. Some constitutions (e.g., United States) follow the principle of jus soli, providing that nationality at birth is acquired merely by being born in the territory of the state; others (e.g., Nigeria) follow the principle of jus sanguinis, providing that nationality at birth is acquired by any person who is descended from nationals; while still others (e.g., Brazil, India) recognise both bases.[22]

V POPULATION AND THE ETHNO-CULTURAL DOMAIN

In the modern world no country has a homogeneous population – even Iceland (the most homogeneous) has experienced increasing diversity in recent times due to international migration. This diversity is often seen across language, culture, religion, ethnicity, and race. To what extent do constitutions recognise these compositional attributes of a population? At one end of the continuum lie countries like Indonesia, whose 240 million people span an archipelago of substantial ethnic and linguistic diversity but whose original 1945 constitution established a unitary republic that gave no formal recognition to this diversity. This constitutional silence was seen as a means of establishing a strongly centralised and integrated state, in the face of pluralism, after a long period of Dutch colonial rule.[23] Only more recently have secessionist conflicts in the provinces of Aceh and Irian Jaya led to constitutional amendments that recognise, in somewhat abstract terms, the ‘diversity of each region’ and the ‘special and distinct’ features of regional units (arts 18A, 18B). However, the Indonesian Constitution does not itself accommodate diversity, relegating it to the national legislature, where special autonomy laws have since been passed for these fractious provinces.

The Indian Constitution provides a stark contrast to Indonesia in addressing the issue of diverse sub-populations – it protects diversity through a framework of rights, including positive measures to protect the least advantaged. The constitution provides that citizens have a right to conserve their ‘distinct language, script or culture’, and that minorities have the right to ‘establish and administer educational institutions of their choice’ (arts 29–30). In an environment where language differences have been a frequent social irritant, states within the Union are authorised to adopt official languages in addition to Hindi, and the President may direct a state to recognise a language if so desired by a ‘substantial proportion’ of the state’s population (arts 345–347). Indeed, the re-drawing of state boundaries in India, noted above, has been driven to a large degree by the desire to form more linguistically homogeneous territorial units, especially in the south.[24]

More remarkable are the constitutional provisions for affirmative action (positive discrimination) in relation to certain castes, tribes and ‘other backward classes’.[25] The constitution establishes a process of one-off executive notification for defining the beneficiaries of the affirmative action provisions, which may be amended only by legislation (arts 341–342). The affirmative measures include the reservation of seats in the lower chambers of the Union and the states in proportion to the population of the affected groups in each state; ‘consideration ... in the making of appointments to services and posts’ in the public sector; and the establishment of national commissions to monitor the constitutional safeguards (Part XVI). Originally set to expire in 20 years, the provisions have been extended time and again.[26]

In Nigeria, the object of achieving national unity in a country characterised by more than 250 ethnic groups, 500 indigenous languages and diverse religions (50 per cent Muslim, 40 per cent Christian, 10 per cent indigenous) has been approached openly. The constitutional response has been partly structural (the 1999 constitution is federal in character) and partly proscriptive – Nigeria’s multi-religious make-up is accommodated by prohibiting the adoption of a state religion (s 10). The constitution also contains directive principles that require, at the federal level, that ‘there shall be no predominance of persons ... from a few ethnic or other sectional groups’; and, at the state and local levels, that the conduct of government affairs shall ‘recognise the diversity of the people within its area of authority’ (s 14). The Federal Character Commission is given power under the constitution to give effect to s 14 by working out an equitable formula for the distribution of all cadres of posts in the public service, armed forces, police force and government-owned companies. The Commission also has power to promote, monitor, and enforce compliance with the principles of proportional sharing of all bureaucratic, economic, media, and political posts at all levels of government (sch 3, s 8). This goes well beyond minority rights; it provides an institutional framework for programmatic action. The constitution demands not merely that ‘regard’ be had to the diversity of each region (as in Indonesia) or that the claims of disadvantaged groups to jobs ‘be taken into consideration’ (as in India), but that the distribution of public goods accords with the robust principle of proportionality, backed up by measures for legal enforcement.

VI POPULATION AND THE SCIENTIFIC DOMAIN

How do constitutions promote the availability of relevant, timely, and accurate scientific knowledge about populations, so as to inform the political, socio-economic, and ethno-cultural domains identified above? Population data come from many sources. The best known is the population census, which is a complete enumeration of a population at a specific point in time. Other important data sources are registers of vital events (births, deaths, marriages, divorces); administrative collections maintained by governments for other purposes (immigration control, healthcare claims, school enrolments); population registers, which keep complete and continuous records of all vital events experienced by residents in the small number of countries that keep such registers; and sample surveys. Constitutions may promote the collection, analysis and dissemination of population data from any of these sources through provisions they make about processes, institutions or substantive counting rules.

Processes for collecting population data

The process for collecting population statistics most frequently identified in constitutions is the population census. The US Constitution provided an early model in mandating that a census of the American people be conducted within three years of the first meeting of Congress, and every ten years thereafter (art I, s 2). The purpose of that census falls squarely within the political domain, namely, to adjust the number of congressional representatives elected from each state and to augment the total number of representatives as the population grows.[27] Many other countries have shied away from a constitutional mandate for a periodic census but instead authorise the legislature to make such laws on that topic as it thinks fit. Thus, the federal legislature has exclusive power over ‘census’ in India and over ‘national systems of statistics’ in Brazil, while in Australia it has concurrent power over ‘census and statistics’.[28] The international norm is to hold censuses every ten years, but countries such as Australia conduct them every five years. In some countries, constitutional rights to privacy limit the nature of information that can be collected during a census or disclosed subsequently. The Indian Constitution also recognises methods of data collection beyond the census: the power to make laws with respect to ‘vital statistics including registration of births and deaths’ is shared concurrently by federal and state legislatures, whereas the Nigerian Constitution makes vital registration an exclusive federal power.[29]

Institutions for analysing population data

Most countries now have well-established institutions for conducting periodic censuses and reporting on population issues. The work of these national statistical institutes often informs issues of electoral representation but also extends well beyond this domain in informing social and economic policy. Nigeria is unusual, however, in giving such an institution constitutional status.[30] The Nigerian Constitution establishes the National Population Commission as an independent authority with wide-ranging functions. These include enumeration of the population through censuses and surveys, maintaining the machinery for registering births and deaths, advising the President on population matters, and publishing population data for the purpose of economic and development planning. The Commission’s census reports are given special prominence by reason of the fact that they must be delivered to the President and, if accepted, tabled in the national legislature. The delicate accommodation of diverse ethnic and religious interests probably accounts for the profile given to the work of this constitutional body.

Rules for using population data

Constitutions may also set out substantive rules about the use of population data. A simple example is the requirement in Australia and Nigeria that electoral representation be determined using the ‘latest’ statistics or census data, which contrasts with the requirement in India that out-dated statistics be used, as discussed above.[31] Less benign is the provision in the US Constitution (art 1, s 2) that excluded some Native Americans and two-fifths of slaves from the population count for the purpose of apportioning congressional representatives to the states; or the provision in the Australian Constitution (s 127) that completely excluded indigenous Australians from being counted in estimates of the Australian population. Consistent with this, every Australian census held from federation in 1901 until the provision was repealed by referendum in 1967 included a question on race for the purpose of excluding ‘Aboriginal natives’ from official population counts.

The illustrations reflect the experience of many countries that the way in which people are counted can be highly politically charged, especially when race, religion or privacy are involved. This can make the census difficult to execute, since successful enumeration depends on the trust of those enumerated. In the United States, for example, there has been ongoing legal controversy about whether the ‘actual enumeration’ mandated by the Constitution permits the Census Bureau to adjust raw population data for net undercount (i.e., the difference between the number of people who were not counted but should have been, and the number who were counted but should not have been), which disproportionately affects African Americans and Hispanics.[32]

VII CONCLUSION

The relationship between constitutions and populations deserves more attention than it has received. Populations are far from immutable, but the forces that drive change reflect deep social processes that evolve unhurriedly, but nonetheless insistently, over time. Demographic change and constitutional change operate in a similar multi-generational timeframe, which ought to encourage a reflexive relationship between them.

This Chapter has examined the ways in which constitutions reflect and respond to population change. The relationship is a complex one, reflecting contrasts in population histories, economic development, constitutional styles, and judicial attitudes. Modernising social processes have resulted in profound transformations in all populations over the past century. If constitutions are to provide sound architectures for the governance of people far into the future, they need to have population dynamics firmly in mind in their design and subsequent evolution.

FURTHER READING

Larry Barnett and Emily Reed, Law, Society, and Population: Issues in a New Field (Cap and Gown Press, 1985).

Sujit Choudhry (ed), Constitutional Design for Divided Societies: Integration or Accommodation? (Oxford University Press, 2008).

John Juriansz and Brian Opeskin, ‘Electoral Redistribution in Australia: Accommodating 150 Years of Demographic Change’ (2012) 58 Australian Journal of Politics and History __.

Ronald Lee, ‘The Demographic Transition: Three Centuries of Fundamental Change’ (2003) 17(4) Journal of Economic Perspectives 167–190.

Brian Opeskin, ‘Constitutions and Populations: How Well has the Australian Constitution Accommodated a Century of Demographic Change?’ (2010) 21 Public Law Review 109–140.

Peter Skerry, Counting on the Census? Race, Group Identity, and the Evasion of Politics (Brookings Institution Press, 2000).

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, World Population Policies 2009 (United Nations, 2010).

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, World Population Prospects: The 2010 Revision (United Nations, 2011).

[∗] The authors wish to thank

Bronwyn Lo for research assistance, and Denise Meyerson, Nick Parr and the

editors for insightful comments

on a

draft.

[1] Paul Erlich, The

Population Bomb (Ballantine Books,

1968).

[2] John Weeks,

Population: An Introduction to Concepts and Issues (9th ed, 2005)

34.

[3] Weeks, above n 2, 46.

[4] Abdel Omran, ‘The

Epidemiological Transition: A Theory of the Epidemiology of Population

Change’ (1971) 49 Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly

509.

[5] Robert Dahl and Edward

Tufte, Size and Democracy (Stanford University Press, 1973)

80.

[6] Australia s 7; Brazil

art 46; India art 80, sch 4; Nigeria s 48; United States art

I s 3.

[7] Australia s 24; United

States art 1, s 2; India art 81. The second requirement (equally

sized electorates within a state) derives from legislation in Australia and case

law

in the United States: see Wesberry v Sanders [1964] USSC 31; 376 US 1 (1964) and its

progeny. See also Brazil

art 45.

[8] Australia

s 24; United States art I s 2; Brazil art 45; India

art 81.

[9] Carol Haub and O Sharma,

‘India’s Population Reality: Reconciling Change and Tradition’

(2006) 61(3) Population Bulletin 1,

14.

[10] Australia

ss 123–124; Brazil art 18; India arts 2–3; Nigeria

s 8; United States art IV s

3.

[11] Australia s 51(xxi);

India art 246, sch 7, List III-5; Nigeria sch 2, Part I-61.

[12] International Conference on Population and Development, Programme of Action, s 7.3.

[13] Matthew Connelly, ‘Population Control in India: Prologue to the Emergency Period’ (2006) 32(4) Population and Development Review 629, 629.

[14] Alessandra Guedes, ‘Abortion in Brazil: Legislation, Reality and Options’ (2000) 8(16) Reproductive Health Matters 66, 71.

[15] Constitution of

Ireland (1937) art 40.3.3; Constitution of Kenya (2010)

art 26(4).

[16] Roe v

Wade [1973] USSC 43; 410 US 113 (1973).

[17] Soobramoney v Minister of Health (KwaZulu-Natal) [1997] ZACC 17 (Constitutional Court of South Africa, 27 November 1997) [31], interpreting s 27(3).

[18] Australia s 92; Brazil

art 5(xv); Nigeria ss 15(3), 41. In the United States this derives

from judicial interpretation of the privileges and immunities clause: art IV

s 2. Contrast India, where the federal legislature has exclusive power to

regulate interstate migration (sch 7, List

I-81).

[19] Bangladesh

Constitution (1972), s 16.

[20] Australia s 51(xxvii); Brazil art 22(xv); India art 246, sch 7, List I-19; Nigeria s 4, sch 2, List I-30. In the United States this derives from judicial interpretation of the naturalisation power: art I s 8.

[21] International Covenant on

Civil and Political Rights, opened for signature 16 December 1966, 999 UNTS

171 (entered into force 23 March 1976) art 12(4). See e.g. Nigeria

s 41.

[22] Brazil

art 12(i); India art 5; Indonesia art 26; Nigeria s 25;

United States amend XIV s 1.

[23] Jacques Bertrand, ‘Indonesia’s Quasi-Federalist Approach: Accommodation amid Strong Integrationist Tendencies’ in Sujit Choudhry (ed), Constitutional Design for Divided Societies: Integration or Accommodation? (Oxford University Press, 2008) 205, 206.

[24] Emma Mawdsley, ‘Redrawing the Body Politic: Federalism, Regionalism and the Creation of New States in India’ (2002) 40(3) Commonwealth and Comparative Politics 34, 39–40.

[25] The practice of ‘untouchability’ was abolished by art 17 but discrimination against Dalit communities persists in practice.

[26] Thomas Sowell,

Affirmative Action Around the World: An Empircial Study (Yale University

Press, 2004) 23.

[27] Alexander

Hamilton, John Jay and James Madison, The Federalist No 58

(1788).

[28] India sch VII, List

I-69; Brazil art 22 (xviii); Australia

s 51(xi).

[29] India

sch VII, List III-30; Nigeria sch 2,

Part I-8.

[30] Nigeria

ss 153, 158, 213, sch 3

ss 23–24.

[31] Australia

ss 24, 105; India art 81; Nigeria s 75.

[32] Jacob Siegel, Applied Demography: Applications to Business, Government, Law, and Public Policy (Academic Press, 2002) 559–565.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/UTSLRS/2012/5.html