- Bills and Legislation

- Tariff ProposalsBills DigestsBrowse Bills Digests Ordering Printed BillsBudget and Financial LegislationLegislative Instruments

Building and Construction Industry (Improving Productivity) Bill 2013 [and] Building and Construction Industry (Consequential and Transitional Provisions) Bill 2013

Bills Digest no. 3, 2016–17

PDF version [1104KB]

WARNING: This Digest was prepared for debate. It reflects the legislation as introduced and does not canvass subsequent amendments. This Digest does not have any official legal status. Other sources should be consulted to determine the subsequent official status of the Bill.

Jaan Murphy

Law and Bills Digest Section

6

September 2016

This Bills Digest revises an earlier version dated 16 March 2016, to update the background to the Bills to reflect developments since their previous introductions in 2013 and 2016, including the conclusion of the Royal Commission into Trade Union Governance and Corruption.

Contents

Productivity Commission workplace relations framework inquiry

Harper review of competition law

Royal Commission into trade union governance and corruption

Industrial relations

Figure 1: Comparison of working days lost per 1,000 employees, construction and other industries

Workplace injuries and deaths

Table 1: Fatality rate, construction and all industries, Australia

Current committee consideration

Previous committee consideration

Senate Education and Employment Legislation Committee - 2016

Senate Education and Economics Legislation Committee - 2013

Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills - 2016

Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills – 2013/14

Consideration by the Senate Education and Economics References Committee in 2013/14

Policy position of non-government parties/independents

The Opposition

The Australian Greens

Other non-government parties and independents

Nick Xenophon Team

One Nation

Senators Day, Hinch, Lambie and Leyonhjelm

Senator Day

Senator Hinch

Senator Lambie

Senator Leyonhjelm

Ms McGowan, Mr Katter and Mr Wilkie

Position of major interest groups

Statement of Compatibility with Human Rights

Expanded coverage of the Bill

Geographical jurisdiction

Industry coverage

Ancillary sites

Impact of expanded coverage

Coercive powers

Current coercive powers

Proposed coercive powers

Ombudsman oversight of use of coercive powers

No privilege against self-incrimination

Additional protections

Retrospective operation of coercive investigatory powers

Criminal Offences

Civil penalty provisions

Industrial action

Protected industrial action

Constitutionally covered entities

Unlawful industrial action

Effect of new definitions

Unlawful Picketing

New unlawful picketing offence

First limb of unlawful picketing

Second limb of unlawful picketing

Prosecution after settlement of civil disputes

Reverse onus of proof

Project agreements

Chapter 3—The Building Code

Chapter 4—The Federal Safety Commissioner

The Transitional Bill

Date introduced: 31

August 2016

House: House of

Representatives

Portfolio: Employment

Commencement: Sections 1 and 2 of the main Bill commence on Royal Assent; all other

provisions commence on the day after Royal Assent. Sections 1 to 3 of the

Transitional Bill commence on Royal Assent; all other provisions are tied to

the commencement of the main Bill.

Links: The links to the Bills, their Explanatory Memoranda and second reading speeches can be found on the Bills’ home pages for the Building and Construction Industry (Improving Productivity) Bill 2013 and the Building and Construction Industry (Consequential and Transitional Provisions) Bill 2013 or through the Australian Parliament website.

When Bills have been passed and have received Royal Assent, they become Acts, which can be found at the Federal Register of Legislation website.

All hyperlinks in this Bills Digest are correct as at September 2016.

History of the Bills

The Bills were introduced into the 44th Parliament on 14 November 2013 and again on 2 February 2016.[1] The Bills had passed the House of Representatives, but were negatived at the second reading stage by the Senate on 17 August 2015 and again on 18 April 2016, hence forming the double dissolution trigger for the 2016 election.[2] The Bills lapsed on dissolution of Parliament.

Purpose of the Bills

The purpose of the Building and Construction Industry (Improving Productivity) Bill 2013 (the Bill) is to re‑institute a separate workplace relations framework for the building industry based largely on the Building and Construction Industry Improvement Act 2005 (the BCII Act). Among other things the Bill re-establishes the Australian Building and Construction Commission (ABCC), reintroduces provisions dealing with unlawful industrial action, coercion and the associated civil penalties specific to the building industry, and broadens the application of those provisions to include transporting and supplying of goods to be used in building work.

The purpose of the Building and Construction Industry (Consequential and Transitional Provisions) Bill 2013 (the Transitional Bill) is to wholly repeal the Fair Work (Building Industry) Act 2012 (FWBI Act),[3] to make necessary amendments to other Acts and to provide for the transition to the new arrangements.

Structure of the Bills

The Bill contains nine chapters.

- Chapter 1 contains preliminary material, including definitions which extend the scope of building and construction regulation

- Chapter 2 establishes the ABCC and the position of the ABCC Commissioner (the Commissioner)[4]

- Chapter 3 provides the Minister with the power to issue a Building Code

- Chapter 4 establishes the Federal Safety Commissioner

- Chapter 5 deals with unlawful action, including a new offence of unlawful picketing

- Chapter 6 deals with coercion, discrimination and unenforceable agreements

- Chapter 7 deals with powers of the Commissioner and other authorised officers to obtain information

- Chapter 8 deals with enforcement and

- Chapter 9 contains miscellaneous provisions, including provisions to do with handling of information, powers of the Commissioner, and courts.

The Transitional Bill contains two Schedules. Schedule 1 contains consequential provisions and repeals the FWBI Act. Schedule 2 contains transitional provisions.

Background

Readers are referred to pages 3 of 8 of Building and Construction Industry (Improving Productivity) Bill 2013 [and] Building and Construction Industry (Consequential and Transitional Provisions) Bill 2013, which provides background to the Cole Royal Commission, BCII Act, Wilcox Report, FWBI Act and Building Code.[5] As this is a revised version of that Digest, it only examines the recommendations made by the Royal Commission into Trade Union Governance and Corruption (the RCTUGC) and the Productivity Commission’s Report on Australia’s workplace relations framework (PC Report) that are relevant to the Bill, as well as providing updated statistics in relation to industrial disputation and workplace injuries and deaths since the Bill and Transitional Bill were last considered by the Parliament.

Productivity Commission workplace relations framework inquiry

The PC Report did not examine the need for a separate industry-specific regulator for the building and construction industry. However, the PC Report did note, in relation to secondary boycotts:[6]

... there are strong perceptions in sections of the business community, particularly in the construction sector, that there is inadequate enforcement of secondary boycott provisions.[7] (emphasis added)

The PC Report also noted that complaints received by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) ‘about secondary boycotts appear to centre largely on the construction industry’, but noted that even if such complaints are ‘indicative of a localised (even if serious) problem, the solution may not lie in a change across the full gamut of [workplace relations] WR or competition law’. Instead the Productivity Commission suggested that the following was a possible solution to the frequency of secondary boycott complaints in the building and construction industry:

It is possible that the powers of Fair Work Building and Construction (FWBC) to compel witnesses to provide evidence could be applied, by giving FWBC shared jurisdiction with the ACCC to investigate secondary boycotts within the construction industry. Having obtained evidence, the ACCC would then be able to take action. A similar approach was also recommended in submissions to the Royal Commission into Trade Union Governance and Corruption, and was supported by several inquiry participants.

An advantage of this approach is that parties or activities that are potentially in breach of the secondary boycott prohibitions can also be the subject of other concurrent investigations by FWBC into potential breaches of WR laws. It would leave intact the general responsibility of dealing with secondary boycotts via the appropriate mechanism, but address the core issue — obtaining evidence — via another mechanism.[8] (emphasis added, footnotes omitted)

Ultimately the PC Report recommended:

The Australian Government should grant Fair Work Building and Construction shared jurisdiction with the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission to investigate and enforce the secondary boycott prohibitions of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) in the building and construction industry.[9]

The Bill, as currently drafted, does not propose amendments reflecting the above recommendation. Whether the Government will seek to move amendments to give effect to the above recommendation during the passage of the Bill through the Parliament remains to be seen.

Harper review of competition law

Whilst the Competition Policy Review Report (the Harper Review) did not examine the conduct of the building and construction industry in detail, it did note that:

Some industry organisations, especially in building, construction and mining, believe that public enforcement of the secondary boycott provisions is inadequate, a point emphasised in the Interim Report of the Royal Commission into Trade Union Governance and Corruption. Timely and effective public enforcement serves as a deterrent to boycott activity and needs to exist both in regulatory culture and capability. The Panel believes that the ACCC should pursue secondary boycott cases with increased vigour, comparable to that which it applies in pursuing other contraventions of the competition law.[10]

The Harper Review noted that some submissions had argued that due to the degree of concerns in the construction industry, and the perceived complexity of the issues surrounding enforcing existing secondary boycott laws, a shared jurisdiction in relation to secondary boycotts between the ACCC and any Australian Building and Construction Commission-type body (should one be re-established) was warranted.[11]

The Harper Review recommended that the maximum penalty level for secondary boycotts should be increased from its current level of $750,000 to the same as that applying to other breaches of the competition law ($10 million) and that ‘the ACCC should pursue secondary boycott cases with increased vigour, comparable to that which it applies in pursuing other contraventions of the competition law’.[12]

Whilst the Bill does not directly deal with the issues of secondary boycotts, it does contain a provision that could arguably be used to combat some type of secondary boycotts. This issue is examined below under the heading ‘Expanded coverage of the Bill’.

Royal Commission into trade union governance and corruption

In February 2014, the then Prime Minister, Tony Abbott, announced that he would be:

... recommending to the Governor-General, Her Excellency Ms Quentin Bryce AC CVO, the establishment of a Royal Commission to inquire into alleged financial irregularities associated with the affairs of trade unions.[13]

In March 2014, the Governor-General issued Letters Patent to establish the RCTUGC with the terms of reference outlined by the then Prime Minister in February 2014, and appointed Dyson Heydon as Royal Commissioner.[14] Relevantly to the Bill, the terms of reference included examining the:

... activities relating to the establishment and operation of... the Australian Workers Union... the Construction, Forestry Mining and Energy Union... the Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing and Allied Services Union of Australia...[15]

As a result of that (and other) aspects of the terms of reference, the RCTUGC was authorised to closely examine the conduct of key building and construction industry participants. As a result of those inquiries, the RCTUGC made a number of recommendations in relation to the regulation of the building and construction industry.[16] The table in Appendix C outlines the relevant recommendations made by the RCTUGC and whether the Bill, as drafted, would fulfil those recommendations. They are also examined below in the ‘Key issues and provisions’ section of this digest.

Industrial relations

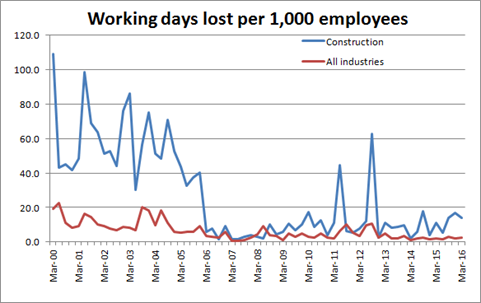

Days lost to industrial disputes per 1,000 workers in the construction industry are shown in Figure 1. Interpreting the picture is not simple.

First, there was no dramatic decline from the time when the Building Industry Task Force (which had many of the functions of the ABCC) began operations in 2002. Second, there have been many more days lost to industrial disputes in the last few years, since the former Labor Government began the changes to regulation. However, the peaks in the data appear to correspond to serious disputes in Victoria, which were a result of a tightening, not a loosening, of regulation.

Third, the low levels of industrial disputation observed between 2006 and 2009 broadly align with the operation of the Workchoices industrial relations regime, which aimed to significantly restrict trade union activity, including the ability to undertake protected industrial action.[17] As such, the drop in industrial disputation within the construction industry observed during this period must be considered within the broader context of the wider industrial relations regime in effect during that time.

Finally, a significant reduction in days lost to industrial disputes per 1,000 workers in the construction industry is evident from late 2012 onwards. Indeed, the rate of disputation appears to now be approaching a similar rate to that recorded in 2006–2008 (broadly reflecting a period when the ABCC and the Workchoices were both operating). Moreover, whilst higher overall, the overall trends in the figures for industrial disputes in the construction industry are nonetheless roughly similar to those for the economy as a whole, at least until 2014.

Figure 1: Comparison of working days lost per 1,000 employees, construction and other industries

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), Industrial

disputes, Australia, various issues, cat. no. 6321.0.55.001.[18]

Workplace injuries and deaths

It has been claimed that the ABCC resulted in an increase in the number of injuries and deaths in the construction industry. For example, David Noonan of the CFMEU said:

The biggest issue facing construction workers is poor workplace safety. The ABCC of course does not regulate safety, but those state and federal bodies that do are underresourced compared to the ABCC. The last time we saw the ABCC in place, safety suffered—it went downhill and fatalities increased in the construction industry.[19]

Professor David Peetz wrote:

There were 36 fatalities in the construction industry in 2007–08, twice as many as in 2004–05, immediately before the ABCC commenced operations in late 2005. Under the ABCC, construction became the industry with the highest number of deaths. As observance with occupational safety tends to be lower where unions are weaker, this trend is not surprising.[20]

There does seem to have been an increase in the rate of deaths in the years of the ABCC, and a reduction in recent years:

Table 1: Fatality rate, construction and all industries, Australia

| Fatality rate (deaths per 100,000 workers) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Industry of employer | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 |

| Construction | 5.8 | 4.4 | 3.6 | 4.8 | 4.8 | 3.9 | 3.7 | 4.1 | 4.0 | 3.1 | 2.2 | 3.0 |

| All industries | 2.8 | 3.0 | 2.6 | 2.8 | 3.0 | 2.6 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.7 | 1.6 |

Source: Safe Work Australia, Work related traumatic injury fatalities, Australia, 2014, Figure 5.[21]

Current committee consideration

On 31 August 2016, the Senate Standing Committee for Selection of Bills referred the Bills to the Senate Education and Employment Legislation Committee for inquiry and report by 14 October 2016.[22] Details of the inquiry will be available at the Committee's webpage.[23]

Previous committee consideration

As identical versions of the Bills were introduced into the Parliament in 2013 and February 2016, previous consideration by various Committees is noted below.

Senate Education and Employment Legislation Committee - 2016

The Bills were referred to the Senate Education and Employment Legislation Committee (the Legislation Committee) for inquiry. The Legislation Committee reported on 11 March 2016. Details of the inquiry are at the inquiry web page.[24] The Legislation Committee’s report recommended that the Bills be passed.[25] The report noted:

The committee notes that while it received submissions criticising the Bills, no fresh arguments have been made against the re-establishment of the ABCC since the committee previously considered this proposed legislation in 2013. The main argument put forward to oppose the Bills remains that there is no need for special laws for the building and construction industry and that such laws would unfairly single out the industry for treatment different to other industries. The committee notes that arguments made against the Bills suggest an aversion amongst unions towards special attention being paid to the building and construction industry, despite widespread and serious unlawful conduct identified during a range of inquiries. The committee is disappointed that, in light of indisputable evidence, certain union officials in the building and construction industry continue to flout the law and deny that an industry-specific focus is required to combat this serious and persistent unlawful behaviour.[26]

In a dissenting report, Labor Senators recommended that the Bills not be passed:

Labor Senators do not see merit in the Building and Construction Industry (Improving Productivity) Bill 2013 [No.2] and the Building and Construction Industry (Consequential and Transitional Provisions) Bill 2013 [No.2] and, as with the previous iteration of the Bills, oppose both in their entirety without amendment.[27]

In addition, the Labor Senators also stated that the Bills would not improve productivity and would lead to an increased rate of workplace injuries and deaths in the construction industry.[28]

In a further dissenting report, Australian Greens Senators also recommended that the Bills not be passed and stated that:

The ABCC failed to act as independent regulator committed to the best interests of the industry, the conditions of the workers and the needs of legitimate employers... The Australian Greens will always stand up for people's rights at work. We urge Senators not to support this Bill.[29]

The Australian Greens Senators also recommended that ‘the government establish a broad-based federal anti‑corruption body’ and that ‘the provisions in relation to the Building Code be removed from the Bill’.[30]

Senate Education and Economics Legislation Committee - 2013

The 2013 Bills were referred to the Legislation Committee for inquiry and report by 2 December 2013. Details of the inquiry are at the inquiry web page.[31] The Legislation Committee’s report recommended that the Bills be passed.[32] In its concluding remarks it stated:

The building and construction industry is an important sector of the Australian economy. Throughout this inquiry the committee has been presented with evidence of increased illegality and disregard for the rule of law in the building and construction industry. It is of the utmost importance that this sector is able to flourish and is not hampered by illegality and a culture of intimidation as evidenced in the inquiry. The committee is also persuaded by evidence that productivity in the sector has declined since the ABCC was abolished by the former government. An independent, empowered, and properly resourced regulator is necessary.[33]

In a dissenting report, Labor Senators strongly recommended that the Bills not be passed:

The urgency to re-enact the Australian Building and Construction Committee [sic] is not based on genuine requirement for urgent workplace reform, but on political motivation following the change of government. Labor senators feel strongly that the Bills are being rushed unnecessarily through the Parliament.[34]

In a further dissenting report, Australian Greens Senators also recommended that the Bills not be passed:

The ABCC was biased in its work as it was driven by an ideological attack on construction workers and unions. Further, in recent years Australia’s construction industry laws have been condemned by the International Labour Organisation six times. For these reasons the Australian Greens reject the Bills in their entirety.[35]

Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills - 2016

The Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills considered the Bills in Alert Digest No. 2 of 2016.[36] The Committee restated its comments about the Bills made in 2013 (discussed below).

Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills – 2013/14

The Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills (Scrutiny Committee) raised a large number of concerns about the 2013 Bills.[37] The Minister responded to those concerns in January 2014.[38]

The Scrutiny Committee noted that the effect of item 2 of Schedule 1 of the Transitional Bill is that decisions made under the Building and Construction Industry (Improving Productivity) Act 2013 will be excluded from the application of the Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 (ADJR Act). While this is similar to provisions in the FWBI Act and the Fair Work Act 2009 (FWA), the Scrutiny Committee notes that the Administrative Review Council concluded that the current exemption of ABCC decisions from the application of the ADJR Act should be removed.[39] After reviewing the Minister’s response, the Scrutiny Committee noted that it remained ‘concerned about the exclusion of review under the ADJR Act’ but left the ‘question of whether the proposed approach is appropriate to the Senate as a whole’.[40]

The Scrutiny Committee expressed concern about the number of instances of the delegation of legislative power in the Bill.[41]

Clause 120 of the Bill allows the Minister to make rules by legislative instrument. Clause 5 of the Bill includes a definition of ‘authorised applicant’, which is a person who is entitled to seek an order relating to a contravention of a civil remedy provision. The definition allows the rules to determine that someone is an authorised applicant, and the Scrutiny Committee commented that it was not clear why this should be left to regulation—or indeed why persons other than the Commissioner or persons affected would need to be authorised. Similarly, the Commissioner has a broad power of delegation to ‘a person...prescribed by the rules’ (paragraph 19(1)(d)) and the Federal Safety Commissioner has a similar power under paragraph 40(1)(c). After reviewing the Minister’s response, the Scrutiny Committee requested that the key information provided by the Minister be included in the Explanatory Memorandum, but noted that it left the ‘question of whether the proposed approach is appropriate to the Senate as a whole’.[42]

The Scrutiny Committee questioned the provision in subclause 6(4) that allows the rules to prescribe what is ‘building work’, given that this could extend the coverage of the Bill. Subclause 11(2) would similarly allow the rules to extend the application of the Act in relation to the exclusive economic zone and waters above the continental shelf. After reviewing the Minister’s response, the Scrutiny Committee requested that the key information provided by the Minister be included in the Explanatory Memorandum, but noted that it left the ‘question of whether the proposed approach is appropriate to the Senate as a whole’.[43]

Clause 43 provides that a Work Health and Safety Accreditation Scheme may be established under the rules. The Scrutiny Committee stated that too little detail was set out in the Bill, and the Explanatory Memorandum did not explain why it is appropriate for the Scheme to be established in this way.[44] After reviewing the Minister’s response, the Scrutiny Committee requested that the key information provided by the Minister be included in the Explanatory Memorandum, but noted that it left the ‘question of whether the proposed approach is appropriate to the Senate as a whole’.[45]

Paragraph 70(1)(c) provides that the purposes for which an inspector may exercise compliance powers include ‘purposes of a provision of the rules that confer functions or powers on inspectors’. The Scrutiny Committee considered that the scope of application of the coercive powers should be specified within the primary legislation.[46] After reviewing the Minister’s response, the Scrutiny Committee requested that the key information provided by the Minister be included in the Explanatory Memorandum, but noted that it left the ‘question of whether the proposed approach is appropriate to the Senate as a whole’.[47]

The Scrutiny Committee raised a number of concerns about trespass on personal rights and liberties. First, there are several instances of the imposition of a reverse onus of proof in the Bill. For example, action taken by an employee based on health and safety concerns may not be regarded as ‘industrial action’, but the burden of proof is on the employee to prove that the action was based on the employee’s reasonable concern about an imminent risk to his or her health and safety and that he or she did not unreasonably fail to perform other available work (paragraph 7(2)(c) and subclause 7(4)). The Scrutiny Committee noted that equivalent provision in the FWA which excludes certain action taken for health and safety reasons from the definition of industrial action (paragraph 19(2)(c) of the FWA) does not reverse the onus of proof.[48] In civil proceedings under clause 57 to do with unlawful picketing, the person has to establish that their actions were not unlawful.[49] Similarly, if a person wishes to rely on an exception or excuse in civil proceedings, under clause 93 they bear the burden of proof.[50] In relation to paragraph 7(2)(c), subclause 7(4), and clause 57 the Scrutiny Committee requested that the key information provided by the Minister be included in the Explanatory Memorandum, but noted that it left the ‘question of whether the proposed approach is appropriate to the Senate as a whole’.[51] In relation to clause 93, the Scrutiny Committee thanked the Minister for his response, indicating that its concerns had been addressed.[52]

The Scrutiny Committee’s other concerns about personal rights and liberties included that clause 72 provides for authorised officers to enter premises (including residential premises in some cases) without a warrant.[53] The Scrutiny Committee noted that in general entry should be by consent or under a warrant, and that the explanatory materials did not contain a compelling explanation for a departure from this principle.[54] After reviewing the Minister’s response, the Scrutiny Committee noted that it:

... retains its concern about these entry powers. The Minister emphasises the importance of the efficient and effective resolution of investigations and claims to justify entry without consent or warrant. It is not clear to the committee why these concerns are of greater relevance in the industrial relations context than other regulatory contexts in which these powers are not available. As such, the committee is not persuaded that a compelling justification has been established for the proposed powers.[55]

The Scrutiny Committee requested further advice from the Minister ‘as to whether consideration has been given, or can be given, to establishing a requirement for reporting to Parliament on the exercise of these powers’.[56] After considering the Minister’s further response, the Scrutiny Committee noted that whilst the provisions are ‘primarily based on existing and previous provisions’:

...this does not, of itself, address the committee's scrutiny concerns. The committee does not consider that the requirements of investigative efficiency or the resource implications of obtaining warrants provide sufficiently compelling justification for the use of such coercive powers.[57]

The Scrutiny Committee noted that it left the ‘question of whether the proposed approach is appropriate to the Senate as a whole’.[58]

The Scrutiny Committee noted that subclauses 76(4), 77(4) and 99(8) provide that civil penalties for failure to comply with requests for information do not apply if the person has a reasonable excuse, but that there is no guidance as to what is a reasonable excuse.[59] The Scrutiny Committee noted that the examination powers (clause 61) may trespass on the right to privacy, but that there is a justification for, and some safeguards around, the use of the power.[60] After reviewing the Minister’s responses in relation to the above, the Scrutiny Committee requested that the key information provided by the Minister be included in the Explanatory Memorandum, but noted that it left the ‘question of whether the proposed approach is appropriate to the Senate as a whole’.[61]

The Scrutiny Committee observed that subclause 120(3) would enable certain rules (made for the purposes of subclauses 6(4), 6(5) or 10(2)) to take effect from the commencement of the subsection if the rules were made within 120 days. This would mean that the rules could operate retrospectively.[62] After reviewing the Minister’s responses in relation to the above, the Scrutiny Committee requested that the key information provided by the Minister be included in the Explanatory Memorandum, but noted that it left the ‘question of whether the proposed approach is appropriate to the Senate as a whole’.[63]The Scrutiny Committee raised the question of whether the provision in clause 86 that the rules of evidence and procedure for civil matters (and not those for criminal matters) apply in relation to the civil remedy provisions is consistent with rights associated with a fair trial, but stated that it would wait for any views that may be expressed by the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights (PJCHR). The PJCHR views on that issue are examined below.[64]

The Scrutiny Committee noted that the Bills confer broad powers which in some cases are not sufficiently defined. These include the power of the Minister to appoint a Commissioner who has ‘suitable qualifications or experience’ and is of ‘good character’ (subclause 21(3)); the power of the Commissioner to appoint as an Australian Building and Construction Inspector a ‘consultant’ (paragraph 66(1)(c)) who has ‘suitable qualifications and experience’ to be a consultant (clause 32); and the similar power of the Federal Safety Commissioner (subclause 68(1)(c)). The Scrutiny Committee also noted that clause 28 does not require the Minister to provide reasons when terminating the appointment of a Commissioner.[65]

In relation to the appointment of the Commissioner (subclause 21(3)) the Scrutiny Committee noted the Minister’s response that ‘the appointment of a person as ABC Commissioner is subject to the Australian Government Merit and Transparency Policy administered by the Australian Public Service Commission’.[66] In relation to paragraphs 66(1)(c) and 68(1)(c) (appointing consultants as ABC Inspectors and Federal Safety Officers respectively) and clause 28 (merits review of reasons for terminating the appointment of a Commissioner), the Scrutiny Committee requested that the key information provided by the Minister be included in the Explanatory Memorandum, but noted that it left the ‘question of whether the proposed approach is appropriate to the Senate as a whole’.[67]

The Scrutiny Committee raised concerns about the level of penalties in clause 49 and clause 81, noting in particular the great differences between them and similar penalties in other Commonwealth legislation, including the FWA.[68] After reviewing the Minister’s response, the Scrutiny Committee requested that the key information provided by the Minister be included in the Explanatory Memorandum, but noted that it left the ‘question of whether the proposed approach is appropriate to the Senate as a whole’.[69]

Finally, the Scrutiny Committee noted that the original Explanatory Memorandum was ‘regrettably brief and uninformative’.[70] The Scrutiny Committee’s recommendations for additional material to be included in the Explanatory Memorandum have not been acted upon, as the Explanatory Memorandum for the current Bills is in the same terms as the original Explanatory Memorandum.

Consideration by the Senate Education and Economics References Committee in 2013/14

On 4 December 2013 the Senate referred the Government’s approach to re-establishing the ABCC to the Senate Education and Economics References Committee (References Committee) for inquiry and report by 27 March 2014. Details of the inquiry and the Reference Committee’s report are available at the inquiry web page.[71] The References Committee’s report recommended that the Bills not be passed.[72] It concluded that:

... in view of the failure of the government and proponents of the re-establishment of the ABCC to:

- Establish an economic or productivity case for the ABCC;

- Address the very serious incursions on human rights in the bills;

- Establish the uniqueness of the building and construction industry sufficient to warrant draconian powers and penalties;

- Establish that the coercive powers proposed for the ABCC are subject to sufficient oversight and safeguards;

- Establish that the ABCC would improve occupational health and safety in the building and construction industry;

the Senate not support the re-establishment of the Australian Building and Construction Commission and accordingly, not pass the Building and Construction Industry (Improving Productivity) Bill 2013 and related bill.[73]

In a dissenting report, Coalition Senators strongly criticised the Reference Committee’s Inquiry into the Bills, stating that it was:

...at best been an abuse of process and at worst a meaningless exercise, given that the same witnesses did or could have appeared at the Legislation Committee inquiry.[74]

The dissenting Coalition Senators noted that they stood ‘by the Legislation Committee’s report and recommendations of December 2013’ and, therefore, recommend that the Bills be passed.[75]

Policy position of non-government parties/independents

The Opposition

The Opposition, in the Second Reading Debate in the House of Representatives when the Bills were first introduced in 2013, opposed the legislation.[76] During that debate, the Shadow Minister for Employment and Workplace Relations, Mr Brendan O’Connor argued that the performance of Fair Work Building and Construction (FWBC) had in fact been superior to the ABCC’s in terms of productivity and industrial disputation.[77]

During the Second Reading Debate in the House of Representatives that followed the reintroduction of the Bills in February 2016, Mr O’Connor described the proposed powers of the ABCC as ‘extreme, unnecessary and undemocratic’ and claimed that they compromise civil liberties.[78] He also noted the Government’s reliance on the Cole Commission, which was initiated on allegations of lawlessness but did not lead to ‘one single criminal prosecution, let alone any finding of guilt’.[79]

Since the election, whilst the Opposition reaffirmed its opposition to the Bills, it has indicated a willingness to negotiate with the non-Government Senators and the Government regarding certain aspects of the Bill:

But we'll look at the Bill... Certainly the crossbenches are open to the Federal Opposition’s views and they’re open to negotiations, so we’re going to present in good faith our concerns about the Bill and look we’ll be involved in the discussions, we want to get the best outcome. We don’t agree with the Bill but we’ll be aiming to ensure that workers are not worse off, that workers are not endangered by the introduction of this Bill. So, we want to test that with the Senators, particularly those who have been recently elected.[80]

The Australian Greens

The Australian Greens, in the dissenting report on the Senate Education and Economics Committee inquiry, as noted above, recommended that the Bills not be passed. Mr Adam Bandt of the Greens has said of the Bills:

This is the curtain-raiser to the government’s return to Work Choices. They want to wind up on the unions and then they will come after the people’s rights at work. We won’t be part of it.[81]

In the recent Second Reading Debate in the House of Representatives in February 2016, Mr Bandt opposed the Bill and instead advocated for the establishment of a broad-based ‘national anticorruption watchdog’.[82] There is no indication that since the election this position has changed.

Other non-government parties and independents

Nick Xenophon Team

Senator Xenophon voted for the second reading stage of the original Bills in the Senate in 2015, but reserved his ‘position on the third reading’.[83] During his contribution, Senator Xenophon noted:

- there is a need for ‘tougher laws in place when it comes to workplace safety’ and that ‘insofar as unions require a right of entry for the purpose of safety issues, then I think that is quite fundamental and ought not to be derogated from’

- that the concerns raised through the RCTUGC and the Boral court case could not be ignored[84] and

- that he had ‘supported, unambiguously, the need to give the fair work building inspectorate the coercive powers to call in witnesses just as the ACCC, ASIC and other key regulators have’ as ‘without those powers, you will not get in my view some witnesses coming forward’.[85]

However, Senator Xenophon also posed the question: ‘are the measures in these Bills fair and proportionate to the issues that they are trying to address?’ and suggested that as there may be ‘legitimate concerns in other sectors’, there could be potential ‘benefit from the oversight provisions in these Bills’ being extended more broadly.[86] Ultimately, Senator Xenophon concluded that:

At the end of the day—and I emphasise this—I want there to be a strong building and construction industry in this country. Building and construction can provide a real antidote to the job losses we are expecting in manufacturing. Having people working in a safe, working environment on good incomes is absolutely fundamental. My concern is that there needs to be some reform to help facilitate that. The issue is: to what extent do you go in this legislation? I think it is worth having this Bill go into committee for further negotiations in respect of this.[87]

Since the election, media reports suggest the Nick Xenophon Team Senators and House of Representatives Member, Rebekha Sharkie, may support the Bill provided it is amended to:

- require oversight of the use of the ABCC’s coercive powers by the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT)

- address ‘unconscionable’ subcontracting practices (for example, by providing security of payments for subcontractors)

- include ‘buy Australian’ procurement measures in the construction code and

- ensure that unions have ‘adequate rights’ to enter building sites ‘for the purposes of safety issues’.[88]

One Nation

Media reports suggest that at the time of publication of this Digest, One Nation had not determined whether it would support the Bill in its current form.[89]

Senators Day, Hinch, Lambie and Leyonhjelm

Senator Day

Senator Bob Day supported the original Bill, noting that ‘we are having this debate about reinstating the Australian Building and Construction Commission... because the ABCC is the only body capable of keeping the CFMEU in check on commercial building sites.’[90] Senator Day noted:

The previous Labor government deliberately removed any notion that it was necessary to constrain criminal behaviour by certain unions. They were prepared to tolerate criminal behaviour—a failure. The police have failed to uphold the law in favour of so-called keeping the peace. They will tolerate criminal behaviour if it means keeping the peace...[91]

Senator Day concluded that ‘whilst I am not generally in favour of expanding government power, the situation in the commercial construction industry has become so bad that we need to restore the ABCC. I support the Bill’.[92] Recent media reports suggest he continues to support the Bills,[93] with the Senator reportedly stating:

On any other issue I’d be seriously rethinking my position and not being so accommodating but I have to put my own feelings about the government to one side and support restoring the ABCC.[94]

Senator Hinch

Media reports suggest that Senator Derryn Hinch may support amended version of the Bills.[95]

Senator Lambie

Senator Jacqui Lambie opposed the original Bill, stating that ‘the intent of this Bill is to target and punish unions and organised labour groups, while neglecting to impose the same set of rules and standards on corporate Australia.’[96] Senator Lambie, like a number of other independents and the Greens, also referred to the idea of establishing a broad-based anticorruption ‘watchdog’:

I believe that an equitable solution to corruption in the workplace and broader Australian society is the establishment of a permanent corruption watchdog whose star chamber powers will apply to bankers and union members equally. They must be applied equally. Combine that body with reformed world's best whistleblower or public interest disclosure laws that protect, encourage and reward genuine whistleblowers to come forward and then corruption in the workplace, corruption in government departments, corruption in the board rooms and corruption in political parties will be properly addressed.[97]

Senator Lambie concluded that she would oppose the Bills because:

In the rush to achieve a quick outcome or get an easy conviction through bypassing the existing system of law and order, Australia runs the risk of damaging fundamental human and civil rights—building blocks of our nation.[98]

Recent media reports suggest that Senator Lambie remains opposed to the Bills, and has renewed her calls for a ‘national ICAC’.[99]

Senator Leyonhjelm

Senator David Leyonhjelm voted in favour of the original Bill in 2015.[100] In addition, he also moved an amendment to the Bill that would have subjected the entire Bill to an eight-year ‘sunset’ clause.[101] Some recent media reports suggest that Senator Leyonhjelm may not support the Bills without amendments, with the Senator reported as stating:

There are reasons now why I have reconsidered my position on the ABCC. I’m doubtful whether it will achieve the government’s objective of cleaning up the building industry. It is highly coercive legislation. I was previously inclined to give the government the benefit of the doubt because it had been an election promise — that was basically a good-will factor. And there is no good will left any more. There’s a 50-50 chance I will vote for it at the second reading — I have done so twice previously — but there’s a less than 50 per cent chance I will vote for it at the third reading. I’d need to be persuaded to change that position.[102]

Ms McGowan, Mr Katter and Mr Wilkie

Ms Cathy McGowan, whilst not speaking to the Bill, voted in favour of the Bills in December 2013 and February 2016.[103] It does not appear that her position has changed since the election.

During the February 2016 Second Reading Debate in the House of Representatives, Mr Katter referred to both the importance of trade unions generally (in relation to workplace health and safety) and the undesirability of the Bill’s proposals to remove the right to silence and compel people to give evidence:

You can sit and spit upon trade unions as much as you like. But we could be still out there and dying. Don't think it would not be happening... The minister spoke about the rule of law. That is rather interesting. There are three great pillars of the rule of law, and one of them is your right to silence... Well, you do not have it in the building industry! You get put in jail if you remain silent. So do not come in here and preach about the rule of law, because you are spitting upon the rule of law in this legislation. If you want to fix up bad things, you make the effort of going in there and weed out the grafters who have pulled stunts when the concrete is being poured, and getting paid, personally—in their own pockets, not in the pockets of the union—and you track them down and put them in jail. Do not take away, from a whole branch of industry in Australia the right to work safely... So, your right to remain silent is a very important law. This legislation takes away your right to remain silent. And not only does it take away your right to remain silent; it also says that you have to give evidence. If you are asked to give evidence, you are compelled to give that evidence.[104]

Recent media reports indicate that Mr Katter remains opposed to the Bills, with Mr Katter reportedly stating that if the Government proceeded with the Bills ‘this is going to antagonise me’.[105]

Mr Wilkie voted against the Bills in December 2013 and February 2016.[106] Media reports suggest his position has not changed since the election.[107]

Position of major interest groups

Major employer groups including the Master Builders Association (MBA), the Housing Industry Association (HIA), the Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (ACCI), and the Australian Industry Group (AiG) welcomed the original Bill, saying that it would restore the rule of law in the building and construction industry. They particularly endorsed the extension of the Act to unlawful picketing.[108]

AiG expressed reservations about the extension of the scope of the Act to the supply of materials because it may be a vehicle for extending construction industry terms and conditions of employment and the influence of the CFMEU.[109] However, HIA welcomed the extension, saying that offsite disputes are as disruptive as onsite action.[110]

Trade unions oppose the Bill. The Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) opposes any special laws for the building and construction industry. It notes that the assertion that the Bill deals with criminal activity in the industry is incorrect, as the Bill deals with civil actions and penalties. It contests the Government’s assertions about the increase in productivity attributable to the ABCC. It notes that the BCII Act was several times found to be in breach of International Labour Organisation conventions which Australia has ratified. Like the AiG, it is concerned that the extension of the scope of the Bill may bring parts of the transport, warehousing and manufacturing industries into the scope of the ABCC. It opposes the coercive information gathering powers in the Bill, and particularly the removal of safeguards on their exercise. It opposes giving the ABCC the right to intervene in proceedings under the FWA or the Independent Contractors Act 2006, or to re-open matters that have been settled. It opposes the transition provision which allows the ABCC to use its new powers in investigations of matters that happened before the Act takes effect, and particularly the provision that the ABCC can pursue matters which were settled before the Act takes effect.[111]

The CFMEU submission endorsed the ACTU’s. It also discussed the ABCC’s far greater focus on illegal activity by unions than by employers.[112]

Financial implications

The Government previously committed an additional $35 million over four years to the re-established ABCC.[113]

Statement of Compatibility with Human Rights

As required under Part 3 of the Human Rights (Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011 (Cth), the Government has assessed the Bills’ compatibility with the human rights and freedoms recognised or declared in the international instruments listed in section 3 of that Act. Noting that the Bills engage the rights to freedom of association, to just and favourable conditions of work, to a fair trial, to peaceful assembly, to freedom of expression, and to privacy and reputation, the Government considers that the Bills are compatible, because to the extent that they may limit human rights, those limitations are reasonable, necessary and proportionate.[114]

Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights

The PJCHR commented on the Bills in February 2016 by referring to its comments on the 2013 Bills in its second report for the 44th Parliament.[115] In that report, the PJCHR summarised its concerns as follows:

The committee seeks further information on various aspects of these Bills to determine their compatibility with the right to equality and non-discrimination, the right to freedom of association and to engage in collective bargaining, the right to freedom of assembly, the right to freedom of expression, the right to privacy, the right to a fair hearing, and the prohibition against self-incrimination.[116]

After considering additional information provided by the Minister in relation to the above, the PJCHR concluded:

- clause 59 (project agreements) is likely to be incompatible with the right to organise and bargain collectively[117]

- the proposed coercive evidence-gathering powers ‘are likely to be incompatible with the right against self‑incrimination’[118]

- the prohibition on picketing and further restrictions on industrial action are ‘incompatible with the right to freedom of association and the right to form and join trade unions’[119]

- the prohibition on picketing is also ‘likely to be incompatible with the right to freedom of assembly and the right to freedom of expression’[120] and

- subclause 61(7) and clause 105 (that deal with the disclosure of information obtained by the ABCC) are incompatible with the right to privacy.[121]

Key issues and provisions

The Bill re-establishes the ABCC, with some new (but significant) differences. As such, the Bill is consistent with recommendation 61 of the RCTUGC (that a building and construction industry regulator should exist, and be separate from the office of the Fair Work Ombudsman).[122] However, given the similarities between the Bill and the Building and Construction Industry Improvement Bill 2003 and the BCII Act, this Bills Digest focuses on the differences and key areas that may attract controversy. It is strongly recommended that readers refer to the following publications, which are cited earlier in this Digest, for additional analysis:

- A Holmes and J Murphy, Building and Construction Industry (Improving Productivity) Bill 2013 [and] Building and Construction Industry (Consequential and Transitional Provisions) Bill 2013, Bills digest, 34, 2013–14, Parliamentary Library, Canberra, 2014

- S O’Neill and MA Neilsen, Building and Construction Industry Improvement Amendment (Transition to Fair Work) Bill 2011, Bills digest, 80, 2011–12, Parliamentary Library, Canberra, 2011

- S O’Neill and MA Neilsen, Building and Construction Industry Improvement Amendment (Transition to Fair Work) Bill 2009, Bills digest, 16, 2009–10, Parliamentary Library, Canberra, 2009

- P Prince, Building and Construction Industry Improvement Bill 2005 [and] Building and Construction Industry Improvement (Consequential and Transitional) Bill 2005, Bills digest, 139–140, 2004–05, Parliamentary Library, Canberra, 2005 and

- P

Prince and J Varghese, Building

and Construction Industry Improvement Bill 2003, Bills digest, 129,

2003–2004, Parliamentary Library, Canberra, 2004.

The main issues raised by the Bill, where they differ substantially from the BCII Act, are discussed below.

Expanded coverage of the Bill

A number of provisions seek to expand the application of the Bill.

Geographical jurisdiction

Clauses 5, 10, 11 and 12 extend the geographical application of the Act to:

- Australia's exclusive economic zone (EEZ) and waters above the continental shelf (including resources platforms and ships in the EEZ or those waters) and

- Christmas Island and Cocos (Keeling) Islands.[123]

Industry coverage

Clause 6 contains the definition of building work, a key term that underpins the operation of the Act. The Bill defines building work as encompassing a broad range of activities including: construction, restoration, repair and demolition, any operation that is ‘part of or preparatory to’ such activities, and ‘pre fabrication of made-to-order components’ whether carried out on-site or off-site.

Paragraph 6(1)(e) expands the definition of building work to include the supply and transport of building goods directly to building sites (including resource platforms) for subsequent use in building work. The Explanatory Memorandum states that the expanded definition of building work is ‘not intended to pick up the manufacture of those goods’.[124]

The Bill retains the exclusions for small-scale residential construction projects and mineral exploration activities, contained in the BCII Act and the FWBI Act.[125]

Ancillary sites

Clause 9 defines ancillary sites. Relevantly, this includes sites from which goods are transported or supplied directly to a building site or sites where building industry participants do work relating to building work. This concept was not included in the BCII Act or the FWBI Act.

Impact of expanded coverage

The effect of the above provisions is to effectively extend the operation of the Bill to the transport, supply and resources sectors both within Australia and also to operations conducted in Australia’s EEZ or in waters above the continental shelf, provided there is a relevant connection to building work as defined in the Bill.[126] As a result, arguably the Bill could therefore be used to target secondary boycotts (an issue raised by the PC Report and Harper Review), at least in relation to coercing a person or third party to engage (or not engage) a particular independent contractor or building contractor.[127]

Coercive powers

The table in Appendix D provides a summary of the differences between the current coercive powers under the FWBI Act and those proposed by the Bill. A detailed analysis follows below.

Current coercive powers

The FWBC retained the powers originally provided by the BCII Act to the then ABCC to require a person to give information, produce documents and attend an interview to answer questions. However, the FWBI Act introduced a number of safeguards on the use of the coercive powers. Importantly these include that:

- the FWBC must apply for an examination notice to a Presidential Member of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT)[128] who

- must be satisfied that a case has been made out for its use.[129]

The FWBI Act also provides that the Commonwealth Ombudsman must be notified whenever an examination notice is issued.[130] Further, the FWBC must provide a report on, and video recording and transcript of, the examination to the Commonwealth Ombudsman, who must then review the examination and provide annual reports to Parliament.[131]

Proposed coercive powers

The Bill re-instates the previous coercive investigatory powers of the Commissioner under the BCII Act, and hence reflects recommendation 62 of the RCTUGC.[132] Where the Commissioner reasonably believes that a person has information or documents relevant to an investigation or is capable of giving evidence relevant to an investigation, Chapter 7, Part 2 of the Bill provides that the Commissioner can require a person to:

- give information or produce documents to the Commissioner[133]

- attend an examination before the Commissioner[134] and

- answer questions or provide information under oath or affirmation.[135]

In addition, where (amongst other reasons) an inspector reasonably believes that the Act, a designated building law[136] or the Building Code is being breached they can:

- enter a premises without force[137]

- require a person to provide their name and address[138]

- inspect any work, process or object

- interview any person

- require a person to produce a record or document

- inspect and make copies of records or documents or

- take samples of any goods or substances.[139]

In addition, outside of the powers related to authorised officers power to enter premises, authorised officers can also issue a notice requiring a person to produce documents or records.[140] In contrast, Federal Safety Officers may only exercise such powers for the purpose of ascertaining if relevant bodies meet and comply with the accreditation requirements, or have complied with the conditions of accreditation in respect of building work.[141]

Once information is obtained clause 105 allow the Commissioner to disclose that information (other than ‘protected information’) in certain circumstances to other persons or bodies, including, for example, where:

... that the disclosure is likely to assist in the administration or enforcement of a law of the Commonwealth, a State or a Territory.[142]

The PJCHR concluded that the information sharing powers proposed by clause 105 are incompatible with the right to privacy.[143]

Ombudsman oversight of use of coercive powers

Unlike the existing Act, the Bill does not require the Commissioner to apply to the AAT for an examination notice.[144] However, the Commissioner must still provide a report on and video recording and transcript of, the examination to the Commonwealth Ombudsman, who must then review the examination and provide annual reports to Parliament.[145] As drafted, the Bills are consistent with recommendation 63 of the RCTUGC.[146]

No privilege against self-incrimination

Clause 102 removes the privilege against self-incrimination by providing that a person is not excused from providing information to the Commissioner because to do so would contravene another law or might tend to incriminate or otherwise expose the person to a penalty or other liability.

Subclause 102(2) provides both use and derivative use immunity by prohibiting the use of any information, answer given or document produced in proceedings other than those related to clause 62 (failing to comply with an examination notice) or proceedings under the Criminal Code Act 1995 related to giving false or misleading statements or documents or obstructing Commonwealth officials.[147] As such, clause 102 effectively replicates section 53 of both the FWBI Act and BCII Act.

In relation to the availability of both use and derivate use immunity, the RCTUGC noted:

Cognate provisions in relation to the compulsory powers of ASIC and the ACCC limit the immunity conferred so that they apply only to the answers given or information provided in response to notices. The immunity under these provisions does not extend to documents and there is no derivative use restriction.[148] (emphasis added)

The RCTUGC then recommended:

Consideration be given to redrafting the use/derivative use immunity provisions in clauses 102 and 104 of the Building and Construction Industry (Improving Productivity) Bill 2013 (Cth) to provide protections equivalent to those available in relation to the powers exercised by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission.[149] (emphasis added).

In summary, the RCTUGC recommended that the above provisions, in relation to use immunity, be narrowed as to only apply to the recipient of the individual notice, and only to answers or information given under compulsion, not to documents obtained or created when the recipient of notice was under no compulsion.[150] In relation to derivative use immunity, the RCTUGC recommended that subclauses 102(2) and clause 104 be amended to remove derivate use entirely as ‘valuable evidence may be acquired by obtaining documents and answers in compulsory examinations’.[151] However, in contrast to the view of the RCTUGC, the PJCHR concluded that the proposed coercive evidence-gathering powers, even with use and derivative use immunity available in some circumstance were ‘likely to be incompatible with the right against self-incrimination’.[152]

Additional protections

Clause 103 extends additional protection to persons who comply with an examination notice by providing that any information, documents or answers to questions cannot be used in any proceedings for contravening any other law because of complying with the examination notice. It also provides that they are not liable in any civil proceedings for any loss, damage or injury of any kind suffered as a result of complying with the examination notice. As such, clause 103 effectively replicates section 54 of both the FWBI Act and BCII Act.

Retrospective operation of coercive investigatory powers

Item 2 of Schedule 2 of the Transitional Bill provides that the powers related to obtaining information apply in relation to any contravention or alleged contravention of either the BCII Act or the existing FWBI Act that occurred or is alleged to have occurred before the transition time.

Criminal Offences

The Bill contains a number of criminal offences similar to those contained in section 52 of the FWBI Act. Under clause 62, it is an offence punishable by six months imprisonment not to comply with an examination notice to:

- provide information

- produce a document

- attend an examination to answer questions

- take an oath or affirmation or

- answer questions during the examination.[153]

The penalties proposed in clause 62 are consistent with recommendation 62 of the RCTUGC and the legislation cited in support of that recommendation.[154]

Clause 106 makes it an offence punishable by 12 months imprisonment for an entrusted person to make a record or disclose protected information, except in specific circumstances. It effectively replicates section 65 of both the FWBI Act and BCII Act.

Civil penalty provisions

The FWBI Act removed the specific penalties for participants in the building industry, making them subject to the ordinary penalties under the FWA.[155] Like the BCII Act, the Bill would restore specific building industry penalties.

The Bill, like the BCII Act, creates two categories of civil penalties:

- Grade A (maximum penalty of 1,000 penalty units for a body corporate and 200 for a natural person) and

- Grade B (maximum penalty of 100 penalty units for a body corporate and 20 for a natural person).[156]

The civil penalty offences created by the Bill are listed in the table in Appendix A. The offences largely replicate the offences contained in the BCII Act (for example, coercion and discrimination) with the exception of the new unlawful picketing civil penalty offence, discussed elsewhere in this Bills Digest.

In this respect, the Bill differs substantially from what the RCTUGC recommended. The RCTUGC recommended that the FWA be amended to increase the maximum penalties for coercion and prohibited industrial action. It also recommended that the FWA be amended so that picketing by employees or employee associations is ‘industrial action’, and to ‘deal specifically with consequences of industrially motivated pickets’.[157]

The Bill (which preceded the RCTUGC) does not seek to amend the FWA in the manner noted above. Instead, it introduces increased penalties for coercion and prohibited industrial action and introduces a picketing offence—but only applies those to the building and construction industry (and associated sectors, as discussed under the heading ‘Expanded coverage of the Bill’ above). As such, whilst civil penalty provisions are consistent with the intent of the recommendations of the RCTUGC, they are applied more narrowly than recommended and hence would only partially fulfil those recommendations.

Industrial action

The Bill, at clause 7, contains its own definition of industrial action. It largely replicates the definition contained in section 19 of the FWA, with one notable difference. Subclause 7(4) provides that where a person claims their action was based on a reasonable concern about an imminent risk to their health or safety, they bear the burden of proving their concern and its reasonableness. However, as noted in the Explanatory Memorandum it ‘does not require the employee to prove that there is in fact an imminent risk’.[158] Subclause 7(4) of the Bill replicates subsection 36(2) of the BCII Act.

For ease of comparison, the definitions of industrial action contained in the BCII Act, the Bill and FWA are set out in Appendix B. Of note, the Bill does not reinstate the BCII Act requirement of industrial action needing to be ‘industrially motivated’ before being unlawful.[159]

Protected industrial action

Clause 8 narrows the scope of protected industrial action in comparison to the definition provided by the FWA. The clause introduces the concept of protected persons, which are:

- an employee organisation or officer of the organisation (within the meaning of the FWA), that is a bargaining representative for a proposed enterprise agreement

- members of the employee organisation employed by the employer (and who will be covered by the proposed enterprise agreement) or

- an employee who is a bargaining representative for the proposed enterprise agreement.[160]

For the purposes of the Bill, action will not be protected industrial action if it is engaged in in concert with one or more non-protected persons.[161] In addition, action will not be protected industrial action if the organisers include one or more non-protected persons.[162]

In effect, industrial action will not be protected under the Bill where it is supported by persons other than those directly involved in the bargaining for the relevant enterprise agreement. This largely replicates subsections 40(1) and (2) of the BCII Act.

Constitutionally covered entities

In New South Wales v Commonwealth (Work Choices case),[163] the constitutional validity of the Workplace Relations Act 1996 (Cth) (as amended by the Workplace Relations Amendment (Work Choices) Act 2005 (Cth)) was challenged. The High Court held that the legislation was a legitimate exercise of the Commonwealth’s corporations power, and as a result, the corporations power is now used as the primary constitutional basis for industrial relations legislation. Since the decision in the Work Choices case, all states other than Western Australia have referred their private sector industrial relations powers to the Commonwealth.[164]

Clause 45 provides that the prohibitions against unlawful industrial action and unlawful picketing must relate to a constitutionally covered entity. The interconnected definitions in clause 5 define a constitutionally covered entity as:

- a corporation to which paragraph 51(xx) (the corporations power) of the Constitution applies

- the Commonwealth or a Commonwealth authority within the meaning given by the Commonwealth Authorities and Companies Act 1997

- a body corporate incorporated in a territory or

- an organisation within the meaning given by the Fair Work (Registered Organisations) Act 2009.

The definition in clause 45 and reference to the corporations power is necessary to ensure the prohibitions against unlawful industrial action and unlawful picketing apply as broadly as possible, within Constitutional limits. Without it, there would be a possibility of parts of the legislation being ruled invalid on the basis of overstepping the Commonwealth’s law making powers.

Despite this, it is likely, however, that not all workers and businesses in the building and construction industry will be covered. It is unclear, for example, whether employees of an unincorporated sub-contractor (which fall outside the corporations power of the Commonwealth to regulate) on a building site would be covered by the Bill, especially if any action they take is only in relation to their own employer.[165]

Unlawful industrial action

Clause 5 provides that action is unlawful industrial action if:

- it is industrial action and

- is not protected industrial action.

As noted previously, the Bill does not reinstate the BCII Act requirement of industrial action needing to be ‘industrially motivated’ before being unlawful.[166]

Effect of new definitions

The new interconnected definitions of industrial action, protected industrial action and unlawful industrial action exclude any industrial action that is not:

- engaged in and organised solely by protected persons (that is, persons directly involved as bargaining representatives in negotiations for, or who will be covered by, a proposed enterprise agreement) and

- authorised through the required protected action ballot process contained in the FWA.

Such action will be unlawful industrial action and, under clause 46 of the Bill, attract a Grade A civil penalty ($34,000 for individual, $170,000 for body corporates). The PJCHR noted that further restrictions on industrial action proposed by the Bill are ‘incompatible with the right to freedom of association and the right to form and join trade unions’.[167]

Unlawful Picketing

Under previous and existing legislation there are no prohibitions on picketing.

New unlawful picketing offence

The Bill creates the new offence of engaging in or organising an unlawful picket, punishable by a Grade A civil penalty ($34,000 for individual, $170,000 for body corporates).[168] To be unlawful, a picket must meet the two limbs provided in paragraphs 47(2)(a) and (b) respectively.

First limb of unlawful picketing

The first limb, in paragraph 47(2)(a), relates to the purpose and impact of the picket. For a picket to be unlawful it must:

- have the purpose of preventing or restricting a person from accessing or leaving a building site or ancillary site or

- directly prevent or restrict a person from accessing or leaving a building site or ancillary site or

- reasonably be expected to intimidate a person accessing or leaving a building site or ancillary site.

However, even if one of the above elements of the first limb is satisfied, a picket will not be unlawful unless it also satisfies one of the four elements contained in the second limb in subclause 47(2). Those elements relate to the motivation or lawfulness of the picket.

Second limb of unlawful picketing

The first two elements of the second limb relate to the motivation of the picket. They provide that (if the first limb is satisfied) a picket will be unlawful where it:

- is motivated for the purpose of supporting or advancing claims against a building industry participant in respect of the employment of employees or

- is motivated for the purpose of supporting or advancing claims against a building industry participant in respect of the engagement of contractors by the building industry participant.[169]

As drafted, a court is required to consider the mental state (motivation) of the participants or organisers of the picket. Due to clause 56, a picket will satisfy either of the above two elements if the reason (or a reason, if there is more than one) it was organised or engaged in was to support one of the specified types of claims against a building industry participant.

As drafted, subparagraph 47(2)(b)(i) is highly unlikely to apply to building industry participants other than building employees, contractors and employee orientated building associations and their officers.

The other two elements of the second limb have a broader scope of application. Relevantly a picket will be unlawful where it:

- is motivated for the purposes of advancing industrial objectives of a building association[170] or

- is unlawful (apart from the operation of clause 47 of the Bill).[171]

In relation to pickets motivated for the purposes of ‘advancing the objectives of a building association’, this would appear to have a broader application than the two elements of the second limb contained in paragraph 47(2)(b)(i) as it can potentially apply to pickets organised or engaged in by persons in support of employer or contractor building associations, and not just to employee building associations.

The final element of the second limb is that the picket is unlawful (apart from the operation of clause 47 of the Bill). The effect of the final element is where persons engage in a picket that:

- is not protected industrial action under the Bill or

- was protected industrial action under the FWA but subsequently the FWC made an order under section 418 of the FWA to stop the action

the action is unlawful for the purposes of subparagraph 47(2)(b)(iii) and hence the picket is unlawful. In addition, the final element of the second limb would also be engaged where the picket breaches relevant state or territory:

- legislation governing protests or

- criminal legislation (for example, trespass).

As a result, a picket will attract the penalty proposed by the Bill where it meets the first limb and is otherwise unlawful or where it was organised to advance various industrial claims. The Explanatory Memorandum notes that clause 47 will not capture pickets that are lawful and organised for non-industrial purposes such as drawing attention to various social, environmental or community issues.[172]

In addition to prohibiting unlawful pickets, clause 48 allows a person to apply to a relevant court for an injunction to prevent an unlawful picket from occurring or to stop an unlawful picket already underway.

As picketing offences will only apply to the building and construction industry (and associated sectors, as discussed under the heading ‘Expanded coverage of the Bill’ above), the provisions discussed above only partially fulfil recommendation 66 of the RCTUGC. That is because the RCTUGC recommended that the FWA be amended (and hence would apply to all industries and sectors covered by that Act) so that picketing by employees or employee associations falls under the definition of ‘industrial action’, and to also deal with the consequences of industrially motivated pickets.[173]

In contrast, the PJCHR stated that the prohibition on picketing proposed by the Bill is ‘likely to be incompatible with the right to freedom of assembly and the right to freedom of expression’.[174]

Prosecution after settlement of civil disputes

Section 73 of the FWBI Act prevents the Commissioner from continuing or instituting proceedings in relation to matters that have been settled by the parties. This Bill does not include a similar clause to prevent such action.

In the second reading speech to the Bill when it was first introduced, the then Minister for Education and Leader of the House stated that:

The inspectorate was hampered by quite novel restrictions on its ability to initiate or continue with proceedings if matters the subject of litigation had been settled by the parties. These amendments were introduced without any prior notice or forewarning by the Leader of the Opposition when he was the responsible minister. They are equivalent to a person running a red light and causing an accident and then police being unable to charge that person with any offences, including running the red light, if that person has settled with the other person involved in the accident.[175]

Hence, it appears that the Commissioner will be able to pursue civil or criminal charges in circumstances where civil liability has been settled.

Clause 20 of Schedule 2 of the Transitional Bill provides that the Commissioner may participate in a proceeding, or institute a proceeding, under the FWBI Act even if the proceeding relates to a matter that was settled before the new Act commences. This is in effect a retrospective provision. It is possible that parties have reached an agreement in good faith on the assumption that that would be the end of the matter, only to have it reopened under a law that was not in force at the time.[176] The Bill, as drafted, is consistent with recommendation 65 of the RCTUGC.[177]

Reverse onus of proof

Clause 57 of the Bill reverses the onus of proof (in relation to reasons for actions) from the Commissioner to the defendant in proceedings related to contraventions of the Bill’s civil penalty provisions.

As a result, in relation to contraventions of the civil penalty provisions (including unlawful picketing), in any proceedings it must be assumed that the relevant action that would constitute a contravention was (or is) being taken by the defendant for the relevant reason or with the relevant intent, unless the defendant proves otherwise. The Explanatory Memorandum refers to section 361 of the FWA, which provides that where a person brings an application for adverse action under Part 3-1, it must be presumed that the action was taken for the alleged prohibited reason.[178] This presumption can, of course, be displaced by evidence led by the respondent (for example, in a general protections case, of the employee’s unsatisfactory performance).