- Bills and Legislation

- Tariff ProposalsBills DigestsBrowse Bills Digests Ordering Printed BillsBudget and Financial LegislationLegislative Instruments

Petroleum and Other Fuels Reporting Bill 2017 [and] Petroleum and Other Fuels Reporting (Consequential Amendments and Transitional Provisions) Bill 2017

Bills Digest No. 118, 2016–17

PDF version [633KB]

Alex St John and Sophie Power

Science, Technology, Environment and Resources Section

22 June 2017

Contents

What do the Bills do?

Why has the Government introduced the Bills?

What do other people think?

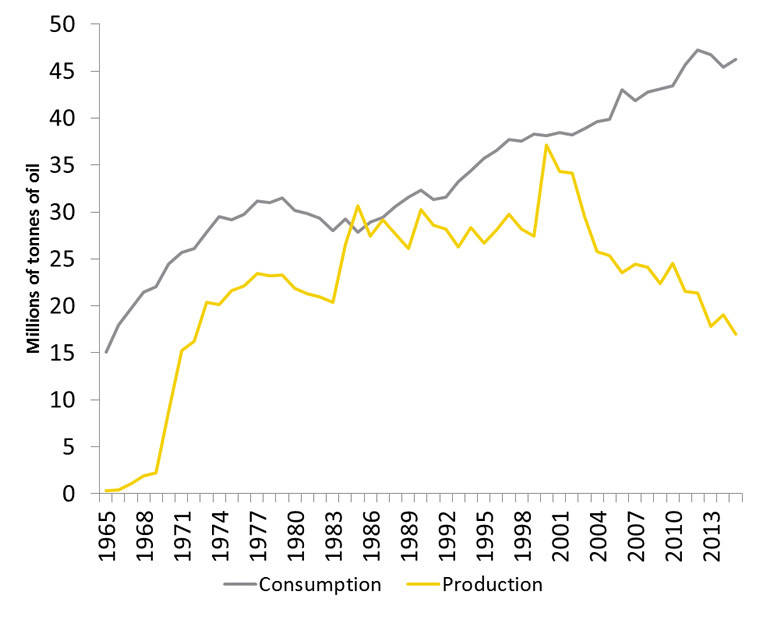

Graph 1: Australian production and consumption of oil, 1965–2015

Policy position of non-government parties/independents

Position of major interest groups

Statement of Compatibility with Human Rights

Petroleum and Other Fuels Reporting Bill 2017

Objects of the Bill

Reporting scheme coverage

Obligation to report

Collection and publication of information

Protection of collected information

Enforcement of obligation to report

Petroleum and Other Fuels Reporting (Consequential Amendments and Transitional Provisions) Bill 2017

Date introduced: 30

March 2017

House: House of

Representatives

Portfolio: Environment

and Energy

Commencement: The

day after Royal assent.

Links: The links to the Bills, their Explanatory Memoranda and second reading speeches can be found on the home page for the Petroleum and Other Fuels Reporting Bill 2017 and the Petroleum and Other Fuels Reporting (Consequential Amendments and Transitional Provisions) Bill 2017 or through the Australian Parliament website.

When Bills have been passed and have received Royal Assent, they become Acts, which can be found at the Federal Register of Legislation website.

All hyperlinks in this Bills Digest are correct as

at June 2017.

The Bills Digest at a glance

What do the Bills do?

The Petroleum and Other Fuels Reporting Bill 2017 (the Reporting Bill) and the Petroleum and Other Fuels Reporting (Consequential Amendments and Transitional Provisions) Bill 2017 (the Consequential Amendments Bill) establish a scheme for the mandatory reporting of fuel information to the Department of Environment and Energy. The Bills establish an obligation for certain regulated entities involved in the production, refining, import, export, stockholding or wholesaling of a range of petroleum fuels to provide information relating to those activities to the Department, and provides measures for enforcing compliance with the scheme. The Bills also provide protection for information gathered under the reporting scheme, and penalties for the unauthorised use, recording or disclosure of the protected information.

Why has the Government introduced the Bills?

Australia is a member of the International Energy Agency and a signatory to its founding treaty. As such, Australia is required to maintain, and report on, emergency oil reserves equivalent to 90 days’ worth of net oil imports. However, Australia has been non-compliant with its obligations for some time, and introducing mandatory reporting of fuel statistics is part of the Government’s plan to return to compliance. The Government argues the current method of collecting fuel information (by a voluntary survey), is no longer of acceptable quality or coverage due to increasing non-participation in the survey by industry participants.

What do other people think?

Reaction to the idea of a mandatory petroleum reporting scheme has been mixed—some petroleum producers believe it will impose an unnecessary regulatory burden, whilst some downstream petroleum businesses as well as motoring groups have welcomed the initiative in the interests of greater transparency in the transport fuels sector.

Purpose of the Bills

The Petroleum and Other Fuels Reporting Bill 2017 (the Reporting Bill) establishes a scheme for the compulsory collection of data related to the production, refining, trade and stockholding of certain petroleum products; establishes legal protections for data so collected; and provides measures for enforcing compliance with the mandatory reporting regime.

The Petroleum and Other Fuels Reporting (Consequential Amendments and Transitional Provisions) Bill 2017 (the Consequential Amendments Bill) amends the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 and the Taxation Administration Act 1953 to provide that the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission and the Australian Taxation Office may lawfully provide otherwise confidential information to the Department of the Environment and Energy for the purposes of administering the petroleum reporting scheme.

Structure of the Bills

The Reporting Bill has six parts:

- Part 1 deals with preliminary matters, including important definitions of covered fuels and activities

- Part 2 establishes the duty of regulated entities to provide a report to the Secretary of the Department of the Environment and Energy regarding certain covered petroleum activities and products

- Part 3 permits the Secretary of the Department to collect and publish information regarding covered petroleum products

- Part 4 contains secrecy provisions protecting collected information, and provisions limiting the recording, use and disclosure of protected information

- Part 5 sets out powers to enforce the scheme’s obligations using the Regulatory Powers (Standard Provisions) Act 2014 and

- Part 6 deals with miscellaneous matters regarding the treatment of trusts; delegation of powers; a review of the proposed Act; and the creation of legislative rules.

The Consequential Amendments Bill has one schedule that makes consequential amendments to two Acts, and clarifies when and where the scheme will be applied.

Background

Australia is a member of the International Energy Agency (IEA), and a signatory to the Agreement on an International Energy Program that created it.[1] That agreement was concluded in response to the oil shock of 1973–4, in which the Organisation of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries heavily restricted oil exports in response to geopolitical events, which had significant ramifications for the global economy.[2] The agreement (and the IEA) seeks to ameliorate the impacts of further interruptions to oil supply, and encourage members to work collectively to ensure security of energy supplies (particularly oil).[3]

A key requirement of IEA membership (and the Agreement on an International Energy Program) is that countries that are net importers of oil maintain a stockpile equivalent to 90 days’ worth of imports.[4] In the time that Australia has been a member, particularly between 1985 and 2000, Australia’s oil production and consumption have been comparable. This meant Australia was essentially self-sufficient in oil, and exempt from the requirements to keep a 90-day reserve. However, Australia’s oil production peaked in 2000, and since then the widening gap between consumption and production has been met by imports (see graph 1)[5]. Despite this increased reliance on imports, the Government admits that Australia has not maintained a 90-day stockpile and has been in breach of its obligations since March 2012;[6] as at January 2017, Australia had only 48 days’ worth of imports—the only IEA member country to be in breach of its obligations.[7]

Graph 1: Australian production and consumption of oil, 1965–2015

Source: British Petroleum (BP), BP statistical review of world energy June 2016, BP, London, 2016.

Australia’s liquid fuel security has been the subject of considerable discussion over the last few years, particularly in the context of oil refining capacity in Australia being withdrawn. Motoring lobby group the National Roads and Motorists’ Association has released several reports, which it argues highlight Australia’s vulnerability to import disruptions.[8] Vulnerability to supply chain disruptions has been demonstrated recently in Australia although imports were not always to blame; Melbourne Airport has experienced at least two shortages of jet fuel due to delayed shipments in 2015 and 2016,[9] and a diesel shortage in Victoria in late 2012 was blamed on storm damage to the refinery at Geelong.[10]

The Government and some stakeholders have argued that the current mode of collection of fuel statistics, a voluntary survey, is no longer adequate as some industry participants do not take part in the survey. In order to improve the quality and completeness of information on Australia’s fuel holdings (and hence information on its compliance with IEA obligations), the Government has proposed that reporting of fuel information be made mandatory.[11]

In the 2013–14 Budget, the Gillard Government announced that it would provide the then-Department of Resources, Energy and Tourism (RET) with $5.1 million to study a return to compliance with Australia’s IEA obligations, and introduce mandatory fuel reporting.[12] RET launched a consultation process on mandatory data reporting in mid-2013, inviting submissions from industry.[13] However, the mandatory data reporting scheme did not appear to have gone any further at that point—it seems to have been overtaken by the policy push to reduce the size and scope of government activity in the early days of the Abbott Government, with a view to ‘reduce burden on industry’.[14]

The Senate Standing Committee on Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport (the Committee) conducted an inquiry in early 2015 into Australia’s Transport Energy Resilience and Sustainability, which examined Australia’s compliance with its IEA obligations.[15] That report recommended:

- the Government conduct a comprehensive risk assessment of Australia’s fuel supply, availability and vulnerability

- that monthly mandatory fuel reporting be introduced and

- that the Government should develop a comprehensive Transport Energy Plan.[16]

The Government announced in the 2016–17 Budget that it would provide $23.8 million to the Department of Industry, Innovation and Science (then responsible for energy policy) over four years to work towards returning to compliance with the IEA requirements.[17] The Government also provided a plan to the Governing Board of the IEA to return to compliance by 2026, a part of which was establishing a mandatory data reporting scheme by 1 January 2018.[18] The Government issued its response to the Committee’s report in November 2016, outlining relevant parts of the plan to return to compliance.[19] The Government agreed with two of the committee’s recommendations, relating to developing a whole-of-government risk assessment of Australia’s fuel supply, availability and vulnerability, and implementing mandatory petroleum information reporting. It disagreed with a recommendation to develop a Transport Energy Plan directed at achieving a secure, affordable and sustainable transport energy supply, arguing that the 2015 Energy White Paper fulfilled this role.[20]

The Department of the Environment and Energy released a consultation paper in September 2016 on the design of a mandatory reporting scheme, inviting submissions from industry stakeholders.[21] The consultation received 18 submissions, of which only 10 were published. Matters raised in the submissions were varied, but recurrent themes included:

- changes from the existing voluntary reporting scheme for the Australian Petroleum Statistics should be minimal, with some improvements to the quality and coverage of the data collected

- costs to industry and motorists should be minimised and

- expanded data-sharing across government agencies should be employed to reduce the burden of compliance.

Support for the scheme was split. Upstream (production) industry stakeholders Chevron and the Australian Petroleum Production and Exploration Association complained of increased regulatory burden and a lack of rigorous justification or cost-benefit analysis.[22] In contrast, consumers, motoring groups and downstream (wholesale and retail) industry stakeholders were generally supportive of the move.[23]

After consultation, the Government has continued to propose a comprehensive mandatory petroleum data reporting scheme, which this Bill would legislate. The Department of the Environment and Energy is continuing to undertake consultation on detailed scheme design elements that will presumably be matters covered by legislative rules if the proposed mandatory reporting scheme is enacted.[24]

Committee consideration

As of the time of writing, the Bills have been deferred to the next meeting of the Senate Standing Committee for the Selection of Bills.[25]

The Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills considered the Bills in its fifth scrutiny digest of 2017. In that report, the Committee raised concerns that the Reporting Bill allows the Secretary to delegate coercive powers (in this instance, powers to compulsorily monitor compliance with the mandatory fuel reporting scheme) to an unduly broad range of persons, without regard to their qualifications or attributes. The Committee requested the Minister’s advice on this issue, including whether the Reporting Bill could be amended to restrict the provision of coercive powers to Australian Public Service Employees of Executive level or higher, and/or to provide stronger legislative guidance as to the circumstances under which contractors or consultants may be authorised to monitor compliance with the scheme.[26]

The Minister has responded to the Committee's comments, as set out in the sixth scrutiny digest. The Minister advised that he did not see any need to amend the Bill as requested by the Committee. In particular, he did not consider it appropriate to limit the appointment of authorised persons to SES or Executive level employees, given the Department’s existing practices whereby the Secretary currently delegates some compliance monitoring powers under other legislation to relatively junior employees. The Minister advised that ‘with effective training, clear guidance and appropriate direction’, the Department ‘has found that APS level staff are more than capable of effectively exercising compliance monitoring powers’.[27] In relation to whether the Bill should provide further guidance on the circumstances and conditions under which the Secretary may appoint an authorised person, the Minister considered ‘it more appropriate to leave the determination of what qualifications or experience is required to the discretion of the Secretary of the Department’.[28]

The Committee noted the Minister’s advice, but considered that it would be appropriate if the power to delegate to any APS employee in the Department or to a consultant or contractor were limited to those with appropriate training in the use of compliance monitoring powers. The Committee further requested that the key information provided by the Minister be included in the Explanatory Memorandum. Finally, the Committee drew its scrutiny concerns to the attention of Senators and left to the Senate the appropriateness of allowing for a broad delegation of coercive powers.[29]

The Scrutiny of Bills Committee had no comment on the Consequential Amendments Bill.[30]

Policy position of non-government parties/independents

As at the time of writing, no non-government parties or independents had expressed a position on the Bills. However, the 2015 Senate Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport Committee report recommending the introduction of mandatory reporting was a bipartisan report, with the Australian Greens making additional comments relating to reducing the need for fossil fuel use in transport.[31]

Position of major interest groups

There has not yet been commentary by stakeholders relating to the Bills, however, their positions on mandatory reporting were established in the consultation process undertaken by the Department of the Environment and Energy, outlined earlier.

Financial implications

The Bill makes no special appropriations, nor imposes taxation, however, it does impose a new duty on the Secretary of the Department that will require financial resources to administer. The Explanatory Memorandum states that $1.9 million has been allocated from the 2016–17 Budget to establish the mandatory fuel reporting scheme, and that ongoing resources for the administration of the scheme will come from within the Department’s existing budget allocation.[32]

This Bill would also impose additional reporting requirements on regulated entities in relation to fuel activities, which would undoubtedly have some financial impact. However, no Regulation Impact Statement appears to have been released.

Statement of Compatibility with Human Rights

As required under Part 3 of the Human Rights (Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011 (Cth), the Government has assessed the Bills’ compatibility with the human rights and freedoms recognised or declared in the international instruments listed in section 3 of that Act. The Government considers that the Bills are compatible.[33]

The Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights considered that the Bills do not raise human rights concerns.[34]

Key issues and provisions

Petroleum and Other Fuels Reporting Bill 2017

Objects of the Bill

Clause 3 sets out the objects of the Reporting Bill and the proposed mandatory fuel reporting scheme. Those objects include to:

- assist the Commonwealth to monitor fuel security, to allow the Australian Government to develop policies to prevent or prepare for interruptions to fuel supply

- assist the Government to give effect to Australia’s obligations under the Agreement on an International Energy Program (and any other agreements relating to energy security) and

- facilitate the publication of information relating to Australia’s petroleum and other fuel markets.

Reporting scheme coverage

The reporting scheme will include essentially all petroleum products that have a fuel use, as well as some non-petroleum fuels. Clause 5 sets out a definition for ‘covered products’ that includes natural gas, petroleum gas, liquid fuels, greases, lubricants and bitumen, as well as biofuels and hydrogen. The definition also includes the ability for other fuels or fuel-related products to be added by legislative rules.

Clause 5 also provides a definition for ‘covered activities’, which are essentially any commercial-type dealing relating to covered products: producing, refining, trade, wholesaling or stockholding. Other activities may be prescribed by the rules.

Clause 8 provides that the new law will apply to the offshore areas of the states and territories of Australia. The offshore areas are those regulated by the Offshore Petroleum and Greenhouse Gas Storage Act 2006—generally the area between a line three nautical miles seaward from the territorial sea baseline, and the edge of the continental shelf.[35] This is an important provision, as the vast majority of Australia’s petroleum is produced in offshore areas such as the North West Shelf and Bass Strait.[36] No provision seems be made to apply the new law to the Joint Petroleum Development Area (JPDA) between Australia and Timor-Leste; this is consistent with current petroleum reporting practice that regards petroleum from the JPDA as imported.[37]

Obligation to report

Clause 11 of the Reporting Bill imposes an obligation on a person, whose identity is to be prescribed by legislative rules, to make a report to the Secretary of the responsible Department (currently Environment and Energy), if a regulated entity (generally a corporation or trust, or an entity of an Australian territory) has undertaken a covered activity with a covered product. The Explanatory Memorandum says that ‘the person specified in the Rules will generally be the owner of the covered product. In most cases, the owner would also be the regulated entity’.[38] This has the general effect that businesses carrying on production, refining, wholesaling, imports, exports or stockholding of covered products will be obligated to make a report on their activities.

The report made under clause 11 must include ‘fuel information’ in relation to the covered activity or covered product. ‘Fuel information’ is defined broadly in clause 5 as any raw data, or any value-added information product, that relates to covered activities or the quantity, quality or characteristics of covered products; or any relevant metadata. It also includes contextual information relating to covered products (such as the location, control and ownership of covered products). However, the detailed requirements of the report that a person must make under clause 11 are to be prescribed by legislative rules, and are to be given in a form and manner approved by the Secretary of the Department.[39] The rules may specify different requirements for different products, activities or reporting persons.[40]

The Explanatory Memorandum notes that monthly reporting is envisioned, with reports expected to fall due 15 days after the end of a reporting period (expected to be a month),[41] which is linked to Australia’s requirements to provide information to the IEA about monthly closing stocks of net imports. The Explanatory Memorandum also raises the possibility that different products may have different reporting periods.

Subclause 11(2) imposes a maximum civil penalty of 250 penalty units ($45,000 as of June 2017[42]) for failing to give a report complying with the reporting requirements under clause 11. Clause 13 allows the legislative rules, or the Secretary (by written determination), to provide exceptions to the obligation to report.

The Explanatory Memorandum highlights that rules could be used to make general exceptions where the required information may be gathered efficiently through data-sharing. One example given is information relating to exports and imports of covered products, which may be efficiently gathered by using data collected by other agencies, such as the Department of Immigration and Border Protection and the Australian Bureau of Statistics.[43]

Clause 12 seeks to reinforce the constitutional grounds for the operation of the obligation to report. Under clause 5, the scheme’s coverage is restricted to regulated entities that are either:

(a) a constitutional corporation; or

(b) a trust, all of the trustees of which are constitutional corporations; or

(c) a body corporate that is incorporated in a Territory; or

(d) a body corporate that is taken to be registered in a Territory under section 119A of the Corporations Act 2001; or

(e) a trust, if the proper law of the trust and the law of the trust’s administration are the law of a Territory; or

(f) an entity, the core or routine activities of which are carried out in or in connection with a Territory.[44]

This definition of ‘regulated entities’ appears to be using the corporations power and the territories power to support the action of the scheme. Although it is likely that the majority of entities undertaking commercial activities with petroleum fuels would be constitutional corporations and therefore covered by this definition, it would nonetheless be possible for a non-regulated entity to undertake significant operations (such as trade or stockholding) of petroleum; an example could be a local or state government entity, or not-for-profit organisation directly importing significant quantities of diesel for the purposes of power generation. At present, it would seem that such cases would be relatively insignificant to the overall picture of Australian petroleum stocks, but it is possible, at least, that an entity that was not a constitutional corporation could be in control of a nationally significant amount of fuel.

Clause 12 invokes a number of additional constitutional heads of power to support and extend the scheme to persons beyond regulated entities. The Bill invokes the census and statistics power (subclause 12(3)), the trade and commerce power (subclause 12(6)), as well as the external affairs power (subclauses 12(4–5)). As the purpose of the Bill is ostensibly to return to compliance with the IEA agreement, it would seem that the external affairs power in particular provides strong constitutional grounds for action. The other listed powers would also appear to well support the action of the scheme.

Collection and publication of information

Clause 15 of the Reporting Bill expressly authorises the Secretary of the Department to collect fuel information, and clause 16 provides that the Secretary may publish statistical and non-statistical fuel information. However, information that is commercial-in-confidence (see further below) or likely to identify a person must not be published.

Protection of collected information

Part 4 establishes legal protection for fuel information gathered under the mandatory reporting scheme. A concept of ‘protected information’ is established by clause 5, which consists of fuel information that is personal information or commercial-in-confidence fuel information that is obtained (or derived from use, recording or disclosure of that information) under the proposed Act, the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 or the Taxation Administration Act 1953.[45]

‘Personal information’ has the same meaning as in the Privacy Act 1988,[46] while the meaning of ‘commercial-in-confidence’ is provided by clause 6:

Information is commercial-in-confidence if the Secretary is satisfied that:

(a) release of the information would cause competitive detriment to a person; and

(b) the information is not in the public domain; and

(c) the information is not required to be disclosed under another law of the Commonwealth, a State or a Territory; and

(d) the information is not readily discoverable.[47]

This definition is broadly consistent with the definition of ‘commercial-in-confidence’ in other Commonwealth legislation, such as section 15 of the Biosecurity Act 2015 and section 5 of the Australian Immunisation Register Act 2015.

Clause 6 gives the Secretary of the Department discretion to determine whether fuel information is protected information or not. That is, information is commercial-in-confidence if the Secretary is satisfied that it meets the criteria in clause 6. The Bill does not prescribe any formal arrangements for determining whether information is protected or not, nor does it require the Secretary to make a formal record that he or she has determined information to be commercial-in-confidence, and therefore protected. In the absence of any formal determination or record, the status of information as protected or not is unclear. Although the Explanatory Memorandum ‘envision[s] ... a process for appropriately identifying, labelling, storing and securing protected information’,[48] such processes are not required by the proposed Act to be implemented.

This is of particular importance because clause 20 creates an offence for the unauthorised recording, use or disclosure of the information by persons employed or otherwise engaged by the Department (‘entrusted persons’).[49] Such unauthorised recording, use or disclosure would be punishable by up to two years’ imprisonment—this is similar to provisions in other Commonwealth legislation dealing with personal or commercial-in-confidence information.[50]

Subclause 20(3) creates a defence against the commission of the offence if the entrusted person does not know that the information is commercial-in-confidence. However, unless the Secretary of the Department has determined (and made clear in writing) that information is commercial-in-confidence and therefore protected, it may be difficult for an entrusted person to know that information is commercial-in-confidence. Given that criminal penalties are attached to this provision, it might seem prudent to use a more robust process for the clear identification of commercial-in-confidence material. Despite this, the Bill provides that a defendant will be required to prove that they did not know the material was commercial-in-confidence.[51] However, the Explanatory Memorandum notes that this is ‘because of the difficulties that would arise if the entrusted person’s state of mind was a matter for the prosecution in establishing the offence’ and suggests that this approach consistent with the Attorney-General’s Department’s Guide to Framing Commonwealth Offences, Infringement Notices and Enforcement powers.[52] Notably, the Senate Scrutiny of Bills Committee did not raise any concerns in relation to this proposed provision.

Clauses 21–30 provide a range of circumstances where the use, recording or disclosure of protected information is permitted, including:

- by an entrusted person in the exercise of his or her functions or duties (clause 21)

- in relation to authorised publication (clause 22)

- to the Minister or their staff (clause 23)

- to, or with the consent of, the person to whom the information relates (clauses 25, 27 and 28)

- to a court or tribunal (clause 29)

- to a Commonwealth, state or territory department, agency or police force for the purposes of law enforcement (clause 30) and

- to the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission; the Australian Taxation Office; approved agencies of Commonwealth, state and territory governments and the International Energy Agency (in statistical form only) (clause 24).

Clause 31 permits Australian Border Force officials to disclose fuel information protected by the Australian Border Force Act 2015 to the Secretary of the Department of the Environment and Energy, or an entrusted person under this regime, for the purposes of the mandatory fuel reporting scheme, which would otherwise be an offence under that Act.[53]

Enforcement of obligation to report

Part 5 of the Bill deals with enforcing the obligation to report fuel information to the Secretary that was created by clause 11. This part of the Bill uses the standard provisions for compliance monitoring that are provided by Part 2 of the Regulatory Powers (Standard Provisions) Act 2014 (the Regulatory Powers Act), and enforcement provisions from Parts 4 and 5 of that Act.[54]

Clause 33 of the Bill applies the monitoring powers in Part 2 of the Regulatory Powers Act to information given under clause 11. This means, for example, that duly authorised persons[55] may enter premises either with a warrant or the consent of the occupier of the premises, to establish whether the obligation to report in clause 11 is being complied with.[56] Other monitoring powers under the Regulatory Powers Act include powers to search the premises and its contents (including documents and electronic equipment); to examine, take measurements or conduct tests of anything on the premises; secure electronic equipment for the purpose of expert examination; and to secure evidence.[57] As noted earlier, the Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills was concerned that the Reporting Bill would authorise unduly broad categories of people to exercise these coercive powers.

Subclause 33(3) extends Part 2 of the Regulatory Powers Act to each of the offshore areas.

Clause 35 applies the civil penalty provisions in Part 4 of the Regulatory Powers Act to the obligation to report, enabling the Secretary to apply to a relevant court to obtain a civil penalty order for failing to comply with the obligation to report. This also means that a body corporate could be fined up to five times the penalty amount specified in clause 11.[58] As of June 2017, this amount would be $225,000.

Clause 36 applies the infringement notice provisions in Part 5 of the Regulatory Powers Act, providing the Secretary with the ability to issue infringement notices for failure to report under clause 11. Infringement notices can be used to avoid court proceedings, where parties who are alleged to have contravened penalty provisions may discharge liability for the alleged contravention without admitting guilt or liability, in exchange for a particular penalty amount.[59] For a body corporate, this amount would be 50 penalty units ($9,000 at June 2017).[60] For an individual, the amount would be 12 penalty units ($2,160 at June 2017).

Part 6 of the Bill deals with miscellaneous matters:

- clause 38 imposes liability for offences committed by trusts onto the trustee(s)

- clause 39 allows the Secretary to delegate most of their functions under the proposed Act to Senior Executive Service (SES) employees or acting SES employees

- clause 40 requires that a review of the proposed Act must be conducted three years after the commencement of the Act, and that the Minister must table the report of that review in the Parliament no later than 15 sitting days after receiving the report and

- clause 41 provides that the Minister may make legislative rules regarding the proposed Act.

Petroleum and Other Fuels Reporting (Consequential Amendments and Transitional Provisions) Bill 2017

The Consequential Amendments Bill makes amendments to other legislation to facilitate the operation of the mandatory reporting scheme, principally by allowing the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission and the Australian Taxation Office to provide protected information to the Department of the Environment and Energy for the purposes of administering the mandatory fuel reporting scheme. These amendments would enable data-sharing as envisioned in the Reporting Bill. The Consequential Amendments Bill also clarifies when certain provisions of the Reporting Bill would come into operation.

Section 95ZP of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 contains an offence, punishable by up to two years imprisonment, for the disclosure of protected information by entrusted persons under that Act.

Item 1 of the Consequential Amendments Bill amends the Competition and Consumer Act 2010, inserting a new section 95ZPA, which permits persons entrusted with protected information under that Act to disclose such protected information to the Energy Department (currently the Department of Environment and Energy), as long as such disclosure is for the purpose of the mandatory fuel reporting scheme. The Chairperson of the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (or his or her delegate[61]) is in charge of authorising (in writing) entrusted persons to disclose protected information, and for determining conditions for the disclosure of such information.

Item 2 of the Consequential Amendments Bill amends the Taxation Administration Act 1953 to insert a new provision to allow taxation officials to disclose confidential taxpayer information to the Secretary of the Department for the purposes of the administering the fuel reporting scheme.[62]

Item 3 provides that the obligation to report fuel

information will apply to covered activities that occur from the later of 1 January

2018 and the day the scheme’s legislative rules commence. Items 4–7 clarify

that certain provisions in the Reporting Bill relating to publication and

disclosure of fuel information apply from the commencement of the new law, even

if the protected fuel information was obtained before (or after) the

commencement of the new law.

[1]. Agreement on an International Energy Program, done in Paris on 18 November 1974, [1979] ATS 7 (entered into force for Australia 27 May 1979).

[2]. AF Alhajji, ‘The 1973 oil embargo: its history, motives and consequences’, Oil and Gas Journal, 103(17), 2 May 2005, p. 24, ProQuest database.

[3]. International Energy Agency (IEA), ‘History’, IEA website.

[4]. Agreement on an International Energy Program, op. cit., article 2.

[5]. Data source: British Petroleum (BP), BP statistical review of world energy June 2016, BP, London, June 2016.

[6]. Department of the Environment and Energy (DEE), ‘IEA international energy program treaty’, DEE website.

[7]. IEA, ‘Closing oil stock levels in days of net imports’, IEA website, 14 June 2017.

[8]. National Roads and Motorists’ Association (NRMA), ‘Sustainable transport: Australia’s liquid fuel security’, NRMA website; J Blackburn, Australia’s liquid fuel security, NRMA, Sydney, 28 February 2013.

[9]. J Chong, ‘Melbourne airport hit by fuel shortage’, Australian Aviation, 22 January 2015; S Clark, ‘Fuel shortage at Melbourne Airport could force flight delays, diversions’, ABC News, 25 November 2016.

[10]. Australian Associated Press (AAP), ‘Victorian storms disrupt diesel supply’, News.com.au website, 7 December 2012.

[11]. DEE, Consultation paper: mandatory reporting of petroleum statistics, Canberra, September 2016, pp. 8–10.

[12]. A St John, ‘Mining and resources changes’, Budget review 2013–14, Research paper series, 2012–13, Parliamentary Library, Canberra, 2013.

[13]. Department of Resources, Energy and Tourism (RET), ‘Mandatory petroleum data reporting’, RET website, archived version from 6 September 2013.

[14]. Senate Standing Committee on Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport, Australia's transport energy resilience and sustainability, The Senate, Canberra, June 2015, p. 16.

[15]. Ibid.

[16]. Ibid., p. ix.

[17]. Australian Government, ‘Part 2: expense measures’, Budget measures: budget paper no. 2: 2016–17, p. 128.

[18]. DEE, ‘IEA international energy program treaty’, DEE website.

[19]. Australian Government, Australian Government response to the Senate Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport References Committee report: Australia’s transport energy resilience and sustainability, Canberra, November 2016.

[20]. Ibid; Department of Industry and Science, Energy white paper, DIS, Canberra, April 2015.

[21]. DEE, ‘Mandatory reporting of petroleum statistics: public consultation’, DEE website, 28 October 2016.

[22]. P Fairclough (Chevron Australia), Submission to the DEE, Public consultation into the mandatory reporting of petroleum statistics, 6 December 2016; Australian Petroleum Production and Exploration Association (APPEA), Submission to the DEE, Public consultation into the mandatory reporting of petroleum statistics, October 2016.

[23]. Australian Institute of Petroleum, Submission to the DEE, Public consultation into the mandatory reporting of petroleum statistics, 27 October 2016; M Bradley (CEO, Australian Automobile Association), Submission to the DEE, Public consultation into the mandatory reporting of petroleum statistics, 28 October 2016.

[24]. DEE, ‘Targeted consultation on biofuels, oils, lubricants, greases, waxes, solvents and petroleum coke’, DEE website.

[25]. Senate Standing Committee for the Selection of Bills, Report, 6, 2017, The Senate, 15 June 2017.

[26]. Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills, Scrutiny digest, 5, 2017, The Senate, 10 May 2017, pp. 46–48.

[27]. Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills, Scrutiny digest, 6, 2017, The Senate, 14 June 2017, p. 134.

[28]. Ibid., pp. 135–136.

[29]. Ibid., p. 139.

[30]. Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills, Scrutiny digest, 5, 2017, op. cit., p. 49.

[31]. Senate Standing Committee on Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport, Australia's transport energy resilience and sustainability, The Senate, Canberra, June 2015; Australian Greens, ‘Additional comments’, Senate Standing Committee on Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport, Australia's transport energy resilience and sustainability, The Senate, Canberra, June 2015.

[32]. Explanatory Memorandum, Petroleum and Other Fuels Reporting Bill 2017 [and] Petroleum and Other Fuels Reporting (Consequential Amendments and Transitional Provisions) Bill 2017, p. 3.

[33]. The Statement of Compatibility with Human Rights can be found at page 4 of the Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill.

[34]. Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights, Human rights scrutiny report, 4, 2017, 9 May 2017, p. 74.

[35]. Offshore Petroleum and Greenhouse Gas Storage Act 2006, sections 5, 6 and 8. For further information on maritime boundaries, see Geoscience Australia (GA), ‘Maritime boundary definitions’, GA website.

[36]. See GA, ‘Oil’, GA website, 2016.

[37]. Department of Environment and Energy (DEE), Australian petroleum statistics, issue 247, DEE, Canberra, February 2017, p. 27.

[38]. Explanatory Memorandum, Petroleum and Other Fuels Reporting Bill 2017 [and] Petroleum and Other Fuels Reporting (Consequential Amendments and Transitional Provisions) Bill 2017, p. 11.

[39]. Reporting Bill, paragraph 11(4)(b) and subclause 11(6).

[40]. Reporting Bill, subclause 11(5).

[41]. Explanatory Memorandum, op. cit., p. 18.

[42]. Crimes Act 1914, section 4AA. The Crimes Amendment (Penalty Unit) Act 2017 will increase the value of a penalty unit to $210 from 1 July 2017. From that date the maximum penalty will be $52,500.

[43]. Explanatory Memorandum, op. cit., p. 19.

[44]. Reporting Bill, clause 5.

[45]. Reporting Bill, clause 5.

[46]. Ibid., clause 5. See subsection 6(1) of the Privacy Act 1988, where ‘personal information’ is defined to mean ‘information or an opinion about an identified individual, or an individual who is reasonably identifiable’.

[47]. Reporting Bill, clause 6.

[48]. Explanatory Memorandum, op. cit., p. 23.

[49]. The definition of ‘entrusted persons’ is set out in clause 5 of the Reporting Bill.

[50]. For example, see Census and Statistics Act 1905, section 19; Agricultural and Veterinary Chemicals Code Act 1994, section 162.

[51]. See note after subsection 20(3).

[52]. Explanatory Memorandum, op. cit., p. 23. See also Attorney-General's Department (AGD), A guide to framing Commonwealth offences, AGD, Canberra, September 2011 edition, pp. 50–52.

[53]. Australian Border Force Act 2015, section 42.

[54]. Regulatory Powers (Standard Provisions) Act 2014. For further information on the Regulatory Powers Act, see C Raymond, Regulatory Powers (Standardisation Reform) Bill 2016, Bills digest, 42, 2016–17, Parliamentary Library, Canberra, 22 November 2016.

[55]. Clause 34 provides for the appointment of authorised persons by the Secretary.

[56]. Regulatory Powers Act, section 18.

[57]. Ibid., sections 19–22.

[58]. Ibid., paragraph 82(5)(a). As set out at footnote 42, from 1 July 2017 the maximum penalty will be $262,500.

[59]. Ibid., section 107.

[60]. Subsection 104(2) of the Regulatory Powers Act provides that unless provided otherwise, the infringement notice amount must be the lesser of one-fifth of the maximum penalty that a court could impose and 12 penalty units for an individual or 60 penalty units for a body corporate.

[61]. Proposed subsection 95ZPA(4) empowers the Chairperson to delegate his or her powers under the proposed section to another member of the Commission or an SES employee or acting SES employee of the Commission.

[62]. Consequential Amendments Bill, Schedule 1, item 2; Taxation Administration Act 1953, Schedule 1, section 355–65.

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

© Commonwealth of Australia

![]()

Creative Commons

With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, and to the extent that copyright subsists in a third party, this publication, its logo and front page design are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia licence.

In essence, you are free to copy and communicate this work in its current form for all non-commercial purposes, as long as you attribute the work to the author and abide by the other licence terms. The work cannot be adapted or modified in any way. Content from this publication should be attributed in the following way: Author(s), Title of publication, Series Name and No, Publisher, Date.

To the extent that copyright subsists in third party quotes it remains with the original owner and permission may be required to reuse the material.

Inquiries regarding the licence and any use of the publication are welcome to webmanager@aph.gov.au.

Disclaimer: Bills Digests are prepared to support the work of the Australian Parliament. They are produced under time and resource constraints and aim to be available in time for debate in the Chambers. The views expressed in Bills Digests do not reflect an official position of the Australian Parliamentary Library, nor do they constitute professional legal opinion. Bills Digests reflect the relevant legislation as introduced and do not canvass subsequent amendments or developments. Other sources should be consulted to determine the official status of the Bill.

Any concerns or complaints should be directed to the Parliamentary Librarian. Parliamentary Library staff are available to discuss the contents of publications with Senators and Members and their staff. To access this service, clients may contact the author or the Library‘s Central Enquiry Point for referral.

Australian Parliamentary Library Bills Digests

Australian Parliamentary Library Bills Digests