- Bills and Legislation wcag

- Tariff ProposalsBills DigestsBrowse Bills Digests Ordering Printed BillsBudget and Financial LegislationLegislative Instruments

Treasury Laws Amendment (Personal Income Tax Plan) Bill 2018

PDF version [361KB]

Phillip Hawkins

Economics Section

15

June 2018

Date introduced: 9

May 2018

House: House of

Representatives

Portfolio: Treasury

Commencement: Schedule

1, Parts 1 and 2 and Schedule 2 Parts 1 and 2, commence on the first 1 January,

1 April, 1 July or 1 October to occur after Royal Assent.

Schedule 1, Part 3 and Schedule 2, Part 3, Division 1

commence on 1 July 2024.

Schedule 2, Part 3, Division 2 commences on 1 July

2026.

Links: The links to the Bill,

its Explanatory Memorandum and second reading speech can be found on the

Bill’s home page, or through the Australian

Parliament website.

When Bills have been passed and have received Royal Assent, they

become Acts, which can be found at the Federal

Register of Legislation website.

All hyperlinks in this Bills Digest are correct as at June 2018.

The Bills Digest at a glance

Structure of

the Bill

Background

Committee

consideration

Policy

position of non-government parties/independents

Financial

implications

Statement of

Compatibility with Human Rights

Key issues

Key

provisions

The Bills Digest at a glance

The Government announced its Personal

Income Tax Plan (PITP) in the 2018–19 Budget. The PITP reduces personal income

taxes over the next seven years through a combination of changes to tax offsets

for low and middle income earners and changes in income tax thresholds. The

changes will be implemented over three steps, commencing in 2018–19, 2022–23

and 2024–25. The 2018–19 changes are targeted at low and medium income earners,

with the changes in 2022–23 and

2024–25 applying to individuals on higher taxable incomes.

The Treasury Laws Amendment (Personal Income Tax Plan) Bill 2018 (the Bill) seeks to implement all components of the PITP. The PITP will be implemented in three steps, commencing in the 2018–19, 2022–23 and 2024–25 income years.

- Step

one in 2018–19; introduces the new Low and Middle Income Tax Offset (LAMITO)

– a

non-refundable tax offset of up to $530 per annum for individuals earning up to $125,333:- the LAMITO will only apply in the 2018–19, 2019–20, 2020–21 and 2021–22 income years

- from 2022–23 subsequent changes to income tax thresholds will ‘lock-in’ these tax reductions for these individuals

- the top income tax threshold for the 32.5 per cent tax rate will also be increased from $87,000 to $90,000 from 2018–19.

- Step two commencing in 2022–23; increases the maximum rate of the existing Low-Income Tax Offset (LITO) from $445 to $645 per annum. The top income threshold for the 32.5 per cent rate will be increased from $90,000 to $120,000 and the top income threshold for the 19 per cent marginal rate will increase from $37,000 to $41,000 and

- Step three commencing in 2024–25 will extend the 32.5 per cent tax rate up to taxable income of $200,000, abolishing the 37 per cent marginal tax rate entirely. The 45 per cent marginal tax rate will be retained, meaning income in excess of $200,000 will be taxed at 45 per cent, as is currently the case for income in excess of $180,000.

The Government has, to date, committed to pass all steps of the PITP with this Bill. However, the Opposition and other non-Government parties have stated that they would like to consider the components of the Bill separately; having indicated that they support the earlier stages of the PITP for lower and middle income earners whilst not yet confirming their support for the further changes.

The legal provisions of this Bill are relatively straight-forward, but there are issues of policy that are likely to be debated in the Senate. Some of the key issues discussed in this Bills Digest include:

- the distributional impacts of the PITP; that is, what effect it has on income tax paid across different income levels and

- the financial impact of the separate components of the PITP and particularly the impacts beyond the forward estimates period (when the second and third steps of the PITP would be implemented).

Structure of the Bill

The Bill consists of two schedules:

- Schedule 1 amends the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (ITAA97) to introduce a new low and middle income tax offset (LAMITO) and to amend the existing low-income tax offset (LITO). The Schedule also makes consequential amendments to other legislation to implement these changes

- Parts 1 and 2 of Schedule 2 amend the Income Tax Rates Act 1986 (Rates Act) to enact changes to personal income tax thresholds and

- Part 3 of Schedule 2 amends the Rates Act to subsequently repeal the new personal income tax thresholds as they are superseded by later changes.

Background

As stated above, the PITP is being delivered through a combination of tax offsets for low and middle income earners and changes in tax thresholds. The Treasurer Scott Morrison stated in his second reading speech that the first step provides permanent tax relief to low and middle income earners, step two is intended to return bracket creep[1] to workers and step three, by abolishing the 37 per cent marginal tax rate, is intended to make personal income tax rates simpler and flatter.[2]

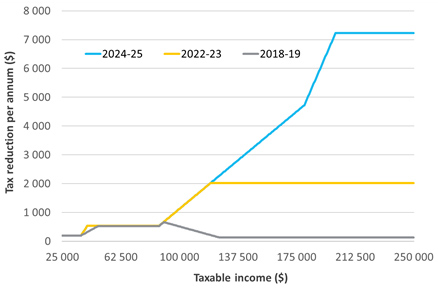

As Figure 1 shows, the first step of tax changes primarily targets individuals with taxable income less than $120,000, the second step provides further tax reductions to those with taxable income over $90,000 and the third stage reduces taxes for those with a taxable income over $120,000.

Figure 1: Combined impact of PITP changes (tax reduction per annum ($) by taxable income in 2018–19, 2022–23 and 2024–25)

Source: Parliamentary Library analysis based on the Billthe Bill.

Why is the Government utilising this approach?

Utilising tax offsets to provide most of the income tax reductions in 2018–19 means that the initial tax cuts can be targeted to low and middle income earners. Tax offsets can be limited to taxpayers at particular taxable income levels and phased out for higher income earners.

In contrast, changes in income tax thresholds cannot be targeted in the same way. Australia’s progressive tax system applies higher marginal tax rates to taxable income above particular income thresholds (zero for the first $18,200, 19 per cent between $18,200 and $37,000 and so on). This means that lifting an income tax threshold reduces the amount of tax paid by anyone with taxable income above that threshold. For example, increasing the tax threshold for the 32.5 per cent marginal tax rate from $87,000 to $90,000 benefits all individuals with taxable income over $87,000, not just those earning between $87,000 and $90,000. Anyone with taxable income above $87,000 would pay 32.5 per cent on any taxable income between $87,000 and $90,000 rather than the current 37 per cent.

Tax Offsets

What is a tax offset?In order to understand the Government’s PITP it is important to understand tax offsets and how they differ from tax deductions. Both deductions and offsets are ultimately used to reduce a taxpayer’s tax liability, but they operate differently:

The following is a simplified example (it ignores the Medicare levy): An individual has assessable income of $100,000, work-related deductions of $30,000 and non-refundable tax offsets of $10,000:[3]

Given that the Australian Tax Office (ATO) collects personal income tax throughout the year (income tax withholding), and deductions and offsets are effectively applied when the ATO processes a tax return (on assessment), an individual may be entitled to a refund of tax paid throughout the year. |

Low and middle income tax offset (LAMITO)

In the 2018–19 income year a new Low and Middle Income Tax Offset (LAMITO) will be introduced. The LAMITO is a non-refundable tax offset of up to $530 per annum for resident taxpayers with a taxable income of up to $125,333. It will be applied as a lump-sum amount on assessment. The LAMITO will commence in the 2018–19 income tax year and will be in place for four years until 2021–22 (at which time other tax changes will effectively ‘lock-in’ these tax cuts).

LAMITO will provide the following tax benefit:[4]

- individuals earning up to $37,000 will receive a LAMITO amount of up to $200 per annum[5]

- individuals earning more than $37,000 but less than $48,000 will have their LAMITO amount increased from $200, by three cents in the dollar, to a maximum rate of $530

- individuals earning between $48,000 and $90,000 will receive the maximum value of LAMITO of $530 and

- individuals earning more than $90,000 will have their LAMITO amount reduced by 1.5 cents in the dollar until it phases out entirely for incomes of $125,333 and above.

LAMITO is provided in addition to the existing Low-Income

Tax Offset (LITO) which provides an offset of up to $445 for individuals

earning less than $37,000, and reduces by 1.5 cents in the dollar for every

dollar over $37,000 until it phases out entirely for incomes over $66,667.

Figure 2 illustrates the combined amount of LAMITO and LITO available for the

2018–19, 2019–20,

2020–21 and 2021–22 income years.

Figure 2: LAMITO and LITO for the 2018–19, 2019–20, 2020–21 and 2021–22 income years

Source: Parliamentary Library analysis based on the Bill and ATO website.

Low-income tax offset

In the 2022–23 income year the LAMITO will be rolled into the existing LITO and the LITO will be increased from $445 to $645 per year. The new LITO, as illustrated in Figure 3, will provide the following tax offset amount:

- individuals earning up to $37,000 will receive a LITO amount of up to $645 (equal to the combined amount of LITO and LAMITO in previous years)

- individuals earning between $37,000 and $41,000 will have the new LITO amount reduced by 6.5 cents in the dollar for each dollar of income above $37,000 until their income reaches $41,000 and

- individuals earning over $41,000 will have their LITO amount reduced further by 1.5 cents in the dollar until it phases out entirely for individuals earning more than $66,667.[6]

There are no further proposed changes to these tax offsets in the third step commencing from the 2024–25 income year.

Figure 3: Maximum LITO amount from 2022–23 onwards

Source: Parliamentary Library analysis based on the Bill.

Changes to tax thresholds

The PITP also makes changes to income tax thresholds in three steps in 2018–19, 2022–23 and 2024–25. These changes predominately affect middle and high income earners:

- in the 2018–19 income year the threshold for the 32.5 per cent marginal tax rate will increase from $87,000 to $90,000[7]

- in the 2022–23 income year the threshold for the 32.5 per cent marginal tax rate will increase from $90,000 to $120,000 and the threshold for the 19 per cent rate will increase from $37,000 to $41,000 [8] and

- the final change in 2024–25 income year will abolish the 37 per cent tax bracket entirely and extend the marginal tax rate of 32.5 per cent to all taxable incomes between $41,000 and $200,000.[9]

As changes in income tax thresholds will change the amount that the ATO withholds from individuals’ income, these tax cuts will effectively be provided throughout the year instead of on assessment (as with the tax offsets).

Committee consideration

Senate Standing Committees on Economics

The Bill has been referred by the Senate to the Economics Legislation Committee for inquiry and report by 18 June 2018. Details are available at the inquiry homepage.[10]

Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills

At the time of writing the Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills had made no comment on the Bill.

Policy position of non-government parties/independents

Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party (ALP) has stated that it supports the first step of the PITP and has called for the Bill to be split to allow the passage of those changes. In his second reading speech, the Shadow Treasurer, Chris Bowen stated:

Firstly, regarding tax relief on 1 July 2018, as I made clear on budget night in the very first post-budget statements that I made on behalf of the Labor Party, we support the 2018 tax cuts. They should be implemented. The government could pass this legislation through this House today and, as soon as the Senate resumes, could pass it through the other place with our full support. The Greens don't support it; that's a matter for them. But the Labor Party, the National Party and the Liberal Party voting together would give you the numbers in both houses. It can be done. But, to do that, the government should split this bill. It should split it in this House, and it should also split it in the Senate and allow the parliament to take a detailed and considered position on each of the three tranches.[11]

The ALP has also announced that from the 2019–20 income years it would make the LAMITO permanent and increase it to a maximum amount of $928 per year, $398 more than the maximum amount under the Government’s proposal.[12] The ALP moved an amendment to the Bill in the House of Representatives to implement these changes; however, the amendment was unsuccessful.[13] To date, the ALP has not confirmed whether it supports the second tranche of reforms.

The Australian Greens

The Australian Greens have indicated that they do not support the Bill. In his second reading speech Adam Bandt MP stated:

I won't be supporting this bill. I want to see services, not tax cuts. Let's change the debate and get back to a basic principle: tax is not a dirty word. The question is: what do we spend our tax on? And, if we can spend our tax on universal schools, health care and making sure that people are not out of pocket when they send their kids to schools or when they go to the GP, the Australian people will thank us for it. It's a much better use of money than putting $10 in people's pockets, only for them to find it disappears the moment that it is put there.[14]

Other non-government parties and independents

One Nation and the Centre Alliance have reportedly called on the Government to split the Bill to consider each of the three steps separately.[15]

Senator Storer has reportedly stated that he will not support the PITP in full, but would support the introduction of the low and middle income tax offset on the basis that it does not have an ongoing cost to the Budget.[16]

Financial implications

According to the Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill the PITP is estimated to reduce revenue by $13.4 billion over the budget forward estimates period. A break-down of this estimate over each year of the forward estimates period is included in Table 1.

Table 1: Financial impact of the PITP (forward estimates period) ($m)

| 2017–18 | 2018–19 | 2019–20 | 2020–21 | 2021–22 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | -360 | -4,120 | -4,420 | -4,500 |

Source: Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill, p. 3

The Bill is expected to have a more significant negative

financial impact beyond the forward estimates period as the second and third

steps in the PITP commence in 2022–23 and 2024–25. The Government has confirmed

that the estimated cost of the proposal over the ten years to

2027–28 will be $144 billion with just over $100 billion relating to step

one and two of the plan and the remainder from step three of the plan:

Of the $143 billion or thereabouts—we've been saying roughly $140 billion—just over $100 billion is actually going to steps 1 and 2 of that program, which is targeted towards low- and middle-income earners over that period. That's what steps 1 and 2 are costing, and the total cost of step 3 over the medium term is just over $143 billion, at $143.95 billion.[17]

Further discussion of the financial impacts of each stage of the PITP is discussed under the heading Key Issues below.

Statement of Compatibility with Human Rights

As required under Part 3 of the Human Rights (Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011 (Cth), the Government has assessed the Bill’s compatibility with the human rights and freedoms recognised or declared in the international instruments listed in section 3 of that Act. The Government considers that the Bill is compatible.[18]

Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights

At the time of writing the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights had made no comments on the Bill.

Key issues

The key issues with this Bill relate to matters of policy debate, namely the distributional effects of the tax cut (that is, who benefits from the PITP) and the cost of each stage of the PITP.

Distributional impact of the PITP

As discussed, the PITP is targeted so that the benefits initially target those on low and middle taxable incomes, with step two and step three providing additional tax reductions for those at higher taxable income levels. Table 1 shows the estimated tax reduction for selected taxable incomes from each stage of the PITP. The highest tax cut available under the PITP is $7,225 per annum which is the amount of tax reduction received by any person with taxable income over $200,000 from 2024–25 onwards.

Table 2: Reduction in tax payable in each stage of the PITP by selected taxable income levels

| Reduction in tax payable ($ per annum) | |||

| Taxable Income | 2018–19 | 2022–23 | 2024–25 |

| 30,000 | 200 | 200 | 200 |

| 50,000 | 530 | 540 | 540 |

| 70,000 | 530 | 540 | 540 |

| 90,000 | 665 | 675 | 675 |

| 110,000 | 365 | 1,575 | 1,575 |

| 130,000 | 135 | 2,025 | 2,475 |

| 150,000 | 135 | 2,025 | 3,375 |

| 180,000 | 135 | 2,025 | 4,725 |

| 200,000+ | 135 | 2,025 | 7,225 |

Source: Parliamentary Library analysis based on the Bill.

Commentary—distributional impact

A number of commentators have assessed the distributional impact of the PITP.

The Grattan Institute examined the effect of the plan and found that bracket creep will make the personal income tax system less progressive over time, as middle income earners bear the majority of the burden of bracket creep. The PITP does not significantly reduce the impact of this bracket creep on the progressivity of the tax system:

Taken as a whole, the Tax Plan will not unwind bracket creep’s gradual reduction of the progressivity of the tax system. Even with the Tax Plan, average tax rates are forecast to be higher for all taxpayers in 2027-28 – except for very high-income earners who aren’t much affected by bracket creep in the first place....

Once fully implemented, the Tax Plan won’t have much impact on the progressivity of the tax system. Overall, those on high incomes will pay a similar proportion of total tax revenues with or without the Tax Plan. But because of bracket creep in the meantime, high-income earners will be paying a lower proportion of income tax than today.[19]

NATSEM also examined the PITP and concluded that no one would be worse off under the proposed plan. Middle income earners would benefit most from the first step of the plan, with those on an average full-time salary of $83,000 receiving the maximum tax offset of $530. Subsequent changes would primarily benefit higher income earners:

Generally, no one would be worse off due to the budget measures focusing on tax cuts. Middle income earners benefit the most in the financial year 2018-19 thanks to the introduction of the low and middle income tax offset and an increase in tax threshold. Those earning an average full-time salary of $83,000 per year would get a maximum tax offset of $530 back in the upcoming financial year. However, in the long term, individuals with high incomes will benefit the most once the tax reform is fully implemented. For example, a couple both earning twice the average full-time salary can expect an extra $13,000 in 2024-25. [20]

Phillips, Webster and Gray of the Australian National University’s (ANU) Centre for Social Research and Methods (CSRM) undertook detailed modelling of the PITP and also found that the tax cuts do not fully offset the impact of bracket creep for low, middle and high income families with average tax rates expected to continue to increase over the next decade (albeit by less than they would without the PITP). It also found that the latter steps of the PITP are more beneficial for higher income households in both absolute dollar terms and per cent terms. However, it acknowledges that these households pay a larger proportion of total tax:

In dollar terms ... high income households receive much more significant tax cuts. The overall tax cuts increase disposable income by around 1.5 per cent and this varies from just 0.2 per cent for low income households up to 2.2 per cent for high income households. The tax cuts are more significant for higher income households for a range of reasons including lower income households paying little or no tax, the more significant degree of bracket creep requiring compensation for high income households and the policy changes from 2022-23 that tend to be more beneficial to higher income individuals in both absolute dollars and per cent terms.[21]

Ernst and Young support the plan, arguing that changes in Australia’s tax and transfer system have targeted low income earners substantially but at the same time middle income earners have seen their tax burden increase while not qualifying for transfer payments:

The bulk of Australia’s personal tax and transfer payments changes have been very much focused on low income taxpayers. These taxpayers have benefited overwhelmingly from lower taxes and in fact taxpayers with taxable incomes under $18,000 pay no tax[22], and those with taxable incomes under $37,000 pay negligible tax.

This is consistent with Australia’s highly progressive tax system. But the tax and transfer payment benefits cut out at lower middle incomes and have meant that middle income taxpayers have not benefited materially. Their marginal taxes have continued to increase.

Taxpayers not eligible for transfer payments have seen increasing income taxes as a percentage of income. Such burdens have fallen particularly on single income taxpayers without children, dual income taxpayers without children and family taxpayers whose incomes fall outside the limits for the transfer payments.[23]

Share of income tax paid by wealthy individuals and households

A number of researchers have estimated the impact of the PITP on the share of income paid by taxpayers in different income quintiles as a way to assess the distributional impact of the changes. However, they have drawn different conclusions based in part on how they define these income quintiles.

Grattan Institute estimates are based on individuals who file tax-returns. They find that the share of personal income tax paid by the top 20 per cent of individuals will fall from 68.2 per cent in 2017–18 to 65.7 per cent in 2027–28 under the PITP.[24]

Deloitte’s estimates are based on the total adult population, rather than just individuals that file tax returns. Deloitte found that the share of personal income tax paid by the top 20 per cent of individuals by income would increase from 78.7 per cent in 2017–18 to 81.3 per cent in seven years’ time under the PITP.[25]

The CSRM at ANU estimated the impact based on household

income and found that the proportion of tax paid by the top 20 per cent of

households would fall from 61.2 per cent in

2017–18 to 58.3 per cent in seven years.[26]

Financial Impact of the PITP

The Opposition has requested further information on the cost of the PITP and its three separate steps over the medium term to ascertain the financial impact of each. This is because step two and three are implemented outside the forward estimates period (the timeframe over which costings are usually provided). Treasury Secretary John Fraser tabled additional information on the costs of the PITP to 2028–29 at Senate Estimates on 29 May 2018.[27] These estimates provide additional information on the cost of the three steps over the decade to 2028–29, but not on an annual basis as requested by the Opposition. Mr Fraser stated in Senate Estimates that:

... our confidence in specific years is not such that we feel comfortable providing those estimates.[28]

Estimates of the annual cost of the Government’s PITP on a year by year basis were provided by the Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) in response to a Question on Notice by Senator Chris Ketter.[29] These figures show that the annual cost of the PITP will be $24.6 billion in 2028–29. Further information from the PBO was released by the Australian Greens on 5 June 2018 which shows the costs of the different components on an annual basis. In 2028–29 the PBO’s estimated break-down of the $24.6 billion is as follows:

- $800 million for the components commencing on 1 July 2018–19

- $13.45 billion for the components commencing from 1 July 2022 and

- $10.35 billion for the components commencing from 1 July 2024.[30]

Key provisions

Schedule 1—Low and Middle Income Tax Offset and Low Income Tax Offset

Item 1 of Schedule 1 inserts a new Subdivision 61-D into the ITAA97 to introduce the LAMITO and make changes to the LITO.

LAMITO

The entitlement criteria for LAMITO in respect of individuals and beneficiaries of trusts that are individuals are outlined in proposed section 61-105. An individual is entitled to receive LAMITO:

- for the 2018–19, 2019–20, 2020–21 and 2021–22 income year

- if they are an Australian resident at any time during the income year and

- if they have a taxable income, or a share of the net income of a trust, which does not exceed $125,333 for the income year.

Proposed subsection 61-107(1) sets out, in a table, the amount of LAMITO that an individual is entitled to based on their taxable income or their share of net income in a trust.

Proposed subsection 61-107(2) applies a cap on the amount of LAMITO available for certain prescribed persons under Division 6AA of Part III of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (ITAA36).[31]

LITO

The entitlement criteria for the revised LITO in respect of individuals and beneficiaries of trusts that are individuals are outlined in proposed section 61-110. An individual is entitled to receive LITO

- for the 2022–23 income year and later income years

- if they are an Australian resident at any time during the income year and

- if they have a taxable income, or a share of the net income of a trust, which does not exceed $66,667 for the income year.

Proposed subsection 61-1115(1) sets out, in a table, the amount of LITO that an individual is entitled to based on their taxable income or their share of net income in a trust.

Proposed subsection 61-115(2) applies a cap on the amount of LAMITO available for certain prescribed persons (for example, minors and certain trustees) under Division 6AA of Part III of theITAA36.

Schedule 2

Parts 1 and 2—Personal income tax reform

Parts 1 and 2 of Schedule 2 repeal existing tax rates in the Rates Act and insert the new tax rates and thresholds that apply in each year of the personal income tax plan:

- item 2 inserts the new income tax rates and thresholds that apply to resident individuals

- item 5 inserts the new income tax rates and thresholds that apply to non-resident individuals and

- item 9 inserts the new income tax rates and thresholds that apply to working holiday makers.

Part 3—Later repeals

Part 3 of Schedule 2 amends the Rates Act to subsequently repeal the tables containing the new tax rates that apply under the PITP, as they are superseded by further changes. The personal income tax rate and threshold tables that apply in 2018–19, 2019–20, 2020–21 and 2021–22 would be repealed from 1 July 2024 and the income tax rate and threshold tables that apply in 2022–23 and 2023–24 are repealed from 1 July 2026.

Despite the repeal of the tables, item 25 states that the rates and thresholds in the repealed tables continue to apply to the relevant income years.

[1]. Bracket creep occurs when an individual’s average tax rate increases due to their income increasing over time while income tax thresholds stay the same. Source: Australian tax white paper.

[2]. S Morrison, ‘Second reading speech: Treasury Laws Amendment (Personal Income Tax Plan) Bill’, House of Representatives, Debates, 9 May 2018, p. 8.

[3]. Tax offsets may be non-refundable or refundable, the difference being that a non-refundable tax offset can only reduce the amount of tax that someone pays to zero in a financial year. Refundable tax offsets can reduce the amount of tax liability to an amount less than zero, which results in a refund.

[4]. Explanatory Memorandum, Treasury Laws Amendment (Personal Income Tax Plan) Bill 2018, p. 8.

[5]. Because LAMITO and LITO are non-refundable, the maximum amount of LAMITO and LITO that can be claimed will be limited to the person’s tax liability prior to applying the offset.

[6]. Explanatory Memorandum, Treasury Laws Amendment (Personal Income Tax Plan) Bill 2018, p. 9.

[7]. Ibid., p. 11.

[8]. Ibid., pp. 11–12.

[9]. Ibid., p. 13.

[10]. Senate Standing Committee on Economics, Treasury Laws Amendment (Personal Income Tax Plan) Bill 2018 [Provisions], The Senate, Canberra, 2018.

[11]. C Bowen ‘Second reading speech: Treasury Laws Amendment (Personal Income Tax Plan) Bill’, House of Representatives, Debates, 22 May 2018, p. 1.

[12]. B Shorten (Leader of the Opposition) and C Bowen (Shadow Treasurer), Tax refund for working Australians: bigger, better and fairer, media release, 10 May 2018.

[13]. C Bowen, ‘Treasury Laws Amendment (Personal Income Tax Plan) Bill 2018—amendments moved by the Opposition’, House of Representatives, 22 May 2018.

[14]. A Bandt ‘Second reading speech: Treasury Laws Amendment (Personal Income Tax Plan) Bill 2018', House of Representatives, Debates, 22 May 2018, p. 10.

[15]. J Kelly, ‘Split tax cut bill, senators warn PM’, The Australian, 14 May 2018, p. 1.

[16]. Nine News, ‘Crossbencher will not back full tax plan,’ 6 June 2018.

[17]. S Morrison, ‘Second reading speech: Treasury Laws Amendment (Personal Income Tax Plan) Bill 2018’, House of Representatives, Debates, 23 May 2018, p. 81.

[18]. The Statement of Compatibility with Human Rights can be found at page 23 of the Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill.

[19]. J Daley, D Wood and H Parsonage (Grattan Institute), Submission to the Senate Economics Legislation Committee, Inquiry into the Treasury Laws Amendment (Personal Income Tax Plan) Bill 2018, [submission no. 14], June 2018, p. 7.

[20]. National Centre for Social and Economic Modelling (NATSEM), ‘How does the Budget affect us?’, Brochure, NATSEM, May 2018, p. 4.

[21]. Professor M Gray (ANU), Submission to the Senate Economics Legislation Committee, Inquiry into the Treasury Laws Amendment (Personal Income Tax Plan) Bill 2018, [submission no. 3], 25 May 2018, pp. 10–11.

[22]. It is worth noting that all taxpayers get the benefit of the tax-free threshold for their first $18,000 of taxable income, albeit the benefit is proportionately higher for those individuals on lower taxable incomes.

[23]. Ernst & Young, Submission to the Senate Economics Legislation Committee, Inquiry into the Treasury Laws Amendment (Personal Income Tax Plan) Bill 2018, [submission no. 8], 28 May 2018, p. 2.

[24]. D Wood and J Daley (Grattan Institute), ‘Grattan modelling of the government’s Personal Income Tax Plan highlights costly cuts to taxes for high-income earners’, May 2018, pp. 1–4.

[25]. There are a number of sections of the adult population that do not have income from employment and may not have to file tax returns, including age pensioners, self-funded retirees, students and other individuals not in the labour force; J Gothe-Snape, ‘How much tax do the rich actually pay? It depends on how you do the numbers’, ABC News, 22 May 2018.

[26]. Ibid.

[27]. J Fraser, Tabled evidence to the Senate Economics Committee, 2018-19 Budget Estimates, 29 May 2018, p. 2.

[28]. J Fraser, Evidence to the Senate Economics Committee, 2018–19 Budget Estimates, 29 May 2018, p. 11.

[29]. J Wilkinson (Parliamentary Budget Officer), ‘Letter to Mr Mark Fitt, Committee Secretary Senate Economics Legislation and References Committees’, 5 June 2018.

[30]. M Grattan, ‘Greens release annual figures for income tax package’, The Conversation, 5 June 2018.

[31]. The existing Division 6AA of the ITAA36 acts to discourage income splitting by diverting income to children. Division 6AA applies the top marginal tax rate to “unearned income” of prescribed persons who are under the age of 18 at the end of the income year except for: a person who is in a full time occupation; is an incapacitated child in respect of whom a carer allowance or disability support pension was paid or would, but for eligibility tests, be payable; or is a double orphan or permanently disabled person, provided they are not dependent on a relative for support Source: Wolters Kluwer, Taxation Overview - Minors, Wolters Kluwer website, accessed 12 June 2018.

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

© Commonwealth of Australia

![]()

Creative Commons

With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, and to the extent that copyright subsists in a third party, this publication, its logo and front page design are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia licence.

In essence, you are free to copy and communicate this work in its current form for all non-commercial purposes, as long as you attribute the work to the author and abide by the other licence terms. The work cannot be adapted or modified in any way. Content from this publication should be attributed in the following way: Author(s), Title of publication, Series Name and No, Publisher, Date.

To the extent that copyright subsists in third party quotes it remains with the original owner and permission may be required to reuse the material.

Inquiries regarding the licence and any use of the publication are welcome to webmanager@aph.gov.au.

Disclaimer: Bills Digests are prepared to support the work of the Australian Parliament. They are produced under time and resource constraints and aim to be available in time for debate in the Chambers. The views expressed in Bills Digests do not reflect an official position of the Australian Parliamentary Library, nor do they constitute professional legal opinion. Bills Digests reflect the relevant legislation as introduced and do not canvass subsequent amendments or developments. Other sources should be consulted to determine the official status of the Bill.

Any concerns or complaints should be directed to the Parliamentary Librarian. Parliamentary Library staff are available to discuss the contents of publications with Senators and Members and their staff. To access this service, clients may contact the author or the Library’s Central Enquiry Point for referral.

Australian Parliamentary Library Bills Digests

Australian Parliamentary Library Bills Digests