James Cook University Law Review

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

James Cook University Law Review |

|

2022] JCULawRw 6

2022] JCULawRw 6  ; (2022) 28 James Cook University Law Review 91

; (2022) 28 James Cook University Law Review 91

A Dental Practitioner’s Pricky Predicament: To Tell Or Not To Tell?

Vy Phan

Abstract

Changes to national guidelines in 2018 allowing Australian dentists to practice with HIV have been met with complex ethical dilemmas, and the question of whether they have a duty to disclose their HIV status to patients has emerged. This paper explores the ethical concepts and principles of patient autonomy and in particular, the right to know a dentist’s HIV status, non-maleficence and potential harm that may arise from practitioner to patient HIV transmission and the concept of justice; what is fair for both the practitioner and the patient regarding HIV disclosure?

The paper includes discussions around sole disclosure by the dentist, mutual disclosure by both patient and dentist and the impact of HIV stigma on the community. Strategies to improve public health outcomes by reducing HIV stigma, analysis of the current duty of disclosure regulations around health practitioners, and sexually active HIV-infected individuals in Australia, UK and the US will be deliberated. Comparisons will be made between the countries to evaluate whether any duty of disclosure laws should be introduced in Australia.

Australian national guidelines from the Communicable Disease Network Australia were amended in June 2018, to enable health care workers living with blood-borne viruses such as HIV to continue performing exposure-prone procedures, subject to a number of conditions.[1] This followed the UK’s decision to amend its guidelines in 2014 to allow NHS staff to continue to work in their respective health sectors even if they were HIV-positive, or infected with any other blood borne viruses.[2] This shift in regulation reflects advancing medical treatments in areas of blood borne viruses and acceptance of HIV-positive health professionals.

However, these changes also raise ethical issues amongst the public and, particularly, for dentists due to effects on patient autonomy, duty of disclosure to patients, their right to know of their dentist’s HIV status and the notion of non-maleficence, to ensure that patients are protected from potential harm via HIV transmission. The contrary arguments for mandatory disclosure of a dental practitioner’s HIV status consist of the negligible transmission rate, justice, patient disclosure and increasing HIV stigma. The consideration of whether mutual disclosure by both patient and dentist should be implemented and the duty of disclosure to sexual partners in Australia will also be discussed.

Lastly, comparisons and evaluations of duty of disclosure laws in the UK and the US will offer further insight into this complex matter.

II Guidelines

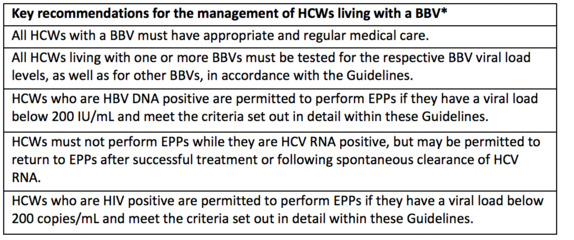

Australian health care workers, including dentists with blood borne viruses, are able to practise subject to a number of regulations including frequent testing, proper medical care and viral load that does not exceed a specified amount. Below is a table of the key recommendations for the management of dentists infected by blood borne viruses. [3]

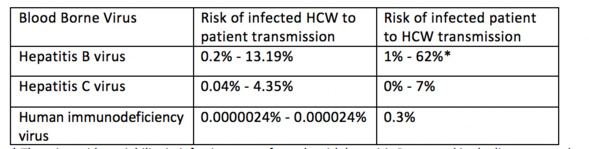

The second table provided below illustrates the risk of transmission from untreated health care practitioner to patient and untreated patient to practitioner.[4] It highlights how it would be practically impossible for a treated dentist with HIV to infect a patient given how low the rate of transmission is, even if a health care worker is not receiving treatment. Patients on the other hand have a far greater risk of infecting their health care worker.[5]

III Autonomy and Non-maleficence

Autonomy has become increasingly significant in health care practice as, fundamentally, patients should have the right to choose their own health care, health outcomes and health providers.[6] Choice correlates to the concept of individual autonomy which is often associated in ethical theories as good.[7] Respecting patients’ decisions enables health practitioners to recognise an individual’s moral status and ‘capacity for self-determination’.[8] Respecting autonomy also ensures that dentists are providing advice and education to patients, without persuading them to undertake certain treatments for their own gains or monetary benefits. This allows for a sustainable and healthy doctor-patient relationship.

On the contrary, acts of deception or lying performed by the dentist can create barriers to effective clinical care, are in violation of the Hippocratic Oath and the dentist’s moral duty to a patient.[9] This begs the question, should dentists therefore be morally responsible for disclosing their HIV infective status to patients? In a survey to health care workers about their views on HIV-positive health care workers conducted at the University of Kansas medical centre, almost 25% of respondents stated they would not want a HIV-positive surgeon operating on them and 15% did not want a HIV-positive technician performing an intravenous line on them.[10] Almost a third of respondents said they would not keep their trusted personal physician if they discovered that their physician was HIV-positive.[11] In an article featured in the AMA Journal of Ethics, Jay Jacobson identifies surgeons’ ethical obligations as honestly answering if patients were to enquire about their HIV status, just as they should when questioned about ‘training, experience, or complication rates’. [12] Given these above considerations and the statistics of health care workers not wanting to be treated by other health care workers with HIV, it would be reasonable for patients to be informed of their dentist’s HIV status to ensure their autonomous rights to health care.

Non-maleficence is the second principle of medical ethics literally meaning, ‘do no harm’.[13] Dental practitioners are obliged to avoid harming patients intentionally, protecting patients from harm and minimising potential risks.[14] In the United Kingdom, infected dental surgeons transmitting HIV to patients, could be ‘liable for inflicting grievous bodily harm contrary to s 20 of the Offences Against the Person Act 1861 (‘OAPA’), unless the patient was fully informed of the risks, and consented to them. This would inevitably require the disclosure of the dentist’s HIV status’.[15] Considering the above, it would seem crucial that patients are made aware of their dentist’s HIV status if there is any possibility of transmission to the patient so that harm and risks to the patient are mitigated. Undisclosed risk not only may cause harm to the patient but affects their autonomy, ability to consent and make informed treatment decisions.

A famous case in 1990 involves a Florida dentist called Dr Acer who infected six of his patients with AIDS.[16] One of his patients, Kimberley Bergalis, died in 1991, causing strict legislation to be implemented around health care workers with infective diseases.[17] Her father argued that ‘someone who has AIDS and continues to practice is nothing better than a murderer.’[18] This alarming tragedy highlights the potential dangers to the public from a dentist infected with HIV. Suspicions arose that Dr Acer may however, have deliberately attempted to infect his patients to make a bold statement about the ignorance of the public to how AIDS affects the homosexual community.[19] Other suspicions suggest Dr Acer just had poor infection control practices and sterilisation procedures.[20]

IV The Counter Arguments

However, since Dr Acer’s case highly active antiretroviral therapy (HARRT) has led to a significant decline in morbidity and mortality rates amongst patients infected with HIV.[21] The risk of transmission from a dentist to a patient is nowadays deemed negligible. Recent lookback procedures have not been able to show transmission of HIV from an infected health care worker to a patient: ‘The evidence now supports the view that Oral Health Care Professionals with HIV do not pose a risk of transmission to patients in the dental setting’,[22] demonstrating how individuals treated with HAART are at no risk to the general public.[23]

Given the strict guidelines that health practitioners need to abide by if infected by HIV, and the negligible chances of infecting patients, it seems that health practitioners with HIV are not a harmful risk to patients. If anything, dentists with HIV undergoing anti-retroviral therapy are more than capable of doing good by their patients and acting with beneficence through their skills and expertise. On the other hand, even though the risk of transmission of blood borne viruses from a patient to practitioner is much greater, dental practitioners still take this risk daily to ensure that the patient’s well-being is their first priority.

Justice is another fundamental ethical principle in health care, encompassing equality, fairness and equitable health outcomes.[24] To ensure patients with HIV are receiving fair and just treatment, anti-discrimination laws such as the Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth) make it illegal to discriminate against a person with HIV or a patient with HIV. [25] They should be entitled to the same treatment, provision of goods, employment, education and access to public facilities as any other person.[26] Dentists have an ethical obligation to treat all patients, regardless of whether they have a blood borne virus and whether they choose to truthfully disclose this or not.

The guide to Australian HIV laws and policies also explicitly state, ‘there are no criminal laws that specifically name non-disclosure of HIV status’ and ‘there is no longer a legal requirement to disclose HIV positive status before sex’.[27] Hence patients generally do not suffer any legal consequences if they decide not to advise their dentist that they have HIV. This puts dentists unnecessarily at risk as, if HIV infected patients do notify them, dentists can choose to take precautionary measures such as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP),[28] which can reduce the risk of infection by 90%, or, in some cases, post-exposure prophylaxis which can prevent HIV if taken correctly after an incident has occurred.[29]

The notion of justice should then be considered. Is it fair that dentists face these risks and patients have no duty of disclosure, whilst dentists are perceived as doing harm if they, in turn, do not disclose their status? It would seem not, especially when patients are not subject to similar expectations and requirements to have their HIV disease treated whereas dentists, as discussed earlier, must fall into what is practically a non-transmissible category to practice. The notion of justice should apply to all individuals, whether it be dentists or patients and a similar duty of disclosure should be required fairly by both parties, not just expected of one alone.

HIV stigma has been a grave and debilitating issue for many years in Australia, causing individuals with HIV to have compromised human rights, affecting their health and social outcomes.[30] Statistics from a survey done in 2011 determined that 77% believed ‘telling someone I have HIV is risky,’ 42% agreed with ‘I work hard to keep my HIV a secret’ and 40% agreed with ‘most people think that a person with HIV is disgusting.’[31] These alarming statistics show how many Australians feel ashamed about their HIV status based on societal views and expectations.

This highlights another significant flaw in expecting dentists alone to disclose their status as an ethical obligation as, in turn, dentists may feel discriminated against and part of the HIV stigma epidemic. Asking dentists to disclose their status to all patients also further emphasises that HIV is a negative and dangerous condition that should be drawn to the attention of others by everyone. Rather than trying to move away from HIV stigma in our population, if dentists alone are requested to disclose their status each time they treat a patient that will worsen what is already a less than ideal situation.

V Possible Solutions

After consideration of the above ethical issues, solutions to this dilemma need to encompass giving patients autonomy and acknowledging their right to know whether their dentist is HIV-positive but also, justly and fairly, allowing dentists to be aware of their patient’s HIV status as a legal requirement. This notion of mutual disclosure will enable both patients and dentists to feel comfortable about discussing their HIV status as it is expected from both parties and, in turn, possibly lessen the impact of HIV stigma. To further reduce this impact, individuals, including patients, should be more educated about the low risk of HIV transmission and the effective readily available treatments that could make the disease non-contagious.

Currently there are no legal requirements for either patient or health practitioner to disclose their HIV status or blood borne viruses of any kind. This not only poses risks to the dentist treating the patient but can also be harmful to the patient, as it can affect treatment outcomes, prescribing and assessing contra-indications if the patient does not truthfully disclose their HIV disease.

HIV can affect oral health quite detrimentally and informing a clinician first about the condition can ensure that they are monitoring for oral lesions such as oral hairy leukoplakia, Kaposi’s sarcoma, Non-hodgkin’s lymphoma, oral candidosis, oral ulceration and human periodontal diseases such as acute necrotising ulcerative gingivitis, which are at higher risk of occurring when one is infected with HIV.[32]

Oral conditions can also be caused by the different medications used to treat HIV which can include ‘lichenoid reactions, xerostomia (didanosine, indinavir), mucosal pigmentation (zidovudine), and taste disturbances (indinavir)’.[33] Awareness of the medications patients are taking for HIV enables dentists to give patients advice on the consequences of the disease for their oral health and how to prevent, treat and manage the conditions.

Hence, a legal requirement that patients disclose their HIV status not only allows dentists to take precautionary measures if they choose to do so, it also protects the patients and enables them to get better management of the oral side-effects of their HIV disease.

Formally legalising dentists’ duty to disclose their HIV status, will ensure that they face even stricter guidelines than before about reporting their HIV status and, hence, ensure stringent testing and management of their condition. Optimistically, facilitating fair, mutual disclosure of HIV, will result in less HIV stigma, more acceptance of this disease and open communication between the clinician and the patient.

However, there are concerns about whether patients will continue to see the dentist at all, summarised accurately by Williams: ‘[C]learly in the case of the HIV positive dentist, it is not that the patient would not proceed with the treatment, simply that they would not proceed with the treatment provided by this particular dentist’ and ‘in short it is the patient who decides if the HIV status of the dentist is relevant to their treatment’.[34] He then concludes with, ‘clearly the choice faced by the dentist between disclosure and informing patients ... is not a happy one’.[35]

This highlights that the same issue remains: dentists are still unable to refuse to treat patients with HIV, but patients can easily refuse to continue to see their dentist based on their declared HIV status. Although this is discriminatory, it is ethically seen as the patient’s autonomous right to do so.

In turn, mutual disclosure will minimise transmission risk to the dentist but may still expose them to unjust discrimination and judgment. This may have more significant consequences than we could envisage, especially concerning well-researched statistics around higher occupationally-linked suicide rates amongst dentists related to ‘burn out and mental health problems’.[36] Although morbid, it would not be too far-fetched to suggest that further discrimination and loss of patients due to having a disease that is not without its own burdens, could increase the mental health problems in the dental community and contribute to higher suicide rates. The need to honour patient wishes and choices should not outweigh the mental well-being of practitioners and a balance between the two should be sought. Previously, dentists were not even allowed to practice if they had HIV. However they also did not need to advise all patients of their HIV status either. Advising patients of a dentist’s HIV status can mean that those ‘who have nothing to do with the dentist’s practice ... will inevitably come to know of the dentist’s condition’ as patients, unlike dentists, do not have a duty to keep such disclosures confidential.[37]

Preventing discrimination and HIV stigma is not a task that can easily be achieved. As discussed earlier, HIV is still highly prevalent in the community. Some of the key reasons for this are ‘inaccurate public perception’, ‘significant decline in public knowledge’ and people ‘still alarmingly ignorant about HIV’.[38] Educating the public and health care workers is the first step to ensuring there are no misconceptions about HIV, awareness of how effective anti-retroviral therapy is and the negligible transmission rates of HIV if it is treated. Simultaneously, greater awareness of the disease may also lead to its prevention.

In the last decade some of the education and information that we have received does come from media outlets, however ‘sensationalised stories in the national media ... relat[ing] to the enduring stigma and moral blame attached to HIV infection’ has made the situation worse.[39] Media outlets should be portraying accurate facts and figures of the HIV transmission rates to alleviate concern and anxiety in the community, instead of purposely alarming the public for more views. Strategies such as impactful social media initiatives, more education on HIV in universities, schools and workplaces through HIV awareness programs, campaigns targeted at communities with greater levels of HIV stigma and further research into HIV stigma will raise public awareness. Opening up discussion and normalising a disease that has been seen as so sinister in the past will slowly change public perceptions.

VI Duty of Disclosure to Sexual Partners

When considering legally mandating mutual disclosure of HIV status between patient and health care practitioner, we should also consider that there are no longer laws, at least in NSW, requiring mandatory disclosure of sexually transmitted infections, such as HIV, to sexual partners.[40] An amendment to the Public Health Act 2010 (NSW), meant people with HIV were no longer legally required to inform their sexual partners that they were infected with HIV, as long as reasonable measures had been taken to prevent transmission, such as by using a condom.[41] Liberal MP Peter Phelps expressed concerns with this as it now meant individuals could conceal their status and trick ‘sexual partners into bed unaware of the risks’.[42]

There were strong arguments for the revision though, with the NSW Health review describing the previous laws as a ‘blunt and ineffective tool’ as, due to stigma, people chose not to get tested. A more effective approach would be providing screening and education on safe sexual practices.[43] Since the amendment of the law, there has been a 39% reduction in new HIV transmission cases and, in the first six months of 2017, NSW had its lowest number of new reported cases since the start of the HIV epidemic in the 1980s.[44]

These statistics suggest that legally requiring disclosure of one’s HIV status may worsen rather than improve the HIV transmission rates due to stigma, and that the ethical principles behind needing to disclose do not overrule an individuals’ personal choice not to. It would seem unlikely, given Australia’s current laws on disclosure to sexual partners, that a shift to legislate for disclosure from one party to another in the health care setting – or mutual disclosure, would be happening anytime soon. The focus instead, similarly, would be on education, screening and trying to lessen HIV stigma.

VII UK Duty of Disclosure Regulations

Public Health England, an agency of the Department of Health in the UK, updated its guidelines in 2014 in a similar fashion to Australia’s more recent revised guidelines, permitting health care workers performing exposure-prone procedures, to still practise.[45] Its mission ‘is to protect and improve the nation’s health and to address inequalities through working with national and local government’.[46] Its decision was made after thorough research into the risk of transmission between health care workers and patients.

Findings from the UK Advisory Panel for Health Care Workers Infected with Blood-Borne Viruses (UKAP), the Expert Advisory Group on AIDS (EAGA) and the Advisory Group on Hepatitis (AGH), determined that the risk of HIV transmission from an infected health care worker who is not undergoing treatment, to a patient is extremely minimal for invasive procedures and negligible for procedures that are less invasive.[47] Studies from patient notification exercises between 1998 and 2008 did not find any incidences of HIV transmission from a health care worker to a patient from a sample size of ten thousand patients being tested.[48] A report from the Tripartite Working Group suggests the risk of HIV transmission to a patient undergoing a highly invasive exposure-prone procedure is from one in thirty three thousand to one in eight hundred and thirty three thousand.[49] These statistics clearly reflect patients are exposed to negligible harm when treated by HIV infected health care workers.

Guidelines for infected health care workers to practise include either being on an effective combination anti-retroviral therapy and having a viral load of less than two hundred copies/ml or be an ‘elite controller’ in addition to monitoring every three months, supervision by two physicians and being on the UKAP Occupational Health Monitoring Register.[50] The below table illustrates actions required depending on the amount of viral load counts.[51]

|

Viral Load Count Test Result

|

Action

|

|

<50 copies/ml or below

|

No action – retest in 3 months

|

|

50-200 copies/ml

|

A case-by-case approach based on clinical judgement would be taken which

may result in no action (as above) or a second test may be

done 10 days later to

verify the first result. Further action would be informed by the test

result.

|

|

>200 copies/ml but <1000 copies/ml

|

A second test should automatically be done 10 days later on a new blood

sample to verify the first result. If the count was still

in excess of 200

copies/ml, the HCW would cease conducting EPPs until their count, in two

consecutive tests no less than 3 months

apart, was reduced to <200

copies/ml.

|

|

1000 copies/ml or above

|

The HCW would cease conducting EPPs immediately. A second

test must be done on a new blood sample 10 days later to verify the first

result. If the count was still in excess of 1000

copies/ml, a full risk

assessment should be initiated to determine the risk of HCW to patient

transmission. At a minimum this will

include discussion between the consultant

occupational physician and the treating physician on the significance of the

result to

HIV transmission.

Following a risk assessment exercise, a Patient Notification Exercise (PNE)

may be indicated. UKAP advice may be sought at this stage.

|

The strict guidelines and actions enforced demonstrate the balance between allowing health care workers to practice and keep their occupation, as well as ensuring patient safety. Currently the UK has an HIV awareness charity called Saving Lives directed by Dr Steve Taylor, an HIV specialist at the Birmingham Heartlands hospital.[52] His belief that ‘people living with HIV who are on stable effective treatment will have undetectable levels of virus in their blood’ and ‘the risk of their blood infecting another person through a needle-stick injury is almost nothing’ reflect the UK’s current stance that if ‘you feel that patients have a right to know when the person treating them is carry a life-threatening virus ... you need better information’.[53]

The article by Leo Benedictus puts into perspective Dr Taylor’s expert opinion but also compassionately features the story of two NHS staff members suffering with HIV and now being able to practise.[54]

Shamin Onyago shares her heart-felt story of having lost her baby to HIV after unknowingly being infected by her first husband.[55] She was denied the opportunity to pursue her dreams as a doctor and midwife at the time and become an acute medical nurse.[56] She details how a colleague removed her from the computer system when she was found to have HIV from a medical assessment after getting a fever through one of her shifts, to save her from the embarrassment.[57] Her story is poignant, one of discrimination, hardship and determination to continue to work in a profession that she is passionate about. A story like this reflects the changing attitudes in the UK about health care workers being shamed for HIV and now having the right to pursue their opportunities.[58] As a result, the UK does not have any legislation requiring that health care workers share their HIV status with patients.[59]

Following the revision of the law preventing health care workers from practising with HIV in the UK, England’s chief medical officer, Professor Dame Sally Davies commented: ‘We’ve got outdated rules. At the moment we bar totally safe health care workers who are on treatment with HIV from performing many surgical treatments, and that includes dentists’.[60] She discusses how, rather than focusing on excluding health care workers from performing procedures, ‘what we need is a simpler system that continues to protect the public through encouraging people to get tested for HIV as early as possible and that does not hold back some of our best healthcare workers because of a risk that is more remote than being struck by lightning’.[61] Her sensible approach looks at preventive methods, screening and education rather than exclusion of health professionals. She is backed by the chief executive of the National Aids Trust, Deborah Jack, who also said, ‘allowing healthcare workers living with HIV to undertake exposure-prone procedures corrects the current guidance which offers no more protection for the general public but keeps qualified and skilled people from working in the career they had spent many years for’.[62]

Sir Nick Partridge, chief executive at an HIV charity, sums up this reassuring approach by indicating, ‘so long as the right safeguards are in place, there is now no reason why a dentist or a midwife with HIV should be barred from treating patients, or why people who would prefer to test at home should be denied that chance’.[63] His comments along with those of Professor Davies and Deborah Jack highlight how dated it is to exclude or ‘bar’ health professionals with HIV and, on that note, to force dentists and other health professionals to disclose their status.

Instead, given current statistics, as long as dentists behave responsibly and report their condition, they should have the right to not notify patients, as the risk to them is so negligible. The UK expert opinions evidently support the notion of health care workers practising without necessarily disclosing their status, however there are no recent surveys or studies reflecting the views of patients and the views of the wider UK population.

An article published in the Journal of Medical Ethics in 2000, found through surveys, that ‘patients do wish to have information about a risk to which they had inadvertently been exposed in the health care setting, even though that risk was very small’, solidifying patients’ wishes to be notified of their dentists having HIV.[64] However that article is incredibly dated, just as the laws for HIV infected health care workers were, and, given no up to date research has come about to analyse current patient perceptions, it may suggest a gap in the research, a lack of awareness of the amendments or that it may not be necessary to look into this because of overall patient acceptance of the present UK position. It would seem likely that, if the law for HIV infected workers had met significant resistance, research, studies and cases would have appeared presenting the patients’ arguments.

The lack of current research showing that patients prefer dentists to disclose their HIV status may also indicate that that is no longer the case and that legislated mutual disclosure or merely sole disclosure from practitioner to patient in the UK may not be necessary. If it is a matter of lack of public awareness of the amendments, more education needs to be provided which will, in turn, not only present the situation about dentists practising with HIV to patients but the facts and statistics as to why they are safe to do so.

There are no UK laws requiring HIV infected individuals to notify their sexual partners of their status, ‘in England and Wales there is no liability where someone merely exposes another to the risk of transmission’, unless the action was found to be deliberate and the individual was fully aware of the condition.[65] In the majority of situations, as long as individuals have utilised precautionary measures such as simply wearing a condom, ‘recklessness will probably not be established’. [66]

These current circumstances where sexually active people infected with HIV do not have a legal duty of disclosure has occurred due to how complex and vexed the matter is and it originated after heavy discussion and research around the effects of criminalising those who do not disclose. A qualitative study published in 2015 examined perceptions on criminal prosecutions for HIV transmission through seven focus groups, led by seventy five health professionals with experience in the clinical and community based services for those with HIV.[67] Unfortunately such legal persecutions have been shown to result in the disruption of HIV services being provided.[68]

This study illustrated that criminalisation can negatively impact progress in public health objectives as it does not support HIV precautionary behaviour and may also affect HIV-infected individuals forming trusting relationships with health professionals and HIV service providers.[69] The study explored views around the debate of ‘public health ethics’, ‘professional ethics’ and ‘management of ethical discourse and practice in HIV settings’.[70] No individuals were able to identify positive public health outcomes from criminalisation and ‘others felt that the criminalisation brought only harmful consequences for their working environments, and by extension, for health outcomes among their service users’.[71] A community service provider noted how difficult it was to regain trust with clinicians due to the severe negative effects from being prosecuted.[72]

Ultimately, creating laws which result in prosecution ‘can lead to increased stigma, reduced trust between service users and providers, and traumatic consequences for those who get involved in such cases’.[73] These findings illustrated how the law and criminal justice can hinder public health objectives and individual needs.[74] The majority of respondents in this survey felt that imposing greater potential liability and criminal responsibility would create barriers to vulnerable individuals trying to access HIV services.[75]

Most of the participants also found themselves ‘caught between a clinical medical ethics of individual autonomy (grounded in human rights), and a public health ethics which emphasises the good of the collective’, accentuating the need for a middle ground.[76] This study highlighted the complex nature of criminalisation and its impact, demonstrating how the UK’s choice not to initiate a compulsory duty of disclosure to either sexual partners or patients, is one that has been well thought out after consideration of a multitude of factors such as overall better public health outcomes and protection of individuals and health practitioners alike.

When considering Australian laws on the duty of disclosure moving forward, it would be wise to look at the UK’s experience. Australia followed suit three years after the UK’s amendments on health practitioners practising with HIV and it would seem appropriate that Australia also acknowledge the UK’s stance on not requiring a duty of disclosure to patients nor sexual partners. Australia would benefit from evaluating the public’s perceptions and views through qualitative research, assessing views on being treating by a practitioner with HIV and perceptions of the current laws around informing sexual partners of sexually transmitted diseases. This should coincide with greater educational interventions to ensure public perceptions are not misguided by the media or long-standing prejudices but are, in fact, influenced by proper facts, figures and an awareness of HIV treatments and the low risk of transmission rates.

Given the UK’s current fears that criminalisation could affect public health outcomes, it would be reasonable to also share doubts about whether forcing individuals to declare their HIV status and punishing them if they do not, would be beneficial to a society that is still impacted by HIV stigma. Hence, the answer to the question whether health practitioners should be disclosing their status to patients, parallel with whether or not individuals should be advising their partners prior to sexual intercourse, is ‘no’, if proper precautionary methods are adhered to.

In the event of widespread protest in the Australian community, current laws and regulations would need to be assessed as the law should always adapt to change – an option always readily available in our system of parliamentary democracy. But, as mentioned earlier, any change should consider all parties. Legislating for disclosure by both patient and dentist will ensure that we are distributing justice fairly and acknowledging the needs of both patients and health care workers.

VIII The US Duty Of Disclosure Regulations

Currently, guidelines exist in all fifty states of the United States (and in most of its other non-state jurisdictions) relating to health care workers being tested for HIV, disclosing their status to patients and outlining the consequences of non-compliance.[77] All states acknowledge that the risk of transmission from health care workers to patients is negligible and prefer voluntary testing to mandatory testing, as mandatory testing would make little difference to risk. Mandatory disclosure was also not enforced across all states as this could result in health care workers not testing altogether.[78] However, the states did differ on a number of other factors. Some require HIV infected health care workers to stop undertaking exposure-prone procedures until further notice from a panel whilst others recommend seeking a panel’s advice voluntarily.[79] In terms of notifying patients, some states require the panel to make the decision, depending on the case, and others require consent from the patient before a health care worker could proceed with an invasive procedure.[80]

In Alabama, dentists need to have an expert review panel (ERP) advise the State Health Officer (SHO) whether patients need to be notified retrospectively of any invasive procedures that were performed by an affected dentist.[81] There appears to be no specific statement about advising patients after dentists undergo treatment and meet guidelines to practice with HIV.[82] In Alaska, the accepted view is that ‘a blanket policy of disclosure would fail to make workplaces safer and would have a deleterious impact on access to healthcare’, thus clearly advocating for non-disclosure to patients.[83] In Arizona, retroactive notification to patients differs depending on the case and the decision made with local and state health officials.[84] In Arkansas, interestingly, an infected dentist must notify all patients and other health care workers of his or her status prior to performing exposure-prone procedures.[85] In California, dentists need to consult with an ERP about whether they are responsible to disclose their HIV status to patients when performing procedures that may put those patients at a greater risk.[86] In Colorado, patients may need to be notified if the condition impairs a dentist’s ability to perform the procedure and increases risk to the patients and/or involves serious breaches to universal precautions.[87]

The duty of disclosure in Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, North Carolina, South Carolina, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Utah and Vermont, Virginia, Iowa, Kentucky, Montana, New York, Washington and Wyoming is subject to judgement by a review panel depending on the case.[88] The stance taken in Maryland is to follow universal precautions as specific guidelines do not exist, Minnesota requires a monitoring plan and potentially also consideration by a review panel whilst Mississippi expects dentists to meet current Recommended Infection Control Practices for Dentistry as per the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.[89]

Georgia requires judgement by a review panel as well as written informed consent from all future patients having exposure-prone procedures if ‘documented transmission has occurred’ on a case-by-case basis.[90] Hawaii, Oklahoma, South Dakota and West Virginia advise that patients exposed to an infected HIV worker’s blood or bodily fluids must be notified.[91] Idaho only demands patient notification ‘in the case of imminent public health threat’.[92]

Illinois requires that any potential risk of transmission to patients during invasive procedures must result in advising the patient.[93] In Louisana, Pennsylvania and Texas, dentists must advise patients of their HIV status and be given consent from the patient prior to performing any procedures.[94] In Maine and Massachusetts, dentists or any other health care professionals are not required to disclose their HIV status to patients or staff.[95] Michigan and Nevada require consultation with local and state health officials to determine if patient notification is necessary.[96]

Missouri recommends that patients be informed of a dentist’s HIV status if the panel is uncertain about the risk of transmission from a procedure.[97] Nebraska exempts dentists from patient notification if they are within treatment and monitoring guidelines.[98] In New Hampshire, dentists with HIV cannot perform invasive procedures unless an application has been submitted to the commissioner and approved. Current employers need to be notified of any imposed conditions and previous patients who may have been treated when the health care worker was infected and future patients also need to be notified.[99]

New Mexico insists that patients who have a ‘significant risk of transmission of blood borne infection’ must be notified but the identity of the provider does not need to be disclosed.[100] North Dakota does not encourage retroactive notification of patients that may have been exposed to HIV or ‘disclosure of the source of exposure’ and it is up to the infected health care worker to choose to advise patients or not.[101] Ohio recommends that retroactive notification be decided by the Director of Health after considering the case.[102]

Oregon insists that patients are not notified unless HIV transmission from a dentist to patient has occurred, the patient has had significant exposure to the dentist’s blood or bodily fluids or the dentist has had substantial breach of infection control practices. It also maintains that the identity of the dentist not be disclosed.[103] Wisconsin requires retrospective notification on the same basis as Oregon however does not mention that the dentist’s identity not be disclosed.[104]

Therefore, in the US there is significant variation between whether or not a mandatory duty of disclosure is required, depending on the jurisdiction in which the health practitioner resides. Some states such as New Mexico, New Dakota and Oregon allow for protection of a dentist’s identity if patient notification is required, whereas some states such as Maine, Massachusetts and Nebraska explicitly advise that patient notification is not necessary. Some states do not have recorded or known recommendations – which further highlights the inconsistencies between the states.

The majority of states require assessment by an expert review panel, however this could mean that decisions taken by expert review panels in each state could differ significantly. Aside from the lack of cohesion in duty of disclosure guidelines between the states, health professionals could easily move to different states to avoid not disclosing their status if they wanted to, which would diminish the state’s original intention in having those laws.

It would be fair to say that, when evaluating the US regulations around duty of disclosure, it would create disharmony between Australian states if we were to adopt a similar system and have differing regulations in each jurisdiction. Not too long ago, we also had a different duty of disclosure laws to sexual partners in each state but this has since been simplified and it is now uniformly accepted that it was not required.

Twenty four states in the US require individuals who are aware of their HIV status to notify their sexual partners and fourteen of these also mandate notifying needle-sharing partners.[105] HIV related criminalisation measures include thirteen states which impose additional liability for prostitution by those with HIV, eleven criminalising behaviours ‘such as biting, spitting, and throwing bodily fluids’, nineteen criminalising blood, tissue or bodily fluids donation by such persons and five imposing additional sentencing for sexual offenses committed by them.[106] To better understand the gravity of these laws, it is important to note that eighteen states impose sentences of up to ten years imprisonment, seven impose sentences of between eleven and twenty years and five can sentence offenders to more than twenty years.[107] Such harsh punishments have been a controversial public health topic for some time now, with studies in 2017 by public health advocates finding that HIV-exposure laws in the US increase HIV stigma, discrimination and hence undermine US public health efforts to prevent further HIV infections.’[108] Commentators are also concerned that these laws do not sustain a supportive environment for voluntary disclosure and HIV testing, prevention and treatment services.[109]

In 2010, the Positive Justice Project identified that these laws do not acknowledge advances in medical treatments for HIV and scientific research showing decreased risk in HIV sexual transmission by individuals who are undergoing treatment.[110] This paper identifies flaws in the current legal system surrounding disclosure to sexual partners and calls for more research into whether these laws ‘are informed about by current medical and scientific knowledge about HIV transmission ...and studies that examine race/ethnic disparities in enforcement of the laws.’[111] It also suggests that more studies into HIV prevention and care services and the impact of criminalisation laws on the relationship between HIV patients and practitioners should be undertaken to better evaluate the effectiveness of these laws.[112]

Although to a lesser degree than is the case with the duty of disclosure to patients laws, the US duty of disclosure to sexual partners’ laws also appear inconsistent and variable betweenstates. Current evidence demonstrates that laws around compulsory disclosure to sexual partners do need to be reconsidered as their emphasis on punishment may deter individuals from seeking preventive measures and health care services, as well as not reflecting up-to-date scientific research on HIV transmission risks. These findings also coincide with qualitative research performed in the UK demonstrating how criminalisation can be at odds with public health outcomes, prompting the UK’s decision not to enforce a compulsory duty of disclosure to sexual partners.

IX Conclusion

Currently, no laws exist in Australia requiring patients or dentists to disclose, truthfully, their HIV status in the dental setting. The ethical principles, patient autonomy and non-maleficience raise important issues about patients having the right to be informed of their dentists’ HIV status and awareness of the risks that they may be subjected to when having treatment done. This is to allow patients to have self-determination, the choice to decide on their health outcomes and to give their informed consent.

Non-maleficence raises ethical concerns about dentists with HIV potentially doing harm and why patients have a right to be aware of this possible harm. However, the principle of justice highlights the importance of patients having legal obligations to inform dentists of their HIV status also. This ensures dentists can provide treatments that do not counteract with patients’ HIV medications and can monitor or treat oral lesions induced by HIV. Being aware of a patient’s HIV status also offers greater protection to dentists as they are able to seek pre-exposure prophylaxis and post-exposure prophylaxis to prevent risk of transmission. Considering both these views, it would be fair and just that patients be required to legally disclose their HIV status if they expected dentists to do so. However, dentists are still at a disadvantage as patients may still choose to discriminate and refuse to see them based on the declaration of their HIV status.

The notion of discriminating against those with HIV and HIV stigma demonstrates the need for the public to be more well-informed about the treatability of the condition and the negligible transmission rates. More education through social media platforms, community-based interventions and further studies into public perceptions will be useful in achieving this. This will also assist in awareness about the disease and prevention of HIV being sexually transmitted. There are no longer any Australian laws requiring that individuals declare their HIV status to sexual partners if they are taking precautionary measures, due to how low the risk of transmission is perceived to be.

The duty of disclosure laws in UK and US also provide useful comparisons. The UK amended its national guidelines for health professionals working with blood borne viruses three years before Australia did, demonstrating their more rapid advancements in eradicating old laws that excluded health care workers and did not reflect scientific and medical accomplishments. The UK does not require that health care workers disclose their status to patients or HIV infected individuals to sexual partners, as long as the guidelines were adhered to and precautionary measures were taken. Its decision reflects opposition to criminalisation laws that may deter individuals from testing, seeking HIV services or trusting their service providers. This would, in turn, detrimentally impact on public health goals and outcomes.

The US has far more complex laws surrounding the duty of disclosure for both dental practitioners and sexually active HIV infected individuals. Currently, some states have unknown legal requirements around dental practitioners disclosing their HIV status, some advise that it is mandatory that patients be informed and give consent, some decide on a case to case basis after review by a panel and some only require retroactive notification if patients have been known to be exposed to a practitioner’s blood or bodily fluids. It is interesting to also note that some states did not require, or preferred that dentists did not disclose, their identity when notifying patients.

The US laws surrounding disclosure to sexual partners also varied, the majority of states requiring that sexual partners be informed and certain states providing for specific responses in different instances such as prostitution. The states also differed in the durations of the sentences that could be imposed for infractions.

After carefully considering the ethical principles and the Australian, UK and US legal standpoints, it would appear that there is clear potential for criminalisation to cause more harm to public health outcomes and that Australia’s current position in not requiring dentists to disclose their HIV status is justifiable on the available evidence. However, as a result of the inconsistencies between both the individual states and the studies conducted in the US on the negative impacts of criminalisation, it also seems that more resources are required for preventive and education regimes rather than legislating for a duty of disclosure. If patients were to protest and insist upon dentists having to declare their status in Australia, it should only be mandated if patients had a mutual responsibility to do the same.

In terms of disclosure to sexual partners, more guidelines should be put in place. Similar to those governing the need for health practitioners to undergo regular testing, treatment and have acceptable viral loads, sexually active HIV infected individuals should also be required to do this to protect the public. Currently, precautionary measures such as merely wearing a condom is unsatisfactory in ensuring that transmission is negligible, just as simply wearing gloves is not enough to warrant allowing dentists with HIV to practise.

[1] Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council (AHMAC), ‘Australian national guidelines for the management of healthcare workers living with blood borne viruses and healthcare workers who perform exposure prone procedures at risk of exposure to blood borne viruses’, (26 June 2018) The Department of Health 7.

[2] Leo Benedictus, ‘New NHS guidelines on doctors and nurse with HIV will change lives’, The Guardian (online, 18 August 2013) < https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2013/aug/18/nhs-guidelines-doctors-nurses-hiv>.

[3] AHMAC (n 1) 17.

[4] Ibid 7.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Yusrita Zolkefli, ‘Evaluating the Concept of Choice in Healthcare’ (2017) 24(6) Malaysian Journal of Medical Sciences 92.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] John Palmieri and Theodore Stern, ‘Lies in the Doctor-Patient Relationship’ (2009) 11(4) The Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 163.

[10] Gale Scott, ‘Even Healthcare Workers Attach Stigma to HIV’, MD Magazine (online, 21 November 2016) <https://www.mdmag.com/medical-news/even-health-care-workers-attach-stigma-to-hiv>.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Jay A Jacobson, ‘A Surgeon with HIV’ (2009) 11(12) AMA Journal of Ethics 933.

[13] Shivani Mathur and Rahul Chopra, ‘Ethical issues in Modern Day Dental Practice’ (2013) 8(2) Online Journal of Health Ethics 1.

[14] Ibid.

[15] M Williams, ‘The HIV positive dentist in the United Kingdom – a legal perspective’, (2009) 207 British Dental Journal 77.

[16] Lawrence K Altman, ‘AIDS and a Dentist’s Secret’, New York Times (online, 6 June 1993) <https://www.nytimes.com/1993/06/06/weekinreview/aids-and-a-dentist-s-secrets.html>.

[17] Ibid [5].

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid [16].

[20] Ibid [22].

[21] D Croser, ‘The tipping point’, (2010) 208 British Dental Journal 48-49.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid [7].

[24] Fred M Feinsod and Cathy Wagner, ‘The Ethical Principle of Justice: The Purveyor of Equality’ (2008) 16(1) Annals of Long-Term Care.

[25] Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth) s 5 (the definition of ‘disability’ in s 4 of the Act is sufficiently wide to include diseases such as HIV).

[26] Ibid ss 21-24.

[27] ASHM, ‘Guide to Australian HIV Laws and Policies for Health Professionals’, ASHM (Web Page) <http://hivlegal.ashm.org.au/safe-behaviours-and-disclosure> .

[28] Kristen Underhill et al, ‘Explaining the Efficacy of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV Prevention: A Qualitative Study of Message Framing and Messaging Preferences among US men Who Have Sex with Men’ (2016) 20(7) AIDS and Behavior 1514.

[29] Yogesh S. Marfatia et al, ‘Pre- and post-sexual exposure prophylaxis of HIV: An update’ (2017) 38(1) Indian Journal of Sexually Transmitted Diseases and AIDS 1.

[30] Sean Slavin, ‘Results from the Stigma Audit: a survey on HIV stigma in Australia’, Positive Living Magazine, (online, March 2012) <https://www.afao.org.au/article/results-stigma-audit-survey-hiv-stigma-australia>.

[31] Ibid [7].

[32] Ian LC Chapple and John Hamburger, ‘The significance of oral health in HIV disease’ (2000) 76 (4) Sexually Transmitted Infections 236.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Williams (n 16) [26]–[27].

[35] Ibid.

[36] LM Jones et al, ‘A review of occupationally-linked suicide for dentist’ (2016) 112(2) New Zealand Dental Journal 39.

[37] Williams (n 16) 80.

[38] Ibid 79.

[39] Ibid.

[40] ASHM (n 28).

[41] ‘Con, or condom? Uproar over changes to HIV and STI disclosure law,’ News.com.au, (online, 15 September 2017) <https://www.news.com.au/national/nsw-act/con-or-condom-uproar-over-changes-to-hiv-and-sti-disclosure-law/news-story/7e07c4f76526d4073f5f423e3303da07>.

[42] Ibid [4].

[43] Ibid [18].

[44] Ibid [22].

[45] Public Health England, ‘The Management of HIV Infected Healthcare Workers who perform exposure prone procedures: updated guidance, January 2014’, (January 2018), Department of Health.

[46] Ibid 2.

[47] Ibid 4.

[48] Ibid 5.

[49] Ibid.

[50] Ibid 6.

[51] Ibid 8.

[52] Benedictus (n 2).

[53] Ibid.

[54] Ibid.

[55] Ibid.

[56] Ibid.

[57] Ibid.

[58] Ibid.

[59] Ibid.

[60] Jenny Hope, ‘Surgeons and dentists with HIV to be allowed to operate on patients after ban is lifted by Government’, Daily Mail, (online, 15 August 2013) <https://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-2393946/NHS-surgeons-dentists-HIV-allowed-operate-patients-ban-lifted-Government.html>.

[61] Ibid [16].

[62] Ibid [17].

[63] Ibid [19].

[64] Oliver Blatchford et al, ‘Infectious health care workers: should patients be told?’ (2000) 26(1) Journal of Medical Ethics 27.

[65] Catherine Dodds, ‘Keeping confidence: HIV and the criminal law from HIV service providers’ perspectives’ (2015) 25(4) Critical Public Health 410.

[66] Ibid.

[67] Ibid.

[68] Ibid.

[69] Ibid.

[70] Ibid 419.

[71] Ibid 410.

[72] Ibid 415.

[73] Ibid 419.

[74] Ibid.

[75] Ibid.

[76] Ibid 420.

[77] The Center for HIV Law and Policy, ‘Guidelines for HIV-Positive Health Care Workers’, HIV Law and Policy (Web Page, March 2008) <https://www.hivlawandpolicy.org/sites/default/files/HCW%20chart--Final%20Apr08.pdf>.

[78] Ibid.

[79] Ibid.

[80] Ibid.

[81] Ibid 2.

[82] Ibid.

[83] Ibid 3.

[84] Ibid 4.

[85] Ibid.

[86] Ibid 5.

[87] Ibid 7.

[88] Ibid 8.

[89] Ibid 10.

[90] Ibid 11.

[91] Ibid 13.

[92] Ibid.

[93] Ibid 15.

[94] Ibid 18.

[95] Ibid 22.

[96] Ibid 23.

[97] Ibid 26.

[98] Ibid 28.

[99] Ibid 30.

[100] Ibid 32.

[101] Ibid 36.

[102] Ibid 37.

[103] Ibid 39.

[104] Ibid 49.

[105] JS Lehman et al, ‘Prevalence and Public Health Implications of State Laws that Criminalize Potential HIV Exposure in the United States’ (2014) 18(6) AIDS and Behavior 997.

[106] Ibid 998.

[107] Ibid 1001.

[108] Dini Harsono et al, ‘Criminalization of HIV Exposure: A Review of Empirical Studies in the United States’ (2017) 21(1) AIDS and Behavior 27.

[109] Ibid 30.

[110] Ibid.

[111] Ibid 41.

[112] Ibid 43.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/ JCULawRw/2022/6

JCULawRw/2022/6  .html

.html