University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

POLICING THE POLICE: INDEPENDENT INVESTIGATIONS FOR VICTORIA

SINÉAD O’BRIEN BUTLER*

In Victoria, complaints against the police made by members of the public are predominantly investigated and determined by serving police officers. Such police-dominated complaints mechanisms are widely considered to be ineffective, and are being increasingly abandoned the world over.

With reference to the obligations imposed by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, this article critically examines Victoria’s police-dominated complaints mechanism and argues that it violates the right to an effective remedy contained in article 2 paragraph 3 of the Covenant. As a constituent state of a state party to the Covenant, Victoria is obliged to give effect to the Covenant’s obligations, and so must create an independent police complaints mechanism tasked with investigating complaints made against the police involving allegations of breaches of the Covenant’s protected rights.

The police are one of the most important branches of the executive government. Entrusted with extraordinary powers, they serve to secure our nation and protect our rights.[1] With such great power, however, comes a heightened risk of abuse[2] which unfortunately manifests itself with shocking regularity.[3] Consequently, there is a heightened need for the exercise of these powers to be rigorously monitored, to ensure that they are lawfully deployed and that those who abuse them are held to account. Around the world, this is largely achieved by way of a public complaints mechanism, tasked with investigating complaints made by the public against members of the police, and thereby effectually policing the police.

Traditionally, the police have been responsible for operating these complaint mechanisms, meaning that it is serving police officers who receive, investigate, and determine all or the vast majority of complaints made against them.[4] Known as ‘police-dominated systems’,[5] these mechanisms tend to be characterised by questionably low substantiation rates (that is, low numbers of complaints made in which at least one allegation was determined proven),[6] and high rates of public dissatisfaction.[7] Internationally, such systems are being increasingly abandoned in favour of independent police complaint mechanisms.[8] Reform has typically followed scandalous revelations of systematic abuses of power, facilitated by ineffective complaint mechanisms.[9]

Victoria, however, retains a police-dominated system wherein somewhere between 90 per cent[10] and 97 per cent[11] of all complaints, including those containing allegations of serious rights violations,[12] will be investigated by Victoria Police. Victorian resistance to the burgeoning tide of international opinion is not because our police do not need independent oversight: the forces’ history is riddled with egregious and systematic abuses.[13] Rather, political will for reform seems lacking.

This article seeks to argue that Victoria must create a competent, independent police complaints mechanism, by virtue of its obligations under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights[14] (‘the Covenant’). It will do so by demonstrating that the current complaints mechanism fails to discharge the duty to investigate complaints containing allegations of violations of the Covenant’s protected rights, which is a component of the right to an effective remedy contained in article 2 paragraph 3 of the Covenant.

Victoria is bound by these obligations because the Covenant is a legally binding international treaty which Australia voluntarily acceded to,[15] and because article 50 of the Covenant expressly extends its provisions to the constituent states of federal nations ‘without ... [exception]’.[16] This is supported by article 27 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties[17] (‘Vienna Convention’) which forbids state parties from ‘invok[ing] the provisions of its internal law as justification for ... fail[ing] to perform’ their treaty obligations.[18] As such, Victoria – and all other Australian states and territories – are bound to execute their obligations under the Covenant, and, per article 26 of the Vienna Convention, they must do so in good faith.[19]

To make this argument, this article will first briefly discuss the Covenant and article 2(3), focusing on the duty to investigate that this article contains. It will then analyse the content of this duty with reference to the Covenant itself and relevant General Comments, alongside Views on Individual Communications (‘views’) and Concluding Observations issued by the Covenant’s treaty monitoring body, the Human Rights Committee (‘HRC’). After establishing what the duty to investigate requires, this article will examine the Victorian police complaints system, outlining why it is failing to discharge the duty. Having established this, this article will briefly discuss other reasons why Victoria should immediately consider reform, before examining a number of international independent police complaint mechanisms to identify the essential institutional characteristics required to fulfil the duty.

In so doing, this article extends the existing body of literature on police complaint mechanisms by identifying the Covenant as a source of a legally binding duty to investigate certain complaints made against the police, and by outlining a generalisable framework founded upon the Covenant for evaluating police complaint mechanisms. As this duty applies to all other state parties to the Covenant, this framework may be applied to evaluate all state parties’ police complaint mechanisms. As such, though this article analyses only the Victorian police complaint mechanism, the rationale underlying this analysis and the compliance evaluation technique utilised may be of interest to a wider audience.

Identifying a legally binding source for the duty to independently investigate is particularly important in Victoria, in light of the decision in Bare v Independent Broad-Based Anti-corruption Commission (‘Bare v IBAC’).[20] In Bare v IBAC, it was determined that the Victorian Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities (‘the Charter’) does not contain an implied duty to independently investigate violations of the Charter’s protected rights,[21] and so the Charter itself does not preclude the police from investigating allegations of Charter right violations perpetrated by the police. Given the degree of overlap between the rights protected by the Charter and by the Covenant, identifying within the Covenant a duty to independently investigate certain complaints means that in effect, the duty to independently investigate alleged violations of at least those Charter rights which overlap with the Covenant can be ascribed a ‘convincing basis’.[22] In doing so, this article hopes to strengthen the case for reform of the Victorian police complaints system.

Finally, this article adds to the literature on police-complaint mechanisms by examining the little-explored Danish police-complaints model, and by analysing the role of the Independent Broad-Based Anti-corruption Commission (‘IBAC’) in the Victorian police-complaints investigation mechanism.

At the time of writing, the Covenant has 171 State Parties, including Australia.[23] Described as ‘probably the most important human rights treaty in the world’,[24] it guarantees a number of human rights considered to be of a civil and political nature.[25] The rights protected include the right to life,[26] freedom from torture, cruel inhumane and degrading treatment,[27] slavery,[28] arbitrary arrest and detention,[29] and the right to be treated with respect when deprived of liberty.[30]

State parties to the Covenant are legally obliged to respect the Covenant’s rights and to ensure they extend to all people subject to their jurisdiction.[31] State parties must thus refrain from violating these rights, and take all steps necessary to effectuate them.[32] This requires state parties to change their domestic laws where appropriate to ‘ensure ... conformity’ with the Covenant.[33]

The treaty monitoring body of the Covenant, the HRC, monitors state parties’ compliance with the treaty and has the following functions.[34]

Firstly, as the Covenant’s ‘pre-eminent interpreter’,[35] the HRC issues General Comments authoritatively expounding the content of the Covenant’s rights.[36] Given the Covenant’s brevity, these are vital to clarify the specific obligations that the Covenant’s rights impose.

Secondly, the HRC receives mandatory periodic reports from state parties detailing measures they have taken to fulfil their obligations under the Covenant.[37] In response, the HRC issues Concluding Observations identifying areas of concern and recommending rectifying steps.[38]

Finally, the HRC receives and considers communications containing claims that a state party is failing to meet its obligations under the Covenant, upon which it issues views.[39] Communications may be authored by individual state parties complaining about the conduct of other state parties,[40] and may also be authored by individuals subject to the jurisdiction of a state party complaining about that state party, if the relevant state party has ratified the First Optional Protocol to the Covenant.[41] Australia is among 116 State Parties to have ratified the Protocol, and so the HRC is empowered to consider communications authored by state parties and by individuals alleging that Australia or one of its constituent states is failing to meet its obligations under the Covenant.[42]

Article 2(3) of the Covenant requires state parties ‘to ensure that any person whose rights or freedoms ... are violated shall have an effective remedy’.[43] The specific obligations imposed by this are discussed in General Comments 30 and 31.

These Comments outline that article 2(3) requires state parties to ensure full compensation is supplied to those whose rights have been violated, and that those responsible are brought to justice where appropriate.[44] State parties are also required to take steps to prevent breaches from reoccurring,[45] and to ensure that people have a right enshrined in the law to complain that their Covenant protected rights have been violated.[46]

Crucially, this article also imposes a duty on state parties to investigate complaints made by individuals subject to its jurisdiction ‘against it and its representatives’ alleging that their Covenant-protected rights have been violated.[47]

It is important to note that this duty arises only in relation to complaints made by an individual that their rights protected by the Covenant have been violated.[48] Relevant rights for the purpose of this article are (as outlined above) the right to life, freedom from torture, cruel inhumane and degrading treatment, and from arbitrary arrest and detention, and the right to be treated with respect when deprived of liberty. This duty does not arise in relation to complaints that the State or its representatives have violated a right not protected by the Covenant, for example the right to express opinions which advocate racial or religious hatred.

The specific content of the duty to investigate is expounded in relevant General Comments, Individual Communications and Concluding Observations.

1 General Comments

General Comments 21 and 30 provide important insights into the duty to investigate, outlining that article 2(3) ‘particularly requires’ the establishment of administrative mechanisms to effectuate the obligation ‘to investigate allegations of violations’ of the Covenant’s rights.[49]

Such investigatory mechanisms must be ‘independent’ and ‘impartial’,[50] and must investigate complaints ‘promptly, thoroughly and effectively’.[51] Further, they must be ‘competent’[52] in that they must ‘function effectively in practice’.[53] Thus, they cannot be merely formally endowed with the capacity to discharge the duty – they must also be capable of doing so in practice.[54]

In light of this, the following framework can be used to describe the basic necessary features of administrative mechanisms discharging the duty to investigate. They must be:

1. Independent and impartial; and

2. Capable of conducting an effective investigation, which is to say they are:

a. Thorough – capable of gathering all the relevant evidence; and

b. Competent – that they function effectively in practice; and

c. Prompt – timely.

To flesh out what these standards practically require, it is necessary to examine relevant Individual Communications and Concluding Observations.

2 Individual Communications

The HRC has issued a vast number of views relating to the duty to investigate complaints against the police. For the purposes of this undertaking, views were selected for examination following a two-stage selection process. Firstly, a list of all views relevant to article 2(3) and the duty to investigate was compiled, which was then filtered to isolate those views containing allegations made against police. Relevant views will now be discussed with reference to the framework outlined above.

(a) Independent and Impartial

The HRC has consistently emphasised that administrative mechanisms giving effect to the duty must be both independent and impartial.[55] In Horvath v Australia[56] (‘Horvath’) for instance, the HRC stated that ‘article 2, paragraph 3 does impose on States ... the obligation to investigate allegations of violations ... through independent and impartial bodies’.[57]

Views surveyed suggest this requires investigatory bodies to be organisationally independent from the police, as the requisite standard has frequently not been met because investigations were carried out by members of the police. [58] For instance in Guneththige v Sri Lanka,[59] the HRC found that no proper investigation was conducted as all investigatory steps were conducted by police officers from the same station as the officers identified in the complaint.[60] Similarly in Kalamiotis v Greece,[61] ‘the requisite [investigatory] standard was not met’ when Mr Kalamiotis’ claims were investigated by officers from an uninvolved police station.[62] Finally in Horvath, the HRC determined that the investigation was inadequate partially because the investigatory body (the Ethical Standards Department of Victoria Police) was an internal police department, meaning that its investigation of Ms Horvath’s complaint was considered to be neither independent nor impartial.[63]

Views surveyed demonstrate that even investigations conducted by organisationally independent bodies which rely heavily or absolutely on evidence collected by police investigators will not be sufficiently independent.[64] In Ernazarov v Kyrgyzstan,[65] for example, the HRC criticised reliance on statements made by police by independent investigators, finding the investigation had been consequently tainted by partiality in favour of police narratives. Similarly, in Gamarra v Paraguay[66] the HRC questioned the independence of an investigation which had relied almost exclusively on police and military witness statements.[67]

(b) Capable of Conducting an Effective Investigation

(i) Thorough

The HRC has repeatedly emphasised that investigations must be thorough, in that they must be capable of gathering any evidence necessary to conduct a ‘rigorous’ investigation.[68]

Investigations have not been considered thorough when they rely on police statements ‘as the principal basis for coming to a decision’.[69] Rather, investigators must gather and consider whatever relevant, available evidence is appropriate. This usually requires investigators to question all relevant available police and non-police witnesses,[70] and seize whatever evidence is necessary.[71] Depending on the particular circumstances, they may be required to conduct a full forensic investigation,[72] a ‘proper autopsy’[73] or an exhumation,[74] or to consider relevant medical evidence.[75] Investigators must also investigate suspicious circumstances and missing evidence, as discussed in Ernazarov v Kyrgyzstan.[76]

Investigations will not be considered thorough when they refuse to consider or ignore relevant, adequate, and available evidence, as per Achabal Puertas v Spain,[77] Zheikov v Russian Federation,[78] and Eshonov v Uzbekistan.[79]

Contrastingly, investigations will be considered sufficiently thorough when investigators take substantial steps to investigate claims. For example, in V L v Belarus,[80] this involved questioning witnesses, obtaining and reviewing available video and telephone evidence, and twice re-opening the case.[81] In Alzery v Sweden,[82] it involved the deployment of the significant powers of the Parliamentary Ombudsman, including compelling testimony from officers involved.[83] However, investigations will not be considered to have been insufficiently thorough simply because the complainant’s claims cannot be properly investigated because the evidence presented is inconsistent or inadequate, and has failed to stand up to scrutiny.[84]

(ii) Competent

The HRC has repeatedly determined that investigatory mechanisms must be capable of conducting adequate investigations in practice.[85] Thus, formally competent bodies which do not ‘function effectively in practice’ to the extent that they fail to satisfactorily investigate claims will fail to give effect to the right to an effective remedy, as occurred in El Boathi v Algeria[86] and McCallum v South Africa,[87] among others.[88] Further, investigations conducted will not have competently discharged the duty when investigators arrive at manifestly wrong conclusions based on the available evidence, as in Pestano v The Philippines.[89]

However, investigations will not be incompetently conducted simply because they do not produce the complainant’s desired outcome. For example, in Rabbae v The Netherlands,[90] the HRC determined that the author’s complaints had been competently investigated and determined by an impartial court in accordance with the law, despite failing to result in a criminal conviction.[91]

(iii) Prompt

The HRC clearly considers promptness to be a vital component of the duty to investigate as procedural delays have frequently been found to have resulted in the denial of the right to an effective remedy:[92] per Katwal v Nepal,[93] Bhandari v Nepal,[94] Guneththige v Sri Lanka,[95] and Alzery v Sweden.[96] However, ‘delay alone’ is usually ‘insufficient to satisfy the ... obligation to conduct a prompt ... investigation’.[97] Rather, what is important is the effect the delay has on the investigation, and whether it is justified in the circumstances. For instance, in Neporozhnev v Russian Federation[98] and Katsaris v Greece[99] the HRC found that a prolonged failure for some years to investigate the authors’ claims amounted to a violation of the right to an effective remedy because there was no reasonable explanation for the delay. In Gamarra v Paraguay, a delay of 13 months sufficed to effect a denial of the right, as it resulted in criminal charges being dismissed.[100]

(iv) Transparent

Although not emphasised in the General Comments, views surveyed stipulate that investigations should be transparent. The HRC has repeatedly stated that victims and/or their families must be included in the investigation process, and that they must be given information about the case and its progress.[101] Further, they should have the right to question evidence of the police[102] and to present evidence.[103]

Complainants should get detailed information about the results of the investigation,[104] and if the complaint is dismissed or unsubstantiated, reasons must be given to the victim; as discussed in Abushaala v Libya.[105] Further, all information supplied must be clear, specific and true:[106] in Bhandari v Nepal, for example, it was determined that the investigation conducted was flawed because ‘contradictory information’ was provided during the process, and because the final conclusions issued were insufficiently detailed.[107]

3 Concluding Observations

Concluding Observations issued by the HRC have frequently criticised state parties for not having an independent body to investigate complaints against its police forces containing allegations of violations of rights protected by the Covenant. Such criticisms have been made, for example, in relation to Hungary,[108] Hong Kong,[109] the United States of America,[110] and Zambia.[111]

Concluding Observations reviewed reiterate the themes discussed previously. For example, when reviewing Hong Kong in 1996, the HRC expressed concern that investigation of complaints ‘rests within the Police Force itself rather than being carried out in a manner that ensures its independence and credibility’.[112] It questioned the ‘high proportion of complaints against police officers which are found ... unsubstantiated’, and stated that ‘investigation[s] into complaints of abuse of authority ... must therefore be entrusted to an independent mechanism’.[113] Hong Kong has since created an Independent Police Complaints Council to investigate certain complaints made against its police force.[114]

Similar issues have been raised with Australia, in relation to its constituent states’ national police forces. For instance, in 2008, the HRC criticised that ‘investigations of allegations of police misconduct are carried out by the police itself’.[115] It recommended that Australian states immediately ‘establish ... mechanism[s] to carry out independent investigations of complaints concerning excessive use of force by law enforcement officials’.[116]

The above discussion illuminates the necessary features of administrative mechanisms discharging the duty to investigate contained in article 2(3) of the Covenant, which will now be added to the framework outlined above.

Such mechanisms must be:

1. Independent and impartial; and

a. Organisationally independent to police.

b. Must conduct their own independent investigations.

2. Capable of conducting an effective investigation; which is to say they are:

a. Thorough;

i. Must gather and consider all relevant, available evidence.

ii. Should not rely exclusively or unduly heavily upon police evidence.

b. Competent;

i. Must discharge the duty to investigate in practice.

c. Prompt;

i. Investigations must not be unreasonably prolonged without justification, unless it is the necessary consequence of a thorough investigation.

d. Transparent;

i. Investigations should involve the victim/their family; allowing them to present evidence and providing information about the progress of the complaint.

ii. Investigators must supply only clear, true information.

iii. Detailed information should be given about the progression and determination of the investigation.

The current mechanism for investigating complaints against Victoria Police is essentially two-tiered, comprising Victoria Police and the Independent Broad-Based Anti-corruption body. IBAC is an independent statutory body with an anti-corruption mandate, established in 2012.[117]

Complaints may be made to either Victoria Police, IBAC, or both.[118]

Complaints made to Victoria Police can be made at a local police station or to the Police Conduct Unit (‘PCU’). Complaints made to local stations will be assessed and forwarded to the PCU, which determines whether to dismiss it or classify it according to the Victoria Police complaint classification guidelines.[119] Complaints made to the PCU will be similarly assessed and either dismissed or classified.[120]

Classified complaints will then either be referred to a local police station for investigation, resolved by the PCU, or referred to the Police Standards Command (‘PSC’) for investigation, depending on their seriousness.[121] About 90 per cent of complaints investigated by Victoria Police are referred to local stations, with the PCU and PSC responsible for the remaining 10 per cent.[122]

If a classified complaint is determined to contain allegations of police misconduct, defined as ‘conduct which constitutes an offence punishable by imprisonment; or ... which is likely to bring Victoria Police into disrepute or diminish public confidence in it; or ... [is] disgraceful or improper ...’,[123] an investigation must be initiated.[124] As soon as the complaint is determined to contain such allegations, Victoria Police are required to notify IBAC.[125] IBAC will not be notified of complaints received which are immediately dismissed or which are classified as being less serious, specifically Local Management Resolution matters and Management Intervention Model matters.[126]

Investigations are conducted by police officers and may be internally reviewed by an investigation manager and/or PSC, and potentially IBAC.[127] However, IBAC’s role in conducting reviews is quite limited: it conducted just 96 reviews of complaints investigated by police in 2015–16,[128] and 73 in 2016–17.[129]

In 2016–17, 6.39 per cent of all allegations investigated by Victoria Police were substantiated.[130]

Complaints made to IBAC will be assessed and either dismissed, referred to the relevant body for investigation, or investigated.[131]

IBAC has absolute discretion to dismiss any allegation it sees fit,[132] and may determine that an investigation is not warranted where it is of the opinion, for example, that the complaint is trivial, vexatious, without merit, or made for a mischievous purpose.[133] In 2016–17, it dismissed 42.3 per cent of all allegations received about the police.[134]

For allegations not dismissed, IBAC is required to refer those it considers would be more appropriately handled by another body to that body.[135] There are no clear legislative criteria governing this assessment, however, and it seems the only complaints IBAC may not refer to Victoria Police are those involving the Chief Commissioner of Police (and some others).[136]

In practice, IBAC refers approximately 30–40 per cent of all allegations received by it to Victoria Police for investigation.[137] It has stated that its policy is to refer less serious misconduct complaints and customer service issues to Victoria Police, as it considers them best positioned to investigate and resolve these complaints, which it says constitute the vast majority of complaints.[138] However, the Police Accountability Project (‘PAP’), a flagship legal clinic in Victoria which specialises in the Victorian Police complaint mechanism, reports that IBAC has referred complaints involving allegations of serious right violations, including physical violence, to Victoria Police.[139]

For allegations received which are not dismissed or referred, IBAC may open its own investigation. IBAC is empowered to investigate complaints regarding police personnel conduct, which includes acts, decisions, and failures to act by the police ‘in the exercise, performance or discharge ... of a [police] power, function or duty’, criminal conduct, conduct likely to bring the force into disrepute or diminish public confidence in the police, or ‘disgraceful or improper conduct’.[140]

When conducting investigations, IBAC has significant investigatory powers. It may summon witnesses and compel the production of relevant documents or things,[141] and has the technical capacity to gather evidence by way of access to a forensic services unit and an intelligence unit.[142] Further, it may require police to produce documents and answer questions.[143] IBAC investigators may also enter and search police personnel premises and inspect relevant documents found there,[144] if express written authority to do so is given by the body’s Commissioner.[145]

Upon finalising an investigation, IBAC is empowered to request the Chief Commissioner of Police take disciplinary action against officers involved, though the Commissioner is not required to comply.[146] It may also refer the results of its investigations to prosecutorial bodies,[147] and can ‘exercise prosecutorial powers’.[148]

In reality these powers are rarely used in relation to the investigation of police complaints, because IBAC rarely conducts such investigations. In 2016–17, for example, it opened investigations into just 0.6 per cent of all allegations (18 allegations) against the police it received, and just 0.2 per cent in 2015–16 (excluding own motion investigations).[149]

This low rate may be explained in part by IBAC’s case selection policy. It only investigates what it considers to be the most serious allegations received, in consideration of the severity of the harm alleged, whether the relevant conduct would diminish public confidence in the public sector, systemic issues, aggravating circumstances, and the likelihood of repetition.[150]

However, this low rate is also due to section 15(1A) of the Independent Broad-Based Anti-corruption Act 2011 (Vic) (‘IBAC Act’), which requires IBAC to prioritise matters involving serious and/or systemic corruption.[151] Though these terms are not defined, this section essentially requires IBAC to focus its resources on matters other than police complaints. Pursuant to this, IBAC has stated that it sees itself not as a ‘reactive, complaints-driven body’ but rather as a conductor of ‘strategic’ investigations aimed at exposing corruption.[152]

These factors mean that ‘[t]he overwhelming majority of complaints about police [received by IBAC] are ... either dismissed ... or referred ... to Victoria Police for investigation’,[153] and so Victoria Police are responsible for investigating between 90 per cent[154] and 97 per cent[155] of all complaints made against them.

Consequently, in light of IBAC’s extremely limited role in the investigation of complaints about Victoria Police, the current Victorian complaints mechanism is best characterised as police-dominated.[156]

To determine if the complaints system described above meets the Covenant’s standards, it will now be evaluated against the framework outlined in Section II. Though IBAC plays a negligible role, in the interests of undertaking a robust analysis it will also be considered. This examination relies predominantly upon reports produced by IBAC, the PAP, and Parliamentary Reports.

Before examining Victoria Police, the comments of the HRC in Horvath should be considered as they relate specifically to a complaint-investigation conducted by Victoria Police. As discussed above, in finding Ms Horvath was denied the right to an effective remedy, the HRC found that the investigation into Ms Horvath’s complaint was not independent as the investigatory body (the Ethical Standards Department) was an internal unit of Victoria Police.[157] Though this internal unit has since become the PSC,[158] there are no indications that meaningful changes in the department have occurred.[159]

1 Independent and Impartial

To assess the independence and impartiality of Victoria Police investigations, it is useful to first define the concept of independence. Independence in this context means ‘autonomy in decision-making ... freedom from control, direction or undue influence by others’, exercised in an overt or implicit manner.[160] It is generally accepted that investigatory independence therefore requires organisational and practical independence,[161] which corresponds with the views expressed by the HRC.

Investigations conducted by Victoria Police are not organisationally independent, as they are conducted by serving police officers and directed by Victoria Police policy and practices.[162] As such, Victoria Police exercise overt control over investigations. This overt control makes it inherently unlikely that investigators can exercise the requisite degree of autonomy and neutrality necessary to conduct a practically independent investigation, and there are compelling reasons to believe that this is in fact the case.

Firstly, police investigator’s positionality likely influences the course of the investigation. Based on their knowledge and experience of what it is like to be a police officer, they are more likely to sympathise with the officer subject to the complaint and more likely to empathise with their actions than would a non-police investigator.[163]

Secondly, conflicts of interest in the investigation process are rife. For instance, in 2010 it was found that at the local level – where 90 per cent of complaints are investigated – up to 47 per cent of all files were investigated by police investigators working in the same station as the complaint’s subject officer.[164] In 2015–16, an IBAC audit revealed that 19 per cent of files involving serious allegations, including assault and serious assault, conduct punishable by imprisonment, and corruption were investigated by officers in the same station as the officer subject of the complaint,[165] while in relation to less serious matters, this figure reached 44 per cent.[166] In total, IBAC concluded that 17 per cent of all files audited had been investigated by ‘inappropriate investigators’ because of a conflict of interest.[167]

Even when investigations are conducted by officers from other stations or internal units, officers will be charged with investigating ‘former partners [and] ... future bosses’.[168] PSC investigators will necessarily have previously worked in ‘other areas of Victoria Police [and so] ... will come across matters involving officers with whom they have trained, worked and socialised’.[169] IBAC recently found that in 24 per cent of audited PSC files, the investigator was inappropriate because of a conflict of interest.[170]

Conflicts of interest such as these undermine the capacity of investigators to effectively investigate complaints[171] and to reach an unbiased, fair determination based on the actual evidence available. It means that investigators will be prone to taking into account illegitimate considerations, including loyalty to their fellow officers and a desire to provide welfare support.[172] They thus create a real risk of bias, which compromises the investigation’s efficacy,[173] and can also seriously ‘diminish [public] confidence in the complaint system’.[174]

The inference of bias raised by these conflicts of interest is supported by the factual findings of various Australian Commissions of Inquiry[175] and Law Reform Commission Reports[176] studying Australian internal police complaint departments, and academic research chronicling the ‘blue code[s] of silence’[177] which govern police internal complaint investigation departments.[178] These codes have been linked to egregious abuse cover-ups in Victoria[179] and across the world.[180]

There is also compelling evidence of actual bias corrupting Victorian Police investigations. The PAP reports, for example, that of the 103 complaints they made between 2006 and 2017 which were investigated by Victoria Police, ‘Police investigators found in favour of the police, rather than the [complainant]’ in 100 complaints.[181] Contrastingly, two of the three complaints which were investigated independently (by IBAC or by the former Office of Police Integrity) were substantiated.[182]

Furthermore, of 13 criminal cases the PAP was involved in between 2006–16, ‘[courts] contradicted the assessment made by Victoria Police’ in favour of the complainant every time, finding complaints that had been found to be unsubstantiated by the police were in fact substantiated on the evidence.[183] These findings are supported by empirical studies of Victorian and Australian judicial determinations of police complaints.[184]

Thirdly, Victoria Police investigations have a questionably low substantiation rate. Substantiation rates are considered to be ‘an important indicator of agency zeal’,[185] and are widely used to measure an investigation’s effectiveness in the relevant academic literature.[186] They tend to increase with organisational independence, anecdotally reflected in the case studies discussed in Part V.

According to Freedom of Information data, the substantiation rate in Victoria was about 9 per cent in 2013–14,[187] corresponding with the IBAC audit of 2015–16.[188] More recent data from the Police Accountability Project archives suggests it may be as low as 3 per cent,[189] while recent Victoria Police figures places it at 6.39 per cent in 2016–17.[190]

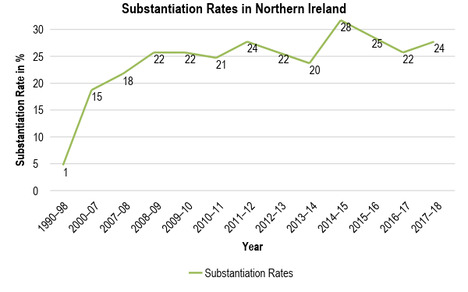

While this rate corresponds with the global average for police-dominated systems which falls between 2–8 per cent,[191] it suggests that meritorious complaints are not being substantiated when it is compared to the rate reached in jurisdictions which have independent police investigations: for example, in 2017–18 in Northern Ireland the rate was 24 per cent,[192] while in New York in 2016–17 it was 23 per cent.[193]

Findings from the 2015–16 IBAC audit lend credence to the assertion that this substantiation rate is artificially low. In the audit, IBAC auditors found that 14 per cent of unsubstantiated outcomes reached by Victoria Police investigators were inappropriate, as at least some complaints were substantiated based on the available evidence.[194] Similarly in IBAC’s 2018 audit of the PSC, auditors determined that 17 per cent of outcomes reached were inappropriate because there was either sufficient evidence to substantiate the allegation, or insufficient evidence to support the finding that the allegation was unsubstantiated.[195]

Finally, complainant experiences provide compelling evidence of partiality.[196] In one case, an investigator ‘wrote to police colleagues ... suggesting he would attempt “to cut the complaint off at the socks”’.[197] The same officer sent emails of ‘reassurance and support’ to the subject officer of the complaint, and pressured a witness to sign a pre-formulated statement saying that they had not seen the officer commit the alleged assault.[198] In another instance, an investigator repeatedly tried to make a complainant ‘sign a statement of no complaint’ regarding a serious assault complaint they had made, while another told a lawyer that ‘[a]fter 25 years in the force, I am cynical about complainants’.[199]

As such, it does not appear that Victoria Police investigations meet the required standards of independence and impartiality imposed by the Covenant.

2 Capable of Conducting an Effective Investigation

(a) Thorough and Competent

This article does not question that Victoria Police investigators have the requisite legal capacity to conduct thorough investigations. Rather, it questions whether police investigators are capable of conducting investigations in practice which meet the Covenant’s standards of thoroughness and competence.

Firstly, IBAC has determined that Victoria Police investigators frequently misclassify complaints, meaning that some allegations amounting to serious misconduct and criminality are classified as minor matters and are subsequently not notified to IBAC, or appropriately investigated.[200] In the 2015–16 audit, for instance, IBAC found that 8 per cent of all allegations audited had been inappropriately characterised or were not recorded accurately,[201] while 11 per cent were misclassified as ‘minor, customer service’ issues when they were actually more serious.[202] In the 2018 PSC audit, IBAC found that 27 per cent of audited files were misclassified, some of which had been classified as minor or correspondence matters when in fact they contained clear allegations, some involving allegations of criminality.[203]

Secondly, police investigators have been found to regularly fail to contact relevant non-police witnesses and gather relevant evidence. IBAC’s 2015–16 audit found that 34 per cent of all witnesses relevant to complaints were not contacted by the investigating officer, without a recorded explanation.[204] In 17 per cent of all cases, relevant evidence had not been considered, including CCTV footage and medical evidence.[205] A further 29 per cent of files ‘did not contain all relevant documentation’, suggesting that investigators did not consider all the relevant material.[206] IBAC’s 2018 audit of PSC similarly found that in 47 per cent of audited files, contact had not been made with relevant civilian witnesses, and in 9 of these matters no explanation for this was recorded.[207] Additionally, 42 per cent of files ‘did not appear to have appropriately considered evidence relevant to the investigation’, with the majority of these ‘fail[ing] to discuss evidence that IBAC auditors considered essential to an adequate assessment of the allegation’.[208] IBAC thus concluded that frequently ‘key evidence was not considered at all’.[209]

These failures to gather and consider relevant evidence is confirmed by the PAP, which reports discovering that in one case the police investigator did not interview the complainants at all, and relied on ‘notes made by the police’ to reach their decision.[210]

Thirdly, the efficacy of Victoria Police investigations is compromised by systemic bad practices, resulting in potentially meritorious complaints being disregarded or improperly investigated. IBAC reports that Victoria Police do not require investigation plans for complaint files, even for those involving complex matters and criminality.[211] In 2015–16, none of the files audited contained investigation plans,[212] and only 20 per cent of PSC files audited in 2018 contained a formal investigation plan.[213] Consequently, investigations may fail to address ‘relevant elements of a complaint, and to justify actions taken or not taken’.[214]

Investigators are also not required to investigate or consider the subject officer’s complaint history,[215] and it seems that this history is seldom considered. For instance, in the 2015–16 audit IBAC found that only 7 per cent of files demonstrated that this history had been considered,[216] despite the fact that in 13 per cent of all cases reviewed, auditors determined that the officers complaint history was acutely relevant, often because of a litany of similar previous complaints having been made against the officer subject of the complaint.[217] Failing to consider the officer’s complaint history ‘[disregards] critical information relevant to complaint classification, the investigation and outcomes’,[218] and is especially problematic given that some 5 per cent of the force is responsible for over 20 per cent of all complaints.[219]

IBAC has also concluded that Victoria Police investigations are often deficient. In 2015–16, for instance, it found that 36 per cent of audited complaint investigations were deficient,[220] while in 2016–17 this figure was approximately 27.3 per cent.[221] Concerningly, internal auditing had failed to identify or address these deficiencies.

Finally, Victoria Police investigators have been found to arrive at inappropriate conclusions on the evidence before them. As mentioned previously, IBAC found that 14 per cent of unsubstantiated outcomes audited in 2015–16 were flawed,[222] while the 2018 PSC audit revealed that 17 per cent of outcomes reached were inappropriate.[223]

(b) Prompt

There are issues with how quickly Victoria Police investigations are conducted. IBAC’s 2015–16 audit found that over 32 per cent of all files were overdue, with 68 per cent of these being over two weeks overdue and 5 per cent more than 100 days overdue.[224] In many cases, ‘it was unclear why the delays had occurred’.[225]

Such delays would not amount to a denial of the right to an effective remedy if they are justified in the circumstances or are a necessary consequence of a thorough investigation. The corollary of this, of course, is that investigations conducted are effective. In light of the evidence discussed above and the low substantiation rate of complaints investigated by Victoria Police, this is questionable.

(c) Transparent

Victoria Police investigations have some transparent qualities. For example, investigators are required to make contact with complainants,[226] reasons for decisions may be requested, and Freedom of Information legislation means that investigation files can be requested.

In practice, however, IBAC reports a consistent lack of ‘communication between investigators and complainants’,[227] finding ‘most complainants were not updated on the progress of investigations or provided with explanations for...delays’.[228]

Investigators rarely publish substantial reasons for decisions,[229] and in 10 per cent of all cases outcome letters were not sent to complainants, reaching 56 per cent for low level complaints.[230] The 2018 PSC audit found that final outcome letters were only sent in 54 per cent of files for complainants.[231] Letters actually sent have been found to frequently fail to comply with policy and statutory requirements.[232]

Finally, the poor investigatory practices discussed above mean that it is difficult for complainants and auditors to assess, when presented with the complaint file, whether the substance of a complaint was addressed, whether investigators complied with policy and the law in making their decisions, or what evidence was considered.[233]

To analyse whether IBAC competently discharges the duty to investigate, it is useful to segregate its supervisory and investigative functions and examine each in turn.

1 Independent and Impartial

As an independent statutory body, IBAC is organisationally independent from Victoria Police. In its supervisory function, however, it is not practically independent as its reviews depend entirely on evidence gathered by the police. As outlined above, this does not satisfy the independence criterion for the purposes of the Covenant.[234] This has been conceded by IBAC: in the course of its submissions in Bare v IBAC, IBAC stated that if there is a ‘right to an independent investigation’, investigations conducted by internal departments of Victoria Police with ‘active oversight’ by an independent supervisory body like itself ‘could not meet the [required] standard [of independence]’.[235]

In its investigatory function, IBAC conducts its own investigations organisationally distinct to Victoria Police. However, its practical independence from Victoria Police may be questioned on the following grounds.

For one, IBAC hires former police officers from Victoria Police. Though this practice occurs in some other international independent police complaints bodies, it is inherently problematic because it preserves positionality biases which may subvert the investigation, and because it suggests that IBAC may simply be an external branch of PSC.[236]

Further, it is argued that IBAC suffers from ‘regulatory capture’, a phenomenon whereby overtly independent investigatory bodies are influenced by and deferential to the bodies they are charged with investigating.[237] Such bodies tend to be characterised by patterns of favouritism toward police narratives, including the rejection of meritorious complaints.[238] Evidence of regulatory capture is said to derive from the proportion of complaints IBAC refers to Victoria Police, despite knowing that Victoria Police deficiently handle about 30 per cent of all investigations. This policy is therefore arguably suggestive of a deferential institutional attitude toward Victoria Police’s investigatory competence.

However, it must be acknowledged that IBAC has published reports which are quite critical of the way Victoria Police handles complaint investigations,[239] and it has completed a number of high profile investigations into serious police misconduct which have resulted in charges being laid against a number of police officers.[240] This suggests that IBAC may be capable of conducting investigations which demonstrate a requisite degree of practical independence from Victoria Police. However, as this article has strived to emphasise, the fact that IBAC is formally capable of conducting independent investigations into police complaints is essentially irrelevant because it conducts so few investigations.

2 Capable of Conducting an Effective Investigation

(a) Thorough and Competent

In its supervisory function, IBAC does not conduct effective investigations because it merely reviews investigations already conducted by Victoria Police. Given that IBAC reviewed just 73 such investigations in 2016–17,[241] it does not even seem accurate to contend that it meaningfully discharges this function.

In its investigatory function, IBAC appears theoretically capable of conducting an effective investigation as once an investigation has been opened, investigators may exercise significant powers, outlined previously. For instance, they may ‘compel the production of documents and objects; enter and search premises; seize documents and objects; use surveillance devices; intercept telecommunications; hold private and public hearings; [and] require people to give evidence at a hearing’.[242]

However, as stressed, these powers are rarely deployed in the context of police-complaint investigations because so few investigations are actually conducted.[243] Given that bodies discharging the Covenant’s duty to investigate must not only be formally endowed with the capacity to discharge the duty but are required to do so in practice,[244] it is unlikely that IBAC can be considered to be effectively discharging the duty to conduct thorough, independent investigations.

(b) Promptness

IBAC returns 94 per cent of complaints within 45 days,[245] but took an average of 252 days in 2015–16 to complete an investigation.[246] As IBAC had just 27 complaints open in that period, this prolonged delay is questionable.[247] However, given that numerous investigations conducted have led to charges being laid against police officers,[248] investigations conducted may be considered sufficiently thorough for the purposes of the Covenant.

(c) Transparency

IBAC investigations suffer from transparency issues, and a lack of complainant inclusion.

For example, though IBAC is required to supply reasons to the complainant when it determines not to investigate a complaint, it often fails to do so.[249] Furthermore, during the investigation process itself, IBAC has been accused of failing to keep complainants informed about the progress of complaints,[250] and the PAP reports that complainants are ‘rarely given an opportunity to give feedback to an investigation before it is finalised’.[251]

Examinations conducted are overwhelmingly private, with only 4 of 64 conducted to date being held in public.[252] This is attributable to the IBAC Act, which provides that examinations are not to be open to the public except in exceptional circumstances.[253]

Finally, because IBAC is exempted from Freedom of Information legislation, it rarely provides complainants with access to their investigation files.[254]

3 Summary

It is apparent that complaint investigations conducted by Victoria Police do not meet the required standards to discharge the Covenant’s duty to investigate complaints containing allegations of violations of the Covenant’s rights.

Investigations conducted by the IBAC may, contrastingly, satisfy the duty’s requirements. However, given that the IBAC conducts too few investigations to be capable of being properly characterised as a body effectively discharging the duty to investigate for the purposes of the Covenant, the question of whether the IBAC meets the standards required by the Covenant when conducting independent investigations is, at least for now, irrelevant.

Thus, the Victorian police complaints system fails to discharge the duty to independently investigate complaints made against the police containing allegations of violations of the Covenant’s protected rights.

This article has demonstrated that the currently existing Victorian police-complaint investigation mechanism fails to discharge the Covenant’s duty to independently investigate certain police complaints, and thus concludes that Victoria is in breach of obligations under article 2(3) the Covenant. Allowing this state of affairs to continue, despite specific remonstration by the HRC, is arguably ‘good evidence of [Australia’s] bad faith attitude towards its ... obligations’[255] contrary to article 26 of the Vienna Convention.[256]

In doing so this article has made a case for the creation of an independent complaints investigation mechanism in Victoria, to be tasked with investigating at least all complaints made against the police containing allegations of violations of the Covenant’s protected rights.

There are other compelling reasons why the Victorian government should immediately consider reform.

Firstly, a truly independent police-complaint investigation mechanism is arguably the only way to secure adequate accountability of the police, which is necessary for the maintenance of the rule of law and the democratic legitimacy of the executive government.[257] Anything less than a fully independent mechanism creates a real risk that the efficacy of this accountability system will be undermined to the extent that it is unable to vindicate legitimate claims of serious abuse, therein ‘lay[ing] the foundations for the worst excesses of a police state’.[258] This risk has manifested itself repeatedly before,[259] and reform must not be postponed until it is necessitated by another catastrophic ‘system failure’.[260] Doing so runs the risk of engraining perceptions of bias and corruption so deeply in the public psyche that trust in the police, and in other institutions of government, is irreparably shattered. [261]

Secondly, an independent investigatory body would allow Victoria Police to function more efficiently. The creation of an independent complaints body, commanding its own budget separate to Victoria Police’s budget, would mean that resources currently expended on complaint investigations would be freed up and could be applied toward enhancing ‘front line service delivery and primary duties’.[262] The sequestering of the investigation process would also remove conflicts of interest within the force, releasing officers from the stress of trying to do their job while battling conflicting loyalty to their fellow officers.

Thirdly, the public tends to be dissatisfied with police-dominated complaint mechanisms, and appears to be firmly in favour of independent police-complaint investigations. In one study of 13 international jurisdictions, 71.3 per cent of complainants in police-dominated systems reported dissatisfaction with the system,[263] which was ‘not directly related to [the] substantiation [of their complaint]’.[264]

In Victoria, studies suggest that 62 per cent of complainants are dissatisfied with the current system, and that 78 per cent of the public are in favour of the establishment of an independent complaints system.[265] Victorians surveyed have reported feeling that the police are unwilling and unable to investigate themselves,[266] that such ‘investigators side with police, and that police attempt to dissuade complainants or refuse to take complaints’.[267] Similarly in Queensland, 60 per cent of surveyed complainants reported dissatisfaction with their experience,[268] while another survey of the British public found that 91 per cent of respondents strongly agreed that ‘serious complaints against police should be investigated by an independent body’.[269]

Fourthly, creating an independent mechanism responsible for investigating at least those complaints containing allegations of violations of the Covenant’s protected rights would enable the Charter to operate more effectively, and facilitate the achievement of its purpose – the protection and promotion of the rights it contains.[270]

Currently, although the Charter requires police officers to act in a way compatible with the Charter’s protected rights, and requires all decision makers to consider the Charter’s rights when reaching conclusions, it has little effect upon the complaints process.[271] This is because it does not contain a duty to investigate allegations that a person’s protected Charter rights have been violated, nor does it render invalid decisions made which fail to consider the Charter rights.[272] As there are no consequences for their violation, these provisions are thus robbed of meaningful operative effect, and leave complainants unable to turn to the Charter to ensure that their rights are protected.

Creating an independent police-complaint investigation mechanism, tasked with investigating complaints containing allegations of violations of the rights protected by the Covenant, would give these provisions effect because the Charter was modelled on the Covenant and the rights they protect are largely the same. Thus, discharging the duty to investigate violations of the Covenant’s rights would concurrently achieve independent investigation of the Charter’s rights. This would in turn promote the operation of the Charter by deterring police officers from violating the Charter’s protected rights, and by ensuring that complaint-investigators give due regard to the rights contained in the Charter when analysing complaints. This would simultaneously facilitate the realisation of the Charter’s purpose.

Finally, with Australia currently sitting on the Human Rights Council, Australia’s human rights record is being scrutinised by the world. Will Australian state governments be able to explain why, despite specific remonstration, they continue to fail to honour their obligations under the Covenant?[273]

For the reasons outlined above, Victoria must create an independent police complaints mechanism which complies with the Covenant’s duty to investigate.

Whether compliance is achieved by way of extensive reform of IBAC or by creating a new investigatory body is a question of policy. Regardless, the Covenant-compliant investigatory mechanism must be carefully crafted to ensure that it competently discharges the duty to investigate allegations of the Covenant’s right violations perpetrated by the police. To facilitate the identification of the necessary institutional qualities of Covenant-compliant bodies, it is essential to consider international examples of independent police-complaint investigation mechanisms which have been recognised as effectively discharging the duty. To this end, this article will now explore three model independent police-complaint investigation mechanisms.

The bodies selected are from Northern Ireland, New York, and Denmark. The Northern Irish and New York models were chosen to exemplify the qualities of established complaint bodies, while the Danish model was selected to demonstrate qualities of a nascent body.

The Police Ombudsman of Northern Ireland (‘PONI’) is the ‘gold standard’ of independent police-complaint investigation mechanisms.[274] Created in 2000[275] following the Hayes tribunal,[276] it ‘is now widely accepted as providing an effective mechanism for holding the police to account’.[277] This is reflected by its substantiation rates, depicted in Figure 1 below, which is currently at 24 per cent.[278]

Figure 1: Substantiation rates of police complaints in Northern Ireland, 1990–2017. Data in Appendix A.

PONI is a non-departmental public body,[279] headed by an Ombudsman appointed ‘by Royal Assent’ for seven year terms.[280] PONI is organisationally independent to the Police Service of Northern Ireland (‘PSNI’), and accountable to the Northern Irish Assembly.[281] It is required to accept guidance by the Department of Justice (‘DOJ’), from which it receives its grant of finance.[282] PONI has a central office in Belfast, but operates around the country.[283]

PONI has direct control over the police complaints system, being the only body which can legally deal with police complaints in Northern Ireland:[284] though complaints can be made to both PONI and the PSNI, all must be directed to PONI.[285] Complaints may be received by phone, email, online, or in person,[286] and PONI may also receive referrals from the DOJ and the Secretary of State.[287]

PONI is responsible for investigating all complaints against police made by members of the public,[288] and is empowered to consider complaints on a range of matters, from traffic incidents to serious criminal conduct.[289] When assessing complaints, it may determine that it is suitable for informal resolution, which will only occur if complainant consent is obtained.[290] If not so characterised, the complaint will be formally investigated.[291] Investigations are opened in relation to approximately 41 per cent of all complaints received,[292] and PONI also has the power to initiate its own investigations.[293]

Generally, PONI only investigates complaints containing allegations occurring in the previous year, though ‘there is no time limit’ in relation to the investigation of ‘grave or exceptional’ matters.[294]

PONI comprises 150 staff, including 120 professional civilian investigators.[295] Investigators include former solicitors, police from foreign jurisdictions, and ‘people with previous investigative experience ... such as Customs and Excise’,[296] and these investigators have extensive powers. For example, they can arrest people, seize evidence, interview officers and civilians, secure incident scenes, search premises, and have access to the full range of modern investigative techniques, including ‘forensics, DNA analysis, computer reconstructions and ballistics tests’.[297] Investigators also have access to round-the-clock video surveillance of police cars and stations,[298] police radio transmission tapes, and command and control logs.[299] PONI always requires fresh statements from police,[300] and PSNI officers cannot internally determine what is and is not relevant to an investigation.[301] Furthermore, police are legally obliged to ‘provide whatever information’ PONI investigators require in connection with investigations.[302] PONI also have a ‘critical incident’ response team to respond to specific emergency events, like service weapon discharges and deaths in custody,[303] and investigators will be at the scene anywhere in Northern Ireland within one and a half to three hours.[304]

About 94 per cent of investigations are dealt with within 90 days, and PONI tends to meet its timeliness policy guideline targets.[305] However, PONI has been accused of serious and unacceptable delays in relation to historic investigations.[306]

During the investigation process, PONI prioritises transparency. Its stated policy is to keep complainants and families informed throughout the process, making contact in the first three days[307] and then again at least every six weeks during the process, and aiming to reply to communications ‘within four working days’.[308] The Committee on the Administration of Justice however reports that PONI appears to have ‘an internal culture of not sharing information with families’ in relation to historical investigations.[309]

Upon completing an investigation, PONI may make disciplinary recommendations to the Chief Constable of the PSNI, who determines whether or not to take action against the officers concerned.[310] If the Chief Constable refuses to take action, PONI may direct them to do so.[311] PONI is also required to report matters to the Public Prosecution Service in instances of criminal conduct, who decides whether to prosecute the officer(s) concerned.[312]

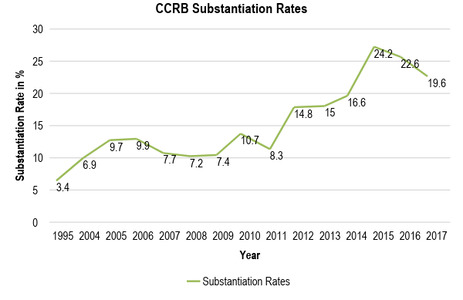

The Civilian Complaint Review Board (‘CCRB’) was established in 1953, becoming entirely independent of the New York Police Department (‘NYPD’) in 1993.[313] Although functionally inadequate for much of its history, recent reforms have caused a dramatic increase in effectiveness; reflected by increases in substantiation rates (see Figure 2).[314]

Figure 2: CCRB substantiation rates of police complaints 1995–2016. Data in Appendix B.

The CCRB comprises a 13-member civilian board appointed for fixed terms[315] who must be residents of New York, and who may not hold other employment.[316] Three of these members are appointed by the Police Commissioner, and only they may have previous law enforcement experience, including with the NYPD.[317]

The Board oversees a 180-member civilian staff,[318] none of whom may have a law enforcement background.[319] The staff is split into administrative and investigatory departments, and there is also a special administrative prosecution unit (‘APU’).[320]

The administrative team receives and processes complaints, which can be made at any time to the CCRB through a variety of mediums, including by telephone or voicemail.[321] The CCRB’s mandate is limited to complaints containing allegations of ‘excessive use of force, abuse of authority, discourtesy, or use of offensive language, including ... slurs relating to race, ethnicity, religion, gender, sexual orientation and disability’.[322] Complaints made to the NYPD will be referred to the CCRB if they fall within CCRB’s purview,[323] and if the CCRB receives complaints outside its purview, it refers them to the NYPD’s Internal Affairs Bureau (‘IAB’).[324]

The CCRB’s investigation team comprises 110 civilian investigators,[325] all of whom must undergo training at the CCRB Academy, which has ‘competency-based graduation requirements’, and who receive rigorous on-the-job training.[326] Investigators are overseen by managers with significant non-police investigatory experience,[327] and are guided by an investigation manual devised by experts.[328] Investigators have significant powers including subpoena powers,[329] the power to compel witnesses to attend examinations, and to compel the ‘production of such records and other materials as are necessary’.[330] There is also an ‘Evidence Collection Field Team’ similar to PONI’s critical response team.[331] Police officers must cooperate with investigators, providing whatever ‘records and other materials’ are requested, except those ‘that cannot be disclosed by law’.[332] Investigators have access to police department records,[333] facilitated by recent reforms to enhance document transfers with the IAB.[334] Investigators are also increasingly relying upon police body-camera video evidence, which has been credited with recent increases in substantiation rates.[335]

During the investigation process, investigators must contact the complainant within the first 48 hours. Complainants must also be interviewed in person,[336] which usually occurs within 22 days.[337] Investigators are required to regularly contact complainants, who can monitor the progress of their complaint online.[338] Complainant inclusion in the process is further supported by Freedom of Information legislation which allows easy access to CCRB’s records,[339] and the Data Transparency Initiative[340] which provides publicly accessible online information on complaints and complaint statistics. [341]

Investigations conducted tend to be prompt, conducted in an average of ‘140 days in 2016’, including processing time.[342]

Once an investigation is completed, the team submits a closing report to the Board who determines a finding of ‘substantiated’, ‘exonerated’, or ‘unfounded’ for each of the complaint’s allegations.[343] If substantiated, the Board may recommend disciplinary action to the Police Commissioner, who implements the Board’s recommendations 82 per cent of the time.[344] However, the Commissioner retains discretion to take final disciplinary action.[345]

Alternatively, the CCRB may institute administrative prosecution proceedings against the officer concerned via the APU, which is ‘responsible for prosecuting, trying and resolving the most serious misconduct cases’.[346] Such complaints will be determined by an administrative law judge, who may issue a finding of guilt and impose certain penalties.[347]

Since 2015 the CCRB has prioritised an aggressive outreach[348] strategy, tripling the number of community-based outreach units it runs and conducting frequent public presentations, designed to inform the community of the role of the CCRB and inform them of their rights.[349]

Den Uafhængige Politiklagemyndighed (‘DUP’) is the Danish Independent Police Complaints Authority, established in 2012.[350] Located in Aarhus, it is reasonably accessible given Denmark’s small size and the fact that investigators travel the country.[351]

DUP is an independent statutory body, organisationally independent from both the Danish Police and the nation’s Public Prosecutors.[352] It was deemed necessary to secure independence from both to eliminate structural dependence on the police by way of the Prosecutor, as the two work together closely.[353]

DUP is overseen by the Police Complaints Council, headed by a High Court Judge, whose members are appointed for four years by the Folketing (Parliament).[354] It has a very broad mandate to investigate and determine complaints about any ‘criticisable’ conduct of Danish police, including behavioural matters, criminal conduct matters, cases involving deaths or serious injury in police custody, and traffic matters.[355]

Complaints may be made personally or on another’s behalf[356] directly to the DUP online, by phone, or by post.[357] Complaints may also be made to the Danish police or to regional prosecutors, who ‘promptly’ refer all complaints to DUP.[358] DUP also has the power to initiate its own investigations,[359] and must investigate cases involving death or serious injury in police custody.[360]

Less serious complaints may be referred, with the complainants consent, to be resolved by local resolution with concerned officers.[361] Complaints deemed inappropriate for local resolution will be investigated,[362] though a time limit applies in relation to behaviour and traffic complaints: they must have occurred in the last six months. There is no such time limit in relation to criminal conduct complaints.[363]

DUP’s staff comprises 10 lawyers, 12 investigators, 8 administrators and a student.[364] The investigation team is composed of former Danish and Scandinavian police officers, with over 20 years’ experience.[365] Hiring former Danish police was deemed a necessary interim measure in the body’s nascent period to ensure that DUP had a suitably competent staff capable of processing intense case-workloads to a high professional standard while developing good practice frameworks, thereby allowing it to ‘demonstrate ... professional competence in carrying out investigations and to build up its trust’.[366] As DUP matures, it is executing plans to recruit and train non-police professional investigators.[367]

When investigating complaints, investigators ‘[handle] all aspects of inquiries and investigations’,[368] and have been recognised by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture[369] as having all ‘necessary powers and ... resources to carry out effective investigations into cases of alleged ill-treatment by police officers’.[370] For instance, it can ‘subpoena witnesses, request a forensic examination and arrest suspects’,[371] and police must disclose any information requested.[372] DUP has a 24 hour police hotline for serious incidents, and investigators can go anywhere in Denmark within 3–4 hours.[373] At incident scenes, investigators initiate their own investigation steps, conduct forensic investigations, consult with involved police officers, and implement strict separation polices to prevent debriefing.[374] DUP may request police assistance with ‘urgent matters’, like ‘securing a murder scene and obtaining a list of witnesses’.[375] DUP also engages in training with Scandinavian and European bodies.[376]

Investigations are bound by strict legal deadlines: DUP must decide complaints for misconduct within six months or a year for criminal cases, or it must notify parties of the reason for the delay and provide an expected decision date.[377] The average processing time for settled criminal cases in 2016 was 215 days,[378] and 241 days in 2017.[379] For behavioural complaints, in 2016 the average time was 108 days,[380] while in 2017 it was 105 days.[381]

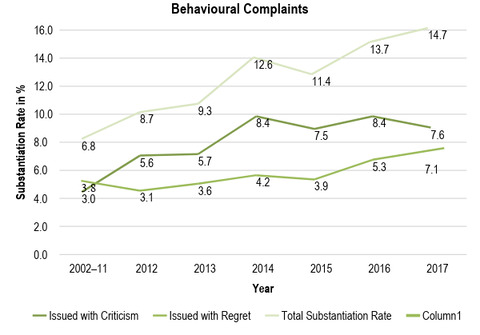

DUP examined 1545 complaints in 2016[382] and 1676 in 2017.[383] Complaints are divided into behavioural, criminal, traffic, and other.[384] Substantiation rates are divided according to this classification. Behavioural complaints can be either dismissed or revoked (unsubstantiated), or issued with regret or criticism (substantiated).[385] In relation to substantiated non-criminal matters, DUP will determine whether officers involved will face disciplinary sanction or not. Such decisions are final and cannot be appealed.[386]

For criminal complaints, substantiated outcomes include issue with accusations or regret, either of which may result in criminal proceedings.[387] Criminal complaints are forwarded to the Regional Prosecutor, who determines whether to prosecute.[388] Decisions of the Regional Prosecutor can be appealed to the Director of Public Prosecutions.[389]

The total substantiation rate for behavioural complaints in 2017 was 14.7 per cent (see Figure 3). A recent Copenhagen University evaluation said climbing rates are due to increasing thoroughness of investigations,[390] though it noted there was room for improvement and recommended requiring police to wear body cameras to further aid the rate.[391]

Figure 3: Substantiation rates of behavioural complaints against the Danish Police, 2002–17. Data in Appendix C.

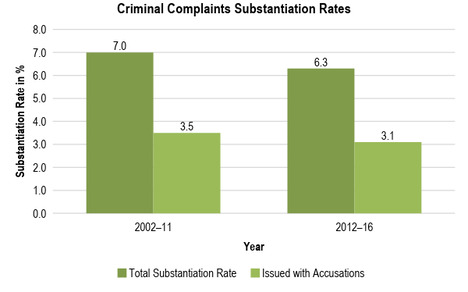

Interestingly, the rate of substantiation for criminal complaints has fallen slightly since the creation of DUP (see Figure 4). The Copenhagen University evaluation points out that DUP investigates more than double the number complaints as were investigated under the previous system, so the actual number of substantiated criminal complaints has more than doubled.[392]

Figure 4: Substantiation rate of criminal complaints against the Danish Police, 2002–16. Detailed data in Appendix D.

This article has argued that Victoria must create a competent, independent police-complaints mechanism, by virtue of the duty to investigate contained in article 2 paragraph 3 of the Covenant. It has done so by demonstrating that Victoria’s current police-dominated complaint mechanism is failing to discharge the duty.

Besides this pressing need for reform, there are a number of other reasons why Victoria should create an independent police-complaints mechanism. Crucially, doing so would enhance the operation of the Charter and would facilitate the achievement of its principal purpose.

As such, the time has come for Victorian policymakers to begin to consider how to fulfil Victoria’s obligations under international law by creating a truly independent complaints mechanism. Compliance with the Covenant may be achieved by way of extensive reform to IBAC, or by creating a new police-complaint investigation body, tasked with investigating at least those complaints which contain allegations of Covenant-protected right violations.

Whichever strategy is adopted, the body tasked with discharging the duty must be carefully crafted to ensure it is compliant with the Covenant’s requirements, as described by the framework outlined in Part II. To aid in the identification of the institutional qualities required to discharge the duty, this article examined three international examples of Covenant compliant independent police-complaint mechanisms. Based on this, this article proposes that the following elements must inform the development of Victoria’s independent police-complaints mechanism.

Firstly, the body must be organisationally and practically independent from the police. As such, it must not be part of the police, and nor should it be subject to its oversight. Furthermore, its investigators should not be hired from the ranks of former local police. Though the Danish strategy of hiring former police has the clear advantage of ensuring that investigators are technically competent, it is of paramount importance that the complaint mechanism is, and is perceived to be, entirely independent. Furthermore, there are equally effective ways to ensure investigatory competence: the approach adopted by the CCRB and PONI of hiring people with non-police investigatory backgrounds and of implementing rigorous investigatory training would ensure a suitable standard of technical competence is secured. Finally, it is crucial that the body is financially independent from the police.

Secondly, the body must have a very clear legal mandate. It should be granted direct control over the police-complaints system, allowing it to determine which complaints should be investigated with reference to clear statutory criteria, and it must be given exclusive responsibility for investigating all complaints containing allegations of violations of the rights protected by the Covenant. This would permit any complaints which do not amount to violations of the Covenant rights – for instance, rudeness or service delivery complaints – to be referred to the police to handle, which would alleviate the investigatory burden on the body.

Thirdly, the body should have the requisite capacity to conduct effective investigations. Thus, it must have a sufficiently large team of professional investigators, to ensure investigations are thorough and prompt. For instance, PONI has a team of 120 investigators to cater to a population of just over 1.5 million people and which received approximately 2797 complaints (comprising 4725 allegations) in 2016–17.[393] It is equally crucial that investigators have the necessary powers to allow them to conduct effective independent investigations, especially in relation to gathering evidence and compelling police cooperation. There should also be a rapid response team, akin to PONI’s critical incident team, to ensure that in cases of serious injury and death in custody fresh evidence can be acquired. Policymakers should also seriously consider requiring police officers to wear body cameras, and ensuring investigators have access to such video evidence.

Fourthly, there should be clear statutory timeframes governing investigatory timeframes and complainant contact requirements. It is critically important that investigations are sufficiently prompt, and that complainants are included in the process; including being afforded the right to submit evidence and being regularly updated on the investigation’s progress. The measures adopted by the CCRB should be considered, including the online complaint monitoring system and the Data Transparency Initiative, to create a more complainant-inclusive process.