|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

High Court of New Zealand Decisions |

Last Updated: 25 June 2011

JUDGMENT RECALLED AND REISSUED - SEE MINUTE 1 APRIL 2011.

IN THE HIGH COURT OF NEW ZEALAND WELLINGTON REGISTRY

CIV-2010-485-001955

UNDER the Trade Marks Act 2002

IN THE MATTER OF an appeal from the decision of the

Commissioner of Trade Marks dated 28

September 2010

BETWEEN THE MUIR ELECTRICAL COMPANY PTY LIMITED

Appellant

AND THE GOOD GUYS GROUP LIMITED Respondent

Hearing: 17-18 March 2011

Counsel: A H Brown QC and G W Hall for Appellants

K M Crooks and I Finch for Respondent

T G H Smith and S Kinsler for Commissioner

Judgment: 31 March 2011

Reasons: 1 April 2011

In accordance with r 11.15 I direct the Registrar to endorse this judgment with the delivery time of 2.30pm on the 31st day of March 2011.

RESERVED JUDGMENT OF GENDALL J

[1] This is an appeal by the owner of a registered trade mark in New Zealand

(Muir Electrical) against a decision of the Commissioner of Trade Marks declining to revoke acceptance of an application for a similar or identical word mark by the

THE MUIR ELECTRICAL COMPANY PTY LIMITED V THE GOOD GUYS GROUP LIMITED HC WN CIV-2010-485-001955 31 March 2011

respondent (The Good Guys Group). The appeal is novel in the sense that it involves issues that have not come before the New Zealand or Commonwealth courts in the past.

[2] Associated with the substantive appeal were applications by the Good Guys Group and the Commissioner, to strike out the appeal on the basis that it is an abuse of process, and that no jurisdiction existed to entertain the appeal.

[3] The Court has heard both the application to strike out and the substantive appeal because the issues of jurisdiction are not easily separated from merits. The preferable course is for the strike out question to be dealt with as a threshold issue on the appeal and, if rejected, for the Court to go on and determine the substantive appeal.1 Because of the interconnected nature of the arguments, I propose to deal with the strike out issues in the context of the overall merits appeal.

Background

[4] Muir Electrical is a company registered in Australia, that operates retail premises in Auckland selling whiteware, electronic and electrical goods. It owns a series of registered trade marks in New Zealand for the word mark ―THE GOOD GUYS‖, in various classes on the Trade Marks Register. For the purpose of the present proceedings, the relevant mark is in Class 35 for retailing services in relation to electronic electrical goods and whiteware. Muir Electrical’s registrations exist from 30 July 2002 and 14 June 2006.

[5] The Good Guys Group is a group of companies, which operate in the area of door-to-door retail services. It has traded under the name ―THE GOOD GUYS‖ in New Zealand since 1993, retailing a wide variety of product and a ―Christmas Club‖ type business, and has expanded its range of goods from clothing and Manchester items to furniture, whiteware and home appliances.

[6] The Good Guys Group applied on 16 June 2006 for registration of the word trade mark comprising ―THE GOOD GUYS‖ in Class 35 (retailing services in

1 See Association of Dispensing Opticians of New Zealand Inc v The Opticians’ Board [2001] 1

NZLR 158 and Commissioner of Inland Revenue v Dick (2000) 14 PRNZ 378.

relation to electronic goods and whiteware). The application was for an identical trade mark for similar goods or services to that of Muir Electrical and the Commissioner, unsurprisingly, objected to the registration of the mark (No. 749713). The Good Guys Group were not able to overcome the objections, so the application was not accepted and was held in abeyance. During that period, proceedings were commenced by the Good Guys Group to remove Muir Electrical’s registrations or applications. The outcome of which was that Muir Electrical’s marks remained on the register.

[7] In February 2010, the Good Guys Group requested that IPONZ take its application out of abeyance, and on 14 June 2010 a submission was made to the effect that the original application 749713 should be accepted under s 26(b) of the Trade Marks Act 2002, on the basis of honest concurrent use and/or other special circumstances existing. A statutory declaration by the Managing Director of the Good Guys Group, Mr Graham Dorward, was submitted. The declaration essentially contended that there had been honest and concurrent use, without instances of confusion, and that the first use of the appellant’s mark was in 1993 but not specifically referring to when that mark may have been used in association with whiteware and electronic goods (Class 35). IPONZ advised that it would be prepared to allow the application to proceed to acceptance if it was limited in specification to services provided door-to-door or in relation to a Christmas Club scheme, which limitation the Good Guys Group accepted.

[8] In its assessment process IPONZ described the duration of current use as

―three years and eleven months‖ and that ―continuous use of the applicant’s mark in the market place .... is fairly short use, but could be sufficient.‖ It concluded on

―likelihood of confusion‖ as being ―high‖ but that there was a ―potential specification limitation to door-to-door retail services and Christmas Club type retail services‖. As mentioned, that limitation was accepted by the Good Guys Group. Whether instances of confusion in fact had occurred, the assessment referred to the

―specific statement and statutory declaration that there have been no instances of confusion‖. This related to Mr Dorward’s declaration that he was ―not aware of any instances of confusion between the applicant’s mark and the sighted marks‖. The assessment records that the ―honesty or otherwise of the concurrent use‖ was

―mostly not at issue‖. The Commissioner accordingly accepted the trade mark

application.

[9] In the meantime, and before acceptance of the application, the solicitors for Muir Electrical (Messrs Buddle Findlay) wrote to the Commissioner asking that the proposal for acceptance be withdrawn because of ―error or omission by the office based on the material currently before it‖. That letter of 27 July 2010 made detailed submissions, assertions and allegations, generally to the effect that the declaration of Mr Dorward was incorrect and untrue when recording that there had been honest concurrent use of the mark for whiteware and electronics since 1993 and that there had been no instances of confusion. Buddle Findlay contended that contradictory facts existed. The Good Guys Group challenged the approach and allegations made on behalf of Muir Electrical, and contended that Muir Electrical was attempting to enter into ―opposition by correspondence‖.

[10] On 17 August 2010 IPONZ advised both Muir Electrical and the Good Guys

Group that it had:

carefully considered the concerns raised by Buddle Findlay in relation to the applicant’s evidence submitted to the office .... [and] had regard to the comments made by [solicitors for The Good Guys Group] in response.

....

Having assessed all information supplied to the office, we maintain the position that if the applicant agrees to amend the specification the application would be in order for acceptance under s 26(b).

As the office has made its determination on this matter, should the Muir Electrical Company Pty Ltd have further concerns it has the right to have them heard via the Opposition process, if and once the application proceeds to acceptance.

[11] On 20 August 2010 Muir Electrical’s solicitors endeavoured to reargue their contentions.

[12] On 25 August 2010 the Good Guys Group agreed to the specification limitation sought by IPONZ. So the application was accepted on 27 August 2010.

[13] Undeterred, Buddle Findlay on behalf of Muir Electrical again wrote to

IPONZ on 23 September 2010 in a lengthy letter, its purpose being said:

to draw your attention to some serious irregularities concerning application

749713 and the evidence on which IPONZ has accepted the application. We believe that IPONZ has been misled by certain statements made in the

application and supporting declarations.

It sets outs a number of the reasons, and requests that the Commissioner withdraw the acceptance.

[14] The Commissioner declined to do so. He wrote to Buddle Findlay, and also solicitors for the Good Guys Group on 28 September 2010, referring in part to the submissions presented by Buddle Findlay and that ―the matters raised were serious‖, and stated in part:

We agree that the following allegations of your client are of a serious nature;

![]() The applicant’s evidence is intentionally

misleading because it falsely gives the impression that the applicant first

started using the subject mark for all of its specified services

back in January 1993 ...

The applicant’s evidence is intentionally

misleading because it falsely gives the impression that the applicant first

started using the subject mark for all of its specified services

back in January 1993 ...

![]() There are three significant pieces of evidence that

contradict the applicant’s claim that it was not aware of any instances

of

actual confusion between the marks ...

There are three significant pieces of evidence that

contradict the applicant’s claim that it was not aware of any instances

of

actual confusion between the marks ...

![]() There has been no honest

concurrent use ....

There has been no honest

concurrent use ....

Given the seriousness of the allegations, it is clear that both parties should be given the opportunity to be heard on the matter. However, examination is not an inter-party process and does not provide IPONZ with the means to resolve disputes between the parties.

The opposition process is therefore the appropriate forum for this matter.

Review of application

Furthermore, as noted in our previous letter of 17 August 2010 we have already reviewed our file. It does not appear that the Office accepted the mark because of an ―error or omission‖. The Office duly considered the applicant’s evidence before accepting the mark for registration on the basis of honest concurrent use. Any question at this point in time as to the integrity of that evidence does not constitute an ―error or omission‖ on the part of the Office.

As there does not appear to have been an ―error or omission‖ on the part of

the Office we cannot revoke acceptance under s 42(1)(a).

[15] On 5 October 2010 Muir Electrical filed its notice in this Court to appeal the

Commissioner’s decision of 28 September 2010.

[16] For completeness, I add that solicitors for the Good Guys Group on

5 October 2010, wrote to IPONZ recording that:

We take serious issue with the allegations set out in Buddle Findlay’s letter. However, we agree with the Office’s approach, that the appropriate forum for dealing with such matters is any opposition proceeding brought by Muir Electrical Company Pty Ltd.

Issues

[17] In endeavouring to distil the issues arising on this appeal, I think the following matters arise:

(a) Was the determination of the Commissioner of 28 September 2010 a

―decision‖ or a (non-appealable) ―refusal to make a decision‖?

(b) Is Muir Electrical a party ―aggrieved‖ by that ―decision‖?

(c) Was it a ―decision‖ in respect of which an appeal lies under s 170 of

the Trade Marks Act 2002?

(d) Does Muir Electrical have the right to appeal to the Court from that

―decision‖?

(e) Assuming it to be a decision from which Muir Electrical is entitled to

appeal, was the Commissioner’s determination wrong on the merits?

[18] Consideration of these issues may overlap. I will deal with them later in not precisely the order outlined.

Statutory provisions

[19] I note the following provisions of the Trade Marks Act 2002.

General

3 Purposes

The purposes of this Act are to–

(a) more clearly define the scope of rights protected by registered trade marks; and

(b) simplify procedures for registering a trade mark in order to reduce costs to applicants and to reduce business compliance costs generally; and

...

4 Overview

In this Act,–

(a) ...

(b) the main rights attaching to a registered trade mark (for example, the exclusive rights to use the registered trade mark) are set out in section 10:

(c) when a trade mark is registrable is set out in section 13. Other provisions relating to the registrability of trade marks are set out in sections 14 to 30:

(d) the process for registering a trade mark is contained in Part 3:

(e) remedies and offence provisions relating to the infringement of a registered trade mark, border protection measures concerning an infringing sign that is applied to goods in an overseas country, and general provisions about legal proceedings and appeals under this Act, are set out in Part 4:

...

Examination, acceptance and registration of an application

39 Examination of application

The Commissioner must examine an application in order to determine whether it complies with the requirements of this Act.

40 Acceptance of application

The Commissioner must, subject to any conditions the Commissioner thinks fit, accept an application that complies with the requirements of this Act.

42 Revocation of acceptance of application

(1) The Commissioner may revoke the acceptance of an application before the trade mark to which the application relates is registered if the Commissioner is satisfied that–

(a) the application was accepted because of an error or omission made by the Commissioner; or

(b) another application that relates to the trade mark has priority under section 36.

(2) If the Commissioner revokes the acceptance of an application,–

(a) the application is to be treated ass if it had not been accepted;

and

(b) section 39 again applies to the application.

45 Applicant must be notified of grounds, etc, of conditional acceptance or rejection of application

The Commissioner must, if required to do so by an applicant, state in writing the grounds for the Commissioner’s decision and the materials used in arriving at the decision.

Part 3

Process for obtaining registration of trade mark and other matters

Appeals

170 Appeal in relation to Commissioner’s decisions

A person who is aggrieved by a decision of the Commissioner under this Act may appeal to the court.

173 Determination of appeals

In determining an appeal, the court may do any of the following things:

(a) confirm, modify, or reverse the Commissioner’s decision or any part

of it:

(b) exercise any of the powers that could have been exercised by the

Commissioner in relation to the matter to which the appeal relates:

....

Appellant’s submissions

[20] Muir Electrical says it is entitled to pursue this appeal as an ―aggrieved person‖ within s 170 of the Act. It contends that the Commissioner’s refusal to revoke the acceptance of the Good Guys Group application was a ―decision‖; and it is ―aggrieved‖ by that decision, as the owner of a similar or identical trade mark.

[21] Muir Electrical emphasises the legal limits on acceptance and registration. Section 39 provides that acceptance of the application can only occur if the Commissioner, after examining an application, determines whether it complies with the requirements of the Act. Section 17(1) provides that the Commissioner must not register as a mark where use of it would likely deceive or cause confusion or the use is contrary to law. Section 25 provides that the Commissioner is prohibited from registering a mark if it is identical to another belonging to a different owner already on the Register, and I have no doubt that is why the initial application was rejected under s 40.

[22] Counsel argues that simply advancing ―honest concurrent use‖ as the basis for acceptance of such an application cannot thwart compliance with the requirements of the Act, as contained in s 25 and elsewhere. Counsel accepts that honest concurrent use is a special exception, but acceptance of the application requires careful and proper scrutiny, in terms of the leading authority of Re Pirie.2

This emphasises five factors to be taken into account in the exercise of the unfettered

discretion.

[23] Counsel submits that it was entirely in order for Muir Electrical to raise with, or make submissions to, the Commissioner challenging acceptance of the application on the basis of honest concurrent use.

[24] Counsel advise that there is no previous equivalent of s 42(1) relating to revocation of acceptance in the earlier New Zealand Trade Marks Act 1953, but that the section mirrors the revocation of acceptance provision under the Australian Trade

Marks Act 1995 (prior to its amendment in 2006).

2 Re Pirie (1933) 50 RPC 147 at 159 (HL).

[25] Although usually it is the Commissioner or IPONZ that triggers exercise of the power of revocation, it is permissible for some other party to request the Commissioner to exercise that power. Counsel gives two Australian examples, where owners of registered marks have objected to the acceptance of an application for a similar mark as a result of which there has been a revocation of acceptance.

These are Re Application by Channel Four Television Corporation3 and

Re Application by Sartek Pty Ltd.4

[26] Counsel acknowledged that the crucial words are whether there has been

―error or ―omission‖ as referred in s 42(1)(a). As discussed in the Australian decision, Re Remington Products Inc:5

―acceptance in error‖ must thus be restricted to mean acceptance of a trade mark where the acceptance officer is either mistaken as to the facts or in ignorance of the facts. It cannot be extended, however, to the reversal of a decision to accept when there is no more than a change of opinion as to the way the facts should be interpreted.

[27] In this case counsel submits that Muir Electrical supplied the Commissioner with evidence or facts which ought to have satisfied him on the balance of probabilities that the application was accepted because of errors or omissions made at the time of acceptance. The evidence or ―facts‖ are those set out in the various

letters from Buddle Findlay. The alleged errors are that:

![]() direct evidence was not provided by the Good Guys Group as

to the continuous use of the mark when retailing

whiteware/electronic/electrical

direct evidence was not provided by the Good Guys Group as

to the continuous use of the mark when retailing

whiteware/electronic/electrical

goods;

![]() in taking a period of three years eleven months as

the duration of concurrent use (for the relevant specification) the

examiner

was mistaken

in taking a period of three years eleven months as

the duration of concurrent use (for the relevant specification) the

examiner

was mistaken

as to the facts;

![]() the examiner was mistaken as to the

likelihood of confusion or its degree,

the examiner was mistaken as to the

likelihood of confusion or its degree,

as the examiner did not have available evidence of actual confusion;

3 Re Application by Channel Four Television Corporation [2007] ATMO 6; (2007) 72 IPR 163 (IP Australia

Hearings Office).

4 Re Application by Sartek Pty Ltd (1991) 22 IPR 317 (IP Australia Hearings Office).

5 Re Remington Products Inc (1990) 18 IPR 251 at 254 (IP Australia Hearings Office).

![]() the examiner was in error in accepting honesty of

concurrent use (recording it as ―mostly not in issue‖).

Evidence

of the Good Guys Group’s ―knowledge‖ of Muir

Electrical’s registrations from October

the examiner was in error in accepting honesty of

concurrent use (recording it as ―mostly not in issue‖).

Evidence

of the Good Guys Group’s ―knowledge‖ of Muir

Electrical’s registrations from October

2002 was not before the examiner and was a fundamental to the

assessment of honesty.

[28] Counsel submitted that such mistakes or ignorance of facts involved a discovery after acceptance that the examiner was wrong, and involved a necessary finding about the integrity of the facts upon which reliance was placed at the initial examination.

[29] Counsel submitted that the Commissioner was wrong to avoid determination of that contest on these factual matters, because there clearly was, and remains, a contest and he was wrong to conclude that any contest had to be dealt with inter- parties in opposition proceedings. Counsel says the Commissioner closed his mind to considering ―new evidence‖ that might show there was a mistake on the facts. Relying upon the Channel Four case, counsel submitted that it was in the public interest that the application be returned for re-examination so that the owner of the trade mark might be satisfied that its pre-existing registrations and prior rights had been suitably considered, and leaving that uncorrected would put Muir Electrical to the substantial cost of opposition proceedings, when it was entitled to the protection of s 25(1).

[30] In the course of argument, counsel for Muir Electrical conceded that if the Commissioner proposed to revoke acceptance, Muir Electrical did not have an express right to be heard in any hearing on revocation that was required to be held under the regs 71 and 72 of the Trade Mark Regulations 2003.

[31] Regulation 71 provides that the Commissioner must notify an applicant if the Commissioner proposes to revoke acceptance; the notification must specify grounds for revocation; and the notification must advise the applicant that they may require

―a hearing‖ within the time limit provided. Regulation 72 then provides the Commissioner must hold a hearing if required and then ―decide whether to revoke acceptance of the application only after hearing the applicant‖. If the

Commissioner’s revocation was confirmed then of course Muir Electrical would have succeeded. If, however, it was not confirmed then they would be left with participation through the opposition proceedings. But, as counsel said, Muir Electrical would have to ―take its chances‖ of any revocation, being confirmed or not, after such ―one party‖ hearing.

[32] I record that the submissions on behalf of the appellant (encompassing many pages and paragraphs of careful argument) ranged very much wider than that summary and I mean to them no disservice by not expanding on them in any greater detail. But I hope that the foregoing largely encapsulates and summarises the essence or main points of the argument advanced on behalf of Muir Electrical.

Submissions on behalf of the Commissioner

[33] The Commissioner did not enter into argument, as he could not, as to the merits or substantive rights of the parties. But, on his behalf, it was argued that the structural integrity of the examination and opposition processes under the Act had to be preserved, and that this appeal undermined that process. The Commissioner supported the application to strike out by the Good Guys Group because, it was argued that, with regard to the Act’s purpose and scheme, there was no jurisdiction

for the Court to entertain the appeal because:

![]() The Commissioner’s refusal to revoke acceptance was

not a ―decision‖ so

The Commissioner’s refusal to revoke acceptance was

not a ―decision‖ so

as to engage the statutory procedure for appeals for the purposes of s 170 of the Act.

![]() In the examination phase of this application process Muir

Electrical was not a person ―aggrieved‖ for the purpose of

s 170 of

the Act (although of course for appeal purposes it clearly would be a person

aggrieved after

In the examination phase of this application process Muir

Electrical was not a person ―aggrieved‖ for the purpose of

s 170 of

the Act (although of course for appeal purposes it clearly would be a person

aggrieved after

participation in the opposition process).

![]() It was an abuse of the Court’s processes

because, in the event that Muir Electrical loses this appeal, it intends

to

have a second bite of the cherry and the Court’s ought not to permit

that.

It was an abuse of the Court’s processes

because, in the event that Muir Electrical loses this appeal, it intends

to

have a second bite of the cherry and the Court’s ought not to permit

that.

![]() An existing proceeding relating to the same subject matter

is on fact – that is the opposition to registration. (I note

however that

this has had to have been formally undertaken by Muir Electrical pending

determination of the appeal because of time

limitation restraints). Counsel

argued that because of the statutory right to engage in the opposition process

being adopted, dismissal

or striking out of the appeal will have no substantial

effect on the rights or interests of Muir Electrical as they relate to the

An existing proceeding relating to the same subject matter

is on fact – that is the opposition to registration. (I note

however that

this has had to have been formally undertaken by Muir Electrical pending

determination of the appeal because of time

limitation restraints). Counsel

argued that because of the statutory right to engage in the opposition process

being adopted, dismissal

or striking out of the appeal will have no substantial

effect on the rights or interests of Muir Electrical as they relate to the

ultimate issue the registrability of the application.

[34] So, for those reasons, the Commissioner argued that the Court should strike out the appeal as being without jurisdiction and an abuse of process.

Submissions on behalf of the Good Guys Group

[35] Counsel joined with the Commissioner’s submissions supporting the formal strike out application, on the basis that there was no jurisdiction for the Court to entertain the appeal. Further, counsel contended that:

![]() Muir Electrical had no right to require the Commissioner to

consider and deal with its request that acceptance of the Good Guys

Group

application

Muir Electrical had no right to require the Commissioner to

consider and deal with its request that acceptance of the Good Guys

Group

application

be revoked.

![]() The purpose of the 28 September letter was to advise Muir

Electrical’s counsel of the correct procedure through which it

could raise

its claims as against the Good Guys Group through the opposition procedure.

Counsel says the letter effectively advised

that the Commissioner had no

jurisdiction to exercise his discretionary power, not being satisfied that the

application was accepted

because of the Commissioner’s error or

The purpose of the 28 September letter was to advise Muir

Electrical’s counsel of the correct procedure through which it

could raise

its claims as against the Good Guys Group through the opposition procedure.

Counsel says the letter effectively advised

that the Commissioner had no

jurisdiction to exercise his discretionary power, not being satisfied that the

application was accepted

because of the Commissioner’s error or

omission.

![]() Interpreting the 28 September letter as a

―decision‖ would enable any third party to intervene in the

preliminary

examination process by demanding a response to a request to revoke

and appealing any refusal to accede to that request.

Interpreting the 28 September letter as a

―decision‖ would enable any third party to intervene in the

preliminary

examination process by demanding a response to a request to revoke

and appealing any refusal to accede to that request.

![]() Muir Electrical was not an ―aggrieved person‖

for the purposes of s 170

Muir Electrical was not an ―aggrieved person‖

for the purposes of s 170

because it had no right to receive a determination from the Commissioner as to whether acceptance should be revoked.

![]() Allowing the appeal to proceed would undermine the scheme

of the Act, which envisages that opposition is the required method for

third

parties to challenge applications, and by allowing an appeal right would enable

a third party to twice challenge acceptance

of a trade mark application; first

by appeal to the High Court on acceptance; and then (not through participation

in the subsequent

hearing process)6 but by opposition

post- acceptance which carries with it the right of further appeal to

the

Allowing the appeal to proceed would undermine the scheme

of the Act, which envisages that opposition is the required method for

third

parties to challenge applications, and by allowing an appeal right would enable

a third party to twice challenge acceptance

of a trade mark application; first

by appeal to the High Court on acceptance; and then (not through participation

in the subsequent

hearing process)6 but by opposition

post- acceptance which carries with it the right of further appeal to

the

High Court.

Discussion

General

[36] The starting point in any discussion over the several issues in the case must be the statutory scheme and framework. Any analysis of it, as it relates to applications for registration of trade marks, and oppositions to registration, must recognise the principles of the Act. The legislative framework is recorded in detail by Lang J in an earlier case involving the parties, The Muir Electrical Company Pty

Ltd v The Good Guys Group Ltd.7 It is not necessary to repeat in full what was said.

I adopt it. Lang J contrasts the procedure with applications to revoke or challenge registered marks, with challenges to registration after an application has been accepted and advertised. Once the Commissioner decides an application is registrable as complying with the requirement of the Act it must, subject to any conditions to be imposed, be accepted. That does not mean it is then registered. Counsel for Muir Electrical correctly contends that, in the absence of opposition, it

will be registered. But that does not mean acceptance equals registration which is

7 The Muir Electrical Company Pty Ltd v The Good Guys Group Ltd HC Auckland CIV 2009-

404-4965, 18 December 2009 at [8] – [15].

clear from s 42 which envisages revocation by the Commissioner ―before the trade mark to which the application related is registered ...‖.

[37] Once the application is accepted, advertising occurs and persons who wish to oppose registration have three months in which to file a notice of opposition. If this occurs, the applicant is required to file a counter-statement failing which the application is deemed abandoned.

[38] Thereafter, evidence is filed by the person opposing (or he may withdraw) the opposition and the applicant files evidence, with a right of reply evidence then existing. An applicant or opposing party may request a hearing which must then occur before the Commissioner determines the outcome of the opposition. Section 49 provides the Commissioner must hear the parties, if required; consider the evidence; and determine whether the trade mark is to be registered.

[39] These procedures all arise under Subpart 3 – ―Opposition to application‖ (and Part 8 of the Regulations), and it is clear that registration does not occur until this process is completed.

[40] There are separate statutory/regulatory procedures for applications before registration, revocation of acceptances, and opposition to registration:

![]() Procedures relating to applications prior to opposition are

contained in

Procedures relating to applications prior to opposition are

contained in

―Subpart 2 – Applications‖ of the Act and Part 7 of the Regulations, and ss 42 – 45 and regs 71 – 72 deal with ―Revocation of Acceptance‖.

![]() Later opposition procedures are contained in Subpart 3 of

the Act and

Later opposition procedures are contained in Subpart 3 of

the Act and

Part 8 of the Regulations.

[41] Where the Commissioner ―proposes to revoke acceptance of the application under s 42, reg 71 applies and he/she must notify the applicant who may respond and require a hearing. Only after that – and subject to any appeal right of the applicant – does revocation by the Commissioner under s 42 occur, and the application is treated as having not been accepted and s 39 applies.

[42] A third party may be able to bring to the Commissioner’s notice or attention, facts/matters/submissions as to why acceptance should be revoked by the Commissioner under s 42. But they have no right to be heard or otherwise participate in a later reg 72 hearing. Counsel for Muir Electrical do not assert otherwise. That hearing arises because the applicant requires it as it is put in jeopardy by the proposal by the Commissioner to revoke. It may be that the Commissioner affords a third party – who has the benefit of revocation because it has a similar registrable mark – the opportunity to be heard – as happened in In Unilever

Plc v Commissioner of Trade Marks,8 but that is very different to the situation where

there is no hearing because there is no proposal to revoke.

[43] In Unilever Plc Wild J was dealing with an appeal against revocation of acceptance for registration of Unilever’s mark (DOVE SUMMER GLOW), on the basis that another related application (Neutrogena’s SUMMER GLOW) had priority under s 36 (s 42(1)(b)). It was Unilever’s appeal, not Neutrogena’s, and it could not be questioned that Unilever had that right. Wild J noted as background that Unilever exercised its right under reg 72 of the Trade Mark Regulations 2003 to request a hearing upon written submissions, the Commissioner accepted that Neutrogena, as an ―affected‖ party, should have been given notice of that hearing and an opportunity to file submissions. But that is not an express right under reg 72, and the issue arises only if the hearing is requested by the applicant. I do not consider that a third party has status to request a ―revocation hearing‖; the procedure does not arise unless the Commissioner proposes to revoke, and the applicant exercises its express rights under regs 71 and 72. I note also that the scope of s 170 was not discussed in that case: jurisdiction was not questioned; and Unilever, as the appellant, accepted that the appeal against a discretion was on limited grounds (error of principle, omitted relevant consideration or took into account irrelevant considerations, or plainly wrong).

[44] If the proposal to revoke (because that is all it is at this stage) leads to revocation after a hearing, there can be no doubt that the applicant, as a party

―aggrieved‖ by that decision, may appeal under s 170. If revocation does not result,

a third party, having not participated in the hearing, could not appeal that decision.

8 Unilever Plc v Commissioner of Trade Marks HC Wellington CIV 2006-485-1208, 20 July 2007.

So, the Good Guys Group ask, why should the third party have the right to appeal where the Commissioner earlier decides not to propose revocation and not to initiate this procedure?

Dealing further with specific issues

Was the determination of 28 September 2010 a “decision” or simply “a refusal to make a decision?”

[45] I do not agree that the Commissioner’s refusal to accede to Muir Electrical’s request to revoke acceptance was not a ―decision‖. Although the Commissioner’s decision may not have been a decision ―not to revoke‖, it was a decision not to propose to revoke so as to invoke the required procedures. It was a deliberate decision, or refusal to do what Muir Electrical wanted. Whether Muir Electrical has the right to challenge that decision by appeal to this Court is another matter.

[46] A request to exercise the power of revocation may be made by a third party if it can point to information which the Commissioner ought to have had, and because he/she did not have that, an error or omission was made in accepting the application, or another application has priority under s 36. For example, this occurred in the Australian cases of Re Application by Sartek Pty Ltd and Re Application by Channel Four Television Corporation, those being cases where revocation of the acceptance occurred. The real issue is whether, on a third party’s application where revocation is declined, that party has the right to appeal that decision to this Court. The party may be aggrieved – it has not obtained the outcome it sought – but is it a decision that gives it any standing to appeal?

[47] The answer to that question must be whether a right of appeal arises under s 170 if the Commissioner decides not to revoke an acceptance.

Was Muir Electrical a party “aggrieved” by the decision within s 170 of the Act so as to be entitled to appeal?

[48] A ―person aggrieved‖ [does] not mean a person who is disappointed of a

benefit which he might have achieved if some other decision had been made, but:9

A ―person aggrieved‖ must be a man who has suffered a legal grievance, a man against whom a decision has been pronounced which has wrongfully deprived him of something, or wrongfully refused him something, or wrongfully affected.

[49] As mentioned, Muir Electrical may be aggrieved in the usual sense of the word, because their request and submissions were declined by the Commisisoner. But they can only be ―aggrieved‖ for the purpose of the Act if the decision is something on which the legislative envisaged they could appeal. I accept that such a statement could be seen as circular – i.e. what comes first? So, ―aggrieved‖ as it may be, the answer to this question has to be determined by consideration of the next two issues – which can be dealt with together.

Did the Commissioner make a decision in respect of which an appeal lies to this Court under s 170 of the Act and, if so, does Muir Electrical have such right of appeal?

[50] The decision challenged by Muir Electrical is only a refusal to propose revocation. A hearing could only be requested by the applicant, the Good Guys Group, if the Commissioner proposed to revoke. The decision, despite Muir Electrical’s contention, was not to refuse to revoke. It was a refusal to institute a process in which Muir Electrical agrees it could not participate at that stage. The Good Guys Group, naturally, had nothing to appeal against – but could not have done so if the Commissioner had proposed to revoke because the prescribed procedures had to follow. Revocation, entitling it to appeal, arises only if the Commissioner is ―satisfied‖ of the s 42(1) factors after the process envisaged by regs 71 and 72.

[51] These provisions combine to create a three step process. The Commissioner must determine:

Step 1 ―error or omission‖ or no ―error or omission‖, issue dismissed

|

Step 2

|

revocation proposed,

|

or

|

revocation not proposed, regs 71 & 72

|

|

Step 3

|

regs 71 & 72

acceptance revoked

|

or

|

do not apply, issue dismissed

acceptance not revoked, issue dismissed

|

Thereafter Step 1 could be said to be a jurisdictional stage, and Step 2 a preliminary decision (based on the examiner’s discretion) – whatever they are called, together, they constitute a threshold that must be reached before the applicant is even advised of the process. Only after Step 2 do the express natural justice protections (in regs 71 and 72) come into play. That supports a contention that Step 3 is the only decision of significance.

[52] There is also the distinction between the applicant and any other party. The express natural justice protections in regs 71 and 72 only favour the applicant. Section 42 and regs 71 and 72 at no stage recognise that there are any other formally interested parties in this process. This is in direct contrast to s 65, where ―an aggrieved person‖ may apply to the Commissioner or the Court for the revocation of the registration of a trade mark.

[53] More broadly, the scheme of the Act envisages two distinct phases. The first is the acceptance and examination of applications, with the applicant and Commissioner only being involved. The Commissioner must accept applications that comply. There can be received – and considered – many sources, and the Commissioner may reject non-complying applications. If the Commissioner accepts an application he may still, nevertheless, later become satisfied in terms of s 42 that it should not have been accepted by reason of error or omission or another application has priority. But at that stage the process remains, one as between the Commissioner and the applicant. If the Commissioner does not propose to revoke acceptance because he/she is not ―satisfied‖ with the s 42 criteria then of course no hearing as between applicant and Commissioner occurs. The trade mark application moves into the second stage, namely the ―opposition‖ process. I accept the submissions made on behalf of the Commissioner that the advertisement signals the beginning of that process and it is at that stage that evidence, submissions, and direct

involvement opposing the registration of the mark occurs. Appeal rights follow at the suit of an ―aggrieved person‖.

[54] The meaning of an ―aggrieved‖ person must be ascertained from the Act in which it is contained10 and within the statutory framework of this Act and regulations I do not accept it includes, for the purposes of appealing to the High Court, persons who wish to contest a decision of the Commissioner refusing to ―propose‖ to invoke the mechanism for revocation. Section 172 concerns the hearing of appeals in the High Court and although I note that subs (3) speaks of ―an appeal against the

acceptance of an application or the registration of a trade mark ....‖, within the statutory context this can only refer to challenges arising out of the priority of applications under ss 34 – 36. The Commissioner is required under s 35 to determine each application according to its order of priority and obviously, appeals dealing with priorities of separate applications are available.

[55] It is relevant that the ―aggrieved person‖ references in the Act, other than

s 170, all apply to post-registration situations, namely:

![]() s 62 – the Court or the Commissioner may, on the

application of an aggrieved person or on the Commissioner’s own motion,

make an order that cancels or alters the registration of a trade mark on the

ground of

s 62 – the Court or the Commissioner may, on the

application of an aggrieved person or on the Commissioner’s own motion,

make an order that cancels or alters the registration of a trade mark on the

ground of

failure to comply with a condition;

![]() ss 63 and 64 – the Commissioner may, on the

application of an aggrieved

ss 63 and 64 – the Commissioner may, on the

application of an aggrieved

person or on the Commissioner’s own motion, make an order that cancels

or alters the registration of a trade mark on certain grounds;

![]() s 65 – an aggrieved person may apply to the

Commissioner or the Court

s 65 – an aggrieved person may apply to the

Commissioner or the Court

for the revocation of a registration of a trade mark; and

![]() s 73 – the Commissioner or the Court may, on the

application of an aggrieved person (which includes a person who is culturally

aggrieved), declare that the registration of a trade mark is invalid.

s 73 – the Commissioner or the Court may, on the

application of an aggrieved person (which includes a person who is culturally

aggrieved), declare that the registration of a trade mark is invalid.

[56] Although, inevitably an applicant who contests a proposal to revoke by the Commissioner and fails, would be an aggrieved person for the purposes of an appeal under s 170. But I reject the proposition that a third party who asks the Commissioner to ―propose to revoke‖, can fall within that category so as to enable it to appeal. If it does not have the right to participate in the hearing of such a proposal, nor appeal a decision which might be made then by the Commissioner not to revoke, it cannot possibly be said to have the right to appeal the preliminary refusal by the Commissioner to in fact make such proposal.

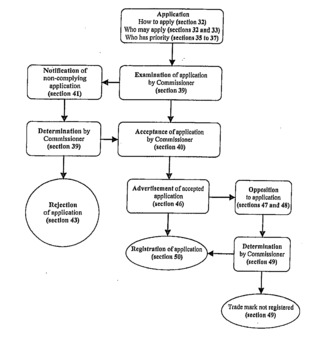

[57] The diagrammatic process set out in Part 3 of the Act does not provide any

support for the appellant’s contentions.

[58] My conclusion therefore is, that the Step 1 decision not to propose to revoke acceptance of another’s application was not a decision that entitled Muir Electrical to appeal under s 170.

[59] Although not necessary to dispose of the appeal, because counsel argued the point I will briefly give my views on whether it was open to the Commissioner to conclude no ―error or omission‖ had arisen, so as to provide s 42 jurisdiction.

[60] There must be examination by the Commissioner of an application and he being satisfied that it complies with the requirements of the Act, before it can be accepted (s 39). The fulfilment of this duty before advertising arises is not a

―preliminary hearing‖.11 There has to be a measured initial conclusion or

determination that the application complies with the requirements of the Act. Applications for word marks, based upon honest and concurrent use of identical or similar marks, or other special circumstances, may provide difficulties where supported by statutory declarations, yet others contend that such use does or did not arise. It is an exception to the prohibition of the identical or similar mark. Here the Commissioner accepted the application after receiving the declarations/claims/submissions of the Good Guys Group, in circumstances where it had claims by Muir Electrical that this should not occur because of facts that existed.

The Commissioner, having accepted the application, could not revoke unless he/she was satisfied that this acceptance occurred because of error or omission.

[61] Muir Electrical says the decision to accept and not to (propose to) revoke was wrong on the merits. A recent decision relating to s 42(1)(a) is Re Apples 4 Apples,12 a decision of IPONZ. The IPONZ proposed to revoke acceptance of the trade mark pursuant to s 42(1)(a), on the basis that there had been an ―error‖ in acceptance because the Acceptance Officer was not in possession of all of the facts. Reference was made to the Australian case of Re STM Inc where the Hearing Officer (on behalf of the Registrar) stated that:13

The examiner made the decision to accept the applications without all of the material facts in front of him — in very much the same way that an examiner might have missed a dictionary definition: Shop-Vac Corp’s Application (1990) 19 IPR 65. Whether, as the applicant has suggested, the examiner made a conscious decision not to look for some of the relevant facts is irrelevant for the purposes of my decision here. A decision to accept an application in the absence of this relevant information is a mistake.

Thus I would add a qualifier to the remarks of the Deputy Registrar in the Smooth and Silky case, to the effect that where an acceptance occurs, absent the basic principles of research and examination such that proper examination has not occurred and the necessary information upon which judgement might be exercised is not before a delegate, an error or omission (or both) has occurred.

[62] The IPONZ said in Apples that a full reference search was not conducted, due to the examiner not being aware of the common use of the term in the building industry. The applicant was notified of that view, and requested a hearing. At the hearing, the applicant did not dispute reliance on Re STM Inc, however emphasised the distinction between mistake or ignorance as to objective facts (an error) and different interpretations of those facts (not an error). The applicant relied upon the

Australian decision Enviroderm Australia Pty Ltd (Freshly Pure),14 where the

Hearing Officer said that:

A point of view, which may be changed or challenged upon further information or argument, is not fact and should not be treated as such. However, that there can exist different judgements relying upon different points of view, but nevertheless originating from the same set of facts, does

12 Re Apples 4 Applies IPONZ T24/2008, 18 August 2008.

13 Re STM Inc (2004) 63 IPR 249 at [21] – [22].

14 Envrioderm Australia Pty Ltd [2002] ATMO 38 (IP Australia Hearings Office).

not necessarily show either judgment to be in error, or that one should be displaced by the other.

[63] The Hearing Officer in Apples noted other relevant decisions, including

Re Remington Products Inc cited above.15

[64] On the facts in Apples, the Hearing Officer concluded that the proposal to revoke acceptance appeared to be ―more the result of a difference of opinion as to the registrability of the applicant’s mark rather than the result of any error or omission of the examiners who accepted the application‖. In any event, there was no evidence of the various errors or omissions said to have occurred; simply an assertion of those errors in the notice of the proposal to revoke acceptance. Accordingly, the Hearing Officer was not satisfied that the application was accepted due to error or omission, and concluded that the Commissioner’s discretion to revoke should not be exercised.

[65] Counsel for Muir Electrical submitted that, here, there were material facts not

before the examiner, so that mistake or ignorance of the facts constituted ―error‖ or

―omission‖. In this case it is far from certain that any facts, or (disputed) allegations of fact, were actually missing. The submissions on behalf of the Good Guys Group assert that the alleged facts were drawn to the attention of IPONZ, before a final decision on acceptance was made. On 6 July 2010 IPONZ advised the Good Guys Group that it proposed to accept the application subject to the specification amendment. On 27 July 2010 Buddle Findlay on behalf of Muir Electrical, requested that the proposal for acceptance be withdrawn providing reasons, factual allegations and submissions as to why that should occur. On 3 August 2010 solicitors for the Good Guys Group responded. On 17 August 2010 IPONZ confirmed to the Good Guys Group that having assessed all information supplied if the applicant agreed to amend the specification the application would be in order for acceptance. It is difficult to see how, if that accurately represents the process, there was ignorance of fact.

[66] Nevertheless, assuming that there was a mistake or ignorance of fact, these must be mistake or ignorance of a necessary objective fact. The important passage in Re STM:16

where an acceptance occurs, absent the basic principles of research and examination such that proper examination has not occurred and the necessary information upon which judgement might be exercised is not before a delegate, an error or omission (or both) has occurred.

[67] This highlights that it is not any mistake or ignorance of fact that qualifies as

an ―error or omission‖, but rather:

![]() the mistake or ignorance of fact must negate basic

principles of research

the mistake or ignorance of fact must negate basic

principles of research

and examination;

![]() such that a proper examination has not occurred and

the necessary

such that a proper examination has not occurred and

the necessary

information is not before the examiner.

[68] Acceptance was revoked in that case because the examiner should have searched for potentially conflicting trade marks which contained, or consisted of, the words ―steam fresh‖. The Hearing Officer said that:

I do not think that examiner’s position (whatever its justification) in not searching for the words ―steam fresh‖ as a trade mark is open to argument – the acceptances are quite plainly mistaken as to the facts on which they were based – these being incomplete as to the facts that should have been before the examiner.

The examiner made the decision to accept the applications without all of the material facts in front of him – in very much the same way that an examiner might have missed a dictionary definition: Shop-Vac Corp’s Application ...

[69] But that was not the case here. Muir Electrical identified or alleged conflicting facts, as the basis for alleged ―error or omission‖. Where the facts alleged are denied it cannot be said that there is a complete absence of them – that requires later determination. In the exercise of this initial duty, in the context of this Act, it is not an error for the examiner to decline, at the preliminary stage, to look behind the applicant’s statutory declaration. He may do so, but does not have to. There may be many situations, such as where he accepts there were known instances

of confusion, that do not lead to his ―satisfaction‖ that error or omission exists. Simply because the appellant may point to potential instances of confusion, or areas of contested claims, does not mean that an examiner erred or omitted by not considering that aspect. Muir Electrical may eventually be right but the time for resolving the conflict is at an inter-parties’ objection hearing.

[70] The examiner had an evidential basis upon which to accept the application and there was no failure of basic principles of research and examination. Parliament did not intend that the acceptance process be inter-parties, which is the role of opposition proceedings. It could not have been intended that the existence of conflicting facts, negates the acceptance process. Where ―facts‖ are disputed at the acceptance – or request to revoke – stage, and the Commissioner is not ―satisfied‖ in terms of s 42(a) that he/she accepted the application because of error or omission, the statutory scheme does not enable the third party, to require the pre-registration hearing (which requires a ―proposal‖ to revoke) process to occur.

[71] Finally, and in any event, the contested facts were all raised by Buddle Findlay in its letter of 27 July 2010 to the Commissioner. The letter sent on behalf of the Commissioner on 17 August 2010 records that ―the Office has carefully considered the concerns raised by Buddle Findlay‖ in its letter and that:

Having assessed all of the information supplied to the Office, we maintain the position that if the applicant agrees to amend the specification the application would be in order for acceptance under section 26(b).

[72] That amendment was agreed by the Good Guys Group and acceptance occurred on 27 August 2010. Accordingly, the acceptance could not have been made in ignorance of the claimed facts.

Conclusion

[73] For the foregoing reasons I am satisfied that the appeal of Muir Electrical must fail. The proper process is for it to participate as an objector – in which it is already involved – so that informed decisions can be made after full inter-party participation in a dispute process, the outcome of which may, itself be the subject of appeal under s 170 on the part of either Muir Electrical (if its opposition fails) or the

Good Guys Group (if its application for registration fails). To circumvent this process by this appeal is not within the scheme and procedures envisaged by the Act and Regulations.

[74] The appeal is dismissed.

[75] The Good Guys Group are entitled to costs which are fixed on a Category 2B

basis. I certify for second counsel. If the Commissioner seeks an order for costs, counsel may submit memoranda.

J W Gendall J

Solicitors:

Buddle Findlay, Auckland for Appellant

(Counsel acting: A H Brown QC, Auckland)

James & Wells, Solicitors, Auckland for Respondent

Crown Law Office, Wellington for Commissioner

NZLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.nzlii.org/nz/cases/NZHC/2011/277.html