|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

High Court of New Zealand Decisions |

Last Updated: 20 July 2011

IN THE HIGH COURT OF NEW ZEALAND AUCKLAND REGISTRY

CIV-2008-404-3581

BETWEEN THE BABY HAMMOCK CO LIMITED Plaintiff

AND AJ PARK LAW Defendant

Hearing: 7-11, 14-18, 21-25 February and 23 & 25 March 2011

Counsel: CR Pidgeon QC and RS Pidgeon for Plaintiff

B Brown QC, DH McLellan and MD Atkinson for Defendant

Judgment: 13 July 2011 at 4:00 PM

JUDGMENT OF RODNEY HANSEN J

This judgment was delivered by me on 13 July 2011 at 4.00 p.m., pursuant to Rule 11.5 of the High Court Rules.

Registrar/Deputy Registrar

Date: ...............................

Solicitors: Regent Law, P O Box 204, Whangarei 0140 for Plaintiff (Mr L MacBrayne) Jones Fee, P O Box 1801, Shortland Street, Auckland 1140 for Defendant (Ms P Fee)

THE BABY HAMMOCK CO LIMITED V AJ PARK LAW HC AK CIV-2008-404-3581 13 July 2011

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction [1]

Negligence

First contact [4] Meeting of 20 August 2004 [7] Meeting of 27 October 2004 [13] The C-shaped (Bennetts) stand [16] The flexible spreader bar [31] Mr Gilmore’s emails [41] Conclusion [48]

Causation [52]

Failure to obtain working capital [54] Loss of business opportunities [62] Other causation issues [73] Conclusion on causation [77]

Breach of fiduciary duty

Introduction [78] The relevant duties [84] The scope of the retainer [96]

A duty to disclose? [101] Discussion [105] Causation [110]

Damages

Compensatory damages [113]

Exemplary damages [129]

Result [130]

Introduction

[1] The plaintiff (BHC) developed and marketed a baby hammock which could be suspended from a ceiling or doorway or from a stand that was sold separately. In the early stages of the hammock’s development BHC’s directors, Gregory and Sarah Hannah, sought advice on intellectual property issues from the defendant (AJ Park), a firm of patent attorneys with offices in Auckland and Wellington. The Hannahs and BHC say that AJ Park was negligent in advising them that two components they had developed for use with the baby hammock – a stand and a flexible spreader bar – could not be protected by patent, registered design or otherwise.

[2] Several years later, after BHC had begun marketing the hammock in New Zealand and overseas, AJ Park agreed to act for another New Zealand manufacturer of baby hammocks, Hushamok Limited (Hushamok). On Hushamok’s instructions, AJ Park registered designs of a baby hammock and stand. BHC says that its interests and Hushamok’s interests conflicted and, in acting for Hushamok, AJ Park breached fiduciary duties owed to BHC.

[3] BHC says that as a result of AJ Park’s negligence it was unable to raise finance to fund its operations and to exploit opportunities to expand its business. Damages for loss of profits resulted. It seeks compensatory damages and, for the breach of fiduciary duty, exemplary damages.

Negligence

First contact

[4] Sarah Hannah developed the BHC baby hammock from a hammock sold under the trade name Babeeze which she bought in 1998 and used for her babies. The Babeeze hammock was made of fabric. It was suspended from the ceiling by a hook. Part of the suspension mechanism was a coiled spring which enabled the hammock to move up and down as well as swing from side to side.

[5] Mrs Hannah began working on her own design in 2003. By late 2004 she had had a prototype manufactured by a company called Tritech. The hammock was made of cotton and was closely modelled on the Babeeze hammock.

[6] On 12 August 2004 Mrs Hannah fortuitously sat next to an employee of AJ Park, Jonathan Aumonier-Ward, on a flight from Wellington to Auckland. She told him about her new business and her interest in retaining the services of a patent attorney. Mr Aumonier-Ward reported to colleagues at AJ Park that Mrs Hannah had a trademark she wanted to protect and that she also wanted to enquire about patent protection. He asked Damon Butler, a patent attorney then employed by AJ Park, to telephone Mrs Hannah to discuss the trademark issue and to arrange for someone else to talk to her about “patent/design/copyright for the hammock”.

Meeting of 20 August 2004

[7] A meeting was arranged for 20 August 2004 at AJ Park’s Auckland office. Mrs Hannah attended on her own. Mr Butler was present. He was in AJ Park’s trademark team. He was then a senior associate in the firm, becoming a partner in

2006. Also in attendance was Duncan Schaut. He was then a patent executive employed by AJ Park. At the time he had an engineering degree but had not completed a law degree. Mrs Hannah thought another AJ Park patent attorney, Anton Blijlevens, was also present. I am satisfied she is mistaken in this. She and Mr Blijlevens did not meet until the following year.

[8] The meeting was of an introductory nature. I think Mr Butler accurately described it as “basically just a meet and greet to find out more about the client’s business and to give them some general advice about IP rights”. It gave Mrs Hannah an opportunity to meet AJ Park staff. She confirmed that she did not decide to retain their services until then.

[9] It appears that, for the most part, the discussion was very general. Among other things, Mrs Hannah explained how the idea originated. Mr Schaut made notes which included references to the Babeeze hammock and another baby hammock

manufacturer, Nature’s Sway. He made a rough sketch of the hammock depicting

the way in which it was suspended.

[10] Mrs Hannah was insistent that she took a prototype of her hammock to the meeting but I do not think this is correct. I prefer the recollection of the AJ Park witnesses on this issue. I think it likely that the sketch was drawn in order to record Mrs Hannah’s oral description. The presence of a prototype at the meeting is also inconsistent with an email Mrs Hannah sent before the next meeting with AJ Park which concluded with the question, “And do you want to see the original hammock that we copied and the new ones?”

[11] At the first meeting Mr Butler gave specific advice regarding the registration of the Baby Hammock name and logo which he confirmed in a letter the following Monday, 23 August. On the same day, Mr Schaut sent particulars of companies registered using the name “Naturesway” (sic). No other steps were taken by AJ Park. No advice was recorded. There was no charge for the meeting. All of the indications are that it was precursory in nature very much as Mr Butler described it.

[12] Mr Butler took no steps to register the trademark pending advice that Mrs Hannah wanted him to proceed. On 18 October she advised him that the Baby Hammock sample range was “pretty much complete” and that she expected it to be ready to sell to shops the following week. She asked whether trademarking should be done before this process began. She was advised that that would be advisable. A meeting was then arranged for 27 October.

Meeting of 27 October 2004

[13] This meeting is of pivotal importance to BHC’s negligence claim. BHC’s case is that at the meeting Mr and Mrs Hannah specifically sought advice in relation to a stand and a flexible spreader bar and were told that the prototypes and designs shown by them were not able to be protected by patent or registered design. It is further claimed that AJ Park failed to advise BHC of steps that could be taken to protect the products, whether by patent, registered design or otherwise.

[14] Both Greg and Sarah Hannah attended the meeting. Mr Butler and Mr Schaut were again present representing AJ Park. There are important differences between the Hannahs, on the one hand, and AJ Park’s personnel, on the other, as to what took place at the meeting. These differences include the key issue of whether the hammock stand and the flexible spreader bar were even discussed at the meeting.

[15] The first significant point of difference concerns what the Hannahs took to the meeting. In particular, there is a conflict as to whether the Hannahs brought with them the prototype of a stand – known as the C-shaped stand or the Bennetts stand – from which the hammock could be suspended. The Hannahs say they brought the stand to the meeting. Messrs Butler and Schaut are adamant they did not.

The C-shaped (Bennetts) stand

[16] The stand was acquired from Mr Michael Bennetts who has a business selling hammocks. Mrs Hannah visited his shop one day to enquire whether he was interested in stocking baby hammocks. He showed her the prototype of a stand, shaped like the letter “C”, which he had designed in 2002 when he began selling Nature’s Sway baby hammocks as part of his range. At that time he suggested to the proprietor of the business, Kate Hornblow (then Kate Sumich), that she consider introducing a stand from which to suspend her hammocks. She was sufficiently interested to encourage him to come up with a design and to have two prototypes fabricated. She exhibited one of the prototypes at a trade show in 2002 but eventually decided against introducing the stand because of safety concerns.

[17] Mrs Hannah was, however, greatly attracted to Mr Bennetts’ concept. She agreed to acquire copyright in the design and to purchase the prototypes. A critical issue is when she met with him and acquired the stand. Mrs Hannah could not be precise but was emphatic that she had received the prototypes by the time of the October meeting with AJ Park. Mr Bennetts confirmed this. He recalled that at the time of the meeting he was preparing to exhibit at a major event which could only have been the Home Show or the Ellerslie Flower Show. At the time they were held, respectively, in September and November of each year. Mr Bennetts said Mrs Hannah took the prototypes after the meeting, saying she would be taking them

to her attorneys to review. He said that some months later she contacted him and asked him if he would also be prepared to transfer ownership of the design to her. After reflecting on it, he agreed to transfer the copyright at no cost.

[18] I am satisfied that both Mrs Hannah and Mr Bennetts are wrong about the timing of the meeting. I do not believe that Mrs Hannah took possession of the stand until after the October meeting at AJ Park, probably not until April 2005. I thought Mr Bennetts was an honest witness but I am sure he was mistaken about the timing of this meeting with Mrs Hannah and that his evidence owed much to suggestions about the course of events made to him after he was approached to give evidence. In successive versions of his brief of evidence, further detail was added. He explained that “in the process of questioning and focusing on what has happened in the past, from way, way back there are events that come to mind”. In my view, some of the events that came to mind of which he speaks were not the product of his unaided recollection. They were a response to the way in which long forgotten events were recalled to him in conversation with Mrs Hannah.

[19] I do not believe the stand was taken to the meeting in October. I was impressed by the evidence of Mr Butler and Mr Schaut on this issue. The stand is a substantial object, some two metres high. Both witnesses explained that to bring it in and set it up in the meeting room would have involved a manoeuvre that would have left an impression on their mind. I am sure that, if the stand had been brought into the room, they would have remembered.

[20] There is no reference to the stand in the notes Mr Schaut made of the meeting, although they are brief and I do not attach great significance to the omission. Of much greater significance is the absence of any reference to the stand in a three-page letter written on 25 November 2004 which purports to summarise what took place at the meeting. It summarises the way in which the hammock was developed and sets out detailed advice on copyright issues. It concludes by referring to a new product tentatively termed “Mark II”, an issue to which I will return. There is nothing to suggest that the stand was discussed.

[21] It is also significant that the stand does not feature in a series of photographs taken not long before the meeting. The photographs were taken after Mrs Hannah received the prototype of the hammock from the chosen manufacturer, Tritech. They were printed on 14 October 2004. I agree with Mr McLellan that if Mrs Hannah had been in possession of the stand at this time, it would have appeared in the photographs. Mrs Hannah said that she was excited about the stand. It was a “light bulb moment” when she saw it. She immediately appreciated its potential.

[22] The fact that the stand does not appear in the photographs is not conclusive because it could conceivably have been acquired between the time of the photographs and the date of the meeting. But it is yet another circumstance which indicates that the stand did not come on the scene until some months later.

[23] The first reference in AJ Park’s records to the Bennetts stand is in a diary note by Mr Blijlevens of a meeting he had with Mrs Hannah on 15 April 2005. In it Mr Blijlevens records advice from Mrs Hannah regarding the acquisition of the stand and an instruction from her to arrange the transfer of the copyright. There is much that is factually incorrect in the file note but there is no doubting its authenticity and, although Mrs Hannah initially denied that a meeting had occurred on 15 April, she conceded that it “may have” occurred.

[24] I find it highly unlikely that Mrs Hannah would have waited six months after acquiring the stand to take steps to effect the transfer of copyright. If she had in fact acquired the stand in 2004 and taken it to the October meeting, I consider she would have taken steps then and there to acquire copyright.

[25] I am satisfied that Mrs Hannah saw Mr Bennetts for the first time during the week ending 15 April. She had just come back from China bringing with her samples of the hammock manufactured in China. At the end of 2004 or early in

2005, she had abandoned plans to have the hammock manufactured by Tritech and early in 2005 began researching prospective manufacturers in China. She and her husband visited China between 4 and 11 April 2005. Mr Bennetts said that when Mrs Hannah first came to his shop she told him she would be having the hammock made in China, and he presumed the prototype had been made there. That is

consistent with the visit taking place after Mrs Hannah returned from China. On the other hand, it is totally inconsistent with a visit before the October meeting; at that time there had been no thought of the hammock being manufactured in China.

[26] Mr Hannah says they took the Bennetts stand with them on the first trip to China. Mrs Hannah recalls she took it when she went by herself between 29 June and 13 July 2005. They agreed, however, that the Bennetts stand was used as the model for a tubular steel stand shaped like a “G” (the G-shaped stand) which the chosen manufacturer in China (Danlong) agreed to produce.

[27] Mr Hannah’s recollection of when the Bennetts stand was taken to China must be wrong. On this matter, Mrs Hannah is right. She could not have taken the Bennetts stand until she went on the second trip at the end of June. On my view of the evidence, when Mrs Hannah first visited Mr Bennetts’ showroom, she recognised the potential of his prototype stand and hurriedly sought to acquire rights to it before returning to China.

[28] In my view, the use of a stand with the baby hammock did not loom large in the Hannahs’ thinking until they went to China. It is true that email correspondence in the second half of 2004 from a prospective investor, Shaun Gilmore (whose evidence I will discuss in more detail later), refers to the use of stands, but there is nothing else to indicate that the Hannahs were actively seeking to develop a design for a stand until they went to China.

[29] Although they differed on timing, both Mr and Mrs Hannah insisted that the G-shaped stand made for them by Danlong, the Chinese manufacturer, evolved from the Bennetts stand. I do not accept that. The G-shaped stand closely resembles a stand depicted in a 2004 brochure produced by Danlong for use with a hammock chair. I believe that stand, not the Bennetts stand, was used as the basis for developing the G-shaped stand. Plainly, it was much cheaper and more efficient to use or adapt a stock item than to set up and manufacture a stand from scratch. It enabled Mrs Hannah to approve the design of the stand on the day she arrived in China on the second trip. The manufacturing agreement records this. While Mrs Hannah resisted the suggestion that, on arrival in China, she immediately abandoned

plans to manufacture the Bennetts stand and opted for a stock item, I find the contemporary documents dictate a different view. They record that on 1 July (two days after arriving in China) she placed an order for 810 hammocks and 120 stands. The order confirmation states that the hammocks would be finished by 7 July but the stands would not be ready until 11 July because of the time taken to buy steel tubes.

[30] I have digressed to give this account of the way in which the Hannahs developed the BHC stand in order to put the acquisition of the Bennetts stand in context. My finding that the Bennetts stand was acquired well after the October

2004 meeting confirms as implausible BHC’s claim that AJ Park was asked at that time to advise in relation to a stand. BHC did not have a stand to take to the meeting. There was no reason to even raise the issue with AJ Park at that time.

The flexible spreader bar

[31] The second important point of difference between the Hannahs and the AJ Park personnel attending the meeting on 27 October concerns the flexible spreader bar. This is a modified suspension system for the hammock which BHC says Mr Hannah had been working on for several months before the meeting.

[32] The Babeeze hammock and the prototype developed by Mrs Hannah incorporated a rigid wooden spreader bar. As its name implies, its function was to keep the sides of the hammock apart. As the sides of the hammock extended and converged to the point from which it was suspended, without the spreader bar the hammock would be enclosed like a bag. The spreader bar ensured that the hammock was open, fully ventilated and easily accessed.

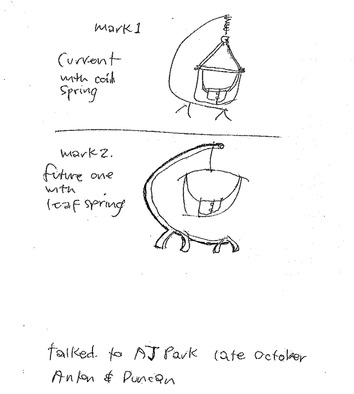

[33] Mr Hannah said he came up with the idea of using a flexible spreader bar, not dissimilar to the leaf spring used for suspension in motor vehicles. It would have the dual function of separating the sides of the hammock while providing the vertical movement provided in the prototype by a coil spring. Mr Hannah said that at the meeting of 27 October he made a sketch of the prototype, incorporating the coil spring and rigid spreader bar and, separately, of a modified design incorporating a flexible spreader bar. The sketch, which is annexed to the plaintiff ’s statement of claim, appears below. The words “talked to AJ Park late October Anton & Duncan” were added later.

[34] Mr Hannah said that during the months preceding the meeting, he had made drawings of the flexible spreader bar and stand. Some had apparently been sent to Mr Gilmore. None of these have survived. Mr Hannah said that when he went to the meeting, he was “keen to carry on with the flexible spreader bar ...”. He said his wife was “not so keen” so he “pulled [Duncan Schaut] aside at first to avoid some

trouble or a stern look ...”. Mr Hannah said the sketch was photocopied by someone

at AJ Park who retained the original.

[35] Mr Hannah said when he filed his copy of the sketch several months later, he noted the names of the AJ Park personnel who attended the meeting. He acknowledged that he wrongly identified Anton Blijlevens as being present instead of Damon Butler.

[36] Mrs Hannah confirmed that her husband made the sketch at the October meeting. She was unable to recall whether he had done any drawings of the flexible spreader bar before then. There was nothing in her evidence to indicate disapproval of the development or any other reason why Mr Hannah should have chosen to take Mr Schaut aside when he made the sketch. On the basis of the correspondence with Mr Gilmore, Mrs Hannah was promoting the idea.

[37] BHC found further support for its contention that the flexible spreader bar was discussed at the October meeting in a rough sketch drawn by Mr Schaut at the meeting which appears to have some of the features of a flexible spreader bar. However, he explained his sketch to my satisfaction as a depiction of the suspension system incorporating a rigid spreader bar. He said it was not intended to be an accurate pictorial representation. He said some details were removed for clarity so he could understand the product.

[38] I accept Mr Schaut’s evidence that at the two meetings there was no discussion of the hammock as a stand-alone unit suspended from a stand. The means of suspension discussed were door clamps or a hook attached to a doorway or ceiling. I also accept that there was no specific discussion of the introduction of a flexible spreader bar although, as I will later mention, there was some general reference to improvements to the product that Mr Hannah was working on.

[39] The actions of AJ Park after the October meeting are consistent with Mr Schaut’s evidence. AJ Park applied for registration of the trademark. Mr Schaut co-authored a letter with Mr Blijlevens, as the senior associate to whom he reported. It summarised AJ Park’s understanding of the background. There is reference only

to the hammock. There is no mention of a stand. There is advice in relation to concerns that the hammock may infringe the intellectual property of other manufacturers, particularly Babeeze, whose hammock formed the basis of the BHC design. The letter concluded:

You have mentioned to us the designing of a new “baby hammock” product which we have tentatively termed “Mark II”. We suggest that as part of the designing of this Mark II product that you engage the services of an independent designer so that you have and can show a clear break in any alleged chain of copying, between the Mark II product and any earlier product that may be alleged originated from Christchurch.

[40] BHC claims the “Mark II” product is a direct reference to the sketch made by Mr Hannah and confirms that the flexible spreader bar was discussed at the meeting. That would be the obvious inference if the sketch had been made or presented at the meeting. But I believe it came into existence after the meeting using the terminology for a new product which had been discussed in a general way at the meeting.

Mr Gilmore’s emails

[41] I mentioned earlier that I would give separate consideration to the evidence of Shaun Gilmore and the exchange of emails between him and Mrs Hannah during the last half of 2004. The emails support BHC’s position that a stand and flexible spreader bar were in contemplation and development before the October meeting. I need to explain why I place no weight on this evidence.

[42] Mr Gilmore is the managing director of a Christchurch firm, the Poppet Company, trading as Pamco Nursery Furniture (Pamco) which manufactures and sells children’s furniture. Mr Gilmore said he met Mrs Hannah at a Farmers store in Auckland in July 2004. Mrs Hannah overheard a conversation he was having with a buyer and approached him to ask his advice on the new product she was planning to market. Mr Gilmore said Pamco was looking at new products and new markets at the time. It had money available for investment. He thought BHC’s baby hammock had good prospects. After further investigations and discussions, Mr Gilmore advised the Hannahs that Pamco would be prepared to acquire a 40 per cent stake in BHC for $300,000 provided that the baby hammock and stand could be protected by

patents or registered designs. When BHC was unable to obtain protection, Pamco did not proceed with the proposal.

[43] A series of emails were produced which plotted the course of negotiations. They refer to designs being developed by Mr Hannah and were relied on to corroborate the evidence of Mr and Mrs Hannah in relation to the acquisition of the Bennetts stand and the development of the flexible spreader bar. The defence did not accept the authenticity of the emails passing between Mr Gilmore and Mrs Hannah; this was an express exception to the agreed terms on which the bundle of documents was admitted.

[44] The emails were hard copies which Mr Gilmore said had survived a company liquidation. The computer on which electronic copies would have been stored was lost. The Hannahs’ record of the emails had also been destroyed as a result of computer malfunction. There are curious features of the hard copies produced which were not satisfactorily explained. Some of the emails from Pamco to Mr and Mrs Hannah are duplicated but show different email addresses. One of the addresses has never been used by the Hannahs. None of them disclose who had printed the emails. Mr Gilmore explained that this had come about because he used a process of cutting and pasting. Without expert evidence, I could make no finding on the implications of these apparent oddities. However, they add to the disquiet I harbour for other reasons.

[45] The emails allegedly authored by Mr Gilmore contain idiosyncratic spelling which was not replicated when he was asked to handwrite a sentence containing the words in question. Whenever the word “cannot” was used, it was spelt as two words, “can not”. “Mummy” was spelt “Mommy”. There was a reference in one of the emails to “utility patents” which is a term of art apparently used in America and was clearly a term with which Mr Gilmore was unfamiliar. These features cause me to doubt whether Mr Gilmore was in fact the author of the emails.

[46] I am also disquieted by Mrs Hannah’s statement in an email to Mr Gilmore dated 10 August 2004 that “We are going to be working with AJ Park ...”. As Mrs Hannah did not meet Mr Aumonier-Ward on the flight from Wellington to

Auckland until the evening of 12 August and said in evidence that she did not decide to retain AJ Park until she met with them on 20 August, the statement she makes in the email is either incongruous or clairvoyant. In cross-examination she maintained that when the email was written she had already made enquiries and, as AJ Park had been among the firms recommended, she knew she was going to meet with them. I find this an implausible explanation. What Mrs Hannah said in the email and Mr Gilmore’s reply - “Let us know as soon as you can what AJ Park says. That will be critical to our going forward.” - confirm my view that the emails are not authentic.

[47] While I do not doubt that Mr Gilmore had dealings with Mrs Hannah over the period in question, I do not believe the emails from Mr Gilmore to the Hannahs were generated at the time. I can only speculate on the circumstances in which they came into existence. It is sufficient to record that the author is likely to be American (suggested by the reference to “Mommy”) with some knowledge of patent law who characteristically separates out the “can” and the “not” when spelling “cannot”.

Conclusion

[48] I am satisfied that neither the stand nor the flexible spreader bar were discussed at the October meeting. I believe Mr Hannah’s sketch and the emails passing between Mr Gilmore and the Hannahs, which would have supported a contrary view, came into existence after the meeting and were not created for the purpose for which they were put forward.

[49] The pleadings claim that AJ Park gave negligent advice on multiple occasions, including at the August and October meetings, that BHC’s rights to the stand and the flexible spreader bar could not be protected by patent or registered design. In closing, Mr Pidgeon accepted that, if the spreader bar was not mentioned at the October meeting, there was no subsequent opportunity for AJ Park to advise in relation to it. He argued, however, that if the stand was not mentioned at the October meeting, there were subsequent opportunities for AJ Park to offer advice.

[50] The only other occasion on which the C-shaped stand was discussed was on

15 April 2005 when Mr Blijlevens was instructed to arrange the assignment of copyright. However, it is not suggested that he was shown the stand at the time. He was not even provided with a photograph until he later prepared the documentation. I accept his evidence, confirmed by the note he made of the meeting, that his instructions were solely to obtain an assignment of copyright. I am satisfied his advice was never sought on patent or design registration.

[51] It follows that BHC’s claim that AJ Park was negligent in the advice they gave fails on the facts. AJ Park was never in a position at the relevant time to give advice in relation to either the stand or the flexible spreader bar. BHC sought advice only in relation to the hammock.

Causation

[52] My finding that AJ Park was not negligent makes it strictly unnecessary for me to consider consequential matters, the issue of causation among them. I will shortly state my views on these issues nonetheless so that the parties will have a full appreciation of the strengths and weaknesses of their respective cases.

[53] BHC claims that because its intellectual property rights were not protected

(due to AJ Park’s negligent advice), it lost profits in two ways:

(a) Through its consequential inability to obtain working capital to fund expansion; and

(b) Because distributors and retailers were unprepared or reluctant to stock a product which did not have patent protection and/or which exposed them to legal action by rival firms with patent protection.

For the reasons which I will briefly outline, I am satisfied that, even if AJ Park had been negligent as pleaded, the claimed losses would not have followed.

[54] BHC claimed it had two opportunities to obtain working capital which were stymied by the lack of intellectual property protection. The first was the $300,000 which Mr Gilmore said he ultimately declined to invest on behalf of his company, Pamco, because the BHC products did not have patent protection. I have already expressed my misgivings about the evidence of the dealings between BHC and Mr Gilmore. The way in which the funding proposal is developed in the emails serves only to confirm my reservations.

[55] The first email in the sequence is from Mrs Hannah, dated 30 July 2004, which refers to “our stand/hammock”. As I have already said, I am satisfied that BHC did not have a stand at that stage. By 11 August Mr Gilmore was writing about an investment of $300,000 for an equity holding of “about 50%”. In the email he says he will send an investment proposal in writing later that week. There is no indication that an investment proposal was ever sent.

[56] I agree with Mr McLellan’s submission that it is implausible that Mr Gilmore would have contemplated investing $300,000 at such an early stage of his dealings with Mr and Mrs Hannah. The air of unreality is heightened by the concluding paragraph of his 11 August email1 which appears further contrived to support BHC’s case:

Let us know as soon as you can what AJ Park says. That will be critical to our going forward.

[57] After two further emails referring to a stand and “leaf spring” (neither of

which existed at the time, in my view) Mr Gilmore advised in an email dated

15 November that Pamco would not invest in something that “can not (sic) be protected”. Again, I agree with Mr McLellan that, as this advice predated AJ Park’s reporting letter of 25 November, the obvious response on receipt of the email, given the stated importance of the funding to BHC, would have been to press AJ Park to review its advice and specifically address the patentability of the stand and flexible

spreader bar. The failure to do so after receipt of the letter of advice confirms my

1 This has already been referred to – see [46] above.

doubts about the authenticity of the emails and the plaintiff’s account of events at

this time.

[58] In my opinion, there was never a serious funding proposal from Mr Gilmore. AJ Park’s advice on intellectual property issues could not have had any effect on BHC’s efforts to raise capital in late 2004.

[59] Four years later, BHC retained the services of Mr David Rouse, a management consultant with Nemo & Associates, to obtain funding of $500,000. Mr Rouse’s firm conducted an extensive analysis of the accounts and business plan of BHC, relying mainly on information provided by Mrs Hannah. He made presentations to a number of potential investors, ending up with five who were interested. However, by the end of the process, Mr Rouse said there was only one “really serious” potential investor.

[60] It emerged in cross-examination that much of the information provided to Mr Rouse to assist in his search for an investor was incorrect. The accounts he relied on were inaccurate. The turnover figures for the previous financial year were overstated. He was not told of a cancelled order from BHC’s American distributor which materially affected the results. Mr Rouse was given to understand that BHC expected to obtain patent protection for its hammock and stand. It was not until he neared the end of the process in mid-2009 that he was told that proceedings had been brought against AJ Park.

[61] Mr Rouse frankly acknowledged that if he had been fully informed at the outset, he probably would not have taken the matter any further. That was realistic. In my view, an arm’s length investor with knowledge of BHC’s true financial position would not have put any significant sum into the company. The absence of intellectual property protection had no bearing on this outcome.

[62] BHC claimed that, because it did not have registered intellectual property rights for its product, it lost the business of an American distributor who could have generated massive sales in the United States.

[63] Sycamore Kids Inc (Sycamore) was founded in 2001. It traded in children’s goods, including a highly successful line of mountain buggy strollers imported from New Zealand. The founder and president of Sycamore, Mr Alan Jurysta, was introduced to Mr and Mrs Hannah by the manufacturer of the mountain buggy strollers.

[64] Upon receiving samples of the BHC hammock and stand in 2006, Mr Jurysta sought the advice of a United States consultant on intellectual property, John Zambrzycki. He advised Mr Jurysta against importing the BHC product because it may infringe the patent of a baby hammock marketed by an Australian company, Amby Baby Hammock Pty Ltd. Mr Zambrzycki obtained Mr Jurysta’s consent to contact BHC and ended up advising them in relation to patent issues. Some time later he applied for United States patents on BHC’s behalf.

[65] In April 2007, Mr Zambrzycki attended a trade show in Florida. Hushamok Limited – the New Zealand baby hammock manufacturer also advised by AJ Park – had a stand at the show. Mr Zambrzycki visited the stand and was told by the proprietors, Mark and Julie Soboil, that AJ Park advised them and had applied for patent protection on their behalf. Mr Zambrzycki passed this information onto Mr and Mrs Hannah, which led in time to the claim for breach of fiduciary duty.

[66] Notwithstanding his initial concerns, Mr Jurysta said he agreed to carry the BHC product in the United States based on assurances that BHC would work with Mr Zambrzycki to design a new stand that could obtain patent protection in the United States. Initial responses were encouraging and at a trade show in September

2007 the product received “enormous positive feedback”. However, as a result of contact with Hushamok’s principals during that show, in which Mr Jurysta was told that Hushamok had filed for patents worldwide and of warnings given by Hushamok

to potential customers of Sycamore, Mr Jurysta said he was hesitant to continue the relationship with BHC and thereafter did not aggressively market or advertise the product. He said that, based on Hushamok’s threats and potential threats of a patent infringement suit against Sycamore and its customers, and having regard also to uncertainties about BHC’s ability to gain patent protection, Sycamore brought its relationship with BHC to an end.

[67] In the course of cross-examination, however, a somewhat different picture emerged. The business relationship between BHC and Sycamore continued until mid-2009 but I consider that the reasons why it did not flourish and eventually came to an end were largely unrelated to intellectual property issues.

[68] Immediately after the trade show in September 2007, Mr Jurysta set about enthusiastically promoting the product. He spent between $US30,000 and

$US60,000 on promotion. He placed orders for $US22,000 of product in May 2008 and for $US46,000 of product in August 2008.

[69] However, Mr Jurysta was frustrated by continuing delays in meeting orders. The May 2008 order was not delivered for some three months and safety testing of the product had not been completed. There were concerns about quality issues. There were a number of complaints from retailers and consumers about sticky labels on the spreader bar. But the reason why Sycamore finally brought the relationship to an end and, in March 2009, cancelled orders for product totalling $US61,455, was as a result of its own financial difficulties. Sycamore’s mountain buggy business had come to an end, bringing with it “a lot of financial stress”. By July 2009, Sycamore was “under extreme duress”. It was winding down its operations and could not maintain its business with the BHC product line alone.

[70] Although, prompted by Mr Zambrzycki, the issue of patent protection was exercising the minds of the Hannahs and Mr Jurysta at this time, it was clearly not the reason why BHC’s relationship with Sycamore came to an end. Both companies were experiencing financial difficulties that had nothing to do with intellectual property protection for the baby hammock. BHC was seriously under-capitalised

and having difficulty meeting even the modest volume of orders generated by

Sycamore.

[71] A not dissimilar picture emerged in correspondence from BHC’s European distributor. There were complaints about delays in delivery, a lack of information and other communication problems, difficulties with pricing and the arrival of a wrong shipment. These led the European distributor to reactivate plans to develop its own baby hammock.

[72] I am left in no doubt that the problems encountered by BHC in overseas markets had little or nothing to do with the lack of intellectual property protection. They arose from structural and operational issues intrinsic to the BHC business.

Other causation issues

[73] I will briefly touch on other causation issues which by themselves would also have provided serious, if not insuperable, obstacles to BHC’s success even if it had established negligence.

[74] The first concerns the limited protection that would have been conferred by design or patent registration of BHC’s products. It was no part of BHC’s case that the hammock itself should have been protected by registration as a design or by patent. Indeed, it was common ground that it was not patentable. The experts differed on whether the stand and/or flexible spreader bar could have been protected, although it was accepted that, as the C-shaped stand had been displayed at a show in

2002, patent registration could not have survived a challenge. The protection afforded by registration of the stand would, in any event, have been of limited value. Design protection, in particular, could have been circumvented by minor design changes in a competitor’s product.

[75] The second difficulty is that BHC ceased relying on AJ Park’s advice in early

2007. Mr Zambrzycki began advising BHC at about this time, meeting with Mr and Mrs Hannah in New Zealand in March 2007. Based on their account of events, he advised them that the advice they claimed to have been given by AJ Park in 2004

was wrong. At that point, BHC could have taken steps to obtain patent or design registration.

[76] BHC had previously produced only the G-shaped stand developed in China (which had never been referred to AJ Park for advice). It had not displayed or sold either the C-shaped stand or the flexible spreader bar. Accordingly, BHC had the same rights to obtain protection as it claimed to have had two years earlier. It could have applied for patent or design registration in the United States as Hushamok had not, to that point, displayed a stand and had no registered designs outside New Zealand. As earlier mentioned, Mr Zambrzycki said he filed applications for design patents in the United States in 2007. Unfortunately, the documentation has been lost and it is not known exactly what the products or designs were.

Conclusion on causation

[77] For the reasons I have briefly discussed, BHC could not have showed that AJ

Park’s negligence would have led to loss.

Breach of fiduciary duty

Introduction

[78] Mr and Mrs Soboil, the founders of Hushamok, approached the Wellington office of AJ Park in November 2006. They had been favourably impressed by their experience of a baby hammock made by Nature’s Sway. They believed they could improve on the design. As United States citizens, they identified an opportunity to sell a baby hammock in the United States.

[79] After the initial approach by Mr and Mrs Soboil, an exchange of emails took place within AJ Park. The first was an email from Matt Adams of the Wellington office under the subject “conflict check” asking whether the firm was free to advise Mr Soboil and Hushamok on the manufacture and distribution of a baby hammock product in the United States. Potential competitors were identified as Amby, Nature’s Sway and BHC.

[80] The email elicited an immediate reply from Victoria Watts of AJ Park’s

Auckland office stating:

We act for the Baby Hammock company in respect of designs, trademarks and patent advice, and this would appear to be a direct conflict.

The email was copied to Messrs Butler, Blijlevens and Schaut.

[81] Several days later, Mr Adams sent an email to Messrs Butler, Blijlevens and Schaut asking one of them to ring him regarding the potential conflict. None of the three recalled discussing the issue when it arose or having a conversation with Mr Adams. Mr Butler, who was away at the time, said his understanding was that the matter was referred to a conflicts committee which comprised the senior litigation partners from the Auckland and Wellington offices.

[82] There is a handwritten note on a copy of the original email from Mr Adams, presumably made by him, reading as follows:

Rang Mark Soboil.

We are ok to do search

We are conflicted out of doing further work [indecipherable] not for Baby

Hammock

Mark will use a US attorney for other stuff.

[83] At some point AJ Park had a change of heart. The reason for this was never explained as neither Mr Adams nor anyone else who was involved in the decision or in advising Hushamok gave evidence. The record shows, and Mrs Soboil confirmed, that on instructions from Hushamok AJ Park obtained registration of a design for a hammock and three stand designs. Two applications were filed in April 2007 and the other two in September. Mrs Soboil said the Hushamok hammocks and stands were developed independently by designers at two companies, one in New Zealand, the other in the United States. She said Hushamok also filed a patent application in April 2007 for a combination of a flexible spreader bar and hammock. The patent examiner objected to the application because of a lack of unity of invention and a lack of novelty. The application was not pursued and was voided pre-acceptance.

The relevant duties

[84] In order to succeed in a claim for breach of fiduciary duty, BHC must show three things:2

![]() AJ Park owed it a fiduciary duty;

AJ Park owed it a fiduciary duty;

![]() AJ Park was in breach of that duty; and

AJ Park was in breach of that duty; and

![]() BHC suffered a loss arising out of a transaction or

circumstance to which the breach was material.

BHC suffered a loss arising out of a transaction or

circumstance to which the breach was material.

[85] It is not in issue that AJ Park owed fiduciary duties to both BHC and Hushamok. The relationship between solicitor and client is one in which the client reposes trust and confidence in the solicitor.3 It is accepted that patent attorneys are subject to the same obligation.

[86] The duty is pleaded as one requiring AJ Park to give undivided loyalty to BHC. That, and the duty to respect a client’s confidences, have their roots in the fiduciary nature of the solicitor-client relationship.4 The duty of single-minded loyalty requires that a solicitor should not act where the interests of two clients may conflict unless the material facts are fully disclosed to both clients and each consents. In some circumstances, even disclosure will not make it possible for the solicitor to act fairly and adequately for both clients.5

[87] In circumstances such as the present, the conflict of interest said to arise is better understood as a conflict in duties owed to different clients. As Professor Duncan Webb has written:6

It has been stated that a central aspect of the duty of loyalty is the obligation of a lawyer not to act for two clients whose interests conflict. However, this

2 Everist v McEvedy [1996] 3 NZLR 348 (HC) at 355 per Tipping J.

3 Hilton v Barker Booth & Eastwood (a firm) [2005] UKHL 8, [2005] 1 WLR 567 at [29].

4 Ibid, at [30].

5 Farrington v Rowe McBride & Partners [1985] 1 NZLR 83 (CA) at 90.

obligation is better expressed as an obligation of the lawyer to avoid any situation in which the duties of the lawyer owed to different clients conflict. The foundation of the obligation to avoid a conflict of duties is the fiduciary duty owed by the lawyer to each client independently.

[88] The point is also captured in the judgment of Richardson J in Farrington v

Rowe McBride & Partners.7 He said:

A solicitor’s loyalty to his client must be undivided. He cannot properly discharge his duties to one whose interests are in opposition to those of another client. If there is a conflict in his responsibilities to one or both he must ensure that he fully discloses the material facts to both clients and obtains their informed consent to his so acting[.]

[89] The duties which potentially conflict in this case are, on the one hand, the duty of disclosure and, on the other, the duty of confidentiality. The duty of disclosure requires the disclosure to a client of all relevant information in the lawyer’s possession. The duty of confidentiality precludes the use of information received under an obligation of confidence.

[90] The primary duty of undivided loyalty and the duties of disclosure and confidentiality are reflected in the rules of conduct and client care for lawyers set out in the Lawyers and Conveyancers Act (Lawyers: Conduct and Client Care) Rules

2008 which came into force on 1 August 2008. The primary duty of undivided loyalty is expressed as follows in r 5:

A lawyer must be independent and free from compromising influences or loyalties when providing services to his or her clients.

The duty of disclosure is in r 7:

A lawyer must promptly disclose to a client all information that the lawyer has or acquires that is relevant to the matter in respect of which the lawyer is engaged by the client.

The duty not to use confidential information is in r 8.7:

A lawyer must not use information that is confidential to a client (including a former client) for the benefit of any other person or of the lawyer.

7 Farrington v Rowe McBride & Partners, above n 4, at [90].

[91] The duties of confidentiality and of undivided loyalty are also found in cls

1.3 and 1.4 of the Code of Professional Conduct of the New Zealand Institute of

Patent Attorneys, Inc, which provides:

All members of the Institute shall have the following duties to the public:

1.3 Confidentiality

to keep their knowledge of each clients affairs confidential unless otherwise expressly authorised by the client to disclose same in particular circumstances

1.4 Conflicts of Interest

to endeavour to avoid situations in which their duty to one client is in conflict with their own interest or that of another client, and wherever any such conflict becomes apparent to take steps calculated to resolve it and to avoid prejudice to any such client

[92] The potential conflict arising here is between AJ Park’s duty to keep confidential any information acquired from or in the course of its acting for Hushamok and any duty to disclose that information to BHC. In order to determine whether a conflict may have arisen in this way, it is necessary to formulate the duty of disclosure with some precision.

[93] In McKaskell v Benseman8 Jeffries J described the duty in the following way:

A primary obligation of the fiduciary is to reveal all material information that comes into his possession concerned with his client’s affairs. The emphasis is on what is material, or essential. That is a matter of judgment by the solicitor on the facts of each case, for certainly he is not obliged to pass on trifling and insignificant detail.

In a passage now quoted as a footnote to r 7 of the rules of conduct and client care for lawyers, Jefferies J went on to say:

The fiduciary must, in dealing with those to whom he owes such an obligation reveal fully all circumstances that might affect their affairs, and is thus under a duty of disclosure not imposed on others.

[94] In Spector v Ageda,9 Megarry J expressed the duty by reference to “relevant knowledge”. He said:10

8 McKaskell v Benseman [1989] 3 NZLR 75 (HC) at 87.

9 Spector v Ageda [1973] 1 Ch 30.

A solicitor must put at his client’s disposal not only his skill but also his knowledge, so far as is relevant; and if he is unwilling to reveal his knowledge to his client, he should not act for him. What he cannot do is to act for the client and at the same time withhold from him any relevant knowledge that he has[.]

[95] Solicitors (and patent attorneys) cannot therefore discharge their primary duty to their clients unless they are free to use any knowledge they have and to disclose any information available to them that bears on their ability to advise their client. The information or knowledge that is relevant or material for that purpose depends on all the circumstances, including, importantly, the scope of the retainer. As with any aspect of the duty of single-minded loyalty, the duty may have to be “moulded

and informed” by the terms of the contractual relationship.11 The fiduciary

relationship must accommodate itself to the terms of the contract, so that it is consistent with, and conforms to, them.12

The scope of the retainer

[96] I have found that AJ Park was retained in 2004 to advise generally on intellectual property issues in relation to the hammock itself but not in relation to a stand or the flexible spreader bar development. After the Bennetts stand was acquired, AJ Park was asked to effect the assignment of copyright. It also advised BHC in relation to its manufacturing agreement with Danlong and later when BHC was concerned about internet violations of its copyright.

[97] The issue of patent and design protection was directly addressed for the first time in September 2006 when Mr and Mrs Hannah complained that AJ Park should have recommended patent and design protection for their hammock when they first saw AJ Park in August and October 2004.

[98] Mr Blijlevens reviewed the file and in a letter dated 26 September 2006, explained why AJ Park had not recommended filing patent or registered design

10 Ibid, at 48.

11 Hilton, above n 3, at [30].

CLR 1 at [91].

applications for the hammock in October 2004. He set out the requirements for patent and design protection. He explained why the hammock was not novel and inventive by virtue of the prior availability of the Nature’s Sway product. Dealing separately with the Bennetts stand, he said it could not be protected by patent or design because it was in the public domain when BHC considered it for use with the hammock. He concluded his letter under the heading “New Developments”:

Any development of your product that may make it sufficiently different to any existing product, may allow a patent and design to be filed. If any development has occurred, and the product with those developments has not been published or sold for more than one year, please let us know. We can then discuss patent and design protection for such developments. For example, you mentioned at our meeting that you were in the process of designing a new stand. Please keep the stand a secret until you’ve shown this to us so that we can advise you of appropriate protection for it.

[99] Between September and November, AJ Park undertook trademark work for BHC. It carried out a search of trademark registers in New Zealand and countries where BHC was marketing or intending to market its product. AJ Park applied, on BHC’s behalf, for trademarks in New Zealand and Australia. Soon afterwards, AJ Park accepted instructions from Hushamok.

[100] The relationship between BHC and AJ Park involved a series of discrete instructions to carry out particular tasks. While it is clear that BHC regarded AJ Park as their advisor on intellectual property matters generally, there was no retainer of an ongoing nature in which a range of tasks were undertaken pursuant to a general instruction.13 Accordingly, when AJ Park agreed to act for Hushamok, it was acting for BHC only for the purpose of registering a trademark. A retainer to advise in relation to the stand then said to be under development was in the future. A retainer to advise on patent and design issues in relation to the hammock (only) was in the past. It could not be regarded as having been activated as a result of AJ Park fielding

and responding to the complaint. On that issue it was merely being asked to review

its earlier advice.

13 See Webb, above n 6, at [5.4].

A duty to disclose?

[101] In the circumstances, there appears to be no basis for imposing a duty on AJ Park to disclose to BHC information it acquired in the course of acting for Hushamok. Such information was concerned solely with advancing Hushamok’s application for design and/or patent protection. It had no relevance to the work AJ Park was undertaking for BHC. It was not required to enable AJ Park to advise BHC. By reference to the terms of the retainer, there was no duty to disclose.

[102] There is, however, an additional relevant circumstance. That is the

expectation, made clear in the concluding paragraph of AJ Park’s letter of

26 September, that AJ Park would advise BHC in the future in relation to design and patent protection of any new development of its product. The question arises whether this may have led to an extended duty to avoid the potential for future conflict by declining to act for Hushamok.

[103] I heard expert evidence from senior and experienced practitioners who were emphatic that, even though AJ Park was not advising BHC on patent and design issues at the time, an irreconcilable conflict arose when AJ Park accepted instructions from Hushamok. Mr Robert Eades, who was called to give evidence on behalf of BHC, considered that a conflict arose because Hushamok was seeking protection for what was the same or substantially the same product as BHC sold and it would achieve a significant business advantage over BHC if it were successful. Mr Mark Eftimov, a registered patent attorney who also gave evidence on behalf of BHC, accepted that it was not uncommon for patent attorneys to act for two clients competing in the same product field but he considered an unacceptable conflict of interest would arise if a patent attorney acted for two New Zealand-based firms competing in the same field. He acknowledged that an actual or direct conflict would not occur unless and until one of the firms sought to enforce its rights or to challenge the patent or design registrations of the other. However, in his view, the potential for future conflict would be of such significance as to give rise to a breach of fiduciary duty at the outset if the patent attorney accepted instructions from the second firm.

[104] Mr Michael Hawkins, a patent attorney who gave evidence for AJ Park, took a contrary position. He said there would be no impediment to a patent attorney in AJ Park’s position acting for Hushamok provided it obtained confirmation that Hushamok’s products were its own original designs (so there could be no suggestion of any potential copyright infringement involving a third party which could be an existing client) and subject also to a search of the records of the Intellectual Property Office New Zealand (IPONZ) showing that there were no conflicting patents or designs owned by an existing AJ Park client. These conditions having been satisfied in this case, he saw no conflict arising.

Discussion

[105] It is commonplace for lawyers and patent attorneys to act for competitors. That in itself would not give rise to a disqualifying conflict. The critical issue – and the point on which Mr Eftimov and Mr Hawkins parted company – is whether a patent attorney will be in breach of duty to an existing client if, in accepting instructions from a competitor, the potential for future conflict arises.

[106] In my view, the mere risk of future conflict is insufficient to found a breach of duty and sets the bar too high. AJ Park’s duty of undivided loyalty to BHC was not compromised by its accepting instructions from Hushamok. It may have affected its ability to act for BHC in the future, if instructions to protect the stand under development had materialised, but AJ Park remained fully competent to discharge all existing duties to both clients.

[107] In argument, AJ Park’s duty to BHC was at times put more broadly as one which precluded it from doing anything which may disadvantage BHC. Even judged against that criterion, it seems to me that in acting for Hushamok AJ Park did not disadvantage BHC in any relevant sense.

[108] As Mr Brown QC submitted, registration of a patent or design is undertaken for the purpose of securing rights as a part of a strategy to acquire or protect a competitive edge. In that sense, registration will disadvantage any competitor in the field. That cannot be sufficient. Mere commercial disadvantage which would be

experienced by all competitors is not enough. There needs to be disadvantage of a kind which impacts on the intellectual property rights of another client.

[109] That did not occur here. On the face of it, Hushamok was able to register the design of its hammock because it had developed a sufficiently distinctive design. BHC had no legitimate interest in that design and no basis for opposing the grant of registration. There was no step which BHC could have taken in relation to the application, regardless of who had lodged it. The business advantage achieved by Hushamok’s registration of its designs were derived from its own independent developments. It was entitled to secure that development by registration which was effective against the world. Registration did not carry any special or distinct adverse implications for BHC.

[110] For these reasons, I am satisfied AJ Park did not breach its fiduciary duty to

BHC in accepting instructions to act for Hushamok.

Causation

[111] Even if, contrary to the view I take, AJ Park breached its fiduciary duty to BHC by acting for Hushamok, I do not think BHC could have showed that it would have suffered loss as a result of the breach. The design registrations effected by AJ Park on behalf of Hushamok did not in fact interfere with BHC’s rights in relation to either the C-shaped stand or the spreader bar. The stand could not have been registered because of prior disclosure (at the show in 2002 when it was exhibited at the Nature’s Sway stand). No attempt was made to register the spreader bar or the stand said to be under development in September 2006, except for the applications of uncertain scope made in the United States after Mr Zambrzycki began advising BHC in early 2007.

[112] Ultimately, registration simply gave effect to Hushamok’s right to obtain protection of designs independently developed. AJ Park’s involvement, whether or not in breach of fiduciary duty, made no difference.

Damages

Compensatory damages

[113] I will briefly consider damages for the purpose of ensuring that my findings on all important issues are recorded.

[114] The loss of profits claim of $53,105,743 was based on the calculations of Mr James Pampinella, an accountant based in San Francisco. He based his calculations on projections made by Mr Gilmore and Mr Jurysta. Mr Gilmore’s evidence led Mr Pampinella to estimate that BHC would have sold 475,557 hammocks and stands between 2008 and 2020 in New Zealand, Australia, Hong Kong, Singapore, the United Kingdom, Canada and Japan. Based on Mr Jurysta’s projections, he estimated that sales for the same period would have numbered

279,860 hammocks and stands in the United States and the European Union.

[115] Mr Pampinella defended the projections as reasonable against claims by Mr John Hagen, a chartered accountant called by AJ Park, that they were “unsubstantiated”, “guesstimates” and “just numbers with little or no meaning or substance”. I am, however, satisfied that the projections used by Mr Pampinella are quite unrealistic and cannot be relied on to found a loss of profits calculation.

[116] Mr Gilmore’s projections related, he said, to sales of a C-shaped stand which he saw as unique. I have concluded that the C-shaped stand was not part of BHC’s plans when Mr Gilmore was involved. He claimed to have made the calculations when he was talking to the Hannahs but I do not believe his projections were made at that time. In my view, they were created much later, specifically for the purpose of providing evidence for BHC. Mr Gilmore said the projections used models which took into account such factors as birth rates in the various markets. I do not believe there was any empirical or valid methodological basis for his calculations. Mr Gilmore acknowledged as much when he said that the projections for the New Zealand market were “really just gut feel”.

[117] Mr Jurysta’s projections appeared to be a genuine attempt to estimate likely sales. His business had enjoyed success with the mountain buggies and he used roughly equivalent growth curves to project baby hammock sales. But the two products have materially different characteristics and occupied quite distinct segments of the market. Every family has a pushchair or stroller, whereas only a small minority of parents buy a baby hammock. It is one of a range of options available for a young baby; a bassinette or a cot is preferred by most parents. The mountain buggy had features which set it apart from competing products. Among other things, it had three wheels instead of the usual four. In contrast, BHC’s baby hammock, even with some form of patent or design protection, would not have had the market to itself.

[118] The evidence of other baby hammock manufacturers and retailers confirmed that the projections relied on by BHC ignored the realities of the marketplace. Mrs Kate Hornblow was one of the pioneers of baby hammocks in New Zealand with her Nature’s Sway product. She described the baby hammock market as “a particularly niche market”. She said that in 17 years in the business she has sold

20,000 hammocks worldwide, of which 10,000 were sold in Switzerland during the period 1998 to 2004. She said her most successful markets are New Zealand, Scandinavia and Switzerland. She saw the United States as potentially profitable but difficult, particularly because of its litigious culture. Her fears in that regard proved justified as the deaths of two babies were attributed to products marketed by the Australian company, Amby Baby, leading to a recall and a negative impact on baby hammock sales generally in that market.

[119] Despite considerable efforts and expenditure on promotions, Hushamok found it very hard to break into the United States market, citing, among other things, safety concerns. Mrs Julie Soboil said there was a lot of competition in the market. She agreed that baby hammock sales would always have only a small share of the total market for nursery furniture. It could only grow with heavy investment in marketing which, to date, no company has been prepared to undertake. Mrs Soboil also said that safety issues and recalls by two manufacturers in the United States has adversely affected the market. Confidential sales figures disclosed by Mrs Soboil

confirmed her evidence and supported her view that the projections of Messrs

Gilmore and Jurysta were “fanciful”.

[120] Amby Baby has been in business since 1989. During that period it sold

15,000 units, on average less than one thousand per year in Australia and, between

2003 and 2009, a total of 24,000 units in the United States. For an equivalent period

Mr Jurysta had projected more than ten times Amby Baby’s actual sales.

[121] There is nothing in BHC’s limited track record to indicate that it would have exceeded the achievements of its competitors, with or without intellectual property protection. Its product was trialled by the “Children’s World” departments of Farmers Trading Company in 2005 to 2006. Despite the enthusiastic support of Farmers’ merchandisers, the product did not prove to be successful and was ultimately deleted from the Farmers range. BHC products did not sell particularly well in Europe or, for that matter, in the United States despite retailer demand following the 2007 Las Vegas trade show.

[122] Even if the domestic and overseas markets had the potential for sales at the level assumed by Mr Pampinella, BHC was in no position to exploit them. It was chronically under-capitalised. It was in no position to invest in the intellectual property protection it required or to promote and develop overseas markets. By

2009 it had bank borrowings of $430,000, of which $330,000 had been advanced to shareholders. Mr Hagen said that any money raised at that time would merely replace what shareholders had already borrowed. It would not have solved the company’s financial problems or given them the capital to expand in the way suggested by Mr Pampinella. BHC was, said Mr Hagen, technically insolvent.

[123] For completeness, and to conclude the discussion of compensatory damages, I will comment briefly on two aspects of Mr Pampinella’s calculation of damages with which Mr Hagen took particular issue.

[124] The first concerns the date from which lost profits should be calculated. Mr Pampinella calculated loss of profits as at the date of trial, using historical data to assist in determining pre-trial profits and future projections, discounted to achieve a

present value, to calculate post-trial damages. Mr Hagen said damages should be assessed as at the date of the breach, and calculated by obtaining a present value of profits projected from that date. In McElroy Milne v Commercial Electronics Ltd14

Cooke P said that, as the assessment of damages is ultimately a question of fact, there is no such thing as a rule as to the legal measure of damages applicable to all cases.15 That said, the general approach is to assess damages as at the date of the

breach unless justice requires otherwise.16

[125] I see no reason in this case why justice or other considerations require an assessment of damages at a later date. BHC’s actual results for the pre-trial period were depressed for a range of reasons. A calculation of profits lost for that period must rely on projections and assumptions not materially different from those required to project post-trial profits. I see no reason to depart from the general rule and, had I been required to determine compensatory damages, I would have adopted the approach advocated by Mr Hagen.

[126] The second major issue on which the experts parted company was whether projected profits should be determined on a pre-tax or post-tax basis. Mr Pampinella’s position was that, for the purpose of calculating the present value of future earnings, pre-tax profits should be used. Mr Hagen was insistent that the present value of future profits must be determined on the basis of cash flows calculated on an after-tax basis.

[127] I prefer Mr Hagen’s evidence on this point also. With support from a standard text17 he demonstrated that in order to determine the present net value of future profits, it is necessary to deduct the tax payable on each year’s profit in order

to calculate the sum available to the company for reinvestment or distribution.

14 McElroy Milne v Commercial Electronics Ltd [1993] 1 NZLR 39 (CA).

15 Ibid, at 41.

16 Ibid, at 49; Miliangos v George Frank (Textiles) Ltd [1976] AC 443 (HL) at 468; Johnson v

Perez [1988] HCA 64, (1988) 166 CLR 351.

[128] Mr Pidgeon relied on North Island Wholesale Groceries Ltd v Hewin18 as authority for the proposition that in New Zealand damages for future earnings are customarily determined on a pre-tax basis. But Hewin and other cases referred to by Mr Pidgeon are the exception that prove the rule. Hewin concerned the incidence of tax on a claim for wrongful dismissal. It has no application to a case such as the present where the computation of the present value of future projected profits is in issue.

Exemplary damages

[129] Even if, contrary to my finding, AJ Park had breached its fiduciary duty to BHC, an award of exemplary damages would not be justified. Outrageous conduct is required.19 At worst AJ Park’s conduct would have involved an error of judgment.

Result

[130] BHC’s claim fails in its entirety. AJ Park is entitled to costs. If the parties

are unable to agree, I will consider memoranda.

18 North Island Wholesale Groceries Ltd v Hewin [1982] 2 NZLR 176 (CA).

19 Bottrill v A [2002] UKPC 44, [2003] 2 NZLR 721.

NZLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.nzlii.org/nz/cases/NZHC/2011/686.html