|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

High Court of New Zealand Decisions |

Last Updated: 21 March 2012

IN THE HIGH COURT OF NEW ZEALAND WELLINGTON REGISTRY

CIV-2011-485-1371 [2012] NZHC 238

UNDER Section 64 of the Electricity Industry

Act 2010

IN THE MATTER OF an appeal of a decision of the Electricity

Authority

BETWEEN BAY OF PLENTY ENERGY LIMITED First Appellant

AND TODD ENERGY LIMITED Second Appellant

AND THE ELECTRICITY AUTHORITY First Respondent

AND MERIDIAN ENERGY LIMITED Second Respondent

AND MIGHTY RIVER POWER LIMITED Third Respondent

AND NEW ZEALAND STEEL LIMITED Fourth Respondent

AND NEW ZEALAND SUGAR COMPANY LIMITED

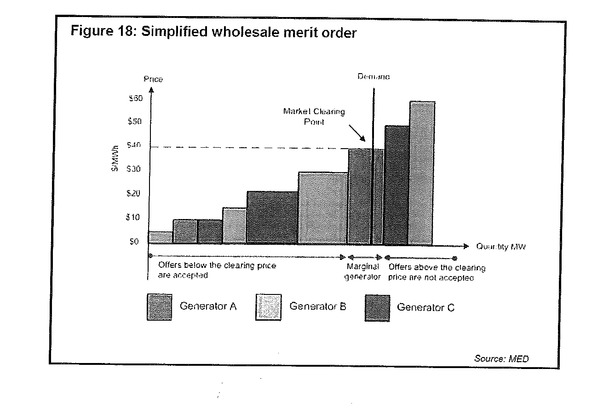

Fifth Respondent

AND POWERSHOP NEW ZEALAND LIMITED

Sixth Respondent

AND SWITCH UTILITIES LIMITED Seventh Respondent

AND VODAFONE NEW ZEALAND LIMITED Eighth Respondent

AND PULSE UTILITIES NEW ZEALAND LIMITED

Intervenor

BAY OF PLENTY ENERGY LIMITED V THE ELECTRICITY AUTHORITY HC WN CIV-2011-485-1371 [27

February 2012]

CIV-2011-485-1372

AND UNDER the Electricity Industry Act 2010

IN THE MATTER OF an appeal under section 64 of the Electricity Industry Act 2010 against a decision of the Electricity Authority that an undesirable trading situation developed on

26 March 2011

BETWEEN CONTACT ENERGY LIMITED Appellant

AND THE ELECTRICITY AUTHORITY First Respondent

AND MERIDIAN ENERGY LIMITED Second Respondent

AND MIGHTY RIVER POWER LIMITED Third Respondent

AND NEW ZEALAND STEEL LIMITED Fourth Respondent

AND NEW ZEALAND SUGAR COMPANY LIMITED

Fifth Respondent

AND POWERSHOP NEW ZEALAND LIMITED

Sixth Respondent

AND SWITCH UTILITIES LIMITED Seventh Respondent

AND VODAFONE NEW ZEALAND LIMITED Eighth Respondent

AND PULSE UTILITIES NEW ZEALAND LIMITED

Intervenor

CIV-2011-485-1373

AND UNDER the Electricity Industry Act 2010

IN THE MATTER OF an appeal under section 64 of the

Electricity Industry Act 2010 in respect of a final decision of the Electricity Authority that an undesirable trading situation developed on 26 March 2011

BETWEEN GENESIS POWER LIMITED Appellant

AND THE ELECTRICITY AUTHORITY First Respondent

AND MERIDIAN ENERGY LIMITED Second Respondent

AND MIGHTY RIVER POWER LIMITED Third Respondent

AND NEW ZEALAND STEEL LIMITED Fourth Respondent

AND NEW ZEALAND SUGAR COMPANY LIMITED

Fifth Respondent

AND POWERSHOP NEW ZEALAND LIMITED

Sixth Respondent

AND SWITCH UTILITIES LIMITED Seventh Respondent

AND VODAFONE NEW ZEALAND LIMITED Eighth Respondent

AND PULSE UTILITIES NEW ZEALAND LIMITED

Intervenor

Hearing: 28 November 2012

Counsel: A M Stevens and S B Kellett for Bay of Plenty Energy Limited and

Todd Energy Limited

J B M Smith and D A K Blacktop for Contact Energy Limited

J A Farmer QC, M Dunning, A Simkiss and A Rawlings for Genesis

Power Limited

D J Goddard QC and L A O'Gorman for Electricity Authority

J E Hodder SC and T D Smith for Meridian Energy Limited, NZ Steel

Limited, NZ Sugar Company Limited, Powershop NZ Limited, Switch Utilities Limited

M R Dean QC, J A Craig and G Holm-Hansen for Mighty River

Power Limited

J Scragg and O J Lund for Pulse Utilities New Zealand Limited

(as intervenor) Judgment: 27 February 2012

JUDGMENT OF RONALD YOUNG J

Table of Contents

Paragraph No.

Introduction [1] Background and facts [6] The Electricity Industry [8]

Wholesale spot market [17] Information about wholesale market trading [23] Wholesale hedge market [32] Retail market [34]

Events leading up to and on 26 March 2011 [35] The Authority’s decision [63] Error of Law [80] How to interpret the UTS statutory context [88] The appeal grounds [104] Discrete Errors of Law [113]

Previous decisions of the Electricity Commission [113] Failure to identify a contingency or event [119] Wrong standard of proof [124]

Untenable decision [153] Alleged errors [163] Exceptional and unforeseen circumstances [163] Exceptional situation? [167] Foreseen and foreseeability [173]

The definition of a squeeze and the approach of the Authority [190]

Was an abnormal situation required? [196]

Why did the circumstances of 26 March threaten trading such

that it would be likely to preclude orderly trading? [201]

Potential financial impact on industry participants not

enough for a UTS [221]

Demand forecast errors [228]

What is the significance of the events of 2 April for 26 March and the conclusion of the Authority that UTS occurred on

26 March? [235]

Was this a decision no reasonable decision maker could

make given the facts as found? [245]

HIGH PRICES [247]

NET PIVOTAL SITUATIONS ARE NOT UNIQUE AND THE AUTHORITY DID NOT FIND THAT ACTING IN A NET

PIVOTAL POSITION CONSTITUTED A UTS [248]

THE PRICES WERE NOT “UNFORESEEN” BECAUSE SOME

PARTICIPANTS DID FORESEE THEM AND TAKE ACTION [249]

THE OFFERS WERE IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE INTERNAL

PROCEDURES OF GENESIS [250]

GENESIS DID NOT CREATE A SQUEEZE [251]

THE BINDING OF THE CONSTRAINT DEPENDED ON THE ACTIONS OF SEVERAL PARTICIPANTS AND THEIR ACTIONS

WERE POSSIBLY NOT DIRECTED TO THE CONSTRAINT AT ALL [252]

GENESIS OFFERED HEDGES [253]

CONTACT’S DECISION NOT TO OFFER STRATFORD GENERATION CONTRIBUTED TO THE CIRCUMSTANCES WHERE PRICES

BECAME EXCEPTIONAL [254]

INACCURATE DEMAND FORECAST CONTRIBUTED TO THE

EVENTS OF THE DAY [255]

A UTS MUST BE A CONTINGENCY OR EVENT OUTSIDE THE NORMAL OPERATION FOR THE WHOLESALE MARKET FOR

ELECTRICITY [256]

THE EVIDENCE SHOWS THAT PRICE SIGNALS IN THIS SITUATION ARE EXACTLY THE PRODUCT OF A

FUNCTIONING MARKET [257]

A NUMBER OF PARTIES PAID MORE FOR ELECTRICITY ON THAT DAY BUT OVER TIME THEY WOULD BENEFIT BEING SUBJECT TO SPOT PRICES AND THEY ELECTED TO REMAIN

EXPOSED TO SPOT PRICES FOR THAT REASON [258]

THERE IS NO REASON WHY THOSE PARTIES WHO DID MANAGE THEIR POSITION THAT DAY SHOULD BE WORSE OFF THAN THOSE WHO DID NOT, NORMALLY THE

REVERSE SHOULD BE THE CASE [261]

THERE WAS NO EVIDENCE OF TRADING BEING THREATENED OR THAT THE SITUATION WAS LIKELY TO PRECLUDE ORDERLY TRADING OR THE PROPER

SETTLEMENT OF TRADES [263]

IMPROPER IMPOSITION OF A PRICE CAP [264]

Subclause (b) – any other mechanism under the Act? [271] Relevant and irrelevant considerations [276] Relevant considerations [278] Irrelevant considerations [285]

Use of a UTS for improper purpose [295] Alternative remedies to a price reduction [306] Conclusion [319] Supporting the Authority’s decision on other grounds [320] Costs [323]

Introduction

[1] At 10.30 a.m. on 26 March 2011 the interim wholesale price of electricity for

Hamilton and regions north of Hamilton went from $367/MWh to over

$19,000/MWh.1 It stayed about level until 5.30 p.m. that day with a later upward adjustment of price from what is known as the spring washer effect (explained later in this judgment).2 The wholesale prices during those seven hours on 26 March varied between $21,687/MWh to $23,047/MWh. After 5.30 p.m. on that day the wholesale price dropped initially to $2,373/MWh and by 8.00 p.m. it was

$179/MWh.

[2] Thirty-five companies including generators, wholesalers, retailers and consumers of electricity complained to the Electricity Authority (the “Authority”) that in terms of the Electricity Industry Participation Code 2010 (the “Code”) an undesirable trading situation (“UTS”) had arisen. They asked the Authority to reset the very high prices paid for electricity during that day.

[3] After an extensive enquiry the Authority concluded that a UTS had developed on 26 March and that the high interim prices should be reduced to $3,000/MWh for the relevant period on 26 March.3

[4] These appeals challenge that decision. Appeals from the Authority to this Court are appeals on questions of law.4 A number of parties including Mighty River Power (MRP), Meridian, New Zealand Sugar and New Zealand Steel gave notice opposing the appeals and made submissions supporting the decision of the

Authority on other grounds.

1 MWh = mega watt per hour.

2 At [59].

3 Electricity Authority, Final Decision on the Undesirable Trading Situation of 26 March 2011 and

Final Decision on actions to correct the Undesirable Trading Situation of 26 March 2011,

4 July 2011.

4 Electricity Industry Act 2010, s 64.

[5] This judgment firstly considers the background facts and electricity industry, then the Authority’s decision, followed by the relevant law, and finally the grounds of appeal including the additional grounds of support relied upon by the respondents for the Authority’s decision.

Background and facts

[6] The process undertaken by the Authority in establishing the facts is essentially inquisitorial. The Electricity Industry Act 2010 (the “EIA”) established the Authority. Section 16(1)(a) includes, amongst the Authority’s functions, the investigation and enforcement of compliance with relevant parts of the Act (there is also a Rulings Panel set up under the Act) and the Code. Section 46 empowers the Authority to obtain certain information from documents and interviews with “industry participants” for the purpose of an investigation for a breach of the Code.

[7] Industry participants are defined in s 7(1) of the Act in this way:

7 Industry participants

(1) The following are industry participants for the purposes of this Act: (a) a generator:

(b) Transpower: (c) a distributor: (d) a retailer:

(e) any other person who owns lines:

(f) a person who consumes electricity that is conveyed to the person directly from the national grid:

(g) a person, other than a generator, who generates electricity that is fed into a network:

(h) a person who buys electricity from the clearing manager: (i) any industry service provider identified in subsection (2).

(2) The following industry service providers are industry participants: (a) a market operation service provider:

(b) a metering equipment provider: (c) a metering equipment owner: (d) an ancillary service agent:

(e) a person that operates an approved test house: (f) a load aggregator:

(g) a trader in electricity:

(h) any other industry service provider identified in regulations made under section 109.

The Electricity Industry

[8] Some background regarding the electricity industry is essential to understanding what occurred on the days preceding, and on, 26 March 2011. This summary of the background of the electricity industry primarily relies upon the submissions provided by Genesis and to a lesser degree other participants in the appeal.

[9] The five major generators of electricity in New Zealand are Contact Energy Limited, Genesis Energy Limited, Meridian Energy Limited, Mighty River Power Limited and TrustPower Limited. There are other smaller generators including one of the appellants in this case, Bay of Plenty Energy Limited.

[10] Electricity in New Zealand is primarily generated from hydroelectric stations (more than 50 per cent). Electricity is also generated by gas, thermal, geothermal, diesel and wind power. Hydroelectricity is the least expensive to produce. When the availability of hydroelectricity is reduced (for example, in a drought) then more expensive generating options are used to make up the deficit (for example, a thermal plant using gas or coal).

[11] The national grid, owned by Transpower, transmits this electricity directly to ten large industrial users and then to 28 local lines companies. When the electricity is delivered to the local distribution companies the voltage is reduced at substations. The lower voltage electricity is distributed through retailers to consumers, both business and domestic.

[12] The wholesale market consists of generators offering electricity for sale to large industrial companies and retailers (to onsell). The retail market involves the sale of electricity by retailers to end users including smaller businesses and domestic users.

[13] Transpower is the System Operator (as owner of the national grid) and is responsible for managing transmission of electricity around New Zealand. This involves the obligation to ensure that the high demand for electricity in the Auckland region is met, in part, from the production of electricity around New Zealand including the significant South Island electricity supply from the hydro lakes.

[14] The importation of electricity to Auckland is mainly through six 220kV5

circuits from Whakamaru via Hamilton and Huntly to Auckland.

[15] The System Operator is responsible for ensuring that the demand for electricity around New Zealand is met on a second by second basis. Because electricity cannot be stored (or at least it is very expensive to do so) then supply must constantly meet a fluctuating demand. Physical supply and demand must always, therefore, be in balance to avoid a power “black out”. As the Authority noted in its

report on the System Operator:6

... determining the optimal combination of generating stations and reserve providers for each half hour trading period, instructing generators when and how much electricity to generate, and managing any contingent events that cause the supply demand balance to be disrupted. System Operations staff in Transpower’s control rooms undertake this work using sophisticated modelling and communications technologies.

5 kV = kilovolt.

[16] The electricity market in New Zealand involves trading in the wholesale and retail markets. The market has been regulated since 2004, with the more recent rules in the 2010 Act and Code. The wholesale market for electricity consists essentially of the spot market and the hedge market. Customers in the wholesale market can purchase electricity on the spot market or hedge market or in a combination of both.

Wholesale spot market

[17] Electricity is supplied by generators and taken by retailers and large industrial users at 225 nodes around New Zealand. Each node is simply a point within New Zealand where electricity is taken from or supplied to the national grid. Each day is divided into 48 trading periods of a half hour each. In each trading period a generator may offer to supply an identified quantity of electricity at an identified price or prices at a particular node or nodes. Prices are generally identified in bands of dollars per kilowatt.

[18] These offers may be submitted up to five days before supply through to

1.00 p.m. on the day before the supply is to take place. A generator can change or cancel a bid (for example, the amount of electricity offered or the price) up to two hours before the trading period to which the offer relates (for example, if the offer to supply is for the half hour period 10.00 a.m. to 10.30 a.m. then the offer to supply may be withdrawn or amended at any time up to 8.00 a.m. on the day of supply).

[19] As to the price, the offer may contain up to five bands per half hour trading period. There is no maximum offer price. The System Operator’s function is, for any half hour period, to accept offers to supply electricity starting at the lowest offer and moving up the price bands of the offers until demand is met. This “demand” level of electricity is then dispatched to meet the demand.

[20] The highest generator’s offer accepted in any trading period by the System Operator to meet demand then becomes the price paid for all the electricity offered and supplied in that trading period. And so although generator A may have offered to supply electricity at $10/MWh, if the last operator’s offer, which is accepted to meet demand, is $1,000/MWh then the generator who offered $10/MWh will also

receive the $1,000/MWh. This highest price is called the “market clearing price”. The generator whose price is the market clearing price is called the “marginal generator”.

[21] Attached to this judgment is a bar graph (figure 1) showing a simplified version of how the system of offers and dispatches of electricity works.7 Offer prices may vary between nodes. The System Operator will, therefore, want to send the lowest price electricity offered between nodes to satisfy demand at the lowest possible price. The capacity to send electricity around the system to satisfy demand at the lowest possible price is not unrestricted but is constrained by the electrical capacity of the lines carrying the electricity. The Code defines a constraint as:8

constraint means a limitation in the capacity of the grid to convey electricity caused by limitations in capability of available assets forming the grid or limitations in the performance of the integrated power system.

[22] Thus, there will be different prices at different nodes known as price separation.

Information about wholesale market trading

[23] Industry participants on the wholesale market have a variety of information provided by the System Operator upon which they can assess both price and demand for electricity each day and indeed hourly or less.

[24] The basic information is provided through the Wholesale Information Trading System (“WITS”). Market participants provide information about their bids and offers to the WITS, which delivers pricing, scheduling and other market data using the System Operator’s software model. Industry participants are entitled to the

information within the system. Some information is publicly available.

7 Genesis submissions, pg 18, fig 18.

8 Electricity Industry Participation Code 2010, 1.1(1).

[25] The first forecast information is the weekly dispatched schedule (“WDS”). This schedule is published each day at 1.30 p.m. It forecasts energy and reserved prices, whether there are any constraints (essentially restrictions on supply), known demand, electricity offered and scheduled generation outages for each trading period for the coming seven days.

[26] The second forecast document is the security dispatch schedule (“SDS”). It is published at 10.00 a.m. on the day before the trading day and is updated every two hours until dispatch. The forecast schedule is based on actual generation offers and the System Operator’s forecast of demand. It gives estimates of half hourly prices. It includes information about constraints and a particular adjusted schedule for winter.

[27] The third forecast schedule is the pre-dispatch schedule (“PDS”). This is published at 1.00 p.m. on the day before trading and is then updated every two hours. It makes price forecasts for half hour periods for each given trading period. It is based on bids by wholesale electricity purchasers and not on forecast load. In addition, both the SDS and PDS forecast expected generation, any constraints, demand and prices.

[28] Every four hours before each given trading period a schedule of dispatched prices and quantities (“SDPQ”) is produced. It is updated every 30 minutes at ten past, and twenty to, the hour. It shows forecast prices using the System Operator’s demand forecast. It includes energy and reserve prices as well as an aggregate forecast of demand, energy offered and scheduled generation.

[29] The final indicator is five minute prices which are published five minutes after dispatch but prior to finalisation of the prices by the pricing manager. These are indicative prices only and can differ from the final prices which are not finally determined until two working days after the trading period.

[30] It is generally accepted that the price forecasts in the SDS and SDPQ are more accurate than those in the PDS. However, it is notoriously difficult to predict demand in electricity consumption.

[31] This is a volatile market. As Genesis noted in its submissions each node (225 of them) can have a different price for each half hour trading period (48 per day). The Pricing Manager, NZX, is responsible for calculating and publishing final prices for each node and for each trading period, potentially up to 14,000 different prices per day.

Wholesale hedge market

[32] A hedge contract allows a fixed price for electricity supplied thereby avoiding the volatility of spot market prices. Currently these are typically bilateral contracts between two market participants. They agree to fixed prices for an identified supply of electricity to avoid the volatility of spot market prices. Hedging, unsurprisingly, commands a premium above average spot prices essentially for the elimination or reduction of risk in the spot market. However, despite the higher prices such an arrangement suits those market participants who favour certainty over risk. Analysis indicates that over the course of a year, on average, spot prices will be lower than hedge prices.

[33] Thus, in a hedge a buyer agrees to buy and a generator agrees to sell a particular amount of electricity at a particular node for a particular time at a particular price irrespective of the market (spot) conditions. There are many variations to this described simple hedge contract.

Retail market

[34] At a retail level most contracts are for fixed price and variable supply. Some larger businesses, however, have contracts which also expose them to spot price risk. Such businesses do not have direct access to the information system accessible by the industry participants but often use agents who do have access to such information. This can involve the requirement for urgent price advice when spot prices exceed a particular level.

Events leading up to and on 26 March 2011

[35] In late 2009 Transpower gave notice to industry participants of the need for maintenance on the Whakamaru C transmission line between Whakamaru and Otahuhu. This maintenance was delayed on a number of occasions and was eventually planned for 26 March 2011. Other maintenance outages were also planned for the Arapuni/Otahuhu line during this time. As a result, on 26 March two of the six 220kV circuits between Whakamaru and Otahuhu were to be closed down between 5 a.m. and 5 p.m. and three 110kV circuits from Arapuni to Otahuhu were also to be closed during this time. This left four 220kV lines for the electricity supply to Auckland through Whakamaru and two 110kV lines also for the supply of electricity from north of the Waikato.

[36] These outages were known as early as December 2010 as to the 220kV outages and the 110kV outages by 9 March 2011. These outages on the 26 March, therefore, lowered the electricity that could be sent to Auckland from the South to meet Auckland’s demand. Given the limitation imposed by these main demand outages (known as a constraint on supply) there were three generation plants which could supplement the “ordinary” supply and make up for the loss of capacity from maintenance: Genesis’ Huntly plant; Contact’s Otahuhu A and B plants; and MRP’s Southdown plants.

[37] On 21 March Transpower requested Genesis provide 650MW of electricity from its Huntly power station for 26 March. Genesis replied that such generation would be available “if prices supported it”. This request required Genesis to start a

250MW generator not otherwise required.

[38] By 22 March Transpower had entered the two maintenance outages in the WITS which notified all industry participants. After 22 March but before 25 March (but on a day uncertain) Genesis authorised the pricing of long volume electricity for

26 March at up to $20,000/MWh (this authorisation was required because of Genesis pricing policy).

[39] On 25 March at 9.51 a.m. Genesis moved 320kV of electricity from the

Huntly Power Station which it had offered at less than $100/MWh to the

$19,000/MWh band for the period of the constraint in supply (because of the loss of some transmission lines for maintenance between 5.00 a.m. and 5.00 p.m.) on

26 March.

[40] At 10.03 a.m. and 12.03 p.m. on 25 March the System Operator’s information available to industry participants showed the Whakamaru/Otahuhu (Auckland) constraint binding with forecast prices at Otahuhu between $200/MWh and

$500/MWh per trading periods on 26 March.

[41] At 12.58 p.m. Contact Energy withdrew 425MW previously offered for

26 March from its TCC plant at Stratford. It did so because its assessment was that prices would be low for 26 March and immediately thereafter and it was not economic, therefore, for it to run this station.

[42] Based on these changes the System Operator reassessed supply and demand. It included in the assessment the known constraint of transmission line maintenance and estimated demand. At 2.00 p.m. and 2.30 p.m. on 25 March the System Operator’s SDS system forecast prices for the Auckland area during the trading period 9.30 a.m. to 2.00 p.m. on 26 March at $20,000/MWh.

[43] At 3.12 p.m. on 25 March, about an hour after these very high forecast prices, MRP offered an additional 125MW of electricity from its Southdown plant in Auckland at $0.01/MWh. This offer of very low priced electricity had the desired effect. It reduced the SDS forecast prices for Auckland for the following day,

26 March to a maximum of $150/MWh.

[44] During the course of the afternoon MRP sought hedge cover for 26 March from Genesis. Genesis offered two 50MW tranches of hedge cover to MRP at respectively $350/MWh and $750/MWh. The offer had a deadline of 5.00 p.m. for acceptance and related to a period after the constraint from transmission line maintenance had ended.

[45] Shortly afterwards the System Operator published the forecast prices for Auckland for 26 March reaching a maximum of $150/MWh. This reduction in forecast prices seems to have been in response to MRP’s offer of very cheap electricity for 26 March.

[46] As a result of the drop in prices MRP decided not to accept the hedge price offers from Genesis and at 4.45 p.m. formally declined the offer. MRP did not seek hedge cover from Contact Energy. It believed that Contact did not have any spare capacity to offer as a hedge. At 5.00 a.m. on 26 March the transmission outages began.

[47] The System Operator seriously underestimated demand for 26 March, by as much as 120kV. This underestimate of demand for electricity played a pivotal part in the high prices for electricity on 26 March. If the level of demand for 26 March had been known on 25 March then it seems probable that the potential for high prices would have been predicted and probably avoided. Demand may have been able to be reduced and supply increased.

[48] The gate closes on offers to supply electricity two hours before each time period of the intended supply. Thus, an offer to supply, and the price and the amount, cannot be adjusted two hours or less from supply time. For example, for a supply for the half hour period commencing at 7.00 a.m. offers to supply a quantity and price of energy can only be adjusted prior to 5.00 a.m. that day.

[49] At 9.40 a.m. on 26 March, the SDPQ system indicated a price of

$1,800/MWh for the trading period commencing at 10.30 a.m. By 10.10 a.m. the

System Operator predicted a price of $20,000/MWh for 10.30 a.m., $6,000/MWh for

11.00 a.m. and $400/MWh for 11.30 a.m.

[50] The System Operator then reduced the limit for the Whakamaru/Otahuhu transmission lines reducing the capacity that the lines could carry from 404MW to ultimately 380MW on two occasions at 10.40 a.m. and 11.10 a.m. Part of the responsibility of the System Operator is to ensure that the transmission lines are not asked to carry an electrical load that may endanger the integrity of the lines. Part of

the System Operator’s function, therefore, is to regularly assess and reassess the proper and safe capacity of the transmission lines, particularly where there are, as here, constraints on supply. This reduction in transmission line capacity on

26 March therefore further reduced the supply of electricity for Auckland.

[51] At 10.30 a.m. Genesis moved 20MW of Huntly generation from a low price band offer of $0.01/MWh to a high price band offer of $19,000/MWh for the trading periods 28 (2.00 p.m. to 2.30 p.m.) to 35 (5.30 p.m.).

[52] At about this time MRP moved 550MW of energy it had offered in the Waikato from a low to a high band price. MRP said its purpose was to reduce the transmission constraint across the Waikato and areas north of Hamilton. MRP said that its objective was to reduce price separation across the constraint to the north. The intention was to reduce the impact of the constraint binding by reversing the physical flow of electricity and to balance losses to MRP north of the constraint.

[53] I note the Authority’s initial view was that MRP’s “offer behaviour was consistent with an attempt to bring about a market squeeze affecting the rest of the North Island”.9 However, the Authority accepted MRP’s explanation for their action as a “logical” reaction to the high prices brought about by Genesis Energy’s high offer prices for its Huntly units.10

[54] At 1.00 p.m. Meridian contacted Genesis and requested hedge cover clearly in response to the high prices. Genesis advised that no hedge cover was available. Meridian asked Genesis again for a hedge and at 4.43 p.m. Genesis offered 30MW at

$10,000/MWh from 7.00 p.m. to 8.00 p.m. on 26 March. This offer was declined by

Meridian, unsurprisingly given the offer was outside when the constraint would end.

9 Decision of Electricity Authority at [147].

10 Decision of Electricity Authority at [148].

[55] At about 3.00 p.m. Transpower advised industry users that the transmission outage due to end at 5.00 p.m. was being extended to 8.00 p.m. However, as it turned out the outage ended at 5.30 p.m. At 5.30 p.m., as the transmission line constraint ended, prices dropped remarkably.

[56] Apart from Meridian and MRP’s reaction other industry participants also reacted to the high prices on 26 March. Some generators increased generation to benefit from the high prices. Some large industrial users reduced their use of electricity as they were able and thus reduced demand.

[57] The Authority subsequently received 35 complaints about the high prices on

26 March all claiming that the circumstances constituted a UTS. Losses by wholesalers, retailers and businesses from the high prices on 26 March were estimated to be around $45–$50 million.

[58] I have already detailed the interim prices for electricity during the seven hours between 10.30 a.m. and 5.00 p.m. that day. The ultimate prices charged for electricity for 26 March were subsequently published by NZX. They were typically higher than the interim offer prices that day because of the spring washer effect.

[59] The Authority in its submissions described the spring washer effect in this way:

4.1 As referred to in the note to Table 1 of the Consolidated decision at paragraph 123 (R0125), a high spring washer price is the most common mechanism by which a price higher than the offer price of the most expensive dispatched generation on the national transmission grid can occur. On 26 March 2011, a spring washer effect occurred between 10am and 5:30pm.

4.2 High spring washer prices occur at nodes where the SPD model has to replace multiple units of low-priced generation with high-priced generation so that an additional unit of generation can be delivered to those nodes whilst meeting the transmission constraints built into the SPD model.

4.3 The “spring washer” pricing effect occurs when there is a constraint within a transmission loop. For security, the transmission system includes many parallel paths. These parallel paths can form loops within the transmission system. The laws of physics determine how power flows from the transmission system. As a matter of physics, when there is a loop power cannot be made to flow only in one

direction. Rather, power flows will split across parallel paths according to the impedances on each side of the loop.

4.4 If one side of the loop is weaker than the other the system operator will need to re-dispatch generation to avoid overloading this weaker link. This weaker link is referred to as a transmission constraint and the re-dispatch of generation, to avoid overloading this link, will impact on the marginal price of supplying electricity at each point around the loop. In particular, price separation will occur either side of this transmission constraint.

4.5 Depending on whether a generator is a net seller or a net purchaser on each side of the constraint, such a generator can seek to influence whether a constraint binds:

(a) If it is a net seller on the high price side a party might want to cause a constraint to bind. By putting low price offers on the low price side, more energy will flow into the circuit that is constraining because of the incentive to get that low price generation into the high price region.

(b) If it is a net purchaser on the high price side it may want to remove the constraint. By putting high price offers on the low side, less will be generated there, and by putting low price offers on the high price side, more will be generated within the high price region, thereby reducing the import through the relevant constrained transmission circuit.

[60] As it turned out Genesis’ Huntly electricity was needed to manage the

demand on 26 March from about 10.30 a.m. through to the end of the outage at

5.30 p.m. Genesis was, during these seven hours, in what is known as a net pivotal position with respect to the supply of electricity north of Hamilton on 26 March. Essentially, therefore, electricity demand for that area required Genesis to supply additional electricity from its Huntly plant to match demand. A net pivotal position

was described by the Authority in its decision in this way:11

Explanation of net pivotal

A generator is net pivotal when the quantity of generation required from it to prevent non-supply of some load in a region is greater than the generator’s own load commitment in the region. Under these circumstances, it is profitable for a net pivotal generator to increase its offer prices as the additional revenue it earns will exceed its additional costs (from purchasing electricity from the wholesale market and meeting hedge contract commitments).

11 At [116].

Generators are net pivotal in only rare circumstances, but pivotal situations, where the generator’s load commitment is greater than its non-discretionary generation, are relatively common. A pivotal generator has no incentive to offer higher prices, as it would end up purchasing more electricity at the higher prices than it generated. For example, in the South Island, Meridian Energy is usually pivotal, but has only been net pivotal approximately 2.0% of the time since 1 January 2007, and this percentage will decrease significantly following the commissioning of Pole 3 of the high voltage direct current (HVDC) link between the North Island and the South Island.

An analysis of the net pivotal status of Genesis Energy in the Auckland region from 2007 to 2011 has identified only five half hour trading periods when it might have been net pivotal (apart from 26 March 2011). This analysis was conducted by solving every trading period over the above time period with all offers of Genesis Energy’s Huntly generation plant above

$100/MWh increased to $20,000/MWh.

[61] Once Genesis knew or assessed it was probably in this position of control it could increase prices to reflect what was, in effect, its monopolistic position.

[62] On 2 April what is described by some parties to this litigation as a similar situation to 26 March arose. There were planned outages of transmission lines for

2 April 2011. However, the prices that resulted on 2 April were considerably lower than 26 March. Genesis had less electricity in the highest price band on 2 April compared with 26 March. Some firms who had been seriously affected by the events on 26 March hedged their price for 2 April, others reduced demand.12

The Authority’s decision

[63] The Electricity Industry Participation Code 2010 defines an undesirable trading situation as:13

Undesirable trading situation means any contingency or event–

(a) that threatens, or may threaten, trading on the wholesale market for electricity and that would, or would be likely to, preclude the maintenance of orderly trading or proper settlement of trades; and

(b) that, in the reasonable opinion of the Authority, cannot satisfactorily be resolved by any other mechanism available under this Code; and

(c) includes, without limitation,–

12 See [235] to [244] for a discussion on 2 April events.

13 At 1.1(1).

(i) manipulative or attempted manipulative trading activity; and

(ii) conduct in relation to trading that is misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive; and

(iii) unwarranted speculation or an undesirable practice; and

(iv) material breach of any law; and

(v) any exceptional or unforeseen circumstance that is at variance with, or that threatens or may threaten, generally accepted principles of trading or the public interest

[64] Clause 5.1 of the Code empowers the Authority to investigate if it suspects a UTS. Clause 5.2 identifies the actions the Authority may take if it finds a UTS. It provides as follows:

5.2 Actions Authority may take to correct undesirable trading situation

(1) If the Authority finds that an undesirable trading situation is

developing or has developed, it may take any of the steps listed in subclause (2) in relation to the wholesale market that the Authority

considers are necessary to correct the undesirable trading situation.

(2) The steps that the Authority may take include any 1 or more of the following:

(a) suspending, or limiting or curtailing, an activity on the

wholesale market, either generally or for a specified period: (b) deferring completion of trades for a specified period:

(c) directing that any trades be closed out or settled at a specified price:

(d) giving directions to a participant to act in a manner (not

inconsistent with this Code, the Act, or any other law) that will, in the Authority’s opinion, correct or assist in overcoming the undesirable trading situation.

(3) The participant must comply promptly with a direction given to it in writing.

(4) Neither a participant nor the Authority is liable to any other

participant in relation to the taking of an action, or an omission, that is reasonably necessary for compliance with an Authority

direction under this clause.

[65] Subsequent to the receipt of the complaints of a UTS the Authority followed the process set out in its “Guidelines for Participants on Undesirable Trading Situations”. Essentially this involved the gathering of information from complainants and those involved on 26 March, undertaking an analysis of the information, preparing and releasing a draft decision for comment from complainants and other participants, reconsidering the draft in view of the comments

made and reaching and publishing a final decision. It also reached a final view as to the appropriate remedial action.

[66] The Authority interpreted the definition of a UTS as always requiring that (a) and (b) are established. It concluded that although the examples in (c) can be a UTS they would only be a UTS if those factors in (a) and (b) were also present.14

[67] The Authority considered that s 15 of the EIA provided an economic context for its interpretation of a UDS.15 Section 15 provides as follows:

15 Objective of Authority

The objective of the Authority is to promote competition in, reliable supply by, and the efficient operation of, the electricity industry for the long-term benefit of consumers.

[68] And the Authority said:

[29] The economic rationale for UTS provisions is to achieve operationally efficient and competitive markets. In voluntary marketplaces, market providers strive to attract buyers and sellers by adopting rules that promote operationally efficient trading and rules aimed at giving buyers and sellers confidence in the market.

...

[31] UTS provisions are adopted by market providers because they cannot foresee all future eventualities and hence cater for these in the market’s rules. Also, some practices are particularly difficult to specify in the rules, and so are better covered by generic UTS-type rules.

[32] As market providers have strong incentives to enforce UTS provisions to further the efficient operation of the market and build confidence in it, UTS provisions often given broad discretion to market providers to deal with practices that threaten trading on the market in some manner, such as practices that disrupt orderly trading or the proper settlement of trades. Having the ability in certain circumstances to constrain the commercial decisions or actions of market participants is common to most organised markets.

14 Decision of Electricity Authority at [15] to [19].

15 Decision of Electricity Authority at [25] to [26].

[69] And further, it said:

[33] ... Based on the general economic rationale for UTS provisions given above, the UTS provisions in the Code are consistent with facilitating and encouraging competition (limb 1 of the Authority’s statutory objective) and increasing the efficiency of the electricity industry (limb 3).

[70] In its decision the Authority summarised the various allegations made by the complainants and related the complaints to the definition of a UTS and the examples given in clause (c) of the definition.

[71] It rejected the allegation that there had been “a material breach of any law

which constituted a UTS under the Code”.16

[72] The allegation of manipulation or attempted manipulation of trading activity17 by Genesis Energy was also rejected. As to the allegation of manipulative conduct, the Authority found that Genesis’ strategy around 25, 26 March was consistent with managing its own risk of being able to supply all the electricity it had agreed to supply as well as (as it was entitled to) maximising the price it received for the electricity it generated.

[73] Further, the Authority considered whether Genesis had taken advantage of market power to achieve high prices and thereby engaged in manipulative behaviour. It said:

[108] The UTS Committee notes there is no price cap on offers made in the wholesale market for electricity, and in its view offering generation at high prices is not per se evidence of manipulative or attempted manipulative trading activity. Moreover, Genesis Energy submitted its $20,000/MWh offers to the market the day before the transmission constraint occurred, rather than just before gate closure.

[74] As to misleading or deceptive conduct the Authority said:18

[119] This limited ability of Genesis Energy to forewarn participants, coupled with the fact that Genesis Energy has made offers at $10,000/MWh over an extended period, does not support an allegation of misleading or deceptive conduct.

16 Clause (c)(iv).

17 Clause (c)(i).

18 Clause (c)(ii).

[75] As to other conduct threatening orderly trading, it posed three questions for consideration:19

[131] The UTS Committee considered:

(a) whether Genesis Energy was in a position to determine prices in a significant portion of the wholesale market for electricity on 26 March 2011;

(b) whether parties exposed to those prices had time to seek supply from other sources or curtail their demand, and as a result;

(c) whether those prices would be likely to undermine the wholesale market for electricity to such an extent that they satisfy the requirements of the definition of a UTS.

[76] It answered the three questions by concluding that Genesis was in a position to determine prices in a significant portion of the wholesale market for electricity on

26 March, that parties exposed to those prices did not have time to seek supply from other sources or curtail demand, and that in these circumstances:

[150] The exceptionally high interim prices on 26 March 2011 are not the result of an underlying supply-demand imbalance, e.g. inadequate capacity or fuel, and they appear to bear no resemblance to any underlying or unavoidable cost. It is in the public interest to have an electricity market in which all participants can be confident prices are competitively determined. If participants observe that prices are greatly divorced from supply-demand conditions and are excessively higher than underlying costs, they will lose confidence in the integrity of the market arrangements and the incentive structures surrounding the wholesale market for electricity may be greatly damaged.

...

[153] UTS claims in regard to 26 March 2011 and responses to the Authority’s information requests in regard to 26 March 2011, indicate that buyer confidence in the wholesale market for electricity appears to have been seriously undermined through the combination of exceptionally high prices (in the absence of an underlying supply-demand imbalance) and buyers’ lack of awareness of these prices until after the events had occurred.

...

19 Clause (c)(iii) and (c)(v).

[156] The UTS Committee’s view is that an exceptional and unforeseen circumstance occurred during trading periods 22 to 35 on 26 March 2011. The application of a squeeze in the wholesale market for electricity resulted in prices at exceptional levels in Hamilton and regions north of Hamilton. Counterparties trading in those regions had good reason to believe, until it was too late for them to take actions to avoid incurring liability to pay the prices, the exceptionally high offer prices at Huntly would not translate into market prices.

[157] In addition to the transmission outages and the absence of TCC generation offers in the market, a key contributing factor to the situation was the under-forecast of demand. This meant the exceptional prices were forecast only briefly on the afternoon of 25 March 2011, and then not until almost real time following Mighty River Power offering its Southdown generation into the market. This reduced the information available to participants and demand-side parties in the preceding 24 hours, and reduced the time for any response.

[158] The UTS Committee’s view is that the exceptionally high interim prices on 26 March 2011 are the result of a market squeeze, which is an undesirable trading practice, rather than an underlying supply-demand imbalance. If these interim prices are allowed to become final prices, they threaten to undermine confidence in the wholesale market for electricity. The UTS Committee’s view is that the events of 26 March 2011 may have threatened trading on the wholesale market for electricity and would be likely to have precluded the maintenance of orderly trading.

[159] The UTS Committee notes that, had the exceptionally high prices resulted from a genuine scarcity of electricity supply, and had the high offer prices been well signalled in advance, then the UTS Committee is unlikely to have found that the events of 26 March 2011 constituted a UTS, as it is important that price is used to signal scarcity to industry participants.

[77] And, in summary, it said:

[162] The reasons for this view may be summarised as follows:

(a) Genesis Energy’s generation offers set the market prices for Hamilton and regions north of Hamilton during trading periods 22 to 35 on 26 March 2011 and parties exposed to prices in the wholesale market for electricity in those regions had good reason to believe the exceptionally high offer prices at Huntly for those trading periods would not translate into market prices, until it was too late for them to take actions to avoid incurring liability to pay the prices; and

(b) the high interim prices on 26 March 2011, if they are allowed to become final prices, threaten to undermine confidence in the wholesale market for electricity, and threaten to damage the integrity and reputation of the wholesale market for electricity.

[78] The Authority then considered what could or should be done to correct this

UTS. They said:

[165] To this end, the design of the remedy ought to be directed at restoring prices in the wholesale market for electricity to the level they would have been had buyers been aware that Genesis Energy would be net pivotal on 26 March 2011 and those buyers had had the opportunity to arrange an alternative source of supply or to curtail demand.

[79] They concluded that a $3000/MWh price cap for the seven hour period on

26 March was appropriate. In particular they said:

[188] The $3,000/MWh offer price cap is intended to remove the effects of the market squeeze, while retaining incentives on participants that are aligned with those in a workably competitive market. In a situation where there is a willing buyer and a willing seller, a net pivotal generator should be able to price up to the economic alternative of the buyer, which would approximate the LRMC of a new entrant generation option or the opportunity cost of electricity for consumers (i.e. the price at which demand response occurs). As noted earlier, the Code restricts the remedies of a UTS to only those interventions necessary to correct the UTS. The UTS Committee considers that setting a cap on Huntly offer prices at SRMC would go further than just correcting the squeeze component of the UTS, while setting a cap on Huntly offer prices above $3,000/MWh would not go far enough to correct the squeeze.

Error of law

[80] This appeal is an appeal on a question of law. The Authority’s function was to correctly interpret the meaning of the relevant provisions in the EIA and the Code and apply this law to the facts as they found them to be.

[81] The appellants’ case is that the Authority made errors of law and reached an untenable conclusion. An error of law can occur if the Authority took into account an irrelevant matter, failed to take into account a relevant matter, misinterpreted a relevant statutory or Code provision or reached a conclusion, when applying the

facts to the law, which is so untenable it cannot be allowed to stand.20

20 Bryson v Three Foot Six Ltd [2005] 3 NZLR 721 (SC); Vodafone NZ Ltd v Telecom NZ Ltd

[82] It is important to keep in mind in making these assessments that the Authority is an expert body in the electricity industry and that this expertise plays an important part in its fact finding.21 Many of the decisions in this area are judicial review decisions. There is a clear difference between review and, as here, appeal. Here, a direct challenge to the correctness of the decision is authorised. Having said that, however, Parliament has decided to use an expert body to oversee the electricity industry. Section 13 of the Electricity Industry Act requires the Minister, who recommends persons for membership of the Authority, to ensure that amongst its

members the Authority has those who have knowledge and experience of the electricity industry, consumer issues and business generally.22

[83] The appellants’ case is built on both types of error of law. They say the Authority’s decision applied law to the facts as found by them but reached a clearly untenable conclusion. They also say that the Authority made a number of errors of interpretation in the meaning of the definition of the UTS which caused the application of the wrong legal test to the facts. Finally, the appellants submit the Authority misconstrued the extent or scope of its powers.

[84] In considering whether a decision is untenable it is not enough that an appellate Judge would have come to a different view on the facts as found by the Authority.23 It requires a conclusion that the decision made by the Authority was not legitimately available on the facts found. The Supreme Court in Bryson v Three Foot Six Limited stated:24

An ultimate conclusion of a fact-finding body can sometimes be so insupportable – so clearly untenable – as to amount of an error of law: proper application of the law requires a different answer. That will be the position only in the rare case in which there has been, in the well-known words of Lord Radcliffe in Edwards v Bairstow, a state of affairs “in which there is no evidence to support the determination” or “one in which the evidence is inconsistent with and contradictory of the determination” or “one in which the true and only reasonable conclusion contradicts the determination”. Lord Radcliffe preferred the last of these three phrases but he said that each propounded the same test. In Lee Ting Sang itself the Privy

21 Major Electricity Users’ Group Inc v Electricity Commission [2008] NZCA 536 at [56].

22 Electricity Industry Act 2010, s 13(b).

23 Vodafone NZ Ltd (SC) at [53].

24 At [26].

Council concluded that reliance upon dicta of Denning LJ in two cases “of a wholly dissimilar character” may have misled the Courts in Hong Kong in the assessment of the facts and amounted in the circumstances to an error of law justifying setting aside concurrent findings of fact. Their Lordships were of the opinion that the facts pointed so clearly to the existence of a contract of service that the finding that the applicant was working as an independent contractor was, quoting the words of Viscount Simonds in Edwards v Bairstow, “a view of the facts which could not reasonably be entertained”, which was to be regarded as an error of law. In Lee Ting Sang the facts demonstrated so clearly that the applicant was an employee that it was the true and only reasonable conclusion.

[85] There was some discussion between counsel for the appellants and respondents about whether this Court should allow the Authority as an expert body a reasonable degree of tolerance or a margin of appreciation in considering such appeals. Unsurprisingly, those who supported the appeal sought to distinguish the margin of appreciation cases. Those who supported the Authority’s decision endorsed that concept. In the end it does not seem to me to be helpful for me to embark upon a discussion either of the cases or the principles. In my view they simply do not in any significant way arise in this case.

[86] As the Supreme Court noted, the words of Lord Donaldson MR in Piggott

Brothers & Company Limited v Jackson [1992] ICR 85 (CA):25

What matters is whether the decision under appeal was a permissible option.

[87] I consider next the background to the definition of a UTS and the factors which will relevantly affect its interpretation. I then consider the appellants’ alleged errors of law relating to the meaning of a UTS in the context of this case as they arise from a consideration of the appellants’ submissions.

How to interpret the UTS statutory context

[88] At the beginning of its decision the Authority set out the basis upon which it interpreted the definition of a UTS. It said that, at cl 5.5 of the Code the Authority

was required to “restore normal operation of the wholesale market as soon as

25 At 92.

possible” after a UTS. And so the inference was that a UTS could not constitute the

“normal operation” of the market.

[89] The Authority noted s 15 of the EIA identified the statutory objectives of the

Authority. That section provides as follows:

15 Objective of Authority

The objective of the Authority is to promote competition in, reliable supply by, and the efficient operation of, the electricity industry for the long-term benefit of consumers.

[90] The Authority therefore considered how the statutory objectives relating to the UTS provision in the Code influenced the interpretation of a UTS. The Authority said:

[29] The economic rationale for UTS provisions is to achieve operationally efficient and competitive markets. In voluntary marketplaces, market providers strive to attract buyers and sellers by adopting rules that promote operationally efficient trading and rules aimed at giving buyers and sellers confidence in the market.

[30] In particular, market providers adopt rules aimed at giving buyers confidence that suppliers’ goods and services are what they say they are, contract terms are transparent and prices are competitively determined. Likewise, market providers adopt rules aimed at giving sellers confidence that buyers are genuine and will meet their payment terms. Undesirable practices by a few buyers and sellers harm other market users, and they also harm the market provider by deterring some parties from using the market.

[31] UTS provisions are adopted by market providers because they cannot foresee all future eventualities and hence cater for these in the market’s rules. Also, some practices are particularly difficult to specify in the rules, and so are better covered by generic UTS-type rules.

[32] As market providers have strong incentives to enforce UTS provisions to further the efficient operation of the market and build confidence in it, UTS provisions often give broad discretion to market providers to deal with practices that threaten trading on the market in some manner, such as practices that disrupt orderly trading or the proper settlement of trades. Having the ability in certain circumstances to constrain the commercial decisions or actions of market participants is common to most organised markets.

[91] And in summary, the Authority said:

[33] As noted above, the overarching test contained in the Code’s UTS provisions is that a UTS is “any contingency or event that threatens, or may threaten, trading on the wholesale market for electricity and that would, or would be likely to, preclude the maintenance of orderly trading or proper settlement of trades”. Based on the general economic rationale for UTS provisions given above, the UTS provisions in the Code are consistent with facilitating and encouraging competition (limb 1 of the Authority’s statutory objective) and increasing the efficiency of the electricity industry (limb 3).

[92] The thrust of the appellants’ criticism of this analysis is that there was too little focus on the words of the definition of a UTS. This lack of focus on the words, together with the broad contextual analysis taken led the Authority to in fact apply a too broad a test to a UTS.

[93] Bay of Plenty Energy submitted, for example, that the proper interpretation of clause (a) of the definition of a UTS was:

[49] In summary, the ordinary meaning of the Orderly Trading Element is that the contingency or event must be one that would, or is likely to, stop ongoing organised trading settlement of trades in accordance with the EIA and Code generally; or

[94] This submission suggests that the appropriate interpretation of clause (a) requires the likelihood that ongoing organised trading will stop as a result of the “event” which is said to be the UTS.

[95] Contact submits that the relevant context illustrates that the meaning of a UTS is not solely driven by competition issues but is related primarily to the smooth functioning “of markets and institutions within the electricity industry aside from competition issues”. They stress that orderly trading is concerned with “inputs” not “outputs”.

[96] I am satisfied the Authority’s approach to the interpretation of the definition of a UTS contained no error of law. The Authority illustrated it was conscious that it was interpreting the meaning of the definition of a UTS and the words contained therein. It also understood there was a statutory context to be taken into account as

well as an assessment of the purpose of the UTS. No error has been identified in this approach which is clearly correct.

[97] The Authority approached the meaning of the word “orderly” as something more than the completion of trades as anticipated by the Code. In my view this was correct. “Orderly”, in this context, is concerned with completion of trades as anticipated by the Code in a technical sense but is also concerned with a wider meaning of orderly, including the idea that orderly trading includes, for example, that all market participants would be trading on a level playing field. This is well illustrated by the examples in clause (c) of the definition of a UTS. They illustrate that trading which is not orderly could arise from manipulative conduct or illegal conduct or indeed from trading which threatens the public interest. Many of the examples in clause (c) have an aspect of ensuring that all trades are treated the same.

[98] And so a market which has been, for example, manipulated ((c)(i)), or misled or deceived ((c)(ii)), or where a relevant breach of the law has occurred ((c)(iv)), all involve an imbalance arising from the actions of the perpetrator of the event which will often result in an imbalance in knowledge about the market.

[99] And so to continue the level playing field example, “orderly” would require that market traders be equally well informed of market conditions. What is “orderly” in this context the Authority are uniquely qualified to assess.

[100] The idea of an orderly market can, as the Authority also recognised, be assessed against the Authority’s statutory objectives. If the Authority’s job, in part, is to ensure the functioning of the electricity market by promoting its statutory objectives,26 then an assessment of the orderly trading element will inevitably involve an assessment of how the particular events under scrutiny affect these

statutory criteria.

26 Electricity Industry Act 2010, s 15.

[101] And so, the preclusion of orderly trading does not require that trading is or is likely to halt. Trading may continue but orderly trading, that is orderly trading in the sense described by the Authority, will not continue. An event would have occurred which has so affected the market that if it is allowed to continue it means that trading will not, for example, be on a level playing field. To continue that example if market participants do not have equal access to relevant market information it is easy to see that orderly trading is likely to be precluded given an important aspect in orderly trading is equal access to market information.

[102] Trading might continue in that situation but it will not be orderly because it will not have one of the important ingredients of an orderly market, equal access to market information.

[103] I am satisfied that the Authority’s analysis of the meaning of a UTS was correct and its analysis of what need be taken into account in assessing purpose in the meaning of the UTS was correct.

The appeal grounds

[104] Many of the appellants’ allegations of Authority error can be grouped into the error of law category that the Authority applied the wrong legal test or misdirected itself as to the correct legal test.

[105] The second category of allegations by the appellants focus on claims that the Authority reached a clearly untenable decision. Some of the alleged errors of law in the first category are also relevant to this aspect of the appeal.

[106] Further, the appellants say that an error of law occurred, in part, because the Authority also took into account irrelevant matters and failed to take into account relevant matters.

[107] The appellants do not challenge the Authority’s interpretation as to the status of clause (c) in relation to clauses (a) and (b). They agree with the Authority that to establish a UTS existed the Authority must be satisfied that clauses (a) and (b) are established. The respondents disagree with this interpretation.27

[108] The appellants’ challenge focuses on the Authority’s conclusions with respect to clauses (a) and (b) and whether the Authority applied the correct legal tests and also whether their conclusion was on the facts plainly wrong.

[109] Finally, the remedy of a reduction in price is challenged. The alleged error of law is said to arise from a misapprehension by the Authority of the scope of its powers. Individual appellants have identified particular claims of errors of law by the Authority including the application of wrong legal tests and considering irrelevant matters or failing to consider relevant matters in different categories.

[110] In the context of this case, where particular errors of law are placed in the analysis probably does not matter. If an error of law is made then its context in the decision making and its consequence for the decision will be relevant.28 Some legal errors, if they occur, will be fundamental and so will inevitably result in a decision being set aside, for example, a misinterpretation of the definition of a UTS and so the wrong law, pivotal to the decision, would be applied to the facts.29 Other errors may or may not matter and will likely require contextual analysis of the various appeal points to see how they relate to the ultimate decision of the Authority.

[111] When considering the appeal points I consider some discrete areas of challenge first. I then consider whether the decision is untenable. The challenge to the decision of the Authority as clearly untenable seemed to me, from the oral submissions made by the appellants and from their written submissions, to be at the heart of the appellants’ case. I then consider the challenge to the remedy imposed by the Authority and other alleged misinterpretations by the Authority of the proper

scope of its powers.

27 See [129].

29 For example see Waiotahi Contractors Ltd v Murray & Ors [1999] 3 NZLR 276 (CA).

[112] Some of the issues raised by the appellants are essentially questions of fact dressed up as questions of law. I have approached this analysis, however, by considering each appeal point raised by each of the appellants without initial concern as to whether they are questions of fact or law. If, however, an error is exposed then such exposure will require an analysis of whether the error is able to be challenged on appeal, that is, whether it is an error of law or not.

Discrete Errors of Law

Previous decisions of the Electricity Commission

[113] The appellants say that the Authority’s misinterpretation of the UTS provisions arose in part because of its failure to take notice of and interpret the current UTS provision consistently with past decisions by the Electricity Commission and other regulatory bodies.

[114] In 2004 the electricity market ceased to be self regulating. The Electricity Commission was established to regulate the market. The Commission was disestablished on 31 October 2010 and replaced by the Authority. Prior to regulation the New Zealand Electricity Market was a voluntary competitive wholesale electricity spot market. The Metering and Reconciliation Information Agreement (“MARIA”) provided for bilateral trading of electricity. The MARIA governance board and the NZEM Rules Committee oversaw the development of rules. The MARIA Conduct Committee and the New Zealand Electricity Surveillance Committee monitored and enforced compliance with the rules.

[115] Section 134(1)(g) of the EIA provides that anything done by the Electricity Commission is to be treated as having been done by the Authority. UTS decisions of the Commission are therefore deemed to be decisions of the Authority.

[116] The appellants say that the previous investigations and decisions provide a useful guide as to the circumstances that a UTS is designed to protect. Contact says that previous occasions where a UTS or its equivalent have been declared, or considered and rejected, have a common theme “in that they relate to fundamental

problems with the application of the market rules or an error in loading information underlying the market mechanism”. None arise, the appellants say, from a perception of fairness or unfairness, high prices or adverse financial impact as the Authority found here.

[117] Genesis says that there are a series of factors in this case which previous Commissions have ruled on with which the Authority has effectively wrongly rejected by its decision. The failures by the Authority contributed to its misapprehension of what in law constitutes a UTS.

[118] Following are said to be (by the appellants) the key principles arising from the previous decisions but not adhered to by the Authority. I will respond to each of these propositions in turn.

(a) more than high prices are required for a UTS. The Authority both confirmed that was the position and, contrary to Genesis’ claim, adhered to such a proposition in its analysis. At no time has the Authority ever said that “mere” high prices are sufficient alone for a UTS;

(b) the UTS regime is not an alternative recourse to the Rule “breach” provisions. It is difficult to understand the relevance of this proposition. None of the participants claimed that any Rule has been breached in this case;

(c) only an extraordinary Rule breach could constitute a UTS. Once again it is difficult to understand the relevance to this case. This is not a case involving a Rule breach and therefore whether a Rule breach is or is not required to be extraordinary before a UTS can be declared hardly arises in this case. In any event it is unhelpful to add further requirements to the definition of a UTS beyond the words actually used. And so it is unlikely to be helpful, for example, to say only extraordinary Rule breaches could ever be a UTS;

(d) the UTS provision is not an appropriate remedy where what is sought is a Rule change. It is not clear who Genesis say seeks a Rule change. But in any event, in this case, the complainants did not seek a Rule change and the Authority did not focus on Rule changes. It may or may not be the case that a change to the Rules is justified by the circumstances that arose on 26 March. But that fact by itself cannot dictate that a UTS therefore could not be declared on 26 March. Rather than be distracted by such propositions the Authority kept its eye on the definitional ball of what a UTS was. This was clearly the correct approach;

(e) for an event to be considered to threaten trading on the wholesale market the event must be such that the market is so significantly affected that daily trading is affected by withdrawal or likely withdrawal of participants or similar such circumstances. It is unwise to try and reach an exhaustive definition of what threatening trading on the wholesale market might be. It will inevitably depend on the particular facts of the particular case. This approach also favours adding further conditions to the wording of the definition of a UTS. The appellants attempt to identify the degree of threat by saying the event must be so threatening that market participants will or are likely to withdraw from trading. No such requirement is identified in the definition of a UTS;

(f) concerns about potential future manipulation do not justify a finding of a UTS. That proposition cannot be correct. A concern about potential future manipulation of the wholesale market by itself might be unlikely to justify a finding of a UTS. However, it would be relevant in assessing whether in terms of clause (a) of the definition of a UTS, there is an event which might threaten trading which would in turn be likely to preclude the maintenance of orderly trading. Subclause (a) is concerned, in part, with future events. And so the potential to manipulate a market is likely to be relevant in the assessment of whether or not the event which gave rise to the

potential might preclude the maintenance of orderly trading. In any event the Authority expressly found there was no attempt to manipulate the market and so in this case it was not concerned about future market manipulation;

(g) the Authority and its predecessors consistently declined to impose a price cap. It is legitimate to prize consistency highly in this area. The market should be reassured that similar situations are likely to give similar results should there be complaints to the Authority. However, I consider the Authority itself is not bound by previous decisions of

the Authority and the Commission.30 I agree with Meridian

submissions that past decisions do not have a precedential effect as understood in law. The application of the UTS provisions are inherently fact dependent. The Authority, in any event, is free to disagree with, or take a different view of its own or the Commission’s past decisions. More importantly none of the factual situations identified by the appellants are anything like the factual circumstances of 26 March and so it cannot credibly be maintained that the Authority has acted in a way which is inconsistent with previous decisions of the Authority/Commission.

Failure to identify a contingency or event

[119] The first error of law in relation to clause (a) alleged is that the Authority failed to identify the contingency or event which it alleged gave rise to the UTS. The definition of a UTS31 is a “contingency or event” that has the ingredients of clauses (a) and (b) present. Contact submits that because contingency and event are expressed in the singular the Authority’s function was to first identify a contingency or an event. That is, a single circumstance. I reject this submission. I am satisfied

that both words can include a combination of factors and typically will do so. I note

s 33 of the Interpretation Act 1999 provides that the singular includes the plural.

30 Telecom NZ v Commerce Commission HC Wellington CIV-2004-485-2118, 6 October 2005.

31 At [63].

[120] The appellants say the Authority failed to identify the actual event which gave rise to the UTS. It submits that the judgment of the Authority is unclear as to whether the event was the high prices of 26 March, the alleged “squeeze” or a combination of events that occurred on that day. Genesis says this failure to define the “event” as the first part of the definition goes to the jurisdiction of the Authority to find a UTS.

[121] This seems to me a circular argument and in any event of no real moment in this case. The Authority made it clear the event being talked about in this case was the variety of circumstances that led to the high prices on 26 March. As Meridian identified, the circumstances that gave rise to the event are identified in summary at [159]32 of the Authority’s decision.

[122] The events identified are: the fact that Genesis was in a net pivotal position during the relevant period on 26 March (this arose from a combination of circumstances including the transmission line outage and the withdrawal of electricity from the market (at Otahuhu)); that the high prices then offered by Genesis had not previously been offered when a generator was net pivotal; that the high prices were not able to be foreseen by industry participants, at least not in time to realistically reduce demand or hedge; finally, the prices were not related to an underlying supply and demand imbalance but a temporary situation, and as a result they had no relationship to the cost of supply of electricity.

[123] While the appellants challenge a number of these conclusions there can be no doubt that the Authority did identify a set of circumstances which it concluded gave rise to a UTS, namely the event or events proposed. I reject this ground of appeal.

Wrong standard of proof

[124] The second ground of appeal relates to the allegation that the Authority applied the wrong standard of proof to elements of the definition in clauses (a) and

32 At [76].

(c)(v). Subclause (a) is concerned with threats to trading on the wholesale market

that (as relevant) “would be likely” to preclude the maintenance of orderly trading.

[125] Subclause (c)(v) is a potential example of a UTS and is concerned with an exceptional or an unforeseen circumstance which “may” threaten accepted principles of trading for the public interest.

[126] Before I directly deal with the standard of proof in clauses (a) and (c) of the definition, this appeal point inevitably raises the proper interpretation of the definition of a UTS and in particular the relationship between clauses (a) and (b) in relation to clause (c).

[127] The appellants (in contrast with Meridian and other respondents) agree with the Authority’s conclusion regarding the definition of a UTS when it said it concluded that clause (c) may be illustrative of a UTS, but before a UTS can be said to have occurred, clauses (a) and (b) must be established.33

[128] The respondent submitted that clauses (a) and (c) each independently described a contingency or event which, if established, is a UTS. The requirements of clause (b) are, the respondents said, relevant only where the circumstances in clause (a) are found to exist, clauses (a) and (b) are therefore cumulative. Each circumstance described in clause (c) is, the respondents say, if established, a UTS. The respondents point to previous definitions of a UTS in the New Zealand Electricity Rule Book and Electricity Governance Regulations (r 2.36) and regulation 55 of the Electricity Governance Regulations as supporting this interpretation.

[129] The Authority said:

[18] While paragraph (c) above suggests the types of situations in which a UTS may be considered to have occurred, it is not necessary that the contingency or event falls into one of the categories listed in paragraph (c).

33 Electricity Authority Decision at [15], [18]–[19].

[19] Equally, a situation of the type listed in paragraph (c) will not automatically meet the requirements of the definition of a UTS. It is possible that such a situation could fall short of the thresholds in paragraphs (a) and (b) of the definition, and therefore not constitute a UTS.

[130] I also agree with the Authority’s interpretation of the inter-relationship between clauses (a), (b) and (c). The definition of a UTS is not without its difficulties. However, I consider the only interpretation of the definition that makes sense requires those events described in clause (c) to also have the elements of clauses (a) and (b) established before a UTS can be declared.