|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

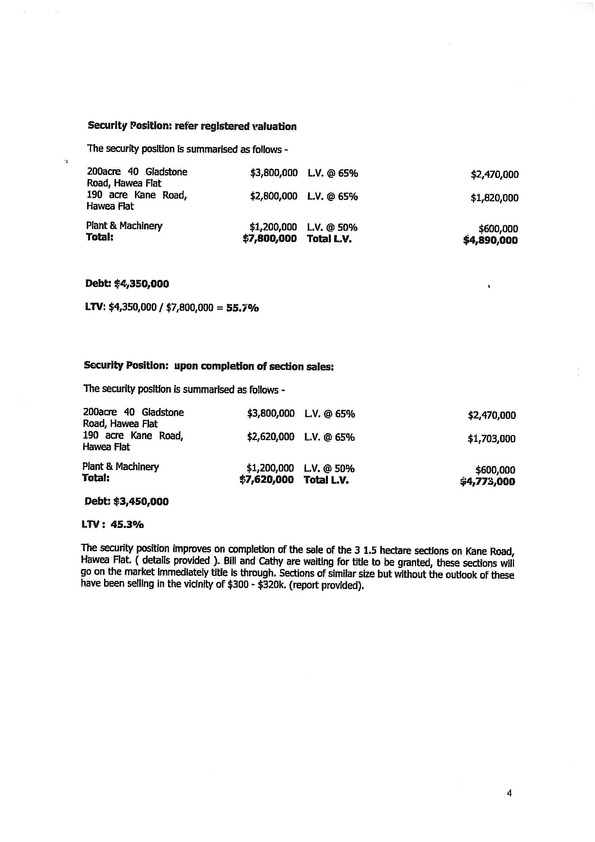

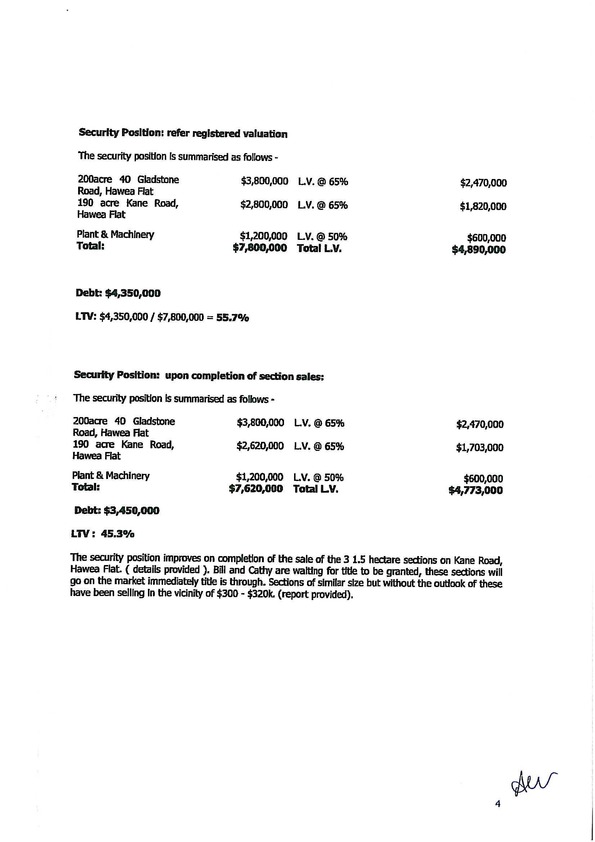

| Search

| Feedback

High Court of New Zealand Decisions |

Last Updated: 13 November 2012

IN THE HIGH COURT OF NEW ZEALAND DUNEDIN REGISTRY

CIV-2012-412-000401 [2012] NZHC 2614

BETWEEN SOUTHLAND BUILDING SOCIETY Plaintiff

AND CATHERINE ISOBEL ALLISON First Defendant

AND WILLIAM ARTHUR ALLISON Second Defendant

Hearing: 9 October 2012

with additional written submissions 12 and 17 October 2012 (Heard at Dunedin)

Appearances: O G Paulsen for Plaintiff

D More for Defendants

Judgment: 5 November 2012

JUDGMENT OF ASSOCIATE JUDGE OSBORNE [as to striking out of defence]

The plaintiff ’s strike out application

[1] The plaintiff applies for orders striking out the defendants’ statement of

defence and counterclaim and entering judgment for the plaintiff.

The factual background

[2] The material background as identified in the pleadings (through the defendants’ admissions of allegations in the statement of claim) and through additional matters of undisputed background which are before the Court by way of

affidavit follows.

SOUTHLAND BUILDING SOCIETY V ALLISON HC DUN CIV-2012-412-000401 [5 November 2012]

[3] The Allison family farm was at Hawea Flat, Central Otago. Mr Allison worked as a self-employed farmer since 1979. Mr and Mrs Allison bought the homeblock from Mr Allison’s parents in the early 1980’s and had increased the size of the farm to some 1165 acres (390 owned and 775 leased).

[4] In 2008 the Allisons were looking for a new bank. The manager of the Cromwell branch of the plaintiff (“SBS”), Grant Williams, who styled himself “Agribusiness Solutions”, prepared an “Agribusiness Loan Report” for submission to SBS’s lending committee. A first version was dated 28 November 2007. The Allisons were then looking for funding of $4,350,000. They referred to plans for subdivisions of 1.5 ha blocks. They referred to valuation reports of the subdivided blocks. The SBS lending committee rejected this first application. A second (very similar) version of the report, also prepared by SBS’s Grant Williams, was dated 14

February 2008. The funding request was reduced to $4,150,000. The reports are appended to this judgment as Appendix 1 and Appendix 2.

[5] SBS on the second application agreed to provide funds. SBS made loans to AT Company Limited, a company owned by the Allisons as trustees of their family trust. Two loans were made in May 2008 and a further loan two months later. A final loan was made in September 2009 but this was obtained mainly to clear arrears which had accrued on the first loan. Altogether $3,520,000 principal was involved. Mortgage security had been taken.

[6] Mr and Mrs Allison, as trustees of the family trust, also entered into guarantees of the loan repayment. Before doing so they received advice on their obligations from a solicitor, Kerry Richard Ayers, who certified to SBS the fact of his advice and the Allisons’ indication that they fully understood their liability. The guarantee made the Allisons liable as the principal debtors.

[7] In 2011 the Allisons defaulted on repayment. SBS realised its mortgage securities leaving a shortfall of over $2,000,000. AT Company Limited is now in receivership. SBS in this proceeding sues the defendants pursuant to their guarantees.

[8] The Allisons filed a statement of defence and counterclaim.

[9] They admit the pleaded details of loan contracts, guarantees and defaults, but deny that they are liable to repay any sum. They say that they are excused from payment because:

The relationship between the plaintiff and the defendants was of sufficient proximity that it was fair just and reasonable that the plaintiffs owed the defendants a duty of care to ensure that the loans advanced by the plaintiff to ATC were loans that a prudent banker would make.

and:

The loans from the plaintiff to ATC pursuant to the agreements dated 19 May

2008 and 19 July 2008 were not loans that a prudent banker would make.

[10] They particularise the allegations of imprudent lending on the part of SBS by asserting that SBS’s lending had been based on unduly optimistic and unsustainable forecasts. They continue:

The decision by the plaintiff to agree to further lending pursuant to the loan agreement dated 29 September 2009 was reckless.

Particulars

(a) The debt history of ATC increased from $4.173m in the 2007/2008 year, to $4.658m in the 2008/2009 year, and $5.244m in the

2009/2010 year.

(b) It should have been apparent to the plaintiff in June 2009, after a loss of $275,000 that the ATC account was of concern and a prudent banker would not have agreed to further lending.

The decision of the plaintiff to make the loan advances to ATC in May 2008

was in breach of the plaintiff’s duty of care to the defendants.

The further decision by the plaintiff to increase its lending to ATC in September 2009 was in breach of the plaintiff’s duty of care to the defendants.

As the result of the breaches of the plaintiff’s duty of care to the defendants, the defendants are not liable to the plaintiff in terms of the deed of guarantee or at all.

[11] By way of counterclaim, the Allisons pleaded a total loss of shareholder funds to a value, at May 2008, of $3,000,000.

A draft amended statement of defence

[12] The defendants’ current pleading was directed to a duty of care to ensure that SBS’s lending to AT Company Limited was prudent. For reasons I will return to, that formulation of a duty of care is unsustainable.

[13] In the course of Mr More’s submissions, it became apparent that he was placing greater emphasis on a related but arguably different formulation of a duty of care. This relates to the role of SBS’s Cromwell manager, Mr Williams. Mr Shiels, pursuant to leave reserved, has provided a draft amended statement of defence. The draft formulates a duty of care in these terms:

In assuming responsibility for completing ATC’s proposal for finance, the plaintiff was under a duty of care to the defendants, whom the plaintiff knew would be guarantors of any loans made to ATC. The duty of care was to use the professional skill and judgment in preparing the Agribusiness loan reports that a prudent financial advisor would use.

[14] The alternative formulations of a duty of care were the subject of both oral submission and, pursuant to leave reserved, written submissions after the hearing.

[15] I will, out of deference to the helpful submissions received from counsel in relation to duty of care, return to this discussion below.

[16] Before doing so, however, I will refer to the principles which I adopt in relation to this strike out application. I will then examine provisions of the loan guarantee contracts which govern the parties’ relationship. In particular, I will examine a clause which precludes the raising of set-off or counterclaim.

[17] High Court Rule 15.1 makes provision for orders striking out all or part of a pleading. In this case the defendants/applicants invoke r 15.1(1)(a) (No reasonably arguable cause of action) and r 15.1(1)(d) (Abuse of the process of the court).

[18] I adopt the following as principles applicable to the consideration of this application:

(a) The Court is to assume that the facts pleaded are true (unless they are entirely speculative and without foundation).

(b) The cause of action must be clearly untenable in the sense that the

Court can be certain that it cannot succeed.

(c) The jurisdiction is to be exercised sparingly and only in clear cases.

(d) The jurisdiction is not excluded by the need to decide difficult questions of law, even if requiring extensive argument.

(e) The Court should be slow to rule on novel categories of duty of care at the strike out stage. (See Attorney-General v Prince [1998] 1

NZLR 262 (CA)).

The contractual provision excluding set-off or counterclaim as a defence

[19] The Allisons are sued on a deed of guarantee which they executed in support of the loans which SBS made to AT Company Limited. They guaranteed the payment of all indebtedness of AT Company Limited to SBS in the event of AT Company Limited’s default.

[20] It is common ground that AT Company Limited defaulted. No dispute arises

as to SBS’s quantification of its claim.

[21] Both Mr and Mrs Allison were defined as “guarantor” and by the deed they

agreed that:

The Guarantor shall make payment to SBS without any deduction, withholdings, set-off or counterclaim of any kind.

[22] On any view of the current statement of defence and of the draft amended statement of defence, the Allisons seek in this case to set up a set-off or counterclaim, or both. The current statement of defence expressly refers to the concept of counterclaim. The draft amended statement of defence no longer includes a pleaded counterclaim but implicitly asserts either a set-off or counterclaim, inasmuch as the Allisons identify the damage they have sustained through an alleged breach of duty of care. They plead that they “would be called on to honour their guarantee.” In other words, they implicitly assert that the damage sustained from the breach of duty of care is the sum claimed pursuant to the guarantee.

The nature of the no set-off clause

[23] Provisions such as that in the present deed of guarantee can be described as traditional no set-off clauses designed to deal with the principles recognised by the Court of Appeal in Grant v NZMC Ltd.1 It is accordingly a genuine defence to a claim. On the other hand, a counterclaim is a cross action which, in some circumstances, may have no connection at all with the subject matter of the claim2 although the rules of Court may permit a counterclaim to be taken into account by the Court in response to another party’s asserted claim. A counterclaim is not of itself a defence to the claim.

[24] It is settled that comprehensive “no set-off” clauses are effective to preclude

the claiming of a set-off as a defence. A fortiori, a clause which excludes the claiming of a counterclaim in response to a requirement of payment will be effective.

1 Grant v NZMC Ltd [1989] 1 NZLR 8 (CA); see the similar characterisation in Browns Real Estate Ltd v Grand Lakes Properties Ltd HC Invercargill CIV-2009-425-670, 10 March 2010, affirmed on appeal Browns Real Estate Ltd v Grand Lakes Properties Ltd [2010] NZCA 425; (2010) 20 PRNZ 141 (CA) at [14].

2 Ibid.

[25] A party who has contractually agreed to a clause which precludes set-off or counterclaim is in breach of his or her contract to repay a loan without deduction. The Court does not tolerate such breach of contract.3

[26] The effect of the distinction between set-off and counterclaim is well understood. As Somers J, delivering the judgment of the Court in Grant v NZMC Ltd4 observed, a set-off when established by judgment will pro tanto extinguish the plaintiff’s claim. There is no other provision in the contracts between the parties to vary or limit the otherwise clear provision of the present deed. Mr More was equally unable to point to any other factor outside the four corners of the contractual

documents which would in some way cut across the provision.

[27] The provision is accordingly determinative of the parties’ rights in this proceeding. SBS, on the one hand, is entitled to judgment for the outstanding payments under the loans. The Allisons, on the other hand, are not entitled to assert their cross claims, whether by way of set-off or counterclaim, as a justification for non-payment of the loans. The parties have by contract created a “pay now, argue later” regime and the Allisons must honour that. That involves not asserting by way of a statement of defence their set-off or counterclaim. The plaintiff is entitled to the striking out of the entire defence, the purpose of which was to set up the set-off or counterclaim.

Submissions as to an underlying duty of care

[28] The contractual provision between the parties is the complete answer to this application.

[29] Counsel also addressed detailed submissions to the question of a duty of care as formulated for the defendants, both under the current statement of defence and the draft statement of defence. In deference to the detail and quality of those

submissions, I will somewhat briefly refer to the issues as to a duty of care.

3 Browns Real Estate Ltd v Grand Lakes Properties Ltd [2010] NZCA 425; [2010] 20 PRNZ 141 (CA) at [14];

Bromley Industries Ltd v Martin & Judith Fitzsimons Ltd [2009] NZCA 382 at [51].

4 Grant v NZMC Ltd, above n1, at 11.

Current statement of defence – a duty of care on a bank to proffer advice on the prudence of a loan?

[30] It is established that a banker generally is under no duty of care to proffer advice to a customer or guarantor on the prudence of a loan or the wisdom of the customer’s commercial project.

A duty of care owed by a bank to guarantors to ensure its loans were prudent?

[31] The defence and counterclaim are based on a duty of care within the law of negligence. The duty is formulated (above paragraph [9]) on the basis that SBS owed the defendants a duty of care to ensure that loans advanced to their company were loans that a prudent banker would make.

[32] We are here concerned with the law governing the relationship between lender (or creditor) and guarantor.

[33] It is equity which will intervene to protect a guarantor.5

[34] The case law (to 1996) was accurately referred to and summarised in the

Laws of New Zealand commentary thus:6

The guarantor will be released by any bad faith on the part of the creditor towards the guarantor. The same will apply if the creditor conspires towards the default of the principal debtor. However, merely irregular conduct on the part of the creditor will not discharge the guarantor.

(footnotes omitted)

[35] This formulation derives from the judgment of Bingham J, as affirmed on appeal by the Court of Appeal (and especially through the judgment of Robert Goff LJ).7 In New Zealand, the Court of Appeal in Coffey v DFC Financial Services Ltd8

cited the formulation with approval, as did the same Court in Westpac Securities Ltd

5 Laws of New Zealand Guarantees and Indemnities (online ed) at [204].

6 Ibid.

8 Coffey v DFC Financial Services Ltd (1991) 5 NZCLC 67,403 (CA) at 67,411.

v Dickie.9 The equitable nature of the guarantor’s rights then leads to the following

discussion in the Laws of New Zealand10 commentary:

The existence of these equitable rights is inconsistent with the existence of a general duty of care by the creditor toward the guarantor, actionable in negligence, and the Courts have declined to impose such a general duty. The equitable principles, however, only supplement and do not supplant the guarantor’s contractual rights. For example, a guarantor will be entitled to cancel the contract where the creditor commits a repudiatory breach. Discharge will also follow the failure of any condition precedent to the guarantor’s liability. As with any contract, a guarantor may claim damages for any breach of the express or implied terms of the guarantee.

(footnotes omitted)

[36] The authorities cited for the formulation in the first sentence of the above quotation are Downsview Nominees Ltd v First City Corporation Ltd11 and China and South Sea Bank Ltd v Tan.12 In Downsview, Lord Templeman, delivering the judgment of the Privy Council, held:13

The general duty of care said to be owed by a mortgagee to subsequent encumbrancers and the mortgagor in negligence is inconsistent with the right of the mortgagee and the duties which the Courts applying equitable principles have imposed on the mortgagee... The duties imposed by equity on a mortgagee and on a receiver and manager would be quite unnecessary if there existed a general duty in negligence to take reasonable care in the exercise of powers and to take reasonable care in dealing with the assets of the mortgagor company.

[37] In China and South Sea Bank Ltd v Tan,14 the Privy Council was called on to deal with a case in which guarantors had contended for a duty in the tort of negligence. The Court, at first instance (through one Master Hansen), had given judgment in favour of the creditor, a decision upheld by the Hong Kong Supreme Court but reversed by the Court of Appeal of Hong Kong. The Privy Council (through a judgment delivered by Lord Templeman) dealt with the Court of Appeal’s

decision in one sentence:15

9 Westpac Securities Ltd v Dickie [1991] 1 NZLR 657(CA) at 663-664.

10 Laws of New Zealand Guarantees and Indemnities (online ed) at [205].

12 China and South Sea Bank Ltd v Tan [1990] 1 AC 536; [1989] 3 All ER 839 (PC).

13 Downsview Nominees Ltd v First City Corporation Ltd, above n 11, at 524.

14 China and South Sea Bank Ltd v Tan [1990], above n 12.

15 China and South Sea Bank Ltd v Tan, above n 12, at 841.

The Court of Appeal sought to find such a duty in the tort of negligence but the tort of negligence has not yet subsumed all torts and does not supplant the principles of equity or contradict contractual promises or complement the remedy of judicial review or supplement statutory rights.

[38] The Privy Council’s decision in China and South Sea Bank Ltd v Tan reflects the domestic law of New Zealand. Hardie Boys J, delivering the judgment of the Court of Appeal in Westpac Securities Ltd v Dickie said:16

There is no basis for suggesting bad faith in this case, nor for suggesting connivance at the default, which of course was in the failure to repay, not in the receipt of the funds two years earlier. The defence could succeed in this case only if there are grounds for avoiding a guarantee other than those so clearly stated in the cases. Whether there be any such grounds, it is clear from the China and South Sea Bank case that negligence towards the guarantor is not one. Still less can a failure by the creditor to be prudent for its own sake. And that in the end is all that has been able to be alleged against this creditor.

[39] The same observation applies in this case to the current defence in the current statement of defence. The document essentially pleads negligence and a breach of a duty of care. There is an unparticularised reference to recklessness which must be read in conjunction with the other specific allegations of negligence. They do not suggest bad faith.

[40] Mr More’s brief written synopsis filed for the hearing suggested a possible expansion of the law of negligence into the relationship between creditor and guarantor. He referred to the judgment of the Supreme Court in North Shore City Council v The Attorney-General.17 He identified the three-stage approach set out in that judgment for considering the imposition of a duty of care. The first stages (loss as a reasonably foreseeable consequence of the creditor’s acts and sufficient proximity between lender and guarantor) are taken to exist as pleaded in the statement of claim. Mr More suggested that the third consideration (whether it

would be fair, just and reasonable to impose the duty) was met by the plaintiff’s

involvement in the loan application and the general circumstances of the Allisons’

need for a switch of bankers.

16 Westpac Securities Ltd v Dickie [1991] 1 NZLR 657 (CA) at 665.

17 North Shore City Council v Attorney-General [2012] NZSC 49.

[41] To the extent that the current statement of defence makes assertions as to a duty of care in the relationship between lender and guarantor, it does not raise novel issues of law. Quite the opposite, it is informed by well-established equitable principles which, on the highest authority, leave no room for the imposition of a tortious duty of care. Guarantees repeatedly oil the wheels of commercial lending. It is of fundamental importance that the law and duties concerning them are settled and that duties from other areas of law are not imported so as to conflict with the established equitable principles. Anything short of bad faith, connivance or the like does not affect the conscience (or other legal responsibility) of the lender.

[42] In these circumstances, even had the parties not included a “no set-off” provision in the deed of guarantee, I would have found that the defendants’ current pleading of a duty of care did not amount to a sustainable defence to the plaintiff’s claim.

The amended defence – a duty of care (of a prudent financial advisor) in the preparation of the Agribusiness Loan Reports?

[43] In the draft amended defence, Mr More would move the focus of his analysis of the duty of care away from the act of the bank in making an allegedly imprudent loan (with AT Company Limited thereby receiving, and the Allisons thereby guaranteeing, an imprudent loan). He would move the focus to such professional duties as SBS through its “Agribusiness Solutions” person, Grant Williams, owed to the Allisons (and AT Company Limited) when assisting them with the formulation of a loan application.

The factual background

[44] Given that this is a strike out application, the defendants’ pleaded allegations of fact are taken to be correct. The allegation that SBS assumed a responsibility is taken to be correct and is pleaded in this way:

The plaintiff, by its Cromwell manager, encouraged ATC in its application. The plaintiff assumed responsibility for completing ATC’s proposal for finance, and submitted the proposal to the plaintiff’s lending committee.

The proposal was contained in a document described as “Agribusiness Loan

Report”.

[45] The defendants put their allegations of breach of duty of care in four particulars:

(a) The second Agribusiness loan report understated the liabilities of ATC by $200,000. This made the position of ATC appear better than it was.

(b) The plaintiff’s lending was not supported by a viable farming business

in 2008. ATC incurred trading losses from 2006 to 2008.

(c) The budget prepared was too optimistic going forward. The income was over assessed; the interest and rental costs were under assessed; and likely surpluses were over assessed.

(d) On the information provided to the plaintiff by ATC, a prudent financial advisor would have advised ATC against proceeding with its loan application to the plaintiff, and would not have recommended the proposal to the plaintiff.

[46] In relation to the strike out application in this case, the Court has the added benefit of knowing exactly what the “Agribusiness Solutions” reports say, as they have been put in evidence (Appendices 1 and 2 hereto).

[47] I identify salient, at least arguable, aspects of the reports:

(a) Each report is a proposal – the first report is expressly a proposal (to

SBS) for funding of $4,350,000 (reduced in the second report to

$4,150,000);

(b) The report is as to (balance sheet) financial position – pages 3 to 4; (c) The report is as to a budget – page 5 – Mr Williams stating:

In conjunction with the Allisons, we have constructed a budget/cashflow for the coming year ... and a medium term budget ...

(emphasis added)

(d) The report is advocacy – page 6 – with Mr Williams under “General Comments” speaking to the strength of the Allisons and referring to “an excellent opportunity [for SBS] to secure a large scale cropping operation in the Upper Clutha region”.

The law

[48] I have referred to the settled law whereby a banker who chooses not to give advice to a customer or guarantor on the prudence of a loan owes no duty of care to that customer in relation to the wisdom of the customer’s commercial project.

[49] At the hearing of oral submissions, Mr Paulsen had to respond to legal argument around the duty of care as it developed in the course of argument in a direction significantly different to the initially pleaded defence. Following an adjournment in the course of the hearing, Mr Paulsen was able to refer me to a passage in Tyree’s Banking Law in New Zealand18 and to a decision of the United

Kingdom Court of Appeal in Lloyd’s Bank plc v Cobb.19 Mr Paulsen invited me to

accept as applicable a passage from the judgment of Scott LJ in Lloyd’s Bank plc v

Cobb which reads:20

In my judgment, the ordinary relationship of bankers and customers does not place on the bank any contractual or tortious duty to advise the customers on the wisdom of commercial projects for the purpose of which the bank has been asked to lend money. If the bank is to be placed under such a duty, there must be a request from the customer, accepted by the bank, or some arrangement between the customer and the bank, under which the advice is to be given.

19 Lloyd’s Bank plc v Cobb (UK Court of Appeal, 18 December 1991).

[50] Given that I have found that the defendant’s defence is to be struck out for other reasons, it is unnecessary that I determine whether the authorities relied upon by Mr Paulsen are directly applicable so as to negate the duty of care alleged in the defendant’s reframed draft defence. Given the possibility that the defendants may choose to pursue an independent claim in that regard, and that such a claim might ultimately fall to be determined at a trial after all the facts are determined, I will refrain from any detailed consideration of answers which the defendants may have to Mr Paulsen’s assertion that no duty of care can exist.

[51] It is sufficient to observe briefly for the following reasons that the correct outcome, on the facts of this case, may not be as black and white as a simple quotation from cases such as Lloyd’s Bank plc v Cobb might suggest.

[52] Mr Paulsen obtained his reference to Lloyd’s Bank plc v Cobb from Tyree’s Banking Law in New Zealand. The introductory paragraph to that chapter (4.8) reads:21

The business of modern banking has increasingly drawn bankers into the provision of business advice to their customers. Indeed, many national banks advertise such services as a basis to attract customers. Some of the more recent banking products, such as foreign exchange loans, have also given banks the incentive to offer more general advice about the propriety of the products and their usefulness to the customer. The broadening of the role of bankers as business advisers has also broadened the potential for adverse claims against them. In this section, we consider the liability of bankers who are negligent when providing financial advice to customers.

It is now clear that a banker owes the customer a duty of care when giving financial advice according to the normal Hedley Byrne principles governing negligent misstatement. Where a banker chooses to give such advice, even gratuitously, it seems inevitable that the banker will have assumed responsibility for the consequences that flow from reliance on his or her words.

(footnotes omitted)

[53] The authors of Tyree go on to note the important distinction between two situations, the first being where the banker chooses to give advice about (for instance) the merit of the client’s proposed business venture, and the second being

where the bank has not chosen to give advice.

21 Tyree’s Banking Law in New Zealand, above n 18, at 131.

[54] The editorial note to the report of Lloyd’s Bank plc v Cobb similarly identifies the importance of the facts of each case to a determination of whether a bank has assumed a responsibility of care through giving advice. The editorial note states:22

... as the Court of Appeal held in Morgan v Lloyd’s Bank plc [1998 Lloyd’s Bank Rep 73], an antecedent request for advice from the bank’s customer is not a prerequisite for the existence of a duty of care; it is enough if the bank provides advice in the course of its banking business. The scope of the bank’s business is a question of fact in each case. If, for example, the bank’s promotional literature and advertising suggest that the bank holds itself out as capable of advising on all financial matters, it will owe a duty of care to any customer to whom it gives such advice. If that advice is negligent and the customer relies on it to his detriment, the bank will be liable.

(footnotes omitted)

[55] These references and cases illustrate the fact-dependent nature of each case. A banker who stays within the “traditional” confines of a banker/customer relationship will avoid the imposition of a duty of care. On the other hand, a bank which takes it upon itself to proffer assistance or advice in relation to financial structuring may be found to have stepped outside that traditional boundary and to have exposed itself to the imposition of a duty of care.

[56] Particularly in a strike out situation, where the defendants’ pleaded facts are to be taken to be correct, it is unlikely that I would have struck out the defendants’ draft statement of defence if the only ground for striking out were this aspect of the plaintiff’s application.

Conclusion

[57] The plaintiff’s application to strike out the defence is successful. The plaintiff’s factual allegations as to the making of the loans and the guaranteed

liability are admitted. The plaintiff is entitled to judgment.

22 Lloyd’s Bank plc v Cobb (1991) 12 Legal Decisions Affecting Bankers 210 at 215.

Orders

[58] I order:

(a) To the extent that the Statement of Defence and Counterclaim of the defendants asserts a set-off or counterclaim (as pleaded in paragraphs

27-38 of the pleading) the statement of defence and counterclaim is struck out.

(b) There is judgment for the plaintiff in the sum of $2,091,096.47;

(c) There is judgment for the plaintiff for interest in the sum of

$73,331.59.

(d) The defendants are to pay the costs and disbursements of the plaintiff in this proceeding on a reasonable solicitor/client basis. The quantum of such costs is reserved for agreement between the parties, failing which counsel are to file sequential memoranda limited to four pages together with any exhibits.

Associate Judge Osborne

Solicitors:

Cavell Leitch Pringle & Boyle, PO Box 799, Christchurch

Scholefield Cockcroft Lloyd , PO Box 71, Alexandra 9340

Counsel: D J More, PO Box 5143, Dunedin

APPENDIX 1

Viability: Status Quo

Debt Servicing Income

Term Debt $3,15m $300,000 Single Gross $120,000 Source Lucerne

@ 9.5%

Overdraft $300k $17,000 Single Gross $20,000 Source Oats

Rent $80,9% Single Gross $720,000 Source Barley

Single Gross $300,000 Source Dairy Grazing

Single Gross $200,000 Source Contracting

Total $397,996

Income RatIo 29% Total $1,360,000

Surplus $134,762

2007-2008 Season

pebt Servicing Income

Term Debt $4,OSm $384,750 Single Gross $120,000 Source Lucerne

Oveniraft $300k $17,000 Single Gross $20,000 Source Oats

Rent $80,996 Single Gross $830,000 Source Barley

HP 58,000 Single Gross $300,000 Source Dairy Grazing

Single Gross $200,000 Source Contracting

Total $540,746

Income RatIo 36.7% Total $1,470,000

Surplus $101,262

This operation has been going though a development stage in terms of the new block purchased last

year. There has been a considerable amount of capital go Into capital fertillser and refencing of the

190 acre Kane Road block.

In conjunction with the Allisons, we have constructed a budgetj cashflow for the coming year which runs from December07 until November08 and a medium tern budget which shows the operation once the overall debt has been reduced by $900k,

In tire 2007108 season, The major Income in terms & crop comes from barley. There will be 283 hectares ( 700 aires) sown In Barley this season. They are producing 3 tonnes to the acre of barley.

They sell their barley to International Malt In Ashburton and have a contract for the season for up to

2000 tonnes at $385 per tonne. Copy of coniiact on file. The indicators have suggested that the barley price will be higher but Bill was keen to have some assurances as they have a large volume of barley to sell.

They will sell a large volume of Lucerne this season as they have the abIlity to irrigate In critical times.

This allows them to take 4 cuts of lucerne from each paddock. We have budgeted on $60 per bale. This is conservative as Lucerne has been making $80 per bale (bales are 15 small bale equivalents).

The Dairy grazing will generate $300k. Next winter, they hope to graze 1500 cows for ten weeks at

week

UllI aiji ii $200k

S

APPENDIX 2

NZLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.nzlii.org/nz/cases/NZHC/2012/2614.html