|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

High Court of New Zealand Decisions |

Last Updated: 29 October 2012

IN THE HIGH COURT OF NEW ZEALAND NAPIER REGISTRY

CIV-2012-441-000550 [2012] NZHC 2766

BETWEEN NAVILLUSO HOLDINGS LIMITED Applicant

AND ANTHONY JOHN DAVIDSON JOHN LAURENCE ARMSTRONG STUART GORDON KINNEAR AS TRUSTEES OF THE CAROLINE TRUST NO 2

Respondents

Hearing: 21 September 2012 (Heard at Napier)

Appearances: M E J Macfarlane for Applicant

M B Lawson for Respondent

Judgment: 23 October 2012

JUDGMENT OF ASSOCIATE JUDGE OSBORNE [as to caveat lapsing]

Introduction

[1] The applicant seeks an order that a caveat not lapse.

[2] In its caveat, lodged on 11 February 2011, the applicant claimed an estate or interest:

Pursuant to an agreement signed by the Registered Proprietor ... dated on or about 10 January 2011, the Registered Proprietor irrevocably and unconditionally covenanted to register an encumbrance in favour of the Caveator being Navilluso Holdings Limited over the Registered Proprietor’s land contained in certificate of title 323998.

[3] The key issue between the parties has been whether a contract between them gave rise to a registrable interest. The issue is legal, not factual. There is no

significant dispute of fact.

NAVILLUSO HOLDINGS LIMITED V DAVIDSON HC NAP CIV-2012-441-000550 [23 October 2012]

The facts

[4] The respondents (“the trustees”) are trustees of a trust associated with the

Kinnear family.

[5] The trustees own a property in Hastings whose title has been caveated by the applicant, Navilluso.

[6] The Kinnear interests control a company, Fernwood NZ Ltd, which operates its business on the property, making wooden bins and other products.

[7] Navilluso controls another company, Tumu Timbers Ltd. Tumu, from premises in Hastings, manufactures bins particularly for the pip fruit industry.

[8] The agreement referred to in the caveat is a written agreement dated 10

January 2011 which was entered into by:

![]() Tumu;

Tumu;

![]() Fernwood;

Fernwood;

![]() The trustees; and

The trustees; and

![]() Richard and Stuart Kinnear (members of the Kinnear

family), as covenantors.

Richard and Stuart Kinnear (members of the Kinnear

family), as covenantors.

The terms of the agreement

[9] Under the agreement, Tumu was the “Customer”; Fernwood the “Supplier”;

and the trustees described as the “Trust”.

[10] Clause 10 of the agreement provides:

Lease of capacity and covenants

10.1 Lease of capacity: In consideration of the Trust procuring the Supplier to enter into this Agreement in order to provide the Customer with additional capacity for the operation of the Customer’s business the

Customer agrees to pay to the Trust a rental payment of $10,000.00 plus GST per month for the Initial Term. The first such payment will be made on the Commencement Date and all subsequent payments will be made on the monthly anniversary of the Commencement Date. For the avoidance of doubt it is acknowledged that the maximum amount payable by the Customer under this provision is $460,000.00 being $10,000.00 per month for the 46 months of the Initial term.

10.2 Trust covenants: The Trust irrevocably and unconditionally covenants to register against the certificate of title to the Site an encumbrance pursuant to which the registered proprietor of the Site from time to time agrees, in favour of Navilluso Holdings Limited and its Associated Persons, that the registered proprietor shall not permit any of the following activities to be conducted on or from the Site without the prior written approval of Navilluso Holdings Limited:

(a) nailing for the assembly of pallets or Bins; and

(b) the supply of components to other manufacturers who have a place of business within the boundaries of the Hawkes Bay.

The parties acknowledge that the encumbrance is intended to bind the registered proprietor of the Site from time to time in perpetuity.

10.3 Supplier and Covenantor covenants: In consideration of the Customer agreeing to enter into this Agreement for their benefit (which is acknowledged) the Supplier and Covenantors jointly and severally covenant that they shall not at any time during the term of this Agreement and for a period of two years after expiry of this Agreement be directly or indirectly involved in the assembly of pallets or Bins or the supply of components or pallets or Bins to other manufacturers who have a place of business within the boundaries of the province of Hawkes Bay unless agreed in writing by Navilluso Holdings Limited. This restriction shall apply to any Associated Person of either of the Covenantors.

The facts – continued

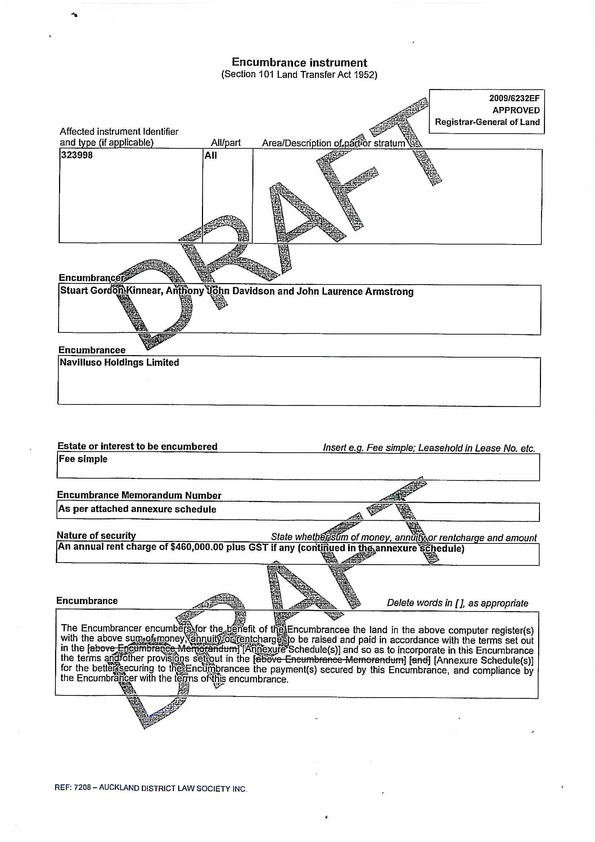

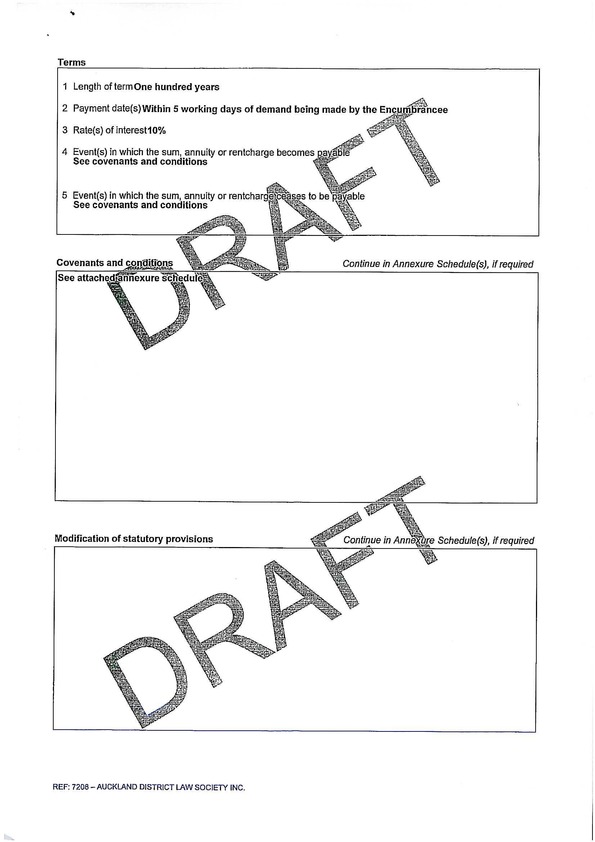

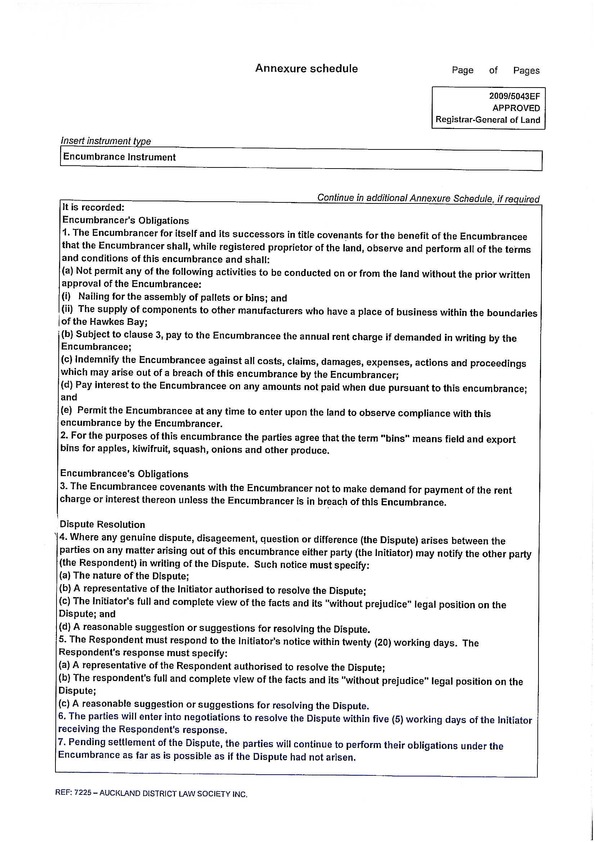

[11] From the day after execution of the contract (11 January 2011) Navilluso’s solicitors sought to obtain the trustees’ execution of an encumbrance instrument. The draft instrument was expressly stated to be pursuant to s 101 Land Transfer Act

1952 and adopted the form (2009/6232EF) approved by the Registrar-General of Land. The form which Navilluso wanted executed is that attached to this judgment as Appendix A.

[12] In the meantime, issues also arose over manufacturing rights under the agreement.

[13] In May 2012 Tumu and Navilluso invoked dispute procedures under the agreement. They referred the trustees’ failure to register an encumbrance in favour of Navilluso to dispute resolution, leading ultimately to the appointment of an arbitrator.

[14] At the time of this hearing it appears that the trustees may take some issue in relation to the arbitration process but the evidence before the Court indicates that the dispute over the non-registration of the encumbrance is now to be considered as the subject matter of an arbitral process.

Application that caveat not lapse – the principles

[15] The principles which I adopt in relation to Navilluso’s application are these:

(a) The burden of establishing that Navilluso has a reasonably arguable case for the interest claimed is upon Navilluso as caveator;

(b) Navilluso must show an entitlement to, or beneficial interest in, the estate referred to in the caveat by virtue of an unregistered agreement or an instrument or transmission or of any trust expressed or implied: s 137 Land Transfer Act 1952;

(c) The summary procedure involved in an application of this nature is wholly unsuitable for the determination of disputed questions of fact – an order for removal of the caveat will not be made unless it is clear that the caveat cannot be maintained either because there was no valid ground for lodging it or that such valid ground as then existed no longer does so;

(d) When the applicant’s burden has been discharged, there remains a discretion as to whether to remove the caveat, which will be exercised cautiously;

(e) The Court has jurisdiction to impose conditions when making orders.

[16] As these principles indicate, the caveat lapsing jurisdiction is not fertile territory for a respondent’s attack on the current state of the law, based on arguments of principle or otherwise as to what the law should instead be. The caveator lodges its caveat in the light of the current state of law and is then entitled, assuming its basic facts are made out, to have its caveated interest recognised as at least arguable. The appropriate jurisdiction in which a respondent should argue for alteration or improvement of the existing legal principles is at a substantive hearing when the Court is equipped to deal with the level of sophistication, including analysis of any policy issues, that is required for a reformulation of legal principles.

The existing principles in relation to encumbrance instruments and covenants in gross

[17] As used in land law, a restrictive covenant in gross describes the situation where there is a restrictive covenant in respect of which there is no dominant tenement.1

[18] After years of debate and uncertainty, the New Zealand Court of Appeal in

ANZCO Foods Waitara Ltd v AFFCO New Zealand Ltd overruled authority from the

19th century to the contrary2 and held that covenants in gross cannot run with the land.3

[19] A 1970 article by Professor Brookfield4 is often credited as an important milestone in creating an academically-supported means of protecting restrictive covenants in gross.

[20] Methods subsequently used to protect restrictive covenants in gross were the subject of criticism upon the basis that they were artifices.5

2 Staples & Co (Ltd) v Corby (1899) 17 NZLR 734 (CA).

3 ANZCO Foods Waitara Ltd v AFFCO New Zealand Ltd, above n 1, per William Young J at

[47]–[48], with whom Anderson P and Glazebrook J agreed on this point, per Glazebrook J at

[161] and Anderson P at [296].

4 F M Brookfield “Restrictive Covenants In Gross” [1970] NZLJ 67.

(NZLC R116, 2010) at [7.10].

[21] It is now established by Court of Appeal decisions that a memorandum of encumbrance is an effective conveyancing technique which may be deployed in lieu of a restrictive covenant in gross.6

[22] A covenant, registered as a memorandum of encumbrance under s 203

Property Law Act 2007, takes effect as a mortgage, with the covenant becoming enforceable in accordance with the remedies under the Act, and successors in title when they take subject to the mortgage, becoming liable for performance of the covenant and the mortgagee having all the remedies under the Act for non- performance.7

[23] Certain encumbrances securing rentcharges – largely in the categories recommended by the English Law Commission in 19758 – were expressly preserved in subsequent legislation in the United Kingdom and are similarly preserved in New Zealand through the definition of “mortgage” in the Property Law Act 2007.9

[24] What is referred to in the cases as a “third category rentcharge”10 may include both negative covenants and positive covenants. The adoption of the English Law Commission’s commentary in relation to the third category of rentcharges by Hammond and Chambers JJ in Jackson Mews Management Ltd v Menere indicates clearly that a covenant to not carry on a trade is within the category of rent charges which may be protected by an encumbrance. Their Honours said:11

[28] The Law Commission found third category rentcharges sufficiently beneficial that it exempted them from its proposed ban on the future creation of new rentcharges. The Commission proposed exempting “rentcharges

9 Jackson Mews Management Ltd v Menere & Ors [2009] NZCA 563 per Hammond and

Chambers JJ at [39].

10 For instance, see Jackson Mews Management Ltd v Menere & Ors [2009] NZCA 563 per

Hammond and Chambers JJ at [27].

11 Jackson Mews Management Ltd v Menere & Ors [2009] NZCA 563 at [28].

forming an integral part of schemes beneficial, directly or indirectly, to the

land charged”. The Commission continued at [48]:

The need for this exception arises mainly in cases where a property development has produced a distinct group of separate freehold houses or where a single building is divided into separate freehold parts. In such a situation the preservation, value and enjoyment of each unit may well depend upon the observance of certain covenants by the owners of the other units. These covenants may be negative in form (such as a covenant not to carry on a trade), or they may be positive (for example, a covenant essential in a block of flats, that each unit owner will keep his own unit in repair).

[25] As the form encumbrance instrument provided by Navilluso to the trustees

(Appendix A to this judgment) implicitly recognises, the form is stipulated by s 101

Land Transfer Act 1952.

[26] Section 101 of the Act relevantly provides:

101 Forms of mortgage

(1) A mortgage instrument or an encumbrance instrument is required for the purposes of charging any land or estate or interest under this Act or making any such land or estate or interest security for payment of any money.

(2) ... (3) ...

(4) An encumbrance instrument must contain the following information:

(a) the land or estate or interest to be encumbered, which must include a reference to the register in the prescribed manner; and

(b) the person for whose benefit the land or estate or interest is to be encumbered; and

(c) the nature of the sum, annuity, or rentcharge secured; and

(d) the events (if any) on which the sum, annuity, or rentcharge becomes or ceases to be payable; and

(e) the covenants and conditions (if any).

(5) An encumbrance instrument must be executed by the encumbrancer. (6) ...

[27] As indicated by s 101(1) the focus of the form is on identifying the security for the payment of any money by the mortgagor or encumbrancer. Accordingly,

under s 101(4) an encumbrance instrument is required to contain information as to the nature of the sum, annuity or rentcharge secured. (Section 101(2) which deals with mortgage instruments has parallel requirements).

The nature of the security in this case (s 101(4)(c) Land Transfer Act 1952)

The draft encumbrance instrument

[28] Navilluso has recognised by its draft encumbrance instrument the proposition that it must point to a rentcharge which is secured by the encumbrance instrument.

[29] The draft encumbrance instrument states under the “Nature of security”:

An annual rent charge (sic) of $460,000.00 plus GST if any (continued in the annexure schedule)

[30] Under “Encumbrancer’s Obligations” in the Annexure schedule this is stated:

3. The Encumbrancee covenants with the Encumbrancer not to make demand for payment of the rent charge or interest thereon unless the Encumbrancer is in breach of this Encumbrance.

[31] The Encumbrancer’s Obligations, as drafted in the Annexure schedule, reflect those negative covenants which were set out in cl 10.2(a) and (b) of the 10 January

2011 agreement.

Trustees’ submissions

[32] For the trustees, Mr Lawson submitted that Navilluso has no right to the encumbrance asserted in the caveat because of the statutory requirement to state the nature of the sum, annuity or rentcharge secured. He noted that there is no reference in the agreement whereby the trustees are to pay any sum to Navilluso. The payments defined in cl 10.1 of the agreement – a payment of $10,000.00 plus GST per month up to a maximum of 46 months (creating the potential total of

$460,000.00) – are expressly to be paid as rental payments by Navilluso’s subsidiary Tumu to the trustees for the arrangement whereby Tumu gains additional capacity for its manufacturing operation. Thus, ran Mr Lawson’s argument, there is no

rentcharge in this case to meet the minimum requirements for registration. The underlying rentcharge agreement in this case was accordingly unregistrable.

Navilluso’s submissions

[33] For Navilluso, Mr Macfarlane’s submission in relation to the nature of the rentcharge security fell into two parts.

[34] First, in his initial written submissions, Mr Macfarlane’s written response was extremely brief. His submissions said this:

An encumbrance would normally provide for a rentcharge to be payable but only if the covenantor fails to observe and perform the conditions set out in the encumbrance. This is what the $460,000 in the Navilluso encumbrance relates to – the penalty payable if the obligations are not performed. It could have been as little as $9.90.12

[35] Secondly, for the hearing itself, Mr Macfarlane filed a reply submission in which he referred to authority and developed argument upon the basis that there was no uncertainty or gap in the encumbrance agreement such as to lead to invalidity.

A $460,000 rentcharge?

[36] Mr Macfarlane’s initial written submission can be disposed of swiftly as he did not seek to pursue it at the hearing. It is clearly flawed. Mr Macfarlane’s submission contains the assertion that the $460,000 figure mentioned in the draft encumbrance was a sum payable if the trustees’ obligations were not performed, and was impliedly derived from the agreement of 10 January 2011. In fact, the payments under the agreement of up to $460,000 were payments flowing from Tumu to the trustees, not by the trustees to Navilluso or Tumu. They were payments for capacity provided by the trustees.

[37] The $460,000 figure which was transferred from the agreement into the draft encumbrance instrument is of no assistance to Navilluso in its defence of the caveat.

Navilluso must point to some other feature of the agreement or of legal principle which creates certainty in relation to the nature of the security in this case. Mr Macfarlane says that that lies in his second proposition.

Security in the form of a nominal consideration?

[38] For the trustees, Mr Lawson submits that the agreement of 10 January 2011 contains no agreement as to a rentcharge let alone one at the $460,000 mentioned in the draft encumbrance instrument. Mr Lawson notes also the following provisions included within the draft encumbrance instrument but not forming part of the 10

January 2011 agreement:

(a) Interest rate of 10 per cent (Term 3);

(b) Indemnity for all costs, identified through the events specified at cl

10.2(a) and (b);

(c) The activities which the trustees (and any successor in title) would not be permitted to conduct on the land.

[39] Having specifically agreed to register an encumbrance against the title, the trustees must be taken to have known that their encumbrance instrument would (pursuant to s 101 Land Transfer Act 1952) have to include the sum of money, annuity or rentcharge amount to constitute security. Such amounts may be nominal, as for example the $9.90 rentcharge in Jackson Mews.

[40] Payment of a nominal rentcharge does not lead to discharge of the encumbrance unless there has also been performance of the balance obligations under the instrument. Those include the central point of the encumbrance, namely the restrictions as to the use of the land.

[41] Accordingly, on Mr Macfarlane’s submissions, it does not really matter whether what was first suggested by Navilluso in its draft encumbrance instrument was something entirely nominal or not. The trustees had implicitly, by agreeing to register an encumbrance instrument, agreed to include a rentcharge even if nominal.

Requirements of certainty in relation to the rentcharge – the law

[42] For some years the decision of the Court of Appeal in Attorney-General v Barker Bros Ltd13 has frequently been at the centre of interpretation discussions where the parties’ intention to contract is clear, but there is argument as to whether all its terms are certain.

[43] The general approach is also summarised in the decision of the majority of the five-Judge Court of Appeal in Fletcher Challenge Energy Ltd v Electricity Corporation of New Zealand Ltd.14 Blanchard J, delivering the judgment of the majority, said:

[58] The Court has an entirely neutral approach when determining whether the parties intended to enter into a contract. Having decided that they had that intention, however, the Court’s attitude will change. It will then do its best to give effect to their intention and, if at all possible, to uphold the contract despite any omissions or ambiguities (Hillas & Co Ltd v Arcos Ltd [1932] UKHL 2; (1932) 147 LT 503; [1932] All ER 494; R & J Dempster Ltd v The Motherwell Bridge and Engineering Co Ltd [1964] ScotCS CSIH_1; 1964 SC 308 and Attorney- General v Barker Bros Ltd [1976] 2 NZLR 495). We agree with the way in which Anderson J expressed the position in Anaconda Nickel Ltd v Tarmoola Australia Pty Ltd [2000] WASCA 27; (2000) 22 WAR 101 at pp 132-133:

I think it is fair to say, speaking very generally, that where the parties intended to make a final and binding contract the approach of the courts to questions of uncertainty and incompleteness is rather different from the approach that is taken when the uncertainty or incompleteness goes to contractual intention. Where the parties intended to make an immediately binding agreement, and believe they have done so, the courts will strive to uphold it despite the omission of terms or lack of clarity: see Trustees Executors & Agency Co Ltd v Peters [1960] HCA 16; (1960) 102 CLR 537; Upper Hunter County District Council v Australian Chilling & Freezing Co Ltd (1968) 118

CLR 429; Meehan v Jones [1982] HCA 52; (1982) 149 CLR 571. However, the principle that courts should be the upholders and not the destroyers of bargains, which is the principle that underlies this approach, is not applicable where the issue to be decided is whether the parties intended to form a concluded bargain. In determining that issue, the court is not being asked to enforce a contract, but to decide whether or not the parties intended to make one. That inquiry need not be approached with any predisposition in favour of upholding anything. The question is whether there is anything to uphold.

14 Fletcher Challenge Energy Ltd v Electricity Corporation of New Zealand Ltd [2002] 2 NZLR

433 (CA) at [58].

[44] Consistency in the approach of the Court of Appeal between the 1970s (when Barker Bros was decided) and 2001 (when Fletcher Challenge was decided) is reflected in the following passage from the judgment of Blanchard J:15

We agree with Professor McLauchlan (“Rethinking Agreements to Agree” (1998) 18 NZULR 77 at p 85) that “an agreement to agree will not be held void for uncertainty if the parties have provided a workable formula or objective standard, or a machinery (such as arbitration) for determining the matter which has been left open”. We also agree with him that the Court can step in and apply the formula or standard if the parties fail to agree or can substitute other machinery if the designated machinery breaks down. This is generally the approach taken by this Court in Attorney-General v Barker Bros Ltd.

[45] The courts will, when appropriate, adopt (as in Barker Bros itself) widely drafted arbitration clauses to provide a mechanism for determining matters left by the parties for later agreement and may go so far as to remedy a defective machinery provision.16 But, as the judgment of Blanchard J in Fletcher Challenge indicates, the Barker Bros approach applies not only where the Court is availing itself of a machinery provision such as arbitration, but also applies where the Court can look to some other “workable formula or objective standard”.

[46] These latter words mirror the approach adopted by the Privy Council, in the judgment of Lord Wilberforce, in Cudgen Rutile (No 2) Pty Ltd v Chalk,17 where his Lordship observed:18

Their Lordships consider that, in modern times, the courts are readier to find an obligation which can be enforced, even though apparent certainty may be lacking as regards some term such as the price, provided that some means or standard by which that term can be fixed can be found (cf Hillas & Co Ltd v Arcos Ltd [1932] UKHL 2; (1932) 147 LT 503; Sweet & Maxwell Ltd v Universal News Services Ltd [1964] 2 QB 699 and Godecke v Kirwan [1973] HCA 38; (1973) 47 ALJR 543).

[47] The Court’s task in construing the contract in these situations was summarised by Keane CJ in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v

Fortescue Metals Group Ltd:19

15 Ibid, at [62].

16 See, for instance, Money v Ven-Lu-Ree Ltd [1988] 1 NZLR 685 (CA); Money v Ven-Lu-Ree Ltd

[1989] 3 NZLR 129 (PC).

17 Cudgen Rutile (No 2) Pty Ltd v Chalk [1975] AC 520.

18 Cudgen Rutile (No 2) Pty Ltd v Chalk [1975] AC 520 at 536, adopted in Attorney-General v

Barker Bros Ltd [1976] 2 NZLR 495 (CA) at 499.

19 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Fortescue Metals Group Ltd (2011) 274

ALR 731 (FCA) at [122].

It is well-established that the courts strive to uphold bargains: Hillas & Co. Ltd v Arcos Ltd [1932] UKHL 2; [1932] All ER Rep 494. To that end, the courts will construe the terms of an agreement with an inclination to give effect to the intention of the parties, even if that intention has been obscurely expressed: Australian Goldfields NL (in liq) v North Australian Diamonds NL [2009] 72 ACSR

132; [2009] WASCA 98, especially at [6]-[8]. Further, the courts may, where circumstances permit, apply objective standards of reasonableness to prevent

the intention of the parties being defeated. And where the want of an express provision in an agreement can be supplied by implying a term in order to

give efficacy to the bargain, the courts will make the necessary implication: Electricity Corporation of New Zealand Ltd v Fletcher Challenge Energy Ltd [2002] 2 NZLR 433 at [64]-[67]; Moffat Property Development Group

Pty Ltd v Hebron Park Pty Ltd [2009] QCA 60.

[48] The Court’s approach of “doing its best to give effect to [the parties’] intention (per Blanchard J in Fletcher Challenge) is reinforced when the parties have already themselves acted on and implemented the other terms of the agreement.

Requirements of certainty in relation to the rentcharge - discussion

[49] As a part of their contractual commitments entered into on 10 January 2011, the parties clearly intended to have a binding commitment by the trustees (as encumbrancer) to Navilluso and its Associated Persons (as encumbrancees). In the months after the agreement was executed, the parties acted upon it and implemented its terms, (Mr O’Sullivan of Navilluso deposing that “the agreement worked well...”), save that the trustees did not execute and register an encumbrance instrument either in a form drafted by Navilluso or at all.

[50] This is accordingly one of those cases where the Court must strive to uphold the agreement.

[51] I accordingly ask myself whether there is some means or standard by which the amount of security may be fixed.

[52] Navilluso suggests to the Court the simplest of solutions. By reference to the example of nominal consideration in Jackson Mews (a $9.90 rentcharge), Mr Macfarlane invites the Court to conclude that the trustees were entitled by the agreement to specify in the encumbrance instrument nominal consideration of any value.

[53] This approach sits well with the mechanism advocated by Professor Brookfield in his 1970 article.20 The relevant aspects of the article were summarised by Hammond & Chambers JJ in Jackson Mews thus:21

Further, the Commission would have been well aware of the use of third category rentcharges in New Zealand, at least since the 1960s, if not earlier. Professor Brookfield, a leading New Zealand land lawyer, referred to the use of third category rentcharges (as we are calling them) in an instructive article, “Restrictive Covenants in Gross” [1970] NZLJ 67. In that article, Professor Brookfield provided a precedent for an encumbrance securing a rentcharge. T he r ent charge i t sel f was nomi nal : an annual charge of “fi ve cents to be paid by the 1st day of January in each year if demanded by that date (the first payment if so demanded being due by the 1st day of January

1969) ”. T he r eal point of t he enc umbr a nce, as here and as in other third category cases, was not to procure the actual payment of the rentcharge but to bind the encumbrancer and his or her successors, at that time by s 104 of the 1952 Act, to do certain things and not to do other things. Professor Brookfield remarked that a memorandum of the sort he advocated had “been accepted somewhat reluctantly by a District Land Registrar”: at 71. Professor Brookfield suggested, “with some confidence”, that the Registrar’s reluctance was unjustified. We agree with that observation, and there is now no dispute about the appropriateness of the registration of third category rentcharges.

[Emphasis added]

[54] Both in the narrative of the Brookfield article and in the sample precedent to which Hammond & Chambers JJ refer, the consideration is nominal. Their Honours emphasise that the essential value of the encumbrance instrument from the encumbrancee’s point of view lies in its existence (thereby requiring the encumbrancer to do certain things and not to do other things) rather than in the value of any payment that will be received under it. Payment of the rentcharge is simply not the point of the instrument.

[55] Accordingly, I accept the thrust of Mr Macfarlane’s submission that there is, in this case, an objective standard of reasonableness which the Court must take to fill what the trustees were required to identify as to the nature and amount of security in the encumbrance instrument. Navilluso and its associated persons as encumbrancees can be taken, for the reasons identified by Professor Brookfield and the Court of Appeal in Jackson Mews, to have not been concerned as to the precise (nominal) amount to be identified. The definition of the amount was therefore left to the

trustees as encumbrancer. They may enter the amount they see fit to enter, provided

20 F M Brookfield “Restrictive Covenants In Gross” [1970] NZLJ 67.

it is at the least a nominal monetary sum whether at the level of Professor Brookfield’s nominal five cents, the nominal $9.90 as in Jackson Mews or of some other amount.

[56] New Zealand Dairy Board v New Zealand Co-operative Dairy Co Ltd22 is a case in which this court applied Attorney-General v Barker Bros Ltd. Gallen J, having referred to the Court of Appeal judgment in Barker Bros, summarised:23

It seems to me that on the cases, on the one hand there are those situations where either the nature of the subject-matter or some other circumstances within the context, provide a sufficient standard to allow an arbitrator to come to a conclusion within what may be seen to have been the intentions of the parties.

[57] The nature of the subject-matter in this case – an encumbrance instrument protecting the covenant – is precisely the context which indicates a standard to allow, in this case, the Court to reach a conclusion as to the term of the instrument which will meet what may be seen to have been the intention of the parties.

[58] A similar conclusion applies to other provisions in the Encumbrance Instrument. While Navilluso’s draftsperson included in the draft suggestions as to matters such as an interest rate on the rentcharge and a form of indemnity, such matters are in precisely the same category as the rentcharge itself. The parties chose not to include them in the agreement. The encumbrance context indicates, as the Court of Appeal in Jackson Mews reinforced, that the essential provision was the security instrument itself, which enabled registration of the encumbrance instrument by way of security. Other possibilities, whether as to interest or otherwise, simply fall away unless subsequently the trustees agree to them. If they do not, then they must simply register an instrument with the bare (nominal) rentcharge which takes effect as a mortgage, and the covenants become enforceable as the parties intended.

[59] The obligation of the trustees to get on and register the encumbrance is emphasised by a later, general provision of the agreement which requires each party to take such further action and to execute such further documents as may reasonably

be required to give full effect to the agreement according to its intent. One aspect of

23 Ibid, at 375.

the full effect of the agreement is Navilluso’s ability to enforce the restrictive

covenant through the encumbrance instrument under cl 10.2.

[60] These conclusions answer positively the two questions put by Professor D W McLauchlan in his 1998 article.24 The questions are:

(a) First, did the parties intend to be bound at the time of their initial agreement? The answer in this case is that they clearly did.

(b) Secondly, assuming they did, is that intention capable of being given legal effect? The answer is, again, that it is – it is simply a matter of the trustees completing the relevant part of the encumbrance instrument by inserting words reflecting nominal consideration whether of five cents or otherwise.

[61] I do not overlook the fact that in the period after the agreement was entered into, Navilluso’s solicitors forwarded their own draft of an encumbrance instrument, with the nature of security provision completed with the words:

An annual rent charge of $460,000.00 plus GST if any (continued in the annexure schedule).

(The Annexure Schedule, as I have recorded, went on to provide some additional provisions such as in relation to interest.)

[62] What was in the mind of the solicitor or clerk who prepared the draft instrument is not admissible in evidence. He or she is not the contracting party. In any event, to consider someone’s subjective understanding of the agreement, after the agreement was entered into, would be to consider clearly inadmissible material. It may be that the draftsperson, finding an agreement which did not identify a specific sum as rentcharge, decided for largely arbitrary reasons to adopt the figure of $460,000 which happened to appear in a separate provision of the contract and related to a 46 month, rather than an annual period. That seems likely, but it ultimately does not matter. When approaching the interpretation of this contract, the

draft version of the easement instrument is irrelevant.

24 D W McLauchlan “Rethinking Agreements to Agree” (1998) 18 NZULR 77 at 77-78.

[63] The agreement contains, in cl 15.3, an “entire agreement” clause which reads:

Entire agreement: This Agreement constitutes the entire agreement of the parties in respect of the matters covered by it and supersedes and extinguishes all earlier negotiations, understandings and agreements, whether oral or written, between the parties in respect of those matters.

[64] Mr Lawson submitted that this clause was an additional factor against

“importing additional terms” into the agreement.

[65] The purpose of “entire agreement” clauses is well-understood – namely to exclude evidence adduced to prove terms additional to or different from the written instrument or collateral terms or to construe an instrument in a way different from the meaning to be inferred solely from its terms: MacDonald v Shinko Australia Pty

Ltd.25

[66] That said, an entire agreement clause will not usually prevent the identification of terms arising from the construction of the agreement itself. The observation of Isaacs J in Hart v MacDonald26 illustrates this:

It [the entire agreement clause] excludes what is extraneous to the written contract: but it does not in terms exclude implications arising on a fair construction of the agreement itself, and in the absence of definite exclusion, an implication is as much a part of a contract as any term couched in express words.27

[67] The entire agreement clause in this case (cl 15.3) did not purport to exclude terms implied from the agreement itself. The purpose of an entire agreement clause, as Lightman J put it in Inntrepreneur Pub Co v East Crown Ltd,28 is to preclude a party from “threshing through the undergrowth” and finding some chance remarks on which to found a claim. There is a term to be arguably implied in this case precisely because it meets the requirements for a term to be implied on the face of

the contract itself.

25 MacDonald v Shinko Australia Pty Ltd [1999] 2 Qd R 152 at 156.

26 Hart v MacDonald [1910] HCA 13; (1910) 10 CLR 417 at 430 (HCA).

27 See generally Kim Lewison and David Hughes The Interpretation of Contracts in Australia

(Thomson Reuters, Sydney, 2012) at [3.13].

Inntrepreneur Pub Co v Sweeney [2002] 2 EGLR 132 at 139.

[68] For the trustees, Mr Lawson initially advanced two additional grounds of opposition which he did not press in oral submissions. It is sufficient that I review them briefly.

Lack of consideration

[69] Mr Lawson had noted that the agreement does not record any consideration for the trustees’ promise, under cl 10.2, to not permit specified activities on their land. In contrast, Mr Lawson pointed to the express consideration identified in cl

10.1 and 10.3 of the agreement.29 The point taken in opposition invited the Court to

infer that because no consideration was expressly identified in cl 10.2, then the parties must be taken to have agreed that there was no consideration flowing for the trustees’ undertakings in relation to activities on their land.

[70] Without my having to decide that there was consideration for the cl 11.2 undertaking, it is clearly arguable that consideration exists. Tumu, by the agreement, entered into a package of terms and conditions, including an agreement to purchase goods from Fernwood at agreed prices. It is not for the Court to assess the adequacy of the consideration. At the very least, consideration for each condition of the contract arguably flowed through the benefits received under the range of terms (even if cl 10.1 and 10.3 specifically are left aside).

Restraint of trade

[71] The trustees’ notice of opposition asserted that the proposed restrictive covenant is an unreasonable restraint of trade. Mr Lawson’s written submissions briefly (in three paragraphs) developed the proposition that the trustees’ undertakings in cl 8.2 constituted a restraint of trade of unreasonable effect and duration. He referred to the trustees’ evidence that they had been under the impression that the restraint endured only for the period of the trading arrangements and not for longer

(be it 25 years or in perpetuity). Such evidence of subjective understanding is, of course, not admissible.

[72] All contractual provisions in restraint of trade are prima facie void and the common law rules relating to restraint of trade apply to New Zealand.30 But the testing as to whether particular contractual provisions are unreasonable and the exercise of the Court’s discretion under s 8 of the Illegal Contracts Act 1970, in such event, to modify such contracts, renders this ground of opposition unsuitable for determination against Navilluso in this context. It was appropriately not developed

at the hearing by Mr Lawson.

Mortgage difficulties for the trustees?

[73] The possibility of difficulties with their mortgagee/bank was not raised in the

trustees’ ground of opposition but was referred to in their evidence.

[74] It appears from the evidence that the trustees, some months after the agreement was entered into, decided to resist Navilluso’s efforts to obtain registration of an encumbrance instrument. Differing explanations were given over a period of time.

[75] Richard Kinnear, the managing director of Fernwood, has deposed that the trust proposal has at all times been subject to a mortgage to a bank. The bank has never consented to the registration of any encumbrance. Kinnear goes on to state what the bank’s fears are (a decrease in the value of the property). The encumbrance he gives on that topic is not admissible evidence of its truth, but it is at the least an explanation of why the bank might resist the registration.

[76] Mr Lawson did not seek to develop a submission from this evidence that there should be any consequence in this caveat lapsing proceeding. If Mr Kinnear’s evidence hints that it may have become impossible to register the encumbrance, then that is an argument to be properly developed, on admissible evidence, at a trial. For now, the Court is dealing with a contractual commitment to register an encumbrance which is at the very least originally capable of registration. I note that issues with

existing or prospective mortgagees in relation to encumbrance instruments are not a novel concept – in his 1970 article Professor Brookfield noted31 that a memorandum of encumbrance may be at least a nuisance when the covenantor or his successor in title attempts to mortgage the property.

[77] Navilluso has established a reasonably arguable case for the interest claimed in the caveat. It is entitled to the order it seeks.

Orders

[78] I order:

(a) Caveat no 8696047.1 registered by the applicant against an estate in fee simple in all that land described and contained in Certificate of Title 323998 (Hawkes Bay Registry) shall not lapse.

(b) The respondents shall pay to the applicant the costs of and incidental to this application on a 2B basis together with disbursements to be fixed by the Registrar.

Associate Judge Osborne

Solicitors:

Sainsbury Logan & Williams, PO Box 41, Napier

Lawson Robinson, PO Box 45, Napier 4140

31 F M Brookfield “Restrictive Covenants In Gross” [1970] NZLJ 67 at 70.

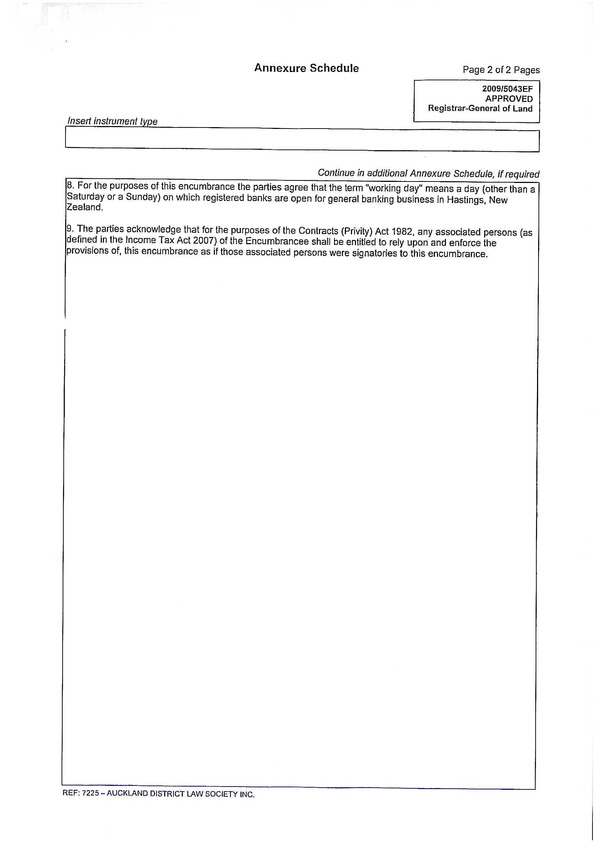

APPENDIX A

NZLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.nzlii.org/nz/cases/NZHC/2012/2766.html