|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

High Court of New Zealand Decisions |

Last Updated: 5 April 2012

IN THE HIGH COURT OF NEW ZEALAND AUCKLAND REGISTRY

CRI-2008-004-029179 [2012] NZHC 665

THE QUEEN

v

RODNEY MICHAEL PETRICEVIC CORNELIS ROBERT ROEST PETER DAVID STEIGRAD

Hearing: 25-26 October 2011, 14-18, 21-24, 28 November 2011; 6-7, 15

December 2011, 23-27, 31 January 2012, 1-3, 7-9, 13-15, 20-24, 27-

29 February 2012, 1-2, 5-7, 14, 16, 19-20 March 2012

Appearances: B Dickey, W Cathcart and T Molloy for Crown

C B Cato for Mr Petricevic

P Dacre and R Butler for Mr Roest

B Keene QC, M E Cole, S Nicolson and J F Anderson for Mr Steigrad

Verdicts: 5 April 2012

REASONS FOR VERDICTS OF VENNING J

Solicitors: Crown Solicitor, Auckland

Lowndes Jordan, Auckland

Copy to: B Keene QC, Auckland,

M E Cole, Auckland, C Cato, Auckland

P E Dacre, Auckland

R Butler, Auckland

J F Anderson, Auckland

R V PETRICEVIC HC AK CRI-2008-004-029179 [5 April 2012]

Table of Contents

Para No Summary [1] Judge alone trial [6] General background [10] Legal considerations [28] Prejudice/sympathy [33] Lies [34] Expert evidence [37] The position of the co-accused [40] The charges [42]

Count 1 – Section 242 Crimes Act 1961 – False statement by a promoter etc.

Count 1 – Mr Petricevic

Count 1 – Mr Roest

Count 2 – Section 242 Crimes Act 1961 – False statement by a promoter etc.

Count 2 – Mr Petricevic

The 31 March interest run

Count 2 – Mr Roest

Count 3 – Section 242 Crimes Act 1961 – False statement by a promoter etc.

Count 4 – Section 242 Crimes Act 1961 – False statement by a promoter etc.

Count 5– Section 242 Crimes Act 1961 – False statement by a promoter etc.

Count 6 – Section 242 Crimes Act 1961 – False statement by a promoter etc.

Count 7 – Section 377(2) Companies Act 1993 – false statements Count 8 – Section 377(2) Companies Act 1993 – false statements Count 9 – Section 58(3) Securities Act 1978 – criminal liability

for misstatement in registered prospectus

Particular (a): That Bridgecorp would/did not provide

credit or advance loans other than in accordance with good commercial practice and internal credit approval policies

(i) Kinloch/Bendemeer

(ii) Dhuez/Akau

(iii) Myers Park Apartments Ltd

(iv) Victoria Quarter Depot Site

(v) Gateway to Queensland Real Estate (NZ) Ltd

(vi) West Auckland Residential Developments Ltd

(WARD) loan

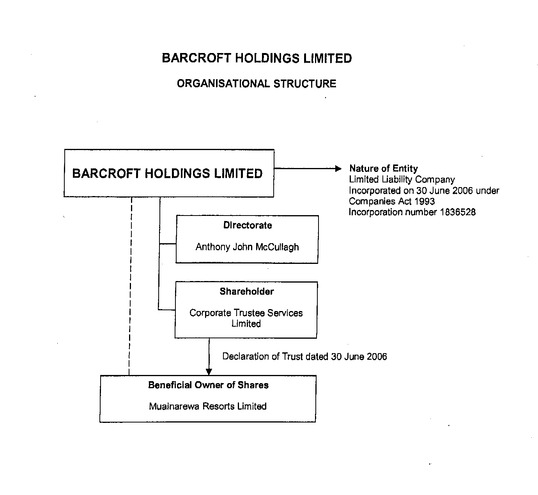

(vii) The loan to Barcroft

(viii) The background to Barcroft – Momi Bay

Particular (b): That Barcroft Holdings Limited was not a related party

[45]

[49] [85] [100]

[106] [108] [142] [149]

[155] [166] [173]

[178] [189] [198]

[232]

[238] [243] [250] [252] [256] [260]

[266] [268] [291]

Particular (d) – That in the period 30 June 2006 to 21

December 2006 no circumstances had arisen that would adversely affect the trading or profitability of the charging group or the value of its assets or the ability of the charging group to pay its liabilities due within the next 12 months

Particular (e)(i) – That Bridgecorp managed liquidity risk by maintaining a minimum cash reserve on bank deposit

Particular (e)(ii) – The omission of a material particular being the actual deterioration in Bridgecorp’s liquidity since year end 30 June 2006

Count 9 – Mr Petricevic’s belief Count 9 – Mr Roest’s belief Count 9 – Mr Steigrad’s position

Count 10

Particulars

Count 10 – Mr Petricevic Count 10 – Mr Roest Count 10 – Mr Steigrad

Count 11

Particulars of untrue statement

Count 11 – Mr Petricevic

Count 11 – Mr Roest

Count 11 – Mr Steigrad’s position

Extension certificate

Count 12

Count 12 – Messrs Petricevic and Mr Roest

Count 12 – Mr Steigrad

Count 13

Count 13 – Messrs Petricevic and Mr Roest

Count 13 – Mr Steigrad

Count 14

Particulars of untrue statement

Count 14 – Messrs Petricevic and Mr Roest

Count 14 – Mr Steigrad

Count 15

Particulars of untrue statement

Count 15 – Messrs Petricevic and Roest

Count 15 – Mr Steigrad

Count 16

Count 16 – Messrs Petricevic and Roest

Count 16 – Mr Steigrad

Count 17

Count 17 – Messrs Petricevic and Roest

Count 17 – Mr Steigrad

Count 18

Count 18 – Messrs Petricevic and Roest

Count 18 – Mr Steigrad

Conclusion

[317]

[345] [349]

[376] [393] [402] [420] [421] [427] [429] [433] [455] [456] [465] [472] [476] [478] [522] [529] [530] [531] [536] [537] [538] [539] [544] [545] [547] [548] [555] [556] [557] [565] [566] [567] [574] [575] [576] [584] [585] [586]

Summary

[1] At material times Messrs Petricevic, Roest and Steigrad were directors of Bridgecorp Limited (Bridgecorp) and Bridgecorp Investments Limited (BIL). All three have been charged with 10 counts under s 58 of the Securities Act 1978. In addition, Messrs Petricevic and Roest have also been charged with six counts under s 242 of the Crimes Act 1961 and two counts under s 377(2) of the Companies Act

1993. The charges arise out of the alleged failures of the accused as directors of

Bridgecorp and BIL.

[2] In summary the charges are:

(a) Count 1 – On 30 March 2007 Messrs Petricevic and Roest made a false statement in the Prospectus Extension Certificate for Bridgecorp’s Term Investments Prospectus dated 21 December 2006;

(b) Count 2 – Between 30 March 2007 and 2 July 2007 Messrs Petricevic and Roest made a false statement in Bridgecorp’s Term Investments Prospectus dated 21 December 2006;

(c) Count 3 – Between 7 February 2007 and 2 July 2007 Messrs Petricevic and Roest made a false statement in Bridgecorp’s Term Investments Investment Statement dated 21 December 2006;

(d) Count 4 – On 30 March 2007 Messrs Petricevic and Roest made a false statement in the Prospectus Extension Certificate for BIL’s Capital Notes Prospectus dated 21 December 2006;

(e) Count 5 – Between 30 March 2007 and 6 July 2007 Messrs Petricevic and Roest made a false statement in BIL’s Capital Notes Prospectus dated 21 December 2006;

(f) Count 6 – Between 7 February 2007 and 6 July 2007 Messrs Petricevic and Roest made a false statement in BIL’s Capital Notes Investment Statement dated 21 December 2006;

(g) Count 7 (as amended by leave on 15 February 2012) – Between 30

April 2007 and 1 May 2007 Messrs Petricevic and Roest made a false statement in the Director’s Certificate dated 30 April 2007 to Covenant Trustee Company Limited in relation to the affairs of Bridgecorp;

(h) Count 8 – Between 19 April 2007 and 1 May 2007 Messrs Petricevic

and Roest made a false statement in the Director’s Certificate dated 19

April 2007 to Covenant Trustee Company Limited in relation to the affairs of BIL;

(i) Count 9 – Between 21 December 2006 and 7 February 2007 all accused distributed a prospectus, namely Bridgecorp’s Term Investments Prospectus dated 21 December 2006, that contained an untrue statement;

(j) Count 10 – Between 7 February 2007 and 30 March 2007 all accused distributed a prospectus, namely Bridgecorp’s Term Investments Prospectus dated 21 December 2006, that contained an untrue statement;

(k) Count 11 – Between 30 March 2007 and 2 July 2007 all accused distributed a prospectus, namely Bridgecorp’s Term Investments Prospectus dated 21 December 2006, that contained an untrue statement;

(l) Count 12 – Between 21 December 2006 and 7 February 2007 all

accused distributed BIL’s Capital Notes Prospectus dated 21

December 2006, that contained an untrue statement;

(m) Count 13 – Between 7 February 2007 and 30 March 2007 all accused distributed a prospectus, namely BIL’s Capital Notes Prospectus dated

21 December 2006, that contained an untrue statement;

(n) Count 14 – Between 30 March 2007 and 6 July 2007 all accused

distributed a prospectus, namely BIL’s Capital Notes Prospectus dated

21 December 2006, that contained an untrue statement;

(o) Count 15 – Between 21 December 2006 and 7 February 2007 all accused distributed an investment statement dated 21 December 2006 relating to Bridgecorp’s term investments, that contained an untrue statement;

(p) Count 16 – Between 7 February 2007 and 2 July 2007 all accused distributed an investment statement dated 21 December 2006 relating to Bridgecorp’s term investments, that contained an untrue statement;

(q) Count 17 – Between 21 December 2006 and 7 February 2007 all accused distributed an investment statement dated 21 December 2006 relating to BIL’s Capital Notes Investment Statement, that contained an untrue statement;

(r) Count 18 – Between 7 February 2007 and 6 July 2007 all accused distributed an investment statement dated 21 December 2006 relating to BIL’s Capital Notes Investment Statement, that contained an untrue statement.

[3] Two other directors, Messrs Davidson and Urwin, were charged in respect of the 10 counts under the Securities Act. Mr Davidson pleaded guilty on 2 September

2011 and was sentenced by Andrews J on 7 October 2011. Mr Urwin was arraigned with the present accused and pleaded not guilty. After the Crown had opened but before the first witness was called, Mr Urwin changed his pleas to guilty. He is for sentence later this month.

[4] Earlier today I found Messrs Petricevic and Roest guilty on all counts. I

found Mr Steigrad guilty on counts 10, 11, 13, 14, 16 and 18 and not guilty on counts

9, 12, 15 and 17.

[5] These are my reasons for returning those verdicts.

Judge alone trial

[6] In R v Connell1 the Court of Appeal stated that a Judge hearing a criminal trial without a jury is required to deliver:

... a statement of the ingredients of each charge and any other particularly relevant rules of law or practice; a concise account of the facts; and a plain statement of the Judge's essential reasons for finding as he does. There should be enough to show that he has considered the main issues raised at the trial and to make clear in simple terms why he finds that the prosecution has proved or failed to prove the necessary ingredients beyond reasonable doubt. When the credibility of witnesses is involved and key evidence is definitely accepted or definitely rejected, it will almost always be advisable to say so explicitly.

[7] In R v Eide2 the Court of Appeal confirmed the principles stated in Connell

but made the following additional observations in respect of fraud prosecutions:

The problems with short-form judgments are particularly acute in fraud prosecutions. The parties (that is, the prosecutor and accused) are obviously entitled to know the key elements of the Judge’s reasoning. In a case of any complexity, this will not be possible unless the Judge provides an adequate survey of the facts. As well, in this context a Judge is addressing an audience which is wider than the prosecutor and accused. If the verdict is guilty, the Judge should explain clearly the features of the particular scheme which he or she finds to be dishonest. There is a legitimate public interest in having the details of such a scheme laid out in comprehensible form. Similar considerations apply if the verdict is not guilty. Further, some regard should be had to how the case will be addressed on appeal. A judgment which is so concise that some of the key facts in the case are required to be reconstructed by this Court on appeal is too concise.

[8] In the more recent case of Wenzel v R3 the Court of Appeal again endorsed the Connell approach and affirmed the comments in Eide regarding fraud cases in

particular.

1 R v Connell [1985] 2 NZLR 233 (CA) at 237–238.

2 R v Eide [2005] 2 NZLR 504 (CA) at [21].

3 Wenzel v R [2010] NZCA 501 at [39]- [40].

[9] While the charges under the Securities Act do not allege fraud, the charges under the Crimes and Companies Acts allege deceit and, as Heath J observed in R v Moses,4 in cases under the Securities Act it is appropriate to give full reasons to explain the verdicts reached. However, to do so it is neither feasible nor necessary to set out in full or to exhaustively review counsels’ extensive opening and closing submissions in these reasons. I have carefully considered the relevant evidence in this case and counsels’ addresses as they relate to that evidence and the charges. In compliance with the above authorities I formally address the elements of the

offending, the principal evidence that bears directly on those elements, my conclusions in relation to those elements and the reasons for those conclusions. Before doing so I set out a brief background to Bridgecorp, BIL and the accused. I also address a number of legal directions that are relevant.

General background

[10] Bridgecorp was incorporated on 30 April 2001. It is a wholly owned subsidiary of Bridgecorp Holdings Limited (in liquidation) (BHL), a company registered in Australia.

[11] BHL was a small public company in New Zealand which was left as a shell after the 1987 sharemarket crash. Interests associated with Mr Petricevic bought it in about 1992. Mr Petricevic sold a portfolio of mortgages into the company in about 1994. BHL then started lending money in its own right and looked to the market to raise further money. It registered its first prospectus in the late 1990’s. At about that time a decision was made to migrate BHL to Australia because the Australian market was seen as having more potential than the New Zealand market. Bridgecorp was then incorporated to continue the business in the New Zealand market.

[12] Bridgecorp’s principal activity was the sourcing of funding and lending in

relation to property financing transactions. It primarily funded the activity through issuing secured debentures to members of the public (who invested in term

4 R v Moses HC Auckland CRI-2009-004-1388, 8 July 2011 at [5].

investments with Bridgecorp) and through issuing redeemable preference shares to

BIL.

[13] In order to raise money and issue secured debentures to the public Bridgecorp was required by the Securities Act to issue prospectuses and investment statements and to register the prospectuses with the Registrar of Companies.

[14] Bridgecorp was also required to appoint a custodian for the debenture holders, Covenant Trustee Company Ltd (Covenant) and to enter a trust deed with Covenant.

[15] BIL was incorporated on 26 April 2002 as a vehicle to raise funds for the New Zealand subsidiaries of BHL. BIL’s primary activity was the issuing of capital notes to the public. It invested the proceeds from those activities into redeemable preference shares issued by Bridgecorp. The redeemable preference shares rank behind all secured and unsecured creditors of Bridgecorp so that BIL’s performance was entirely dependent on Bridgecorp’s performance.

[16] As with Bridgecorp, BIL was required by the Securities Act to issue and register prospectuses with the Registrar of Companies. It also issued investment statements and entered a trust deed with Covenant, similar to the trust deed in relation to Bridgecorp.

[17] The Bridgecorp Charging Group were Bridgecorp Financial Services Ltd (BFS), Bridgecorp Nominees Ltd (BN), Bridgecorp Capital Ltd (BC), B2B Brokers Ltd (B2B), Monice Properties Ltd (Monice), Bridgecorp Australia Pty Ltd (BA), Bridgecorp Finance (Australia) Pty Ltd (BFAL), and Bridgecorp Properties Pty Ltd (BP), the last three being incorporated in Australia. BHL stood outside the Charging Group.

[18] Bridgecorp was placed into receivership on 2 July 2007. At the date of its receivership Bridgecorp had approximately $459 million of secured debenture stock outstanding to approximately 14,500 debenture holders. It is likely that any recovery for the secured debenture holders will be less than 10 cents in the dollar.

[19] BIL was placed into liquidation on 7 July 2007. As at the date of its liquidation BIL had approximately $28.8 million of capital notes outstanding to the public and $30 million redeemable preference shares outstanding in Bridgecorp. It is unlikely that the capital note holders of BIL will recover anything.

[20] At relevant times the accused were directors of both Bridgecorp and BIL. The present accused were described in the relevant prospectus as:

ROD PETRICEVIC – Managing Director

Rod has been involved in the finance industry for more than 30 years and has been a director of a number of publicly listed companies both in New Zealand and Australia. He has access to an extensive range of business contacts and potential opportunities. Rod has been a director of the Bridgecorp group of companies since 1993.

ROBERT ROEST – Finance Director, CA, BCom

Rob has in excess of 25 years of commercial experience in organisations in New Zealand, Australia and the South Pacific, of which the past 7 have been within the finance industry. He has a commerce degree and is a member of the New Zealand Institute of Chartered Accountants. Rob leads the financial and planning activities of the Bridgecorp group and has been a director of the Bridgecorp group of companies since 2006. [Mr Roest was appointed finance director of Bridgecorp on 17 July 2006].

PETER STEIGRAD – Non-executive Director, BE, MBA

Peter is an experienced company director, international businessman and immediate past Chairman of Young & Rubicam Asia Pacific and Dentsu Young and Rubicam. Peter is chairman of the Indigenous Community Volunteers Foundation, a director of the Museum of Contemporary Art and holds a Bachelor of Engineering (Sydney) and MBA (NSW). Peter has been a director of the Bridgecorp group of companies since 2002.

[21] Both Mr Petricevic and Mr Roest, (or entities related to them), held shares in BHL. In Mr Petricevic’s case, Petricevic Capital Ltd held in excess of 3.8 million shares. Mr Roest’s interests held 920,000 shares.

[22] At liquidation Bridgecorp employed 37 staff. The company operated in a number of divisions: finance (including treasury), internal audit, corporate, lending, investor services, credit and marketing.

[23] The two executive directors, Messrs Petricevic and Roest, met with the three non-executive directors, including Mr Steigrad, at the regular monthly board

meetings. In addition there were regular meetings of a number of other committees that Bridgecorp had established – the executive committee, credit committee, audit committee and the asset and liability (ALCO) committee.

[24] The executive committee comprised Messrs Petricevic, Roest, Mike Jeffcoat, (the general manager), (and before him Mike Drummond), John Welch (the treasurer), Will Martin (general manager of finance and company secretary), and, from time to time, Zach McHerron, (the general manager corporate).

[25] The ALCO committee comprised Messrs Petricevic, Roest, Christine Todd (manager of lending), Mr Welch, Mr Martin, Kevin Stephens and Andrew Doidge (business development), Mike Jeffcoat and Andy Harris (the credit manager).

[26] The credit committee was made up of Messrs Petricevic, Roest, and Urwin. Mr Urwin was the Chair until January 2007 when Mr Roest took over. The other attendees, although not formal members, were Mr Harris, Mr Jeffcoat, and the New Zealand Property Finance Manager, Mr Middleton who was later replaced by David Allitt.

[27] The audit committee was made up of Messrs Davidson (chair), Steigrad and Urwin. The audit committee meetings were also attended by Mr Roest, Will Martin, and Mr Kumar (the internal auditor) and, from time to time, a representative from PKF, the external auditors.

Legal considerations

[28] As this is a Judge alone trial I remind myself of a number of matters on which a jury would be directed. They may be fundamental, but as the finder of fact in a criminal trial, it is important I bear them in mind.

[29] The starting point is the presumption of innocence. The onus is on the Crown. The Crown must prove that the accused whose case I am considering at the time is guilty beyond reasonable doubt. The Crown must prove each essential

element of each count against each accused beyond reasonable doubt before I may bring in a verdict of guilty on that count.

[30] Proof beyond reasonable doubt is a very high standard of proof, which the Crown will have met only if I am sure that the accused is guilty. It is not enough for the Crown to persuade me that the accused is probably guilty or even very likely that he is guilty. A reasonable doubt is an honest and reasonable uncertainty left in my mind about the guilt of the accused after I have given careful and impartial consideration to all of the evidence.

[31] The charges in relation to the prospectus and extension certificates under s 58(3) of the Securities Act and those in relation to the investment statements under s 58(1) of that Act are offences of strict liability. The Crown must prove that one or more of the statement(s) in the offer documents is untrue but it is not required to prove criminal intent on the part of the directors in relation to those offences. If the Crown succeeds in establishing the statement is untrue then the onus shifts to the accused to demonstrate, on the balance of probabilities, either that the statement was immaterial or that he had reasonable grounds to believe, and did believe, that the statement was true.

[32] The position is, however, different in relation to the counts under the Crimes and Companies Acts faced by Messrs Petricevic and Roest. In relation to those charges the onus remains with the Crown throughout. The fact that Messrs Petricevic and Roest have given evidence and relied generally on the defence expert Mr Lazelle (called by Mr Steigrad) does not alter the burden of proof. The accused do not have to establish their innocence. The question remains whether the Crown has proved their guilt on those charges beyond reasonable doubt. If I accept the evidence for the accused whose case I am considering at the time about the relevant elements or, if the evidence for the accused leaves me unsure whether the relevant elements have been proved beyond reasonable doubt then the proper verdict is an acquittal on that charge as the Crown will not have discharged its task. If I do not accept the evidence for the accused in relation to the particular elements then I must not leap from that assessment to a finding of guilt. Rather I must then put the accused’s evidence that I have rejected to one side and assess the remaining

admissible evidence that I consider reliable and ask myself whether that evidence satisfies me that the Crown have proved the elements of the particular count to the required standard.

Prejudice/sympathy

[33] I also remind myself that I must reach my decision uninfluenced by prejudice against or sympathy for anyone associated with this case. This case has attracted a large amount of media interest. There has been considerable publicity about the extent of the loss of investors’ funds and the effect on some investors. For their part the accused are all businessmen with no previous convictions. I remind myself to put all feelings of sympathy or prejudice for any party associated or affected by this case to one side.

Lies

[34] If I consider that an accused has lied about certain incidents the fact he has lied is something I can take into account like other evidence. But I remind myself that it is important not to think that just because an accused may have lied on a particular issue or issues he is necessarily guilty of the charges before the Court. I accept that people can lie for reasons other than because they are guilty. Ultimately it is for me as to the weight I place on the lie. The fact an accused may have lied is just one piece of evidence to consider in deciding whether the Crown has proved the relevant elements of the particular offences against the accused beyond reasonable doubt.

[35] Related to that is the issue that counsel addressed for the accused Mr Petricevic. Mr Cato submitted that the fact Mr Petricevic, at the age of 62, had no previous convictions was a factor that indicated he was not likely to have committed these offences or to lie about his actions. I note that logically there will always be a first time for everyone who offends, and evidence of previous good character is not in itself a defence. But it is a factor I bear in mind when I am assessing the accused’s evidence.

[36] During his closing for Mr Petricevic, Mr Cato effectively suggested that Mr Roest may have had a motive to implicate Mr Petricevic and that I should be slow to act on Mr Roest’s evidence concerning Mr Petricevic’s knowledge. I remind myself, when considering that aspect of Mr Roest’s evidence, of Mr Cato’s submission.

Expert evidence

[37] In this case there have been expert accounting witnesses called by both the prosecution and defence. Mr Crichton, an experienced insolvency practitioner, was appointed as an inspector by the then Securities Commission to carry out an inspection of Bridgecorp and BIL for the purposes of considering whether the prospectuses or investment statements contained any untrue statements or whether the companies otherwise breached the securities or financial reporting laws. Mr Crichton gave evidence of his findings. Mr Graham, a partner in KordaMentha, was engaged by the Securities Commission to undertake a peer review of Mr Crichton’s reports. He also considered a number of loans in detail and gave his opinion about Barcroft Holdings Ltd as a related party. Mr McCloy, the receiver of Bridgecorp, gave evidence of his opinion whether the solvency or liquidity position of Bridgecorp, as set out in the company’s prospectuses, reflected Bridgecorp’s true position by 21 December 2006.

[38] Mr Lazelle gave evidence for the defence. Mr Lazelle is the principal of Lazelle Associates Ltd, a company which provides litigation support and forensic accounting services. He is experienced in financial investigations and has a background in the commercial world. Mr Lazelle responded to the evidence of the accountants called by the Crown.

[39] I remind myself that when considering the evidence of the experts I should have regard to the relevant qualifications and experience of the expert accountants who have given evidence. But ultimately the issues in this case are to be resolved by me, not the experts. Ultimately it is for me to decide how much weight or importance to give to the various experts’ opinions or whether I accept them at all in the context of all of the evidence I have heard.

The position of the co-accused

[40] There are two further matters I should refer to. As noted, both Mr Davidson and Mr Urwin have pleaded guilty to the Securities Act charges. The guilty pleas by the other directors to the charges under the Securities Act are irrelevant to the position of the present accused. In assessing the case against the present accused I put the pleas of Messrs Davidson and Urwin entirely to one side.

[41] Related to that is the issue of the statements Mr Davidson and Mr Urwin made to the investigating officers. A number of the witnesses, particularly Mr Crichton, considered those statements prior to trial on the basis that those statements, whilst inadmissible against co-accused, would have been admissible against the director who made them. However as Messrs Davidson and Urwin pleaded guilty and have not given evidence at trial the statements made by them prior to trial are inadmissible against the remaining accused. They properly have not been led and I have not considered them. Where it appears that a witness has relied on the statements I put that aspect of the witness’ evidence to one side. That is particularly the case in relation to aspects of Mr Crichton’s evidence.

The charges

[42] The charges under the Crimes and Securities Acts arise out of statements made in the following documents that were issued by the directors to support the raising of funds from members of the public:

(a) the Bridgecorp Prospectus dated 21 December 2006;

(b) the Bridgecorp Investment Statement dated 21 December 2006; (c) the BIL Capital Notes Prospectus dated 21 December 2006;

(d) the BIL Investment Statement dated 21 December 2006;

(e) the Bridgecorp Director’s Certificate relating to the Extension

Certificate dated 30 March 2007;

(f) the BIL Director’s Extension Certificate dated 30 March 2007. (collectively I refer to the prospectuses, investment statements and extension

certificates as “offer documents”).

[43] The additional charges under the Companies Act arise out of two certificates dated 30 April 2007 and 19 April 2007 provided by the directors to Covenant.

[44] Prior to closing addresses, I provided draft question trails to counsel, identifying what I considered to be the elements of each charge that the Crown (and in the case of the positive defences under Securities Act counts, the accused) had to prove. Counsel agreed with the elements I had identified and I have proceeded accordingly. For Mr Steigrad, Mr Keene raised further legal issues which he submitted were particular to Mr Steigrad. I deal with them in the section that addresses Mr Steigrad’s case.

Count 1 – Section 242 Crimes Act 1961 – False statement by a promoter etc.

[45] The Crown charge that Mr Petricevic and Mr Roest, on or about 30 March

2007 at Auckland and elsewhere in New Zealand, made or concurred in making or publishing a statement that was false in a material particular, with intent to induce any person to subscribe for securities in [Bridgecorp] knowing that the statement was false in a material particular, or being reckless as to whether the statement was false in a material particular.

Particulars of statement

Prospectus Extension Certificate, dated 30 March 2007 for [Bridgecorp] Term Investments Prospectus, dated 21 December 2006 (the Prospectus).

Particulars of falsehood

A statement in the Prospectus Extension Certificate that the Prospectus was not, at 30 March 2007, false or misleading in a material particular by reason of failing to refer, or give proper emphasis, to adverse circumstances, whereas this statement was false, as the Prospectus failed to disclose that [Bridgecorp] had missed interest payments and, when due, repayments of principal.

The relevant extension certificate stated inter alia:

The Securities Act 1978

DIRECTORS’ CERTIFICATE

(Section 37A(1A))

BRIDGECORP LIMITED

1. Bridgecorp Limited has registered prospectus for an issue of secured first ranking debenture stock dated 21 December 2006 (“Registered Prospectus”) pursuant to the Securities Act 1978 at the Companies Office at Auckland.

2. This certificate is given for the purposes of section 37A(1A) of the

Securities Act 1978 in relation to the Registered Prospectus.

3. In the opinion of all directors of Bridgecorp Limited after due enquiry by them –

(a) the financial position shown in the statement of financial position contained in the Registered Prospectus has not materially and adversely changed during the period from the date of that statement of financial position (being 30 June

2006) to the date of this certificate; and

(b) the Registered Prospectus is not, at the date of this certificate, false or misleading in a material particular by reason of failing to refer, or give proper emphasis, to adverse circumstances.

4. Unaudited financial statements for the 6 month period from the date of the statement of financial position contained in the Registered Prospectus accompany this certificate.

DATED: 30 March 2007

[46] The extension certificate was signed on behalf of all directors by Messrs

Davidson and Petricevic. It was registered at the Companies Office on 30 March

2007.

[47] Section 242(1) of the Crimes Act states:

Every one is liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 10 years who, in respect of any body, whether incorporated or unincorporated and whether formed or intended to be formed, makes or concurs in making or publishes any false statement, whether in any prospectus, account, or otherwise, with intent—

(a) to induce any person, whether ascertained or not, to subscribe to any security within the meaning of the Securities Act 1978; ...

[48] To make out the charge the Crown must prove beyond reasonable doubt that: (a) the accused, on or about 30 March 2007, made or concurred in

making or published the Prospectus Extension Certificate for

the Bridgecorp Term Investment Prospectus dated 21

December 2006;

and:

(b) the extension certificate was false in a material particular by failing to disclose that Bridgecorp had missed interest payments and, when due, repayments of principal.

and:

(c) the accused knew the extension certificate was false in that material particular or was reckless as to whether it was false in that material particular;

and:

(d) the accused intended to induce any person, whether ascertained or not, to subscribe to a security in Bridgecorp.

Count 1 – Mr Petricevic

[49] In the case of Mr Petricevic there can be no issue as to the first element. Mr

Petricevic made the certificate. He signed it. Although the certificate is dated 30

March 2007, for the reasons that follow later, I find that Mr Petricevic signed the

certificate on 22 March. That is sufficiently close to 30 March to be “on or about 30

March”. In any event, it could be said the certificate was published on 30 March as that was the date it operated from, following its registration with the Companies Office on that date.

[50] Nor is there any issue that the statement was false in a material particular. As at both 22 and 30 March 2007 Bridgecorp had missed interest payments and, when due, repayments of principal to debenture holders. The evidence of Mrs Todd (investor services manager), Ms White (group accountant), Mr Jeffcoat, Mr Kumar and Mr Roest satisfies me that Bridgecorp failed to make payments of interest and principal that were due to debenture holders on various dates from 7 February through to and including 30 March, the date of the certificate.

[51] Mr Kumar was retained by the receivers to assist with the receivership. He prepared an analysis of the defaults which Mr Crichton then incorporated into a schedule5 which disclosed that on 7 February, debenture maturities (and accrued interest) payments of $642,258.18 were due to be repaid but only $436,166.84 was actually paid that day leaving a shortfall of $206,091.34. There were further shortfalls of varying amounts on 8, 9, 12-14, 22, 23 and 26 February and on 1, 2, 7,

9, 12-19, 27 and 30 March. The Crichton schedule and Kumar summary were based on the debenture maturity schedules prepared by Mrs Todd’s department and the related schedules prepared by Ms White.

[52] Mrs Todd gave evidence as to the practice by which a debenture maturity schedule was prepared for each day. She confirmed that investor payments would not appear on the schedule as due for payment unless the relevant term investment certificate with the appropriate instructions had been received by Bridgecorp. Once the certificates were received they were processed and a schedule setting out payments required to be made on a given day (which Mrs Todd called the daily outwards cash schedule) was completed. The schedule recorded the relevant details including the certificate number, client name and number, principal and interest, tax,

and whether the payment was to be by way of direct credit or cheque.6 Mrs Todd

confirmed that there were several checks in the system to confirm the accuracy of the schedule. Once Mrs Todd confirmed the daily outwards cash schedule was correct it

was transmitted electronically to the accounts department to action payment.

5 Exhibit 10.

6 Exhibit 385B.

[53] Ms White was responsible for ensuring that the payments of principal and interest set out in the daily outwards cash schedule, prepared by investor services, were paid. Following the receivership of Bridgecorp and BIL Ms White prepared a number of schedules to identify the payments that were missed.7 She did so by reconciling the daily outwards cash schedules with the bank batch forms which were created automatically to process the payments identified as required by the outwards

cash schedule. The bank batch forms could only be overridden manually by treasury, usually Mr Martin or Mr Welch. For each investor Ms White’s schedule recorded the actual payment date, the scheduled payment date and the closed date. The scheduled date was the date Bridgecorp had scheduled to make the payment as noted on the daily outwards cash schedule. The closed date was the maturity date of the investment. Normally, all three would co-incide, except that when the maturity fell on a weekend, it was the practice to pay the Friday before, so that the scheduled and actual payment dates would be the Friday. However, after 7 February, there were a number of occasions when the actual payment date records the payment was made after the scheduled and closed dates. As an example the schedule discloses that for investor Grenfell, while the scheduled payment date and the closed date were both 7 February 2007, the actual payment date was not until 8 February 2007.

[54] As part of her spreadsheet analysis Ms White compiled a monthly summary of defaults. Mr Kumar extracted Ms White’s monthly summaries in preparing his summary. Mr Crichton carried out a similar exercise in preparing his schedule. The evidence of Mrs Todd and Ms White, as summarised by Mr Kumar and Mr Crichton, confirms that between 7 February and 30 March 2007 Bridgecorp failed to pay principal and interest to investors on a number of due dates.

[55] I note here that while Mr Roest challenged Mr Kumar’s analysis, his own reworked schedule recorded shortfalls in the payments of principal and interest due on various dates from 7 February on. I deal with Mr Roest’s explanation in relation to what he categorised as delayed payments more fully when considering his case on

this issue.

7 Exhibit 385.

[56] At the conclusion of his evidence, Mr Petricevic confirmed that, in light of the evidence led before the Court, he accepted Bridgecorp (and BIL) had failed to make payments of principal and interest on due dates on a number of occasions from

7 February on.

[57] I reject Mr Cato’s submission the fact the payments were made on the next business day meant they were immaterial. In this context a matter will be material if it is important or something that matters. The question of materiality is to be determined objectively.8 There cannot be any issue that in the case of a finance company the fact it has missed interest payments or failed to repay principal amounts of investments (even by a day) is important or something that matters, particularly

when it has a prospectus before the public.

[58] The principal issues from Mr Petricevic’s point of view in relation to this count (and the remaining counts under s 242) are whether, at the relevant time, he knew or was reckless as to whether the extension certificate (or other document(s)) was false in that material particular and whether he intended to induce any person to subscribe to a security in Bridgecorp.

[59] Mr Petricevic’s defence on this aspect is common to all charges. It is that he did not know of any missed maturity payments of principal at all until 23 June 2007 when all directors were informed that from 20 June 2007, payments had not been made. At that time the directors resolved to take steps to advise Covenant. Mr Petricevic’s evidence was that, while he also became aware, when he arrived at work on Monday 2 April 2007, that the quarterly interest run due on Saturday 31 March

2007 had not been paid, he knew that it was paid later that day. He said he did not regard this as a missed interest payment and was not terribly concerned about it because the interest run was paid on Monday 2 April, the next working day. He maintained in his evidence that the first he learnt of the missed payments of principal and interest prior to 31 March 2007 was after these proceedings were commenced

when he read about it in the newspaper.

8 Sir Bruce Robertson (ed) Adams on Criminal Law (online looseleaf ed, Brookers) at

[CA242.03].

[60] I do not accept Mr Petricevic’s evidence on this issue. I am satisfied beyond reasonable doubt that he knew that Bridgecorp had failed to make payments of principal and interest from early in February and in any event well before the 31st March interest run. I am satisfied as to that for the following reasons.

[61] A number of the senior management team were aware that Bridgecorp had missed payments of principal and interest. Messrs Jeffcoat, Martin and Welch were all aware, as they had to alter the bank batches. Mrs Todd was also aware. She prioritised which of the debenture holders were to be paid when there was insufficient moneys to meet all the maturities scheduled for payment on a particular day. They had various meetings at which the issue was discussed. All gave evidence that Mr Petricevic was also aware of the defaults before the March interest run. With the exception of Mrs Todd, all referred to meetings, attended by Mr Petricevic, at which the issue of missed payments was discussed.

[62] Mr Welch described fortnightly or monthly investor services meetings during early 2006 with Mrs Todd, Mr Petricevic, Mr Jeffcoat and, he thought Mr Roest, (but he wasn’t sure about that) at which the debentures were reviewed and strategies for new moneys were considered. Mr Welch said that at those meetings the missed maturity payments were discussed.

[63] Mr Welch also said that at the monthly executive meetings (which were chaired by Mr Petricevic) the best and worst case cash scenarios were discussed, and he, Mr Welch, made it known that debenture payments had been missed. Mr Petricevic accepted that Mr Welch attended the executive meetings but said there was never any discussion by Mr Welch or anyone of missed maturities at those meetings. While the minutes of the executive committee meetings do not expressly refer to the missed maturity payments they regularly emphasise the need for cash. For example the minutes of the 19 March 2007 meeting record:

![]() a copy of the daily cash flow was

distributed to members,

a copy of the daily cash flow was

distributed to members,

![]() Discussions held on what was being done to improve future

cash flows,

Discussions held on what was being done to improve future

cash flows,

cash flow and day to day cash management is still king.

That is consistent with Mr Welch’s evidence.

[64] Under cross-examination by Mr Cato, Mr Welch accepted he could not recall the name for the meetings where the question of missed payments was discussed but maintained that, whatever they were called, he believed Mr Petricevic attended them. When it was put to him he had not given evidence about that in his initial statement or before trial, he explained that failure on the basis he had not been asked whether there were any other meetings that he was involved in. It was put directly to him that there were no discussions of that kind involving Mr Petricevic or with Mr Petricevic present but he did not accept that. While Mr Welch was not able to refer to any documentation to support his evidence and accepted he could not recall the name for the meetings, he remained firm under cross-examination that Mr Petricevic attended meetings at which the failure to pay debentures was discussed.

[65] Mr Welch’s evidence on this point is supported by the practical situation that existed within Bridgecorp at the time. Mr Welch knew there was insufficient money to make all the repayments required and that payments had been missed. He was monitoring the bank account daily. He needed to know when loans were expected to be repaid (and Mr Petricevic played a large part in managing some of the workout loans in particular) so that he could ensure Bridgecorp would be able to make up the missed payments. It is inevitable the issue of the missed maturity payments would have been raised at the meetings when cash flow and the source of the cash flow was discussed. The whole point of the cash flow meetings was to ensure there was sufficient money to pay Bridgecorp’s obligations to its investors, which a number of witnesses referred to as the company’s priority.

[66] Mr Welch said in his initial statement that if investors were not paid out he would inform Rob (Roest) and Mike (Jeffcoat) in particular, but that is understandable, as they were the people he reported to. It is not inconsistent with his evidence that Mr Petricevic also attended meetings at which the issue was also raised. Further, while Mr Welch accepted that Mr Petricevic did not, himself prioritise the payments, (which was done by Mrs Todd as she had the knowledge of the situation of the various debenture holders), again that it is not inconsistent with his evidence that Mr Petricevic attended meetings at which the issue was discussed.

[67] Mr Martin gave evidence that he became aware of the missed payments in early 2007. He then discussed with Mr Welch what they should do. He said that they would have contacted Rob Roest and asked him what to do. Mr Martin’s focus was more on the payment of Bridgecorp’s general creditors rather than debenture holders but he recalls the debenture holders were also prioritised for payment and that on a couple of occasions Mr Petricevic attended meetings at which the prioritisation was discussed. Mr Martin also suggested the defaults might have been discussed at meetings of the executive committee which is consistent with Mr Welch’s evidence to that effect. While I accept there is some force in Mr Cato’s criticism of Mr Martin’s evidence on the basis that it was general, and at times vague, it is consistent with the evidence of other witnesses as to the issue of Bridgecorp’s inability to pay creditors and investors in early 2007. For example, it is consistent with Jo Tait, the marketing manager’s evidence, that in early 2007 she also discussed the issue that general creditors were not being paid with Mr Petricevic.

[68] From the time Mr Jeffcoat returned from Australia to take up the position as New Zealand General Manager in early February 2007, he held regular, if not daily discussions with Mr Welch regarding the cash flow, which loans were to going to be repaid and what debenture maturities were due. He said that he, Mr Petricevic, Mr Roest, Mr Welch and sometimes Mrs Todd would also get together for a brief update at least weekly and sometimes more regularly than that. Mr Jeffcoat was aware that after 7 February payments of interest and principal had been missed.

[69] Mr Jeffcoat said that there was a meeting, some time between 7 February and prior to 31 March, at which the issue of whether the quarterly interest payment due on 31 March would be made was discussed. He said Mr Petricevic attended the meeting. The idea of explaining to investors that there had been a “computer glitch” if the interest run was not able to be made was discussed. Mr Cato directly challenged Mr Jeffcoat about this evidence and particularly whether Mr Petricevic had been present at the cash flow meetings that Mr Jeffcoat described. Mr Jeffcoat remained firm in his evidence that Mr Petricevic had been present at those meetings. He said he was not mistaken about that. Again Mr Cato made the point in cross- examination and submission that Mr Jeffcoat had not mentioned these meetings in the statement he had provided to the Ministry of Economic Development. Under

cross-examination Mr Jeffcoat did accept that Mr Petricevic may not have been present on every occasion and also accepted that he did not have a perfect recollection of the meetings but rejected the proposition that Mr Petricevic was not at any of the meetings.

[70] The “computer glitch” explanation was given to an investor, Mr Fair who complained when his interest payment due on 31 March was made late. Mr Fair spoke to Chris Todd about the late interest payment. He was apparently given the explanation that a computer processing error had led to the late payments. He referred to that in his letter of complaint. The draft letter of response to Mr Fair was referred to Mr Petricevic. When cross-examined Mr Petricevic conceded that the statement about a computer processing error was a lie and that he knew that it was when he read the letter on 3 April, although he attempted to resile from that later in his evidence.

[71] Mrs Todd was actively involved in the discussions with Mr Welch and other members of the management team as to which investors should be paid when there was insufficient money to pay all the investors scheduled for payment. She played a leading role in identifying which investors would be paid on given days. While she was not able to say definitely that Mr Petricevic attended such discussions, she said on more than one occasion that she was sure Rob (Mr Roest) and Rod (Mr Petricevic) were aware of the situation leading up to the quarterly interest run of 31

March and were both concerned. She said she would see Rob and Rod about the office and tell them.

[72] Mr Cato submitted that Mrs Todd was making the decisions as to who to pay herself, but without reference to Mr Petricevic. While Mrs Todd took the lead in identifying the investors who should be given priority when it was necessary to do so because there was insufficient cash to pay all maturities, the decision was made in conjunction with other senior management and with Mr Roest and Mr Petricevic aware of that process. It is not conceivable that the senior management would have made such decisions without reference to the executive directors, Messrs Roest and Petricevic.

[73] I have considered why such a major issue was not documented or recorded in minutes by any of the staff. The most benign explanation for the failure to expressly or formally record discussions about missed maturities is that while all parties involved, from the executive directors Messrs Petricevic and Roest, down to the management team, knew that payments had been missed, they believed in Bridgecorp and believed that it would get through the current crisis just as it had got through tight patches in the past. The management team were also aware that both the managing director, Mr Petricevic and the finance director, Mr Roest, knew and that might have allayed their concerns.

[74] Next there is the evidence of Mr Roest. Mr Welch and Mr Martin reported, through Mr Jeffcoat, ultimately to Mr Roest. Mr Roest was well aware of the missed (or as he categorised them, delayed) payments in February and March as he accepts.

[75] Mr Roest and Mr Petricevic met regularly, often daily, if they were both in the office. Mr Roest gave evidence that Mr Petricevic was aware of the issues because he had discussions with him about cash flow issues. In cross-examination by Mr Cato, Mr Roest maintained his evidence that, while he did not believe the maturities were missed, they were just delayed, Mr Petricevic was also aware of the delay. Mr Roest supported that evidence by pointing out that Mr Petricevic was well aware of Bridgecorp’s position because he was involved in a lot of the refinancing. While I remind myself of the need to be cautious about Mr Roest’s evidence on this point, I am satisfied Mr Roest’s evidence about Mr Petricevic’s knowledge is reliable. Their offices were beside each other. They both arrived at work early. While Mr Petricevic was involved in a number of projects and may have been away from the office from time to time, they still communicated regularly in the ordinary course of business when both were in the office, which was often. Cash flow was a major issue for Bridgecorp from the middle of 2006 on. Given the situation that Bridgecorp faced at the time, it is logical that Mr Roest and Mr Petricevic would discuss Bridgecorp’s cash flow and its commitments to its investors. The payment of Bridgecorp’s debenture holders was its biggest commitment. Mr Roest described conversations starting with the questions: “What’s the latest?” or “What’s the updates?” That is the sort of discussion which inevitably would lead to a discussion about the missed maturities and the source of funds to enable them to be paid. Mr

Roest had nothing to gain and no reason to withhold information regarding the missed payments from Mr Petricevic, who was the managing director and had a far greater personal interest in the company and BHL than Mr Roest had.

[76] Mr Petricevic’s evidence that he was not aware of the missed principal and interest payments of February and March 2007 until after these proceedings commenced is just not credible. The missed payments were known generally about the office. I cannot accept that Mr Petricevic would not have been one of the first to have such knowledge. A stark example of how far the knowledge extended at an early stage is the email from Michelle Leask (at the time a business development manager) to Ms Wong on 8 March 2007. In response to an email from Ms Wong relating to proposed amendments to the prospectuses for Bridgecorp and BIL and inviting comment whether the prospectuses contained statements that were misleading in form and context or by reason of omission, Ms Leask responded:

Maybe we could tell them that we have no money, can’t pay our bills, are holding back payments, lying to investors and brokers about why their money hasn’t been paid and I’m not confident that we can meet the March interest payments to investors.

[77] It is simply not credible to suggest that in early March someone in Ms Leask’s position would have such a clear insight into the difficulties that Bridgecorp faced but that Mr Petricevic, the managing director, was unaware of the situation.

[78] Mr Petricevic’s evidence on the issue of knowledge was not convincing in a number of respects. I refer to only some of his evidence by way of example. He suggested he signed the extension certificate because Bridgecorp had spent a number of months through until December getting the sign-off and registering the prospectus and, in his mind, the accounts were up to date as at December and everything that needed to be disclosed was disclosed. He said January and February were very, very quiet months and there was not very much happening. He had looked at the management accounts for January and February and was not alerted to anything out of the ordinary in that period of time. The suggestion that somehow because the registration of the prospectus was delayed until December and the extension certificate was signed in March and not much had happened between those particular periods is obviously simplistic. The prospectus included the accounts as at 30 June

2006. The certificate expressly stated the financial position had not changed from that time to 30 March 2007, a nine month period. By his general evidence on this issue Mr Petricevic sought to downplay that factor.

[79] Next, on the issue of his state of knowledge about the missed payments in February and March, Mr Petricevic was taken to Mr Kumar’s review of the investor services department. In that draft report, which was before the board members on 21

June 2007, there was a note:

(b) Late payment of maturity proceeds and interest to investors that was due on 30 March 2007 ($1,674,814), with the payment being made on 3 April 2007.

The above delay has resulted in complaints from investors, as it overlapped the end of the tax year, being 31 March 2007, and was non-compliant with the representations in the Prospectus and Investment Statement.

(c) Late payment of maturity proceeds and interest to investors on certain other days, particularly during March, April and May 2007.

[80] Mr Petricevic was unable to explain how, despite that reference in the report that he had on 21 June 2007, he was able to maintain his position that he only learnt of the missed payments for February and March after these proceedings were commenced. He was forced to try to explain it by suggesting he must not have seen the report because if he had received the report it would have been in his papers and it was not in his papers. I do not accept that explanation.

[81] Further, there were a number of references in the executive committee and board packs to the issue of missed payments. For example, in the April board pack there was reference to a report from the business development department that:

The late payment of interest on debentures and notes and repayment of maturities has done damage to us this month.

Mr Petricevic gave two explanations for not noting that report. First he said that he only read it as referring to missed interest payments. Second he gave a quite different explanation, namely that as it was written by a junior staff member he considered it was in error. Neither explanation bears scrutiny.

[82] I find that Mr Petricevic knew, at the time he signed the extension certificate dated 30 March, that it was false in a material particular in that it failed to disclose Bridgecorp had missed a number of payments of principal and interest to investors by that time. He could not reasonably have believed Bridgecorp was not in default. The defaults applied not only to payments that fell due on weekends but also to payments due during the week.

[83] The last element of the offence is whether Mr Petricevic intended to induce any person to subscribe to a security in Bridgecorp in reliance on the false statement in the extension certificate. Mr Cato submitted that if I found Mr Petricevic had knowledge of the missed payments, then as he believed they would be made up and were not missed at law, this last element could not be established. While I reject that argument it cannot, in any event, apply to the payments missed on working days. Further, some payments were not made up the next day. Finally, while there is no direct evidence as to Mr Petricevic’s intention to induce any person to invest in Bridgecorp I infer that that was his intention at the time he signed the extension certificate. The purpose of the extension certificate was to extend the life of the prospectus. The prospectus had to be extended beyond 30 March in order to enable Bridgecorp to continue to take subscriptions and investments from the public. At this time, early 2007, Bridgecorp needed to maintain its cash inflows. As was noted

in the Board minutes of 19 March 20079 “Cash flow and day to day cash

management is still king”. One of the most obvious and immediate sources of cash was fresh investments from members of the public. I conclude that, in signing the extension certificate which included the false statement, Mr Petricevic intended to induce a person or persons unknown to subscribe to the security in Bridgecorp.

[84] I find count 1 proved against Mr Petricevic.

Count 1 – Mr Roest

[85] The first issue for Mr Roest is whether it can be said he made or concurred in making or published the extension certificate. Mr Roest did not sign the extension

9 The minutes are of the meeting of BHL. The Board did not hold separate meetings for

Bridgecorp or BIL.

certificate. However, the evidence satisfies me that at the least Mr Roest concurred in the making of the extension certificate. For the reasons that follow I am satisfied that the certificate was signed on behalf of all directors by Messrs Davidson and Petricevic and that the certificate was signed at the meeting of directors on 22 March

2007. Mr Roest was at the meeting, knew the extension certificate was required to extend the prospectus and concurred in Messrs Davidson and Petricevic signing the certificate on his behalf. He agreed to the completion and registration of the extension certificate.

[86] In Thompson v R the Court of Appeal accepted the following direction of the trial Judge was correct in relation to what was required to concur in something:10

The crime is concurring in the false omission or the false entry as the case may be. Concurring, in its ordinary meaning, means agreeing with the happening of some event. It is really as simple as that. ... The Crown must prove that the accused agreed to those events happening coupled with the necessary criminal [intent].

[87] As for the second element, for the reasons given above I am satisfied the extension certificate was false in a material particular by failing to disclose that Bridgecorp had missed interest payments and, when due, repayments of principal between 7 February and 30 March 2007.

[88] I also find that Mr Roest knew the extension certificate was false in that material particular. There can be no doubt that Mr Roest was aware that payments were not made on due date from time to time after 7 February. Mr Welch confirmed that if there was insufficient money to pay investors he would normally make sure Mr Roest was aware that they were not paying the full amount. I accept that evidence. As treasurer, Mr Welch was responsible to Mr Roest, who he described as a “micro manager”. As Mr Welch put it, if there was anything out of the ordinary he would be up the other end [of the office] telling him what was going on.

[89] Mr Roest suggested in his evidence that Mr Kumar’s schedules seemed to indicate there were “issues” about the payment of principal and interest from 7

February and he queried whether Mr Kumar had gone back to check that investor

10 Thompson v R (1996) 14 CRNZ 235 (CA) at 243.

instructions were received as were required. The answer to that, however, is that Mr Kumar’s evidence was prepared on the basis of the schedules prepared by Mrs Todd and Ms White. I accept the accuracy of Mrs Todd and Ms White’s schedules. Mr Roest also challenged whether the necessary documentation had been provided by the investors for the payments. Again, Mrs Todd’s evidence satisfies me that only investors who had returned the certificate and provided instructions appeared on the daily cash outwards schedule as due for payment.

[90] I find Mr Roest was aware that payments of principal and interest had not been made from 7 February through to 30 March. Mr Butler submitted that Mr Roest did not believe the certificate to be false as he held a genuine belief the payments had been delayed, but not to a material degree. In his evidence Mr Roest maintained the payments were delayed, rather than missed, and sought to explain the non-payment in a number of ways which, Mr Butler argued, show he lacked the

necessary criminal intent or that at least there was a reasonable doubt on that issue:

![]() there was sufficient money in Bridgecorp’s

bank account or there were other

there was sufficient money in Bridgecorp’s

bank account or there were other

funds available from other members of the charging group or other sources which could have been applied to make the payments;

![]() cheques could have been written out to investors to

make the payments;

cheques could have been written out to investors to

make the payments;

![]() additional interest was paid to the investors when

the payments were delayed and that was, in effect, an extension of the

original

term;

additional interest was paid to the investors when

the payments were delayed and that was, in effect, an extension of the

original

term;

![]() same day clearances on payments meant the investors

would have access to their funds a matter of hours later than if the

funds had

been paid the previous

same day clearances on payments meant the investors

would have access to their funds a matter of hours later than if the

funds had

been paid the previous

day;

![]() payments made after the banks closed on the day

would be processed the next business day even though the payment may have

been

received by the bank the previous day.

payments made after the banks closed on the day

would be processed the next business day even though the payment may have

been

received by the bank the previous day.

[91] Whether the bank statement may show that there was money in Bridgecorp’s main bank account on certain days when the matured debentures were not paid does not alter what occurred, namely that the debenture holders were not repaid on that due date. Further, even Mr Roest’s reworked schedule discloses that on 8 February a cumulative shortfall totalling in excess of $412,000 existed. On that day the bank statement disclosed a balance of only $268,900.03. The same general response applies to the suggestion that funds could have been available from other sources. While the bank statement does disclose deposits from other sources from time to time, including from other members of the charging group, the short point is that principal and interest repayments were missed, despite the best efforts of Messrs Welch, Martin, Jeffcoat, Roest (and Mr Petricevic on occasion) to identify sources of money to meet the repayments due. Mr Roest was aware of the impending defaults. If there were funds available from other sources they would have been applied to ensure the matured debentures were repaid. They were not.

[92] Mr Roest’s suggestion that the problem would have been solved if Bridgecorp had written cheques to pay investors is simplistic and misconceived. Again, it did not happen. Further, the payments were required to be made by direct debit authority in accordance with the investors’ instructions. The prospectus provided that all payments or credits due to the investors would be credited to the bank account or other account specified by the investor in the application form.

[93] In any event, even if cheques had been written to address an initial shortfall on a particular day that would have only postponed the ultimate default. If cheques were written on 7 February to meet the commitments due that date then, when ultimately presented, that would have put further pressure on the funds in the bank account on that date. Writing cheques would simply have put the commencement date of the defaults back. At best the problem would only have been postponed.

[94] The suggestion that the fact Bridgecorp paid additional interest which was accepted by the investor was an extension of the original term is unrealistic and contrived. It was only in cross-examination that Mr Roest identified the clause in the trust deed he relied on, cl 2.5. While that clause permits the alteration of the terms of the debenture securities, as one would expect, there are pre-conditions to such an

alteration. There must be prior arrangement with the holders of the securities and the directors are required to give prior written notice of any such alteration to the trust deed to Covenant. Neither of those pre-conditions were satisfied in this case.

[95] Finally, the suggestion that, in some way the same day clearance of payments (on some limited occasions) and the processing delays by the bank excuse the default is misconceived. Neither address the fundamental point that Bridgecorp failed to meet its obligations to pay on due date. At best the same day clearance system masked the fact the payment was missed on the preceding day by showing the payment in an investor’s bank statement on the same day as it would have appeared if it had been paid on due date.

[96] Mr Roest’s explanation that the payments were not missed but rather were only delayed, but not to a material degree, is specious. If a debenture investment matured and (with accrued interest) was due for repayment on the 7th February but was not paid until the 8th it is a missed payment, as it was not made on due date. While it could also be described as a delayed payment, (in that it was ultimately

paid), it was a missed payment or a default in terms of the trust deed, which is a material event.11

[97] As finance director of a finance company with $529,533,000 of investors’ moneys on hand12 Mr Roest must have appreciated the significance of the failure to pay the principal maturity payments when due.

[98] Finally, for the same reasons discussed in relation to Mr Petricevic on this issue I find Mr Roest intended to induce persons to continue to subscribe to a security in Bridgecorp by making that false statement.13

[99] I find count 1 proved against Mr Roest.

11 Bridgecorp Trust Deed cl 5.1(a)(i).

12 As at 30 June 2006.

13 At [83].

Count 2 – Section 242 Crimes Act 1961 – False statement by a promoter etc.

[100] Count 2 charges that Mr Petricevic and Mr Roest, between on or about 30

March 2007 and on or about 2 July 2007, at Auckland and elsewhere in New Zealand, made or concurred in making or publishing a statement that was false in a material particular, with intent to induce any person to subscribe for securities in [Bridgecorp], knowing that the statement was false in a material particular, or being reckless as to whether the statement was false in a material particular.

Particulars of statement

[Bridgecorp] Term Investments Prospectus, dated 21 December 2006 (the

Prospectus).

Particulars of falsehood

A statement in the prospectus that [Bridgecorp] had never missed an interest payment or, when due, a repayment of principal.

[101] To make out count 2 the Crown must prove beyond reasonable doubt the same general elements identified in relation to count 1.

[102] There is an additional, preliminary issue. The statement in the prospectus that Bridgecorp had never missed an interest payment or, when due, a repayment of principal was correct at the time the prospectus was registered on 21 December

2006. It became false from, and after, 7 February 2007. The prospectus was at that time before the public. The prospectus was extended by the extension certificate registered on 30 March 2007.14 The effect of the extension of the prospectus was that from 30 March until it was suspended on 29 June 2007 the prospectus was before the investing public. Count 2 relates to the time period between 30 March

2007 and 2 July 2007 (the date of Bridgecorp’s receivership). The end date must be

the date of suspension of the certificate.15 For the reasons given above, the

14 Securities Act 1978, s 37A(1A).

15 Although Bridgecorp was not placed in receivership until 2 July 2007, the prospectus was suspended as from 29 June 2007. From suspension the prospectus could not have been before the public to induce subscription for securities.

statement that Bridgecorp had never missed an interest payment or, when due, a repayment of principal was false as from 7 February until 29 June 2007.

[103] Although the statement may have been correct at the date of the initial registration of the prospectus on 21 December 2006, the accused should have withdrawn the prospectus once it became false. Section 34(1) of the Securities Act provides that no registered prospectus shall be distributed if it is false or misleading in a material particular. As directors, if they were aware the statement in the prospectus had become false, then the accused had a positive obligation to correct the false or misleading prospectus by amending that statement or by withdrawing the prospectus. They had the authority and ability to do so.

[104] The accused’s failure to do so in such circumstances is a continuing failure between 30 March 2007 and 29 June 2007. As the Court of Appeal noted in Thompson v R, in response to a submission that concurs carries the concept of timing as in concurrent:16

Even if that were correct, it would make no difference ... since an omission is a continuing event and simultaneous assent to it may be given so long as it continues. We do not accept however that to concur in an act or event the assent must precede or be simultaneous with it. We see no reason to construe the section so as to make it a crime to assent to an entry before or at the time it is made yet not a crime to come upon it afterwards and assent to it in circumstances where there is a duty to correct it, the authority and ability to do so and, of course, the required intent to defraud.

[105] While the Court was discussing s 252 of the Crimes Act in Thompson’s case the above comments are applicable to s 242 as well. In the present case the accused both concurred in making or publishing the statement which became false on 7

February 2007 by leaving the prospectus containing that false statement before the public between 30 March 2007 and 29 June 2007 in circumstances where they had a duty to correct the false statement and also had the authority and ability to do so

either by amending the prospectus or withdrawing it.

16 Thompson v R, above n 10 at 243.

Count 2 - Mr Petricevic

[106] For the reasons discussed above I find Mr Petricevic made or concurred in making or published the statement that Bridgecorp had never missed an interest payment or when due a repayment of principal between 30 March 2007 and on or about 29 June 2007 in the Bridgecorp prospectus.

[107] The statement was false in a material particular. Between 30 March 2007 and

29 June 2007 Bridgecorp missed interest payments and, when due, repayments of principal to debenture holders.

The 31 March interest run

[108] During the period of the count, the quarterly interest run of 31 March 2007 became due. It was paid on Monday 2 April. The Crown seek to rely on that as a further missed payment. To do so, the Crown must prove beyond reasonable doubt that Bridgecorp had missed the interest payment due on 31 March. Was the payment on 2 April, the next working day following 31 March, a missed payment? The Crown rely on the reference in the Bridgecorp prospectus which states that interest will be paid:

... quarterly on the last Business Days of March, June, September and

December in each year for the preceding quarter (or part thereof); ...

[109] References to the timing of interest payments in the investment statement are consistent with the statements in the prospectus.

[110] However, the prospectus states:

You are deemed to have notice of, and have the benefit of, and be bound by, the provisions of the Trust Deed.

[111] Clause 2.9(b) of the trust deed provides:

Securities shall be held with the benefit of and subject to the provisions of this Deed, any terms endorsed on the relevant Certificates, the terms contained in the First Schedule, and any further terms forming part of the terms of issue of the Securities, and those provisions and terms or such of

them as are applicable shall be binding upon the Company the Holders and all Persons claiming through them respectively.

[112] The certificates issued to depositors state that interest dates are:

Last day of March, June, September, December.

[113] It also states:

The Secured Debenture Stock comprised in this Certificate (“Stock”) is issued by Bridgecorp Limited (“the Company”). The Stock is constituted and secured by a Trust Deed (“the Trust Deed”) dated 24 December 2003 between the Company, certain subsidiaries of the Company (each as a Charging Subsidiary) and the Covenant Trustee Company (as Trustee for Stock holders) and is issued as Registered Stock with the benefit and subject to the provisions of the Trust Deed and the conditions contained in the current Prospectus;

And later:

Interest on the Principal Amount of the Stock comprised in the certificate is payable quarterly on the dates described below in each year until redemption and is payable on the Maturity Date, at the rate of interest described below, subject to the conditions contained in the current Prospectus. ...

[114] Mr Dickey submitted that the offer documents for Bridgecorp clearly stated the payments would be paid quarterly. While he acknowledged the trust deed stated the security was held with the benefit of and subject to the provisions of the trust deed and any terms endorsed on the certificate, which the investor was deemed to have notice of, he submitted that Schedule 2 of the Securities Regulations 1983 governs the matters that are required to be stated in a registered prospectus and that cl 14 of that Schedule relevantly stipulates that the prospectus must state all terms of the offer and all terms of the securities being offered, not elsewhere set out in the prospectus. Mr Dickey argued that it followed that the reader must have the plain terms of the offer and securities spelt out in the prospectus. He submitted the reference in the prospectus to the quarterly interest being paid on the last business day of March satisfied that requirement.

[115] Mr Cato submitted that the trust deed provisions have priority over the prospectus insofar as the certificate embodies those terms. The obligation to pay therefore arose on 31 March, a Saturday. While the failure to pay on the last

working day might arguably constitute a breach of the prospectus he submitted that the legal obligation to pay interest fell on the date referred to in the certificate and so the payment made on 2 April was not a missed payment.

[116] The Crown alleges criminal offending. The onus is on it to prove that the statement is untrue to the standard of beyond reasonable doubt.17 If there is doubt whether the statement is untrue, which would be the case if arguably the payment was made on due date, then the Crown will not have proved that particular element.

[117] A debt security is defined in s 2(1) of the Securities Act to include debenture stock. The essence of such a debt security is that it creates or acknowledges a debt. In Hickman v Turn & Wave Ltd18 the Court of Appeal noted that in relation to debt security:

a subscription will normally involve depositing or lending money in exchange for the issue of a security evidencing the right to be repaid the money with whatever return is promised.

[118] Securities are defined in the trust deed as:

... debt securities (as defined in the Securities Act) of any nature, ... being either Secured Debenture Stock or Unsecured Notes, and where the context so admits shall be deemed to include the Certificates by which such Securities are evidenced or represented ...