|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Legal History |

EMMA HAWKES[*]

The focus of this work is on late-medieval conceptions of consent in rape and ravishment cases, and, in particular, on whether these understandings changed after the promulgation of the 1382 statute against rape and ravishment. I consider how consent was defined in the courts, what importance was given to the category, and whether the concept was significantly revised in the late-fourteenth century.

The statute of 6 Richard II has traditionally been seen as a ‘fundamental modification’ of the English common law of rape and ravishment, but this evaluation is based purely on the wording of the statute and does not consider how the law was interpreted in the courts.[1] I test the proposition that the 1382 statute represented a significant legal change through an examination of a sample of 132 indictments of rape and ravishment made before itinerate justices in the late-fourteenth century. These records are formulaic, but in the wording of the indictments something of the conceptualisation of consent in rape and ravishment cases can be seen.

The issue of consent in rape and ravishment was a complex one in medieval law. The modern distinction between rape - for the purposes of this article defined as forcible coitus – and ravishment – here defined as abduction which did not necessarily involve forcible coitus – was blurred in medieval common law.[2] Henry Bracton described both as being ‘forcibly ravished against the king’s peace’ (violenter oppressam contra pacem domini regis).[3] The late thirteenth- or early fourteenth-century Mirror of Justice described both abduction and forced coitus as rape.[4] Similar terms were used to describe the crimes in indictments, and both rape and ravishment were covered by the same laws.[5]

The first statute law on the subject of rape and ravishment was passed by Edward I. Chapter 13 of Westminster II (1275) defined ravishment as the abduction of a girl under the age of fourteen whether she consented or not, and as the abduction of a woman over the age of fourteen without her consent. 3 Edward I prohibited ‘ravish[ing or] tak[ing] away by force’ (ravise ne preigne a force) women ‘against [their] will’ (malgre foen).[6] The punishment was downgraded from the rarely enforced castration and blinding of post-Conquest law, and instead a penalty of two years imprisonment and a fine was set. Further, this statute changed the Anglo-Saxon ruling on who had the right to initiate legal proceedings. The abused woman was no longer the sole potential complainant. If a case had not been lodged within forty days, the King had the right to sue.

A decade later, in 1285 this law was revised, and chapter 34 of Westminster II upgraded ravishment to a felony and a capital offence. It was declared that even if the ravished woman later consented, the ravisher was still to be tried. This meant that it was a felony to rape or ravish women ‘even if they consented afterwards’ (ele se assente apres).[7] Punishments for a man who took a nun from her house, even with her consent, were outlined. The statute also introduced an innovation under which a woman who willingly left her husband was debarred from inheritance unless she was reconciled with him and living with him when he died. This was intended to prevent women from willingly leaving with men under the guise of abductions, but the statute also points to some ambivalence about the importance of the women's consent if this agreement came only after the rape or abduction.

This ambivalence was continued in the legislation of 6 Richard II in 1382. Chapter 6 debarred the ravisher from inheritance. It was stated that if a woman was ravished and then consented, she too was cut off from all inheritance, dower or joint-enfeoffment. Both inheritances passed on as if those involved in the abduction were dead. 6 Richard II ‘disabled’ (inhabiles) ‘ravishers’ (raptores) and women who ‘after such rape do consent to such ravishers’ (post huius ... raptum juismodi rap ... consenserint). This concern with consent after the ravishment stemmed from the fact that some crimes were reconciled by marriages between the rapists and their victims, a pattern which made it possible for women to elope in the guise of ravishment with partners their parents did not approve of and for men to abduct women and arrange advantageous marriages.[8] Although rape and ravishment were defined as actions which took place against the will of the women, there was a mistrust for those cases where women agreed to the abduction after the fact.

Most importantly, 6 Richard II authorised the women’s paternal guardians to pursue the cases if the women would not take them to court.[9] This change has been described as completing ‘the extension of legal wrong from the woman to her family’[10] and as reinforcing the ‘prevailing view ... that families had the right to the final decision’.[11] This provision was a significant change to the law. Prior to that point criminal proceedings against rapists and abductors could be brought by the victims or by officials; after 1382 the male kin could also bring actions.

This article considers some of the litigation arising from the legislation in order to examine whether there was a fundamental modification in the ways rape and ravishment cases were brought to the courts. Specifically the focus is on whether men were more involved in bringing indictments after the law was promulgated and whether the way consent was defined changed in rape and ravishment cases. To this end I examined 132 indictments of rape and ravishment brought before itinerate sessions of local justice in the late fourteenth century.

I examined 132 indictments of rape and ravishment brought before sessions of goal delivery, oyer and terminer, trailbaston and King’s Bench in the late fourteenth century to consider how accusations of rape or abduction were made and how consent was defined. I have included all indictments in these records which used verbs such as capio, rapo, violio, asporto, carnaliter cognito or abduco to describe crimes against women.

Some caveats about the records must be made. Significantly more records survive from the period 1382 to 1399 than for the period 1352 to 1381. Improvements in record keeping in reign of Richard II mean that there are 20 surviving rape and ravishment indictments from the period 1352 to 1381 and 112 from the period 1382 to 1399.

The records are indictments only. They are not decisions and the ultimate conclusions in the cases are unknown. Most importantly, the sources follow formulaic legal conventions.[12] The royal judges gathered juries of local men and instructed them to investigate and list breaches of the peace. These representatives of the townships gave the indictments orally in the courts where they were fashioned into formal Latin records by the clerks and the judges. The documents were heavily mediated and had to include certain legal phrases, but some still preserve a degree of individuality.

So, for instance, a 1357-8 indictment said the accused ‘lay with’ Joan Iweyn (Iohanna concubuit). This was a standard formulation but the scribe added that he was ‘a common prowler and malefactor and breaker of the peace’ (et quod est communis noctauigans et communis malefactor et perturbator pacis).[13] Similarly, in 1392 John de Kyrkeby was described as a ‘common prowler’ (noctivague) who peered through various men’s windows with evil intent before breaking into the house of John Brineman and raping his wife Agnes (Agnetem ux'em ipius Johis Brineman ... rapuit).[14] A marginal note was made about the indictment of Robert Traunter in 1362 or 1363. The scribe wrote ‘felony’ next to the accusation (felonia).[15] These variants and notes were not legal requirements. Rather, they can be examined for some insights into how the scribes regarded the crimes they described. It is even possible that they reflect the ways the juries described the accusations to the judges.

Jury records are particularly important in understanding cases of medieval rape and ravishment.[16] These 132 indictments have been read closely, and it is arguable that the phrases rapo, abduco, capio, and asporto describe both rape and ravishment.[17] On the other hand, the phrases violio and carnaliter cognito seem to describe what would today be recognised as rape or forced coitus.[18] These nuances – and other details preserved in the records of the local justices – are examined for understandings of the conceptualisation of rape and ravishment in the fourteenth century.

There are many limitations to these sources but it may be tentatively suggested that these records do not show a clear cut or straightforward change brought about by the 1382 statute.

Comparisons of the men named in the indictments shows similarity between the pre-1382 and post-1382 groups. There were twenty one men named in the twenty pre-1382 indictments. That is to say, there were twenty indictments, one of which named two men. The largest identifiable group of the accused were clerics, possibly because the rape charge was sometimes used to admonish sexually active clerics.[19] In addition to the seven clerics (33.3%), one man was identified as a servant (4.7%) and one as a tailor (4.7%).

These men can be contrasted with the group of 152 men named in the 112 post-1382 indictments. Thirty five of these men were clerics (23.0%), eight were servants (5.2%) and seven were tailors (4.6%). No further details on the men were recorded, but this scant information suggests the composition of the groups of accused rapists and abductors did not vary significantly over time.

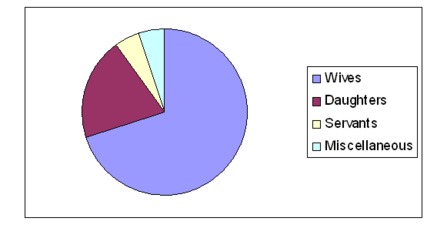

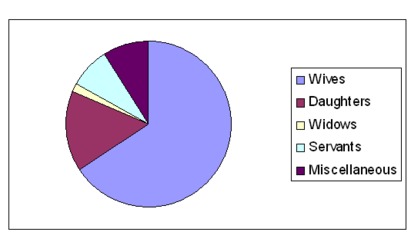

Likewise, very little change over time can be detected in profile of the women described as victims of rape or ravishment. In most legal records of the time women were defined by their marital status – as daughters, wives or widows. In both periods most of the women named in indictments of rape and ravishment were wives.

|

Groups of Women

|

Pre-1382

|

Post-1382

|

|

Wives

|

14 (70%)

|

74 (65.5%)

|

|

Daughters

|

4 (20%)

|

18 (15.9%)

|

|

Widows

|

0 (0%)

|

2 (1.8%)

|

|

Servants

|

1 (5%)

|

9 (8%)

|

|

Miscellaneous

|

1 (5%)

|

10 (8.8%)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total

|

20 (100%)

|

113 (100%)

|

Table One: Marital Status of Women Listed in Rape and Ravishment Indictments 1352-1399[20]

There were 14 wives in the pre-1382 group (70%) and 74 in the post-1382 group (65.5%). Wives were the clear majority in both time periods. Wives were described in the court records using the formula ‘Jane, wife of John Smith’.

In both pre- and post-1392 groups the next largest sets were women described using the formula ‘Jane, daughter of John Smith’. There were 4 daughters in the pre-1382 group (20%) an 18 in the post-1382 group (15.9%).

A small number of women were widows and servants. They were also described in relation to men, as ‘Jane, wife of the late John Smith’ or ‘Jane, servant of John Smith’. Additionally, there were a handful of women whose status can only be inferred from the unusual absence of male relatives in the descriptions of them in the legal records. This small group has been classed as miscellaneous in this analysis.

88 of the 132 indictments listed crimes against wives. Rape and abduction were predominantly presented in the courts as crimes enacted against married women.

The majority of these indictments – 67 of the 88 – also alleged that property had been taken when the wives were raped or abducted. The value ascribed to the stolen property varied from 40 pennies to 20 marks, but, given that it was often described as consisting of cloth of wool and linen, in many cases it seems likely that this property was the women's clothing. So the indictment of Walter Pylmere for the rape of Matilda, the wife of John Smith, noted that he had taken goods, especially one ‘clota’ worth two shillings with a ‘towaylle’ worth sixpence and ‘one parr bedes de ambyr’ worth two shillings.[21] The fact that men owned the stolen property was underlined in records such as the 1387 indictment of Robert, the vicar of Bydford, for the rape of Margaret, the wife of Robert Hugges.

And [the jurors] said that Robert, vicar de Bydford came to the house of Robert Hugges ... and raped Margaret, wife of the said Robert Hugges at Bydford, and took goods of the said Robert, especially cloth and ‘bedes de lambre’ to the value of ten marks.

Et dicunt quod Robertus, vicar de Bydford venit ad domum Robertus Hugges... et rapuit Margaretam ux[or] predicti Robertus, et dicunt quod idem Robertus cepit et abduxit bona et catalla de preficti Robertus, vidilicit pannus et bedes de lambre ad valenciam 10 marks.[22]

The clerk of the Michaelmas session at Berkshire in 1387 was not content to describe the theft of goods along with abduction of the women and inserted comments that the goods were belongings ‘of Thomas’[23] or ‘of Richard’.[24] The 1356 indictment of Thomas Duke included the accusation that he had taken the goods of Robert Hackworthy (bonis et catallis euisdem Robti abduxerunt).[25]

Even more strikingly, one of the few cases not to include this allegation instead bothered to note that William, the servant of John Est, had damaged goods to the value of sixpence when he broke into William de Kele’s house and raped his wife.[26] This suggests that the property crimes were an adjunct to the crimes against women, used to reinforce the accusations.

The theft of property was consistently described with the verbs capio, asporto, abduco while descriptions of actions enacted against women very often used the ambiguous verb rapo. A typical example is the accusation that Henry Orius Wygorm ‘rapuit’ Katerina, the wife of John Henke, and ‘cepit et asportit’ goods to the value of 40 shillings in 1387 in Gloucestershire.[27] It is difficult, if not impossible, to determine whether Katerina was abducted, raped, or left voluntarily with Henry.

On the other hand, it is sometimes possible to infer the nature of the crime with some confidence. Another indictment was brought before the same Gloucestershire session of King's Bench in 1387 which stated that Adam Papu had ‘rapuit’ Elena, the wife of Robert Tyler, and ‘laid with her carnally’ (cum ea carnaliste concubit).[28] He was also accused of ‘taking’ (cepit et asportit) goods, specifically cloth to the value of 40 shillings. These two indictments described similar crimes but the scribe’s additions make it clear that Elena was sexually assaulted.

The consistent use of different verbs to describe the theft of goods and crimes against women suggests a clear distinction was made between crimes of property and crimes against the person. It is, however, difficult to know what the phrase rapo meant. Crimes described with this verb remain ambiguous, but additions were sometimes made which seem to clarify the jurors' understandings of the crimes.

The 132 indictments for rape and ravishment included 22 presentments that defined women in relation to their fathers. This meant that the women were neither married nor widowed.

One of the indictments from the 1392 King’s Bench session was unusually lengthy and specific, perhaps as a reflection of the seriousness of the crime. The jurors indicted a group of men headed by Adam de Faxede the younger of abducting, imprisoning, assaulting, and raping Alice, the daughter and heir of John de Biggynges. They took Alice and tied her up and imprisoned her in the town of Cederugh where they assaulted Alice, who was infirm in her mind (demente in mente). The indictment concluded by stating that Adam de Faxede had carnal intercourse with her (carnalite concubi), and all her relatives and friends had been afraid that Alice would die in his custody, and that the houses and barns of her friends were burned and their servants were killed.[29]

In this case the jurors highlighted the heinousness of the crimes of Adam de Faxede and his followers, and the record included much damning detail. The jurors did not, however, accuse the miscreants of deflowering Alice de Biggynges. Although the allegation that Alice had been raped as a virgin could plausibly have been made in this case – since she was neither married nor widowed – the indictment did not note this.

Indeed, only one of the indictments concerned with the rape of never-married women noted that the woman had been a virgin. In 1393 John de Stanton, chaplain, was indicted for ‘feloniously raping’ Isabella, daughter of Henry Tailor of Whitewell, ‘of her virginity’ (de virginitate sua ... felon[ice] rapuit).[30] The accusation was probably intended to underscore the severity of his crime, but was not repeated elsewhere in the records.

The silence of the records on this issue is striking, since the theory of rape law - in both the common and canon law traditions - emphasised the special status of virgins and the heinousness of raping them. These legal traditions drew on Isidore of Seville's sixth-century definition of rape which presented rape as a form of corruption which was, of course, particularly defiling for virgins. ‘Rape proper is unlawful coitus, which is said to corrupt.’ (Raptus proprie est inlicitus coitus, a conrumpendo dictus.)[31] Canon law decreed that anyone who took a virgin, or helped another to do so, was anathema.[32] The only example of a rape case included in the twelfth-century common law text, Novae Narrationes, was of the ‘rape of [a woman's] maidenhead’ (de rape de soun pucellage).[33] The thirteenth-century legal theorist Bracton stated that the death penalty had previously been in place for the rape of virgins, and that, although penalties in his time were more lenient, the rape of virgins continued to merit the harshest punishment.[34]

Virginity was, of course, a favoured state in medieval thought.[35] The Blessed Virgin Mary was the summit of womanhood, and the Church Fathers praised virginity. The horror of the rape of virgins was expounded on in the hagiography of virgin martyrs who evaded being raped by pagan lords.[36] The struggles and suffering of these women were recorded in Latin tracts such as the Golden Legends, translated into English, and doubtless recalled with particular devotion in those churches dedicated to these saints.[37] This abhorrence for the rape of virgins was reflected in the severe penalties for this crime outlined in legal theory.

In this context it is difficult to see why so few indictments of the rape of daughters noted they had been deprived of their virginity. There was no legal obligation to mention whether or not the victims of rape had been deflowered, but the accusation could plausibly have been made for most never-married women and would presumably have strengthened the indictments. Given the degree of variation which was shown in the indictments and the extent to which the available tropes of rape and ravishment were manipulated in these sources, it is striking that only a single indictment made this accusation. There is a significant gap between legal theory and the apparent practices of late-medieval courts.

The 132 indictments for rape also include ten which named the victims as serving women. While it is impossible to definitively distinguish the crimes the juries had in mind, the language of the indictments suggests that many of the crimes described were abductions of valued workers.

For instance, John Derwent was accused of abducting Alice, the servant of Sir William de Belesby ‘out of his service’ (ex servius dicti’ Willi’) and described this as a great loss, which suggests a focus on her economic value.[38] Some indictments – such as a 1395 or 1396 Duchy of Lancaster indictment concerning the abduction of Julien, servant of Robert Rady – seem to note that the servants had entered into the service of the abductors.[39] These allegations of the abduction of servants can probably be viewed as part of the post-plague labour crisis. They were included in the rape indictments because the laws of abduction and rape were so closely intertwined in the middle ages, but it seems unlikely that the servants were taken primarily for sexual reasons.

Indeed, these records are comparable to the handful of late fourteenth-century indictments which described the ravishment of men, usually male servants.[40] For instance, in the 1380s John de Grunne took Thomas Isborne, servant,[41] and in 1389 John Holt took Thomas, servant of Richard Howe.[42] These records have been excluded from the cohort examined in this article though those naming serving women have been included in the interests of consistency.

On the other hand, a handful of these indictments unequivocally described the forcible rape of female servants. In Lindsey in the 1380s Robert, a servant of Master Henry, rector, was indicted for the rape of Alice, a former servant of Robert Dyon.

[The jurors] said that Robert, the servant of Master Henry, rector of the church at Alesby ... took Alice ... and cut her with his knife, raped her and knew her carnally against her will.

[E]t dicunt quod Robertus, servient Master Henry, rector de eccl[esia] de Alesby... secuit ea cu[m] cultello suo... et ea ibm rapui[t] et cognit carnalit[e] con[tra] voluntat[e] sua.[43]

In an unusual case in 1395 Alan Baroun, miller, was indicted for seizing Joan, a servant of Laurence atte Wode, overwhelming her and trying unsuccessfully to rape her (cepit Joham s[er]viente [L]auren atte [W]ode et eam oppressit et cu[m] ea concubit voluit tamen non potuit).[44] This incident was not included in the cohort examined here as it was technically a record of an assault, but it clearly had a sexual element to it.

These indictments describing forced coitus stand almost alone. There were very few indictments which unequivocally described sexual assault, and none at all which stated that masters had raped their own servants despite the seeming probability of such activity. It may be that the absence of serving women from the records of judicial sessions stems from their absence in the laws concerned with rape and ravishment. Serving women were not listed in the laws of 1275, 1285 or 1382, except generally in the category of ‘other women’ (aliarumque mulierum).[45] Indeed, in the following century 3 Henry VII specifically exempted bond women, very likely to be serving women, from the protection of rape laws. The 1487 legislation tightened the laws concerned with rape and ravishment, but included the provision that ‘this act extend not to any person taking any woman, only claiming her as his ... bond-woman’.[46] In this climate, it is unsurprising that the rape and ravishment of serving women was overlooked by the law.

The indictments also listed a handful of women who were not described in relation to their male relatives. In 1392 Robert Manfeld, a cleric, was indicted for the rape of a woman described simply by her name, Agnes Salmayn.[47] In the same year John de Kyrkeby, the vicar of Longtoft, was indicted for raping Margaret Wakefield and was described as a ‘common malefactor and raper of women’ (et q[uo]d est co’is malefacter et rapter mulieru’).[48] These women were presumably single.

Other victims were even more obscurely described or actually unknown to the jurors. There is a single record describing the rape and murder of an unknown, underage victim. At the 1392 King’s Bench session in Yorkshire, the jury from Doncaster asserted that:

Robert Ripman, formerly of Thornton, met a girl whose name is unknown to the jurors at Thornton and cut her secret parts with a knife and raped her and she was under nine years of age. And jurors say that because of this assault the girl died within three days.

[O]bviavit quid[a]m puelle cuius nomeri jur[es] p[re]d[i]cti igorant apud Thornton et ib[ida]m d[i]c[ta]m puella cum quod[e]m cultello in secretis suis vulnus et ipam Johem rapiend et q[uo]d d[i]c[t]a puell[a] invenis fuit et int[ra] etate ix annor[um] et sic ipam Joham rapuit et ult[er]ius dic[t] q[uo]d[a]m jurur dic q[uo]d causa cuius injurius d[i]c[t]a puella intra tres dies p[ro]x[ime] seu moriebat.[49]

Other women belonged to very specific subgroups, such as the two nuns who left the abbey of Elmestarre with William Cross in 1394. William Cross, the parson of Shryngton in Buckinghamshire, was indicted for abducting Elizabeth Camoys and Alice Russheby. He was also accused of stealing a book of accounts and other deeds from the abbey and of assaulting William Edefyn.[50]

The tendency for most women to defined in relation to their male relatives is consistent in medieval legal records. A study of King's Bench cases between 1422 and 1442 found that only a tiny proportion of litigants used categories such as ‘gentlewoman’ or ‘spinster’.[51] Indeed, after the introduction of the Statute of Additions in 1413 some terms used to define women could be categorised as unacceptable to the courts. When Joan Botiller ‘sengilwoman’ was indicted before in the justices of the peace in Cambridge in 1437 it was decided that the description was insufficient.[52] The legal system was simply not set up in such a way that women could be presented autonomously. It is unsurprising that only a tiny number of the women named in these 132 fourteenth-century indictments were not described in relation to their male relatives.

It is striking that the introduction of the new law in 1382 did not alter the profile of the women named in the indictments. The majority continued to be married women, with smaller numbers of servants and daughters. Prior to 1382 married women made up 70% of those named in indictments; after 1382 this was 65.5%, still a clear predominance.

Figure One: Women named in indictments pre-1382 (n=20)

Figure Two: Women named in indictments post-1382 (n=113)

There was no increase in the proportion of women described as daughters despite the introduction of the law enabling fathers to bring indictments in cases where daughters had eloped. Daughters made up 4 of the 20 women in the pre-1382 group (20%) and 19 of the 119 women in the post-1382 group (15.9%). There is no evidence that fathers were using their newly extended right to litigate in the case of elopements or forced marriages which the women became reconciled to. Men do not seem to have taken up the rights transferred to them by the 1382 statute.

If there was no change in the profile of the people named in the indictments, was there a change in the ways the indictments defined consent? Did the intentions and perceptions of the men - the fathers and husbands - become more important in the records after 1382?

There is some evidence that after 1382 rape and ravishment were sometimes defined as events which took place against the will of the male kin. There are records which prioritise the will of the husbands, and it is striking that these exist only after the passing of 6 Richard II.

This would suggest that the 1382 statute may have influenced a move to defining rape as an event which took place against the will of the husband or male guardian. So, for instance, in 1387 Master Richard Topclyf, cleric, was indicted for raping Diana wife of Robert at Grene ‘against the will of the said Robert’ (contra voluntate ipius Robti’).[53] Between 1381 and 1388 there was an indictment against John Godeson of Malberthorpe which stated that he broke into the house of Gilbert Prenton and ‘raped his wife Matilda, contrary to Gilbert's will’ (Matill uxm contra voluntat' ipius Gilbt violanit). The indictment added that he injured Gilbert against the peace (ipm Gilbtm iniurat ad occadenet con’ pace).[54] In 1384 in Gloucestershire there was an indictment against Adam Papu, chaplain, in which he was accused of raping Elena wife of Robert Tylere at Aulton and of taking goods ‘against the King's peace and against the will of the said Robert her husband’ (contra pacem Regis et contra voluntate p’dicte Robti viri sui).[55] This choice of phrasing is revealing. It suggests a conception of rape and ravishment as a crime against the male guardian, in this case the husband.

The handful of records which explicitly defined rape and ravishment as events taking place against the will of the husbands only survive from after 1382. On the other hand, there are so few records for the 30 years before 1382 that it might not be significant that there are no records of this sort surviving from prior to the passing of the statute.

Sometimes rape and ravishment were defined in terms of the will of the women. This was particularly clear in cases where single women were the victims. For example, the 1389 indictment of Richard Lynthe and William at Well for the rape of Agnes, widow of John at Marsh, was described as being ‘against her will’ (contra voluntatem sua).[56] Records of Duchy of Lancaster for the period 1381-1388 show that Robert, servant of the rector of the church at Alesby, was indicted of taking Alice, who had been servant of Robert Dyon of Larceby, and ‘cutting her with his knife, raping her and knowing her carnally against her will’ (secuit ea cum cultello suo ... et ea ibm rapuit et cognent carnalit[er] con’ voluntat’ sua).[57] The 1392 indictment of the cleric Robert Manfeld was described in a similar way. He was accused of raping Agnes Salmayn and carnally knowing her against her will (Agnetem Salmayn ... felonice rapuit et cum ea carnalite concubit contr’ suis voluntatem).[58] In 1389 John Barker was accused of two separate crimes - against Alice Percyvall and Maria, the daughter of John Saxten – and both crimes were said to be against their will (contra voluntatem sua).[59]

In these cases the consent of the women was prioritised in the records of the courts. The same emphasis on female consent can be seen before the introduction of Richard II’s legislation. Thomas Jankyns was indicted for the rape of Edith Winterbourn in 1357 or 1358. The indictment said that he ‘feloniously raped and ravished a certain Edith Winterbourn ... and lay with her against her will’ (quedam Editham Wynterbourn felonice rapuit et abduxit .... et cum ea concubuit contra voluntatem suam).[60]

The issue of women’s consent and will was also central in an indictment of assault brought in the Duchy of Lancaster in the reign of Richard II. In 1388 John de Stokbrig of Burowe was accused of having assaulted Joanne de Cotes of Bondby and having threatened to rape her ‘against her will’ (rapuisse volu’ cont’ voluntat’).[61] This was an assault case but the threat of rape was also recorded. The legal record centred her consent as the issue which defined potential rape.

It should be noted, however, that once again the issue of consent was important in a case which featured a single woman. There are no records naming married women which defined rape or ravishment in terms of their consent. Women's consent was only ever foregrounded in indictments involving single women – a distinct minority of legal actions.

This close examination of the indictments of rape and abduction brought in the period 1352 to 1399 suggests that consent in rape or ravishment was sometimes defined in terms of what male guardians wanted, but that in cases where the victims were single women rape and ravishment was sometimes defined in terms of their consent.

The records suggest that the impact of the 1382 law was subtle. It is not directly or quantitatively apparent in the court records. While the statute nominally increased the role of fathers and husbands, there is no evidence of an increased role in litigation. There are no surviving records in which fathers took action on behalf of daughters who had later consented to rape.

However, there may have been a slight increase in the significance of the consent of husbands after 1382 I have found no records which said rape took place against will of husband from before 1382 and they begin to be recorded after that date. Adding that a rape or ravishment was ‘against the will of the husband’ was an unnecessary flourish, not a requirement of the law. The use of this phrase by some clerks after 1382 suggests a move to conceptualising rape and ravishment in terms of the consent of these men.

While it is possible that this is a result of the anomalies in the survival of the records, there is some evidence showing 1382 law influenced judgments about rape and ravishment cases. For example, in 1422 Justice John Hals affirmed that the rape statute of 1382 allowed a husband to bring an action of rape on behalf of his wife, saying ‘the husband should have power to have him convict of life and of member’ (le baron eit poiar de veta et de membro ipsum conuincendi).[62]

This analysis of case law shows that the rape and ravishment law of 1382 had an indirect but significant impact. It appears to have further prioritised male concerns in the definition of rape and ravishment although it had little effect on the profile of those bringing legal action.

[*] BA (Hons in English and History) (UWA) PhD (Hist) (UWA). I wish to acknowledge the assistance of a grant from Griffith University which provided funding for the archival research. I would like to thank Dr Jenny Bailey-Smith for her assistance.

[1] J B Post, ‘Sir Thomas West and the Statute of Rapes, 1382’ (1980) 53 Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research 25.

[2] Philippa Maddern, Violence and Social Order: East Anglia, 1422-1442 (1992) 99-103.

[3] Henry Bracton, De Legibus et Consuetudinibus Angliae: On the Laws and Customs of England, http://bracton.law.cornell.edu/bracton/Common/index.html.

[4] ‘Rape is committed in two manners: ... For stuprum is one thing ... and rape yet another, if we speak correctly and differentiate sins of which some are greater than others. Stuprum is the felonious taking away of a woman's maidenhood ... but rape is strictly speaking the abduction of a woman with intent to marry her.’ ‘Rap se fet en ij maneres .... Car j. est stupre .... et autre rap, pur proprement parler e le pecchie destincter, dunt li j. pecche est greignur de lautre. Stupre est a despuceler femme felounessement. ... Rap est proprement alopement de femme pur desir del marriage.’ William Joseph Whittaker (ed), The Mirror of Justice (1895) 28-9.

[5] Christopher Cannon, ‘Raptus in the Chaumpaigne Release and a Newly Discovered Document concerning the Life of Geoffrey Chaucer’ (1993) 68 Speculum 74-94.

[6] Westminster I, 3 Edward I, c.13.

[7] Westminster II, 13 Edward I, Statute I, c.34.

[8] J B Post, ‘Ravishment of Women and the Statute of Westminster’ in J H Baker (ed), Legal Records and the Historian: Papers Presented to the Cambridge Legal History Conference, 7-10 July 1975, and in Lincoln’s Inn Old Hall on 3 July 1974 (1978) 158-160; Emma Hawkes, ‘“She was Ravished against her Will, What so ever she Say”: Female Consent in Rape and Ravishment in late-medieval England’ (1995) 1.1 Limina 49-50.

[9] 6 Richard II, Statute I, c. 6.

[10] Post, above n 1, 26.

[11] Barbara Toner, The Facts of Rape (1977) 94.

[12] For instance, the claim of detention of deeds could be used to bring a bill to Chancery rather than a common law court, and it was often used as a legal fiction for this purpose. Similarly, the phrase vi et armis had to be used if claims were to be taken to King’s Bench. Alan Harding, The Law Courts of Medieval England (1973) 106; S F C Milsom, Historical Foundations of Common Law (1975) 246.

[13] Somerset, 31 Edward III, Ancient Indictments 104, 1357-1358 in Bertha Haven Putnam (ed), Proceedings before the Justices of the Peace in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries (1938) 190.

[14] KB 9/144, f 27, 16 Richard II, Michaelmas 1392.

[15] Assize Roll 812, Staffordshire, 35-37 Edward III, 1361-1363, in Proceedings before the Justices of the Peace in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries (1938) 276.

[16] Sue Sheridan Walker, ‘Common Law Juries and Feudal Marriage Customs in Medieval England: The Pleas of Ravishment’ (1984) University of Illinois Law Review 708.

[17] Sue Sheridan Walker, ‘Wrongdoing and Compensation: The Pleas of Wardship in Thirteenth and Fourteenth Century England’ (1988) 9.3 Journal of Legal History 270.

[18] Cannon, above n 5, 82.

[19] Maddern, above n 2, 102-3.

[20] There were 133 women named in the 132 indictments as William Cross was accused of abducting two nuns, Elizabeth Camoys and Alice Russheby, from the abbey of Elmestarre. KB 9/172/1, f 9, 18 Richard II, Michaelmas 1394.

[21] KB 9/32, f 11 – Westbury, 11 Richard II, Michaelmas 1387.

[22] JUST 1/977, f19, 10 Richard II, Trinity 1387.

[23] KB 9/1054, f 3, 11 Richard II, Michaelmas 1387.

[24] KB 9/1054, f 3, 11 Richard II, Michaelmas 1387.

[25] JUST 1/197, Special Oyer et Terminer Proceedings, Devon 30-31 Edward III, 1356-1357.

[26] KB 9/63, f 5, 11 Richard III, 1381-1388.

[27] KB 9/32, f 6 – Gloucestershire, 11 Richard II, Michaelmas 1387.

[28] KB 9/32, f 6 – Gloucestershire, 11 Richard II, Michaelmas 1387.

[29] KB 9/144, f 35, 16 Richard II, Michaelmas 1392.

[30] KB 9/989, ff1-4 (stitched together), 16 Richard II, Trinity 1393.

[31] Isidore of Seville, Isidori Hispalensis Episcopi: Etymologiarum sive Originum, W M Lindsay (ed), Book 1 (c.1911) 5.26.

[32] Chapter 11, ‘If anyone seizes a virgin, unless he has espoused her, or forcibly takes her for his wife, let him be anathema along with all his supporters.’ Pope Gregory, Grat. C. 36, q. 2 c. 5. John Gilchrist (ed), The Collection in Seventy Four Titles: A Canon Law Manual of the Gregorian Revolution (1980) 230.

[33] Elsie Shanks (ed), Novae Narrationes (1963) 341-4.

[34] ‘In times past the defilers of virginity and chastity [suffered capital punishment], as did their abettors, since such men were not free of the crime of killing, especially since virginity and chastity cannot be restored, and since virgins and widows as well as nuns are dedicated to God [and] their defilement is committed not only to the hurt of mankind, but indeed, in scorn of Almighty God Himself, and [since] without punishment of this kind such infamy may not be put down. But in modern times the practice is otherwise and for the defilement of a virgin they lose their members, as aforesaid, and their abettors suffer severe corporal punishment but without loss of life or members.’ ‘Modernis tamen temporibus aliter observatur, quod pro corruptione virginis amittuntur membra ut prædictum est, et de aliis sequitur gravis p|na corporalis, sed tamen sine amissione vitæ vel membrorum. Et cum virgines et viduæ necnon sanctimoniales deo sint dedicatæ, corruptio earum non solum ad iniuriam hominum, verum etiam ad ipsius dei omnipotentis irreverentiam committitur, et sine vindicta talis non quiescat infamia.’ Henry Bracton, De Legibus et Consuetudinibus Angliae: On the Laws and Customs of England, http://bracton.law.cornell.edu/bracton/Common/index.html.

[35] John Bugge, Virginitas: An Essay on the History of a Medieval Ideal, International Archive of the History of Ideas (1975); Marina Warner, Alone of All her Sex: the Myth and Cult of the Virgin Mary (1983).

[36] Corinne Saunders, Rape and Ravishment in the Literature of Medieval England (2001).

[37] There are over 170 medieval bells dedicated to St Katherine still in existence, and there were 62 medieval English churches dedicated to her. At the same time there were over 200 churches dedicated to St Margaret in medieval England. David Hugh Farmer (ed), The Oxford Dictionary of Saints (1978) 69-70, 260-1.

[38] KB 9/63, 4-11 Richard II, 1381-1388.

[39] KB 9/63, f 48, 18-19 Richard II, 1395-1396.

[40] The fourteen accusations naming male victims were: John Boteler and others took Randolph, the son and heir of William de Stanfield – KB 9/144, f 53, 16 Richard II, Michaelmas 1392; Henry Boorn and Simon Page of London took two servants of John More, glazier – KB 9/173/1, f 4, 17 Richard II, Hilary 1394; John de Bateford and others took Thomas Sampson – KB 9 166/1, item 16, 5 Richard II, 1381; John, son of John of Lincoln took a servant of Thomas Maynes – KB 9/63, 4-11 Richard II, 1381-1388; John Holt took Thomas, servant of Richard Howe – KB 9/32, 11 Richard II, Michaelmas 1389; Richard Dyk and others took John Brig and Richard Brig - KB 9/181, 17 Richard II, Easter 1394; Roger Smith and John FitzJohn took a servant of Thomas Mayne – KB 9/63, 4-11 Richard II, 1381-1388; Joan Savage took Adam, a servant of William Nicolness – KB 9/63, 4-11 Richard II, 1381-1388; Robert de Coms took Thomas None – KB 9/63, 4-11 Richard II, 1381-1388; John de Grunne took Thomas Isborne, servant – KB 9/63, 4-11 Richard II, 1381-1388; John Ward and John Skirnoy took Roger Calf and John Fichet, servants of the abbot of Nenhouse – KB 9/63, 4-11 Richard II, 1381-1388; Sibia Whitebred took John Whitebred, servant of Simon Edwards – KB 9/63, 18-19 Richard II, 1395-1396; Adam Pulter and others took Reginald de Ecles, justice of the king – KB 9/166/1, f 119, 5 Richard II, 1381; John de Shipton and others took Thomas de Kent, William Symson, William Meggessonwarde and Hugo de Skelton, tenants of the Abbey of St Mary’s and also sixteen oxen – KB 9/144, 16 Richard II, Michaelmas 1392.

[41] KB 9/63, 4-11 Richard II, 1381-1388.

[42] KB 9/32, 11 Richard II, Michaelmas 1389.

[43] KB 9/63 Duchy of Lancaster – Lindsey, 4-11 Richard II, 1381 – 1388.

[44] KB 9/173, f 5 – Kent, 18 Richard II, Easter 1395.

[45] 6 Richard II, c 6.

[46] 3 Henry VII, c 2.

[47] KB 9/144, 16 Richard II, Michaelmas 1392.

[48] KB 9/144, ff 45, 49, 16 Richard II, Michaelmas 1392.

[49] KB 9/144, f 10 – Doncaster, 16 Richard II, Michaelmas 1392.

[50] KB 9/172/1, f 9, 18 Richard II, Michaelmas 1394.

[51] Maddern, above n 2, 41.

[52] JUST 3/7/4, m 3r.

[53] JUST 1/977, 10 Richard II, Trinity 1387.

[54] KB 9/63, Duchy of Lancaster, Lindsey, 4-11 Richard II, 1381-1388.

[55] KB 9/32, f 7, 11 Richard II, Michaelmas 1387.

[56] KB 9/5, 13 Richard II, Michaelmas 1389.

[57] KB 9/63 Duchy of Lancaster, Lindsey, 4-11 Richard II, 1381-1388.

[58] KB 9/144, 16 Richard II, Michaelmas 1392.

[59] KB 9/5, f 17, 13 Richard II, Michaelmas 1389; KB 9/5, f 17, 13 Richard II, Michaelmas 1389.

[60] Ancient Indictments 104, Somerset, 31 Edward III, 1357-1358, in Proceedings before the Justices of the Peace in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries (1938) 188.

[61] KB 9/63, Duchy of Lancaster – Lindsey, 4-11 Richard II, 1381-1388.

[62] Athern v Bigg (1422). C H Williams (ed), Year Books of Henry VI, 1 Henry VI (1422) (1933) 1.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/AULegHist/2007/6.html