Federal Law Review

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Federal Law Review |

|

Gary Edmond[*]

This article examines the conduct of empirical legal research and its relationship to law reform. Through a detailed analysis of the largest survey of State and federal judges conducted in Australia it explores some of the limits to empirical investigation, particularly the tendency to rely primarily on judicial perspectives as the basis for law reform. Focusing upon empirical legal research on the subject of expert evidence the article initially examines research methodologies, then extends the analysis to consider the correspondence between the collection, interpretation and presentation of empirical data and recommendations for legal change. This involves an assessment of a broad range of methodological and theoretical issues with implications extending well beyond the particular survey. Last, the empirical research on expert evidence will be evaluated using the principal reform proposal suggested by the investigators. This exercise will provide an indication of methodological problems which beset the survey and demonstrate practical limitations with the particular approach to expertise.[1]

Australian Judicial Perspectives on Expert Evidence: An Empirical Study and Australian Magistrates' Perspectives on Expert Evidence: A Comparative Study report the results of empirical studies of judicial and magistrates' attitudes to experts and expert evidence in Australian legal settings.[2] In the ensuing analysis the principal findings from Australian Judicial Perspectives on Expert Evidence (hereafter 'Perspectives' or the 'Report') will be reviewed. In exposing problematic assumptions and questionable methodological practices associated with the research project this article aims to re-assess several of the principal, and widely endorsed, findings. Specifically, it questions the empirical basis for the following claims:

1. That bias is the most serious problem with expert evidence.

2. That problems with expert evidence warrant the reform of existing rules and procedures.

3. That judicial officers (and the public) are in favour of immediate and/or fundamental law reform.

4. That the proposed Declaration (or similar reforms) will relieve problems attributed to expert bias or partisanship.

This section provides a succinct overview of the survey, its origins, findings and recommendations.

The survey of Australian judges emerged from concern with the limited amount of information about the views of judges on the role played by expertise in Australian legal systems.[3] Conducted under the auspices of the Australian Institute of Judicial Administration (AIJA), the study was intended to remedy this deficiency.

Perspectives focuses on the opinions of Australian judges (and magistrates):

Judges are in a unique position to contribute an informed perspective on the way in which expert witnesses function within the adversary system. However, until now comparatively little has been known about the views of judges in Australia or internationally in relation to expert evidence and expert witnesses. [4]

All other perspectives are marginalised.[5]

Prior to distribution the investigators developed a prototype survey and conducted a pilot study. A revised instrument was distributed by mail to all Australian judges, with the AIJA formally endorsing the project through the provision of a covering-letter. The authors of the Report are a barrister (Freckelton), an academic psychologist (Reddy) and a legal academic (Selby). Their combination facilitates, in conjunction with the dearth of extant materials, the presentation of the results as a timely and comprehensive interdisciplinary study.[6]

The Report presents the results of the survey of Australian judges. Slightly more than 50 per cent of Australian judges (51%, n=478) responded.[7] The investigators expressed a primary interest in judges with trial experience as judges. This, they suggest, raises the response rate closer to 60 per cent. The questionnaire adopts the form of a multiple-choice survey with some space allocated for written comments. Several questions requested elaboration or greater specificity.[8] The survey was anonymous and the quantified data are presented as the empirical basis for the findings in the Report.

According to the Report, the 'three key outcomes' are: 'a recognition by judges of the value of clarity of explanation, a quest for reliability in both opinions and their proponents, and a desire that the courtroom be a truly effective accountability forum'.[9] These results are consistent with the authors' espoused desire to improve the standard of expert evidence appearing in courts. Having affirmed the (increasing) importance of expertise in modern litigation the Report identifies a range of serious problems disrupting contemporary practice. Chief among these problems is 'bias': 'witness partisanship [is] the issue that most troubles Australian judges in relation to expert evidence'.[10] Though, complexity, comprehension, communication, advocacy and the lay jury, to varying degrees, also warrant attention.

The prominence of problems with expert evidence, particularly problems attributed to bias, lead the authors to recommend immediate law reform.

On the basis of the survey results Perspectives advances law reform. Changing the 'culture of partiality' among experts and eliminating bias are at the forefront of the recommendations.

Having empirically established the existence of a range of serious problems, the Report is perhaps disappointing in the number, variety and originality of recommendations. Confronted with partisan expert culture, serious communication and comprehension difficulties, routine exposure to complex evidence and a lack of preparation and skill by advocates, the actual proposals might be considered quite modest in their compass. They include: requiring experts to make a formal declaration—substantially similar to a range of recent reforms adapted from the English modifications to civil procedure by several Australian jurisdictions; some further (informal) mechanisms for training lawyers and experts; and greater recourse to audiovisual technologies. The expert Declaration, however, is the only reform proposal elaborated in any detail. (The Declaration is reproduced in Section 6.A.i and discussed in Section 7, below).

The remainder of this article is dedicated to analysis. The design and interpretation of the survey, the existence and extent of problems, assumptions about the nature of expertise as well as the need and value of the proposed reforms for policy and practice will all be examined in detail.

Presented as an impartial empirical account of judicial attitudes, Perspectives purports to have identified the major contemporary problems with expert evidence in Australia. The Report leaves the reader in little doubt that expert bias (or partisanship) is the most significant problem.

This section examines the construction of 'bias' as an empirical legal problem. This involves an assessment of whether the survey results support the contention that bias is the most serious problem with expert evidence and whether bias should even be characterised as a serious legal problem.[11]

Unremarkably, the vast majority of surveyed judges appear to have considered expert evidence useful for fact-finding. Most respondents (Question 2.1) indicated that experts were useful 'often' (69%) or 'always' (13%).[12] Having established the (potential) utility of expert evidence, the survey immediately turns to inquire about a range of problems conventionally associated with experts and the provision of expert evidence. These 'problems' include: bias; use of language that is difficult to understand; failure to stay within parameters of expertise; non-responsiveness to questions; failure to prove the bases of opinions; cross-examination not making the expert accountable and the complexity of evidence (Questions 2.2 and 2.4).[13] Unfortunately, the design of the survey precludes a straightforward or methodologically persuasive evaluation of the relative significance of these purportedly serious problems.

Of all the problems, however, 'bias' is consistently presented as the most serious and detrimental.[14] For example: 'The answers … confirm witness partisanship as the issue that most troubles Australian judges in relation to expert evidence'.[15] And,

[m]any judges who responded to the survey identified partisanship or bias on the part of expert witnesses as an issue about which they were concerned and in respect of which they thought that there needed to be change. They did so directly in their answers to questions and also in their comments about experts' lack of objectivity. Many raised the issue more than once in their responses. The picture painted by a significant cross-section of respondents was one of worry about an unacceptable culture in sectors of disciplines providing report-writers and witnesses to the courts. The culture, they asserted, does not adequately value and put into practice independence, objectivity or transparency of opinions.[16]

These extracts, and others like them, provide a sense of the recurring significance accorded to bias, partisanship and a lack of objectivity among experts in the Report. Yet, notwithstanding these claims, the survey reveals little about the relative seriousness of bias or its relations with the other problems attributed to the use of expertise.

One of the major difficulties with the authors' interpretation of the survey stems from the inability to meaningfully compare or assess data elicited from different questions. This is a consequence of survey design. Because many of the issues are treated discretely it is difficult to ascertain their relative significance, their interdependence or whether, when weighed against other features of the adversarial system, they should be regarded as (serious) problems. Consequently, notwithstanding the characterisation of bias or partisanship as the most serious problem, several problems might be understood to compete for the status of the most serious problem associated with the admission, presentation or assessment of expert evidence.

The disparate treatment of problems is reflected in the following array of questions:

Q2.2 Have you encountered any of the following problems with expert evidence?

Q2.3 What is the single most serious problem you have encountered with expert evidence?

Q2.4 Have you encountered evidence from experts which you were not able to evaluate adequately because of its complexity?

Q2.11 From the following list please circle the one which you consider to be the single most persuasive factor when an expert is giving oral evidence.

Q3.1 How effectively do most advocates appearing before you elicit oral evidence-in-chief from expert witnesses? (and Question 3.3)

Q3.7 Have you experienced difficulty in evaluating the opinions expressed by one expert as against those expressed by another? (and Question 3.9)

Q5.7 Should matters involving complex and conflicting medical evidence be withdrawn from juries and be determined by judges alone or by some other means? (and Questions 5.5 and 5.6)

Q6.4 Is the courtroom a forum in which the reliability of expert theories and techniques is adequately evaluated?

Q6.7 Do the same expert witnesses appear regularly before you for the same side in litigation?

Q6.8 Have you encountered partisanship in expert witnesses called to give evidence before you?

Q6.9 If you answered (a) to the previous question, is this a significant problem for the quality of fact-finding in your court?

Accepting that there is some overlap in their treatment, especially in the answers included with Questions 2.2 and 2.3, many of the questions treat the issues — prefigured as problems — in isolation.[17]

Because of the way in which these (and other) questions have been posed they are practically incommensurable. We have few means of comparing their relative seriousness. There is no discussion of the relationship between categories or how conflicts between experts, or diversity of opinion or complexity might influence perceptions of bias. Is, for example, bias a more serious problem than complexity? What, if any, are the relations between bias, complexity and the clarity of presentation (Questions 2.2, 2.3, 2.4, 2.11 and 6.8)? More fundamentally, how are judges who experience comprehension or communication difficulties able to ascertain bias?

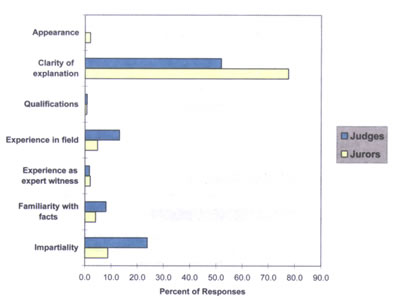

Contrasting claims about bias from Question 2.3 (reproduced in 3.B.i, below) with other questions and findings in the Report introduces a series of additional analytical limitations. Two examples will serve as illustrations. First, even though the judges seem to have selected 'bias' as 'the most serious problem', bias appears to have been considered less significant in evaluating the persuasiveness of oral expert evidence than the 'clarity of explanation'.[18] Where respondents were asked (Question 2.2(ii)) if they had ever encountered experts using oral or written language that was 'difficult to understand' the vast majority indicated that they had either 'occasionally' (73%) or 'often' (14%).[19] When it came to providing an indication of the factor which was most persuasive when an expert presents oral evidence, half (50%) of the judges chose 'clarity of explanation'. Less than one quarter (23%) of the judges, responding to the same question, selected 'impartiality' (Question 2.11).[20] So, while bias may be perceived as a kind of problem, to some extent it may be anticipated and its effects managed — perhaps informally by judges.[21] It is also possible that some of the issues presented as problems are, notwithstanding the nomenclature (imposed by the survey instrument), not particularly significant to judges in their practice.[22]

Such an interpretation might help to explain the identification of 'bias' as the 'most serious single problem' in Question 2.3 when contrasted with the results of Questions 6.8 and 6.9. In these questions respondents were asked if they had 'encountered partisanship in expert witnesses called to give evidence'. The vast majority of respondents (85%) indicated that they had. Interestingly, in a leading follow-up question, only two fifths (40%) listed such partisanship as a 'significant problem' (Questions 6.8 and 6.9).[23] Just to restate this result, a majority of judges did not consider partisanship to be a significant problem for fact-finding.[24]

In the face of these apparent inconsistencies the authors of Perspectives have generally preferred a compartmentalised interpretation of their data. The Report emphasises particular questions and results in isolation. It makes few attempts to address ambiguities or apparent contradictions. The absence of a systematic attempt to integrate the findings through the provision of more standardised answers or terminology leaves us with a motley assortment of potentially ambiguous, and at times contradictory, results. The results are not unequivocal in their support for the existence of serious and widespread problems with expert evidence. The seriousness of bias and partisanship seem to vary across the survey. The results and analysis of questions 2.2 and 2.3 are not easily reconciled with the data from Questions 2.11, 6.8 and 6.9. The failure to distinguish between different types of bias (advertent or inadvertent), or clearly define bias, partisanship and objectivity only serve to increase the ambiguity, impeding the ability to determine the existence or relative seriousness of any particular problem.[25]

There are, however, other difficulties with claims about bias.

This subsection examines some of the assumptions underpinning the empirical identification of bias as a problem. In particular, whether the routine exposure to 'biased' expertise presents a problem, let alone a serious problem, and if the survey results necessarily lead to the types of conclusions drawn by the authors.

Deceptively simple, Question 2.3 inquired:

Q2.3 What is the single most serious problem you have encountered with expert evidence?[26]

|

|

|

Frequency

|

Percent

|

|

(a)

|

bias on the part of the expert

|

85

|

34.84

|

|

(b)

|

use of oral or written language by the expert that was difficult to

understand

|

24

|

9.84

|

|

(c)

|

failure by the expert to stay within the parameters of his or her

expertise

|

14

|

5.74

|

|

(d)

|

non-responsiveness by the expert to questions

|

12

|

4.92

|

|

(e)

|

failure to prove the bases of the expert's opinions

|

34

|

13.93

|

|

(f)

|

failure by the advocate to pose examination-in-chief questions

appro-priately

|

34

|

13.93

|

|

(g)

|

failure by the advocate to cross-examine so as to make the expert

accountable

|

26

|

10.66

|

|

(h)

|

other

|

15

|

6.15

|

|

|

Total

|

244

|

100.00

|

Slightly more than one third (35%) of respondents identified 'bias on the part of the expert' as the 'most serious problem' with expert evidence. The investigators use these results as evidence for (their concern with) the prevalence and impact of bias — the issue 'most troubling' to Australian judges. But do responses to the survey support this assertion?

What is presented as, and initially appears to be, a sizeable proportion of judges alarmed by the incidence of bias can also be understood as an artifact of classification (or survey design).[27] This can be illustrated quite simply. Several of the answers included within Question 2.3 are similar or closely related. Instead of the answers supplied to the judges the authors might have offered alternatives. Depending on how they were configured and interpreted, alternative answers might have diminished the relative seriousness of bias. For example, rather than treat a series of quite narrow categories discretely, the authors might have combined these categories under a more generic description. So, among the possible answers presented in the survey, the authors might have combined '(e) failure to prove the bases of the expert's opinions', '(f) failure by the advocate to pose examination-in-chief questions appropriately', '(g) failure by the advocate to cross-examine so as to make the expert accountable', and perhaps even '(c) failure by the expert to stay within the parameters of expertise' under a more general rubric such as 'failure of advocacy'.[28] If we were to subsume these sub-categories within the category 'failure of advocacy' then this new single category would—on the basis of the responses received—represent the most serious problem with expert evidence (39%, and 44% if we incorporated (c)). The results of this alternative Question 2.3 might be presented as follows:

Hypothetical Q2.3A

What is the single most serious problem you have encountered with expert evidence?

|

|

per cent

|

|

(a) bias on the part of the expert

|

34.84

|

|

…

|

|

|

(y) failure of advocacy (e + f + g)

|

38.52 (ie, 13.93 + 13.93 + 10.66)

|

|

(z) failure of expert communication (b + c + d)

|

20.50 (ie, 9.84 + 5.74 + 4.92)

|

Consequently, the same data rearranged according to an alternative classificatory scheme might be used to suggest that 'failure of advocacy' is the most serious problem with expert evidence. Further, when added to perceived problems with communication, these issues (y + z, from Hypothetical Q2.3A) now account for about three fifths (59%) of the most serious problems with expert evidence.

Continuing our assessment; unlike the other answers in Question 2.3, 'bias' stands as a unified category. Yet, there appear to be few compelling reasons to treat 'bias' indivisibly. Restricting ourselves to categories recognised in the Report it would be possible to divide 'bias' into: deliberate bias or partisanship; inadvertent bias; bias that was difficult to ascertain, and perhaps even 'expert lacking credibility'.[29] Cognisant of these subdivisions, had 'intentional bias' and 'inadvertent bias' been incorporated into the survey we might have found that deliberate bias generated an even smaller volume of respondent disquiet. This might be represented as follows:

Hypothetical Q2.3B

What is the single most serious problem you have encountered with expert evidence?

|

|

per cent

|

|

(a.i) deliberate bias on the part of the expert

|

a.i ≤ 34.84

|

|

(a.ii) inadvertent bias on the part of the expert

|

34.84-a.i

|

|

…

|

|

|

(y) failure of advocacy (e + f + g)

|

38.52

|

|

(z) failure of expert communication (b + c + d)

|

20.50

|

Significantly, the division of bias along an advertent/inadvertent axis might have raised serious reform implications. The inclusion of such a division (particularly recognition of (a.ii) may have transformed some of the difficulties attributed to bias into an incorrigible feature of expertise, rendering the need for, or possibility of, reform uncertain.

These are not the only difficulties with Question 2.3. We are left to wonder about categories which were not included among the contenders for the single most serious problem. Why, for example, were judicial comprehension, the availability of experts, access to courts, impressions of jury competence, issues of delay and cost, impacts of recent reforms to tort law, or the effects of case management omitted?[30] Can we be confident that, had these options been included, bias would have retained its (empirically-mandated) status as the most serious contemporary problem with expert evidence?

Perhaps the most revealing dimension in the treatment of bias is the fact that judges were actually asked about it. The authors appear to believe that bias is a stable, tangible, observable quality and that their questions will produce consensus around its meaning and distribution.[31] We can be confident that these assumptions are intended because the Report does not treat the judicial responses ironically. That is, it makes no inquiry into what bias is or how it might be that judges consider themselves capable of ascertaining whether an expert is biased. Moreover, the survey makes no attempt to ascertain whether judicial images of bias are relevant to the practice of (different kinds of) experts or the reliability of evidence. In consequence, judicial responses are taken as an adequate indication of incidents of some entity known as 'bias'.

These theoretical assumptions and their methodological implications become self-defeating — especially in relation to the reform agenda. For if judges are able to identify incidents of bias and we can rely upon their observations, then why should we (or they) regard bias as a serious problem?[32] This leads to something of a paradox. If judges can identify bias then presumably they can deal with it. Alternatively, if they are unable to identify bias, or experience difficulty ascertaining it, then on what grounds can we rely on the judicial responses (to various questions in the survey)?

Another conspicuous difficulty with the emphasis on 'bias' — as a serious problem requiring intervention — is the quite limited judicial recourse to the mechanism of evidence law.[33] Unfortunately for the authors, this data would seem to destabilise claims about widespread practical difficulties posed by biased experts and/or discount the possibility of improvement through idealistic evidentiary and procedural reforms.

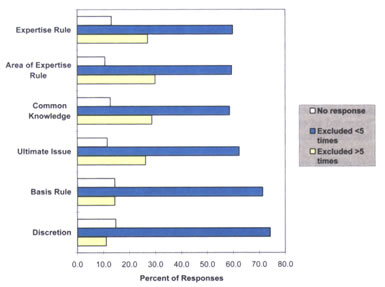

From the assembled data, judges would appear to have applied rules intended to guide, restrict and manage the admission and use of expert opinion evidence infrequently (Questions 7.2 and 7.3).[34] The survey results suggest that less than one third of the judges have excluded expert evidence more than five times on the basis of any rule recognised by the common law or codified in the Uniform Evidence Acts.[35] Consequently, we are left to speculate about whether, in their practice — as opposed to their responses to a multiple-choice questionnaire — judges conceive of bias as a serious problem. No attempt is made to reconcile responses which suggest infrequent recourse to the relevant rules of evidence with the analysis of Questions 2.2 and 2.3.

At this juncture it is helpful to reproduce Figures 15 and 17 from the Report. Figure 15 provides an indication of the limited recourse to evidence law, in the face of (the apparently) increasing use of expert evidence.[36]

Figure 15: Judges' Patterns of Exclusion of Expert Evidence (Q7.2) (AJP 86)

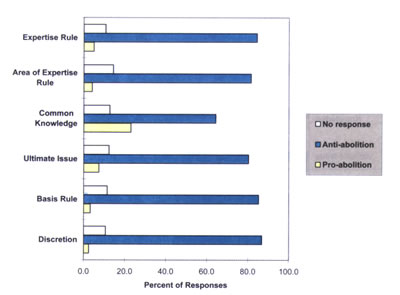

Figure 17 provides some indication of judicial reaction to questions about the abolition of common law exclusionary rules.

Figure 17: Judges' Views on Abolition of Common Law Exclusionary Rules of Evidence (AJP 88)

Notwithstanding limited use of the rules (in this context, at least) the judges are overwhelmingly opposed to law reform. Judicial antagonism to reform appears to extend even to those rules — like the ultimate issue rule — which, as the authors note, have received trenchant criticism for generations.[37] The data pertaining to the use of the Uniform Evidence Acts is analogous. Figure 17 can, and probably should be, interpreted in a way that is not consistent with widespread judicial commitment to incremental law reform, let alone fundamental changes to the adversarial system. The authors leave us to wonder why, if expert evidence apparently raises such serious problems, judges seem to be opposed to adjectival reform and do not seem to utilise the available rules to discipline biased expertise.

Just as the rules pertaining to expert evidence seem to be infrequently invoked, few Australian judges appoint experts (Question 9.2).[38] This trend is consistent with practices in other adversarial jurisdictions.[39] If biased expert evidence raises serious problems for judges, and non-partisan experts were readily ascertainable, we might have anticipated a more active exclusionary regime and greater use of court-appointed experts, assessors and referees.

It is possible that in addition to their commitment to the adversarial tradition, common law judges actually recognise some of the potential difficulties inherent in the identification of impartial experts and the need to assiduously manage such appearances through the course of a trial and appeal(s).

One of the possible interpretations of the data, especially the answers from Question 2.3 when considered in conjunction with other parts of the Report, is that even though 'bias' is consistently presented as the single most serious problem with expert evidence it may not be sufficiently serious to warrant concern or intervention. From this perspective 'bias' might be the proverbial molehill. It does not follow that 'the single most serious problem' in a finite series of problems is in actuality a threat to legal order. Perspectives transforms the most serious among a limited range of 'problems' into a serious legal problem.

Finally, in their judicially-predicated investigation of problems with expert evidence the authors do not reflect upon whether the judicial responses might be conditioned by professional ideologies and institutional commitments.[40] This oversight may be a consequence of the exclusive focus upon the judiciary.

The survey gives little depth or sociological insight into reasons why social groups might classify something as a problem or why different groups might classify different things as problematic.[41] Consequently, even if claims about the culture of partiality and the existence of partisan experts were not empirically justified, judicial recourse to the partisan expert (or 'junk science') might nevertheless be explicable. The Report makes no attempt to consider any advantages conferred through the maintenance of concerns about expert performance, especially the prevalence of bias, in contexts where judges regularly rely on expert evidence to rationalise their decision making. The fact that judges are routinely expected to make decisions, often involving the assessment of complex evidence, might orient their perceptions and performances in ways that tend to emphasise specific types of problems when publicly accounting for their practices.

In some circumstances, especially where judges have to decide and rationalise choices between competing expert opinions, they are in a position to benefit from images of complexity, expert disagreement and bias as well as more conventional images of mainstream science and methodological propriety.[42] In reversing decisions, especially when accounting for miscarriages of justice, the transfer of blame onto biased experts provides a particularly valuable means of maintaining legal institutional legitimacy. By shifting agency or responsibility for their decisions judges can attribute some responsibility to 'incompetent' or 'biased' experts rather than legal rules and institutions or the capabilities of fact-finders (whether judge or jury).[43] These representations need not be considered disingenuous. Complexity, communication difficulties and perceptions of bias would seem to form part of the judge's lived experience. In phenomenological terms, they form part of their lifeworld.[44]

Recognising these possibilities may help to explain the apparent judicial willingness to confirm the existence of bias. It might also shed light on why the majority of judges, apparently wedded to the existence of a range of serious problems, are not enthusiastic proponents of reform.[45]

Moving from the focus on bias, this section explores a range of more broadly based methodological problems with the survey design and presentation of results.

Judges are in a unique position to contribute an informed perspective on the way in which expert witnesses function within the adversary system.[46]

Perhaps the most fundamental weakness, of a general methodological order, relates to the privileging of judicial perspectives along with their conversion into an accurate account of legal practice. While it may be interesting to know what judges think about a range of issues, it is not appropriate, politically or methodologically, to simply substitute judicial opinions for reality.[47]

While the Report recognises the existence, even importance, of 'other legitimate perspectives', they are discounted against the 'particularly valuable experience' of judges.[48]

This is not to argue that other legitimate perspectives do not exist in relation to the role of experts in the courts but to acknowledge that judges have a particularly valuable experience on a day-to-day basis in dealing with the challenges posed by the presentation of expert evidence in their courtrooms.[49]

Apart from the opinions of magistrates, the authors make no attempt to ascertain these other 'legitimate' perspectives.[50]

Two important issues emerge from this orientation. First, judicial expertise is privileged and trusted. Judicial experience is transformed into expertise which demands deference. None of the checks and balances which the authors would impose upon non-judicial forms of expertise are invoked against judges. Typically, and inconsistently with the model(s) of expertise used elsewhere in the Report, there is no reflection about whether judges — as a class or profession — might be 'biased' or whether professional interest in the outcome of empirical description or law reform might be explained by recourse to 'judicial culture' (see 3.B.vi). Second, having identified the existence of alternative voices and perspectives there is no attempt to investigate or contrast them with judicial opinions. The exclusive focus on judges is inoculated.[51] The authors acknowledge a weakness in their methodology and proceed by ignoring it. Having acknowledged the legitimacy of other opinions, it is only the opinions of judges (and magistrates) that will count. Methodologically, this represents an elitist, and perhaps cynical, approach to social inquiry and law reform.[52]

Page one of Perspectives introduces the reader to the survey and its objectives. Initially, the survey is presented in a methodologically modest guise. As a survey of judicial attitudes it purports to provide 'a first and very important opportunity to understand what it is that the Australian judiciary thinks'.[53] At the bottom of the first page, however, the interest in judicial attitudes is subtly expanded. Judicial attitudes are insinuated as an important resource for law reform.

Since this is the first time that all of the Australian judiciary has been surveyed on any issue, there is added importance in the data elicited. In any future assessment of proposals to make changes to our litigation system, and to the admission of expert evidence in particular, the databank from this survey will be an important reference point in ascertaining judicial views.[54]

The reification of judicial attitudes — along with a willingness to rely exclusively upon them to support law reform — is conspicuous throughout the survey. Qualifications which problematise the (exclusive) interest in judicial opinions are practically ignored.

Two examples illustrate the authors' commitment to methodologically questionable uses of their data. Both are drawn from the 'Summary of Key Findings and Outcomes'. In the first example the authors explain: 'there are some findings which warrant response from litigation reformers. The purpose of this summary is to highlight those findings and to draw attention to important ramifications of the answers provided to the survey'.[55] At this stage we have moved from a survey designed to 'understand what it is that the Australian judiciary thinks' to one where the survey stands for a state of affairs which deserves a response. These tendencies become even more conspicuous and more urgent in the final paragraph of the first Part: 'The judges' responses to the questions posed in the survey require litigation reformers to customise their proposals for change to address the areas identified by the Australian judiciary as actually problematic in practice'.[56] On this occasion, the judicial responses 'require' reforms in areas 'they' have identified as problematic. In just 13 pages the purpose of the survey has expanded from a humble inquiry into judicial attitudes to a reliable dataset which demands an immediate response.

The data and analysis in Perspectives are presented as a reliable account of legal practice. Even apparently compelling data, however, could not redeem the exclusive focus on the judiciary. One profession's perspectives, especially when mediated through a multiple-choice questionnaire, do not provide an adequate description of reality nor an appropriate basis for substantial reform to legal practice.

There are many questions in the survey which are, methodologically, quite peculiar. What, we might wonder, is the value of asking the following questions of judges?[57]

Q3.9 Have you heard cases where you have formed the view that a key expert has been retained by one side just to make the expert less available as a witness for the other side?

Q5.1 In the cases over which you have presided which area of expertise do you think has presented the most difficulty for jurors to comprehend?

Q5.3 Do you think that the jurors have comprehended the expert evidence before your summing up? (and Question 5.4)

Q5.10 From the following list please circle the three factors which you consider to be the most persuasive for jurors when an expert is giving oral evidence?

Q5.11 From the following list please circle the one which you consider to be the single most persuasive for jurors when an expert is giving oral evidence?

Q6.5 Are most experts who give evidence before you representative of the views of their discipline? (and Question 6.6)

These questions, which may possess some value as an indication of judicial conceits (in the sense of beliefs or ideas), provide very limited insight into other dimensions of the legal system. Interest in judicial impressions might have been defensible if the Report had not proceeded to reify judicial attitudes, that is, if judicial perspectives had not been presented as an empirically adequate description of reality and an appropriate basis for law reform. However, both the range of questions and the uses to which the findings are put do not suggest an abstract interest in judicial attitudes.

While judicial opinions about these subjects might be interesting, there are few methodologically defensible grounds for simply privileging or relying upon them. The Report does not treat the responses as the contingent speculation of one particular group of participants in the litigation process. Instead, judicial opinions, even opinions on topics where there is no reason to believe that judges are particularly well informed, are construed as reliable evidence.

These tendencies are perhaps most conspicuous where judicial attitudes are juxtaposed to judicial impressions of jury attitudes.

Judges have a unique perspective of the travails of jurors …[58]

Having just considered the appropriateness and utility of asking questions about subjects removed from the experience or compass of judging, the issue re-emerges explicitly in Part 7 of the Report, 'Juror Problems with Expert Evidence'. Some of the methodological difficulties are apparent in the first sentences of that section:

Judges were asked about their views of the areas that have presented the most difficulty for jurors to comprehend (Question 5.1). Not surprisingly, the most common answer from respondents was that they "did not know" (28.99%, n=49) by reason of the limited feedback which they received from jurors.[59]

Elsewhere, the tone of the Report is less reflective and less qualified. It relies on the fact that judges: 'are therefore in a good position to form an opinion about the aspects of witnesses' evidence that make them particularly persuasive'.[60] On these occasions the responses are used in a way that goes beyond merely gathering information about judicial impressions and opinions. In their analysis of judicial responses to questions about 'jury problems', the authors treat the data as if judicial perspectives accurately reflected actual juror perspectives. The opinions of one group, the judges, are reified and substituted for the opinions of another. Rather than treat the results as indicative of judicial identity and professional differentiation (from imaginary jurors), the results are instead used as if they provide reliable information about the experiences of jurors.[61]

The disregard for the views and experiences of jurors (and other participants) is apparent in the treatment of the data.[62] But the methodological frailties become most palpable through the comparative approach, particularly in the use of numbers and diagrams:

Figure 14: Comparison of Judges' Opinions of Single Most Persuasive Factor when an Expert gives Oral Evidence (Q2.11 & Q5.11) (AJP 72)

Figure 14 reveals almost nothing about the jury. It does, perhaps, provide some limited insight into areas where judges believe they outperform juries in evaluating certain types of evidence.[63] While this was, patently, not the reason for the inclusion of the questions on the jury, the data could be read to suggest that judges believe they are better fact-finders than jurors (Question 5.2).[64] Figure 14 (above), for example, might be interpreted to suggest that judges believe that jurors require clearer explanations, undervalue impartiality and experience and, quite inappropriately, are more inclined to value the expert's appearance. Within the terms of the prefigured questions and implicit model(s) of expertise, judges present themselves as the more rational decision makers (see 3.B.vi).[65] This may constitute the only methodologically defensible use of these results.

The investigators' interest in substantive attitudes prevents assessment of the apparent willingness of judges to speculate about issues upon which they would seem to have limited knowledge. The willingness of respondents to answer questions speculatively introduces an additional level of complexity into the interpretation of the survey. It enables the judicial responses to be treated ironically — as a test and possibly an indictment of judicial reasoning abilities.[66] Widespread preparedness to answer several of the questions, apparently without any reliable foundation, might be considered disconcerting.

One of the conspicuous features of the survey is that many questions which might have afforded clearer (or more direct) indications of judicial impressions were not asked. Such questions, examples of which are set out below, might have operated as foils to particular interpretations. Rather than ask direct questions, several of the subjects examined in Perspectives are examined indirectly. This leads the authors to draw methodologically tenuous conclusions inferentially. In making this point it is only fair to acknowledge that there are limits to the number and variety of questions that can be included in any survey.

The earlier discussion of bias provides a useful example of a train of inquiry that was not pursued. Asking a judge which is the most serious in a list of problems or whether they have encountered partisanship is not the same as asking directly: Is bias a serious problem in contemporary litigation? Other questions which might have been incorporated — whether as yes/no, multiple-choice or open-ended — include versions of the following:

Should we reform the rules guiding the admission and assessment of expert evidence?

Do the vast majority of experts perform adequately?

Will the Declaration improve the standard of expertise entering courts?

Should we abolish lay juries?

Do unbiased experts exist?

How do you identify bias?

Why are so few experts subject to judicial censure, or charged with contempt or perjury?

Do inquisitorial systems manage expert evidence better than adversarial systems?

Should we adopt more inquisitorial procedures to manage expert evidence?

Is judicial comprehension of expert evidence a serious problem?

Should judges receive technical training?

Are judicial opinions an appropriate basis for law reform?

Should those who are not judges be consulted in relation to law reform?

While such questions could not have resolved these issues, each might have rendered particular interpretations of the data more difficult (or more compelling). For example, had judges expressed doubts about the value of the expert Declaration then claims about their desire for reform or belief in the value of (a particular) reform might have been weakened. Similarly, if judges were simply asked whether bias was a serious problem and whether it could be remedied procedurally, the answers may have structurally foreclosed several grounds of interpretation and reform. Instead, the authors and readers are left to infer and insinuate. The reluctance to ask more disruptive and — based on the authors' methods — potentially definitive questions suggests a degree of methodological timidity.

One of the most striking features of the dataset is the very large number of non-responses and 'I do not know' answers. Accepting that such responses are difficult to interpret, they are suggestive of respondent discord or inadequacies with the design of the survey instrument.[67] Of the roughly 100 questions (including sub-questions), 17 received between 25–50 per cent 'no response'/'I do not know'/'no opinion'/'missing responses' and 'it is not possible to say' answers and 16 received between 50–100 per cent 'no response'/'I do not know'/'no opinion'/'missing responses' and 'it is not possible to say' answers. Overall, a sizeable proportion of judicial respondents opted not to answer one third of the questions in the survey.

While the authors make few attempts to explain these results, they are occasionally acknowledged:

Not surprisingly, the most common answer from the respondents was that they "did not know" (28.99%, n=49) by reason of the limited feedback which they received from jurors.

However, the areas assessed as most problematic for jurors were most interesting …[68]

Here, methodological difficulties and judicial reticence are disclosed. However, having conceded these difficulties any implications raised by the non-responses tend to be disregarded in the ensuing analysis. For example, in the extract above, the apparent lack of surprise in response to judicial ignorance renders the original question somewhat curious. Nevertheless, the analysis continues relying on what might be considered the 'more surprising' answers.

Having examined a range of assumptions which shaped the construction and reception of the survey instrument, this section explores some of the inferential and analytical processes at work in the interpretation of the responses. These examples, while not entirely representative, do illustrate the compartmentalised treatment of different subjects and suggest that pre-commitments and assumptions appear to occasionally overshadow the actual judicial responses.

The first example is taken from the second page of the Report.

[T]he fact that it is now apparent that many judges are so troubled about the quality of medical, accounting, scientific and engineering evidence that they are prepared to give serious consideration to such aids to expert evidence assessment as the appointment of referees and assessors has many ramifications. One amongst many might be the appropriateness of conducting a pilot study into the utility of using medical referees in complex medical negligence cases.[69]

The passage features a discernible emphasis on judges being 'troubled' by the quality of certain types of expertise. We are informed that among the possible responses is a pilot study assessing the use of referees in complex medical cases. Yet the survey featured no questions on the utility of using referees in complex medical negligence cases.[70] When we examine the actual judicial responses to a question about medical evidence the answers are not consistent with their presentation in the extract above. In Question 2.5 — which is concerned with the ability of judges to evaluate complex evidence — only a small minority of judges (10%) indicated that they had ever encountered difficulty evaluating medical evidence.[71] When asked about the most difficult types of evidence to evaluate (Question 2.6) only a tiny proportion (2%) of judges thought medical evidence the most difficult.[72] In their responses to Question 5.1 judges attributed few problems to jury comprehension of medical evidence (only 3%).[73] However, in this context the most controversial data were produced by Question 5.7. Only 10 per cent (10%) of judges expressed a preference for removing cases with complex and conflicting medical opinions from juries.[74] Together, these responses would seem to indicate that judges and juries (at least from the perspective of 'the jury' manifested in the Report) do not perceive the evaluation of medical evidence as especially difficult.

Further, when we examine the actual commentary in the Report, the assessment of Question 2.5 appears to be inconsistent with comments taken from the executive summary. For example:

Psychiatry, psychology and medicine/surgery only figured in a handful of expressions of concern. Given the numbers of worries expressed about doctors with different plaintiff- or defence-oriented views, this was a surprising result, suggesting that though witness bias in the medical area is regarded by judges as relatively common, it is manageable.[75]

This passage sits very awkwardly against the earlier claims about bias and the assertion that problems with medical evidence might warrant a pilot study into the use of medical referees. Indeed, the authors would appear to have inverted their results. Significantly, the more alarmist claims about medical expertise — those drawn from the first extract — are taken from a section of the Summary entitled: 'Need for Procedural Change'.

'Let there be more efficiency and less theatre' was clearly the wish of many judges. Likewise there was ample recognition that expert reports, like affidavits, owe much to the guiding hand of the commissioning party's lawyer.[76]

And,

[t]he picture painted by a significant cross-section of respondents was one of worry about an unacceptable culture in sectors of disciplines providing report-writers and witnesses to the courts. The culture, they asserted, does not adequately value and put into practice independence, objectivity or transparency of opinions.[77]

Again, the contention that the 'guiding hand' of a lawyer constitutes a problem is not consistent with the data. The first issue, discussed previously, is that the investigators have asked respondents about activities remote from their judicial practice. The second difficulty is that the judicial responses do not support the authors' anxieties. Consider the following question and answers directed at the co-production of expert reports:

Q2.8 In the expert reports that are tended to you, does it appear that lawyers have played a part in settling the content (for example, as commonly happens in respect of lay affidavits)?[78]

|

|

|

freq

|

per cent

|

%-NR

|

|

(a)

|

never – please go to 2.10

|

61

|

25.00

|

25.85

|

|

(b)

|

occasionally

|

126

|

51.64

|

53.39

|

|

(c)

|

often

|

42

|

17.21

|

17.80

|

|

(d)

|

always

|

7

|

2.87

|

2.97

|

|

|

No response

|

8

|

3.28

|

|

|

|

Total

|

244

|

100.00

|

100.00

|

By themselves these figures would seem to suggest that a slight majority of judges think that lawyers are occasionally involved in settling the contents of expert reports. Without more, this might be represented as, and considered to be, a problem. Though to do so would require making prejudicial assumptions about the performances of experts and lawyers. However, when the responses to Question 2.8 are read in conjunction with the answers to the following question, concerns about lawyer intervention appear to be substantially allayed. Indeed, these results could be read as a judicial endorsement of the lawyer's 'guiding hand'.

Q2.9 If you answered the previous question (b), (c), or (d), what is the usual effect that this participation by the lawyers has upon your assessment of the weight to be given to the expert's evidence?[79]

|

|

|

freq

|

per cent

|

%-NR

|

|

(a)

|

it helps

|

72

|

29.51

|

40.22

|

|

(b)

|

it hinders

|

45

|

18.44

|

25.14

|

|

(c)

|

it makes no difference

|

62

|

25.41

|

34.64

|

|

|

No response

|

65

|

26.64

|

|

|

|

Total

|

244

|

100.00

|

100.00

|

Less than one fifth (18%) of respondents indicated that lawyer participation in settling expert reports 'hinders' their assessment of the evidence. The survey results would seem to suggest that many judges do not share the authors' concerns. They would also appear to present the outlines of more complex judicial impressions of lawyer–expert relations which might compromise the analytical value of the 'culture of partisanship'.

Perspectives discloses a latent tendency to treat the expertise attributed to judges differently from the manner in which non-judicial forms of expertise are treated. We have already seen (in Subsections 4.A, 4.B and 4.D) how judicial opinions are treated as unbiased, implicitly reliable and their analytical capabilities presented as superior to those of lay juries. Now we will consider an instance where apparent judicial limitations are neutralised.

In the following extract we can observe how, on this occasion, the responses of judges are excused on the basis of evidentiary complexity. The excuse is mobilised through the strategic use of more sociologically sensitive images of expertise:

All too often in the past the acceptance that there is no one answer has not been acknowledged sufficiently in the law's positivist search for definitive answers. The judges' response to this issue may be seen as demonstrating a consciousness of both the diversity of approaches and views in relation to many areas of expertise, and a cognizance that a number of fields of expert endeavour, when examined in detail, are significantly complicated. There is little that procedural reform or improved training can do to address this reality.[80]

Issues of complexity are recognised and discussed throughout the survey. However, when dealing with experts, complexity is rarely used to mediate (or excuse) their performances, or to suggest that impressions of bias might be misunderstandings or an incorrigible feature of expert knowledge. Different epistemological assumptions are applied to judges. Judges benefit from more sociologically sophisticated descriptions of expertise which recognise difficulties produced by uncertainty and complexity.[81] Judges are not criticised because they encounter difficulties understanding and evaluating complex forms of evidence. Experts, in comparison, are assessed against less sympathetic positivist-oriented criteria such as correct methods and ideal images of practice which implicitly require impartiality and high degrees of certitude.

The example reinforces the limitations of a survey which privileges the perspectives of judges. We can only assume that, had they been asked, experts might have attributed some of the responsibility for (the perception of) problems to complexity, processes of simplification, time constraints, resource limitations, arcane legal procedures and the technical (in)competence of lawyers, judges and jurors.[82] Surely those not included in Perspectives would have presented sociologically thicker descriptions of their practices, commitments and difficulties.[83]

Significantly, where expertise is conceived as diverse and complex (and perhaps genuinely contested) the authors appear to acknowledge that there is limited scope for improvement through procedural reform or further training.[84] Could it be that these, arguably more sophisticated, approaches to expertise render many of the other claims and proposals redundant? These questions would seem to be especially apposite if: complexity and uncertainty have the potential to influence perceptions of bias; much of the expert disagreement associated with litigation is legitimate (or we have no a priori means of distinguishing the legitimate from the illegitimate); or, we reject the positivistic commitment to unrealistic images of science and expertise.[85]

Inspired by insights and practices from socio-legal studies and the social sciences, the previous sections endeavoured to demonstrate how particular assumptions and representations in Perspectives contribute to the appearance of a range of problems with expert evidence in Australian courts. In effect, Sections 3, 4 and 5 provided an indication of how a public problem rhetoric can be generated or, more pertinent to the case of expert evidence, perpetuated using what appears to be a fairly innocuous survey instrument. The empirical warrant for claims about problems with expert evidence, particularly bias, was contested on the basis of theoretical and methodological limitations. This section continues the analysis by examining the connection between a range of policy proposals and the results of the survey.

Assertions about the need for reform and judicial support for reform pervade Perspectives. The following extracts, in conjunction with others cited in this section, exemplify the reformist orientation of the study and Report: 'In the meantime, there are some findings which warrant response from litigation reformers. The purpose of this summary is to highlight those findings and to draw attention to important ramifications of the answers provided to the survey'.[86] And,

… there is one step which can be taken straightaway to enhance the quality of expert evidence in Australian court rooms. Among expert witnesses and within the judiciary in England, in particular, recent years have seen a recognition of the need to develop codes of ethics and practice for forensic experts which will consolidate an expectation and practice of objectivity.[87]

The need for the proposed reforms and the existence of widespread and serious problems with expert evidence are presented as if they emerged without mediation from dispassionate judicial respondents. Consider the attribution of agency in the following passage:

They [the respondent judges] are concerned to reduce what they identify as a culture of inadequate objectivity by many doctors, accountants, scientists and psychologists, to improve the performance of experts and advocates alike and to explore means of bringing information before the courts in a form which is both clear and amenable to sophisticated and cost-efficient assessment.[88]

On the basis of the survey design and the data presented some of these claims appear hyperbolic.[89]

This subsection examines the proposals for reform in a way that is sensitive to their relationship with the survey dataset. The reform proposals are noteworthy for two reasons: (i) they target experts rather than advocates or judges; and (ii) they are not consistent with the results of the survey. The overwhelming focus on reforming expert practice might be considered, at the very least, curious in a survey of judicial attitudes. The data would seem to indicate that judges were as concerned about the performance of advocates and expressed a slightly stronger preference for training advocates than experts. The data also suggest the importance attributed to the clarity of expert evidence. The primary focus on expert performance, particularly reforms designed to eradicate bias, would therefore seem to be motivated by factors beyond the dataset.

At this stage we consider the reform proposals with respect to the protagonists identified in the Report.

One solution to such difficulties is to improve the training of experts.[90]

Most of the proposed reforms are directed toward the performance of experts. The centerpiece of the reforms, the expert Declaration, is the only proposal elaborated in any detail. The Declaration is set out in full and emboldened twice in the Report.[91] It appears first in the 'Summary of Key Findings' and again in 'The Future'. Presented as a partial solution to the serious problems attributed to expert evidence, the Declaration is intended to 'enhance the quality of expert evidence' — to eliminate, or substantially reduce, bias and change the culture around expert witnessing.[92] It aims to make experts (more) accountable. The authors propose, '[b]uilding upon the Federal Court Practice Note and recent initiative in England',[93] that experts should complete a version of the following:

|

I, ……., DECLARE THAT:

|

|

|

1.

|

I recognize that my overriding duty in writing reports and in giving

evidence is to the Court/Tribunal, rather than to the party commissioning

me

and/or paying my fees.

|

|

2.

|

I have used my best endeavours to produce my report in sufficient time to

enable proper consideration of it.

|

|

3.

|

I have made myself reasonably available for discussion of the contents of

my report with professional representatives of all parties

involved in the

litigation.

|

|

4.

|

I have provided within my report

|

|

|

(a) details of my relevant qualifications;

|

|

|

(b) details of the literature and other significant material that I have

used in arriving at my opinion;

|

|

|

(c) identification of any person, and their qualifications, who has carried

out any data selection, data inspection, tests or experiments

upon which I have

relied in compiling my report; and

|

|

|

(d) details of any instructions (whether in writing or oral, original or

supplementary) which have affected the scope of my report.

|

|

5.

|

I have used my best endeavours in my report, and will endeavour in any

evidence which I am called to give,

|

|

|

(a) to confine myself to expressing opinions as an expert within those

areas in which I am specially knowledgeable by reason of my

skill, training or

experience;

|

|

|

(b) to distinguish among the data upon which I have relied, the assumptions

which I have made, the methods that I have employed, and

the opinions at which I

have arrived;

|

|

|

(c) to indicate those data, assumptions and methods upon which I have

significantly relied to arrive at my opinions;

|

|

|

(d) to give succinct reasons for each of the opinions which I

express;

|

|

|

(e) to be objective and unbiased;

|

|

|

(f) to make the opinions which I express clear, comprehensible and

accessible to those not expert in my discipline;

|

|

|

(g) to be scrupulous in terms of accuracy and care in relation to the data

upon which I rely, my choice of methods, and the opinions

which I express

arising from those data;

|

|

|

(h) to indicate whether I have been provided with all the data necessary

for me to arrive at the views which I have expressed and

whether I need further

information;

|

|

|

(i) to indicate whether I have been apprised of any data or choice of

method which might entail opinions which are inconsistent with

the opinions

which I have expressed; and

|

|

|

(j) to indicate whether I have been unable for any reason to employ the

methodology which I would prefer to use before expressing

an opinion.

|

|

6.

|

If I become aware of any error or any data which impact significantly upon

the accuracy of my report, or the evidence that I give,

prior to the legal

dispute being finally resolved, I shall use my best endeavours to notify those

who commissioned my report or called

me to give evidence.

|

|

7.

|

I shall use my best endeavours in giving evidence to ensure that my

opinions and the data upon which they are based are not misunderstood

or

misinterpreted by the Court/Tribunal.

|

|

8.

|

I have not entered into any arrangement which makes the fees to which I am

entitled dependent upon the views I express or the outcomes

of the case in which

my report is used or in which I give evidence.

|

According to the Report:

such a declaration is eloquent in terms of the ideals expressed. In time, it is likely to forge a culture of obligation on the part of expert witnesses primarily to the courts, rather than to the parties paying their fees. Finally, the presence of such a declaration articulates values, departure from which is likely to lead to little weight being placed upon the defaulting expert's views.[94]

This highly idealised — or, to adopt the authors' terminology, 'positivist' — approach implies that a Declaration will change a partisan culture they associate with expert witnessing. It also implies that experts are generally inattentive to a range of existing ethical, legal and professional obligations. The Declaration's limitations will be explored in more detail below (see Section 7).

In the discussion of further education and training for experts, drawing from Lord Woolf's Access to Justice report,[95] the proposed instruction is oriented to the operation of the legal system; particularly the expert's duty to the court.[96] While a majority of judicial respondents (Question 4.1) thought further training of experts in their forensic function was 'desirable' (55%), only a small minority thought that it was 'necessary' (11%) or 'essential' (5%).[97] When asked (Question 4.3) about which areas might be most beneficial for training, the most frequent responses were in the disappointingly ambiguous realms of 'communication' (22%) and the 'expert's role' (16%).[98] Most interestingly, given the predilections of the investigators, training in objectivity (or impartiality), methodology, falsification and reliability were not included in the proposed syllabus.

Another area of potential reform, greater use of visual and information technologies, is treated perfunctorily.[99]

Overall, there is little reflection about the tractability of expert knowledge, public understanding, the implications of simplification, translation or the integration of expert knowledge into a legal case.

Ostensibly, the Report appears to recommend further training for advocates. In practice, however, there is a tendency to downplay apparent judicial concern with the performance of advocates. In contrast to the response to expert performance, when dealing with the legal profession, the market, formal educational and self-regulation are the preferred means of stimulating change. There is nothing equivalent to the Declaration directed toward the practice of lawyers.

Interestingly, the question concerned with the perceived need for further advocate training is not the same as the question purporting to deal with experts. The range of answers provided (in Question 4.4) is slightly different from the answers supplied in a similar question about experts (Question 4.1). The category 'essential' is dropped, thereby reducing the number of positive answers available to respondents. Nevertheless, the vast majority of respondents thought that further training for advocates was either 'desirable' (63%) or 'necessary' (23%).[100] Higher than the responses to similar questions about experts, in the analysis these results are presented as a perceived need for additional training: 'A clearer message about the need for further advocacy training could not have been given by the Australian judiciary'.[101] And, 'carefully targeted training has much to commend it and is enthusiastically advocated by judges'.[102] When asked about the directions for further training most judges selected 'improved preparation skills' (47%) and 'improved skills in cross-examination' (25%). Slightly more than one in 10 judges selected 'enhanced knowledge of technical areas' (11%).[103] This last response might be considered intriguing given the authors' prior assertion that effective cross-examination requires a basic technical understanding.

In the limited space dedicated to possible reforms to advocacy the Report notes that advocates should appreciate that developing their skills will confer a competitive advantage. Additionally, there is a suggestion that advocates might join a cross-disciplinary society. 'What is necessary is a change to legal culture to recognise that cross-disciplinary knowledge will assist in the discharge of both solicitors' and barristers' functions'.[104] We can only assume that, at this stage, such cross-disciplinary societies are largely composed of expert witnesses! The market and the increase in relevant undergraduate and postgraduate courses are presented as the appropriate regulatory mechanisms. Even though the data would seem to suggest that judges are more concerned with the performance of advocates than the performance of experts, the Report dedicates far more attention to the reform of expert practice. In effect there are no substantial proposals, and no proposals that might be readily implemented for reform to advocacy or advocacy training.[105]

Significantly, the discussion of experts and advocates is distinguished by the role objectivity plays in relation to each. Adopting highly conventionalised images of the adversarial system, professionalism and law–science relations, the major concerns pertaining to the advocate revolve around ethical issues and case preparation. The focus on experts is directed to bias and communication. The characterisation of the lawyer as a professional advocate and the presentation of expert knowledge as potentially partisan prevent investigation of the lawyer's role and agency (or 'guiding hand') in the selection, strategic manipulation and representation of expertise.[106] The models of law and expertise adopted by the investigators structurally preclude certain lines of investigation and are prefigured to attribute most of the responsibility for any problems to experts.

It might be considered surprising, in a survey investigating the attitudes of judges, that none of the proposals for reform and none of the assembled data are used to make substantial recommendations for changes to judicial practice. The approach, focused exclusively on judicial impressions, has largely predetermined the directions of reform. The authority of judicial opinions, filtered through the survey instrument, lends legitimacy to the reform of other parts of the system. In this way the survey acts as a form of empirical ventriloquism.[107] The imprimatur of judges is appropriated and used to promote a series of reforms — directed away from the judiciary.

These results may be the result of deference to judicial respondents or a failure to recognise some of the methodological limitations inherent in the survey. Having privileged the perspective of judges, the authors do not consider why judges might attribute responsibility for apparent problems to others. The authors take as self-evident the fact that experts and advocates are responsible for most of the difficulties with expertise. Consequently, there are no genuine proposals to change judicial practice. Proposals which are linked to judicial performance and the reform of evidence rules are flatly rejected by the vast majority of judges. In consequence, we have a survey of judicial respondents which attributes responsibility for problems with expertise to non-judges and resists the reform of judicial practice. The design of the survey and reforms — like the Declaration — is generally in the professional, institutional and managerial interests of judges. Depending on the models of expertise adopted, the Report might be understood as an exercise in victim-blaming and cost-shifting. Experts are blamed for alleged legal problems with their expertise and parties will bear the cost of any additional labour.

For as long as experts have been criticised as venal mountebanks and charlatans, there have been dissenting voices.[108] Experts have described their participation in legal settings in terms of exploitation, misunderstanding and abuse. Does the emphasis on the need to reform expert behaviour and change what is asserted as the 'culture of partisanship' merely perpetuate this longstanding and highly questionable dichotomy?

There are few references to parties or members of the public in the Report, and no reflection about any broader legal or social implications flowing from the proposed reforms. There is little concern about whether citizens will find accessing courts more difficult or more expensive. More particularly, the cost or admissibility implications of the Declaration are not discussed.

As we have seen, the purported need for law reform in the area of expert opinion evidence is a central and ubiquitous feature of Perspectives. According to the authors, problems associated with expert evidence require fundamental changes to the traditional Anglo-Australian adversarial system. Apparently, the need for reform is recognised by a substantial proportion of judicial respondents:

The judicial survey has shown that many judges are prepared to contemplate thoroughgoing reforms to trial procedure in both the civil and criminal areas in relation to expert evidence. Judges, and probably the general community, are no longer wedded to the traditional Anglo-Australian concept of the adversary system, in which litigation is entrusted to the hands of the parties and judges are expected to remain relatively uninvolved.[109]

And,

[t]he problems presented by expert evidence, amongst a number of contemporary problems within the civil and criminal justice systems, most particularly their cost and inaccessibility, have elicited from a substantial part of the Australian judiciary a preparedness to contemplate fundamental change to the structure of the litigation system.[110]

Having elicited the views and support of the Australian judiciary — a convenient and powerful substitute for the more limited number of judicial respondents — the authors hope to convert the judicial 'goodwill' into reform capital: 'The next step is to translate this goodwill into workable and cost-equitable procedures that will address the problems highlighted with the traditional means of adducing and evaluating party-generated expert evidence'.[111] These claims might have been more persuasive if they were supported by the data, if the authors had directly inquired about the perceived need for law reform and the alleged difficulties were incontrovertibly problems which could be improved by the particular reforms proposed.

There are few questions in the survey instrument which deal explicitly with the subject of law reform. A charitable interpretation of questions with obvious reform dimensions would encounter difficulty credibly extending beyond Questions 4.1, 4.4, 5.8, 6.2, 6.3, 6.10, 7.4, 9.5, 9.9 and 9.13. If we examine some of the more direct questions and those with the strongest support for the authors' claims then the fragility of the reform agenda will become more readily apparent.

The strongest support for possible reform arises in the context of further training for experts and advocates. In this context the majority of respondents indicated that 'training of experts in their forensic function' (55%) and 'training of advocates in calling and cross-examining experts' (63%) was desirable. About one sixth (16%) thought that such training was necessary for experts and about one quarter (23%) thought it necessary for advocates.[112] Significantly, the judges appeared to be more concerned with improving the performance of advocates. Though, as we have seen, this desire to have advocates trained is not reflected in the authors' substantial reform proposals. Rather, in line with their commitment to a particular public problem perspective, the authors focus on the need to rectify the performance of experts in terms of their objectivity.

Other potential evidence for judicial support for law reform concerns the use of court-appointed experts.

Q9.5 Are you of the view that more use of court-appointed experts would be helpful to the fact-finding process?[113]

|

|

|

freq

|

per cent

|

%-NR

|

|

(a)

|

yes

|

119

|

48.77

|

54.34

|

|

(b)

|

no

|

74

|

30.33

|

33.79

|

|

(c)

|

I do not have an opinion

|

26

|

10.66

|

11.87

|

|

|

No response

|

25

|

10.25

|

|

|

|

Total

|

244

|

100.00

|

100.00

|

Once again, what is presented as apparently cogent support appears, on inspection, more equivocal. Question 9.5 is, at best, indirectly concerned with law reform. Judges have been empowered to appoint experts for hundreds of years.[114] Recent reforms have tended to confirm or extend that power.[115] While almost 50 per cent of the respondents (49%) agreed with the proposition in Question 9.5, this cannot simply be equated with a preference for law reform or reconciled with a range of competing legal values, some of which are raised in Question 9.3. Agreeing with the proposition that the increased use of court-appointed experts might assist with fact-finding is not equivalent to supporting the use of more court-appointed experts or accepting that such experts are neutral or readily available. This seems to be supported by the low incidence of judges actually appointing experts unilaterally and, more pertinently, by the authors' own assessment of such appointments: 'Australian judges' support in principle for further use of court-appointed experts raises a number of practical challenges if it is to be implemented'.[116] The reform-oriented interpretation of Question 9.5 seems to acknowledge apparent inconsistencies between judicial authority, in-principle support and practical challenges. The authors have subtly transformed a question about the perceived value of court-appointed experts for fact-finding — in the abstract — into a question which purports to ask about mechanisms for improving the use of court-appointed experts or changing expert practice.