|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy |

Green Criminological Dialogues: Voices from Asia

Antonio Nariño University, Colombia; University of Oslo, Norway

Orika Komatsubara

Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, Japan

Laÿna Droz

Basque Centre for Climate Change, Spain

Tanya Wyatt

Northumbria University, United Kingdom

Green Criminology in Asia: A Platform for Dialogue Across Disciplines and Languages

Many different languages and disciplines are involved in Asian research on environmental conflicts. Linguistic diversity combined with the varied economic, legal, political and social contexts of the Asian continent gives birth to myriad debates about environmental crime and harm. Borders between disciplines are blurred and take different shapes depending on the linguistic and academic contexts. As a result of this situation, the many resources, knowledge and debates developed in various ‘bubbles’ hardly cross disciplinary and linguistic borders. With this special issue, we hope to contribute to unlocking doors and building bridges between the myriad Asian knowledge traditions about environmental conflict, crime and harm. Also, we aim to open the door for readers (be they scholars or practitioners) to engage with the debates and collaborate in addressing instances of environmental degradation in Asia. Finally, we want to remove the obstacles that separate the multi-disciplinary Asian scholars working on environmental crime from the green criminologists around the world.

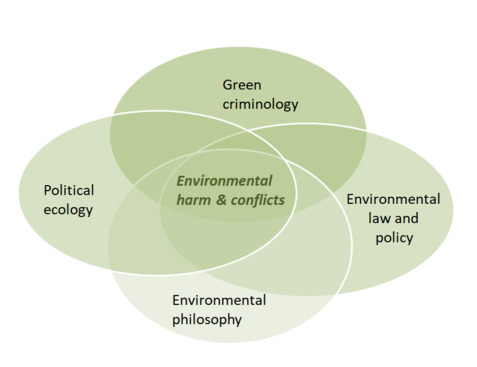

Green criminology is the study of harm, crimes and conflicts relative to the environment and ways to respond to them. The width of green criminology’s coverage makes it overlap with other disciplines: environmental law, environmental policy, political ecology, and environmental philosophy (see Figure 1) (among others). Green criminology needs be interdisciplinary. To us, green criminology can be more than that; green criminology can be the global platform that brings together insights from previously dissociated disciplines.

Figure 1: Interdisciplinarity, green criminology and the study of environmental conflicts. The shading of each area is intended solely for visual aid. Other relevant disciplines (such as ecology and environmental sciences) could be added to the sketch but were left out for readability.

In its aim and approach, this special issue falls within the branch of southern green criminology (Goyes 2018, 2019, 2021). Green criminology is critical (South 2014). Moreover, southern green criminology aims to unmask the sociopolitical structures detrimental to human societies, more-than-humans and ecosystems. This publication partly draws inspiration from some of the principles of southern green criminology:

• A reliance on the epistemological power of local communities and intellectuals to understand environmental conflicts, instances of ecological destruction and ways of resistance. Accordingly, this publication aims to make accessible to English-language readers insights from diverse Asian knowledge systems and traditions of thoughts about environmental conflicts, crimes and harms.

• A focus on how the imposition of a mode of being and living—namely, economic ‘development’—can have detrimental repercussions for ecosystems and societies. As such, several of the contributions in this issue shed light on the severe environmental and social problems induced by the rush to industrialise countries in the global South.

• An acknowledgement of the sociocultural and linguistic contexts that frame and influence the production of knowledge (including in the field of green criminology). Thus, many of the texts in this collection identify contextual and cultural particularities that embed dynamics unique to the region, country or community in which the phenomenon transpires.

Faithful to the principle of relying on local knowledge and experience, rather than imposing foreign mandates, this collection gathers contributors who identify themselves as members of disciplines and knowledge traditions other than green criminology: journalism, law, philosophy and beyond. Additionally, considering that the voices represented in this assemblage come from a region usually under-represented in the creation of English-language green criminological knowledge, this edition is doubly disruptive. First, it seeks to cross the boundaries of academic thinking by acknowledging ad hoc criminologist contributors who operate in other arenas, including activism. Second, it intends to destabilise Western dominance by highlighting the ideas inherent in other epistemic traditions; this is accomplished by making voices from Asian sociocultural contexts accessible to an English reader. Such a doubly disruptive work has proven to be something similar to Young’s (2011: viii) ‘criminological imagination’, as knowledge production has flourished amid ‘rapid change and environments of diversity’,[1] and all the articles included in this collection make a unique contribution to green criminological knowledge.

Articles and Their Unique Contribution

The first part of this special issue contains studies of instances of environmental harm.

In the first article, ‘Water Pollution and Environmental Injustices in Bangladesh’, Sarker Faroque and Nigel South (2021) analyse the dynamics—causes and consequences—of pollution in Bangladesh, focusing on water. One of the gaps in green criminology was the focus on water—the name itself of the discipline is symptomatic of the bias in the discipline that tended to forget the blue element. During the past few years, a group of scholars in the field have focused on water studies (Brisman et al. 2018; García Ruiz, South and Brisman 2020; Johnson, South and Walters 2015), highlighting the practices that drive water pollution and the connected ones that lead to water’s (and the pollution’s) inequitable distribution. While these studies partly touch on formerly colonial locations, such as Australia, the knowledge gap regarding the global South in green criminology is double: non-English speaking countries have received less attention, or it is foreigners who analyse the issue (Wallerstein 2004). As in other essays in the collection, the authors point out the role industrialisation has played in the pollution of Bangladesh, with factories contaminating the air, mega-projects generating noise, industrial extraction producing deforestation, digitalisation bringing about abundant electronic waste and the ship-breaking industry bringing about amounts of metal waste that surpass the capacities of the country. As Faroque and South remark, although these forms of pollution and the other drivers that lead to biodiversity loss seem to happen in isolation, their effects are cumulative and reflected in the contamination of water.

The authors explain that interconnected dynamics of industrialisation (notably, textile factories) have also directly contaminated surface and ground waters. Yet, although a Bangladeshi High Court ordered the government to start action to protect rivers and the Supreme Court, in 2019, assigned legal personhood to the Turag river—thereby entitling it to justice—there has been little concrete action to protect rivers and other water bodies from pollution, destruction and disappearance.

***

In the second article, ‘Injustice and Environmental Harm in Extractive Industries and Solar Energy Policies in Indonesia’, Dinita Setyawati (2021) explores the effects of embracing ‘development’ in Indonesia, as related to energy production and dissemination. Setyawati applies an energy justice perspective—which champions a fair distribution of the costs and benefits of energy production among communities, with a prospective interest also on future generations—combined with southern green criminology—which focuses on the impacts of the unequal power distribution between the global North, the global South and the colonial structures on the human interactions with the other beings in nature. Of relevance for Setyawati’s study are two sociopolitical structures that have existed in Indonesia since colonial times: a highly centralised system of nature management that has been exploited to favour national elites, and a colonially imposed demarcation between the urban and the rural. This article emphasises that the sociopolitical structures the Dutch rulers imposed during colonial times—such as an extreme political and administrative centralisation that kept the elites in power, and strict urban-rural demarcations—are still at play in energy policies in Indonesia and create significant environmental and social harms: corruption (such as price fixing), deforestation, land grabs and pollution stemming from coalmining, biodiversity loss, pollution and protest repression stemming from geothermal energy, and hazardous waste production from solar energy.

This article sheds light on the complexity and interactions of diverse types of injustices and harms, which reflect the need for an intersectional approach. It also indicates that exclusionary, vertical processes to find alternatives to fossil fuels often result in continued exploitation and more harm. This text confirms that the same dynamics that occur in other southern locations of the world are also at play in Southeast Asia.

***

In the third article, ‘Environmental Harm and Decriminalization of Traditional Slash-and-Burn Practices in Indonesia’, Rika Fajrini (2021) explores the topic of slash-and-burn practices (burning the land and the vegetation it contains to ‘clear’ land for new crops). Fajrini acknowledges that while this practice constitutes one of many parts of food production practices, it is highly environmentally harmful when used at a large scale by corporations. She warns against a one-size-fits-all response to the issue because a global ban can threaten the cultures and food security of Indigenous Peoples. Fajrini, with this (for green criminologists) counterintuitive article, reminds us once more of the risk of conflating a diversity of practices under a stigmatised label. This article then joins in one of the key debates that has emerged in the development of southern green criminology: Indigenous rights and self-determination versus the protection of the environment from a global (Western) perspective. In this key debate, some green criminologists have praised the Indigenous ways of relating to nature (Goyes, Abaibira et al. 2021; Goyes, South et al. 2021; Torres, Goyes and Torres 2020) while also acknowledging that Indigenous cultures can include practices that go against the principles of species justice and ecological justice (which champion the rights of non-human animals and ecosystems, respectively). The (apparent) dilemma that might appear is, shall we risk modifying a way of being that is mainly respectful towards nature to modify one undesirable practice, or shall we embrace the whole system despite some of its contents?

Fajrini’s article contributes to this debate by showing that Indigenous (and other minority groups) are often scapegoats for corporate crimes—in this study, they were the targets of accusations of destroying nature with slash-and-burn, but data indicates that corporations are those mainly responsible for fires. Relatedly, this paper shows that, while the normative and legal norm provides protection for Indigenous practice, the application of environmental law is selective with the individuals it punishes; the main recipients of punishments are Indigenous and local people rather than corporations, despite the latter being those mainly responsible for environmental harm derived from burns (for an early precedent of this insight, see Arreaza de Márquez and Burgos Finol 1981).

The article acknowledges that Indigenous peoples are perpetrators of environmental harm but also highlights that some of their detrimental practices are driven by structural changes motivated by the ‘broader society’—forced migration, takeovers of lands, market pressures, and loss of Indigenous cultures and institutions (for a similar argument regarding the exploitation of non-human animals, see Goyes and Sollund 2016). Fajrini also provides a further example of another environmentally and socially problematic phenomenon (see also Goyes and South 2019): the tendency for corporations to not only violate the rights of Indigenous communities to advance their interests but also exploit these same rights to pursue profit-making. In reading Farjrini’s article and allocating responsibility for the harms derived from slash-and-burn, it is useful to bear in mind the notion of tertiary green harms (Potter 2014: 11): those ‘committed by environmental victims or as a result of environmental victimisation’. Fajrini’s paper’s key message is that while the harm from traditional slash-and-burn does exist, we need to address it in a manner that will not re-victimise Indigenous people.

***

In the fourth article, ‘Primatology, Green Criminology, and the Impacts of Science on the Non-human World: A Debate from Japan’, Kazutaka Hirose (2021) narrates the trajectory of Japanese primatology, read through the conceptual lenses of anthropomorphism, the attribution of human characteristics to non-human animals; anthropocentrism, using the human point of view to interpret the world, which departs from green criminological definitions, having the point of view of human beings as the centre of the world (see Sollund 2012); biocentrism, an approach in which all species on earth, including humans, have equal intrinsic value (van Uhm 2017); and speciesism, human prejudice against animals of other species that leads to their oppression (Sollund 2013). His study reflects the ethical tensions about how to relate to non-human beings. Such exploration of speciesism is a core component of green criminological literature where speciesism is considered unethical because it assigns less value to animals-other-than-humans (see Sollund 2012, 2013 among others). The article highlights that anthropomorphism could (in theory) be non-speciesist by interpreting the actions and behaviours of non-human animals as humane, leading to a horizontal relationship between humans and non-humans, and for the acknowledgement of the individuality of the beings in nature. For instance, Hirose describes how the initiators of primatology in Japan recognised that they did not know whether the macaque monkeys had a culture before their contact with humans, but that a culture seemed to emerge afterwards. Nevertheless, as Hirose also shows, anthropomorphising can purposefully be used for speciesist reasons whenever assigning human traits to non-human animals is convenient for human interests, such as found in Hirose’s study—to advance the careers of Japanese primatologists. Of special interest is the use of the ‘empathy method’ by the initial primatologists who advocated anthropomorphism. While the method includes the word empathy which has a strong positive connotation, like Western care ethics (Adams 1996), the combination of anthropomorphising and caring for non-human animals can have the consequence of invading their habitats.

After almost half a century, Japanese primatologists shifted to a biocentric approach—one that acknowledges the specific qualities of primates and is involved in caregiving. The second wave of researchers worked to prohibit scientific experiments on primates and established a sanctuary for those who had already been affected by the practice; nevertheless, this wave of primatologists has also advocated for euthanising hybrid macaque monkeys, arguing that pure Japanese species are more valuable than hybridised ones. Thus, Kazutaka notes, some scholars have questioned whether a group of primatologists alleging to follow biocentric principles have possibly added nationality to the factors at play in the anthropocentric construction of animal hierarchies (the hybridised monkeys are part Formosan macaque (Taiwanese)) (for an analysis of the construction of animal hierarchies, see Wyatt 2013). Overall, Kazutaka’s study demonstrates the distance between rhetoric (in its negative connotation) and practice in human–animal relations, and humans have yet to find an adequate way to relate to animals and to engrain the laudable discourses.

***

The second part of the special issue focuses on dynamics of resistance to environmental harm.

In the fifth article, ‘Challenging Harmony to Save Nature? Environmental Activism and Ethics in Taiwan and Japan’, Laÿna Droz (2021), through an ethnological exploration of environmental activism in Taiwan and Japan, exposes the tension between globalised environmentalism as experienced by individuals and local cultural traditions. Using the moral shock theory to participation in social movements, Droz proposes that the process that drives individuals to engage in environmental activism includes four aspects: first, there is a cognitive and emotional shock regarding a perceived injustice; second, the shock leads to a change in personal practices and beliefs; third, the shock is then strengthened and broadened by exchanging ideas with similar-minded people; and fourth, these people organise themselves into a movement with a diversity of resources and try to change the current environmentally degrading dynamics of the world. Droz places these dynamics of personal transformation that lead towards seeking to transform the world vis-à-vis the dominating sociocultural contexts of Taiwan and Japan marked by Buddhism and Taoism. These traditions tend to invite followers to transform themselves and adapt to the world. Consequently, she explains how in these countries, communities praise ‘harmony’—defined as following the traditional roles and practices and avoiding disturbance—while reprimanding individuals who speak up. In sum, the ethos of global environmentalism that invites denunciation of ecologically harmful acts and tries to actively transform social practices and beliefs appears to go against traditional culture in Taiwan and Japan and can result in harassment, ostracism and stigma, which at times can lead to self-doubt, apathy and lethargy. Further, Droz underlines the importance of belonging to a community of activism for individual activists’ wellbeing and safety, thereby confirming the sociological trope of the importance of community belonging (Christie 2009). Interestingly, in her study, such communities can be found throughout the digital world.

This exploration adds to our understanding of the repertoire of protest cool-down techniques. Green criminology, as criminology in general, has developed deep, complex understandings and categorisations of diverse forms of violence (direct, silent, structural, symbolic, etc.) (Davies, Francies and Wyatt 2014; Galtung 1969, 1990; Wyatt 2014). Currently, environmental conflicts are increasing around the world, arguably due to the reduction of natural ‘resources’ (Goyes et al. 2017; Wyatt, van Uhm and Nurse 2020), and environmental social movements are one important factor trying to curb the pace of ecological destruction. Strategies to counteract social mobilisation depend on the sociopolitical and economic dynamics contextualising their action, from direct violence and murders in some Latin American countries and some regions of Asia (Global Witness 2019; Goyes 2016; Goyes and South 2017) to over-criminalisation, such as strategic lawsuits against public participation and surveillance in most European countries (Ellefsen 2012, 2016; Lee 2021; Vegh Weis 2019). With this study, Droz shows that there are active, invisible structural and powerful societal factors operating to hinder organised action against environmental destruction.

***

In the sixth article, ‘The Role of Literary Artists in Environmental Movements: Minamata Disease and Michiko Ishimure’, Orika Komatsubara (2021) explores how a literary writer, Michiko Ishimure, brought awareness to Minamata disease and created a collective action framework, a social movement used in their pro-environmental justice mobilisation. As such, this article is connected to Setyawati’s in that both study the social and environmental negative consequences of the rush to industrialisation. Komatsubara’s study brings attention to the crucial relevance of a cultural element still underexplored in the green criminological body of knowledge: fictional literature. Admittedly, green criminology has for almost a decade paid attention to how cultural representations affect our perceptions of nature and guide action, either protective or destructive (Brisman and South 2014, 2020). Such interest has created a green criminology with and about images (McClanahan and South 2019; Natali 2014), studies on the role of marketing in consumerism (Franko and Goyes 2019) and explorations of disruptive social movement practices that champion a slower society (Lee 2021). Green cultural criminology has also studied how literature creates and reflects broad societal narratives about nature (Brisman 2019; Brisman and South 2018, 2020). However, the field has neglected the interaction of literature with social movements. Komatsubara’s study, beyond its specific findings, is significant in opening a promising line of research.

Indeed, the literary landscape has recently seen the implosion of eco-thrillers or environmental fiction. The ‘real’ impact of this genre on people’s actions and political attitudes remains to be explored by green criminology. Of interest is the existence of two types of environmental fiction: utopian fiction, like Ishimure’s, which seeks to imagine a world with more respectful environmental interactions, and attract and mobilise readers towards them; and fear and warning, which projects a dystopian world where the current environmental crises magnify, in an attempt to deter people from adopting current dominating practices (see, for instance, ‘End of the Ocean’ by Maja Lunde (2021)). Komatsubara’s article shows the importance of integrating literary studies into green criminology and combining them with other trends of research already undertaken in the field, such as social movements (see, e.g., Ellefsen 2016). Another interesting aspect of this article is the tacit reference to animism as the religion Ishimure’s fantasy community embraces. Although fictional, the implicit mention of animism reveals another gap in green criminology: further, non-incidental research into the correlations between religion and environmental harm. The existing knowledge in the field about these connections is tangential information about how religion can propel or hinder the destruction of nature (Goyes, Abaibira et al. 2021; Sollund 2017). Luckily, Komatsubara continues to investigate, in a forthcoming article, the relationship between the Minamata disease movement and animism.

Conclusion

Our intention by pushing disciplinary disruptions with this special issue is twofold. First, we want to continue the work of criminological knowledge democratisation (Carrington et al. 2019; Carrington, Hogg and Sozzo 2016; Santos 2014) by increasing the visibility of authors who, due to their cultural, linguistic or national belonging, face exceptional barriers to publishing their work in international journals. Second, we embrace anthropology’s principle according to which it is in the exploration of the variety of cultures and ways of living around the world, where new ideas, ways of looking at the world and being appear (Beckerman and Lizarralde 2013). Considering that every arena of research runs the risk of ‘disciplinary atrophy’ (Dooley and Goodison 2019) when scholars keep repeating the same theories and concepts, only applied to new case studies, we find this collection of studies valuable for expanding the depth, breadth and fluidity of green criminology.

Correspondence: David Rodríguez Goyes, Doctor in Criminology, University of Oslo, Norway. Assistant professor at the Antonio Nariño University, Transversal 25 N 59-18, Bogotá, Colombia. d.r.goyes@jus.uio.no

References

Adams CJ (1996) Caring about suffering: A feminist exploration. In Donovan J and Adams CJ (eds) Beyond animal rights: A feminist caring ethic for the treatment of animals: 147–169. New York: Continuum.

Arreaza de Márquez E and Burgos Finol F (1981) Delito Ecológico como delito de Cuello Blanco [Ecological crime as a white collar crime]. Revista Capítulo Criminológico 7–8: 35–115.

Beckerman S and Lizarralde R (2013) The ecology of the Barí. Rainforest horticulturalists of South America. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Brisman A (2019) The fable of the three little pigs: Climate change and green cultural criminology. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 8(1): 46–69. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcjsd.v8i1.952

Brisman A, McClanahan B, South N and Walters R (2018) Water, crime and security in the twenty-first century. London: Palgrave.

Brisman A and South N (2014) Green cultural criminology. Constructions of environmental harm, consumerism, and resistance to ecocide. London: Routledge.

Brisman A and South N (2018) Autosarcophagy in the Anthropocene and the obscenity of an epoch. In Holley C and Shearing C (eds) Criminology and the Anthropocene: 25–49. London: Routledge.

Brisman A and South N (2020) Toward a green cultural criminology of the ‘South’. In Brisman A and South N (eds) The Routledge international handbook of green criminology, 2nd edn: 624–637. London: Routledge.

Carrington K, Hogg R, Scott J, Sozzo M and Walters R (2019) Southern criminology. London: Routledge.

Carrington K, Hogg R and Sozzo M (2016) Southern criminology. British Journal of Criminology 56(1): 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azv083

Christie N (2009) Små ord for store spørsmål [Small words for big questions]. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

Davies P, Francies P and Wyatt T (eds) (2014) Invisible crimes and social harms. UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Dooley BD and Goodison SE (2019) Falsification by atrophy: The Kuhnian process of rejecting theory in US criminology. The British Journal of Criminology 60(1): 24–44. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azz026

Droz L (2022) Challenging harmony to save nature? Environmental activism and ethics in Taiwan and Japan. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 11(1): 58-70. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcjsd.1969

Ellefsen R (2012) Green movements as threats to order and economy: Animal activists repressed in Austria and beyond. In Ellefsen R, Sollund R and Larsen G (eds) Eco-global crimes, contemporary problems and future challenges: 181–205. Surrey: Ashgate Publishing Limited.

Ellefsen R (2016) Judicial opportunities and the death of SHAC: Legal repression along a cycle of contention. Social Movement Studies 15(5): 441-456. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2016.1185360

Fajrini R (2022) Environmental harm and decriminalization of traditional slash-and-burn practice in Indonesia. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 11(1): 28-43. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcjsd.2034

Faroque S and South N (2022) Water pollution and environmental injustices in Bangladesh. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 11(1): 1-13. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcjsd.2006

Franko K and Goyes DR (2019) Global ecological destruction. In Franko K (ed.) Globalization and crime, 3rd edn: 193–212. Newcastle upon Tyne: Sage.

Galtung J (1969) Violence, peace, and peace research. Journal of Peace Research 6(3): 167–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/002234336900600301

Galtung J (1990) Cultural violence. Journal of Peace Research 27(3): 291–305. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0022343390027003005

García Ruiz A, South N and Brisman A (2020) Eco-crimes and ecocide at sea: Toward a new blue criminology. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624x20967950

Global Witness (2019) Enemies of the state? How governments and business silence land and environmental defenders. https://www.globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/environmental-activists/enemies-state/

Goyes DR (2016) Green activist criminology and the epistemologies of the South. Critical Criminology 24(4): 503–518. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10612-016-9330-y

Goyes DR (2018) Green criminology as decolonial tool: A stereoscope of environmental harm. In Carrington K, Hogg R, Scott J and Sozzo M (eds) The Palgrave handbook of criminology and the Global South: 323–346. UK: Palgrave.

Goyes DR (2019) Southern green criminology. A science to end ecological discrimination. Bingley: Emerald.

Goyes DR (2021) Environmental crime in Latin America and southern green criminology. In Oxford encyclopedia of criminology and criminal justice. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264079.013.588

Goyes DR, Abaibira MA, Baicué P, Cuchimba A, Ñeñetofe DTR, Sollund R, South N and Wyatt T (2021) Southern green cultural criminology and environmental crime prevention: Representations of nature within four Colombian Indigenous communities Critical Criminology 29(1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10612-021-09582-0

Goyes DR, Mol H, Brisman A and South N (eds) (2017) Environmental crime in Latin America: The theft of nature and the poisoning of land. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Goyes DR and Sollund R (2016) Contesting and contextualising cites: Wildlife trafficking in Colombia and Brazil. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 5(4): 87–102. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcjsd.v5i4.331

Goyes DR and South N (2017) The injustices of policing, law and multinational monopolisation in the privatisation of natural diversity: Cases from Colombia and Latin America. In Goyes Rodriguez D, Mol H, Brisman A and South N (eds) Environmental crime in Latin America: The theft of nature and the poisoning of the land: 189–214. Hampshire, England: Palgrave.

Goyes DR and South N (2019) Between ‘conservation’ and ‘development’. The construction of ‘protected nature’ and the environmental disenfranchisement of indigenous communities. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 8(3): 89–104. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcjsd.v8i3.1247

Goyes DR, South N, Abaibira MA, Baicué P, Cuchimba A and Ñeñetofe DTR (2021) Genocide and ecocide in four Colombian Indigenous communities: The erosion of a way of life and memory. The British Journal of Criminology 61(4): 965–984. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azaa109

Hirose K (2022) Primatology, Green Criminology, and the Impacts of Science on the Non-Human World: A Debate from Japan. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 11(1): 44-57. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcjsd.2016

Johnson H, South N and Walters R (2015) The commodification and exploitation of fresh water: Property, human rights and green criminology. International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice 44: 146–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlcj.2015.07.003

Komatsubara O (2022) The Role of Literary Artists in Environmental Movements: Minamata Disease and Michiko Ishimure. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 11(1): 71-84. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcjsd.1984

Lee M (2021) Policing the Pedal Rebels: A case study of environmental activism under COVID-19. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 10(2): 156–168. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcjsd.1887

Lunde M (2021) The end of the ocean. Harper Collins Publishers.

McClanahan B and South N (2019) ‘All knowledge begins with the senses’: Towards a sensory criminology. The British Journal of Criminology 60(1): 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azz052

Natali L (2014) Green criminology, victimización medioambiental y social harm. El caso de Huelva (España) [Green criminology, environmental victimization and social harm. The case of Huelva (Spain)]. Revista Crítica Penal y Poder 7: 5–34.

Potter G (2014) The criminogenic effects of environmental harm: Bringing a ‘green’ perspective to mainstream criminology. In Spapens T, White R and Kluin M (eds) Environmental crime and its victims: Perspectives within green criminology: 7–22. Farnham: Ashgate.

Santos BdS (2014) Epistemologies of the South: Justice against epistemicide. Boulder: Paradigm Publishers.

Setyawati D (2022) Injustice and environmental harm in extractive industries and solar energy policies in Indonesia. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 11(1): 14-27. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcjsd.1975

Sollund R (2012) Victimisation of women, children and non-human species through trafficking and trade: Crimes understood under an ecofeminist perspective. In South N and Brisman A (eds) Routledge international handbook of green criminology: 317–330. London: Routledge International Handbooks.

Sollund R (2013) Animal abuse, animal rights and species justice. Paper presented at the American Society of Criminology 69th Annual Meeting, Atlanta.

Sollund R (2017) The use and abuse of animals in wildlife trafficking in Colombia: Practices and injustice. In Goyes DR, Mol H, Brisman A and South N (eds) Environmental crime in Latin America: The theft of nature and the poisoning of the land: 215–243. New York: Palgrave.

South N (2014) Green criminology: Reflections, connections, horizons. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 3(2): 5–20. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcjsd.v3i2.172

Sword H (2012) Stylish academic writing. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Torres AI, Goyes DR and Torres G (2020) The right to life. Resurgence and Ecologist November/December(319): 14–15.

van Uhm D (2017) A green criminological perspective on environmental crime: The anthropocentric, ecocentric and biocentric impact of defaunation. Revue Internationale de Drot Penal 87(1): 323–340.

Vegh Weis V (2019) Green activism and indigenous claims under the language of criminality. The persecution of Argentinean indigenous peoples confronting state-corporate environmental harms. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 8(3): 38–55. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcjsd.v8i3.1244

Wallerstein I (2004) World-systems analysis. An introduction. Durham: Duke University Press.

Wyatt T (2013) Wildlife trafficking: A deconstruction of the crime, the victims and the offenders. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Wyatt T (2014) Invisible pillaging: The hidden harm of corporate biopiracy. In Davies P, Francies P and Wyatt T (eds) Invisible crimes and social harms: 161–177. London: Palgrave.

Wyatt T, van Uhm D and Nurse A (2020) Differentiating criminal networks in the illegal wildlife trade: Organized, corporate and disorganized crime. Trends in Organized Crime 23(4): 350–366. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12117-020-09385-9

Young J (2011) The criminological imagination. Cambridge: Polity.

Please cite this Guest Editorial as:

Goyes DR, Komatsubara O, Droz L and Wyatt T (2022) Special issue. Green Criminological Dialogues: Voices from Asia. Guest editorial. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 11(1): i-x. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcjsd.2108

Except where otherwise noted, content in this journal is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence. As an open access journal, articles are free to use with proper attribution.

ISSN: 2202-8005

[1] This is unsurprising, considering that as Sword’s (2012) large study demonstrated, interdisciplinarity is the epistemological tool that renders most academic innovations.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/IntJlCrimJustSocDem/2022/1.html