|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy |

Challenging Harmony to Save Nature? Environmental Activism and Ethics in Taiwan and Japan

Basque Centre for Climate Change, Spain

|

Abstract

To save nature, environmental activists in Taiwan and Japan are willing to

change their behavior and society itself, challenging “harmony”

in

their communities. This paper explores the tension between globally relevant

environmental activism and localized cultural traditions.

A wide-encompassing

understanding of environmental activism is proposed, based on a tentative

typology of different positions regarding

environmental sustainability. This

paper follows some environmental activists’ journey to moral protest,

through semi-structured

interviews and participatory observation conducted

between 2015 and 2019. It then discusses the results in light of some traditions

of thought in Taiwan and Japan. Interviewees often tell about an event in their

life that triggered a moral shock and exacerbated

their feeling of urgency.

Activists’ sense of purpose motivates them to navigate psychological and

social obstacles such as

social disapproval and exclusion. They also tend to

build a “community of activism” through social media to support each

other and develop strategies.

Keywords

Environmental activism; Taiwan; Japan; harmony; environmental ethics;

social movements.

|

Please cite this article as:

Droz L (2022) Challenging harmony to save nature? Environmental activism and ethics in Taiwan and Japan. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 11(1): 58-70. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcjsd.1969

Except where otherwise noted, content in this journal is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence. As an open access journal, articles are free to use with proper attribution.

ISSN: 2202-8005

This paper explores the tension between globally relevant environmental activism and localized cultural traditions. It presents the results of an exploratory study on environmental activists’ voices and perspectives within their specific sociocultural context in Taiwan and Japan, between 2015 and 2019. A wide-encompassing view of who environmental activists are is taken: they can be defined, following Parkin’s (2010: 1) definition of “positive deviant,” as “a person who does the right thing for sustainability, despite being surrounded by the wrong institutional structures, the wrong processes and stubbornly uncooperative people.” To further clarify what counts as environmental activism in this paper, a tentative typology of different positions regarding environmental issues is proposed. This paper scrutinizes the idea that in some sociocultural contexts in Taiwan and Japan, speaking up is discouraged, as it threatens the harmony of the community (Li 2013; Tao et al. 2009). In contrast, I show that instead of struggling to harmonize their own values with cultural expectations, the activists interviewed tended to gain a strong sense of purpose through moral protest—that is, protest triggered by moral indignation. In Taiwan and Japan, still today, activists can face high social risks. To support and learn from each other strategies to move from confrontation to commonness, environmental activists often build a “community of activism,” partly through online social networking.

Methodology

This article approaches environmental activism in Taiwan and Japan from the perspective of individuals who deliberately change their behaviors to adopt more sustainable ways of life. The research question addresses how environmental activists in Taiwan and Japan experience their pro-environmental activities, specifically if their experiences reflect ideas of harmony with a community and with oneself, which exist in Taiwan’s and Japan’s traditions of thought. Between 2015 and 2019, I made participatory observations when joining the activities of various environmental advocacy groups in both countries. I met key activists when taking part in public events such as the Earth Parade in Kyoto, Japan, on November 29, 2015, and the People’s Climate March Kyoto on April 30, 2017. In 2015–2016, I had the opportunity to complete a two-month internship with the Kiko Network, a climate-change advocacy organization based in Kyoto. Between 2016 and 2017, I also followed the activities of Green Action Japan, a nonprofit organization against nuclear power plants in Japan. In Taiwan, I was mainly in contact with people who had been engaged in the Sunflower Student Movement, in Greenpeace, and in the Green Party Taiwan, whom I first met in 2015. Both in Taiwan and Japan, these first contacts redirected me toward other individuals to interview.

Semi-structured open-ended interviews were conducted with a dozen environmental activists, mainly in summer 2017, while seven other activists preferred to remain anonymous and replied to an online survey (translated in Japanese and traditional Chinese). Interviewees were selected by snowball sampling. Some agreed to meet in cafés, public spaces, or at their apartments mainly in the regions of Taipei, Kyoto and Tokyo, while others replied anonymously to the online survey, which took about 20–30 minutes to complete. Interviews lasted about an hour and were conducted in English and Japanese (translated by the author), and a few were conducted in Chinese, translated together during the interview with friends of the interviewees. The online survey and responses to the survey in Chinese were translated with the help of multilingual colleagues.

The survey and interviews were organized in two main sections, based on preliminary results from participatory observations. The first section covered the environmental organization of which the interviewee was part, when and why they joined, how many members were volunteering and at what frequency, at what level the organization was active (local, regional, national, international), and how the interviewee was active. Another second section addressed the relationship the individual had with society and the wider sociocultural context. Open-ended questions included the following:

• What is the most important thing you want to change in your society and why?

• What would you like to transmit or preserve for the future (e.g., your grandchildren)?

• How is your organization perceived by the media, the government, your friends and family, and the public?

• Do you feel threatened or that it is risky to be part of the organization, and if so, why?

• Do you sometimes feel excluded or lonely because of your activism?

• Do you identify yourself as a member of a “global community” or as an “Earth citizen”?

• Do you practice meditation or self-reflection (diary writing, walking, zazen, etc.) or any religious activities?

Finally, I asked a series of questions aimed at understanding how the activists were collaborating with other organizations and volunteers, and what networking could help support their own activities.

Theoretical Framework: Moral Shock

These methodological choices allowed me to highlight the influence of sociocultural worldviews and personal life stories in each individual’s engagement. Results were analyzed and interpreted regarding the relation between ethics and environmental activism, both at the level of individual ethical worldviews of the activist, and at the level of the sociocultural imaginaries and constraints within which the individual develops and acts. At the individual level, what counts as a protest for different people covers a wide range of actions. Disobedience takes enormous amounts of energy and can be very subjective (Loizidou 2013). Moral protest generally refers to activists taking a strong public position and devoting part of their life to a cause, but activists in this strong sense are not the only one experiencing moral shocks. James M. Jasper (1997) coined the term “moral shock” to refer to the cognitive and emotional process encouraging individuals to actively participate in social movements. He argues that moral shock often forces individuals to articulate their moral intuitions and to reassess some of their behaviors and inaction, up to the point of engaging in moral protest. Jasper distinguishes four dimensions of moral protest: a personal and emotional life story, choices in strategies, shared stories, and resources.

The first dimension is closely linked with the individual biography and often involves a life-changing event—a moral shock. A moral shock often comes jointly with a feeling of urgency and marks the beginning of a series of moral shocks when the agent starts investigating further their moral intuitions and the state of affairs that they judge problematic (Parkin 2010). The second dimension questions “how” to fulfill the sudden drive for ethical action and depends closely on the context of the issue to be tackled, especially on the identities and social roles of the individuals and organizations perceived as obstacles and opponents to one’s objective (Jasper 1997: 44). Defying consensual practices involves taking a high social risk of being rejected and criticized by other members of the social community. Shared understandings and justifications bringing together emotional, moral, and cognitive aspects are core elements of successful communication and amount to Jasper’s third dimension of moral protest. Fourth, common stories can be a resource, as well as financial, educational, time-related, technical resources, and the necessary know-how required to make efficient use of them. Finally, Jasper notes that strong motivations and emotions can overcome a lack of resources.

Jasper’s idea of moral protest is used in this article as theoretical background to approach the individual process of engaging in environmental activism. The sociocultural imaginary characterized by the importance of harmonious relationships is approached thanks to philosophical theories. The tension between these two levels of analysis of the results echoes the tension between globally relevant environmental activism and localized cultural traditions.

Green Criminology and Environmental Activism

Environmental activism covers a wide range of actions that aim to foster sustainable ways of living and fight against environmental harm. Usually, it does not target the behaviors of specific individuals, but socially sanctioned practices, controversial activities, or laws. Environmental harm by states, corporate actors, different groups, and individuals are studied in green criminology (White 2014), and its scope can also encompass environmental activism. Brisman (2010: 162) argued that “green criminology needs to consider not just activities that hurt the environment and that are unregulated or underregulated, but also activities that are proscribed yet benefit the environment.” Further, Ellefsen (2012: 182) suggested that:

green criminologists should pay attention to these activities (that benefit the environment, humans and animals, yet being proscribed), but also such legal activities being threatened by criminalization or repressive use of existing law, and similar conduct subjected to state repression and/or policing that limits the possibilities of dissent.

Many practices of environmental activism fall into the latter category. The same action of an environmental protestor can be legal in an area or national context and criminalized in another, be it street or online protests or simply public criticism. Following this reasoning, green social movements and actions of environmental protestors can also be included in the field of green criminology (Carrabine et al. 2004; White 2008).

Along these lines, John Cianchi (2015) approached radical environmentalism in Tasmania from the lens of green criminology. He relates moments when people become activists due to a personal event or revelation—which echoes Jasper’s idea of “moral shock”—their subsequent associations and links with “nature,” and the social connections they develop as part of a community of activism. The findings of this paper reflect Cianchi’s research. The following discussion of the results situates the environmental activists’ positions in the political arena from their perspective situating environmental activism in the sociocultural context of the study, exploring the personal life story of the activists (including moral shocks, feelings of urgency, and relationships to “nature” or a “higher good), and describes how the interviewees engage with a “community of activism”.

Results and Discussion

What counts as protest and activism takes very different shapes in different sociocultural contexts. In the context of environmental debates, the actors in the political arena are not only nations, cultures and communities, but also, they are people following specific roles or are engaged in particular activities, and stakeholders engaged in practices that affect the environment—virtually everybody. Environmental activists encounter hindrances everywhere in the world. In South America, it is mainly direct violence that shuts activists down, while in Europe and North America, it tends to be the use of law (Goyes 2019). This article explores how in Taiwan and Japan, the sociocultural context that emphasizes harmony could represent one of the main hindrances to environmental activism.

Interviewees were participating in a wide range of activities, including reading groups about environmental issues; translation and diffusion of international environmental news; website, newspaper, and newsletter creation; social media activities; environmental education; demonstrations; press releases and media lobbying; elections; community building; local volunteer activities (e.g., waste collection); political lobbying; and street campaigning. Areas that were most important to them—including where they were engaged in activities—encompassed climate change, air pollution, oceans, biodiversity, nuclear power, renewable energies, waste, women/gender issues, poverty reduction, agriculture, peace, minorities’ rights, environmental education, and freedom of speech.

The Political Arena from the Perspective of Environmental Activists

The following typology of the positions toward environmental issues was sketched based on interviews, discussions, and participatory observation of environmental activist movements in Taiwan and Japan. It is a generalization of the political arena from the perspective of environmental activists regarding their own activities and the other groups with whom they interact. Categories were developed by content analysis of the discussions with environmental activists, where the lines between these categories are often blurred. This broad sketch aims to serve as a guide for readers to clarify the political arena in which participants in this study envision their activities and identities.

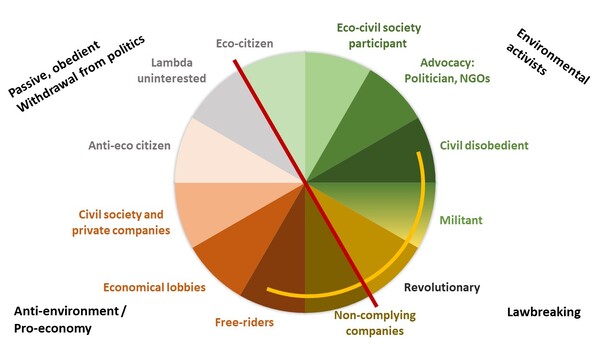

This typology illustrates a range of positions that can be taken relative to environmental issues (Figure 1). Despite important differences in the legal systems and in terms of sociocultural context, when it comes to negotiating practices and values related to environmental problems, several heterogeneous actors tend to be present. The main actors involved in hindering social changes toward environmental sustainability (private companies, economical lobbies, and free-riders) are in orange. In brown are non-complying companies—that is, companies that do not bother with existing environmental laws and break them to maximize their profits. De facto, they do not recognize the legitimacy of environmental laws and law enforcement bodies. Pro-environmental groups are also sometimes involved in lawbreaking activities. Revolutionaries refuse the legitimacy of the current sociopolitical systems and so do not respect the law, because it represents a world order that they oppose. Next to them on the green pro-environmental side of the circle are militants, who engage in direct actions aiming at partial change of the system regardless of the law (Brownlee 2015). Finally, a civil disobedient might break some specific laws, but does not challenge the legitimacy of the system and social structure (Droz 2019). This is the case for one of the Taiwanese interviewees who occupied, with her group, the ruins of an arena that “was supposed to be a park, but now they [government and companies] want to destroy it to build a huge shopping mall,” until being forced to leave by the government. Politically active, her group also provides legal support in environmental lawsuits. Free-riders, non-complying companies, revolutionaries, militants, and civil disobedients are all minorities in terms of percentage of the population involved in their activities, but their effects on the environment, on public discourse, and on the cultural imaginary tend to be important.

Figure 1: Typology of the positions that can be taken relative to environmental issues, from the perspective of environmental activists. Note: Figure created by the author.

Economic lobbies are the most active proponents of laisser-faire and risk-taking in environmental matters in the public sphere. They are at the forefront of shaping a discourse that prioritizes economic profit over environmental protection. They often receive active support from private companies, and they openly confront pro-environmental political advocacy actors such as politicians and NGOs. Companies, organizations, and groups that take advantage of the pro-environmental efforts of others to gather profits from environmentally harmful activities—free-riders—are enabled by the advocacy efforts of these economic lobbies.

The pastel colors in Figure 1 represent the majority of the population, as participants in the eco-civil society, or as eco-citizens, lambda citizens, or anti-eco citizens. Participants in the eco-civil society are individuals who, while not engaging directly in political advocacy with NGOs and political parties, are still locally active with associations and grassroots groups aiming at bringing small yet significant changes locally. These might involve waste-sorting activities and exchanges of unused tools or clothes, among other activities. In other words, they try to withdraw from groups involved in harmful practices as much as possible, but do not publicly oppose or confront them. Eco-citizens do not take any deliberate actions to change the practices of others, but they are environmentally aware, passively supporting sustainable changes, and subjectively “do their share” when it comes to small lifestyle changes such as turning off lights, buying local food products, and sorting waste.

The red line in Figure 1 represents the symbolic divide between agents who recognize the importance of pro-environmental changes of practices and lifestyles and who try to act correspondingly in highly diverse ways and to different extents, and agents who reject and avoid taking their responsibilities. In the sample of participants for this research, the wide-encompassing view of environmental activists includes anybody in the upper-right side of the red line (eco-citizens, eco-civil society participants, and advocacy), even if some interviewees have at some point engaged in activities that qualify as civil disobedience and involve lawbreaking. Lambda uninterested citizens are placed on the negative side of the circle, because their passivity and lack of interest support the discourses that promote harmful practices. Moreover, by default, their actions and omissions are likely to be environmentally harmful, as the current status quo is leading to severe environmental harm. Finally, anti-eco citizens are individuals who plainly reject their responsibility, often because they do not recognize environmental problems as relevant to their choices and lifestyles. They might benefit economically from harmful practices or might be blinded by anti-eco dogmas such as climate change denial.

The categories of this typology are contextual and dynamic. Still, they can be used to place environmental activist groups and to determine their main target audience when negotiating changes of practices. As the life stories of environmental activists will show, individuals sometimes shift positions around the circle. This typology sets the stage for the negotiations between the multiple actors or “representatives” (e.g., elected representatives, economic lobbies, private interest companies and investors, environmental NGOs) to unfold. Descriptions of these negotiations lie beyond the scope of this paper and are covered in the literature on stakeholder participation for environmental management (see Hiwasaki 2005; Reed 2008). Analysis of multi-stakeholder decision-making processes tend to erase the identities of individuals sitting around the negotiating table, and focus on the roles they endorse and the interests they represent. In contrast, many of the activists interviewed in Taiwan and Japan insisted on the importance of one-on-one interactions and interpersonal dialogue based on sharing personal experiences that show individual vulnerabilities. Could this insistence on interpersonal interactions instead of frontal opposition stem from the sociocultural focus on harmony?

Is Activism a Threat to Harmony?

At first glance, a common aspect of most East Asian ethical philosophical traditions such as Buddhism and Taoism is the apparent importance given to self-cultivation (Carter 2007; Roth 1991; Yuasa 1993). Priority seems to be given to changing the self to adapt to the world, instead of changing the world itself. East Asian ethical traditions tend to foster individuals to be “internally” active, which raises an apparent tension with environmental ethics understood as a form of environmental activism. Indeed, environmental activism presupposes that “external” actions can change not only behaviors, but also society itself to “sustain” the environment.

For example, in ancient Chinese philosophy, Xunzi considered self-cultivation and the practice of rituals as the expression of ethics (Stalnaker 2016). In Japan, this appears in the importance given to the execution of kata in martial arts or of specific rituals such as in tea ceremonies or flower arrangement. These practices are, of course, social, because their rules and procedures are defined by the community and by the cultural imaginary. However, their goal is the development and improvement of the self. This aspect is also reflected in the importance given to social roles in these societies strongly influenced by Confucianism (Feldman 2000):

Human activities must follow rigid forms as prescribed in the rituals (li) because these rituals are the manifestation in the individual of past cultural norms (represented by the formal aspect of the ritual) and of a new ideal expressed through the ritual acts (the feeling with which these acts are performed). (Mayeda 2015: 118)

The idea that one should lead life according to these ancient norms intertwining the social and the individual is predominant in Confucian ethics (Shin 2012; Wee 2011). For example, the individuality and the originality of an artisan are expressed through the excellency of the interpretation of their role in the society (Kondo 1992). In societies that emphasize harmony with others and the importance of family relationships, individual identities are constructed as interdependent and strongly connected with others. This stresses the importance of external features such as status, role, and relationships. It is considered essential to fit into a group and to fill a social role. Indirect or tacit communication is preferred (Singelis 1994).

From this perspective, the self is not expressed through open rebellion toward social standards, but through the reinterpretation of these standards and norms while understanding the importance of harmony within the interdependent community of individuals. The popular Japanese proverb often mentioned in my conversations with Japanese environmental activists, “the stake that sticks up gets hammered down,” offers a vivid image of how speaking up and standing out is socially discouraged.[1]

Environmental activists in Taiwan and Japan are sometimes confronted with social threats such as the threat of exclusion from their local community, social stigma, and cultural disapproval. Most of the environmental activists I discussed with in Taiwan and Japan experienced social isolation to different degrees, which directly affects their self-confidence. Their critical claims were not always welcomed by their relatives, colleagues, or social bystanders. Some interviewees explained that they were sometimes accused by other people in their “culture” to have been “brainwashed” by external discourses, sometimes called “Western propaganda.” This example shows that “coming out” as an environmental activist involves taking high social risks and may trigger identity costs. Moreover, whistleblowers are never welcome, because they shine a harsh light on problems and disturb the image of a harmonious society thriving gloriously to progress.

In some cases, environmental activists can be confronted by physical threats such as harassment, blackmailing attempts, and death threats. For example, when asked if he had ever been threatened as a member of an environmental group, a Taiwanese interviewee replied, “when the [political party] was formed to participate in the elections, it was threatened by local gangsters because it challenged the gang-backed candidates” (Online, August 10, 2017, Taiwan).

During informal exchanges, some interviewees active in protest against nuclear power plants in Japan also reported being followed, and one claimed that such pressures drove an acquaintance to suicide, while others suffered ostracism. Fortunately, most of the interviewed activists did not report facing such extreme threats.

In Taiwan and Japan, activists operate in a largely unfavorable sociocultural context and face sociopolitical obstacles such as social isolation, lack of resources, opposing laws, institutions and states, non-complying agents, and threats to one’s integrity and life. On top of these social and physical threats, activists also experience psychological obstacles including emotional aspects such as lethargy, apathy and lack of self-confidence, as well as personal doubts about the correctness of one’s own opinion concerning environmental issues. Indeed, contemporary environmental issues such as climate change are characterized by a high complexity and uncertainties. In a constantly changing and partially unknown system, neither cause–effect relationships nor what tools and actions are most appropriate to face and fix environmental problems can be fully determined. Standing up for one’s personal opinion and ideals and challenging the dominant state of affairs take courage and determination. Therefore, one can suspect that such a decision is not taken lightly, and that environmental activists would have carefully weighed the pros and cons.

Living in Harmony

When speaking up, the environmental activists to whom I spoke were often confronted with expressions of their non-confrontational, “harmonious” sociocultural backgrounds such as threats, ignorance and disapproval. However, they did not report feeling tension between the values driving their environmental activism and the values of harmony and compliance inherited from cultural ethical traditions. Some noticed tension between the role that they were expected to fit in (e.g., the expression “Good Wife, Wise Mother,” coined by Nakamura Masanao in 1875 to capture the idealized, traditional role of women) and their activity (e.g., spokesperson for a climate change advocacy nonprofit organization), but such tension does not translate to an internal struggle for coherence between personal values.

On the contrary, the narratives and life stories of most activists describe an improvement in their quality of life linked to a better “sense of purpose” and harmony within oneself. In this study, two main elements pushed the interviewees to become environmental activists. The first is a personal life story about how some environmental issues became important to one’s worldview. Some activists identified one specific life-changing event that made them decide that “they had to do it”. For example, change to the legal voting age in Taiwan to 18 years old was perceived by some interviewees as a success of youth movements that legitimized youth engagement and that empowered them to engage in activism. The other recurring element in the interviews is the feeling of urgency. Some action needed to be taken imperatively and needed to be done right now. In the conversations, many interviewees came up with the idea that environmental activism is one factor that is giving meaning to their life, not only to their everyday life, but also to their life as a whole.

The life story of Lin (not her real name) illustrates how the sense of duty and the sense of purpose intertwine in her practice of environmental activism—taken in the inclusive sense described above, as Lin did not recognize herself as an “environmental activist” and rejected the term as being “too strong.” I met Lin when she was campaigning as a Greenpeace activist on the streets of Taipei. In her childhood, her father took her mountain climbing and birdwatching and shared with her his love of nature: “He showed me how beautiful Taiwan (and the nature) is. Taiwanese people don’t know how beautiful it is. That makes me sad” (July 26, 2017, Taipei). Lin experienced loneliness until she started following the teachings of a Confucian mentor who taught her “how to communicate and connect with people.” Lin does not practice meditation, but reflects on herself and seeks to “teach others by example.” Yet, she insisted that she is not an expert about environmental issues, as she studied interior design. Although, she noted that working in this field was too busy and too “dark,” and overworking is not her dream. She pointed out shyly,

I don’t want to earn money to go to hospital. [...] I hope I can help the world. [...] When I’m old, I don’t want my grandchildren to look bad on me (like I’ve done nothing). [...] I want my life brilliant—wonderful. (July 26, 2017, Taipei)

For her, as well as for most of the interviewees, the social threat of exclusion or stigma is outweighed by the prospect of what would happen if nobody takes action. In Lin’s case, the fear of losing Taiwan’s beautiful natural environment got her interested in environmental issues; then, she realized other issues such as pollution in Taiwan and the polar ice caps melting in the Arctic were all related. Finally, she noted that before meeting her Confucian teacher, “the world was Taiwan,” but after, she feels connected to the whole world.

Lin’s story is an example of someone who moved from the blurred category of “eco-citizen” to that of “advocacy” in the typology. As Lin’s story shows, her reasons for committing to practicing environmentally friendly behavior and to start being an activist are often very emotional. Environmental activism involves turning the fear of losing into the will to protect. Environmental destruction and disasters are painful (“It hurts!”) and fill activists with sadness and sometimes despair (“I sometimes want to give up”). Yet, these intense emotions transform into anger and pro-active indignation. Finally, these mixtures of emotions are sublimated into an empowered enthusiasm and positivity about the real possibility for change.

The story of Chang’s (not her real name) commitment to veganism illustrates how a moral shock can trigger changes in habits and ways of life. She can clearly describe the turning point that drew her to take animal rights issues personally. Chang was deeply moved by a documentary about the animal product industry (meat, eggs, diary, etc.) that she watched at her Buddhist high school, where she regularly practiced meditation. She explained that in Taiwan, “many people don’t want to eat meat because it means killing the animals (and the suffering of sentient beings), but they are unaware of what’s happening behind eggs and milk production.” After watching the documentary, Chang decided to study chemistry to be able to make a change. However, soon she realized that changing the world is not only about knowledge and invention, but also about money and the diffusion of that invention. She became active online in different social media groups about veganism (exchanging information such as recipes, restaurants, shops, and documentaries), and she plans to open a vegan restaurant in the future, because she noticed it was easy to convince people through food, as “it’s a nice opportunity to exchange.” She does not feel threatened at all. On the contrary, she thinks that the population might support her, if she can explain what is really going on in the animal industry. She neither sees any tension between her activism and her cultural or religious practices. Chang pointed out that Buddhist teachings (which should always be taken with a critical mind, she adds) foster compassion for all sentient beings, and so are the arguments against the animal production industry. Yet, her activism is neither political nor religious and she does not challenge dominating powers in the public sphere. Her activity is personal, centered on her lifestyle, the people around her, and social media. In the typology, her story reflects a move from “eco-citizen” to “eco-civil society participant,” stopping short from engaging in “advocacy.”

Other elements unrelated to environmental issues—such as questions regarding democracy and peace, which can add to the feeling of urgency—trigger moral shocks and direct the choices in strategies for action. In Japan, a large part of the environmental activist community overlaps with movements rejecting nuclear weapons and power plants. In Taiwan, references to the peculiar geopolitical situation appeared in most of the interviews. For example, Lin indicated, “our history taught us how to fight. We know we have to fight.” Many of the environmental activists I met were part of the students occupying the streets with tents during the Sunflower Student Movement between March 18 and April 10, 2014 in the Legislative Yuan and Executive Yuan. A leader of a young green political movement explained that she feels that in Taiwan “there is no choice.” The “constant threat of mainland China” is pushing them to speak up (July 27, 2017, Taipei). For most Taiwanese environmental activists, the geopolitical situation of Taiwan reinforces the feeling of urgency and pushes them to take action.

These activist life stories show that taking ethical action for sustainability can be an emotional struggle (Parkin 2010: 216). This can appear in the form of reification of the sociopolitical mechanisms at the root of environmental problems, leading to fatalist expressions such as “there is nothing that can be done.” A “moral shock” can bring an agent to a “point of no return” (Parkin 2010) from where one learns and imagines what they can do, and becomes what Parkin calls a “positive deviant.” Yet, deviance is hardly perceived positively in some sociocultural contexts in Taiwan and Japan. This is reflected in Komatsubara’s (2019) analysis of the Minamata disease movement of 1970, which highlighted that the reason many Japanese citizens participated was due to moral shock, sympathy for the victims, and anger at the perpetrators.

Activism seems to threaten the “harmony” of the local traditional community, as it challenges the status quo and seeks to bring change. Activists are creating tension with those in power, and sometimes with the so-called traditional values, but they are not disconnected from their sociocultural context and values. They often describe being in harmony with “something higher,” which may be nature, the Earth, or their (re)interpretation of cultural values such as to transmit the heritage they received from their ancestors to their grandchildren, as beautiful as it was. They develop ethical justifications for their activities inspired by the sociocultural context in which they live. For example, when asked why and what he wanted most to leave for the future, a Taiwanese interviewee replied, “a beautiful Earth, because every life deserves the opportunity to share it.”

Concern for posterity also appeared in Lin’s quotation above. It recurs in the narratives of the environmental activists interviewed, and in their discourses to the public. In Japan, in demonstrations such as the Earth Parade or marches against the restart of nuclear power plants, a commonly chanted slogan is “for the future of our children” as well as “protect climate, protect the environment, let us walk together.”

Another common discourse pattern that emerged in environmental activists’ interviews and speeches is identifying with and fighting for a higher good, such as the beautiful prospect of living in harmony with nature. One narrative about the former golden age when humans were supposed to live in harmony with nature is often found in Taiwan and Japan, as shown by the successful “revival” of the concept of satoyama in Japan (Kagawa-Fox 2014; Takeuchi 2010). For example, it is difficult to express “wilderness” in Japanese, because there is no such thing as nature without humans. The idea of pristine nature as distinct from and uncontrollable by human beings is not commonplace in Japanese culture. Hayashi (2002: 35) writes that in traditional Shinto beliefs, “nature was a mysterious and powerful place, and people developed effective methods for living in harmony with it.” Such storytelling is very popular among Japanese environmental activists.

From Confrontation to Commonness: “Community of Activism”

In addition to the sense of purpose gained by committing to an environmental cause that matters to them personally, the environmental activists interviewed also tend to develop a sense of belonging to a “community of activism.” Online networking is a key resource used by activists to build a supportive community, learn from each other, collaborate, and connect with other like-minded people all over the world. Social media increase the importance of personal motivations and goals, because “the aggregate technological environment facilitates individuation” (Bimber, Flanagin and Stohl 2012: 184). Social media are nowadays an unavoidable tool for reaching the goals of activism, including civil society building, raising awareness, and putting pressure on companies.

All the environmental activists interviewed use social media to some degree, in three main ways—to exchange information, to get to know other like-minded people, and as channels to spread the message for which they are fighting. These echo the distinction made in Bimber, Flanagin and Stohl (2012: 29) between the three main contributors to involvement in an organization: there are instrumental, social, and the desire to be represented. These can also apply to membership in groups on social networking services, such as Chang’s activities in veganism groups on Facebook. The first reason to get involved is instrumental, as members receive a direct return through information such as vegan restaurants and recipes. The second is social and refers to interaction with other people sharing similar concerns and values. Third is the wish to be represented by the group about crucial issues, like Chang’s will to make her voice and indignation about the conditions of production of animal products heard.

Online activism, the third dimension, is usually wide and shallow because of the structure of social media. Activists use it to raise awareness and share information to the wider public about environmental issues. Social networking services are also used to put pressure on governments and companies through shaming strategies and online petitions (such as Greenpeace and Change.org online campaigns). Some non-governmental organizations provide “activist toolkits” to be used in various personalized ways online, from sharing a post to adding a “pin” on one’s profile picture showing their affiliation and support to a movement.

Ever-changing social media algorithms encourage users to engage “through the lens of subjective personal experience” and exchange information about their own passionate, personal and situated opinions, rather than “the objective, impersonal ‘big’ of public life that takes more time to digest and articulate, requires deliberation and is more difficult to commodify” (Marichal 2012: 63). Rational “common good” debate is not encouraged by the very structure of social networks. This has two paradoxical consequences. The first is the creation of a high diversity of cacophonous voices. Among them are those of environmental activists. Second, gradually, users tend to become isolated in groups of like-minded people and lose access to this messy diversity, as they “block” access to people with strongly conflicting opinions.

Social media also encourages the creation and flourishing of global networks of people sharing interest about general issues (Bennett 2003). They make possible the creation of a “community of activism” spanning large geographical distances, and sometimes also across time (as posts and groups are not erased even after long periods of inactivity). These networks are developed around multiple emergent and transient hubs often without any apparent hierarchy or leader. There are only a few formal transnational environmental activists’ networks in East Asia.[2] One of them is the Asia Pacific Greens Federation, founded in 2005 in Kyoto. It works as an umbrella organization and its members include the Japanese and the Taiwanese Green Parties. The activists I met tend not to be aware of such networks, or even not to have information about the activities of other activists in neighboring countries. However, some interviewees who had the chance to meet neighboring countries’ activists had built strong and friendly long-term ties.

Yet, social media seems to be relatively inefficient at changing one’s personal opinions or at engaging key players in a discussion toward concrete changes. Moreover, large-scale and global environmentalism can experience backlash (Franko and Goyes 2019: 211). Indeed, social media tends to crystallize a social identity and comfort individuals in their choices instead of stimulating them to engage in self-examination and rational debates from an—unavoidably artificial—objective position. Convincing other people about the importance of changing some behaviors or policies usually takes one-on-one conversations, according to most of the activists interviewed. The deeper reasons pushing activists to act are not rationally balanced principles, but emotionally charged ideals. Often, activists are aware of some apparent contradictions in their worldviews.

A long-term figure of anti-nuclear activism in Japan, Green Action Japan leader Aileen Mioko Smith, told me about her two “internalized contradictory mottos.” On the one hand, she recognizes that (the restarting of) nuclear power plants “can only be stopped together with everybody”. But on the other hand, she is determined that “even alone, I will do it!” (November 29, 2017, Kyoto). Throughout her career in the anti-nuclear advocacy movement in Japan, she is often confronted to the strict hierarchy of the administration that functions as “doors to prevent us from going higher in the hierarchy.” Facing unshakeable obstacles to make change, she is constantly questioning her methods to figure out “how to stop this thing from happening” (referring to the prospect of another nuclear disaster such as the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Disaster in 2011). Like many other activists, she concluded that the best way to change things was to change people themselves, one person at a time. Instead of confronting people with scary global long-term prospects and pointing out their dark role and their duties to act, it is more fruitful to “find in each person what makes them happier and find a match” with one’s own values and reasons for activism. Aileen described the long, smooth process of bringing one to choosing the principle that “empowers you, nourishes you,” and then becomes a core value.

The reasons why some individuals become environmental activists, and the observations made by activists like Aileen, show that environmental decision-making occurs at a very personal and deep level and goes to the core of one’s identity and guiding values. Thus, to influence decision-making in a long-lasting way, environmental activists need to find common ground with whom they are speaking and touch them emotionally with their own life stories. These one-on-one exchanges can shatter not only the person who might be having a life-changing conversation, but also the activists themselves, as the issues for which they are fighting are at the core of their identity.

Conclusion

Do environmental activists in Taiwan and Japan challenge harmony to save nature? On the one hand, yes, environmental activists seem to be disturbing, at risk to themselves, the sociocultural context of “harmony” Conversely, this sociocultural context represents perhaps one of the main hindrances to activism in Taiwan and Japan. On the other hand, environmental activists primarily change their own behaviors and ways of life, and could be said to reach greater harmony with the world and nature through activism. This bivalence reflects the tension between globally relevant environmental activism and localized cultural traditions. Despite the partially overlapping narrative of global sustainability, what counts as moral protest and environmental activism take different shapes depending on the localized cultural traditions. That is why I adopted a wide-encompassing understanding of environmental activism in this article and illustrated it with a tentative typology of positions regarding sustainability, as well as with stories of environmental activists’ journey to moral protest.

Lessons can be learned from the strategies developed by environmental activists in Taiwan and Japan in the face of a sociocultural context characterized by a tacit rejection of confrontation and open protests. For example, bringing the environmental debate to a personal level through one-on-one conversations and the personalizing lenses of online social networks may be a more inclusive move than elevating it to abstract philosophical realms. This might also bring to light what is common to all of us and support the ongoing building of a transnational public sphere based on personal interactions and relationships. More than political ideals, what binds us together globally are the intimate desires and everyday life concerns that make us human.

The global environmental crisis highlights the vulnerability and fragility of each of us to changes in our environment. We inevitably need to adapt ourselves, our cultures, and societies to environmental changes. Environmental activists challenge harmony in their community to seek to live in greater harmony with nature. Like any of us, they are not fully coherent in their reasoning and actions. Nevertheless, in Martha Nussbaum’s (1996: para. 1) words, we must not “indulge in moral narcissism when we flagellate ourselves for our own errors” while others are and will suffer from the consequences of our non-action. By voicing their concerns about environmental issues in a variety of personal ways, environmental activists are contributing to the building of heterogeneous, sustainable societies. They might also remind decision-makers that while they are debating the incoherence of some principles or facing conflicts of interest to pass certain laws and programs, environmental problems continue to unfold in many unexpected manners and threaten our cultures and existence.

Bennett W (2003) Communicating global activism. Information, Communication & Society 6(2): 143–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118032000093860a

Bimber B, Flanagin AJ and Stohl C (2012) Collective action in organizations: Interaction and engagement in an era of technological change. Illustrated edition. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Brisman A (2010) The indiscriminate criminalisation of environmentally beneficial activities. In White R (ed) Global environmental harm: Criminological perspectives: 161–192. London: Willan.

Brownlee K (2015) Conscience and conviction: The case for civil disobedience. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Carrabine E, Iganski P, Lee M, Plummer K and South N (2004) Criminology: A sociological introduction. London and New York: Routledge.

Carter RE (2007) The Japanese arts and self-cultivation. New York: SUNY Press.

Cianchi J (2015) Radical environmentalism: Nature, identity and more-than-human agency. Palgrave Studies in Green Criminology. London: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137473783

Droz L (2019) Transnational civil disobedience as catalyst for sustainable democracy. In Takikawa H (ed) The rule of law and democracy: 12th Kobe Lecture IVR Congress, Kyoto, July 2018: 123–134. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag.

Ellefsen R (2012) Green movements as threats to order and economy: Animal activists repressed in Austria and beyond. In Ellefsen R, Sollund R, and Larsen G (eds) Eco-global crimes: Contemporary problems and future challenges: 181–205. London: Routledge.

Feldman EA (2000) The ritual of rights in Japan: Law, society, and health policy. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

Franko K and Goyes DR (2019) Global ecological destruction. In Franko K (ed) Globalization and crime: 193–212. 3rd ed. London: SAGE.

Goyes DR (2019) Southern green criminology: A science to end ecological discrimination. Bingley: Emerald Publishing.

Hayashi A (2002) Finding the voice of Japanese wilderness. International Journal of Wilderness 8(2): 34–37.

Hiwasaki L (2005) Toward sustainable management of national parks in Japan: Securing local community and stakeholder participation. Environmental Management 35(6): 753–764. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-004-0134-6

Jasper JM (1997) The art of moral protest: Culture, biography, and creativity in social movements. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kagawa-Fox M (2014) The ethics of Japan’s global environmental policy: The conflict between principles and practice. London: Routledge.

Komatsubara O (2019) From victim emotions to victim expression: Consideration of victim–offender dialogues in the One Share Movement in Minamata in 1970. Contemporary Life Philosophy Research 8: 57–129.

Kondo D (1992) Multiple selves: Aesthetics and politics of artisanal identities. In Rosenberger N (ed) Japanese sense of self: 40–66. London: Cambridge University Press.

Li C (2013) The Confucian philosophy of harmony. London: Routledge.

Loizidou E (ed) (2013) Disobedience subjectively speaking. In Disobedience: 120–136. London: Routledge.

Marichal J (2012) Facebook democracy: The architecture of disclosure and the threat to public life. Farnham: Ashgate.

Mayeda G (2015) Time, space and ethics in the thought of Martin Heidegger Watsuji Tetsuro, and Kuki Shuzo. London: Routledge.

Nussbaum M (1996) Double moral standards? A response to Yael Tamir’s “Hands Off Clitoridectomy.” Boston Review (October/November). https://bostonreview.net/archives/BR21.5/nussbaum.html

Parkin S (2010) The positive deviant: Sustainability leadership in a perverse world. London: Routledge.

Reed MS (2008) Stakeholder participation for environmental management: A literature review. Biological Conservation 141(10): 2417–2431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2008.07.014

Roth HD (1991) Psychology and self-cultivation in early Taoistic thought. Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 51(2): 599–650. https://doi.org/10.2307/2719289

Shin DC (2012) Confucianism and democratization in East Asia. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Singelis TR (1994) The measurement of independent and interdependent self-construals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 20(5): 580–591. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167294205014

Stalnaker A (2016) Xunzi on self-cultivation. In Hutton EL (ed) Dao companion to the philosophy of Xunzi: 35–65. Dao Companions to Chinese Philosophy, vol. 7. Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-7745-2_2

Takeuchi K (2010) Rebuilding the relationship between people and nature: The Satoyama Initiative. Ecological Research 25(5): 891–897. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11284-010-0745-8

Tao J, Cheung ABL, Painter M, and Li C (eds) (2009) Governance for harmony in Asia and beyond. London: Routledge.

Wee C (2011) Xin, trust, and Confucius’ ethics. Philosophy East and West 61(3): 516–533. https://doi.org/10.1353/pew.2011.0047

White RD (2008) Crimes against nature: Environmental criminology and ecological justice. Portland: Willan.

White RD (2014) Global environmental harm: Criminological perspectives. London: Routledge.

Yuasa Y (1993) The body, self-cultivation, and ki-energy. Albany: SUNY Press.

[1] A historical analysis of social movements, resistance, and environmental activism in Taiwan and Japan is beyond the scope of this paper, but it is important to highlight that there are also stories of successful resistance bringing positive results for the community. For example, in the history of Japan, during the Edo period (1603–1868), peasants repeatedly revolted and engaged in resistance activities.

[2] In the history of the environmental movement in Japan, lectures on environmental activities all over Japan were held and networked in the “Jishu-Koza,” a citizens’ activity launched in Tokyo in the 1970s. They also published a booklet in English, “Polluted Japan,” in solidarity with environmental organisations in Asia such as Korea, Thailand, and the Philippines.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/IntJlCrimJustSocDem/2022/6.html