|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy |

We Don’t Become Adults, but are Told to Be Adults: The Emergence of Adultification in Japan

Yoshie Udagawa

The University of Tokyo, Japan

Abstract

Keywords: Juvenile law reforms; responsibility; adultification; neoliberalism; public policy; public opinion.

Introduction

There has been a long-standing debate over viewing a child as someone in need of protection and guidance or as an independent being naturally endowed with an innate ability for self-determination. This has been an aporia over the centuries, as has the dividing line between adult and child. This conflict manifested in myriad ways internationally, and Japanese involvement with this struggle has been reflected in the Civil Code and in juvenile law, particularly in changing definitions of the age of adulthood since the 1990s. Since debates over the definition of childhood have accompanied these discussions of Japan’s legal system, the lowering of the voting age from 20 to 18 in 2015 may be said to have emerged in direct response to the childhood debates (Mainichi Shimbun 2017). Moreover, the Japanese government amended the law in 2018, lowering the legal age of adulthood from 20 to 18—a change that took effect in 2022. Discussions on lowering the age of majority then shifted toward the application of the Juvenile Act. Instead of similarly changing the age of criminal majority, a new legal framework was established and enacted for justice-involved youth, specifically those aged 18 to 19 (Ito 2021).

Based on the surrounding discussion, this amendment is considered a transitional or an iterative move toward the original goal of lowering the age of juvenile law in the future. Globally, several countries have decided to change the upper age limit of the juvenile justice system, either to better accommodate adolescents in the transition from childhood to adulthood or to use a more repressive approach toward justice-involved youth (Schmidt, Rap and Liefaard 2021: 173). The legal framework in the Netherlands provides an example of the former, one in which young adults between the ages of 18 and 21 who were involved in the justice system could already be subject to juvenile sentences, but the country also applied scientific insights on youth development and maturation to the legislative reforms, raising the upper age limit from 21 to 23 in 2014 (Schmidt, Rap and Liefaard 2021: 173). Likewise, the trend in the United States (US) in recent years has been to raise the age of juvenile court jurisdiction so that young people “have access to more age-appropriate services and placement options to meet their specialized needs” (National Conference of State Legislatures 2015). The legal reform in Japan is considered the latter case, one that downplays evidence-based data and scientific insights. Several scholars have discussed global reforms similar to Japan’s in connection with the effects of neoliberalism, which positions youth as autonomous and self-possessed individuals responsible for their actions and which regards crime as an individual issue rather than a public one (Hall 2011; Harvey 2005; Turner 2014).

Similarly, the global debate about expecting young people to be autonomous individuals manifested in discussions on the age of maturity in the Civil Code in Japan, where young people are being targeted for fraud or sexual exploitation, such as forced pornographic performance, because their judgment is immature, and their knowledge of the law is inadequate for the challenges confronting them (Mainichi Shimbun 2017; Tadokoro 2022; Yoneda 2021). In terms of human maturity, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (2008: 63) in Japan provided the guideline that a human life can be divided into six life stages, with adolescence/young adulthood being the period 15 to 24 years old. Adolescence is further described as the period of time “when reproductive functions are physically completed and the transition from childhood to adulthood takes place” as well as “when the life environment changes drastically as a result of employment, ... and the individual acquires the lifestyle habits of an adult” (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare 2008: 64). Adolescence is also considered an important transitional period, and the fact that the brain develops until the mid-twenties supports this from a scientific standpoint (Arain et al. 2013). Therefore, lowering the legal age of adulthood by two years implicitly seeks to shorten this preparatory period. However, at the institutional, social, and educational levels, preparation for maturity has not kept pace with this change. For instance, policymakers and politicians hoped that lowering the voting age by two years in the Civil Code in 2015 would increase voter turnout, an expectation that went unrealized (Japan Educational Press 2019). In reality, citizenship education is still in its infancy, while teachers are required to be overly neutral on controversial political topics and schools seem to be struggling to provide a space for learning democratic debate (Hisada 2021; Tanaka 2021). While changes such as these imply that school education in Japan avoids discussing controversial and sensitive topics for fear of fostering prejudice and discrimination, one child-culture scholar pointed out that children need to learn how to discuss issues in public to prepare them to become “legal persons” and that schools should provide that in their education (Nakajima 2022). Thus, legal redefinition of adulthood requires integrating many fields, including education and social welfare, for the gestalt solution to permeate the general public, but the currently proposed linkage does not appear to be functioning well. While difficult to demonstrate vis-à-vis specific evidence, it is hard to shake the impression that the law is being driven by the interests and agendas of those in power, leaving those most affected in an unenviable position.

Ultimately, the public sphere and official policy need to interrogate what lowering the age of adulthood implies toward the young, especially justice-involved youth; careful consideration would further ask whether there were new expectations or imaginings about them and, if so, what those expectations implied. Youth are frequently exploited or denigrated internationally, making an investigation into criminal policy toward juveniles particularly relevant. Thus, the purpose of this study is to explore how the power dynamics of marginalization, normalization, and objectification manifested in the debates on juvenile justice reform. It is critical to examine the social and historical context of the concept of a child and childhood prior to these legal changes. This study aims to question the concept of childhood within the framework of justice-involved youth. It uses secondary data analysis and discourse analysis on the relation between public opinion, the media, and the legal system in connection with the emergence of adultification—the forced transition from child to adult influenced by media representation, as defined by Postman (1994)—and its problems for society: the promotion of marginalization and the imposition of self-responsibility on individuals. The process of maturing from child to adult requires learning, specifically learning not being pushed by responsibility. This study also suggests how the voices of those who are most affected by this law (e.g., the justice-involved youth themselves) were absent from the discussion.

The Late-Modern History of Juvenile Crime and Children in Japan

The 1990s were a period of remarkable transition in children’s rights around the world and in the history of youth justice involvement in Japan particularly. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child were adopted in 1989, and Japan ratified it in 1994. This marked a turning point for children under 18 because they were recognized, officially and globally, to hold their own rights, including the right to have a secure and safe living environment, the right to be protected from harm, and the right to be treated with respect as an individual human being. Meanwhile, notions of self-determination, freedom, and responsibility, being debated on several fronts, were also expanded to children. The application of these notions extended into the functionality of juvenile law, coinciding with a rise in the number of juvenile crimes and the media’s focus on the brutal nature of many of these crimes in Japan. People were astonished to learn of such crimes, wondering how juveniles could commit such cruel acts without adult involvement. This consternation led to a change in the conception of the child or juvenile from the conventional image of a dependent being in need of protection to an impression of an independent being with the same responsibility and conscience as an adult. Accordingly, notions of childhood began to change during the 1990s.

In Japan from the 1990s into the 2000s, juvenile crime was linked to the image of “snapped kids” (kireru kodomo), those children who suffer a mental break and act out of control (Doi 2003: 51–52, 198, 294). Doi (2003: 294, 299) noted that depictions of snapped kids were generally impulsive, cruel, and ominous and were associated in public discourse with the phrase “darkness in the heart” (kokoro no yami). The media circulated popular images of contemporary youth, including self-isolating individuals like those who sequester in their own room, rejecting any contact with society (hikikomori). This conception was produced and influenced primarily by the appalling murders committed by a 14-year-old boy in 1997, known afterward as the Sakakibara incident. The Sakakibara incident is remembered as one of the most brutal murders committed by a minor, leading to changes in the juvenile justice system. The incident involved a 14-year-old, referred to as “Boy A,” who, unassisted, committed two homicides and three assaults (though it was not initially recognized as a series of linked attacks). One of these crimes, the murder of an 11-year-old mentally handicapped boy, received massive and continuous media coverage. The media reported this murder as an extraordinarily eerie event, and they released descriptions of the offender as a psychopathic, perverted adult man (Asahi Shimbun 1997; Mainichi Shimbun 1997: 29; Takao 1997: 42–44). The murder was immediately shocking due to its cruelty and brutality; then it was revealed that the offender was a 14-year-old boy and that the incident was one of a series of attacks. The incident had already been presented as controversial to entice media and public attention, and the media’s portrayal of the incident further contributed to the moral panic before Boy A was arrested. Media reports provide evidence of how transmitted information was exaggerated and inaccurate under the panic and how massive media coverage accelerated the social phenomenon of moral panic and amplified fear among the public.

In their portrayals of the culprit, the media emphasized the psychotic aspect of Boy A; therefore, it left the public with many fears and unanswered questions. Indeed, the media excessively covered the event despite this restless state of affairs, and reporters attempted to draw a clear picture of the entire matter. Further, for Japanese society, this case highlighted the way justice-involved youth were treated under juvenile law, as Boy A was sent to a juvenile training school for the purpose of correction and rehabilitation instead of being punished, and his identity was not disclosed to the public or the media due to hopes for his future reintegration into society. The media attempted to correct what they perceived as unfairness caused by the juvenile law, which they interpreted as “overprotecting” the offender. One media source reported Boy A’s picture and real name, and this decision prompted a controversial debate over media ethics since doing so was a violation of juvenile law (Oishi 2005). Although reporting the identity of a justice-involved youth was and still is against the principles of Japanese juvenile law, the justice system could not enforce this provision, and no penalty was given for the violation. Due to the lack of legal consequences, the question of how to report juvenile crimes was left to the judgment of each media outlet (Oishi 2005: 195).

This incident was said to trigger other juvenile crimes. The number of juvenile crimes in 1997 increased by approximately 3,000 cases (from 23,242 to 26,125), particularly in the categories considered heinous, such as robbery, bodily harm, blackmailing, and theft (Ministry of Justice 2021b). At that time, a criminal activity called oyaji-gari, which involves a group of juveniles targeting and robbing middle-aged men, was on the rise (National Police Agency 1997). Within this context, the memory of Boy A persisted, having become a major representation of serious juvenile offenders in Japan. In the public’s eyes, justice-involved youth were inhumane and monstrous by nature and had no possibility of being rehabilitated. This idea intensified when Boy A published his autobiography in 2015. The publication of the autobiography was bitterly attacked by the media, critics, and the victims’ families, who claimed that Boy A intended to profit by flaunting his past acts before the public and that his profit-seeking proved that he had no remorse for his actions (Hisano et al. 2015; Nikkei Shimbun 2015b; Sankei Shimbun 2015, Shukan Bunshun 2016). The father of the victim argued that Boy A should reveal his real name since he was no longer a minor (Shukan Bunshun 2016). Moreover, the family members of the victims severely criticized Boy A for not informing them in advance about the publication, expressing that they felt betrayed and insulted, especially because they thought that he had the opportunity to notify them (Hisano et al. 2015; Nikkei Shimbun 2015b; Sankei Shimbun 2015). The victims’ families protested the publication of the autobiography and requested that the publisher collect all copies from bookstores; the publisher refused their request, and consequently, many bookstores refused to sell the autobiography out of respect for the victims’ families (Nikkei Shimbun 2015b). Subsequently, the vilification of justice-involved youth was widely accepted and disseminated by Japanese society, and justice-involved youth were thought to impulsively commit brutal crimes for no reason or at their convenience. Boy A contributed significantly to forming this image of “juvenile delinquents/offenders” that has deeply pervaded Japanese society.

As in the case of Boy A, and in the general portrayal of justice-involved youth in the 90s, the media plays a critical role in the development of social anxiety and moral panics by using exaggerated and controversial imagery to make events appear more scandalous, thus, amplifying public fear. However, an image of a certain group or category is shaped based on the specific individuals or events included, and it does not entirely represent the group or the disparate voices of its members, despite one voice being conveyed to society as dominant. In Japan, Boy A is recognized as a dominant voice for justice-involved youth, lessening the diversity of delinquents’ voices and eliding the many factors that affect juvenile crime. For instance, many delinquents are survivors of domestic violence, neglect, poverty, and/or school bullying (Abe 2018; Hazama 2018). Additionally, developmental disorders are considered one of the possible compounding causes of delinquent acts (Fujikawa 2009). Thus, some scholars and legal practitioners emphasize the need for early legal or social intervention to prevent juvenile crime (Abe 2018). However, Japanese public perception is formed based on the major discourse of juvenile crime, which often centers on individual problems and misses social problems that would be evident from a holistic view, potentially reflecting a more general failure to consider broader contexts. Resolving this discrepancy would facilitate the public understanding of juvenile crime as a personal problem for the justice-involved youth and promotes conclusions that justify their exclusion from society.

Literature Review

After infamous juvenile crimes occurred consecutively in the 1990s, controversy arose in Japan over whether the juvenile law should be amended in response to public opinion or victims’ lobbying (Ellis and Kyo 2017). The amendments are understood to take a more punitive stance toward justice-involved youth, as legislators and judges began to pay close attention to how the public would react to their judgments. In a principle widely accepted by the global community, the law is formally outside the state’s political process and stands above the general public; moreover, its rituals and conventions serve to keep its activities out of the public eye and away from the force of public criticism (Hall et al. 2013: 36). However, contrary to principle, the cases of the United Kingdom (UK), the US, and Japan suggest an important aspect of how to account for experts, the multiple voices of the public, those affected by the law, as well as those who practice it. For instance, Hall et al. (2013: 37) indicate that, in the UK, the rise in crime was portrayed as an inevitable consequence of “the weakening [of] moral authority,” that the youth were “the group most at risk in this process,” and that violence was the most tangible measure of this vulnerability. After assiduously examining the moral panic phenomenon associated with mugging within an extensive context and from diverse perspectives, Hall et al. (2013) concluded that this phenomenon led to marginalization of and racial prejudice against youth of color, justification of social control by the police, and more severe punishment for juvenile crimes in response to public outcries. They also stated that the judiciary and mass media lay behind a process driving “how the public ‘makes sense’ of the situation, what actions will be found politically acceptable and legitimate, [and] to what consent is given” (Hall et al. 2013: xiii). There is no doubt that the government continuously seeks to gain the support of the public and, accordingly, to either reflect public opinion in policy or manipulate it in support of policy. Conversely, as Hutchinson (2005) pointed out, lawmakers are loath to appear soft on crime since doing so could spell the end of their political careers. However, careful attention observes that public opinion does not necessarily derive from facts, but rather from information that sounds understandable, reasonable, or convincing to the audience.

The evolution of public opinion includes a myriad collection of influences. Official statistics and evidence-based studies clearly prove that the beliefs of the majority of Japanese residents do not reflect the facts regarding juvenile crime; on the contrary, the discussion around amending juvenile law disregarded data and scientific insight and placed value on enacting “public opinion” as it currently existed rather than on correcting public misperceptions. Hence, it is important to discern what consequences may result from policies that are inconsistent with data, scientific insights, and social realities, especially when public opinion formed from misunderstanding and false information implicitly or explicitly influenced legal reform. In this regard, Japan is not unique, as such misunderstandings and misperceptions of juvenile crime are an international phenomenon (Goidel, Freeman and Procopio 2006; Hall et al. 2013; Ruigrok et al. 2016).

As another aspect of public perception on juveniles, some studies (Antolak-Saper 2020; Benekos and Merlo 2008; Bolin, Applegate and Ouellette 2021) examined the adultification phenomenon by questioning the treatment of justice-involved youth under the law. Beneko and Marlo (2008) noted that one sign of the adultification of the juvenile justice system was the increase in youth being tried in criminal courts and incarcerated in adult prisons following the decline in the use of judicial waivers in the US since the mid-1990s. The shift away from adultification policies was seen in 2005 with the decision of Roper v. Simmons, in which the US Supreme Court exempted defendants under the age of 18 from the death penalty and reaffirmed that juveniles are different from adults (Bolin, Applegate and Ouellette 2021). Bolin, Applegate and Ouellette (2021) found that, at the level of the general public, “there tends to be a persistent belief among Americans that juvenile crime is rising, and kids are much worse today than in previous decades” (18), while believing in the importance of rehabilitation with “greatest emphasis on goals oriented toward child saving” (11). Bolin, Applegate and Ouellette (2021) concluded that although they found that the relative majority supports blended sentencing on juveniles, depending on the crime under consideration and the presence of a criminal record, people followed juvenile justice policy in reinforcing the distinction between juveniles and adults.

In the history of juvenile justice, the US and Japan originally adopted the welfare model, whereas Australian youth justice developed separately from adult criminal justice (Antolak-Saper 2020). However, there were some shared experiences among these countries in terms of the “tough on crime” wave, adultification of the juvenile justice system, and media reporting on juvenile crime. Referring to the Victorian State Government’s 2017 reforms of the youth justice system, Antolak-Saper (2020) noted that the implementation of “law and order” reform leads to the adultification of the juvenile justice system, barely addressing the fundamental causes of juvenile crime (i.e., socioeconomic disadvantages, child abuse, or family environment) over which children have little control. According to Antolak-Saper (2020), adultification generally consists of two waves: the “tough on crime” wave, responding to justice-involved youth who committed a serious crime, and the “due process” wave, which recognizes the same rights for justice-involved youths as for adults. The latter, while seemingly reasonable, shows little distinction from the adult criminal justice system (Antolak-Saper 2020).

Adultification based on the combination of these two waves can be seen in Japan’s juvenile justice reforms, which barely maintain the welfare model in their framework. Moreover, in Japanese society, which has an ageing population and declining birthrate, this adultification removes protective interventions and produces more adults who contributes to society. However, there is uncertainty as to whether this adultification policy will continue, advance, or regress in the future, as the government is required to address various issues around the youth, including high suicide rates, poverty, young carers, 2021 child abuse, and school bullying. Therefore, to grasp the power dynamics and fallacies behind such policy decisions—as well as the possible consequences of the adultification policies—it is necessary to study the issues of public understanding of juvenile issues and to propose future directions for the juvenile justice system.

Methodology

Applying the approach of Hall et al. (2013) to depict the relation between repressive state structures, capitalism, and neoliberal globalization, and using secondary data analysis and discourse analysis, this study investigated the emergence of adultification based on the relations between public opinion, the media, and the legislative proceedings through the case of juvenile crime and delinquency. The study particularly aimed to examine the media’s role in forming opinions, the gap between public belief and the facts, and the prevalence of misconceptions. Secondary data were drawn from both official government statistics, such as the police, as well as data from nonprofit organizations; these sources were used to analyze public opinion and perceptions toward juvenile law and crime. Discourse analysis was conducted to explore how these perceptions and misperceptions were implicitly brought into the debate on juvenile law reform. Public opinion and perceptions are generally vague, elusive, and often speculative, and there is no established method to capture them accurately. However, the purpose of this study is to document not only the forces influencing public opinion and perceptions, but also those surrounding childhood debates. Though challenging, this study attempts to provide some insight into neoliberal trends and power dynamics in the Japanese context.

Secondary Data Analysis: Official Statistics

There is a significant gap between actual data and public opinion on juvenile crime. For instance, the Japanese government conducted a public opinion poll in 2010 and 2015 regarding juvenile crime. The 2015 result indicated that 78.6% of a total of 1,773 respondents thought that juvenile crime was going up, and only 2.5% believed the number of youth crimes was on the decline (Cabinet Office, Government of Japan 2015). Compared to the survey in 2010, more respondents answered that juvenile crime is on the rise in 2015 (Figure 1). On the trend of juvenile delinquency, about half of the respondents—47.6% in 2010 and 45.9% in 2015—answered that the number of delinquents involved in vicious and violent acts was increasing (Cabinet Office, Government of Japan 2015). The Kanagawa Newspaper documented the critical fact that in 2015 almost 80% of respondents believed that serious juvenile crime was increasing, and about half of them assumed that heinous juvenile crime was also on the rise (Kawashima 2019).

Figure 1: The public opinion of juvenile crime

(Based on The Public Opinion Poll on Juvenile Crime 2010 and 2015 by the Cabinet Office, Government of Japan)

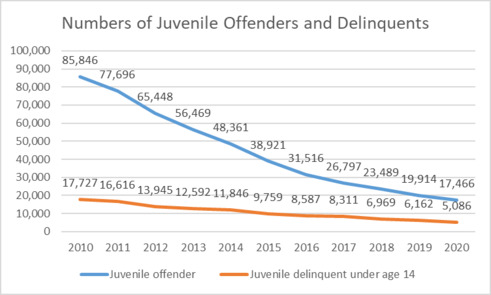

However, statistical data from the White Paper on Crime 2021 by the Ministry of Justice (Figures 2 and 3) and the Overview of Juvenile Probation and Protection by the National Police Agency in 2022 (Figure 4) thoroughly rebut this public belief. Indeed, both the total number of justice-involved youth and repeat offenders is decreasing (Figures 2 and 3). The data on juvenile offenses by type of crime indicate that felony and violent crimes have been decreasing, while intellectual and moral crimes are staying the same (Figure 4). Larceny accounts for more than half of total juvenile offenses, although it is also on the decline. This result clarifies that justice-involved youth were far more likely to commit misdemeanors than felonious or violent crimes, and accordingly, the data do not support the common assumption that justice-involved youth are becoming more dangerous. Moreover, the 2022 data from the National Police Agency suggest that the ratio of justice-involved youth to the total juvenile population has fallen in the past 10 years (Figure 5); factors besides the decline of the juvenile population likely explain the decrease of justice-involved youth such as stable social control and successful rehabilitation and social reintegration of justice-involved youth. Overall, these data exculpate specific issues of parenthood and highlight current trends and characteristics of justice-involved youth and the need to focus on the socioeconomic aspects of crime to address the problem.

Figure 2: Numbers of juvenile offenders and delinquents

(Based on White Paper on Crime 2021 by the Ministry of Justice in Japan)

Figure 3: Juvenile offenders and the ratio of repeat offenders

(Based on White Paper on Crime 2021 by the Ministry of Justice in Japan)

Figure 4: Offense types and numbers

(Based on Overview of Juvenile Probation and Protection by National Police Agency in 2022)

Note: 1=Juvenile offenders 2=Juveniles 14-19

Figure 5: Percentage of juvenile offenders in total juvenile population age 14-19

(Based on Overview of Juvenile Probation and Protection by National Police Agency in 2022)

As described earlier, the two types of data above clearly indicate that public opinion does not reflect the actual data and that there is a gap between the two. However, this gap also implies another problem: the lack of knowledge and interest in youth issues. The Nippon Foundation conducted a public opinion poll regarding the amendment of the Juvenile Act in March 2021, targeting 1,000 people aged 17 to 19. The results revealed that 39.8% of the respondents had no idea about the proposed amendment to the Juvenile Act, 45.6% vaguely knew, and only 14.6% were aware of it. When asked about the new framework for “Specified Juveniles (Tokutei Shōnen)” to expand the type of crimes subject to adult courts proceedings, 58.2% agreed with the expansion. However, among those who agreed with the expansion, only 35.7% believed that it would be effective in reducing the number of crimes committed (25.4%) or deterring recidivism (10.3%). Also, 55.0% agreed with the statement “even juveniles need to fulfill the social responsibility when they commit a crime.” These results suggest that the majority of young people were neither interested in nor aware of the amendment, that about 20% of the total respondents believed in the effectiveness of repressive law as social control, and that about 30% expected justice-involved youth to hold social responsibility for their acts.

Hence, these data conclude that public perception of juvenile crime is not formed based on scientific or empirical data and actual statistics; instead, perception might be largely driven by the stereotypical image of delinquents reinforced by the media. For instance, there is a common narrative, reported by the media, that the ratio of repeat offenders is increasing, and the public believes it to be true (Yanai 2016). This narrative derives from that data that, while the ratio of repeat offenders has slowly increased by 15% in the past 20 years (Figure 3), the overall number of justice-involved youth as well as the overall number of youth with repeated justice interactions both declined, resulting in the appearance of greater recidivism because of the smaller sample size. However, Okabe (2015) pointed out that this data itself is debatable, as the ratio of repeat offenders is not the same as the recidivism rate, and there is little or no data on recidivism in Japan, especially in the area of juvenile delinquency. The media extract this particular data point from other related data, including the frequency and nature of juvenile crime and delinquency, and report that “recidivism gets higher.” Yanai (2016) suggested that such misleading reports are common in the major media corporations in Japan, including Nippon Hoso Kyokai, Asahi Shimbun, and Yomiuri Shimbun. This narrative is apparently shaped from a fragment of the entire picture, missing the critical points: the overall numbers of juvenile offenses and justice-involved youth are declining, and there is no evidence to suggest the recidivism rate of justice-involved juveniles is necessarily on the rise.

It is problematic and often criticized as duplicitous for the media to focus on fragmentary information, disregarding the larger context, because it misleads and misinforms the general public. More importantly, this process has intentionally shifted the perceived locus of the problem from society to the individual, giving the impression that juvenile crime is due to personal and individual issues. In addition to the impact of violent imagery on public sentiment, such misleading reporting has contributed to public misunderstanding and discrimination against justice-involved youth, resulting in a predominant trend toward neoliberal thinking. Having examined the relations among the media reporting, opinion formation, the discrepancies between public belief and the facts, and the prevalence of misconceptions, this study next explores how these factors affect the debate on juvenile law reform and the policymaking process.

Discourse Analysis: Debates on Amendment of Juvenile Law and Legal Reform

In 2015, one juvenile crime caught the public’s attention, and the then-chairman of the Liberal Democratic Party’s Policy Research Council (Jimin Tōh) declared to the press that “juvenile crime is becoming extremely brutal. It will be necessary to consider whether there needs to be a change on the current Juvenile law for crime prevention” (Nikkei Shimbun 2015a). Among the other responses, this comment seemingly triggered an open debate. The Japanese government considered lowering the upper age of juvenile law to match the Civil Code in response to public support for amending the juvenile law toward a more punitive stance (Mainichi Shimbun 2019). In 2017, in response to a government request, the Legislative Council of the Ministry of Justice (Hōsei Shingikai) began considering such an amendment to the Juvenile Act (Mainichi Shimbun 2019). Lowering the age of criminal majority from 20 to 18 in Japan (Shōnen Hō nenrei hikisage) was the main theme of the discussion, and it took three years to reach a conclusion regarding the amendment. In May 2021, the debate concluded with a decision that a new legal framework would be established and enacted for justice-involved youth from 18 to 19 to become effective in 2022 (Ito 2021), instead of lowering the upper age of criminal majority. However, this amendment is still considered, from the process of its discussion, as merely the first step toward the original goal of lowering the age in the future. Under this framework, offenders between the ages of 18 and 19 are defined as “Specified Delinquent (Tokutei Shōnen)” and will be tried either as a juvenile or as an adult offender, depending on the severity of the offense. This policy expands the cases in adult courts for offenders aged 18 and 19. Moreover, there are other changes in the amendments; for instance, the prohibition on reporting minors’ real names is removed for specified delinquents who commit serious crimes and are to be tried in adult courts. The Ministry of Justice (2021a) offers the following explanation for lifting the prohibition:

It is considered appropriate to prosecute in open court and pursue criminal responsibility for specified juveniles who have been held responsible for their acts due to the lowering of the voting age and the age of majority under the Civil Code and to subject them to social criticism and commentary.

In addition, recent changes lowered the age of pre-delinquent offense to 17, meaning that those over 18 are now considered adults and, therefore, no longer eligible for protective intervention. Thus, this amendment forces individuals over the age of 18 into responsible adulthood.

However, there remains significant doubt as to the necessity of these legal changes, especially considering the previous juvenile law’s effectiveness in the rehabilitation of justice-involved youth. Experts, including lawyers and academics, expressed serious concerns that this amendment may produce potential negative consequences, such as higher recidivism rates, particularly among justice-involved youth between 18 and 19 who lose educational and rehabilitative opportunities as well as job opportunities due to real name reporting (Katayama et al. 2021; Kuzuno, Takeuchi and Honjo 2020). They also argued that education is more effective in rehabilitation rather than punishment and prison labor and, therefore, should be prioritized since scientific research data and fact-based reasoning have not indicated that children today are any more mature than they used to be (Katayama et al. 2021; Kuzuno, Takeuchi and Honjo 2020).

These discussions revived recurrent issues about the definition of minors in the justice system and measures for holding minors accountable. In the Japanese justice system, minors have gradually emerged as a responsible entity through previous amendments to the juvenile law. Since the 1990s, cases involving juveniles have been continuously reported in Japan’s media, capturing public attention and leading to the establishment of new juvenile-related prostitution and pornography laws in 1999 and an amendment to juvenile law in 2000. The legal system’s approach to minors has been under reconsideration since then.

The amendments of 2000 introduced new systems: prosecutor participation, three judges, and victims’ impact statements; they also lowered the minimum age required for minors to be transferred to adult court from 16 to 14, depending on the crime (Takumi 2017). This amendment was the first overhaul of juvenile law since its implementation in 1949 (enacted in 1948) when American-inspired discourse was first adopted in the US-dominated postwar Japanese system. This change prompted three other amendments of juvenile law in 2007, 2008, and 2014. The 2007 amendment lowered the minimum age for minors to be sent to juvenile training schools from 14 to 12, and, in the third amendment in 2008, the Victim Participation System was introduced through the revision of the Code of Criminal Procedure in juvenile justice (Takumi 2017). In the Victim Participation System, victims and bereaved family members in certain cases are allowed to participate in the proceedings by attending the trial and questioning the accused (Ministry of Justice n.d.). This system raised concerns about justice-involved youth and the family court system, which centers on rehabilitation. The 2014 amendment raised the maximum prison term from 15 to 20 years for minors who commit a felonious crime under 18, taking into account the balance with the Penal Code (Takeuchi 2013: 187). According to Takeuchi (2013: 188), in the process of these four amendments, a new structure has been established, one where prosecutors are deeply involved in legislation as a traditional legal authority and where the representatives of victims’ organizations are actively involved in the legislative process. As such, the amendments are understood to be instilling a newly punitive stance toward justice-involved youth, following public opinion (Ellis and Kyo 2017). In other words, taking a punitive stance toward young potential offenders implies blurring the boundary between minor and adult or pushing the liminal space toward a more adult domain.

In 2017, in response to a government request, the Legislative Council of the Ministry of Justice began discussing amending the Juvenile Act, including lowering the age of criminal majority from 20 to 18 (Mainichi Shimbun 2019). If the system determined that there was a good possibility for rehabilitation, as defined within prevailing concepts of juvenile delinquency, the justice-involved youth was “treated” rather than penalized. In the most recent discussion of the amendment of juvenile law, not only legal experts and academics but also the members of the Legislative Council of the Ministry of Justice (2020b: 11) considered that the juvenile law is effective for the rehabilitation of the justice-involved youth. Therefore, strong objections and concerns were raised to this amendment, charging that lowering the upper age would lead to higher recidivism (Katayama et al. 2021; Kuzuno, Takeuchi and Honjo 2020).

According to a member of the Legislative Council of the Ministry of Justice, the debate over the amendment remained within the theoretical framework and did not reach its practical goal because it originated with the impact of the Civil Code amendment (Kawaide 2021: 34). This limitation on the debate could also be read by the statement of another member of the council that, “since this is a legal discussion, priority should be placed on normative evaluation as a legal concept, rather than placing undue emphasis on social realities and biological perspectives” (Ministry of Justice 2020a: 16). However, this amendment was also justified based on policy judgment and consistency with the new Civil Code that defined juveniles between the ages of 18 and 19 as individuals with autonomous decision-making capacity, expecting them to participate in social activities and play a role as civic members from an early stage (Kawaide 2021: 37). In this discussion, juveniles’ maturity level and mental growth process were not considered the main concerns, ceding place to concerns over how those defined as adults under the new Civil Code should be treated in the overall legal system (Kawaide 2021: 37). While the minimum age for drinking, smoking, and gambling remains 20 because these activities are detrimental to health during the physical growth process, the scientific insights, including perspectives on the growth process of the mind and maturity, did not find a place in the juvenile justice system. Rather, policy judgment was heavily weighted, and gaining “public understanding” was a main concern of the discussion (Kawaide 2021: 49). Thus, gaining public acceptance of legal reform was prioritized over clearing up the existing public misunderstanding on juvenile delinquency. This amendment was apparently promoted as a political and policy matter, rather than a legal necessity. That said, the discussion did not focus on the actual situation of juveniles aged 18 and 19 who would be affected most by this amendment (except for the victims). By lowering the age of majority from 20 to 18 in the Civil Code, they are expected or even pressured to become individuals with autonomous decision-making capacity and to contribute to society. However, as the opponents of the amendment recite, recent neuroscientific findings have proved the opposite about the maturation process (Arain et al. 2013), and it is questionable whether the legal change will have a positive effect on their mental development.

In the 1970s in the UK, a judge justified the punitive stance on youth violent crimes, addressing the need for courts to be sensitive to public opinion and not to lose public respect and confidence (Hall et al. 2013: 37). Although gaining public respect and understanding is a vital prerequisite for the state and the legal system, legal reform needs to be conducted in anticipation of the possible consequences of its policies. In terms of crime deterrence, several studies in the US (Harding et al. 2019; Redding 2010) proved that severe punishment, including imprisonment, does not deter future crimes. Specifically, Redding (2010) found that transferring justice-involved youth to adult prisons and treating them as adult inmates promotes recidivism and harms their mental health. These studies elucidate that a punitive stance toward juvenile crime produces negative outcomes because there is no solid evidence to indicate that punitive intervention is effective in crime prevention, especially for justice-involved youth who are in the process of maturing. The limitation of the study is its lack of data, such as the real voices of former justice-involved juveniles and those around them, and it is essential to investigate whether and how this legal reform will change the attitudes of juvenile delinquents and what the consequences of this amendment will be. Such insights will likely be instrumental in guiding research and policymaking on the global stage, both in Japan and internationally.

Conclusion

In the midst of a major social upheaval, several amendments related to juvenile law have been enacted over the past 20 years. The Juvenile Act is one of the measures that establishes a boundary between adults and children. Hence, the amendments and public misunderstanding of the current situation ultimately led to the wave of adultification that changed in the concepts of childhood and of children’s rights and responsibilities; children in Japan came to be considered more responsible, autonomous, and independent individuals than in previous years. This study explained that adultification did not voluntarily arise from children themselves but was, intentionally or unintentionally, conducted by external forces, particularly the media and the central government. Consequently, children are forced to become adults when they should still be educated and supported by society, and they are pushed to accept responsibility for their actions and are expected to behave well and control their emotions.

The 2022 amendment to the Juvenile Act sets a five-year period of observation. This study argues that this amendment heavily focused on the policy judgment perspectives and expectations of an imagined, ideal young adult with autonomous decision-making, while downplaying scientific insights, data, and the voices of delinquents or reformed delinquents. The next five years will require more empirical research on the lived experiences and voices of those affected by this amendment, including the young and juvenile delinquents in their teens and former delinquents before and after this legal transition.

Correspondence: Dr Yoshie Udagawa, Project Researcher, Tokyo College, The University of Tokyo, Japan. yoshieudagawa@hotmail.com

References

Abe K (2018) Relationship between child abuse and misdemeanor. Studies in Human Sciences 14(1): 167–194.

Antolak-Saper N (2020) The adultification of the youth justice system: The Victorian experience. Law in Context 37(1): 99–113. https://doi.org/10.26826/law-in-context.v37i1.118

Arain M, Haque M, Johal L, Mathur P, Nel W, Rais A, Sandhu R and Sharma S (2013) Maturation of the adolescent brain. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment 9: 449–461. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S39776

Asahi Shimbun (1997) Suspicious middle-aged man took on a life of its own: The media reports on the Kobe Sakakibara incident. 30 June.

Benekos PJ and Merlo AV (2008) Juvenile justice: The legacy of punitive policy. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice 6(1): 28–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541204007308423

Bolin RM, Applegate BK and Ouellette HM (2021) Americans’ opinions on juvenile justice: Preferred aims, beliefs about juveniles, and blended sentencing. Crime & Delinquency 67(2): 262–286. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128719890273

Cabinet Office, Government of Japan (2015) Public opinion survey report on juvenile delinquency: Overview of the survey results. https://survey.gov-online.go.jp/h27/h27-shounenhikou/2-1.html

Doi T (2003) Disappearance of delinquent boys: A mythology of individual and juvenile crimes. Tokyo: Shinzansha.

Ellis T and Kyo A (2017) Reassessing juvenile justice in Japan: Net widening or diversion? The Asia-Pacific Journal 15(9): 1–13.

Fujikawa Y (2009) Developmental disabilities and juvenile delinquency. Japanese Journal of Studies on Disability and Difficulty 37(1): 39–45.

Goidel RK, Freeman CM and Procopio ST (2006) The impact of television viewing on perceptions of juvenile crime. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 50(1): 119–139. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15506878jobem5001_7

Hall S (2011) The march of the neoliberals. The Guardian, 13 September. https://theguardian.com/politics/2011/sep/12/march-of-the-neoliberals

Hall S, Critcher C, Jefferson T, Clark J and Roberts B (2013) Policing the crisis: Mugging, the state and law and order. 2nd ed. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

Harding DJ, Morenoff JD, Nguyen AP, Bushway SD and Binswanger IA (2019) A natural experiment study of the effects of imprisonment on violence in the community. Nature Human Behavior 3(5): 671–677. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-019-0604-8

Harvey D (2005) A brief history of neoliberalism. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hazama K (2018) The relationship between child maltreatment and delinquency. Journal of Guidance and Education 35: 53–63.

Hisada K (2021) Hong Kong: Strengthened communist rule. Interview with Ako Tomoko, Professor of the University of Tokyo. Asahi Shimbun, 27 April.

Hisano H, Komazaki H, Kamiashi S, Aoshima A and Kusakabe S (2015) Kobe child slaughter memories ‘Zekka’: Publication by Boy A stirs up emotions of the bereaved families. Mainichi Shimbun, 30 June. https://mainichi.jp/articles/20150629/org/00m/040/006000c

Hutchinson EO (2005) No-parole sentences hurt black teens. AlterNet, 16 November. https://www.alternet.org/2005/11/no-parole_sentences_hurt_black_teens/

Ito K (2021) Stiffer penalties under revised juvenile law from April 2022. Asahi Shimbun, 22 May. https://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/14355851.

Japan Educational Press (2019) Voting rights lowered to 18 from 20, but young people are still a long way from politics. 16 October. https://www.kyoiku-press.com/post-208480/

Katayama T, Ito Y, Kawamura Y, Sasaki H, Sasaki M, Niikura O and Hatta J eds. (2021) Can 18- and 19-year-old delinquents be rehabilitated by severe punishment? Tokyo: Gendai Jinbunsha.

Kawaide T (2021) Lowering the age of adulthood in juvenile law. The University of Tokyo Law Review 15(1): 32–50.

Kawashima H (2019) At a crossroads in the juvenile law debate: Violent news reports and public opinion swinging for harsher punishment. Kanagawa Shimbun, 26 April. https://www.kanaloco.jp/news/social/case/entry-162329.html

Kuzuno H, Takeuchi K and Honjo T, eds (2020) Comprehensive criticism of lowering the upper age limit of the Juvenile Act. Tokyo: Gendai Jinbunsha.

Mainichi Shimbun (1997) Provocative murder: Sakakibara incident. The expression of ‘compulsory education’ comes from resentment? Expert analyzes. 7 June.

Mainichi Shimbun (2017) Editorial: Limiting the adverse effects of lowering the legal age of adulthood. 22 August. https://mainichi.jp/english/articles/20170822/p2a/00m/0na/019000c

Mainichi Shimbun (2019) Inquiry: Discussion on amendment of Juvenile Act reaches consensus: Ministry of Justice submits a negotiated proposal, either rehabilitation or more punitive treatments. 25 December.

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (2008) Training materials for practical guidance practitioners for specific health guidance: Lifestyle guidance and mental health care. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/bunya/shakaihosho/iryouseido01/info03k.html

Ministry of Justice (n.d.) Victim support related to juvenile proceedings. https://www.moj.go.jp/keiji1/keiji_keiji11-5.html

Ministry of Justice (2020a) The 28th meeting minutes of the Legislative Council, the subcommittee on juvenile and criminal law (relating to juvenile age and treatment of offenders). 6 August. https://www.moj.go.jp/keiji1/keiji14_00013.html

Ministry of Justice (2020b) The 29th meeting minutes of the Legislative Council, the subcommittee on juvenile and criminal law (relating to juvenile age and treatment of offenders). 9 September. https://www.moj.go.jp/keiji1/keiji14_00014.html

Ministry of Justice (2021a) Juvenile Act will change!

https://www.moj.go.jp/keiji1/keiji14_00015.html

Ministry of Justice (2021b) White Paper on Crime.

https://hakusyo1.moj.go.jp/jp/68/nfm/mokuji.html

Nakajima T (2022) What is ‘adult’? Preparatory period to ‘become a person who protects oneself by law’: Interview with Murase Manabu, the child culture scholar. Asahi Shimbun, 22 April.

National Conference of State Legislatures (2015) Raising the age of juvenile court jurisdiction. NCSL 23(39). https://www.ncsl.org/research/civil-and-criminal- justice/raising-the-age-of-juvenile-court-jurisdiction.aspx

National Police Agency (1997) Section II: Prevention of juvenile delinquency and youth development. White Paper on Police. https://www.npa.go.jp/hakusyo/h09/h090302.html

National Police Agency (2022) Overview of juvenile probation and protection. https://www.npa.go.jp/publications/statistics/safetylife/syonen.html

Nikkei Shimbun (2015a) Ruling party mentions revision of Juvenile Act in response to Kawasaki incident. 27 February. https://www.nikkei.com/article/DGXLASFS27H3Q_X20C15A2000000/

Nikkei Shimbun (2015b) Sakakibara incident: Boy A’s autobiography continues to be reprinted. 18 June. https://www.nikkei.com/article/DGXLASDG17HAA_Y5A610C1000000/

Oishi Y (2005) Law and ethics in media. Kyoto: Sagano Shoin.

Okabe T (2015) Juvenile delinquency in Japan from quantitative analysis: Focusing on juvenile recidivism. Keisei 126(6): 46-59.

Postman N (1994) The disappearance of childhood. New York: Vintage Books.

Redding RE (2010) Juvenile transfer laws: An effective deterrent to juvenile delinquency? https://ojjdp.ojp.gov/library/publications/juvenile-transfer-laws-effective-deterrent-delinquency

Ruigrok N, van Atteveldt W, Gagestein S and Jacobi C (2017) Media and juvenile delinquency: A study into the relationship between journalists, politics, and public. Journalism 18(7): 907–925. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884916636143

Sankei Shimbun (2015) Atsushi Haji’s father, Mamoru, ‘my son was killed twice’ and ‘anonymous publishing was not fair’. 29 June. https://www.sankei.com/article/20150629-QT6YAALGYJKFLHUICZ6MXUVDYU/

Schmidt EP, Rap SE and Liefaard T (2021) Young adults in the justice system: The interplay between scientific insights, legal reform and implementation in practice in the Netherlands. Youth Justice 21(2): 172–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473225419897316

Shukan Bunshun (2016) A direct hit on former Boy A! ‘You risked your life to come here, did not you? I’ll remember your face!’ 58(8): 22–30.

Tadokoro R (2022) Protect 18- and 19-year-olds from being forced to perform in pornographic films. Mainichi Shimbun, 23 March. https://mainichi.jp/articles/20220323/k00/00m/010/317000c

Takao S (1997) Child network which drove Boy A into a corner and investigation note: Important lessons from the Sakakibara incident. Shukan Post, 18 July.

Takeuchi K (2013) An overview of amendments of the juvenile law and Juvenile Training School Act. Japanese Journal of Sociological Criminology 38: 186–192. https://doi.org/10.20621/jjscrim.38.0_186

Takumi M (2017) Debate over lowering the applicable age of the Juvenile Act. Investigation and Information: Issue Brief No. 963. https://dl.ndl.go.jp/view/download/digidepo_10356511_po_0963.pdf?contentNo=1

Tanaka S (2021) Distanced? The youth and politics. Asahi Shimbun, 6 November.

The Nippon Foundation (2021) 18-year-old attitude survey: ‘36th revision of the Juvenile Act’. https://www.nippon-foundation.or.jp/app/uploads/2021/04/new_pr_20210426_2.pdf

Turner J (2014) Being young in the age of globalization: A look at recent literature on neoliberalism’s effects on youth. Social Justice 41(4): 8–22. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24871272

Yanai H (2016) The common misinformation of ‘the highest recidivism in Japan’: White Paper continues to be misleading. Yahoo! Japan, 15 November. https://news.yahoo.co.jp/byline/yanaihitofumi/20161115-00064334/

Yoneda Y (2021) Young people targeted by investment multilevel marketing traps. Asahi Shimbun, 9 November.

Treaties cited

Convention on the Rights of the Child 1990.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/IntJlCrimJustSocDem/2023/21.html