|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy |

Penalty Notices, Policing and Executive Discretion: Examining the Nature and Effects of Criminalisation in the COVID-19 Pandemic Response

Sean Mabin

UNSW Sydney, Australia

Abstract

Police-issued penalty notices were heavily relied upon to deter and punish breaches of emergency restrictions in the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. This article critically examines the use of penalty notices in this context and explores the implications for our understanding of contemporary criminalisation practices. The origins, drivers and existing theoretical accounts of penalty notice regimes are first examined. Attention is drawn to their often overlooked disruptive and punitive effects in the domains of public order policing and administrative fines enforcement. Against this background, a case study of the COVID-19 Delta variant outbreak in New South Wales, Australia is presented. This case study exemplifies the substantial discretionary, penal and quasi-judicial functions ceded to police and state debt recovery agencies through modern penalty notice regimes. It exemplifies the ‘chameleon criminalisation’ enacted by penalty notices. Despite appearing transactional and benign, ‘on-the-spot’ fines subtly expand executive power and disproportionately penalise the most vulnerable and marginalised.

Keywords: Penalty notices; fines; policing; pandemic; criminalisation.

Introduction

Police-issued penalty notices (commonly known as ‘on-the-spot’ fines) were used extensively to enforce emergency restrictions throughout the global Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. This article critically examines the use of penalty notices as a means of addressing a public health crisis and explores the implications of this mode of criminalisation. It adopts the Australian ‘contextual’ approach to criminalisation research to do so. This scholarly tradition is committed to the historicised, context-specific and empirical analysis of the multifaceted phenomenon of criminalisation. In this vein, the article reflects upon the exponential rise in the use penalty notices alongside the archetypal criminal process in Western states. The dominant conception of penalty notices as an administrative ‘innovation’ apposite to modern neoliberal and consumer societies is critiqued. This view is shown to obscure the punitive and disruptive effects of penalty notices both in the context of ‘front-end’ public order policing and ‘back-end’ administrative fines enforcement.

Against this background, the article then considers a case study of the use of penalty notices during the pandemic. The case study draws together an analysis of emergency laws, enforcement data and policy discourse relevant to the COVID-19 Delta variant outbreak in New South Wales (NSW), Australia (June to November 2021). It provides valuable insights into the operation and implications of police-led and penalty notice-centred criminalisation. Penalty notices are shown to vest significant discretionary, penal and quasi-judicial power in police and state debt recovery agencies. This allows governments and executive agencies to respond to urgent policy demands decisively and flexibly. Nonetheless, it is argued that policymakers should approach penalty notices with considerable caution. Despite appearing transactional and benign, ‘on-the-spot’ fines minimise oversight of the exercise of executive discretion and disproportionately effect the most vulnerable and marginalised.

The Australian Contextual Approach to Criminalisation Research

The role of criminal law as a public policy tool is the subject of extensive theoretical scholarship. Macro-theories of criminalisation identify a ‘punitive turn’ in criminal justice policies across the Western world from the late twentieth century (Lacey 2009: 939; see also Bell 2011; Garland 2002; Husak 2008; Simon 2007). Discomfort at the reactive and broad use of criminal law by policymakers animates much of the criminalisation literature. Legal philosophical theorists have developed various criteria to assist in principled and restrained criminal law-making (McNamara 2015: 34). The capacity for these frameworks to exert normative or political influence is weakened by their narrow focus on ‘the logical, moral and ethical coherence or desirability’ of philosophical theories and doctrine (Brown 2013: 609). They overlook the cultural and historical contingency of criminal justice: a social construction whose instrumental functions are rarely as significant as its expressive function in a specific context (Brown 2013: 620–621).

The Australian ‘contextual’ approach to criminalisation research contends that specific accounts of when, how and why criminalisation is deployed in specific socio-political contexts must instead form the basis of normative theorising (McNamara 2015: 34, 37). As Hogg (1983: 12) explains:

If the system of criminal justice is a social construction then the way to proceed if we are to change it, is not by imposing some logic upon it from above, which in turn serves to bolster it, but by dissecting it from below: to analyse the practices which constitute it as a field of power, their sources, effects, and the myriad networks of power and knowledge they enter.

This article follows the scholarly tradition of contextualised criminalisation research that ‘engage[s] specifically, and deeply, with particular sites or “moments” of criminalisation’ (McNamara 2015: 37). The ‘thick’ conception of criminalisation endorsed by McNamara (2015: 39–42) is adopted. This incorporates the formal creation of criminal offences, as well as ‘operational dimensions’ of criminalisation, including enforcement practices; processes of criminal adjudication, including defences and procedural safeguards; and the operation of penal and regulatory regimes. Scholarship employing the Australian contextual approach has grappled with diverse forms of regulation within the field of criminal law and justice, highlighting those traditionally considered trivial and unworthy of scholarly analysis (Brown et al. 2020: 36; Quilter and McNamara 2018: 1). It is in this vein that the present article evaluates the under-scrutinised evolution of penalty notices and interrogates the implications for contemporary criminal justice.

The Rise of the Penalty Notice

The penalty notice has been the most frequently imposed sanction in Australia and many overseas jurisdictions for several decades (Fox 1995: 1; Quilter and Hogg 2018: 13). Although commonly referred to as an ‘on-the-spot’ fine, a penalty notice does not impose an immediately payable financial sanction. Instead, it requires the recipient to pay a fixed amount within a prescribed period, except if the recipient elects to challenge the matter in court (e.g., Fines Act 1996 (NSW) s 20). The issuing authority need not detail the particulars of the alleged offence or prove its elements for enforcement action to be taken against the recipient (Methven 2019: 76). In most Australian jurisdictions, responsibility for overdue fines enforcement has been withdrawn from the judiciary and vested in agencies outside the ‘traditional’ criminal justice system. These agencies administer sanctions to prompt defaulting fine recipients to make repayments. They may also review the validity of penalty notices and exercise a wide range of powers to reduce or vary outstanding fines debt (Quilter and Hogg 2018: 17).

Historical Background

Monetary sanctions have featured in Anglo-American systems of criminal justice for many centuries (Einat 2014). In the twentieth century, the use of fines widely overtook sentences of short-term imprisonment. However, a number of jurisdictions, notably including the United States, doubted the correctional value of fines and maintained high rates of imprisonment (Einat 2014: 2150–2153). The role of the fine escalated dramatically from the mid-twentieth century with the introduction of penalty notice regimes. Australian legislatures first authorised the use of fixed penalty notices in the late 1930s to counter the so-called ‘parking problem’ in urban centres (O’Malley 2010a: 374–375). The scope of penalty notice regimes was extended from the 1960s onwards to include a wider range of motor vehicle–related offences (see Fox 1995: ch 3). It was in this period that the penalty notice system assumed its modern form, including ‘reverse-onus provisions, an “opting out” assumption with respect to formal hearings and disincentives to “opt-in”—notably administration fees and higher penalties’ (O’Malley 2010a: 375). The responsibility for fines enforcement was transferred from the courts to administrative agencies in most jurisdictions from 1984 onwards (Fox 1995: 33).

Successive state and territory governments progressively widened the application of penalty notice schemes to cover a diverse range of offence types. In NSW, approximately 97 legislative instruments authorise the use of penalty notices to enforce some 17,000 offences (NSW Sentencing Council 2006: 76). Technological innovations, including speed and red-light cameras, have increasingly automated the detection and prosecution of a large range of penalty notice offences (Fox 1995: 9-10; Quilter and Hogg 2018: 13). Penalty notices have consequently been issued on a mass scale. Indeed, the agency responsible for fines administration in NSW (Revenue NSW) has processed an average of 3.1 million fines worth $827 million in each financial year since 2017–18 (Revenue NSW 2022c).

The use of the penalty notice was extended beyond so-called ‘regulatory’ infringements and into the realm of ‘real’ crime with the emergence of criminal infringement notice (CIN) schemes across all Australian jurisdictions (Methven 2019: 74). NSW first piloted a CIN scheme in 2002 for offences including common assault, low-level property and public order crimes (NSW Ombudsman 2009: 7). A CIN scheme was entrenched state-wide in 2007 following evaluations by the NSW Ombudsman and NSW Sentencing Council (NSW Ombudsman 2005; NSW Sentencing Council 2006). These evaluations concluded that the trials produced considerable cost and time savings but raised a number of concerns, including inadequate judicial and public oversight, police training and procedural safeguards. NSW Police currently have the power to issue a CIN to adults suspected of committing one of eight prescribed offences (Criminal Procedure Act 1986 (NSW) ch 7 pt 3; Criminal Procedure Regulation 2017 (NSW) sch 4). Over 9,000 CINs were issued each year in NSW before the onset of the pandemic in 2020 (Revenue NSW 2022b).

Attractions of the Penalty Notice Regime

The rapid growth of penalty notice schemes was influenced by neoliberal logic in policymaking from the late twentieth century. By combining ‘in one regulatory act the judgment of guilt and the sentence’, penalty notices streamline the administration of criminal justice (O’Malley 1984: 36). They are a relatively cheap sanction to issue, provide a source of state revenue and deliver a form of punishment that causes limited disruption to the livelihood and productivity of pecunious recipients (Quilter and Hogg 2018: 12–13). The penalty notice system also deters recipients from seeking judicial review of their penalty (NSW Law Reform Commission [NSWLRC] 2012: 29). Those who do so are liable to a higher maximum penalty, the possibility of a recorded conviction and the prospect of expending significant time and resources (Methven 2019: 77; Quilter and Hogg 2018: 12). Methven has shown that ‘primary definers’ of criminal justice policy rely heavily on neoliberal discourses to justify the use of penalty notice regimes (Methven 2019; 2020). Focusing on the introduction of CINs in Western Australia, Methven traces how politicians and police devalue due process principles and individualised justice as sources of needless cost, delay and complexity. The apparent simplicity and efficiency of the penalty notice is emphasised to legitimise and distract from the abrogation of procedural safeguards and judicial oversight.

O’Malley (2009a; 2009b; 2010a; 2010b) provides a compelling theoretical account of why the penalty notice (in his terminology, the ‘modern regulatory fine’) was embraced as a vehicle for diffusing neoliberal ideals in the administration of criminal justice. O’Malley posits that the rapid growth of the penalty notice is linked to the rise of the ‘consumer society’ from the post-war era. Broad-based wealth caused what O’Malley (2009a: 164) terms the ‘only money’ effect; that is, a downgrading of the social significance of financial sanctions. Fines came to represent a routine ‘cost’ of existing in the transactional consumer society; indistinguishable from the broader array of taxes, licences and commodity prices levied on citizens (O’Malley 2009a: 95–96; 2009b: 77). O’Malley (2009a: 163; 2010b: 799) suggests the apparent triviality of monetary penalties in consumer societies is what has permitted penalty notice regimes to radically reconfigure the criminal process without agitating liberal concerns for individual rights. O’Malley (2010a: 368) further observes that penalty notice regimes transform criminal justice into a ‘monetised risk-management system’ by specifying a literal ‘price’ of crime. The value of these fixed ‘prices’ are calculated to reduce the volume of unwanted behaviour without regard to the means or mitigating circumstances of individuals (O’Malley 2010a: 376). In tandem with digital technologies, penalty notice systems further depersonalise and automate the regulation of ‘dividuals’, such as the notional ‘driver’, ‘public transport user’ or ‘licensee’. This form of what O’Malley terms ‘simulated governance’ manages risk and deviance while causing ‘as little disturbance as possible to the circulation of valued bodies, utilities and things’ in the consumer society (O’Malley 2010b: 796; see also Pratt 2020).

Penalty Notices: Transactional or Punitive?

The perception that the penalty notice is an efficient, transactional and non-intrusive sanction has gained widespread currency. This depiction of the penalty notice is perpetuated in neoliberal discourses of primary definers, as identified by Methven, and underpins the foregoing theoretical account developed by O’Malley. However, a closer analysis of the operation of the penalty notice system, in the domains of public order policing and ‘administrative’ fines enforcement, weakens its claim to transactional efficiency.

The Police Power

O’Malley rightly draws attention to the role of the penalty notice in facilitating non-invasive ‘simulated’ justice and policing. However, only 32% of the penalty notices processed by Revenue NSW since 2017–18 have been issued through an automated camera-based system (Revenue NSW 2022c). It is therefore important to consider how the penalty notice is used as a tool of ‘conventional’ public order policing beyond the simulated governance paradigm. Contemporary police practice has been marked by a broad shift away from reactive strategies towards what Innes and Sheptycki (2004: 2) call a ‘disruption-directed mode’ of policing. This consists of proactive intervention against low-level offences and public disorder (Innes and Sheptycki 2004: 2; Sentas and McMahon 2014: 787). The penalty notice supplies police an additional ‘legal resource’ by which to intervene against perceived risks to public order, alongside expanded move-on, stop and search and arrest powers (Dixon 1997: 12; Sentas and McMahon 2014: 787).

Individual officers enjoy effectively unreviewable discretion to issue a penalty notice instead of issuing a warning or formal caution, serving a court attendance notice or effecting an arrest (Methven 2014: 251). Judicial oversight over another central aspect of police power is minimised: the power to ‘initiate and effectively shape the content of criminal law’ (Grewcock and Sentas 2021: 202). Police are not conventionally understood to exercise a law-making function. A doctrinal commitment to the separation of powers drives the prevailing view that police act as ‘detached enforcers of the law’ (Grewcock and Sentas 2021: 202; Sentas and Grewcock 2018: 76–77). However, as Kemp et al. (1992: 92) explains, criminal offences at law are only enlivened by police who apply:

... their own interpretation of the relevant legal categories ... In the process of translation from one discourse to another (from commonsense to law) the “text” is filtered through the personal, occupational and organisational concerns of the patrol officer.

The drafting of a range of modern substantive offences, especially public order offences, enlarges the scope for officers’ interpretive discretion and supplements the residual discretion to determine whether and how to apply explicit enforcement powers (Dixon 1997: 274–275). Police are increasingly situated as the ‘primary definer’—and in the vast majority of cases where a penalty notice is issued, the ultimate definer—of flexible legal terminology, such as ‘reasonableness’, ‘offensiveness’ and ‘serious risk’ (see, e.g., Quilter and McNamara 2013; Sentas and Grewcock 2018: 83–85). Consequently, as penalty notice regimes expand, the criminal process approaches what Dubber (2005: 91–94) terms the ‘police power model’. In this paradigm, the criminal law is practically indistinguishable from police power (Sentas and Grewcock 2018: 77). It is an institution that is not concerned with the resolution of interpersonal conflict or individual rights per se but with the direct and discretionary enforcement of state authority. This entails a significant departure from principles of liberal legalism, particularly that of legislativity (which requires criminal law-making power to be exercised by the legislature alone), specificity and the separation of powers (Dubber 2005: 93, 113; Loader and Zedner 2007: 143).

The expansion of police power through penalty notice schemes affects disadvantaged and vulnerable individuals heavily. Police tend to disproportionately use penalty notices against marginalised and minority groups, such as the indigent, the homeless, the mentally ill or disabled, youth and Aboriginal peoples (Lansdell et al. 2012: 44; NSWLRC 2012: 294). These groups are highly visible to police and are more likely to display behaviours perceived as ‘antisocial’ (Brown et al. 2017: 258; Lansdell et al. 2012: 44; Methven 2019: 79–80). They are also more likely to be deemed ‘suspect communities’ and subjected to greater police surveillance and interference (Bowling and Weber 2011: 484–486; Hendry 2022: 388). The ease with which a penalty notice can be issued has the strong potential to lead police to penalise vulnerable individuals who otherwise would have been ignored or cautioned (Brown et al. 2017: 257; NSWLRC 2012: 293–295).

In issuing a penalty notice, police are not required to consider the recipient’s circumstances or vulnerabilities. Multiple fines may be issued in succession, during one escalating interaction, without any adjustment being made to account for the totality of the sanction imposed. A common example is where the imposition of a penalty notice for a minor infringement leads to further penalties for more ‘serious’ public order offences, such as the so-called ‘trifecta’ of using offensive language, resisting arrest and assaulting a police officer.[1] Officers may also use breaches of minor penalty notice offences as a gateway to exercising other police powers, including stop-and-search, bail warnings and arrest powers (Quilter and Hogg 2021: 768). The opportunities for disadvantaged individuals to challenge the decision of police to impose a penalty notice are limited. The statistical underuse of internal review applications or judicial review by vulnerable populations is informed by limited pro bono legal services, the complexity of the review process and barriers to comprehension, including illiteracy, mental illness and disability (Methven 2020: 374; NSWLRC 2012: 296; Saunders et al. 2014: 51). The power of police to authoritatively interpret and apply the law without oversight is consequently magnified in respect of the very populations most commonly subject to ‘executive sentencing’ in the form of a penalty notice (NSW Sentencing Council 2006: 102).

Administrative Fines Enforcement

When responsibility for fines enforcement passed from the judiciary to government revenue agencies in Australian jurisdictions, the change attracted little public scrutiny or academic interest. The administrative and discretionary functions of these agencies are nonetheless frequently used and highly consequential. This is because high default and low recovery rates are an enduring feature of penalty notice schemes (Donnelly et al. 2016: 1; Quilter and Hogg 2018: 16). Revenue agencies are authorised to delay enforcement and adjust the severity of penalty notices. They may also permit acutely vulnerable defaulters to ‘cut out’ unpaid fines by completing courses or undertaking unpaid work on Work and Development Orders (WDOs) (see Fines Act 1996 (NSW) pt 4 div 8). These powers import a degree of flexibility into the penalty notice system. However, in contrast to the flexible discretion exercised in judicial sentencing, revenue agencies typically require applicants to satisfy rigid criteria. Their discretion is not subject to public scrutiny and, while an independent merits review process may be available, it is conducted privately and generally in the absence of the applicant (see Fines Act 1996 (NSW) s 101B).

Revenue agencies may also inflate the punishment of fine defaulters beyond the nominal value of a penalty notice. The use of imprisonment to sanction fine defaulters has been gradually abolished in Australian jurisdictions (Quilter and Hogg 2018: 11). However, the sanctions that remain available to revenue agencies have punitive, albeit hidden, effects. Automatic driver licence suspension and cancellation is one of the most commonly deployed fines enforcement mechanisms. The removal of driving privileges has a range of consequential effects, including restricting access to paid employment and essential services and limiting opportunities to undertake caring responsibilities and participate in recreational activities (Quilter and Hogg 2018: 21–22). These effects are felt most keenly by vulnerable communities in regional, rural and remote areas where alternative means of transport are limited.

The punitive mechanisms for fines enforcement are within the remit of administrative agencies; however, vulnerable fine defaulters may also be funnelled into traditional institutions of criminal justice. ‘Secondary offending’ induced by fines enforcement action, such as driving while suspended, is prevalent and commonly attracts further, court-imposed fines and disqualification periods (see Quilter and Hogg 2018: 24). The accumulation of financial penalties and driving restrictions, together with additional fees imposed by revenue agencies for ‘enforcement costs’, exposes vulnerable fine defaulters to compounding financial hardship and escalating criminal justice system involvement. The administrative infrastructure for fines enforcement is thus capable of inflicting substantial punishment despite the apparent triviality of a nominal penalty notice (Quilter and Hogg 2018: 16, 27).

Penalty Notices and the COVID-19 Pandemic: The NSW Delta Variant Outbreak

The penalty notice regimes embedded in all Australian states and territories became a critical component of government policy in the COVID-19 pandemic. High visibility street policing and increasing ‘on-the-spot’ fines were used to drive compliance with emergency restrictions. In NSW, these coercive measures took their most restrictive and punitive form during the outbreak of the highly transmissible Delta variant from June to November 2021.

Restrictions

Public health orders (PHOs) issued by the Minister for Health were the primary mechanism used by the NSW Government to enact restrictions on movement and behaviour during the Delta outbreak (Public Health Act 2010 (NSW) s 7). A total 118 PHOs or amendments to PHOs were made between June and November 2021 during the Delta outbreak (NSW Ombudsman 2022: 66). PHOs were legally complex and typically lengthy. The ambiguity of provisions was a frequently reported issue, producing considerable confusion and requiring ad hoc clarification by authorities (Public Interest Advocacy Centre 2021).

Figure 1. Number of PHOs issued or amended in June–November 2021 (NSW Ombudsman 2022: 66)

As the outbreak worsened in July and August 2021, particularly in more disadvantaged suburbs west and southwest of Sydney, the NSW Government progressively imposed more severe restrictions upon several local government areas (LGAs) of concern. The heightened restrictions on LGAs of concern were eventually eased throughout September. On 11 October 2021, after the state had reached its 70% full vaccination rate target, stay-at-home orders were lifted across NSW. A range of restrictions on gatherings and travel, dependent on vaccination status, continued to apply but were progressively relaxed in late October and November 2021 as the vaccination rate further improved (NSW Ombudsman 2022: 100–107).

Penalties

Breaching a PHO without a ‘reasonable excuse’ was a criminal offence, which for individuals, attracted a maximum penalty of $11,000 and/or imprisonment for 6 months. A further $5,500 penalty applied for each day an offence continued (Public Health Act 2010 (NSW) s 10). NSW Police were empowered to deal with PHO breaches by way of a $1,000 penalty notice from 25 March 2020 (Public Health Amendment (Penalty Notices) Regulation 2020 (NSW)). Any person over 10 years of age, the minimum age of criminal responsibility, could be fined without regard to their capacity to pay. A wide range of breach-specific penalties were progressively introduced, and at the height of the Delta outbreak, on 16 August 2021, the value of several penalty notices was significantly increased to deter non-compliance with the escalating restrictions.

Table 1. Sample of COVID-related penalty notice offences, 16 August 2021[2]

|

Failing to wear or carry a

mask[3]

|

$40 (recipient aged 15 or younger)

$80 (recipient aged 16 or 17)

$500 (recipient aged 18 or older)

|

|

Breach of a public health order

|

$1,000

|

|

Breach of the two-person limit on outdoor gatherings

|

$3,000 (increased from $1,000)

|

|

Failing to comply with self-isolation direction

|

$5,000 (increased from $1,000)

|

|

Providing false information to contact tracer

|

$5,000

|

Policing

Boon-Kuo et al. (2021: 77–78) identified three interrelated sources of police power relevant to law enforcement in the pandemic. First, new criminal offences created by PHOs provided ground-level police officers with wide discretionary power to interpret flexible legal terminology and determine what conduct constitutes a breach. Senior police management also exercised this interpretive power by ‘clarifying’ the ambit of restrictions, particularly in the early stages of the pandemic, via press conferences, media releases and internal directives to officers (see Creagh and Mountain 2020; Fuller 2020; Thompson 2020). Second, police were granted explicit, COVID-specific powers to enforce PHO restrictions. These included the power to require a person’s name and address (Public Health Act 2010 (NSW) s 112), issue a penalty notice (s 118) or effect an arrest in response to suspected PHO breaches (s 71A). Lastly, existing police powers were available to aid the enforcement of PHOs, such as the power to stop and search persons and issue a ‘move-on’ order (Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act 2002 (NSW) ss 21, 197).

Throughout the Delta outbreak the rhetoric of government and senior police privileged ‘strong’ enforcement action to deter rule-breaking, over alternative educational or diversionary strategies. The Deputy Police Commissioner warned on 24 June 2021 that police would be moving ‘further into a compliance and enforcement regime ... rather than a simple education response’ as the initial ‘Bondi cluster’ of Delta cases expanded (Quaggin 2021). When case numbers escalated in south-west Sydney in early July, 100 additional police officers were deployed to the area to conduct high-visibility patrols and compliance checks (Kontominas and Taouk 2021).

As cases continued to rise at the end of July, 300 Australian Defence Force (ADF) officers were deployed to conduct enforcement activities in Greater Sydney (Yosufzai 2021). On 16 August, NSW Police commenced a 21-day blitz on non-compliance with lockdown restrictions called ‘Operation Stay at Home’. The operation involved 500 additional ADF officers, increased police patrols enforcing higher penalties and the use of random checkpoints in areas of concern (Cockburn 2021). The Police Commissioner challenged officers to ‘go high-level enforcement’, stating in an address:

... I am asking you to put community policing to the side for a short period of time—for 21 days I will head this operation. You need to take a strong approach to enforcement. I have said before, if you write a ticket, and you get it wrong, I understand and I won’t hold you to account for that. (Thompson 2021)

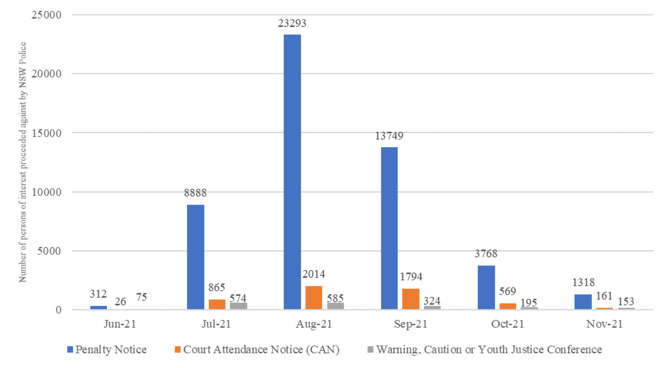

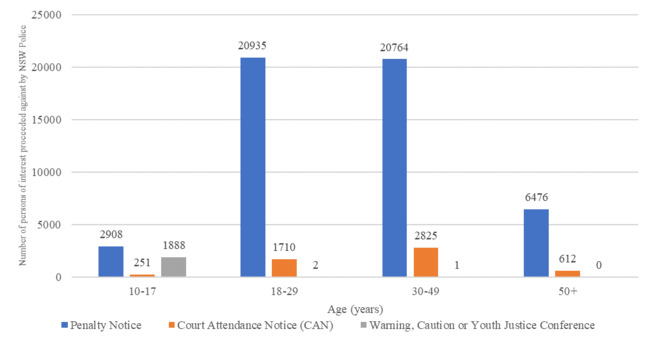

The repeated directives for officers to adopt a zero-tolerance approach to PHO breaches strongly influenced ground-level policing. Only 2,668 individuals had received COVID-related fines before the Delta outbreak. Figure 2 shows the substantial spike in enforcement actions during the Delta outbreak, with more than 23,000 penalty notices issued in August 2021 alone. Figure 3 shows that the dominant enforcement response applied to children (58%) over the same period was a penalty notice. The severity of these fines was not mitigated, except in respect of breaches of the mask-wearing requirement after 30 July 2021. Police also appear to have frequently deployed existing powers in the enforcement of public health restrictions. The NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research has reported that 48% of PHO breaches between 26 June and 31 August 2021 were accompanied by a police search (Rahman 2021; see also Boon-Kuo et al. 2021).

Figure 2. Method of proceeding for COVID-related offences from June–November 2021[4]

Figure 3. Method of proceeding for COVID-related offences by age from June–November 2021[5]

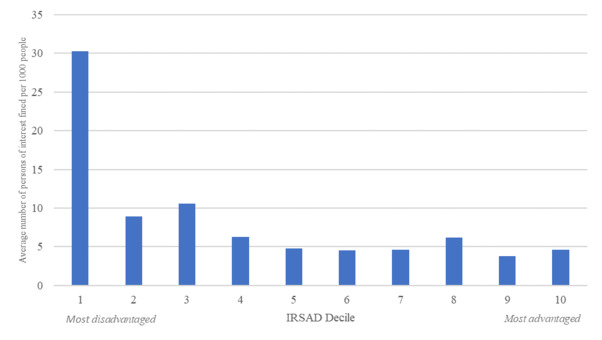

Policing data for the entire Delta outbreak reveals that vulnerable populations were disproportionately subjected to enforcement actions. Figure 4 shows that across NSW, the LGAs with the greatest socio-economic disadvantage received dramatically more penalty notices per capita compared to wealthier areas. The LGAs with the most severe fining rates were Brewarrina, Bourke, Coonamble, Walgett and Central Darling. Those LGAs are all located in regional and remote areas and have significant Aboriginal communities (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2022).

Figure 4. Rate of COVID-related fines in LGAs grouped by Index of Relative Advantage and Disadvantage (IRSAD) from June–November 2021[6]

Penalty Notice Enforcement and Reviews

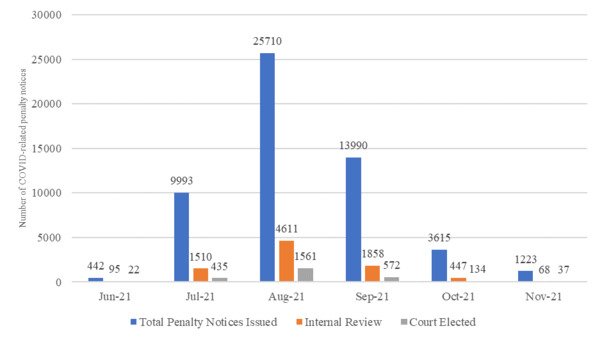

In total, 54,973 COVID-related penalty notices, worth just under $50.3 million, were issued during the Delta outbreak. As of 1 October 2022, only 26.7% of these penalty notices had been paid and 27.9% were liable to enforcement action (Revenue NSW 2022a). Enforcement action entails, first, an enforcement order and an additional $65 fee for adults ($25 for children). After 28 days, a mandatory licence suspension (attracting an additional $40 fee) applies unless the Commissioner of Fines Administration prefers to proceed with civil enforcement. Revenue NSW may also garnish wages and seize property (for which a $65 fee applies) or otherwise convert the outstanding fine into an order for community service calculated at the rate of one hour per each $15 outstanding (Fines Act 1996 (NSW) pt 4; Fines Regulation 2020 (NSW) reg 4).

As Figure 5 illustrates, a small proportion of penalty notice recipients used the available avenues of review. Only 5% of the total penalty notices issued in the Delta outbreak resulted in a court challenge. An internal review request was lodged in respect of 15.6% of the penalty notices issued. Revenue NSW wrote off 9.1% of the fines and substituted a further 0.04% with a caution on the basis of the recipients’ individual circumstances (Revenue NSW 2022a). WDOs were granted for 3.2% of the fines issued in the Delta outbreak, enabling the recipients to reduce their debt by up to $1,000 a month by way of unpaid work, courses or treatment (Fines Act 1996 (NSW) pt 4 div 8 subdiv 1).

In November 2022, the NSW Commissioner of Fines Administration conceded that two penalty notices challenged in a Supreme Court test case had provided insufficient details of the PHO offences alleged (Beame; Els v Commissioner of Police & Ors [2023] NSWSC 347). A total 33,121 penalty notices were consequently withdrawn by Revenue NSW, representing approximately half of all COVID-related fines issued in NSW (McGowan 2022).

Figure 5. COVID-related penalty notices issued and reviewed from June–November 2021[7]

The Penalty Notice in Contemporary Criminalisation Practice: Insights and Implications

Three valuable insights may be gleaned from the pattern of penalty notice-centred criminalisation in the NSW Delta outbreak. The first is the symbiotic relationship between penalty notices and expanded police power at the level of senior and frontline officers alike. The second and closely related insight pertains to the devolution of criminal justice administration to executive agents and agencies. The substantial discretionary and punitive powers exercised by these bodies are largely unencumbered by judicial oversight and the requisites of due process. Finally, the form of criminalisation enacted through the penalty notice possesses a chameleon-like quality. It enables the executive government to exercise coercive power decisively and directly while simultaneously appearing to de-penalise and de-dramatise criminalisation. Individual justice is thus subtly eroded without agitating significant public or political criticism.

Policing with the Penalty Notice

When viewed in isolation, penalty notices ostensibly represent a site of ‘contracting criminalisation’ in terms of the modalities framework advanced by McNamara et al. (2018: 96) The penalty they prescribe tends to be substantially less than the maximum sentence that can be imposed by a court. However, penalty notices expand the discretionary and punitive powers of police. As evident in the Delta outbreak, broadly drafted penalty notice offences (and defences) provide police with significant law-making and ‘clarifying’ power. This power was exercised rhetorically by senior police in press conferences but more commonly (and consequentially) by officers on the frontline of operations. Judicial supervision over police interpretation and application of amorphous PHO provisions was highly circumscribed. Indeed, judicial review was sought for only 5% of the COVID-related fines issued in NSW during the Delta outbreak (Revenue NSW 2022a). The coercive regime enacted in the Delta outbreak thus closely resembled the police power model envisaged by Dubber (2005: 91–94). The proliferation of penalty notice offences enabled police to enforce state authority directly and with broad discretionary power, largely unconstrained by legal oversight.

Senior police officers exercised a substantial agenda-setting role in this configuration. The NSW Police leadership elected to promote a zero-tolerance policing strategy and urged the proactive use of the available ‘on-the-spot’ penalties during the Delta outbreak. The asserted need for a ‘tough’ and ‘strong’ enforcement response rested upon two questionable assumptions. The first was that the emergency restrictions were clearly understood in the community and by ground-level police. However, the frequency of rule changes and ambiguous provisions in the PHOs caused considerable confusion, particularly for vulnerable and culturally diverse communities (NSW Ombudsman 2022: 62). The second assumption was that a stricter approach to enforcement and increased penalty notices would deter non-compliance with restrictions most effectively. While increases in the perceived probability of detection has been shown to produce a deterrent effect, at least in the short term, more severe punishment generally does little to improve compliance. Normative concerns, not instrumental calculations, have consistently been shown to exert the strongest influence on behaviour (Murphy et al. 2020: 479–480; see also Moffatt and Poynton 2007). Consistent with the prior criminological research in this field, Murphy et al. (2020: 490) found compliance with lockdown restrictions in Australia was most strongly motivated by an individual’s sense of duty to support authorities. The perceived risk of sanctions played little role in predicting compliance. These findings suggest that community policing, including the use of education and non-punitive forms of persuasion to build confidence in authorities and emergency restrictions, should not have been devalued at the height of the Delta outbreak (Segrave and Ratcliffe 2004: 3–5). Senior police officers appear to have exercised their broad agenda-setting power based on personal field experience and the political dictates of ‘law and order commonsense’ (Bayley 2016: 168; Hogg and Brown 1998: 18).

Officers at the ground level of police operations during the Delta outbreak were highly responsive to the directives for zero-tolerance enforcement of public health restrictions. Policing data for the outbreak reveals an unprecedented spike in enforcement action and the preferential use of penalty notices against persons of interest. It was open to officers to respond to suspected breaches using a less severe intervention, such as an informal warning or formal caution. This discretion seemingly provided officers the scope to account for the circumstances and apparent vulnerabilities of prospective penalty notice recipients. However, ground-level officers not only failed to use their discretion to mitigate the inegalitarian effect of fixed fines during the Delta outbreak but disproportionately deployed penalty notices against vulnerable and marginalised individuals. As Figure 4 illustrates, the most socio-economically disadvantaged regions of NSW experienced dramatically higher rates of fining per capita. The highest rates were recorded in rural and regional areas of Western NSW in which sizeable Aboriginal communities reside (see Dharriwaa Elders Group 2022). The enforcement data further highlights that a majority of children suspected of PHO breaches were dealt with by way of a penalty notice. This is despite the availability of specific diversionary alternatives (Young Offenders Act 1997 (NSW)). The inequitable pattern of policing in the Delta outbreak mirrors the operation of successive penalty notice schemes in Australia. The quasi-judicial power afforded to police facilitates proactive and ‘disruption-directed’ interventions which primarily target vulnerable communities (Innes and Sheptycki 2004: 2).

Devolving Criminal Justice

McBarnet’s (1981: ch 7) seminal analysis of the ‘two tiers of justice’ more than 40 years ago brought the different ideologies of criminal justice within the court hierarchy into stark relief. McBarnet posited that the legalism and due process of the higher courts ‘feed ... the public image of what the law does and how it operates’ (McBarnet 1981: 153). In contrast, the lower courts process the majority of criminal law matters with less formality. According to McBarnet (1981: 153), lower courts are ‘deliberately structured in defiance of the ideology of justice [and are] concerned less with subtle ideological messages than with direct control’. The expansion of the penalty notice regime opened up a ‘third tier’ of justice ‘below’ the courts, in which an even greater proportion of offences are finalised. This is a field of ‘ultra-summary’ adjudication and sentencing that is largely hidden from judicial and public scrutiny (McNamara 2015: 47).

To maintain the appearance of due process, penalty notice recipients are afforded the choice to challenge the validity of their fine in court. However, structural disincentives make court election untenable in the vast majority of cases. The deterrent effect of these disincentives was plainly evidenced by the Delta outbreak. A recipient of a $1,000 penalty notice who elected to pursue court proceedings risked receiving a fine 11 times the original amount, in addition to 6 months imprisonment, a criminal conviction, court costs and legal fees (Public Health Act 2010 (NSW) s 10). The resulting underuse of judicial review diminishes supposedly foundational principles of the criminal law, including presumptive innocence, individualised sentencing, totality and proportionality. The vast majority of criminal law is instead wholly enacted ‘below’ the courts and outside the strictures of due process.

In this ‘third tier’ of justice, the power to mitigate and enforce penalties is assumed by state debt recovery agencies of the executive arm of government. The high default rates consistently produced by penalty notice schemes broaden the application of this power. Indeed, 27.9% of the COVID-related penalty notices issued during the NSW Delta outbreak were outstanding after almost a year had elapsed and could have attracted enforcement action. In a sizeable proportion (14.3%) of cases, Revenue NSW exercised its authority to withdraw, vary or substitute the nominal fine (Revenue NSW 2022a). The supposedly administrative character of state revenue agencies, including Revenue NSW, is belied by the significant discretion exercised by their officials at each stage of the fines lifecycle. Prescriptive procedures and eligibility criteria in the bureaucratic model of these agencies merely routinise the exercise of this discretion.

In NSW, the Commissioner of Fines Administration and their delegates have unfettered power to afford recipients additional time to pay and can decline to impose a licence suspension if ‘satisfied’ civil enforcement action is ‘preferable’ (Fines Act 1996 (NSW) ss 65, 100). Agency officials conducting internal reviews are empowered to judge the legality of penalty notices and determine whether the vulnerability of a recipient or ‘exceptional circumstances’ relating to an offence warrant withdrawal of the fine (Fines Act 1996 (NSW) s 24E(2)). A similarly wide interpretive discretion is exercised to determine if a penalty notice ought to be commuted to a WDO on grounds including ‘acute economic hardship’ or whether it should otherwise be withdrawn because the recipient lacks ‘sufficient’ financial means (Fines Act 1996 (NSW) ss 99B(1)(b)(iv), 101). The exercise of these discretionary powers has highly consequential and punitive effects, particularly for the vulnerable and socio-economically disadvantaged persons who are grossly over-represented as penalty notice recipients. Traditional conceptions of the criminal justice system and its institutions fail to capture this reality. The seemingly administrative decision making of state revenue agencies is thus shielded from significant public or judicial scrutiny.

Penalty Notices as Chameleon Criminalisation

The exponential rise of the penalty notice regime is part of a broader pattern of technocratic and administrative ‘innovation’ re-shaping contemporary criminalisation practices. This trend has seen the adoption of a wide variety of initiatives that seek to abbreviate criminal procedure and pre-empt the ‘complex and circuitous detours’ of traditional adversarial justice within the courts (O’Malley 1984: 33). These initiatives include the introduction of formalised charge negotiation schemes and substantial utilitarian discounts to provoke early guilty pleas; the expansion of summary jurisdiction over a wide range of offences formerly triable before a jury; and infringements on the ‘pure’ jury system by legislative provision for judge-alone trials and majority verdicts (Brown et al. 2020: 359–360, 376–386).

Among these ‘innovations’, penalty notice regimes hold unique appeal for governments charged with achieving public policy objectives under political pressure and resource constraints. They concentrate in the executive government and its agencies near unfettered power to exert coercive social control directly, flexibly and on a mass scale. The Delta outbreak exemplifies how the ‘front-end’ efficiency and flexibility of the penalty notice regime enables government to signal decisive and ‘strong’ action in periods of high anxiety and political initiative. The severity of penalties may be increased reactively via delegated legislation with minimal parliamentary oversight. The intended deterrent and standard setting effects of increased penalties can be accompanied by high visibility and disruption-directed enforcement blitzes. The burden of law-making is shared with senior and ground-level officers who provide post-hoc clarification of adaptable offence provisions. The ‘back-end’ of the penalty notice system transforms the punitive appearance of fixed, police-issued fines into an undifferentiated debt to be managed by administrative officials within the executive. The significant proportion of recipients who default on their fine are thus embedded within an opaque debt recovery process. The administrative stylings of this process and its perceived ‘location’ outside the criminal justice system belies its discretionary character and potentially punitive consequences.

The chameleon-like form of criminalisation enacted by penalty notices permits their expansive use in the regulation of modern societies. Penalty notices display an ostensibly benign appearance that tender them largely invisible to academic scrutiny and critical public interest. Scholars have concentrated on the spectre of a ‘punitive turn’ in modern criminal justice under forces of penal populism; however, penalty notices provide for private, transactional and ‘de-dramatised’ punishment that easily escapes notice (Quilter and Hogg 2018: 14). Penalty notice recipients are diverted from the overtly punitive experience of being arrested and charged by police, avoid the risk of receiving a substantially more severe court-imposed penalty and bypass the ‘status degradation ceremony’ represented by the conventional sentencing process (Garfinkel 1956).

These attributes camouflage the more insidious punitive effects and inequities exhibited by the penalty notice in the context of both ‘front-end’ policing practices and ‘back-end’ procedures of administrative fines enforcement. Rather than serving to reduce the severity of punishment, the ready availability of penalty notices can lead police to punish conduct that may otherwise have been addressed by a warning or formal caution. The scale of penalty notice issuance throughout the Delta outbreak gives an indication of this net-widening effect. The case study further highlights that police frequently use ‘on-the-spot’ penalties in tandem with other intrusive powers, most notably the power to conduct a personal search, and disproportionately target disadvantaged areas and those with significant Aboriginal communities. The fixed nature of penalty notices means that the economically vulnerable individuals in these areas are, in effect, punished more harshly at first instance. This inequity is exacerbated with the accumulation of late and enforcement ‘fees’; escalating fine default sanctions, including driver licence suspensions; and penalties incurred in respect of secondary offending provoked by fines enforcement action. These cumulative hardships are inflicted in the absence of the legal protections and procedural safeguards conventionally enjoyed by individuals subject to criminal punishment.

Conclusion

It is clear that the trend towards streamlined, executive-led and administered criminal justice through the ‘innovation’ of penalty notices, among others, was in train in Western states long before the onset of the pandemic. With their origins in twentieth century parking and traffic regulation, penalty notices have ascended rapidly over the course of several decades and traversed the blurred divide between ‘regulatory’ infringements and ‘real’ crimes. This now ubiquitous feature of modern criminal justice enables the executive to exert social control directly, flexibly and on a mass scale, whether through automated systems of ‘simulated governance’ or conventional public order policing (O’Malley 2010b: 796). It thus holds singular appeal for policymakers in crisis contexts and under the broader neoliberal demands for efficiency. This appeal was on full display in the NSW Government’s COVID-19 pandemic response, especially during the Delta outbreak.

There is, however, an urgent need for greater critical scrutiny of the role of penalty notices in contemporary practices of criminalisation. The net-widening effect and high default rates produced by penalty notice schemes detract from their supposed efficiency and efficacy, a point that is powerfully illustrated by the NSW Delta outbreak case study. More fundamentally, the proliferation of these schemes is grounded in narrow concern for the instrumental purpose of the criminal law; that is, behavioural regulation and control (Lacey 2004: 144). The other ‘ends’ of criminal justice are overlooked, such that the law ‘becomes nothing more than an instrument by means of which authorities enforce obedience’ (Lasch 1977: 187). Impartial and transparent adjudication is supplanted by expansive police discretion to conclusively establish ‘on-the-spot’ guilt based on mere suspicion and without any obligation to provide reasons. Discretionary and punitive powers are devolved to the executive in an opaque ‘third tier’ of justice largely hidden from legal or public scrutiny.

Law-making and law enforcement during the global COVID-19 pandemic and the NSW Delta outbreak in particular demonstrate that the penalty notice ‘innovation’ is firmly rooted in the contemporary landscape of criminal punishment. This is due in large part to its ‘chameleon-like’ nature. Despite appearing transactional and administrative, police-issued ‘on-the-spot’ fines produce hidden inequities and punitive effects that are felt keenly by the most vulnerable and marginalised. It is critical that this is brought front of mind as we evaluate the legitimacy of the penalty notice as a technique of criminalisation and punishment.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Professor Luke McNamara for his invaluable guidance throughout the development of this article. I am grateful to my family and friends for their encouragement and support.

Correspondence: Sean Mabin, UNSW Sydney, Australia smabin01@gmail.com

[1] Any number of minor transgressions can trigger this ‘trifecta’, including breach of transport regulations and mandatory bicycle helmet laws (Brown et al. 2017: 256; Quilter and Hogg 2021: 774).

[2] Public Health Regulation 2012 (NSW) sch 4, as at 16 August 2021.

[4] Data retrieved from NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (2022).

[5] Data retrieved from NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (2022).

[6] Analysis of data retrieved from NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (2022) and Australian Bureau of Statistics (2018). The latest version of the IRSAD is based on 2016 census data. Any changes in the population and socio-economic status of LGAs between 2016 and 2021 will affect the accuracy of these findings. The LGAs of Bayside, Cootamundra-Gundagai and Dubbo Regional were excluded from the analysis, as they have not been assigned an IRSAD decile.

[7] Data retrieved from Revenue NSW (2022a).

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2018) Census of population and housing: Socio-economic indexes for areas (SEIFA), Australia, 2016. https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Lookup/2033.0.55.001Main+Features12016?OpenDocument

Bayley DH (2016) The complexities of 21st century policing. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice 10(3): 163–170. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/paw019

Bell E (2011) Criminal justice and neoliberalism. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Boon-Kuo L, Brodie A, Keene-McCann J, Sentas V and Weber L (2021) Policing biosecurity: Police enforcement of special measures in New South Wales and Victoria during the COVID-19 pandemic. Current Issues in Criminal Justice 33(1): 76–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/10345329.2020.1850144

Bowling B and Weber L (2011) Stop and search in global context: An overview. Policing and Society: An International Journal of Research and Policy 21(4): 480–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2011.618735

Brown D (2013) Criminalisation and normative theory. Current Issues in Criminal Justice 25(2): 605–626. https://doi.org/10.1080/10345329.2013.12035986

Brown D, Cunneen C and Russell S (2017) ‘It’s all about the Benjamins’: Infringement notices and young people in New South Wales. Alternative Law Journal 42(4): 253–260. https://doi.org/10.1177/1037969x17732703

Brown D, Farrier D, McNamara L, Steel A, Grewcock M, Quilter J, Schwartz M, Anthony T and Loughnan A (2020) Criminal laws: Materials and commentary on criminal law and process of New South Wales, 7th ed. Alexandria: The Federation Press.

Cockburn P (2021) NSW toughens lockdown rules and boosts fines: Here’s what you need to know. ABC News, 14 August. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-08-14/nsw-new-covid-rules-and-fines/100377514

Creagh S and Mountain W (2020) Can I visit my boyfriend? My parents? Can I go fishing or bushwalking? Coronavirus rules in NSW, Queensland and Victoria explained. The Conversation, 1 April. http://theconversation.com/can-i-visit-my-boyfriend-my-parents-can-i-go-fishing-or-bushwalking-coronavirus-rules-in-nsw-queensland-and-victoria-explained-135308

Dharriwaa Elders Group (2022) Statement: High numbers of COVID19 fines issued by NSW Police in Walgett. https://www.dharriwaaeldersgroup.org.au/index.php/news/220-high-numbers-of-covid19-fines-issued-by-nsw-police-in-walgett

Dixon D (1997) Law in policing: Legal regulation and police practices. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Donnelly N, Poynton S and Weatherburn D (2016) Willingness to pay a fine. Crime and Justice Bulletin No. 195. Sydney: NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research.

Dubber MD (2005) The possession paradigm: The special part and the police power model of the criminal process. In Duff RA and Green S (eds) Defining crimes: Essays on the special part of the criminal law: 91–118. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199269228.003.0005

Einat T (2014) History of fines. In Bruinsma G and Weisburd D (eds) Encyclopedia of criminology and criminal justice: 2149–2153. New York: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-5690-2_275

Fox R (1995) Criminal justice on the spot: Infringement penalties in Victoria. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology.

Fuller P (2020) Can L-Platers still drive and have driving lessons during the coronavirus pandemic? ABC News, 9 April. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-04-09/l-platers-learning-to-drive-under-coronavirus-restrictions/12131826

Garfinkel H (1956) Conditions of successful degradation ceremonies. American Journal of Sociology 61(5): 420–424. https://doi.org/10.1086/221800

Garland D (2002) The culture of control: Crime and social order in contemporary society. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Grewcock M and Sentas V (2021) Strip searches, police power and the infliction of harm: An analysis of the New South Wales strip search regime. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 10(3): 191–206. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcjsd.1665

Hendry J (2022) ‘The usual suspects’: Knife crime prevention orders and the ‘difficult’ regulatory subject. The British Journal of Criminology 62(2): 378–395. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azab063

Hogg R (1983) Perspectives on the criminal justice system. In Findlay M, Sutton J and Egger SJ (eds) Issues in criminal justice administration: 3–19. Sydney: George Allen and Unwin.

Hogg R and Brown D (1998) Rethinking law and order. Annandale: Pluto Press.

Husak D (2008) Overcriminalization. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Innes M and Sheptycki JWE (2004) From detection to disruption: Intelligence and the changing logic of police crime control in the United Kingdom. International Criminal Justice Review 14: 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/105756770401400101

Kemp C, Fielding N and Norris C (1992) Negotiating nothing: Police decision-making in disputes. Aldershot: Avebury.

Kontominas B and Taouk M (2021) NSW Police deny targeting multicultural communities in COVID-19 operation. ABC News, 9 July. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-07-09/nsw-police-defend-covid-19-operation-in-south-west-sydney/100280106

Lacey N (2004) Criminalization as regulation: The role of criminal law. In Parker C, Scott C, Lacey N and Braithwaite J (eds) Regulating law: 144–167. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199264070.003.0008

Lacey N (2009) Historicising criminalisation: Conceptual and empirical issues. Modern Law Review 72(6): 936–960. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2230.2009.00775.x

Lansdell G, Eriksson A, Saunders B and Brown M (2012) Infringement systems in Australia: A precarious blurring of civil and criminal sanctions. Alternative Law Journal 37(1): 41–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1037969x1203700110

Lasch C (1977) Haven in a heartless world. New York: Basic Books.

Loader I and Zedner L (2007) Police beyond law. New Criminal Law Review 10(1): 142–152. https://doi.org/10.1525/nclr.2007.10.1.142

McBarnet DJ (1981) Conviction: Law, the state and the construction of justice. London: Macmillan.

McGowan M (2022) More than 33,000 covid fines withdrawn in NSW after adverse court ruling. The Guardian, 29 November. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2022/nov/29/more-than-33000-covid-fines-withdrawn-in-nsw-after-adverse-court-ruling

McNamara L (2015) Criminalisation research in Australia: Building a foundation for normative theorising and principled law reform. In Crofts T and Loughnan A (eds) Criminalisation and criminal responsibility in Australia: 33–51. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

McNamara L, Quilter J, Hogg R, Douglas H, Loughnan A and Brown D (2018) Theorising criminalisation: The value of a modalities approach. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 7(3): 91–121. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcjsd.v7i3.511

Methven E (2014) ‘A very expensive lesson’: Counting the costs of penalty notices for anti-social behaviour. Current Issues in Criminal Justice 26(2): 249–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/10345329.2014.12036018

Methven E (2019) Cheap and efficient justice? Neoliberal discourse and criminal infringement notices. University of Western Australia Law Review 45(2): 65–98.

Methven E (2020) Commodifying justice: Discursive strategies used in the legitimation of infringement notices for minor offences. International Journal for the Semiotics of Law 33(2): 353–379. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11196-020-09710-z

Moffatt S and Poynton S (2007) The deterrent effect of higher fines on recidivism: Driving offences. Crime and Justice Bulletin No. 106. Sydney: NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research.

Murphy K, Williamson H, Sargeant E and McCarthy M (2020) Why people comply with COVID-19 social distancing restrictions: Self-interest or duty? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology 53(4): 477–496. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004865820954484

NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (2022) The impact of COVID on the NSW criminal justice system: COVID public health breaches. https://www.bocsar.nsw.gov.au/Pages/bocsar_pages/COVID.aspx

NSW Law Reform Commission (2012) Penalty notices. https://www.lawreform.justice.nsw.gov.au/Documents/Publications/Reports/Report-132.pdf

NSW Ombudsman (2005) On the spot justice? The trial of criminal infringement notices by NSW Police. https://www.ombo.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/125719/On-the-Spot-Justice-The-Trial-of-Criminal-Infringement-Notices-by-NSW-Police-April-2005.pdf

NSW Ombudsman (2009) Review of the impact of criminal infringement notices on Aboriginal communities. https://www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/tp/files/19933/FR_CINs_ATSI_review_Aug09.pdf

NSW Ombudsman (2022) The COVID-19 pandemic: Second report. https://www.ombo.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/138213/The_COVID-19_pandemic_second_report.pdf

NSW Sentencing Council (2006) The effectiveness of fines as a sentencing option: Court-imposed fines and penalty notices. https://sentencingcouncil.nsw.gov.au/documents/our-work/fines/interim_report_on_fines.pdf

O’Malley P (1984) Technocratic justice in Australia. Law in Context 2: 31–49.

O’Malley P (2009a) The currency of justice: Fines and damages in consumer societies. London: Taylor and Francis Group.

O’Malley P (2009b) Theorizing fines. Punishment and Society 11(1): 67–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/1462474508098133

O’Malley P (2010a) Fines, risks and damages: Money sanctions and justice in control societies. Current Issues in Criminal Justice 21(3): 365–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/10345329.2010.12035855

O’Malley P (2010b) Simulated justice: Risk, money and telemetric policing. British Journal of Criminology 50(5): 795–807. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azq036

Pratt J (2020) Law, insecurity and risk control: Neo-liberal governance and the populist revolt. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Public Interest Advocacy Centre (2021) Open letter: A call to address unjust COVID-19 fines. https://piac.asn.au/2021/09/16/open-letter-a-call-to-address-unjust-covid-19-fines/

Quaggin L (2021) NSW Police to ramp up response to those breaking COVID rules. 7 News, 24 June. https://7news.com.au/lifestyle/health-wellbeing/nsw-police-to-ramp-up-response-to-those-breaking-covid-rules-c-3209385

Quilter J and Hogg R (2018) The hidden punitiveness of fines. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 7(3): 9–40. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcjsd.v7i3.512

Quilter J and Hogg R (2021) [I]f it’s a public health and safety thing ... why not just give the kids helmets?: Policing mandatory helmet laws in New South Wales. University of New South Wales Law Journal 44(2): 747–785. https://doi.org/10.53637/IGBN9251

Quilter J and McNamara L (2013) Time to define ‘the cornerstone of public order legislation’: The elements of offensive conduct and language under the Summary Offences Act 1988 (NSW). University of New South Wales Law Journal 36(2): 534–562.

Quilter J and McNamara L (2018) Special issue: Hidden criminalisation—Punitiveness at the edges: Guest editors’ introduction. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 7(3): 1–3. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcjsd.v7i3.559

Rahman S (2021) Breaches of COVID-19 public health orders in NSW. Bureau Brief No. 157. Sydney: NSW Bureau of Crimes Statistics and Research.

Revenue NSW (2022a) COVID-19 offences: Data and statistics (1 October 2022). https://www.revenue.nsw.gov.au/help-centre/resources-library/statistics

Revenue NSW (2022b) Criminal infringement notice scheme (CINS) offences: Data and statistics (1 October 2022). https://www.revenue.nsw.gov.au/help-centre/resources-library/statistics

Revenue NSW (2022c) Penalty notice dashboard. https://www.revenue.nsw.gov.au/help-centre/resources-library/statistics/penalty-notice-dashboard

Saunders B, Lansdell G, Eriksson A and Brown M (2014) The impact of the Victorian infringements system on disadvantaged groups: Findings from a qualitative study. The Australian Journal of Social Issues 49(1): 45–66. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1839-4655.2014.tb00299.x

Segrave M and Ratcliffe J (2004) Community policing: A descriptive overview. Report. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology.

Sentas V and Grewcock M (2018) Criminal law as police power: Serious crime, unsafe protest and risks to public safety. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 7(3): 75–90. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcjsd.v7i3.554

Sentas V and McMahon R (2014) Changes to police powers of arrest in New South Wales. Current Issues in Criminal Justice 25(3): 785–801. https://doi.org/10.1080/10345329.2014.12035998

Simon J (2007) Governing through crime: How the War on Crime transformed American democracy and created a culture of fear. New York: Oxford University Press.

Thompson A (2020) NSW Police internal directives for COVID-19 fines revealed. The Sydney Morning Herald, 17 July. https://www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/nsw-police-internal-directives-for-covid-19-fines-revealed-20200716-p55coc.html

Thompson A (2021) Police commissioner says officers wrongly issuing tickets won’t be held to account. The Sydney Morning Herald, 19 August. https://www.smh.com.au/national/police-commissioner-says-officers-wrongly-issuing-tickets-won-t-be-held-to-account-20210819-p58k76.html

Yosufzai R (2021) Hundreds of Australian defence force troops to be deployed to greater Sydney to enforce lockdown measures. SBS News, 29 July. https://www.sbs.com.au/news/article/hundreds-of-australian-defence-force-troops-to-be-deployed-to-greater-sydney-to-enforce-lockdown-measures/56x9wjr7n

Legislation cited

Criminal Procedure Act 1986 (NSW)

Criminal Procedure Regulation 2017 (NSW)

Fines Act 1996 (NSW)

Fines Regulation 2020 (NSW)

Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act 2002 (NSW)

Public Health Act 2010 (NSW)

Public Health Amendment (Penalty Notices) Regulation 2020 (NSW)

Public Health Regulation 2012 (NSW)

Young Offenders Act 1997 (NSW)

Cases cited

Beame; Els v Commissioner of Police & Ors [2023] NSWSC 347

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/IntJlCrimJustSocDem/2023/35.html