|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy |

Building a Panopticon Through Nodal Governance: Mass Surveillance and Plural Policing in China’s COVID-19 Lockdown

Qi Chen

University of Nottingham, United Kingdom

Abstract

Keywords: Health code; plural policing; nodal governance; denizenship; surveillance capitalism; COVID-19; China.

Introduction

China’s response to the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has been fiercely debated since 2020. The health code system is arguably the most controversial aspect of the response. Originally developed by the e-commerce company Alipay for the local government of Hangzhou, at its peak, this system monitored over 900 million citizens (Liang 2020). The system does not rely on Bluetooth technology; rather, it asks each user to declare their personal health information and travel history via an application (app). Drawing on the personal data and data supplied by public service providers, the system calculates the possibility of close contact and the likelihood of contracting the virus using algorithms (Cong 2021). It is essentially a profiling tool instead of a trace-and-track tool. Based on the evaluation, each user is allocated a green, yellow or red code. Red- and yellow-code bearers are classified as risks and subject to mandatory quarantine either at home or at a centralised facility. It is no exaggeration to say that the health code system, together with the frontline agents who check the codes and enforce movement control, formed an unprecedented panopticon in China during the pandemic.

Originally, there was limited civic resistance to this panoptic system (Liu 2020), which is an intriguing response that demands academic attention. However, the Chinese public gradually turned against the system. In June 2022, residents in Henan started a protest after several regional banks collapsed, causing financial losses to depositors (Wu 2022). The local government assigned red codes to protestors who were not COVID-19 patients or close contacts, attracting nationwide attention. Officials in Henan were reprimanded, and the State Council restated that health codes should only be used for pandemic control (Song 2022). However, the public’s discontent continued.

In November 2022, China saw its largest protests since 1989. Thousands of people took to the streets, demanding the end of radical pandemic control (Guyer 2022). In a dramatic U-turn, on 7 December 2022, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) declared the end of the ‘zero-covid’ policy (National Health Commission 2022). In March 2023, representatives of the National People’s Congress (NPC) and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) openly demanded that the health code system be scrapped and relevant data be deleted (Fan 2023). Some local governments conceded (Tang 2023), but there is still a lack of certainty and transparency in this area. Further, the health code system has created a dangerous precedent for the next pandemic or crisis. Thus, it is imperative that a close examination of the system be conducted.

Drawing on social media data and secondary resources, this paper explores the dynamic social relations and power struggles underlying China’s health code system. It addresses two specific research questions:

1. What contextual factors gave rise to the health code system?

2. What implications does the health code system have for community governance in urban China?

Based on the answers to these questions, this paper also discusses the lessons that can be learnt from the Chinese experience, both practically and theoretically.

Beyond Authoritarianism and Communism: Urban Communities[1] Before the Pandemic

When it comes to questions about China, authoritarianism and communism are often offered as the obvious answers. It is easy to argue that the health code system emerged because a lack of valid opposition enabled the Chinese state to enforce draconian policies (Huang 2020), or that the Chinese public firmly believes in a benevolent guardian state and the reasonableness of its decisions (Liu and Zhao 2021). There is some truth to such arguments; however, they ignore the practical question of how to make the health code system operational. After all, a coloured code means nothing if the rules attached to it are not enforced by agents. To build a panopticon, the Chinese state needs people to enforce surveillance and control at the grassroots level.[2]

Previous research has shown that the state police[3] of China were not frontline enforcers during the pandemic (Jiang and Xie 2020). This role was undertaken by private and third-sector organisations (Chen 2020a; Hu and Sidel 2020). Such findings might sound counter-intuitive, but the Chinese state does not have an army of agents readily at its command. Ang (2012) revealed that the Chinese state bureaucracy is substantially smaller than that of other countries. The police service strength[4] of China is also weaker than that of western democracies (Chen 2018).

Moreover, while urban China used to be governed through work units (danwei), the era of communism ended with the housing reform of the 1990s (Deng 2014). Before the reform, people working in state enterprises and public institutions were entitled to centrally allocated housing. After the reform, collective and state ownership of property became rare (Deng 2014). Most of the newly built residential blocks are commodity properties that take the form of gated communities (Huang 2006). They resemble a type of ‘mass private property’ described by nodal theorists (Shearing and Stenning 1983). To some extent, urban China is now governed by neoliberalism rather than communism (He and Wu 2009).

The booming housing market has helped the private security industry (Li 2010). Zhong and Grabosky (2009) estimated that there were over five million private security guards (PSGs; bao’an) in China. The ratio of PSGs to public police in China (1.9) has surpassed that in the United Kingdom (1.5) and the United States (1.4) (Button 2019). In this sense, China relies more on private policing than neoliberal regimes.

In addition to PSGs, estate management companies (EMCs) are important nodes in community governance. In the post-1990s era, the homeowners in a gated community usually contract with an EMC. According to Article 46 of the State Council’s Guidelines on Estate Management 2003 (2003 Guidelines), EMCs have a contractual duty to maintain order in gated communities. To fulfil this duty, they can hire PSGs; PSGs must abide by the law and respect homeowners’ rights.

‘Homeowners’ rights’ is a relatively new concept to Chinese consumers, as is ‘homeownership’ itself. Breitung (2012) argues that the fresh experience of private housing ownership created a strong attachment between Chinese consumers and the properties on which they spent their life savings. Homeowners want to exercise all the rights associated with house ownership, including the right to private security. As a result, homeowner associations (HAs) have become increasingly common in China. Homeowners use HAs to fight developers and EMCs when their interests clash. Some authors see this trend as a sign of grassroots democracy and self-governance (He 2015; Tang 2015).

Nonetheless, it is difficult to establish a formal HA due to government-imposed constraints (Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development 2009). Ye and Ye (2008) estimated that 83% of the gated communities in Shanghai have their own HA, but at the national level, the percentage might be lower than 30%. Digital networking tools, such as WeChat, have enabled Chinese homeowners to bypass some of the official barriers to making a collective voice (Harwit 2016). As discussed further below, informal HAs on WeChat played crucial roles in nodal governance during the pandemic.[5]

The Chinese government recognises the pluralisation of security governance in grassroots communities. The 2003 Guidelines set out some general principles for conflict resolution and collaboration. According to Articles 8 and 20 of the 2003 Guidelines, if PSGs act unlawfully, HAs can challenge the PSGs and EMCs on behalf of all homeowners. In public security emergencies, EMCs and HAs must cooperate with the state.

However, the ‘state’ is an obscure concept in grassroots communities. Due to the small size of the Chinese bureaucracy, at the grassroots level, the state’s role is mainly executed by ‘Residents’ Committees’ (RCs; juwei hui). RCs are defined as self-governing organisations in Chinese law. RC members are supposed to be elected by residents. In the original design, RCs are civil society nodes that link grassroots communities with local governments (Mok 1988). However, in reality, RC leaders are usually CCP members (Yang et al. 2021). Due to the use of indirect elections, RC members also tend to be CCP members (Bing 2012).

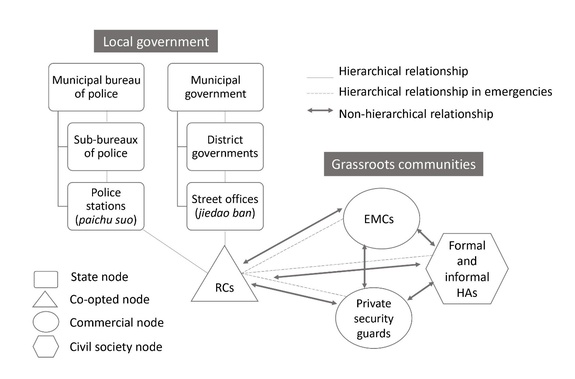

Consequently, RCs have largely been co-opted by local governments. They are subordinate to street offices (jiedao ban) and police stations (paichu suo) and assist them to enforce social policies and monitor risk groups. The relationship among RCs, EMCs, HAs and PSGs is not simply hierarchical. Under the 2003 Guidelines, EMCs and HAs are obliged to cooperate with RCs during emergencies; however, in normal times, the relationship among them is dynamic. EMCs and PSGs have contractual duties towards homeowners; HAs negotiate with EMCs and RCs on behalf of all homeowners; RCs often need the support of EMCs and HAs to fulfil their duties (He 2015; Tang 2015). Diagram 1 illustrates the network of community governance in China before the pandemic.

Diagram 1: Security governance in Chinese urban communities (before the pandemic)

As Diagram 1 shows, before the pandemic, Chinese urban communities were largely independent of local governments. At the bottom level, barely any state nodes were directly involved in governance. To understand how such a pluralised governance model gave rise to a full-scale panopticon, a proper theoretical framework is needed. The following literature review constructs this framework by synthesising academic research on nodal governance and panopticon.

Nodal Governance and the Panopticon: Revisit the Connection

‘Nodal governance’ is an elaboration of contemporary network theory that explains how various actors in a social system interact with each other to govern the system they inhabit (Shearing and Burris 2004). It is widely applied to research on plural policing. Wood and Shearing (2007) argue that since the late 20th century, security production has evolved from state monopoly to networked nodal governance, where multiple nodes collaborate and produce diverse security outcomes. These outcomes are not solely shaped by the state’s mentality. They can also be shaped by the mentalities of private security companies and other stakeholders. From this perspective, nodal governance might help democratisation, but this outcome is not guaranteed. Shearing and Wood (2003a: 404) stress that nodal governance is an ‘empirically open’ concept. Depending on the circumstances, it can enable the state to ‘rule at a distance’ through enrolling and recruiting other nodes (Wood and Shearing 2007: 100). The eventual outcome might be a ubiquitous Leviathan.

The word ‘panopticon’ is derived from a Greek term that means ‘see all’ (Gill 1995). Betham (2010) conceived the idea of a ‘prison panopticon’, which comprises a central monitoring tower and segregated cells at the periphery. It has subsequently become the most powerful metaphor in surveillance studies. According to Foucault (1977: 201), the prison panopticon is a genius disciplinary machine because it creates a ‘visible’ but ‘unverifiable’ power: the tall central power is visible to all inmates, therefore putting them in the constant fear of being monitored, caught and punished. Meanwhile, inmates can never know for sure whether they are really being watched. Consequently, they have to discipline themselves even if the central observer is absent. Eventually, discipline will be internalised by the inmates, rendering the central observer redundant.

Using the ‘leper town’ metaphor, Foucault explained how an entire society can be turned into a panopticon. In this metaphor, to curb the spread of plague and maintain a ‘pure community’ (Foucault 1977: 198), every resident of the town is quarantined in their own home. No one moves except guards, syndics and the intendant. Guards keep the doors; syndics hold the register of residents and conduct daily checks at every window. They report incidents of death and sickness to the intendant, who is the central observer of the town. Foucault (1977: 199) argues that the leper town can be replicated in any sphere of society as long as a binary division is established between the mad and sane, dangerous and harmless, and abnormal and normal. In other words, the leper is merely a symbolic figure. In real life, ‘lepers’ can be the homeless, criminals, immigrants and anyone that is perceived as ‘disorderly’.

According to Foucault, since the 18th century, western societies have become ‘disciplinary societies’ in which panoptic mechanisms dominate social spheres. This was first achieved through the ‘swarming of disciplinary institutions’ (Foucault 1977: 211), such as religious organisations, charities, schools, hospitals and prisons. The emergence of centralised state police finalised this process, as the police hold the ultimate power of state coercion to endorse various forms of discipline (Foucault 1977: 213).

The police apparatus cannot monitor private spaces directly; however, it has been equipped with the power to handle any disorders that cannot be contained privately. Thus, the police apparatus has become the ‘central tower’ in a disciplinary society. Its physical presence is not verifiable by average people, but the threat of coercion it represents is constantly felt by all citizens. Moreover, because the police apparatus (in the 18th century) was owned by the state, it essentially linked the absolute power of the sovereignty to other disciplinary institutions, such as workshops, armies and schools. Together they form an ‘intersecting gaze’ (Foucault 1977: 217), under which individuals are repetitively examined, classified and trained to internalise disciplinary norms. Eventually, individuals become docile bodies attached to ‘greater functions’ in society; for example, factory production and the war machine, both of which were vital to 18th-century nation states (Foucault 1977: 211).

The connection between nodal governance and the panopticon lies in the delicate power relations between the state and other disciplinary institutions. As mentioned above, Wood and Shearing (2007) note that nodal governance might enable the state to colonise non-state nodes and rule at a distance; However, they also emphasise that non-state nodes can resist the infiltration of the state by using context-specific opportunities, localised knowledge and other strengths (Wood and Shearing 2007: 104). Through the creative use of such resources, non-state nodes can initiate ‘democratic bargaining’ with the state. They can even gain advantages over state nodes in such bargaining.

The question that arises is whether it is necessarily desirable for the state to lose its privileged position in nodal governance. There are concerns that unregulated pluralisation may cause more harm than good. Private security providers may only care about profits. Their customers may treat policing and security services as ‘club goods’ (Crawford 2006) instead of ‘public goods’ (Loader and Walker 2001). Customers’ pursuit of extra security can leave others, usually the poor and marginalised groups, bearing the burden of disproportionate control. To uphold public interests over private interests, an ‘anchoring state’ is needed (Loader and Walker: 2006).

Shearing and Wood (2003b: 217–218) rejected the advocation for such ‘anchored pluralism’ (White 2011), as it can be used to reinstate state control. However, they admitted that the efficacy of nodal governance might be compromised by unequal access to economic, social and other forms of capital (Shearing and Wood 2003b: 207). Theoretically, they used the term ‘denizenship’ to denote such inequality. In political science, a denizen is an immigrant who has not gained full citizenship; conversely, in nodal theory, a denizen is a person who has an affiliation with a governance domain (Shearing and Wood 2003a). The affiliation can derive from employment, membership, property ownership or simply a ticket. In the context of private security, denizens (homeowners, permanent or long-term residents, business owners, authorised employees and customers) tend to have a bigger say in nodal governance than non-denizens (temporary residents, the general public and homeless people). Shearing and Wood (2003b: 217–218) proposed solutions to the inequalities arising from denizenship; for example, developing a better governance framework for inclusive participation and empowering marginalised social groups through block grants of tax resources. However, these alternative solutions can only work if there is a real political will to address inequalities.

The rise of mass surveillance[6] enabled the state to achieve equivalent outcomes without addressing real inequalities. This was achieved through modulation and dehumanisation. In the era of mass surveillance, every time a person browses a website, drives a car, makes a debit or credit card purchase or logs their location on their phone, they leave digital trails in different databanks owned by the state or private companies. Their personhood thus becomes fragmented. The fragmented pieces are monitored and modulated by different digital systems (Iveson and Maalsen 2019). It is at this point that individuals become ‘dividuals’ (Deleuze 1992), as they are now ‘divisible and reducible to data representations via the modern technologies of control’ (Williams 2005: 104). In this new situation, individuals ‘lose their aura of distinctiveness’ (Williams 2005: 108). Their identities fade into the background, and the behavioural data that can be processed by algorithms for analysis, prediction and manipulation becomes prominent.

Algorithms are radically indifferent. They treat all individuals as ‘organisms that behave’ (Zuboff 2019: 377). In a perfectly data-driven society, the predictive power of algorithms will eliminate the friction arising from individual moral and political bearings (e.g., race, ethnicity, gender, social class and denizenship), as all individuals, together with the social networks they inhabit, are ‘tuned’ to behave in a way that fits the plan of Big Brother (the state) and Big Other (big-tech companies) (Zuboff 2019: 434). Plans will eventually replace politics, rendering concepts such as social class and denizenship redundant (Zuboff 2019: 432–435). Accordingly, computation will also replace the political life of the community as the basis for governance (Zuboff 2019: 434). The foundation of nodal governance is thus destroyed. What remains is a neo-panopticon in which individuals are not only watched but also ‘programmed’ to operate without them even noticing.

The infrastructure for such a neo-panopticon already existed in China before the pandemic. As mentioned above, the health code system operates on Alipay and WeChat, both of which are ‘super apps’ (Chen, et al. 2018) that are deeply woven into daily life. One would find it extremely difficult to access any private or public services without these apps. Thus, Alipay and WeChat are able to extract a massive body of behavioural data for modulation. Moreover, the Chinese government’s deep belief in technological solutionism has motivated it to expand its collaboration with big-tech companies, especially in urban planning and the security industry (Huang and Tsai 2022; Zhang et al. 2022). The pandemic merely provided a ‘timely’ crisis that justified and accelerated these collaborations.

Drawing on the literature review, the following hypotheses were developed in relation to the research questions:

Hypothesis 1: The pluralised governance model in Chinese urban communities led to conflicts between denizens and non-denizens during the pandemic.

Hypothesis 2: Mass surveillance and stronger state control were ‘justified’ as solutions to these conflicts.

Hypothesis 3: These ‘solutions’ damaged the pluralised governance framework in Chinese urban communities.

The following section explains the methods used to test these hypotheses.

Data Collection and Methodology

This study used data extracted from the Chinese social media platform, Weibo, to reconstruct security governance in urban communities during the pandemic. In China, many aspects of urban life came to a halt due to the lockdown, but online activism peaked. According to Sina Technology (2020), user traffic on Weibo increased by 40% between January and March 2020. Various studies have used social media data to explore the pandemic response in China (Li et al. 2020; Liang 2020; Liu and Zhao 2021). There is no denying that government censorship online can pose challenges to social media–based studies (Li 2020; Tai and Fu 2020). However, research shows that Chinese netizens are more likely to ‘rebel’ against censorship and voice their opinions when they experience censorship themselves or witness censorship occurring to their friends or a reference person (Zhu and Fu 2021). This might explain why censorship backfired during the pandemic; instead of oppressing criticism, it stimulated more active public engagement online (Chen X 2020).

This study used the rich body of data generated by this online engagement. To answer the question, ‘What contextual factors gave rise to the health code system?’, it focused on the following three key weeks at the early stage of the pandemic: Week One (24 to 30 January 2020), Week Two (10 to 16 February 2020), and Week Three (10 to 16 March 2020). Week One followed the announcement of the Wuhan lockdown. Week Two marked the beginning[7] of ‘return to work’ (fugong fuchan). In Week Three, the national lockdown was ending, and the use of health codes was normalised to prevent a resurgence of COVID-19. It was expected that the most informative public discourse would have occurred in these weeks.

Web scraping was conducted in August 2021 using Python. The author started with a combination of two general terms, ‘community’ (xiaoqu) and ‘governance’ (guanli). In total, 3,498 posts were collected based on the following two criteria: 1) the posts contained the terms ‘community’ and ‘governance’; 2) the posts were published during the three key weeks. This data set was named Corpus A. Using the same approach, the author also obtained Corpus B (i.e., 3,023 posts containing the terms ‘community’ and ‘EMCs’ (wuye)) and Corpus C (i.e., 3,012 posts containing the terms ‘community’ and ‘PSGs’).

Other combinations of terms were also piloted, as the author initially planned to cover all four nodes in grassroots governance; for example, ‘community’ and ‘RCs’, and ‘community’ and ‘HAs’ (see Figure 1). However, these pilot searches returned limited posts, and these data were discarded. In the findings section, the author discusses why HAs and RCs were rarely mentioned in online discussions about community governance.

Python was used to prepare the data sets. After stop-word removal and tokenisation,[8] a term frequency (TF) analysis was applied to the 9,533 posts in Corpora A, B and C. Key terms were identified in each data set based on relative TF.[9] These key terms were divided into two categories: ‘character’ terms and ‘plot’ terms (Prior 2014). Character terms (e.g., ‘tenants’, ‘migrants’ and ‘outsiders’) revealed who was featured in the public discourse. Plot terms highlighted what was in the characters’ minds, how they described the situation surrounding them and how they felt in that situation. Together, these key terms gave the author a general impression of what happened to community governance in urban China and how things evolved chronologically during the three key weeks. However, as any such general impression might be inaccurate due to the use of synonyms and grammatical variations of words (Krippendorff 2022), a qualitative content analysis was conducted to complement the TF analysis.

The author immersed herself in the text and made further notes. The qualitative analysis served three purposes in this study. First, it verified the general impression identified through the TF analysis. Second, it added details, context and personal narratives to the general impression. Third, it served to reconstruct the public discourse based on concepts identified in the literature review (Hsieh and Shannon 2005). A sample of posts was selected based on their representativeness.[10] These posts are included in the findings section of this paper to enrich the empirical account and re-represent the discourse (Krisppendorff 2022). Secondary resources are also discussed as relevant.

Findings

The author adopted a zoom-in approach in the representation of findings. In Part One, the author explains how community governance evolved during the three key weeks, emphasising the changing relationship between state and non-state nodes. Part One provides the general context for nodal governance and state control at the early stage of the pandemic. In Part Two, the author focuses on one acute problem arising from pluralised community governance; that is, conflicts between denizens (homeowners) and non-denizens (migrants and tenants). Part Two also traces how the state presented the health code system as a solution to such conflicts. The theoretical framework identified in the literature review is used to organise the findings. In Part One, the author focuses on the deficits of nodal governance and the temptation of an ‘anchoring’ state. In Part Two, the findings are discussed in relation to denizenship, equality and the ‘false promise’ of mass surveillance.

Radical Pluralism and the ‘Anchoring’ State

In the previous section of this paper, the author explained why the governance framework in Chinese urban communities is highly pluralised and how non-state nodes, such as EMCs, are a crucial part of it. The results of the Relative Term Frequency (RTF) analysis further support these arguments. Graph 1 shows the characters that were most frequently mentioned in the public discourse about community governance.

Graph 1. Key characters in community governance during the pandemic (identified in Corpus A)

As Graph 1 shows, the top three key characters in community governance were ‘EMCs’, ‘commanding units’ and ‘homeowners’. The commanding units were the local leadership panels, which consisted of ‘chief secretaries’ of local CCP committees and ‘leaders’ of relevant government agencies. The commanding units formulated local responses to the pandemic. These policies were passed from the ‘municipalities’ (shi) to the ‘streets’ (jiedao). At the grassroots level, policies were enforced by the ‘EMCs’ with the support, or sometimes opposition, of ‘homeowners’. Conversely, ‘the Party’, ‘the government’ and ‘the state’ were mentioned far less frequently.

The content analysis provided qualitative insights into why this was the case. At the beginning of the pandemic, the Chinese state adopted a ‘firebreak’ rationale: the pandemic centre (Wuhan and Hubei) must be immediately sealed, and all people who recently visited the pandemic centre must be found and tested. This was a challenging task because the pandemic broke out right before the Chinese New Year. Numerous migrant workers had returned from Hubei to their hometowns for the celebration. Five million Wuhan residents also fled the city before the lockdown (Ma and Zhuang 2020). Chinese local governments simply did not know enough about grassroots communities to identify the migrants and refugees. As one cadre[11] admitted:

We didn’t know how many migrants were there in each community. We consulted the local police station, but their records were outdated. Eventually, it was the EMCs that provided a list of homeowners, regular residents, and tenants. This is not perfect, but it at least gives us something to work on.

Even in Beijing, where the most rigid social control was expected, the local government had to rely on EMCs to get intelligence on grassroots communities. In an announcement posted by the Beijing Municipal Government on 26 January 2020, it was stressed that ‘EMCs are most knowledgeable about grassroots communities. They must use this strength and assist the government in trace-and-track’.

Moreover, by the beginning of Week Two, about 500 million Chinese citizens were put under quarantine (Reuters 2020). The quarantined households needed to be monitored and assisted. These responsibilities mostly fell on the EMCs again, as RCs did not have sufficient resources (Yang et al. 2021). A property market analyst made the following comment in Week Two, ‘... thanks to the pandemic, more people come to realise the importance of estate management services. In the future, communities with good EMCs will attract more property buyers. [748 likes]’. The following post by a homeowner also highlights the crucial role of EMCs: ‘... during the pandemic, I learned one truth: problems that cannot be solved by the city mayor can be easily solved by the EMC’.

Given these findings, the author used the terms ‘community’ and ‘EMCs’ in the second round of web scraping. Corpus B was produced at this stage. Based on the RTF, Graph 2 shows the characters that were most frequently associated with EMCs in online discussions.

Graph 2. Key contacts of EMCs during the pandemic (identified in Corpus B)

As Graph 2 shows, ‘homeowners’ appeared to be the most frequently mentioned characters. Conversely, mentions of ‘RCs’ were rare. Moreover, if RCs were mentioned, the comments were usually negative; for example, ‘... two weeks into the lockdown, the RC was nowhere to be seen ... Are the committee members all on holiday? ... [932 likes]’. Another comment stated, ‘... What do you expect? The RC members spend their entire life idling about and passing on government propaganda. They cannot save the day during the pandemic ...’.

These findings are not surprising. Previous research has highlighted the paradox facing RCs; on the one hand, RCs are not formal government agencies and thus lack authority and resources; on the other hand, RCs are not truly independent of the government and are thus not trusted by residents (Tang 2015). Compared to RCs, EMCs tend to have more resources and better connections with the grassroots.

PSGs were the second most frequently mentioned group in Corpus B. According to Chinese netizens, they were the main enforcers of the lockdown. One netizen stated, ‘... during the pandemic, PSGs in China achieved what could only be achieved by the police and military forces in other countries ... [115 likes].’ Another stated, ‘... obviously, the last mile of pandemic control is fulfilled by the PSGs ...’.

Given these findings, the author used the terms ‘community’ and ‘PSGs’ in the last round of web scraping. Corpus C was produced at this stage. Graph 3 shows the key contacts of PSGs.

Graph 3. Key contacts of PSGs during the pandemic (identified in Corpus C)

‘EMCs’ and ‘homeowners’ remained at the centre of online discussions. They were most frequently associated with ‘PSGs’ during the observed weeks.

The fact that ‘EMCs’, ‘homeowners’ and ‘PSGs’ were interconnected in public discourse is an intriguing finding. It shows how Chinese netizens perceived the matter of security governance at the early stage of the pandemic. Instead of viewing it as a civic matter between the authoritarian state and its citizens, security governance was construed as a consumerist matter between paying customers (homeowners) and service providers (EMCs and PSGs).

During Week One, Chinese homeowners were generally happy with the service they received. The trending sentimental words in both Corpora B and C were ‘grateful’ (0.043% and 0.104%, respectively) and ‘reassured’ (0.043% and 0.028%, respectively). Homeowners were reassured by the extra security they purchased. They were grateful for the additional responsibilities taken by EMCs and PSGs. As one homeowner stated:

I am so glad that I moved to a high-end community last year. The decision cost all my savings, but it is the best decision I ever made ... Everything is taken care of by the EMC. I can just sit at home and wait out the pandemic. [748 likes]

Another stated:

PSGs were really courteous when taking body temperature checks. They kept apologising for bothering us. I think it’s them who are being bothered by extra burdens and responsibilities because of the pandemic ...

However, public sentiments changed in Week Two, as abuses of power began. It became apparent that the PSGs had been radicalised by the sudden acquisition of unchecked power. One statement read:

... the PSGs in my community used to be nice, but everything changed after the lockdown. They were like, ‘you homeowners always look down upon us; now it’s time for revenge’ ... I tried to be polite, but the guard dropped the f-bomb and threatened to use violence ... [71 likes]

On February 11, a private guard in Xi’an killed a pet dog in the name of pandemic control (NetEase 2020). Public discontent exploded on Weibo. One post read: ‘... Senior citizens were slapped for not wearing masks. Dogs got beaten to death ... This is a living hell ... [165 likes]’.

The discontent was also shown in the trending plot terms of Week Two. In Corpus A, the words ‘martial’ (0.056%) and ‘lawless’ (0.051%) were frequently used. PSGs’ brutal actions drove Chinese netizens to demand state intervention. One netizen stated:

What on earth are the legal grounds for lockdown? ... Who authorised EMCs and PSGs to stop people and carry out checks? Aren’t these powers solely possessed by the state police? Are we removing all legal safeguards now?

The Chinese state presented itself as the ‘anchor’ in the chaos. On 17 February 2020, the People’s Daily stressed that ‘the rule of law is the bottom line’ in pandemic control (Cai 2020). It also clarified that volunteers, PSGs and EMC staff ‘are not legitimate enforcers of law’ (Cai 2020). Only the state police are authorised to take coercive actions. Additionally, stories of ‘active police involvement’[12] increased in the corpora, which explains why ‘the police’ got more mentions in Weeks Two and Three than Week One (see Graph 3).

Chinese netizens’ attitudes towards EMCs underwent similar changes. In Week One, EMCs were seen as more reliable than local governments. However, their profit-driven mentalities soon led to friction. According to the content analysis, it was quite common for EMCs to raise service fees, sell overpriced groceries and trespass on private properties in the name of pandemic control. In Week Three, a scandal broke out in Xiaogan (Phoenix News 2020). Homeowners in a gated community started a protest against the EMC and corrupted HA leaders. The EMC and HA conspired to sell overpriced groceries to homeowners. Aggrieved homeowners sourced alternative grocery suppliers through a volunteer, but the EMC reported the volunteer to the local police for ‘violating lockdown rules’ (Phoenix News 2020). The scandal ignited discussion on Weibo. As Graph 2 shows, ‘HAs’ and ‘volunteers’ received unprecedented mentions during this week. This story made Chinese netizens question the viability of pluralised governance in grassroots communities. One netizen stated:

Grassroots governance died in China when EMCs were installed in communities. They care about nothing but money. The conflict between homeowners and EMCs is inevitable ...

Again, some netizens turned to the ‘anchoring’ state for solutions. One netizen stated:

... EMCs across the country are profiteers in this pandemic ... Why can’t the local government take care of grassroots communities? I don’t mind paying a reasonable fee to the government. I have more confidence in state-provided services ...

This is not an isolated opinion. In May 2020, a representative of the NPC formally suggested that estate management services should be nationalised (Chinese Business Network 2020). Senior policymakers did not accept this suggestion, but an alternative strategy was adopted. In November 2020, the Ministry of Civil Affairs (2020) declared ‘building red EMCs’ (hongse wuye) as a priority. The plan was to let CCP members and RC members sit in HAs’ meetings and act as the supervisors of EMCs. The Ministry of Civil Affairs asserted that this strategy would improve the quality of EMC services. In December 2020, the State Council (2020) released a formal announcement, vowing to ‘strengthen the state supervision of EMCs’, ‘encourage Party members and RC members to participate in HA elections’ and ‘push the development of smart communities’. These new policies allow the Chinese state to co-opt non-government nodes in grassroots communities.

It is worth discussing why Chinese netizens turned to the ‘anchoring’ state for solutions instead of seeking alternatives; for example, a better self-governing framework, as Shearing and Wood (2003b) suggested. After all, there is some evidence of civic activism in the data set. One netizen stated, ‘... today I gave my own opinion on community governance in the homeowner’s WeChat group. Never had such experiences before ...’. Another stated, ‘... The governance of the state should be like the governance of a community. The government is just the EMC. We are the homeowners ...’.

One reason could be that Chinese homeowners were not yet an organised social force. As mentioned above, HAs are difficult to establish in China. During the pandemic, homeowners mainly relied on WeChat groups to coordinate their actions, which is why the term ‘WeChat’ was consistently mentioned in public discourse, while mentions of HAs only soared in Week Three due to the scandal mentioned above (see Graph 2).

The state-favouring sentiments among Chinese netizens paved the way for the health code system. However, such sentiments were not the sole cause. The escalating conflict between denizens (homeowners) and non-denizens (migrants and tenants) was a more important factor.

Denizenship, Equality and the Health Code System

In the literature review, the author discussed Foucault’s leper town metaphor. Foucault (1977) argued that to build a full-scale panopticon, a binary division is needed. There has to be an established threat of ‘dangerous others’ to justify disciplinary control. From the beginning of the pandemic, homeowners in gated communities drew a strong line between ‘us’ and ‘dangerous others’. The xenophobic term ‘outsiders’ was also frequently associated with PSGs, especially in Week One (see Graph 3). Homeowners demanded that PSGs keep all outsiders away, especially those from Wuhan and Hubei. On 25 January 2020, the following post ignited an outcry on Weibo: ‘... WTF? Yesterday the PSGs let in four cars fleeing Wuhan. We homeowners were not consulted or notified at all! We didn’t pay for a service like this ... [33211 likes]’.

Such regional discrimination is well documented by existing research (Xu et al. 2021). The following post captured the intensity of xenophobic sentiments at this stage:

... heated discussion in the homeowners’ WeChat group today. A family recently returned from Wuhan. Someone shared a clear picture of their house number in the chat. Everybody seems to be outraged. Neighbours criticised the EMC for being irresponsible by letting them in. Some said they had already called the police. I wanted to defend the family. I wanted to say they have privacy and rights too. But I was too afraid to stand up against the majority ...

Migrants and tenants were also viewed as risks, and even medical professionals were not exempted. In Zhengzhou, the homeowners in one community decided in an online vote that frontline medical professionals must not return to the community. The EMC faithfully enforced its customers’ decision. When this story hit the headlines (Global Times 2020), the local government had to intervene, reprimanding the EMC and overriding the homeowners’ decision. On 30 January 2020, the CCP-owned People’s Daily (2020) made a rather desperate attempt to rebalance ‘club goods’ and ‘public goods’. It urged people to ‘block the transmission of the virus, but not to block the love for your fellow citizens’ (People’s Daily 2020). However, the plea was not well received by denizens in urban communities. Their pursuit of ‘pure communities’ further clashed with migrants’ demands for freedom of movement in Week Two.

As mentioned above, most Chinese workers returned to work in Week Two. Netizens, especially migrant workers who were renting, increasingly found themselves in a dilemma. As one stated:

... I just learned from the EMC that no tenants will be let in before midnight on February 9. My company wants me back at 9 am on February 10. What am I supposed to do? Also, I heard this rule does not apply to (migrant)[13] homeowners. As a tenant, I pay my rent. I am entitled to access the property just like the homeowners. Why treat tenants differently? [389 likes]

Another stated:

... I called the EMC. They said, ‘We can’t let in any tenants’. I then dialled 12345.[14] The operator said, ‘We can’t do anything about it’. Eventually, I called the Bureau of Housing and Urban Development; they said, ‘This is not our business’. Everyone is kicking the ball around. No one cares about us. Does coronavirus only spread among tenants? [7418 likes]

Even migrant homeowners were sometimes rejected by EMCs. As one migrant homeowner stated, ‘... [w]as planning to return to work, but the EMC told me “no entry for migrants”. I’m a proper homeowner. How on earth did this happen?’

From the EMCs’ perspective, the differential treatment was justified. Homeowners pay estate management fees; they (and not the tenants) are the EMCs’ customers. The difference between local homeowners and migrant homeowners is more subtle. Due to policy restrictions and financial disadvantages, migrant workers in China face numerous barriers to homeownership (Wu 2002). As a result, locals are the main buyers on the property market and are thus the more valuable customers to EMCs. The strong xenophobic sentiments possessed by local homeowners persisted in Week Two, with one stating, ‘... I strongly oppose letting the migrants in. How much have we sacrificed to control the virus? The return of migrants will bring us back to square one ...’. Yet another stated, ‘... I heard some migrants are unhappy ... It doesn’t matter if you own property here or not. You migrants are still second-class citizens!’.

As a result of the opposition, EMCs continued to implement restrictive policies; however, the Nation Health Commission stressed that ‘communities should not reject migrant workers’ (Ji 2020). For these workers, the priority at this stage was to regain mobility. In Week Two, the phrase ‘travel pass’ was a trending term in Corpora A (0.122%), B (0.085%) and C (0.071%).

It was at this time that the local government of Hangzhou introduced the health code system. It sold this system on the promise of equality. In the official announcement released on 13 February 2020, the Municipal Government of Hangzhou (2020) promised that as long as citizens have green codes, ‘no authorities shall reject them on any grounds’. The following special note was made in relation to tenants: ‘tenants who returned to Hangzhou with a green code shall not be subject to any further restrictions’. Judging by the public’s response, the Municipal Government of Hangzhou had correctly read the national sentiment. By 17 February 2020, over 10 million people had applied for a health code, and the central government declared that the system would be rolled out nationally (Zhang 2020). The CCP’s official media platform, Xinhua News, promoted the health code system on the grounds of ‘reducing COVID-related discrimination’ (Wu 2020). The CPPCC, the official alliance of China’s alternative political parties, also praised the health code system for reducing discrimination (Mao 2020); however, it would later become a major critic of the system.

By Week Three, ‘green code’ (0.120%) had become a trending term in Corpus A. However, Chinese netizens were disappointed because the health code system did not deliver on the promise of equality. In many grassroots communities, discrimination persisted. As one netizen stated:

... my cousin already got the green code, but the community rejected him because he was unable to provide an official letter from the RC certifying that he had completed 14 days’ quarantine since returning to Beijing ... what’s the point of the green code if you still need the letter? ... Now his boss threatens to fire him if he cannot sort things out in two weeks ... [724 likes]

Another stated:

Here is the truth about health codes. The higher-ups say that everybody with a green code can travel freely. The grassroots enforcers are like, yes that’s true but you may also need this certificate and that letter ... Eventually, your fate is still decided by the guards who keep the gates.

It seems that Chinese netizens saw themselves as having two choices: either to bow to the arbitrary and brutal power of grassroots control agents or to accept ‘indiscriminate’ mass surveillance. Ironically, the latter was seen as the lesser of two evils by migrants whose livelihood depended on their mobility.

Local police forces in China tapped into this mentality. According to a message posted by the Kunming Municipal Government on Weibo, the city of Kunming had built 134 ‘smart communities’ by March 2020. In a smart community, any information collected by PSGs or community-level terminals was fed directly to the local police. No additional certificates or letters were needed, as every citizen’s information was stored in one database. The municipal government hoped that this initiative would eliminate the discrepancy between central policy and grassroots enforcement, thus ‘improving the level of public satisfaction’. According to Jiang and Xie (2020), similar initiatives were employed by police forces across China. The expansion turned private security facilities in gated communities into outposts of state control. The PSGs were thus co-opted by the state police. Ironically, the entire process was presented as a benevolent state endeavour to address the discrimination caused by consumerism.

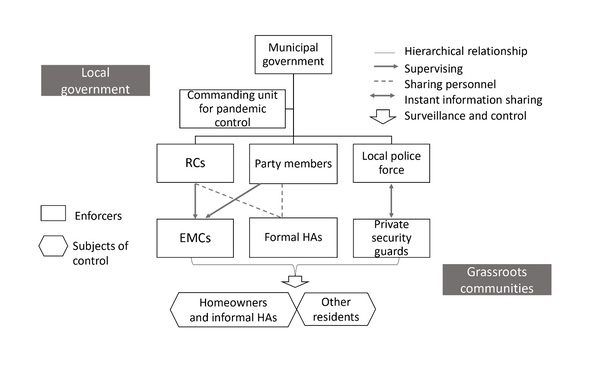

As a result of these new developments, the security governance in Chinese urban communities evolved. The pluralised elements began to disappear, while state control expanded. Diagram 2 below illustrates the mechanism of this new governance framework.

Diagram 2. Security governance in Chinese urban communities (after the pandemic)

Up to this point, an unprecedented neo-panopticon emerged. It did not enable the Chinese state to rule at a distance; rather, it removed the distance between state authority and grassroots governing units. Through mass surveillance and the assimilation of EMCs and PSGs, the Chinese state could now easily monitor the most minute movements on the ground. The outcome was very close to the utopia described by Zuboff (2019: 434) in which ‘computation replaces the political life of the community as the basis for governance’, leaving no room for negotiation and deliberation.

It took the Chinese public two years to realise the terrifying capacity of this neo-panopticon. The hard truth is that ‘indiscriminate’ surveillance did not preclude the arbitrary use of power by grassroots agents. On the contrary, it aggravated such arbitrariness, as a green code had transcended all laws, moral codes and customs in community governance. Fire exits could be blocked (Che and Chien 2022), access to medical help could be denied (Human Rights Watch 2022) and families with children could be separated (Human Rights Watch 2022), all because the algorithm indicated someone was a risk. Moreover, the scandal in Henan suggested that the neo-panopticon could easily be applied to any social realm. It was no surprise that the situation led to the biggest wave of protests in China since 1989.

Discussion and Conclusion: To Avoid a Definite Future?

The emergence of a panopticon-like society is a major concern in social science research. The advent of social media and mass surveillance has only fuelled this fear. China, as an authoritarian state that deeply believes in technological solutionism, is often seen as a ‘front runner’ in the surveillance contest. Zuboff (2019) coined the term ‘Chinese syndrome’ to denote the CCP’s devotion to ‘all-seeing’ surveillance projects. However, this study highlights that the state’s agenda is only part of the story. As the findings highlight, there are other factors contributing to the status quo in China: the inadequate nodal governance framework that provides ‘justifications’ for stronger state control, and the entrenched inequality that drives people to accept ‘indiscriminate’ surveillance. In this section of the paper, the author discusses what can be done to address these factors.

Since the ‘Open-Up and Reform’ policy in the 1970s, China has experienced rapid industrialisation, privatisation and urbanisation. Since the early 2000s, the country has experienced another round of rapid digitalisation. By the mid-2010s, China had become the world’s largest e-commerce market with the largest e-payment transaction volume (Yu 2017). Due to this unique experience, people in China embraced a ‘consumerist society’ instead of a ‘civil society’ in the post-communist era. Some of them became homeowners and gained ‘property-based denizenship’ in community governance.

The denizenship allowed Chinese homeowners to participate in deliberate governance, which helped them develop civic awareness. However, there is still a significant gap between a ‘denizen’ and a ‘citizen’. Citizenship comes with the assumption of equality. All citizens are deemed the same. Conversely, denizenship is essentially a privileged position. It grants an extra layer of social capital to the position holder and is thus inherently unequal. There is no internal motivation for denizens to embrace the virtues of ‘citizenship’, such as tolerance, self-criticism, and moderation (Heater 1999: 32). Instead, denizens naturally seek to exploit, consolidate and amplify their privileges, as privileges are the essence of ‘denizenship’. This tendency was demonstrated by the homeowners’ radical pursuit of ‘club goods’ and their complete ignorance of migrants’ and tenants’ rights.

Moreover, the commercial nodes (the EMCs in the current case) encourage consumer-denizens’ pursuit of club goods, as the more ‘valuable’ denizenship becomes, the more consumers will be attracted to it. Market analysis estimates (Yu 2020) that Chinese estate management stocks gained a 34.4% increase in earnings during the pandemic. This is not surprising. As mentioned above, the primary lessons learnt from the pandemic by many Chinese netizens were the necessity of homeownership and the desirability of good EMC services. From this perspective, the corporatist interest of commercial nodes and the privilege of consumer-denizens are interlocked. Neither can be expected to steer nodal governance towards civilised and inclusive ends. Further, the rise of super apps and big data technology makes it easier for corporate nodes to shape the needs and wants of consumer-denizens. If denizens are constantly absorbed by new wants invented by corporations and implanted in their mind through data-driven modulation, it will become harder for them to develop the empathetic vision of a citizen.

One possible solution is to create other types of ‘denizenship’ so that democratic bargaining can be facilitated between different denizen groups. Denizenship does not have to be property-based, although the culture of a consumerist society tends to make people believe this is so. If migrants and tenants in China were allowed to form their own associations, they could have found other pathways to equality instead of accepting ‘indiscriminate’ surveillance. However, partly because of policy restrictions, such diversification of denizenship did not happen. As mentioned above, the Chinese state is cautious about collective actions, which makes the establishment of HAs difficult. Compared to (local) homeowners, migrants and tenants have less economic and social capital. Thus, it can only be more difficult for them to form associations.

The lack of diversity in denizenship explains a disturbing difference between China and other Eastern Asian countries. The study conducted by Cai et al. (2021) revealed that the third sector played crucial roles in Japan, South Korea and China during the pandemic. However, compared to the other two countries, the lack of policy advocacy for marginalised groups was a striking feature of Chinese society. This is not a surprising observation given that marginalised groups are largely excluded from nodal governance in China and thus had no choice but to turn to the ‘anchoring’ state for remedies.

However, the ‘anchoring’ state in China does not have the political will to address real inequalities. In the current case, it sold the health code system on the promise of ‘indiscriminate’ surveillance and ‘equal’ treatment, but what the Chinese public received was indifferent and arbitrary treatment. This was not the first time mass surveillance was presented as a solution to a complicated social problem in China. When the infamous social credit system was introduced, the Chinese state also claimed that it would fix the collapsing bonds of trust in Chinese society (Zuboff 2019: 389). However, research suggests that the system might achieve the opposite result (Ding and Zhong 2020). Regardless of the outcome, the narrative of technological solutionism will continue to succeed, if the nodal governance framework in China keeps operating in an exclusionary way and leaving the roles of ‘anchor’ and ‘saviour’ to the state.

So, what can be done to avoid this seemingly definite future? The author argues that if marginalised social groups lack the social and economic capital to gain ‘denizenship’, then political capital needs to be conferred on them. This has been done successfully before through active journalism and academic research. Up until the early 2000s, rural migrant workers living in Chinese cities were a largely marginalised group (Wong et al. 2007). However, academic research and active journalism helped this social group gain political capital. Relying on such political capital, labour non-governmental organisations (NGOs) began to flourish in China; they became influential nodes in corporate governance (Chan 2013).

Moreover, academic research and active journalism can help construct a critical voice against technological solutionism. This critical voice is particularly important, as the collaboration between Big Brother and Big Other becomes a new dimension to nodal governance and security production. Their alliance significantly changed the power balance in the nodal network. Other nodes are becoming increasingly powerless in front of these ‘Big Planners’. Wood and Shearing (2007) argue that nodal problems should have nodal solutions, and creative nodes will always negotiate their way out of conflicts and dilemmas; however, the Big Planners are taking shortcuts. As the current study demonstrates, dynamic political life in the community can be easily terminated and substituted with data-driven modulation when it fits the Big Planners’ agenda. This possibility casts serious doubt on the future of nodal governance, as China is not the only regime that is pursuing a ‘data-driven society’ (Pentland 2013; Zuboff 2019). Powerful empirical studies and upgraded conceptual tools are needed to forge a critical voice against the Big Planners’ agenda. This study sought to make some contributions in both aspects.

Limitations of the Research

It should be stressed that the Chinese government tightened censorship on social media after the unprecedented protests in November 2022 (Hall and Pollard 2022). Researchers who wish to replicate the method of this study need to be aware of the new challenges. Moreover, this study only focused on urban communities because social media users in China tend to be urban residents (Chen 2020b). Due to cultural and demographic differences, the situation in rural areas can be more complicated.

Correspondence: Dr Qi Chen, Assistant Professor in Criminology, University of Nottingham, United Kingdom. qi.chen@nottingham.ac.uk

References

Ang YY (2012) Counting cadres: A comparative view of the size of China’s public employment. The China Quarterly 211: 676–696. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741012000884

Betham J (2010) The panopticon writings. London: Verso Books.

Bing NC (2012) The residents’ committee in China’s political system: Democracy, stability, mobilization. Issues and Studies 48(2): 71–126.

Breitung W (2012) Enclave urbanism in China: Attitudes towards gated communities in Guangzhou. Urban Geography 33(2): 278–294. https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.33.2.278

Button M (2019) Private policing. 2nd edition. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351240772

Cai F (2020) The Public has had enough: Respecting the rule of law in lockdown enforcement. People’s Daily Online, 17 February. http://opinion.people.com.cn/n1/2020/0217/c223228-31591169.html

Cai Q, Okada A, Bok GY and Kim SJ (2021) Civil society responses to the COVID-19 pandemic: A comparative study of China, Japan, and South Korea. The China Review 21(1): 107–138. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27005557

Chan CK (2013) Community-based organizations for migrant workers’ rights: The emergence of labour NGOs in China. Community Development Journal 48(1): 6–22. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bss001

Che C and Chien AC (2022) Protest in Xinjiang against lockdown after fire kills 10. The New York Times, 25 November. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/11/25/world/asia/china-fire.html

Chen Q (2018) Governance, social control, and legal reform in China: Community sanctions and measures. Basingstoke: Palgrave. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-71864-4

Chen Q (2020a) How China’s private sector helped the government fight coronavirus. The Conversation, 11 May. https://theconversation.com/how-chinas-private-sector-helped-the-government-fight-coronavirus-136100

Chen Q (2020b) Exploring the bottom-up reform of sex offender registration in China: Carceral feminism and populist authoritarianism. Crime Law and Social Change 74: 273–295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-020-09897-z

Chen X (2020) Spaces of care and resistance in China: public engagement during the COVID-19 outbreak. Eurasian Geography and Economics 61:435–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/15387216.2020.1762690

Chen Y, Mao Z and Qiu JL (2018) Super-sticky WeChat and Chinese society. Bingley: Emerald. https://www.emerald.com/insight/publication/doi/10.1108/9781787430914

Chinese Business Network (2020) NPC rep calls for the nationalisation of EMC services. 22 May. https://m.yicai.com/news/100639476.html

Cong W (2021) From pandemic control to data-driven governance: The case of China’s health code. Frontiers in Political Science 3: 627959. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2021.627959

Crawford A (2006) Policing and security as ‘club goods’: The new enclosures? In Wood J and Dupont B (eds) Democracy, Society and the Governance of Security: 111–138. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511489358

Deleuze G (1992) Postscript on societies of control. October 59: 3–7. https://www.jstor.org/stable/778828

Deng F (2014) Private governance under public constraints. Post-Communist Economics 26(3): 324–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/14631377.2014.937090

Ding X and Zhong DY (2020) Rethinking China’s social credit system: A long road to establishing trust in Chinese society. Journal of Contemporary China 30: 630–644. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2020.1852738

Fan W (2023) Representatives of NPC and CPPCC Debating the future of health codes. Southern Metropolis Daily, 13 March. https://m.mp.oeeee.com/a/BAAFRD000020230313772486.html

Foucault M (1977) Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison (translated by Alan Sheridan). London: Penguin Group.

Gill S (1995) The global panopticon? The neoliberal state, economic life, and democratic surveillance. Alternatives: Global, Local, Political 20(1): 1–49. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40644823

Global Times (2020) Outrageous: Homeowners vote to oust medical professionals. 10 February. https://tech.sina.com.cn/roll/2020-02-10/doc-iimxyqvz1724768.shtml

Guyer J (2022) What makes China’s wave of protests different this time. Vox, 30 November. https://www.vox.com/world/2022/11/30/23484801/china-protests-covid-lockdown-xi-jinping

Hall C and Pollard MP (2022) China tightens security after rare protests against COVID curbs. Reuters, 28 November. https://www.reuters.com/world/china/china-covid-cases-hit-fresh-record-high-after-weekend-protests-2022-11-28/

Harwit E (2016) WeChat: Social and political development of China’s dominant messaging app. Chinese Journal of Communication 10(3): 312–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/17544750.2016.1213757

He S (2015) Homeowner associations and neighborhood governance in Guangzhou, China. Eurasian Geography and Economics 56(3): 260–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/15387216.2015.1095108

He S and Wu F (2009) China’s emerging neoliberal urbanism: Perspectives from urban redevelopment. Antipode 41(2): 282–304. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2009.00673.x

Heater D (1999) What is citizenship? Cambridge: Polity Press.

Hu M and Sidel M (2020) Civil Society and COVID in China: Responses in an authoritarian society. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 49(6): 1173–1181. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764020964596

Huang J and Tsai KS (2022) Securing authoritarian capitalism in the digital age: The political economy of surveillance in China. The China Journal 88(1): 2–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.136467

Huang Y (2020) China’s approach to containing coronavirus cannot be replicated. Aljazeera, 23 March. https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2020/3/23/chinas-approach-to-containing-coronavirus-cannot-be-replicated

Huang YQ (2006) Collectivism, political control, and gating in Chinese cities. Urban Geography 27(6): 507–525. https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.27.6.507

Human Rights Watch (2022) China: Treatment for non-COVID illnesses denied. https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/04/06/china-treatment-non-covid-illnesses-denied

Hsieh H and Shannon SE (2005) Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research 15(9): 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687.

Iveson K and Maalsen S (2019) Social control in the networked city: Datafied dividuals, disciplined individuals and powers of assembly. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 37(2): 331–349. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775818812084

Ji W (2020) National Health Commission clarifies rules concerning returning workers. Workers’ Daily, 16 February. https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_6023041

Jiang F and Xie C (2020) Roles of Chinese police amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Policing 14(4): 1127–1137. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/paaa071

Krippendorff K (2022) Content analysis: An Introduction to its methodology. London: SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781071878781

Li BY (2010) The history and development of private security industry in China. Journal of Hunan Police and Security College 4: 25–28.

Li Y (2020) Confronting online scrutiny: Doing social science research in the context of internet censorship in China. Intersect 14(1): 1–9. https://ojs.stanford.edu/ojs/index.php/intersect/article/view/1651/1358

Li Y, Chandra Y and Kapucu N (2020) Crisis coordination and the role of social media in response to COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. American Review of Public Administration 50(6–7): 698–705. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074020942105

Liang F (2020) COVID-19 and health code: How digital platforms tackle the pandemic in China. Social Media and Society 6(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120947657

Liu C (2020) Chinese public’s support for COVID-19 surveillance in relation to the West. Surveillance and Society 19(1): 89–93. https://doi.org/10.24908/ss.v19i1.14542

Liu J and Zhao H (2021) Privacy lost: Appropriating surveillance technology in China’s fight against COVID-19. Business Horizons 64: 743–756. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2021.07.004

Loader I and Walker N (2001) Policing as a public good: Reconstituting the connections between policing and the state. Theoretical Criminology 5(1): 9–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362480601005001002

Loader I and Walker N (2006) Necessary virtues: The legitimate place of the state in the production of security in Wood J and Dupont B (eds) Democracy, society and the governance of security: 165–195. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511489358

Ma J and Zhuang P (2020) 5 million left Wuhan before lockdown, 1,000 new coronavirus cases expected in city. South China Morning Post, 26 January. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/society/article/3047720/chinese-premier-li-keqiang-head-coronavirus-crisis-team-outbreak

Mao L (2020) Imperative to reduce COVID-related discrimination. CPPCC Daily, 26 March. http://cppcc.china.com.cn/2020-03/26/content_75861075.htm

Ministry of Civil Affairs (2020) Building red EMCs and improve services for the people. https://www.mca.gov.cn/n152/n166/c42557/content.html

Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development (2009) Guidelines for Homeowner Associations and Executive Committees.

Mok B (1988) Grassroots organizing in China: The residents’ committee as a linking mechanism between the bureaucracy and the community. Community Development Journal 23(3): 164–169. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44256734

Municipal Government of Hangzhou (2020) Ten new measures for pandemic control. https://hznews.hangzhou.com.cn/chengshi/content/2020-02/13/content_7675071.htm

National Health Commission (2022) Notification on further improving the responses to COVID-19. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/gzzcwj/202212/8278e7a7aee34e5bb378f0e0fc94e0f0.shtml

NetEase (2020) Pet dog beaten to death in Xi’an for pandemic control, 12 February. https://www.163.com/dy/article/F56Q51CS05490CSD.html#

Pentland A (2013) The data-driven society. Scientific American 309(4): 78–83. https://doi.org/10.1038/scientificamerican1013-78

People’s Daily (2020) Block the transmission of the virus, not to block love. 30 January. https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1657105822071499449&wfr=spider&for=pc

Phoenix News (2020) Government of Xiaogan responding to community protest over profiteering, 13 March. https://news.ifeng.com/c/7unBrYeyF6m

Prior L (2014) Content analysis in Leavy P (ed.) The Oxford handbook of qualitative research. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199811755.001.0001

Reuters (2020) Under China’s coronavirus lockdown, millions have nowhere to go, 14 February. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-health-scale-idUSKBN2081DB

Shearing C and Burris S (2004) Changes in governance: A cross-disciplinary review of current scholarship. Akon Law Review 4(1): 27–50. https://ssrn.com/abstract=1116678

Shearing C and Wood J (2003a) Nodal governance, democracy and the new denizens. Journal of Law and Society 30(3): 400–419. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1410537

Shearing C and Wood J (2003b) Governing security for common goods. International Journal of the Sociology of Law 31(3): 205–225. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3443727

Shearing CD and Stenning P (1983) Private security: Implications for social control. Social Problems 30(5): 493–506. https://doi.org/10.2307/800267

Sina Technology (2020) Active users increased by 40% since the pandemic started. https://tech.sina.com.cn/i/2020-04-28/doc-iircuyvi0221459.shtml

Sohu News (2020) Confirmed! Holiday extended to February 10, 28 January. https://www.sohu.com/a/369239705_201370

Song Y (2022) Health codes must not be abused for excessive control. 24 June. http://www.gov.cn/fuwu/2022-06/24/content_5697533.htm

State Council (2020) Decision on improving the management of EMCs. 5 January. https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2021-01/05/content_5577326.htm

Tai Y and Fu K (2020) Specificity, conflict, and focal point: A systematic investigation into social media censorship in China. Journal of Communication 70(6): 842–867, https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqaa032

Tang Q (2023), Health codes gone, one billion personal data destroyed. National Business Daily, 3 March. https://pub-zhtb.hizh.cn/a/202303/03/AP640155e1e4b0626137f06687.html

Tang B (2015) Deliberating governance in Chinese urban communities. The China Journal 73: 84–107.

White A (2011) The new political economy of private security. Theoretical Criminology 16(1): 85–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362480611410903

Williams RW (2005) Politics and self in the age of digital re(producibility). Fast Capitalism 1(1): 104–121. https://doi.org/10.32855/fcapital.200501.008

Wong KDF, Li CY and Song HX (2007) Rural migrant workers in urban China: Living a marginalised life. International Journal of Social Welfare 16: 32–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2397.2007.00475.x

Wood J and Shearing C (2007) Imagining security. Cullompton: Willan Publishing.

Wu P (2022) Henan bank depositors slam government response to red health code saga. Six Tone, 15 June. https://www.sixthtone.com/news/1010556/henan-bank-depositors-slam-govt-response-to-red-health-code-saga

Wu W (2002) Migrant housing in urban China: Choices and constraints. Urban Affairs Review 38(1): 90–119. https://doi.org/10.1177/107808702401097817

Wu X (2020) Thumb up for the health code system. Xinhua News, 23 March. http://m.xinhuanet.com/hn/2020-03/23/c_1125752756.htm

Xu J, Sun G, Cao W, Fan W, Pan Z, Yao Z and Li H (2021) Stigma, discrimination, and hate crimes in Chinese-speaking world amid Covid-19 pandemic. Asian Journal of Criminology 16: 51–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-020-09339-8

Yang Z, Zhu G, Li LC and Sheng Y (2021) Services and surveillance during the pandemic lockdown: Residents committees in Wuhan and Beijing. China Information 35(3): 420–440. https://doi.org/10.1177/0920203X211012822

Ye TQ and Ye N (2008) Challenges facing HAs in China’ in Li et al. (eds) Annual Report on the Development OF China’s Real Estate (No.5). https://www.pishu.com.cn/skwx_ps/bookdetail?SiteID=14&ID=2040433

Yu H (2017) Beyond E-Commerce: The social case of China’s digital economy. French Centre for Research on Contemporary China. https://www.cefc.com.hk/article/editorial-beyond-e-commerce-social-case-chinas-digital-economy/

Yu N (2020) China’s property management industry: A major beneficiary from COVID-19. https://www.eastspring.com/sg/insights/china-s-property-management-industry-a-major-beneficiary-from-covid-19

Zhang Y (2020) Health codes of Hangzhou shall be rolled out nationally. People.cn, 24 February. http://society.people.com.cn/n1/2020/0224/c1008-31600444.html

Zhang J, Bate J and Abbott P (2022) State-steered smartmentality in Chinese smart urbanism. Urban Studies 59(14): 2933–2950. https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980211062888

Zhu Y and Fu K (2021) Speaking up or staying silent? Examining the influences of censorship and behavioral contagion on opinion (non-) expression in China. New Media & Society 23(12): 3634–3655. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820959016

Zhong LY and Grabosky PN (2009) The pluralization of policing and the rise of private policing in China. Crime, Law and Social Change 52: 433–455. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-009-9205-1.

Zuboff S (2019) The age of surveillance capitalism. London: Profile Books.

[1] The term ‘community’ is used as the Chinese equivalent of ‘xiaoqu’ in this paper. Some studies call Chinese xiaoqu ‘urban living blocks’. The author decided not to use this translation, as it suggests that Chinese xiaoqu are mere buildings and spaces without any political life, and as discussed in this paper, this is not true. However, readers are advised that the political organism of a Chinese xiaoqu differs to that of a western community.

[2] The word 'grassroots' refer to the lowest level of entities and organisations in localities.

[3] State police’ refers to the state-funded public security force (gong’an). This force is led by the Ministry of Public Security in China. At the local level, it comprises the bureaux of public security and grassroots police stations.

[4] In this paper, police service strength refers to the number of formal police officers per 10,000 population in a specific country.

[5] In this paper, the phrase ‘HAs’ refers to formal HAs only. Informal HAs are specifically identified as ‘informal HAs’ or ‘WeChat groups of homeowners’.

[6] ‘Mass surveillance’ in this study refers to the collection, storage and analysis of personal data on a large scale for multiple purposes.

[7] The COVID-19 pandemic broke out during the Spring Festival 2020. Usually, the holiday period runs until 1 February 2020, but following the State Council’s emergency announcement on 26 January 2020, most provinces extended the holiday until 10 February (Sohu News 2020). Some special industries, such as public utilities and personal protective equipment manufacturers, assumed business earlier; however, most people did not return to work until 10 February 2020.

[8] In natural language processing, tokenisation means segregating sentences into smaller units, usually words.

[9] The RTF refers to the number of times a certain term appears in a corpus divided by the total number of terms in the corpus.

[10] Such representativeness is usually evidenced by the number of likes a post received. However, due to the information cocoon and transmission bias on social media, this is not a perfect indicator. Posts that were not ‘liked’ by many are also quoted if they articulated the mainstream opinion well, posed an interesting counterargument to the mainstream opinion or made a point particularly relevant to the research questions, hypotheses or theoretical framework of this study.

[11] 'Cadre' refers to officers working for the Chinese state bureaucracy.

[12] It should be noted that such involvement is usually subtle and indirect. For example, in a post published on 12 February 2020, the local police in Weifang provided a detailed account of how they were ‘actively involved’ in lockdown enforcement. According to the post, the Weifang police had processed 180 incidents of lockdown violations since January 2020. In 138 cases, the presence of the police alone was sufficient to calm down the frontline disturbances. Informal reprimands by a police officer usually resolved the conflicts between PSGs and disobeying citizens.

[13] Unless otherwise stated, the words in brackets were inserted by the author.

[14] ‘12345’ is the national consumer support line in China.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/IntJlCrimJustSocDem/2024/8.html