|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

International Journal of Regional, Rural and Remote Law and Policy |

Throw the Bathwater; Keep the Baby:

Reform of the Statutory Marketing Arrangement for Australian Rice

Tamaris Hoffman[1] and Andrew Lawson[2]

Australian Centre for Agriculture & Law, School of Law, University of New England, Armidale, Australia.[3]

We would like to thank the two representatives of two of the rice industry’s peak organisations for agreeing to be interviewed for this work. These interviewees remain anonymous in accordance with our research ethics approval.

Contents

Marketing of rice in the Australian State of New South Wales (NSW) is regulated by a statutory marketing arrangement (SMA) – the last such scheme in Australia. A key feature is the coupling of vesting (by which all rice grown in NSW belongs to a statutory board) with a single export desk. The rice industry argues only this process can ensure export price premiums (EPP) and freight scale advantages (FSA). The SMA is subject to periodic review, which has strongly advocated deregulated. Furthermore, there is increasing grower demand for liberalisation of the export market, and others argue the scheme is unconstitutional. However, the NSW Government has continually renewed the arrangement. This article contends that the single desk arrangement no longer accounts for the EPP and FSA advantages cited by the industry. Vesting provides non-economic benefits and it is argued that it should be retained, but the single desk abolished. Blanket dismantling of SMAs and deregulation in other agricultural commodities have had damaging social and economic consequences. These have been avoided by the rice industry through adaptation of their SMA over the last century. While the industry needs to accommodate greater competition and transparency, this is best achieved through reform rather than wholesale repeal.

|

ABL

|

Authorised Buyer’s Licence

|

|

COAG

|

Council of Australian Governments

|

|

CPA

|

Competition Principles Agreement

|

|

DPI

|

NSW Department of Primary Industries

|

|

EPP

|

Export Price Premium

|

|

FSA

|

Freight Scale Advantage

|

|

RMA

|

Rice Marketing Act 1983 (NSW)

|

|

RMB

|

Rice Marketing Board for the State of NSW

|

|

SEEL

|

Sole and Exclusive Export Licence

|

|

SMA

|

Statutory Marketing Arrangement

|

Rice is the world’s most popular grain for human consumption. Nine of the ten leading global producers of rice are in Asia – China, India, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Vietnam, Thailand, Burma, Philippines, and Pakistan. The top non-Asian producer is Brazil in tenth position globally. The leading consumers show a similar pattern, though Japan consumes more than Pakistan. Seven of the top ten rice exporting countries are Asian, with the USA coming in at fifth place as the leading non-Asian exporter.[4] Despite the dominance of Asia in rice production, export and consumption, rice is grown in every habitable continent, including Europe and Australia. Rice has high water consumption requirements, and is thus grown in regions with high rainfall or reliable irrigation water supplies.

Australia is a comparatively small player in terms of production, consumption and exports, and rice growing makes up about 0.4% of Australia’s agricultural production by value. However, Australia exports about 75% of its rice (depending on seasonal conditions), and has a reputation for a high quality product commanding premium prices. Australian rice comprises a modest 0.4% of total global rice exports. For the traditional rice-growing districts of Australia, the industry has historically been a mainstay of local economies, especially for communities in the towns of Leeton, Griffith, Deniliquin and Coleambally.[5] Despite being grown in mostly dry temperate regions and reliant on irrigation, Australian rice has a high water-use efficiency compared to global averages.[6]

In Australia, the industry is dominated by the Riverina region in the southern part of the State of New South Wales (NSW), centred primarily on the Murrumbidgee and Murray River floodplains. As shown in Table 1, 99% of Australian rice is grown in NSW.

Table 1: Australian rice production 2021-22

|

State/Territory

|

Area (ha)

|

Production (tonnes)

|

% National Production

|

No. rice farmers

|

|

NSW

|

61,597

|

685,448

|

99.13%

|

367

|

|

Victoria

|

129

|

1,680

|

0.24%

|

2

|

|

Queensland

|

623

|

3,317

|

0.48%

|

17

|

|

Northern Territory

|

200

|

1,000

|

0.14%

|

3

|

|

Total Australia

|

62,549

|

691,445

|

100%

|

389

|

Source: ABS, 2023[7]

Smaller quantities are grown in the State of Victoria (near its northern border with NSW on the same Murray River floodplain), the tropical States and Territories of Queensland, Western Australia and the Northern Territory.[8] Within NSW, a small but growing quantity is grown in the sub-tropical far north east of the State, in the Northern Rivers district near Lismore. As the Riverina region produces the lion’s share of Australia’s rice, the production, management and governance of the Riverina sector dominates the Australian industry.

The governance of rice production and marketing is unique in Australia, being the last major agricultural commodity protected by a statutory marketing arrangement (‘SMA’). Under the distribution of powers under the Australian Constitution, such arrangements are the purview of State Governments rather than a Federal (Commonwealth) Government matter. The NSW Government first legislated the arrangement in in 1928 under the Marketing of Primary Products Act and now under the Rice Marketing Act 1983 (‘RMA’).[9] What makes rice remarkable is that, despite SMAs historically operating across almost all Australian agricultural commodities, almost all have been disbanded, except for rice.

SMAs are specific schemes designed to regulate the marketing of commodities using executive powers that fall outside the usual legislation that governs trading.[10] Their principal aim is to stabilise prices and incomes for producers. This is achieved through a variety of methods that include:

(i) vesting – compulsory acquisition of the commodity by a statutory board;

(ii) single desk – the SMB has the monopoly on export rights;

(iii) pooling – an average price is offered for the commodity to all producers;

(iv) reserve price schemes – minimum export prices are guaranteed;

(v) production quotas – through limits on land tenure and use and water licences.[11]

The first two in this list – vesting and a single marketing desk – are the key methods used in NSW rice industry SMA.

This article explores the NSW rice industry SMA in four parts, beginning with this Introduction (Part 1). Part 2 outlines the history of agricultural SMAs in Australia. It highlights the important shift in the discourse in the 1990s as a result of the adoption of the National Competition Policy. This policy is generally antagonistic to SMAs. Opponents of SMAs argue they breach the Australian Constitution and offend competition theory and policy, which preferences deregulation of agricultural sectors, and abolition of any impositions on producers’ ability to sell rice to any buyer they choose in both domestic and international markets.

Next the article explores the NSW rice industry SMA in particular. It highlights the two key mechanisms underpinning the rice industry SMA – vesting and the single marketing desk. It also introduces the main argument used by the rice industry peak organisations (e.g. Rice Marketing Board, and Ricegrowers Association) to justify maintaining the current SMA for rice – namely, that the SMA results in valuable commercial gains for rice-growers in the form of export price premiums (EPPs) and freight scale advantages (FSAs).[12]

The fourth part of the article critically analyses this rationale for continuing the SMA. This article argues that there are legitimate concerns regarding competition and concludes that the industry’s success in regard to export price premiums and freight scale advantages cannot be wholly attributed to the SMA. However, the article also argues that other justifications support the retention of the part of the arrangements, and that competition concerns can be adequately addressed by reform of the SMA, rather than wholesale dismantling and deregulation. Complete deregulation has had damaging social consequences in other Australian farm sectors, which the rice industry has managed to mostly avoid.

The authors used a mixed methods approach comprising desk-top document analysis and key informant interviews. Documents analysed include the key legislation (Rice Marketing Act),[13] previous reviews (the six NSW Government Rice Vesting Reviews from 2010-2022, Rice Marketing Board Annual Reports from 2016–present, and independently commissioned reviews), and relevant literature relating to econometric analysis and modelling in the agricultural industry as well as socio-economic studies from other agricultural sectors.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with two key informants from two different rice industry peak organisations. Using key informant interviews is an effective means of gathering qualitative data to verify the on-ground experience of findings of document analysis. The number of interviewees was necessary limited by the constraints of the research project, and interviewees’ views cannot be generalised to industry participants as a whole. Nonetheless, the participants were selected for their extensive knowledge of the industry and its marketing arrangements, and could be expected to augment the desktop review with novel insights. Interviewing can reveal previously unpublished issues and opinions, which in turn helped to generate new insights to policy problems.[14] The interviews were approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the authors’ university.[15] The interviews were conducted via video-conference (Zoom) by the first author in April and May 2022, each taking about an hour. The interviews and the reviews were uploaded to NVivo software for coding and analysis by the first author.

Australian Federal and State Governments have used SMAs as a means of protecting fledgling agrarian enterprises since the early part of the 20th century. This was advocated on the basis that agriculture was the main source of export revenue at that time.[16] By the 1920s, most Australian agricultural commodities were protected by SMAs.[17] Protection enabled these industries to raise and stabilise domestic prices, moderate international price volatility, minimise the market power of middlemen such as millers and traders and, offset the effect of import tariffs.[18] Historically, SMAs had the character of legislated co-operatives, designed to assist small, widely dispersed primary producers market their commodities using scales of economy in areas such as freight, storage, milling and sales.[19] SMAs relied on legal and administrative procedures to establish and maintain them, to exempt them from anti-competition legislation and to finance their boards.[20]

The mechanisms used by SMAs for controlling production and marketing are contentious in Australian constitutional law – particularly in relation to s 92 of the Australian Constitution, which provides that ‘trade, commerce, and intercourse among the States ... shall be absolutely free’. In the 1932 case of James v Cowan,[21] the Privy Council found that legislation enacted by the State Government of South Australia to allow for compulsory acquisition of all dried fruit grown within the State was contrary to s 92. It further struck down the Federal Government’s attempt to limit the amount of dried fruit that a producer could sell interstate.

However, the High Court established a different position in the late 1980s in the case of Cole v Whitfield.[22] The court adopted a two-part ‘discriminatory protectionism’ test, which allowed for SMA regulation, as long as it (i) Did not discriminate against interstate trade either on its face or in effect; and (ii) Had not been enacted for protectionist purposes.[23]

The decision was confirmed in the 1990 case of Barley Marketing Board (NSW) v Norman.[24] In that case, the Barley Marketing Board of NSW sued a NSW barley grower, alleging he had sold his grain to a Victorian trader in contravention of s 56 of the Marketing of Primary Products Act 1983 – the same act that applied to rice. Mr Norman defended his action on the basis the Act breached s 92. The High Court unanimously rejected his argument. While the High Court admitted that the scheme had some protectionist element in that it gave producers the benefit of the marketing board’s bargaining power, it did not discriminate against interstate trade as it applied equally to all NSW barley producers.[25] The court also conceded that the regulation did confer a benefit on producers within the state compared to those in other states.[26]

Gray posits that the one of the main difficulties with the current interpretation is the definition of protectionism and whether the test looks at its purpose or its effect.[27] He argues that removing the test for protectionism would result in s 92 invalidating SMAs entirely. Gray also disputes the definition of discrimination claiming the High Court narrowed its interpretation beyond the intent and spirit of s 92.[28] Instead, he argues, the test for discrimination should be broadened to include how the rule in contention influences the purchasing decisions of an interstate buyer.[29] He also contends that any smaller producer is automatically protected to a greater extent than the larger grower and that this consequently stifles competition.[30] The High Court’s current position is one of a ‘reasonable regulation’ exception. In other words, the fact that a law ‘imposes a burden upon interstate trade and commerce that is not incidental or, that is disproportionate to the attainment of the legitimate object of the law, is important in demonstrating that the true purpose of the law is not to attain that object but to actually impose the burden.’[31] At least for now, the NSW rice industry SMA appears not to breach s 92 of the Constitution on the current High Court interpretation.

The major challenge to SMAs came in the form of arguments about economic efficiency and the advent of policies fostering competition and deregulation. The Australian Productivity Commission argues that from the 1960s some SMAs were having negative effects on Australia’s agricultural economy including over-production, poor use of resources (particularly land, water, and labour) and stifling innovation.[32] From that time, commentators agitated for economically driven reform of marketing policy. Economist Jack Lewis argued that SMAs were primarily a means of price support that operated on the basis of narrowed interests and offered little to improve overall market performance.[33] Price support was principally achieved by diverting most of the commodity to export markets. Domestic prices were kept high through quotas, tariffs and embargoes on substitute product.[34] Furthermore, the rise of the mining industry in the early 1970s diversified the Australian economy and reduced the nation’s reliance on agricultural exports to pay off national debt. This consequently weakened the case for special protections for agriculture.[35]

The development of competition policy at a national level occurred around the time of the collapse of the wool industry SMA – the reserve price scheme. Under that arrangement, the Australian Wool Corporation (AWC) set a floor price for Australian wool and AWC acted as buyer of last resort, which would buy wool at the floor price, preventing it being sold for less. Historically, the floor price was meant to underpin the minimum cost of production and buffer wool producers against the vagaries of the global wool market. However, a series of changes to the governance of the floor price coincided with other macroeconomic factors, which resulted in the spectacular collapse of the scheme. The changes in governance allowed the floor price to be raised above minimum cost of production to a more aspirational level. This distorted the price signals to woolgrowers, who were effectively growing wool for the floor price, rather than a real market demand.[36]

Moylan noted that over several decades, the Australian wool industry had courted woollen mills and textile producers in communist bloc economies such as the USSR. These highly subsidised mills undercut the more commercially focussed mills in Europe and Australia’s own domestic woollen mills, sending many of them out of business. The house of cards came tumbling down with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the exposure of its wool processors to market forces. These geopolitical developments and other trends affecting consumer textile preferences resulted in the accumulation of an enormous stockpile of wool for which there was no immediate market.[37]

In propping up the floor price, the AWC exhausted its cash reserves and borrowing power maintaining the floor price, which was eventually abolished in 1991. The slow sell-off of the stockpile took a decade, at the same time depressing the wool market, and sending numerous Australian farmers and intermediaries to the wall. Such was the humiliating fall of the only globally traded agricultural commodity for which Australia was the world’s leading producer and exporter – the industry that had vitally supported Australia’s economy from colonial times into the middle of the 20th century.[38] The wool industry’s fate was probably on the minds of the commentators and policymakers who helped drive Australia’s competition policy in the early 1990s. The reserve price scheme for wool epitomised the potential ills of SMAs.

Lister outlines the worldwide ‘backdrop of economic rationalist policies’ that informed competition policy in Australia and promulgated market approaches, ‘deregulation, privatisation, lower protection and increased competition’.[39] These approaches were recommended by the Hilmer Inquiry – the Independent Commission of Inquiry into National Competition Policy, chaired by Professor Fred Hilmer and commissioned by the Council of Australian Governments (COAG – the ministerial forum representing all governments at the Federal, State and Territory levels of the Australian federation). In 1995, based on the Hilmer Inquiry recommendations,[40] COAG endorsed three instruments to give effect to a National Competition Policy – the Competition Principles Agreement (CPA), the Conduct Code Agreement, and the Agreement to Implement the National Competition Policy and Related Reforms.[41]

The ‘guiding principle’ of the policy is found in cl 5(1) of the CPA:

[L]egislation (including Acts, enactments, Ordinances or

regulations) should not restrict competition unless it can be demonstrated that:

(a) the benefits of the restriction to the community as a whole outweigh the costs; and

(b) the objectives of the legislation can only be achieved by restricting competition.

Key initiatives of these reforms relevant to this article include:[42]

• Regular assessment of Federal, State and Territory Governments’ progress on implementing the National Competition Policy;

• Tying payments of Federal grants to States and Territories to satisfactory progress implementing the National Competition Policy;

• Establishment by every government in the federation of gatekeeping mechanisms to ensure legislation complied with the policy.

The broad tenor of the Hilmer Report and development of the National Competition Policy aligned with the recommendations of policymakers in other reports and policy papers, which called for the deregulation of Australian agriculture in line with the micro-economic, anti-competitive and neo-liberal reforms of this period.[43] Statutory support schemes were rapidly dismantled – 15 SMAs existed in NSW in 1980, only seven remained into the 90s.[44] After Riverina Citrus was dissolved in August 2013,[45] the NSW rice industry remains the only major commodity supported by an SMA. The regular reviews of the rice SMA referred to in more detail below (six reviews since 1995) are a legacy of the NSW Government processes put in place to implement competition policy.

Watson comments that debate over the efficacy of SMAs ‘is a mixture of arguments about questions of fact, economic theory and measurement, and value judgements’.[46] Some analysts point out that a purely economic approach to SMAs fails to consider the entire picture. Export price premiums are derived from price differentiation, which in turn comes from strong marketing services.[47] Whether this is provided by an SMA or some other arrangement depends very much on the specific characteristics of the commodity, such as size of the industry, geographic concentration, distance to milling, storage facilities and freight, as well as value adding processes. The fact that every NSW Government, despite their political alliance, has consistently approved the arrangement simply because the majority of producers want it, speaks to reasons that transcend pure economic rationalism.[48]

Examining the SMA for the sugar industry in Queensland, Males found that the natural monopoly of the industry meant that anti-competition legislation made little sense.[49] Watson was also critical of the National Competition Policy that brought many SMAs under review, noting the policy was better suited to the reform of public utilities and infrastructure where any economic gain was likely to be much bigger than regulating smaller commodity sectors.[50] Kolsen critiqued the Hilmer Report arguing that its ‘one shoe fits all’ approach was ill-suited for industries that required specific subject matter expertise.[51]

In 2018, Mick Keogh, the Deputy Chair of the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission stated that agricultural markets ‘unfettered by regulation do[n’t] always deliver good outcomes.’[52] He noted that increased productivity and competition were hampered by poor market information and bargaining power. Ironically, regulation can be necessary to protect the competitive process.

While the dismantling of some SMAs have benefited their industries, the effect has not been uniform. In a comprehensive review of SMAs in South Australia, Cook charts the demise of several industries such as dried and canned fruit following deregulation.[53] Other commodities such as citrus and honey have thrived since their industries were deregulated.[54] In a review of deregulation of agriculture in New Zealand, which occurred in the early 1980s, Johnson found that while domestic markets were freed up, there was a reluctance to abolish export marketing boards.[55] The speed at which deregulation was introduced and its timing (coming at a period when world commodity prices were weakened), led to significant uncertainty amongst primary producers, particularly with regards investment and expansion.[56]

It is difficult to predict what would happen if the NSW rice industry is deregulated. Its uniqueness in the sense of its geographic concentration and the way in which rice is traded globally makes comparisons to other deregulated commodities difficult. The latest vesting review summarises the successes experienced in other industries such as the dairy and wheat commodity sectors since deregulation, citing higher farm gate prices, lower consumer prices, and increased productivity largely through the reallocation of resources to larger farms.[57] However, the marketing arrangement for rice is still supported by the majority of producers not only because its financial returns are satisfactory, but also because it is perceived as a fair system inclusive of all growers.[58]

The dollar costs alone of deregulation are considerable. In 2016, following the deregulation of the potato industry in the State of Western Australia, the state government spent $14 million in assistance to help farmers transit through the process.[59] When the sugar industry in the State of Queensland was deregulated in 2006, the Federal Government paid out over $400 million in assistance that included payments for regional and community projects, income support, retraining, crisis counselling and intergenerational transfer.[60] Ironically, the industry was partially re-regulated in 2015 following growers’ concerns over milling profits not being passed on – one of the primary arguments that led to SMAs for sugar being established in the early part of the 20th century.[61]

Cook also notes that while marketing arrangements for many SA agricultural products in the State of South Australia were unfettered due to deregulation, paradoxically, they now face even more control in the form of phytosanitary and hygiene standards and occupational health and safety regulations.[62] Vanclay observed that deregulation led to a loss of about a quarter of all Australia’s primary producers by the end of the 1990s.[63] With that, has come the loss or degradation of many small rural and regional centres who relied on farming to keep them alive.[64] The social costs are significant.

Wheat – one of Australia’s largest agricultural commodities – underwent a series of policy changes between 1989 and 2012, and was finally deregulated in 2013. In a study that focussed on the socio-economic effects of deregulation, O’Keefe and Naeve interviewed wheat farmers in the western part of the State of Victoria a few years after deregulation. They found that growers had less bargaining power as there were fewer traders who could offer guaranteed prices. This decreased rather than increased competition. Furthermore, growers felt politically disempowered because deregulation had been introduced against their wishes. Deregulation meant that many farmers now had to take on marketing roles that had previously been fulfilled by the SMA on their behalf, including navigating legislation, obtaining and interpreting market information and negotiating deals. As a result, there was a feeling of financial and social insecurity. Many farmers felt at the mercy of grain traders – the very situation that had historically led to the development of the SMA.[65] O’Keefe argued that the use of econometric modelling came at the cost of ‘subtly marginalising the significance of [grower’s] concerns and the importance of social and environmental consequences of industry policy’.[66]

Buggle argues that while economic efficiency must largely determine the survival of SMAs, the real answer lies in a delicate balancing act.[67] Alternative marketing arrangements must be effective in meeting the particular economic conditions of the commodity and, the cost of entering and complying with any new arrangements cannot be greater than those of the original SMA.[68] He also criticises the definition and methodology of assessing the so-called benefits of removing restrictive trade practices.[69]

The NSW rice industry SMA provides for two main functions:

1. Vesting – whereby all NSW grown rice is vested in (belongs to) the Rice Marketing Board (‘RMB’) except that sold directly into the domestic market;[70] and

2. A single desk marketing arrangement – whereby the RMB appoints a sole and exclusive export licence holder (‘SEEL’) as single desk marketing agent[71]. The current SEEL holder is Ricegrowers Ltd trading as SunRice. The RMB also regulates the domestic sale of NSW grown rice by licencing authorised buyers (Authorised Buyers Licence – ‘ABL’).[72]

Table 1 outlines the evolution of the NSW rice industry SMA and its key organisations. The table shows the rice industry shares a similar pattern as other agricultural sectors, with statutory protections dating from the early part of the 20th Century to nurture a fledgling industry. From the mid-1990s, with the reforms in competition policy, the SMA came under increasing scrutiny, with no less than six reviews, the latest in 2021/22.

Legislation for vesting dates back to the 1980s when the NSW Government formalised the arrangement in response to a slump in international rice prices. At the time, heavily subsidised US farmers dumped large quantities of rice on the global market and Australian rice producers approached the Federal Government for direct assistance.[73] This resulted in a Federal Industry Assistance Commission review that unequivocally rejected any form of underwriting assistance to the industry even in the short term.[74] In fact, it went further and recommended that the SMA be entirely dismantled and hinted that consideration be given to prosecuting the RMB for breaches of the Trade Practices Act.[75]

In response, the NSW Government totally repealed the original 1928 Marketing of Primary Products Act and took the opportunity in replacement legislation to vest the RMB with ownership of all NSW grown rice.[76] The rice industry itself cut costs by reducing the duplication of functions (mostly in milling and storage) between the RMB and the Ricegrowers Co-operative. Under the new arrangement, the RMB retained ownership of storage holdings and, following s 50(1) of the new legislation, it appointed the Co-operative as its agent. This effectively meant that the Co-operative (now known as Ricegrowers Ltd) dealt directly with growers for the purchase of rice. This body now trades as SunRice and in 2006 it was granted sole and exclusive rights to export NSW rice.

Table 2: Evolution of the NSW rice industry statutory marketing arrangement and review

|

Year

|

NSW Rice Industry Development

|

|

1924

|

Rice grown commercially in Riverina

|

|

1925

|

Murrumbidgee Irrigation Area Ricegrowers’ Co-operative Society

formed

|

|

1928

|

Marketing of Primary Products Act 1928 (NSW) enacted. Rice Marketing

Board established

|

|

1930s-50s

|

Murrumbidgee Irrigation Area Ricegrowers’ Co-operative Society

undergoes a series of collapses and disbanded. Formation of Ricegrowers’

Co-operative. Milling operations secured by ricegrowers.

|

|

1955

|

Sunwhite brand launched. Rice growing expands in Riverina

|

|

1970 -1980

|

World surplus of rice. Import tariffs on rice reduced. Decreased returns to

growers. Industry calls for government support.

|

|

1983

|

Marketing of Primary Products Act 1983 (NSW) replaces 1928 Act

|

|

1985

|

Relationship between Rice Marketing Board and Ricegrowers’

Co-operative rationalised to reduce costs. Board assumes vesting

powers. Co-op

becomes Ricegrowers Co-operative Ltd

|

|

Late 1980s

|

Australian growers recover as world shortages of rice affect Asia.

|

|

1995

|

Ricegrowers Co-operative Ltd forms joint venture with Japanese mill to form

SunRice. 1st review of the SMA (‘Rice Vesting

Review 1995’) under the National Competition Policy Review

|

|

2000

|

SunRice becomes trading name of Ricegrowers Co-operative Ltd

|

|

2005

|

Ricegrowers Co-operative Ltd becomes Ricegrowers Ltd. 2nd

review of the SMA (‘Rice Vesting Review 2005’)

|

|

2006

|

Marketing of Primary Products Act 1983 (NSW) changed names to become

Rice Marketing Act 1983 (NSW). Domestic rice trade deregulated. Sole

& Exclusive Export Licence granted to SunRice.

|

|

2010

|

3rd review of the SMA (‘Rice Vesting Review

2010’)

|

|

2012

|

4th review of the SMA (‘Rice Vesting Review

2012’)

|

|

2016

|

5th review of the SMA (‘Rice Vesting Review

2016’)

|

|

2018

|

SunRice listed as a public company on the Australian Stock Exchange.

Drought reduces production to lowest in a decade.

|

|

2021/22

|

6th review of the SMA (‘Rice Vesting Review

2021’)

|

Sources: Kealey, Hedditch and Clampett 2000; Sunrice (undated).[77]

However, it was clear that the SMA continued to breach the Competition Principles Agreement (CPA) to which NSW was a signatory.[78] To maintain the arrangement, COAG insisted it met the threshold test in the ‘guiding principle’ of cl 5(1) – i.e. the public benefits of the arrangement must outweigh any costs, and the benefits must only be achievable by restricting competition.[79]

Just how public benefits were to be calculated and the costs compared were never articulated in the CPA. In fact, under the CPA, the party engaged in the arrangement was free to provide whatever evidence they chose to demonstrate compliance with the test.[80] The only requirement was any legislation enacted to implement the arrangement had to be reviewed at least once every ten years.[81] The current statutory review requirements under the RMA and the obligations under the Subordinate Legislation Act mean the SMA for rice is re-evaluated every five years.[82] The key indicators used to measure benefits are export price premiums and freight scale advantages.

In 2006, the NSW Labor Government finally deregulated the domestic market for rice.[83] This had followed mounting pressure from the Federal Government and the National Competition Council in the form of stiff financial penalties.[84] Although the new legislation abolished vesting in the domestic market, it maintained partial control through a licensing system. The RMB vetted anyone wishing to trade on the domestic market before issuing a licence. Licence fees consisted of a fixed flat rate plus a variable charge based on the amount of rice purchased and were issued annually. The legislation did not alter the single desk export arrangement and all rice not sold on the domestic market was still vested in the RMB.

Despite this, the 2016 Rice Vesting Review commented there was growing discontent amongst the Northern Rivers rice growers in northern NSW with regard to the restrictions on domestic trading.[85] Lack of warehouses and mills in the north of the state meant that Northern Rivers rice producers were becoming increasingly dissatisfied with a system that forced them to sell to a buyer (SunRice) several hundred kilometres away while incurring greater costs in transport and handling.[86] The alternative – to sell into the domestic market – was hampered by the Authorised Buyer’s Licence system (ABL) and competition from cheaper overseas rice.

Previous reviews considered the variable fee an impediment to domestic market growth and suggested that SunRice meet the deficit in exchange for their exclusive right to export.[87] They also advocated the RMB make more liberal use of its vesting exemption provisions under s 57 of the RMA to encourage domestic competition.[88] In response, during the 2018-2019 season, the RMB abolished the $500 fixed annual ABL fee and reduced the variable fee to $2.50/tonne.[89] For the 2019-2020 period it reduced the variable fee to $2/tonne and drew on its own reserves to meet its operational costs.[90] The 2021 Rice Vesting Review makes little reference to domestic marketing arrangements except to note that Northern Rivers farmers still perceive a conflict of interest in the ABL process.[91]

The RMB points to the fact that the number of authorised buyers has increased steadily over the years and a 14th licence has been issued in the last season.[92] The due diligence involved in issuing the licences means that no rice grower has been left stranded by a merchant unable to pay as pledged as recently occurred in the NSW cotton industry.[93] Licensing fees have covered the RMB’s annual operating costs since deregulation, ensuring there is no cost to the tax-payer for maintenance of the SMA.

The current domestic market arrangements illustrate the flexibility of the SMA and the ability of the RMB to respond quickly and appropriately to changes affecting the industry. The impartiality of the RMB also means that consideration is given to factors affecting the whole of the industry and are not motivated by purely commercial interests. The knowledge and experience acquired over the years in the process of adaption would be lost if the industry were suddenly deregulated – a situation seen repeatedly in other commodity sectors after dismantling protective legislation.[94]

The latest Rice Vesting Review (2021) comments that while ‘vesting is a nuanced and complex topic, identifying the costs and benefits of the legislation is imperative in making informed and objective recommendations on the future of these arrangements.’[95] It also acknowledges that every review to date has grappled with determining how much vesting actually contributes to obtaining the best export price for Australian rice.[96]

The rice industry peak organisations have always maintained that vesting and the single desk arrangement have provided benefits primarily in the form of export price premiums and freight scale advantages.[97] In addition, are the many non-economic benefits that vesting confers which are difficult to quantify. These include certainty for producers by acting as buyer-of-last-resort, efficient use of expensive storage and milling facilities, cost-effective use of research and development funding, support for regional economies through employment and investment, and compensation for international market distortions due to state-controlled agencies.[98] Further, it argues, it is only through vesting these benefits can be realised.[99]

The SMA for rice is controversial and all of the six reviews into the SMA have highlighted competition and transparency concerns. For example, the second Vesting Review in 2005 argued that pooling and price equalisation (processes in which rice is collectively stored and milled according to variety and then an average price paid to each producer after collective costs of marketing have been deducted) obscured market price signalling.[100] The reviewers proposed that SunRice report separately on payments made for different rice grades and varieties and on bonuses given to growers on the basis of crop grown per hectare.[101] They also wanted to see Sunrice provide an analysis of the individual costs to growers for transport and milling arrangements.[102]

In 2021/22, the NSW Department of Primary Industries (‘DPI’) completed the sixth review of the scheme claiming that vesting is currently restricting the development of both domestic and export markets and hampering innovation within the rice industry.[103] The report also maintained it conferred no net benefit on rice farmers or the community.[104] Nevertheless, the NSW Government has granted a five-year extension to the vesting arrangements to 30 June 2027.[105]

With regard to industry claims that the SMA are necessary to secure export price premiums and freight scale advantages, the authors of this article argues there is little evidence to support the RMB and rice industry’s claims that vesting and the single desk are responsible and vital in protecting these export market benefits. Retaining vesting but abolishing the single desk would arguably retain the benefits of vesting but facilitate the development of more competitive domestic and overseas markets. Export price premiums and freight scale advantages are discussed in more detail below.

A detailed analysis of the six vesting reviews reveals that, although the NSW rice industry does deliver considerable economic and social benefits to the State, none of them can be directly correlated with vesting or the single desk arrangement. Most of the econometric modelling that has been used over the last 30 years to prove that vesting and price premiums are linked, has been flawed in terms of incomplete data and reliance on inappropriate alternative models as surrogates for a no-vesting scenario.[106] Furthermore, the legislation mandates vesting as a pre-condition to the single desk arrangement. The two provisions are actually quite separate and can work independently of each other.

As mentioned above, rice growers in the Northern Rivers region of NSW, well outside of the traditional Riverina rice-growing districts, were dissatisfied with SMA, particularly the Authorised Buyers Licence scheme for domestic sales, which was seen as an unnecessary and costly bureaucratic restriction.[107] However, as niche rice-growing in the form of organic and special varieties has developed, more and more growers became unhappy with the SMA. In the 2016 review, only 7% of all growers opposed the arrangements.[108] In 2021 this figure increased to 22%.[109] Growers’ discontent extended beyond the domestic market arrangements to the statutory connection between vesting and the export licencing mechanism – the Sole and Exclusive Export Licence (SEEL). As one of the rice industry peak organisation interviewees commented:

[T]he Northern Rivers growers ... don't want vesting to be scrapped they just want the ability to export as well ... [not independent of the RMB] but independent of SunRice who is the holder of the SEEL.[110]

Discontent with the SEEL is also becoming increasingly evident amongst southern farmers. As part of its submission to the 2012 Review, the Burrabogie Pastoral Company Ltd, a large Riverina rice producer, independently engaged Deloitte Access Economics to investigate SunRice’s claims that export premiums were linked to the single desk arrangement.[111] On the basis of the investigation, Burrabogie argued that the legislation prevented it from developing export markets for its particular rice varieties.[112] It was joined by organically certified rice growers who submitted they could earn higher returns under their own export arrangements. As part of the review, the NSW Department of Primary Industries (DPI) independently assessed the Deloitte findings. It found the analysis flawed largely due to a lack of reliable data on costs of production and pricing to individual markets, as well as imperfect comparison modelling based on the Californian rice industry.[113]

Despite acknowledging its limitations, the DPI used the Deloitte methodology as a basis for its econometric modelling in the 2021 vesting review.[114] On this occasion, the DPI at least had access to individual market data but in every other respect, the analysis was plagued by the same shortcomings experienced in the 2016 vesting review report. It continued to use the Californian rice market to simulate a no-vesting situation even after admitting that SunRice actually exported rice from California under its own brand.[115] In other words, it was impossible to discriminate between Australian and American exports into various overseas markets. The NSW Productivity Commission also appointed the Centre for International Economics (CIE) to run an independent assessment. The CIE was even further stymied as it had no access to the DPI submissions and several ricegrowing organisations (including the RMB, SunRice and the Ricegrowers Association) refused to release their data for analysis.[116]

The inability to directly correlate vesting to export price premiums was an issue as far back as 2001. Using confidential data provided by Ricegrowers Co-operative Ltd for four different export markets, a study conducted by the NSW Department of Agriculture found although price premiums existed in all markets, these resulted from price discrimination practices – i.e. the ability to sell the same product at different prices to different markets.[117] Griffiths and Mullen found that SunRice was able to use market power in the form of ‘service bundles’ in order to tap into the higher end markets.[118] These service bundles included quality assurance, reliability of supply, provision of credit, promotional visits, and transportation costs. They concluded that a single market desk was not responsible for price premiums.[119]

The RMB is not opposed to change in the SEEL arrangements. Although SunRice has held the SEEL since 2006, as one of the rice industry peak organisation interviewees commented:

[W]e are not wedded to SunRice being the holder of the sole exclusive licence for time immemorial... if [a] party wanted a second licence from the RMB [it] would approach the RMB and give us a sense of their proposition, give us a sense of how they're going to finance it and how they're going to expand, what they see their scale being over what time....

Then the RMB has to weigh up, whether or not that arrangement is in the interest of the rice industry as a whole. But we're obliged to act on behalf of the industry as a whole, ... we would have to go to government and say, you know, we think there's a case for a second licence, and the government would have to indicate that it was happy for that to happen.[120]

In response to mounting criticism in 2018, the RMB commissioned an independent review into the viability of a rice industry in areas outside the Murray-Riverina area.[121] The report differed from the DPI reviews in that it did not examine the merits of vesting as a whole nor did it investigate any potential benefits of a second export licence to the Northern Rivers producers. The investigation found the main constraints on expansion in the upland area of NSW were unpredictable rainfall, limited storage and milling facilities and lack of research into the development of suitable strains for the region.[122] The report could not validate the significance of export markets largely because Northern Rivers producers refused to share any commercially sensitive information.[123] The latter is a recurring theme. The RMB has encountered similar difficulties. The interviewee noted:

[T]he extent to which the Rice Marketing Board can improve the arrangements for the smaller growers who want to act independently depends, in part, on them providing reasonable information that we can work with.[124]

According to this interviewee, part of the problem has been the historic under-reporting by Northern Rivers farmers of crop size.[125] This is evidenced by the discrepancy between the Research and Development (R&D) levies paid to the RMB (which are on a per tonne basis) and their reports of crop size to the NSW Department of Primary Industries.[126]

While there is no doubt that NSW rice attracts export premiums, there is little evidence to show a direct correlation to vesting or the single marketing desk. These mechanisms may have contributed to the success of the industry during the early part of the last century but it is evident now that brand marketing is largely responsible for export advantages. Given the relatively small size of the industry and the predominance of SunRice, it is highly unlikely that abolishing the single desk will affect its market share. It will however give a variety of producers the opportunity to test their market strength independently and competitively. While retaining a co-ordinated approach may be important, it is not the same as a single desk arrangement. To this end, continuing vesting means the RMB would be able to maintain a disinterested oversight at the same time as applying the considerable other benefits from vesting such as buyer-of-last-resort provisions. These modifications are all possible within the current legislative framework without the need to resort to total deregulation.

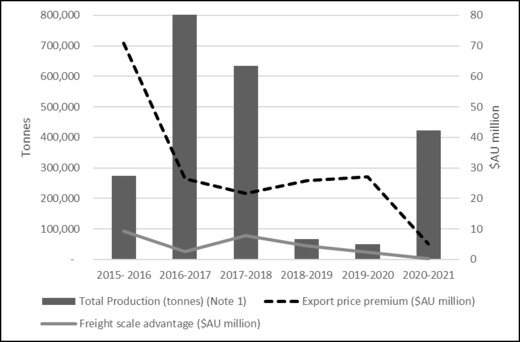

In its report on SMAs in 1991, the Federal Government Industry Commission noted that while vesting may produce economies of scale for freight, insurance and market services, any benefits may be undermined by ‘cost padding practices which can arise in the absence of competition.’[127] The Federal Government’s Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Economics (‘BITRE’) notes that benefits are highly dependent on the volume of commodity shifted and that their value is a best-guess based on discount ranges offered by freight companies.[128] Figure 1 shows the export price premiums and freight scale advantages reported by the RMB since 2015. Significantly, the independent assessors who verified these figures had no access to the individual discounts applied to shipping to individual markets. Figures quoted are those based on the BITRE method and cannot be separated for commercial-in-confidence reasons. Accepting these figures at face value and assuming that between 70-85% of rice produced is exported, it is difficult to discern any logical pattern that links export price premiums, freight scale advantages and production. This suggests that other factors besides the actual amount of rice exported is responsible for price premiums and lends support to the argument that vesting is not necessary in achieving those premiums. It could however, sustain an argument for a co-ordinated approach to export arrangements ensuring a greater proportion of the product is directed to higher paying markets with little or none reaching low paying markets during years of low production. However, even this does not necessarily rely on a single desk arrangement.

Figure 1: Total rice production, export price premiums (EPP) and freight scale advantages (FSA) for NSW rice 2015-2021

Sources: Total Production from ABS 2022.[129] No data available on proportion of total production exported due to confidentiality restrictions. EPP and FSA based on RMB Annual Reports 2017-2021.

In addition to questioning the strength of export price premiums, the Deloitte Economic Review commissioned by Burrabogie Pastoral Company, challenged the freight scale advantages.[130] They argued that it was Australia’s proximity to its major markets in the Pacific (PNG and New Zealand) that provided shipping benefits.[131] The 2016 Rice Vesting review did not address the issue of freight scale advantages, possibly because its analysis relied heavily on the Californian rice market to compare costs.[132] California bulk ships both long and medium grain rice. There is considerable market division between the two varieties making it almost impossible to adjust for differences.[133]

The latest vesting review notes the impact COVID-19 has had on global trading, particularly the interruption to shipping timetables, the accumulation of containers in the US and the consequent premium prices demanded for containers once travel restrictions were eased.[134] The review was highly critical of the RMB’s reliance and acceptance of freight scale advantages based on a range of rebates provided by a number of shipping lines rather than the actual discounts applied.[135] It remarked that as SunRice also imported rice, any freight advantage it negotiated must necessarily include this – a factor that has nothing to do with either vesting or the single desk policy.[136] It also revealed that as SunRice exports packaged product (anything up to 10 kg) ready for immediate retail sale, it relies largely on 20-foot food-grade containers.[137] In calculating freight scale advantages, most data is only available for 40-foot containers. While the report did not openly dispute SunRice’s assertions on economies of scale used to calculate freight scale advantages, it certainly did not support the contention that removing vesting would affect any scale advantages. In this regard, it is more than likely that freight scale advantages can no longer be used as an argument to support either vesting or the single desk policy.

Although the legislative amendment in 2007 prevented the Board from granting multiple export licences, there is no reason why this cannot be reversed. It is evident that any ability to extract export price premiums is now largely due to pricing-to-market practices and does not rely on single desk trading. By legislating to separate vesting and the SEEL, the perceived anti-competition practices could be removed at the same time as retaining many of the benefits of vesting. These could include attaching a buyer-of-last-resort stipulation to any export licence issued. It would also allow confidential commercial oversight of licensees to ensure that producers were paid under contracts and not left stranded if traders became insolvent.

Continuation of vesting would mean the RMB would retain control over the ABL system while simultaneously scrapping the remaining fees and charges, recouping its operational costs through the export licencing arrangement instead. There would be a potential for more domestic traders once any financial barriers have been removed.

More exporters mean more options for growers to sell their rice in different ways. SunRice already offers fixed contracts to some producers, but futures contracts, contracts based on special characteristics such as organic certification or rice variety and contracts where one company undertakes the milling and processing and another handles the marketing are all possible.

As Watson notes ‘the debate over the single desk is a mixture of arguments about questions of fact, economic theory and measurements, and value judgements.’[138] Despite the steady attack on the rice SMA over the last 30 years, it appears there is little appetite for its dismantling – certainly not from the majority of rice producers, their communities or the NSW Government. Reform, rather than repeal, of the SMA could address the main problems of the SMA. This article argues the single desk policy could safely be abolished without the risk of losing export price premiums. The industry is secure enough to back producers who want to test the waters in export markets for themselves. The legislation needs only be amended to shear vesting from the single desk policy and allow the RMB to appoint exclusive rather than a sole licensee to export.

Maintaining vesting however, provides the RMB with the mechanism to ensure an independent and thorough licensing process is undertaken. This further ensures that no grower is left out in the cold for payment or for a market for their crop. Concentrating on export licences means that domestic licences could either be abolished or be issued without charge.

Although the Australian rice industry is small, it has thrived despite the vagaries of weather, global market collapses and government policy. Although this may have in large part derived from the protectionism afforded it by the original marketing arrangements over a century ago, it has demonstrated that flexibility in those arrangements have enabled it to successfully adapt to changing markets and policies. This provides strong support for continuing to use the existing framework to respond to new challenges. Totally dismantling the SMA would be akin to throwing the baby out with the bath water.

Deregulation is expensive in terms of government support required in assistance during the transit period. It also results in the loss of knowledge, expertise and experience that inevitably accumulates through years of industry development. Economic rationalism is cold comfort for growers, their families and communities when there is a loss of culture, a sense of abandonment and a concern for missed opportunities. The marketing arrangement for Australian rice can be changed to address issues of competition, through consultation with those on the ground and through considered and perceptive amendment to current legislation and policy rather than deregulation.

KEYWORDS: Australian rice industry, statutory marketing arrangements, agricultural protection, deregulation

|

Abbott, Malcolm and Merrett, David, ‘Counting the Cost: The Reserve

Price Scheme for Wool 1970-2001’, (2019) 63 Australian Journal of

Agricultural and Resource Economics, 790-813 DOI:

10.1111/1467-8489.12337

|

|

Aither Pty Ltd, Expanding the NSW Rice Industry: Independent Review of

the Viability of Developing the Rice Industry Outside the Murray and Riverina

Regions (Final Report for the Rice Marketing Board NSW, 31 May 2018)

|

|

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), ‘Cereal and other Broadacre

Crops: Cotton and Rice Production, 2015-16 to 2020-21’,

Agricultural

Commodities, Australia 2020-21 (Web page, 26 July 2022)

<https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/industry/agriculture/agricultural-commodities-australia/2020-21#cereal-and-other-broadacre-crops>

|

|

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), Agricultural Commodities,

Australia 2021-22 (Catalogue no AGCDCNAT_STATE202122, 17 January 2023).

|

|

Australian Department of Agriculture, Forestry & Fisheries, Rice

(Web page, updated 4 November 2019)

<https://www.agriculture.gov.au/agriculture-land/farm-food-drought/crops/rice>

|

|

Australian Department of Agriculture, Water & the Environment, Post

Implementation Review- Competition and Consumer (Industry Code – Sugar)

Regulation 2017 (Sugar Code of Conduct) (10 December 2021)

|

|

BITRE, Freightline 6 – Australian Rice Freight Transport

(Australian Government, 2018)

|

|

Buggle, Geoff, ‘Is there a case for State Statutory marketing

Arrangements?’ (Conference Paper, Annual Conference

of the Australian

Agricultural Economics Society, 9-11 February 1993)

|

|

Cook, Venton, Rural Market Regulation and Legislation in South

Australia (Research Paper, South Australian History of Agriculture Group,

September 2021)

|

|

Fell, James et al, ‘Australian Rice Markets in 2020’, ABARES,

10(2) Agricultural Commodities, June quarter 2020

<https://www.agriculture.gov.au/abares/research-topics/agricultural-outlook/rice>

|

|

Gray, Anthony, ‘Compulsory Marketing Schemes and Section 92 of the

Australian Constitution’ [2014] UTasLawRw 17; (2014) 33(3) University of Tasmania Law

Review 317

|

|

Griffith, Garry and John Mullen, ‘Pricing-to-market in NSW rice

export markets’ (2001) 45(3) The Australian Journal of Agricultural and

Resource Economics 323, DOI: 10.1111/1467-8489.00146

|

|

Hilmer, Frederick, National Competition Policy (Independent

Commission of Inquiry into National Competition Policy Report to COAG, 25 August

1993)

|

|

Industry Assistance Commission, Parliament of Australia, The Rice

Industry (Parliamentary Paper No. 385, 23 October 1987)

|

|

Industry Commission, Statutory Marketing Arrangements for Primary

Products (Report No. 10 to the Australian Government, 26 March 1991)

|

|

Integrated Marketing Communications Pty Limited (IMC), Review of the NSW

Rice Marketing Act 1983 (Report for the NSW Department of Primary

Industries, October 2010), 4 (‘Rice Vesting Review

2010’)

|

|

Johnson, RWM, Schroder, WR and Taylor, NW ‘Deregulation and the New

Zealand Agricultural Sector: A Review’ (1989)

57 Review of

Marketing and Agricultural Economics 47, 58 DOI:

10.22004/ag.econ.12445

|

|

Kealey, Lucy, M R C Hedditch and Warwick Clampett, ‘History of rice

growing in Australia’ in L M Kealey and W S Clampett

(eds), Production

of Quality Rice in South Eastern Australia (Rural Industries Research and

Development Corporation, 2000)

|

|

Keogh, Mick, ‘Australian agribusiness law: sensible regulation, or

red tape gone mad?’ (Address, Third Annual Australian

Agribusiness Law

Conference, 17 May 2018)

|

|

Kolsen, Ted, ‘Microeconomic Reform and National Competition Policy:

Misconceptions and Problems’ (1996) 55(2) Australian Journal of

Public Administration 83, 84 DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-8500.1996.tb01205.x

|

|

Lewis, Jack, ‘Organized Marketing of Agricultural Products in

Australia’ (Address, Conference of Australian Agricultural

Economics

Society, 15-17 February 1961)

|

|

Lyster, Rosemary, ‘(De)regulating the Rural Environment’ (2002)

19(1) Environmental and Planning Law Journal 34

|

|

Majchrzak, Ann, and Markus, M Lynne, ‘Obtain New Evidence’ in

Ann Majchrzak and M Lynne Markus (eds), Methods for Policy Research:

Taking Socially Responsible Action (SAGE online version, 2014) DOI:

10.4135/9781506374703

|

|

Males, Warren, ‘A Case for Statutory Marketing Arrangements’

(Annual Conference of the Australian Agricultural Economics

Society, 10-12

February 1992)

|

|

Massy, Charles, Breaking the Sheep’s Back: The Political

Destruction of the Australian Wool Industry (University of Queensland Press,

2011)

|

|

Moylan, Fred, U-Turn for Wool: A Radical Solution to the Problems of the

Wool Industry (New Street Books, 1991)

|

|

National Competition Council, ‘About the National Competition

Policy’, National Competition Policy (Web Page)

<http://ncp.ncc.gov.au/pages/about>

|

|

NSW Department of Industry, Annual Report on the Administration of

Agricultural Statutory Authorities (30 June 2019)

|

|

NSW Department of Primary Industries (DPI), Marketing of Primary

Products Act 1983 – NSW Rice Marketing Board Review Report (April

2005), 40-1 (‘Rice Vesting Review 2005’).

|

|

NSW Department of Primary Industries (DPI), Review of Rice Vesting

Proclamation (December 2016) (‘Rice Vesting Review

2016’).

|

|

NSW Department of Primary Industries (DPI), Rice Vesting Review 2021

(April 2021) (‘Rice Vesting Review 2021’).

|

|

NSW Department of Primary Industries (DPI), Terms of Reference:

Independent Report on the findings of the NSW Rice Vesting Review

2021.

|

|

NSW Trade and Investment Strategic Policy & Economics Division,

Review of Rice Vesting by the Rice Marketing Board under the NSW Rice

Marketing Act 1983 (October 2012) 7 (‘Rice Vesting Review

2012’).

|

|

O’Keefe, Patrick and Melissa Naeve, ‘Experiences of wheat

growers in Australia’s western Wimmera following deregulation

of the

export wheat market’ (2017) 26(1) Rural Society 1

|

|

O’Keefe, Patrick and Naeve, Melissa, ‘Experiences of Wheat

Growers in Australia’s Western Wimmera Following Deregulation

of the

Export Wheat Market’ (2017) 26(1) Rural Society 1, 10-13 DOI:

10.1080/10371656.2017.1283736

|

|

O’Keefe, Patrick, ‘Creating a Governable Reality: Analysing the

Use of Quantification in Shaping Australian Wheat

Marketing Policy’

(2018) 35 Agriculture and Human Values 553 DOI:

10.1007/s10460-018-9848-6

|

|

Productivity Commission, Regulation of Australian Agriculture

(Report to the Australian Government No 79, 15 November 2016)

|

|

Ricegrowers’ Association of Australian Inc., Submission to the

Productivity Commission’s Inquiry into the Regulation of Agriculture,

August 2016

|

|

Ricegrowers' Association of Australia Inc., Submission to the Review of

the Rice Vesting Proclamation, August 2021

|

|

Rice Marketing Board Annual Report 2017

<https://www.rmbnsw.org.au/annual-reports>

|

|

Rice Marketing Board Annual Report 2018

<https://www.rmbnsw.org.au/annual-reports>

|

|

Rice Marketing Board Annual Report 2019

<https://www.rmbnsw.org.au/annual-reports>

|

|

Rice Marketing Board Annual Report 2020

<https://www.rmbnsw.org.au/annual-reports>

|

|

Rice Marketing Board Annual Report 2021

<https://www.rmbnsw.org.au/annual-reports>

|

|

Sunrice (undated), Detailed Historic Timeline of the Australian Rice

Industry

|

|

Thompson, Lyndal et al, A Report on the Impacts of the Sugar Industry

Reform Program

(SIRP): 2004 to 2008 (ABARES report for the Australian Government,

November 2010).

|

|

USDA Economic Research Service, ‘Global Rice Production and

Trade’, Rice Sector at a Glance (Web Page, updated 20 December

2022)

<https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/crops/rice/rice-sector-at-a-glance/#Global>

|

|

Vanclay, Frank, ‘The Impacts of Deregulation and Agricultural

Restructuring for Rural Australia’ (2003) 38(1) Australian Journal

of Social Issues 81 DOI: 10.1002/j.1839-4655.2003.tb01137.x

|

|

Watson, Alistair, ‘Grain Marketing Policy and National Competition

Policy: Reform or Reaction?’ (1999) 43(4) Australian Journal of

Agricultural and Resource Economics 429, 430 DOI:

10.1111/1467-8489.00089

|

Barley Marketing Board (NSW) v Norman [1990] HCA 50; (1990) 171 CLR 182

Castlemaine Tooheys Ltd v South Australia (1990) 169 CLR 436

Cole v Whitfield [1988] HCA 18; (1988) 165 CLR 360

James v Cowan [1932] LR AC 542

|

Australian Constitution

|

|

Marketing of Primary Products Act 1928 (NSW) (repealed)

|

|

Marketing of Primary Products Act 1983 (NSW) (renamed Rice

Marketing Act 1983 on 6 July 2004)

|

|

Rice Marketing Act 1983 (NSW)

|

|

Rice Marketing Amendment (Prevention of National Competition Penalties)

Act 2005 (NSW).

|

|

Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth)

|

|

Competition Principles Agreement (Council of Australian Governments,

11 April 1995)

|

|

Government of Western Australia, ‘Potato Industry Moves to

Deregulation’ (Media Statement, 15 April 2015)

<https://www.mediastatements.wa.gov.au/Pages/Barnett/2016/04/Potato-industry-moves-to-deregulation.aspx>

|

|

NSW Deputy Premier and Minister For Agriculture and Western NSW ‘Rice

vesting arrangements extended across NSW’ (Joint

Media Release, 20 April

2022)

<https://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/about-us/media-centre/releases/2022/ministerial/rice-vesting-arrangements-extended-across-nsw>

|

|

NSW, Parliamentary Debates, Legislative Assembly, 18 November 2002,

18770 (Peter Black)

|

|

NSW, Parliamentary Debates, Legislative Assembly, 9 November 2005,

19319 (Sandra Nori)

|

[2] Corresponding author: andrew.lawson@une.edu.au

[3] This article is based on an LLB Honours thesis submitted by the first author in October 2022.

[4] USDA Economic Research Service, ‘Global Rice Production and Trade’, Rice Sector at a Glance (Web Page, updated 20 December 2022) <https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/crops/rice/rice-sector-at-a-glance/#Global>

[5] James Fell et al, ‘Australian Rice Markets in 2020’, ABARES, 10(2) Agricultural Commodities, June quarter 2020 <https://www.agriculture.gov.au/abares/research-topics/agricultural-outlook/rice>

[6] Australian Department of Agriculture, Forestry & Fisheries, Rice (Web page, updated 4 November 2019) <https://www.agriculture.gov.au/agriculture-land/farm-food-drought/crops/rice>

[7] Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), Agricultural Commodities, Australia 2021-22 (Catalogue No. AGCDCNAT_STATE202122, 17 January 2023).

[9] Aither Pty Ltd, Expanding the NSW Rice Industry: Independent Review of the Viability of Developing the Rice Industry Outside the Murray and Riverina Regions (Final Report for the Rice Marketing Board NSW, 31 May 2018) 12; Marketing of Primary Products Act 1928 (NSW); Rice Marketing Act 1983 (NSW).

[10] Industry Commission, Statutory Marketing Arrangements for Primary Products (Report No. 10 to the Australian Government, 26 March 1991) 13.

[11] Industry Assistance Commission, Parliament of Australia, The Rice Industry (Parliamentary Paper No. 385, 23 October 1987).

[12] Ricegrowers' Association of Australia Inc., Submission to the Review of the Rice Vesting Proclamation, August 2021, 6; Ricegrowers’ Association of Australian Inc., Submission to the Productivity Commission’s Inquiry into the Regulation of Agriculture, August 2016.

[13] Rice Marketing Act 1983 (NSW) (‘RMA’)

[14] Ann Majchrzak and M Lynne Markus, ‘Obtain New Evidence’ in Ann Majchrzak and M Lynne Markus (eds), Methods for Policy Research: Taking Socially Responsible Action (SAGE online version, 2014) DOI: 10.4135/9781506374703.

[15] University of New England Human Research Ethics Committee Approval No. HE22-008.

[16] Venton Cook, Rural Market Regulation and Legislation in South Australia (Research Paper, South Australian History of Agriculture Group, September 2021) 12.

[17] Productivity Commission, Regulation of Australian Agriculture (Report to the Australian Government No 79, 15 November 2016) 613.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid 615.

[20] Ibid 613.

[22] [1988] HCA 18; (1988) 165 CLR 360.

[23] Ibid 398.

[24] [1990] HCA 50; (1990) 171 CLR 182.

[25] Ibid 202.

[26] Ibid 204.

[27] Anthony Gray, ‘Compulsory Marketing Schemes and Section 92 of the Australian Constitution’ [2014] UTasLawRw 17; (2014) 33(2) University of Tasmania Law Review 317, 334.

[28] Ibid 331.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid 332.

[31] Castlemaine Tooheys Ltd v South Australia (1990) 169 CLR 436, 472.

[32] Regulation of Australian Agriculture (n 13) 617.

[33] Jack Lewis, ‘Organized Marketing of Agricultural Products in Australia’ (Address, Conference of Australian Agricultural Economics Society, 15-17 February 1961).

[34] Ibid 1.

[36] Malcolm Abbott and David Merrett, ‘Counting the Cost: The Reserve Price Scheme for Wool 1970-2001’, (2019) 63 Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, 790-813 DOI: 10.1111/1467-8489.12337.

[37] Fred Moylan, U-Turn for Wool: A Radical Solution to the Problems of the Wool Industry (New Street Books, 1991) 99.

[38] Charles Massy, Breaking the Sheep’s Back: The Political Destruction of the Australian Wool Industry (University of Queensland Press, 2011)

[39] Rosemary Lyster, ‘(De)regulating the Rural Environment’ (2002) 19(1) Environmental and Planning Law Journal 34, 35.

[40] Fred Hilmer, National Competition Policy (Independent Commission of Inquiry into National Competition Policy Report to COAG, 25 August 1993).

[41] Ibid 36.

[42] National Competition Council, ‘About the National Competition Policy’, National Competition Policy (Web Page) <http://ncp.ncc.gov.au/pages/about>

[43] The Rice Industry (n 8); Statutory Marketing Arrangements for Primary Products (n 7); Regulation of Australian Agriculture (n 14).

[44] NSW Department of Industry, Annual Report on the Administration of Agricultural Statutory Authorities (30 June 2019) 3.

[45] Ibid.

[46] Alistair Watson, ‘Grain Marketing Policy and National Competition Policy: Reform or Reaction?’ (1999) 43(4) Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics 429, 430 DOI: 10.1111/1467-8489.00089.

[47] Ibid 441.

[48] NSW Deputy Premier and Minister For Agriculture and Western NSW ‘Rice vesting arrangements extended across NSW’ (Joint Media Release, 20 April 2022) <https://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/about-us/media-centre/releases/2022/ministerial/rice-vesting-arrangements-extended-across-nsw>

[49] Warren Males, ‘A Case for Statutory Marketing Arrangements’ (Annual Conference of the Australian Agricultural Economics Society, 10-12 February 1992) 7.

[51] Ted Kolsen, ‘Microeconomic Reform and National Competition Policy: Misconceptions and Problems’ (1996) 55(2) Australian Journal of Public Administration 83, 84 DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-8500.1996.tb01205.x.

[52] Mick Keogh ‘Australian agribusiness law: sensible regulation, or red tape gone mad?’ (Address, Third Annual Australian Agribusiness Law Conference, 17 May 2018) 1.

[54] Ibid 46, 50.

[55] RWM Johnson, WR Schroder and NW Taylor, ‘Deregulation and the New Zealand Agricultural Sector: A Review’ (1989) 57 Review of Marketing and Agricultural Economics 47, 58 DOI: 10.22004/ag.econ.12445.

[56] Ibid 59, 68.

[57] NSW Department of Primary Industries, Rice Vesting Review 2021 (April 2021) 136 (‘Rice Vesting Review 2021’).

[58] Ibid.

[59] Government of Western Australia, ‘Potato Industry Moves to Deregulation’ (Media Statement, 15 April 2015) <https://www.mediastatements.wa.gov.au/Pages/Barnett/2016/04/Potato-industry-moves-to- deregulation.aspx>

[60] Lyndal Thompson et al, A Report on the Impacts of the Sugar Industry Reform Program

(SIRP): 2004 to 2008 (ABARES report for the Australian Government, November 2010).

[61] Australian Department of Agriculture, Water & the Environment, Post Implementation Review- Competition and Consumer (Industry Code – Sugar) Regulation 2017 (Sugar Code of Conduct) (10 December 2021) 1-2.

[63] Frank Vanclay, ‘The Impacts of Deregulation and Agricultural Restructuring for Rural Australia’ (2003) 38(1) Australian Journal of Social Issues 81, 87 DOI: 10.1002/j.1839-4655.2003.tb01137.x.

[64] Ibid 83.

[65] Patrick O’Keefe and Melissa Naeve, ‘Experiences of Wheat Growers in Australia’s Western Wimmera Following Deregulation of the Export Wheat Market’ (2017) 26(1) Rural Society 1, 10-13 DOI: 10.1080/10371656.2017.1283736.

[66] Patrick O’Keefe, ‘Creating a Governable Reality: Analysing the Use of Quantification in Shaping Australian Wheat Marketing Policy’ (2018) 35 Agriculture and Human Values 553 DOI: 10.1007/s10460-018-9848-6.

[67] Geoff Buggle, ‘Is there a case for State Statutory marketing Arrangements?’ (Conference Paper, Annual Conference of the Australian Agricultural Economics Society, 9-11 February 1993) 1.

[68] Ibid 2.

[69] Ibid 3.

[70] Rice Marketing Act 1983 (NSW) (RMA) s 56.

[73] Industry Assistance Commission (n 8) xi.

[74] Ibid 97.

[75] Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth).

[76] Marketing of Primary Products Act 1983 (NSW).

[77] Kealey, Lucy, M R C Hedditch and Warwick Clampett, ‘History of rice growing in Australia’ in L M Kealey and W S Clampett (eds), Production of Quality Rice in South Eastern Australia (Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation, 2000); Sunrice (undated), Detailed Historic Timeline of the Australian Rice Industry.

[78] NSW, Parliamentary Debates, Legislative Assembly, 18 November 2002, 18770 (Peter Black).

[79] Competition Principles Agreement (1995) cl 5 (1).

[80] Ibid cl 5(5).

[81] Ibid cl 5(6).

[82] RMA Part 7; Subordinate Legislation Act 1989 (NSW) s 10(2).

[83] Rice Marketing Amendment (Prevention of National Competition Penalties) Act 2005 (NSW).

[84] NSW, Parliamentary Debates, Legislative Assembly, 9 November 2005, 19319 (Sandra Nori).

[85] NSW Department of Primary Industries, Review of Rice Vesting Proclamation (December 2016) (‘Rice Vesting Review 2016’).

[86] Ibid.

[87] IMC, Review of the NSW Rice Marketing Act 1983 (Report for the NSW Department of Primary Industries, October 2010), 4 (‘Rice Vesting Review 2010’).

[88] Ibid 3, 20.

[89] Rice Marketing Board Annual Report 2019, 4.

[90] Rice Marketing Board Annual Report 2021, 4.

[91] Rice Vesting Review 2021 (n 52) 67-68.

[92] Interviewee 1.

[93] Ibid.

[95] Rice Vesting Review 2021 (n 52) 120.

[96] Ibid.

[97] Submission to the Review of the Rice Vesting Proclamation 2021 (n 9); Submission to the Productivity Commission’s Inquiry into the Regulation of Agriculture 2016 (n 9).

[98] Ibid 4.

[99] Ibid.

[100] NSW Department of Primary Industries, Marketing of Primary Products Act 1983 – NSW Rice Marketing Board Review Report (April 2005), 40-1 (‘Rice Vesting Review 2005’).

[101] Ibid 47.

[102] Ibid.

[103] Rice Vesting Review 2021 (n 52).

[104] Ibid.

[105] NSW Department of Primary Industries, Terms of Reference: Independent Report on the findings of the NSW Rice Vesting Review 2021.

[106] Rice Vesting Review 2021 (n 52) 44.

[107] Rice Vesting Review 2010 (n 81).

[108] Rice Vesting Review 2021 (n 52) 24.

[109] Ibid.

[110] Interviewee 2.

[111] NSW Trade and Investment Strategic Policy & Economics Division, Review of Rice Vesting by the Rice Marketing Board under the NSW Rice Marketing Act 1983 (October 2012) 7 (‘Rice Vesting Review 2012’).

[112] Ibid 12.

[113] Ibid 9.

[114] Rice Vesting Review 2021 (n 52), 44.

[115] Ibid 52.

[116] Ibid 64.

[117] Garry Griffith and John Mullen, ‘Pricing-to-market in NSW rice export markets’ (2001) 45(3) Australian

Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics 323, 331, DOI: 10.1111/1467-8489.00146.

[118] Ibid 332.

[119] Ibid 333.

[120] Interviewee 1.

[122] Ibid 34-36.

[123] Ibid 36.

[124] Interviewee 1.

[125] Aither Pty Ltd (n 6) 27.

[126] Interviewee 1.

[127] Statutory Marketing Arrangements for Primary Products (n 7) 67.

[128] BITRE, Freightline 6 – Australian Rice Freight Transport (Australian Government, 2018).

[129] Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), ‘Cereal and other Broadacre Crops: Cotton and Rice Production, 2015-16 to 2020-21’, Agricultural Commodities, Australia 2020-21 (Web Page, 26 July 2022) <https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/industry/agriculture/agricultural-commodities-australia/2020-21#cereal-and-other-broadacre-crops>

[130] Rice Vesting Review 2012 (n 40) 12.

[131] Ibid.

[132] NSW Department of Primary Industries, Review of Rice Vesting Proclamation (December 2016) (‘Rice

Vesting Review 2016’).

[133] Ibid 7.

[134] Rice Vesting Review 2021 (n 5) 19.

[135] Ibid 43.

[136] Ibid.

[137] Ibid.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/IntJlRRuralRLawP/2023/1.html