Alternative Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Alternative Law Journal |

|

Jason L. Pierce[*]

Legal scholars have conceptualised appellate litigation in a variety of ways. One common distinction is between public and private litigation models. The private litigation model understands appellate litigation first and foremost as a legal enterprise that resolves specific disputes between the immediate parties. Those parties bring their conflicts before courts, where judges function as passive umpires and tailor their decisions to the particular disputes.[1] The public model conceives litigation in broader terms. Litigation still resolves specific disputes, but it has additional effects, including social control, law making (in the sense that some legal rules are judge created),[2] promulgation and enforcement of public norms,[3] and providing a venue for interest groups to pursue policy goals.[4]

This article advances the thesis that over the last 20 years the High Court has moved from a historically (and staunchly) private model to a more public model of appellate litigation. This transition has evidenced itself in a variety of ways. The focus in this article is on non-party intervention in High Court litigation. In short, the heightened frequency of non-party, specifically non-governmental, intervention points to a High Court increasingly cognisant of its legal and political powers. As the High Court has opened its proceedings increasingly to non-party, non-governmental participants, senior appellate judges remain hesitant about the merits of this development. This article is divided into two sections. The first presents statistical data confirming the High Court's shift from a private toward a public model, demonstrated here in non-party participation in its litigation. The second draws on interviews with Australian senior appellate judges to illustrate their unease about this shift.

Under the public model, appellate litigation is understood as both a legal and political enterprise. It is a legal enterprise in that judges resolve the specific disputes that come before them. It is a political enterprise in that resolution of these disputes may have profound political, economic, and social consequences. Appellate litigation is also a political enterprise because determining what the law is or should be is itself contested. Political actors advance their interests through courts as often as legislatures or executive bureaucracies. Given the contested nature of law and the recognition that judicial decisions impact interests beyond the immediate parties, the public litigation model encourages judges to consult sources and solicit information from non-party participants. The frequency with which non-parties participate in appellate litigation provides an indicator -though not exclusive-for the Court's fidelity to the public model. By 'non-party' I mean those who may participate in litigation by a court granting leave to appear as either formal interveners (who become official parties to proceedings and may adduce evidence, offer witnesses, cross-examine, etc) or as amici curiae ('friends of the court' who offer advice on points of law but are not formal parties).

For much of the 20th century, the High Court of Australia maintained a jaundiced view of non-party intervention, viewing amici curiae and interveners as unnecessary distractions. The Court's official rules provide no guidelines for incorporating non-governmental interveners or criteria for evaluating such requests. In fact, non-governmental parties seeking to intervene must avail themselves of the catchall Order 51 in the High Court Rules, which enables motions to be put before the Court for which 'no other procedure is provided'. With no formal rules governing intervention, dicta from Sir Owen Dixon in a 1930 judgment became the Court's benchmark approach. In Railways Union v Victorian Railways Commissioners [1930] HCA 52; (1930) 44 CLR 319 at 331 he admonished:

I think we should be careful to allow arguments only in support of some right, authority or other legal title set up by the party intervening. Normally parties, and parties alone, appear in litigation ... The discretion to permit appearances by counsel is a very wide one; but I think we would be wise to exercise it by allowing only those to be heard who wish to maintain some particular right, power or immunity in which they are concerned, and not merely to intervene to contend for what they consider to be a desirable state of the general law.

Dixon's cautious approach loomed large for much of the 20th century and still guides many appellate judges today.

Amendments in 1976 to the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) heightened the opportunity for governmental intervention in High Court litigation. Section 78A created an automatic, non-discretionary right of intervention to the Commonwealth and state Attorneys General in cases that raise constitutional issues. The Attorneys General regularly exercise this power, whereby they become formal parties to the proceedings. No similar right of intervention exists for Attorneys General in non-constitutional matters.[5]

In private or common law appeals that raise no constitutional questions, the Court retains the same discretion over governmental requests to intervene as a private individual or organisation.[6] Leave must be secured and the Court tends to abide by Dixon's dicta. Thus, while the Court has been more tolerant of state and Commonwealth participation in constitutional questions, it has granted a paltry number of discretionary interventions; that is, interventions not requested under s.78A.[7] One study reports that until the 1980s discretionary intervention (either as interveners or amici curiae) was nearly nonexistent. Since the 1980s, the High Court has granted discretionary intervention in only 31 cases.[8]

The High Court exhibited an anaemic record for non-party intervention during most of the last century, particularly compared to the US and Canadian Supreme Courts. It allowed, for example, amici curiae participation in a scant 15 cases from 1947-1997.[9] Only three of these cases involved non-governmental interest groups, organisations, or individuals; the Commonwealth or state solicitors general were amici in the remaining twelve cases. This contrasts sharply with the US Supreme Court, which allowed amici participation in 3389 cases over the same period.[10] The Canadian Supreme Court has a practice of non-party intervention that falls somewhere between the Australian and American cases. Scholars have noted that since passage of the 1982 Charter of Rights and Freedoms, intervener and amici participation has been more widespread in Canada.[11]

Over the last 20 years, however, the Court took significant, albeit slow and inconsistent, steps toward the public model's acceptance of non-party intervention. Data gathered from published High Court judgments from 1947 to 2001 indicate that non-party intervention (both formal interveners and amici curiae) in High Court litigation has steadily increased.[12] For example, the High Court averaged only four cases each year during the I950s that involved non-party participants. This compares to I3.I6 cases a year in the I990s.[13] Disaggregating these figures from decade to year shows a steady increase across the intervening years. In addition to more High Court cases having some form of non-party intervention, the raw number of interveners involved in that litigation also grew. From I947 to I977, 219 interveners participated in High Court litigation, an average of 6.5 interveners a year. Three times as many interveners participated from I978 to 2001, an average of 31.9 a year. The aggregate picture - more cases involving non-party intervention and more interveners -is that the Court has opened itself in the last 20 years to arguments beyond what the litigants offered.

These data suggest movement toward the public model and confirm important changes in the composition and nature of High Court litigation. No doubt the I976 amendments to the Judiciary Act are partly responsible.[14]

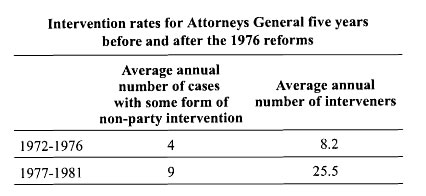

Guaranteeing Attorneys General the right to participate in constitutional litigation contributed substantially to these up-ticks. If one compares non-party intervention rates five years before and after the reform, the Court's litigation looks profoundly different.

Indeed Attorneys General have intervened far more frequently than private individuals or groups since I945. For 45 of the 55 years included in this data set, Attorneys General constituted at least 80% of all interveners for that year.

Indeed, in only three years since I970 have private interveners accounted for more than 20% of all interveners in a given year (1973: 33%; I975: 23%; I997: 22%). [15]

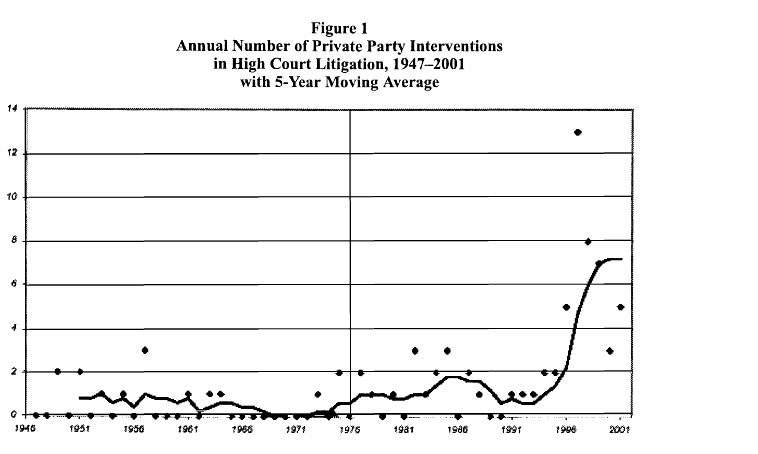

The fact that Attorneys General accounted for a significant portion of non-party interventions provides some evidence of a shift toward the public model, in that non-party (governmental) perspectives were increasingly infused in High Court litigation. This infusion occurred, however, not necessarily because the Court wanted or asked for it. At one level, the court was simply discharging its statutory duty. A far more convincing case for a shift to the public model could be made if data showed the Court allowing more private intervention under its discretionary powers. In such circumstances, the Court is motivated not by duty, but foresees private interveners improving the litigation process and its decision making.[16] Private intervention would occur because the Court presumably wants it. In fact, data gathered on the annual number of private interventions show just such a shift (see Figure 1)

Private interventions, allowed under the Court's discretionary powers, have increased particularly since the mid-1980s. These data further evidence the Court's increasing adherence to a public litigation model. A court that adheres to the public model welcomes these interventions because it recognises the broader social, economic, legal, and political consequences of its decisions and the valuable role that non-party, private interveners can play in exploring those consequences.

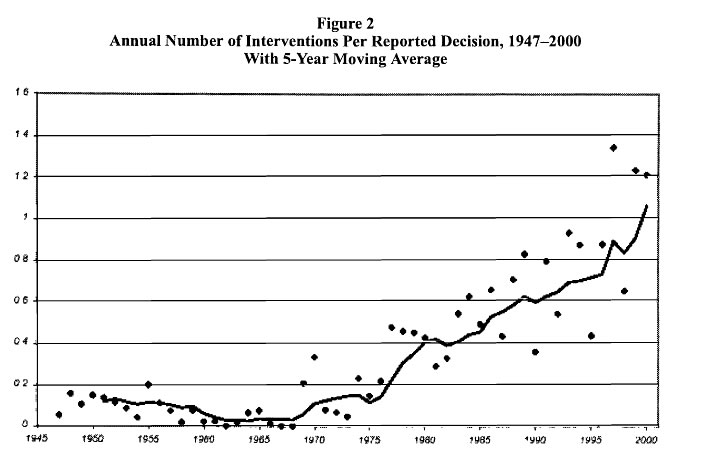

Finally, the growth in governmental and private interventions cannot be explained away as a by-product of an ever-growing docket. Figure 2 weights the annual intervention rates by workload, calculated by dividing the annual interventions by the annual number of reported decisions.

The trend could not be clearer. More interventions occurred in the last 20 years even when adjusted for annual workload differences. This trend raises red flags, however, for many of Australia's senior appellate judges. This next section explores this concern.

A wariness about the High Court favouring a public litigation model became quite pronounced during in-depth, anonymous interviews that I conducted in recent years with roughly 60% of Australia's appellate bench. The merit of non-party intervention in High Court litigation was one of many issues addressed in the interviews. Based on the interview data-a sample of which follows-High Court justices should not expect much support from intermediate appellate judges.[17]

Reservations about the public model frequently emerged when informants discussed the purpose of appellate litigation. Many judges offered the private model's litigant-centred approach.[18] For example, one Federal Court judge spoke about litigants 'owning' litigation, meaning that courts should answer only 'what the law is' for particular disputes [127]. A South Australia Supreme Court judge echoed this litigant-centred notion of courts:

[T]he legal system should never be used as an instrument for social or political change. That would be a misuse of the legal system and likely to lead to anarchy. I think judges have to keep constantly in mind that they're there to decide the cases. You're only deciding a particular case ... I don't think we're there to change social attitudes except in making people more law abiding. We don't have an evangelical role in the community. [emphasis added] [18:1945]

It should not be surprising that informants offered a litigant-centred perspective when describing what should take place in courts of first instance and perhaps intermediate appellate courts, though to a lesser extent. That many informants had this same view of High Court litigation is striking. Reflecting on the High Court's approach to litigation, a Federal Court judge concluded:

If a case is a test case-both sides are saying, 'We want to go forward and the law doesn't definitively address this problem,' then the judge has a mandate from the parties to say, 'I can be a bit adventurous. I can tell you where I think the law will direct itself.' Mabo was a test case, so it was perfectly legitimate for Brennan to do what he did. The problem is that if you don't get a mandate from the parties, I don't think you can do it. It's their litigation and they're entitled to do with it what they want ... It's not as if a judge is considered a law reform commission. No judge can go in depth into policy making behind legislation. The best a judge can do is look at the common law or statute, hear the arguments of the parties, and within the contests set up by the parties, take the law forward if asked by the parties. I have real problems with judges who take the law forward when the parties say, 'We don't want that. We want to know what the law is now.' [emphasis added] [127: 1200]

Even informants who might endorse greater non-party intervention in High Court litigation were not without reservations. One judge remarked:

With the High Court playing this role of making general observations ... there's a big argument for saying that if they're dealing with a case out of Tasmania . . . that may have a significant impact on Western Australia and Western Australia should be heard. Some of the judges, particularly Kirby, will ask and require counsel to say what the position is in other states. He, of all of them, is the most explicitly aware of the general nature of his judgments and goes some way to accommodate different submissions. It is, I think, a problem for the High Court when it moves into this area. When its more generalist, there is a corresponding obligation to open up the categories of people who may have an interest in the matter. If you're going to lay down general rules with general application ... then you need to hear from them, as indeed the Supreme Court in the U.S. The consequence, of course, is that they're overrun with paper [emphasis added] [126:1045]

Another informant cautioned:

[O]nce you recognise ... a place for amicus briefs, it becomes very difficult to define the limits ... [O]nce you recognise the appropriateness of it, you have to have it in the American sense, provided that people have something to say. [58:3315]

Although non-party intervention has increased in recent years, several informants criticised the Court for its inconsistency in allowing some interventions and not others. Several pointed to Dietrich v The Queen [1992] HCA 57; (1992) 177 CLR 292 for illustration. In Dietrich, the question was whether the common law recognised a right of accused indigents to legal representation at public expense. The trial court had failed to stay a proceeding in which Dietrich, through no personal fault, was unable to obtain legal representation. The Court concluded, inter alia, that while there is no common law right to counsel at public expense, an accused has a right to a fair trial. If having no legal representation fosters an 'unfair trial,' then the proceeding must be stayed until counsel is provided.

This decision was obviously significant on legal grounds, but it raised equally weighty economic questions for legal aid organisations and parliaments that fund them. Several informants objected to the fact that the Court decided Dietrich without non-party participants. The potentially profound economic consequences of the case demanded a public model approach.

Judge: The effect of Dietrich was that legal aid began to be almost totally confined to criminal cases ... The greatest proportion of criminal cases involves crimes committed by men, and a goodly proportion of those involve crimes committed against women by way of domestic violence and sexual assault. These women needed to be able to bring domestic violence proceedings ... or proceedings for child support or divorce and legal aid became virtually unavailable. It was provided to the defendants because the High Court would say, 'Well applying Dietrich, this person is entitled to legal representation and his prosecution ought to be stayed until he's afforded it.' The legal aid offices reacted to this by channelling funds in that direction. So, the High Court in an effort to protect one section of society severely affected the rights of another section of society. I wonder to this day whether any members of the High Court even thought about that. Q: I'm sure a woman's advocacy group would have advanced this argument if afforded an opportunity [to appear as amicus curiae]. Judge: That's exactly right. Whether the result would have been different is another matter. It may have made a difference to the structure of the judgment or to whether this was a matter that needed to be addressed by Government ... My concern is that [judges] don't always have the information. [58:3815]

Another judge remarked:

Dietrich was a decision that had profound consequences on governments and ... funding because governments allocate an amount of money for legal aid ... The point is that the High Court decided the case where the states weren't represented and without any opportunity, as would happen in the [U.S.] Supreme Court, for amicus briefs so that the consequences ofthe decision would be known. There have been significant financial consequences which have had a significant impact on taxpayers. That decision was made without any supporting material as to the effect of that impact ... The High Court is reticent because of the practical difficulties. [21: I 045]

This is not the place to speculate as to why these reservations exist. One possibility that demands closer study is that discretionary intervention is nearly absent from intermediate appellate court litigation. By way of example, a South Australian judge commented:

Amicus briefs are rarely used here. There has to be a real reason to need an amicus curiae. It might be a circumstance that the two parties were unable to put the argument as well as it ought to be put, and a third person is necessary to put it. The way we understand amicus in this court is a true amicus curiae-not a person there to represent either party, but a person who's there to put the argument for the purpose of assisting the court ... You wouldn't see an amicus here often at all, except in circumstances where it is thought necessary. Q: Have you had amicus participation in any cases you've handled?

Can't recall one. [117: 3515]

Another reason could be that informants are genuinely concerned about the Court's capacity to handle broad political or social issues. 'Judges have to be a bit careful to remind themselves that they work in a micro world. They do single cases. It's not always possible for them to understand the ... ramifications of their decisions. It would be quite wrong for them to tailor decisions-either expansively or in a retracting sense -when the full picture is not before them', said one New South Wales appellate judge. Yet at the same time the judge admitted that, 'It worries me greatly that we make judgments on social issues without social information. It's a real issue of how we can keep ourselves abreast, especially in a polyglot and polymorphous society. It really worries me that we keep ourselves up to date. I think the only true way to keep ourselves up to date is in that sense.' [58:2830]

A significant transition occurred at the High Court in the last two decades of the 20th century. Departing from a long ensconced private litigation model, the Court brought greater numbers of governmental interveners, private interveners, and amici curiae participants into its litigation. One aim of this article was to present quantitative data that confirm this shift. These data raise a number of questions that demand attention in future research. First and foremost, what have contemporary High Court justices thought about this shift? Were they cognisant of these trends? Was there a conscious effort on the part of some High Court justices to invite more interveners? In other words, did the Court create a favourable environment or did the private and governmental interveners? What are the consequences to the Court as a political institution if it sustains this shift toward the public model?

A second aim of this article was to document, in a cursory manner, the unease and uncertainty among many senior judges about these trends. Although the preceding interview data are only illustrative examples, they capture the general attitude of many judges toward their High Court. The interview data suggest a gap between how intermediate appellate judges and High Court justices conceptualise appellate litigation. A key issue that deserves attention in later research is whether this gap is consequential. In other words, does the High Court expose itself to legitimacy questions if it continues on a public model trajectory? Are there any signs that the public model may be securing footholds in Australia's intermediate appellate courts? These questions will remain at the fore as the Court enters its second century of decision making.

[*] Jason L. Pierce is Assistant Professor University of Dayton, Department of Political Science.

email: Jason.Pierce@notes.udayton.edu

© 2003 Jason Pierce (text)

© 2003 John Lynch (cartoon)

[1] Fuller, Lon, 'Forms and Limits of Adjudication', (1978) 92 Harvard Law Review 353--409; although sec Bone, R.G., 'Lon Fuller's theory of adjudication and the false dichotomy between dispute resolution and public law models of litigation,' (1995) 75(5) Boston University Law Review 1273-1324, who questions distinctions between public and private litigation models.

[2] Shapiro, Martin M., Courts: A Comparative and Political Analysis, University of Chicago Press, 1981.

[3] Chayes, Abram, 'The Role of the Judge in Public Law Litigation', (1976) 89 Harvard Law Review 1281–4; Fiss, Owen M., 'Foreword: The Forms of Justice', (1979) 93 Harvard Law Review 39--44; Fiss, Owen M., 'The Social and Political Foundations of Adjudication', (I982) 6 Law and Human Behavior 121.

[4] Lawrence, Susan E., The Poor m Court: The Legal Services Program and Supreme Court Decision Making, Princeton University Press, 1990; Olson, Susan M., 'Interest-Group Litigation in Federal District Court: Beyond the Political Disadvantage Theory', (1990) 52(3) The Journal of Politics 854-82.

[5] Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth), s.78B.

[6] Sec Corporate Affairs Commission v Bradley [1974] 1 NSWLR 391.

[7] Campbell, Enid, 'Intervention in Constitutional Cases', (1998) 9 Public Law Review 225.

[8] Williams, George, 'The Amicus Curiae and Intervener in the High Court of Australia: A Comparative Analysis', (2000) 28 Federal Law Review 365--402.

[9] Main v Main (1949) 78 CLR636; Blundellv Musgrave [1956] HCA 66; (1956) 96 CLR 73; Armstrong v The State Of Victoria (No 2) [1957] HCA 55; (1957) 99 CLR 28; Russell v Walters [1957] HCA 21; (1957) 96 CLR 177; Lamshed v Lake [1958] HCA 14; (1958) 99 CLR 132; James v Robinson [1963] HCA 32; (1963) 109 CLR 593; The Queen v Public Vehicles Licensing Appeal Tribunal (Tas.); Ex Parte Australian National Airways Pty Ltd [1964] HCA 15; (1964) 113 CLR 207; The Queen v Cook; Ex Parte Twigg [1980] HCA 36; (1980) 147 CLR 15; Victoria v Australian Building Construction Employees' And Labourers' Federation (No 2) (I982) [1982] HCA 57; 152 CLR 179; The Commonwealth of Australia v Tasmania. (the Tasmanian Dam Case) (1983) 158 CLR I; Wentworth v New South Wales Bar Association [1992] HCA 24; (1992) 176 CLR 239; Matter No M38 of 1995 David Grant And Co Pty Limited (Receiver Appointed) v Westpac Banking Corporation FC 95/039 (I995) [1995] HCA 43; 184 CLR 265; David Russell Lange v Australian Broadcasting Corporation (I997) [1997] HCA 25; 189 CLR 520; Laurence Nathan Levy v The State Of Victoria & Ors [1997] HCA 31; (1997) 146 ALR 248; Project Blue Sky Inc & Ors v Australian Broadcasting Authority [1998] HCA 28; (1998) 153 ALR 490.

[10] Kearney, Joseph D. and Merrill, Thomas W., 'The Influence of Amicus Curiae Briefs on the Supreme Court', (2000) 148 University of Pennsylvania Law Review 743-855.

[11] Epp, Charles R., The Rights Revolution: Lawyers, Activists and Supreme Courts in Comparative Perspective, University of Chicago Press, 1998; Williams, George, 'The Amicus Curiae and Intervener in the High Court of Australia: A Comparative Analysis', (2000) 28 Federal Law Review 365--402; Brodie, Ian, Friends of the Court: The Privileging of Interest Group Litigants in Canada, State University of New York Press, 2002.

[12] The words 'intervener' and 'intervention' are used in this section generically for both formal interveners and amici participants, unless specified otherwise. These data were assembled from full-text searches of all published High Court judgments available through Lexis-Nexis for the years 1945-200 l. Data from earlier years were unavailable from Lexis-Nexis. The Scaleplus database was used for the years 1998-2001, for which Lexis-Nexis provides an incomplete set of High Court judgments.

[13] The mean number of annual High Court cases with non-party intervention by decade arc as follows: 1940s: 1.8; 1950s: 4.2; 1960s: 1.3; 1970s: 6.0; 1980s: 12.2; 1990s: 13.16.

[14] Above, ref. 5.

[15] Included within this 'private interveners' label arc private organisations, individuals, and some governmental organisations, such as the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission. I categorise these governmental organisations as 'private interveners' because they do not possess the same intervention rights as Attorneys General.

[16] US Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O'Connor illustrated this point m Webster v Reproductive Health Services [1989] USSC 149; 492 US 490 at 522 (1989):

'The willingness of courts to listen to interveners is a reflection of the value that judges attach to people. Our commitment to a right to a hearing ... is derived not only from the belief that we improve the accuracy of decisions when we allow people to present their side of the story, but also from our sense that participation is necessary to preserve human dignity and self-respect'.

[17] A total of 82 interviews were conducted between 1997 and 2001. For further information, sec Pierce, Jason, 'Interviewing Australia's Senior Judiciary,' (2002) 37(1) Australian Journal of Political Science 131--42.

[18] Space limitations prohibit me from thoroughly presenting and assessing interview data on this point. Rather, I endeavour in this section to present a representative sample of opinion from Federal Court and state Supreme Court judges. The numbers following quotations refer to a particular informant and segment in the interview.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/AltLawJl/2003/14.html