Journal of Australian Taxation

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Journal of Australian Taxation |

|

TAXATION ISSUES IN A WORLD OF ELECTRONIC COMMERCE

By Dale Pinto

The Australian Commissioner of Taxation, Mr Michael Carmody, recently stated that:

Tax administrators face greater difficulties in enforcing tax laws and maintaining their community's legitimate revenue base when dealing with international rather than domestic transactions, particularly when dealing with a jurisdiction that combines tax haven status with bank secrecy. Increasingly, tax haven regimes with bank secrecy laws in place are accessible to almost anyone with a modem and a computer.[1] (emphasis added)

As improved technology and communications continue to make the world a smaller place, business and consumer dealings have become increasingly international in character.

Consistent with this development has been the growth of electronic commerce and the globalisation of trade and production, as well as shifts in the Australian labour market.

Against this background, the Australian taxation system finds itself in unchartered waters that promises much potential, creates many opportunities and will present numerous challenges to the Australian Taxation Office ("ATO") in administering the Australian taxation system.

It will be the desire of the ATO to properly harness these challenges to realise the full potential that electronic commerce can offer, while providing businesses with the appropriate opportunities to utilise the full benefits of this brave new world. The ATO will need to respond to the challenges quickly as many issues continue to emerge, yet at the same time they will need to exercise caution, prudence and care to ensure that any changes are instituted in a considered and balanced manner.

This article will examine the impact of tax havens and bank secrecy laws in administering Australia's taxation system, including an examination of the impact of electronic commerce.

The overall emphasis or thesis of the article is to assert that tax havens, bank secrecy laws and electronic commerce present many challenges to tax administrators, but also could produce opportunities for them. Having established this, the focus of the article is to then examine various proposals that could be considered to address the challenges identified in the article.

Vastly improved and rapidly emerging technologies, combined with globalisation of the economy has led to business and consumer dealings becoming increasingly international in nature, with a consequent increase in cross-border flows that have become easier, faster and more accessible than ever before.

One of the problems with this is the fear that it may open up greater opportunities for tax avoidance and evasion.[2] In particular, it is the international dimension that potentially makes it extremely difficult for the ATO to collect the necessary information to properly enforce domestic taxation laws.

The availability of timely, detailed, accurate and useful information about a taxpayer's affairs is crucial to the ATO's efforts to effectively and fairly discharge its functions.[3] As John A Calderwood, Director of the International Audits Division of Revenue Canada, observed:

Tax planners are very much aware that if information is located offshore, not necessarily in a true tax haven, it is much more difficult for a 'revenue' to gather evidence to support income tax assessments.[4]

Past experience of the ATO's efforts in this area would confirm that it has been difficult to obtain information once it crosses the border of one country and into another country, particularly if the latter country happens to be a tax haven. Apart from the sheer logistical problems associated with trying to obtain information from an international source, foreign financial institutions are not subject to the same disclosure and regulatory requirements that are applicable to Australian institutions.

Another problem that the ATO has experienced is trying to obtain this information directly from the tax haven government. Given that taxpayers will tend not to voluntarily disclose information to the ATO, coupled with the fact that foreign financial institutions are not subject to the same reporting laws as Australian financial institutions are, the ATO has often been left only with the tax haven government to pursue its investigations. In many instances, this has proven to be a fruitless pursuit, either because the tax haven government does not collate the requested information, or because it has strict bank and secrecy laws that prohibit the disclosure of such information, or simply because it has no agreement with Australia that would authorise the release of the requested information.

Thus, while effective enforcement of taxation laws at the international level relies on cooperation between tax administrators (particularly in the sharing of information), it has been very difficult for the ATO to secure this cooperation when dealing with tax haven countries, especially those that also have strict bank secrecy laws.

Moreover, international cooperation has been hindered in the past by the barriers of national sovereignty, secrecy, reciprocity and competition for tax dollars. These barriers are briefly summarised below.[5]

The main barrier to effective international cooperation is the principle of sovereignty of nations. It is an established principle of international law that a country is not obliged to assist in the enforcement of the tax laws of another country in the absence of an applicable treaty or bilateral agreement: Planché v Fletcher.[6] This rule effectively means that one nation is not obliged to take notice of the taxation laws of another nation. Thus, the ATO cannot use the debt recovery process of another nation for the purpose of enforcing tax liabilities. It also means that tax administrators are not obliged to provide each other with administrative assistance.

It is recognised that this issue is not new in the area of international tax. However, given that it is expected that electronic commerce will lead to more cross-border activities by taxpayers, it is both timely and necessary to consider approaches to overcome this problem. One suggestion to emerge comes from the Committee on Fiscal Affairs ("CFA") of the OECD, which has suggested:

In this context Revenue authorities could develop an Article for inclusion in the OECD Model Tax Convention, or could develop a revised Commentary, to allow for assistance by one State in the collection of tax for another State.[7]

However, such a course of action may prove difficult to implement in the context of the existing network of over 1500 bilateral treaties. Further, the suggestion does not overcome the basic problem when one looks at a tax haven country, where it is almost certainly the case that there will be no double tax agreement ("DTA") in existence to support such a proposition. Nevertheless, it is a measure designed to foster greater international cooperation between countries and on that basis should be given consideration.

In general, bank secrecy laws require that banks maintain absolute confidentiality regarding their clients' accounts and transactions except where disclosure is required, as in criminal investigations by the domestic government. Violations of secrecy laws typically attract substantial civil and criminal sanctions.

Further, the revenue legislation of most nations contains secrecy provisions that would forbid their tax administration from disclosing information concerning a taxpayer's tax affairs to another revenue authority.[8]

Thus, secrecy laws act as a further barrier to cooperation.

Even where secrecy provisions do not apply, there may be undesirable economic consequences (such as capital outflows) from making such disclosures, particularly as the disclosing authority has little control over how the information is used.[9]

The concern here is that given the scarce nature of tax enforcement resources, many smaller tax administrations fear that they will simply become a branch of larger administrations, such as the ATO, with no corresponding benefits accruing to them.

Another barrier to effective cooperation between tax administrators has been an intensified competition for tax dollars. A good example is in relation to transfer pricing, where some have considered that there could be a "general open clash" between tax authorities, as the weak nature of the general arm's length principle and the "greed of the FISCS" leads sooner or later to a general fight for major tax resources.[10] While this battle of finance administrations has not yet occurred, others warn that the current peaceful situation may be precarious, and prophylactic steps should be taken to increase international cooperation.[11]

"Very optimistic about the possibilities but pessimistic about the probabilities."

This is what American writer and urbanist, Lewis Mumford said when he was faced with a series of challenges. Many tax authorities, including the ATO, will feel the same way about the growth of electronic commerce and the Internet generally, which many fear may open up new avenues for tax avoidance and evasion. The challenge for tax administrators is to maximise the potential efficiency gains of the Internet and at the same time protect their revenue base without hindering the development of new technologies.[12]

Before examining the main challenges that electronic commerce will present to the administration of the Australian taxation system, it is instructive to briefly step back and examine the evolution of our tax system in the context of economic developments over time.

One of the principles of an efficient tax system is that taxes should be simple to collect. An effective tax system must feed upon the way an economy generates wealth and it must also bear upon things that people cannot easily hide.[13] The system of Anglo-Saxon England, designed to pay "Danegeld" to the invading Vikings, was highly efficient because it was based on a fixed rate per "hide" or "unit" of land.[14] Not only was land difficult to hide, and therefore an easy taxation target, but also represented the source of income and wealth.

The economy has since evolved to become principally a manufacturing economy. In a manufacturing economy, many people are employed by large companies. Taxes such as pay-as-you-earn ("PAYE") taxes on wages became possible due to the emergence of the modern corporation and its payroll department to calculate, deduct and remit the applicable tax to the ATO. In a manufacturing economy, capital and labour replaced land as the source of wealth.

Also, in a manufacturing economy, large employers, banks and building societies act, in effect, as subcontractors to the ATO, by collecting taxes from employees and then remitting the same to the ATO. This represents a very efficient tax collection mechanism for the ATO. In a fully developed world of electronic commerce, where services dominate over goods and intangibles begin to replace tangibles, this efficient tax collection machine for the ATO will exist less and less.

If one looks forward to what the future holds in the next 10 or 20 years, the landscape of the economy is likely to be very different. It can be expected that during that period of time much of the economy will be made up of services rather than goods - some predict that between 50 and as much as 70 per cent of the economy could be made up of services. If predictions such as these transpire, it will mean that outputs will tend to become more intangible, difficult to measure or touch. A growing number of transactions are likely to be conducted via the Internet or WebTVs, possibly leaving little or no physical audit trail. Electronic systems of cash, such as "e-cash", electronic purses and stored value cards, will be well developed.

Further advances in information technology and communications systems will also facilitate production to be even more international than is presently the case. One implication that this is likely to have is the increased international mobility that could be expected with both capital and labour. This increased mobility can be broken down as follows:

i) Financial capital (savings) - developments in electronic commerce will mean that savings will be able to be moved around the world electronically, almost instantaneously, many times a day.

ii) Industrial capital will also be highly mobile. Instances of this are already becoming evident. For example, in the 1970s, large US corporations earned only about 15 per cent of their revenues from tax havens, or abroad; now it's close to 50 per cent.[15]

iii) Skilled labour will become increasingly mobile in response to increased competition based on different tax rates offered by countries. A good example is the attractiveness to top technologists (such as computer engineers) of the US Silicon Valley, who are attracted there by low Californian taxes. At the same time, at the other end of the employment spectrum, people who are low-income earners will tend to want to be paid in cash to avoid the adverse effects that declared income would have on the level of their social security benefits.

The rise of Internet commerce will present a range of challenges for the ATO, as it will transcend state and national borders and commerce will become truly global in every sense. Small and medium enterprises (SMEs), and more consumers than ever before, will have the opportunity from the comfort of their personal computers or WebTVs, to buy and sell goods internationally.

Already in Australia, large telecommunications companies such as Telstra are running advertisements encouraging people to conduct their businesses through their "Big Pond" Internet service, touting as one of its advantages that consumers can be multinationals too and have access to an international market.

Next ponder the prospect of these goods and services being downloaded electronically and the entire transaction being protected by sophisticated encryption technologies. In this environment, the challenge will be for tax administrators to determine which government is entitled to tax?

A simple example will serve to illustrate the nature of the challenge involved here: A consumer in Australia could download software made in England, marketed via a web site in Los Angeles and delivered by a server located in the Cayman Islands. In this scenario, two issues that immediately arise are:

i) To identify whether a transaction has occurred and, if so, in what jurisdiction.

ii) To assess whether tax should be applied and how it should be paid.

It is quite evident that electronic commerce will have a considerable impact on the way in which transactions are conducted and considered for taxation by the ATO. Once the full impact of electronic commerce is fully experienced, the present tax system that was designed for an industrial world, will face many challenges. As noted above, the process of industrialisation shifted the tax base from land to capital and labour. The new economy, facilitated by the growth of electronic commerce, will require an equally fundamental change to cope with the issues that will arise.

The issues of taxation that arise in Cyberspace include challenges to tax administration, consumption tax and finally, questions will need to be raised in relation to concepts that have become entrenched in our income tax law, such as the concept of what constitutes a "permanent establishment".

Some of the major challenges are summarised below.[16]

In order to properly carry out taxation laws, the ATO needs not only to identify whether a transaction has occurred, but also needs to ascertain where it has taken place and by whom. Verifying the identities of parties to a business transaction may be difficult in the world of "e-commerce". For example, it may be impossible to identify the true owner of a web site conducting Internet business. The problem here is that the mechanisms for tracing identity are weak, in that it is a relatively simple matter to arrange for the untraceable use of an Internet web site. The correspondence, furthermore, between the Internet address (the computer "domain name") and the location where the activity is supplied, carried out or consumed is tenuous: although the address will tell you who is responsible for maintaining that site, it may not tell you anything about the computer that corresponds to the actual Internet address, or even where that machine is located.[17]

Authorities will need to think carefully before responding to this problem by instituting identification and registration requirements as it is likely such requirements will have limited success due to the growing ease with which web sites can be located offshore.

The Committee for Fiscal Affairs of the OECD has responded to this issue by recommending that:

Revenue authorities may consider requiring that business engaged in electronic commerce identify themselves to Revenue authorities in a manner that is comparable to the prevailing requirements for businesses engaged in conventional commerce in a country.[18] (emphasis added).

This recommendation, while adhering to the desirable quality of trying to achieve neutrality between physical business enterprises and virtual business enterprises operating via the Internet, is essentially advocating voluntary compliance. Indeed, the OECD believes that many businesses will provide information on their web sites that can be used to accurately identify the business and its physical location, but also believes that it would be helpful if the information is provided as a matter of "common business practice."[19] Nonetheless, as is the case in the physical world, any voluntary compliance regime that may be contemplated for the electronic world, will need to be reinforced with other methods to enable the ATO to trace businesses that do not provide this information as a "matter of course." An example of a supplementary measure could be the authorising of access for the ATO to Internet Protocol number allocation records to validate identity.

Finally, it is observed that both the current Government and the opposition Labor Party are proposed to introduce an Australian Business Number ("ABN") as part of their respective tax reform proposals which led up to the October 1998 Federal election. While it may not have been specifically proposed for this purpose, the ABN may nevertheless assist in making identity easier to ascertain in an electronic commerce world, by providing common registration for a range of Government authorities (including the ATO) in a single process.

Assuming a transaction can be identified and the identity of the parties ascertained, the next problem is to determine whether a taxable transaction arises, and if so, in which jurisdiction that transaction should be taxed. Individuals and entities engaging in electronic commerce will be able to easily create an Internet address in almost any taxing jurisdiction irrespective of the location of their residence or the source of their activities.

An example of where this could be exploited is the manipulation of location to obtain a reduced or zero rate of withholding tax on royalties. While the problem of establishing physical presence and withholding tax entitlements is not necessarily a new one, it does take on a different dimension in an electronic commerce world. At present, a payer might be able to rely on the postal address of the payee to verify the right to any treaty benefit. However, in a world of electronic commerce, there is no necessary relationship between an Internet address and a physical location.

As an example, a taxpayer may download a digitised photograph from an electronic stock agency and obtain the right to reproduce that image in a magazine or book. The payment for this right would presumably be characterised as a royalty. The seller of this electronic information may claim to be a resident of a treaty country by establishing an Internet address in that jurisdiction without any other connection to that jurisdiction in order to claim an entitlement to a reduced or zero rate of withholding tax on royalties.

Therefore, if withholding taxes are to be imposed on electronic commerce, it will be necessary to establish procedures and standards for verifying the identity of electronic counter parties to confirm claimed entitlements to a zero or reduced rate of withholding tax on royalties. Consideration would also need to be given to determining that if withholding taxes were necessary, how would it be administered?

The challenge presented here is that traditional taxation concepts rely on physical presence or economic connection to a physical location; e-commerce, however, has little dependence on physical location. Thus, as physical location becomes less important in an electronic commerce world, it will become more difficult to determine where an activity has been carried out.

Also, it will become easier to exploit rules based on location by establishing an Internet presence in jurisdictions to claim treaty or other benefits. Conversely, as an Internet presence can easily be relocated, one can expect that manipulation could occur to avoid undesirable tax consequences that may result from having an Internet presence in a particular jurisdiction.

It is generally accepted that the ATO has extensive powers to obtain information from taxpayers and these powers are relatively easy to enforce within Australia. Obtaining information on activities carried out in other taxing jurisdictions, however, requires the use of exchange of information provisions found in tax treaties. Moreover, where books and records are maintained in a tax haven, the ATO will encounter particular difficulties in trying to obtain access to them. Thus domestic disclosure requirements become difficult to enforce. In any event, it is also questionable whether the evidence that tax administrators would be able to produce on transactions that take place in Cyberspace would satisfy the documentation and evidence standards set by tax laws. These "problems" should in theory be easily overcome by appropriate amendments to existing laws governing record-keeping requirements under the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (Cth) ("ITAA36").

However, corresponding legislative changes will need to be considered to cover encrypted data to ensure that it will be no excuse for businesses to claim that they have lost encryption keys and accordingly cannot produce requested information - that is, the onus of production of information must remain with taxpayers.

Increasingly, it can be expected that in an electronic commerce world, trade will turn more and more toward services rather than goods.

This can lead to many problems, including the removal of the ATO's ability to audit an assessment based on comparing inputs and outputs.

For example, if one considers a software company that distributes its programs on floppy disks, the ATO can check the number of blank disks the company purchases and can use that as a rough guide as to how much software it sells. But in the world of e-commerce, when a program can be downloaded over the Internet, the physical check on the scale of business will no longer exist.

Thus, the growth of electronic commerce and the rise of the intangible economy could potentially lead to erosion of the tax base.

Looking again at the Internet, the potential for revenue leakage becomes apparent. Currently, people who shop on the Internet mainly use it to order tangible products, such as books or CDs. In an electronic commerce environment, it is already possible to go on-line and buy books and CDs from a mail-order service such as Amazon.com or Cd Now, who then post the physical item to consumers. There is nothing very different about transacting over the Internet in this way compared to buying it in a shop, as the physical good is still delivered via the post and hence the customs authorities can check it and collect any applicable duties or taxes.

However, more products are becoming intangible - for example, instead of receiving a physical CD ordered on-line and despatched via the post, consumers can now download it to their personal computers. In this context, Value Added Tax ("VAT") or Goods and Services Tax ("GST") become vulnerable to avoidance.

The ability in the future to download products such as videos, CDs and software, combined with being able to reprint books, will pose a serious threat to the ability of the ATO to detect any taxable transaction. This, of course, is unless some form of technology (for example, a "tax chip") is installed into every computer, a prospect that would no doubt raise the ire of civil libertarians. Also, the Government has ruled out the use a "bit tax" that involves taxing each bit of digital information flowing across global networks.[20]

In summary, electronic commerce will see services dominating over goods and the tangible becoming increasingly intangible. In an electronic commerce environment, the tyranny of distance will disappear, small businesses will have access to the world, SMEs will increase in number and transaction costs will be reduced. Notwithstanding these changes, it may be argued that in terms of income tax, there may be little difference between conducting an Internet business compared to any other. However, the greatest impact of these changes will be felt in the VAT/GST arena, because increases in cross-border flows will become easier, quicker and more accessible than ever before. Moreover, traditional intermediaries will not be able to stop the flow of these electronic products across borders as they have been able to do in a physical world. Impacts of electronic commerce on VAT/GST taxes are considered in more detail below.

Australia currently does not operate a VAT or GST system (this will operate from 1 July 2000), but currently relies on a Wholesale Sales Tax ("WST") that applies to goods (which will be abolished from 1 July 2000). Goods are currently defined as being items of tangible property. As already observed, electronic commerce makes it possible for goods that were previously only available in a tangible form, and therefore subject to the WST regime, to be delivered in an intangible form which will not be subject to WST. Returning to the example of music that can now be downloaded directly from the Internet, practically, this will have the same function as music sold as a CD in a shop but it will not be subject to WST as no "good" arises on which WST could be levied.

As more goods and services become capable of being converted into electronic form, the application of sales tax, or for that matter, a VAT/GST, becomes more complicated and the potential for revenue leakage increases considerably. Already intangibles such as travel and ticketing services,[21] software, entertainment (on-line gambling, games, and music), insurance and brokerage services, real estate services, banking, information services, legal services, and increasingly health-care, education and government services are appearing on the Internet. This trend will no doubt continue to increase, both in number and diversity of services that become available.

It is beyond the scope of this article to examine in detail the many challenges to consumption taxes.[22] However, there are two final points worth mentioning in relation to the application of a VAT/GST in an electronic commerce world:

i) Tax administrators will experience three main problems in relation to the application of VAT/GST rules, particularly as they may apply to international services:• Ascertaining when a transaction occurs;

ii) For most businesses, VAT/GST is not a real cost but normally flows through to the final customer who ultimately bears the economic burden of VAT/GST. However, for some businesses that are exempt from VAT/GST, consumption taxes can be a real cost as they may not be able to claim a credit for VAT/GST charged on their business inputs. A good example of this is businesses that operate in the financial sector, such as banks. As banks cannot recover fully the VAT/GST normally charged on their business expenditure, they may look to the Internet to try to achieve real cost savings. As an example, banks may try to avoid VAT/GST by seeking out non-resident suppliers that have no business or other fixed establishment within Australia. Such businesses could then establish by contractual arrangements an "artificial" source of supply outside Australia, thereby avoiding VAT/GST. This type of arrangement would undermine the "place of supply" rules that are a feature of traditional VAT/GST systems.

• Determining where the place of supply is; and

• Attaching a value to the transaction: that is, what would be the consideration applicable to the transaction.

Hence, the advent of electronic commerce not only has implications for the current WST system but will have implications for the VAT/GST system when it becomes operational.

To assess the impact of electronic commerce on Customs procedures, it is necessary to distinguish between "on-line" supplies and "off-line" supplies of goods and services.

Goods or services ordered via the Internet and physically delivered may be described as "off-line" supplies. Activities involving international mail-order transactions of goods will, in principle, continue to be dealt with by the Customs authorities at the point of importation with regard to the collection of both Customs duties and VAT/GST as appropriate. In other words, for the off-line supply of goods and services via the Internet, no new problems are presented to VAT/GST authorities, other than the significant increase in the number of transactions that can be expected. This in turn raises a question mark over the ability of Customs authorities to be able to cope with the resulting demand.

In this regard, three issues need to be considered:

i) More resources will need to be directed to Customs authorities to ensure they can cope with the expected increase in the volume of transactions consequent upon electronic commerce.

ii) It is understood that the ongoing review of the Kyoto Convention[23] by the World Customs Organisation ("WCO") was presented to the WCO Council in June 1999. At this forum, some options to deal with the streamlining and simplifying of Customs clearance procedures was suggested in a common effort toward achieving the full potential of a global market place for consumers.

iii) A review of the customs duty and sales tax-free limit (currently $50) needs serious consideration. Certainly, the OECD has indicated that such a review is appropriate in the context of the global marketplace.[24] The Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit has recommended that the current $50 limit should remain, pending a survey being conducted by the Government, which may validate a change of this value to $150.[25]

By contrast, the supply of "on-line" activities in the form of digitised information poses a serious challenge to the current "place of supply" rules contained in most VAT/GST systems. This in turn creates a real possibility of either no taxation or double taxation being levied in an environment where supplies can be made without the supplier having any form of physical presence.

In examining the overseas experience, the United States has stated that:

The Internet [should] be declared a tariff-free environment whenever it is used to deliver products or services.[26]

The US believes that this concept of a "duty-free" zone should be limited to goods or services delivered electronically. Thus, if a customer downloads some software from the Internet, the transaction should be free from any customs duties. The reasoning here is that in the case of software, tariffs are only imposed on the value of the media (for example, the floppy disk) and not the value of the software itself.

Therefore, if the floppy disk disappears through an electronic transaction, then there is no longer a transaction to which tariffs could be applied.

However, when physical goods are ordered over the Internet and delivered through conventional means, such as a mail-order sale of shoes, then the transaction should be subject to any generally applicable duties, as if the goods had been ordered via the telephone or by mail.

The US approach therefore recognises the distinction between "on-line" and "off-line" supplies and the policy stance taken seems reasonable and contains nothing that would limit the application of VAT/GST (as appropriate) in respect of importations of relevant goods and services.

One of the far-reaching consequences that electronic commerce is expected to have is the elimination of "middle-men," which has been described as disintermediation. The potential impact of disintermediation can be understood by two recent examples.

The first example is that of a company called "Daisytek" that has enjoyed massive cost and time savings through its "SOLOnet" electronic commerce network by adopting a business practice known as "drop-shipping" - where the product is shipped direct from the manufacturer to the customer, thereby by-passing the distributor.

"Amway" has also experienced similar benefits by establishing its "Electronic Link via Internet Services" Internet site. Big savings have been achieved in ordering electronically, where it has been reported that an electronic order can save up to $3 per transaction, which amounts to a considerable savings given about 700,000 orders are placed a year.[27] Other benefits have included provision of on-line information including catalogues and full integration into Amway's back-end systems, which include finance, ordering, inventory and distribution.[28]

Also, the importance of the potential savings in transaction costs through disintermediation cannot be overlooked. For instance, one estimate places the cost of buying software over the Internet at $0.20-$0.50 per transaction as opposed to $5 for a telephone order and $15 for a traditional retailer.[29]

Disintermediation will lead to a diminished role of intermediaries, such as banks and similar institutions. Banks and other financial institutions have been traditional intermediaries for the ATO and in that role have collected taxes such as withholding taxes on behalf of the ATO. If consumers become able to by-pass these intermediaries, the result will be that the ATO will no longer be able to rely on them to collect withholding taxes, which may therefore become less viable sources of revenue for the Government.

Extending the analysis, the elimination of "middle-men" could therefore force the ATO to collect smaller amounts of revenue from a larger number of taxpayers. This would be undesirable, in that it will increase the administrative and compliance costs of the taxation system.

Apart from removing convenient taxing points, disintermediation could lead to a transformation of traditional banking systems, due to the expected availability of a large number of banking facilities on the Internet, many of whom would operate in an off-shore environment and some in tax havens.

This raises other concerns. Should the Reserve Bank lose control of even a portion of the money supply through pervasive electronic cash systems, then this could place Australia's current transaction reporting regime in jeopardy.[30] The Financial Transaction Reports Act 1988 (Cth) ("FTRA") relies on the ability of financial intermediaries, such as banks, to identify suspicious transactions as well as those over certain prescribed limits.

Studies have shown that e-cash, combined with smart card technology:

Could be used to smuggle currency in an out of countries in violation of those [country's] laws. It can also be used to transact normal business without the knowledge of the authorities, which could make it very useful to the "underground economy."[31]

This would create a need for some very creative and determined work on the part of AUSTRAC to keep ahead of the money launderers.

The issue of non-bank involvement in the provision of electronic purse services may require regulatory intervention to ensure that only banks be allowed to issue electronic purses.[32] This is because banks and similar financial institutions would need to follow the standard requirements of identification and reporting. Non-bank institutions, on the other hand, are subject to fewer regulatory requirements and examinations, making them potentially more susceptible to money laundering activities.

Tax havens and offshore financial facilities, once the domain of the rich, will soon be within the reach of the "average" taxpayer. Already a number of tax havens are offering numbered and coded bank accounts, combined with services such as on-line international money transfers as other payment options.

Whilst the principles which govern offshore banking are similar to those which govern traditional banking, the ways in which banking over the Internet may operate in the future will make a crucial difference to the ability of the ATO to counteract international tax evasion and avoidance. Internet banking will offer an ease of access, an immediacy of transferability of money, a degree of anonymity, and low transaction costs, which is not available today. If these features can be combined with well run off-shore institutions in circumstances that provide security, one can expect that a much wider group of consumers will be attracted to electronic commerce.

In a commercial context, the capital of a business can in this way be passed thousands of times through tax havens, in some cases on economic grounds, and finally deposited in its own accounts once it is perfectly clean and backed by a completely lawful activity.[33]

In other words, taxpayers could try to take improper advantage of the globalisation of the international financial system and the fact that these systems operate across multiple jurisdictions, providing easy access and security.

Strategies such as this will make it difficult and costly for the ATO to follow their transactions. As Neil Warren has noted:

For tax evasion to be successful, the complicity of countries prepared to set themselves up as tax havens is fundamental. This complicity must extend to providing a low or zero tax regime for all internet commerce. This must extend to internet businesses and internet banks which deal with internet commercial transactions. The banking system has an important role in facilitating the laundering of any profits made back into the country where the real owner of the commercial website resides. While tax havens have always been with us, what is different now is that the internet makes them accessible to the masses. With bank secrecy ensured in the tax haven, everyone has the potential to participate in large scale tax evasion.[34] (emphasis added).

With the further development of electronic money technologies such as e-cash, the future of money itself as a form of payment could be in doubt. Cyberpayments[35] are quickly emerging as an innovative mechanism for conducting financial transactions.

The advantages of these types of systems include:

i) When transactions occur, either through the Internet or through use of so-called "smart cards", they will provide a speedy, convenient, secure, and anonymous method of transferring monetary value. Because of the anonymity associated with such cards, it may be necessary to consider limiting the use of these cards to low-value transactions to curtail any potential abuse that may be associated with such a facility.

ii) E-cash systems can be used over networks, such as the Internet. Real time e-cash therefore closely emulates paper money, in that it provides person-to-person payments, may have no audit trail and no interchange.

It is recognised that all of these systems are still in their infancy and there are no guarantees that they will meet with market acceptance. Nevertheless, a number of e-cash vendors (including large organisations such as "Mondex") are confident that their products will eventually displace cash as the principal method of payment.

So what are the risks associated with these emerging forms of payment?

At present, tax authorities can request the production of physical records, such as bank statements and other data when it conducts audits of taxpayers.

By contrast, in the electronic commerce world, there will be two types of systems governing cash - "accounted" and "unaccounted" systems.

Accounted systems provide many of the safeguards currently available through physical records such as bank statements and accordingly, there will be no great changes experienced with these systems. However, unaccounted systems pose significant risks. The problem with unaccounted systems lies in the fact that such transfers would leave no physical record, and when instantaneous transfers of money become a reality, there will be no time interval between purchase and supply making it difficult to establish an audit trail of the transaction.

So while we remain in a society where large banks, cash and paper still loom large, transactions are not difficult to verify. In future, however, audit trails may be more difficult to find, especially those associated with unaccounted systems.

Accordingly, the ATO should ensure that electronic payment system providers operate their systems in a way that enables the flow of funds to be properly accounted for, consistent with current laws that apply to the physical world.[36] Careful consideration will need to be given to the applicability of current laws to facilitate the safeguards mentioned above. In particular, governments will need to "encourage" e-cash providers to adopt accounted systems to provide a ready audit trail. This encouragement may ultimately only be possible through changes to banking and taxation laws to ensure that these new systems of cash can be properly accounted for, consistent with laws that presently apply to the physical world.

Many issues arising in relation to the administration of Australia's taxation system have already been identified, along with the issues arising for VAT/GST systems and Customs procedures.

The scope of this article is to examine the impact of tax havens, bank secrecy laws and electronic commerce on the administration of the Australian taxation system by the ATO. As such, it is beyond the scope of this analysis to examine in detail the many issues arising for specific concepts that are contained within the income tax law.

Nevertheless, it is useful to briefly summarise some of the issues that electronic commerce raises in relation to these concepts.

i) Tax Treaties

The issues under this heading may be summarised as follows:[37]

• the definition of when a permanent establishment exists and what profits should be attributed to it;

• the characterisation of income, particularly as regards digitised information and the definition of royalties; and

• the application of special rules, found in some tax treaties, dealing with income from services.

ii) Source and Residence Taxation

Traditional concepts of source-based taxation rely on there being a strong connection between an economic activity and a specific location.

Given that technological developments may make the location and identity of an entity difficult to determine and easily moveable, the implications for source concepts become apparent.

Likewise, traditional residency concepts are based on concepts such as physical presence, incorporation and place of central or effective control. However, technology can make management and control less location-specific. For example, by holding company board meetings via a video-conference in a chosen country, it may be easy to manipulate the rules governing central management and control and thereby, the residency of the company. Thus, the implications for residency need to be considered.

iii) Transfer Pricing

While electronic commerce may not necessarily present any unique problems for transfer pricing, the growth of electronic commerce will be likely to make some of the transfer pricing problems more common. Some of the issues that need thought include:

• possible difficulties in applying the 1995 OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines;

• the likely difficulties in determining profits of enterprises where a high level of "integration" within businesses (especially multinational enterprises) will be possible consequent upon electronic commerce; and

• the likely difficulties in identifying, tracing, verifying and quantifying transactions in highly integrated enterprises.

Even if the challenges outlined above only erode the fringes of the tax system, the impact could be considerable, because the public sector is inherently inflexible and dependent on taxes to fund political commitments given by governments. Consider the following example:

France collects about 50 per cent of its GDP in taxes. If it were to lose 10 per cent or so of that (about 5 per cent of GDP), its budget deficit would have to double, or else, to keep public spending stable, funding for health would be halved.[38]

In other words, a relatively small cut in the tax take could leave politicians with painful choices.

Many of the challenges covered in the previous section of this article do not really pose any new problems, but they do give rise to greater complications due to increased volumes and a change in the way transactions will be handled once electronic commerce is established.

However, new technologies are not to be totally feared, for they may in fact provide solutions to some of these problems. For example, technologies such as "digital certificates" can make it possible to verify the identity of an on-line counterparty and "digital notarisation" can make it possible to verify that electronic records have not been altered.[39]

Thus, it is recommended that one strategy to deal with these challenges is to continue to study these and other emerging technologies, in order to determine whether and to what extent they can assist in alleviating some of the tax administration issues posed by electronic commerce. The issue of the new technology itself providing a solution to some of the challenges created by electronic commerce will be returned to in Part 3 of the article.

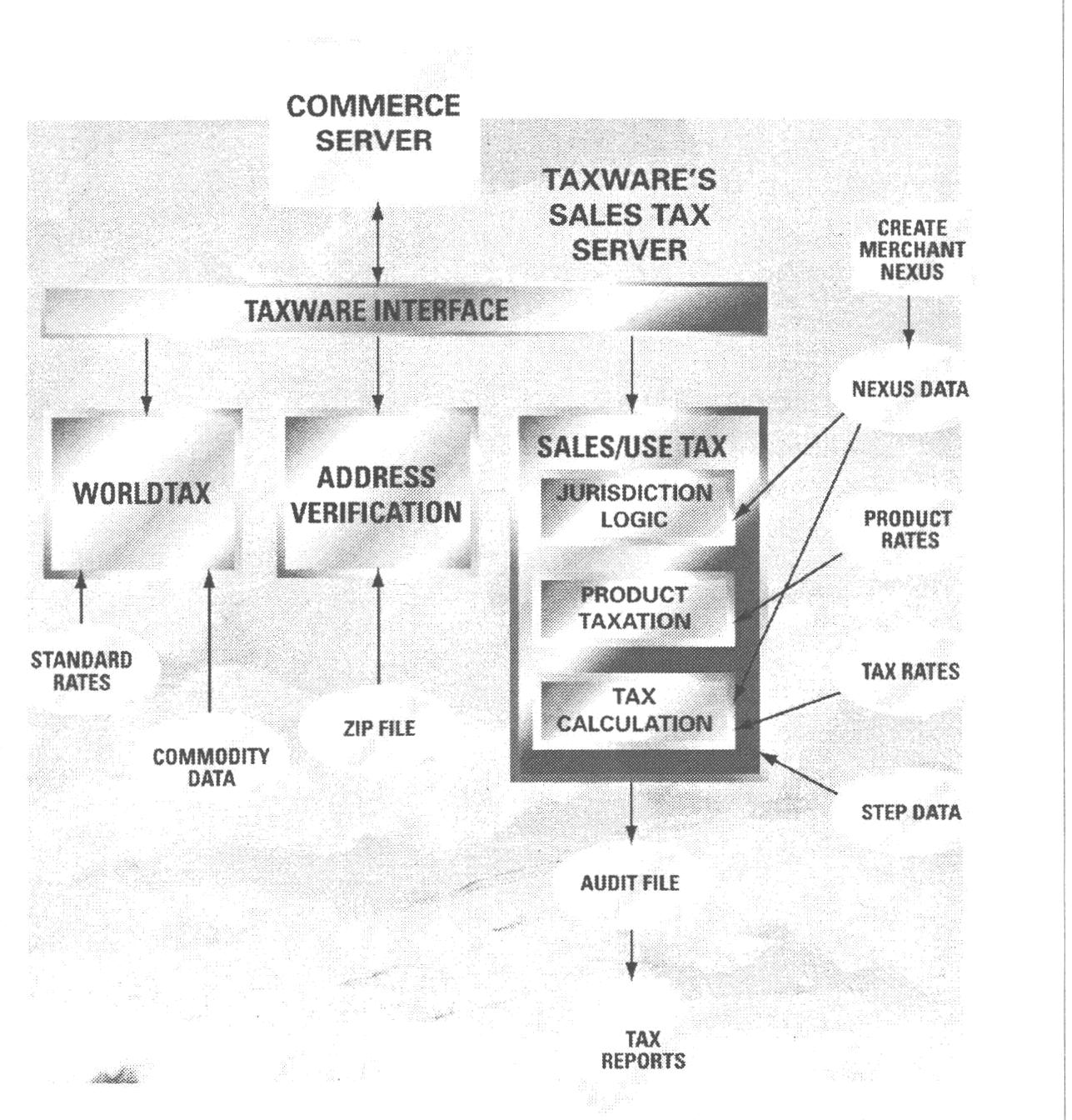

Whilst electronic commerce presents many challenges, it must be understood that there are many opportunities offered by these new technologies as well. For example, the ATO will be able to improve its operations by using improved communication facilities. Already a number of tax authorities have electronic data interchange ("EDI") programs that are making their operations more efficient, improving the quality and timeliness of service to taxpayers.[40]

Electronic data interchange delivers benefits on both sides of the tax ledger by facilitating faster processing, quicker refunds, timely updating of clients' accounts, improved productivity, as well as achieving real savings in time (and also paper) for both taxpayers and the ATO.

New technologies provide the ATO with opportunities for better taxpayer service (for example, by providing information via the Internet), as well as ways to reduce administrative and taxpayer compliance costs and to enhance voluntary compliance.[41] New technologies may help the ATO to reduce administrative costs by:[42]

i) offering lower cost methods of processing information;

ii) allowing further automation of periodic processes, such as payments; and

iii) reducing physical storage costs.

New technologies also offer opportunities to streamline and simplify the process of interacting with the ATO (for example, by electronic lodgement services) and in doing so, the burden of tax compliance and administrative costs can be reduced.

Already in the area of income taxes, a number of countries (for example, Australia, Canada, Denmark, The Netherlands and the US) have implemented some of the following initiatives.[43]

Electronic Funds Transfer ("EFT") systems can replace cheques as the usual method of issuing payments. Direct deposit has a number of advantages over traditional methods of payment, including offering clients a safe, convenient, dependable, and time-saving way of receiving payments, and at the same time saving the Government money through reduced fees and postage. In Australia, taxpayers can also have their income tax refunds deposited directly into their nominated bank account.

Tax returns can already be lodged electronically in Australia by floppy disk and modem. The ATO is also continuing its successful "e-tax" pilot on-line and it can be expected that lodgement by Internet is the next logical step of the use of technology in this context. The advantages of using ELS includes accuracy of tax data, reduced cost to the public and to the ATO, reduced paper use and fast processing of returns - most returns issue in Australia within 14 days of electronic lodgement. To satisfy security concerns, an encryption device is used to ensure that tax information remains confidential.

Tax administrations embracing electronic commerce will be able to accept payroll deductions electronically from any employer who wants to send them that way. This process eliminates the need for employers to file tapes or paper.

EDI systems may be used to streamline the customs commercial process (for example, the recent Canada-United States Accord on the shared border arrangements). This will become more important as the expected increase in the volume of transactions, due to the growth of electronic commerce, is experienced.

Intranet networks may create new possibilities for tax authorities to exchange information in a more timely and secure way. Already the OECD has developed an OECD Standard Management Format for automatic exchange of information[44] and its work is advancing on developing an EDIFACT ("Electronic Data Interchange for Administration, Commerce and Transport") standard for Electronic Exchange of Tax Information. In the field of consumption taxes, the OECD is continuing its work toward developing better systems of international cooperation and means for exchanges of information. This type of facility, once fully developed, will be extremely useful and important to facilitate the sharing of information between revenue authorities.

The ATO has already launched its "ATOassist" web site designed to provide information on a wide range of taxation matters, as well as media releases, speeches and taxation rulings and determinations. Special categories exist for Individuals, Businesses and Students. An "e-tax" TaxPack is also available on-line.

For businesses, added features include ATO forms and a downloadable form filler, to enable businesses to download, complete and then lodge these forms with the ATO. A logical extension to this facility will be the capability to lodge the forms electronically, via the Internet, thereby reducing transaction and information processing costs.

A refinement to ATOassist may be to include advice to common questions, similar to the "Frequently Asked Questions" feature that is found on many Internet sites. This would benefit both the ATO by reducing costs and taxpayers by being able to access this information quicker than by the mail.

At the time of writing, it was understood that the ATO planned to make available to the public, parts of its databases by the end of 1998 which is now incorporated in the ATO website at [www.ato.gov.au].

The ATO has so far taken a commendable approach to utilising electronic commerce to better deliver its service. Consideration should be given to two other initiatives that could be introduced by the ATO to further utilise the opportunities afforded by new technologies:

i) Greater use of email by the ATO

Apart from offering the prospect of faster delivery and convenience, where a taxpayer has an email address this could be used to deliver Revenue authority mail, avoiding the cost and inconvenience of mis-directed mail.[45]

ii) A single registration number

A single registration number for a range of government services is a sensible use of technology to avoid duplication of paperwork for initial registration and for other events such as change of address notifications.[46] It has already been noted that both the Coalition Government and the Opposition Labor Party in Australia proposed to introduce an ABN that would provide the opportunity to realise this possibility.

In conclusion, the ATO must remain committed to the effective utilisation of technology, not only to improve the service it provides to taxpayers but also, by making effective use of both existing and emerging technologies, administrative and compliance costs can be reduced.

Further, by being a leader in the use of technology, the ATO will gain a "hands-on" understanding of new developments and how they can be used by the ATO to better administer the taxation system. By exploring and understanding the technologies, the ATO will be in a position to comprehend the risks but also, and perhaps more importantly, appreciate the positive possibilities and potential that new technologies can deliver to assist with its administration of the Australian taxation system.

The most promising words ever written on the maps of human knowledge are terra incognita − unknown territory. [47](emphasis added)

This quote provides a useful introduction to this part of the article in that it encapsulates one of the biggest challenges and tensions facing electronic commerce. That is the inherent tension that exists between the need to move quickly to establish a stable, conducive framework to allow electronic commerce to develop and the fact that many aspects of electronic commerce are still just embryonic and need to mature before firm policies are established. However, while it is difficult to predict the policy needs in a field that is not yet mature, there is nevertheless a global consensus that all parties need to act quickly to create a certain and conducive environment to allow electronic commerce to develop to its full potential:

The value ... will be measured by the solutions that are found, not just the barriers identified.[48] (emphasis added)

Discussion in this article thus far has been on what the challenges and opportunities provided by electronic commerce could be, but now the focus will be on the more relevant issue of identifying solutions to the challenges. This will involve a consideration of what regulatory and other frameworks will be necessary to harness the full potential of electronic commerce and provide the many promised opportunities that this new medium can offer.

Apart from addressing what the focus of solutions should be, it will also be necessary to determine where the focus of solutions should be directed. In addressing this issue, it is instructive to reflect on some statistics.

As an introductory point, it can be said that the current electronic commerce market is fairly small in comparison to other types of commerce. At the same time, most analysts predict that it will grow by a factor of ten by the year 2000 to about the size of mail-order catalogue sales in the United States.

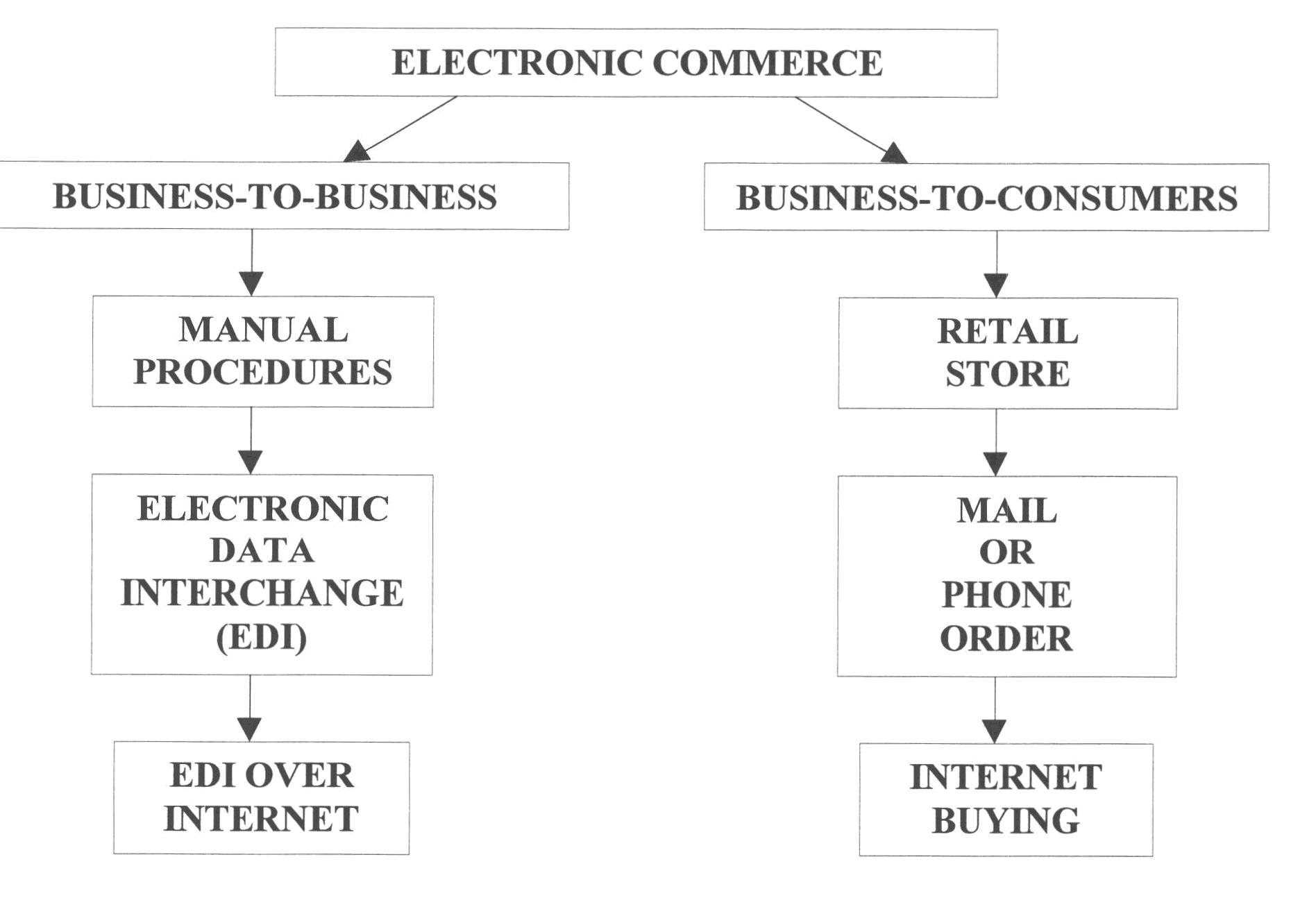

Thus, in the short-run, electronic commerce is likely to remain a relatively minor part of most economies, with most focus being on business-to-business markets:

The consumer driven electronic commerce is not going to be the most significant factor in this equation. Our projections are that, in the next two to three years, up to 80 per cent of electronic commerce will simply be business to business commerce. It will be the transactions of business between suppliers, retailers, wholesalers and distributors in exactly the same kind of format they are using now, but with a global market. They can transact it much more simply and straightforwardly over the Internet, whether it is a private Internet or whether it is a public Internet.[49] (emphasis added)

In the long-run, electronic commerce should succeed in moving economic activity closer to some of the ideals of perfect competition; low transaction costs, low barriers to entry, and improved access to information for the consumer.[50] This is when business-to-consumer electronic commerce can be expected to rapidly accelerate in its growth.

These statistics tend to suggest that the most pressing solutions need to be found in the business-to-business environment, rather than the business-to-consumer environment. However, it is considered essential that solutions not only focus on one sector of the electronic commerce market, but the regulatory, legal and institutional framework that is established should accommodate all sectors, present and predicted. It is only then that a clear, transparent and conducive environment can be established to continue the growth experienced already in the business-to-business sector, while facilitating the expected growth in other sectors, including the business-to-consumer sector.

Electronic commerce has no geographical boundaries and currently few legal ones - it is against this background that solutions need to be developed. Given the global nature of electronic commerce, it is considered that any solutions therefore need to also be global. Indeed, there is wide consensus that no single country acting alone can resolve all of the issues and it will necessarily involve considerable international cooperation between stakeholders to achieve solutions that are clear, consistent and certain.

Further, the impact of electronic commerce is not only global in its geography but also far-reaching in the rules that impact upon it. It is not just taxation or consumer protection laws that need to be considered, but also other areas such as privacy, consumer protection laws and intellectual property rights need to be incorporated as essential elements of any international framework that is established.

Finally, all of these challenges will not necessarily yield to one solution: electronic commerce may be global in nature, but finding universal solutions for all the challenges it creates will not always be possible (or feasible). Some solutions may be technology-based; others may necessarily involve government action while industry self-regulation may provide ways of dealing with some of the other problems. Accordingly, flexibility needs to be inherent in any policy-making process that is adopted. Consistent with this thinking, this article aims to consider a range of possible solutions and policy responses to deal with the issues identified earlier. For it is only by adopting a process of thoroughly considering what all the options could be that a better awareness and appreciation of optimal solutions may be achieved.

In looking at the range of potential solutions to the challenges created by electronic commerce, it is instructive to briefly examine the perspective from overseas as these experiences may provide some useful insights for the direction that the Australian Government should take in determining its policy in this area.

Much work directed at expediting the development of electronic commerce is currently taking place throughout the world, including work carried out in the United States, Europe and Japan, where studies have been directed at looking at the basic framework of policy in the area of electronic commerce.

A brief summary of the approaches taken by these countries follows.

In its electronic commerce initiative, A Framework for Global Electronic Commerce,[51] the United States government presents five principles to guide the strategy in establishing a desirable framework for electronic commerce:[52]

i) The private sector should lead;

ii) Governments should avoid undue restrictions on electronic commerce - that is, the market should drive events, not regulation;

iii) Where governmental involvement is needed, its aim should be to support and enforce a predictable, minimalist, consistent and simple legal environment for commerce;

iv) Governments should recognise the unique qualities of the Internet; and

v) Electronic Commerce over the Internet should be facilitated on a global basis.

The sentiments of the European Commission are similar. In its Report, A European Initiative in Electronic Commerce ("the Initiative"),[53] the European Commission makes the following observations:[54]

i) In order to allow for electronic commerce operators to reap the full benefits of the single market, it is essential to avoid regulatory inconsistencies and to ensure that a coherent legal and regulatory framework for electronic commerce at the European Union ("EU") level exists.

ii) Considering the essentially transnational nature of electronic commerce, global consensus needs to be achieved. The Commission will actively pursue international dialogue, involving government and industry, in the appropriate multilateral forums, as well as bilaterally with its main trading partners.

iii) The political objective of the Commission is to implement this coherent framework of technological, regulatory and support actions, as a matter of urgency, by the year 2000.

Action-oriented proposals for advancing electronic commerce that are directed at creating a favourable regulatory framework and promoting a favourable business environment are contained in the Initiative. One such example is to reinforce international dialogue in the appropriate multilateral and bilateral forums to achieve an adequate global regulatory framework for electronic commerce, in particular in data security, data protection, intellectual property rights, and taxation.[55]

Japan has also undertaken work in this area, releasing its two main initiatives, Towards the Age of the Digital Economy-For Rapid Progress in the Japanese Economy and World Economic Growth in the 21st Century,[56] in May 1997 and Vision 21 for Info-communications,[57] in June 1997.

These initiatives also proceed along similar lines of both the United States and European Commission's approaches as noted above.

These overseas experiences are useful in that they illustrate common themes being put forward by various countries: the need for global solutions to electronic commerce; the need for continued international cooperation between countries; the need to establish a coordinated strategy to deal with the many issues within an appropriate framework and the need for coherent and clear rules that are consistent with the technology.

Finally, consensus seems to exist between countries that to ensure the success of creating the necessary framework for electronic commerce to develop within, a global partnership between the private sector, governments and international organisations is going to be necessary.

All these suggestions, while eminently sensible, may nevertheless represent perfect solutions in an imperfect world. Nevertheless, a useful starting point in examining the solution to any problem is to start with what may be the optimal and then move to the feasible. Thus, in examining the range of possible solutions and policy responses, the discussion will start from the ideal and then move to look at other solutions.

Also, a useful benchmark against which one needs to evaluate these solutions needs to be established. Accordingly, the next section of the article looks at the characteristics that an ideal system of reform should display and then the various solutions that will be put forward can be evaluated in light of these ideal features.

The desirable criteria that any reform proposal should contain may be summarised as follows:[58]

i) The system should be equitable. Taxpayers in similar situations that carry out similar transactions should be taxed in the same way.

ii) The system should be simple. Administrative costs for the tax authorities and compliance costs for taxpayers should be minimised as far as possible.

iii) The rules should provide certainty for the taxpayer so that he or she knows in advance of a transaction what will be the tax consequences. Taxpayers should know what is to be taxed and when and where the tax is to be accounted for.

iv) Any system adopted should be effective. It should produce the right amount of tax at the right time. The potential for evasion and avoidance should be minimised.

v) Economic distortions should be avoided. Corporate decision-makers should be motivated by commercial rather than tax considerations. This applies to both domestic and international transactions.

vi) The systems need to be sufficiently flexible and dynamic to ensure that the tax rules keep pace with technological and commercial developments.

vii) Any tax arrangements adopted domestically and any changes to existing international taxation principles should be structured to ensure a fair sharing of the tax base between countries.

viii) Initially the focus should be on adapting existing tax arrangements to the world of electronic commerce rather than examining the introduction of new forms of taxation.

Having examined the overseas experience and identified the ideal characteristics that any reform proposal should contain, discussion will now focus on specific proposals to deal with some of the challenges posed by tax havens, bank secrecy laws and electronic commerce, along with an evaluation of them in light of the above criteria.

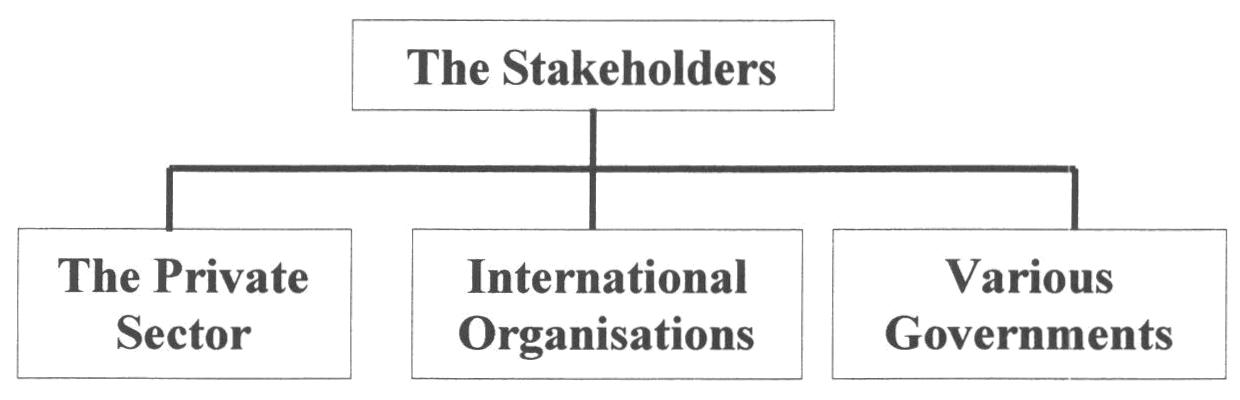

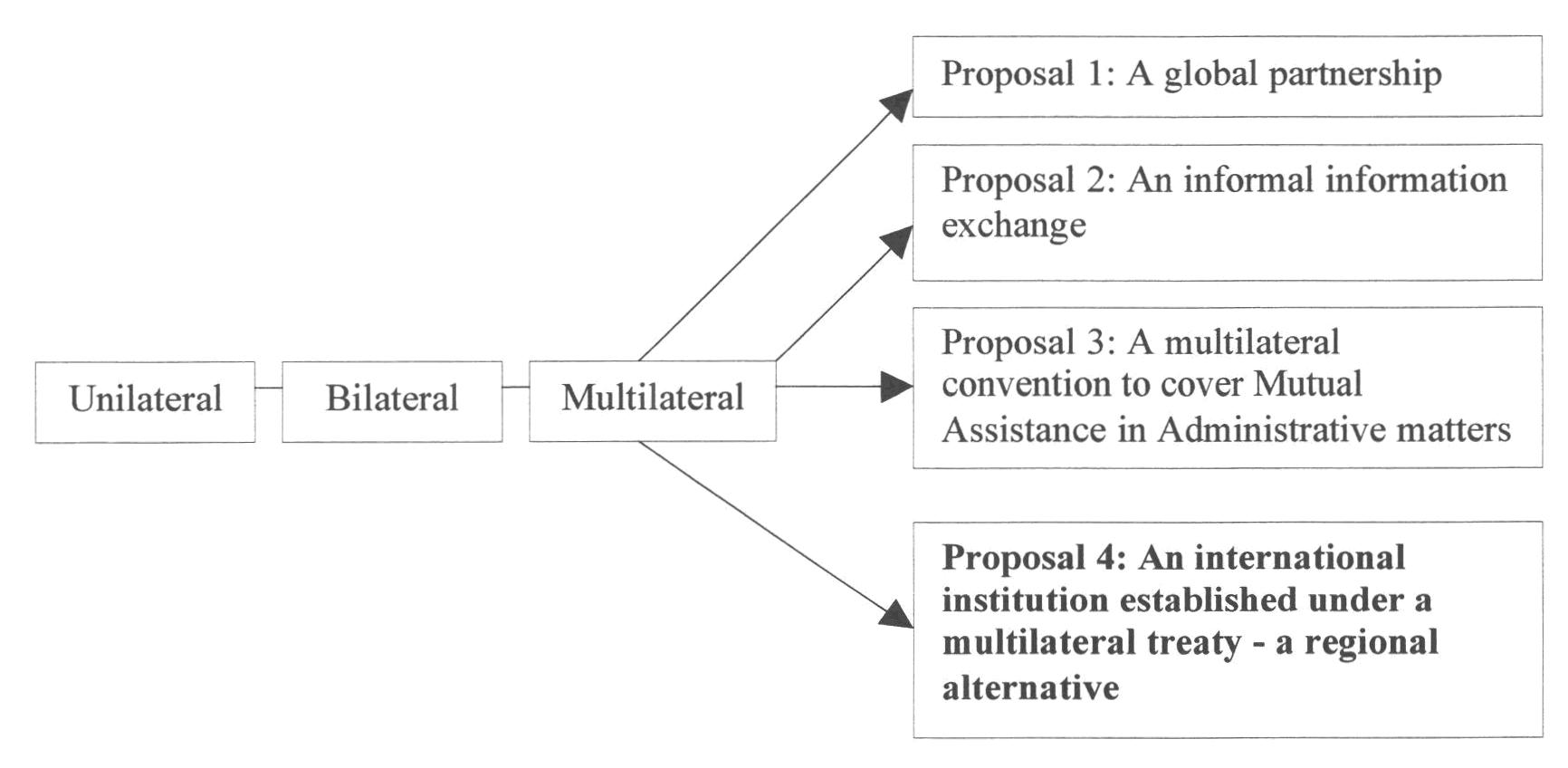

From the preceding discussion, it is clear that given the global nature of electronic commerce and the mutual desire of countries to have laws that are clear, consistent, coherent and coordinated, the solutions to many of the challenges created by electronic commerce ideally lie in discussing the issues and reaching consensus within a cooperative framework as represented below: that is, as an "international partnership" between the private sector, governments and international organisations.

Given that electronic commerce stretches beyond the province of individual countries, this limits the ability of any one country unilaterally being able to dictate policy in this area. While the identification of potential solutions may be elusive, unless some type of "partnership" approach is taken, it will be even harder to develop and implement them in a coherent fashion.

Thus, countries such as Australia must resist trying to assert their own rules in isolation of other countries. This would just lead to fragmentation, confusion and an ineffective outcome that would severely limit any potential gains that electronic commerce may offer.

This partnership between the private sector, governments and international organisations could effectively create a "virtual" international organisation in which the respective strengths of the partners could be brought together while avoiding the undesirable consequences that may flow by formally creating a new supervisory or regulatory authority.

In considering how such a partnership may operate, one may liken its modus operandi to how we govern ourselves in a federation, such as Australia. That is, in our federal system of government, various government departments and ministries come together with the private sector in forging national or regional policies in many areas. A translation of this concept to the international level through the agency of a global partnership in lieu of a federal government may be appropriate to deal with electronic commerce.

Nevertheless, it must be said that the approach as outlined above represents what many would regard as being a utopian solution that may not be feasible in the cold light of day. The political and international realities of this proposal may mean that it is not the panacea to confront the challenges posed by electronic commerce. Indeed, even if such a proposal was to succeed, Australia's comparatively weak position in the world scene, given its small population base and economy, may mean that it would not have a great say in such a global partnership of the kind contemplated by this proposal.

Still, if it is accepted that an international partnership of the type described above is a starting point to the way forward, the next issues to be determined are: (i) agreement on the framework within which the partners need to operate and (ii) establishing the roles of the partners.

Assuming that a global partnership proves feasible, it is necessary to consider what the objectives such a virtual international organisation should be.

Three goals that would be important are:

i) to coordinate the various stakeholders to ensure that a true dialogue between the partners can be established;

ii) to clarify who is responsible for doing what and by when; and

iii) to ensure that consistency among different solutions is achieved.

These objectives need to be achieved within an established framework. It has been suggested that there are three vital elements to this framework:

... three elements ― principles, agreement on the approach to devising solutions to particular problems and assigning the development and implementation of solutions to various organisations ― provide a loose framework for dismantling the barriers to global electronic commerce ...[59] (emphasis added)

These main features of these three elements and the general policy approach that could be adopted may be summarised as follows:[60]

i) here is a need to develop an effective consensus among the private sector, governments and consumers on principles that will guide the formation and implementation of policies relating to electronic commerce. These principles were discussed in a general sense at the Turku conference that was held in Finland in November 1997 and the ministerial level conference in Ottawa, Canada held in October 1998, and provided an opportunity for countries to advance this process further.

ii) An agreement on the basic policy approach to be adopted in devising solutions needs to be reached between the partners. A suggested approach here is for stakeholders (for example, OECD) to bring forward an issue or problem (for example, a taxation issue) for consideration by the global partnership. Consideration of the problem/issue should initially be in light of existing laws (if any) in the area under consideration. If it is agreed that existing laws are adequate to embrace the challenge, it may be that nothing needs to be done. On the other hand, if it is considered that existing laws are either deficient in some way to deal with the problem or simply do not cover the problem at all, then a policy position must

be reached. Solutions to problems will depend largely on the precise nature of the individual problem and flexibility of approach will be needed to ensure the appropriate solution is put forward for the relevant problem: it may be self-regulation or it may be a technology-based solution or it may even involve a binding international protocol, treaty or code with enforcement provisions of some kind. However, the overriding consideration in this process must be that all parties should strive for consensus to achieve the goals of consistency, clarity and coherence in arriving at a solution.

iii) There also needs to be agreement reached on the respective roles of the partners in this process and which organisations will be best placed to deal with and implement solutions that would be consistent with the approach above.

The issues outlined above will be examined in more detail below, when the roles of the partners are considered. At this point, it is useful to mention that the purpose of this principle is to once again promote coherence in policy making while avoiding duplication. Nevertheless, it does not necessarily follow that one solution will emerge from one organisation: depending on the nature of the problem, it may be better to consider and implement many solutions.

Finally, the framework should not be binding or exclusionary: it should instead be a first step in achieving some coherence in the development of solutions.[61] Given that a variety of issues will inevitably be raised in many disparate arenas, the framework should provide for a coordinated approach between partners to avoid duplication and fragmentation in developing policy.

The stakeholders under this proposal are the private sector, various governments and relevant international organisations. Under this proposal, the success of electronic commerce will demand an effective partnership between these stakeholders, with the respective roles as outlined below.

Much of the spectacular growth experienced in electronic commerce can be attributed to the private sector. The continued growth of electronic commerce will largely depend on this leadership to continue - that is, the private sector should lead the way in the world of electronic commerce. Certainly, the consensus of overseas experience appears to accord with this policy stance (see discussion above).

Private sector leadership will be possible in a number of areas, including in the development of industry-led solutions to areas needing self-regulation (such as privacy), standards development and ensuring that inter-operability of systems can be achieved. At the same time, for self-regulation to be feasible, the broader public interest must be taken into account and all measures should be transparent.

The role of the private sector in this process will be two-fold: as partner and pathfinder. In its role as partner, the private sector will, with governments and international organisations, need to establish a stable framework for electronic commerce that will create user confidence and trust and thereby lead to the continued growth of electronic commerce. As pathfinder, the private sector needs to continue to be left to invent the technologies and create the necessary environment within which electronic commerce can flourish.

The role of government is best defined as being one that must be coherent and cautious, avoiding the contradictions and confusions that can sometimes arise when different governmental agencies individually assert too vigorously and operate without coordination.[62]

Governments are faced with a difficult role in trying to balance how to design a framework that adequately protects the tax base without hindering the progress of electronic commerce. In trying to achieve this balance, two questions need answering: "What regulatory impediments need to be removed to promote the development of electronic commerce?" and "What regulatory frameworks are needed to ensure a level-playing field in the world of electronic commerce?"

These questions will not always be easy to answer and competing priorities of different governments will inevitably leave politicians with difficult decisions.

Thus, while it will be the mandate of the private sector to take the electronic world forward, governments will need to play an important supporting role. While the private sector will develop new markets, new products and new businesses, they will need to work in partnership with the government to ensure that a stable framework that creates trust and confidence in the marketplace is achieved.

The coordinating role that governments need to play in this process may be summarised by the following quote:

We cannot afford more than 200 governments on the digital networks if they act in an uncoordinated way, but we also need to have all of them on board in order to govern the networks.[63]

Apart from its coordinating and supportive role, governments will need to show leadership in using these new technologies to deliver many government services, as well as act as an educator to the broader community to encourage them to embrace electronic commerce.

The role of international organisations, such as the OECD, cannot be underestimated if a global partnership is to succeed.

The role of such organisations will be to coordinate the various activities that occur and to bring business and governments together to discuss problems inhibiting electronic commerce and to consider, develop and implement consistent, clear and coherent solutions at the international level.

Already, electronic commerce and the policy issues it raises have been the topic of a number of international meetings raised through the agency of international organisations such as the OECD.[64] These efforts have continued through the ministerial level conference held in October 1998 in Ottawa, Canada, entitled A Borderless World - Realising the Potential of Global Electronic Commerce.

By convening forums of this nature, international organisations can achieve the following outcomes:

(i) An identification and clarification of major policy problems, their potential solutions, and the organisations best placed to develop and implement them.Already arising from the Turku conference held in Finland in November 1997, it became clear that some organisations could play an important role in developing and implementing solutions to specific problems confronting electronic commerce:

(ii) The ability to consider initiatives currently in place to ensure that consistency and coordination exists between them and new solutions.

(iii) To act as go-between between business and government in developing a consensus as to how to best cope with emerging issues.

UNCITRAL for the revision of commercial law and for digital signature, the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO) for intellectual property rights, the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) for Internet standards and technological protocols for self-regulatory mechanisms, the World Trade Organisation (WTO) for telecommunications access agreements, and the World Customs Organisation (WCO) for simplifying customs clearance procedures.[65]

Finally, the OECD itself has through its CFA intensified its work in the taxation area by utilising its subsidiary bodies to examine the impact of electronic commerce in their respective areas of competence. In addition to Steering Groups and Special Sessions convened to examine special issues relating to various taxation issues (eg, consumption taxes), the CFA has established various working parties to deal with the many issues in this area.[66] It has also produced a discussion paper on taxation issues that was presented for discussion at the OECD Government/Business Dialogue on Taxation and Electronic Commerce that was held in Hull, Quebec on 7 October 1998.[67]