Journal of Australian Taxation

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Journal of Australian Taxation |

|

CONSOLIDATION: THE EVOLUTION OF A NEW COMPLIANCE REGIME IN AUSTRALIA

By Irene Filippone

Given the emphasis placed on consolidation by the federal Government in "A New Tax System" and by the Review of Business Taxation Committee in "A Platform for Consultation", the adoption by Australia of a consolidated tax return regime appears inevitable.

The form it takes, however, will ultimately determine whether it actually delivers the compliance benefits promised. This article seeks to assess the perceived benefits of consolidation espoused in "A Platform for Consultation", as well as identify a number of key issues, which still require resolution by the Review and ultimately the federal Government prior to implementing Australia's proposed consolidation regime.

On 31 July 1999, the Review of Business Taxation ("RBT") Committee provided to the Federal Government its blueprint for Australia's taxation system in the new millenium. Part of this blueprint is likely to be the introduction of a consolidation regime for entity groups, accompanied by the repeal of the existing group relief mechanisms. Consolidation regimes currently exist in a number of other countries which are regarded as having comparable tax systems to Australia's, for example, the United States ("US"), New Zealand and Germany.

The adoption of a consolidation regime as part of Australia's taxation system could offer some tangible compliance benefits to corporate and also non-corporate groups. However, in order to achieve such benefits, careful planning is required in formulating the correct consolidation regime for Australia.

This article seeks to analyse and assess the benefits perceived by the RBT Committee in introducing a consolidation regime, which are outlined in Chapter 25 of their Second Discussion Paper, "A Platform for Consultation" ("the Platform"). In addition, the article seeks to identify any significant deficiencies in the current consolidation blueprint offered by the RBT Committee, offering some suggested options for improvement if consolidation is to be implemented.[1]

Broadly, consolidation involves the abandonment of the notion of treating each member of a wholly-owned company group as a single entity, in favour of treating the wholly-owned group itself as a single tax entity.[2] As a result, all intra-group transactions are ignored and tax attributes such as losses, franking credits, etc cease to belong to individual entities within a wholly-owned group; instead they belong to the consolidated group as a whole.

In Chapter 25 of the Platform, the RBT Committee lists the following benefits of implementing such a consolidation regime:

• simplifying the tax system and reducing compliance costs;

• promoting economic growth by reducing impediments to group restructuring; and

• promoting equity by improving the integrity of the tax system.

The introduction of a consolidation regime could deliver such benefits, which would indeed be a positive step forward for entity groups in Australia. However, the portrayal of these benefits in such a positive light by the RBT Committee, given their current blueprint for consolidation in Chapters 25 to 27 of the Platform, fails to recognise that there is at present a much finer balance between introducing a consolidation regime and retaining the status quo for entity groups.

In Chapter 25 of the Platform, the RBT Committee advocates that consolidation will simplify the tax system and reduce compliance costs for entities because it will mean that all intra-group transactions and interests are ignored, and tax attributes such as losses and franking credits are automatically pooled. Unfortunately, it does not appear from the detail provided in Chapter 25 of the Platform that the RBT Committee has provided sufficient evidence to provide taxpayers with confidence in the validity of this statement.

In terms of compliance, for example, the RBT Committee states in relation to consolidation that all inter-entity transactions will be ignored and this, therefore, should result in reduced compliance obligations. This is true to the extent that consolidated groups can rely on their consolidated statutory accounts to prepare their income tax returns. However, it will be a very rare occasion in which consolidated statutory accounts can actually be relied upon without significant amendment.

Firstly, consolidated statutory accounts consolidate less than 100% subsidiaries. The proposed consolidation regime only consolidates 100% subsidiaries. Therefore, transactions involving less than 100% subsidiaries will require exclusion for the purposes of preparing a consolidated income tax return.

Secondly, consolidated statutory accounts also include foreign subsidiaries. The proposed consolidation regime only consolidates Australian subsidiaries and therefore, transactions involving such foreign subsidiaries will also need to be excluded for the purposes of preparing a consolidated income tax return.

Further compliance issues will arise where foreign owned Australian groups prepare their consolidated statutory accounts based on overseas consolidation principles such as the "US or UK GAAP". In these circumstances, greater compliance costs may be incurred in preparing Australian consolidated income tax returns.

Simplicity will also apparently result from consolidation due to the fact that consolidation ignores inter-entity transactions. However, whether inter-entity transactions can be ignored, even under a consolidation regime, is questionable in itself, given the various other measures proposed by the RBT Committee in the Platform, for example possible methods by which a corporate group would be required to calculate the cost base of shares in a subsidiary being sold.

It terms of simplifying the taxation system, examples need only be sought from the US. The US consolidation regime is extremely complex and the legislation is voluminous. The blueprint for consolidation provided in Chapter 26 of the Platform appears to adopt a number of the US style consolidation principles. Therefore, it would appear likely that once the operational and legislative details of consolidation begin to be fleshed out, a "simple" regime may be impossible to achieve.

Despite the benefits achievable through the pooling of tax attributes, overall, consolidation is unlikely to achieve the benefits of simplifying the tax system and reducing compliance costs for entities advocated by the RBT Committee. Rather, it is likely to make tax compliance that little bit harder.

The second stated benefit of the consolidation regime concerns the promotion of economic growth through less complex group restructuring. It is true that ignoring transactions within a consolidated group (this is of course qualified by the comments above) will make restructuring easier from an income tax perspective. In this sense, there is a benefit to consolidation. However, whether this benefit is significant enough to justify the introduction of the regime is again questionable, as stamp duty will still remain a significant cost to group restructuring even after consolidation is introduced.

Many corporates at present would argue that stamp duty, rather than income tax, is a greater cost and impediment to group restructures. Although a large number of stamp duties will be phased out from 1 July 2001,[3] stamp duty on real property transfers will remain an impediment to group restructuring. Furthermore, given the inconsistency between the stamp duty group restructuring relief offered by the various state and territory governments, merely improving the income tax side of group restructuring is insufficient to achieve the promotion of economic growth required.

The third stated benefit of a consolidation regime is that it provides an enhancement to the integrity of the tax system. The treatment under the consolidation regime of the entity group as a single tax entity enhances the integrity of the tax system by: eliminating the problem of double taxing a single economic gain; eliminating the duplication of losses; and eliminating the ability to value shift. This integrity, however, is also enhanced for other entities outside the proposed consolidation regime by the measures outlined in Chapters 28 and 29.

Chapter 28 discusses the fact that under the current CGT regime, the duplication of gains and losses, whether capital or revenue, realized or unrealized, can occur in relation to the disposal of interests in an entity. Chapter 28 then proceeds to propose a number of options, which the RBT Committee believes are capable of achieving a single recognition of gains and losses in this context. Chapter 29 provides possible solutions to the problem of CGT value sifting outside the consolidated group.

Given that the resolution of these integrity issues can and will be achieved by the measures proposed in Chapters 28 and 29 regardless of consolidation, this stated benefit in reality potentially adds little to the credibility of introducing a consolidation regime.

Indeed, given the precariousness of the other arguments in favour of consolidation outlined by the RBT Committee, the achievement of integrity enhancement without consolidation, is a strong argument in favour of implementing such reforms without the introduction of this additional level of compliance obligation.

As can be seen from the analysis above, the benefits of consolidation under the proposed regime as stated by the RBT Committee in Chapter 25, do not form a compelling argument for the adoption of the regime.

Therefore, if the introduction of a consolidated regime into Australia is to produce real benefit to taxpayers, not only must it be modified to actually achieve the various RBT stated "benefits" discussed above, but the RBT Committee must ensure that it also addresses the following key issues:

1. Consolidation to a non-resident parent entity;

2. Dividends received from non-consolidated group entities;

3. Pre-consolidation losses;

4. Minor shareholdings;

5. Timing of entry and exit for consolidated group members;

6. Joint and several liability of entities exiting the consolidated group; and

7. The changing nature of assets within a consolidated group.

The development of a consolidation regime in Australia which does not encompass the ability to consolidate to a non-resident parent would not only result in little compliance benefit for many entity groups, but would substantially disadvantage a large number of corporate groups currently investing or proposing to invest in Australia.

The RBT Committee should, therefore, abandon the requirement for a head Australian holding company in order for consolidation to be available

to a wholly-owned group of entities. Consolidation to a non-resident holding entity should be available, provided, of course, that all other requirements are satisfied.

Given the variety of organisational structures currently in existence in Australia, requiring a "head Australian holding entity" under consolidation would be contrary to the aims of equity, efficiency and simplicity. It would result in fragmented and smaller consolidated groups and the wasting of tax attributes that should be able to be utilised in a larger group context as is the case at present.

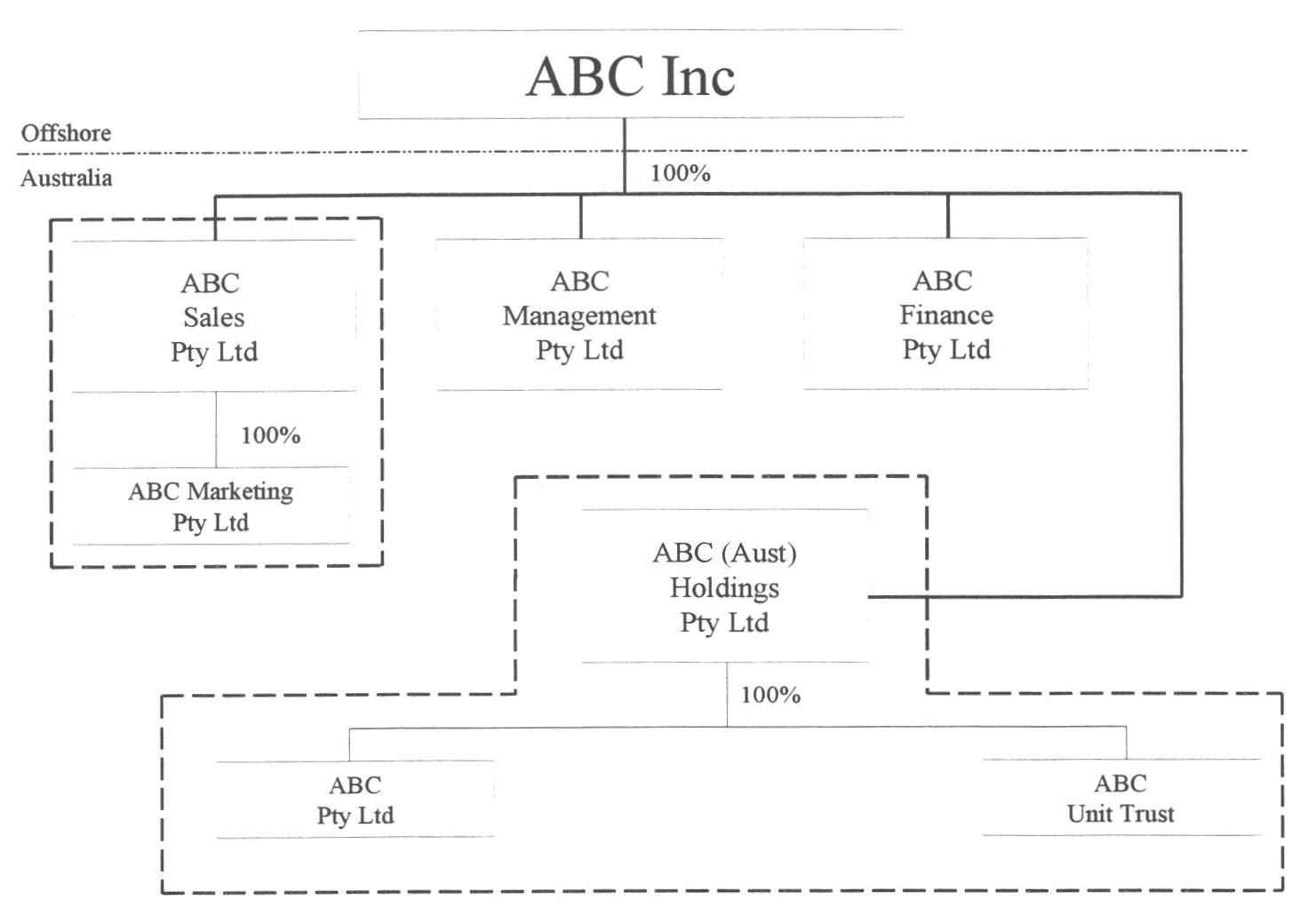

The requirement for a "head Australian holding entity" may also result in some foreign wholly-owned Australian groups preparing numerous consolidated tax returns, in effect, fragmenting existing groups. Worse still, some entities in a wholly-owned group may fall out of consolidation altogether by virtue of being owned directly from overseas. These groups would be in a far worse tax position under consolidation than at present. The diagram below illustrates these points:

As can be seen from the diagram, despite all entities being wholly-owned by a common parent, the requirement that a "head Australian holding entity" exist results in two distinct consolidated groups. Moreover, two entities, which under the current regime could benefit from group relief measures, would be isolated for tax purposes. Creating such fragmented groups under consolidation would certainly be a significant detriment to a large number of existing entity groups.

The RBT Committee, to some extent, recognises these difficulties and raises at para 26.32 of the Platform, the possibility of extending transitional CGT roll-over relief to allow groups to install a "head Australian holding entity" to facilitate consolidation. Such transitional relief would be particularly useful for both trusts and foreign-owned companies. However, this is not enough. Additional costs would still be incurred, for example, as discussed in Parts 3.1.1 and 3.1.2.

From a foreign held group's perspective, interposing a "head Australian holding entity" to facilitate consolidation of its entire Australian wholly-owned group could trigger substantial foreign tax liabilities. Reorganisations of this nature would require a disposal of assets such as shares, units, etc held by the foreign parent in the Australian entities to the "head Australian holding entity". The Federal Government would be unlikely to have any influence in encouraging foreign transitional relief in such a case, nor is it likely to provide domestic tax relief for such foreign taxes. As far as foreign-owned groups are concerned, therefore, their need to incur such costs could seriously damage Australia's attractiveness as an investment destination in the future.

A significant cost of establishing a "head Australian holding entity" would be the stamp duty imposts on the transfer of shares, units, property, etc required to achieve such a structure. Although stamp duty on marketable securities will be phased out with the introduction of the GST, this phase-out will be very gradual if at all and as stated above will not extend to real property transfers. This is recognised at paras 26.33 and 26.34 of the Platform where the RBT Committee makes mention of stamp duty.

It would seem that unless firm commitment could be obtained from all state and territory governments that transitional relief will be provided in respect of stamp duty incurred for the purposes of reorganising to become entitled to consolidation, the introduction of the regime will be an expensive burden to entities currently operating in Australia.

As stated previously, it is not uncommon for a number of head Australian entities to exist within the same foreign-owned Australian group. Requiring such groups to have a further "head Australian holding entity" may result in Australia being an unattractive business destination from a risk management and foreign tax planning perspective. Although this requirement for a "head resident entity" exists in the US consolidation regime, upon which much of the blueprint in Chapter 26 appears to be based, the US economy's strength and dominance is vastly different to Australia's. Indeed, the US is a capital exporter whereas Australia is a capital importing nation. Attracting foreign investment is obviously of greater significance to Australia.

Given that one of the aims of the RBT Committee is to foster Australia's international competitiveness by ensuring that the business tax system does not influence business decisions unnecessarily, to impose such a requirement would discriminate against such foreign investment into Australia.

Creating a regime which allows for the consolidation of an Australian entity group to a non-resident holding entity will be difficult to mesh with Australia's CGT regime. Although New Zealand allows consolidation to a non-resident holding entity,[4] adopting a system similar to New Zealand will not be possible as capital gains are not taxed in New Zealand. However, the fact that consolidating to a non-resident holding entity will be difficult to legislate should not be an impediment to its achievement

One example of the difficulty from a CGT perspective of consolidating to a non-resident parent entity is provided by the use of the asset-based model described in Chapter 27 of the Platform. If the asset-based model is adopted and consolidation to a non-resident parent allowed, potential CGT liabilities could be lessened as compared to requiring a foreign parent to consolidate to a "head Australian holding entity".

In this regard the asset-based and entity-based models are two options proposed to enable the determination of the consolidated group's cost base in the equity of a member entity being sold or exiting the group.[5] Broadly, both these models operate to calculate the CGT cost base of the equity in the exiting entity, based on the CGT cost base of that entity's assets. Therefore, the application of either of these models without modification, could potentially reduce CGT exposures of those foreign-owned Australian groups that did not have a head Australian holding entity.

Albeit adding further complexity, appropriate legislation should be able to satisfactorily resolve these issues.

Under the consolidation regime as currently proposed in Chapter 26 of the Platform, dividends received from shareholdings external to a consolidated group could erode the consolidated group's revenue losses.

At present, many corporate groups are structured such that external (non-group) dividends are received direct by the group's ultimate holding company. The ultimate holding company, therefore, acts as a dividend conduit to shareholders and will rarely have active trading businesses capable of generating losses. Losses may be generated in other active trading companies within the group and, therefore, by way of this structure, these trading losses need not restrict the flows of external dividends to the group's ultimate shareholders. In this way, losses can in effect be quarantined and can be used by the group to be offset against trading profit, not dividends received.

However, by way of contrast, under the consolidation regime as currently proposed, the "single entity" concept will result in an erosion of a net tax loss of the consolidated group on the group's receipt of external dividends. This is due to the fact that trading losses cannot be isolated within specific trading entities as at present. Consequently, unless this issue is resolved such that receipts of dividends by a consolidated group do not erode the group's loss pool, consolidated groups will be forced to de-consolidate companies/entities that could potentially fall into a tax loss position. Alternatively, consolidated groups could be forced to sell off less than 100% subsidiaries and other minority equity investments in respect of which they cannot control the flow of dividends into the consolidated group.

The RBT Committee must address and resolve this issue in relation to externally generated dividend flows prior to releasing its recommended consolidation regime structure. If not addressed, it would inevitably result in tax becoming a major impediment to a group's investment decisions.

The third key issue which must be addressed by the RBT Committee in developing a consolidation system that will maintain an equitable position, while providing compliance benefits to taxpayers, relates to the treatment of pre-consolidation losses. The RBT Committee outlines six options in Chanter 26 to deal with pre-consolidation losses.

It would appear that on their own, none of six options proposed in the Platform can achieve an equitable and efficient transition of pre-consolidation losses into a consolidated group. However, the combination of options, particularly Option 1, as a transitional measure, in addition to either Option 5 or Option 6, on a go-forward basis, could provide adequate relief to entity groups.[6] Each of Options 1, 5 and 6 do, however, require some refinement.

Regardless of whichever other option was introduced, as a transitional measure, it is likely that aspects of Option 1 will be adopted by the RBT Committee. Option 1 states that only losses incurred while in a wholly-owned group and currently capable of being transferred to other group entities will be able to be brought into the consolidated group, with other existing losses being extinguished. A number of transitional concessions are however, provided.[7]

The narrowness of the terms of Option 1, in that it is based on loss transferability, means that Option 1 will require some refinement to make it an efficient transitional measure for non-corporate entities such as trusts.

The proposed requirement of loss transferability outlined in Option 1 will mean that any losses in existence in trusts which are to form part of a consolidated group will be lost on entry because, currently, trusts are unable to transfer losses. If the RBT Committee is proposing to, in effect, tax trusts like companies and to allow related trusts to be part of any proposed consolidation regime, then transitional rules will be required to deal with pre-existing trust losses. These trust related rules could either be part of a modified Option 1 or an additional trust focussed transitional measure.

On a go-forward basis, after Option 1 achieves transition into consolidation, Option 5 appears to be the more equitable of the remaining options prepared by the RBT Committee. Option 5 proposes that where the consolidated group cannot satisfy the existing loss transfer rules,[8] it need not lose the losses in that loss entity but could instead, quarantine any carry-forward losses in that entity for use against future income of that loss entity.

No mention, however is made of how Option 5 would deal with loss-subgroups. This issue is dealt with by the US Treasury reg 1-1502, as the US applies a modified version of Option 5 which allows loss-subgroups to utilise pre-consolidation losses against income earned by that subgroup during consolidation. This is effectively a system of consolidated loss-subgroups existing within the broader consolidated group.

If Option 5 were to be adopted, it would be essential that the loss-subgroup issue be dealt with and included within the framework of quarantining losses. Although this may cause complexity, in the sense of having to prepare "mock" consolidated returns for loss-subgroups, this may have to be done in any event to track certain intra-group transactions.[9]

It is assumed in respect of Option 5 that although past losses will be quarantined, any losses incurred by the quarantined member entity while a member of the consolidated group would automatically flow into the consolidated group's loss pool. This would be consistent with the philosophy of the regime and would ensure loss-subgroups remained in existence only as long as necessary to absorb past losses. If this were not a feature of Option 5, and indeed also Option 6 discussed below, both options would prove inefficient and inequitable from a consolidated group's perspective.

Option 6 also appears to be one of the more equitable options proposed by the Platform and would be a preferred option if, as discussed in the context of Option 5, any post-acquisition losses incurred by loss entities left outside the consolidated group ultimately formed part of the consolidated group's loss pool. Option 6 states that it may be possible for consolidated groups to leave wholly-owned loss entities outside the consolidated group until their carry-forward losses were absorbed.

Ensuring Option 6 operates in this way would be essential to the efficient use of tax attributes by consolidated groups. Any new losses incurred by a loss entity while a wholly-owned entity but left outside the consolidated group because of pre-consolidation losses, should fall into the consolidated group's loss pool. These new losses could enter the consolidated group either when incurred or when the loss entity enters the group as a result of absorbing all pre-consolidation losses.

One additional refinement to Option 6 would involve providing entities left outside a consolidated group with the ability to elect to forego all pre-consolidation losses as a means of entering the consolidated group. In this way, groups could choose whether it was efficient to exclude entities from consolidation on the basis of their pre-consolidation losses.

The existence of minor shareholdings resulting from employee share ownership and non-voting financing shares should not preclude an entity's ability to form part of a consolidated group. Like New Zealand and the US, Australia must resolve to allow the existence of such minor shareholdings if consolidation is to prove effective.[10]

Promoting employee ownership of enterprises is seen as a positive enhancement to business productivity. Its promotion should, therefore, not disadvantage entities from a taxation perspective.

Finance shares, particularly when they are temporary in nature and non-voting should also not preclude consolidation. Where such shareholdings are utilised as merely a financing tool and in no way affect the group's control over the entity, they should be ignored for the purposes of consolidation. The US consolidation regime, for example, disregards such non-voting preferred stock[11] in determining a corporation's consolidation status.

Disregarding such minor shareholdings would also strengthen the integrity of the proposed consolidation regime. Allowing such minor shareholdings to trigger the de-consolidation of an entity would enable groups to readily take specific companies outside the consolidated group if they so chose. It could, therefore, lead to abuse and hence the need for complex anti-avoidance rules. To simply "carve out" these minor shareholdings would be a more appropriate solution.

Chapter 26 of the Platform states that entities can choose to form part of a consolidated group and if that occurs, all wholly-owned members automatically form part of the consolidated group. However, no mention is then made in Chapter 26 of the precise timing of an entity's entry or exit from a consolidated group. This issue will be of critical importance to consolidated groups and will influence whether compliance will be made simpler.

In order to minimise the compliance issues associated with consolidating entities entering and leaving a consolidated group, it would be appropriate that the timing of entry and exit equates to the timing of the acquisition or disposal of a 100% interest in an entity. Therefore, Australia should seek to adopt the US approach in this regard as outlined in s 1501 of the US Internal Revenue Code.

By basing the timing of entry and exit on the acquisition/disposal date, consolidated groups would absorb the part year income of entities acquired and ignore the income/transactions of members exiting from the date of disposal.

The Platform does not address the issue of what level of tax liability individual entities will retain if they ultimately exit a consolidated group.

The resolution of this issue is important for a number of reasons:

• Whether a previous consolidated group member entity remains exposed to tax liabilities incurred while a member of that group will impact on the value placed by external parties on such an entity; and

• This valuation issue is compounded by the fact that entities exiting the group leave behind all franking credits, foreign tax credits, revenue and capital losses generated while members of the group.

Entities leaving a consolidated group should cease, at that time, to be jointly and severally liable for the group's tax liabilities. If this is not proposed as a general rule, it should at least be applicable in situations where entities are sold outside the group on arm's length terms at full value. In this case, the asset value of the entity is still retained in the group in the form of cash proceeds from its disposal and, therefore, the group's ability to pay its tax liabilities is not diminished.

An important issue requiring resolution in the context of a single entity for consolidation purposes is how to treat assets that may change their nature depending on whether they are viewed from the perspective of the particular entity owning them as compared to the perspective of the consolidated group as a whole. For example, although an asset may be treated on capital account by the particular owning entity at the time it is disposed of, when viewed in the context of the consolidated group as a whole, this asset may actually be regarded as revenue in nature. The issue is therefore how to treat any gain from the disposal of such an asset.

The Platform proposes two possible approaches to this issue in para 26.46:

Proposal 1: Adoption of the generalised unified treatment for investment assets across the board which would operate separate to the single entity concept; or

Proposal 2: If a generalised unified treatment for investment assets was not adopted, then the asset's character would be determined according to the character of the relevant transaction in regard to the group as a whole. This is consistent with the single entity concept.

It does not appear that either of these proposed treatments would be adequate.

Firstly, Proposal 1 is unlikely to be adopted as it would essentially eliminate the current differential tax status of capital and revenue assets more generally, that is, in effect eliminating the concept of a "capital gain".

Due to the likely failure of the adoption of treatment proposed in Proposal 1, Proposal 2 would apply as a result of the single entity concept. The operation of the single entity concept could however, provide a distorted view of transactions. Furthermore, depending on the size and activities of the group, determining the character of a transaction of this type in a group context may be extremely difficult.

Despite the existence of the single entity concept, the preferred approach, in keeping with the principle of ignoring intra-group transactions, would be to look at the character of the asset in the hands of the individual member entity actually disposing of the asset outside the group. It should be the character of the asset in that entity's hands, which should finally determine its revenue or capital nature for assessment purposes, without reference to its nature from the consolidated group's perspective at all. That is the approach adopted in New Zealand,[12] where the consolidation regime also adopts the principle of ignoring intra-group transactions.

Although consolidation can provide significant benefits to compliance for entity groups, it can also result in additional compliance costs and obligations being imposed. Either way, it would not appear that the benefits of adopting a consolidation regime which could truly provide compliance benefits and enhance investment in Australia is immediately evident from the blueprint provided by the RBT Committee in the Platform.

However, it is likely that a recommendation will be made by the RBT Committee to introduce a consolidation regime when its report is released at the end of July. Accordingly, in order for such a regime not to overly detriment wholly-owned groups as compared to the status quo, as a first step, the RBT Committee should at least resolve the seven key issues raised in this article. If this cannot be achieved, the grouping system as it currently stands should be maintained, given that other measures will be introduced to achieve the promotion of greater "integrity" apparently needed and proposed in Chapters 28 and 29 of the Platform.

Irene Filippone is a senior associate of Shaddick & Spence. She works extensively in the areas of international taxation, group restructuring/reorganisation and business divestment. Irene has a Commerce/Law(Honours) degree from the University of Melbourne and is a Chartered Accountant. She is also a fellow of the Taxation Institute of Australia. Irene is currently completing a Masters of Law.

[1] The analysis provided is consistent with the submission made to the RBT Committee by Shaddick & Spence in response to the Platform. The submission prepared by Shaddick & Spence can be found on the RBT website. It is submission number 30, lodged on 6 April 1999.

[2] Refer Chapter 25 of the Platform.

[3] Refer RBT Committee, "A New Tax System" the Platform 79, for a list of business stamp duties to be phased out by the states and territory governments as a result of the introduction of GST.

[4] See ss FD 3 and OB 1 in the Income Tax Act 1994 (NZ) ("NZ ITA94") for the definition of "eligible company".

[5] Refer Chapter 27 of the Platform.

[6] Options 2,3 and 4 are included at paras 26.92-26.97. Option 2 allows carry-forward losses to be brought into a consolidated group subject to a modified same business test; Option 3 is the adoption of Option 2 but with an additional test limiting the revival of old losses: Option 4 allows only a specific proportion of carry-forward losses to be brought into the consolidated group.

[7] Refer Chapter 26 of the Platform, para 26.91.

[8] The loss transfer rules will be repealed on the introduction of consolidation − refer Chapter 26 of the Platform, Principle 3.

[9] As per the "entity-based model" described in paras 27.7 and 27.11 of the Platform.

[10] The New Zealand consolidation regime excludes from the calculation of 100% ownership up to 3% of employee share scheme shareholdings and up to 1% of shareholdings which satisfy company law requirements (ss FD 3 and OB 1 definition of "eligible company" of the NZ ITA94). The US consolidation regime requires a minimum of 80% voting and value test to qualify for con-solidation (s 1504(2) of the US Internal Revenue Code ("IRC")).

[11] IRC, ss 1504(2) and 1504(4).

[12] See NZITA94, s FD 10.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/JlATax/1999/20.html