Journal of Australian Taxation

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Journal of Australian Taxation |

|

INCOME TAX DISPUTE RESOLUTION: CAN WE LEARN FROM OTHER JURISDICTIONS?

By Suzette Chapple

This article compares the dispute resolution systems in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States. Various aspects of difference are considered as to whether they could be adapted for Australian conditions including a specialist Tax Court, the New Zealand pre-assessment processes and evidence exclusion rule, and the US acquiescence policy and regular and memorandum decisions. The issues of Tribunal costs and the payment of tax in disputes are also considered briefly.

Taxation law is the most litigated area of the law in Australia. By its nature, it affects the lives of most Australians. The existing tax laws are complex and in a form not easily understood by most people.[1]

The first Federal income tax was introduced in 1915 as a wartime measure and was not only relatively simple but also a relatively minor tax in terms of the amount collected. However, particularly in the last twenty years, income tax has become the major source of revenue for the Federal Government[2] not least due to the wider range of taxable income including capital gains and fringe benefits. As such, it has a significant impact both on taxpayers and the functioning of the economy. However, unless rates are increased (which would not only be unpopular but would also inhibit the economy both for business to compete internationally and individual motivation

to work harder), income tax collections are unlikely to increase markedly in the future and possibly remain static or decline in real terms due to an ageing population, high unemployment and difficult economic times. As such, the Government has to find more revenue by other means and thus introduced the goods and services tax ("GST") which has a broader base and taxes an area (services) that is presently not taxed by way of indirect tax. The introduction of the GST, however, should not be allowed to mask the fact that income tax will still be the principal source of taxation revenue.

A further factor to be taken into account is the legislation, which has expanded greatly to become "one of the most complex and voluminous statutory schemes in Australian law".[3] In various forums, Hill J has been particularly critical of the legislation as being "of almost unrivalled complexity,...in some cases unintelligible,...[and the] language is as convoluted as it is confusing"[4] and "drafted with such obscurity that even those used to interpreting the utterances of the Delphic oracle might falter in seeking to elicit a sensible meaning from its terms".[5] He has further commented that some provisions were "of mind-numbing complexity" and that legislation should "be expressed both in ideas and in language that are clear" and "it should not be expected that the courts will construe legislation to make up for the drafting deficiencies which revel in obscurity".[6] Other reports have also referred to the "complexity, obscurity, and uncertainty of drafting"[7] of the legislation. This complexity ensures that there will be disputes, which if not resolved internally will be subject to independent merits review or be appealed to a court.

Whilst the aim must be to prevent unnecessary disputation, those disputes inevitably arising need to be resolved fairly, expeditiously and according to law. As such, the two objectives of a taxation dispute resolution system are to resolve the case in dispute and, where appropriate, to clarify the law so as to provide guidance to both taxpayers and primary decision-makers.[8] To the extent that the system improves the quality of primary decisions, this is referred to as the normative effect. This is of particular importance not only because of the complexity of the legislation but also because many of the core concepts, such as "assessable income", are not defined in the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 ("ITAA36") so require clarification and guidance from the courts. In this regard, Waincymer wrote:

The law is voluminous ... [and] has inherent ambiguities. Many of the core concepts are not defined and have been left to the Courts to develop. Some are virtually indeterminate. Many have no justification in policy terms. There are many disputes.[9]

The Australian taxation dispute resolution system has changed little since the introduction of the Boards of Review in 1922.[10] Whilst the Administrative Appeals Tribunal ("AAT" or "the Tribunal") replaced the Boards in 1986, the dispute resolution system was "created when the world was very different from the current environment"[11] and many of the practices of procedures are still the product of a past age and past technologies which are no longer as effective or relevant in the considerably changed external environment. As a result, there is criticism[12] that the taxation dispute resolution system needs to better reflect changes in the tax environment such as self-assessment and electronic commerce both locally and internationally. Further, the legislation and the subject matter is now complex and commercial circumstances vary considerably so tax has to be sophisticated whilst the resolution system has to provide more guidance and interpretation for the resulting new and complex legislation and the increased use of discretions. For example, the Ralph Report, admittedly considering the business viewpoint, stated that tax administration should be more responsive to business circumstances particularly in the resolution of disputes on technical matters. As a result, this article considers various options to address the perceived problems with the Australian taxation dispute resolution system. The article concludes with an analysis of these options together with an indication of the costs.

To consider how the Australian taxation dispute resolution system could be improved, this article looks at the taxation dispute resolution systems in Canada, New Zealand ("NZ"), the United Kingdom ("UK") and the United States ("US") to consider if they may suggest any useful changes to the Australian system. These countries were selected as they have a common legal heritage based on the common law together with a similar culture, are at a similar stage of industrial and economic development whilst having historical connections, close economic relationships and Anglo-American traditions which, in the accounting context at least, are motivating factors in determining the applicability of approaches in these countries to the Australian situation.[13] Further, Australian, Canadian and NZ law, as well as the legal and government systems, have evolved from that of the UK with British cases providing many precedents.[14] The US system is of particular interest as it is a more sophisticated system that is geared to a larger population and the problems of a mass decision-making environment and thus something from which Australia may learn. For these reasons, the taxation dispute resolution systems and experiences of these countries may provide some insights, solutions and ideas for adoption in Australia.

As illustrated in Table 1 (below), the income tax dispute resolution systems operating in the selected countries are similar in that dissatisfied taxpayers generally have to deal first with the Revenue authority[15] in an internal review or negotiation stage and then, if still dissatisfied, may seek external administrative or judicial review. The OECD reports that, in general, the majority of disputes are resolved at the internal review level with only those cases requiring legal interpretation reaching the courts.[16]

A further point of interest is that, in all jurisdictions except the UK, there is provision for a small tax claims procedure from which there is generally no appeal and the decisions do not create a precedent.

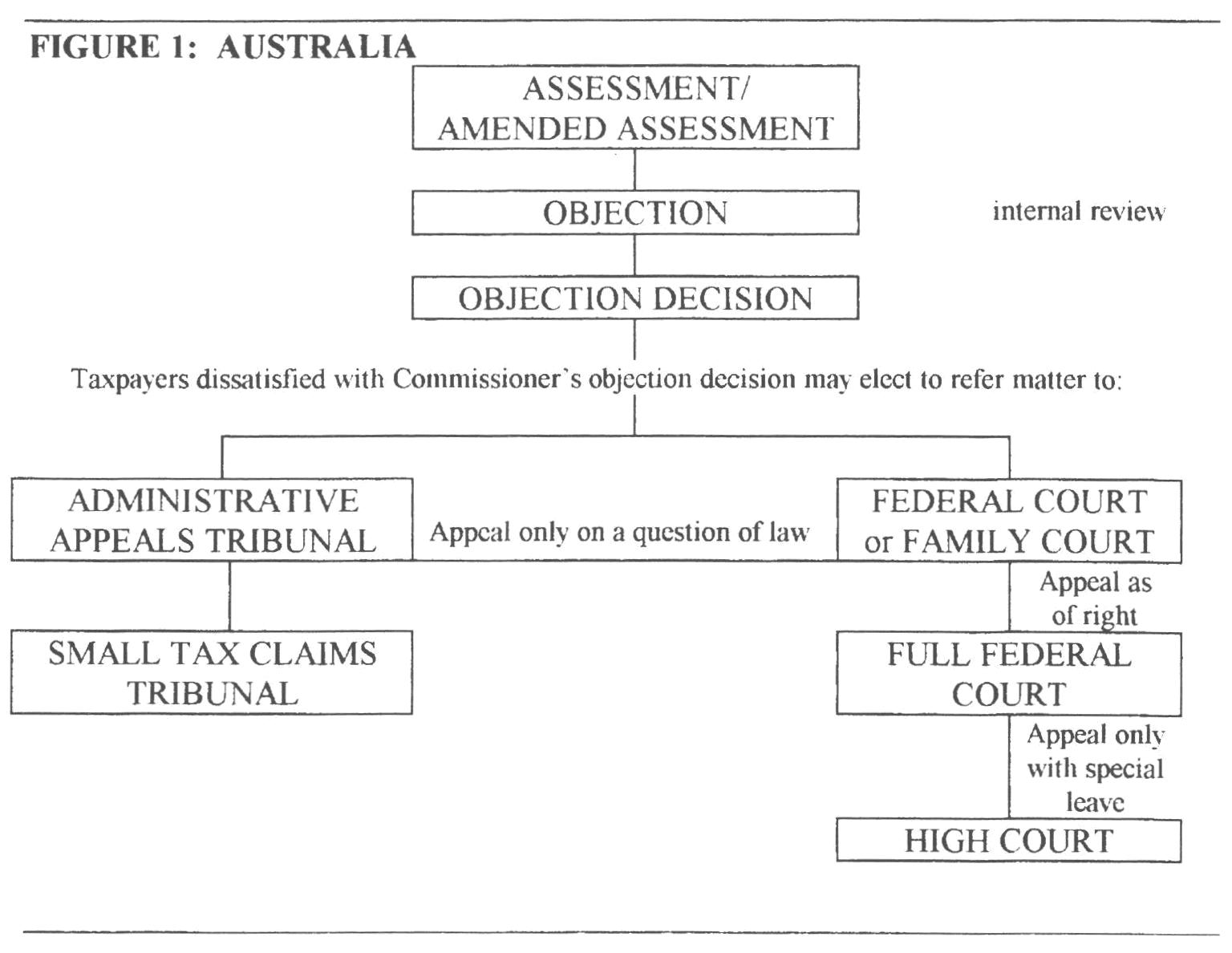

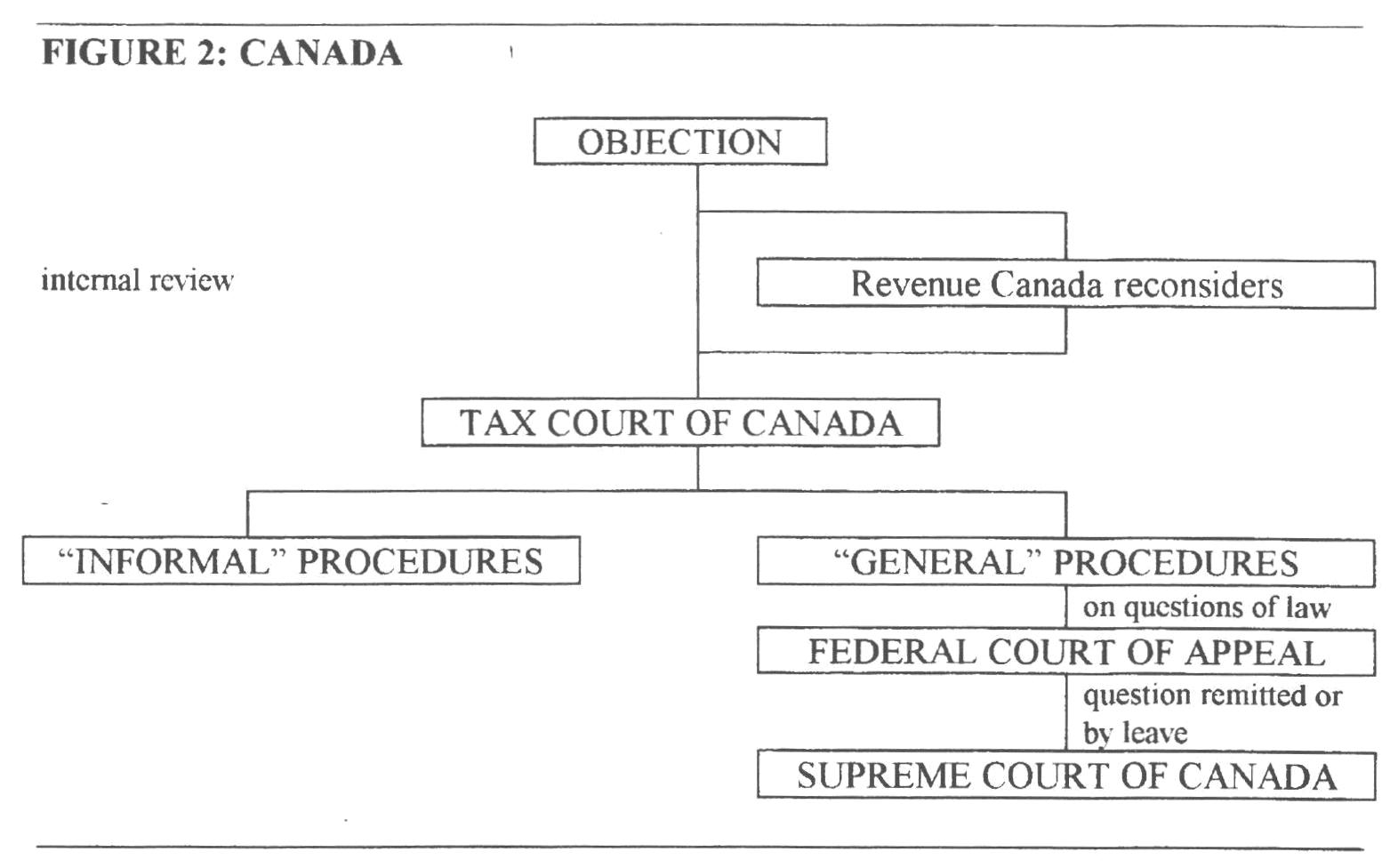

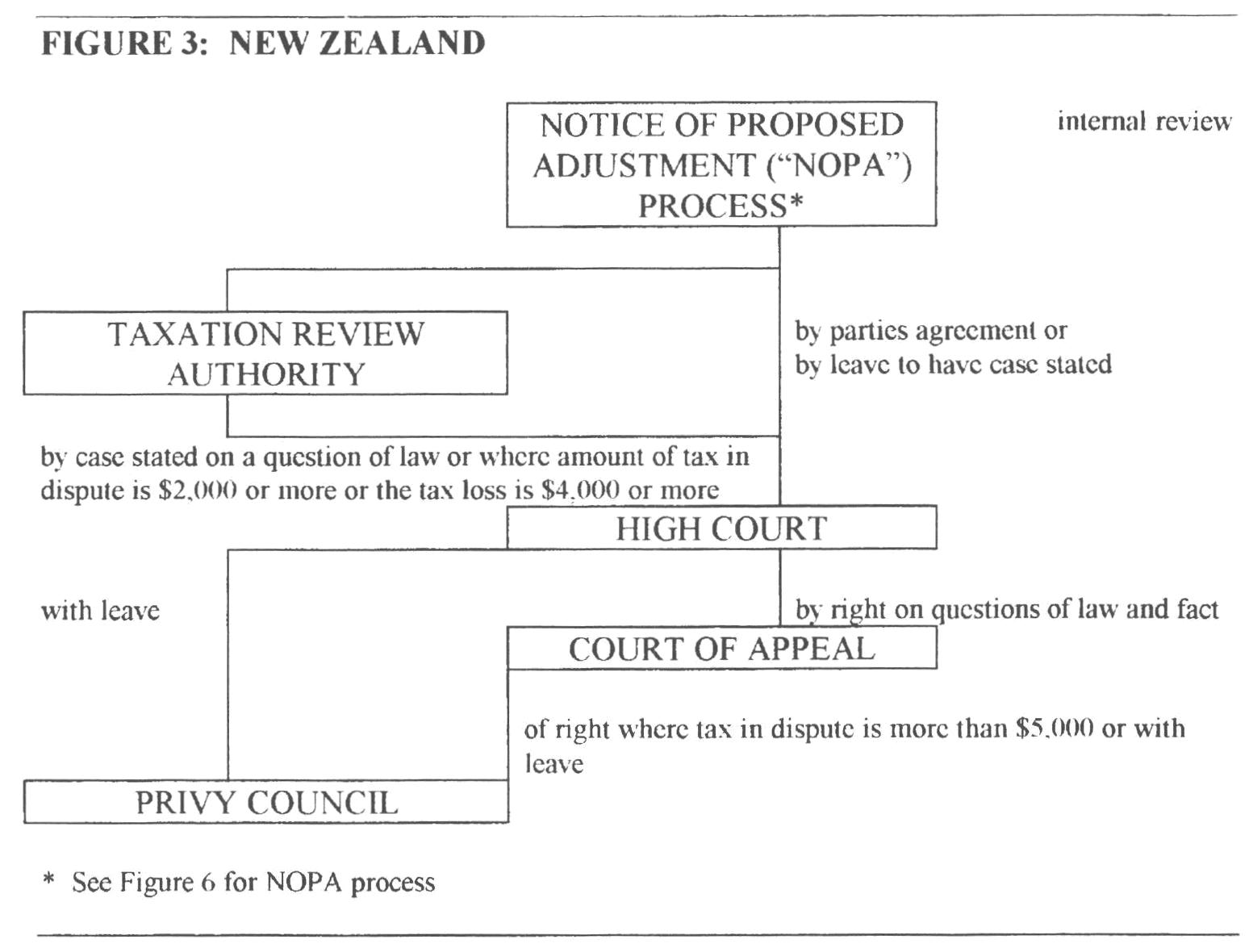

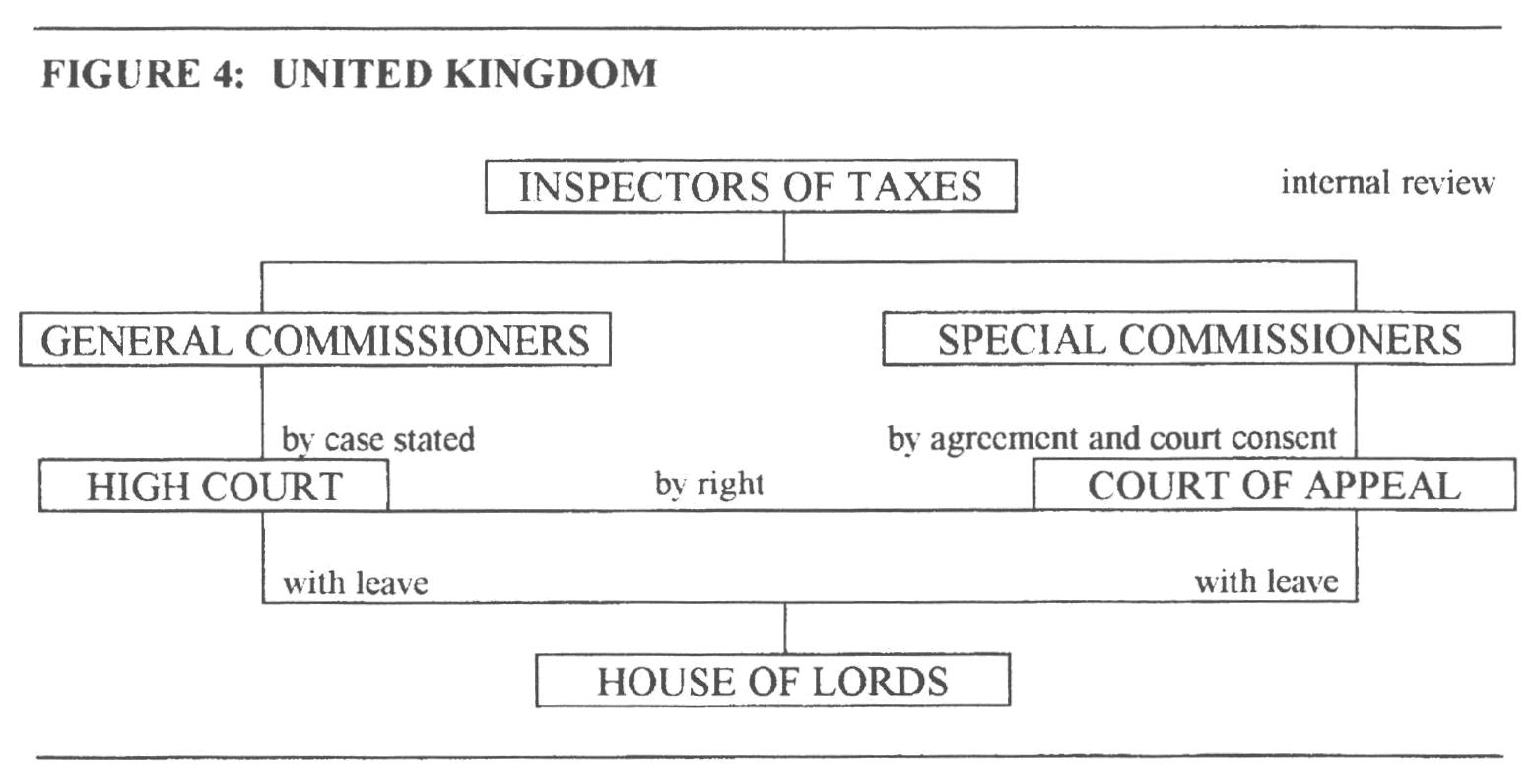

Figures 1-5 (below) illustrate the progression of a dispute through the various taxation dispute resolution systems. From these, it can be seen that the UK system is considerably different from both the Australian system and the systems in other countries and prima facie, for this reason, it would seem to offer little in the way of useful strategies that could be easily incorporated into the Australian system. However, from examination of the other various taxation dispute resolution systems and criticisms of the Australian system, there are initiatives that could be useful in Australia. These are in the areas of internal review, a separate Tax Court, stricter time standards to expedite cases, codification of tribunal procedures, the "regular" and "memorandum" decisions of the US Tax Court, the "acquiescence" policy of the US revenue authority, and the issue of costs.

|

TABLE 1: GENERAL TAXATION REVIEW AND APPEALS STRUCTURE

|

|||||

|

Country

|

AUSTRALIA

|

CANADA

|

NEW ZEALAND

|

UNITED KINGDOM

|

UNITED STATES[a]

|

|

Right of Objection against assessment

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

|

Time to lodge objection

|

4 years or 60 days (amended)

|

1 year or 90 days (amended)

|

4 years or 2 months (amended)

|

30 days

|

30 days (60 days for non-residents)

|

|

Objection must first be made to administrative authority

|

Yes

|

Usually unless Minister waives this

|

Negotiations before amended assessment

|

Yes

|

No but ability to recover costs is harmed by not doing so

|

|

Taxpayer can appeal for external review/appeal to a higher body/court

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

|

Appeal generally resolved at internal review

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

|

Time to request external review

|

60 days

|

90 days

|

2 months

|

30 days

|

90 days (150 days for non-residents)

|

|

Time to request further appeal

|

28 days

|

30 days

|

30 days

|

30 days

|

90 days (150 days for non-residents)

|

|

Bodies which can hear appeals

|

Administrative Appeals Tribunal, Federal Court, High Court

|

Tax Court, Federal Court of Appeal, Supreme Court

|

Tax Review Authority, High Court, Court of Appeal, Privy Council

|

General/Special Commissioners High Court, Court of Appeal, House of

Lords

|

Tax Court, Claims Court, District Court, Court of Appeals, Supreme

Court

|

|

Procedures (other than courts)

|

At Tribunal's discretion, ARC may advise

|

Procedures Acts in Ontario and Alberta only

|

Broad guidelines similar to UK but no supervision

|

Council on Tribunals and Inquiries Act; Model Rules of Procedure for

Tribunals 1991

|

Administrative Procedures Act 1946; Judicial Improvements Act 1990

|

|

Special small claims procedures

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

No

|

Yes

|

|

Members of Tax Court/Tribunal/UK Commissioners are appointed by:

|

Governor-General and have tax experience

|

Government

|

Government and are judges

|

Government and are laymen and tax experts

|

Courts presided over by judges

|

|

Representation in: Tax Court/Tribunal

|

Optional

|

Taxpayer

|

Taxpayer or lawyer

|

Taxpayer or accountant

|

Taxpayer or lawyer[b]

|

|

Regular courts

|

Lawyers

|

Lawyers

|

Lawyers

|

Lawyers

|

Lawyers

|

|

Private/public hearings:

Tax Court/Tribunal

|

Public[c]

|

Public

|

Privacy retained

|

Privacy retained

|

Private[b]

|

|

Regular courts

Onus of proof

|

Public On taxpayer

|

Public On taxpayer unless facts in Notice of Appeal deemed to be true

|

Public On taxpayer

|

Public On taxpayer unless revenue alleging fraud which revenue has to

establish

|

Public On taxpayer unless revenue alleging fraud or revenue raises any new

issues after Notice of Deficiency

|

SOURCE: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Survey on Taxpayers' Rights and Obligations 1990 supplemented by the relevant CCH Master Tax Guides

The objectives of the internal review process are to quickly and cheaply satisfy the concerns of a significant proportion of taxpayers whilst at the same time improving the quality of agency decision-making.[17] In Australia, the internal review process, whilst cheap, has come under increasing criticism as being largely ineffective and not meeting these objectives.[18] Part of the criticism of internal review stems from the failure to modify it for the self-assessment environment. In a self-assessment system, disputes are only likely to occur in three circumstances:

1. after an audit where an amended assessment was issued;

2. after the Commissioner issued a s 170 amended assessment due to matching activities or a s 167 default assessment or assets betterment assessment; or

3. where a taxpayer lodges a return and/or assesses according to a private ruling to avoid penalties but objects to the return rather than the ruling itself given the problems of objecting to the ruling.[19]

Because the issues and problems are different with an audit and the other two situations, these are now considered separately.

The Ralph Review found that, as in other jurisdictions with self-assessment, disputes principally arise through an audit.[20] The Ralph Review also points out that assessments can have significant effects on taxpayers so every opportunity should be taken to get it right.[21] For example, listed companies have to advise the Stock Exchange if an assessment is material and this may adversely affect its share price. Similarly, private companies may find an amended assessment may cause lenders to call in loans or securities. Thus, it is vital that amended assessments are issued in good faith, especially when there is no suggestion of any avoidance scheme.

In particular, the effectiveness of internal review is undermined by the absence of any obligation for the Commissioner to provide detailed reasons for an assessment or the objection decision together with the poor communication of such reasons. This is evidenced by taxpayers making "omnibus" objections to cover every eventuality rather than being able to focus the objection.[22] It is also "important that the reasons for decisions are clearly explained to applicants"[23] so that the issues are well defined at internal review. Otherwise, communication between the parties may be lacking in focus and possibly even counter-productive which may contribute to delay as preliminary procedures and hearings will need to define the issues, something which is both inefficient and a duplication of effort. Another consequence may be that taxpayers may not wish to object or proceed to external review if they have and understand the reasons but do not know this in good time. The ARC Report evidenced this:

It is an unacceptable "Catch 22" situation that the reasons which are necessary in order to determine whether an application for external review will be justified cannot be obtained until after the making of the application.[24]

This problem is exacerbated by a lack of personal contact during internal review.[25]

A further problem is the lack of independence between the review officer and the primary decision-maker together with a general adherence to internal policies by internal review staff.[26] On the independent issue, ARC Report 39 states that internal review should be undertaken by officers "sufficiently independent of the agency decision-makers" so that there is a genuinely fresh reconsideration of decisions and an enhancement of the normative effective of internal review.[27]

From these criticisms, it can be seen that the internal review process is not seen to be a meaningful process that performs the necessary filtering role before external review.[28] As a result of its investigation into the internal review process, the Ralph Review has recommended that a revised process following an audit that "would not restrict opportunities for negotiation and settlement" should be put in place to better allow parties to focus on the issues and amounts in dispute before the amended assessment.[29] This should allow more consideration of the issues, reduce cases of multiple amended assessments where issues are complex and time constraints on amendment require urgent action,[30] and also permit more negotiation before litigation is contemplated. However, the ARC considers that a comprehensive and lengthy internal review is "not the most desirable mode of review" and that the major focus should be to ensure that an applicant's access to external review is not prejudiced.[31]

The Canadian, US, NZ procedures after an audit address these issues and may offer a viable alternative for Australia. In Canada, the taxpayer meets with Revenue Canada officials so additional facts can be presented and the matter discussed to clarify the issues so that all relevant particulars and issues are canvassed face-to-face at an early stage and any misunderstandings are resolved.

In the US, the IRS has instituted a systematic and decentralised "Deficiency Notice" system which inserts a review mechanism between the official determination of an audit by the IRS and issuing of an amended assessment. This system allows discussions and exchange of information between the parties in order to ascertain and discuss the facts and issues to promote negotiated settlements in order to avert disputes prior to litigation.[32] In addition, the US Taxpayers Bill of Rights has recently been amended to ensure the review mechanism within the IRS is more independent, identifying taxpayers rights during audits and where erroneous advice has been given, and detailing IRS obligations in communications with taxpayers. Taxpayers also have the right to sue the IRS for $1 million for reckless collection whilst the IRS must also report employee misconduct to Congress.[33]

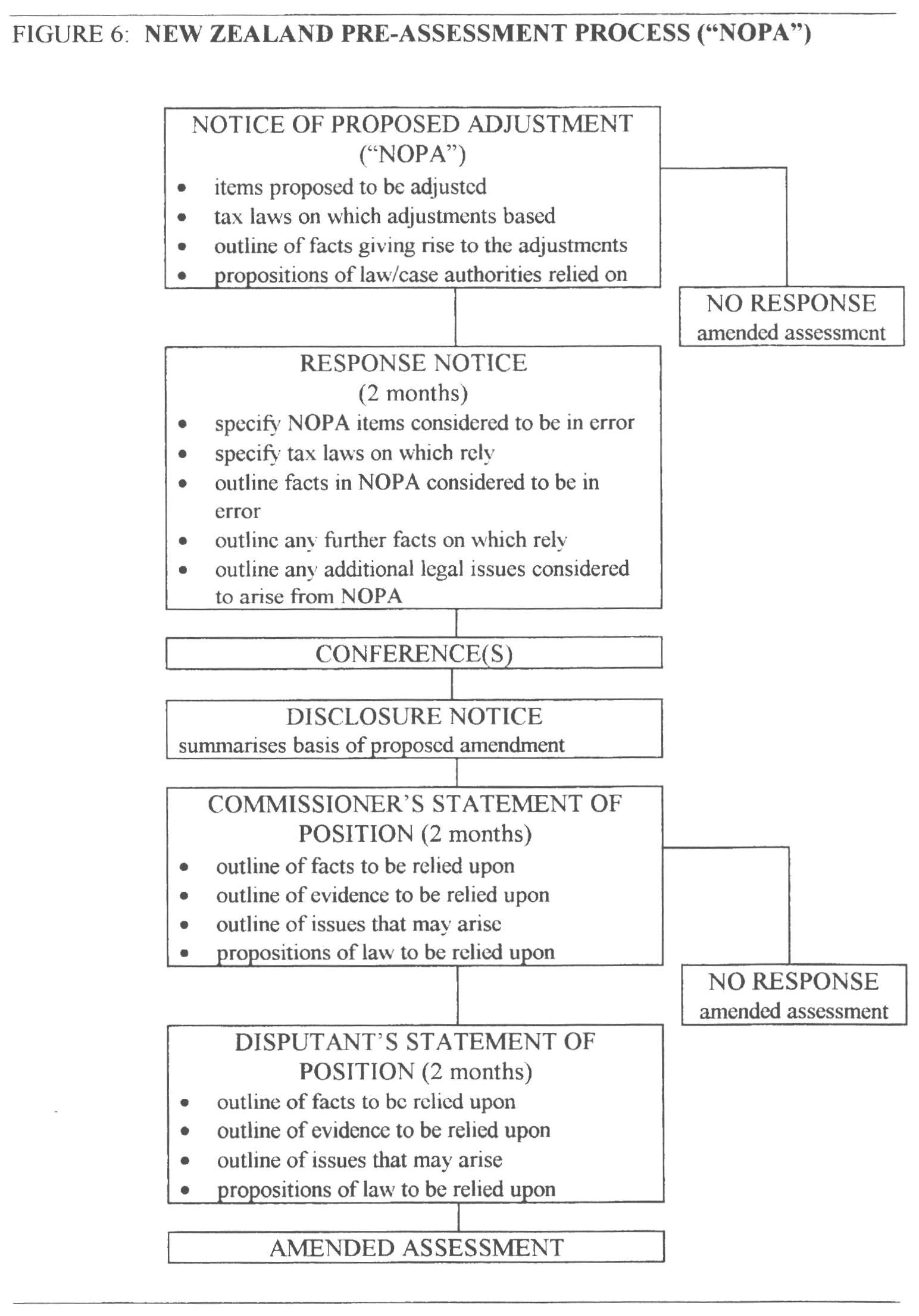

The US system is similar to but less detailed and formalised than the NZ notice of proposed adjustment ("NOPA") pre-assessment process shown in Figure 6 (below).[34] This NZ process was introduced in April 1996 to reflect self-assessment and the fact that most disputes originated in the audit process. As can be seen from Figure 6, the Commissioner of Taxation issues a NOPA with details as shown. The taxpayer then has two months in which to respond in similar terms to this notice. If there is no reply, an amended assessment is issued in accordance with the NOPA. This part of the process is intended to identify the issues the Commissioner considers require adjustment, elicit a response from the taxpayer and prepare the ground for the conference phase. One or more conferences will follow, either formally in person or by telephone or letter. This is aimed at the mutual disclosure of relevant information. During the conference stage, the Commissioner may issue a disclosure notice which summarises the basis on which the Commissioner intends to assess the taxpayer. Within two months of the disclosure notice, the Commissioner must also provide the taxpayer with a statement of position as shown in Figure 6. The taxpayer then has two months to provide a similar statement and if there is no response from the taxpayer, an amended assessment is issued as per the Commissioner's statement. After the taxpayer's Statement of Position, an amended assessment is issued. These negotiations are overseen by an adjudicator who is separate from the audit investigation and final quantification of tax liability with the objective of providing an impartial application of tax law and greater technical expertise to the affairs of individual taxpayers prior to the issue of an amended assessment. If the taxpayer is still dissatisfied with the amended assessment, the taxpayer then can apply directly for external review.

In conjunction with this pre-assessment process is the "evidence exclusion rule". This operates to exclude from use in further disputation any not previously disclosed "evidence or facts" or "propositions of law or issues".[35] This is intended to provide an appropriate incentive for disclosure of the factual basis for the arguments of the taxpayer and the Commissioner in the pre-amended assessment phase. As a result, the Tax Review Authority ("TRA") is confined to answering issues raised by the Commissioner's decision and does not undertake a wide-ranging review of the taxpayer's affairs. However, there is some flexibility in that, on application of either party, the court may allow the raising of new facts, evidence, issues and new propositions of law if they could not have done this previously or the weight of the new matters is such that they will necessarily be conclusive if admitted.[36] As such, this rule is a vital component in ensuring that the pre-assessment process is a genuine re-assessment of the taxpayer's position with all the facts and issues understood and canvassed.

Of particular interest in both the NZ and US processes is the constant opportunity for the exchange of views and refining of issues so that the entire process is more efficient and effective. In particular, face-to-face discussions between the parties prior to an amended assessment is obviously cheaper, quicker and less traumatic and may allow disputes to be settled at the earliest possible stage. Further, no liability is created until the process is complete and the amended assessment is issued. This also means that the external review function is reserved for matters where the law is uncertain. As such, whilst it is acknowledged that there are some informal processes in Australia such as position papers in large audits, it would be preferable to have a more formal and exhaustive process as in NZ or the US rather than the present internal review processes.

Various commentators have also questioned whether internal review is necessary at all in a self-assessment system.[37] The Ralph Review stated that the internal review objection process as it now operates is now of little value and often only "serves to delay the appeal process (and sometimes the collection process)".[38] Further, taxpayers should be able to immediately access external review after an audit or ruling as, if the ATO has determined its default assessment or ruling position carefully, it "should not need a second chance to get it right"[39] and, furthermore, often there is little or no likelihood of the ATO changing its decision.

In the US, as shown in Table 1 and Figure 5, internal review is optional but the ability to recover costs may be impaired if this is avoided. The Canadian system, as shown in Figure 2, allows taxpayers, if the Minister consents, to waive the internal review process and appeal directly to the Tax Court. In this case, Revenue Canada is deemed to have confirmed the assessment which relates to the objection. This option is only used if it is perceived that Revenue Canada's position is inflexible and internal review would only delay the process.

From Figures 1 to 5 inclusive, it can be seen that the major difference between the Australian system and the other systems is that there is a separate Tax Court in Canada, New Zealand (the Taxation Review Authority "TRA") and the United States. The question of a separate Tax Court has not really been canvassed in Australia although the Ralph Review has called for the current system to be reviewed to ensure that there is "an appropriate body of tax expertise on appeal".[40] The major argument for a specialist Tax Court is that the complexity of the legislation and the business environment requires expertise and specialisation. This has been shown by the various problems encountered with conflicting decisions of differently constituted courts or decisions that seem to leave doubt.[41] Further, with specialist judges, the hearing is more likely to be more efficient due to judges requiring less "education" in the area by the parties. Finally, whilst the Taxation Division of the Tribunal (which has specialist tax expertise) is functioning reasonably efficiently and effectively, the Tribunal is not a court and its decisions are not authoritative or binding on the Commissioner and do not set a precedent to be followed. As a result, cases for clarification of the law in the Test Case Litigation Program go to the Federal Court which does not have the specialist tax expertise.

On the other hand, Hill J[42] dismisses the need for a separate Tax Court as he sees value in judges having other general expertise as matters pertaining to general law arise as well as tax law. In particular, the ITAA36 is written in general rather than specific terms which requires the courts to determine their meanings under ordinary legal concepts which is not divorced from the legal and business environment. Also, the High Court does not have specialist judges to hear the various cases that come before it. Hill J also refers to problems with specialist courts in Australia citing in particular the problems with Mr Justice Staples and the Industrial Relations Court. Another problem with this proposal is that courts can only decide whether a decision has been made according to law[43] rather than whether it is the best decision[44] and the latter is what is required when considering a discretion.

However, with respect, these are not sufficient reasons for not having a specialist Tax Court. After all, despite the discontent with the Family Court, it is recognised that this is a specialised area requiring different expertise, procedures and solutions so, given the complexity of tax legislation, why should a generalist court decide tax matters?[45] As such, consideration should be given to the establishment of a specialist Tax Court similar to those in Canada, New Zealand and the United States so that the complexities and ambiguities of tax can be better addressed. If a separate Tax Court were seen as too costly an option due to the relatively small number of cases being heard, an alternative to this would be to create a specialist Taxation Division within the Federal Court similar to that in the Tribunal. This Division would require judges, such as Hill J, appointed for their tax expertise so that, when sitting alone, there would be a tax specialist judge whilst, for a Full Court, the tax specialist judge would be the presiding member.

If either of these proposals were adopted, this would also necessitate reconsideration of the entire system and the role of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal, the Federal Court and the High Court in the system.

Time standards, by placing pressures on the parties to address the issues, may result in earlier resolution of disputes either through settlement or an earlier hearing. For example, ARC Report 39 stated that internal review should be completed within 28 days but reported anecdotal evidence suggesting that the ATO does not meet this standard.[46] Whilst s 14ZYA of the Taxation Administration Act 1953 does allow the taxpayer to request the ATO to determine the objection within 60 days, this remedy is "only barely adequate as the time limit does not begin to run unless the taxpayer makes a specific request"[47] and, should the ATO require further information, the time limit has to start again. In contrast, in Canada, if the objection decision is not made within 90 days, then the taxpayer may proceed to external review without waiting for Revenue Canada to make a decision.

Similarly, the Australian Tribunal through the General Practice Directions (and to a lesser extent the Federal Court) sets informal target time standards for various stages in the disputation process but, as the Annual Reports show, these standards are not met and there is no sanction on the parties to adhere to them. However, in Canada, to ensure a speedy hearing in the Tax Court, at all stages there are rigorous time limits imposed on the Crown, the Court Registrar and the Judge with severe penalties for enforcement so that the entire process should take approximately seven months.[48]

As such, it is suggested that strict time limits be introduced in Australia into all stages of the objection and appeal process with more effective sanctions to ensure compliance and ensure the speedy resolution of disputes. For example, as in Canada a taxpayer could proceed to external review if the Commissioner did not decide the objection within the prescribed time. A more severe sanction might be to allow the objection or appeal to be upheld. Similarly, the matter could be dismissed if a taxpayer is dilatory. However, there should be the flexibility whereby either party could avoid these sanctions by justifying the delay.

In Australia, Tribunal procedures are at the Tribunal's discretion[49] and may be changed in response to circumstances. Whilst the ARC does not routinely monitor procedural developments and has no power to impose standards, it relies on the persuasiveness of its advice on procedures.[50] However, the US has an Administrative Procedure Act 1946 ("APA") which provides a common code of procedure to ensure consistency and equity between tribunals and to ensure that minimum procedural standards apply. A possible problem with a code of procedure is that it may increase formality and adversarialism whilst procedures may not be flexible enough to adapt quickly to changing circumstances. However, the APA is said to have "the flexibility to expand to the ever changing complexion of the administrative state".[51] Further, the US Judicial Review Improvements Act 1990 has entrenched the philosophy "justice denied is justice delayed" in legislation by requiring both quick and speedy resolution as well as substantive justice. As a result, before any procedure is added or changed, US courts must consider whether the resultant marginal improvement in fact-finding accuracy would be more than offset by any increased agency costs whilst also considering the likely magnitude of individual hardship resulting from an error in the decision process.[52]

In Canada, procedures are codified only in Ontario and Alberta. Otherwise, there is no procedural code although the Charter of Rights and Freedoms has an impact on the implication of administrative review rights before tribunals. In the UK, the Council on Tribunals oversees the system and must be consulted about initial procedures of any tribunal and has produced "Model Rules of Procedure for Tribunals" providing general principles. Similar to the UK, NZ has procedural guidelines but the significant difference is that there is no body scrutinising proposed procedures. This is seen to detract from the effectiveness of the machinery for procedural review.[53]

As a result of looking at the different ways of ensuring adequate Tribunal procedures, it is suggested that consideration be given to a more formal Administrative Procedures Act as in the US together with a Judicial Review Improvements Act based on the US Act to ensure some minimum procedures apply and there is also some consistency between hearings to enhance perceptions of fairness.[54] These should take into account both quick and speedy dispute resolution as well as substantive justice.

The US Tax Court issues two types of decisions. Generally, the first time the Tax Court decides a particular legal issue the decision appears as a "regular" decision whilst cases dealing with some factual variation on a matter for which the interpretation of the law was decided in an earlier case are issued as "memorandum" or "memo" decisions. This readily distinguishes between original and later cases in an area of law. Whilst Australia does have an effective court reporting system, this may be a useful addition to the Australian system in the spirit of being more user-friendly similar to the Tax Law Improvement Project. The major argument against this approach would be that objective, experienced and empirically aware commentators who take a broad range of matters into consideration when reporting on a case may be better placed than judges to categorise cases in this manner.

US Tax Court cases decided in favour of a taxpayer might be the subject of the IRS "acquiescence policy" whereby the IRS announces whether it agreed ("acquiescence") or disagreed ("non-acquiescence") with a decision that is adverse to the Revenue. This has important implications for a taxpayer. If the IRS has "non-acquiesced" to a particular case and a taxpayer in similar circumstances relies on that case then, in the event of an audit, the IRS will not follow the case and litigation may result. However, if the IRS has "acquiesced" to a decision, the implication is that there will be no opposition to a taxpayer's position on the issue. However, a decision of the Supreme Court has the force of law and is binding on the IRS, taxpayers and other courts. Thus, the IRS cannot "non-acquiesce" a Supreme Court decision. This system is more formal than the Australian system where the Commissioner may issue a ruling on important cases but those take some time to issue and do not cover all cases.[55]

An alternative approach would be for the ATO to advise the Ombudsman of its intended approach together with reasons for this and the Ombudsman then investigate, report and recommend whether an appropriate "test case" be undertaken on the matter. Yet another alternative would be to make all court decisions binding on the Commissioner but this could cause problems in the event of conflicting court decisions. Overall, the "acquiescence policy" would seem to be the more efficient and timely approach as it clarifies the Commissioner's approach to all cases.

Costs are a problem throughout the legal system and can be a barrier to access. Of particular interest are the costs to access the Tribunal and the courts, the costs of professional assistance and legal representation, and the fact that tax in dispute has to be paid prior to resolution of the dispute which may take some considerable time.[56]

With regard to court and Tribunal fees, where the amount of tax in dispute is small, Australian taxpayers can go to the Small Tax Claims Tribunal for a non-refundable fee of only $51. For larger amounts in dispute or taxpayers wanting a more authoritative decision, there is a choice of two comprehensive but very costly options being the Tribunal and the Federal Court. For example, any taxpayer who may wish to go through the entire process from the Tribunal (because of the lower costs of establishing the facts and also the ability to address a discretion), to a single judge of the Federal Court, then the Full Federal Court and finally, with special leave, to the High Court, the fees for these forums alone could approach $10,000.[57]

However, these fees are, in most cases "only a very small fraction of the total cost of litigation".[58] It is the cost of professional advice and assistance, principally legal representation, together with other costs (such as transcript fees) that is the greatest deterrent. It has been reported that the legal costs of a typical Tribunal case resolved at a preliminary conference is $500, that proceeding to a simple hearing costs between $1,500 and $1,800, and a complex case costs between $30,000 and $50,000 which is comparable to the cost of a Federal Court case.[59]

Such costs put external review out of the reach of most taxpayers and make it uneconomic and impractical for most cases. However, the complexity of the legislation means that even at the Tribunal, professional assistance is often necessary whilst taxpayers not using representation are seen to be at a distinct disadvantage apropos the experienced ATO representatives. As such, in 1996, taxpayers were represented in 66 of the 76 Tribunal reported cases.

Whilst taxpayers may be awarded costs if they are successful in court cases (although this is not their entire costs) and similar costs are paid by the revenue for test cases and usually where the Commissioner appeals against an adverse decision, costs are generally not awarded at Tribunal level although recent legislation allows the Tribunal to award costs against a party who has wasted costs of the other party.[60] In contrast, in NZ, the TRA can suggest an ex-gratia payment to taxpayers for their costs and this would be appropriate in the Australian Tribunal.

There are two other related changes which may be useful in the Australian system. In the US, there is no payment of the tax in dispute if going to the Tax Court so this alleviates the problem where such payment can cause cash flow problems particularly for small business. Whilst this could lead to frivolous and vexatious cases or cases being brought merely as a delaying tactic, in the US, Canada and NZ costs can be awarded in such cases.[61] This can be contrasted with Australia where the Tribunal can dismiss such cases but cannot apply any other penalty.[62] As such, it is recommended that Australian legislation be amended to allow the deferral of payment of tax for cases going to the Tribunal (or a Tax Court if introduced) whilst allowing for costs to be awarded against taxpayers in frivolous or vexatious cases to deter taxpayers who wish to delay assessment.

From the foregoing, it can be seen that, whilst the taxation dispute resolution systems in Australia, Canada, NZ, the UK and the US have many similarities, there are some material differences that may be adapted for the Australian environment. These can be put into two categories, those that would have virtually no cost and those that would involve some cost as shown in Table 2 below.

From this table, looking firstly at the less costly initiatives, it can be seen that it is considered that the introduction of the NOPA process rather than internal review is considered to have virtually no cost as, whilst the process is quite exhaustive, the issues are clearly canvassed and, as a result, should lead to less potential external review and a more efficient external review process. Similarly, direct access to external review to dispute rulings and default assessments would reduce costs as the internal review process would be eliminated. The introduction of a US style "regular" and "memorandum" decision process to identify original and later decisions in an area should not involve additional costs as this would be incorporated in the court decisions and, in fact, may make these more succinct and clearer as there would be less duplication of effort in these decisions. Similarly, the introduction of formal time standards should not involve additional costs as they would merely speed up the process. Also, awarding costs for frivolous or vexatious cases will advantage the revenue whilst also possibly promoting more efficiency in the system.

|

TABLE 2: COST IMPLICATIONS OF SUGGESTED CHANGES

|

|

Virtually costless/reduces costs

NOPA process/Evidence Exclusion Rule (NZ)

|

|

• direct access to external review to dispute rulings or default

assessments (Canada and US)

• "regular" and "memorandum" court decisions (US)

• formal time standards (Canada)

• awarding costs or imposing penalties for frivolous or vexatious

cases (US, Canada and NZ)

|

|

Some costs

|

|

• separate Tax Court or a separate Tax Division of the Federal Court

(NZ, US and Canada)

• exgratia payments for taxpayers costs in appropriate circumstances

(NZ)

• deferral of all tax in dispute during the Tax Court/Tax Division

process (US)

|

|

Difficult to determine:

|

|

• procedural code for tribunals (US)

• acquiescence policy (US)

|

Suggestions that would involve additional costs include the introduction of a separate Tax Court which could involve considerable administrative costs and the criticism is that there is not sufficient business to keep such a court fully occupied. The cheaper alternative would be the introduction of a separate Taxation Division of the Federal Court. This would involve little additional administrative costs and, if tax judges were involved in other areas of law when there were no tax cases to be heard, overcome the possible inefficiencies of judges not being fully occupied. This would also require a complete reconsideration of the roles of the Tribunal, the Federal Court and the High Court. The proposals to pay taxpayers ex gratia payments for their costs in appropriate circumstances and for tax to be deferred if a taxpayer proceeds to the Tax Court would be costly although the latter would only be a deferral of tax payments, not a permanent loss to the revenue and interest penalties would apply.

With regard to the initiatives regarding a procedural code for tribunals and the "acquiescence" policy to indicate the Commissioner's views on important case decisions, it is difficult to determine whether these will cause additional costs or not as it depends to a large extent on whether these will cause additional work or not. Generally, a procedural code should merely standardise Tribunal procedures without additional costs. It would only add costs if it increased administration and formality and thus cause additional work to be done. As for the "acquiescence" policy, given that the ATO does issue rulings and the like on important cases at present, it may be that making this a more formal requirement may not add costs.

From the foregoing discussion and analysis, it is strongly recommended that the Australian taxation dispute resolution system be changed to incorporate various initiatives used overseas. Specifically, internal review should be replaced by a NOPA-like process or avoided in appropriate circumstances, it should be possible to award costs for frivolous or vexatious cases and there should be either a separate Tax Court or a separate Taxation Division of the Federal Court. Proposals of less obvious benefit that should also be considered include "regular" and "memorandum" court decisions, formal time standards to be adhered to in the course of a dispute, the awarding of ex-gratia payments in appropriate circumstances, the deferral of tax in dispute during the Tax Court process, the introduction of a Tribunal procedural code and an "acquiescence" policy whereby the Commissioner would indicate the revenue attitude to court decisions. The introduction of all or some of these initiatives would, in my opinion, make for a more effective and efficient taxation dispute resolution system in Australia whilst also making it far more user-friendly and appropriate for the tax environment in the new millennium.

Suzette Chapple is an Assistant Lecturer at the University of Western Australia. This article is adapted from her Master of Commerce thesis on the income taxation dispute resolution system and based on a paper presented at the 1999 Australasian Tax Teachers Association Conference.

[1] AGPS, Justice Statement, May 1995, 122.

[2] 1995-96 Budget Papers estimated that income tax was approximately 70% of total Commonwealth revenue collected, up from approximately 60% at the beginning of the 1980s. These are similar figures to those reported in JP Smith, Taxing Popularity: The Story of Taxation in Australia, (1993) Canberra, Federalism Research Centre. Further, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development ("OECD") Survey on Taxpayers' Rights and Obligations (1990) reported that taxation revenue as a % of GDP was rising in all countries with it being 31% in 1988 in Australia compared to 23% in 1965. A further interesting statistic is that in Australia in 1965 taxes on personal income as a percentage of total taxation was 34.4% and this had risen to 41.4% in 1991 (OECD, Working Paper on Taxation (1992)). From an individual taxpayer's viewpoint, for taxpayers on average weekly earnings, in 1954-55 the marginal tax rate was 19% and the average tax rate was 10% and these had risen to 46% and 35% respectively in 1983-84 (Reform of the Australian Tax System Draft White Paper (June 1985)). Further, in 1954-55 only 1% of taxpayers had a marginal tax rate of 46% or more and this had increased to 35% in 1983-84 whilst the top marginal rate began at 18 times average weekly earnings in 1954-55 and only 1.6 times in 1983-84. Due to rising wages and bracket creep, this trend has continued so that income tax is a major issue for both government and taxpayers.

[3] W Gumley, "The Taxation Appeals System: An Administrative Law Perspective", ATAX Tax Administration Conference, 1998.

[4] Hill J, forward to R Woellner, T Vella, L Burns & Chippendale, Australian Taxation Law (1990, 3rd ed).

[5] FC of T v Cooling 90 ATC 4472, 4488 (per Hill J). A further example of the complexity of the ITAA36, as encountered by the Full High Court, is found in its final orders in Hepples v FC of T 92 ATC 4013 ("Hepples") where similar sentiments to Hill J were expressed.

[6] CPH Property Ltd & Ors v FC of T 98 ATC 4983 (per Hill J).

[7] This expression was used both in Joint Committee of Public Accounts Report 326, An Assessment of Tax, November 1993 ("JCPA Report 326"), and by M Leibler, Editorial Revenue Law Journal (1991) 3. The Tax Law Improvement Project ("TLIP") is intended to overcome some of these problems by simplifying and rewriting the ITAA36. The House of Representatives Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs, September 1993, in the report Clearer Commonwealth Law, para 8.75 also reported community concern as to the complexity of the ITAA36. This report (para 10.44) perceived this as being partly a result of the increasing volume of legislation leading to less Parliamentary scrutiny of bills.

[8] This is referred to as the two "outputs" of judicial services in Access to Legal Services: The Role of Market Services, February 1992, AGPS, Canberra.

[9] J Waincymer, Australian Income Tax Principles and Policy (1991) 66.

[10] SM Chapple, Aspects of Post-1986 Income Taxation Dispute Resolution in Australia, Master of Commerce Thesis, The University of Western Australia, 1997.

[11] Review of Business Taxation, A Strong Foundation, para 8.13 ("Ralph Review"). Gumley, above n 3, also reports that "objection and appeal rights of taxpayers have remained substantially the same since the Federal income tax was first introduced in 1915".

[12] For example, Ralph Review, above n 11; Gumley, above n 3; Administrative Review Council Report No 39 (1995), Better Decisions: Review of Commonwealth Merits Review Tribunals ("ARC Report 39"); and to a lesser extent JCPA Report 326, above n 7.

[13] WG Frank, "An Empirical Analysis of International Accounting Principles" (1979) Journal of Accounting Research 593; SA Zeff, Forging Accounting Principles in New Zealand (1970); RD Nair and WG Frank "The Impact of Disclosure and Measurement Practices on International Accounting Classifications", (1980) Accounting Review 426; CW Nobes "Classifications of Financial Reporting Practices" (1987) Advances in International Accounting.

[14] However, in Liedig v FC of T 94 ATC 4269, Hill J held that the various New Zealand and UK cases were inconsistent with Australian High Court decisions and they did not correctly state the law in Australia.

[15] Australian Taxation Office ("ATO") in Australia; Revenue Canada in Canada; Internal Revenue Department ("IRD") in New Zealand; Inland Revenue Commissioners ("IRC") in the United Kingdom; and the Internal Revenue Service ("IRS") in the United States.

[16] OECD, above n 2.

[17] ARC Report 39, above n 12, para 6.43.

[18] Ibid para 6.54.

[19] See eg, CTC Resources NL v FC of T 94 ATC 4072.

[20] Ralph Review, above n 11, para 8.7. Both NZ and the US similarly found that disputes mainly arose through an audit in the self-assessment process.

[21] Ralph Review, above n 11, para 8.8.

[22] Gumley, above n 3. ARC Report 39, above n 12, para 6.65 also notes that it is "important that the reasons for decisions are clearly explained to applicants" so that the issues are well defined at internal review.

[23] ARC Report 39, above n 12, para 6.65.

[24] Ibid.

[25] ARC Report 39, above n 12, stated that there should be personal contact between the ATO and taxpayers in internal review on the grounds of natural justice as well as the grounds of efficiency and effectiveness.

[26] JCPA Report 326, above n 7, 325 reported that internal review is not independent of the original decision-maker as all ATO staff are "subject to the same culture, corporate goals and values...(and are) culturally bound to determine the matter in favour of the ATO".

[27] ARC Report 39, above n 12, Recommendation 75.

[28] As evidence of this, the Tax Division of the Tribunal has the highest percentage of applications settled without a hearing with most of these being settled in favour of the revenue. This suggests that taxpayers were either irrational or acted without sufficient knowledge of the revenue's case. O'Connor J, President of the Tribunal, suggests that this is an indication that the filtering function expected of the internal review process is not working effectively.

[29] Ralph Review, above n 11, para 8.9.

[30] As in Stokes v FC of T 96 ATC 4393.

[31] ARC Report 39, above n 12, para 6.67.

[32] Litigation is seen as a breakdown in administrative procedures. See Y Grbich, Institutional Renewal in the Australian Tax System, Faculty of Law, Monash University, Melbourne, 1984. JCPA Report 326, above n 7, para 11.125 mentioned this deficiency notice system with approval.

[33] News Section, "US Taxpayers get more Muscle" (1996) 67(8) Charter 14.

[34] The details of this have been gleaned from W Cole, "New Procedures for Resolving Tax Disputes in New Zealand", Australasian Tax Teachers Association Conference, 1996.

[35] This is not unlike the exclusion of evidence if not provided under an offshore information notice under s 264A(10).

[36] As yet, this discretion has not been tested in the TRA or courts but is thought to be very limited. (Cole, above n 34) s 264(10) allows the Commissioner discretion to allow such evidence to be brought.

[37] Such as the Ralph Review, above n 11, and Gumley, above n 3.

[38] Ralph Review, above n 11, paras 8.15, 8.17 and 8.9.

[39] Ibid para 8.16.

[40] Ibid para 8.22.

[41] Such as Provan v HCL Real Estate Ltd 92 ATC 4644 and Carborundum Realty Pty Ltd v RAIA Archicentre Pty Ltd & Anor 93 ATC 4418; Hepples 92 ATC 4013; David Jones Finance and Investments Pty Ltd & Anor v FC of T 91 ATC 4315.

[42] DG Hill, "Great Expectations: What do We Expect from Judges in Tax Cases?" (1995) Taxation In Australia (Red Edition) 21.

[43] Termed "judicial review".

[44] Termed "on the merits".

[45] It has always seemed incongruous that tax legislation permits tax cases to be transferred from the Federal Court to the Family Court with its very different outlook and specialisation.

[46] ARC Report 39, above n 12, para 6.57.

[47] Gumley, above n 3.

[48] V Krishna, The Fundamentals of Canadian Income Tax (1992, 4th ed), 1263.

[49] Section 33 of the Administrative Appeals Act 1975 ("AATA"). This is despite the Commonwealth Administrative Review Committee Report (Kerr Report), AGPS, Canberra, 1971 recommending minimum procedural standards be set.

[50] ARC Discussion Paper, Review of Commonwealth Merits Review Tribunals, September 1994. As a result, Creyke has commented on the degree of similarity of procedures in Australian tribunals (R Creyke, Administrative Tribunals: Taking Stock, Centre for International and Public Law, Canberra, 1992).

[51] RA Cass and CS Diver, Administrative Law: Cases and Materials (1986) 5-6.

[52] Mathews v Eldridge [1976] USSC 20; 424 US 319 (1976).

[53] In 1991, a Tribunals Procedure Bill was introduced into Parliament but was never passed.

[54] It is not known as this stage whether the procedures in the proposed Administrative Review Tribunal will mirror those in the AAT although it may be expected that they would.

[55] As in Taxation Ruling TR 94/26 which reflects the Commissioner's interpretation of Coles Myer Finance Ltd v FC of T 93 ATC 4214. There are many other rulings that could be similarly cited.

[56] Not only can this cause cash flow problems particularly for small business but also the Ralph Review, above n 11, para 8.8 referred to other adverse consequences to taxpayers of amended assessments which are disputed.

[57] This includes the Tribunal application fee ($505); the filing fee ($1,010 for the Tribunal, $505 for the Full Court), setting down fees ($1,010) and hearing fees (at $404 per day after the first day) for the Federal Court; and the filing ($404 for special leave and $1,010 for the appeal) and hearing fees ($1,515 per day after the first day) for the High Court. It should be noted that the Tribunal application fee ($505) is refundable in full if the decision is in favour of the taxpayer in any way.

[58] Attorney-General's Submission to Senate Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs, Discussion Paper No 6, The Courts and the Conduct of Litigation, March 1992.

[59] Ibid paras 2.32 and 2.36. At the Tax Institute of Australia (WA Branch) Litigation Seminar, November 1996, even higher costs of $10,000-$15,000 for a simple hearing were quoted.

[60] In Saffron and Apsley Investments Pty Ltd v FC of T 91 ATC 4501, the Commissioner was allowed to amend the statement of facts, issues and contentions subject to paying the taxpayer's costs wasted as a result of the amendment. This perhaps was the forerunner to the change in law.

[61] This has also been a problem in the UK. In P de Voil, Tax Appeals (1969) an entire chapter is devoted to this problem. This has been overcome in the UK by cases not being listed or heard.

[62] ATTA, s 42C.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/JlATax/1999/23.html