Journal of Australian Taxation

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Journal of Australian Taxation |

|

EVOLUTION OF DIVIDEND ANTI-STREAMING PROVISIONS

By Rodney Fisher

Among the available policy models for integration of the taxation of corporate income and distributions through dividends, Australia has adopted the imputation system, allowing for partial integration of corporate and shareholder tax on franked dividends.

While shareholders have a preference for shares franked to a particular extent, the legislature has maintained that dividend streaming, so as to meet shareholder preferences, is a breach of the fundamental tenets of the imputation regime, and have sought to limit the practice of dividend streaming through a range of sanctions.

This article reviews the measures which seek to impose a sanction on dividend streaming activities, from the measures introduced with the imputation regime through to the more recent specific and general anti-streaming rules.

In conjunction with measures designed to deregulate and internationalise the Australian economy, Australian revenue authorities in 1987 moved from a classical system of taxing dividends to a system of dividend imputation. The classical system involved the taxation of income at the company level, with the further taxation of the distributed income in the hands of shareholders. Under the imputation regime corporate tax paid is imputed to ultimate resident individual shareholders, passing intact through any interposed entities.

The imputation system is a partial integration system, which, while not providing full integration of company and shareholder tax, provides a greater degree of integration than would be available under the classical system.

While imputation passes the benefit of company tax paid as an imputed credit to shareholders, not all shareholders may value these imputation credits to the same extent, creating an impetus for a company to stream dividends with imputation credits to those shareholders best able to use the imputation credit.

The legislature has consistently sought to inhibit this practice by the imposition of sanctions, rather than by prohibition.

This article reviews the evolution of the measures adopted by the revenue to prevent dividend streaming, providing an overview of the legislative regimes rather than examining any particular measure in detail.

The move from a classical system of taxing dividends to a system of dividend imputation is a move towards a more integrated taxation of the company and shareholders. In accordance with this, the government has maintained that two fundamental principles of the imputation system are that:

• imputation benefits should only be available to the true economic owners of shares, and only to the extent the shareholders can use the imputation credits themselves; and

• company tax paid be imputed to shareholders proportionately to their shareholding.[1]

However, because of different tax liabilities which shareholders may have, the value of imputation credits will not be the same for all shareholders.

Resident shareholders with income other than the dividend distribution and a marginal tax rate at or above the company rate would value imputation credits, since they directly reduce the tax burden otherwise imposed. Such shareholders would seek to receive franked dividends from the company distribution, with these franked dividends carrying imputation credits.

For other shareholders imputation credits will be of little or no value, and such shareholders would prefer a company dividend distribution to be in the form of unfranked dividends, as the imputation credit carried with franked dividends is wasted. Shareholders in this group would include non-resident shareholders who would receive a better return from an unfranked dividend subject to dividend withholding tax at less than the company tax rate, [2] than from a franked dividend exempt from dividend withholding tax.[3]

These preferences of shareholders to receive dividends in the most tax effective manner have contributed to the impetus for companies to seek to stream franked or unfranked dividends to those shareholders to whom that particular dividend type is of greater value. In this way the return to shareholders can be maximised and the effective tax rate for shareholders minimised.

By its very nature, dividend streaming violates one of the propositions which the revenue sees as fundamental to the imputation regime, in that its purpose is not to spread tax paid at the company level to all shareholders in proportion to their shareholding. Rather, dividend streaming seeks to. direct the benefit of company tax paid, carried by imputation credits, to those shareholders who are most able to benefit from the franking rebate, to the exclusion of those shareholders not able to use imputation credits.

There are a range of measures which in broad terms may be categorised as dividend streaming, including:

• dividend selection plans, whereby shareholders have a choice of franked or unfranked dividends;

• dividend reinvestment plans, whereby dividends are notionally immediately reinvested, and issue as fully paid shares;

• bonus share plans, whereby dividends are paid as tax-exempt bonus shares; and

• scrip dividends, whereby dividends are applied in paying up new shares, without any choice by the shareholder.

By using such measures to stream dividends carrying imputation credits to shareholders able to use these credits, the potential exists to achieve a greater degree of integration between shareholder and company tax than the dividend imputation system alone can provide.[4] This is because imputation credits generated by company tax paid are not wasted by being distributed to shareholders unable to use them, allowing a greater proportion of company tax to be imputed to those shareholders receiving imputation credits.

The use of dividend streaming is viewed by revenue authorities as a breach of the fundamental principles of the imputation system as outlined above, with the legislature seeking to impose sanctions on the use of dividend streaming. Initial anti-streaming measures were introduced with the imputation system in 1987,[5] with further measures progressively introduced until the latest measures in 1998. This article reviews these anti-streaming measures as they have evolved over the decade since the introduction of the imputation regime.

In an effort to inhibit the use of dividend streaming, the legislature has introduced a range of measures since the introduction of the imputation regime. These measures may be broadly categorised as:

(i) initial anti-avoidance provisions;

(ii) specific anti-streaming provisions;

(iii) third generation provisions; and

(iv) capital benefits anti-streaming rules.

Measures introduced with the imputation system[6] fall into the following three broad areas.

The share class provisions[7] require that all dividends paid on the one class of share be franked to the same extent,[8] thus preventing the channelling of imputation credits to some shareholders in a share class in preference to others holding the same class of shares.

When dividends are paid on one share class under different resolutions, with only some of the shares in the class receiving a dividend under each resolution, then the dividends involved are deemed to be paid under the first resolution,[9] thus ensuring all dividends are franked to the same extent.

There is no requirement that interim and final dividends be franked to the same extent for the one share class. If a significant change in share ownership occurs between payment of the interim and final dividends, the final dividend can reflect the franking policy of the new shareholders, without being constrained by the dividend franking policy of the previous owners.

Genuinely different share classes[10] may receive dividends with differential franking.

In broad terms, imputation credits attached to a dividend received by a partnership or trust are included in partnership or trust income by means of grossing up the dividend.[11] The imputation credit then flows through the partnership or trust to each individual partner or beneficiary, who becomes entitled to their respective share of the imputation credit.[12] The Explanatory Memorandum to the Taxation Laws Amendment (Company Distributions) Bill 1987 suggests that this ensures that, to the maximum extent possible, franked dividends that are received through a partnership or trust are treated in the same way as those received directly by a partner or beneficiary.[13]

Resident individual partners and beneficiaries will be entitled to their share of the imputation credits by way of a franking rebate, while non-resident partners or beneficiaries will be exempt from dividend withholding tax, and will be allowed a deduction to reverse the dividend gross up at partnership or trust level.

The intention is that partnerships and trusts are not able to be used to stream franked dividends to particular partners or beneficiaries, but will pass franked dividends received to all partners or beneficiaries on the basis of their share of partnership or trust net income.

In broad terms a dividend will be treated as having been paid as part of a dividend stripping scheme if the dividend payment arises from a scheme which has the nature of dividend stripping, or which substantially has the effect of such a scheme.[14]

Such arrangements would include the issue of dividend access shares to shareholders, granting the right to all, or substantially all, of the dividends paid by the company, where there was no consideration, or minimal consideration, given by the shareholder for the issue of the dividend access shares. The company could then stream franked dividends to shareholders holding the dividend access shares.

Where a dividend is paid as part of a dividend stripping operation, no franking account credit will be allowed if the dividend is received by a company,[15] although the franking debit will still arise to the paying company.[16] If received by an individual, trust, or partnership, no gross up will occur, meaning there is no rebate amount.[17] This effectively imposes a double penalty, as the company making the distribution incurs a franking account debit, but shareholders do not gain the benefit of a franking rebate.

Rather than seeking to prohibit dividend streaming, the approach taken by the legislature involves imposition of a sanction when an arrangement is caste as a dividend streaming arrangement.

Measures to penalise dividend streaming arrangements were introduced to apply to dividends paid after 30 June 1990,[18] with significant amendments made to these measures in 1993[19] to cover arrangements involving an interposed or upstream entity between the shareholder and the company. Dividend streaming is defined[20] in terms of an arrangement[21] whereby shareholders have a choice or selection in one of the following four situations:

Where the exercise of the shareholder's choice determines whether the shareholder, or an upstream entity, receives an unfranked dividend in substitution for a franked dividend, or a franked dividend in substitution for an unfranked dividend, a dividend streaming arrangement exists.[22] Such a choice allows a shareholder to choose the level of franking which they can most effectively use, and the company then streams dividends with this franking level to the shareholder. The choice for an unfranked dividend would generally be made by non-residents, thus avoiding the wastage of imputation credits which such shareholders cannot access.

The sanction against this arrangement is a franking debit to the company paying the dividend, being the debit that would have arisen if the dividends were franked to the extent to which they would have been franked but for the arrangement.[23]

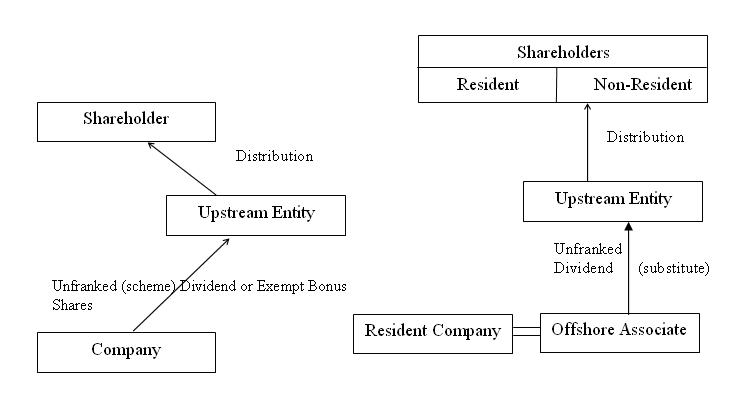

Where the exercise of choice by a shareholder results in the company issuing tax exempt bonus shares instead of paying a franked dividend, whether the bonus shares are issued to the shareholder or to an upstream entity, the arrangement is one of dividend streaming.[24] This choice enables shareholders unable to make use of imputation credits to elect to receive their distribution in a tax exempt form. By electing to receive the distribution as tax exempt bonus shares, non-residents receive a benefit which may be seen as being compensation for being unable to access the benefit of imputation credits available to residents.

A franking debit arises to the issuing company, being the debit that would have arisen if franked dividends were paid instead of the tax exempt bonus shares.[25]

This situation may be represented as shown below.

In the situation where shareholders exercise a choice for an unfranked or partly franked dividend from another company in substitution for a franked dividend from the first company, including where the payment is directed through an upstream entity, the arrangement is dividend streaming. [26]

Such a situation may arise where non-resident shareholders choose to receive an unfranked dividend from an offshore associate of an Australian company in substitution for a franked dividend from the Australian company. Non-resident shareholders benefit because the unfranked dividend has been paid outside Australia, avoiding imposition of Australian dividend withholding tax. Such a choice would be of benefit if the non-resident shareholder would not be entitled to a tax credit in their home country for dividend withholding tax paid on remittance from Australia. The choice would also be exercised if the dividend could be received by the non-resident as a tax free distribution from the off-shore associate.

The sanction against this arrangement is a franking debit arising to the company which would otherwise have paid the franked dividend,[27] in this example being the resident company.

Where shareholders exercise a choice to receive franked dividends from one company in substitution for unfranked dividends from another company, the arrangement is dividend streaming.[28]

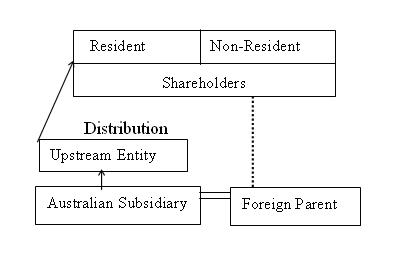

An example of an arrangement where this choice would be exercised is an Australian subsidiary of a foreign parent paying a franked dividend to resident shareholders of the off-shore parent, or an upstream entity which would distribute to resident shareholders, rather than resident shareholders receiving a dividend directly from the offshore parent. This would allow the resident shareholders to receive the benefit of imputation credits which would not be available if the dividend had been paid by the off-shore parent.

If the Australian subsidiary paid the dividend in full to the offshore parent, the benefit of Australian tax paid is lost as imputation credits cannot flow through the offshore parent. Additionally the resident shareholders could not access any imputation credits which may be generated by tax paid by the off-shore parent in its home jurisdiction, thus being doubly disadvantaged.

The sanction for dividend streaming involves a franking debit to the company paying the franked dividend.[29]

The legislative sanction against these dividend streaming arrangements involves a penalty of a franking debit to the company, thus eliminating franking credits which would otherwise have been available, or creating a franking deficit balance which would attract franking deficit tax. Shareholders incur no immediate detriment, the longer term consequence being the loss of franking credits and thus the ability of the company to frank future dividends.

From the above, it is suggested that circumstances remain under s 160AQCB for effective dividend streaming, including:

• where the shareholder does not exercise any choice or selection as to the nature of the dividend to be received;[30] or

• where differentially franked dividends are paid on separate share classes.[31]

The question arises as to whether a shareholder making a choice between purchasing shares which pay franked dividends instead of shares which pay unfranked dividends satisfies the shareholder choice requirement for dividend streaming. The suggestion is that it should not, as the choice as to purchase of shares is remote from the choice between available dividends, and should not fall within the ambit of the definition of dividend streaming in s 160APA. The dividend choice cannot be made until dividends have been declared, whereas the choice as to share purchase may be made when there are no dividends, and there may never be dividends, relating to these shares. The shareholder is relying on the distribution policy for the shares, which can never be guaranteed.

If a streaming arrangement is structured such that the ultimate shareholder has no choice as to the form of distribution, then the conditions to attract operation of s 160ACQB are not satisfied, as shareholder choice is a threshold condition for the operation of s 160AQCB. Similarly, if the entity making the choice as to the form of the distribution is not a shareholder in the company paying the substitute dividend under s 160AQCB(1) or s 160AQCB(4), then the conditions to attract the anti-streaming provisions should not be satisfied.

Further measures directed to the limitation of dividend streaming were originally announced in the 1997 Budget.[32] The intention underlying the changes was to prevent what the government saw as an unintended usage of franking credits through dividend streaming, which if continued had the potential to..."bring into question the affordability of the imputation system as originally designed".[33] In announcing the measures the government recognised that the specific provisions in s 160AQCB had not been wholly effective in restricting dividend streaming.

In addressing the limited effectiveness of the earlier anti-streaming measures, the government has adopted a broader approach, seeking to categorise such arrangements in general terms, rather than prescribing specific conditions which attract a sanction.

The five major limbs of the new approach comprise:

1. a general anti-avoidance rule;

2. an anti-streaming rule;

3. a revised share class rule;

4. a holding period rule; and

5. limiting franking by exempting companies.

The general anti-avoidance provision in s 177EA of the ITAA36 is designed to operate when there is a scheme to obtain a tax advantage in relation to franking credits. The legislative approach is modelled on the existing Pt IVA, becoming part of an extended Pt IVA.

The conditions to trigger the operation of s 177EA are detailed in s 177EA(3), involving:

(a) a scheme for the disposition of shares or an Interest in shares;

(b) a frankable dividend paid or expected, or a distribution in respect of shares, and the dividend or distribution is expected to be franked;

(c) a person would receive a franking credit benefit; and

(d) the scheme is entered into for the purpose of obtaining the franking credit benefit.

These requirements are considered below.

A scheme for disposition is defined in the proposed s 177EA(14) in wide terms to include:

• issuing shares or creating interests;

• any contract, arrangement, transaction or dealing that affects legal or equitable ownership;

• creating, varying, or revoking a trust in relation to the shares or interests;

• substantially altering risks of loss or opportunities for profit; and

• adding or removing shares or interests from insurance funds of life assurance companies.

The issuing of a dividend access share or an interest in a trust, where the purpose is to stream franking credits to a particular shareholder or beneficiary, will be treated as a scheme for disposition of shares.[34] In these cases the issuing of the share or interest is sufficient to fall within the wide ambit of a scheme for disposition.

There will not need to be a legal disposal of shares or an interest in shares to qualify as a scheme for disposal. A de facto sale or disposition, whereby a taxpayer transfers the right to income from shares, is sufficient to constitute a scheme for disposition of shares.[35]

If a shareholder who is unable to fully use franking credits "lends" shares, for a period during which a dividend is paid, to a "borrower" who then gains the advantage of the dividend and associated franking credits, the anti-avoidance rule will treat the arrangement as a scheme for disposal of shares by the lender, with a purpose of giving the borrower the franking credit benefit.[36]

Given the existing wide definition of scheme in s 177A, and the finding in FC of T v Peabody[37] that, in general terms, a part of a scheme that can stand alone is a scheme in its own right, the broad definition here only serves to confirm the wide interpretation ascribed to a scheme. With this wide interpretation of a scheme, to avoid attracting the operation of s 177EA will require that one of the other threshold conditions not be satisfied.

A frankable dividend[38] in broad terms is a dividend within the definition in s 6 of the ITAA36, which is paid after the introduction of the imputation regime, thus being a dividend capable of carrying franking credits.

A franking credit benefit as provided by s 177EA(18) is defined to include:

• a franking credit in a company franking account;

• a s 46 inter-corporate dividend rebate on a franked dividend;

• a franking rebate received as a result of the gross up of a franked dividend received by a partnership or trust;

• a franking rebate for an individual shareholder; and

• an exemption from dividend withholding tax on a franked dividend.

This gives a wide interpretation to a franking credit benefit to include any advantage which can be carried by a franked dividend.

The purpose of obtaining a franking credit benefit need not be the dominant purpose underlying the scheme for disposition to attract s 177EA, but can be something less than a dominant purpose. The section will not apply if the purpose is an incidental purpose, being one which occurs fortuitously, or occurs in conjunction with, but subordinate to, another purpose, or merely follows as the natural incident of another purpose.[39]

In determining the purpose, regard is had to the circumstances of the scheme as detailed in s 177EA(19). In general terms these include:

• the extent to which the person receiving the dividend is exposed to risks and opportunities of owning shares or an interest in shares, with risk being a pointer as to where true ownership lies;

• the length of the period for which the holder has been exposed to risks and opportunities of ownership;

• the tax profiles of parties to the scheme, concerning whether one party can better use franking credits; and whether wastage of franking credits has been minimised;

• consideration paid on the disposal, and the extent to which this represents the value of franking;

• associated deductions or losses;

• whether the dividend or distribution is equivalent to interest; and

• whether the parties are acting at arm's length and in the ordinary course of business.[40]

In addition to these factors, the matters in s 177D of the original Pt IVA are relevant circumstances to which regard may be had in identifying the purpose.

The purpose to be gleaned from the relevant circumstances is to be an objective purpose, being whether it could be objectively concluded that the scheme was entered into for the purpose of obtaining a franking credit tax advantage.

To avoid falling within the purpose test, the relevant purpose must be one which is only an incidental purpose, creating the difficulty of determining the ambit of an incidental purpose. Some guidance is provided on s 177EA(4), with the Explanatory Memorandum providing that when shares are acquired for the capital growth which would accrue, the receipt of a franking credit benefit from a franked dividend would be only incidental to the real purpose for acquisition.[41] This is contrasted with a company entering a scheme for disposition for the immediate purpose of a tax advantage, and another substantial purpose of obtaining franking credits to pass to shareholders.[42] In this case the latter purpose would not be incidental, and would be a sufficient purpose to attract the operation of the provisions.

From the decision in FC of T v Spotless Services[43] it would seem that the strength of a commercial purpose for an arrangement has been somewhat diminished if there is also a tax benefit, and it is suggested here that this trend is continued by the new regime. If the scope ascribed to an incidental purpose is increasingly narrowly construed, then the danger exists that undertakings based on a true commercial motive may face adverse tax consequences due to what was effectively a lesser purpose activating the sanction in s 177EA.

Unless the scope of an incidental purpose encompasses commercially driven arrangements there is the possibility of constraint on normal commercial activity for fear of attracting the new general anti-avoidance provision.

If the threshold conditions are satisfied, the operative provision in s 177EA(5) allows the Commissioner to determine either to raise a debit to the paying company's franking account, or alternatively to deny the franking credit benefit in respect of the dividend or distribution to the relevant taxpayer.

If a debit is posted to the company franking account, the Commissioner again has discretion to determine a reasonable amount, but the amount cannot exceed the franking debit that would arise if the dividend had been paid as franked.

If the Commissioner has determined that no debit will arise in the franking account, then the franking credit benefit derived by the shareholder will be denied by invoking one of the following:

• no franking credit in a company franking account; or

• no s 46 inter-corporate dividend rebate on a franked dividend; or

• no franking rebate resulting from the gross up of a franked dividend received by a partnership or trust; or

• no franking rebate for an individual shareholder; or

• no exemption from dividend withholding tax on a franked dividend.

By allowing the Commissioner to determine the manner by which to reverse the franking credit benefit, s 177EA grants a wider range of sanctions than existed under s 160AQCB discussed above, where the deterrent was limited to a franking debit. The sanction imposed is more in line with that available under s 177F, whereby the Commissioner has the broad power to cancel a tax benefit. With s 177EA incorporated within Pt IVA, this broader power seems in keeping with the rationale of Pt IVA as a general anti-avoidance provision.

The operation of the original Pt IVA requires the gaining of a tax benefit, with s 177C referring to the non-inclusion of an otherwise assessable amount, or the deductibility of an otherwise non-deductible amount as constituting a tax benefit.[44] However, the Commissioner has sought to expand this meaning in Income Taxation Ruling IT 2456 to include amounts which, for example, would already be assessable, but because of the scheme attract concessional treatment.

The approach taken in the new s 177EA broadens the whole scope of the expanded Pt IVA. Rather than being limited to schemes creating a benefit in taxable income of the taxpayer, the introduction of the notion of a scheme involving a franking credit benefit adds a new dimension to Pt IVA, making a far greater range of schemes potentially vulnerable to review by the Commissioner.

There appears to be some overlap between the new s 177EA in terms of a scheme for disposition, and the existing s 177E dealing with dividend stripping. Both provisions could cover the issuing of dividend access shares, and the payment of a dividend on these shares, so theoretically both provisions could operate.

However, both provisions require a determination by the Commissioner as to the sanction to be imposed, so it must be presumed that only one provision would apply in any given situation. It may be that s 177EA would be the preferred provision for the Commissioner, since s 177EA has a wider threshold test of a scheme for disposition than the test in s 177E, which may be more difficult to establish.

There are situations, however, where s 177E may apply but the new s 177EA would have no application. While s 177EA deals only with distributions in the form of dividends, s 177E deals with a disposal of property of the company, including:

• the making of loans;

• bailment of property; or

• any transaction diminishing the value of property of the company.

In this regard it is suggested that this wider scope of s 177E in regard to the manner of distributions would see a remaining role for the provision.

In addition to the general anti-avoidance provisions, new legislation in s 160AQCBA of the ITAA36 specifically targets dividend streaming arrangements. In general terms the provisions are intended to apply when a company streams dividends and other payments to shareholders so that those shareholders most able to utilise franking credits receive greater franking credits than other shareholders.[45] The approach follows the pattern in s 160AQCB in that there is no specific prohibition on dividend streaming, the measures seeking to inhibit the practice through sanction to remove franking benefits.

An essential component of the s 160AQCB anti-streaming arrangements above is that the provisions are dependent on the shareholder exercising a choice between receiving a franked or unfranked distribution. The new anti-streaming rule in s 160AQCBA no longer requires a shareholder choice, the test being broadly objective by looking to whether dividends are paid to shareholders such that franked dividends are directed to shareholders to whom they are of greater value.

The threshold test in s 160AQCBA(2) requires that a company streams the payment of dividends and/or the giving of other benefits to shareholders such that those shareholders most able to use franking credits receive a greater franking credit benefit than shareholders not benefiting from franking credits.[46]

This test takes an objective approach, looking to the outcomes of the payment of dividends in terms of the franking credit benefit that shareholders receive from dividends paid and other benefits given. To qualify as dividend streaming the distribution from the company must be directed such that shareholders receive differential franking credit benefits, with greater franking credit benefits going to shareholders able to utilise them, and other benefits potentially being distributed to shareholders to whom franking credits are of less value.

The concept of what constitutes a franking credit benefit in the hands of the recipient of the dividend or other benefit is critical in determining whether the threshold test has been satisfied.

As noted earlier, the concept of a franking credit benefit is widely defined in the new s 160AQCBA(16) to encompass all potential benefits arising from the distribution of a franked dividend, including:

• a company having a franking account credit entry;

• a private company obtaining an inter-corporate dividend rebate from a franked dividend;

• a trust or partnership including a grossed up amount from a franked dividend in assessable income;

• a shareholder obtaining a franking rebate; or

• an exemption from withholding tax arising from a franked dividend.

The application of the provision is also triggered when franked dividends are streamed to some shareholders while other benefits are given to shareholders who cannot benefit from franking credits, the intention being to preserve franking credits for shareholders able to utilise them.

These other benefits are defined in the new s 160AQCBA(15) to include:

• issue of bonus shares;

• return of capital on the shares;

• forgiveness of shareholder debt to the company; and

• making any kind of payment, including property, from the company or another person, made to or on behalf of the shareholder.

An example of such a benefit is payment of a superannuation contribution by the company on behalf of the shareholder, in lieu of a franked dividend to the shareholder.[47] The intention is that the concept of other benefits includes amounts given other than by the company.

To establish whether shareholders receive different benefits from franking credits, the new s 160AQCBA(17) provides a non-exhaustive list of circumstances when a lesser benefit is derived, including:

• when the shareholder is a non-resident;

• when shareholder tax payable is less than the franking rebate;

• when a company shareholder has made insufficient profits to pay a dividend; and

• a company shareholder derives no franking account credits.

When the threshold conditions are satisfied the operative provision in s 160AQCBA(3) allows the Commissioner to make a determination in regard to the franking benefits available. The Commissioner can determine that either a franking debit arises to the company paying the dividend, or that the franking credit benefit be denied to the recipient.

The franking debit is broadly determined as being the difference in franking between the dividend to those who receive most franking credits, and those who do not derive as great a franking credit. Where the streaming involves the payment of other benefits, the franking debit arising will in general terms be the debit that would have arisen if a dividend equal in value to the benefit provided had been franked to the same extent as the streamed dividend.

If the Commissioner determines that it is inappropriate that a franking debit be imposed, then the franking credit benefit carried by the streamed franked dividend can be denied. The result of the denial of the franking credit to the recipient of the franking credit benefit will depend on the particular franking credit benefit received, resulting in:

• no franking credit in the franking account of a company receiving the franked dividend;

• denial of the inter-corporate dividend rebate to a company recipient;

• denial of the s 160AQT gross-up, resulting in there being no franking rebate amount under s 160AQU;

• denial of the franking rebate to an individual shareholder; or

• loss of the exemption from dividend withholding tax which is available to franked dividends.[48]

The new s 160AQCBA does not limit the Commissioner to debiting the franking account of the company paying the dividend or other benefit, as under s 160AQCB, but additionally allows the Commissioner to choose an alternative determination that the franking credit benefit be denied to the recipient of such benefit.

It may be argued that the ultimate effect would be the same under both regimes, in that the franking account debit reduces franking credits available for a future distribution. However in the event of a change in shareholding before such future distribution, the previous shareholders would have benefited from imputation credits at the direct expense of the incoming shareholders.

Given that the anti-streaming provisions in s 160AQCB remain operative, there are potentially three provisions which may be triggered by a dividend streaming arrangement, being s 177EA, s 160AQCB, and s 160AQCBA. It would be presumed that only one of the measures would be applied in relation to any particular incidence of dividend streaming.

The consequence of not limiting the application of the provisions could effectively result in a double detriment. If both s 160AQCB and s 160AQCBA were applicable in a particular arrangement, the Commissioner could make a determination under s 160AQCBA(3) to deny a franking credit benefit to a shareholder, thus reversing the franking credit benefit that would otherwise arise. However as s 160AQCB applies automatically, requiring no determination by the Commissioner, then the sanction of a franking debit to the company arises automatically.

It may be that in looking for the appropriate provision to apply the Commissioner may look firstly to the new s 160AQCBA rather than to s 160AQCB. The threshold test for the operation of s 160ACQB requires that the shareholder exercise a choice resulting in receipt of a franked or unfranked distribution. To attract the operation of s 160AQCBA requires no such choice, with a more objective approach taken by looking to the streaming of dividends so as to give some shareholders a greater benefit than others. It is suggested that from the Commissioner's view this latter test may be more easily satisfied.

A further advantage of s 160AQCBA from the Commissioner's view would be that there is an option as to the imposition of the sanction at the company or shareholder level, while s 160AQCB allows no such flexibility in the sanction imposed.

The approach to be taken by the ATO in the interaction of the provisions in operation remains to be seen, and it may well be that there will be a role for adjudication by the courts.

In addition to the anti-streaming amendments, the new provisions more narrowly define share classes, the intention being, presumably, to limit the use of different share classes as a legitimate method of paying differentially franked dividends.

The new definition of share class replaces the existing s 160APE definition of share class, providing that a class of shares includes all shares having substantially the same rights, so inconsequential differences in rights would not constitute a different share class. The Explanatory Memorandum suggests that where rights are substantially the same, with differences existing only in voting rights, then these shares would now be considered to constitute the one class of share.[49]

It is suggested that a difficulty with this approach is that it tends to ignore the commercial reality that the differences that exist between share classes are frequently differences in voting rights. The tax legislation itself, whenever considering rights carried by shares, consistently looks to the matters of:

• differences in voting rights;

• differences in dividend rights; and

• differences in rights to distribution of capital on winding up.

If the new definition intends that differences in voting rights and differences in dividend rights are merely inconsequential differences between shares, as suggested by the Explanatory Memorandum, the question arises as to the what differences would be sufficiently substantial for shares to be in different classes. The approach of dismissing commercial differences between shares as being inconsequential seems an unusual approach to adopt in categorising share classes, when this is where most differences lie.

The potential is created for shareholders to be holding shares which under the previous definition fall under different share classes, but which under the new definition would be within the same share class, without any action by the shareholder. In this event, any differential franking of dividends would result in all dividends being deemed franked to the same extent.

A further limb of the government offensive against optimal use franking credits involves proposed measures[50] to prescribe a minimum holding period for shares before a taxpayer becomes entitled to the benefits carried by a franked distribution. The rationale for this approach is based on preventing inappropriate access to franking rebates or an inter-corporate dividend rebate for a taxpayer who is not exposed to the risks and opportunities of share ownership.

This rule differs from those considered above, in that the holding period rule is directed solely to activities of shareholders, while the provisions in s 160AQCBA relate to actions of a company. While not specifically directed to dividend streaming, the holding period rule is briefly outlined so as to illustrate the range of measures directed against attempts to maximising the use of franking credits generated from company tax.

To be entitled to a franking credit, franking rebate, or inter-corporate dividend rebate, a taxpayer must be a qualified person as defined in s 160APHD. A taxpayer is a qualified person if the taxpayer satisfies the related payments rule, and:

A related payment arises when there is an actual payment, or some other method is used, to pass the benefit of a dividend or distribution received by the taxpayer or associate, to another person. A related payment also arises if the taxpayer or associate are under an obligation to pass the benefit from the dividend or distribution, or may reasonably be expected to pass the benefit from the dividend or distribution, to another person.[51]

The holding period test[52] requires that the shareholder holds a legal or equitable interest in shares for a minimum period of 45 days. This 45 day period must fall during the qualification period,[53] commencing on the day after acquisition, and terminating on the 45th day after the day on which the shares go ex-dividend. In calculating the 45 day period, days both before and after the dividend payment can be included.

The holding period is determined by reference to the dates of acquisition and disposal. When shares, or interests in shares, are acquired or disposed of for a fixed price under an unconditional contract, the shares or interests are taken to be acquired or disposed of at the time of making the contract.[54]

A disposal of the shares is deemed to have occurred when a taxpayer disposes of substantially identical securities during the qualification period, and during this period the taxpayer received a franking credit, franking rebate, or inter-corporate dividend rebate, from a dividend paid on the securities.[55] Substantially identical securities are defined as being property economically equivalent to the shares, or whose value is linked to the shares.[56] The deemed disposal will end the qualification period, and if this period is less than 45 days, the taxpayer ceases to be a qualified person and is denied the benefit from the franked dividend.

A disposal of the shares will also be deemed when a connected person disposes of substantially identical securities under an arrangement with the taxpayer.[57] A connected person includes an associate of the taxpayer, and a company in the same wholly owned group.[58]

Where a taxpayer is issued with shares as part of a winding up, and the taxpayer does not dispose of the shares before the commencement of the winding up, and has not made a related payment, the taxpayer is a qualified person in terms of s 160APHD.[59]

Taxpayers who are trustees of complying superannuation funds, complying approved deposit funds, pooled superannuation trusts, and life assurance companies can elect to have a franking credit or franking rebate ceiling,[60] and upon making such irrevocable decision, the taxpayer becomes a qualified person, unless a related payment has been made.

The rationale for the different treatment is that such taxpayers would incur high compliance costs to meet the holding period rule, and they are low revenue risk taxpayers.

An individual taxpayer may elect to have a franking rebate ceiling applied,[61] instead of meeting the holding period rule, such election making the taxpayer a qualified person, unless a related payment has been made. If the franking rebates available to the individual exceed the nominated ceiling of $2000, then to calculate the rebate available to the taxpayer, the $2000 maximum is reduced by $4 for each $1 by which the actual rebate exceed the $2000 ceiling.[62]

If a taxpayer fails to qualify as a qualified person then the sanction imposed involves the denial of the benefit carried by the franked dividend. Companies will be denied a franking account credit and the inter-corporate dividend rebate, while individual taxpayers will not have the s 160AQT gross-up and s 160AQU rebate.

As with the holding period rule, the measures[63] to limit franking of dividends from exempting companies are directed more to preventing trading in franking credits rather than at dividend streaming, and as such are outside the scope of this article. The measures are briefly outlined to provide a complete view of the government response to the attempts to maximise the use of franking credits.

The measures are directed to exempting companies,[64] being companies effectively wholly-owned by prescribed persons, defined[65] to be exempt taxpayers or non-residents. This effective ownership may be direct ownership,[66] or indirect ownership traced through interposed entities.[67]

While exempting companies are required to maintain a franking account, in broad terms dividends paid will carry no franking benefits to recipients.

Under amendments to s 46F, a franked dividend paid from an exempting company to a private company will not generate an inter-corporate dividend rebate, and a franked dividend from an exempting company to a corporate shareholder will generally not create a franking credit in the franking account.[68] A franked dividend from one exempting company to another exempting company may create a franking credit if both companies are members of the same effectively wholly-owned exempting company group.[69]

For franked dividends paid by an exempting company to an individual taxpayer, the entitlement to a franking rebate is removed by prohibiting the s 160AQT gross-up, which then precludes there being any rebate entitlement under s 160AQU.[70]

Following from changes made to corporations law,[71] which abolished par value for shares and the associated concepts of share premiums and share premium accounts, the government has introduced consequential changes[72] to the tax regime. The corporations law changes effectively created one share capital account, thus increasing the amount of capital available for distribution to shareholders and allowing the capitalisation of profits without issuing shares. The new legislation is intended to prevent this ease of capital distribution being used for dividend substitution and capital streaming.

This anti-avoidance rule is designed to prevent streaming of benefits in three situations:

• streaming bonus shares in lieu of unfranked dividends;

• streaming of capital benefits; and

• schemes to confer a capital benefit.

The threshold conditions for s 45 of the ITAA36 are satisfied if the company issues shares to some but not all shareholders, with a minimally franked dividend being paid to those shareholders not being provided with shares. A minimally franked divided is an unfranked dividend, or a dividend franked to less than 10%.[73]

The provision is directed towards preventing the distribution of profits of a company in a capital format which then attracts preferential tax treatment, rather than the distribution being made as an unfranked dividend which would be fully taxed in the hands of the shareholders.

When the threshold test is satisfied, the sanction imposed is that the value of the issued shares is treated as an unfranked and unrebatable dividend, thus precluding the possibility of an inter-corporate dividend rebate, and ensuring the amount is fully taxable in the hands of shareholders.[74] The section operates automatically once the conditions are met, with no determination required by the Commissioner.

The second of the capital anti-avoidance rules is triggered when a company streams capital benefits to those shareholders who would gain a tax benefit from receiving capital, and pays dividends to those who would not benefit from receipt of capital,[75] and s 45 does not apply. A capital benefit provided by a company is defined in s 45A(3) to be:

• provision of shares to a shareholder; or

• distribution of share capital to a shareholder; or

• doing an act that increases the value of shares held by the shareholder, such as changing share rights such that the shares of a shareholder increase in value.

Section 45A(4) provides a non-exhaustive list of circumstances where a shareholder is likely to receive a greater benefit from the capital benefit than other shareholders not receiving the capital benefit, including:

• the shareholder holding pre-CGT shares;

• the shareholder being non-resident;

• the cost base of the shares being not substantially less than the capital benefit;

• the shareholder having a capital loss or income tax loss; or

• the shareholder being a private company receiving an inter-corporate dividend rebate.

In each of these situations, the shareholder is in a position where the receipt of a capital amount results in a tax advantage being gained, either through reducing taxable income or reducing tax payable, where the tax advantage would not arise if a dividend had been received.

The provision will not apply when the capital benefit is the provision of shares, and shareholders not receiving the shares receive a franked dividend.[76]

The sanction imposed to prevent this streaming of dividends and capital benefits is in terms of a determination made by the Commissioner under s 45C that the value of the capital benefit be treated as an assessable dividend which is unfranked and unrebatable. This will have the effect of reversing the capital benefit otherwise available to the shareholder, with the amount being assessable, with no offsetting inter-corporate dividend rebate if the shareholder is a private company.

The new provision contained in s 45B is wider in scope than those in ss 45 and 45A, being an anti-avoidance measure to apply where:

• there is a scheme whereby a person receives a capital benefit from the company;

• under the scheme a taxpayer obtains a tax benefit; and

• the purpose of the scheme is to enable the taxpayer to obtain the tax benefit.

A scheme takes the same broad meaning as in Pt IVA of the legislation; and capital benefit takes the same meaning as in s 45A above. A tax benefit under s 45B includes:

• a taxpayer paying less tax than would be the case if a dividend had been received;

• a taxpayer paying the tax liability at a later time than if a dividend had been received; or

• a taxpayer obtaining a greater refund.[77]

The approach taken here differs from the concept of a tax benefit under s 177C in Pt IVA. While s 45B looks directly to the actual net tax payable, s 177C looks to changes in the taxable income resulting from the scheme, thus only indirectly being concerned with tax payable. Also the timing of the tax payment is not considered in s 177C. These differences would suggest that a wider range of tax benefits would be encompassed by s 45B than would fall under s 177C.

The scope of the purpose in s 45B follows from the wide meaning in the new s 177EA(3) in the general anti-avoidance rule discussed above. For s 45B the purpose of the tax benefit from the scheme need not be a sole or dominant purpose, but will fail to satisfy the threshold requirement if it is an incidental purpose, occurring fortuitously, or merely following as the natural incident from the main purpose.[78] The purpose will be the objectively determined purpose from the relevant circumstances as listed in s 45B(5), including:

• the extent to which the distribution is attributable to profits of the company;

• the pattern of distributions by the company;

• the tax outcome if the anti-avoidance rule did not apply;

• whether an inter-corporate dividend rebate would not be available on a dividend;

• whether the taxpayer's interests are altered by a distribution of share capital; and

• whether the equivalent of a cash dividend is obtained in a more tax effective form.

The matters listed in s 177D are also specifically encompassed as matters to be considered in determining the relevant purpose for s 45B.

The Commissioner can make a determination under s 45C that the amount of the capital benefit be treated as an unfranked and unrebatable dividend paid out of company profits, thus being fully assessable in the hands of the recipient. Further, the Commissioner can determine that the scheme was for the purpose of avoiding franking debits, in which case there is a discretion to impose a franking debit on the company.

This further discretion appears to amount to a right to double tax, as the capital benefit will be fully taxed as an unfranked dividend to the shareholder, and additionally franking credits are denied to the company. Such treatment appears onerous, even given the desire to preclude the entering of schemes to generate a tax benefit.

The concern of corporate Australia and shareholders at the extent of the Australian anti-streaming arrangements was evident as far back as 1992, with the presentation of a detailed submission to the Treasurer in June 1992 by Australian corporations arguing for an easing of dividend streaming. Arguments presented looked to the competitive advantage foreign companies had over Australian companies when seeking capital on world markets, and examined benefits Australia would gain by easing offshore streaming rules for international investors.

The government did not accept the recommendations, and in the ensuing period the revenue has consistently acted against dividend streaming arrangements. The approach adopted by the government, as indicated in the 1997 Budget papers,[79] suggests that the dividend imputation provisions were intended to ensure that company tax was imputed to shareholders in proportion to their holdings, and to ensure imputation benefits would only be available to "true economic shareholders" to the extent to which the shareholder could use them.

The revenue impact of the imputation provisions was calculated on the basis that many franking credits would be wasted, and this appears to remain the government intention. The underlying approach is illustrated in the language used in the description of streaming arrangements. While companies view such arrangements as an attempt to maximise the value of what is a valuable asset to shareholders, the revenue sees anti-streaming provisions as necessary to ".. curb the unintended usage of franking credits...".[80]

Given that the introduction of dividend imputation was generally seen as a move towards a more integrated system of taxing corporate income, it seems paradoxical that government policy is based on preventing the means by which imputation credits may be most fully utilised, and greater integration achieved.

Rodney Fisher is a Senior Lecturer at the Faculty of Business and Law at Central Queensland University. He holds BBus, BEc, Master of Tax and Master of Financial Management degrees. Rodney is currently a consultant to the Australian Taxation Office on the development of expert tax systems. Rodney has also previously published in various other law and accounting journals.

[1] ATP Bills and Explanatory Memoranda to Taxation Laws Amendment Bill (No 7) 1997, 5162.

[2] Generally 15% for treaty countries; 30% for non-treaty countries.

[3] Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 ("ITAA36"), s 128B(3)(ga).

[4] It is suggested that currently up to half of imputation credits are not used because shareholders have insufficient other income, franked dividends are paid offshore, or companies pay insufficient franked dividends; see D Duckett, "The Globalised Economy" (1995) 4(2) Taxation in Australia (Red edition) 87, 88.

[5] Introduced by the Taxation Laws Amendment (Company Distribution) Bill 1987.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Australian Federal Tax Reporter (CCH loose leaf service) Explanatory Notes to Taxation Laws Amendment (Company Distribution) Bill 1987, 886,259.

[9] ITAA36, s 160AQG.

[10] ITAA36, s 160APE.

[11] ITAA36, s 160AQT.

[12] ITAA36, ss 160AQX and 160AQZ.

[13] Australian Federal Tax Reporter, above n 8.

[14] ITAA36, s 177E.

[15] ITAA36, s 160APP(6).

[16] ITAA36, s 160AQB.

[17] ITAA36, s 160AQT.

[18] Introduced by the Taxation Laws Amendment Bill (No 2) 1990.

[19] Introduced by the Taxation Laws Amendment Bill 1993, replacing the Taxation Laws Amendment Bill (No 7) 1992 which had lapsed on dissolution of Parliament.

[20] Defined in ITAA36, s 160APA.

[21] "Arrangement" is given a wide meaning in ITAA36, s 160APA.

[22] ITAA36, s 160APA (definition of "dividend streaming arrangement").

[23] ITAA36, s 160AQCB(1).

[24] ITAA36, s 160APA (definition of "dividend streaming arrangement").

[25] ITAA36, s 160AQCB(2).

[26] ITAA36, s 160APA (definition of "dividend streaming arrangement").

[27] ITAA36, s 160AQCB(3).

[28] ITAA36, s 160APA(b) (definition of "dividend streaming arrangement").

[29] ITAA36, ss 160AQCB(4), (4A).

[30] As required pursuant to the definition of dividend streaming arrangement in ITAA36, s 160APA.

[31] Within the terms of ITAA36, s 160APE prior to its amendment under the Taxation Laws Amendment Bill (No 7) 1997.

[32] Measures introduced by the Taxation Laws Amendment Bill (No 7) 1997; passed as the Taxation Laws Amendment Bill (No 3) 1998; and received assent on 23 June 1998 as Act No 47 of 1998.

[33] 1997 Budget Papers, "Measures Introduced in the 1997-98 Budget" Budget Paper No 2, 175.

[34] ATP Bills and Explanatory Memoranda to Taxation Laws Amendment Bill (No 7) 1997, 5173.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Ibid.

[37] 94 ATC 4663.

[38] Defined in ITAA36, s 160APA.

[39] ATP Bills and Explanatory Memoranda to Taxation Laws Amendment Bill (No 7) 1997, 5177.

[40] This final factor, while not mentioned in s 177EA(19), is raised as a matter to consider in the ATP Bills and Explanatory Memoranda to Taxation Laws Amendment Bill (No 7) 1997, 5179.

[41] ATP Bills and Explanatory Memoranda to Taxation Laws Amendment Bill (No 7) 1997, 5175-6.

[42] Ibid 5176.

[43] 96 ATC 5201.

[44] ITAA36, s 177C.

[45] ATP Bills and Explanatory Memoranda to Taxation Laws Amendment Bill (No 7) 1997, 5163.

[46] Ibid.

[47] Ibid 5165.

[48] ITAA36, s 128B(3)(ga).

[49] ATP Bills and Explanatory Memoranda to Taxation Laws Amendment Bill (No 7) 1997, 5168.

[50] ITAA36, proposed Div 1A in Pt IIIAA comprising ss 160APHC - 160APHU; and Subdivs B and BB of Div 7 of Pt IIIAA comprising ss 160AQZB - 160AQZI; originally introduced by the Taxation Laws Amendment Bill (No 5) 1998 which lapsed but were reintroduced by the Taxation Laws Amendment Bill (No 4) 1998 on 3 December 1998.

[51] ITAA36, proposed s 160APHN.

[52] ITAA36, proposed s 160APHO.

[53] ITAA36, proposed s 160APHD (definition of "qualification period").

[54] ITAA36, proposed s 160APHH.

[55] ITAA36, proposed s 160APHI.

[56] ITAA36, proposed s 160APHF.

[57] ITAA36, proposed s 160APHI(2).

[58] ITAA36, proposed s 160APHI(3).

[59] ITAA36, proposed s 160APHQ.

[60] ITAA36, proposed s 160APHR.

[61] ITAA36, proposed s 160APHT.

[62] ITAA36, proposed s 160AQZH.

[63] Sections 160APHBA - 160APHBJ and ss 160AQCND - 160AQCNP inserted in the ITAA36 by the Taxation Laws Amendment Bill (No 4) 1998.

[64] Defined in ITAA36, new s 160APHBA.

[65] ITAA36, new s 160APHBF.

[66] ITAA36, new s 160APHBB.

[67] ITAA36, new ss 160APHBF & 160APHBG.

[68] ITAA36, new s 160APP(1AAA).

[69] ITAA36, new s 160APPA.

[70] ITAA36, new s 160AQTA.

[71] The First Corporate Law Simplification Act 1995 and the Company Law Reform Bill 1997 which received assent on 29 June 1998 as Act No 61 of 1998.

[72] Taxation Laws Amendment (Company Law Review) Bill 1998 which received assent on 29 June 1998 as Act No 63 of 1998.

[73] ITAA36, s 45(3).

[74] ITAA36, s 45(2).

[75] ITAA36, s 45A.

[76] ITAA36, s 45A(5).

[77] This last benefit is not listed in s 45B(7), but is included as a tax benefit in ATP Bills and Explanatory Memoranda to Taxation Laws Amendment (Company Law Review) Bill 1998, 413.

[78] Explanatory Memorandum to the Taxation Law Amendment (Company Law Review) Bill 1998.

[79] 1997 Budget Papers, above n 33.

[80] ATP Bills and Explanatory Memoranda to Taxation Laws Amendment Bill (No 4) 1998, 325.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/JlATax/1999/3.html