Journal of Australian Taxation

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Journal of Australian Taxation |

|

THE GST PACKAGE: HAS THE SENATE RESOLVED THE CONTROVERSIES?

By Ross Guest

This article evaluates the success of the Senate Select Committee on A New Tax System in resolving the major controversies in the GST debate. The article concludes that the Senate Committee was unable to resolve most of these controversies. Only the following very broad conclusions have emerged as consensus. The impact of the GST package in terms of employment and living standards is likely to be negligible. The effect on overall income distribution varies across a range of quite reasonable assumptions. However, there will certainly be individual winners and losers and the package is regressive. There was relatively little investigation and no consensus reached on the questions of compliance costs, tax evasion and the cash economy, and revenue sustainability. The important question of the impact on national saving was not addressed. This article also draws on available empirical and theoretical evidence from other sources in evaluating the Senate's findings.

"A New Tax System" ("ANTS"),[1] the centrepiece of which is a 10% GST, was proposed by the Commonwealth Government in August 1998 to take effect from 1 July, 2000. In November 1998, the Senate agreed to establish the Select Committee on A New Tax System to inquire into ANTS. The Committee's terms of reference were to inquire into "the economic theories, assumptions, calculations, projections, estimates and modelling which underpinned the Government's proposals for taxation reform".[2] The Committee heard evidence from five economic modelling projects. These were: The Monash model developed by the Centre of Policy Studies, the Murphy models developed by Mr Chris Murphy, the Access Economics model presented by Mr Geoff Carmody, the Melbourne Institute's Orani-G model and the Microsimulation models of the National Centre for Social and Economic Modelling developed by Professors Ann Harding and Neil Warren. A wide range of other witnesses were called to give evidence. These included representatives of welfare groups, industry bodies, consumer groups, trade unions, organisations of the arts, government departments and environmentalists.

This article assesses whether the Senate Committee has resolved the major controversies in the debate about the effects of the GST package. The article does not discuss the findings of the Senate Committee on the effects on particular sectors or industries such as tourism, health, education, the arts, the environment, telecommunications, housing, aged care, child care and disability services. These effects are discussed in the reports of the various References Committees.[3] Rather, this article is restricted to the controversies about the broad effects of the GST package on employment, living standards, national saving, income distribution, compliance costs, tax evasion and revenue sustainability.

The article also seeks to outline the economic reasoning behind some of the conclusions in the Senate Report which tends to report bald conclusions from the economic modelling without giving much feel for the economic mechanisms in play. The article outlines these mechanisms where appropriate in a brief and non-technical way.

The rest of the article is organised into three sections. Part 2 explains how the GST will operate. Part 3 explains the motivation for a GST. Part 4 evaluates the contribution of the Senate Committee in resolving the controversies in the debate on the broad effects of the GST package.

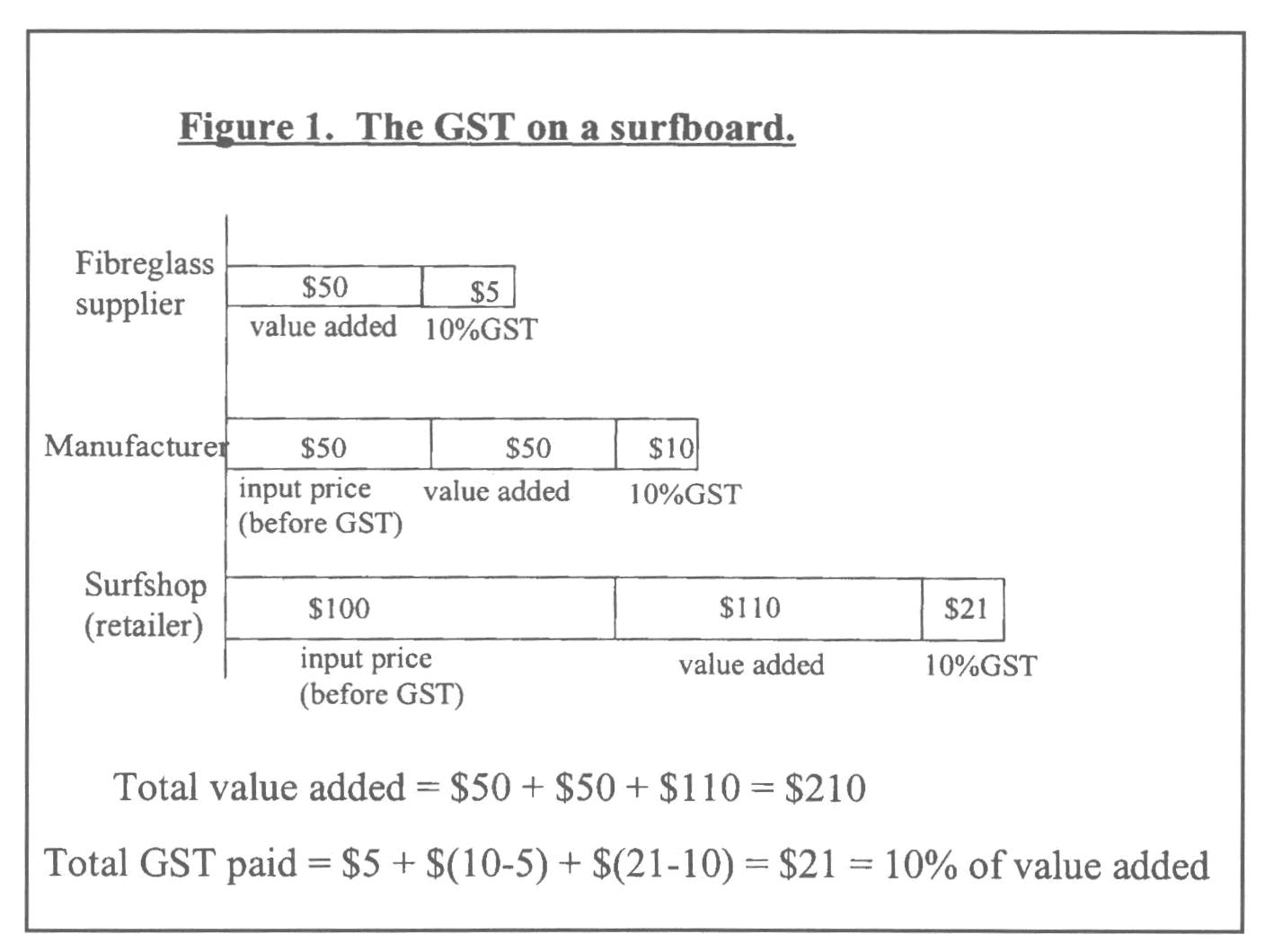

A GST is a tax on each enterprise's "value-added", that is, its total sales less the cost of the goods and services, other than labour, purchased by the firm. This is best explained by an example, illustrated in Figure 1 below. Consider the GST on a surfboard. The surf shop buys surfboards from a manufacturer who in turn buys fibreglass and other materials from a supplier. The fibreglass supplier produces $50 of value added in materials and therefore pays 10% GST=$5. (It is assumed that the fibreglass supplier has not made any purchases on which GST was paid.) The manufacturer pays the fibreglass supplier $55 including the $5 GST. The manufacturer then adds $50 of value added and sells the surfboard to the surf shop at a price (before GST) of $100 to which it adds 10% GST (=$10). However, the manufacturer gets a tax credit of the $5 tax it paid the fibreglass supplier, so its net tax is $5. The surf shop in turn produces $110 value added and sells the surfboard at a price (before GST) of $210 to which it adds 10% GST (=$21). However, it claims a tax credit of the $10 GST it paid the manufacturer, so its net tax is $11. The consumer pays $21 GST which is the sum of the net tax paid by the fibreglass supplier, the manufacturer and the surf shop. The $21 GST amounts to 10% of the sum of the value added at each stage of the supply chain. This is why the GST is called a value-added tax ('VAT") in some other countries.

Under the Government's tax package, some goods and services are to be "GST-free", which means that there will be no tax liability at the final stage of the supply chain (a zero rate in other words) and that suppliers will be able to claim tax credits for GST paid on their purchases.[4] Also, a fewer number of services will be "input-taxed" which means that, like "GST-free", there is a zero rate at the final stage of the supply chain but suppliers cannot claim a tax credit for GST paid on their inputs.[5]

The GST package is a response to the consensus view of economists that Australia's tax system performs poorly in meeting the objectives of a tax system. These objectives are vertical and horizontal equity, efficiency, simplicity and revenue raising. Vertical equity is the principle that those with a higher capacity to pay ought to pay proportionately more tax. Horizontal equity is the principle that people with equal capacity to pay tax ought to pay equal tax. An efficient tax system is one which does not distort economic choices about, for example, consumption, saving, investment and labour supply. Simplicity refers to transparency and ease of administering and complying with the tax. The revenue raising objective is that, given equal rating in terms of other objectives, taxes which raise the most revenue are to be preferred.

Table 1 below gives the 1998-99 Commonwealth Government Budget estimates of major Commonwealth taxes as a proportion of the total Commonwealth taxes for the year 1998-99.

The Federal Government's two main indirect taxes are wholesale sales tax ("WST") and excise taxes, accounting for about 10% of its total tax revenue each. The WST is levied primarily in order to raise revenue. Whereas excise taxes are levied primarily to reduce social costs associated with, for example, consumption of alcohol and tobacco, and also as a form of user pays – for example, the excise tax on petroleum products helps pay for road construction and maintenance.

The most serious problem with Australia's indirect tax system is that it is very inefficient. For example, the WST is levied at four different rates:[6] 12% (eg, juices, flavoured milk, snack foods), 22% (eg, cars, hair products, toys, computers), 32% (eg, stereos, TVs) and 45% (luxury motor vehicles). Excise taxes also apply at variable rates.

These variable rates distort choices of consumers and businesses in many ways. This creates economic inefficiency. To take an example that may seem trivial in itself but the collective effect of which is not so trivial, consider the the zero WST rate on plain milk but 12% rate on flavoured milk. The effect is to raise the price and lower the sales of flavoured milk relative to plain milk. This is inefficient because mutually beneficial transactions between consumers and producers have been restricted.[7] Of course the loss of potential economic benefits is trivial in this example. But consider the fact that all services face a zero rate of sales tax whereas a narrow range of goods face variable rates of sales and excise taxes. The economic losses from these and other distortionary taxes have been estimated at 3.75% of GDP.[8] This estimate means that replacing all the indirect taxes by a broad-based GST would increase national output of goods and services by 3.75% in the long run.

|

Table 1

|

|

|

Taxation source

|

1998-99 Budget estimate of % of total Commonwealth

taxes

|

|

Income tax - individuals

|

54.2%

|

|

Income tax - companies

|

14.4%

|

|

Wholesale sales tax

|

10.9%

|

|

Excise tax

|

10.0%

|

|

Other(incl. fringe benefits tax and customs duty)

|

10.5%

|

|

Source: Commonwealth Government Budget Paper No. 1, Commonwealth Treasury,

1998

|

|

Even greater efficiency gains are possible because the GST is to be accompanied by reductions in income tax rates. Our income tax system creates inefficiencies by imposing varying effective tax rates[9] on different types of saving and investment. For example, investment in housing, whether owner-occupied or rented, provides lower effective tax rates than investment in businesses. Saving in interest-bearing deposits attracts a higher effective tax rate than saving and investing in property.[10] The GST tax package provides for lower income tax rates by switching the tax mix toward indirect taxes. Lower income tax rates would reduce but not eliminate the distortions arising from varying effective income tax rates.

In summary, the inefficiencies in our existing tax system is the main economic argument for tax reform. However, the tax reform in the GST package will have other effects, the extent and merits of which are more debatable. Broadly speakings, the aim of the Senate Committee was to attempt to resolve these controversies as far as possible. The next part evaluates the controversies about the effects of the GST package in light of the Senate's findings.

The ANTS document claims that "the new tax system will be fairer" and that no households will be made worse off.[11] However, the majority ALP and Democrat Senators on the References Committee[12] charged with specifically addressing the impact on, among other things, the equity of the tax package, found that the package is unambiguously regressive.[13] Even the Treasury's own modelling supports this.[14] The minority Government Senators did not directly address the question of regressivity. Rather they reiterated the Treasury results, supported by Melbourne Institute modelling, that "every group modelled was better off under the tax package."[15]

Subsequently, the results of modelling by Natsem,[16] presented by Professors Harding and Warren, received much emphasis by the Senate Committee. Natsem modelled the impact of the tax package on 29 "cameo households" under 10 alternative scenarios. The first scenario is a replication of the Treasury's assumptions. In each other scenario one of the Treasury's assumptions is altered. Natsem altered the more controversial assumptions, namely: (i) that the CPI will provide an adequate measure of the likely increase in prices facing different types of households; (ii) that for the purposes of calculating the gains and losses from the tax package households are assumed not to dissave (spend more than they earn); (iii) that businesses pass on in lower prices the full impact of reductions in their WST and Stamp Duty burdens. The other scenarios modelled by Natsem consisted of exempting food with variations in the method of financing this and of compensating social security recipients.

The main conclusions from the Natsem modelling were as follows. The Treasury's results were able to be closely replicated using the Treasury's assumptions. That is, the CPI will increase by approximately 2% and none of the representative (or "cameo") households will be worse off, although in most cases middle and high income households will be proportionally better off than low income households. When assumptions (i) and (ii) are relaxed, a number of cameo households make small losses - in particular age pensioners and disability support pensioners with no private income. Similarly, when assumption (iii) is relaxed, some social security recipients and self-funded retirees are losers because the CPI effect of the tax package is almost 1% higher. The Natsem results show that the improvements in equity from exempting food from the GST can be achieved in other ways at lower cost to the budget. The modellers also submitted in the Senate hearings that the compensation to pensioners would be eroded over a short period of time in that pensions would fall relative to average weekly earnings after tax, even if they were maintained as a proportion of gross average weekly earnings. In summary, reasonable variations of the Treasury's assumptions result in some representative households being worse off under the original tax package.

There are two main objections to the modelling by Natsem and the Treasury. The first is the assumption that businesses fully and immediately pass on the GST to consumers and, similarly, that cost reductions due to removal of the WST are also fully and immediately passed on to consumers. This is unlikely. It would require extreme assumptions about the industry environment in which businesses operate.[17] It is much more likely that businesses will partially absorb the GST and the reductions in the WST, at least for some time, and therefore the consumer will not bear the full brunt of the tax changes. This has implications for the effect of the tax reform on household welfare as calculated by Natsem.

The other objection to the Natsem and Treasury modelling is that it does not account for behavioural responses by consumers and businesses to the GST. That is, it assumes that consumers do not alter their purchasing patterns across goods and services and that businesses do not alter their production patterns in response to changes in relative prices caused by the GST. This is sometimes called a "morning after" methodology. By contrast, modelling by the Melbourne Institute which received very little attention by the Senate Committee hearings, accounts for these behavioural responses. A more detailed discussion of this modelling and its results is given in Appendix A. The general point is that the "morning after" approach provides a worst case scenario of the effect of wellbeing of the GST because no allowance is made for consumers and producers to improve their situation by responding to changes in relative prices.

A tax mix change towards indirect taxes, such as that in the tax package, is often claimed to make the poor worse off on the basis that broad-based indirect taxes are, by themselves, regressive. However, a tax mix change towards indirect taxes need not be regressive. Creedy[18] has shown that there are, in principle, a large range of tax mix changes that would yield the same government revenue without making the tax system any more or less regressive. The regressive effects can be offset by targeting income tax cuts to favour low income earners more than proportionately to high income earners; and by increasing social welfare.[19] The Government has proposed both of these measures in its tax package so that, on the Treasury's assumptions, the poor will not in general be worse off in absolute terms. However, all the economic modelling, including Natsem, the Treasury, ACOSS, the Melbourne Institute and Emba,[20] show that the package is still regressive because high income earners receive a proportionally higher increase in their after-tax incomes than lower income people.

The various modelling exercises illustrate that it is impossible to be precise and certain about the distributional effects on particular households. Literally, every person will be affected differently. Also, people will be affected differently at different stages in their lives, a point not made in the Report. For example, a tax mix change may render some people worse off as young students, better off as middle age workers enjoying the benefits of the income tax cuts and perhaps worse off as retirees with less benefits of income tax cuts.[21]

The ANTS document claims: "The tax reform package will deliver substantial long-term improvements in the operation of the economy, to the benefit of all Australians. These improvements will be reflected in higher economic growth...".[22] This implies an improvement in average living standards.

The Senate Committee reports on the effects of the tax package on "living standards" without defining the term.[23] By inference, they have interpreted it as household spending power, or economic welfare. The modelling results reported by the Committee range from a fall in economic welfare of 0.03% to an increase of 0.2%.[24] This was reported to the Committee by the modellers as an insignificant figure.[25] Nevertheless the impact on economic welfare is more likely to be positive than negative.

How might a change in the tax mix toward indirect taxes affect living standards? The main mechanism is through the improvement in economic efficiency from a more uniform tax rate on goods and services than we have at present under the WST. This was discussed in the previous section. The uncertainty about the magnitude of the gains arises because we simply do not know enough about the responsiveness of saving, investment, labour supply and consumption to the changes in relative prices resulting from the tax mix change to make confident estimates of the size of the efficiency gains.[26]

The ANTS document claims benefits to employment: "the combination of higher [economic] growth and improved work incentives will deliver more jobs and lower unemployment."[27] Evidence to the Committee on the employment effects of the tax package was problematic because the economic models presented assume zero employment growth in the long run.[28] The labour market assumptions in the models are explained in more detail in Appendix B. The Murphy and Treasury models did not allow for the possibility of short run changes in employment. Hence, these two key models were agnostic on the employment effects of the package. The lack of analysis of employment effects of the tax package is a limitation of the usefulness of the economic modelling, a point made by the Labour Senators.[29]

There is at least one potential positive long run employment effect of the tax package, arising from the reduction in poverty traps resulting from relaxing means tests. Poverty traps arise when welfare benefits are targeted (or means tested) so that gains in income attract a high effective marginal tax rate consisting of the tax payable and the loss of welfare benefits. The high effective marginal tax rates reduce the incentive to work. The tax package allows welfare recipients to earn more income without having their welfare benefits withdrawn and it also has lower tax rates. For both these reasons poverty traps are reduced and this may provide a small increase in employment. Such long run effects are known as supply-side effects. They could not however be quantified by the models although the Murphy model did argue that the poverty trap effect would indeed be positive.

The Monash model was the only model to explicitly allow for short run effects on employment. In the short run potential employment gains could accrue from increases in total demand for goods and services arising from at least three sources. These are: the positive efficiency effects referred to above; the fiscal stimulus in the overall tax package (not a feature of the GST itself but of the overall package); and the boost to exports which is estimated to be between 0.68% and 6.0%.[30] These effects are known as demand-side effects. The boost to overall exports arises from the removal of some taxes on business inputs and because exports are GST-free.[31] On the other hand short run employment losses would occur to the extent that workers claim wage rises to compensate for increases in the CPI arising from the package. The latter effect is due to the increase in the cost of employing labour if nominal wages match increases in the CPI because the CPI increase is a result of the GST rather than an increase in margins of employers. In its submission the ACTU suggested that workers would bargain for nominal wage increases. Also, employment losses in the short run would occur if cuts in other indirect taxes were not quickly passed on to consumers.

The Government claims "improved work incentives" from the tax package (see above).[32] This echoes the popular claim that a tax mix switch such as that in ANTS leads to employment creation through improved incentives to work. This claim is based on the idea that lower income tax rates increase the after-tax income earned by working harder or longer. The Senate did not report theoretical or empirical evidence to either support or refute this claim. Nevertheless, the notion of improved work incentives from a tax mix switch can be debunked on theoretical grounds because higher taxes on consumption mean that an extra dollar of income, net of income tax, buys less goods and services than it did before the tax change. So that although workers have more income, net of income tax, they would not generally have more purchasing power, assuming the tax changes are revenue neutral. In that case there is not a greater incentive to work after the tax changes than before.[33] Consequently, none of the economic models, including the Treasury's analysis for the Tax Package, assume a boost to labour supply which might result from greater work incentives arising from the tax mix switch.

In summary, the evidence on employment effects (certainly in the long term) is relatively scant and somewhat contradictory, so that any predictions carry a low degree of confidence. The Senate Committee was far from any consensus about the direction and magnitude of employment effects of the package.

The potential for the tax package to affect national saving is important because higher national saving relative to investment implies a lower current account deficit which can allow the economy to grow faster. Strangely, no specific modelling of the impact on national saving was commissioned by the Senate Committee, an omission which the Labor Senators say in their report is "disturbing".[34] Nevertheless analysis by the Melbourne Institute shows a boost to private saving from improved incentives in the tax package.[35] These results were, however, not discussed by the Senate Committee.

Consider first what economic logic would suggest about the impact on national saving of a revenue neutral shift from direct to indirect taxes. Lower income tax rates on the income from saving imply a higher after-tax return on saving. The optimal response is a substitution of future consumption (by saving more from current income) for current consumption. See Benge and Albon[36] for a detailed and straightforward discussion of the supporting theory.

On the other hand, this effect may be minimal under a revenue neutral tax package. Revenue neutrality implies that taxpayers' income after both direct and indirect taxes does not increase. In this case there is no income effect — that is, no boost to saving as a result of higher income. This would imply little or no overall boost to saving according to models of saving which emphasise target saving for specific purposes (such as education and housing) and saving as a precaution or buffer against uncertainty of future income and consumption needs (see for example, Samwick).[37] Under these models it is income after-tax, both direct and indirect, that mainly determines saving, rather than opportunities for substitution between current and future consumption referred to above. Rather than substituting between current and future income, people may simply substitute between saving vehicles with little effect on the overall level of saving. For example, lower income tax rates diminish the relative tax advantages of superannuation as a saving vehicle. So that people who had been voluntarily contributing to superannuation may reduce their contributions in favour of other saving vehicles with little or no impact on their overall saving.

The net effect on total private saving depends therefore on the relative strength of the motives for saving. If saving to reach a target or buffer level is the dominant motive then there may be no net boost to private saving.[38] Otherwise, the boost to saving incentives from the substitution effect may operate to give a small boost to private saving. Because of these theoretical uncertainties, empirical research about the effect of the GST package on saving would have been especially useful.

The Melbourne Institute[39] estimates compliance costs of the current tax system (i.e. pre-tax package) for Australia are 12% of tax revenue which is the highest in the OECD and double the figure for Canada which has the second highest rate for the OECD. These high compliance costs are, the Business Coalition for Tax Reform told the Senate Committee, the central reason it supports tax reform.[40]

The Senate Committee received many submissions on compliance costs from business groups, accountancy bodies and academics. There was agreement that a single rate GST with no exemptions would minimise compliance costs from the tax package. It is also clear that compliance costs of indirect taxes are regressive because small business businesses pay more than their proportionate share of those costs.[41] The compliance costs of the GST will be particularly regressive because an estimated 1.4 million businesses, most of them small businesses,[42] will register for the GST and make monthly or quarterly GST returns. This is more than ten times more businesses than currently register for the WST.

However, there is inadequate evidence in the Report of the estimated level of compliance costs under the tax package compared with the existing level of compliance costs. This is a shortcoming of the Report if its aim is to inform the debate about whether to replace the existing tax system with ANTS. On this question, Pope[43] estimates that the average net compliance costs of a GST are between 76% and 90% lower than those of the WST. The reason is that the paper work for a GST at a single rate is quite simple for most firms. It is a three line form: GST liability on sales, less GST paid on purchased inputs backed by a GST invoice, equals the net tax liability (which can be positive or negative). However, businesses in the services sector with an annual turnover greater than $50000 and who are not currently liable for WST will be liable for GST. These businesses may face higher overall tax compliance depending on the impact of the replacement of other taxes by the GST, such as stamp duties and the Reportable Payments System.

The exemption of food would add to compliance costs. The Senate reports the finding in Warren[44] that the compliance costs of the value added tax (VAT) in the UK (which exempts food) is around 4.3% of revenue for businesses and 2.1% for the taxation authorities. This compares with estimates of the taxpayer compliance costs of the WST of about 4.7% of revenue in 1994-95.[45] The Senate states that the level of compliance costs has probably been overstated by business and that compliance costs with food exempt are unlikely to be much different from those of the current tax system.[46] However, this conclusion is based on research which does not account for cost offsets to businesses under the tax package through removal of some state and other indirect taxes. Nor does it account for cost reductions through the increasing computerisation of business accounts, a point made to the Senate by the author of the Murphy model, Chris Murphy.[47] Finally, no estimates have been made of the cost of resources used up by businesses in seeking ways to ensure that food items are classified so as to escape tax.

The Government has estimated that over the three years from 2000-2001 an additional $3.5 billion will be recovered from the cash economy and other sources of increased tax compliance.[48] This assumes a 95% compliance with the GST and an estimated size of the cash economy of $18 billion. However, the Senate Report casts doubt on this claim. The Senate found considerable disagreement over the size of the cash economy and a lack of overseas evidence for tax windfalls from black economy as a result of a GST. Estimates presented to the Senate by Treasury representatives and Professor Neil Warren of the size of the cash economy ranged from $5 billion to $18 billion (the Government's figure).[49] More importantly, the Senate heard that there is little reason to expect, even in theory, a GST to reduce tax evasion through the black economy.[50] The Melbourne Institute's analysis specifically states that there is "unlikely" to be any boost to tax revenue from the black economy.

To explain the latter point, consider a tradesperson who receives cash from households and does not declare it. It is a popular claim that under a GST such people will be forced to register with the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) if they wish to claim tax credits on inputs purchased. This will force them to declare their income so it is argued. This is a myth. The tradesperson, for example, could simply increase the price charged for the service to cover the GST paid on inputs and still not register with the ATO and therefore still not declare the income earned. The customers would probably be prepared to pay the higher prices because other services would have also increased in price and people would receive income tax cuts which would enable them to afford the higher prices. Alternatively, a registered tradesperson could offer the customer a discount in exchange for unrecorded cash payment. This applies to all service providers. Similarly, the under-reporting of cash sales by small retailers is little affected by the GST. Not all inputs purchased will be subject to GST and other inputs may be purchased on agreement between retailer and wholesaler or manufacturer that they not be declared to the tax office as either sales or purchases. The point in the latter case is that transactions can remain in the black economy with collusion by businesses along the production chain.

Another argument that is largely myth is that income from the black economy will eventually be taxed under a GST when it is spent on white economy goods and services. Kesselman[51] and Grant and King[52] develop theoretical economic models to show that this effect is small. The essential argument is as follows. Think of people who derive undeclared income from black economy activities - either legal such as home repairs, cleaning, baby-sitting – or illegal such as drug-dealing. A GST reduces the purchasing power of every extra dollar they earn because they don't get income tax cuts like people who earn income from the white economy. Therefore they will tend to put less effort into their black market activities and hence earn less income. So they will spend less on white economy goods and services than they did before the GST. The extra indirect taxes collected from their expenditure is likely to be little if any.

Hence, it is not surprising that none of the economic models assume a boost to revenue from lower tax evasion resulting from the Government's Tax Package. This does not support the Government's claim of a tax windfall from reductions in tax evasion.

The ANTS document claims that if the existing tax system were to remain "tax rates would rise"[53] because the indirect tax base would continue to shrink. The argument is that as the services sector of the economy continues to expand relative to the goods sector, it will be necessary to continue to raise WST tax rates to generate a given level of revenue as a proportion of GDP.[54] Since the GST has a broader base, capturing services, a given GST rate should generate a stable level of revenue as a share of GDP. This is not to say that the GST rate will not rise; it may do as a political decision to increase total revenue as a proportion of GDP or alter the tax mix.

Evidence to the Committee is somewhat conflicting but suggests that if an erosion of the indirect tax base is to occur it will not amount to a break down of the tax system. Some support for the Government's view comes from economic modellers, Access Economics, who point to a number of reasons to expect existing indirect taxes to fall as a proportion of GDP.[55] These include: falls in tobacco usage, improved fuel efficiency, falls in tariff rates and growth in the value of services relative to goods. Access projects Federal indirect tax collections under the current system to fall from 5.34% to 4.49% of GDP in the decade to 2008-9.[56] This amounts to a fall of $5.3 billion per year in today's dollars compared to projected 1999-2000 collections. They expect the existing State indirect taxes to fall by a smaller degree from 5.62% to 5.36% of GDP, amounting to a shortfall of $1.61 billion per year compared to 1999-2000 collections.

However, this view was not supported by results from the Monash model, presented by Professor Dixon, who argued that indirect taxes can be expected to grow slightly faster than GDP.[57] The reason is that some consumption items on which current indirect taxes are high can be expected to grow relatively fast (e.g. electronic equipment, cars and entertainment). The same applies to some intermediate goods and services (e.g. petrol, banking services and insurance). The Monash model results suggest that the present spread of indirect taxes is broad enough to increase in line with GDP in the same way as would GST revenue.

The quantitative difference between the results of Access Economics and those of the Monash model can be roughly estimated as follows. The base case forecasts of the Monash model show indirect taxes increasing in the next decade by 57% and (nominal) GDP increasing by 52%.[58] Applying Access's figure for current indirect taxes as a proportion of GDP of 5.34%, quoted above, the Monash estimates imply an increase in this ratio from 5.34% to 5.37%. This compares to Access's estimate of a fall in this ratio from 5.34% to 4.49%. The difference is 0.88% of GDP. To recoup such an amount through indirect taxes over the decade would require indirect tax rates to be approximately 9% higher at the end of the decade than they were at the start of the decade.[59] If, for example, indirect taxes were 10% at the start of the decade they would have to be raised to 19% over the ten year period, an average of 1.9% per year.

The Senate Report does not offer a consensus view on the revenue sustainability issue. However, the evidence suggests that even if Access is right and Professor Dixon is wrong, the indirect tax base is "crumbling"[60] but at a slow rate and not to such an extent as to render the current system as "ineffective".[61]

This article has examined how a GST would operate and the motivation for introducing it as the centrepiece of the Government's tax package (ANTS). The article has then evaluated the Senate Committee's contribution to settling the major controversies about the merits of replacing the existing tax system with ANTS. These controversies are about the effects on income distribution, employment, living standards, national saving, compliance costs, tax evasion and the cash economy, and revenue sustainability. Only the very broadest of findings emerge with any degree of consensus. These are as follows. The effect on overall income distribution varies across a range of quite reasonable assumptions. However, there will certainly be individual winners and losers and the package is regressive. The impact of the GST package in terms of employment and living standards is likely to be negligible. There was no consensus reached on the questions of aggregate compliance costs, tax evasion and revenue sustainability. The important question of the impact on national saving was not addressed. This article concludes that, while the Senate Committee may have raised public awareness about the issues in the tax debate, it was unable to make much progress in resolving them.

The most controversial question in the GST debate is its distributional effects. Section 4 of this article outlined a major limitation of the NATSEM and Treasury modelling of the distributional effects of the GST – namely, the so called "morning after" methodology. This Appendix discusses the modelling by the Melbourne Institute[62] which overcomes this limitation, but which received scant attention by the Senate Committee.

Consider first how household expenditure patterns might respond to the GST. Replacing the present WST with a (assume for this exercise) revenue neutral GST will decrease the relative price of some goods, such as motor vehicles, and increase the relative price of other goods, such as clothing. The "morning after" methodology takes a static snapshot by assuming that households will buy the same number of motor vehicles and clothes as they did before the tax change. This is clearly unrealistic since consumers will tend to buy more of the cheaper cars and fewer of the dearer clothes. The responsiveness of household expenditure to price changes can be estimated from knowledge of the responsiveness of household expenditure to changes in income.[63] The Melbourne Institute estimates that households can improve their wellbeing by an equivalent of about 1 percentage point of household expenditure as a result of making appropriate responses to relative price changes.[64] The implications of this for the distributional effects of the GST package are to reduce the number of households that are absolutely worse off under the GST package but to not reduce the degree of regressivity of the package.

Similarly, businesses will alter their mix of inputs in response to changes in the relative prices of inputs brought about by the GST package. They will also alter their mix of goods and services destined for export or domestic markets in response to changes in the exchange rate as an indirect result of the GST package. These responses leave business better off than they would have been had they not responded to the changes in relative prices. This has distributional implications in the same way as the welfare enhancing responses of households.

The effects on businesses and consumers interact and there are subsequent knock-on effects, the overall impact of which can only be assessed through a so-called general equilibrium model. The Melbourne Institute has used such a model to estimate the overall distributional impact of a revenue neutral replacement of selected indirect taxes with a GST. The results are given in Table A1 below.[65] The numbers show the percentage change in the economic wellbeing of households grouped in income quintiles where, for example, the lowest quintile refers to households with the lowest 20% of income. A minus number indicates a (percentage) reduction in wellbeing and a positive number indicates an improvement. The third column gives the distributional impact of the tax changes allowing for all of the responses of households and businesses to work their way through the economy. The first column is the impact under the NATSEM/Treasury modelling in which there are no behavioural responses of consumers or businesses. Comparing these two columns shows that allowing for behavioural responses improves the position of all groups but the lowest quintile is still worse off under the GST package.

|

Table A1. Measure of percentage impact on wellbeing of households by

quintile group as a result of a revenue neutral replacement of

selected indirect

taxes by a broad GST

|

|||

|

Quintile

|

NATSEM/Treasury assumption: No household or business response

|

Household response but no business response

|

Both household and business response

|

|

Lowest

|

-2.42

|

-0.34

|

-0.64

|

|

Second

|

-2.15

|

1.51

|

0.75

|

|

Third

|

0.86

|

3.85

|

1.84

|

|

Fourth

|

0.75

|

7.39

|

3.05

|

|

Highest

|

4.33

|

19.31

|

6.28

|

|

Source: Melbourne Institute, Report No. 3, p.30

|

|||

All of the economic models presented to the senate Committee, including the Treasury model which is the basis of the calculations in the ANTS document, assume that employment is fixed in the long run. That is, the GST package cannot affect employment in the long run by definition in these models. Even in the short run only the Monash model allows employment to vary. The Labour Senators remarked that:[66] "It seems extraordinary that the Treasury did not consider employment impacts to be worthy of comprehensive modelling...". This Appendix explains the reason for the labour market assumptions in these economic models.

The Treasury model, the Murphy model and the Melbourne Institute model are long run models which assume a fixed labour supply, which implies a fixed level of employment. The labour market effects of policy changes such as the GST package

are transmitted fully through changes in real wages. (This is easy to see if one imagines a labour market with a vertical labour supply curve.) This is not necessarily a major shortcoming because aggregate household incomes can be affected equally by either a change in real wages or a change in employment. The reason for the assumption stems from the accepted view that long run output and employment are determined by productivity and the quantity of available labour and capital, which are usually not regarded as policy variables.

The standard textbook analysis of fixed long run employment can be summarised as follows.[67] If the GST package stimulates aggregate demand for goods and services the result will be a higher price level which implies a lower real wage in the short run because wages are sticky in the short run. The lower real wage stimulates employment. But over time wages are revised upwards to reflect the higher price level and real wages fall toward their initial level and therefore employment falls towards its original level - hence the long run assumption of constant employment. As explained in the text, however, the Murphy model points to the potential for long run output and employment to be higher as a result of the boost to labour force participation due some alleviation of poverty traps. But the model is not able to quantify this effects.

The Monash model, on the other hand, allows for short run employment effects. It does this by specifying a short run labour supply function. The result is that in the short run both real wages and employment adjust to a policy change. The short run is implicitly set at 5 years by the choice of the value of an adjustment parameter such that the effect on aggregate employment of a policy change in year t is eliminated by year t+5.[68]

Ross Guest is a Senior Lecturer in Economics in the School of Accounting and Finance at Griffith University. His research has concentrated on empirical applications of representative agent models of optimal national saving, investment and the current account balance, with reference to Australia and South East Asia. Other research has included capital gains tax, applied financial economics and income distribution.

[1] Tax Reform: Not a New Tax, A New Tax System ("ANTS"), AGPS, Canberra, 1998.

[2] Senate Select Committee on A New Tax System, First Report (February, 1999) iv ("First Report").

[3] These committees are: the Senate Community Affairs References Committee, the Senate Employment, Workplace Relations, the Small Business and Education References Committee and the Senate Environment, Communications, Information Technology and the Arts References Committee.

[4] In the tax package, as at August 1998, the following were to be "GST-free": health, education and child care services, exports, religious services, non-commercial activities of charities and governments, local council rates, water and sewage, nursing home services and some medicines.

[5] Another term for "input-taxed" is "exempt". In the tax package, as at August 1998, most financial services and residential rents will be "input-taxed".

[6] Or five rates if the zero rate on all services, many food items and newspapers, for example, is included.

[7] In economic terminology, the price of flavoured milk is higher than the opportunity cost of the resources used up at the margin. This creates economic inefficiency because it means that at the margin insufficient resources are being allocated to flavoured milk relative to plain milk.

[8] See Melbourne Institute, Tax Reform. Equity and Efficiency (1998) 15.

[9] The effective tax rate is measured as the tax paid divided by the real (after inflation) income received.

[10] For a more detailed discussion of these distortions, see J Freebairn, "Options and Prospects for Taxation Reform" (1997) 73 (223) The Economic Record 373-386.

[11] ANTS, above n 1, 15 and Chapter 5.

[12] Senate Community Affairs References Committee.

[13] A change in the tax system is "regressive" if higher income earners are proportionally better off (or less worse off) after tax than lower income earners. A tax change is progressive if the opposite occurs.

[14] The proportional change for each income bracket under the ANTS package is given in the Natsem Report, Part Two, 3.

[15] First Report, above n 2, 59.

[16] National Centre for Social and Economic Modelling, University of Canberra.

[17] It assumes an industry environment in which businesses are "price-takers" in the markets for labour and capital and that their unit costs do not change as they increase the scale of their business.

[18] J Creedy, "Revenue and Progressivity Neutral Changes in the Tax Mix" (1992) 2nd Quarter, Australian Economic Review 31-38.

[19] The regressive effects of indirect taxes can also be offset by zero-rating necessities of such basic food items and by applying higher rates to goods with higher income elasticities (eg, luxuries). The Government plans to zero-rate some goods and services (see above) and apply a higher GST rate to luxury motor vehicles. The criticism of this approach is that it would to some extent create similar inefficiencies to those of the WST.

[20] ACOSS, The Government's Tax Package: ACOSS Analysis (1998); Emba, "Short Run Transitional Effects of the Government's Tax Plan" (1998); Melbourne Institute, above n 8.

[21] The effect on lifetime wealth of the GST may be much less than the effect on income at particular stages of the life cycle. According to the life cycle hypothesis of consumption, people plan their consumption levels according to their expected lifetime wealth and therefore tend to smooth consumption over their life cycle. Under this hypothesis, the impact on expected lifetime wealth is the appropriate welfare criterion for evaluating the GST package. However, the empirical evidence for the life cycle hypothesis is not particularly strong (see F Hayashi, Understanding Saving. Evidence from the United States and Japan (1997), for a review of the life cycle literature).

[22] ANTS, above n 1, 155.

[23] Senate Employment, Workplace Relations, Small Business and Education References Committee Report, Chapter 3.

[24] First Report, above n 2, 77.

[25] First Report, above n 2, 41.

[26] Freebairn, above n 10.

[27] ANTS, above n 1, 155.

[28] The Melbourne Institute model, though not presented in detail to the Senate Committee, also assumes zero change in employment in the long run.

[29] First Report, above n 2, 100.

[30] First Report, above n 2, 78.

[31] However, the boost to overall exports will be smaller than is often claimed because the reduction in exporters' costs will be partially offset by an appreciation of the $A. In addition, the boost to exports is limited to non-service exports, notably commodities. Service exports (such as education and tourism) will not benefit as much from the reduction in other indirect taxes which are to be replaced by the GST and will not escape the adverse effects of the appreciation of the $A.

[32] It is not clear whether they are referring to improved work incentives through reduction in poverty traps – a valid argument – or through the tax mix switch itself – a spurious argument.

[33] R Smyth, "Is it Time to Bury the Consumption Tax? Tax Mix Switch Post-Fightback!" (1994) 13 (3) Economic Papers 29-39.

[34] First Report, above n 2, 45.

[35] Melbourne Institute, above n 8, 43.

[36] M Benge and R Albon, "Saving and Taxation" in P Stemp, Saving and Policy. Proceedings of a Conference (1991) Centre for Economic Policy and Research.

[37] A Samwick, "Tax Reform and Target Saving" (1998) National Tax Journal 621-635.

[38] The other important motive for saving is to provide for retirement. Even in the case of saving for retirement people may still have a target level of saving.

[39] Melbourne Institute, above n 8, 27.

[40] Senate Select Committee on A New Tax System, Main Report, 116 ("Main Report").

[41] This point is well made by the Society of Practicing Accountants in the Main Report, ibid 119.

[42] Ibid.

[43] J Pope, "Compliance Costs of the Wholesale Sales Tax/Payroll Tax and the Proposed Goods and Services Tax" (1993) 12 (1) Economic Papers 69-77.

[44] First Report, above n 2, 89; N Warren, "Food: Staple of Life or Staple of the GST", 1998, ATAX Conference Paper.

[45] First Report, above n 2, 90; ATAX research cited in ATO publication, A Report into Taxpayer Costs of Compliance, AGPS, November 1997, 75.

[46] Ibid.

[47] First Report, above n 2, 90.

[48] ANTS, above n 1, 33 and 150 and Main Report, above n 40, 267.

[49] Main Report, above n 40, 268.

[50] Main Report, above n 40, 267-272.

[51] J Kesselman, "Evasion Effects of Changing the Tax Mix" (1993) 69 (205) The Economic Record 131-148.

[52] S Grant and S King, "The Fiscal Dividend Myth of an Income/GST Tax Switch" (1997) December Australian Economic Papers 167-178.

[53] ANTS, above n 1, 8.

[54] This assumes that other tax bases (eg, income) and rates remain stable.

[55] Cited in Main Report, above n 40, 31.

[56] Main Report, above n 40, 330.

[57] First Report, above n 2, 000199.

[58] Main Report, above n 40, Chart 10.1, 000247.

[59] I am grateful to one of the blind referees of this article for pointing this out.

[60] ANTS, above n 1, 8.

[61] Ibid.

[62] Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research, "Tax Reform. Equity and Efficiency" Reports 2 and 3 (1998) and Report 4 (1999).

[63] See J Creedy, "The Welfare Effects of Indirect Taxes in Australia", Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research Working Paper No. 6/98, University of Melbourne.

[64] Melbourne Institute, Melbourne Institute Report No. 2, 17.

[65] Adapted from Melbourne Institute, Melbourne Institute Report No.3, Table 4.4, 30.

[66] First Report, above n 2, 100.

[67] The implicit "other things held constant" assumption is invoked in such analysis, known as comparative static analysis. In this context for example, labour force growth is held constant.

[68] First Report, above n 2, 00203.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/JlATax/1999/30.html