Journal of Australian Taxation

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Journal of Australian Taxation |

|

MEDIATION IN TAX DISPUTES

By Associate Professor Richard Fayle

Traditionally income tax disputes not resolved internally proceed to either the Administrative Appeals Tribunal ("AAT") for review de novo or go on appeal to the Federal Court. The conventional process at the AAT has been to put the matter to a formal hearing if the dispute continues after the preliminary case management techniques, including compulsory conferences have been exhaust-ed. This article discusses the more recent approach of the AAT to consider cases suitable for mediation, a process provided for under the Administrative Appeals Tribunal Act (Cth) 1975 ("AATA"). The article considers the perceived comparative advantages of medi-ation as a means of resolving the dispute and the appropriateness of mediation in taxation disputes generally.

To say that only the proper amount of income tax should be collected from citizens is to simplify the Australian income tax collection system which is statute driven, entrenched in jurisprudence and both subjectively and objectively determined. In consequence, the basis of an assessment of an income tax liability can be contentious and potentially problematical.

Australia's income tax system allows for a taxpayer dissatisfied with any assessment to request the Commissioner to amend it.[2] That request must be within time, in writing and can be a formal objection.[3] The Commissioner considers all requests or objections and may allow them in whole, in part or disallow them.[4] Taxpayers still dissatisfied have two options ― to request that the Commissioner's decision be reviewed independently by the AAT or require the Commissioner to treat the objection as an appeal to the Federal Court for judicial review.[5] Fees are payable upon application to either body.

There are a number of differences between the two review processes and many factors to consider when making a decision as to which forum is the most appropriate.[6] This article does not consider these in detail. Suffice it to say that the decision is usually made on the basis of whether the dispute involves a question of law or the exercise of a discretionary power by the Commissioner, the complexity of the issue and the amount of tax involved.

The AAT reviews de novo, that is, it considers the matter afresh in the light of evidence presented. It may affirm the decision under review, vary it or set it aside making a decision in substitution or remit the matter back to the Commissioner for reconsideration in accordance with directions or recommendations.[7]

The court is concerned only with whether the decision was made according to law. In the first instance it will hear evidence but on appeal from the AAT it adopts their findings of fact unless an error of law occurred in the process.[8]

All disputes resolve in time. Resolution is reached in many ways – not always satisfactorily. A party may simply give up because they have run out of resources, or lost interest or enthusiasm or whatever. Or a matter may go through a lengthy and costly legal process culminating in a judgment. Or a dispute may settle by compromise or by consent. This article is confined to a consideration of the AAT's procedures in dispute resolution, with a focus on mediation.

Because the Commissioner of Taxation is required to observe what is termed procedural fairness (sometimes called "natural justice"),[9] so too is the AAT. The two essential notions which this embodies are firstly, that decision-makers should give a person an opportunity to be heard before a decision effecting them is made, and secondly, that the decision-maker should be impartial.[10] Of course there is an inherent difficulty with the second insofar as the Commissioner is concerned and therefore it is imperative that the AAT is independent and is seen to be so.

A taxpayer dissatisfied with the Commissioner's decision on an objection against an assessment (or more usually an amended assessment) makes an application to the AAT[11] for that objection decision to be reviewed. Then follows procedures laid down by the AATA and its regulations.[12]

Initially a conference[13] is held at which the parties identify issues. The process also has a primary objective of exploring settlement. All staff and members conducting conferences have mediation skills, which may partly explain the high rate of settlements at conferences. In 1997/98, in all jurisdictions, the Tribunal conducted 9,768 conferences, 122 formal mediations and 1,897 hearings. In the taxation division, 86% of applications were finalised without going to hearing.[14] These outcomes are driven by the conference procedure. Where settlement is unlikely then the conference considers the way forward, which includes the appropriateness of mediation. Often directions by consent are made at conferences requiring parties to file statements of facts and contentions. Usually a second conference is held to identify areas of agreement such as facts and common grounds. This focuses the issues in contention and draws out the disputed facts.

The next stage of the procedures is to submit the matter for conciliation, for mediation or go direct to a hearing.

This is a conference[15] when all formalities preparatory to a hearing have been concluded. At the conciliation conference the presiding member takes an interventionist position in an attempt to bring about a settlement. A conciliation conference may result in the presiding member expressing a view as to the likely outcome should the matter proceed to a hearing. The presiding member in this instance would take no further part in proceedings should the matter not be resolved nor would any record of the expression of opinion be retained on file so as to ensure impartiality in future proceedings. Indeed, as a rule, prior to a hearing, presiding members do not peruse conference notes to file.

Mediation was introduced into the AAT in 1991.[16] It is available at the request of the parties.[17] Essentially, mediation allows parties an opportunity to reach a decision amongst themselves and providing it is a decision open to the AAT, then the AAT will make a decision in accordance with that agreement. These procedures are discussed more fully below. It is apparent from the following table that the mediation option has not featured significantly in the Tribunal's taxation division dispute resolution procedures.

Administrative Appeals Tribunal ― Tax Division ― Key Statistics[18]

|

|

95/96

|

96/97

|

97/98

|

|

Applications

|

843

|

769

|

1282

|

|

Conferences

|

502

|

442

|

383

|

|

Mediations

|

2

|

0

|

1

|

|

Hearings

|

89

|

85

|

76

|

|

Cases Finalised

|

827

|

904

|

786

|

Indeed, mediation within the Tribunal, when compared with other means of settlement such as conferences or hearings, is not significant. In the three years to 1997/98, mediations in all divisions accounted for less than 3% of all matters.[19] Conference registrars and members consider, as a matter of practice, whether each application may lend itself to settlement by mediation, which prospect is canvassed with parties. For reasons discussed later, not every dispute lends itself to a negotiated settlement, which may explain why the mediation option is not significant in the Tribunal's processes.

When a matter has failed to settle at a conference or by mediation then, if not withdrawn by either party, it proceeds to the formal hearing stage.[20] Hearings may be conducted with little formality and the rules of evidence need not be followed strictly.[21] Hearing proceedings range from fairly adversarial, through interventionist to inquisitorial, depending on the level of sophistication of the parties. For example, when both the applicant and the respondent have legal representation then proceedings can be quite adversarial with the presiding member confining him/herself principally to procedural matters. If a party is unrepresented then the proceedings may be less formal with the presiding member intervening in managing the way evidence is brought before the Tribunal. This process demands great sensitivity on the part of the presiding member to ensure that there is neither an impression of bias nor bias in fact. Where neither party is represented by legal counsel then the presiding member may indeed take an inquistorial stance to ensure as far as possible that each party has the opportunity to bring out all material evidence. The inquisitorial stance requires a great deal more preparation on the part of the presiding member. It may involve the Tribunal in searching for relevant precedents because submissions may be relatively unsophisticated. The hearing culminates in a decision by the Tribunal.

The hearing process sets out to establish the facts and receive submissions. Usually, the decision is reserved and a written decision handed down within two months.[22] A settlement by mediation will avoid many of these procedures and will therefore probably be less costly. The Tribunal, unlike the Federal Court, is not empowered to award party to party costs in taxation matters.

What is mediation? "Mediation" has been defined as:

A structured negotiation process in which a neutral third party, the mediator, who is independent of the parties, assists the parties to agree on their own solution to their dispute, by assisting them systematically to isolate the issues in dispute, to develop options for their resolution and to reach an agreement which accommodates as much as possible the interests of all the disputants.[24]

Mediation is a form of negotiation, designed for disputants "to confer (with another) with a view to agreement."[25] Pruit et al,[26] in their 1989 study of the process of mediation in dispute resolution centres in the USA, noted that mediation tends to discourage contentious behaviour and encourages problem solving on the part of the disputants. Further, the mediator's role of following a logical series of steps to clarify issues and together with the caucus sessions,[27] tends to reduce anger detrimental to settlement negotiations. They conclude that disputant satisfaction is closely linked to perceptions of whether the mediator understood what the disputants said and that long term satisfaction is a function of their satisfaction with the way the mediation was conducted and their perception of whether all important issues were aired.

The AAT's conciliation process mentioned above is a form of "assisted negotiation" where the third party, the presiding member, coaches the applicant and the respondent into reaching an agreement. This differs from mediation where the parties, assisted by a mediator, are willingly engaged in trying to find common ground to settle. The mediator provides a formal structure for this to happen. Ordinarily in commercial mediation the parties choose the mediator but in AAT assisted mediation, the mediator is appointed by the President. However, if either party takes exception to the appointed mediator then the Tribunal would seek to appoint a member more acceptable.

Mediation involves a search for the underlying issues – the real reasons why parties are in dispute. Once these are known (at least to the mediator) then settlement is more likely. For example, in the case of a taxpayer who has objected to the level of penalties, it may become apparent that the Commissioner is not going to budge because that would be contrary to a public ruling. Also, the aggrieved taxpayer is not going to withdraw because of a perception of unfairness. Mediation may reveal that the applicant's significant concern is the perceived rudeness and accusatory stance taken by the Australian Taxation Office ("ATO") officer during a routine audit where omitted income was discovered, leading to the amended assessment with penalties. Appropriately guided negotiations at this stage can result in the ATO recognising that as an issue, acknowledging that they may have appeared too officious and offensive, although unintended, resulting in an apology which may be sufficient to resolve the dispute.[28]

The basis of settlement of disputes by mediation is often peculiar to that process and is not a basis which may have been likely should the matter have gone to hearing and been decided for the disputants. For instance, in the above example the chances are that the evidence will support the amended assessment and the decision under review will be affirmed. Whilst that is the same outcome as was achieved at mediation it is not as satisfactory, leaving the applicant bitter and aggrieved believing that they are viewed in bad light by the authorities. Such an outcome has not enhanced either party's profile even though the tax authority is within its legal rights.

Similarly, the evidence adduced at a hearing may cause the Tribunal to find that precedents support the basis of assessment and therefore, the decision under review is affirmed. However, if the matter had been mediated instead then parties may have concluded that despite precedent, it may be fairer in the circumstances to take a different view resulting in a reduced assessment acceptable to both parties. Cooperative solutions often require disputants to expand their perception of the dispute and look for creative solutions that fulfil the requirements of the parties. In tax disputes this could result in the decision under review being affirmed with a concurrent undertaking by the ATO to effect a subsequent amendment in favour of the taxpayer.[29]

Tax disputes often involve a number of taxpayers (such as members of a partnership or participants in a particular tax shelter arrangement), range over several financial years, and comprise issues varying in complexity and significance. Establishing the facts may also involve expert evidence and opinions. These kinds of complications ostensibly lend themselves to mediation if not conciliation. A mediated solution may be more satisfactory than the alternate intervention because it has been reached by the parties rather than as a result of coercion, however mild or by imposed decision.

At or before AAT formalities have reached the stage that all directions have been complied with and the matter is ready for hearing, the mediation option should be considered. In the advanced stage of proceedings each party has a fair appreciation of the other's case. This obtains because a statement of agreed facts (if any) will have been filed. Also parties may have filed a statement as to facts asserted but not agreed and an outline of each intended witness' proposed evidence as well as a statement of contentions.

Of course, not all tax disputes lend themselves to mediation. Indeed, most reported cases do not appear to have lent themselves to any form of compromise or alternate solution. A dispute about the facts, a question of veracity, a misunderstanding about the operation of the law or a belief that the law is unfair, are all examples of when mediation is not appropriate. It is not open to the Tribunal to accept an agreement by parties that a significant fact should be ignored, or to accept as fact something that clearly is not a fact, or to ignore a statutory provision.[30]

The Tribunal's mediation procedures generally follow the classical mediation process. Before commencing, parties acknowledge in writing that they have authority to settle, agree to mediate and will be bound by any decision that is reached and reduced to writing. That sets the scene. The mediator commences by setting the tone ― it may be either formal, that is, parties address each other formally, or informal where given names may be used. Parties are asked not to interrupt, to respect the right of each to speak in turn and to address each other rather than the mediator. Parties understand that they may consult privately or with the mediator at any stage of proceedings. If they speak to the mediator in private (called "caucusing") then confidentially is respected and such information cannot be divulged to the other party except by express consent of the confidant.

The mediation begins by inviting the applicant to outline their case and to advance any basis of settlement they may feel is relevant at that stage. Sometimes this may prove premature at that juncture and should be left until later. The mediator will usually summarise that opening address at its conclusion so as to reinforce it and make sure all parties have fully understood it. Those processes give the applicant an opportunity to emphasis or clarify aspects not clearly enunciated by the mediator.

Then the respondent is given the same opportunity and the mediator summarises again.

At this stage, proceedings will vary depending on what may have come out of the opening statements and the summary. In an effort to be satisfied that the issues are as reported or to explore aspects which seem to be sticking points, the mediator may call for a caucus with either or each in turn.

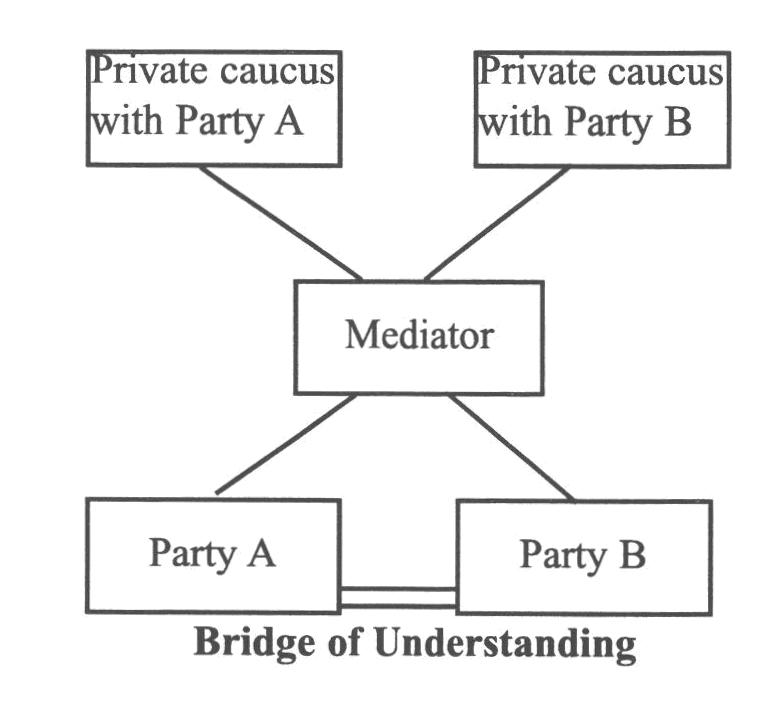

The mediator may use a white board to assist in defining pertinent issues and facts as well as summarising what may then be polarised positions being taken by parties. The mediator's main function is to assist in building bridges of understanding between the disputants. This might be depicted as above:

The basic mediation model, comprising two parties and their representatives, a mediator, open discussion, private caucusing and negotiation, lends itself to flexibility. The model can be expanded to accommodate any number of disputants. Also, if the dispute is essentially about what facts are relevant, the relative weights to be assigned to them and complexities involving expert opinion, then the process can be customised to suit.

In an adversarial forum, such as a hearing or a trial, expert witnesses for each side never exchange views or debate each other directly. Facts are elicited through evidence-in-chief, by cross-examination and reply, assisted at each stage by counsel. In mediation it is possible to have the experts meet in the presence of the parties and for them to enter into formalised discussion. This process can be particularly productive especially where the experts are members of the same profession or same professional body and subject to the same ethical rules. Whilst the process will not always result in an agreement about a contentious issue, it is likely to result in a clear indication of each disputants' strengths or weaknesses in that regard. Such a revelation tends to focus parties on the desirability to mitigate a previously entrenched position.

Examples of where this sort of mediation procedure is helpful in a taxation dispute are where the question relates to whether expenditure qualifies as research and development expenditure[31] or whether accounting principles are appropriate in deciding when an outgoing has been incurred.

The mediator has the critical role of ensuring that each witness has every opportunity to express his/her views without interruption and to rebut opposite views expressed by the expert for the other side. This may involve production of supporting evidence in the form of relevant literature, data, analyses, experiments, site visits and so on. It can be fruitful to have the parties visit the relevant location to gain a greater appreciation of the issues. Mediation is more flexible than a formal hearing and as parties have more control it may generate movement toward settlement not otherwise likely.

Mediation can be commenced at any time during proceedings. For example, a hearing may have commenced and parties may seek an adjournment to begin mediation because it has become apparent that there may be a more satisfactory way to seek to resolve the issues.

Ozaki[32] in a paper demonstrating the growth in recent years of alternative dispute resolution ("ADR"), of which mediation is the most common, responds to what is perceived as the most frequently advanced reasons for refusing to mediate. He lists the advantages of mediation over an adversarial forum such as a court or hearing. These include savings in cost and time and psychic benefits through reduced stress as well as privacy,[33] control and continuing relationships. He lists the following as commonly expressed barriers to mediation:

• strongly held opinions that the disputant is going to win;

• a desire to "make the other party pay";

• to agree to mediate is a sign of weakness;

• the opponent's request to mediate is just another ploy and delay tactic or an attempt to discover more about the other's case;

• because settlement has not been achieved due to a perception of the other's unreasonable attitude − mediation is a waste of time;

• mediation is only about compromise;

• mediation is just a further expense; and

• for the perverse, "litigation is a lot of fun"!

With the exception of the last, which defies a rational response, each of the other objections displays an inherent misunderstanding of the mediation process and its effectiveness. Mediation is simply not possible when either party enters the process in bad faith, with no intention of settling the dispute. It is a skill of the mediator to detect such an underlying attitude or hidden agenda. Some mediators insist on a private conference with each party before the mediation process, a purpose of which is to ascertain whether there exists an attitude of good faith. Such pre-mediation conferences often serve to make the opening statements superfluous and the mediation can begin with the mediator's summary for each disputant.

A tax liability is a function, or correct reflex[34] of statutory rules applied to a factual situation, and there is but one proper amount of taxable income for each taxpayer for each year of income.[35]

These parameters suggest that any disputed amount of taxable income will have a certain outcome, that is, whether the amount of assessed taxable income is correct. This implies that there is no room to negotiate.

However, because of statutory complexities, nuances in interpreting the statute, and unlimited combinations of factual situations, then certainty of outcome cannot always be easily deduced. These very uncertainties lead to dispute and to resolution by osmosis. Mediation is a tool, which, in these circumstances, complements other ways of determining an outcome.

There are though, obvious situations where mediation cannot assist. These, it seems, would display the following features:

• the applicable statutory provisions are unambiguous;

• the facts are not disputed;

• there exists a direct precedent, where the facts are on foot;

• there does not exist any conflicting decisions or judgments; and

• the outcome of the dispute is clear.

That the majority of objections against assessments are disposed of before the hearing or appeal stage might imply that they fall predominantly into the above category.[36] Nevertheless, it may be concluded that at least some of those referred to the AAT for review or those going on appeal to the Federal Court might lend themselves to resolution by mediation.

There are some issues which, by their very nature, might be resolved by mediation. A relevant attribute is a degree of subjectivity. Such may be instances where the Commissioner's discretion has been exercised (particularly penalties), or where apportionment is appropriate (with core provisions), or where the calculation of taxable income involves estimates (such as assessments pursuant to s 167 of the ITAA36 or those relating to long term contracts). Another case in point is where the aggrieved taxpayer believes they have been dealt with unfairly, rudely, accused of wrongdoing or the subject of abuse. Such taxpayers are prone to negative attitudes toward the administration, lose faith in the integrity of the taxation system or harbor feelings of anger or distrust. Mediation ought to reveal such attitudes and pave the way to heal the rift once the bridges of understanding have established the basis of misunderstandings and unintended results. Whilst the outcome may have no impact on the revenue it might affect reputations.

Australia's income tax system is complex. Inevitably there will arise disputes about the proper amount of exigible tax. These will resolve in time. The longer a dispute continues the greater the risks of damage to reputation and trust and the greater the economic and psychic costs. The adversarial system, practiced in a pure form by the courts and less formally by the AAT, has a definite role in resolving disputes. Mediation is a principal component of ADR − that is, alternative to adversarial proceedings. The mediation process is not a perfect substitute for the adversarial process nor does the opposite apply. However, there are many instances where mediation may assist in resolving the dispute more equitably, more efficiently, more economically and more satisfactorily, leaving relatively untrammeled the relationship between disputants. The effectiveness of mediation depends on the nature of the issues in dispute, the skills of the mediator and the willingness and good faith of the parties to negotiate.

Richard Fayle is an Associate Professor and Head of the Department of Accounting and Finance at the University of Western Australia. He is also a Senior Member of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal. He holds BCom and MCom degrees.

[1] The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the AAT.

[2] Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 ("ITAA36"), s 170.

[3] ITAA36, s 175A and Pt IVC, Div 3 of the Taxation Administration Act 1953 ("TAA").

[5] TAA, Pt IVC, Divs 4 and 5.

[6] See CCH 1998 Australian Master Tax Guide (1998, 29th ed) para 28-150 and R Woellner, T Vella, L Burns and S Barkoczy, Australian Taxation Law (1997, 7th ed) paras 3-515 & 3-520.

[7] AATA, s 43.

[8] See Woellner et al, above n 6, paras 3–600 to 3–610, for a discussion of this.

[9] Failure of a Commonwealth decision-maker, such as the Commissioner of Taxation, to exercise decision-making powers consistently with reasonable expectations of those affected by the decisions involves an error of law, whether described as a breach of the rules of natural justice or in failing to accord procedural fairness in the decision-making process, or by failing to carry out the duty to effect good administration. See Teoh v Minister of State for Immigration, Local Government and Ethnic Affairs [1994] FCA 1017; (1994) 32 ALD 420, 432-435.

[10] See Justice J W von Doussa, "Natural Justice in Federal Administrative Law" (1998) June AIAL Forum 1.

[11] TAA, s 14ZZ and AATA, s 29.

[12] AATA, s 33.

[13] AATA, s 34.

[14] Administrative Appeals Tribunal Annual Report 1997-1998, pp 105, 111 and 125.

[15] "Conciliation" is a term coined by the AAT. The proceedings are conducted pursuant to s 34 of the AATA. It is usually only applicable in the compensation jurisdiction where considerable medical evidence will be presented at the hearing.

[16] See J Handley, "Mediation in the Commonwealth Administrative Appeals Tribunal" (1995) Australian Dispute Resolution Journal 5, 6.

[17] AATA, s 34A.

[18] Above n 14, p 105.

[19] Ibid.

[20] AATA, s 35.

[21] AATA, s 33(b) and (c). Whilst the AAT is not bound to observe strict rules of evidence it must take care to ensure the probity of evidence upon which it establishes its findings of fact. For example, it would be a most unusual circumstance where the Tribunal relied upon hearsay evidence. On the other hand, the Tribunal will often admit evidence subject to an objection on the undertaking that it will be discerning in assessing the reliability or probity of such evidence.

[22] When an oral decision is given, either party may request a written decision within 28 days: AATA, s 43(2A).

[23] "Mediation" is not defined in the AATA. The following discussion does not attempt a review of the alternative dispute resolution ("ADR") literature and confines itself to a consideration of the basic model adopted for mediating disputes within the AAT.

[24] LEADR Mediation Workshop Course Notes, 1994 November, p 1.

[25] Concise Oxford Dictionary.

[26] DG Pruit, NB McGillivuffy, GL Welton, WR Fry, "Process of Mediation in Dispute Settlement Centers" in Kressel et al (ed), Mediation Research (1989) 368-393.

[27] The term "caucus" is given to the separate confidential discussions between either party and the mediator. Mediation "rules" insist that no disclosure of any matters discussed in caucus will be revealed to the other party without the express permission of the participating party and only in their presence. It is a fundamental aspect of mediation but not one necessarily accepted universally; Ibid 384-385.

[28] The author has been involved in just such a case.

[29] For example, the solution may involve making an adjustment in relation to an aspect of the original assessment not then part of the actual issue in dispute but resulting in a reduced taxable income notwithstanding. In these circumstances, the Tribunal could not consent pursuant to s 34A of the AATA but a decision could be reached to affirm the decision under review on the understanding between the parties that a fresh amended assessment will issue subsequently. In the author's experience, the ATO can be taken on trust in these circumstances.

[30] Clearly, s 34A(4)(c) of the AATA prohibits the Tribunal adopting any such agreement; see also Perpetual Trustee Co (Canberra) Ltd v Commissioner for ACT Revenue [1994] FCA 1150; 28 ATR 307, particularly Davies J, 311 and Wilcox J, 319.

[31] Under s 73B of the ITAA36, s 73B, which of course, is a matter decided firstly by the Industry Research and Development Board under the Research and Development Act 1986. These are decisions capable of review by the AAT.

[32] A Ozaki, "The Top Eleven Reasons for Refusing to Mediate" (1996) 7(1) LEADR Brief 3-5.

[33] Including keeping trade secrets about products or competitors and avoiding adverse publicity.

[34] See Dixon J (as he then was) in C of T (SA) v Executor Trustee & Agency Company of Australia Ltd (Garden's case) [1938] HCA 69; (1938) 63 CLR 108.

[35] B Marks, "The Proper Taxpayer in Tax Planning: Post Everett" (1981) 15 Taxation in Australia 512-534.

[36] In 1986, the ATO ceased publishing statistics relating to the number of objections lodged and how those were disposed of. Statistics available from Taxation Statistics, an annual publication of the ATO, up to the 1984-85 year show that from 1964-65 to 1971-72, less than 1% of tax assessments resulted in a formal objection. During the 15-year period up to 1984-85, the proportion grew from 1.02% to 4.04%. This period coincided with the growth in artificial tax avoidance schemes. Since that time, such schemes have been less prolific and no doubt the proportion of objections has normalised and is probably less than 1% of assessments. (See S Chapple, Aspects of Post-1986 Income Tax Dispute Resolution in Australia, an unpublished thesis, Department of Accounting and Finance, The University of Western Australia, 1997, particularly Table 2.11, p 33.)

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/JlATax/1999/9.html