Journal of Australian Taxation

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Journal of Australian Taxation |

|

THE INTERACTION BETWEEN THE GOODS AND SERVICES TAX AND THE FRINGE BENEFITS TAX

By James Leeken[*]

The Fringe Benefits Tax legislation is relatively complicated partly due to the vast number of fringe benefits that are covered and the differing treatments and valuation methods applied to each type of fringe benefit. The Goods and Services Tax, which commenced on 1 July 2000, impacts upon the taxable value and thus the tax payable on a fringe benefit. This article examines the relationship between the two taxes and, in particular, the impact of a Goods and Services Tax on certain fringe benefits.

In the lead up to the introduction of a Goods and Services Tax ("GST") on 1 July 2000, there was considerable debate as to how a GST would interact with the Fringe Benefits Tax ("FBT") regime which is currently in place. The Federal Government and Australian Taxation Office ("ATO") initially produced little comment on the subject, with the main source of information and debate coming from articles by practitioners. Recently, however, the Federal Government enacted the A New Tax System (Fringe Benefits) Act 2000 ("ANTS(FB)A")[1] which amends the Fringe Benefits Tax Assessment Act 1986 ("FBTAA"). There were also amendments to the A New Tax System (Goods and Services Tax) Act 1999 ("GSTA") to address issues raised by the interaction of GST and FBT. In addition, the ATO has released draft rulings on the subject.[2]

This article discusses the interaction between GST and FBT. Part 1 briefly discusses the Federal Government's comments on the subject and the speculation raised by these comments. Part 2 examines how a GST and FBT interact and discusses the issues raised and how they have been addressed. Part 3 provides an example of the interaction between GST and FBT, and Part 4 discusses the GST treatment of typical fringe benefits provided by an employer. A conclusion is provided in the last Part.

When the Federal Government proposed the introduction of a GST in its policy document, Tax Reform: Not A New Tax, A New Tax System, it stated that:

The FBT gross-up rate will be changed to ensure neutrality of treatment between fringe benefits and cash salary in the presence of the goods and services tax. The new gross-up rate will take effect from July 2000.[3]

The Federal Government also stated that:

Where goods and services are provided to employees as fringe benefits, the GST credit will be allowed, but Fringe Benefits Tax will be adjusted so that there will be no advantage for the employer in providing benefits rather than providing salary.[4]

At that time, there was much speculation regarding the new FBT gross-up rate and how the Government would achieve this neutrality of treatment between fringe benefits and cash salary.

Most commentators calculated the new gross-up rate to be 2.1292[5] compared with the current factor of 1.9417.[6] Further, the new gross-up rate was not expected to take into account the hidden costs involved in providing fringe benefits to employees,[7] and any value-added by the employer to the fringe benefit. The expected gross-up rate also assumed the employee was on the top marginal rate which is not always the case. These issues were already inherent in applying the previous gross-up rate and there was some speculation whether these would be addressed by the new gross-up rate.

The purpose of FBT is to tax employers on the value of certain fringe benefits that have been provided to their employees or to associates of those employees. A fringe benefit is a benefit which is provided to an employee or an associate of an employee, in respect of the employee's employment, by the employee's employer, by an associate of the employer, or by a third party under an arrangement with the employer or an associate of the employer.[8] A benefit is widely defined under the FBTAA to include any right (including any property right), privilege, service or facility.

The ANTS(FB)A has introduced a new gross-up rate of 2.1292 ("new gross-up rate").

Under the amended FBTAA, the employer is required to calculate the "type 1 aggregate fringe benefits amount". The new gross-up rate formula is then applied to this amount.

The "type 1 aggregate fringe benefits amount" is the sum of all the fringe benefits amounts in respect of which the fringe benefits are "GST-creditable benefits". The taxable values of excluded fringe benefits are included in this total.[9]

There are two categories of benefits which are treated as "GST-creditable benefits". The first is a benefit where the person who provided the benefit is or was entitled to an input tax credit under Div 111 of the GSTA.[10] Division 111 provides entitlement to an input tax credit in certain circumstances involving an employer reimbursing an employee for expenses incurred as an employee. Basically, an input tax credit is an amount allowed to offset GST included in the price that a business pays in making an acquisition or importation for use in its business.

GST group arrangements are also covered, as a benefit may also be a GST-creditable benefit where another member of the GST group, rather than the person who is providing the benefit, is entitled to an input tax credit under Div 111.

The second category of GST-creditable benefit is a benefit consisting of a:

• a thing; or

• an interest in such a thing; or

• a right over such a thing; or

• a personal right to call for or to be granted any interest in or right over such a thing; or

• a licence to use such a thing; or

• any other contractual right exercisable over or in relation to such a thing.

In addition, the thing must have been acquired or imported and the person who provided the benefit is or was entitled to an input tax credit because of the acquisition or importation.[11] A "thing" is described in the GSTA to mean anything that can be supplied or imported.[12]

Thus, where either of these two categories of GST-creditable benefits arise, the new gross-up rate will apply. The new gross-up rate, however, does not take into account the hidden costs of complying with the FBT or any value-added by the employer to the fringe benefit. Like the former gross-up rate, it also assumes the employee receiving the benefit is on the top marginal tax rate which is not always the case.

Under the FBTAA, the employer is also required to calculate the "type 2 aggregate fringe benefits amount". The former gross-up rate (1.9417) is applied to this amount ("lower gross-up rate").

An employer's "type 2 aggregate fringe benefits amount" represents the total taxable values of all other fringe benefits (including "excluded fringe benefits") that do not fall within the classification of type 1 fringe benefits. Thus, if a fringe benefit or an excluded fringe benefit is not a type 1 fringe benefit, it must be a type 2 fringe benefit. Furthermore, a type 2 fringe benefit is one where the fringe benefit provider is not entitled to an input tax credit.

Type 2 fringe benefits will generally comprise:

• benefits provided to employees between 1 April 2000 and 30 June 2000;

• benefits that are GST-free;

• benefits that represent goods or services not acquired by the employer (such as goods manufactured by the employer);

• benefits that are provided by an employer who is a small business employer who has opted not to register for GST; and

• benefits provided by an employer whose activities are input taxed.

Contributions or payments made by an employee toward the cost of a fringe benefit are excluded from the taxable value of a fringe benefit. In this way, the employer's liability to FBT is diminished. However, following the ANTS(FB)A amendments, contributions will be characterised as being the price of a taxable supply. The taxable supply being the provision of the fringe benefit. Thus, the fringe benefit provider will have a GST liability, if the employee makes a contribution. The GST is calculated as 1/11th of the price (being the contribution).

Following changes to the FBTAA, employers are required from the 1999/2000 FBT year to report fringe benefits on their employee's group certificates or withholding summary ("reportable fringe benefits"). The new gross-up rate will not affect the calculation of an employee's reportable fringe benefits amount for a year of income. An employer will continue to gross-up an employee's individual fringe benefits amount using the old gross-up rate when determining the amount to be shown on the employee's group certificate or summary. The new gross-up rate only applies to the calculation of an employer's FBT liability.

Excluded fringe benefits are those benefits which do not need to be reported on an employee's group certificate or withholding summary. They are not excluded from being part of an employer's aggregate fringe benefits amount on which the employer's ultimate FBT liability is based.

Under the amended FBTAA, the new gross-up rate will apply where the provider of a fringe benefit is entitled to an input tax credit. An employer is entitled to an input tax credit on its creditable acquisitions. An employer makes a creditable acquisition if:

(a) [the employer] acquires anything solely or partly for a creditable purpose; and

(b) the supply of the "thing" to [the employer] is a taxable supply; and

(c) [the employer provides], or is liable to provide, consideration for the supply; and

(d) [the employer] is registered, or required to be registered.[13]

An employer acquires a "thing" for a creditable purpose to the extent that the employer acquires it in carrying on the employer's enterprise. The supply of fringe benefits from an employer to its employees will generally be in the course or furtherance of that enterprise. Thus, if the supply of a benefit to the employer is a taxable supply, the employer would be entitled to an input tax credit when it supplies a fringe benefit to an employee.[14]

Generally, an entity is not entitled to an input tax credit where the acquisition made to provide a fringe benefit is of a private or domestic nature.[15] The Commissioner's view, however, is that entitlement to input tax credits associated with the provision of a fringe benefit will not be denied to a fringe benefit provider merely because the benefit is partially private or non work related in the hands of the recipient.[16] So long as the acquisition is made by the employer for the purposes of carrying on an enterprise, the fact that the employee has been supplied a fringe benefit that is for the employee's private purpose does not affect the purpose of the enterprise.

Not all fringe benefits, however, will be taxable supplies to the employer.[17] For example, a supply of health insurance will be GST-free to the employer. Thus, if an employer supplies health insurance as a fringe benefit, then the lower rate of FBT will be used as the employer is not entitled to an input tax credit. If the new FBT gross-up rate was applied to all fringe benefits, irrespective of whether the employer was entitled to an input tax credit, an increased level of FBT would be payable (due to the increased gross-up rate).

Thus, without two FBT gross-up rates, goods and services that are treated differently for GST purposes would be treated the same for FBT purposes. GST-free or input taxed goods or services that are acquired by an employer and provided as fringe benefits would be subject to FBT in the same way as other fringe benefits. However, the cost to the employer would be higher as the employer is not entitled to any input tax credits, and there may be thus an incentive to provide extra salary rather than fringe benefits.

For certain fringe benefits, the taxable value (and FBT payable) are given concessional[18] or exempt[19] treatment. In these cases, the total cost to the employer of providing these benefits is likely to be less than the cost of providing extra salary. In addition, the employer still has an advantage (cost wise) if it provides these types of fringe benefits over fringe benefits which are not exempt or concessionally treated.

Some benefits are expressly excluded as fringe benefits and do not give rise to any FBT liability.[20] These benefits have a taxable value of zero for FBT purposes and therefore a reportable fringe benefit value of zero. Some of these are payments of money and would not be treated as a supply for GST purposes.[21]

A taxable supply arises if:

(a) You make the supply for consideration; and

(b) the supply is made in the course or furtherance of an enterprise that you carry on; and

(c) the supply is connected with Australia; and

(d) you are registered or required to be registered.[22]

Where an employer provides a fringe benefit to an employee, this would normally amount to a supply as defined in the GSTA,[23] unless the fringe benefit is itself a payment of money. Supplies of money to employees (or to third parties at the employee's direction) such as expense payments and living away from home allowances, will only be supplies for the purposes of the GSTA where the employer has supplied money as consideration for money from the recipient. Further, the supply of a fringe benefit is made "for consideration" as the employee provides services in return. Thus, the requirements for a taxable supply are likely to be met,[24] and GST normally should be payable on the supply of a fringe benefit to an employee.

GST does not arise however, due to the operation of the definition of price in the GSTA.[25] Under the GSTA, in working out the value of a taxable supply being a supply that is a fringe benefit, the price is the sum of any contributions[26] made for the fringe benefit. This means that GST will not be remitted by the employer when the employer provides the benefit to the employee unless a contribution is made by the employee. If there is no employee contribution, this is similar to providing a GST-free fringe benefit to an employee.

In addition, fringe benefits provided to employees other than as a part of their remuneration package,[27] are unlikely to be a taxable supply as the provision of these unpackaged benefits are not dependent on the employee's services. That is, they can be characterised as a gift from the employer,[28] such as a gift received at a Christmas party,[29]rather than being supplied for consideration.

For comparison, the different approach taken by the New Zealand Government to the GST treatment of fringe benefits is provided in Appendix 2.

A third party can provide a fringe benefit under an arrangement with an employer or an associate of the employer. Prior to the enactment of new legislation, a third party supplying the fringe benefit to an employee may have caused a problem, as the employer would not have been entitled to an input tax credit for that supply. This is because one of the requirements for a creditable acquisition is that the supply of the "thing" to the employer must be a taxable supply.[30]

However, this would not be the case if a third party provides the benefit direct to the employee rather than to the employer. Therefore, an employer may seek to structure an arrangement so that taxable supplies are made to it rather than to the employee, so that the employer can claim an input tax credit.[31]

Where this is not possible, an employer may be able to claim an input tax credit by reimbursing the employee.[32] Under Div 111 of the GSTA, an employer is entitled to an input tax credit for reimbursing employees and their associates for expenses they incur in connection with the carrying on of the employer's business. Originally, Div 111 only applied where the employer (rather than paying the third party directly) paid the employee.[33] This restriction has been removed by amending legislation.[34] The new legislation provides for payments made by employers to third parties, on behalf of employees, to be treated as if they are reimbursements. Thus, Div 111 of the GSTA would then apply to these payments to enable the employer to claim an input tax credit.

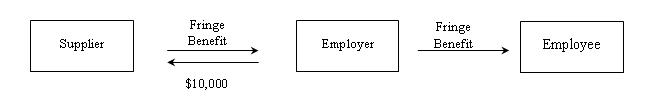

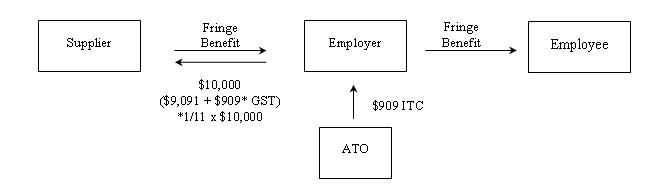

The following are simple examples showing the cost to an employer of providing a fringe benefit. The employer initially acquires the fringe benefit from a third party for $10,000.

The first example shows a fringe benefit provided before the introduction of the GST. There is only the single FBT gross-up rate of 1.9417.

Example 1

|

Employer Tax Treatment

|

|

|

Value of fringe benefit

|

$10,000

|

|

x Gross-up rate

|

x 1.9417

|

|

Grossed-up value of fringe benefit

|

$19,417

|

|

x FBT rate

|

x 48.5%

|

|

FBT

|

$9,417

|

|

|

|

|

Employee Tax Treatment

|

|

|

Extra salary received from employer

|

$19,417

|

|

x Personal tax rate

|

x 48.5%

|

|

Personal tax

|

$9,417

|

|

|

|

|

Extra salary net of tax

|

$10,000

|

|

|

|

|

Total Cost to Employer if Benefit is Given to Employee

|

|

|

Cost of purchasing benefit

|

$10,000

|

|

Plus FBT paid on benefit

|

$9,417

|

|

Total cost to employer

|

$19,417

|

|

|

|

|

Total Cost to Employer if Extra Salary is Given to Employee

|

|

|

Total cost to employer

|

$19,417

|

Thus, by grossing-up the fringe benefit value, there is no advantage for the employer in providing fringe benefits over extra salary. Both approaches cost the employer the same amount ($19,417).

Under the GST, if FBT was calculated using a single gross-up rate, the neutrality between providing fringe benefits over extra salary cannot be maintained. This is because the employer will be entitled to input-tax credits where the provision of fringe benefits is a taxable supply from the third party supplier to the employer. The following example illustrates this further.

Example 2

|

Employer Tax Treatment

|

|

|

Value of fringe benefit

|

$10,000

|

|

x Gross-up rate

|

x 1.9417

|

|

Grossed-up value of fringe benefit

|

$19,417

|

|

x FBT rate

|

x 48.5%

|

|

FBT

|

$9,417

|

|

|

|

|

Employee Tax Treatment

|

|

|

Extra salary received from employer

|

$19,417

|

|

x Personal tax rate

|

x 48.5%

|

|

Personal tax

|

$9,417

|

|

|

|

|

Extra salary net of tax

|

$10,000

|

|

|

|

|

Total Cost to Employer if Benefit is Given to Employee

|

|

|

Cost of purchasing benefit

|

$10,000

|

|

Plus FBT paid on benefit

|

$9,417

|

|

Less input tax Credit

|

($909)

|

|

Total cost to employer

|

$18,508

|

|

|

|

|

Total Cost to Employer if Extra Salary is Given to Employee

|

|

|

Total cost to employer

|

$19,417

|

Therefore, if a single gross-up rate is used of 1.9417, after the introduction of the GST there would be an advantage for the employer to obtain the fringe benefit and provide it to the employee, as the employer would be entitled to an input-tax credit of $909.[35]

However, under the amended FBTAA, the new gross-up rate (2.1292) would apply as the employer would be entitled to an input-tax credit. This would have the following effect:

|

Example 3

|

|

|

Employer Tax Treatment

|

|

|

Value of fringe benefit

|

$10,000

|

|

x New gross-up rate

|

x 2.1292

|

|

Grossed-up value of fringe benefit

|

$21,292

|

|

x FBT rate

|

x 48.5%

|

|

FBT

|

$10,326

|

|

|

|

|

Employee Tax Treatment

|

|

|

Extra salary received from employer*

|

$19,417

|

|

x Personal tax rate

|

x 48.5%

|

|

Personal tax

|

$9,417

|

|

|

|

|

Extra salary net of tax

|

$10,000

|

|

|

|

|

* The extra salary received from the employer does not change,

as the employee’s tax rate remains the same.

|

|

|

Total Cost to Employer if Benefit is Given to Employee

|

|

|

Cost of purchasing benefit

|

$10,000

|

|

Plus FBT paid on benefit

|

$10,326

|

|

Less input tax credit

|

($909)

|

|

Total cost to employer

|

$19,417

|

|

|

|

|

Total Cost to Employer if Extra Salary is Given to Employee

|

|

|

Total cost to employer

|

$19,417

|

Thus, by increasing the gross-up rate to 2.1292 there is no advantage to the employer in providing a fully taxed fringe benefit over extra salary when an employer is entitled to an input tax credit. There will still be a benefit, however, if concessional or exempt fringe benefits are provided. In addition, if the employer receives only a partial input-tax credit, the employer is likely to be worse off as the full gross-up rate (2.1292) must still be applied.[36]

The complex interaction between FBT and GST is highlighted when different types of fringe benefits are examined.

A car fringe benefit commonly arises when a car, which is owned or leased by an employer, is made available for the private use of an employee.

Under the GST legislation, full input tax credits are to be denied during the first two years of GST (fully in the first year and to the extent of 50% in the second year) on the acquisition of motor vehicles.[37] This will not apply, however, where sales tax exemption could have been claimed on the vehicle had sales tax not ended.[38] In addition, the GSTA limits the input tax credit entitlement on the creditable acquisition of a car.[39]

Thus, although an employer may only be entitled to a partial input tax credit if it acquires a car for the purposes of providing a fringe benefit to an employee, the full, new gross-up rate (2.1292) must still be applied. In addition, the provision of a car by an employer is concessionally treated for FBT purposes, with a number of different ways of determining the FBT which would apply.

An example of the GST treatment of a car fringe benefit being provided to an employee is included in Appendix 3. Given the many variables involved, the cost to an employer of providing a car fringe benefit needs to be worked out in each particular case. However, given the concessional treatment of this benefit, an employer should still have an incentive to provide a car fringe benefit over extra salary to an employee. This advantage is expected to increase with the availability of input tax credits on cars.

A debt waiver fringe benefit is the waiving or forgiving of an employee's debt. For example, if an employer who sold goods to an employee later releases the employee from paying the amount invoiced, then the employer has provided a debt waiver fringe benefit. A debt owed by an employee that is written off as a genuine bad debt, however, is not a debt waiver fringe benefit.

The employer is not entitled to an input tax credit as the employer did not acquire the fringe benefit. Therefore, the lower fringe benefit gross-up rate would apply.

For GST purposes, the provision of a debt waiver fringe benefit would be a supply by the employer, as a supply is defined to include a release from an obligation "to do anything".[40] It may be an input taxed financial supply rather than a taxable supply if the benefit can be characterised as a disposal of a debt.[41] Nevertheless, GST would not be payable by the employer, unless the employee or associate makes a contribution.[42]

A loan fringe benefit arises from a loan to an employee on which a low rate of interest (or no interest) has been charged during the FBT year.[43] low rate of interest is one that is less than the statutory rate of interest.[44]

The taxable value of a loan fringe benefit is the difference between:

• the interest that would have accrued during the tax year if the statutory interest rate had applied to the outstanding daily balance of the loan; and

• the interest (if any) which actually accrued.

For GST purposes, by lending money, the employer would be making a financial supply to the employee.[45] A financial supply is input taxed,[46] so GST is not payable on this supply. The employer would not be entitled to an input tax credit for acquisitions relating to the making of this supply, as the acquisition would not have been acquired for a creditable purpose.[47] The acquisition, however, may be taken to be acquired for a creditable purpose if a de minimis test is satisfied. That is, an employer is entitled to claim input tax credits for acquisitions that relate to making financial supplies, if the total amount of the credits that would be denied does not exceed either of the following: (i) $50,000 or (ii) 10% of the total input tax credits of the employer.[48]

|

Example 4

|

||

|

|

Scenario 1

|

Scenario 2

|

|

Loan money

|

$10,000

|

$10,000

|

|

Statutory interest rate

|

5%

|

5%

|

|

Interest rate charged by employer

|

0%

|

0%

|

|

Taxable value ($10,000 x 5%)

|

$500

|

|

|

|

$500

|

|

|

|

||

|

Total Cost to Employer if Benefit is Given to Employee

|

||

|

Interest forgone by not investing

|

$0

|

$500

|

|

FBT paid on benefit ($500 x 1.9417 x 48.5%)

|

$471

|

$471

|

|

Total cost to employer

|

$471

|

$971

|

|

|

||

|

Total Cost to Employee if Extra Salary is Paid to Employee

|

||

|

Total Cost to employer ($500 x 1.9417)

|

$971

|

$971

|

In this example, whether the employer will be better off in providing the loan or extra salary will depend on whether the loan money would have been otherwise invested by the employer. The cost to the employer is not only the loan itself but whether the money could have been put to better use (for example, earning interest) had it not been loaned to the employee.

In Scenario 1, the employer decides that it would not have invested the $10,000 had it not loaned it to the employee. Therefore, there is no opportunity cost associated with loaning the money to the employee. In this scenario, the cost to the employer of providing the $10,000 to the employee is $471. It is simply the FBT paid on the benefit provided to the employee.

The cost to the employee is different, however, if instead of providing an interest free loan of $10,000, the employee borrows money at an interest rate of 5% and the employer pays the employee an extra, after-tax salary of $500 to cover the interest bill. In this case, the cost to the employer is $971 (that is, the employer would have to pay the employee $971 for the employee to have an after-tax receipt of $500). Therefore, the employer has an incentive to provide the interest-free loan to the employee rather than paying the employee extra salary to cover the interest payable on an external loan to an employee.

In Scenario 2, the employer decides that it would have invested the $10,000 if it had not loaned it to the employee. That is, there is an opportunity cost associated with the interest-free loan to the employee. At the statutory interest rate of 5%, the employer would have earned $500 if it had invested the money. Therefore, the cost to the employer of providing an interest-free loan to the employee is $971. That is, the $471 FBT paid on the benefit to the employee plus the interest that was foregone of $500. In this scenario, the employer is indifferent between providing the $10,000 and providing the extra salary to the employee as the cost would be the same. The cost to the employer of covering the employee's interest bill on an external loan taken out by the employee would be the same as in Scenario 1, that is $971.

As the benefit is internally generated and because GST would not have been charged to the employer had it borrowed the $10,000 (the borrowing of money is input taxed), the employer would not be entitled to any input tax credits. Therefore, the lower FBT gross-up rate would apply in both scenarios.

An expense payment fringe benefit may arise in either of two ways. The first is where an employer reimburses an employee for expenses incurred by the employee. The second is where an employee pays a third party in satisfaction of expenses incurred by an employee. In either case, the expenses may be "business" expenses, private expenses or a combination of the two.

This type of fringe benefit applies only to expenses incurred by an employee that are paid or reimbursed by the employer. It does not apply to cases where goods or services are purchased by the employer and supplied to the employee.

A reimbursement or straight payment of money is excluded from being a supply under the GSTA.[49] Thus the provision of money by the employer to the employee is unlikely to be a supply or taxable supply.

Under Div 111 of the GSTA, an employer is entitled to an input tax credit for reimbursing employees and their associates for expenses they incur in connection with the carrying on of the employer's business. By allowing the input tax credit, the position should be the same as if the employer had purchased the benefit, claimed an input tax credit and supplied the benefit to the employee.

Where the employer pays a third party for expenses incurred by an employee, the employer should not be entitled to an input tax credit as the required taxable supply to the employer is lacking.[50] However, s 111-25 of the GSTA was recently introduced so that payments made by employers to third parties, on behalf of employees, are treated as if they are reimbursements.[51] Consequently, the employer normally would be entitled to an input tax credit and the new gross-up rate would apply. Therefore, the employer should be indifferent between paying a third party on behalf of employees, reimbursing employees or paying extra salary as each alternative should have the same cost.

However, the employer is only entitled to an input tax credit under Div 111 to the extent that the reimbursement is for a creditable purpose. Therefore, if the reimbursement is partly for a creditable purpose, the employer would only be entitled to a partial input tax credit, although the new gross-up rate would still apply. In this situation, the cost of providing the benefit increases as the input tax credit to which the employer is entitled decreases. Consequently, there would be a greater incentive for the employer to provide extra salary rather than the benefit because a full input tax credit is not available.[52]

If the employer is not entitled to an input tax credit, the lower gross-up rate would apply and the employer would be indifferent between providing the benefit and extra salary.

If an employee is provided with the right to use a unit of accommodation and if that unit of accommodation is the usual place of residence of the employee, then the right to use the unit of accommodation is a housing fringe benefit.[53]

The supply of a unit of residential accommodation to an employer would be an input taxed supply,[54] unless the premises are new or commercial residential premises.[55] The on-supply of the housing fringe benefit to an employee by way of lease, hire or licence is likely to be an input taxed supply.[56]

The taxable value of this fringe benefit is measured by reference to the market value of the right to occupy the unit of accommodation. Given the lack of an input tax credit entitlement to the employer, the lower gross-up rate would apply. Consequently, the cost to the employer of providing a housing fringe benefit could equal the cost of providing extra salary, and the employer may be indifferent between providing a housing fringe benefit or extra salary. This, however, would depend on the market value of the right compared with the rent actually paid. For example, a rent which is low compared with the market value of the right, would mean that the cost of providing extra salary to an employee to pay for the rent, would be lower than the cost of providing the housing fringe benefit. Therefore, the employer would have an incentive to provide extra salary in that example.

This benefit arises where employees of airlines or travel agents are provided with free or discounted air travel on a stand-by basis. The employer does not purchase this benefit from a third party, but supplies this benefit from its own business.

For GST purposes, supplies of air travel totally within Australia are generally taxable supplies. Under Sub-Div 38-K of the GSTA, however, certain supplies concerning the transporting of passengers are GST-free (eg, transport of passengers on domestic legs of international flights).[57] Nevertheless, GST will not arise on the supply of an airline transport fringe benefit from an employer to an employee or associate.[58] Furthermore, as the employer is not entitled to an input tax credit since it has not made an acquisition, the lower gross-up rate applies.

The taxable value of the fringe benefit is the stand-by value less the employee contribution (if any). The stand-by value is 37.5% of the lowest published fare for that route.

|

Example 5

|

|

|

Lowest published fare

|

$10,000

|

|

Taxable value (stand-by value)

|

$3,750

|

|

|

|

|

Total Cost to Employer if Benefit is Given to Employee

|

|

|

Stand-by value

|

$3,750

|

|

Plus FBT paid on benefit ($3,750 x 1.9417 x 48.5%)

|

$3,531

|

|

Less input tax Credit

|

$0

|

|

Total cost to employer

|

$7,281

|

|

|

|

|

Total Cost to Employer if Extra Salary is Paid to Employee

|

|

|

Total cost to employer

($10,000 x 1.9417)

|

$19,417

|

Therefore, because the stand-by value is well below the lowest published fare for that route, the employer would have an incentive to provide the airline transport fringe benefit rather than extra salary. The employer does not receive an input-tax credit directly in relation to the benefit (as the benefit is not acquired but internally created from its business), therefore the lower gross-up rate applies. However, the employer is entitled to input tax credits for creditable acquisitions which relate to making this benefit, for example, on fuel and aircraft, which would further reduce the cost of supplying this fringe benefit. In addition, the actual cost to the employer of providing the benefit is likely to be lower than the cost of providing extra salary, as the stand-by value for fringe benefits purposes may not reflect the true cost of providing the benefit to the employee.[59]

The provision of a meal is a board fringe benefit if an employee is entitled to the provision of accommodation and certain conditions are satisfied, including that the meal is prepared and supplied on the employer's premises or work site.[60] For example, meals provided in a dining facility located on a remote construction site, oil rig or ship.[61]

Under s 38-2 of the GSTA, a supply of food is GST-free. A supply under s 38-2 will be taxable, however, if it is a supply of food for consumption on the premises from which it is supplied.[62] GST will not arise, however, on the provision of the fringe benefit to an employee.[63]

The taxable value of board fringe benefits is currently $2.00 per meal per person.[64] This is likely to be much less than the purchase price of an equivalent meal. Therefore, the employer would have an incentive to provide the benefit over extra salary.

There is no category of entertainment fringe benefit as such. However, employers have the option of valuing some forms of entertainment as meal entertainment fringe benefits. Meal entertainment fringe benefits are fringe benefits provided by way of (or in connection with) food or drink.[65]

The supply of some foods and drinks are GST-free while others are taxable. Therefore, an employer would be entitled to receive input tax credits in respect of certain foods and drinks[66] and the higher gross-up rate would apply. The lower gross-up rate would apply where the employer is not entitled to receive input tax credits in respect to the acquisition of the fringe benefit.

The taxable value of a meal entertainment fringe benefit can be calculated using the 50-50 split method or the 12-week register method. Under the 50-50 split method the taxable value is 50% of the employer's total meal entertainment expenditure. The 12-week register method is based on the total meal entertainment expenditure and an appropriate percentage as evident from the 12-week register. Given the concessional nature of this benefit, an employer would have an incentive to provide the benefit over extra salary.

This benefit generally arises when an employer provides car parking facilities for an employee at or near his or her place of employment and there is a commercial car parking station available for all-day parking within a one kilometre radius of the premises on which the car is parked.

For GST purposes, the supply of this right to park by an employer would normally be a taxable supply. However, due to the definition of price in the GSTA,[67] GST does not arise unless the employee makes a contribution.

A car parking fringe benefit is a concessional fringe benefit. There are currently five ways in which the taxable value of a fringe benefit can be calculated.[68] Depending on the method chosen, the employer may have an incentive to provide the benefit over extra salary.

A property fringe benefit arises when an employer provides an employee with property (free or at a discount).[69] Concessions are available in the calculation of the taxable value of property fringe benefits.

Depending on the property involved, the employer may be entitled to an input tax credit and thus the higher gross-up rate may apply. Furthermore, it is likely that an employer would have an incentive to provide a property fringe benefit over extra salary, due to the concessional treatment of this fringe benefit.

Any fringe benefit that is not the subject of any of the above categories is called a residual fringe benefit. For example, a residual fringe benefit could include the provision of services (eg travel) and the use of property. It would also include health insurance coverage under a group policy taken out by an employer for the benefit of employees.

Input tax credits may be available to the employer depending on the type of fringe benefit involved, so the higher gross-up rate may apply. In addition, residual fringe benefits are also concessionally valued. Consequently, an employer is likely to have an incentive to provide a property fringe benefit over extra salary.

It is apparent that the interaction between GST and FBT is quite complex. The enormous range of fringe benefits available and the various valuation methods which can be used depending on the benefit involved, simply highlight the difficulties and the depth of analysis that is required in comprehending FBT. Once the impact of GST is added, with its possible alternatives within the definition of taxable supply and creditable acquisition, the situation becomes even more complicated.

Increasing the FBT gross-up rate to take into account GST will only ensure neutrality of treatment between fringe benefits and cash salary in certain scenarios. That is, where the fringe benefit provider is entitled to a full input tax credit, where the employee is on the top marginal rate of personal income tax (48.5%) and where concessional treatment does not apply to the fringe benefit. Where the circumstances are different, for example, where concessional treatment applies to the fringe benefit, or where the employer is only entitled to a partial input tax credit, the new gross-up rate will not ensure neutrality of treatment between fringe benefits and extra cash salary. In addition, given the concessional treatment of most types of fringe benefits, there will usually be an incentive for an employer to provide fringe benefits over extra salary.

Exempt Benefits

Benefits that are exempt from FBT have a taxable value of zero and therefore a reportable fringe benefit value of zero. Exempt benefits include the following:

▪ protective clothing;

▪ laptop and portable computers (one per employee per year);

▪ briefcase;

▪ tools of trade;

▪ subscriptions to trade and professional journals;

▪ airport lounge memberships;

▪ business related software;

▪ electronic dairies and calculators;

▪ corporate credit card and membership fees;

▪ car and mobile phones (where private use is minimal);

▪ single journey taxi travel beginning or ending at the place of work (regardless of time of travel);

▪ taxi fares when an employee is sent home sick;

▪ child care at on-site employer provided childcare facilities;

▪ morning and afternoon teas (in house);

▪ free or discounted commuter transport provided by public transportation bodies for their staff;

▪ travel cost of an employee or potential employee for the purpose of attending job interviews and selection tests;

▪ work instigated relocation costs;

▪ benefits provided under workers' compensation law;

▪ remote area housing provided by a primary producer;

▪ car parking provided by small business employers;

▪ minor fringe benefits (taxable value less than $100);

▪ frequent flyer program rewards (where the employee has a membership in the program).

Excluded Fringe Benefits

The main exclusions under the definition of "fringe benefit" in section 136(1) are:

▪ salary or wages;

▪ most superannuation fund contributions;

▪ payments from certain superannuation funds;

▪ benefits under employee share schemes;

▪ payments on termination of employment;

▪ capital payments for enforceable contracts in restraint of trade;

▪ capital payments for personal injury;

▪ payments deemed to be dividend for income tax purposes;

▪ certain payments to associated persons.

The New Zealand Approach

The interaction between GST and FBT is treated differently in New Zealand in two main respects. In New Zealand:

1. provision of a fringe benefit to an employee is treated as a deemed supply; and

2. here is no gross-up required to obtain the taxable value of a fringe benefit.

The deemed supply is calculated as the taxable amount for FBT, less:

▪ any benefits provided which are zero-rated or exempt from GST, such as loans, superannuation, life insurance;

▪ usage in the course of making exempt supplies, for example, a landlord supplying a car to an employee to collect domestic rents.

Types of fringe benefits not included for GST purposes are:

▪ low interest loans (exempt supply);

▪ other financial services;

▪ international travel (zero-rated);

▪ retirement allowances, gratuities, redundancy payments, lump sum bonuses.

Example - Provision of Car Fringe Benefit

An employee is provided with the use of a company c r which the employer originally purchased for $30,000, including all accessories and sales tax. This makes the total cost (or base value) $30,000.

The car travels 16,000 km a year, so the statutory fraction for FBT purposes is 20%. The vehicle is held for the full fringe benefits tax year, and there are no recipient (employee) contributions.

|

Purchase price of car

|

$30, 000

|

|

x Statutory fraction

|

0.20

|

|

x Number of days car is held

|

365

|

|

Number of days in FBT year

|

365

|

|

Less recipient contribution

|

0

|

|

Taxable value

|

$6, 000

|

|

|

|

|

Total Cost to Employer If Benefit is Provided to Employee

|

|

|

FBT paid on benefit

($6, 000 x 1.9417 x 48.5%)

|

$5, 650

|

|

Less input tax credit

|

$0

|

|

Total cost to employer

|

$5, 650

|

0% pre 1 July 2001; 50% between 1 July 2001 and 30 June 2002; 100% from 1 July 2002. The car is assumed to be purchased before 1 July 2001. The employer is therefore not entitled to an input tax credit and the lower gross-up rate applies.

Where the employer provides a car fringe benefit, the employee is provided only with the use of the car (rather than ownership). Instead of providing a car fringe benefit, however, the employer may decide to provide extra salary to cover the cost to the employee of obtaining the use of a car (eg, by renting a similar car). The breakeven point would be $5,650 (extra gross salary). That is, the cost to the employer of providing the car fringe benefit or $5,650 extra salary to the employee is the same.

This equates to an after tax amount for the employee of $2,910 ($5,650 - (48.5% x $5,650)). Thus, if the cost to the employee of obtaining the use of a similar car is more than $2,910 per annum, the cost to the employer of providing extra salary to the employee (to cover this cost) would be more than providing the car fringe benefit. Thus, depending on the cost of acquiring the use of the car, the employer may have an advantage (cost wise) in providing the car fringe benefit over extra salary.

James Leeken is currently a Tax Manager at KPMG. He previously worked as a Solicitor at Baker & McKenzie advising on GST and stamp duty issues and as a Tax Consultant with Ernst & Young's Indirect Tax Division. He is a member of the Law Society of New South Wales and also a Certified Practicing Accountant.

[*] This article is adapted from a paper submitted as part of the coursework for the University of Sydney's Master of Laws subject, "Goods and Services Tax". The author gratefully acknowledges comments made by the course presenter Justice Graham Hill. A summary of this paper was published in the CCH GST Newsletter. A number of legislative changes have since occurred.

[1] The ANTS(FB)A received Royal Assent on 30 May 2000.

[2] GST Ruling GSTR 2000/D17 and Taxation Ruling TR 2000/D8.

[3] Treasurer, Tax Reform: Not a New Tax, A New Tax System (August 1998) 50.

[4] Ibid 91.

[5] Depending on the assumptions that are made, other practitioners and academics calculated the new gross-up rate to be in the region of 2.3.

[6] Therefore, a $1,000 benefit, which is provided, will be grossed up to $2,129 and the FBT payable would be $1,032.57. There would therefore be an increase in the total cost of providing the benefit of $90.70 (9.65%) compared with using the current FBT gross-up rate.

[7] For example, the new requirements to report fringe benefits on group certificates would place an additional burden on the employer in terms of compliance costs. Thus, in the lead up to the GST and after it is introduced, the cost of providing benefits to employees will almost certainly increase.

[8] FBTAA, s 148. For simplicity, this paper will refer to fringe benefits provided by employers to employees.

[9] Excluded fringe benefits are certain benefits which are not included in the employee's reportable fringe benefits amount that is disclosed on the employee's group certificate or withholding summary.

[10] A benefit is also a GST-creditable benefit if a person who is or was a member of the same GST group as the person who provided the benefit is entitled to an input tax credit under Div 111.

[11] A benefit is also a GST-creditable benefit if a person who is or was a member of the same GST group as the person who provided the benefit is or was entitled to an input tax credit.

[14] Assuming the other requirements of GSTA, s 11-5 are met.

[16] GST Ruling GSTR 2000/D17.

[17] For example, the employer may not be entitled to an input tax credit because it is not registered or required to be registered.

[18] Benefits subject to concessional FBT are: motor vehicles; discounts on in-house products; living away from home allowance; entertainment (business related); car parking; employee share and option plans (< $1,000 per employee) and off-site child care. In each case, the taxable value is benefit specific.

[19] A list of exempt fringe benefits is provided at Appendix 1.

[20] A list of excluded benefits is provided at Appendix 1.

[21] GSTA, s 9-10(2).

[22] GSTA, s 9-5.

[23] The definition of "supply" is quite broad and includes "any form of supply whatsoever": GSTA, s 9-10.

[24] Presuming the other requirements of GSTA, s 9-5 are satisfied.

[26] Specifically, recipient's payment and recipient's contribution, which are defined in the GSTA and the FBTAA.

[27] For example, entertainment.

[28] The supply, however, may still be a taxable supply if made to an associate: GSTA, Div 72.

[29] Subject to FBT thresholds.

[31] It should make no difference whether a third party provides an input-taxed GST-free benefit direct to an employee or to the employer as in both cases, the employer would not be entitled to an input tax credit.

[32] GSTA, Div 111.

[33] For example, for a law firm to be entitled to claim an input tax credit, a lawyer would pay for the renewal of a practising certificate and then be reimbursed by the law firm, rather than the firm paying the law society on behalf of the lawyer.

[35] If the supply from employer to employee was a taxable supply however (ie before GSTA, s 9-75(3) was introduced), the GST payable would be an extra cost to the employer.

[36] GSTA, Div 71 may operate to deny an input tax credit in relation to an acquisition or importation that solely or partly relates to the making of a financial supply. If the input tax credit is denied, then the lower the FBT gross-up rate would apply.

[37] A New Tax System (Goods and Services Tax Transition) Act 1999, s 20.

[38] Ibid, s 20(4)(c).

[39] GSTA, s 69-10. For the 1998 income year, the car depreciation limit was $55,134.

[41] A New Tax System (Goods and Services Tax) Regulations 1999, rs 40-5.09 and 40-5.09 (item 2) includes a disposal of a debt as a financial supply. "Disposal" is defined in regulation 40-5.04 as including "cancellation". Therefore, a debt that is waived may be characterised as a cancelled debt.

[42] See the discussion at Part 3.5 above.

[43] The use of the term "loan" is quite broad. For example, if an employee owes a debt to an employer but the employer does not enforce payment after the debt becomes due, then the unpaid amount is treated as a loan to the employee. Such a loan commences immediately after the due date at the rate of interest, if any, that accrues on the unpaid amount. When an employer releases an employee from the obligation to repay the loan, a debt waiver fringe benefit may arise.

[44] The statutory interest rate is set by reference to the standard variable rate for owner-occupied housing loans of the major banks.

[45] A New Tax System (Goods and Services Tax) Regulations 1999, rs 40-5.09 and 40-5.09 (Item 2) includes the provision of a debt as a financial supply.

[46] GSTA, s 40-5(1), 9-30(2).

[47] As the acquisitions relate to making input taxed supplies: GSTA, s 11-15(2).

[48] GSTA, s 11-15(4) and Div 189.

[49] Unless the money is provided as consideration for a supply that is a supply of money: GSTA, s 9-10(4).

[50] GSTA, s 11-5. For example, for a law firm to be entitled to claim an input tax credit, a lawyer would pay for the renewal of a practising certificate and then be reimbursed by the law firm, rather than the firm paying the law society on behalf of the lawyer.

[51] Section 111-25 was inserted by the Indirect Tax Legislation Amendment Act 2000.

[52] GSTA, Div 71 may operate to deny an input tax credit in relation to an acquisition or importation that solely or partly relates to the making of a financial supply. If the input tax credit is denied, then the lower FBT gross-up rate would apply.

[53] A unit of accommodation includes a house, flat or apartment; accommodation in a hotel, motel, guesthouse, bunkhouse or other living quarters; a caravan or mobile home; or accommodation in a ship or other floating structure.

[54] GSTA, s 40-65 covers a sale of residential premises. Section 40-70 deals with long-term leases.

[55] GSTA, ss 40-65(2) and 40-70(2).

[56] GSTA, s 40-35 deals with residential rent.

[58] Due to the operation of the definition of price in GSTA, s 9-75(3). However, GST will arise if the employee makes a contribution.

[59] For example, an empty seat may cost the same whether or not it is filled (apart from the meal cost).

[60] Other conditions include: there is an entitlement to at least two meals a day; and the employer supplies the meal.

[61] Meals provided at a party, social function or in a dining facility open to the public (except for board meals provided to employees of a restaurant, etc) are not board fringe benefits. Such meals may be property fringe benefits.

[63] Refer to above, n 56.

[64] Incidental refreshments such as morning and afternoon teas supplied as part of board are exempt from FBT. Thus, the employer would be better off providing incidental refreshments over extra salary.

[65] For example, the provision of entertainment by way of food or drink; or accommodation or travel in connection with, or to facilitate the provision of, such entertainment; or the payment or reimbursement of expenses incurred in obtaining something covered by the point above.

[66] Also with respect to services such as catering.

[67] GSTA, s 9-75(3).

[68] The five ways are 1) the commercial parking station method; 2) the market value method; 3) the average cost method; 4) the 12-week register method; and 5) the statutory formula method.

[69] For FBT purposes, property includes all goods, including gas, electricity and animals; real property such as land and buildings; and choses in action such as shares or bonds.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/JlATax/2000/19.html