Journal of Australian Taxation

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Journal of Australian Taxation |

|

THE PAYG INSTALMENT SYSTEM: UNWARRANTED EXTENSIONS?

By Rodney Fisher

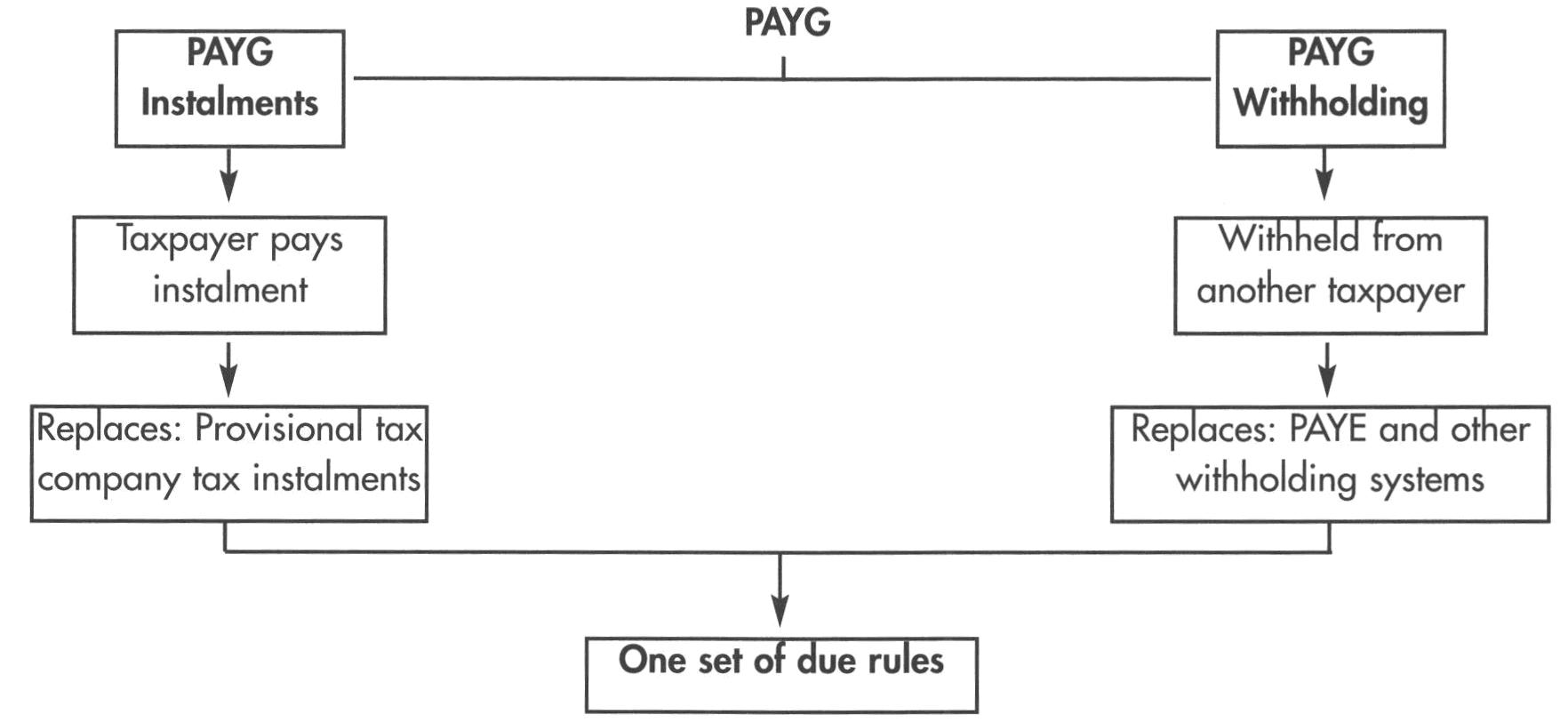

One of the more significant changes in the administration of tax law has been the introduction from 1 July 2000 of the PAYG regime to replace a range of other collection mechanisms. The PAYG system comprises an instalment system and withholding system. This paper outlines the operation of the PAYG instalment system, reviewing the options available to taxpayers, and illustrating the calculation of quarterly instalment payments under the regime. The paper also examines the extension of the PAYG instalment system in regard to the collection of tax instalments from partnerships and trusts, raising the issue as to whether there are grounds for such an extension in the scope of the operation of the system.

One aspect of the tax reform proposals announced in August 1998 involved the introduction of a new all-embracing tax collection system which would replace the plethora of tax collection mechanisms then in operation. The first of the new Pay As You Go (PAYG) legislative provisions were introduced in A New Tax System (Taxation Laws Amendment) Bill No 1 1999 on 30 June 1999, with the stated key objective being to reduce business tax compliance costs by:

• aligning payment dates for the various taxes that business taxpayers pay;

• allowing business taxpayers to make just one payment per quarter; and

• combining the existing tax withholding systems into a single system.[1]

The new PAYG system comprises two sub-systems, bringing together the previous withholding and remittance systems and tax instalments systems.

This article is concerned only with the PAYG instalment system which operated from 1 July 2000. In the first part of this paper, the functional aspects of the PAYG instalment system are outlined, illustrating the intended operation of the collection system. The second part of this paper examines the extension of the collection mechanism into new areas and the efficacy of applying an instalment collection system to non-taxpaying entities.

This first part of the paper outlines the operation of the system as it applies to taxpaying entities.

The provisions governing the operation of the PAYG instalment regime are contained in Sch 1, Pt 2-1 of the Taxation Administration Act 1953 ("TAA"). In referring to the role of the regime, the legislation provides that the purpose of the operative Parts is that taxpayers are "... required to pay amounts of their income at regular intervals as it is earned during the year".[2]

The operative provision imposes a liability to pay instalments if the Commissioner has issued an instalment rate, with no liability for instalments if no instalment rate has been given.[3]

There are three possible types of instalments:

• quarterly instalments based on an instalment rate;[4]

quarterly instalments based on GDP-adjusted notional tax;[5] or

annual instalments.[6]

The first is the default method to apply when a taxpayer has made no choice to use an alternative method.

The liability to pay instalments only arises if the Commissioner has issued an instalment rate, with the instalment rate to be used in determining the instalment amount being either of:[7]

• the rate given by the Commissioner; or

• an instalment rate chosen by the taxpayer.[8]

The instalment liability for a quarter is calculated under s 45-110(1) of the TAA as:

applicable instalment rate x instalment income for the quarter

An example illustrating the calculation of the instalment amount is given below as each of the components are discussed.

If the instalment rate given by the Commissioner is used, there is no necessity for a taxpayer to determine the instalment rate, which may be just as well given the complexity in the description of the calculation of the instalment rate.

Each of the components in this calculation deserves some explanation.

Instalment Income

"Instalment income" is examined first as the determination of the instalment rate is dependent on the concept of instalment income.

Instalment income for a period is defined[9] to include the ordinary income derived during the period to the extent that it is assessable income of the income year which includes that period. Statutory income is not included in instalment income except for:

• eligible ADFs (Approved Deposit-taking Funds);

▪ eligible superannuation funds; and

▪ eligible superannuation trusts.

Also excluded from instalment income are amounts from which a withholding amount is withheld under the PAYG withholding system.

Ordinary income for these purposes is gross ordinary income, examples being gross sales, fees for service, interest paid or credited to a bank account, gross rent, dividends (excluding imputation credit) paid or applied on behalf of a taxpayer, and royalties.[10] The requirement that ordinary income be assessable income ensures that instalments are not payable on exempt or non-assessable amounts. By limiting ordinary income to that part which is assessable income in the year in which it is derived, instalments are not paid on income from other periods.

Instalment Rate

Unless taxpayers choose to use their own instalment rates, the rate given by the Commissioner may be used. This rate is calculated as:[11]

base assessable instalment income x 100

notional tax

"Base assessable instalment income" is so much of the assessable income calculated for the purposes of the base assessment, as the Commissioner determines to be instalment income for the base year.[12] Base assessment is generally the latest assessment for the most recent income year for which an assessment has been made, or the latest return information from which an assessment for that income year would have been made.[13] The "base year" is the income year to which the base assessment relates.[14]

By incorporating the definition of instalment income above, base assessable instalment income for an individual is broadly so much of assessable income as is gross ordinary assessable income derived during the previous income year, and which has not been subject to the PAYG withholding measures.

Assume a taxpayer with no dependants has the following details:

|

|

Previous Income Year

|

Current Income Year (1st quarter)

|

|

|

$

|

$

|

|

Salary income

|

55,000

|

15,000

|

|

Investment income

|

15,000

|

5,000

|

|

Net capital gain

|

2,000

|

1,000

|

|

Assessable income

|

72,000

|

21,000

|

|

Deductions: c/f loss

|

1,000

|

|

|

- other

|

7,000*

|

2,000

|

|

Total deductions

|

8,000

|

2,000

|

|

Taxable income

|

64,000

|

19,000

|

|

Tax payable

|

20,682

|

|

|

Rebates: private health

|

400

|

|

|

Net tax

* $6000 relates to salaries

|

20,282

|

|

|

Base assessment (previous) year:

|

|

|

|

Base assessable instalment income

|

= $72,000 - $2,000 (NCG) - $55,000 (PAYG withholding)

|

|

|

|

= $15,000

|

|

When advising an instalment rate, the Commissioner must also advise the notional tax used in calculating the instalment rate.[15]

"Notional tax" is the adjusted tax on adjusted taxable income, less adjusted tax on adjusted withholding income. In this way the notional tax relates only to instalment income, and not to income subject to PAYG withholding.

Adjusted taxable income[16] for the base year is calculated in the same way as taxable income, being assessable income less deductions for the base year, as adjusted by:

• excluding net capital gains from assessable income; and

• excluding current tax losses from deductions, but including carry-forward tax losses with deductions.

From the figures above:

Adjusted taxable income

= $64,000 - $2,000 (NCG) + $1,000 (c/f loss)

= $63,000

Adjusted withholding income[17] for the base year is assessable income for the base year from which withholding payments are made under PAYG withholding, less deductions which reasonably relate to this income.

Continuing the example:

Adjusted withholding income

= $55,000 - $6,000 (deductions relating to PAYG withholding income)

= $49,000

The calculation of adjusted tax for both adjusted taxable income and adjustable withholding income follows the same procedure. The steps involved are:[18]

• calculating income tax payable, disregarding tax offsets for:

o private health insurance;

• calculating Medicare levy payable;

o low income rebate; and

o superannuation contribution for spouse;

• calculating HECS debt;

• adding the above amounts, and subtracting any family tax benefit.

From the figures above, to calculate adjusted tax on adjusted taxable income:

|

Tax on $63,000

|

|

|

(no private health rebate)

|

$20,212

|

|

Medicare 1.5% x $63,000

|

$945

|

|

HECS

|

0

|

|

Total

|

$21,157

|

Adjusted tax on adjusted withholding income:

|

Tax on $49,000

|

|

|

(no private health rebate)

|

$13,972

|

|

Medicare 1.5% x $49,000

|

$735

|

|

HECS

|

0

|

|

Total

|

$14,707

|

From the adjusted tax amounts on adjusted taxable income and adjusted withholding income, the notional tax is calculated. This figure is the tax notionally attributable to the instalment income or income not subject to the PAYG withholding regime.

Notional tax = (adjusted tax on adjustable taxable income) - (adjusted tax on adjusted withholding income)

= $21,157 - $14,707

= $6,450

By determining the adjusted tax amounts for adjusted taxable income and adjusted withholding income and then taking the difference, rather than determining the tax payable on the difference between these income amounts, the Commissioner ensures that the tax free threshold is only applied once and there is no advantage to the taxpayer.

While notional tax is calculated by reference to adjusted taxable income, the instalment rate based on notional tax is expressed as a percentage of assessable instalment income. This is calculated as follows:

notional tax                    x

100

base assessment instalment income

= 6,450 x 100

15,000

= 43%

This rate can then be applied to determine the instalment amount:

Instalment income

= $21,000 - $1,000 (NCG) - $15,000 (PAYG withholding)

=$5,000

Instalment amount = applicable instalment rate x instalment income for period

= $5,000 x 43%

= $2,150

Where a taxpayer considers that the instalment rate given by the Commissioner does not adequately reflect the expected tax liability for the year, the taxpayer is free to choose an instalment rate and use this rate for the remaining instalment quarters for the current year.[19] When changing to a new lower rate, the taxpayer is able to claim a credit adjustment for the overpayment of quarterly instalments already made in the income year at the higher Commissioner's rate.

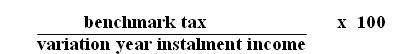

The potential downside when selecting a varied instalment rate is that where the varied rate is less than 85% of the calculated benchmark instalment rate for the income year, the taxpayer is liable to general interest charges on the shortfall.[20]

The "benchmark instalment rate" is calculated as:[21]

The "variation year instalment income" is so much of the assessable income for the income year as the Commissioner determines is instalment income for that year, that is, in broad terms, the assessable income which is gross ordinary income not subject to PAYG withholding.

"Benchmark tax" is defined[22] as adjusted assessed tax calculated in respect of the adjusted assessed taxable income, which is broadly the taxable income reduced by net capital gains.[23] This benchmark tax is reduced by the amount of credits for amounts withheld under the PAYG withholding regime, thus ensuring that the figures used in determining any penalty are reduced to reflect the credits for PAYG withholding amounts.

Determination of adjusted assessed tax on the adjusted assessed taxable income basically follows the same procedure as calculation of adjusted tax outlined above, involving:

• calculating income tax payable, disregarding tax offsets for:

• private health insurance;

• low income rebate; and

• superannuation contribution for spouse;

• calculating Medicare levy payable on adjusted assessed taxable income;

• calculating HECS debt;

• adding the above amounts and subtracting any family tax benefit.

With the benchmark instalment rate determine, the variation of the taxpayer's instalment rate from this will determine if any penalty is to apply.

In place of using the instalment rate, an individual can choose to pay quarterly instalments on the basis of GDP adjusted notional tax if, at the end of the first instalment quarter for the year:

• the individual is not registered or required to be registered for GST;

• the individual is not a partner in a partnership that is registered or required to be registered for GST; and

• the individual's most recent notional tax was $8,000 or more.

• The quarterly instalment amount for these taxpayers will be either:

• an amount notified by the Commissioner; or

• an instalment amount calculated on the basis of benchmark tax.

The instalment amount notified by the Commissioner for each quarter will be 25% of the GDP adjusted notional tax,[24] which is calculated using the same method as was used for calculating notional tax, except that both the adjusted taxable income and adjusted withholding income are increased by a factor of (1 + GDP adjustment)[25] The GDP adjustment is the percentage change in GDP over the last year.

An individual calculating their own instalment amount is required to calculate their estimate of benchmark tax, as outlined above, with 25% of this amount becoming payable in each quarter

The third option available to taxpayers is for annual rather than quarterly instalments[26] This option is not restricted to individuals, and conditions to be met are that:

▪ the entity is not registered or required to be registered for GST;

▪ the entity is not a partner in a partnership that is registered or required to be registered for GST;

▪ the most recent notional tax was less than $8,000; and

▪ if the entity is a company:

o the company is not a participant in a GST joint venture; and

o the company is not part of an instalment group.

An instalment group in broad terms consists of a holding company with majority control of subsidiaries.[27]

Taxpayers choosing to pay an annual instalment can determine the instalment amount as:

▪ the calculation from the formula:

Commissioner's instalment rate x instalment income for the instalment year;

▪ the most recent notional tax notified by the Commissioner; or

▪ the estimate of benchmark tax for the income year.[28]

With the latter two choices, if the instalment is less than 85% of the benchmark tax for the income year, the taxpayer is liable to a penalty under the general interest charge.[29]

As noted earlier in the paper, the PAYG instalment system replaces the provisional tax collection system for individuals and the tax instalment system for companies. It is instructive to note some of the divergences in application between the existing and new regimes.

For individuals, provisional tax applied broadly when the taxpayer had significant investment income or salary income from which no PAYE instalments were deducted. In general terms, provisional tax was calculated by reference to the previous years taxable income subject to an uplift factor, with certain adjustments made. By contrast, PAYG instalments are calculated by reference to instalment income, which, in broad terms as seen above, is gross ordinary income which is assessable income not subject to the PAYG withholding regime. This suggests that PAYG instalments will be based on assessable income prior to any deductions, whereas provisional tax was based on taxable income, being assessable income reduced by deductions. It may be argued that the PAYG instalment is a better reflection of the instalment amount due, as taxable income used to calculate provisional tax may have also included income which had been subject to PAYE deductions. However, where the bulk of the income is from sources not subject to PAYG withholding, such as investment income, the instalments collected from the PAYG system will be greater than those collected under the provisional tax system. This is because under the PAYG instalment system there is no benefit gained from deductions until the end of the income year.

Companies face a similar dilemma. Company tax instalments were calculated by reference to taxable income of the company, but PAYG instalments will be determined by reference to gross ordinary income which is assessable as no income of the company will be subject to PAYG withholding. For companies, there is then a double effect. Not only are they required to pay instalments up to one year ahead of when they would have done so under the old regime, but the instalment amounts will be greater as there is no benefit from deductions until the end of the income year.

The details above outline the broad operation of the PAYG instalment system for taxpaying entities. However, the regime seeks to broaden the scope for collection of tax instalments by suggesting that an entity can have instalment income even if it is not liable to pay tax instalments.[30] Such an approach appears to be in broad accord with other legislative provisions which deem entities not liable to pay tax to have the equivalent of a taxable income.[31]

However, it is suggested that while the determination of taxable income at the end of an income year may be a warranted convenience for partnerships and trusts in that it allows determination of assessable amounts for partners and beneficiaries, there are difficulties which arise when attempting to collect tax instalments from partners and beneficiaries prior to the end of the income year.

The remainder of this paper outlines the extension of the PAYG instalment system to partnerships and trusts, and some of the difficulties which appear to arise in attempting to fit the regime to these non-taxable entities.

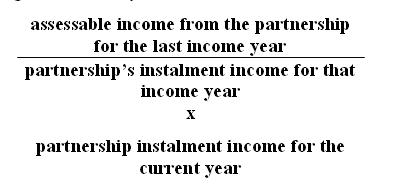

The PAYG instalment system requires that the instalment income of a taxpayer include an amount from any partnerships in which the taxpayer is a partner, the amount to be included being determined by the formula:

Assessable income from the partnership is so much of the individual's interest in partnership net income as was included by s 92 of ITAA36 in the partner's assessable income for the most recent income year. A partnership's instalment income for the income year is so much of the partnership's assessable income as falls within the definition of instalment income, being broadly assessable income which is ordinary income. If the ratio cannot be determined, a partner may still be required to include in instalment income an amount that is fair and reasonable,[32] having regard to:

▪ the extent of the interest in the partnership during the current period;

▪ the partnership instalment income during the current period; and

▪ any other relevant circumstance.

The intention of the rule is to require partners to include in their instalment income for an instalment quarter their share of partnership income for the period, the rationale being to "recognise that partners derive partnership income throughout the income year and not just at the time when partnership accounts are struck[33]".

While it is understandable that the Commissioner would be desirous of having partners include a share of partnership income with instalment income, it may be that this is an area of potential difficulty. The difficulty arguably lies with the timing of the determination of the income of the partnership.

To include the share of partnership income in the instalment income of a partner requires the determination of partnership instalment income for that instalment quarter, which requires the determination of partnership assessable income. This requires determination of assessable income of a partnership at the end of each instalment quarter. It is suggested that therein may lie the difficulty.

Instalment income of a partnership is the assessable income of the partnership which is instalment income, which itself is broadly ordinary assessable income. By including a share of the partnership instalment (assessable) income in the partner's instalment income, the Commissioner's contention appears to be that partnership assessable income is derived throughout the year. This contention appears to conflict with current authority, which suggests that partnership net income is only derived when the partnership accounts are struck at the end of the income year.

The question as to the timing of derivation of partnership income was at issue in FC of T v Galland,[34] when the Commissioner argued unsuccessfully for the proposition that partnership income was derived throughout the year and not just when the accounts were struck at year end. In the words of Mason and Wilson JJ,

The Commissioner's principal submission ... is that partners, like individual taxpayers, derive income when they can sue for it, so that they derive income for the purposes of the Act before the accounts of the partnership are prepared for the year of income and the amount of distribution to each partner is ascertained ... This submission cannot be sustained. Section 92(1)(a) of the Act includes in the assessable income of a partner, not his share of the gross income derived, but his individual interest in the net income of the partnership for the year of income.[35]

In discussing the concept of net income, Brennan J, as he then was, noted that:

The net income of a year of income is not the aggregate of net incomes derived during the intermediate periods of the year: the net income of the year of income is a single amount ascertained for the whole year on a basis appropriate for the particular partnership business.[36]

Net income for a partnership is determined broadly by subtracting deductions from assessable income of the partnership, treating the partnership as if it was a separate entity. Given that net income of the partnership is a single amount determined for the whole year, it may be argued that the components of net income, being assessable income of the partnership and deductions of the partnership, are also single amounts determined for the whole year and not determined progressively throughout the year.

This view would appear to be supported by Brennan J when suggesting that the approach to ascertaining net income of a partnership was a process whereby:

... the whole of the assessable income of the year must be aggregated and from that sum the aggregate of the deductions allowable conformably with s 90 must be deducted.[37]

Dawson J saw profits and net income of a partnership as conceptually the same thing, and while recognising that the Commissioner argued that derivation of income by partners from partnership profits extended over the year, found that:

... for tax purposes the net income (or profit) of a partnership ... is to be calculated by reference to a year of income, that is to say, on an annual basis.[38]

If net income of a partnership can only be determined on the taking of partnership accounts on an annual basis, then it may be suggested that partnership assessable income and partnership deductions also can only be determined on this same annual basis.

If this is accepted, then partnership instalment income, effectively being the assessable income of the partnership, cannot be determined until partnership accounts are taken at year end. If a partnership does not determine the partnership assessable income until the taking of accounts at the end of the income year, then arguably there is no partnership assessable income to which can be applied the partner's ratio and thus no instalment income for the partner.

If it is accepted that a partnership does not earn income throughout the year, then the new provisions themselves will not require instalments to be made. Schedule 1, s 6-1 of the TAA requires regular payments from taxpayers from income only as it is earned, so until income is earned, no instalments will be required.

It could be argued by the Commissioner that in effect the new system is no different from the provisional tax system which applied to partners and arguably in effect taxed the current years partnership income. However, that system was based on the previous years taxable income, subject to an uplift factor and other adjustments, and made no pretensions that it was taxing partnership assessable income as it was earned in the current year.

As noted earlier, the PAYG instalment system applies to the instalment income of the partnership allocated to a partner. Instalment income in broad terms is gross ordinary income which is assessable, being determined without taking into account deductions.

This calculation is in contrast with the determination of partnership net income[39] at year end, which allows for deductions, this partnership net income being the amount from which the partners' shares are determined.[40] On this basis, the Commissioner is seeking to allocate to partners during the year a gross amount, this being the amount on which the PAYG instalment is payable, with a net amount being allocated at the end of the year.

The expectation would be that the instalment amounts during the year would accordingly be higher, with deductions only becoming relevant to the calculation at year end. These higher PAYG instalments during the year have the potential to create cashflow consequences for partners.

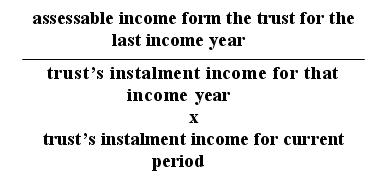

Subdivision 45-I of Sch 1 of the TAA provides special rules for trusts under the PAYG instalment system, the basic provision requiring that a taxpayer's instalment income should include an amount for each trust of which they are a beneficiary at any time during the current year, the amount to include being:[41]

Whilst not defined, the trust's instalment income for the income year will be so much of the trust's assessable income as satisfies the definition of instalment income, being broadly ordinary income which is assessable.[42]

Assessable income from the trust for the last income year is the beneficiary's share of trust net income which was included in the beneficiary's assessable income, excluding amounts from capital gains made by the trust. If this formula cannot be determined, then instalment income will include an amount which is fair and reasonable having regard to:[43]

▪ the extent of the taxpayer's interest in the trust, and the income of the trust, during the current

▪ period;

▪ the trust's instalment income for the current period; and

▪ any other relevant circumstance.

Determination of a fair and reasonable amount would be required where, for example, the beneficiary had not been a beneficiary of the trust in the previous income year.

Where in the previous income year the trustee was required to pay tax on behalf of a beneficiary presently entitled but under a legal disability,[44] or because there was no beneficiary presently entitled, then these PAYG instalment provisions will apply to the trustee.[45]

Further measures relating to trusts were introduced by A New Tax System (Tax Administration) Bill (No 2) 1999, which inserted Subdiv 45-N into the TAA. These provisions relate to PAYG instalments to be made by trustees, with trustees being treated as single-rate trustees or multi-rate trustees.

Single rate trustees are trustees of corporate unit trusts, public trading trusts, superannuation funds, ADFs, and pooled superannuation trusts. For single rate trustees, the provisions treat the net income of the trust as being the taxable income of the trustee for the purposes of calculating the instalment rate, benchmark instalment rate, and benchmark rate for the trustee.

Multi-rate trustees are those who may have several separate liabilities to make PAYG instalments. This will arise when the trustee has had to pay tax in the previous income year in respect of beneficiaries[46] and for trust net income for which no beneficiary was presently entitled.[47] In broad terms, the system will work in the same way for a trustee as for other taxpayers, except that the calculations in each case are based on either a single beneficiary's share of the trust net income, or an amount being trust net income to which no beneficiary is presently entitled. In determining the PAYG instalment in respect of each separate liability the trustee may use the Commissioner's instalment rate, vary the instalment rate, or elect for annual PAYG instalments, with different choices being able to be made in respect of each separate liability.

There would appear to be two potential problem areas with these requirements.

It is well established that trust income for trust law purposes, and net income of a trust for taxation law purposes, are two discrete concepts. Trust income takes the ordinary common law meaning of income, and represents the distributable income of the trust[48] calculated in accordance with accepted accounting principles. Net income for tax purposes is defined in s 95 of ITAA36, and basically represents the taxable income of the trust calculated as if the trust was a taxpayer in its own right, being assessable income less deductions, with some exceptions.

The differences between the "distributable income" and "taxable income" of a trust are a result of the different components of each, and timing differences in recognising expenses for accounting purposes and deductions for tax purposes.

Both concepts of trust (distributable) income and net (taxable) income are referred to in the taxing provisions, with beneficiaries who are entitled to a share of trust income being required to include that share of net income in their assessable income.[49] While no guidance is provided in the legislation as to the application of the sections in terms of whether the share of net income is to be a proportion or an absolute value, the better view is that the proportional approach is the correct approach.[50]

It is suggested that the concept of instalment income, being a gross amount, is more akin to the concept of trust income than it is to the notion of trust net income. While instalment income only includes gross ordinary income which is assessable, it takes no account of deductions, which are taken into account in determining trust net income. By using instalment income as the basis for PAYG instalments it appears that the Commissioner is seeking to base the PAYG tax instalments on a gross amount, and is thereby arguably diverging from the legislative provisions whereby tax liability is assessed on trust net income, being an amount net of deductions.

Application of the PAYG instalment regime would arguably result in higher instalments being paid throughout the year, as deductions only become relevant to the calculation in determining trust net income at the end of the income year. The calculation of instalments on the gross instalment income, rather than an amount net of deductions, has potential cashflow consequences for beneficiaries and trustees liable to pay PAYG instalments.

The other issue of concern is that many trusts are created as discretionary trusts to take advantage of the flexibility offered by this structure. In these trusts there can be no certainty as to the manner of the distribution of trust income until the trustee exercises their discretion in determining the distribution, which will generally be expected at the end of the financial year. Until this time there can be no certainty as to the amount of a distribution, or even that there will be any distribution, to any particular beneficiary.

If the Commissioner seeks to have beneficiaries remit instalments throughout the year, there can be no certainty that beneficiaries remitting instalments will receive any distribution, or that beneficiaries who do receive a distribution will have remitted any tax instalments.

Given this uncertainty as to distributions, it is arguably unreasonable for the Commissioner to require tax instalments from any potential beneficiary of a discretionary trust in an income year until the beneficiary knows what distribution they will receive, at which time their tax liability will be determinable.

It may be argued that with the introduction of entity taxation this problem will no longer exist, but for the period until entity taxation applies, the PAYG instalment system will be the operative system.

There can be little argument that the concept and intention underlying the PAYG system, being the simplification of collection, is a laudable objective and one with which most taxpayers would concur.

The PAYG instalment component, replacing both provisional tax for individuals and company quarterly instalments, has the potential to remove the bias which favoured the corporate structure, by removing the deferral advantage in company tax instalments and the uplift factor which applied to provisional tax for individuals. This bias resulted in over-collection of provisional tax and insufficient collection of company tax.

By determining the instalment for each quarter from the instalment income for the quarter, the PAYG instalment system also has the potential to alleviate cashflow problems which could arise when the tax instalment due bore no relation to the income derived in that period.

However, as suggested there would appear to be some anomalies in the regime.

Instalment income is defined by reference to gross ordinary income which is assessable income, and as instalment income is the basis for calculation of tax instalments, no account of deductions would appear to be taken until the end of the income year. This in itself has potential cashflow consequences when the instalments are based on the gross amount of assessable income, rather than on taxable income.

It is also suggested that there are difficulties in the attempt to extend the regime to include partnerships and trusts. While it is understandable that the Commissioner would be desirous of collecting tax instalments from partners and beneficiaries throughout the income year, it may be that the approach may raise further questions. The effectiveness of these measures remains to be seen.

Rodney Fisher is a Senior Lecturer in the Faculty of Business and Law at Central Queensland University and a Barrister. He has published on a range of topics in several taxation journals.

[1] See the Explanatory Memorandum to the A New Tax System (Taxation Laws Amendment) Bill No 1 1999.

[2] TAA, Sch 1, s 6-1.

[3] TAA, Sch 1, s 45-15.

[4] TAA, Sch 1, s 45-110.

[5] TAA, Sch 1, s 45-112.

[6] TAA, Sch 1, s 45-115

[7] TAA, Sch 1, s 45-110(2).

[8] TAA, Sch 1, s 45-110(2)

[9] TAA, Sch 1, s 45-120.

[10] See the Explanatory Memorandum to the A New Tax System (Taxation Laws Amendment) Bill No 1 1999.

[11] TAA, Sch 1, s 45-320(1).

[12] TAA, Sch 1, s 45-320(2).

[13] TAA, Sch 1, s 45-320(3).

[14] TAA, Sch 1, s 45-320(4).

[15] TAA, Sch 1, s 45-320(5).

[16] TAA, Sch 1, s 45-330.

[17] TAA, Sch 1, s 45-335.

[18] TAA, Sch 1, s 45-340.

[19] TAA, Sch 1, s 45-205

[20] TAA, Sch 1, s 45-230.

[21] TAA, Sch 1, s 45-360.

[22] TAA, Sch 1, s 45-365.

[23] TAA, Sch 1, s 45-370.

[24] TAA, Sch 1, s 45-400.

[25] TAA, Sch 1, s 45-405.

[26] TAA, Sch 1, s 45-140.

[27] TAA, Sch 1, s 45-145.

[28] TAA, Sch 1, s 45-115.

[29] TAA, Sch 1, s 45-235.

[30] TAA, Sch 1, s 45-120(6).

[31] Such as Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 ("ITAA36"), s 90 for partnership net income and s 95 for trust net income.

[33] See the Explanatory Memorandum to the A New Tax System (Taxation Laws Amendment) Bill No 1 1999.

[34] 86 ATC 4885.

[35] 86 ATC 4885, 4887.

[36] 86 ATC 4885, 4890.

[37] Ibid.

[38] 86 ATC 4885, 4893.

[39] ITAA36, s 90.

[40] ITAA36, s 92.

[41] TAA, Sch 1, s 45-280.

[42] See the Explanatory Memorandum to the A New Tax System (Taxation Laws Amendment) Bill No 1 1999.

[43] TAA, Sch 1, s 45-20(3).

[44] ITAA36, s 98.

[45] ITAA36, ss 99 and 99A.

[46] Under ITAA36, s 98(1).

[47] Under ITAA36, ss 99 & 99A.

[48] Zeta Force Pty Ltd v FC of T 98 ATC 4681, 4683-4684 (per Sundberg J).

[49] ITAA36, ss 97 and 98.

[50] See for example Davis & Anor v FC of T 89 ATC 4377; Zeta Force Pty Ltd v FC of T 98 ATC 4681; and FC of T v Prestige Motors Pty Ltd 98 ATC 4241 in which the Full Court commented adversely in relation to the hybrid approach adopted (albeit obiter dicta) in Richardson v FC of T 97 ATC 5098.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/JlATax/2000/21.html