Journal of Australian Taxation

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Journal of Australian Taxation |

|

TAX REFORM IN AUSTRALIA: IMPACTS OF TAX COMPLIANCE COSTS ON SMALL BUSINESS[*]

By Binh Tran-Nam[**] and John Glover[***]

The article explores the Ralph Review’s assumption that the unfavourable effect of tax reforms on small business has been adequately counterbalanced by reduced taxation compliance costs. Research suggests that, even after off-setting benefits, compliance costs associated with tax reform continue to be regressive for small business. Further “fine-tuning” of tax legislation will be necessary if effectively simplified and reduced small business compliance costs are to be achieved.

The decade of the 1980s was a time of substantial tax reform. Both developed and developing countries moved towards lower tax rates, base broadening, and increased neutrality and uniformity in tax structures.[1] Few peace-time reforms have had equivalent objectives and characteristics. Market outcomes, wealth maximisation and “small government” policies were promoted. Largely conservative political agenda were implemented with multi-party consensuses.[2] The United States’ Tax Reform Act of 1986 is an example. Described in Congress as “the most significant tax reform legislation in the history of the federal income tax”,[3] the Act was introduced by a Republican administration and passed into law with the assistance of a Democratic majority.[4]

Australian developments do not share all the characteristics of tax reform elsewhere. Limited direct reforms, income tax base-broadening and self-assessment were introduced by the centralist Labor party, following the National Tax Summit in July 1985.[5] More systematic and far-reaching tax reform was not proposed until 1998 – in a manifesto of the conservative Howard Government entitled Tax Reform – Not a New Tax, A New Tax System (“ANTS”). This document recommended a number of reforms in line with international precedents and was part of the platform upon which the Howard government was re-elected in that year. The Wholesale Sales Tax (“WST”) and some State taxes were replaced with a broad-based consumption tax, known as the Goods and Services Tax (“GST”) and the income tax base was further broadened. An Australian Business Number for enterprises, a Simplified Tax System (“STS”) for small businesses and Pay-As-You-Go tax collections for businesses and individuals were introduced, in addition to proposals for a wide-ranging review of the business tax system.

The Review of Business Taxation, chaired by Mr John Ralph (“the Review”), submitted its report to the Treasury in October 1999. Several of its recommendations have now passed into law. These include discounting the rate of capital gains tax payable by individuals, freezing the indexation of capital gains and reducing the corporate tax rate from 33% to 30%. Accelerated rates of depreciation were phased out. New methods for valuation of trading stock and a simplified tax system for small business were introduced. Other recommendations are still outstanding.

These reforms, together, have had a significant adverse impact on many small business taxpayers. This should come as no surprise. The Review’s final report anticipated that both the GST and the Review’s recommendations would apply unfavourably to this sector of the economy.[6] It was noted that taxpayers trading as sole proprietors, or as partnerships not taxed as companies, were likely to obtain few advantages and incur several onerous responsibilities under the Ralph reforms and the GST.[7]

One outcome that was not permitted, however, was discrimination against small businesses. Both the Review’s Terms of Reference and its stated objectives provided that the net effect of changes to the tax system was to be neutral between large and small business sectors of the economy.[8] Principles of fairness and “equal sacrifice” require that appropriate compensation be made for changes to the system which impact differently on business taxpayers according to their scale.[9]

Tax simplification was a recurring theme of tax reform in the 1980s and both the ANTS document and the Review’s final report in Australia cited it as a major rationale.[10]

The report proposed to counterbalance tax changes which were unfavourable to small businesses through the introduction of small systemic changes of the simplifying kind. A “compliance dividend” would “level the playing field” and re-establish neutrality between large and small business sectors of the economy.[11] In large part, as will be noted, the small business “compliance dividend” in the report was associated with uptake of the STS.

The Review’s success in simplifying the business tax system and achieving a “compliance cost dividend” has been challenged by tax academics and small business organisations. So far the debate has focused on the validity of the government’s approach in using tax compliance costs to measure the simplification impacts of tax reform.[12] Quantitative estimates of the change in tax compliance costs have to date largely been speculative. Data is mainly based on overseas experience or information collected prior to introduction of the GST on 1 July 2000.

The principal aim of this article is to make a preliminary, empirical assessment of the compliance cost impacts of tax reform on Australia’s small business sector. Assumptions about the small business “compliance dividend” will come into focus, accordingly. The article is the first publication pursuant to an ongoing project funded by a three-year Australian Research Council Strategic Partnership with Industry – Research and Training (“SPIRT”) scheme grant. The project is motivated by several considerations. First, the small business sector is vital to the domestic economy in terms of its power to generate employment and economic expansion. At the same time, as is well known, small businesses tend to bear a disproportionate burden of tax compliance costs.[13] Secondly, the project is expected to identify specific focus points which may assist the government in fine tuning or improving reform initiatives. Thirdly, current Australian tax reform affords a rare opportunity to collect and analyse the empirical evidence of tax simplification in the economy. A major contribution to international compliance costs literature may be the result. The present article, representing the first stage of the project, focuses on the transitional costs of the GST – although comments on other aspects of the reform will be made whenever appropriate. It should be emphasised from the outset that the article takes an explicitly small business, not a wider social or community perspective.

Organisation of the article is as follows. Part 2 discusses a number of conceptual issues of relevance to the discussion. “Small business” is defined, together with the relevant concept of tax compliance costs and theoretical framework for evaluating the simplification impact of tax reform. Part 3 briefly reviews earlier estimates of the transitional compliance costs of the GST. In part 4, the methodology of this article is explained and justified. Part 5 describes and discusses the preliminary data, both qualitative and quantitative, obtained from the study and draws broad implications. A final part lists the main findings of the project to date.

A business is traditionally regarded as small if it has some of the following organisational or management characteristics:

• it is independently owned and operated;

• it is closely controlled by owners/managers who also contribute most, if not all of the working capital; and

• principal decision-making functions rest with the owners/managers.[14]

Characteristics such as these are inherently problematic. For functional purposes, they are often qualified with a size component – usually the number of employees that a business has, or the size of its turnover.[15] The Australian Bureau of Statistics (“ABS”) defines small businesses in terms of employment. A non-agricultural, private sector business is small if it is either a non-manufacturing business employing less than 20 employees, or manufacturing business employing less than 100 employees. About 95.9% of total non-agricultural businesses are small pursuant to this definition.[16] However, the employment size definition is not used by the ABS for the agricultural sector. Instead, a measure called the Estimated Value of Agricultural Operations (“EVAO”) has been developed, to reflect the area of crops sown, the number of livestock and crops produced/livestock sales during a given year. Some 88% of all private sector agricultural businesses are accordingly said to be small.[17]

The Review, following the Australian Taxation Office (“ATO”), used a definition of small business based on turnover.[18] Businesses with an annual turnover or receipts of less than $1 million, exclusive of GST, are to be eligible to be taxed under the STS as small businesses. Over 96% of businesses (representing over 1,075,000 businesses in 1999-2000) are said to have an annual turnover of less than $1 million.[19] In order to facilitate critical comparisons and analysis of the Review, this article will adopt the same turnover definition of small business as the Review. In any case, the ABS employment definition has a comparable sample range.[20]

There is an important distinction between “legal” and “economic” simplicity. Legal simplicity refers to the ease with which tax legislation can be comprehended and applied. Economic simplicity refers to the cost of complying with tax legislation. The two concepts may or may not be consistent. A GST law, for example, may be legally simpler than a WST law, whilst compliance with a WST is less costly in aggregate terms – because it affects a far smaller number of taxpayers. In this sense, the relationship between legal simplicity and economic simplicity is analogous to that between income tax progression and tax progressivity.[21] Legal simplicity assesses taxes by the concepts which are internal to the system. Economic simplicity assesses taxes by their wider social effects.

Measurement of economic simplicity usually encompasses legal simplicity. Determinants of effective simplicity of a particular tax include:

• legal simplicity;

• the number of taxpayers and tax administrators;

• the size distribution of taxpayers;

• business cycle (changing macroeconomic economic conditions affect the tax base); and

• tax cultures.[22]

Distinction between legal simplicity and economic simplicity is not merely made for pedagogic reasons. It draws attention to the fact that the Review focused almost exclusively on tax legislation and legal simplicity under the heading of “compliance costs” and had little regard for the economically significant interaction between tax legislation and taxpayers.[23] This article advances a definition of economic simplicity in order to capture and evaluate these other impacts of tax reform accordingly.

Tax compliance costs will be taken to refer to the value of resources expended by taxpayers in complying with the requirements of the tax system. These include:

• time spent by business proprietors and their unpaid helpers on business tax affairs;

• cost of employing internal staff (account clerks/accountants, programmers, etc) doing tax work;

• cost of external tax advisers; and

• non-labour costs (computer hardware, tax software, specific travel, etc).

Small business structure will refer to the character of the legal person operating the business enterprise, which may differ from the entity owning business properties.

Measurement of tax compliance costs is not without controversy. In the area of business compliance costs, it is difficult to distinguish between costs attributable to accounting and costs attributable to taxation. At one end of the spectrum, some taxpayers (especially small businesses) regard all costs involved in the preparation of accounting records as tax compliance costs. At the other extreme, provision for tax liabilities is viewed by others as little more than a by-product of normal business accounting. This article adopts an intermediate position. It assumes that appropriate questions can be directed to taxation compliance costs which are distinct from non-taxation accounting costs.

Compliance costs are sometimes divided into computational and tax planning costs. This distinction, first made in the literature by Johnston,[24] has engendered a controversy which still persists. Many tax lawyers and policy-makers continue to insist that computational costs are the only legitimate measure of tax compliance costs. Tax planning is treated as an avoidable or voluntary activity. Yet it is impossible to fully distinguish activities and costs related to tax planning from those related to satisfying the compliance demands of the tax system. Inevitably, the line between avoidable and unavoidable costs is blurred.

Another relevant issue for this article concerns the distinction between social compliance costs (to the economy) and taxpayer compliance costs (directly borne by taxpayers).[25] This distinction arises because tax compliance activities undertaken by business taxpayers sometimes generate offsetting benefits. These may include:

• tax deductibility benefits (eg, many compliance costs are tax deductible);

• cash flow benefits (eg, use of tax revenues before they are sent to the ATO); and

• managerial benefits (eg, improved business decision-making brought about by the need to have stringent record keeping in order to comply with tax laws).

This article takes an explicitly business perspective. It examines taxpayer compliance costs, benefits and burdens at taxpayer level. Wider social compliance costs and evaluation of the simplification impacts of tax reform from a public policy point of view will not be considered.

Another distinction needs to be drawn, of relevance to the simplification impact of the tax reform. Transitional and recurrent compliance costs must be separated. The literature on tax operating costs distinguishes a number of compliance cost categories.[26] These include:

• commencement (or start-up) costs;

• temporary costs; and

• recurrent (or regular) costs.

Typically, a “commencement cost” might include the expense of initial training of staff to deal with a proposed tax change. A “temporary cost” might be the value of additional time required by staff over a period extending after a change commences in order for them to comply and become familiar with new regulations. “Recurrent costs” will correspondingly equal the time that staff take to comply with tax changes with which they are familiar. The term “transitional costs”, in this article, includes both commencement and temporary costs. Aggregating commencement and temporary costs is primarily for expedience - although the step can be justified in cases where the new tax can be learned reasonably quickly.

Implementation costs of the GST introduced on 1 July 2000 generated considerable interest in both academic and business communities. Wide-ranging prospective (rather than actual) estimates of the transitional compliance costs of the GST have been made. Some of these are listed in Table 1. Together they provide an insight into the perceived start-up paperwork burdens imposed by GST. Only start-up (one-off) compliance costs of the GST are referred to. No explicit efforts were made to examine the temporary compliance costs of the GST.

Table 1: Prospective Estimates of the Start-up Compliance Costs of the GST in Australia

|

Forecaster

|

Scope/Time of Forecast

|

Methodology/Assumption

|

Gross Business Start-up Compliance Costs ($ bil)

|

Business Start-up ComplianceCosts ($ bil)

|

|

Federal Treasury

|

National/ Early 2000

|

Based on a NZ study by Sandford & Hasseldine

|

2.2

|

1.02

|

|

National Tax & Accountants Association

|

National/ Early 1999

|

1.5 million firms x $10,000 per firm

|

15

|

8.67

|

|

Victorian Employer’s Chamber of Commerce & Industry

|

National/ September quarter of 1999

|

Survey of 326 firms

|

5

|

2.7

|

|

Ernst & Young

|

Very large business sector/1999

|

Survey of over 320 largest corporations

|

0.75%-1% of business’ annual revenue

|

|

|

Ernst & Young

|

Small business/ January 2000

|

4 case studies, ranging from $9,740 to $19,930 per small firm

|

More than 10 for the small business sector

|

5.68

|

|

Arthur Anderson

|

National/ Early 2000

|

Y2K study

|

24

|

14.05

|

|

Gartner Group

|

National/ Early 2000

|

Survey of 18 medium and large enterprises

|

More than 2.6

|

More than 1.25

|

|

Binh Tran-Nam

|

National/ 2000

|

Based on the Survey of the Canadian Federation of Independent

Business

|

4.1

|

2.15

|

Source: B Tran-Nam. “The Implementation Costs of the GST in Australia: Concepts. Preliminary Estimates and Implications” (2000) 3 Journal of Australian Taxation 331, 337-340.

Note that the business start-up compliance costs are derived by subtracting tax deductibility benefits and direct cash subsidies from the gross business start-up compliance costs, ie:

Estimated business start-up compliance costs = Estimated gross business start-up compliance costs – Tax deductibility benefits to businesses – Direct cash subsidies = Estimated gross business start-up compliance costs x (1-Business weighted overall marginal tax rate) x Percentage of businesses that can receive tax deductibility benefits - Direct cash subsidies (4)

where business weighted overall marginal tax rate = 0.294 and percentage of businesses that can receive tax deductibility benefits = 0.847. Numerical values were taken from the ATAX study quoted earlier. [27] The direct cash subsidies were estimated to be $0.3 billion – though these were not received or used by many small and medium businesses.[28]

Professional organisations, consulting firms and business organisations, as might be expected, produced considerably higher compliance cost estimates than did the government. At the same time, some non-government estimates appeared excessive and were difficult to justify. Overestimations arose a result of

i) extrapolation biased toward larger businesses; and

ii) aggregation of GST-related and normal upgrading of computer and system costs.

Table 2: Comparative Studies Carried out After July 1 2000

|

Research Body

|

Scope/

Time of Study

|

Methodology

|

Average Time Spent in Start-up Compliance Costs (hrs)

|

Average Financial Compliance Costs ($)

|

Total Average Business Start-up Compliance Costs

|

|

Victoria University

|

Mid-June to mid November 2001

|

Case studies of 6 Victorian small businesses

|

170hrs

|

$6,012

|

$12,380

|

|

QCOSS

|

December 2000-July 2001

|

Mail survey of non-profit Queensland businesses

|

|

|

$5,610

|

|

Victorian Govt Reports

|

2000

|

Survey of small and medium business in urban and regional Victoria

|

100-300hrs

|

$6,000

|

|

|

Curtin University, WA

|

Sept/

October 2000

|

Large scale mail survey of 868 Australian small businesses

|

131hrs

|

$5,006

|

$7,626

|

Since 1 July 2000, some Australian studies have been carried out to estimate the actual GST start-up compliance costs borne by small businesses. The Small Business Research Unit at Victoria University of Technology (“VUT”) conducted six case studies of small business located in Victoria, covering the period from early June to mid November 2000.[29] It was found that actual GST implementation and compliance costs ranged from $3,331 to $30,140 per business (with an average costs of $12,380 per small business). The break up of the costs is just below 50% direct costs and just over 50% time costs.

There are several reasons why the above estimates are or appear to be excessive. First, what is referred to as “GST” encompasses non-GST aspects of tax reform, such as the Business Activity Statement (“BAS”). Secondly, cost estimates include both start-up costs and some recurrent costs for the July-November 2000 period. Thirdly, a substantial cost component is related to the purchase of computers and upgrading of software. Efforts were not made to isolate hardware and software costs attributable only to the GST. Finally, the study did not estimate tax deductibility benefits enjoyed by participating businesses.

An investigation to quantify the GST start-up costs of non-profit organisations was also conducted by the Queensland Council of Social Services (“QCOSS”).[30] Between December 2000 and July 2001, two surveys were sent to over 7,000 organisations and approximately about 11% of these organisations responded to each. The average cost of the implementation of the GST and other parts of the tax reform package was estimated to be approximately $5,610. Consistent with the literature, the QCOSS study found tax-reform implementation costs to be regressive.

Since questionnaire forms are not included the QCOSS “Final Report”, it is difficult to assess the reliability of the QCOSS study. Many of the criticisms levelled at Victoria University study may also be applicable; eg:

1. the QCOSS study did not disentangle the GST from other elements of the tax reform package. In addition, non-profit organisations also had problems with the Fringe Benefits Tax (“FBT”) and the various special statuses that operate in the sector;

2. some recurrent compliance costs may have been inadvertently included in estimated start-up costs; and

3. costs of acquiring new computing equipment should be allocated only in part to the GST.

Note that since the non-profit organisations are not taxable, they did not enjoy any tax deductibility benefits arising from the implementation of the tax reform package.

The Victorian Government Economic Development Committee has undertaken similar research by inquiring into the impact of the GST in Victoria.[31] The Committee engaged the services of two consultancy groups, RSM Bird Cameron and Econtech to assess the impact of the GST on the competitiveness of small and medium sized businesses. The research was geared particularly towards businesses in regional Victoria. Preliminary findings indicated that, on average, GST compliance costs for small businesses were approximately $6,000, which included the purchase of new computers, GST software and training. Similar to the QCOSS and VUT studies, the research focused solely on the GST, although acknowledgement was made of “flow-on” benefits for businesses in terms of compliance with other tax reforms, such as Pay-As-You-Go (“PAYG”).

More recently, a qualitative study has been undertaken by Associate Professor Jeff Pope and doctoral candidate Nthati Rametse of the Department of Economics, Curtin University.[32] Here a large scale mail questionnaire survey was sent to 4,000 small businesses in Western Australia (“WA”). Of these, 868 surveys were returned. Information provided by the questionnaires has provided the authors with an early indication of compliance costs incurred by WA small businesses. GST start-up costs have been estimated $5,006 plus an average of 131 hours per firm. Time spent valued in dollars has been estimated at $2,620, around 34% of total start-up costs. Gross GST start-up costs were thus estimated at $7,626.

Preliminary findings of the Pope/Rametse study are valuable because they provide information about start-up costs on a larger scale, which is beyond the scope of this project. Unlike the Pope/Rametse research, this project elicits information by way of in-depth analysis of a smaller number of participants. The focus of the project is quantitative, not qualitative.

The main task of the project is to obtain reliable and representative data relating to both transitional and recurrent business compliance costs. These data need to be obtained directly from business taxpayers and not by proxy. Methodologies for obtaining the required data can vary. They include:

• large-scale mail survey;

• log-book case study;

• face-to-face/telephone interview;

• time motion study; and

• archival/document analysis.

The two most popular methods in compliance costs research are large-scale surveys and in-depth case studies. Both methodologies have been employed to investigate compliance cost issues in the past, though both have shortcomings.[33]

The appropriate strategy for collecting data depends on the objective of the study and the resources available to the researchers. If the primary purpose of a study is concerned with broad policy evaluation, then it will be necessary to obtain reliable estimates of the aggregate transitional and recurrent compliance costs. This calls for large-scale surveys of a suitably stratified, representative sample. Sample selection of this kind of research in Australia requires active assistance from the ATO. In order to extrapolate from sample results to the entire economy, researchers also need macro statistics on the cross-distribution of taxpayers (or business taxpayers, in the case of the GST) and market wages for different occupations and interest rates.

If, on the other hand, the aim of the study is to gauge the impacts of tax reforms on businesses and to identify ways of reducing compliance costs, in-depth case studies are more useful. The case study approach has been used in this study for the following reasons:

• resources required for careful large-scale mail surveys are prohibitive;

• we do not have access to the ATO’s taxpayers file, which is very important for representative sample selection;

• concern with contemporary events is best explored by the case study method;[34]

it adds to the reliability of findings if the same taxpayers are surveyed over the life of the project; and

the use of case studies instead of large-scale surveys is capable of producing better quality responses to questions regarding the determinants of compliance costs.

Disentangling core accounting and tax compliance costs is easier with case study methodology than with mail surveys. Case studies use dialogue with business people in order to differentiate activities that would be performed if no tax system were applicable.

Our project includes a specific focus on rural small businesses. Farming case studies will be supplemented by a further information source. Such an approach was suggested by the National Farmers Federation (“NFF”), after it was highlighted that that many of the Ralph reforms are relevant only once or more in a farm’s life-cycle. For example, a farm business structured as a partnership might bring in new partners. This is the appropriate time to examine the new regime for the valuation of trading stock. Capital Gains Tax (“CGT”) reforms might become relevant after a drought, when a back paddock has to be sold – or in inter-generational transfer when a farmer dies. In addition to farming case-studies, therefore, “consensus data groups” have been formed – drawing initially on the NFF’s own data – in order to facilitate reform-specific inferences within the project’s time constraints.

The project team, including representatives of NFF and the Council of Small Business Organisations of Australia (“COSBOA”), an associate investigator and the two authors (as chief investigators), met in Canberra at the commencement of the project in 2001. The purpose of this was to devise a blueprint for the case-study method, including some discussion about sample selection and content of the questionnaire. Several specific issues raised by industrial partners were considered. A similar meeting was held later in Melbourne between two representatives of Taxpayers Australia (“TA”) and the two authors.

For budgetary and time reasons, subject to additional information regarding farms, the project initially intended to limit its inquiry to 20 participants. Ten participants were intended to be primary producers and ten were to comprise urban and regional small businesses, each drawn from the memberships of the three industry partners. As a result of the decision at the research methodology meeting, however, the project sample was considerably extended. A substantially larger number of participants were selected, to ensure that:

• the requisite number of businesses completed the investigation to the end of 2 years; and

• participants exhibited reasonable variations in terms of relevant criteria such as legal form, turnover, location and age of business, etc.

Finding suitable participants was difficult initially. Small businesses had become wary of tax reforms and were concerned by the additional paperwork which the project might involve. A publicity campaign, including a report in the Australian Financial Review, an NFF press release and a radio interview were conducted with the intention of increasing awareness of the project and obtaining participants. At the same time, some industry partners also offered some small inducements such as free subscriptions to participants who joined the project’s research or free seminar attendance. As a result of these actions, the NFF supplied the project with a final list of 26 primary producers and COSBOA and TA provided 13 and 14 small business participants each respectively. These participants exhibit an appropriate geographic and industry spread throughout rural New South Wales and Victoria, southern Queensland, Darwin in the Northern Territory, Hobart in Tasmania, the ACT and the Perth and Margaret River district of Western Australia.

Data is being gathered from participants by means of a series of questionnaires and log books, and follow-up interviews. The first questionnaire is concerned with the transitional compliance costs of the first wave of tax forms with particular emphasis on the GST. Log books will then be used to record incremental changes in business compliance costs as a result of these reforms.

An initial questionnaire entitled “Transitional Costs of Tax Compliance” was designed by the authors to collect both qualitative and quantitative information, including questions on psychological costs based on input by a qualified psychologist. The questionnaire in draft form was extensively discussed with industry partners, an associate investigator and a research associate. It was also subjected to pilot testing by several project participants. The final version was sent to participants by email and ordinary mail in the second half of 2001. Use of a questionnaire such as this required the formal approval of the Human Ethics Committee at the University of NSW.

The purpose of conducting face-to-face interviews is to confirm the quantitative data obtained from the questionnaires/log books and to gather additional qualitative comments. In this way, direct insights are obtained into the impact of tax reforms on business compliance costs and how to reduce them. Interviewing each participant in person has been a daunting task. Participant numbers, as mentioned, have now increased from a projected 20 to 53. The two authors and a research associate conducted interviews in Gippsland and the Geelong region, Victoria (November 2001), Darwin in the Northern Territory (December 2001), Perth and the Margaret River region of Western Australia (January 2002), southern NSW (February-March 2002), Hobart in Tasmania (March 2002), central Victoria (April 2002), north-western NSW and southern Queensland (June 2002). Further interviews in central NSW have been scheduled.

The project maintains an outreach link with participants, both before and after the interview process. A website for the project http://www.sbtaxreform.org has been established by the research assistant, as well as an occasional newsletter.

Thirty participants have sent back their completed questionnaires and twenty-two have so far been interviewed. The business profile of these respondents is summarised in Table 2.

Table 3: Respondents’ Business Profile

|

Attribute

|

Observation

|

|

Legal form of business

|

7 sole traders, 10 partnerships, 7 companies & 1 trust

|

|

Related business

|

No: 15; Yes: 10

|

|

Main business activity

|

Primary: 12; Manufacturing: 1 &

Service: 12

|

|

Turnover 1999-2000

|

Min: $0; Max: $3,000,000;

Mean: $473,682; Median: $200,000

|

|

Turnover 2000-01

|

Min: $0; Max: $3,000,000;

Mean: $464,851; Median: $227,000

|

|

Estimated taxable income 1999-2000

|

Min: -$1,086; Max: $500,000;

Mean: $51,471; Median: $20,000

|

|

Estimated taxable income 2000-01

|

Min: -$2,378; Max: $140,000;

Mean: $37,987; Median: $20,000

|

|

Number of owners, partners, directors & trustees 1999-2000

|

Min: 1; Max: 4; Mean: 1.6; Median: 2

|

|

Number of owners, partners, directors & trustees 2000-01

|

Min: 1; Max: 4; Mean: 1.6; Median: 2

|

|

Number of full-time employees 1999-2000

|

Min: 0; Max: 13; Mean: 0.84; Median: 0

|

|

Number of full-time employees 2000-01

|

Min: 0; Max: 8; Mean: 0.64; Median: 0

|

|

Number of part-time employees 1999-2000

|

Min: 0; Max: 6; Mean: 0.72; Median: 0

|

|

Number of part-time employees 2000-01

|

Min: 0; Max: 6; Mean: 0.76; Median: 0

|

|

Number of unpaid helpers 1999-2000

|

Min: 0; Max: 4; Mean: 0.44; Median: 0

|

|

Number of unpaid helpers 2000-01

|

Min: 0; Max: 4; Mean: 0.44; Median: 0

|

|

Number of owners, partners, directors, trustees working on tax affairs

1999-2000

|

Min: 0; Max: 4; Mean: 1.32; Median: 1

|

|

Number of owners, partners, directors, trustees working on tax affairs

2000-01

|

Min: 0; Max: 4; Mean: 1.32; Median: 1

|

|

Number of full-time employees working on tax affairs 1999-2000

|

Min: 0; Max: 2; Mean: 0.12; Median: 0

|

|

Number of full-time employees working on tax affairs 2000-01

|

Min: 0; Max: 2; Mean: 0.12; Median: 0

|

|

Number of part-time employees working on tax affairs 1999-2000

|

Min: 0; Max: 1; Mean: 0.16; Median: 0

|

|

Number of part-time employees working on tax affairs 2000-01

|

Min: 0; Max: 1; Mean: 0.16; Median: 0

|

|

Number of unpaid employees working on tax affairs 1999-2000

|

Min: 0; Max: 1; Mean: 0.16; Median: 0

|

|

Number of unpaid helpers working on tax affairs 2000-01

|

Min: 0; Max: 1; Mean: 0.16; Median: 0

|

Source: Authors’ own survey.

Inferences that can be drawn from these statistics are as follow:

• business turnover and taxable income declined from 1999-2000 to 2000-01;

• decline in business turnover and taxable income was accompanied by a marked reduction in the average number of full-time employees;

• unpaid helpers played a reasonably important role in small business; and

• the amount and level of owners/employees contribution to tax affairs remained static.

Table 4 summarises respondents’ accounting and taxation structures.

Table 4: Respondents’ Accounting and Taxation Structure

|

Attribute

|

Observation

|

|

GST Registration

|

Yes: 25; No: 0

|

|

Submission of BAS & IAS*

|

BAS only: 19; Both BAS and IAS: 6

|

|

Reporting frequency (BAS)

|

Monthly: 4; Quarterly: 21

|

|

Reporting frequency (IAS)

|

Quarterly: 5; Annually: 1

|

|

Accounting system 1999-2000

|

Cash: 22; Accruals: 3

|

|

Accounting system 2000-01

|

Cash: 22; Accruals: 3

|

|

Use of business financial statements**

|

|

|

Management information & decision making

|

Most important: 13

Second most important: 11

|

|

Tax’s requirement

|

Most important: 15

Second most important: 7

Third most important: 3

|

|

Use by banks, lenders, etc

|

Most important: 2

Second most important: 4

Third most important: 16

|

|

Use of computer for business purpose 1999-2000

|

Yes: 23; No: 2

|

|

Use of computer for business purpose 2000-01

|

Yes: 23; No: 2

|

Source: Authors’ own survey.

Notes:

* IAS stands for Instalment Activity Statement.

** Several respondents ranked the various options equally.

The estimated transitional costs of tax reforms are summarised in Table 5. Note that the costs are related to the GST as well as other aspects of the first wave of tax reforms such as BAS/IAS and PAYG. Keeping in mind that these estimates include a variety of tax reform measures, the mean gross transitional costs of $5,442 per small business appear to be consistent with those generated by the Victorian Employers’ Chamber of Commerce & Industry and Tran-Nam as quoted in Table 5. (Note that the gross transitional costs do not include free advice provided by governmental and professional bodies to business taxpayers). After taking tax deductibility benefits and direct subsidy into account, the mean transitional business compliance costs were estimated to be $3,815 per business (with the median value of $2,272). Expressing as a percentage of the average annual turnover in 1999-2000 and 2000-01, the median gross and net business transitional costs accounted for about 1.34% and 0.86%, respectively.

Table 5: Estimated Transitional Costs of Tax Reform

|

Attribute

|

Observation

|

|

|

External adviser costs

|

Min: $0; Max: $5,250; Mean: $566; Median: $60

|

|

|

Direct costs of training

|

Min: $0; Max: $5,000; Mean: $767; Median: $60

|

|

|

Time loss in preparation for tax reform:

-Owner/partner/director/trustee

-Manager/accountant/programmer

-Clerk/Other employee

-Unpaid helper

|

Min: 0 hr; Max: 180 hrs; Mean: 44.46 hrs; Median: 30 hrs

Min: 0 hr; Max: 100 hrs; Mean: 5.60 hrs; Median: 0 hr

Min: 0 hr ; Max: 800 hrs; Mean: 35.32 hrs; Median: 0 hr

Min: 0 hr; Max: 10 hrs; Mean: 0.40 hrs; Median: 0 hr

|

|

|

Value of time loss*

|

Min: $0; Max: $16,165; Mean: $2,348; Median: $1,321

|

|

|

Computer hardware costs

|

Min: $0; Max: $3,600; Mean: $703; Median: $0

|

|

|

Special equipment costs

|

Min: $0; Max: $700; Mean: $67.2 ; Median: $0

|

|

|

Tax software costs

|

Min: $0; Max: $10,000; Mean: $771; Median: $165

|

|

|

Other transitional costs

|

Min: $0; Max: $4,000; Mean: $220; Median: $0

|

|

|

|

||

|

Gross transitional costs

|

Min: $0; Max: $20,954; Mean: $5,442; Median: $4,158

|

|

|

Gross transitional costs as a % of the average turnover in 1999-2000 and

2000-01

|

Min: 0; Max: 7.20; Mean: 2.15; Median: 1.34

|

|

|

|

||

|

Tax deductibility benefits**

|

Min: $0; Max: $4,812 ; Mean: $1,459; Median: $802

|

|

|

Direct subsidy from government

|

Min: $0; Max: $200; Mean: $168; Median: $200

|

|

|

Business transitional costs

|

Min: $0; Max: $11,653; Mean: $3,815; Median: $2,272

|

|

|

Business transitional costs as a % of the average turnover in 1999-2000 and

2000-01

|

Min: 0; Max: 7.03; Mean: 1.61; Median: 0.86

|

|

Source: Authors’ own survey.

Notes:

* The wage rates for owners, managers, clerks, other employees and unpaid helpers of small businesses are set at $33, $30, $20, $20 and $15, respectively. These wage rates are based on the 1997 ATAX study, allowing for inflation.

** The marginal tax rate varies depending on legal form and taxable income of businesses.

The first questionnaire also collected information about the psychological costs of tax reform. These costs will be presented and analysed in the project’s next report. Notably, a number of respondents indicated that compliance costs were stressful because of the amount of time required to acquire knowledge and understand the new business tax requirements. Financial costs, though obviously correlated, appear to have been a secondary consideration in the minds of many participants.

The Review’s definition of a small business seems under-inclusive. That became apparent early on. Turnover of less than $1 million identifies too small a class. It proved to be difficult at the planning stage to get a cross-section of small business participants who fell on the right side of this criterion. Small farming businesses, in particular, were affected. A rural participant in the Margaret River district of WA informed project members of the importance of wheat farming in WA. Almost the whole of WA’s annual wheat product, she said, generated export earnings for Australia. It was to be compared with wheat farming in NSW – which chiefly supplied local consumption. Minimum fixed costs plus the costs of cropping in rural WA meant that the $1 million figure was almost always exceeded – even though the enterprises in question employed only two or three persons. Other rural and non-rural businesses with a turnover of $3 million or higher regarded themselves as small and were accepted as such by most participants. In light of these revelations, it may be advisable for the government and the ATO to revise the small business definition.[35]

Widespread ignorance about the STS exists amongst both urban/regional and rural participants. Most had not heard of the STS and, those participants who were aware that the regime existed, were

unsure of its relevance to their business. Even participants generally familiar with taxation matters and active in small business associations were unaware that the STS made available the advantages of cash accounting and simplified accounting for depreciation and trading stock. None of the participants recalled receiving any relevant information. As one respondent commented: “There’s no information of the STS, it’s all on the GST and BAS”.

A variety of different accounting software packages were utilised by the participants. MYOB and Quick Books were most common. Some respondents found using such tailor-made software a useful practice and others found the experience traumatic. Participants who readily adapted to the use of software packages had usually been computer literate prior to the advent of the tax reform. Aberrations in Quick Books and MYOB which caused problems with the initial BAS were widely noted.

General views on the benefits of tax reform were sought from the participants. Notably, the farming small businesses, as a group, found tax reform to be of the greatest value. Opinions tendered to vary amongst non-farming small businesses. Views are gathered under the following headings.

Additional tax reporting was cited by some participants as a source of fiscal discipline or new information for the conduct of their businesses. One grazier and wheat cropper commented:

I was a shocker for doing book-work. It would get around to the end of the financial year – I’d wait until July – before I’d submit the tax returns and then I’d say “Oh, so that’s how I’ve done for the year”. Now I’m already doing tax planning for this year.

Another sheep farmer observed:

I’m brought up-to-date a lot earlier. Normally, I’d only do the books once a year and at the end of the year. I’d tend to forget things I’d done eight to nine months ago. Farmers tend to be a bit slack, especially farms my size and smaller. Bigger farms can’t afford to be. So the smaller farms have been brought into line.

Most participants who experienced benefits refused to assign a financial value to the managerial benefits that they have experienced as a result of tax reform. Whether or not such benefits are inherently unquantifiable or whether it is simply too early for businesses to equate these benefits with monetary gain is at this stage unknown.

Fewer COSBOA and TA than NFF participants cited “managerial benefits” as one of the advantages of tax reform. Many non-farming participants felt they already knew well enough how their businesses were “travelling”. Additional information required to meet tax obligations was superfluous for managerial purposes. As one small business, an upholsterer from Darwin, put it:

Filling out BAS forms doesn’t provide me with a better understanding of where my business is at. I already knew where my business was; I could tell you where we were to the tune of the nearest $100. All I would need to do was look at the computer.

Greater managerial benefits seem to be experienced by businesses that were not computerised when the tax reforms were introduced. The “shoe-box brigade”, businesses forced to make the transition from manual to electronic record-keeping, may have experienced the largest managerial benefits from tax reform.

A new cycle of quarterly reporting was preferred by most small business participants. It often replaced annual tabulation of business data and preparation of taxation returns. Additional information enabled many participants to monitor how their businesses were “travelling” before the end of the financial year. Adoption of quarterly (or in some cases, monthly) reporting as opposed to annual reporting led some participants to implement more effective record keeping and administrative practices. Better-informed business decisions were taken. For some businesses, improved and more regular accounting practices led to greater efficiency. One non-farming small business owner commented that the GST was a “handy tool” in reminding clients to pay their bills on time. A NSW sheep farmer who sold rams through private saleyards likewise observed that the new system encouraged insistence on prompt payment: “the sooner you’re paid, the sooner you are able to claim back your tax credit”. Most respondents agreed that by forcing businesses to “keep the books up-to-date”, the new system was promoting a more professional small business culture.

Some proprietors of service-oriented, non-farm small businesses (accountants and financial planners) commented that they had seen substantial incidental benefits for some of their clients. Quarterly reporting systems meant that business decisions formerly based on 18 month-old data were now revisited four times a year. The finding appears to be consistent with those obtained by previous quarterly surveys of small businesses.[36]

Small businesses required to collect GST for the government account for it on a monthly or quarterly basis, in arrears. Two entrepreneurial small businesses commented to the investigators that this provided them with an “interest free loan”, in effect, which could be invested and repaid at the end of an accounting period. Both of these respondents were farmers. They had maximised this cash-flow benefit by selling at the beginning of each quarter and purchasing stock towards the end. Comparable and more obvious cash-flow advantages accrue to retail or service-oriented businesses.

Tax reform has resulted in a (widely reported) upsurge of work for service-oriented, non-rural small businesses involved with tax compliance. One Geelong-based tax agent commented:

My client-base has increased almost three-fold since the GST. When it was brought in, a lot of unscrupulous firms used it as an excuse to increase their prices. I got a lot of new clients, who were disgruntled with the way they had been treated by their old accountant.

“Bruce”, an accountant from Ballarat believes that the tax reform has revitalised what was threatening to be a flagging industry:

When I graduated from university in 1993, I was told that accountancy was a “dying trade” and that I should prepare myself for an alternate career. Now I’m barely able to keep up with all my clients.

A corollary of this resurgence, as noted again has been that fewer accountants are able to engage in pro bono work for charity and not-for-profit organisations.

Business proprietors were also asked to identify their three main problems with taxation reform. Often a far greater number of problems was raised. Time compliance costs were usually the primary concern. Other issues were of secondary significance.

Time that had to be taken in updating systems, training staff, re-pricing merchandise and attending seminars was felt by many participants to be unreasonable. Difficulties were compounded by the large amount of ATO material that required reading and attention. Participants recounted experiences of congested offices and overflowing filing cabinets.

A common theme of retail proprietors was that they were being removed from the “coalface” of their businesses. As one shop-owner commented:

I’m seldom at the counter any more because I have so much to do at the computer. It’s gradually wheedled me away from being the face of the shop to the point where customers are saying “Have you been away on holidays?” or “I thought you’d sold, I don’t see you here any more”.

Farmers, too, resented the added administrative tasks that took them away from other concerns. As one interviewee stated:

I am a farmer. I like working with my brain, and outdoors with animals. I do not like excessive paperwork and filling in “stuff” for very little reward.

There was a strong feeling that the ATO was ill prepared for the new system. A most common complaint was informational. The ATO was perceived as being unable to provide a definitive answer to a straightforward question. Some participants were able to turn the situation to their advantage by adopting the most appropriate ATO recommendation. A shop proprietor explained:

You ring four times; you get four different answers; you take the one that suits you best.

Stories of accountants with databases full of contradictory ATO advice were common; this information was then available to the accountant as a “get-out-of-jail-free card”, lest he or she provide incorrect advice. It remains to be seen whether this strategy will be adopted industry-wide.

Difficulties with the ATO added to time costs of compliance. One Victorian accountant reported writing off $20,000 in the last financial year, reflecting the “direct result of time wasted on the phone with the tax office”. A dairy farmer employed by a neighbouring farm to administer their business affairs also recounted the following experience:

One of my clients got a letter back from the ATO telling him that he owed $4,000 for PAYG which had been accumulating interest. When I took at look at his books. I saw that he had actually paid it. What had happened? Because it was a business partnership, instalments from 2-3 amounts were added up and sent as one cheque to the ATO. The ATO didn’t have the capacity to split them up — it didn’t see that there was a $6,000 GST credit. So you had one cheque stapled to 5 different pieces of paper — 3 PAYG, one BAS etc. It had obviously gone to the ATO and the other pieces of paper had been distributed to other departments without the cheque! It had been paid but this hadn’t filtered through to the right department. The ATO’s excuse was that the computer systems weren’t compatible between departments ... what it boiled down to was this: small businesses having to be ready by 1 July 2000, but I can tell you now, the ATO sure wasn’t!

The quality of written information supplied by the ATO elicited mixed views. Some participants believed that ATO publications were too technical or vague. Others found them useful. Most participants commented that the quantity of information was excessive - leading them to “drown in paperwork”. Use of complex terminology in ATO literature was criticised. Over-complex and unfamiliar language – such as use of the term “supply” instead of “expenditure” in the BAS form – elicited direct criticism from a number of participants. Much information distributed by the ATO appears to have been discarded or has remained unread.

Altogether, there was a strong feeling that the ATO was inflexible and/or inconsistent in its recommendations and could not cope with the new system. Only a handful of the participants appear to have made use of the ATO field officer - though, from those who did, the response was largely positive.

Better access to information was a commonly expressed need, particularly in the rural sector. Surprisingly few participants enlisted the support of the ATO Field Officers, who were available for on-site consultation and advice. Internet services in regional centres were adequate but often severely lacking in more remote areas. Uninterrupted access to the ATO website (a useful reference) was beyond the means of many participants. Seminars provided by regional branches of the NFF assisted many farmers, though other businesses, particularly small retail operations, were severely disadvantaged by their isolation from community resources.

Whilst the $200 voucher was received by most businesses, it was generally viewed as inadequate – if not derisive. Actual expenses incurred by small businesses appeared to far exceed all compensatory measures introduced by the government. A common strategy amongst business operators was to save money by obtaining unpaid work from a family member. Husbands or wives who supplemented the family income by outside earnings were often required to forego extra work to concentrate on administering small business affairs. A NSW farmer’s wife, who was forced for this reason to give up full-time work as a pre-school teacher, estimated that the cost to her family’s income was $16,000. Many participants regarded a family member’s break from outside work as a temporary measure, which suggests that the cost is perceived to be of a transitional nature.

A number of interviewees commented that the BAS deadlines were too restrictive. Problems for farmers tended to arise when BAS lodgement dates conflicted with a busy time like shearing. BAS deadlines also coincided with some school holidays, causing one participant to “organise family holidays around the BAS”. The form itself was also regarded as unnecessarily complicated for small business. One tax agent observed:

The BAS [form] has been designed for the convenience of the bureaucracy rather than the taxpayer, when it should have been the other way around.

Changes to the BAS format have done little to alleviate concerns; respondents tended to dismiss these as “unnecessary” or “cosmetic”. There was consensus that more flexibility was needed for BAS deadlines “particularly when they conflict with something like shearing”.

Several participants noted a substantial increase in accounting fees. $200 vouchers were often “snapped up” by unscrupulous accountants as miscellaneous administrative fees. This phenomenon was particularly marked amongst the clients of larger accounting firms in regional or urban centres. Exorbitant fees prompted many participants to employ the services of a local accountant whose rates were more reasonable. A small number of participants, however, withdrew altogether from the market for financial advice: “for fear of what I will be charged”.

Introduction of the GST, as noted, obliged most participants to acquire new software, or to upgrade existing packages. The majority reported this transition to be relatively straightforward. Occasional software malfunctions caused alarm to some proprietors. For example, after several months, a WA newsagent discovered that his new MYOB software was failing to correctly compute the GST component on weekly newspaper deliveries. The business had not claimed its entitlement to $3,000 worth of input credits. He was, however, able to rectify the problem in the next BAS.

Exemption of some items from the GST created considerable hardship for many retail proprietors. Merchandise had to be re-priced on the introduction of the GST and separate accounts of GST-free stock has to be maintained. As a shop-owner from WA ruefully commented: “It’s created losses to small business which will never, ever be quantifiable”. Rural small businesses, in general, were affected less by GST exemptions – though some reported difficulties in keeping proper account of commissions, yard fees and GST-free levies. Complications were also experienced in catering for shearers and other seasonal workers where some items were exempted as basic food items and some were not.

Most participants experienced stress as a result of tax reform. Not surprisingly, stress levels were lower amongst participants in the accounting and finance industry, or those with business qualifications. Stress was highest amongst participants engaged in retail businesses. Some retail proprietors went so far as to describe the pressure as “unbearable”. Threatened “price-gouging” prosecutions, attributed to Alan Fels and the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (“ACCC”), added to retail business concerns. “I thought his threats were totally unnecessary”, commented one business proprietor:

Small businesses really did the right thing – they went out and invested in the new software when they were already very busy running businesses. Actually, I think it would have been nice if someone like the Prime Minister had come out and thanked small businesses for their effort, instead of focusing on punitive measures if things went wrong.

Stress levels have decreased markedly since June 2000 and will be the subject of further study on recurrent, rather than transitional costs. Primary producers have a particular problem in predicting PAYG instalments in industries characterised by seasonal variation. Accurate estimations of quarterly income within 5% or 10% proved difficult for many small farmers. They were unable to predict a “boom” or “bust” year. PAYG Withholding also created problems for farms with a high staff turnover: ie graziers who may employ 40-50 shearers for a short period each year. Other farmers were resentful of the fact that they were required to provide the Government with an “interest free GST loan”.

Several farming-specific problems were raised. For one, farmers experienced difficulties in claiming back GST credits on capital equipment purchased under hire-purchase agreements. Many farmers only belatedly realised that a separate claim had to be submitted each time a hire-purchase instalment was paid over the financing period. Outright purchase of items subject to a chattel-mortgage, on the other hand, enables businesses to claim back the full measure of input tax credits at the time that an agreement is entered. The difference could involve farmers waiting two or three years before receiving input credits to which they were entitled. Another problem is that the PAYG system for farm income is unsatisfactory for an industry where income varies hugely as between years. This is so, particularly, if two PAYG income periods are in deficit and two are in surplus. One farmer suggested the option of taking an average at the same time the previous year rather than an average for the year overall.

Non-farming small businesses based on the expenditure of the public’s discretionary resources believe that the GST has brought about a downturn in expenditure on “non-essential” items, such as books and restaurant meals. The downturn is noted to be more marked in lower socio-economic areas, where the effect of this levy on the amount of disposal income is said to be more significant. Disastrous consequences have been described to the investigators.

Many of the problems experienced as a result of tax reform were perceived to be the result of an insufficient “lead-in time”. The theme was constantly expressed. “The problem as I see it”, said one NSW small business proprietor:

is that too many reforms were pushed through in too short a time frame. Australian businesses needed more time to adjust to changes than a three-year timetable would allow. The problem was that John Howard wanted to be known as the Prime Minister who brought about tax reform and he wanted to accomplish everything before his term was up.

Most participants were unaware that the STS existed. Others, when questioned, confused the STS with other tax reform initiatives. Participants said that they had received little or no information on the subject. There was a growing feeling, well-expressed by one NFF participant, of a generalised “fatigue” with tax reform and its implications:

We received so much information about the GST, the BAS, the ABN. Now with the STS, I think the feeling is “I’ll just leave it for the accountant to deal with”.

A couple of small farmers, who already accounted on a cash-basis for GST purposes, claimed to be investigating the STS option. Indications were that the final decision remained in the hands of their accountant. A number of accountants and tax advisers, included in the study as participants, indicated that they would not be recommending the STS to the majority of their small business clients.

A few tentative views can be expressed. Options of cash accounting, simplified depreciation and trading stock offer few advantages to many small businesses. The STS is unsuitable for businesses with high creditors and low debtors. The STS offers little to businesses with low levels of depreciable plant and equipment, or which already account on a cash basis. A low STS threshold unaccountably excludes many otherwise eligible enterprises with high turnover levels.[37] Conclusions such as these are inconsistent with the Review’s claim that the STS is a significant compensation for small businesses adversely affected by tax reform.

Whilst most business proprietors cited few personal benefits, there was, at the same time, a general acknowledgment that the new tax system was “good for Australia”. Unreported cash transactions and tax avoidance were minimised. Almost all of the participants interviewed supported tax reform in principle. Some service-oriented businesses (accountants and financial planners) commented that they[ ] had seen substantial incidental benefits for some clients. This finding appears to be consistent with those obtained in previous quarterly surveys of small businesses. Most participants supported the abolition of the old sales tax regime. “Dan”, a furniture upholsterer from Darwin, experienced considerable difficulties under the old sales tax regime: “Several times I was caught out claiming exemptions that I mistakenly believed I was entitled to and had to make repayments at his end of the financial year”. He added:

And the reasoning behind the tax was just absurd. Under the old system, a sofa repaired by me was exempt from tax, but the cushions used in those repairs were taxed at 12%. Once I was even asked to charge tax on the thread I used to sew the cushions! I mean, how can I explain that cost to a customer?

Some participants observed that the current round of tax reform was directed towards satisfying the interests of “big business”. Small business concerns and input into tax reform were believed to be insufficiently recognised. Several participants remarked that it was appropriate for small businesses to receive payment for their role as “tax collection agents” in relation to aspects of the new system. Most participants thought that the transformation to the GST would have been easier had the Australian Democrats not secured the exemption of some food and other items from the levy. GST exemptions created significant extra work for the retail sector. Retailers said that the time costs of tax reform alienated them from their roles as shopkeepers. Two respondents noted that government money would have been better spent on education programs than publicity and promotion. There was a general feeling of dissatisfaction with a perceived arbitrariness in ACCC interventions.

The observation has been noted, in relation to voluntary and charity work, that accountants and other small business people now have less time for such activity. An unquantifiable impact on local communities may be the result. This was combined with a more general recognition that church groups and charitable organisations had suffered as a result of tax reform.

Respondents were asked how they thought tax compliance costs might be reduced. This question elicited a number of responses. One was that small businesses might somehow be “compensated” for their roles as tax collectors for the government. Businesses could be permitted to retain a fixed percentage of their GST revenue (eg 10%). One Tasmanian business was actively involved in lobbying the government for such an initiative. However, the general consensus by most participants was that the implementation of such a proposal would be unrealistic.

It was also suggested that BAS deadlines might be moved 6 weeks after the month’s end to provide more time for the processing of information. More flexibility may be needed. A majority of businesses found the current deadlines (normally 21 days after the end of the reporting period) too restrictive.

One business proprietor proposed a reduction and simplification of the number of tax reports. Further change to the BAS format was widely deprecated. The same report, it was said, could be submitted to an accountant and the ATO, thereby eliminating the need for generating additional statements. Standardising the book-keeping practices of accountants was also cited as an assistance in eliminating much of the confusion of the first 12 months.

There was a general consensus amongst the taxpayer respondents that consultation and pilot-testing with small business industry bodies was essential before any further changes were implemented. Many also felt that the small business community would be better served by more effective education programs, instead of the “slick” GST publicity campaign which was televised in early 2000.

Based on a sample of 25 case studies, the study estimates that small businesses incurred, on average, gross transitional costs of $5,442 in preparation for the first wave of tax reforms, which include GST, ABN, PAYG and BAS. After taking tax deductibility benefits and direct subsidy into account, the average transitional business compliance costs were estimated to be $3,815 per business. This is slightly less than the costs estimated by comparable studies, many of which have not yet taken associated tax reform benefits into account. Psychological costs associated with tax reforms were found to be considerable.

Two matters stood out in relation to the STS. First, the STS small business threshold of $1 million is inadequate. Secondly, small businesses are largely ignorant of the STS and attempts by the ATO to publicise and educate the small business sector about this regime have been ineffectual.

Tax reforms are acknowledged to involve recurrent benefits for some small businesses. Managerial and cash flow advantages have been observed. On the whole, it might be said, the proprietors of small businesses support the tax reforms. This attitude is independent of the way in which proprietors regard significant tax-related transitional costs that small businesses have incurred and somewhat negative perceptions of the ATO.

This appendix suggests a new model for evaluating business taxpayer compliance costs in connection with replacement of the WST with a revenue-equivalent GST. The WST, in this context, includes both the repealed federal WST and the state taxes repealed at that time. Standard practices in the literature compare the annual business taxpayer compliance costs of the old tax system (ie, WST) with those of the new tax system (ie GST). It is an approach submitted to be conceptually unsatisfactory. Economic cost-benefit analysis should also be applied.

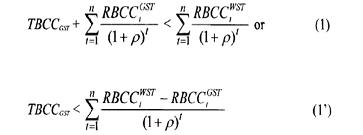

Let the subjective time rate of social preference be denoted by ρ (> -1), which, for practical purposes, can be approximated by the market rate of interest. Let TBCCGST stand for the transitional business compliance costs of the GST and let RBCCi, be the recurrent business compliance costs of tax i (= WST, GST) in period t. Suppose that the GST will operate for n periods. Then the GST is said to simplify the tax system (i.e., to be simpler than the WST) if

The above inequality has a straightforward interpretation. The GST may be simpler (more complex) than the WST from the business perspective if the transitional business compliance costs of the GST is smaller (greater) than the present value of the discounted sum of existing and future incremental benefits in recurrent business compliance costs. Note that the magnitude of TBCCGST may take several periods to be fully realised (including periods before and after its introduction).

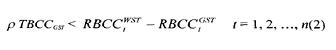

While inequality (1’) is conceptually sound, it has little value in practice. This is because it is difficult enough to estimate the recurrent business compliance costs of the GST for the current period, let alone all future periods. This calls for a more operational condition, which requires less information than (1’). To this end, we use the present-value arithmetic to convert TBCCGST into an indefinite stream of equivalent annual costs. This involves treating transitional costs as a perpetual stream of annual costs, which is equivalent to assuming that the GST is indefinitely (or sufficiently) long-lived. Under this approach, the GST is said to be simpler than the WST if

Under a further assumption that ![]() remains more or less constant for t = 1,2, ..., n, inequality

(2) further reduces into

remains more or less constant for t = 1,2, ..., n, inequality

(2) further reduces into

![]()

where ![]() can be, in principle, estimated from a single cross section of data. Under

the current practices in the literature, the GST is said

to simplify the tax

system

can be, in principle, estimated from a single cross section of data. Under

the current practices in the literature, the GST is said

to simplify the tax

system ![]() Using (2’), this article proposes that the GST simplifies the tax

system only if the incremental saving in business compliance

costs exceeds the

annual equivalent of the transitional business compliance costs of the GST.

Using (2’), this article proposes that the GST simplifies the tax

system only if the incremental saving in business compliance

costs exceeds the

annual equivalent of the transitional business compliance costs of the GST.

Note that condition (2’) can be equivalently expressed as follows. The

GST is said to simplify the tax system if![]()

where![]()

can be thought of as the internal rate of return of the investment in the GST.

Two final remarks are made. First, the above discussion uses the replacement of the WST by the GST as an illustration. The proposed framework is equally applicable to similar tax reforms in any country. Secondly, in terms of empirical applications, an estimate for the business compliance costs of the WST in Australia is available from the 1997 ATAX study.[38]

[*] This research is supported by an ARC SPIRT grant. We wish to thank Sarah Wilkin for her valuable research assistance and Bob Douglas for his insightful comments. We are also grateful to our industry partners. National Farmers Federation, Taxpayers Australia and the Council of Small Business Organisations of Australia.

[**] Australian Taxation Studies Program, Faculty of Law, University of New South Wales.

[***] Faculty of Law, Monash University.

[1] See D Shaviro, “Beyond Public Choice and Public Interest: a Study of the Legislative Process as Illustrated by Tax Legislation in the 1980s” (1990) 139 University of Pennsylvania Law Review 1. 24-8; S Pollack, “A New Dynamics of Tax Policy?” (1995) 12 American Journal of Tax Policy 61, 69; AC Warren Jr, “Three Versions of Tax Reform” (1997) 39 William and Mary Law Review 157, 160-1; and E McCaffery, “Federal Tax Policy in the New Millennium: the Missing Links in Tax Reform” (1999) 2 Chapman Law Review 233. 235-41. The same trend became evident in the United Kingdom in the late 1970s: see C Brown and C Cedric, “Tax Reform and Incentives: a Case Study of the United Kingdom” in C Sandford (ed), Key Issues in Tax Reform (1993) 201-2.

[2] Shaviro, above n 1, 28, examining the governments of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher.

[3] S Pollack, “Tax Reform: the 1980s in Perspective” (1991) 46 Tax Law Review 489, 489.

[4] Shaviro, above n 1. 36-51.

[5] JG Head (ed), Australian Tax Reform in Retrospect and Prospect (1989); and R Krever, “Tax Reform in Australia: Base-Broadening Down Under” (1986) 34 Canadian Tax Journal 346, 346-394.

[6] Review of Business Taxation, A Tax System Redesigned: More Certain, Equitable and Durable (1999) 743-752 (“A Tax System Redesigned”).

[7] Ibid 744.

[8] A Tax System Redesigned, above n 6, 15-16.

[9] G Dodge, J Fleming and D Geier, Federal Income Tax: Doctrine, Structure and Policy (2nd ed, 1999) 21-25.

[10] Australian Treasury, Tax Reform: Not a New Tax, a New Tax System: the Howard Government’s Plan for a New Tax System (1998) 131-152 (“ANTS”); and A Tax System Redesigned, above n 6, 31-33.

[11] A Tax System Redesigned, above n 6, 22, 745.

[12] See, for example, B Tran-Nam, “Use and Misuse of Tax Compliance Costs in Evaluating the GST” (2001) 34 Australian Economic Review 279. 283-284.

[13] See. for example, C Evans, K Ritchie, B Tran-Nam and M Walpole, A Report into Taxpayer Costs of Compliance (1997) 79-81.

[14] House of Representatives Standing Committee on Industry, Science and Technology Report. Small Business in Australia: Challenges, Problems and Opportunities (1990).

[15] Australian Bureau of Statistics, Small Business in Australia (1997), 1 (“ABS”); and Evans et al, above n 13, 77.

[16] ABS, 1999 Year Book (1999) derives the ratio 1,004,200/1,046,900 = 95.9%; cf ratio of 894,500/929,500 = 96.23%.

[17] ABS, above n 15, 8; cf Australian Treasury, “Small Business and Primary Producers to Benefit from the New Business Tax System”, Press Release (No 59, 27 September 1999), 1:99% of primary producers are small.

[18] A Tax System Redesigned, above n 6, Recommendation 17.1, 575; see also discussion in Evans et al, above n 13, 77.

[19] ABS, Small Business in Australia - Update 1999-2000 (2001) para 1.1.

[20]B Tran-Nam, “Tax Reform and Tax Simplification: Some Conceptual Issues and a Preliminary Assessment” [1999] SydLawRw 20; (1999) 21 Sydney Law Review 500, 505-508.

[21] Tax progression refers to the progressiveness of the income tax schedule alone whereas tax progressivity measures the overall progressiveness that results from the interaction of the income tax schedule and a particular distribution of income.

[22] By “tax culture” it is meant the extent to which taxpayers engage in tax avoidance and tax evasion and the tax administrators’ efforts to combat these schemes.

[23] A Tax System Redesigned, above n 6, 31-33.

[24] KS Johnston, Corporations’ Federal Income Tax Compliance Costs: A Study of Small, Medium-size, and Large Corporations (1963) 67-70.

[25] This kind of distinction is relevant to the legal or formal incidence of tax compliance costs. Economists are typically more concerned with the economic or effective incidence of the compliance costs, ie, which individuals actually bear the burden of the tax compliance costs.

[26] CT Sandford, M Godwin and P Hardwick. Administrative and Compliance Costs of Taxation (1989) 16-18

[27] See Evans et al, above n 13, 40-42.

[28] For a more detailed discussion refer to B Tran-Nam, ‘The Implementation Costs of the GST in Australia: Concepts, Preliminary Estimates and Implications” (2000) 3 Journal of Australian Taxation 331, 340.

[29] Small Business Research Unit, Victoria University, Goods and Services Tax (GST) Implementation and Victoria Small Business, Final Report (2001) available at: http://www.sbv.vic.gov.au.

[30] Queensland Council of Social

Services, Taxing Goodwill, Final Report of the GST Impact Research Project

(2001) available at:

http://www.qcoss.org.au.

[31] Parliament of Victoria, Economic Development Committee. Inquiry into the Impact of the Goods and Services Tax on Small and Medium Sized Businesses in Victoria, Report Number One (2000) available at:http://www.parliament.vic.gov.au/edevc/inquiries/GST/Report%20One%20Table%20of%20Contents.htm.

[32] J Pope and N Rametse, “Small Business Start-Up Compliance Costs of the Goods and Services Tax: Estimates and Lessons from Tax Reform” (Paper presented at the Fifth International Conference on Tax Administration, Sydney, 2002).

[33] Technical advantages and disadvantages of both methods are summarised in C Evans, K Ritchie, B Tran-Nam and M Walpole, A Report into Incremental Costs of Tax Compliance (1997) 24-26.

[34] See R K Y in, Case Study Research: Design and Methods (1984).

[35] On this subject see also Draft Taxation Ruling, Income Tax: Simplified Tax System Eligibility – STS Average Turnover, TR 2002/D3 available at: http://law.ato.gov.au/atolaw/view.htm?docid=DTR/TR2002D3/NAT/ATO/00001.

[36] The May 2000 and August 2000 editions of the Yellow Pages, Small Business Index, found that over 50% and 62% of small businesses surveyed, respectively, were in favour of the GST.