Journal of Australian Taxation

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Journal of Australian Taxation |

|

COMPARING NEW ZEALAND’S PRIVATE RULINGS SYSTEM AND ITS FEATURES WITH A SELECTION OF INTERNATIONAL PRIVATE RULINGS SYSTEMS – WHAT IS THERE IN COMMON?

Adrian Sawyer[*]

This study provides a brief comparative analysis of private rulings systems in twenty seven nations, with the private rulings systems in Australia, Canada, Sweden, United Kingdom and United States the main focus of comparison with the New Zealand regime. The study concludes that there is surprisingly little in common between the regimes reviewed, apart from instances of one country/jurisdiction modelling its regime on that of another and adopting some of its features, or from coincidence.

Binding private rulings have become an increasingly important component of many tax systems and have played a key role in fostering confidence and trust in the relationship between taxpayer and tax authority. However, binding private rulings are a supplement to, and not a substitute for, clearly drafted legislation. Tax legislation should have a clear purpose, reflecting precisely the circumstances to which it applies. However, tax legislation that most countries promulgate is far from clear or precise, hence the need for some form of rulings facility, be it administrative or legislative. While in the circumstances of unclear and imprecise legislation a binding private rulings procedure is often seen as crucial to an effective tax system, even if all legislation were clear and concise, a binding rulings system may still be desirable to increase taxpayer certainty.

As is the case for virtually all taxation law issues, the design of a binding private rulings system inevitably involves a balance of costs and benefits. On the one hand, a comprehensive rulings system provides security for taxpayers and facilitates individual business decisions based on economic considerations without the risk of unforeseen tax consequences. However, on the other hand, in the context of a mass decision making system, the diversion of resources to the operation of a comprehensive ruling system has the potential to bring enforcement mechanisms to a grinding halt, especially if a complex and lengthy appeal mechanism is in place.

Nevertheless, while the increased use of binding private rulings has the potential ultimately to reduce administrative costs, particularly in the areas of auditing and investigation, a complete trade-off will not follow. Hence, the decision in most jurisdictions is to allow binding private rulings in some areas so long as the rulings are not precedential. Limiting the scope of the rulings system reduces the need for multiple levels of administrative review and the costs associated with them. Furthermore, since binding private rulings are frequently not officially published (although this situation appears to be changing after reviewing the following analysis) and not cited by courts, the potential damage is limited (or confined) if an erroneous interpretation is made in a binding private ruling.

From an international perspective, the question may be asked “Why do countries operate different types of binding or administrative rulings systems?” and related to this “What are the potential implications for taxpayers and businesses with international operations/income as a result of this situation?”

To answer the first question this may often be a side effect of historical practice, or just a result of the freedom of choice or national sovereignty that each nation has to run its tax system. However, such differences have implications for individuals and businesses that do business domestically and more importantly, internationally, where the forces of globalisation are encouraging (or perhaps pressuring) convergence in many areas of business law, trade and in various aspects of taxation law. Major differences in binding rulings regimes may create uncertainty when undertaking business activity. Regardless of whether diversity or a high degree of uniformity is desirable, a comparative analysis of key features in rulings regimes stands to benefit revenue authorities, advisors and taxpayers in all countries with such regimes, to gauge the extent to which their particular regime could be improved or enhanced.

It should be noted that the focus of this study, like the author’s An International Comparison of Binding Rulings Regimes: A Report for the Adjudication and Rulings Group of the Inland Revenue Department (“the International Report”),[1] is on private (or advance/letter) rulings and not public rulings or any other form of binding ruling (such as New Zealand’s and Australia’s product rulings and New Zealand’s status ruling). Hence this places a limitation on the scope of analysis, although it can be stated that the vast majority of the twenty seven countries/jurisdictions have a public rulings system that accompanies the private rulings system. Detailed analysis is provided for the six major countries regimes reviewed as part of the International Report, namely Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Sweden, United Kingdom and United States and not on the other twenty one jurisdictions.

Reliance on binding private rulings varies significantly among the countries surveyed in the International Report, ranging from limited use in some (a number of jurisdictions were excluded as their use of the binding ruling facility was far too limited to provide useful or interesting comparison) through to perhaps, at the other extreme or end of the spectrum, legislation that virtually requires taxpayers to seek rulings if they wish to avoid penalties and the like. Given the multitude of factors that explain why some rulings systems are limited and others comprehensive, it is clear that an assessment of the quality and applicability of the incumbent regimes in New Zealand and Australia will benefit from comparing the approaches of other countries or jurisdictions.

The International Report reviewed the private binding ruling regimes in the following countries/jurisdictions, divided into three groups:

Group One

Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Sweden, United Kingdom and United States — the six major regimes, forming the first tier for analysis.

Group Two

Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Hong Kong, India, (Republic of South) Korea, Mexico, the Netherlands and South Africa. These ten countries formed the second tier for analysis.

Group Three

Germany, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Pakistan, the Philippines, Portugal, Spain and Switzerland. Interesting features of the regimes in these eleven countries formed the third tier for analysis.

The choice of selection of countries and their groupings followed a preliminary analysis of the regimes reported on in the International Bureau of Fiscal Documentation’s (“IBFD”) loose leaf service on rulings[2] and from the work completed in the International Report. The rulings systems in Group One countries are comprehensive, well-established and reflect a broad spectrum of approaches to private rulings. In contrast the jurisdictions covered by Group Two were assessed by the International Report as having interesting features for comparison with the Group One countries, but frequently the systems were less comprehensive in scope and detail. Group Three jurisdictions were included either because they had some novel features or reflected relatively new binding rulings regimes. While not explicitly stated in the International Report, the New Zealand regime formed the status quo upon which to compare the regimes from the twenty six other countries. Prior to presenting the comparative analysis, a summary of the New Zealand regime is provided.

The Commissioner of Taxation (“Commissioner”) is able to issue four types of binding rulings in New Zealansd: public rulings, private rulings, product rulings and, from 20 May 1999, status rulings on the application of a change in the law on an existing private ruling or product ruling. In the process of making a private ruling, the Commissioner has the discretion to make conditions and assumptions. Within the legislation there are a number of exclusions that prevent the Commissioner from issuing a ruling, although these do not include the general anti-avoidance provision. For resource reasons, private rulings were initially limited to specific arrangements entered into after the issue of the ruling by the Commissioner. From 1 April 1996 the regime was extended to enable the Commissioner to provide private rulings on current and completed arrangements. Resource constraints have continued to cause backlogs with the delivery of rulings.[3] The Rulings Group of the Inland Revenue Department’s (“IRD”) head office issues rulings centrally.

A private ruling is the Commissioner’s interpretation of how a taxation law applies to a specific arrangement for specifically identified taxpayer(s). Taxpayers or their agents, who apply for a private ruling, are required to comply with strict application and disclosure requirements and a failure to comply will lead to non-application of the ruling. The arrangement that is to be the subject of the ruling must be seriously contemplated. However, as a matter of practice, some additional information and/or tax laws may be allowed to be added after the initial application is filed. The level of depth of analysis by the Commissioner with respect to a ruling application may be very extensive, depending upon the nature of the subject matter and tax laws upon which the ruling is sought. There is a statutory right for the applicant to consult with the Commissioner prior to the issue of a private ruling if the content of the proposed ruling differs from that requested by the applicant. A draft ruling is normally required to be provided with the ruling application. A “team” of three staff members normally deals with an application for a ruling. The first member is a rulings analyst, who has primary responsibility for the ruling and will have the highest level of involvement in the process. The second member is a manager who is responsible for a team of analysts - this person will be involved to the extent of providing direction and guidance to the analysts that report to them. The third member, who will normally have only general oversight or involvement with a particular issue, is a senior manager. This senior manager will be responsible for signing off the ruling prior to its issue.

The Commissioner will be bound to assess taxpayers in accordance with the position taken in an applicable private ruling if the taxpayer relies upon the ruling. However, while taxpayers are not bound by a ruling, until 20 May 1999 applicants were required to disclose in their returns that they had applied for a private ruling and whether or not they followed it. They were also obliged, until 20 May 1999, to disclose any material difference between the arrangement described in the private ruling and the actual arrangement. Applicants cannot appeal or challenge an unfavourable ruling, only the consequential assessment in the normal manner. All private rulings will apply to the arrangements entered into for the period for which the ruling is issued; they cannot be extended.

The Commissioner is able to withdraw a private ruling or a ruling may cease to have effect following a change in a taxation law. Withdrawals may not be retrospective in effect and the withdrawal cannot apply before notification of the withdrawal has been provided to the applicant. A withdrawal cannot be effective before the expiry of the period for which the ruling applies if the arrangement has been entered into before the withdrawal. However, tax law changes may cause retrospective cancellation of the application of a ruling.

Private rulings are not published, but where the content of a private ruling raises an issue of wider significance to taxpayers generally, the Commissioner may decide to issue a public ruling reflecting the approach taken in that private ruling. A status ruling on a private ruling will not be published.

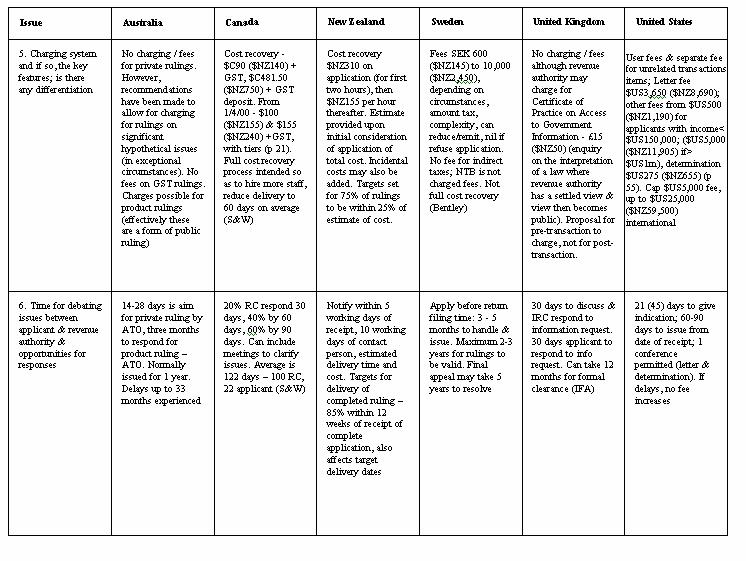

Private rulings are charged for on a full cost-recovery basis, which for the purposes of the regime until 25 August 1999, implied a non-refundable application fee of $NZ210 (including GST), an hourly rate thereafter of $NZ105 (including GST) and reimbursement of certain fees and disbursements. From 26 August 1999, the fees increased to a non-refundable application fee of $NZ310 (including GST), an hourly rate thereafter of $NZ155 (including GST), and reimbursement of certain fees and disbursements. It is interesting to note that based upon figures in the IRD’s Annual Reports to 30 June,[4] an estimate of the average cost of a private ruling as charged by the Rulings Group in 1999 was approximately $NZ4,000, increasing to $NZ6,000 in 2000 and rising still further to $NZ7,000 in 2001.

The Commissioner must provide an estimate of the fees payable in excess of the application fee and must advise the taxpayer of the likely date for issue of the ruling if this is expected to be longer than four weeks after receipt of a complete application. The Commissioner may waive all or part of the fees payable by the applicant. There is provision for the Commissioner to contract out work, such as through using external consultants.

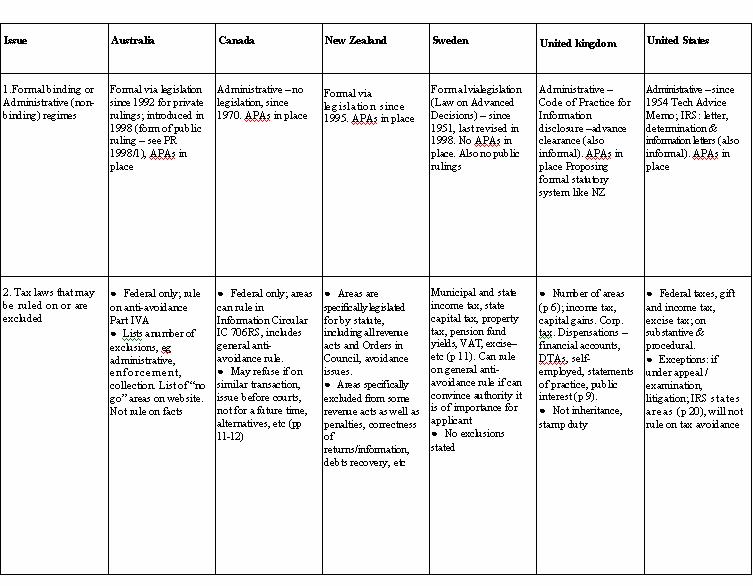

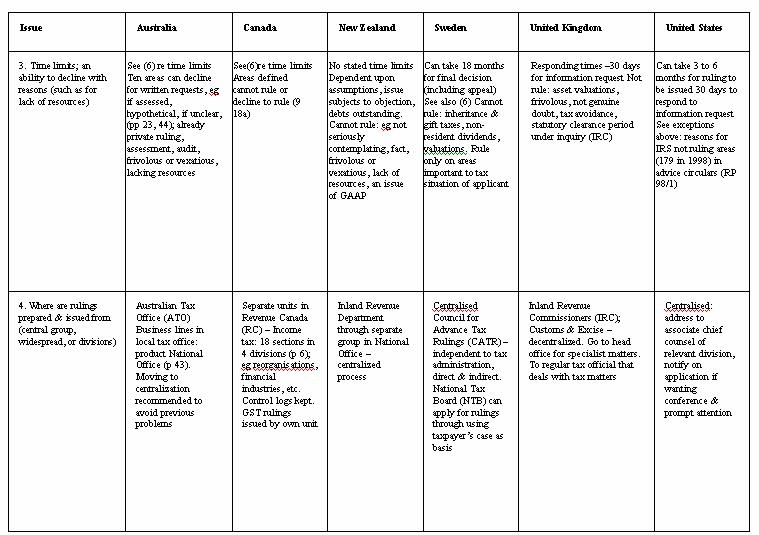

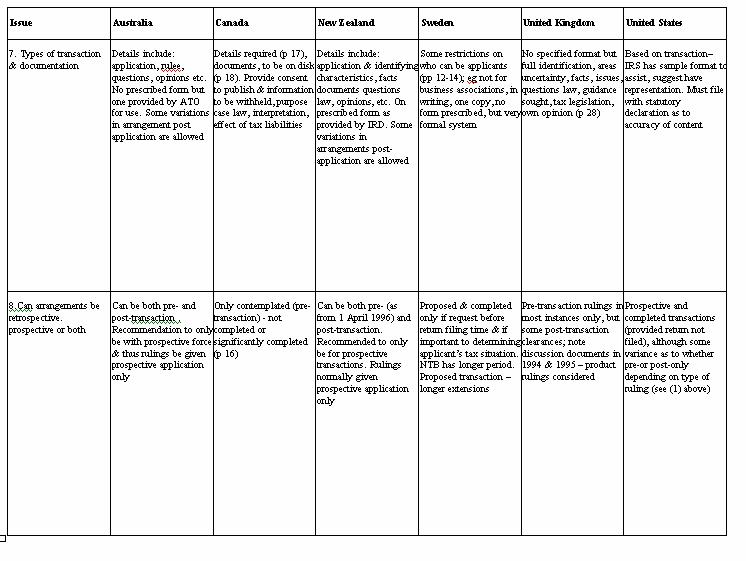

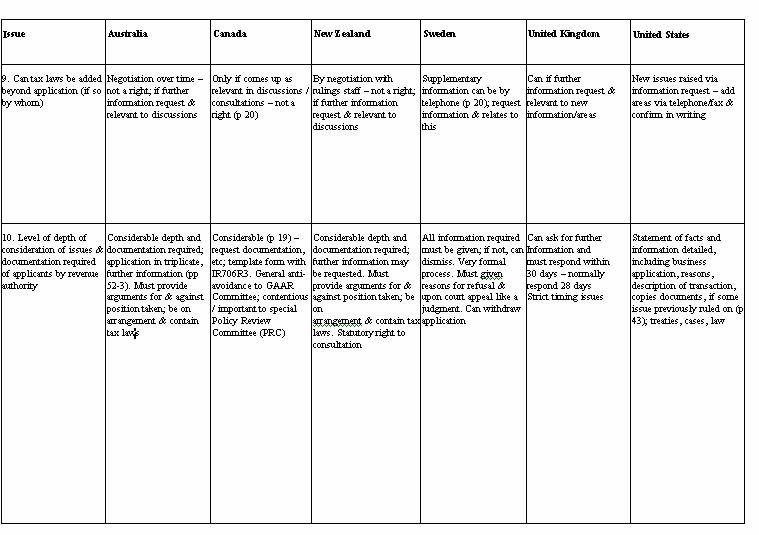

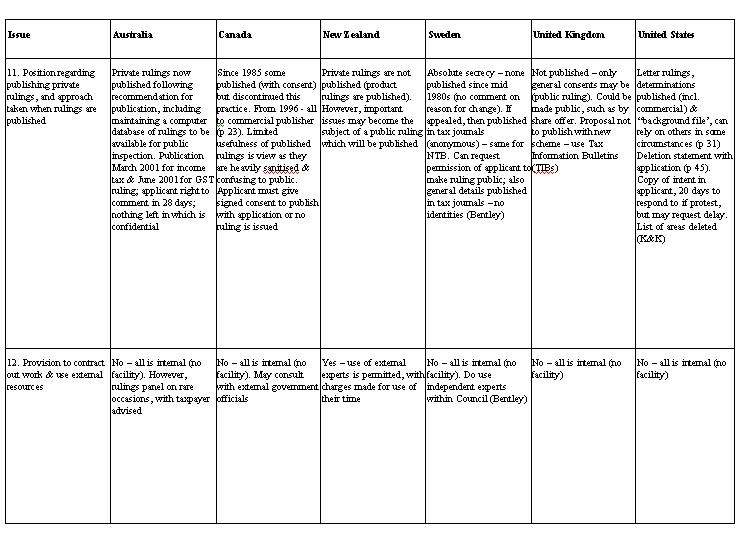

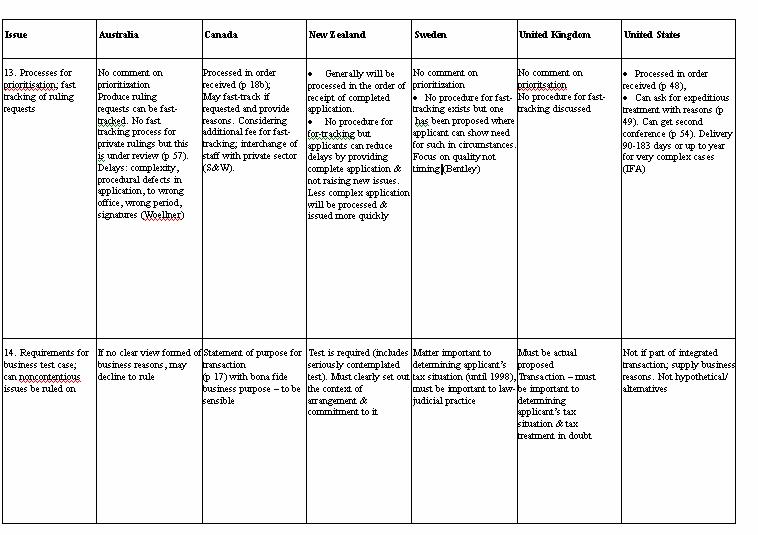

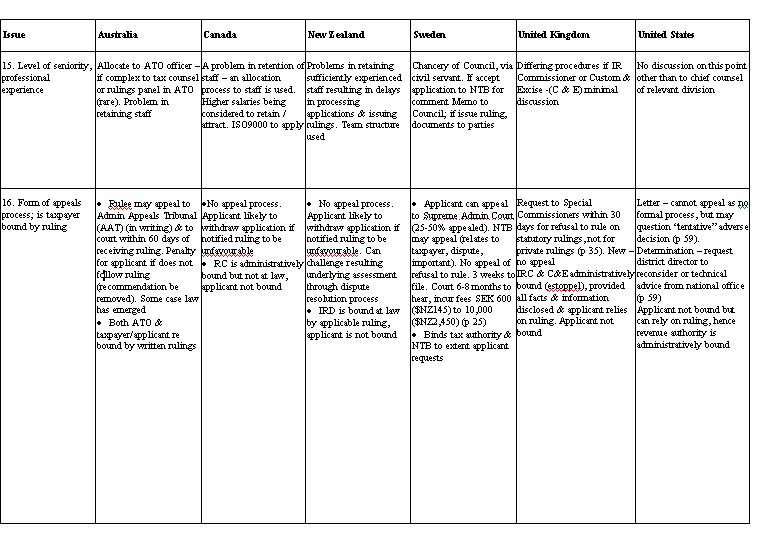

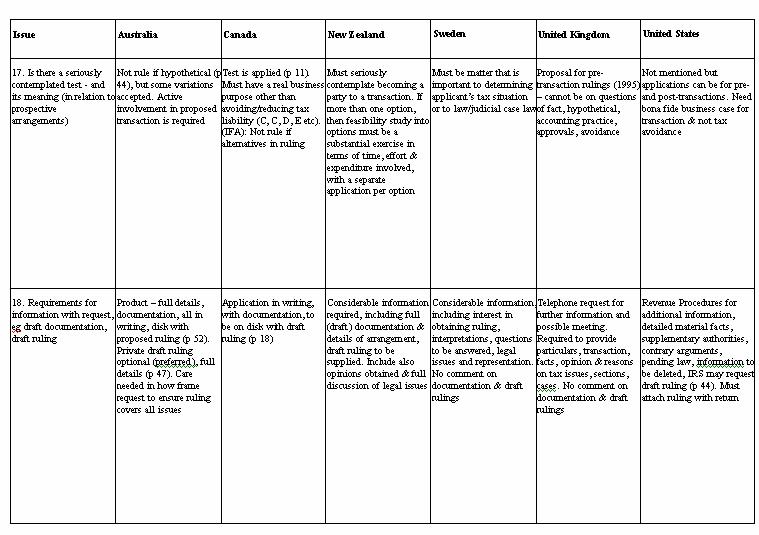

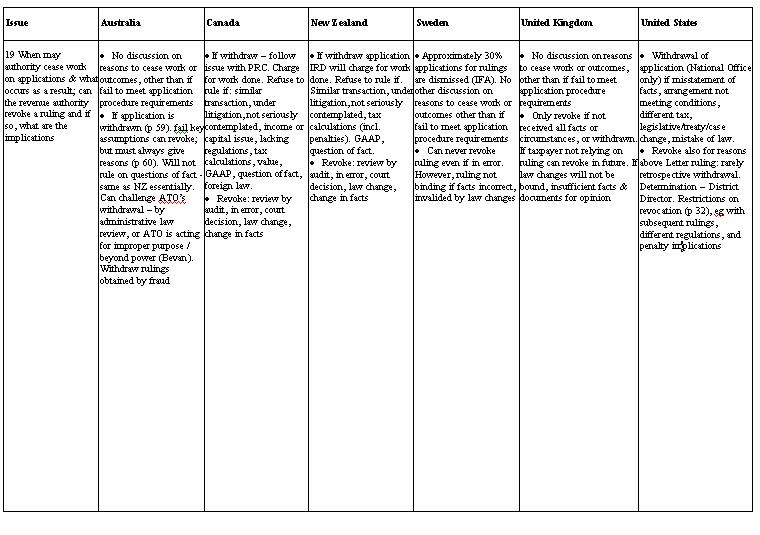

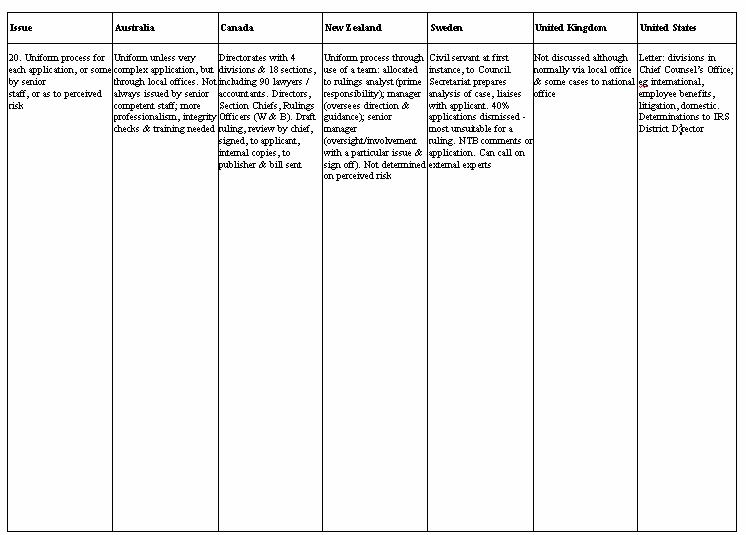

Table 1 contains a detailed summary of the major features of the regimes in the first tier of countries, namely Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Sweden, United Kingdom and United States. Information from the second and third groups of jurisdictions is not presented in table format as the data is incomplete on some aspects of the analysis. Rather important aspects of these two groups of jurisdictions are included in the discussion that follows Table 1.

Table 1: Comparison with Group One Countries (Based on International Report, 2001)

Key to Table 1

|

APA:

|

Advance Pricing Agreement

|

|

p ...):

|

IBFD’s Loose-leaf service references for each country under

review[5]

|

|

IFA:

|

International Fiscal Association: Advance

Rulings[6]

|

|

IRC:

|

Inland Revenue Commissioners (UK),on aspects of the UK

system[7]

|

|

Bentley:

|

Study by Duncan Bentley on the Swedish and Australian

regimes[8]

|

|

Bevan:

|

Study by Christopher Bevan on the Australian

system[9]

|

|

C, C, D, E:

|

Comparative study by Chang et

al[10]

|

|

IBFD (1995):

|

Comparative study by IBFD on mostly EU countries conducted in

1995[11]

|

|

K & K:

|

Study by Ray Knight and Lee Knight on the US

system[12]

|

|

Prebble:

|

Comparative study by John Prebble on binding rulings in

1986[13]

|

|

S & W:

|

Study by Roy Shultis and David Williamson on the Canadian

system[14]

|

|

W & B:

|

Study by David Williamson and Tim Bryant on the system in

Canada[15]

|

|

Woellner:

|

Study by Robin Woellner on the system in

Australia[16]

|

A majority of the regimes that were reviewed in the International Report had a formal binding ruling regime in place as compared to a non-binding (or administrative) regime. However, those in Group One and Group Two were both split 50:50, with a clear majority of 2:1 having a formal system in Group Three jurisdictions. Most countries stipulated a variety of tax laws that were excluded from being ruled upon, with great variation in the breadth of areas that can be ruled upon. Where information was available, time limits were placed on dealing with applications for rulings for both the revenue authority and the applicant. Almost all revenue authorities had the ability to decline requests (including declining for insufficient resources to handle the request).

In some instances, limits exist about how long outstanding issues may be debated between the revenue authority and applicant, with some facility or opportunities provided for responses from applicants. Related to this matter is the question of how definitive the arrangement (or transaction) must be that is to be ruled upon, along with the issues that may be ruled upon (transaction) and the types of documentation that are to be supplied (and whether changes in the arrangement post application are allowed). Considerable variation exists on all of the above between the regimes reviewed in the International Report. Variation also exists as to whether tax laws can be added (and if so, by whom – the revenue authority and/or the applicant) after the application is filed. In some instances, revenue authorities are permitted to cease work on applications, especially where the applicant has failed to provide all the required information or not responded to queries.

A variety of approaches exist for the preparation and issue of rulings, as between a small central group, widespread decentralisation, or by operational divisions. In almost all instances it is the revenue authority that is responsible for making and issuing rulings; a notable exception is Sweden with its separate rulings authority.

A minority of regimes utilised some form of charging system for rulings. Most that employed such a regime had fixed or variable rates depending on the complexity of the application, but not to the extent of full cost recovery in the traditional accounting sense of the concept. It appears that most regimes do not provide for contracting out of work (such as to private sector professional firms) and do not draw upon external resources.

The level of depth of consideration of issues and documentation required of applicants by the revenue authority is extensive in almost all of the regimes reviewed, especially in Group One countries. Many regimes will only permit prospective arrangements to be ruled upon, with a minority allowing for both prospective and retrospective (post-transaction) arrangements to be ruled upon. It appears that few regimes adopt any form or have any processes in place for determining prioritisation or fast tracking of ruling requests - requests are usually processed in the order of receipt and passed to a particular rulings staff member (although in a few instances the degree of complexity, which frequently affects the time for delivery of the ruling, may be a determining factor in the allocation process).

Many of the regimes have requirements for a “business case” test (that is, clearly setting out the context of the arrangement and their commitment to it) to accompany the application, requiring in part that the applicant seriously contemplate the transaction. To this end a test of “seriously contemplated” may be employed, but it is difficult to establish just what that test entails.[17] In New Zealand this means that the applicant must be at least seriously contemplating becoming a party to an actual or proposed arrangement.[18] If more than one option is being considered, then the feasibility study into the options must be a substantial exercise in terms of time, effort and expenditure involved, with a separate application for each option to be considered.[19] Some contentious issues are not able to be ruled upon, which is reflected often through the exclusion of certain statutory provisions (such as the general anti-avoidance provision, if one exists in the tax laws of a particular nation). It should be noted that some regimes explicitly allow for rulings to cover general and/or specific anti-avoidance provisions.

Many regimes require documentation and other information to accompany ruling applications, such as draft documentation describing the arrangement. In most instances a draft ruling is required or at least encouraged to be provided with the application. Provision of a draft ruling can speed up the process and assist with focussing the revenue authority on its consideration and the applicant in their preparation in relation to the core legislative provisions that are to be ruled upon.

A majority of the jurisdictions surveyed permit or require the publication of private rulings in certain instances (see Australia, Canada and the United States in Group One; Belgium, Denmark, Hong Kong, Hungary, Iceland, India, Korea, Mexico and the Netherlands in Group; Two; and Italy, the Philippines and Spain in Group Three) and where publication occurs, they will be in a sanitised form, removing the identifying characteristics of the applicant(s). A frequent reason for refusing to publish such rulings is the issue of privacy, as against reducing opportunities for certain applicants advisors to have “inside knowledge” of the revenue authority’s interpretation of certain provisions in relation to certain types of arrangements.

An overwhelming majority of countries do not have a formal appeal process in place for objecting to unfavourable rulings outside of the normal objection process for tax assessments. If such an appeal process exists, the appeal is normally through a specialist court or body that hears ruling disputes (Australia is one exception to this where the normal court process is employed). In most instances taxpayers are not bound by an issued ruling, but there is the risk of penalties being imposed if they do not follow a ruling.

Several instances of countries modelling their regimes on others were identified. Specifically New Zealand used the Australian model as a base but made significant policy decisions to alter key aspects, such as not to include an appeal mechanism for unfavourable rulings and creating a product ruling regime to complement the private rulings regime.[20] The New Zealand regime, the most recent of the six regimes in Group One, was also developed in the context of the rulings systems in Canada and the United States. Denmark’s model was specifically designed on the model operating in Sweden.

However, in most instances jurisdictions have not specifically adopted an existing model in its entirety but rather it appears have selected aspects from a variety of models, with their decisions frequently aligned with the nature of the legal system operating within the jurisdiction (such as common law or civil law). The overwhelming conclusion is that national sovereignty which applies in the choice of tax laws is also reflected in the choice/model of private rulings systems utilised in the twenty seven nations.

From the analysis undertaken by the International Report it could be argued that if there were no costs incurred as part of the trade-off with a comprehensive rulings model, then an expanded ruling system drawing upon the favourable aspects of the Australian and New Zealand systems (the former providing a comprehensive, free, ruling system with a full range of appeal options in the case of an adverse ruling, the latter a comprehensive, efficient user pays system without any access to an appeal facility for unfavourable rulings), might be a model for consideration for any country seeking to implement a new regime or overhaul its existing regime. Key considerations in any trade-off include the risks to the revenue, the level of resourcing required and the need to maintain consistency in dealing with all applications for rulings. However, models in other countries also offer interesting features that could be considered in the New Zealand and Australian contexts.

Indeed, a full binding private ruling system could go even further, providing for publication of sanitised private rulings to create a public check on revenue authorities’ decision making and to ensure greater dissemination of administrative practice (even where a binding private binding ruling has no precedential value). Nevertheless, practical constraints, such as limited financial resources, high personnel turnover and the like, on providing interpretations by way of binding rulings, may preclude moving to a model with these and other desirable features in anything more than a gradual process.

What must be considered seriously with any binding rulings regime are the costs and benefits of an expanded ruling system beyond, for instance, that which is already in place in New Zealand’s system. The focus will no doubt include areas where costs can be reduced and benefits enhanced. Already, the practical constraints in other jurisdictions have impinged on the theoretical model, as the delays in the appeals process illustrate. Whether these concerns can be resolved and a more effectual balance can be struck between tax authorities’ resource commitments and ultimate resource savings remains to be seen, and should be afforded critical attention in any decision to alter the current regime model in any country. Thus the level of resources that Governments provide to their rulings bodies has a significant impact upon the practical application of the extent of the regime and perhaps more fundamentally whether it can carry out its purpose(s) and core features.

To respond to the question posed in the title of this article − what is there in common in the binding rulings regimes featured in this study − the response would be surprisingly little across the board except where a particular country has modelled its regime on an existing regime. One such example is New Zealand, which modelled aspects of its legislative scheme largely upon Australia’s, but the delivery and design are profoundly different, such as in relation to centralisation versus decentralisation of delivery, the number of rulings actually issued and charging to name but a few. However, the similarity is much closer with the system that operates in Denmark, which is modelled closely on the rulings system operating in Sweden.

[*] Senior Lecturer in Taxation and Business Law, Department of Accountancy, Finance and Information Systems, University of Canterbury. An earlier version of this article was presented at the Fifth International Conference on Tax Administration, Sydney, Australia 2002. The data relating to the rulings regimes is stated as at November 2001.

[1] AJ Sawyer. An International Comparison of Binding Rulings Regimes: A Report for the Adjudication and Rulings Group of the Inland Revenue Department (2001).

[2] International Guide to Advance Rulings (IBFD loose-leaf service).

[3] See especially comments made in relation to Adjudication and Rulings in the IRD’s annual reports: Inland Revenue Department Annual Report for the year to 30 June 1996 (Wellington 1996) 39-42; Inland Revenue Department Annual Report for the year to 30 June 1997 (Wellington 1997) 31-35; Inland Revenue Department Annual Report for the year to 30 June 1998 (Wellington 1998) 37-40; Inland Revenue Department Annual Report for the year to 30 June 1999 (Wellington 1999) 45-49; Inland Revenue Department Annual Report for the year to 30 June 2000 (Wellington 2000) 69-75; and Inland Revenue Department Annual Report for the year to 30 June 2001 (Wellington 2001) 70-74.

[4] Inland Revenue Department Annual Report for the year to 30 June 1999 (Wellington 1999) 45-49; Inland Revenue Department Annual Report for the year to 30 June 2000 (Wellington 2000) 69-75; and Inland Revenue Department Annual Report for the year to 30 June 2001 (Wellington 2001) 70-74.

[5] International Guide to Advance Rulings (IBFD loose-leaf service).

[6] International Fiscal Association, Eilat Congress: Advance Rulings (Vol 84b, 1999).

[7] See Inland Revenue (UK), Advance Income Tax Rulings 70-6R4 (2001), available at: http://www.inlandrevenue.gov.uk/index.htm (visited October 2001): and Inland Revenue (UK), IR Code of Practice 10 - Information and Advice (1999), available at: http://www.inlandrevenue.gov.uk/index.htm (visited October 2001).

[8] D Bentley, “Advance Rulings: Lessons from the Swedish Model” (1997) 51(5) Bulletin for International Fiscal Documentation 210.

[9] C Bevan. “ATO Rulings: When can the Commissioner Withdraw a Private Ruling?” (2000) 34(11) Taxation in Australia 577.

[10] J Chang, R Cullen, R Dorenberg, A Easson, R Krever, D Sandler and R Sommerhalder, “Private Income Tax Rulings: A Comparative Study” (1995) 10(9) Tax Notes International 738.

[11] International Bureau for Fiscal Documentation, “Ruling Practice: A European Survey and Comparison” (1995) 35(2) European Taxation 58.

[12] RA Knight and LG Knight, “Private Letter Rulings: When/How/If (1994) 177(3) Journal of Accountancy 62.

[13] J Prebble, Advance Rulings on Tax Liability (1986).

[14] R Shultis and D Williamson. “The Rulings Process: Practical Problems and Possible Solutions” (Conference Report, Canadian Tax Foundation, 1999) 20:1.

[15] D Williamson and T Bryant. “The Income Tax Rulings Process: Dispelling the Mystery” (1998) 46 Canadian Tax Journal 274.

[16] R Woellner, “Private Tax Rulings: Some Practical Problems” (50th Anniversary Conference, Australasian Law Teacher’s Association, 1995).

[17] Ibid Table 1, Issue 17.

[18] Tax Information Bulletin, “Questions We’ve Been Asked” (1995) Vol 7:6, 28.

[19] Ibid 32.

[20] Australia later introduced its own form of product ruling.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/JlATax/2002/14.html