Journal of Australian Taxation

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Journal of Australian Taxation |

|

LIQUIDATIONS –

INCOME TAX ISSUES

By Stephen Barkoczy,[*] Jane Trethewey[**] and Michelle Bennet[***]

This article examines some of the important income tax issues that arise in relation to the liquidation of a company. The article commences with an outline of the general law position relating to liquidations and then proceeds to consider a range of specific issues including some complex dividend, franking and Capital Gains Tax issues.

The liquidation of a company raises several complex tax issues. In particular, there is a range of specific collection, dividend, franking and Capital Gains Tax (“CGT”) issues that need to be carefully considered in the winding-up process. These issues arise under an array of highly technical provisions contained in the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (Cth) (“ITAA36”), the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (Cth) (“ITAA97”) and the Tax Administration Act 1953 (Cth) (“TAA”). The aim of this article is to identify and closely examine some of these issues from the point of view of both a company’s liquidator and its shareholders. The remainder of this article is divided into the following parts:

• Part 2 briefly outlines the general law position in relation to liquidations;

• Part 3 examines some of the key duties and obligations imposed on a liquidator under the taxation laws;

• Part 4 considers the circumstances in which distributions made by a liquidator may constitute dividends;

• Part 5 examines various CGT issues that arise in relation to liquidations;

• Part 6 focuses on in specie distributions made by liquidators; and

• Part 7 contains our concluding comments.

The liquidation of a company has been described as:

a formal process under which the affairs of a company are wound up, its assets collected and sold, its debts paid and the surplus (if any) distributed amongst its members.[1]

There are two forms of liquidation recognised under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth):

• a “voluntary winding up”; and

• a “compulsory winding up”.

Both the above forms of liquidation involve the appointment of a liquidator and end with the deregistration of the company. In prescribed circumstances, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (“ASIC”) may also deregister a company outside the formal liquidation process (ie without the appointment of a liquidator).[2]

A voluntary winding up is initiated by special resolution of the company.[3] Once this resolution has been passed, the company must cease to carry on its business[4] but the corporate state and powers of the company continue until it is deregistered. Where the company is solvent, the winding up is referred to as a “members’ voluntary winding up” and the members appoint the liquidator. However, where the company is insolvent, the winding up is referred to as a “creditors’ voluntary winding up” and the creditors appoint the liquidator.[5]

In contrast to a voluntary winding up, a compulsory winding up occurs through the courts. In practice, the main circumstance in which a compulsory winding up arises is where a company is insolvent and proceedings are initiated by a creditor.[6] In a compulsory winding up, the court appoints the liquidator.

Generally, a compulsory winding up commences at the time that a court order to wind up the company is made[7] whereas a voluntary winding up commences at the time the resolution to wind up the company is passed.[8] From this time onwards:

• any disposition of the company’s property is void (unless it is made by the liquidator);[9]

• the shareholders shares cannot be transferred or have their rights varied (unless the court otherwise orders);[10]

• the powers of the company’s officers (other than the liquidator) are suspended;[11] and

• creditors are unable to enforce judgments against the company or bring proceedings against it (without leave of the court).[12]

According to the common law, the principal duties of a liquidator of a company are:

to take possession of and protect the assets, to make lists of contributories and creditors, to have disputed cases adjudicated upon, to realise the assets and to apply the proceeds in due course of administration amongst the creditors and contributories.[13]

Liquidators also have a number of specific obligations and duties imposed under the taxation legislation. In particular, as a liquidator is deemed to be a “trustee” for the purposes of the taxation laws,[14] s 254(1) of the ITAA36 applies. As a consequence, a liquidator is answerable for the doing of all such things as are required to be done under the legislation in respect of the income, or any profits or gains of a capital nature, derived in his or her “representative capacity”.

A liquidator also has specific obligations and liabilities under Subdiv 260-B of Sch 1 to the TAA in relation to the “outstanding tax-related liabilities” of a company placed in liquidation.[15] A company has an “outstanding tax-related liability” at a “particular time” if it has a “tax-related liability” that has arisen at or before that time (whether or not it is due and payable at that time) which has not been paid before that time.[16] A “tax-related liability” is “a pecuniary liability to the Commonwealth arising directly under a taxation law (including a liability the amount of which is not yet due and payable)”.[17] A “taxation law” includes any Act of which the Commissioner of Taxation (“Commissioner”) has the general administration or any regulation under such an Act.[18] A tax-related liability would therefore include not only the company’s income tax liability, but also, for example, its Withholding Tax, Fringe Benefits Tax, Goods and Services Tax and Pay As You Go liabilities.[19]

Under Subdiv 260-B, a person appointed as a liquidator of a company must, within 14 days of being appointed, notify the Commissioner in writing of his or her appointment.[20] The Commissioner must then, as soon as practicable, notify the liquidator of the amount the Commissioner considers is enough to discharge any “outstanding tax-related liabilities” that the company has when the notice is given.[21] The liquidator is prohibited from parting with

any assets of the company until the Commissioner has given the relevant notice.[22] This rule does not apply to secured debts and unsecured debts that are required under an “Australian law”[23] to be paid in priority to the other debts of the company.[24] In this regard, it should be noted that s 556 of the Corporations Act provides that certain debts have priority to all other unsecured debts. Ranking first in priority are the expenses properly incurred by the liquidator in preserving, realising or getting in property of the company or in carrying on the company’s business. Ranking behind this, are a range of other debts relating to the winding up of a company and certain other specified debts including employee wages and superannuation contributions. A company’s tax debts do not, however, receive any special priority and therefore the Commissioner stands in the shoes of an ordinary unsecured creditor.

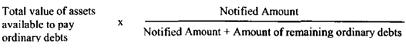

After receiving the Commissioner’s notice, the liquidator must set aside an amount out of the assets of the company which are available to pay ordinary debts,[25] assets with a value calculated according to the following formula:[26]

The liquidator must discharge the company’s outstanding tax-related liabilities to the extent of the value of the assets that the liquidator is required to set aside according to the above formula.[27] If a liquidator contravenes this requirement, the liquidator will be personally liable to discharge the liabilities, to the extent of that value.[28]

The following example illustrates the operation of this rule:

Example 1

A company has the following assets and liabilities:

● Total assets valued at $10,000,000;

● Secured debts of $4,000,000;

● Priority debts of $1,000,000;

● Notified amount of $3,000,000;

● Other liabilities of $7,000,000.

The amount available to pay ordinary debts will be the total value of the assets less secured and priority debts:

$10,000,000 - $4,000,000 - $1,000,000 = $5,000,000.

The value of the assets which are to be set aside are:

$5,000,000 x ($3,000,000/($3,000,000 + $7,000,000) = $1,500,000.

The liquidator is therefore required to apply $1,500,000 in discharge of the outstanding tax-related liabilities of the company.

In the case of a solvent winding up, a liquidator will be making distributions to the company’s shareholders and it is therefore important to determine how these distributions are treated for tax purposes.

It is a well entrenched principle of corporate and tax law that a distribution of a company’s profits to its shareholders represents a “detachment”, “release” or “liberation” of the profits of the company to them.[29] Based on trust law principles, such a distribution constitutes income at common law “and no statement of the company or its directors can change it from income into corpus”.[30]

The position is, however, quite different where a company goes into liquidation and the mass of its assets (which might include accumulated profits or profits earned up to the date of distribution) are distributed to its shareholders. In such a case, the amount distributed represents capital in the hands of shareholders under the common law. This concept has been explained by Hill J in FC of T v Brewing Investments Ltd[31] as follows:

In such a case shareholders are returned the ultimate capital value of the intangible property constituted by their shares which no longer exist. Profits are not detached, released or liberated leaving the share in tact.[32]

The above principle is based on High Court authority found in C of T v Stevenson (“Stevenson”)[33] where a majority of the Court[34] rejelted the Commissioner’s argument that, on the winding up of a company, a shareholder should be assessed on a distribution to the extent that it represented undistributed profits of the company. Rich, Dixon and Mc Tiernan JJ drew a distinction between “distributions or detachments of profit by a company as a going concern” and “distributions in retirement or extinguishment of shares”.[35] Relying on, inter alia, the United Kingdom Court of Appeal decision in IRC v Burrell (“Burrell”),[36] their Honours stated that in a winding up:

The shareholder simply receives his proper proportion of a total net fund without distinction in respect of the source of its components and he receives it in replacement of his shares.[37]

To ensure that the profits of a company do not escape tax simply because they are distributed in the course of its winding up, s 47(1) was inserted into the ITAA36. This provision works in conjunction with s 44(1) of the ITAA36. The combined effect of these provisions is to reverse the common law rule established in Burrell and Stevenson with the result that certain distributions by liquidators will be assessable income in the hands of a company’s shareholders in the same way as if they were ordinary dividend distributions paid by the company.

Section 47(1) provides that:

Distributions to shareholders of a company by a liquidator in the course of winding up the company, to the extent to which they represent income derived by the company (whether before or during liquidation) other than income which has been properly applied to replace a loss of paid-up share capital, shall, for the purposes of this Act, be deemed to be dividends paid to the shareholders by the company out of profits derived by it.

The first point to recognise about s 47(1) is that it can only apply where a “distribution” is made by a “liquidator”. It therefore had no application in FC of T v Blakely[38] which concerned a company whose assets had been appropriated by its shareholders without it being placed in formal liquidation.

The second point to recognise about s 47(1) is that it is merely a deeming provision. It does not, by itself, make any amount assessable income and it therefore does not operate as a “statutory income” provision within the meaning of that term in s 6-5 of the ITAA97. Rather, it is only when s 47(1) operates in conjunction with s 44(1) that any amount is brought to account as assessable income.

Section 44(1) includes in the assessable income of a shareholder in a company:

a) if the shareholder is a resident - “dividends ... that are paid to the shareholder by the company out of profits derived by it from any source”; and

b) if the shareholder is a non-resident - “dividends ... paid to the shareholder by the company to the extent to which they are paid out of profits derived by it from sources in Australia”.

Importantly, the deeming under s 47(1) is a “complete deeming” for the purposes of s 44(1) in that it not only renders the relevant distribution to be a dividend, but it also deems that it is paid to shareholders by the company out of profits derived by it. In other words, the effect of the deeming is that the relevant distributions will automatically be assessed under s 44(1) unless excluded by either the jurisdictional limitations of the provision or a specific exclusion provision contained elsewhere in the legislation (see further the discussion at 4.2.3(c) below).

Over the years a significant body of complex case law has evolved in relation to s 47(1). The key issues that have confronted the courts have concerned the scope of the expressions:

• “income derived by the company” (see 4.2.1); and

• “income which has been properly applied to replace a loss of paid-up share capital” (see 4.2.2).

In addition, the courts have also been required to consider whether s 47(1) has any territorial limitations (see 4.2.3).

Prior to the introduction of s 47(1A) in 1987, there was uncertainty as to whether s 47(1) only applied to amounts that were “income” of a company at common law or whether it also extended beyond this to amounts which were “assessable income” of the company because of specific statutory income provisions. The debate was fuelled by conflicting cases - in particular the High Court decisions in Gibb v FC of T (“Gibb”)[39] and Harrowell v FC of T (“Harrowell”).[40]

The High Court in Gibb adopted a narrow view of the term “income” in s 47(1). Gibb involved a distribution made by a liquidator to a shareholder of a company (“Gibbsons”) out of its bonus share reserve. Gibbsons had credited its bonus share reserve after selling bonus shares it had received from another company (“Gibb & Miller”). The bonus shares constituted a “dividend” in the hands of Gibbsons under the definition of that term in s 6(1) of the ITAA36 since they represented “the paid-up value of shares distributed by a company to its shareholders to the extent to which the paid-up value represents a capitalisation of profits”. However, the dividend was not assessable under s 44(1) because of former

s 44(2)(b)(iii). This provision operated to exempt dividends paid wholly and exclusively out of profits arising from the sale or a revaluation of assets not acquired for the purpose of re-sale at a profit where the dividends were satisfied by the issue of shares.

The Commissioner argued that the word “income” in s 47(1) should be interpreted broadly to encompass any amounts that were income under the Act and that, based on the majority judgment of Fullagar and Menzies JJ in FC of T v WE Fuller Pty Ltd (“WE Fuller”),[41] this included amounts falling within the definition of dividend in s 6(1). However, a majority of the High Court[42] rejected this argument. According to the majority, the term “income” in s 47(1) only encompassed “income according to ordinary concepts”. In their joint judgment Barwick, McTiernan and Taylor JJ held that s 6(1) merely defined the term dividend and did not invest the bonus shares with the character of income.[43] In this respect, their Honours preferred to follow the dissenting judgment of Dixon CJ in WE Fuller where the Chief Justice had stated that “the conception of ‘dividend’ does not affect the meaning or application of the word ‘income’”.[44]

In contrast to Gibb, the High Court decision in Harrowell indicates that amounts which were not income at common law could constitute income for the purposes of s 47(1). In Harrowell, the taxpayer had received a distribution from the liquidator of a company (“Glenville”). Glenville had made the distribution out of an amount it had received from the liquidator of another company (“Killens”). The amount paid by the liquidator of Killens was paid out of that company’s trading profits and was therefore assessable income of Glenville by virtue of the operation of s 47(1) (ie since it was paid out of income of Killens). Although the distribution received by Glenville was not income at common law (based on Stevenson), the High Court held that the amount was, for the purposes of the Act, income of Glenville and therefore assessable to the taxpayer when subsequently distributed by the liquidator.

While it is difficult to reconcile Gibb and Harrowell, the issue is now largely academic as s 47(1A) specifically deems that for the purposes of s 47(1) “income derived by a company” includes a reference to:

a) an amount (except a net capital gain) included in the company’s assessable income for a year of income; or

b) a net capital gain that would be included in the company’s assessable income for a year of income if the ITAA97 required a net capital gain to be worked out according to the following method statement:

Method Statement

Step 1 Work out each capital gain (except a capital gain that is disregarded) that the company made during that year of income. Do so without indexing any amount used to work out the cost base of a CGT asset.

Step 2 Total the capital gain or gains worked out under Step 1. The result is the net capital gain for the year of income.

Importantly, the above method statement not only ignores indexation when calculating the net capital gain for the purposes of s 47(1) but also does not take into account capital losses. As a result, a company’s “statutory income”, its “accounting income” and its “s 47 income” will not necessarily be equal.

The following example illustrates this point:

Example 2

Company X has three assets - Asset A, Asset B and Asset C. Each asset was acquired for $100 and has an indexed cost base of $130. During the current year, Company X disposes of Asset A for $60, it disposes of Asset B for $120 and it disposes of Asset C for $180.

Statutory Income

For the purposes of the CGT rules, Company X has made a capital loss of $40 in respect of Asset A, it has made no capital gain or capital loss on the disposal of Asset B and it has made a capital gain of $50 on the disposal of Asset C. This results in it having a net capital gain of $10 for the year under s 102-5.

Accounting Income

For accounting purposes, Company X has made a loss of $40 in respect of Asset A, a profit of $20 on Asset B and a profit of $80 on Asset C. This results in it having accounting income of $60.

Section 47(1) Income

In calculating its net capital gain for the purposes of s 47(1), Company X ignores the loss made in respect of Asset A and it calculates its gains in respect of Asset B and Asset C without regard to indexation (ie it makes a $20 gain in respect of Asset B and an $80 gain in respect of Asset C). It therefore has a net capital gain of $100 for the purposes of s 47(1).

The meaning of the expression “income which has been properly applied to replace a loss of paid-up share capital (formerly ‘paid-up capital’)” was considered by the High Court in Archer Brothers Pty Ltd v FC of T.[45] This case involved a private company that had been placed into voluntary liquidation during the 1949 income year. The company’s taxable income for the year was £45,703 and, as a consequence, it was required to distribute dividends of £28,030 to its shareholders within a prescribed time or be subject to undistributed profits tax under former Div 7 of Pt III of the ITAA36. The liquidator had made several distributions of company income to its shareholders during the year. However, as the company had a deficiency of capital at the time, the distributions were treated as replacements of this deficiency rather than dividends under s 47(1). The Commissioner considered that this treatment meant that there had not been a sufficient distribution of dividends with the result that the company was liable to pay undistributed profits tax. This conclusion was found to be correct by the High Court which held that it would have been possible for the liquidator to make distributions which satisfied the sufficient distribution rules if it had not treated the distributions as a replacement of paid-up capital. In the course of their judgment, Williams ACJ, Kitto and Taylor JJ stated:

By a proper system of book-keeping the liquidator, in the same way as the accountant of a private company which is a going concern, could so keep his accounts that these distributions could be made wholly and exclusively out of those particular profits or income ...[46]

The above passage from Archer Brothers was considered by the High Court a decade later in Glenville Pastoral Co Pty Ltd v FC of T.[47] This case also involved a private company’s liability to undistributed profits tax. The company (“Glenville”) owned shares in a wholly-owned subsidiary (“Killens”) which had gone into voluntary liquidation. The liquidator of Killens had made £243,402 of distributions to the taxpayer which were deemed to be dividends under s 47(1). Glenville was also placed into voluntary liquidation and its liquidator made a distribution to its shareholders of £241,669 which was made up of the deemed dividends received from Killens. It was contended that the whole of this distribution was a dividend by virtue of s 47 and that there had therefore been a sufficient distribution of dividends to avoid any undistributed profits tax liability.

The Commissioner, however, considered that only £82,298 of the total distributions made by the taxpayer’s liquidator constituted a dividend under s 47. According to the Commissioner, the remaining £159,271 of the distribution represented income which had been applied to replace a loss of paid-up capital, since after the liquidator had made the distribution of £241,669 the taxpayer’s funds fell short of its paid-up capital by this amount.

The High Court concluded that the Commissioner had wrongly treated £159,271 of the distribution as representing income applied to replace a loss of paid-up capital. The Court held that the whole distribution should have been treated as a dividend and consequently there had been a sufficient distribution of dividends. The High Court relied on Burrell for the proposition that a company can only capitalise profits which it is a going concern and that a liquidator has no power to capitalise profits. The Court expressly indicated that Archer Brothers should not be taken as supporting a view that a liquidator may capitalise profits. According to the High Court, the statement in Archer Brothers that “by a proper system of bookkeeping the liquidator, in the same way as the accountant of a private company which is a going concern, could so keep his accounts that these distributions could be made wholly and exclusively out of those particular profits or income” relates only to the selection of one income source rather than another for the payment of a particular distribution. The Court observed that while it is true that Archer Brothers was decided on the assumption that the liquidator in that case had, in making a distribution to shareholders, applied profits to replace paid-up capital, this was an assumption made by both parties in the case and the Court was accordingly obliged to proceed on that basis.

In the light of Glenville, it is apparent that only a solvent company can capitalise profits to make up a deficiency of paid-up capital. In other words, despite what was said in Archer Brothers, liquidators cannot do this. However, nowadays companies will be reluctant to capitalise profits because this will usually attract the operation of the share capital account tainting rules in Div 7B of Pt IIIAA of the ITAA36. A company “taints” its share capital account where it transfers an amount to its share capital account from any other account.[48] Generally, companies do not want to taint their share capital accounts because the tainting can generate franking debits in their franking accounts[49] and amounts paid out of a tainted share capital account will constitute dividends[50] which are not frankable[51] and do not benefit from the inter-corporate dividend rebate.[52]

Leaving aside the issue about capitalising profits, Glenville does not impinge on the broader principle which seems to arise from Archer Brothers that a liquidator is generally free to determine how a distribution is made (ie the order in which funds available are appropriated in winding up the company). The ATO’s interpretation of the Archer Brothers principle is outlined in Taxation Determination TD 95/10 where it is stated that:

The principle is that if a liquidator appropriates (or “sources”) a particular fund of profit or income in making a distribution (or part of a distribution), that appropriation ordinarily determines the character of the distributed amount for the purposes of section 47 and other provisions of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936.[53]

In general, the Australian Taxation Office (“ATO”) accepts that a liquidator may rely on the Archer Brothers principle when making distributions.[54] In the light of this, it has been suggested that for the purposes of the operation of s 47, it would be prudent for a company to arrange its accounts in such a way that a liquidator can readily distinguish between capital reserves relating to assets acquired before the introduction of CGT on 20 September 1985 and assets acquired on or after that date.[55] This will be particularly relevant where a company has made both capital gains and capital losses in respect of assets acquired on or after 20 September 1985. This is because, while gains in respect of these assets give rise to income for the purposes of s 47, losses in respect of these assets do not reduce the amount of such income. Nevertheless, the losses do reduce the cash funds that are available to the liquidator for distribution. This point and its implications are recognised by the ATO in Draft Taxation Determination TD 1999/D48 where it is stated that:

capital losses may lead to a loss of distributable funds so that a notional capital gain calculated under Step 2 of the method statement in paragraph 47(1A)(b) cannot be distributed. In this case, the requirement in paragraph 47(1A)(b) to disregard capital losses in recalculating a notional capital gain may have no practical effect.

The Draft Determination goes on to state that s 47(1) “cannot operate to deem any more than the amount actually distributed to be a dividend”. This means that, to the extent that the s 47 income of a company exceeds the amount available to a liquidator for distribution, it will not be subject to tax in the hands of shareholders. When this concept is considered together with the Archer Brothers principle it is evident that the way in which a liquidator appropriates the funds available for distribution will dictate the tax treatment in the hands of shareholders. A consequence of this is that it may be possible for the liquidator to make “tax-effective” distributions where the company has pre-CGT capital gains. This is illustrated in the following example:

Example 3

Assume that a company is placed into liquidation and that its accounts indicate as follows:

Paid-up capital $20,000

Capital reserves

Pre 20 September 1985 capital gain $10,000

Post 19 September 1985 capital gain: $130,000

Post 19 September 1985 capital loss: ($125,000) $5,000

Retained earnings $15,000

Cash funds available for distribution $50,000

For the purposes of s 47 the company’s income is calculated as follows:

Post 19 September 1985 capital gain $130,000

Retained earnings $15,000

Section 47 income $145,000

Archer Brothers would seem to allow the liquidator to distribute the $50,000 cash funds in the following order:

1) $20,000 as a return of paid-up capital;

2) $10,000 in respect of the pre-20 September 1985 capital gain; and

3) $20,000 in respect of either the post 19 September 1985 capital gain or retained earnings.

In other words, although the company’s income for the purposes of s 47(1) amounts to $145,000, assuming it has resident shareholders, these shareholders will only be assessed under s 44 in respect of $20,000 as this is the amount of the distribution that represents income.

The Archer Brothers principle should not be viewed in isolation. Rather, it needs to be considered in the context of the broader tax scheme which includes the “CGT regime”.

While a liquidator can determine the source from which distributed funds have been appropriated and this may enable the liquidator to limit the amount that might otherwise be assessable to shareholders as a dividend (as a consequence of s 47(1)), non-assessable amounts distributed by liquidators might still be taxed because of the operation of the CGT rules. In particular, as will be discussed below (see 5.1.1), the liquidation of a company ordinarily results in the happening of CGT event C2 in respect of the shares and all amounts distributed by a liquidator (whether or not assessable as dividends in the hands of shareholders) will form capital proceeds in relation to that event. This means that non-assessable amounts effectively add to the amount of any capital gain or reduce the amount of any capital loss that a shareholder might otherwise make. In this respect, the CGT rules can “clawback” some of the benefits otherwise afforded by making a tax effective distribution utilising the Archer Brothers principle.

The CGT “clawback” will, however, only be relevant where the shareholder’s shares were acquired after the introduction of CGT on 20 September 1985 and where the gains are not otherwise exempt from CGT (see 5.1).

Moreover, it should also be noted that while the CGT rules may operate to include a capital gain in a shareholder’s assessable income as a result of the liquidation of a company, in calculating the gain, the shareholder may be entitled to index the cost base of the shares or benefit from the CGT “discount rule” in Div 115 of the ITAA97 (see 5.1). In other words, the CGT regime provides certain “tax preferences” that are not available under the general rules. On the other hand, it should also be borne in mind that while a dividend is fully assessable, it may have franking credits attached to it which would operate to reduce a taxpayer’s tax liability (see 4.2.5).

The issue as to whether s 47 operates subject to territorial limitations was first considered by the High Court in Parke Davis & Co v FC of T.[56] This case concerned a non-resident taxpayer that was incorporated in the United States and which had a wholly-owned United States subsidiary company that had an Australian branch. The United States subsidiary was placed in liquidation and distributions were made to the taxpayer. These distributions included, in part, profits derived from the subsidiary’s Australian branch operations.

The taxpayer was assessed on so much of the liquidation distributions which represented a distribution of profits from the United States subsidiary’s operations in Australia. According to the Commissioner, the distributions fell within s 44(1)(b) on the grounds that they were deemed to be dividends paid to the taxpayer by its subsidiary and these dividends had been paid out of profits sourced in Australia.

The High Court confirmed the assessment and in doing so rejected the taxpayer’s contention that the deemed dividends did not have an Australian source and fell within s 23(r) of the ITAA36 which exempted income derived by a non-resident from sources outside Australia. According to the High Court, s 44(1) provided the territorial criteria for including dividends in assessable income and “there was no ground for adding territorial restrictions to s 47”.[57]

This “unrestricted” view of s 47 was recently followed by the Full Federal Court in FC of T v Brewing Investments Ltd.[58] Brewing Investments concerned a cascading liquidation of a chain of companies. The taxpayer (“BIL”) was an Australian resident company at the top of the chain. It owned all the shares in “Rowsom” which owned all the shares in “Clarkson” which, in turn, owned all the shares in “EIL”. Rowsom, Clarkson and EIL were all non-resident companies and did not derive any Australian source income.[59]

Clarkson went into voluntary liquidation in 1991 and its assets were distributed to Rowsom. EIL then went into voluntary liquidation in 1993 and its assets were also distributed to Rowsom. At the same time, Rowsom was placed in voluntary liquidation and BIL received US$70,238,424 from Rowsom’s liquidator which comprised:

• US$38,524,959 (representing a return of paid-up capital);

• US$4,359,855 (representing Rowsom’s retained earnings); and

• US$27,453,610 (representing part of Rowsom’s capital profits reserve).

The issue before the Court was whether the Australian dollar equivalent of the US$27,453,610 amount was assessable to BIL.[60] This amount comprised all of Clarkson’s and EIL’s income reserves which had been paid to Rowsom as a consequence of the liquidation of those companies.

BIL argued that it should not be assessed on the relevant amount on the basis that the distributions of the income reserves made by the liquidators of Clarkson and EIL to Rowsom did not constitute income of Rowsom for the purposes of s 47(1) since Rowsom was a non-resident and the distributions had a foreign source.

The Commissioner did not accept this argument and submitted that s 47(1):

• deals with a transaction according to its character;

• applies independent of considerations of locality;

• deems what the shareholder receives from the liquidator to be, for all purposes of the Act, income derived by the shareholder; and

• is not confined to bringing distributions within s 44(1).

According to the Commissioner, these propositions meant that if a distribution has its source in an earlier liquidator’s distribution, then if the earlier distribution falls within s 47(1) – that is, it represents income derived by the company making the first distribution – it necessarily follows that the later distribution is a distribution to which s 47(1) applies. On this basis, it was submitted that BIL should be assessed under s 44(1) on the Australian dollar equivalent of US$27,453,610.

The Full Federal Court accepted the Commissioner’s arguments. The crux of the Court’s judgment is found in the following passage from the judgment of Hill J (with whose judgment Heerey and Sundberg JJ concurred):

... section 47(1) has no territorial limitation at all. That territorial limitation is to be found in s 44(1). To use the language of Parke Davis and the Commissioner’s second submission, s 47(1) is independent of considerations of locality. That locality is supplied by s 44(1) and for this purpose the deeming in s 47(1) provides the touchstone for the application of s 44(1). This, however, says nothing about the deeming required by s 47(1) so far as it is sought to be applied to a series of liquidation distributions such as the present case raises.

While it is true that s 47(1) cannot operate by itself to make a distribution assessable income, it can operate “for the purposes of the Act” on its own as we have seen. So, when Clarkson was liquidated, the resultant distribution was treated for the purposes of the Act as a dividend paid out of profits and thus income. Thus when Rowsom was liquidated the resultant distribution was, by the application of s 47(1) to the Clarkson distribution, to be treated as income and in the result there was deemed to be a distribution to BIL, being a dividend paid out of profits to which the terms of s 44(1) then fell to be applied.[61]

The Brewing Investments decision represents the broadest possible view that could be taken of s 47 and is a major victory for the Commissioner. It, perhaps, should be noted that the result is not necessarily “anomalous” since, if the amount had been distributed prior to liquidation, it would have been treated as an assessable dividend in the hands of BIL and the result would, therefore, have been the same.

While Brewing Investments demonstrates that the operation of s 47 is not curtailed by territorial limitations, it needs to be understood that s 44(1) does not operate by paramount force. Accordingly, just because s 47 deems an amount to be a dividend paid to a company’s shareholders out of profits derived by it, this does not mean that the amount will automatically be assessable under s 44(1). Section 44(1) expressly does not apply to a dividend to the extent that another provision in the legislation excludes the dividend from a shareholder’s assessable income. [Accordingly, to the extent that a distribution by a liquidator falls within, inter alia, the following exemption provisions, it will not be assessable:]

• s 23AI of the ITAA36 (which exempts dividends paid out of previously attributed income of a Controlled Foreign Company (“CFC”));

• s 23AJ of the ITAA36 (which exempts “non-portfolio dividends” to the extent to which they are “exempting receipts”); or

• s 128D of the ITAA36 (which exempts dividends that are subject to Withholding Tax[62] or which are exempt from Withholding Tax because they are franked).

Special issues also arise in respect of liquidations of CFCs under Pt X of the ITAA36. While it is outside the scope of this article to explore these issues in detail, it should be noted that s 47 will be relevant in determining the attributable income of a CFC. It should also be noted that the statutory accounting period of a CFC will end when it ceases to exist (eg when it is de-registered following liquidation) so that it will be necessary to determine its attributable income for the period up to its de-registration.

Subject to carve out rules, a dividend includes “any distribution made by a company to any of its shareholders, whether in money or other property”.[63] To the extent that relevant distributions are paid by a company to its shareholders out of “profits” derived by it, they will be assessable under s 44(1) unless jurisdictional rules or specific exemptions provide otherwise.

The concept of “profits” for the purposes of s 44(1) is based on the corporate law meaning of that term which does not take into account considerations of whether or not such profits were assessable to the company that paid the dividend.[64] In other words, the tax character of the profits in the hands of the company paying the dividend is irrelevant in determining whether those profits are assessable when subsequently distributed as a dividend to the company’s shareholders. The effect of this is that a distribution by a company of its non-taxable capital profits (eg gains made by a company on assets acquired before the introduction of CGT) will generally be assessable to shareholders as a dividend under s 44(1). In contrast, as discussed above, a similar distribution made by a liquidator would not be assessable as it does not constitute “income” derived by the company for the purposes of s 47.

This means that, in certain cases, it may be more tax efficient to wind up a company and make distributions to shareholders via a liquidator rather than via an ordinary dividend distribution from the company while it is a going concern.[65] This will be the case, if the company has any pre-CGT capital gains.

For imputation purposes, a frankable dividend includes a distribution that is deemed to be a dividend under s 47(1).[66] As a result, liquidators of resident companies will need to consider the extent to which deemed dividends that they pay are to be franked. In particular, they should endeavour to ensure that they do not waste valuable franking credits that the company has earned by paying tax over the years.

In a solvent winding up, when considering how to distribute the funds of a company, a liquidator should note that franking credits will only attach to those distributions which are deemed to be dividends under s 47. In other words, franking credits will not attach to a return of paid-up capital or a distribution of capital reserves which relates to gains on assets acquired by the company before 20 September 1985, since these amounts will not be dividends pursuant to s 47.

While a liquidator might be inclined to use the Archer Brothers principle to prioritise non-dividend distributions ahead of dividend distributions, the liquidator should be aware that certain shareholders may actually prefer to receive dividends which are franked ahead of non-assessable amounts. Shareholders that fall within this class would include resident individuals who pay tax below the corporate tax rate. This is because, to the extent that the imputation credits exceed the tax payable by these shareholders on the deemed dividends they receive, the excess imputation credits may be offset against their other income tax liabilities and any excess amounts remaining thereafter are refundable.[67] It should be noted, however, that there are various anti-streaming and anti-avoidance rules in relation to the payment of franked dividends or the distribution of capital amounts to prevent streaming of distributions among shareholders with different tax profiles.[68]

Obviously, there may be situations in which franking surpluses would remain after distribution of all the available funds of a company. In such a case, the winding up of the company means that this surplus will inevitably be wasted. For this reason, it may be inappropriate to proceed with a winding up of a solvent company.

In general, the liquidation of a company will produce CGT consequences for the company’s shareholders. This is because a share in a company is a “CGT asset” within the meaning of that term in s 108-5 as it constitutes “property”.[69]

CGT consequences will, however, obviously not arise in respect of those shares that fall within a specific “exemption provision”. This includes:

• shares that were acquired prior to the introduction of CGT on 20 September 1985;[70]

• shares in a company that is registered as a pooled development fund;[71] and

• shares that are held as trading stock.[72]

In addition, the liquidation of a company will only produce CGT consequences for a non-resident shareholder in respect of those shares that have the “necessary connection with Australia”.[73]

From the perspective of a company’s shareholders, there are three specific CGT events that need to be considered in the context of liquidations:

• CGT event C2;

• CGT event G1; and

• CGT event G2.

While there is no provision in the Corporations Act that specifically states that shares are “cancelled” upon a company’s deregistration, the better view is that this is what actually occurs. Accordingly, the deregistration of a company would therefore result in CGT event C2 happening in relation to a shareholder’s shares in the company. This CGT event arises where a taxpayer’s ownership of an intangible asset “ends”, inter alia, as a result of it being “cancelled”.

The time of the CGT event would usually be determined by s 104-25(2)(b) which deems that, where there is no contract that results in the asset ending, the time of the CGT event is when the asset ends. This would be when the deregistration takes place (rather than when the liquidation commences). As noted in Taxation Determination TD 2000/7, the time at which deregistration occurs will depend on the circumstances of the deregistration. In cases involving court ordered winding ups, deregistration would typically occur when the court orders ASIC to deregister the company. Otherwise, in the case of a voluntary winding up, ASIC must ordinarily deregister a company three months after the liquidator lodges a return of the holding of the final meeting of members (or of members and creditors).[74]

Under CGT event C2 a shareholder will realise:

• a capital gain – if the capital proceeds from the ending of the shares are more than the cost base of those shares; or

• a capital loss – if the capital proceeds from the ending of the shares are less than the cost base of the shares.[75]

The cost base and capital proceeds of the shares are determined under the ordinary rules contained in Divs 110 and 116 of the ITAA97 respectively. In other words, the cost base of the shareholder’s shares will ordinarily comprise the amount paid for the shares and relevant incidental costs in acquiring and holding them; while the capital proceeds will include the money or property (in the case of an in specie distribution) received from the liquidator on winding up.

For the purposes of calculating any capital gain, indexation of the cost base will generally be available in respect of shares acquired before 21 September 1999 pursuant to Div 114.[76] However, indexation is not available if the capital gain satisfies the discount capital gain requirements in Div 115 of the ITAA97. It should be noted that the discount rules only apply to certain taxpayers. In particular, the discount rules only apply to individuals, complying superannuation entities and trusts that have held a relevant asset for at least 12 months and have elected to calculate the amount of any capital gain without indexing the cost base of the asset.

As a liquidator’s distribution may also constitute a dividend under s 47(1), the potential for double taxation arises. This is because the distribution would generally otherwise be assessable under s 44(1) as well as forming part of the capital proceeds in relation to the CGT event. To overcome this result, s 118-20 of the ITAA97 operates to reduce the amount of the capital gain by the amount otherwise included in assessable income. Section 118-20 reduce the amount of a capital gain that a taxpayer makes from a CGT event “if, because of the event, a provision of this Act [which is deemed to include the ITAA36: s 995-1] outside this part [ie Pt 3-1]” includes an amount in the taxpayer’s assessable income. The gain is reduced to “zero” if it does not exceed the amount included in assessable income; otherwise it is reduced by the amount included in assessable income. The effect of this provision is illustrated in the following example:

Example 4

Assume a resident shareholder holds a share in a company which has a cost base of $10. The liquidator distributes $16 to the shareholder on winding up the company. Of this amount $14 represents a dividend for the purposes of s 47 which will be assessable to the shareholder under s 44(1).

Ignoring the operation of s 118-20 (and assuming indexation is not relevant), a $6 capital gain arises under CGT event C2 in respect of the share.

However, since the $6 capital gain does not exceed the $14 assessable dividend, the shareholder’s capital gain is reduced to $0 by virtue of s 118-20.

If, on the other hand, only $4 of the $16 liquidator’s distribution was a dividend, the capital gain that the shareholder would otherwise realise would be reduced by this amount leaving a capital gain of $2.

Interim liquidator distributions may be caught by CGT event G1 (rather than CGT event C2). CGT event G1 applies where a company makes a payment to a shareholder in respect of a share that the shareholder owns in the company[77] and some or all of the payment (the “non-assessable part”) is not a dividend or an amount taken to be a dividend under s 47.[78] A payment by a liquidator is specifically disregarded for this purpose if the company is dissolved within

18 months of the payment.[79] In such case, the payment will be part of the shareholder’s capital proceeds for CGT event C2.

Where CGT event G1 applies, the shareholder will make a capital gain if the amount of the non-assessable part is more than the share’s cost base.[80] In such case, the share’s cost base is reduced to nil.[81] However, if the amount of the non-assessable part is not more than the share’s cost base, the cost base and its reduced cost base are reduced by the amount of the non-assessable part.[82] The non-assessable part for this purpose would include a distribution paid out of a pre-CGT capital gain.

Shareholders that are paid interim liquidation distributions will often not know whether the company will be dissolved within 18 months of the distribution. This places them in a quandary in relation to how they prepare their tax returns. In Draft Taxation Ruling TD 2001/D2, the Commissioner has indicated that there are two courses of action open to the shareholder in such a case:

a) to anticipate that the company will be dissolved within 18 months; or

b) to apply CGT event G1 to the interim distribution on the basis that the company will not be dissolved within the 18 month period.

The draft Ruling indicates that it is only if the shareholder is advised in writing by the liquidator that the company will not be dissolved within 18 months of the distribution, that the shareholder must initially apply CGT event G1 to the interim distribution. The draft Ruling indicates that, in the absence of written advice from the liquidator that the company will not be dissolved within 18 months of the distribution, a shareholder may assume that the company will be dissolved within 18 months. However, if it turns out the company is not dissolved within 18 months of the interim liquidation payment, CGT event G1 will apply and it may therefore be necessary to amend the shareholder’s assessment for the relevant year.

As mentioned at 2.3 above, the transfer of shares made after the commencement of winding up is generally void.[83] Bearing in mind that the liquidation of a company may take a considerable time to finalise, the effect of this is that shareholders who are expecting to make capital losses may not be able to crystallise these for some time since they are not able to otherwise dispose of their shares.[84] In particular, shareholders who do not expect to receive any distribution from the liquidator will be disadvantaged because they will have to wait until the company is deregistered to realise the capital loss arising from the cancellation of their shares. CGT event G3 has been designed to address this problem. This CGT event happens to a shareholder if a liquidator declares in writing that he or she has reasonable grounds to believe (as at the time of the declaration) there is no likelihood that the shareholders in the company, or shareholders of the relevant class of shares, will receive any further distribution in the course of winding up the company.[85] The time of the CGT event is when the liquidator makes the declaration.[86] The shareholder may choose to make a capital loss at that time equal to the reduced cost base of his or her shares.[87] This therefore allows the shareholder to crystllise the imminent loss.

Where a shareholder exercises the choice under CGT event G3, the cost base and reduced cost base of the shareholder’s shares are reduced to nil. As a result, if distributions are in fact subsequently made to shareholders, the amount of such distributions will be fully taxed as a capital gain under CGT event C2 (if they are not taxed as a dividend).

While CGT event G3 will be of use to many shareholders, it will not apply to all shareholders that anticipate making losses on shares in companies which have gone into liquidation. For instance, it cannot apply while the liquidator believes there is a likelihood that some amount (however small that amount may be) will be distributed to shareholders.[88]

In many instances, it will be obvious to a liquidator that shareholders will receive no distributions. However, in other instances it may take a considerable amount of time for a liquidator to reach this conclusion and therefore it may be some time before the liquidator is prepared to make the requisite declaration.

It should be noted that CGT event G3 specifically refers to a “further distribution”. This wording is designed to clarify that a liquidator’s declaration may be made after a distribution has been made during a winding-up of a company. In other words, the making of an interim distribution does not preclude a later declaration by a liquidator.[89]

Section 109-15 provides that a CGT asset is not acquired if the asset was disposed of “because of the vesting of the asset in a liquidator of a company, or the holder of an office under a similar law”. The effect of this provision is the CGT regime operates as if the company which has gone into liquidation continues to hold the asset.

Furthermore, s 106-35 of the ITAA1997 provides that an act done by a liquidator of a company, or a holder of a similar office under a foreign law, is taken to have been done instead by the company. The consequence of this is that where a liquidator disposes of an asset in the course of winding up, it is the company which is treated as having made any gain or loss in relation to the asset.

An in specie liquidator’s distribution, like a cash distribution, may constitute a deemed dividend under s 47 and may therefore be assessable to the shareholder under s 44(1).[90]

An in specie liquidator’s distribution will also raise CGT issues where the asset involved was acquired by the company after 19 September 1985. As the effect of an in specie distribution is that there is a change in ownership of the asset from the company to the shareholder, this results in the happening of CGT event A1 (which arises where an entity “disposes” of an asset).[91] The capital proceeds from such disposal for the company in liquidation would be based on the market value of the asset at the time of the distribution as the company would otherwise not receive any capital proceeds.[92] Where an in specie distribution gives rise to a tax liability, the liquidator will obviously need to ensure that he or she retains sufficient funds to pay the tax.

It is important to realise that franking credits for the payment of tax arise at the time the tax is paid rather than at the time of the CGT event which gives rise to the liability (ie the in specie distribution). There may be insufficient credits in the company’s franking account to frank the in specie distribution at the time it is made. This gives rise to a “timing mis-match” problem. Indeed, there may be situations where franking credits only arise after the liquidator has exhausted all funds available for distribution as dividends. In these cases, the franking credits relating to the tax paid in respect of the in specie distribution will be wasted since there are no dividends to which they can be attached.

The discussion in this article has focused on some of the more important income tax issues that arise in the context of a liquidation of a company. Not surprisingly, the article reveals that the main issues will arise in the case of a solvent winding up. The article demonstrates that in such a case, different consequences will flow depending on how liquidators decide to make distributions and on timing issues. In the light of this, it is vital that liquidators carefully consider their options when making distributions in order to maximise the after-tax return for the company’s shareholders.

[*] Associate Professor, Monash University and Consultant, Blake Dawson Waldron.

[**] Partner, Blake Dawson Waldron.

[***] Solicitor, Blake Dawson Waldron.

[1] P Lipton and A Herzberg, Understanding Company Law (10th ed, 2001) 628.

[2] This may occur, for instance, where: all the members of the company agree to the deregistration; it is not carrying on business; its assets are worth less than $1,000; it has paid all fees and penalties; it has no outstanding liabilities; and it is not party to any legal proceedings: Corporations Act, s 601AA. In addition, ASIC may deregister a company if: its annual return is at least 6 months late; it has not lodged any other documents in the last 18 months; and ASIC has no reason to believe the company is carrying on business: Corporations Act, s 601 AB.

[4] Except so far as, in the opinion of the liquidator, required for the beneficial disposal or winding up of the business.

[5] A members’ voluntary winding up can only occur if the directors have provided a declaration of solvency prior to the date on which the notices of the meeting at which the resolution for winding up is proposed to be sent, otherwise the voluntary winding up must proceed as a creditors’ voluntary winding up and a meeting of the creditors must be convened: Corporations Act, s 494 and s 497.

[6] The other grounds on which a company may be wound up by a court are set out in s 461 (eg it suspends its business for one year, it has no members, or the affairs of the company are conducted in a manner that is oppressive or unfairly prejudicial to a member).

[9] Corporations Act, s 468(1).

[10] Ibid.

[11] Corporations Act, s 471 A.

[12] Corporations Act, s 468(4), s 500, s 471A and s 471B. Secured creditors rights are unaffected: Corporations Act, s 471C.

[13] Re Partridge; Ex parte McDonald [1961] SR (NSW) 622, 629 (per Evatt CJ, Herron and Sugerman JJ).

[14] Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (Cth) (“ITAA36”) (definition of “trustee”).

[15] The new Subdiv replaces former s 215 of the ITAA36 from 1 July 2000. If there are 2 or more liquidators, the obligations and liabilities under Subdiv 260-B apply to each of them but may be discharged by any of them: Tax Administration Act 1953 (Cth) (“TAA”), s 260-55.

[16] Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (Cth) (“ITAA97”), s 995-1.

[18] ITAA97, s 995-1.

[19] See further the summary of tax related liabilities in s 260-10 of the TAA. Note that Subdiv 260-B does not apply to the superannuation guarantee charge imposed by the Superannuation Guarantee Charge Act 1992 (Cth): TAA, s 260-40.

[20] TAA, s 260-45(2).

[21] TAA, s 260-45(3).

[22] TAA, s 260-45(4).

[23] An Australian law is essentially a Commonwealth, State or Territory law: ITAA97, s 995-1.

[24] TAA, s 260-45(5).

[25] The assets available to pay ordinary debts will be the assets remaining after payment of secured debts and debts which rank in priority for payment under an Australian law.

[26] TAA, s 260-45(6). For the purposes of the formula, the “amount of remaining ordinary debts” means the sum of the company’s ordinary debts other than the outstanding tax liabilities.

[27] TAA, s 260-45(7).

[28] TAA s 260-45(8). Failure to comply with this requirement is also an offence punishable by a fine of up to 10 penalty units ($1,100): TAA, s 260-50.

[29] FC of T v Brewing Investments Ltd 2000 ATC 4431, 4437 (per Hill J).

[30] Hill v Permanent Trustee Co of New South Wales Ltd [1930] AC 720, 734 (per Blanesburgh, Tomlin and Killowen LJJ) (“Hill”).

[31] 2000 ATC 4431.

[32] Ibid 4437.

[33] [1937] HCA 72; (1937) 59 CLR 80. See also Hill [1930] AC 720, 729 (per Blanesburg, Tomlin and Russell of Killowen LJJ).

[34] Rich, Dixon, McTiernan and Evatt JJ (Latham CJ and Starke J dissenting).

[35] [1937] HCA 72; (1937) 59 CLR 80, 103 (per Rich, Dixon and McTiernan JJ).

[37] [1937] HCA 72; (1937) 59 CLR 80, 99 (per Rich, Dixon and Mc Tiernan JJ).

[38] [1951] HCA 17; (1951) 82 CLR 388.

[39] [1966] HCA 74; (1966) 118 CLR 628.

[40] [1967] HCA 27; (1967) 116 CLR 607.

[41] [1959] HCA 41; (1959) 101 CLR 403.

[42] Barwick CJ, McTiernan, Taylor and Windeyer JJ (Owen J dissenting).

[43] [1966] HCA 74; (1966) 118 CLR 628, 635.

[44] [1959] HCA 41; (1959) 101 CLR 403, 409.

[45] [1953] HCA 23; (1953) 90 CLR 140.

[46] Ibid 155.

[47] [1963] HCA 36; (1963) 109 CLR 199.

[48] ITAA36, s 160ARDM(1).

[49] ITAA36, s 160ARDQ(1). The amount of the debit is based on the what would be the required franking amount of a frankable dividend calculated under s 160AQDB assuming the amount transferred to the share capital account were a frankable dividend paid to a shareholder in the company on the day the tainting occurred: ITAA36, s 160ARDQ(2).

[50] This is because a “tainted share capital account” is deemed not to be a “share capital account” under s 6D of the ITAA36.

[51]This is because a share capital account (even if it is tainted: see ITAA36, s 6D(3)) is treated as a “disqualifying account” for the purposes of s 46H(1) of the ITAA36. Dividends debited against disqualifying accounts are deemed not to be frankable by virtue of s 46M(3) and para (g) of the definition of “frankable dividend” in s 160APA of the ITAA36.

[52] ITAA36, s 46G. Again, this result flows because a share capital account is deemed to be a “disqualifying account”.

[53] Paragraph 2.

[54] Ibid.

[55] See R Deutsch, M Friezer, I Fullerton, M Gibson, P Hanley, W Plummer and T Snape, Australian Tax Handbook 2002 (2002) 881-882.

[56] [1959] HCA 15; 1959) 101 CLR 521.

[57] Ibid 530 (per Dixon CJ, Fullagar, Kitto, Menzies and Windeyer JJ).

[58] 2000 ATC 4431.

[59] Note that EIL actually did derive some Australian source income. The Commissioner did not, however, rely on this fact in the case.

[60] It was accepted that BIL should be assessed on the US$4,359,855 amount but not on the US$38,524,959 amount.

[61] 2000 ATC 4431, 4445.

[62] Withholding Tax generally applies to dividends paid by resident companies to non-residents: ITAA36, s 128B(1).

[63] ITAA36, s 6(1) (definition of “dividend”).

[64] See, for instance, FC of T v Slater Holdings Ltd [1984] HCA 78; (1984) 156 CLR 447. In determining what consitutes “profits”, the High Court in Slater Holdings referred, with approval, to the dictum of Fletcher Moulton LJ in Re Spanish Prospecting [1910] UKLawRpCh 125; [1911] 1 Ch 92 where his Lordship stated that:

“Profits” implies a comparison between the state of a business at two specific dates usually separated by an interval of a year. The fundamental meaning is the amount of gain made by the business during the year. This can only be ascertained by a comparison of assets of the business at the two dates.

The concept of what constitutes profits has also been considered more recently by Lockhart J in QBE insurance Group Ltd v ASC (1992) 10 ACLC 1490 where his Honour stated:

The meaning of the word “profits” is for the courts to determine. But the identification of what in relation to the affairs of a particular company constitute its profits is determined by the courts with close regards to the views of the accountancy profession. The courts are influenced by professional accountancy bodies and men of business and the evidence of accountants is given great weight.

[65] While it is outside the scope of this article to consider the issue, it should be noted that schemes designed to exploit this “tax benefit” may give rise to issues about whether or not the general anti-avoidance provisions in Pt IVA of the ITAA36 might come into play.

[66] ITAA36, s 160APA (definition of “frankable dividend”).

[67] ITAA97, Div 67.

[68] See further, R Woellner, S Barkoczy, S Murphy and C Evans, Australian Taxation Law 2002 (2002) 1178-1186.

[69] Section 1085(1)(a) of the Corporations Act declares that a share is “personal property”. The common law recognises a share as a form of intangible property in the nature of a “chose in action”: Archibald Howie Pty Ltd v C of SD (NSW) [1948] HCA 28; (1948) 77 CLR 143, 156. See also Note 1 to s 108-5 which specifically refers to shares in a company as a CGT asset.

[70] See, in particular, ITAA97, ss 104-25(5)(a) and 104-135(5). Note, however, that in limited cases, CGT may apply to certain shares acquired before 20 September 1985: see CGT event K6 (ITAA97, s 104-230).

[72] ITAA97, s 118-25. Such shares will be subject to the trading stock rules.

[73] ITAA97, s 136-10. Broadly, a share has the necessary connection with Australia if either it is a share in a resident private company or it is a share in a resident public company in which the shareholder (together with associates) held at least 10% of the shares at any time during the 5 years before the CGT event: ITAA97, s 136-25.

[74] Corporations Act, s 509(5). However, see also s 509(6).

[76] Note that indexation has been “frozen” from the September 1999 quarter.

[77] Note that CGT event G1 does not apply where CGT event A1 or C1 happens in relation to the share.

[81] Ibid.

[83] Corporations Act, s 468(1).

[84] Note that while a shareholder cannot transfer shares after the commencement of winding up, this does not prevent the shareholder declaring a trust over the shares. Such a declaration of trust might enable a shareholder to crystallise a capital loss pursuant to CGT event E1 (ITAA97, s 104-55). However, in some case, this kind of arrangement may be impractical and there may also be a risk that (in some cases) it could potentially attract the anti-avoidance provisions of Pt IVA.

[88] This view is confirmed in Taxation Determination TD 2000/52.

[89] See further the Explanatory Memorandum to the Tax Law Improvement Bill (No 1) 1998 which introduced the provision. Also contrast s 104-145 with its predecessor (former s 160WA of the ITAA36) which applied only where there was no likelihood that the shareholders in the company would receive any distributions in the course of winding up the company.

[90] For the purpose of determining whether any amount is assessable to the shareholder in respect of the distribution under s 47, it would seem that “real value” of the asset rather than its “book value” is relevant: Case B64 (1951) 2 TBRD.

[91] ITAA97, s 104-10. Note that under the present rules, roll-over relief would usually be available under Subdiv 126-B of the ITAA97 where an in specie distribution of an asset is made by a company in a wholly-owned group to its parent on liquidation.

[92] ITAA97, s 116-30.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/JlATax/2002/6.html