Journal of Australian Taxation

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Journal of Australian Taxation |

|

TOLLING COMPANIES

AND THEIR

INCOME TAXATION FEATURES[∗]

By Charles Birch[**]

This article critically examines the income tax characteristics (including compliance costs features) of tolling companies and compares them to those of unincorporated joint ventures and equity joint ventures.[1] It is argued that whilst tolling companies facilitate fiscal benefits for participants by transferring the incidence of income tax in respect of a business activity to them, the compliance costs of reaping these fiscal benefits may not be insignificant.

Participants seeking to combine selected characteristics of unincorporated joint ventures and equity joint ventures can do so through the use of a tolling company. Participants establish tolling companies to build, own and operate production facilities at which the raw materials owned by the participants in the joint venture will be processed into finished product for use or disposal by the participants individually. Tolling companies which carry on business for Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (Cth) (“ITAA97”) purposes transfer or “toll” their allowable deductions to the participants via a “tolling charge”. Tolling charges are unique to tolling companies. Each year, tolling companies charge the participants a processing or tolling charge equal to their allowable deductions for that year: tolling companies are fiscally transparent.

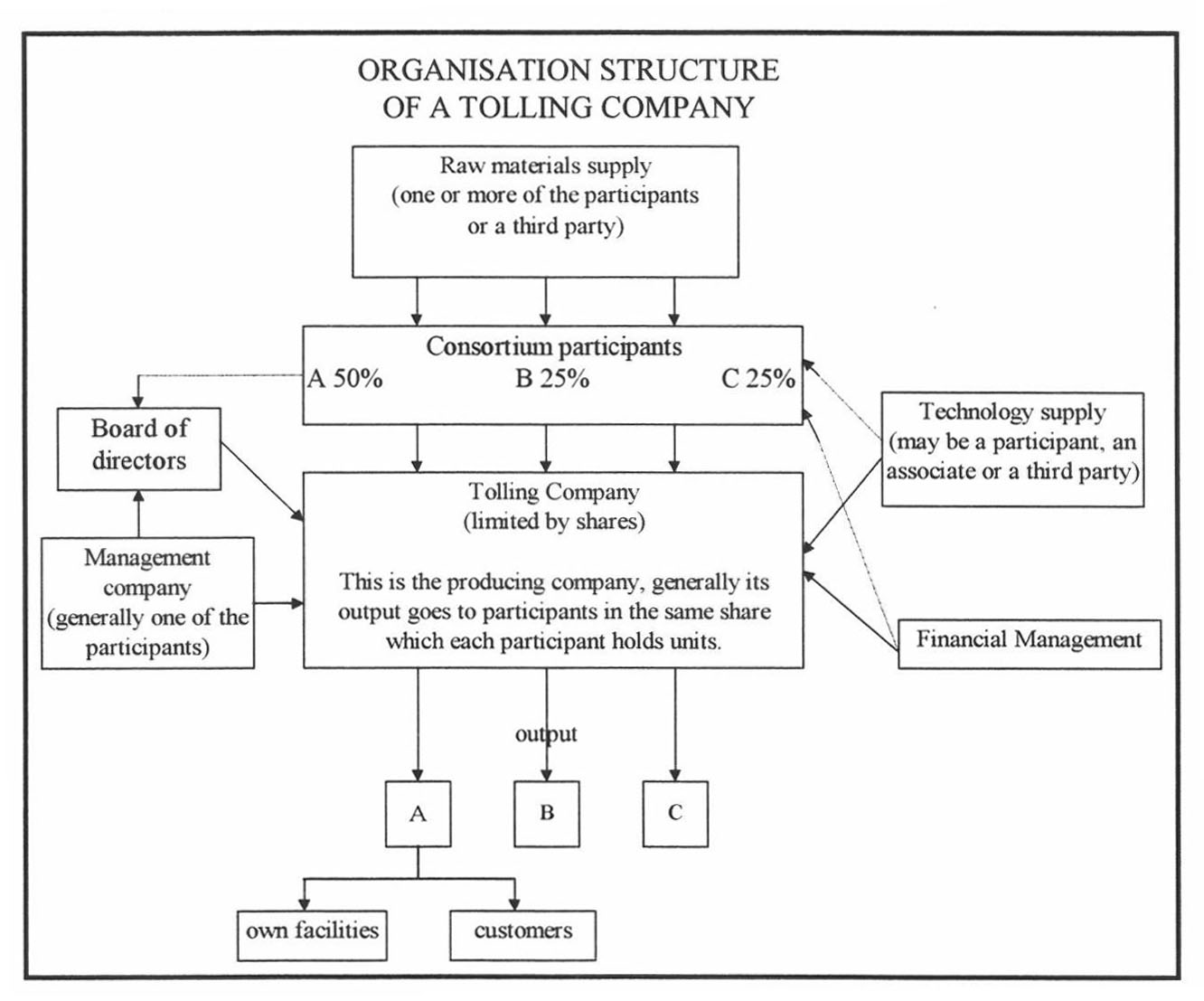

The expression “tolling company” is neither known to the Australian common law nor defined in the ITAA97 or the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (Cth) (“ITAA36”). Figure 1.1 usefully illustrates the interrelation of the participants to the tolling company and to the financiers. The operation of a tolling company structure can be illustrated by a simplified example.

Assume that a tolling company, which operates a gold refining plant, is owned 50% by Participant A, 25% by Participant B and 25% by Participant C. Participant A provides the tolling company with raw materials, Participant B provides technology and Participant C provides financial and general management services. In the 1999-2000 year of income, tolling company A incurs $150 million of tax-deductible expenditure (gold-refining costs, depreciation on plant, running costs etc). Pursuant to a tolling agreement, tolling company A charges Participants A, B and C a tolling fee in aggregate of $150 million in consideration for tolling company A refining gold during the year.

A tolling company arrangement allows participants to fund expensive capital works necessary for the refinement, transportation or conversation of raw materials extracted by the joint venture into a finished product for sale. An example of a tolling arrangement is the Portland Aluminium Smelter in Victoria, Australia, where bauxite is converted into aluminium ingots on behalf of the participants.[2] A tolling company is a hybrid creature - governed both by statute law (the Corporations Law) and by contract.

Tolling arrangements are said to have originated from techniques devised to deal with pipeline throughput contracts in the United States.[3] Pipeline throughput contracts deal with the terms and conditions on which the gas supplier will supply gas to the other party. The first known adoption of the tolling company concept in Australia was by a consortium of aluminium companies which built an alumina refinery at Gladstone, Queensland in the 1960s.[4] An aluminium smelter has also been established using a tolling company structure[5] at Boyne Island, Queensland. More recently, tolling companies have been utilised in the gold refining,[6] petroleum,[7] electrodes and other solid graphite products industries.[8]

Figure 1.1: Simplified Organisation Structure of a Tolling Company[9]

Participants of tolling companies incur costs in negotiating and preparing a tolling company’s constituent documents. These documents are necessary to create a tolling company structure. If it is assumed that a taxpayer will incur a flat fee to negotiate and prepare a contract, then the costs for a taxpayer establishing a tolling company structure might well be higher than for establishing an unincorporated joint venture or equity joint venture, because more contracts must be executed for tolling companies than for the other two joint venture structures. The components of such a flat fee may include management effort, in-house tax advisor labour costs, external lawyers’ fees and technical advisor costs.

Constituent documents are governed principally by a memorandum and constitution, participant’s agreement, tolling agreement and principal raw material supply agreements. There may also be other agreements.[10] The voluminous documentation requirements of tolling companies suggest that documenting unincorporated joint ventures is simpler and probably cheaper.[11]

It has been said that the constitution of a tolling company could contain provisions for preference shares.[12] If so, then a tolling company would either correspond to a participant or equity participant or their specially incorporated financing company (a SPFC or SPV, respectively) which issues preference shares to the financier. To that extent, a tolling company will be subject to the same income tax consequences. A constitution is required for equity joint ventures but not for unincorporated joint ventures (because the latter has no separate legal personality).[13]

The participants agreement is the core agreement. It defines the rights and obligations between the participants and the tolling company and between the participants inter se. This contract covers matters relevant to the establishment and limited role of the tolling company, its operation during the term of the agreement, the consequences and effects of the withdrawal or removal of any of the participants from the venture, the shareholding structure of the tolling company and, generally, restricting its use for the benefit of the participants only.[14] By analogy, Joint Venture Agreements (“JVAs”) perform a similar role for unincorporated joint ventures and shareholders’ agreements perform a similar role for equity joint ventures, subject to appropriate modifications[15] to take into account the peculiar aspects of each type of joint venture structure.

Tolling agreements exhibit similarities to shareholders’ agreements. Both are entered into between each of the participants and their special purpose vehicle (ie a tolling company or SPV). Their operation is similar to agreements utilised by both unincorporated joint ventures and equity joint ventures. Tolling agreements prescribe the rights and obligations of participants relating to tolling (or processing) of the basic raw material into the finished product.[16] As with the SPV of an equity joint venture, the tolling company owns the plant and equipment required in order to process raw materials into finished products and, as owner, is entitled to claim allowable deductions in respect of plant and articles.[17]

It will be seen below however, that because of the imposition of tolling fees, the benefit of the depreciation deductions for plant and articles in the tolling structure ultimately lies with the participants. This unique feature of tolling companies distinguishes them from the equity joint ventures. Unincorporated joint ventures produce the same result as in tolling company structures, but for a different reason. In the latter case, the individual owners are entitled to deductions for depreciation in respect of their separate percentage interests in the plant and articles as of right because of the proprietary rights of each individual participant in the assets of the unincorporated joint venture as a tenant in common. Therefore, unincorporated joint ventures involve no separation of ownership and control of the assets, whereas such separation is a feature of tolling companies.

In consideration for the services which the tolling company provides to the participants, the tolling company charges the participants a service or process fee.[18] This is known as a tolling charge and this is discussed at length below. The tolling charge is functionally different from the payment of cash calls (ie invoices issued by the tolling company to meet its cash needs) by participants of unincorporated joint ventures to the operator. In the latter case, the payment by each participant is designed to reimburse the operator for expenditure incurred by the operator on behalf of the participants. A tolling charge transfers the benefit of allowable deductions from the tolling company to the participant.

Pursuant to a principal raw material supply agreement, each of the participants severally contracts with the tolling company to provide the basic raw material to the tolling company, for processing at the production facilities. The sale of raw materials by a participant to the tolling company involves an acquisition of trading stock[19] by the tolling company and the tax features of this will be considered below. Where one of the participants is a producer of the basic raw material it would generally be the supplier under separate contracts with each of the other participants.[20] If more than one participant is in this position, they could each supply the raw material (as appropriate).

The nature of the interests of participants in tolling company arrangements is very similar to the nature of the interests of equity participants in an equity joint venture. There are similarities to unincorporated joint ventures as well. As with equity joint ventures, a participant’s interests in a tolling company consist of a complex hybrid of contractual rights and share ownership of the issued capital of the tolling company. Participants of unincorporated joint ventures have contractual rights in the JVA, but also possess proprietary rights over the assets of the venture, which participants of tolling company arrangements do not possess.

Ownership of the inputs of the production process is similar to equity joint ventures, but not identical. In equity joint ventures, unless the equity participants sell the raw material to the SPV, the SPV will own the inputs of the production process at all stages of production before the finished product is eventually sold to equity participants or to third parties. The treatment of trading stock for participants of unincorporated joint ventures is different again. The tolling company acquires the raw material provided to it by one or more participants. All production is taken by the participants in specie (as with unincorporated joint ventures) and controlled by the participants who are committed to provide the raw materials at a given rate, without interruption and to take the product on a “take-or-pay” basis, under raw material purchase contracts.

A “take-or-pay” provision assumes that ownership of the work in progress and finished product lies with the tolling company until tolled to the participants. A take-or-pay clause in a purchase contract has been described as requiring the purchaser to take, or (failing to take) to pay for a minimum volume of finished product which the producer-seller has available for delivery.[21] For instance, suppose that three participants have incorporated a tolling company “T” to smelt alumina into aluminium and have each entered into a tolling agreement with T to construct smelting facilities. Each participant enters into a take-or-pay contract with T to purchase minimum quantities of aluminium, or, failing to take, to pay prescribed fees. T establishes a long-term financing facility. Proceeds of the loan are used to construct the smelting operation. The participants each meet their take-or-pay payment obligations so that T, in turn, can service its debt obligations to the financier.

Explanations of the economic rationales of long-term take-or-pay contracts contend that these agreements are a “rational response to specific industry characteristics”.[22] It is not entirely clear what that phrase is intended to convey, but presumably it refers to specific industry problems. One commentator suggests that this is primarily because the production, transportation and distribution of finished product involves the use of capital, which is useful only as long as the transaction that motivates its investment continues to take place.[23] Such capital is known as transaction-specific or relationship-specific capital.[24] Without sales, the tolling company obtains reward for its services by levying a tolling charge or fee sufficient to cover its tax-deductible costs.[25]

As tolling companies carry on business for ITAA97 purposes, costs incurred by the tolling company in purchasing raw materials are allowed as a deduction pursuant to s 8-1(1) of the ITAA97.[26] The participants are not entitled to allowable deductions incurred by the tolling company. The participants must first incur the tolling charge (discussed below). The acquisition is not on capital account.[27] Similarly, the SPV of an equity joint venture would ordinarily be entitled to deductions for the acquisition of the inputs into the production process.[28] By contrast, the participants of unincorporated joint ventures are entitled to claim their share of allowable deductions as separate taxpayers.

If a tolling company incurs an outgoing that is directly attributable to the buying or obtaining delivery of an item of trading stock, but the tolling company and participant do not deal with each other at arm’s length and the amount of the outgoing is greater than the market value of what the outgoing is for, the amount of the outgoing is instead taken to be that market value.[29] The words “market value” and “arm’s length” are not defined in the relevant provision of the ITAA97. However, the intent of the provision – as interpreted through its predecessor provision; namely, s 31C of the ITAA36 – is to overcome arrangements which “artificially” increase the price paid for trading stock of the kind considered by the High Court in Cecil Bros Pty Ltd v FC of T.[30]

The Review of Business Taxation (“Ralph Review”) has specifically recommended that tangible assets produced, manufactured or acquired and held for the purposes of manufacture, sale or exchange in the ordinary course of a business be included within trading stock.[31] This should not adversely affect tolling companies or participants. If the tolling charge includes an amount in respect of “intangibles”, then whilst these could be treated as trading stock under the current rules, they will be outside the definition of the proposed measure.[32]

The tolling company makes capital expenditure to provide a service for the joint venture through funds borrowed from afinancier. The shareholders in the tolling company are the participants who, through the use of that company, ensure that financing is, where possible, non-recourse.[33] Security is provided by the assets of the tolling company including the contracts with the participants. Fahey considers that because the assets of the tolling company are generally highly specific and specialised (and thereby have limited value to other parties), debt securitised over the assets is not disclosed in the participants’ balance sheets.[34]

It is argues that the principal fiscal benefit of using a tolling company structure is the transfer of the incidence of tax to the participants. Subsidiary benefits are: absence of characterisation risk[35] and generally lower compliance costs than for asset sales when participant’s interests are disposed of. But the compliance costs of reaping these fiscal benefits may not be insignificant, because costs will arise in determining the quantum of the tolling charge and in determining whether a tolling company is “carrying on a business”.[36]

The incidence of tax falls on the participants where tolling companies are concerned. In this respect, they are similar to participants of unincorporated joint ventures. “Incidence” describes a taxpayer on whom the burden to pay tax in respect of taxable income falls.[37] In each case, the incidence of tax falls on the participants for a different reason.

With unincorporated joint ventures, the unincorporated joint ventures has no separate legal personality, so therefore the incidence of tax must fall to the participants as individual taxpayers according to their undivided interests in the JVA and assets. Even if, on the proper construction, an unincorporated joint venture is to be characterised as a partnership for taxation purposes, then the incidence of tax similarly falls on the partners.[38] However, in this instance, the partnership would have to submit an income tax return each year of income, because it is a tax reporting entity.[39]

With tolling companies, a tolling company levies a tolling charge on the participants each year. The tolling charges approximately equal the sum of the tolling company’s tax-deductible expenditure for that year. Each participant pays these charges. In turn, a tolling company’s taxable income each year is approximately zero, because the income and the expenditures net-off. The participants each recognise a deduction for the tolling charges they have incurred.

Significantly, then, both legal structures lead to the same result as for incidence of tax, notwithstanding that the nature of the “interests” held by the participants of each structure is different.

With equity participants, the incidence of tax lies with the SPV. Equity participants are merely shareholders of a SPV.[40] An SPV derives all the assessable income of the joint venture by selling all the output from it. An SPV incurs losses and outgoings from the undertaking and is entitled to the deductions allowable therefrom under s 8-1 of the ITAA97. Accordingly, the incidence of tax in equity joint ventures falls on the SPV. Payment of an SPV’s retained earnings to the equity participants is by way of dividend. But in the tolling company context, it is as though each participant has its own production facilities to process that participant’s raw material for use or disposal within that participant’s production system.

Tolling companies are not subject to characterisation risk. Accordingly, tolling companies are not subject to the compliance costs a prospective participant would be likely to incur to make an assessment of the level of characterisation risk in a given case.

As the ownership interest of a participant in a tolling company is the same as for equity participants of equity joint ventures, in general a dealing by a participant in its shareholding in the tolling company will probably lead to similar compliance costs being incurred as for dealings by equity participants in their shareholding in an SPV.

In juxtaposition, it is probably also reasonable to assume that the compliance costs of a dealing by a participant in its shareholding in a tolling company will be lower than the compliance costs participants incur when they dispose of the assets of a joint venture. Factors supporting this assumption are several: absence of complex laws to apply compared to asset sales, no obligation to characterise the profit from the farmout or rely on the trading stock provisions of the tax law and the depreciation and mining and petroleum balancing adjustment provisions will be irrelevant.

Tolling companies also process raw material into finished product, control the use or disposal of the finished product, have the flexibility to reflect accounting, tax and other consequences in a manner appropriate to the business operations of each of the participants, allow each participant to manage its own tax affairs separately and, to the satisfaction of the Australian Taxation Office, allow flexible financing of the capital required for building and operating the production facilities to allow either global financing or individually arranged financing by each of the participants and flexibility to deal with expansions of the production facilities.[41]

A tolling company will incur costs to determine the tolling charge. A tax accounting model for determining tolling charges is set out below. It is argued that these costs are in addition to the costs a tolling company will incur to determine its taxable income (or loss) annually. The more significant the costs are, the more the fiscal benefit of using this joint venture structure are reduced. In theory, there will be a point where the compliance costs equal the benefits derived. If “break-even” point is reached, then from a revenue law perspective, there is no justification for using a tolling company structure in preference to other structures.

Tolling charges are unique to tolling companies. They could be determined either as a fixed amount to be reviewed from time to time or by taking into account specified component costs covering fixed and variable costs including interest and depreciation. Tolling companies are not expected to generate any taxable income.[42] Accordingly, a tolling company’s annual tolling charges approximate the total deductions of the tolling company allowable under tax laws in that year of income.

A tolling company will invoice the participants with tolling charges for payment by them. Invoices are limited to the amounts required by the tolling company to meet its cash outgoings. If a participant defers the payment of a tolling charge, it will be treated as a credit allowance in the tolling company’s accounts. In turn, the credit allowance may be called up at any time to meet its future cash requirements. Tolling charges are debited to a “credit allowance account” – a debtor account between the tolling company and the participants (discussed below). The other side to the credit allowance account is the cash calls.[43]

If the tolling charges exceed the amount of cash a tolling company receives, then the participants will owe money to the tolling company. Conversely, if the amount of cash received exceeds the value of the tolling charges, then the tolling company owes money to the participants. To ensure that the tolling company is never in a position of cash deficiency, the tolling agreement will contain provisions requiring the participants to make prepayments of tolling charges as necessary to meet the cash requirements of the tolling company.[44]

A tolling company will use a tax accounting model to determine the quantum of the tolling charge. Annual tax accounting is “one of the central pillars of the [Australian] taxation system”.[45] Even though it is well settled that in determining “taxable income” of a taxpayer, accountancy practice is relevant, the tests given statutory force in the

ITAA97 and ITAA36 in relation to either income or allowable deductions, will override accountancy practice.[46]

Nonetheless, there is support for a broad reliance on accountancy principles. Such reliance by Australian courts dates back to 1953. In the High Court decision of FC of T v James Flood Pty Ltd,[47] for example, Dixon CJ, Webb, Fullagar, Kitto and Taylor JJ said:

[c]ommercial and accounting practice may assist in ascertaining the true nature and incidence of the item as a step towards determining whether it answers the tests laid down by [s 8-1(1)][48] but it cannot be substituted for that test.[49]

In 1988, the Full Federal Court in Hooker Rex Pty Limited v FC of T[50] recognised the role of accounting principles and practices as a guide to the courts when determining the timing of deductions:

[i]t may readily be conceded that commercial and accountancy practice cannot be substituted for the test laid down by [s 8-1][51] ... Nevertheless, the tendency of judicial decision has been to place increasing reliance upon the concepts of business and the principles and practices of commercial accountancy, not only in the ascertainment of expenditure ...[52]

In 1999, the Ralph Review proposed the cash flow/tax value framework for calculating taxable income, to bring tax law into alignment with accounting principles. If this measure is introduced, then accounting principles should become even more relevant. That said, there will still be two separate calculations required. It will not be possible to use the same numbers for both tax and accounting purposes.

The process for calculating tolling charges is complex. A tolling company could expect to incur considerable labour time and effort in making such a calculation. The first step in the process is for a tolling company to review all its accounting costs to ascertain the costs which are allowable deductions under the tax laws. Added to this are other allowable deductions not included in the accounting costs. Adjustments may then be required in relation to items such as movements in provisions,[53] prepayments[54] and inventories.[55] These tax adjustments account for timing differences or permanent differences.[56]

Timing differences are differences between the accounting result and taxable income that arise because the period in which an item is included in the accounting result does not coincide with the year of income in which that same item is included in the taxable income. For instance, a provision in respect of bad debts may reduce accounting profit but there may be no allowable deduction to the

tolling company if a loss or outgoing is not “incurred” in the relevant sense. Timing differences “will result in the amount of income tax expense being either greater or less than the income tax payable for the [income year] in which the differences originate”.[57] For a tolling company, timing differences constitute the provision for future costs and credit allowances accounts (as identified above in this article). Tax timing differences comprise mainly the differences between accounting and tax depreciation, movements in provisions, prepayments and realised/unrealised foreign exchange gains and losses, but may also include operating costs and depreciation claimed outright by the tolling company when the tolling company is established.[58]

Permanent differences are differences between the accounting result and the “taxable income” that arises because, under the tax law, certain revenue items which are included in the accounting result will never be included in the “taxable income” and vice versa. Permanent differences therefore alter the incidence of income tax in relation to the pre-tax accounting result/profit or loss of the year of income in which they occur, but do not affect income tax calculations in respect of subsequent years of income,[59] such as the development allowance.[60] This is a special deduction equal to 10% of the amount of capital expenditure incurred on the construction/acquisition of eligible plant and equipment in certain large Australian projects which cost $50 million or more and meet certain other criteria.[61] Permanent differences may arise where the figures for purchases or sales of trading stock are varied rather than the valuation of stock-on-hand, for instance, where the Commissioner of Taxation (“Commissioner”) has applied s 70-20 to purchases (“non-arm’s length transactions”). Accordingly, the development allowance will never appear in the accounting result of the tolling company. For a tolling company, all permanent differences between accounting and tax values are reflected in the annual profit or loss.

Against this background, Example 1.1 advances a tax accounting model for the determination of tolling charges and specifically addresses how a tolling company’s taxable income is nil. The example has been greatly simplified in an attempt to further explain the tolling charge concept and how it is used to ensure that a tolling company does not make any taxable income.[62]

Example 1.1 Determination of Tolling Charge for Tolling Company

In its Business Activity Statement, a tolling company uses tax effect accounting to determine the tax deductible costs, using a Statement of Taxable Income calculation (see below). The total tax deductible costs become the tolling charge. The timing differences and the permanent differences are then identified. The timing differences are used to calculate the Provision for Future Costs. The permanent differences are used to calculate the profit. Therefore, all entries appear somewhere twice. This cost will not be in the accounting expenses but it will be in both the Provision for Future Costs and the tolling charge. Therefore, one cancels out the other. Another example is non-deductible costs. These costs will appear in the accounting expense and therefore accounting profit. Again, one cancels out the other. The figures are then “re-arranged” to give the Statement of Taxable Income.

Assume the only book entries for an income year are (in $):

Tolling revenue 70

Non-deductible costs 140

Tax depreciation 70

Book depreciation 20

Accounting expenses for the year are $160, provision for future costs in ($50), and the profit is ($140). Therefore the tolling company’s Profit and Loss Statement would be as follows:

Tolling Revenue 70 = Tax deductible costs

Less Expenses 160 = Accounting costs

Net profit before provision (90)

Provision for future costs (50)

Net Loss (140)

To calculate the above, tax deductible costs must be determined, then the provision for future costs must be determined, then profit must be calculated. The last step is to put each of the individual components together and the Profit and Loss Statement balances. It can be seen that the Profit and Loss Statement cannot be viewed as income less expenses equals profit. The Statement of Taxable Income would be as follows:

STATEMENT OF TAXABLE INCOME

Profit (140)

Add back:

Provision for future costs 50

Book depreciation 20

Non-deductible costs 140

Less:

Tax depreciation 70

Taxable Income 0

Compliance costs will arise in determining whether a tolling company is carrying on a business. Tolling companies operate on the basis that at the end of each income year, the taxable income of the tolling company is zero,[63] so therefore, at a practical level, they are “break-even” companies. Until now, the assumption in this article has been that tolling companies carry on business and therefore, may recognise deductions. Whether or not a tolling company is carrying on a business will depend on whether the definition of “business” in the ITAA97 is satisfied.[64] Neither the ITAA97 nor ITAA36 define or explain the expression “carrying on a business”.

To determine whether a tolling company’s activities amount to the carrying on of a business will be critically important in arriving at a decision, as to whether the particular receipts of the tolling company will be of an income nature and, flowing from this, whether outgoings incurred in the course of the activities of a tolling company will be allowable deductions.[65] Hill J in Evans v FC of T,[66] said that the question of whether a particular activity constitutes a business is often a difficult one involving as it does questions of fact and degree and that no one factor is decisive of whether a particular activity constitutes a business.

Since the determination will involve difficult questions of fact and degree, tolling companies must turn to Australian cases for guidance. The Court in Ferguson v FC of T,[67] said that the nature of the activities carried on by the relevant taxpayer:

particularly whether they have the purpose of profit-making, may be important. However, an immediate purpose of profit-making in a particular income year does not appear to be essential. Certainly it may be held a person is carrying on business notwithstanding his profit is small or even where he is making a loss. Repetition and regularity of the activities is also important ... Again, organisation of activities in a business-like manner, the keeping of books, records and the use of system may all serve to indicate that a business is being carried on ... The volume of his operations and the amount of capital employed by him may be significant.[68]

It is argued that a tolling company is likely to be engaged in a business notwithstanding it lacks profit motive. A profit motive is usually seen as no more than a factor in determining the existence of a business and an absence of a profit motive does not necessarily mean that a tolling company cannot be carrying on a business.[69] Several factors point strongly in favour of this conclusion: the scale of operations involved, the commerciality of those operations, the skill and judgments required to be made to process raw material into finished product and the fact that the tolling company is just another step in the production process of the participants who are themselves carrying on their own separate businesses. There would be considerable fiscal uncertainty if a tolling company that incurs tens of millions of dollars in expenditures each year of income is denied deductions for them by reason only that the tolling company lacks a profit motive.

Can a tolling company be said to be carrying on a business notwithstanding there is no reasonable prospect that it will make a profit, either in the immediate future, or at all? The position of the New Zealand courts has been that the concept of a “business” requires both an intention of making a profit and also a reasonable prospect of doing so.[70] Australian and United Kingdom courts have in the past taken a more liberal view, holding that a taxpayer may be carrying on a business notwithstanding there is no reasonable prospect of profits being made because “an immediate purpose of profit-making in a particular income year does not appear to be essential”.[71] The underlying policy of the Australian courts is not to suggest:

that it is the function of income tax Acts, or of those who administer them to dictate to taxpayers in what business they shall engage or how to run their business profitably or economically. The Act must operate on the results of a taxpayer’s activities as it finds them.[72]

It would seem, therefore, that in Australia, the mere fact that a tolling company makes only a small profit, say $1,000 in any particular income year, would be sufficient to rebut an argument that the tolling company cannot be carrying on a business on grounds that profit-motive is lacking. Whether a tolling company is carrying on a business in circumstances where it is impossible for the tolling company to ever make a reasonable profit is less clear.[73] Case M67[74] arguably stands for the proposition that notwithstanding a business undertaking can never succeed will not by itself automatically preclude a finding that the taxpayer is in business.

If the tolling company is carrying on business, then the tolling charges will constitute assessable income,[75] because they are revenue in nature. A tolling company’s assessable income[76] includes ordinary income “derived” directly or indirectly from worldwide sources during an income year.[77] The relevant statutory provision to determine whether a tolling company has derived an amount of ordinary income and (if so) when the income was derived, provides that a tolling company is taken to have received an amount as soon as it is applied or dealt with in any way on the tolling company’s behalf or as directed by it.[78] Useful guidance on the meaning of this provision can be obtained from judicial consideration of its predecessor provision.[79] The courts have traditionally considered income arising from the trading operations of a commercial undertaking as brought to account on an earnings or accrual basis.[80] Gibbs J in J Rowe & Son Pty Ltd v FC of T,[81] said that for taxation,

as well as for business, purposes income of a trading business is derived when it is earned and the receipt of what is earned is not necessary to bring the proceeds of sale into account.[82]

As a corollary, the amount of trading income derived is the amount that has become recoverable by the tolling company.[83] The Commissioner has in the past accepted the approach of the courts on this question.[84]

The participants will be each entitled to an allowable deduction for tolling charges “incurred” by each of them as a cost of production under s 8-1(1) of the ITAA97. “Incurred” means “incurred” as required by s 8-1(1). The meaning of the word “incurred” is best explained by considering some of the leading cases dealing with the interpretation of the predecessor provision of s 8-1(1). It is clear that the participants need not actually have paid the tolling charge by the end of a year of income to have “incurred” a loss or outgoing in the relevant sense. In W Nevill & Co Ltd v FC of T,[85] Latham CJ observed that the word used:

is “incurred” and not “made” or “paid”. The language lends colour to the suggestion that, if a liability to pay money as an outgoing comes into existence, [the section is satisfied] even though the liability has not been actuallly discharged at the relevant time ... it is only the incurring of the outgoing that must be actual; the section does not say in terms that there must be an actual outgoing – a payment out.[86]

In Commonwealth Aluminium Corporation Limited v FC of T (“Commonwealth Aluminium,[87] Newton J of the Supreme Court of Victoria made several important general points about the meaning of the word “incurred”, which are relevant for present purposes. First, a loss or outgoing may be “incurred” by participants notwithstanding that it remains unpaid, provided the participant has completely subjected itself to the liability.[88] Secondly, a participant can completely subject itself to a liability, notwithstanding that the quantum of the liability cannot be precisely ascertained, provided it is capable of reasonable estimation.[89] Thirdly, the quantum of a liability is capable of “reasonable estimation” for these purposes if it is capable of approximate calculation based on probabilities.[90] Fourthly, a participant may completely subject itself to a liability notwithstanding that the liability is defeasible.[91] These principles have been confirmed in two leading cases decided since Commonwealth Aluminium; namely, Nilsen Development Laboratories Pty Ltd & Ors v FC of T[92] and FC of T v Australian Guarantee Corporation Ltd.[93]

If tolling charges are calculated during an income year using a budgeted rate, there should be no question of the tolling company miscalculating the quantum of assessable income derived on its revenue account or the participants miscalculating their losses or outgoings incurred, provided that before the end of the year of income, the actual tolling charge for that year is calculated and an adjustment is made to the last tolling invoice of the income year for any difference between the actual charges for the year and the estimated charge used for invoicing purposes used as the basis for invoicing during the year.

If the proposed cash flow/tax value methodology becomes law, then tolling charges will probably continue to be assessable income for the tolling company and deductible for the participant. This will arise from the application of the rules for taxing receipts and payments. The caveat is that the special rules for determining what is an asset and liability, which will ultimately be legislated into the new rules in some form, could lead to some other classification for tolling charges. As yet, there is no information to indicate that tolling charges will be taxed any differently from any other trading receipts or payments.

Part IVA should not apply to tolling companies because there will be no leakage of tax or prospect of leakage from the structure. Example 1.1 demonstrates that the full incidence of tax is borne indirectly by each of the participants. Part IVA of the ITAA36 is a general anti-avoidance provision. It is expressed to apply to schemes or parts of schemes that have the purpose of producing specified tax benefits.

In order for Pt IVA to operate, there must be a “scheme”,[94] the scheme must produce a “tax benefit”[95] and the scheme must be entered into for the sole or dominant purpose of gaining the benefit.[96] Once these elements are satisfied, the Commissioner is empowered to reconstruct the transaction so as to modify or cancel the tax benefit.[97]

There will ordinarily be no contravention of Pt IVA from the use of a tolling company, because a number of commercial reasons explain why participants enter into such structures. For instance, companies wishing to establish common production facilities might prefer to undertake this through a tolling company compared with using the conventional company structure. The motivation for pooling resources in a tolling company could be to obtain the processed product for each participant’s own use rather than for commercial sales to third parties. This can be achieved pursuant to take-or-pay purchase contracts. The participants seek to retain the maximum flexibility they can over treating their rights, interests and obligations in the joint venture as separate rather than as joint and several subject to the constraints of the Corporations Law. The other perceived main advantages of tolling arrangements include the absence of characterisation risk and of the fiscal uncertainties associated with unincorporated joint ventures whilst retaining tax flow-through capabilities. The tolling structure is a well-suited vehicle to facilitate the management of each participant’s own tax affairs, to provide flexibility in construction and operational financing of the production facilities and in dealing with expansions of the production facilities.

Financing a tolling company arrangement will be likely to give rise to two types of compliance costs for a participant. The first type of cost relates to the compliance costs of entering into long-term supply contracts. The second is caused by the legal and effective complexity of complying with s 51AD of the ITAA36.

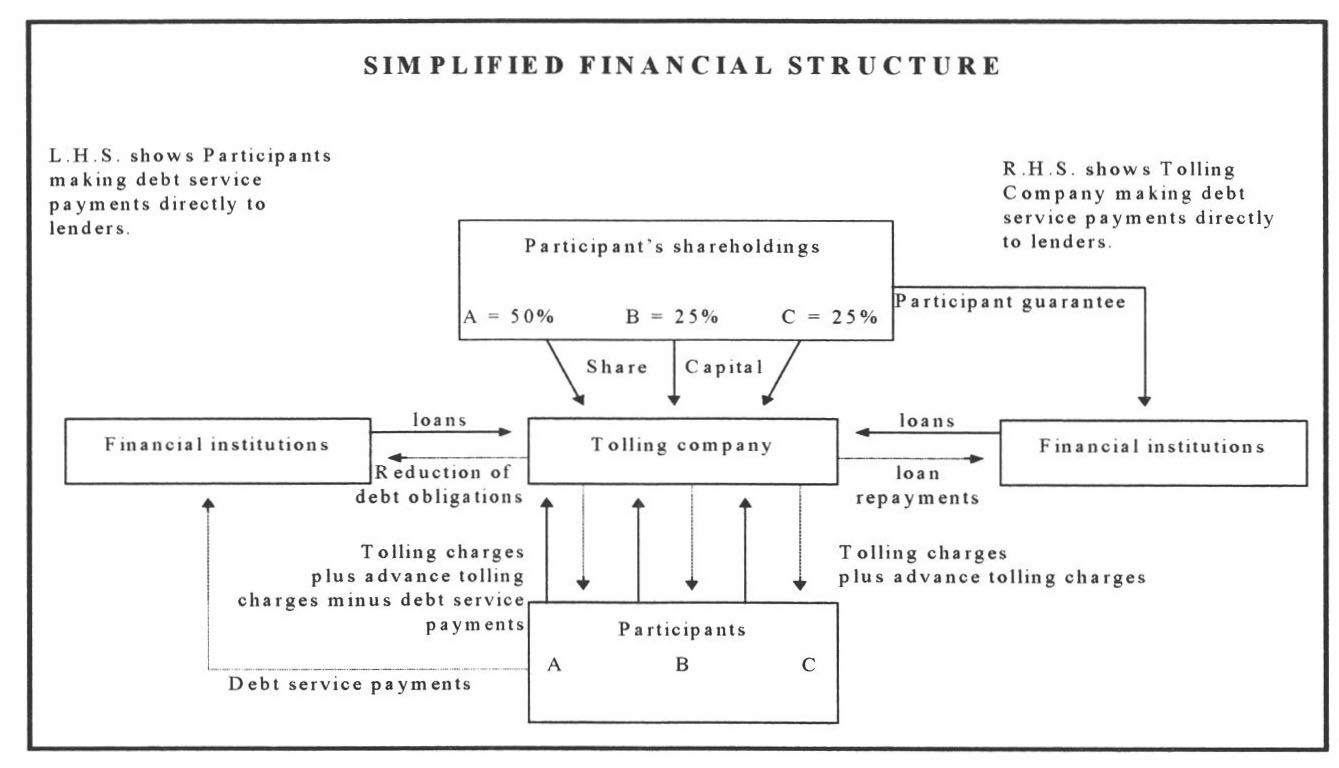

If the construction of the processing facilities of a tolling company depends materially on construction finance, then the structure of a tolling company arrangement must meet financiers’ requirements. Any number of methods and structures could be used for this financing, most of which can be or have been adapted for use by a tolling company. Traditionally, participants have organised the funding on the basis of a nominal amount by way of share capital with almost all of the funds provided by way of loans. In fact, it is not unusual for participants to take on a non-recourse financing arrangement to facilitate the construction of expensive facilities.[98] Because of this, tolling arrangements are unlikely to take place without a guarantee of a continuing relationship with the participants in the production chain. Long-term purchase contracts can provide this guarantee.[99] A simplified financing tolling structure is set out in Figure 1.2.

A financier is generally restricted to the assets to be constructed for its security. This will generally be inadequate security for the borrowings. As pointed out by one commentator,

because the assets are transaction-specific, although some of their value may be realised if sold, the specific nature of these assets means that their full value can only be recouped through participation in the transactions that originally motivated the investment.[100]

It is therefore essential that a tolling company enters into take-or-pay long term purchase agreements that contain guaranteed purchase prices and income levels, regardless of output to ensure a sufficient income stream to service and repay the debt. In many circumstances, the end users will be the participants or their associates. Such an agreement ensures the protection of the tolling company and financier from cash-flow fluctuations caused by a reduction in supply of materials or lack of demand for the end product. In short, a “guaranteed” income stream provides the necessary security to the financier and converts an otherwise unattractive financing arrangement into one that is as secure as the financial standing of the end users.[101]

Figure 1.2: Simplified Tolling Company Financing Structure[102]

Nevertheless, there are significant transaction costs associated with these long-term contracts: they have high enforcement and monitoring costs.[103] While it is relatively inexpensive and straightforward to obtain information about market conditions in the immediate future, uncertainty as to conditions in the more distant future mean that relevant information is often unavailable. As uncertainty surrounding future conditions increases, so too do the transaction costs of long-term contracts, as the likelihood of contractual breakdown increases.[104]

But it could be argued that because the high monitoring and enforcement costs of long term purchase contracts are not “costs to the economy that arise as a result of taxpayers complying with taxation,”[105] they are not “compliance costs” for the purposes of this article. This argument is predicated on the basis that as the costs are avoidable costs, they must fall outside the definition of compliance costs. The author recognises the issue about whether tax-planning costs should fall within the definition of compliance costs. The author considers that avoidable compliance costs of taxpayers are included in the definition of compliance costs.

Section 51AD denies all deductions relating to property largely financed by non-recourse loans which are “leased to or effectively controlled by” a tax-exempt entity. It is especially relevant in the context of tolling companies. In policy terms, s 51AD of the ITAA36 is relatively straightforward – it is an anti-avoidance, or punitive,[106] measure directed at curtailing tax leakage, by dealing with tax benefit transfer arrangements.[107] The Ralph Review has recommended the abolition of this provision.[108] The government supports this recommendation in principle, although no legislation has been passed yet.[109]

Section 51AD will apply to property acquired by a tolling company under a contract entered into on or after 24 June 1982,[110] or constructed by a tolling company where construction commenced after that time. Section 51AD will not apply unless the cost of the acquisition or construction of the property by the tolling company is wholly or predominantly financed by non-recourse debt.[111] In context, non-recourse debt means that the rights of the financier in the event of default by the tolling company are predominantly limited to rights against the property itself, or against the income, goods or services generated by the property, or to rights in respect of a security over the property.[112] A debt is also non-recourse if the financier would not have access to all the unsecured assets of the tolling company in a recovery action.[113]

Where the conditions relating to time of acquisition and non-recourse debt are satisfied, s 51AD will apply to property in either of two sets of circumstances. The first is where the property is leased and the lessee (or sub-lessee) is not a resident of Australia and the property is, or is to be, used wholly or principally outside Australia, the property is, or is to be, used otherwise than solely for producing assessable income or the property was owned and used, or held for use, by the lessee or sub-lessee before the end-user acquired it.[114]

The second circumstance in which s 51AD can apply to a tolling company concerns property that is owned by a tolling company but the use of which in the production, supply, carriage, transmission or delivery of goods or the provision of services is controlled by an end-user.[115] The end-user must be either a non-resident of Australia and the property is, or is to be, used wholly or principally outside Australia and uses the goods or services produced by means of the property otherwise than solely for the purpose of producing assessable income, derives no income, or derives income that is wholly or partially exempt, in providing those goods or services or owned and used the property, or held it for use, before the tolling company acquired it.[116] The critical question of who “controls” the use of a power station will ultimately depend on the facts of each particular case.

If the provision is triggered, the tolling company is treated as not using the relevant property for the purpose of producing assessable income or in carrying on a business for that purpose;[117] and it is denied deductions attributable to the ownership of the property, including depreciation, repairs, interest on borrowings and other expenses. If this happens, it would reduce the quantum of the tolling charge. In turn, a reduction in the tolling charge would reduce the net present value of a project to the participants. The reduction in the net present value of a project to a participant would equal the dollar amount of the allowable deduction that that participant foregoes.[118]

If the provision operates, the tolling company is treated as not using the relevant property for the purpose of producing assessable income or in carrying on a business for that purpose;[119] it is denied deductions attributable to the ownership of the property, including depreciation, repairs, interest on borrowings and other expenses. If this happens, it would reduce the quantum of the tolling charge. In turn, a reduction in the tolling charge would reduce the net present value of a project to the participants. The size of the reduction in the net present value of a project would equal the dollar amount of the allowable deduction that a participant foregoes.

The Ralph Review’s recommendation to abolish s 51AD is based on the provision’s “severe impact where it applies because all deductions are denied to the taxpayer but the associated income is still assessable. It has continually been criticised by State governments and infrastructure providers for its severe impact where it applies and the uncertainty it creates”.[120] Moreover, the Ralph Review indicated that:

[s]ection 51AD has become even more problematical in recent years because of increased levels of privatisation and outsourcing of government services which were not contemplated when it was first conceived.[121]

It has also been argued that:

[t]he severe treatment of arrangements that are currently prohibited by section 51AD is unnecessary – and there is no reason why leases (and similar arrangements) involving tax exempts should be treated differently simply because they are financed using non-recourse finance – providing structural measures are in place to address potential structured non-payment of non-recourse finance, tax preference transfer to tax exempts and the timing advantages of delayed lease and service contract rentals ... The Review believes that section 51AD can no longer be justified.[122]

If the Ralph Review’s proposal is introduced, then it will have the capacity to reduce the burden of compliance costs imposed by the provision on taxpayers whilst it remains in force.

In practical terms, s 51AD issues may arise because of tolling companies traditional dependence on contractual arrangements with suppliers of energy (eg electricity and gas) for processing operations, who in the past in Australia have been government entities.[123]

While the effect of s 51AD may be a simple concept, the provision is legally and effectively complex in its operation and this may potentially increase the compliance cost burden on a tolling company. This complexity will be illustrated by the following example. Assume that Australian resident Participants A, B and C, through their wholly-owned Australian resident tolling company, T, own a power station in Victoria, Australia financed by non-recourse debt.[124] The Participants supply coal to T, who in turn converts the coal into electricity, for use in an aluminium smelter owned severally by A, B and C as participants of an unincorporated joint venture. T also sells a small portion of electricity produced into the Australian national electricity market (“the NEM”).

The tolling company, T, must first assess whether the conditions in the provision relating to time of acquisition and non-recourse debt are satisfied. Section 51AD will apply to property acquired by a tolling company under a contract entered into on or after 24 June 1982,[125] or constructed by a tolling company where construction commenced after that time. Section 51AD will not apply unless the cost of the acquisition or construction of the property by the tolling company is wholly or predominantly financed by non-recourse debt.[126] Non-recourse debt is debt in respect of which the rights of the financier in the event of default by the tolling company are predominantly limited to rights against the property itself, or against the income, goods or services generated by the property, or to rights in respect of a security over the property.[127] A debt is also non-recourse if the financier would not have access to all the unsecured assets of the tolling company in a recovery action.[128]

If the conditions relating to time of acquisition and non-recourse debt are satisfied, a tolling company must determine whether one of two sets of circumstances are present. The first is where the property is leased and the lessee (or sub-lessee) is not an Australian resident and the property is, or is to be, used wholly or principally outside Australia, the property is, or is to be, used otherwise than solely for producing assessable income or the property was owned and used, or held for use, by the lessee or sub-lessee before the end-user acquired it.[129]

The second circumstance in which s 51AD can apply to T concerns property that is owned by a tolling company but the use of which (in the production, supply, carriage, transmission or delivery of goods or the provision of services) is controlled by an end-user.[130] The end-user must be either a non-resident of Australia and the property is, or is to be, used wholly or principally outside Australia, or uses the goods or services produced by means of the property otherwise than solely for the purpose of producing assessable income, derives no income, or derives income that is wholly or partially exempt, in providing those goods or services or owned and used the property, or held it for use, before T acquired it.[131]

A determination of the question of control is the principal cause of the legal and effective complexity of the provision. A determination of the end-user will be readily apparent from the facts of a case.[132] For convenience of discussion, it is assumed that the tax-exempt end-user in the above example is the National Electricity Market Management Company Limited (“NEMMCO”).[133] NEMMCO is established to conduct the NEM efficiently in accordance with National Electricity Code (“NEC”) on a self-funding/break-even basis.[134]

The concept of control is central to the operation of s 51AD. In the section, “control” is defined to mean “effectively control”.[135] But the provision neither defines “effectively control” nor sets out criteria to be used by taxpayers to determine whether the definition is satisfied. This does not appear to be a drafting issue peculiar to s 51AD, because two other provisions of the ITAA36 define “control” in the same fashion.[136] The expression “effectively control” is not defined in the ITAA97 or ITAA36. Therefore, a tolling company must interpret the expression based on its ordinary meaning.

A determination of the ordinary meaning of the provision will not always be an easy task. The Explanatory Memorandum accompanying the Bill introducing s 51AD states that to control effectively “means to control in a practical sense whether or not, in a more formal sense, there would be control”.[137] “Control” has been defined as meaning “to exercise restraint or direction over; dominate; command ... the act or power of controlling; regulation; domination or command”,[138] whilst “effectively” is an adverb describing the ability to serve to effect the purpose.[139]

Those definitions suggest that “effectively” means that which actually causes something to happen and “control” is the power to decide what is to be done, how it will be done, when it will be done and where. The meaning of “effectively control” may be usefully interpreted by reference to the central management and control test used to determine the residency status of corporations. Section 6(1) of the ITAA36 defines resident as including “a company which is incorporated in Australia, or which, not being incorporated in Australia, carries on business in Australia, or has either its central management and control in Australia or its voting power controlled by shareholders who are residents of Australia”.

It could be argued that in the context of s 6(1), “control means de facto control evidenced by overt acts and not merely the potential to control”.[140] Judicial authority supports this view. For example, in Esquire Nominees v FC of T (“Esquire Nominees),[141] the taxpayer was incorporated in Norfolk Island. Its directors were all Norfolk residents and directors’ meetings were held in Norfolk Island. An Australian chartered accounting firm prepared the agendas acting on behalf of Australian residents who were the beneficial owners of the

taxpayer. The Commissioner argued that the directors merely carried out the instructions given by the accountants and therefore, real control of the company was in Australia. Gibbs J rejected this argument saying that although the company (via its directors) did what it was instructed to do, the accounting firm had power to exert influence and perhaps strong influence but that was all. Gibbs J said that he believed that if the directors had been instructed to do something improper or inadvisable they would not have done it and therefore actual management and control of the company and therefore its residence, was in Norfolk Island. The High Court upheld this point on appeal.

In Unit Construction Co Ltd v Bullock (“Unit Construction),[142] management and control of subsidiaries was vested in directors who could meet anywhere outside the United Kingdom. The subsidiaries’ directors acquiesced in decisions being taken in the United Kingdom by the parent company. The Court held that the subsidiaries were United Kingdom residents. The House of Lords stated that the actual place of management was the decisive question and the instant case was a straightforward question of de facto control in the United Kingdom.

Arguably the distinction between Esquire Nominees and Unit Construction turns on the action of the directors in Unit Construction standing aside while decisions were taken in the United Kingdom.

It was found in Malayan Shipping Co Ltd v FC of T[143] (and conceded by the appellant) where two Singaporean persons who were appointed directors and who met outside Australia, that all decisions were taken by an Australian resident (with power to appoint and remove directors, veto resolutions, control company contracts and bank accounts, etc) so that the entire management and control of the company was concentrated in his hands. The company was treated as a resident of Australia.

The case of FC of T v Commonwealth Aluminium Corporation Ltd[144] may indicate some softening of approach on the degree of de facto control necessary to be shown. The case concerned the Commissioner’s arbitrary assessment power under the former s 136 of the ITAA36. The majority of the High Court of Australia considered that the critical issue was who controlled the business as distinct from who controlled general meetings. While holding that the taxpayer’s directors in Australia controlled the business, Stephen, Mason and Wilson JJ said that the word “controlled”:

refers to de facto control rather than to capacity to control ... What is more, the notion of de facto control is appropriate when we consider that it is to the business carried on by a company, not to the company itself, that the word relates ...

The shareholders, through their power to control the company in general meeting and perhaps through their power to elect directors, may be said to “control” the company, but as a general rule they do not exercise de facto control of the company’s business.[145]

Therefore, more is required than simply looking at the strict legal rights attaching to the agreements or arrangements that may be entered into by a tolling company in relation to the management and control of a power station. Additional matters may come under scrutiny as well: to the extent that s 51AD(4)(b)(ii) uses the words “controls, will control, or is or will be able to control directly or indirectly” in relation to the use of T’s property, it looks to de facto rather than legal control.

Accordingly, a determination of the question of control will require resources to be expended to examine power station management documents and associated arrangements (eg financial relationships), which could affect the question who effectively controls the operation of the power station. Any financial arrangements between T and others (generally, though, NEMMCO) may indicate economic dependency such that T, as the legal owner, may not as a practical matter, be capable of operating the power station otherwise than in accordance with the wishes or directions of those other persons or bodies.

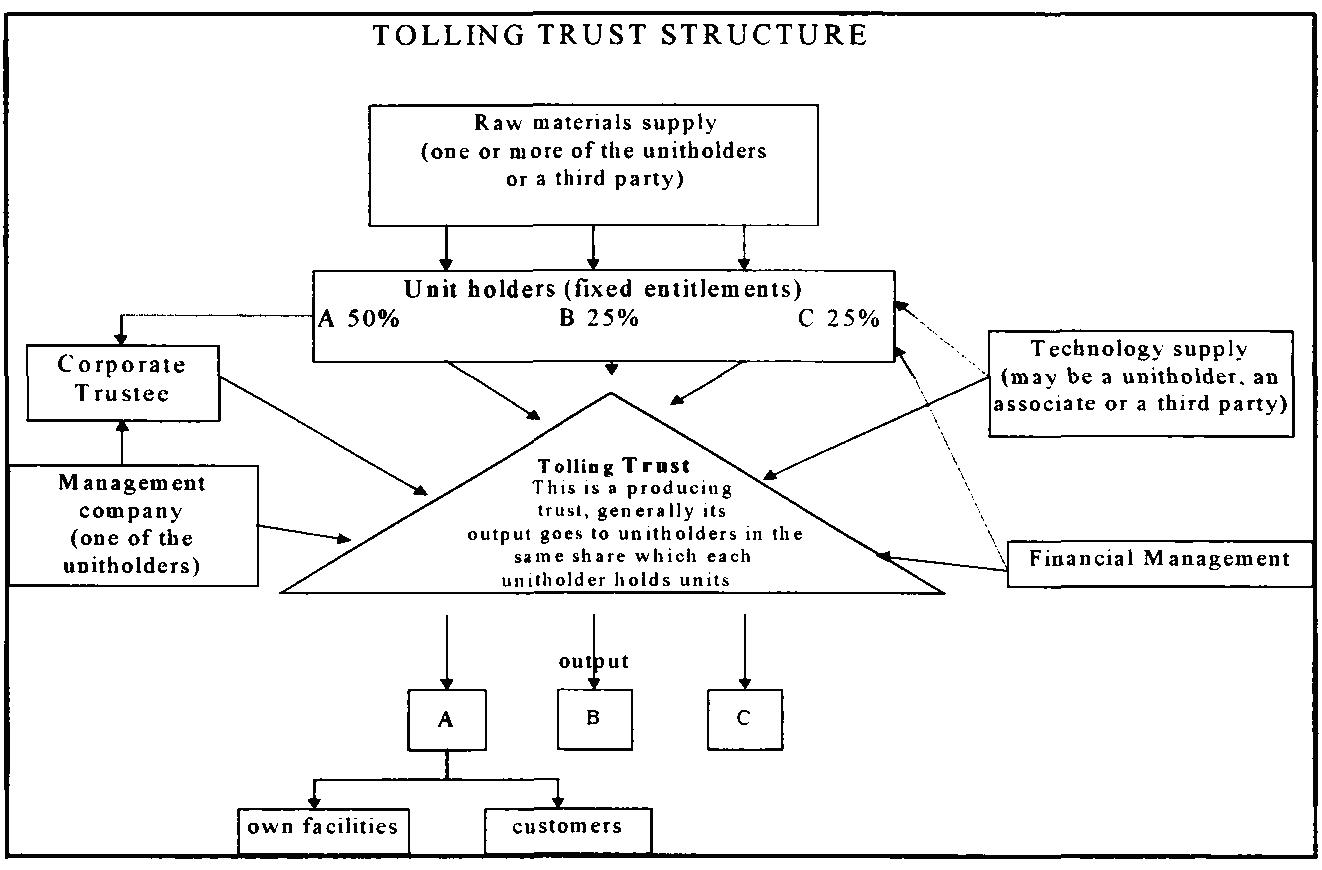

A unit “tolling” trust might be an attractive option for participants,[146] and this is principally because of their flow through capabilities. Trusts allow arm’s length participants to join together in an undertaking, with defined rights to a proportion of the income and capital of the trust fund and specified entitlements as against the trustee, without the requirement that the participants become co-shareholders in a tolling company.

Presently, the net income of the trust is not subject to the prevailing company income tax rate.[147] Flow-through tax advantages are the main reason for the widespread use of trusts and specifically the flow through of tax preferences.[148] Trusts are not now taxed at the entity level, “trust law treats them as conduits to liabilities of beneficiaries and trustees”.[149] The trust is a conduit to presently entitled beneficiaries.[150] Figure 1.3 illustrates the inter-relationships that occur in a tolling trust structure and usefully demonstrates the obligations of the unit holders to the tolling trust and to the financiers.

Figure 1.3: Simplified Tolling Trust Structure

The concept of the tolling charge will not be contrary to the trust loss provisions inserted in Sch 2F of the ITAA36 pursuant to the Taxation Laws Amendment (Trust Loss and Other Deductions) Act 1998 (Cth). Tax losses cannot be distributed under the law of trusts and are locked into the trust structure.[151] In the tolling trust concept, current year deductions are transferred from the trust to the participants. The participants will probably not be tax-avoiders.

In 2000, the Government released exposure draft legislation providing for the taxation of trusts like companies.[152] The exposure draft legislation provided that all resident non-fixed trusts would be taxed like companies unless they were specifically excluded. The proposed general rule was that unless the trust was a fixed trust, only non-fixed trusts created or settled as a legal requirement would be excluded. The exposure draft legislation provided for the intended preservation of conduit taxation for fixed trusts on the introduction of the entity taxation regime. That is, conduit tax treatment for fixed tolling trusts would have continued under the entity taxation regime.[153] The Government announced the withdrawal of the exposure draft legislation in 2001.[154]

In Canada and the United States, royalty trusts achieve a similar fiscal outcome for the investors as for tolling companies in Australia. But unlike tolling companies, the benefit of conduit taxation of royalty trusts is that the tax preferences associated with the ownership of assets like real property are passed through to ultimate investors with their tax status’s intact.[155]

Canadian royalty trusts are a useful conduit entity for taxpayers with significant investments in mining and petroleum assets, such as mature oil and natural gas properties, producing oil facilities, pipelines and gas processing facilities.[156] Despite the complexities of royalty trusts and the restrictions in the Canadian Income Tax Act (“ITA”)[157] on unit trusts and mutual fund trusts, they can be utilised as a flexible vehicle to achieve desirable economic results. In general, a trust is taxed in Canada as an individual on its income for each tax year without benefit of personal deductions.[158]

Royalty trusts must satisfy the definitions under the ITA of a “unit trust”[159] and a “mutual fund trust”.[160] In effect, this means that four broad requirements must be satisfied. First, the trust may acquire and hold virtually any type of asset, provided that the holding is essentially passive.[161] Secondly, a mutual fund trust must have units which are qualified for distribution to the public under applicable securities law and must have reasonable dispersal of ownership (ie at least 150 unit holders).[162] Thirdly, if a mutual fund trust is to invest more than 10% of its funds in securities of one issuer (other than the Crown), units must have a defined and reasonable redemption feature. Conversely, if the trust restricts its investments to certain types of property, including royalties on petroleum, natural gas or mineral production, it will qualify without a redemption feature.[163] Fourthly, the trust must maintain restrictions on ownership by non-residents to ensure that less than half of its units are owned thereby.[164]

A classic royalty trust is a mutual fund trust which acquires an interest in the proceeds of petroleum production from a special purpose corporation. The classic royalty trust structure creates a resource-based passive revenue stream, giving the trust all of the benefits (and risks) of carrying on an oil and gas business.[165] This is achieved by carving out a percentage of the “net revenue” generated from the output of a petroleum and natural gas working interest (whether production leasehold interests or freehold title to mines or minerals) as a “royalty”. The method whereby the royalty trust, as a mutual fund trust is able to capture the taxation benefits of carrying on an active oil and gas business is complex and is a function of the structure used.[166]

The basic structure involves the establishment of an operating company – OpCo – the entity which will carry on the oil and gas business. This will be relatively inexpensive to establish. OpCo will essentially be a flow-through vehicle to the royalty trust. Ownership of shares in OpCo is not economically significant. In order to separate the business being carried on and the passive investment required of the royalty trust, the OpCo’s shares are typically owned by the manager of the business, M, which earns a management fee for its management efforts.[167]

OpCo then purchases the petroleum and natural gas working interests from the relevant vendor. The royalty trust finances the acquisition of the production leasehold interests by OpCo from issuing shares to the public. The capital generated by the share issue provides the funds to acquire the interests.

From an economic perspective, the royalty is intended to vest in the royalty trust the net profit from the petroleum and natural gas production business carried on by OpCo. For Canadian taxation purposes, the royalty is intended to create a deduction in OpCo of its net income, being its gross revenue less any available deductions that it may have.[168]

This result could be contrasted with the income tax consequences of a distribution by OpCo of its profits to shareholders, which would not be deductible to OpCo (because it is a dividend payment), thereby imposing an intervening level of taxation between the source of the income and the ultimate recipient. Therefore, the royalty granted by OpCo to the royalty trust will achieve a flow-through of OpCo’s income to the trust, itself a flow-through vehicle for unit-holders, thereby achieving the same result as in the tolling trust. Basically, “royalty” income consists of the excess of gross revenue from production, including the share reserved to the Crown less the aggregate of costs.[169]

If OpCo is left without resources to remit the Crown’s share of production from the working interest, the royalty trust will agree to reimburse OpCo for its Crown royalty obligations. The royalty trust could do this by agreeing to allow OpCo to offset the amount owed under the reimbursement obligation against OpCo’s liability to pay the royalty.

The reimbursement mechanism operates under s 80 of the ITA to shift the burden of non-deductibility and the partial offset created under the resource allowance to the royalty trust, where the excess of the non-deductible Crown royalties over resource allowance can be allocated to unit-holders under s 104(29) of the ITA. Therefore, OpCo acts as a flow-through vehicle, with all of the taxable profit from its operations being distributed to the royalty trust. The royalty trust, as the income recipient, is also the repository of the cost for tax purposes of the bulk of the business expenditures, being the purchase price of the working interest.

The classic royalty trust creates a vehicle whereby an investor receives revenue without an intervening level of taxation (by virtue of the flow-through nature of both OpCo and the royalty trust).

Oil and gas royalty trusts, found in the US oil producing states, are tax-driven entities.[170] In a typical transaction, a company that has developed an oil field (or some other extractive asset) will transfer ownership to a trust, distributing beneficial interests in the trust to the company’s shareholders. As owner of the royalty-bearing asset, the trust distributes directly to the beneficiaries of the trust the royalty income that the trust asset generates. The beneficiaries then escape corporate-level taxation.[171] These trust interests are marketable and a number of the larger royalty trusts are stock-exchange traded.[172] A royalty trust may pass production profits tax-free to shareholders. Income from oil and gas royalty interests is not treated as rent from real property for the purposes of qualifying as a real estate investment trust,[173] nor would such income be of the type necessary to qualify as a regulated investment company.[174]

Oil and gas royalty trusts are utilised in two different types of mineral royalty transactions. The first type consists of a distribution in kind of income producing property to the shareholders. If this happens, no corporate income taxes are imposed on future royalty income. To illustrate, a company, by utilising royalty interests[175] on all or a portion of its mineral properties, transfers the royalties to a trust. It is intended that the trust will constitute a royalty trust rather than a separate taxable entity and that the shareholders will be treated as the owners of the trust property.[176]

If the income stream is no longer subject to federal income taxes at the corporate level, the shareholders would be taxed directly on the royalty income paid to the trust. If the shareholders are treated as owning the underlying property of the trust, they would be entitled to depletion deductions on the income.[177]

The second type of royalty trust transaction provides corporations with a method for raising capital without issuing additional debt or equity by applying the royalty trust concept to a traditional financing vehicle in the oil and gas industry.[178] These trusts often involve an initial public offering. At the closing of the offering, the trust purchases royalties on a designated portion of the corporation’s mineral properties.[179] The corporation generally recognises a taxable gain on the sale and the investors, as owners of the trust property, are taxed directly on the royalty income and are entitled to the same tax benefits available in a shareholder distribution transaction – depletion deductions.[180]

This article has critically examined the income tax characteristics (including compliance costs features) of tolling companies and has compared them to those of unincorporated joint ventures and equity joint ventures. In conclusion, whilst tolling companies facilitate fiscal benefits for participants by transferring the incidence of income tax in respect of a business activity to them, those fiscal benefits come at the cost of compliance costs. Compliance costs will erode the fiscal benefits derived. Tolling companies will stop being a favourable tax vehicle when the fiscal benefits associated with their fiscal transparency are less than or equal to the compliance costs from adopting the structure.

[∗]This article is Part II in a two-part series examining discrete aspects of the taxation of joint ventures. Part I was published in [2002] JlATax 3; (2002) 5 Journal of Australian Taxation 60 and concerned the taxation of farmins and farmouts.

[**] Dr and Senior Lecturer, faculty of Law, Monash University. The author gratefully acknowledges the enduring support of Associate Professor Dr John Glover.

[1] In this article, the term equity joint venture is used rather than incorporated joint venture. Unless otherwise stated, it is assumed in this article that participants are Australian resident corporations.

[2] J Fabey, “Tax Effective Joint Venture Financing” in The Rights & Duties of Joint Venturers (1990) 48.

[3] JL Armstrong, “The Organisation of Mineral Processing Joint Ventures –Tolling Companies and Other Corporate Vehicles” (1982) 4 AMPLJ 399, 400.

[4] Queensland Alumina Ltd (“QAL”) is a tolling company which operates the world’s largest alumina refinery on behalf of its participants (Queensland Alumina Ltd– Comalco Ltd, Kaiser Alumina Australia Corporation, Aluminium Pechiney Australia Pty Ltd and Alcan Queensland Pty Ltd): see Armstrong, above n 3, 400.

[5] Boyne Smelters Ltd - Comalco Aluminium Ltd, Kaiser Alumina Australia Corporation, SLM Australia Pty Ltd, Kobe Aluminium (Australia) Pty Ltd and Sumitomo Aluminium Smelting (Australia) Pty Ltd: see Armstrong, above n 3, 400.

[6] Company Prospectus on CD-Rom V.2.01, Lihir Gold Ltd, (1995), s 5 (“Selected Financial Data”).

[7] Ibid Novas Petroleum, 1995, s 1 (“The Company” and “The Business”); Tap Oil NL, 1996 (“Summary of The Offer”).

[8] Ibid Asian Energy Ltd, (1995) (Withdrawn), s 5 (“Investment Overview”). Tolling companies could conceivably be used in timber processing operations: “Timber Joint Venture May Provide Resolution to RFA Row”, ABC News, 6 July 1999, abc.net.au/news/regionals/sunshine/regsun-6jul 1999-5.html.

[9] Reproduced from Armstrong, above n 3, Appendix 1.

[10] For example, an expansion agreement, a management agreement, technology agreement and financing or loan agreements required in organising and providing the construction and working capital finance for the project.

[11] WM Blanshard, “Comment on the Organisation of Mineral Processing Joint Ventures – Tolling Companies and Other Corporate Vechicles” (1982) 4 AMPLJ 419, 420.

[12] Armstrong, above n 3, 402.

[13] Although participants which are corporations would have a memorandum and articles of association, too.

[14] Armstrong, above n 3, 403; and Blandshard, above n 11, 421.

[15] For unincorporated joint ventures, see JD Merralls, “Mining and Petroleum Joint Ventures in Australia: Some Basic Legal Concepts” (1988) 62 Australian Law Journal 907, 912; for equity joint ventures, see G Stedman and J Jones, Shareholders’ Agreements (1986) 168.

[16] Armstrong, above n 3, 404; cf Blanshard, above n 11, 421.

[17] ITAA97, s 42-15(a). See also Blanshard, above n 11, 421.

[18] Armstrong, above n 3, 404.

[19] “Trading Stock” is defined inclusively in ITAA97, s 70-10: see Blanshard, above n 11.

[20] Armstrong, above n 3, 406.

[21] PH Martin and BM Kramer, Williams & Meyers Manual of Oil and Gas Terms (10th ed, 1997) 1070; and R Sullivan, Financing Transnational Projects (1988) 7-13[1]. This definition was discussed in Williamson v Elf Aquitaine 925 F Supp 1163 (ND Miss 1996); and Thomas Well Service Inc v Williams Natural Gas 873 F Supp 474, 477. See also R Ricker, “Commentary on the Organisation of Mineral Processing Joint Ventures – Tolling Companies and Other Corporate Vehicles” (1982) 4 AMPLJ 427, 429.

[22] See generally JH Mulherin, “Complexity in Long-term Contracts: An Analysis of Natural Gas Contractual Provisions” (1986) 2 Journal of Law, Economics and Organisation 105; RG Hubbard and RJ Weiner, “Natural Gas Contracting in Practice: Evidence from the United States” in R Golombek et al (eds), Natural Gas Markets and Contracts (1987); and ME Canes and DA Norman, “Long-Term Contracts and Market Forces in the Natural Gas Market” (1985) 10 Journal of Energy and Development 73.

[23] Industry Commission, Study into the Australian Gas Industry (1995) 239.

[24] Ibid.

[25] MC Ahrens, “Incorporated Joint Ventures” in RP Austin and R Vann (eds), The Law of Public Company Finance (1986) 461-462. See also Armstrong, above n 3.

[26] Cf Blanshard, above n 11, 421.

[27] ITAA97, s 70-25 provides that an outgoing incurred in connection with acquiring an item of trading stock is not an outgoing of capital or of a capital nature.

[28] ITAA97, s 8-1(1).

[29] ITAA97, s 70-20.

[30][1964] HCA 82; (1964) 111 CLR 430.

[31] Review of Business Taxation, A Tax System Redesigned (1999) 180 (“A Tax System Redesigned”).

[32] Ibid.

[33] As to the meaning of non-recourse, see the discussion on ITAA36, s 51AD below.

[34] Fahey, above n 2, 48.

[35] Characterisation risk is an expression coined by the author to describe the risk of a finding that the relationship between participants of a joint venture is one of partnership.

[36] It shall be seen that this uncertainty is probably more theoretical than real given the size of business operations involved. Tolling companies are not flow-through entities. They are fiscally transparent and because of that, they share many of the taxation advantages associated with unincorporated joint ventures. These advantages must be weighed against the complexity inherent in the number of agreements required to establish a tolling company structure.

[37] ITAA97, s 4-10; DJ Jüttner, International Finance & Global Investments (3rd ed, 1995) 484. There are two theories dealing with the incidence of tax. See AC Harberger. “The Incidence of the Corporate Income Tax” [1962] Journal of Political Economy 215; and GC Hufbauer, US Taxation of International Income (1992).