Journal of Australian Taxation

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Journal of Australian Taxation |

|

TAX REFORM: AN INTERNATIONAL COMPARISON OF THE EFFECTIVENESS OF CHANGES TO AUSTRALIA’S CAPITAL GAINS TAX

By Kim Wyatt,[*] Jon Phillips[∗∗] and Paul de Lange[∗∗∗]

The Review of Business Taxation was established in 1998 in Australia to make recommendations on the fundamental design of the Australian business tax system and other aspects of tax policy, legislative drafting and tax administration. One of the major objectives of this Review was to optimise the international competitiveness of Australia’s taxation system. To this end, a key recommendation of the report when released to the public in September 1999, was to change Australia’s Capital Gains Tax provisions. This article examines the effect of these changes by comparing two taxpayer scenarios in Australia with twenty other countries. The analysis shows that the new CGT provisions, together with changes in individual tax rates, have provided a modest improvement for the Australian taxpayer relative to these other countries. However, the analysis also shows Australia’s position remains somewhat out of step with its regional neighbours.

Governments around the world have recognised the international transitory nature of goods and capital funds, in both direction and magnitude, as a direct result of each country’s prevailing taxation regime.[1] In recognising the significant potential economic benefits of an internationally competitive taxation system, successive Australian political parties have made unsuccessful attempts to bring about fundamental tax reform.[2] Paul Keating unsuccessfully attempted to introduce a broad-based consumption tax in his capacity as Australia’s Federal Treasurer in the Hawke Labor Government in 1985. Similarly, Dr John Hewson as leader of Australia’s then opposition party, the Liberal National Coalition, was defeated at the polls in 1993 when he based his election campaign largely on the introduction of a Goods and Services Tax (“GST”).

More recently however, the indelible signature of the Howard Government’s three terms in office has been one of extensive tax reform since it was elected in 1996. While the Howard Government adopted a relatively conservative approach to tax reform during its first term, there has since been an ongoing process of change in Australia’s tax regime at a macro level.[3] Many of the reforms implemented have been as a direct result of the recommendations of the Review of Business Taxation (“the Ralph Review”) reported to the Treasurer in July 1999 and released to the public in September 1999.[4]

The impetus for tax reform has been fuelled by, among others, a desire by the Howard led Australian Government and a demand from the Australian business community for a more internationally competitive taxation system.[5] While many recommendations of the Ralph Review were intended to promote the attractiveness of Australia as a destination for capital funds for institutional investors, changes made as a result of the recommendations were also intended to stimulate private investment and attract highly-skilled workers to Australia.[6] Included amongst the wide range of recommended reforms,[7] was the recommendation to implement changes to the provisions of Capital Gains Tax (“CGT”) together with changes in individual tax rates. A reduction in the overall taxation of capital gains was intended to remove a disincentive to investment in Australia, thus increasing the international competitiveness of Australia’s tax regime in comparison to a number of our international trading partners.[8] Specifically, recommendation 18.2 of the Ralph Review suggests that CGT be levied on 50% of the un-indexed capital gain and then taxed at the taxpayers marginal tax rate provided that the asset is held for at least one year.[9]

This recommendation has since been enshrined in legislation effective 21 September 1999 with the three Bills: the New Business Tax System (Integrity and other Measures) Bill 1999; the New Business Tax System (Income Tax Rates) Bill (No 2) 1999; and the New Business Tax System (Capital Gains Tax) Bill 1999, being passed by Parliament in December 1999.[10]

The purpose of this article is to evaluate the effectiveness of some of the changes to Australia’s CGT provisions and whether those changes have had their intended effect of making Australia’s taxation system more internationally competitive.

Specifically this study will examine Australia’s old and new CGT provisions in relation to capital gains derived by individual taxpayers, with the CGT provisions of Australia’s major international trading partners. This analysis will be used to assess whether the Ralph Review’s objective of improving the international competitiveness of Australia’s taxation system has been achieved.

The remainder of this study is organised as follows. The next section provides a background to the taxation of capital gains in Australia on individual taxpayers explaining the difference between the old and the new rules. Section 3 determines the conditions under which individual taxpayers in Australia with assessable capital gains can be compared with other countries. Section 4 provides the results of this international comparison. Section 5 discusses the limitations to this study, whilst Section 6 concludes the article.

On 14 August 1998 the Treasurer, the Hon Peter Costello MP commissioned Mr John Ralph AO, to chair the Business Income Tax Review in order to investigate and make recommendations for fundamental reform of Australia’s taxation regime. The subsequent Ralph Review was delivered to the Treasurer in July 1999 and subsequently released to the public in September 1999.

Once re-elected for its second tern, the Howard government believed it had a mandate to implement tax reform.[11] Diagram 1 illustrates the timing of the implementation of the Howard Government’s extensive tax reform agenda.

CGT in its original form was introduced in 1985 and applied to all prescribed assets acquired on or after 20 September 1985.[12] By way of overview, any gain on the sale of an individual’s assets were adjusted to allow for the original cost base of the asset to be indexed in line with inflation where assets are held for at least one year prior to disposal and then taxed at the individual’s marginal tax rates, with the provision to average the capital gain over 5 years. Averaging required that one fifth of the capital gain be added to the individual’s other income thus giving rise to a notional income. The tax payable was then equal to five times the difference between the tax payable on the notional income and the other income (excluding the capital gain).[13]

The new provisions as recommended by the Ralph Review, were implemented on 21 September 1999 and also apply to all assets acquired on or after 20 September 1985. Under the new provisions CGT is levied on only 50% of the capital gain at the individual’s marginal rates of tax, with no averaging provisions. The concession under the old rules of indexing the cost base to the rate of CPI inflation between the date of purchase and the date of sale was abolished for assets purchased after 21 September 1999. Existing asset holders who purchased their asset on or before 21 September 1999 have the option of having their capital gain assessed under the new rules or under the modified old rules, whereby averaging does not apply and indexation is frozen at 30 September 1999. As was indicated by Evans, “the intention of the rewritten legislation was to make the provisions more accessible and more flexible by providing a logical and coherent structure. There is little doubt that the earlier provisions (contained in Pt IIIA of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (Cth)) were an incoherent mess”.[14]

The extent to which the new CGT rules in Australia are more internationally competitive is a complex matter to evaluate and one that depends on a whole range of CGT provisions in each country. These provisions include: indexation of the cost base, the tax free threshold for capital gains, short term and long term gains, the amount of other income, the size of the capital gain, the type of asset and roll-over provisions and taxation rates. Evans and Sandford[15] using data as at 1 July 1998 computed the effective tax rates for individuals disposing of shares in six countries (United Kingdom, Ireland, United States, Canada, New Zealand and Australia). Using a taxpayer’s assessable income equivalent to twice the Gross Domestic Product per capita of the country concerned, (eg, Australia = A$71,726; United Kingdom = £23,896 and United States = US$54,840) they found in three alternative capital gain scenarios that Australia had the highest effective tax rate for capital gains in all scenarios. This analysis was completed before the implementation of the new CGT provisions discussed earlier and targets a high-income earner.

In order to facilitate a meaningful comparison of the CGT provisions worldwide, the research objective of this article is addressed by way of a comparison using two taxpayer scenarios. The first scenario involves a typical high-income earner who earns A$60,001 of other income thus reaching the top Marginal Tax Rate (“MTR”) in Australia, currently 47% (excluding the 1.5% Medicare levy). In this situation the taxpayer is assumed to have purchased shares for A$100,000 and sold them for A$140,000 after 5 years giving rise to a A$40,000 capital gain. Inflation is assumed to average 3% per annum.

The second scenario involves a typical low-income earner whose other income falls at the midpoint of the lowest (non-zero) MTR of 17% in Australia (excluding the 1.5% Medicare levy) ie A$13,001. This amount was selected because a number of countries levy capital gains at normal income tax rates which are progressive, so that lower income earners pay a lower marginal tax rate. This low-income scenario is becoming more common as many self-funded retirees have relatively low-income levels derived from investments in shares.[16] In the low-income scenario, the taxpayer is assumed to have purchased shares for A$20,000 and sold them for A$28,000 after 5 years, giving rise to an A$8,000 capital gain, which provides the same rate of return (40%) as the high-income scenario. Similarly, inflation is assumed to be 3% per annum as in the high-income scenario.

The comparison of the high and low-income scenarios enables an analysis of relative equity (vertical equity) of capital gains rules amongst the various countries. A comprehensive flexible financial model was developed which incorporated all the relevant taxation provisions and tax rates for the twenty-one countries under analysis. This will allow conclusions to be drawn as to the likely success or failure, of one of the key provisions of tax reform as outlined in the Ralph Review, namely whether the change in CGT provisions has led to an increase of the international competitiveness of Australia’s taxation regime.

To enable this comparison, a sample of twenty countries has been selected. This sample includes Australia’s top-ten trading partners, namely: China, Germany, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, New Zealand, Singapore, Taiwan, the UK and the US. To add to the sample, ten other countries were selected including those countries considered to be Australia’s regional/Asian neighbours. Specifically: Austria, Canada, France, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Ireland, Italy, Mexico and Sweden. The income year used as the basis of comparison is the 2001/2002 tax year.

Several assumptions are applied to both taxpayer scenarios and are listed below:

1. When comparing each country’s rules and rates, the Australian dollar amounts stated for both scenarios have been converted to each country’s denomination using the prevailing foreign currency exchange rates.[17]

2. Tax payers are not self-employed.

3. Shares are assumed to be bought and sold in each country’s stock exchange.

4. Shares have not been acquired from an Initial Public Offer.

5. Taxpayer treated as an individual with no dependants.

6. Taxpayer has no other capital gain or loss in the year of disposal as well as no capital loss brought forward from a previous year.

7. In regard to Canada, it is assumed that the taxpayer lives in Ontario and both federal and provincial taxes including surtaxes are included.[18]

CGT rules and tax rates for all countries in this study have been obtained from the CCH International Master Tax Guide,[19] in conjunction with the PricewaterhouseCoopers worldwide summary of individual taxes.[20] These rates and provisions are then compared by analysing the average tax rates (“ATRs”) applicable to the capital gain for each country.[21] A further dimension of this study is a comparison of Australia’s CGT provisions[22] both before and after the formal adoption of the Ralph recommendations in relation to CGT, thus providing prima facie evidence of the relative benefit or otherwise of the changes.

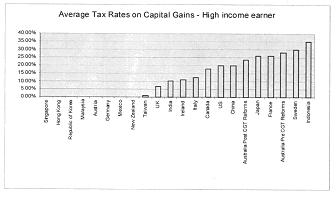

Chart 1 shows the ATRs on the capital gain within each country for the high-income scenario. This ranking of countries provides a measure of the international competitiveness of each country’s capital gains tax regime. As can be seen, Singapore, Hong Kong, Korea, Malaysia, Austria, Germany, Mexico and New Zealand all have zero capital gains tax. At the opposite end of the scale, Indonesian taxpayers are the most heavily taxed with an average CGT of 35%.

Chart 1

Closer examination reveals that for the high-income scenario, changes in the CGT provisions have moved Australia’s ranking against the other twenty countries from third highest to the fifth highest of the twenty-one countries. The ATR on capital gains in Australia is now lower at 23.5% under the new rules, as against 28.3% under the old rules. This compares with an average of 10.81% for the twenty foreign countries. This finding suggests that under the new rules, applying the 50% concession to the non-indexed capital gain and using the new tax rates, Australia’s CGT provisions have now moved in a favourable direction in the attempt to improve its relative international competitiveness. The suggestion is that the new rules are more internationally competitive than the old rules, albeit a modest improvement. Guest and Wyatt however found that as the rate of inflation increases, the old CGT rules using indexation and averaging are more competitive than the new rules.[23] Therefore, given a different taxpayer scenario the results may differ somewhat. Although there has been a modest improvement in Australia’s CGT provisions, of greater concern is the realisation that when compared to our Southeast Asian neighbours (excluding Indonesia), Australia still remains at a competitive disadvantage. Evans and Sandford[24] felt that the differences in the taxation of capital gains in the countries they reviewed were often a product of very different fiscal and political cultures. One explanation for Australia’s comparatively high CGT burden, is that it was brought about by the edict of the Howard Government to the Ralph Committee to ensure revenue neutrality[25] in the totality of its reform recommendations, thus providing motivation to retain the CGT albeit in a revised form.

Given that Australia is geographically located in South-East Asia and that it is largely countries within that region that form its major trading partners, it appears that Australia’s stance on CGT is somewhat out of step with the region. The extent to which this affects private investment is difficult to quantify, as the impact is a function of the propensity of taxpayers to realise capital gains. It is argued in the literature that this propensity is measured by capital gains realisation elasticity. Put simply, elasticity is a numerical measure of the “responsiveness of capital gains realisation to changes in the CGT rate. An elasticity of zero would imply the taxpayer behaviour is unaffected by taxes”.[26] The actual numerical value of these elasticity’s is a matter of conjecture yet to be satisfactorily resolved in the literature[27] and beyond the scope of this article. Notwithstanding these views, Reynolds[28] states that “lower capital gains taxes for individuals have powerful economic effects by encouraging entrepreneurship in Australia”. This was also the position adopted by the Ralph Review and has intuitive appeal as our Asian neighbours largely do not levy CGT. It therefore seems reasonable to conclude that the negative economic consequences of Australia’s CGT would be significant.

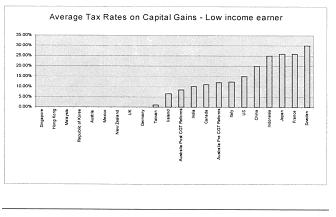

Chart 2 presents the ATRs on the capital gain for each country for the low-income scenario. This data shows that nine countries have ATRs on capital gains of zero. At the other extreme Sweden has the highest ATR of 30%. ATRs on capital gains for Australia are relatively lower when comparing the old with new rules.

Chart 2

This is not surprising given that CGT is levied at an individual’s marginal tax rate, which has now been reduced. However, the low-income earner is in a significantly better position under the new rules as the ATR has moved from 12.04% under the old rules to 8.50% using the new rules. According to Reynolds, the reduction of the CGT burden to low-income earners should provide stimulus for individual private investment by encouraging entrepreneurship.[29] Similarly, Australia’s ranking compared to the other twenty countries has moved favourably from having the eighth highest ATR on capital gains under the old rules, to having the tenth highest under the new rules. Table 1 shows a more detailed presentation of results by way of income scenarios and countries.

Table 1: ATR’s on Capital Gains by Country: Low and High Income Earners

|

ATR

|

|

ATR

|

||

|

Country

|

Low Income

|

|

Country

|

High Income

|

|

Singapore

|

0.00%

|

|

Singapore

|

0.00%

|

|

Hong Kong

|

0.00%

|

|

Hong Kong

|

0.00%

|

|

Malaysia

|

0.00%

|

|

Republic of Korea

|

0.00%

|

|

Republic of Korea

|

0.00%

|

|

Malaysia

|

0.00%

|

|

Austria

|

0.00%

|

|

Austria

|

0.00%

|

|

Mexico

|

0.00%

|

|

Germany

|

0.00%

|

|

New Zealand

|

0.00%

|

|

Mexico

|

0.00%

|

|

UK

|

0.00%

|

|

New Zealand

|

0.00%

|

|

Germany

|

0.00%

|

|

Taiwan

|

1.05%

|

|

Taiwan

|

1.05%

|

|

UK

|

6.71%

|

|

Ireland

|

6.60%

|

|

India

|

10.20%

|

|

Australia Post CGT Reforms

|

8.50%

|

|

Ireland

|

10.95%

|

|

India

|

10.20%

|

|

Italy

|

12.50%

|

|

Canada

|

11.19%

|

|

Canada

|

17.72%

|

|

Australia Pre CGT Reforms

|

12.04%

|

|

US

|

20.00%

|

|

Italy

|

12.50%

|

|

China

|

20.00%

|

|

US

|

15.00%

|

|

Australia Post CGT Reforms

|

23.50%

|

|

China

|

20.00%

|

|

Japan

|

26.00%

|

|

Indonesia

|

25.00%

|

|

France

|

26.00%

|

|

Japan

|

26.00%

|

|

Australia Pre CGT Reforms

|

28.29%

|

|

France

|

26.00%

|

|

Sweden

|

30.00%

|

|

Sweden

|

30.00%

|

|

Indonesia

|

35.00%

|

|

Average excluding Australia

|

9.18%

|

|

|

10.81%

|

These findings collectively confirm that the recommendations in relation to CGT of the Ralph Review, have achieved their objective of making Australia’s taxation system more internationally competitive under our two taxpayer scenarios. As with the previous high-income comparison, Australia’s position within the Southeast Asian region remains uncompetitive. However, an examination of Australia’s position relative to other countries with European ties shows our position is more competitive for the high-income earner within Australia, with the average tax rate on capital gains moving from 28.29% to 23.50% (see table 1). The low-income earner within Australia under the new rules now is approximately in the middle of the countries examined.

Further, Australia also made changes to their individual tax rates effective from 1 July 2000. The effect of this was to drop the low-income earner’s MTR from 20% to 17%, whilst the high-income earner’s MTR remained at 47%. In this comparison of Australia’s Pre and Post CGT reforms the old tax rates were used (MTR of 20% for low-income earner) for the pre CGT reforms and the new rates (MTR of 17% for low-income earner) for the post CGT reforms. This revealed a favourable movement of the ATR on the capital gain for the low-income earner from 12.04% to 8.5%. It does not however disentangle the effects of the two separate changes — the CGT discount of September 1999 and the changes to the tax rates from 1 July 2000. If the government had kept the existing tax rates and implemented the CGT changes, then the ATR on the capital gain for the low-income earner would have dropped to 10%. This still shows a favourable movement from 12.04% for the low-income earner, but not as favourable when combined with the tax rate changes. It would however still see Australia’s ranking compared to the other 20 countries move favourably from having the eight highest ATR on the capital gain under the old CGT rules to having the tenth highest under the new CGT rules. Further analysis revealed that if the CGT reforms were not implemented and the tax rate changes were, then the ATR on the capital gain for the low-income earner would have been 10.23%. Therefore as a result of introducing the CGT reforms the impact on the ATR on the capital gain for the low-income earner is also favourable further reducing the ATR on the capital gain to 8.5%. In regard to the high-income earner where the MTR remained the same at 47% after the tax rate changes, the whole favourable movement in the ATR on the capital gain from 28.29% to 23.5% is due entirely to the CGT reforms.

As most capital gains in Australia are realised by high-income earners,[30] one could argue that the analysis of the high-income scenario is more relevant than that of the low-income scenario. However, there is a strengthening trend for all Australians, including low-income earners, to participate in the share market through privatisation and other well-publicised initial public offerings. Wright and McCarthy[31] state that 41% of Australian adults currently own shares in publicly listed companies which represents the highest ownership rate in the world for private investors. Hence, an increasing number of low-income earners are likely to derive capital gains in the future. This is further supported in Taxation Statistics 1997/98 and Taxation Statistics 1999/2000 which shows that 7.6% of taxable individuals earning less than A$20,700 had a tax liability for net capital gains in 1999/2000 compared to 6.8% in 1997/98.

The findings reported in this study ought to be viewed in light of these limitations. Whilst the exchange rates used were current at the time of writing, the constant fluctuation in exchange rates, can be seen as limitation of this study. Should the same comparison be made at a different time, with different foreign exchange rates, the results may differ. This later observation may be more likely where the exchange rate places the amount of the capital gain near the threshold of a particular country’s tax rate change.

It is also recognised that large institutional investors, not individuals, were the primary target for the receipt of benefits provided by implementation of the Ralph Review recommendations and it is they rather than private investors that will be the primary beneficiaries of the changes to the CGT provisions.[32] The impact of the changes to institutional investors may well provide an area of further research.

In addition, this analysis uses a five-year time frame as the ownership period and this period is used as a basis for the calculation of any indexation of the cost base, changes in the tax rate applied, or any other method of discounting the CGT payable. Had the analysis used a different time frame, the results may have varied somewhat. For example, if the asset were held for an eight-year period, then the CGT in the UK would have been levied on 70% of the capital gain, rather than 85%, resulting in the UK appearing more competitive. Similarly a change in the assumed inflation rate of 3% per annum could also produce different results.

Finally, a comparison using exchange rates will not necessarily convert to the same standard of living in each country. For example A$60,000 translates to a very small amount of US$ but represents a significant Indonesian income. This arbitrary level of income may have a significant distorting effect on the tax outcomes in other countries. Therefore, further research could be conducted using another basis for international comparison such as average income levels; or income levels at twice the GDP per capita as used by Evans and Sandford[33] in their study; or a Big Mac index. The Big Mac Index can be used as a basis of comparison as it is “the perfect universal commodity” in that it is made to the same recipe, using a standard basket of goods and services, in over 80 countries.[34]

A key objective of the Ralph Review of Business Taxation was to optimise the international competitiveness of Australia’s taxation system. As a result, one of the recommendations of the Ralph Review was to implement changes to the provisions of Australia’s CGT as at 21 September 1999. The use of two taxpayer scenarios enabled the meaningful comparisons of Australia’s CGT provisions relative to twenty other countries selected. Overall there has been a favourable result for both income taxpayer scenarios within the parameters of the study, with lower average rates of tax on capital gains under the new CGT rules.

Further, this study demonstrates that the improvement in the ATR on capital gains for the low-income earner is a function of both changes in CGT rules and the equally important changes to tax rates. Whereas the improvement in the ATR on capital gains for the high-income earner, was due entirely to changes in the CGT rules.

Nonetheless these improvements have been modest and still leave Australia in a somewhat uncompetitive position when compared to our regional neighbours and major trading partners.

[*] Senior Lecturer, Department of Accounting and Finance, Monash University.

[∗∗] Assistant Lecturer, Department of Accounting and Finance, Monash University.

[∗∗∗] Senior Lecturer, Department of Accounting and Finance, Monash University. The authors gratefully acknowledge the valuable contribution by Associate Professor Les Nethercott.

[1] F Van der Ploeg, The Handbook of International Macroeconomics (1994).

[2] C Economou, “Resurrecting the GST” (1997) 8(3) Montage 1.

[3] N Shoebridge. “Unstoppable Tax Reform” (7th March 2002) Business Review Weekly 10.

[4] Review of Business Taxation, A Tax System Redesigned (1999) (“A Tax System Redesigned”) available at: www.rbt.tresury.gov.au/pubblications/papar4/index.htm.

[5] M Ekkel and R Taylor, “Mergers & Acquisitions Tax Yearbook 2000” (2000) 1(103) International Tax Review London 5.

[6] A Tax System Redesigned, above n 4, Recommendations 22.17-22.20.

[7] The Ralph Review contained 279 recommendations including; the removal of accelerated depreciation, the reduction of marginal tax rates for individual tax payers, the reduction of the company tax rate to 30%, removal of Wholesale Sales Tax and the controversial introduction of a Goods and Services Tax (“GST”).

[8] For detailed commentary of the major changes recommended by the Ralph Review see PricewaterhouseCoopers summary of Ralph Review final report at: www.pwcglobal.com.

[9] Previously capital gains were levied at 100% of the indexed net gain, with a system of averaging.

[10] New Business Tax System (Integrity and Other Measures) Bill 1999 (Cth); New Business Tax System (Income Tax Rates) Bill (No 2) 1999 (Cth); and New Business Tax System (Capital Gains Tax) Bill 1999 (Cth).

[11] D Parker, “The Reform Road: Legislating the GST” (1998) 68 Australian CPA 16.

[12] For further discussion on recent Australian CGT Developments, see C Evans “Taxing Capital Gains: One Step Forward or Two Steps Back?” [2002] JlATax 4; (2002) 5 Journal of Australian Taxation 114.

[13] Income Tax Rates Act 1986 (Cth), s 12.

[14] Evans, above n 12, 123.

[15] C Evans and C Sandford, “Capital Gains Tax: the Unprincipled Tax” [1999] British Tax Review 387.

[16] A Wright and S McCarthy, “Does Purchasing Stock in Australian Multinational Corporations Create International Portfolio Diversification?” (2002) 10(1) Multinational Business Review 79.

[17] Foreign exchange rates

sourced online from:

http://www.oanda.com/convert/classic using the typical bank rate +

1%.

[18] Evans and Sandford, above n 15, also chose Ontario in their analysis on the basis that Ontario is a typical province.

[19] CCH International Master Tay Guide (2001).

[20] PricewaterhouseCoopers. Worldwide Summaries, Individual Taxes 2001-2002 (2001).

[21] For example, in Australia the high-income scenario with a capital gain of A$40,000 triggering CGT exposure of A$20,000 which will be taxed at the individual’s marginal tax rate, in this case 47%, thus giving rise to a tax liability of A$9,400. This effectively results in an average tax rate of 23.5% ie A$9,400 tax payable divided by the A$40,000 capital gain.

[22] This analysis compares the old rules and tax rates (prior to 21 September 1999), with the new rules and tax rates (post 1 July 2000).

[23] R Guest and K Wyatt, “An Evaluation of the Changes to the Taxation of Capital Gains for Individuals” (2000) 6(2) Accounting, Accountability & Performance 109.

[24] Evans and Sandford, above n 15.

[25] Revenue neutrality is defined as maintaining pre-reform levels of business tax revenue, post recommendations and was a caveat on the recommendations of the Ralph Committee.

[26] C Evans, “Senate Inquiry Into Business Tax Reform — A Submission on the CGT Revenue Impact” (November 1999) 3. Sourced from: http://www.aph.gov.au.

[27] For a thorough discussion of the range and effect of elasticity see, A Auerbach, “Capital Gains Taxation in the United States: Realizations, Revenue and Rhetoric” (1988) 2 Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 595; L Burman and W Randolph, “Measuring Permanent Responses to Capital-Gains Tax Changes in Panel Data” (1994) 84(4) American Economic Review 595; Evans, above n 26; J Gravelle, Congressional Research Service, Limits to Capital Gains Feedback Effects (Report, 1991) 91.

[28] A Reynolds, “Capital Gains Tax Reform Options: Little Risk in Reducing Rate to 30 per cent” (1999) 34(2) Taxation in Australia 87.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Taxation Statistics

1999-2000, available at: http://ato.gov.au.

This reveals that only 7.6% of taxable individuals earning less than $20,700

had a tax liability for net capital gains. This compares

to 25% of individuals

earning greater than $100,000.

[31] Wright and McCarthy, above n 16.

[32] A Tax System Redesigned, above n 4.

[33] Evans and Sandford, above n 15.

[34] LL Ong, “Burgernomics: the Economics of the Big Mac” (1997) 16 Standard Journal of International Money and Finance 865.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/JlATax/2003/4.html