Journal of Australian Taxation

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Journal of Australian Taxation |

|

TAX RELATED BEHAVIOURS, BELIEFS, ATTITUDES AND VALUES AND TAXPAYER COMPLIANCE IN AUSTRALIA[∗]

By Pauline Niemirowski,[∗∗] Steve Baldwin[∗∗∗] and Alexander J Wearing[∗∗∗∗]

In this Australian Taxation Office (“ATO”) study, taxpayers were selected according to their historical tax compliance behaviour, in order to better understand community attitudes to tax. Seven non-business taxpayer groups were firstly identified as lodgment, audit risk or tax debt compliant according to their 1995 tax return data and then either compliant or medium or high risk non-compliant for lodgment, audit risk, or tax debt payment for the following 5 years. Three separate groups of tax agents, tax office staff and youth were also studied. Compliant and non-compliant taxpayer survey responses that included wider environmental factors were matched to each individual’s tax return data, but not for tax staff, tax agents or youth. Analyses identified relationships between tax-based values, beliefs, attitudes, knowledge and actual tax compliance behaviour. Non-compliance “intent” and “tolerance” of some tax avoidance were two key determinants of taxpaying behaviour. The implications of these results for ATO practices and policy are discussed.

This study was primarily designed to identify the beliefs, behaviours, attitudes and values (“BBAV”)[1] associated with taxpaying compliance. This was done by investigating the relationships between survey responses and tax return data and thereby to identify new compliance strategies based on behavioural indicators according to seven specific categories of taxpayer. The study also aimed to better understand taxpayer BBAVs to allow the development of strategies to improve compliance behaviour. Other questions were: to what extent do BBAVs relate to taxpayer compliance; are taxpayer attitudes different according to the category to which they belong; which tax related issues and policy impact most on taxpayer behaviours and compliance; and also how do current ATO client relationships affect taxpayer compliance?

A survey instrument that asked about various contextual, environmental, psychological, sociological and economic factors was developed. Survey data and tax return data were matched for each taxpayer from the main seven groups so that compliant and noncompliant behaviour could be understood in terms of satisfaction, lifestyle, competence, knowledge and fairness of pre Goods and Services Tax taxes, seriousness of law offences, beliefs, behaviours, attitudes and values, as well as selected items from tax returns.

The findings confirmed that compliant and non-compliant taxpayers’ compliance behaviour was in the main similar with only a few significant differences. In part, taxpaying behaviour related to beliefs, attitudes and values, ATO client service, sense of financial competence, difficulty in meeting tax obligations and perceptions about the necessity to use tax agents. “Intent” (to not comply) and “tolerance for some tax evasion” were significantly related to tax compliance behaviour. Very few taxpayers indicated a serious intent not to comply and there was only some tolerance of tax avoidance identified. These results reflected ATO’s Integrated Compliance Study (“ICS”)[2] research data that identified over 98% of non-business taxpayers as low to medium compliance risk probability on an ongoing basis.

Draft survey questionnaires were developed and piloted during 1998 and 1999. The questionnaire comprised two major sections, 94 BBAV questions and sections dealing with lifestyle. The topics included tax related behaviours, beliefs, attitudes and values, client experiences with the ATO, individual demographics, lifestyle factors, perceptions of the seriousness of laws, levels of satisfaction with various institutions and aspects of life and knowledge about specific taxes and their fairness. The context of the survey reflected the philosophy and principles of the ATO Compliance Model and ATO Taxpayers’ Charter.

The research population consisted of 7 taxpayer groups and 3 special interest groups. The 7 groups’ tax compliance level was determined by their lodgment, tax debt and audit risk probability behaviour. All 7 taxpayer group respondents were compliant in 1995 and either compliant or non-compliant from 1996-2000. The 1995 baseline of taxpayer compliance provided the necessary foundation to compare all 10 groups. For the 1995 tax financial year 7,180,441 Australian non-business taxpayers were registered on the tax database. Because of time and resource constraints the research design only targetted seven “medium” and “high” risk tax compliance behaviours. By focusing on only higher risk compliance behaviour the research outcomes were expected to be statistically representative. Eligibility for the group of 7 was restricted to taxpayers aged 18-65 who were deemed compliant in 1995 and were Australian residents with no bankruptcy indicator and no final return not necessary or deceased indicators. From the resulting seven compliance risk levels, random samples were drawn to receive the questionnaires. The other 3 groups were tax office staff selected at random from a pool of 2,500 “Personal Tax” only staff, tax agents selected at random from the pool of tax agents representing the taxpayer survey sample and younger taxpayers selected at random from the whole tax population database of Tax File Numbers registered to 18-20 year olds.

Compliant and non-compliant taxpayers from the 7-taxpayer medium and high-risk groups completed the surveys and these were matched to their own individual tax return information. Tax staff, tax agents and youth completed surveys but there was no matching with their tax return data. A total of 4000 survey questionnaires were sent out twice, (original mailout and with a reminder letter two weeks later). Questions included wider environmental factors encompassing behaviours, values, beliefs and attitudes, competency, fairness, satisfaction, lifestyle, seriousness of laws, pre-GST tax knowledge and experiences with ATO client service as well as perceptions about using tax agents.

The 4 key classes of variables considered significant drivers of tax compliance and non-compliance responses were Behaviour, Beliefs, Attitudes and Values (“BBAV”).[3] Broad definitions of these tax related constructs and samples of BBAV questions are provided below.

BEHAVIOUR (B) – observable human behaviour. In this case all tax behaviours related to tax return lodgment, tax debt payment, or not. For example, “Because it takes so much time, I put off completing my tax return”.

BELIEFS (B) – personal statements based on assumed personal knowledge or facts such as tax rates are high or tax agents are essential to ensure correct lodgment. For example, “Using a tax professional guarantees no errors in my tax returns”.

ATTITUDES (A) – personal opinion based judgments, evaluative such as the tax system is fair, or the ATO is the most professional public sector agency. For example, “I have found tax returns too difficult to do”.

VALUES (V) – universal social nouns widely held such as Australians do not “dob” on each other. For example, “In Australia we expect that everyone will lodge their tax return on time”.

Eleven of the 93 BBAV survey questions used for the 7 groups of taxpayers were identified as inappropriate for tax agents and were excluded. One other BBAV question was exclusive to tax agents and a block of questions regarding tax agent and client relationships was unique to the tax agent questionnaire. Otherwise, the bulk of the questions were identical and enabled the detection of any differences between taxpayers, tax agents, younger taxpayers and ATO staff data. Two open-ended questions were added to reduce any perceptions of “forced response” and provide useful qualitative data. Taxpayers were given the opportunity to provide comments about any concerns they had related to lodgment and tax debt payment and their experiences with ATO client service. The available data from around 10% of responses was analysed using content analysis and supported the ATO client service quantitative findings.

Thirty selected items from tax return forms were used to test the relationship between subjective and objective data (see Appendix B). Demographic data collected were age, marital status, gender, education level, annual income range and employment status, number of dependent children, occupation and type of home ownership. Lifestyle questions incorporated all relevant information needed to construct a holistic framework. The study encompassed a taxpayers’ compliance profile (tax return history), as well as their social, psychological, economic, business, income and life issues.

The study was called The Determinants of Australian Taxpayer Compliance to reflect the research interest in the determinants of tax compliance or non-compliance. Taxpayers received their questionnaires weeks before their tax lodgment was due (31 October) in order to promote both awareness of their obligations and enhance response rates. A second copy of the questionnaire was sent out with a reminder letter about 3 weeks later and a final reminder letter was sent a further two weeks later.

Selection of the 10-taxpayer research groups was based on previously identified (ICS) compliance risk behaviours and taxpayer segments deemed key to understanding the relationships between taxpayers and the ATO. The selection of 7 of the 10 groups was based on “reported” ATO evidence of compliance or non-compliance. These groups exemplified either reported compliance or non-compliance. For expediency, the levels of non-compliance were in the main limited to either medium or high-risk probability and compliance was “ATO identified and recorded” compliance. Compliant taxpayers as behavioural exemplars (either no risk or low risk) were the control group against which all other groups were compared. Compliance was defined as “reporting all income and paying all taxes in accordance with the applicable laws, regulations and court decisions”.[4] Non-compliance in this study was any behaviour that did not adhere to the definition of compliance, be it avoidance or evasion. “Tax evasion methods simply ignore or break the law, tax avoidance devices use the methods of law to neutralise its impact”.[5] The 3 special interest groups, tax staff, tax agents and younger taxpayers were included to construct a more complete framework of key players in tax relationships.

It was both necessary and desirable to match survey questions and tax return data for four reasons. The first was to evaluate the significance of using subjective and objective data independently or in combination. Secondly, it was possible to cross match and check demographic data using surveys and tax returns and to determine the accuracy of both sources. Thirdly, the design enabled researchers to perform a wider range of analyses and identify factors contributing to either tax compliance or non-compliance. Finally, by matching survey questions and tax return data according to compliance risk, it was possible to assess the ATO’s categorization of risk probability.

The questionnaire consisted of 94 BBAV questions, 81 BBAV questions for tax agents and 93 for all other taxpayers. Together, the BBAV data and tax return data formed the critical foundation that underpinned the research. Tax return data defined observable behaviour and BBAV defined as yet unknown taxpayer perceptions.

BBAV responses were measured using a 7 point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree, plus 8 for don’t know and 9 for not applicable. Reverse direction questions were not included in this section and in the main avoided. Scales in the remaining sections such as questions related to seriousness of laws, general life satisfaction and fairness of taxes also used Likert scales and ranged either 1-7 to identify the degree of perceived seriousness, or level of satisfaction and fairness. A few scales such as the tax knowledge quiz and lifestyle questions only required either a “yes”, “no” or “don’t know” response.

Significant measures were undertaken to guarantee the privacy and confidentiality of respondents. The de-identification process involved multiple coding and recoding that took into account the data matching exercise, use of external market researchers, electronic data storage and data destruction, as well as access to the information at various stages of analysis. Confidentiality and privacy was promised in the invitation to participate letters and also on the actual survey questionnaires. Respondents were also informed that their individual tax return data would be accessed and would be matched to their survey responses. They were also advised that involvement was voluntary and that irrespective of their decision, no ATO initiated action would result. All survey responses were received by the end of January 2001. During the 3 month period of survey mailouts and collection, a 24-hour hotline number was available for taxpayer enquiries. Generally, respondents’ main concern was privacy or possible ATO follow up action if they participated.

Table 1: Sample sizes and Response Rates according to taxpayer group

|

Group

|

Original Population

|

Survey Sample

|

Useable Responses

|

% Useable

|

|

ATO staff – Personal Tax

|

2,500

|

500

|

358

|

71.6

|

|

Younger taxpayers

|

NA

|

500

|

122

|

24.4

|

|

Tax agents

|

NA

|

200

|

62

|

31.0

|

|

Compliant 1995-2000

|

1,127,989

|

900

|

292

|

32.4

|

|

Lodgment Medium risk

|

168,571

|

300

|

82

|

27.3

|

|

Lodgment High risk

|

1,616

|

200

|

40

|

20.0

|

|

Tax debt Medium risk

|

187,026

|

300

|

92

|

31.3

|

|

Tax debt High risk

|

85,485

|

200

|

58

|

29.0

|

|

Audit risk

|

160,487

|

500

|

185

|

37.0

|

|

Combined risk

|

53,501

|

400

|

90

|

22.5

|

|

Total taxpayers

|

1,784,675

|

4000

|

1381

|

34.6

|

Sample sizes were selected according to Australian Bureau of Statistics (“ABS”) constructed tables for power of 90% and confidence of 95%. The power of a sample survey is the probability of correctly detecting a difference between the true population proportion and a hypothesised true value. Because of the nature of the survey, it was not possible to assume with confidence that the responses obtained were random samples of the randomly selected target populations. An examination of the “representativeness” of the responses was carried out on the demographic and tax characteristics of the responding taxpayers in each group. Because of the number of data fields involved, some categories displayed varying degrees of bias. Overall, over two thirds of the “primary” survey fields (marital status, gender, tax agent status, age, CSA status, residence and taxable income) displayed bias measures of <10% outside of statistical 95% confidence limits. The tax return records of responding taxpayers were compared with those for the total mailout sample for statistically significant differences in sample and whole population profiles. The response data appeared sufficiently representative to be confident in the statistical analyses.

Survey questions were developed to assess BBAV issues for non-business individual taxpayers. Behaviour was focussed on taxpayer lodgment and tax debt as well as their use of ATO services and tax relationships. Beliefs and Attitudes were considered from the perspective of how taxpayers perceived their tax relationship and tax related environment. Values focused on tax matters only and did not target other personal values, institutional values and societal values.

First, factor analyses were conducted separately on behaviour, belief, value and attitude based questions to identify reliable BBAV scales. Only 6 statistically reliable measures were identified. The results for the 6 BBAV scales and other scales are shown in table 2 below. A summary of interpretation of each scale is in table 3.

Table 2: Reliability of BBAV Scales and Other Determinants

Scales

|

SCALES

|

BBAV scales & 5 Determinants scales

|

|

• Belief2 — I believe the ATO is fair and

professional

• Belief4 — I believe I know enough about tax to meet my

obligations

• Behaviour1 — I use an agent to avoid tax anxiety

• Behaviour2 — Tax returns take too much effort, so I put it

off unless there is an incentive

• Attitude1 — I tolerate / accept a certain level of tax

avoidance

• Value1 — Australians believe the tax system is

fair

|

|

Belief2

|

0.70 (4 items)

|

|

|

|

Belief4

|

0.63 (3 items)

|

|

|

|

Behaviour1

|

0.78 (5 items)

|

|

|

|

Behaviour2

|

0.77 (4 items)

|

|

|

|

Attitude1

|

0.68 (4 items)

|

|

|

|

Value1

|

0.76 (2 items)

|

|

|

|

Seriousness of Laws

|

0.86 (7 items)

|

|

|

|

Satisfaction

|

0.79 (11 items)

|

|

|

|

Knowledge of Tax Laws

|

0.85 (7 items)

|

|

|

|

Fairness of Taxes

|

0.86 (7 items)

|

|

|

|

Knowledge quiz

|

0.85 (6 items)

|

|

Table 3: Means and SDs for the Behaviour, Beliefs, Attitudes and Values scales (N=1318)

(Likert scale 1→ = strongly disagree → strongly agree)

(** Scale – 1, 0, 1 = no, don’t know, yes)

|

Scales

|

Interpretation of subscale

|

Mean

|

SD

|

Min

|

Max

|

|

Belief 2*

|

I believe the ATO is fair and professional

|

4.32

|

.94

|

1

|

7

|

|

Belief 4*

|

I believe I know enough to meet my tax obligations

|

4.27

|

1.36

|

1

|

7

|

|

Behaviour 1*

|

I use a tax agent to avoid tax anxiety

|

4.36

|

1.43

|

1

|

7

|

|

Behaviour 2*

|

Tax returns take too much effort so I put it off unless there is an

incentive

|

3.21

|

1.35

|

1

|

7

|

|

Attitude 1*

|

I tolerate a certain level of tax avoidance

|

2.61

|

.99

|

1

|

7

|

|

Value 1 *

|

Australians believe the tax system is fair

|

3.02

|

1.61

|

1

|

7

|

|

Knowledge 1**

|

True of false basic tax quiz

|

.66

|

30

|

-.60

|

1.00

|

|

Knowledge 2**

|

Knowledge of pre GST taxes

|

-.11

|

.58

|

-1

|

1

|

|

Satisfaction

|

Satisfaction with self and institutions

|

4.74

|

.97

|

1

|

7

|

|

Laws

|

Seriousness of laws

|

5.47

|

1.37

|

0

|

7

|

|

Fairness

|

Fairness of pre GST taxes

|

4.07

|

.75

|

1

|

7

|

The mean scores indicated that all 10 groups of taxpayers (all combined survey responses excluding tax agents) did not tolerate high levels of tax avoidance and did not believe the tax system was fair. They were neutral about the tax office being fair, their ability to handle their financial affairs and using a tax agent to avoid tax anxiety. They disagreed with the propositions that tax returns took too much effort and that they possessed a basic knowledge of tax. Taxpayers also acknowledged the seriousness of various laws. These sub-scales potentially described taxpayers’ overall perception of how the tax system operated at government, tax administration, community and individual levels. How taxes were perceived

depended on how difficult the system was to understand, level of taxpayer engagement and whether the taxation system as a whole was effective in producing wide-ranging community based, equitable and efficient tax outcomes.

Correlations between the 6 BBAV scales and the selected survey scales reported in table 4 were low but statistically significant. Use of a tax agent to avoid tax anxiety was negatively associated with both perceived fairness and tax knowledge. Belief that taxpayers had enough tax knowledge was positively associated with tax knowledge scale. Respondents who reported that they did not believe that pre-GST taxes were fair or did not know enough about them, used a tax agent to avoid tax anxiety. Where respondents reported that they had low regard for the seriousness of specific offences, or were dissatisfied with their personal and wider environment, they put off their tax obligations, if there was no incentive to meet them.

Table 4: Correlations Between BBAV Scales and Selected Survey Scales (N=1318)

** Statistically significant at the <.0001 level 2-tailed

|

|

Seriousness of Laws scale

|

Satisfaction scale

|

Fairness scale

|

Knowledge quiz

|

Tax Knowledge

|

|

Value1

|

|

.21**

|

.29**

|

|

.13**

|

|

Attitude1

|

-.14**

|

|

|

|

-.11**

|

|

Behaviour1

|

|

|

-.25**

|

|

-.34**

|

|

Behaviour2

|

-.12**

|

-.12**

|

|

|

|

|

Belief2

|

|

.17**

|

.28**

|

.10**

|

.17**

|

|

Belief4

|

|

|

.22**

|

.10**

|

.36**

|

• Value1 – Australians believe the tax system is fair

• Attitude1 – I tolerate/accept a certain level of tax avoidance

• Behaviour1 – I use an agent to avoid tax anxiety

• Behaviour2 – Tax returns take too much effort, so I put it off unless there is an incentive

• Belief2 – I believe the ATO is fair and professional

• Belief4 – I believe I know enough about tax to meet my obligations

The 6 BBAV scales utilised only 22 of the possible 93 BBAV survey questions and further analyses of the remaining 71 questions identified 4 new scales relevant to taxpayer behaviour. These scales addressed the broader contextual experience of taxpayers as well as possible determinants of tax compliance. The 4 new scales were: (1) Intent (non-compliance), (2) Tax is difficult, (3) Why it’s necessary to use a tax agent and (4) ATO Client service. Results of the 4 scales’ statistical reliability are shown below in table 5.

Table 5: Additional BBAV Scale Reliabilities - See Appendix A for List of Items Used in Each Scale

|

Scale

|

α Reliability

|

|

|

|

|

Experiences of ATO client service

|

0.85 (8 items)

|

|

Intent to not comply (Non-Compliance)

|

0.71 (7 items)

|

|

Why it’s necessary to use tax agents

|

0.77 (5 items)

|

|

Difficulty of tax

|

0.70 (4 items)

|

The ATO’s observed compliance risk (low, medium or high risk for lodgment, tax debt or audit) as used for segmentation in this study, assumed taxpayers’ propensity to either comply or not comply. The “Intent” scale was constructed because the available and reliable behaviour sub-scales of BBAV were restricted to scales that identified tax anxiety and a form of procrastination dependent upon incentives. The development of the Intent scale was informed by the article of Wearing and Headey.[6] The non-compliance intent scale consisted of 7 of the 93 questionnaire items – a combination of values, attitudes and behaviour items. These 7 questions (see

Appendix A) addressed 5 key factors: Taxpayer’s acknowledgment of their responsibility to comply, actual ability to comply (guess answer), how much to comply or not comply (claim a little or a lot more in deductions) and also why not to comply (even things up, doesn’t do anyone any harm, it doesn’t matter). The five resultant levels of “Intent” ranged from lowest to highest, with responses ranging 1-5 from a possible 7. That is, no taxpayers expressed a seriously high intent to not comply.

Table 6: Non-Compliance Intent by Percentage (Scale 1-7)

Low = 1-3, Medium = 4, High =5, Very high =6-7

|

Group classification

|

1

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

5

|

|

Compliant taxpayers

|

31.5

|

53.1

|

12.3

|

2.1

|

|

|

All Non-compliant taxpayers

|

28.7

|

50.6

|

16.3

|

3.8

|

0.5

|

|

Staff

|

49.7

|

43.9

|

5.6

|

0.8

|

|

|

Tax agents

|

51.6

|

37.1

|

11.3

|

|

|

|

Youth

|

22.3

|

44.6

|

25.6

|

7.4

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Non-compliant Lodgment Medium risk

|

29.3

|

47.6

|

18.3

|

3.7

|

1.2

|

|

Non-compliant Lodgment High risk

|

20

|

55

|

25

|

|

|

|

Non-compliant Debt Medium risk

|

33.3

|

49.5

|

12.9

|

4.3

|

|

|

Non-compliant Debt High risk

|

36.2

|

44.8

|

17.2

|

1.7

|

|

|

Audit risk

|

26.5

|

55.7

|

13.5

|

3.8

|

0.5

|

|

Combination risk

|

27

|

46.1

|

19.1

|

6.7

|

1.1

|

Most taxpayers reported low levels of non-compliance “Intent”. Tax staff reported the lowest levels of intent to not comply. The non-compliant sample had a wider distribution of intent. Tax agents scored only in the 1-3 range and youth reported the highest proportion of intent at level 3. Only a small proportion of taxpayers registered level 4 and even fewer at level 5. Whether levels 3-5 indicated any future non-compliance intent was not clear because tax return data was not available for the youth sample and the sample size at level 5 was too small for reliable analysis. No taxpayers were recorded at levels 6 or 7.

To better understand the motivation behind risk behaviour, “Intent” (to not comply) was used as the dependent variable in the preliminary regression analyses. The following results highlighted differences between the compliant group, the combined non-compliant group, tax staff, tax agents and youth. Analyses attempted to identify whether using survey data alone, tax return data alone or survey and return data combined were more effective means of identifying intent.

Table 7: Correlations Between Scales in Tables 3 and 5 (N=1318)

** Statistically significant at the <.0001 level 2-tailed

|

|

Intent (Non-compliance)

|

Tax is difficult

|

ATO client service

|

Necessary to use agents

|

|

Value1

|

|

|

.34**

|

|

|

Attitude1

|

.82**

|

|

-.13**

|

|

|

Behaviour1

|

.19**

|

.13**

|

-.27**

|

.36**

|

|

Behaviour2

|

.31**

|

|

-.17**

|

|

|

Belief2

|

-.19**

|

-.10**

|

.88**

|

-.18**

|

|

Belief4

|

-.19**

|

|

.29**

|

-.32**

|

• Value1 – Australians believe the tax system is fair

• Attitude1 – I tolerate/accept a certain level of tax avoidance

• Behaviour1 – I use an agent to avoid tax anxiety

• Behaviour2 – Tax returns take too much effort, so I put it off unless there is an incentive

• Belief2 – I believe the ATO is fair and professional

• Belief4 – I believe I know enough about tax to meet my obligations

Correlation results reported in table 7 were low but highly significant. Behaviour2 (putting off completing tax returns if there is no incentive) was positively associated with intent (to not comply) and negatively with ATO client service. Value1 (belief that the tax system was fair) was positively associated with ATO client service. Behaviour1 (use of tax agent to avoid tax anxiety) was positively associated with use of a tax agent. Belief4 (knowing enough to meet tax obligations) was negatively associated with necessity to use agent. The direction of the relationships validated the research model and also confirmed the relationships between variables.

Non-compliance intent was weakly correlated with observed historical lodgment behaviour and default (tax debt) status for 1999 tax year (see table 8). There were, however, no significant correlations between intent and lodgment behaviour for the 2000 tax year, possibly because lodgment of returns were still incomplete.

Table 8: Correlations Between Intent, Lodgment 1999 & 2000, Debt 1999 & ATO Compliance Code

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level,. * at the 0.05 level (2-tailed)

# Compliance code: Compliant =1, non-compliant =0

|

N=725

|

INTENT

|

LODG1999

|

LODG2000

|

|

INTENT

|

|

.08**

|

|

|

LODG1999

|

.08*

|

|

|

|

LODG2000

|

|

.47**

|

|

|

Default1999 (debt)

|

-.09*

|

|

-.21**

|

|

Compliance Code#

|

.08*

|

.13**

|

.17**

|

• INTENT – non-compliance intent scale

• LODG1999 – National Tax System lodgment 1999

• LODG2000 – National Tax System lodgment 2000

• Default1999 –National Tax System 1999 – Tax debt status

• COMPLIANCE CODE – group membership (compliant or non-compliant)

In the ATO’s ICS of 8,000,000 non-business taxpayers, less than 2% of the population were identified as high compliance risks. The ICS study, however, identified several key “life events” as non-compliance risk probabilities – factors indicating a change of circumstances such as child support liability, level of medical expenses, change in marital status or change in residential address. The current study did not find similar results when analysing 1999 and 2000 tax return data only and tax return variables (see Appendix B).

Preliminary analyses indicated that there was little difference in results between the various non-compliant groups so all 6 non-compliant groups were combined for the purpose of multiple regressions. The analyses compared 1 compliant group with 1 non-compliant group unless otherwise stated. The β coefficients from an ordinary least squares regression model (stepwise procedure) using all 93 BBAV questions and research scales to predict compliance or non-compliance are reported below in tables 9 and 10.

Table 9: Top Two Questionnaire Based Predictors of Intent for COMPLIANT TAXPAYERS

|

BBAV

|

Question or Scale

|

β value

|

t-value

|

Sig

|

Adjusted R2

|

|

|

Total contribution of 10 predictors was F(10,116)=15.16,

p>.0001

|

|

|

|

.55

|

|

Attitude

|

When the amount of avoidance is small ATO should let it go

|

.40

|

5.96

|

.000

|

.20

|

|

Fair

|

Pay As You Earn is a fair tax

|

-.21

|

-3.11

|

.002

|

.31

|

Table 10: Top Three Questionnaire Based Predictors of Intent for NON-COMPLIANT TAXPAYERS

|

BBAV

|

Question or Scale

|

β value

|

t-value

|

Sig

|

Adjusted R2

|

|

|

Total contribution by 16 predictors was F(16,208) 17.39

p>.0001

|

|

|

|

.56

|

|

Attitude

|

When the amount of avoidance is small the ATO should let it go

|

.17

|

3.19

|

.002

|

.13

|

|

Value

|

Tax system should contribute to economic growth

|

-.15

|

-3.06

|

.003

|

.21

|

|

Behaviour

|

I put off my tax return because I don’t like dealing with government

agencies

|

.17

|

3.37

|

.001

|

.27

|

Intent non-compliance for Compliant taxpayers was accounted for by taxpayers whose attitude was that the ATO should let small amounts of avoidance go and who perceived the Pay As You Earn (“PAYE”) tax system as unfair. Others predictors were not knowing where to go for tax advice, disagreeing that ATO staff treated them fairly, supporting the abolition of tax returns for non-business individuals, agreeing that it was easy to claim for more than you were entitled to and that it took too long to find information about tax returns.

The strongest predictor of non-compliance intent for Non-Compliant taxpayers was the attitude that the ATO should let small amounts of avoidance go. Taxpayers also put off completing tax returns because they did not like dealing with government institutions, disagreed tax evasion was a serious offence, could not afford to use a tax agent if they wanted to and were satisfied with their ability to deal with their financial affairs.

The dominance of attitude over other beliefs, behaviour and value factors was not expected. Even though the study was exploratory, an extensive literature review indicated that issues like difficulty with tax and perceptions about fairness and equity would dominate. The results in tables 11 to 13 validated segmenting the taxpayer population into a user and service provider model, as there are distinct differences between general taxpayers, tax staff, tax agents and youth.

Table 11: Top Four Questionnaire Based Predictors of Intent for ATO STAFF.

|

BBAV

|

Question or Scale

|

β value

|

t- value

|

Sig

|

Adjusted R2

|

|

|

Total contribution by 17 predictors was F(17,160) 14.64,

p>.0001

|

|

|

|

.59

|

|

Behaviour

|

May have claimed more than entitled to

|

.38

|

7.14

|

.000

|

.21

|

|

Belief

|

Paying tax necessary for Fed government to operate effectively

|

-.18

|

-3.22

|

.002

|

.28

|

|

Law

|

Tax evasion is a serious offence

|

-.18

|

-3.29

|

.001

|

.33

|

|

Attitude

|

Tax returns are too difficult to do

|

.23

|

3.75

|

.000

|

.36

|

The strongest predictor of tax staff non-compliance was reporting that they had claimed more than they were entitled to. Overall tax staff who reported over claiming, disagreed that tax was necessary for effective government, disagreed that tax evasion was a serious offence, thought tax was difficult, disagreed that the ATO was fair with taxpayers it audited, agreed the ATO should let small amounts of avoidance go, put off completing their tax returns if there was no refund and were self preparers reported a higher propensity to intend non-compliance. It was unclear whether non-compliance was a deliberate outcome or reflected dissatisfaction with ATO’s client service culture. It appeared that staff possibly considered the ATO was not severe enough with evaders and that non-compliant taxpayers got away with too much.

Table 12: Top Five Questionnaire Based Predictors of Intent for YOUTH

|

BBAV

|

Question or Scale

|

β value

|

t- value

|

Sig

|

Adjusted R2

|

|

|

Total contribution by 13 predictors was F(13,48) 38.59,

p>.0001

|

|

|

|

.91

|

|

Belief

|

It’s difficult to complete a 100% correct tax return

|

.24

|

4.34

|

.000

|

.32

|

|

Lifestyle

|

Did you use TaxPackExpress in 1999?

|

.33

|

6.16

|

.000

|

.44

|

|

Attitude

|

Anyone who over claims on their returns should be severely penalised

|

-.33

|

-6.42

|

.000

|

.54

|

|

Attitude

|

If there was a “fraud hotline” I would report people who evaded

their taxes

|

-.20

|

-4.16

|

.000

|

.62

|

|

Attitude

|

When the amount of avoidance is small ATO should let it go

|

.37

|

7.79

|

.000

|

.69

|

For the youth sample the most significant predictor of non-compliance intent was the belief that it was difficult to complete a 100% correct tax return. Other significant factors were disagreement that tax offenders should be severely penalised, non-support for a fraud hot-line, belief that it was easy to claim more than you are entitled to, agreement that tax returns should be lodged on time every year and fear of what the ATO might do if they forgot to lodge. There appeared to be a level of uncertainty as well as concern about tax. Despite the dismissive attitude, the overall impression was one of avoidance of dealing with difficult issues rather than deliberate tax avoidance or evasion. The results supported the hypothesis that youth lacked tax competence.

Table 13: Questionnaire Based Predictors of Intent for TAX AGENTS

|

BBAV

|

Question or Scale

|

β value

|

t- value

|

Sig

|

Adjusted R2

|

|

|

Total contribution by 13 predictors was F(13,48) 38.59,

p>.0001

|

|

|

|

.68

|

|

Belief

|

It’s difficult to complete a 100% correct tax return

|

.38

|

7.14

|

.000

|

.15

|

|

Lifestyle

|

Did you use TaxPackExpress in 1999?

|

-.18

|

-3.22

|

.002

|

.30

|

|

Attitude

|

Anyone who over claims on their returns should be severely penalised

|

-.18

|

-3.29

|

.001

|

.42

|

|

Attitude

|

If there was a “fraud hotline” I would report people who evaded

their taxes

|

|

|

|

.56

|

|

Attitude

|

When the amount of avoidance is small ATO should let it go

|

.23

|

3.75

|

.000

|

.36

|

For tax agents the major concern that influenced intent was whether or not there would be adequate funds available for retirement. This factor and perceptions of the unfairness of prescribed payments (“PPS”) accounted for almost half of the contribution F(2,41) 9.58, p>.0001 with an adjusted R2 of .30. Tax agents working environment accentuated their focus on the financial tensions between personal income and tax revenue collection and the need to secure funds for future requirements. The issue of fairness was also significant for tax agents. A predisposition to develop strategies to ensure financial security could be a reflection of the age profile of tax agents, 82% of them being over the age of 40 at the time of the survey.

Self reported survey questionnaire data when used alone provided a range of factors that identified what collectively contributed to the various groups’ taxpaying behaviours. Behaviours, Beliefs, Attitudes and Values all contributed to the regression models and a few Laws, Fairness and Satisfaction items appeared in group models. Generally these results supported the hypotheses that there were differences between the group samples and that there were diverse reasons for non-compliance.

To confirm the value of analysing either survey or tax return data independently, or matched survey questionnaire and tax return data, 1999 and 2000 tax return data were matched with taxpayer’s survey questionnaire data. Using intent to not comply as the dependent variable, all scales and residual questions, multiple regressions for Compliant and Non-compliant samples were tested for each year separately. Only 1999 year is reported here, as it was the most complete data set at the time of the study. Results are detailed in tables 14 and 15 below.

Table 14: Matched Questionnaire & 1999 Tax Return Based Predictors of Intent for COMPLIANT TAXPAYERS

|

BBAV

|

Question or Scale

|

β value

|

t- value

|

Sig

|

Adjusted R2

|

|

|

Total contribution by 19 predictors was F(19,116) 13.41,

p>.0001

|

|

|

|

.67

|

|

Attitude

|

Q53 When the amount of avoidance is small the ATO should let it

go

|

.33

|

5.34

|

.000

|

.20

|

|

Fair

|

Pay As You Earn tax is fair

|

-.27

|

-4.47

|

.000

|

.31

|

The 2 strongest survey questionnaire based predictors of non-compliance intent in the Compliant sample was the attitude that when the amount of avoidance is small the ATO should let it go and whether PAYE tax is fair. Two tax return items also contributed to the predictor model; Taxable income amount and Salary/wages amount. Their contributions were small but significant. Once again an attitude item dominated explaining intent to not comply.

Table 15: Matched Questionnaire & 1999 Tax Return Based Predictors of Intent for NON-COMPLIANT TAXPAYERS

|

BBAV

|

Question or Scale

|

β value

|

t- value

|

Sig

|

Adjusted R2

|

|

|

Total contribution by 16 predictors was F(16,186) 14.91,

p>.000

|

|

|

|

.55

|

|

Attitude

|

When amount of avoidance is small ATO should let it go

|

.12

|

2.18

|

.031

|

.12

|

|

Value

|

Tax law is strict so not many abuse it

|

.23

|

4.35

|

.000

|

.26

|

|

Behaviour

|

I might have claimed more deductions than entitled to

|

.12

|

2.37

|

.019

|

.54

|

|

Satisfaction

|

Satisfied with standard of living

|

-.11

|

-2.04

|

.043

|

.55

|

The 2 key predictors of non-compliance intent for non-compliant taxpayers were the attitude that when the amount of avoidance is small the ATO should let it go and the value that because tax laws are so strict few abuse them. The only tax return data in the model was total employment termination payment amount. Other contributing factors were whether tax evasion was a serious offence, whether taxpayers could afford to use a tax agent if they wanted to, whether they were satisfied with their ability to handle financial affairs and whether they had over claimed. A key finding from the tax return data matching was that survey questionnaire items dominated the models. Interestingly, more questionnaire items were present in the regression model with the inclusion of tax return data. Despite the same attitude item being a key predictor for intent, there are substantial differences between the compliant and non-compliant groups. These will be discussed later.

The next step in analysing the value of survey questionnaire and tax return data was to test the value of tax return data alone. Results are reported in tables 16 and 17.

Table 16: 1999 Tax Return Based Predicators of Intent for COMPLIANT TAXPAYERS

|

Tax return item

|

β value

|

t- value

|

Sig

|

Adjusted R2

|

|

Total F(1,291)6.19, p>.0001

|

|

|

|

.05

|

|

Total rebates amount

|

.15

|

2.61

|

.01

|

.02

|

|

Work related deductions amount

|

.20

|

3.18

|

.002

|

.03

|

|

Assessment issued amount

|

-.17

|

-2.65

|

.009

|

.05

|

The effectiveness of using the selected tax return data as a predictor of non-compliance intent for compliant taxpayers was very limited. Total tax rebates, work related expense deductions and the assessment issued amount were the only items predicting intent.

Table 17: 1999 Tax Return Based Predictors of Intent for NON-COMPLIANT TAXPAYERS

|

Tax return item

|

β value

|

t-value

|

Sig

|

Adjusted R2

|

|

Total F(1,502)7.58, p>.001

|

|

|

|

.05

|

|

Total ETP amount

|

.14

|

3.22

|

.001

|

.02

|

|

Other deductions amount

|

-.09

|

-2.14

|

.03

|

.03

|

The two statistically low predictors of non-compliance intent for the combined six groups of non-compliant taxpayers were Employment Termination Payment amount and other deductions amount. Support for using tax return data alone was not substantiated, as tax return data did not effectively explain tax compliance. The results thus far did, however, support combining all non-compliant taxpayer groups, not only because of sample sizes but because there was no identifiable difference in their BBAV and tax compliance behaviours. All these results provided the platform from which to consider how BBAV, compliance behaviour (especially intent) interacted and produced either tax compliance or non-compliance.

Ninety two percent of tax agents agreed that tax evasion was a serious offence, as did 86.2% of compliant taxpayers, 85.3% of tax staff, 80.3% of non-compliant taxpayers and 72.7% of youth. Twelve point eight percent of youth thought tax evasion was not a serious offence, as did 9.6% of non-compliant taxpayers, 5.7% of tax staff, 3.5% of compliant taxpayers and 1.6% of tax agents. Overall tax evasion ranked 4th out of seven legal offences. Drink driving, stealing and doing drugs ranked above tax evasion and shoplifting, driving an unregistered vehicle and not having the proper licence ranked below.

Whilst the level of acknowledgment of the seriousness of tax evasion was high there were several factors that impacted taxpayers’ perceptions. Taxpayers did not appear to fully understand the consequences of tax evasion for the community. Any attitude such as “it did not do anyone any harm” could impact on behaviour. For example, evasion, if viewed as a “rules and regulations” problem rather than theft, fraud or illegal law breaking might produce different behaviour. There are no immediately observable, serious or deadly consequences of tax avoidance as with drink driving or drug/substance abuse. Tax evasion has a social cost, but the consequences are not self-evident. Because tax offenders are rarely if ever incarcerated for their offences, their names not reported (unless it is a sensational case) and no wider shame is associated with the offence, tax evasion could be seen more as something that everyone does. There was no overall identifiable tolerance level for minimal/ acceptable tax evasion. Taxpayer respondents disclosed that they had over claimed on deductions, but disagreed that offenders should be jailed or that they would “dob-in” tax evaders.

Table 18: Seriousness of Tax Evasion by Percentage According to Taxpayer Group

|

|

Serious%

|

Neutral %

|

Not serious %

|

|

Compliant

|

86.2

|

10.2

|

3.5

|

|

Non-Compliant

|

80.3

|

10.1

|

9.6

|

|

Staff

|

85.3

|

9.1

|

5.7

|

|

Tax agents

|

91.8

|

6.6

|

1.6

|

|

Youth

|

72.7

|

14.5

|

12.8

|

Song and Yarbrough’s research provided an insight into subjective judgment and tax ethics. Their research population did not see tax evasion and fraud as serious crimes. Compliance behaviour was explained by fear of detection by enforcement agencies and the inequitable use of tax loopholes. Their survey research findings emphasised high levels of “tax dissatisfaction”, perceived unfairness, declining levels of tax ethics and political trust. There were concerns that the tax administration did not reflect the desires of the people – “taxation without representation”.[7]

Governments require legitimacy from their citizens: ideological, functional and moral legitimacy. Without support for political and economic principles and effective institutions, Yankelovich concluded that “tax attitudes may reveal more about the declining functional and moral legitimacy of governments”.[8]

Qualitative data provided insights into taxpayers’ perceptions and ATO experiences. Content analysis identified some already known factors and highlighted others not clearly recognised. These factors might affect not only taxpayers’ relationship with the ATO but their compliance levels as well.

Question (a) “Did you contact the ATO” (1998/99) and “Did you experience any difficulties with the service?”

Question (b) “What are some of your concerns that you might have in dealing with the ATO about completing an overdue tax return or paying a tax debt?”

One hundred and fourteen people offered responses about ATO client service, a rate of 11.1%. Of those who did complain, many had multiple complaints. Complaints about ATO client service were varied but could be distributed into 9 categories. The most frequent complaints were telephone-waiting times and that staff did not know the answer to questions. For example, “Being on hold for long period of time and being transferred several times before being assisted”.

The types and totals are summarised in tables 19 and 20 below.

Table 19: Question (a) Types of Experienced Service Difficulties

|

Complaint type

|

Number

|

%

|

|

Telephone waiting times

|

38

|

24.6

|

|

Tax Office didn’t know answer

|

38

|

24.6

|

|

Being passed around

|

19

|

12.3

|

|

Rudeness and insensitivity

|

16

|

10.4

|

|

Unsatisfactory outcome and/or slow delivery

|

16

|

10.4

|

|

Other/unclear complaint

|

11

|

7.1

|

|

Poor Tax Office English language skills

|

8

|

5.2

|

|

Tax Office didn’t return call

|

6

|

3.9

|

|

Lack of face to face contact

|

2

|

1.2

|

|

Total

|

154

|

|

Table 20: Question (b) Tax Related Concerns (A Response Rate of 18.2%)

|

Type of concern

|

Number

|

%

|

|

No concerns

|

26

|

13.3

|

|

Fear of penalties and/or Tax Office insensitivity

|

59

|

30.1

|

|

Ability to pay / time to pay

|

39

|

19.9

|

|

Poor Tax Office service

|

24

|

12.2

|

|

Fear of subsequent victimisation/retribution

|

15

|

7.7

|

|

Uncertainty of knowing what to do

|

11

|

5.6

|

|

Workload

|

8

|

4.1

|

|

System unfairness

|

7

|

3.6

|

|

Other

|

7

|

3.6

|

|

Total

|

196

|

|

Taxpayers who did respond to the tax concern related question (table 20) reported strong negative perceptions about what the ATO might do to non-compliant taxpayers. For example, “I’m worried that the tax office may be too harsh with regards to paying a tax debt and not take personal family problems into account”.

Perceptions of an all-powerful organisation lead taxpayers to report high levels of anxiety about the consequences of their genuine errors or avoidance. Most responses displayed an uncertainty about tax processes and were reported in terms indicative of powerless victims. The threat of substantial penalties compounded by concerns about how they would repay their tax debts was a major issue. The level of ATO service and insensitivity were also reported as concerns. Tax was not a subject of expertise for most taxpayers and their exposure to it was generally on a needs basis, or at tax time. Not knowing what to expect from the ATO or what to do was an underlying driver of some of the taxpayers’ problems with tax. Thirty percent of responses related to insensitivity, penalties and fear of reprisals.

The present study confirmed that understanding non-compliance and risk segmentation is complex. The key variable – “Non-Compliance Intent”, complements the Compliance Model premise that attitudinal and behavioural postures, not only tax related outcomes, determine what explains taxpaying compliance and/or non-compliance. There is a possibility that these levels of intended compliance behaviour predispose the postures identified in the ATO Compliance Model. Additional research would determine whether levels of intended non-compliance were precursors to the ATO Compliance Model’s postures of commitment, capitulation, resistance and disengagement. If intent were a precursor, then intent was mediated by intervening factors such as ATO client service, use of tax agent, knowledge, difficulty of tax system, sociological, psychological, economic and life events resulting in a particular compliance posture. Taxpayers who intended compliance may have risked non-compliance because of perceived more important personal issues and those who intended non-compliance were deterred from doing so because they could not morally justify their intentions.

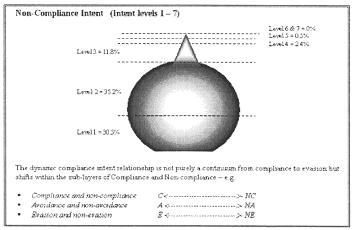

Figure 2 and table 6 show how intent levels were distributed according to taxpayer risk group. The ATO model of compliance and the intent model of non-compliance do not visually share the same distribution of taxpayer behaviours so direct comparisons are not feasible. The reasons are that the ATO Compliance Model does not assign compliant taxpayers to the base level, or indicate upward progression towards the apex of non-compliance. Within the ATO model non-compliance could occur at any point, high or low, of the pyramid. In contrast, the intent model identifies the majority of taxpayers at the second level of non-compliance and the presence of more serious non-compliance to be less evident.

Figure 2. Determinants Non-Compliance Intent Model (N=1319 due to missing data)

The composite scale of intent was produced using the responses from all ten groups, compliant and non-compliant taxpayers combined. Future research needs to identify possible differences between all taxpayer groups. The very low concentration of intent to not comply level 5 may support the premise that the research results for intent are an underestimation of its true relationship with observed behaviour. The low percentage reported at level 5 intent was a gratifying result and the levels reported by youth could be taken as a signal that there was potential for their non-compliance. How these intent levels compared with previous taxpaying typology

was not totally clear. Nevertheless, it was evident that intent was potentially a precursor to future observed behaviour. The expected relationships with observed behaviour did not eventuate and future research might determine why.

The overall relationships between taxpaying behaviour and intent produced mixed results. Results from self reported behaviour provided coherent measures of compliance. The relationships with tax return data were statistically weak. There was no conclusive evidence that Intent and actual behaviour related to either lodgment or tax debt risk. The reason why is still unresolved.

The results indicated that taxpayers had a low level of tax related knowledge and in the main depended on tax agents to assist them. There was a clear transfer of taxpayers’ tax responsibility. Tax agents in Australia are the intermediaries between the ATO and their taxpaying clients. Close to 75% of non-business taxpayers use a tax agent. Agents do act primarily as tax return processors, but their role as principal advisors means that they also assist clients with legal tax minimisation and correct reporting. Their relationship with taxpayer compliance may be viewed as “compliance in form rather than in substance, undermining rather than bolstering enforcement”.[9] Kidder and McEwen call them “Compliance Brokers”.[10] Roth, Scholz and Witte suggested that “if practitioners can be encouraged to foster compliance in their clients, enforcement resources could be concentrated on the most problematic areas”.[11]

Other research has found that there was a higher risk of tax avoidance and evasion where tax professionals have prepared returns.[12] Tomasic and Petony and Nixon recognised the intermediary role that tax practitioners had in the Australian taxation system.[13] Because of their dual responsibility (tax system and client), some taxpayers might see agents as unpaid agents or clients of the ATO.[14] However, agents have to strive to balance the tension between moral values and supporting excesses similar to the tax scheme era of the 80s. Taxpayers perceived moral responsibility as the exclusive domain of tax advisors and they expected tax agents to be fully accountable, produce a 100% correct tax return and provide accurate advice

Seventy five percent of the tax agent sample reported that they often anticipated their clients’ tax problems and 56.5% could anticipate their clients’ future problems. Fifty three percent of tax agents claimed to have dropped clients that did not meet their tax obligations. Seventy point five percent of tax agents reported that their clients didn’t always tell the truth about their tax matters and 90.3% agreed that clients sometimes delayed lodging tax returns so that they could delay paying their tax debts. Forty seven percent of tax agents reported that some clients threaten to go elsewhere if they did not agree with their clients’ instructions about their tax matters.

This tension in the client relationship places tax agents in an unenviable position. They take on the responsibility for conducting an ethical and law-abiding business and at the same time are directed to represent their clients’ best interests. How tax agents influenced final outcomes was not investigated in greater detail. Tax agents and taxpayers mediated how these obligations were met but it is not clear whose involvement took precedence or why. The taxpayer and tax agent relationship will require closer exploration and should remain the focus of relationship management.

Results in table 6 indicate that between 95.5% and 100% of the sample reported that they had no, low or neutral levels of non-compliance intent. This result was surprising given that 49.91% (274 of the 549 lodgment or tax debt non-compliant taxpayers) were identified, according to ATO tax return history as either 100% medium or high risk.

According to the Australian national tax return data system, 3.8% of taxpayers did not meet their lodgment obligations in 1999. The taxpayer sample was according to observed behaviour fairly compliant with regard to lodgment and less compliant in the tax debt area. Low Intent can be taken to reflect taxpayers’ own standards of compliance or non-compliance, compared to those expected of them by the ATO (and the law). It is unclear whether taxpayers truly understood what levels of compliance the tax office expected. If low-level avoidance was not pursued by the ATO then that behaviour would in turn set the tolerance level of what was or was not acceptable taxpayer compliance behaviour.

ATO Client Service was identified as a taxpayer issue. Tax agents and high-risk taxpayers in particular reported lower levels of satisfaction. In an environment of constant structural, processual change and tax reform, this issue will remain a priority. It needs to be noted that this study was conducted pre GST and tax reform. It is anticipated that the levels of satisfaction with ATO client service have since been affected. ATO client service was associated strongly with fairness, tax being difficult, satisfaction and knowledge, using an agent and non-compliance intent. For the Youth and Non-Compliant taxpayer group in particular, if expectations of ATO client service were not met, Non-Compliance Intent increased.

The qualitative data also evidenced dissatisfaction with various key Taxpayers’ Charter areas. Staff insensitivity, time left waiting, quality of responses/advice, access to advice and personnel and fear of reprisals were key risk areas and will require on-going interventions. Proposed interventions need to address very specific client expectations. Taxpayers concerns are for fair and professional service, accurate and timely advice, as well as sensitivity to individual circumstances and greater flexibility with tax debt repayment.

The results indicated that in the main Australian non-business taxpayers were compliant, that there was a propensity to comply and that there was no “tax rage”. Nevertheless, taxpayers did indicate that they tolerated low levels of non-compliance and saw this behaviour as a common method of gaining justice. The factors that impacted taxpayers’ ability to maintain compliance collectively contributed to increased risk behaviour. The data suggest that the ATO should continue its commitment to client service, increase collaborative relationships with tax agents, provide broader tax education programs that include improving tax competence and managing financial affairs and publicise more widely that tax debt repayment options are available. Taxpayers expected to be treated with respect and wanted more assurance and information about what might happen to them should they not meet their compliance obligations or be targeted for an audit. Different strategies would apply for taxpayers who were indisputably non-compliant. Nevertheless, all taxpayers expected to be treated fairly, professionally and with integrity. Taxpayer co-operation is dependent on their tax experiences as well as intent to comply. A focus on younger taxpayers and personalized strategies to engage tax behaviour and build knowledge was seen as contributing to future compliance. Generally, taxpayers would benefit from further ATO assistance and education to better understand and meet their tax compliance obligations.

Relationships between sub-scales of beliefs, attitudes and values were identified, but they did not form any strong relationship with either self-reported behaviour, or ATO-classified compliant or non-compliant risk behaviour. Instead, taxpayers exhibited tax anxiety and held beliefs that tax agents were necessary because tax was difficult. Behaviour was affected by these factors and contributed to non-compliance Intent. The premise that taxpayers “intended” to not comply was not evidenced. If the research had been limited to only the 1% to 2% of taxpayers identified as high-risk, results might have been significantly different. In fact there was little to separate the groups of compliant and non-compliant taxpayers. Future research would benefit from comparing only the two extremes of tax behaviour – compliant and highest risk. Non-compliance or compliance was preceded by factors from personal and environmental circumstances. These factors then impacted taxpayers’ capacity to meet their obligations. Avoidance of dealing with tax problems rather than deliberate tax avoidance were, in the main, a major contributor to actions defined by tax law as tax avoidance. It is not clear whether high-risk taxpayers displayed the same characteristics because the sample size of those with high intent was too small – less than 30.

Despite “Intent” not providing the expected direct relationship to observed taxpaying behaviour (tax return data), it is likely that because the research sample did not include sufficient numbers of the 2% most serious risk non-compliant taxpayers, the current results are an underestimation of the true relationship and limit the research value. Additional insight into whether those taxpayers considered tax evasion a serious offence would provide an alternative means of identifying whether this sample was as non-compliant as the ATO perceived.

Questionnaire items for 4 new scales listed in table 5 and for BBAV (Attitude 1)

|

Scale question items

|

|

Experience of ATO client service

|

|

1. The ATO gives advice without delay

2. The ATO gives me accurate advice

3. ATO staff treat me fairly

4. I am satisfied with the service the ATO provides

5. ATO staff are helpful when dealing with my enquiries about tax

returns

6. In my opinion, the ATO is professional in the way it treats me as a

taxpayer

7. The ATO is fair and considerate with those who get audited

8. 8. The ATO believes nearly everyone pays their shares of taxes

|

|

Intent (Non-compliance)

1. It is everyone’s responsibility to pay the correct amount of tax

(reversed)

2. It is everyone’s responsibility to comply with the tax laws

(reversed)

3. Underpaying tax does not do anyone any harm

4. If I am not quite sure of something on a tax return, I guess the

answer

5. It does not matter if people claim a little more in deductions than they

are entitled to

6. 6. It does not matter if people claim a lot more in deductions than they

are entitled to

|

|

Why it’s necessary to use agents

1. Whenever I use a tax professional, I get good advice

2. Because I find the tax forms to be so unclear, I get someone else to

prepare my tax return

3. Using a tax professional ensures that I claim all my entitlements

4. Using a tax professional guarantees no errors in my tax returns

5. 5. A good reason to use a tax professional is because they get better

service from the ATO than ordinary tax

|

|

Tax is difficult

1. Even tax professionals find it difficult to understand the reasoning

behind tax rulings

2. Changes in the tax law make it difficult to understand which deductions

you can claim

3. 3. In my opinion, tax laws and regulations are always changing, so it is

very difficult to get a tax return exactly right.

|

|

Attitude 1 (tolerance for some tax avoidance)

1. It does not matter if people claim a little more in deductions than they

are entitled to

2. It does not matter if people claim a lot more in deductions than they

are entitled to

3. Because the tax law does not treat everyone equally, a person is

entitled to “even things up” by not declaring all

information

correctly

4. When the amount of avoidance is small the ATO should let it go

|

TRDB and NTS Tax return database items for 1999 and 2000 income years

|

• Marital status

• Tax agent user code

• Total income amount

• Taxable income amount

• Salary wages amount

• Work related deductions amount

• Other deduction amount

• Medicare levy in tax amount

• Net income amount

• Net tax amount

• Assessment issued amount

• Balance payable refundable amount (refund or tax debt)

• TID amount (tax installments)

• Low income rebate amount

• Income level code (as at last lodgment)

|

• Taxable salary wages amount

• CSA code (Child support/ maintenance)

• Total other business income amount

• Superannuation contribution amount

• Non-employer super contribution amount

• Unemployment / benefits amount

• Total ETP amount (Employment termination payment)

• Total rebates amount

• Dividend franked amount

• Allowance or benefit amount

• Aged pension amount

• Total expenses amount

• Net rental amount

• Total business income amount

• NTS lodgment history – return and default (1995-2000)

|

[∗] The study was conducted by the ATO 2000/2001 under the guidance of Assistant Commissioners Brian Leonard and subsequently Chris Mobbs. A summary version of this article was presented at the ATAX Conference, 2002. This article was published with the permission of the ATO and the conclusions reached by the authors are not necessarily the policy views of the ATO.

[∗∗] PhD candidate, Department of Psychology, University of Adelaide

[∗∗∗] PhD candidate, Department of Psychology, University of Adelaide.

[∗∗∗∗] Professor, Department of Psychology, University of Melbourne. All inquiries should be directed to: ajwe@unimelb.edu.au.

[1] Beliefs, behaviours, attitudes and values formed the basis of ATO’s research.

[2] The Integrated Compliance Study (“ICS”) was an ATO study of compliance risk probabilities for non-business taxpayers.

[3] This classification is due to Steve Baldwin.

[4] J Alm, B Jackson and M McKee, “Alternative Government Approaches for Increasing Tax Compliance” (1992) 90 TNT 260-42; and SB Long and JA Swingen, “Taxpayer Compliance: Setting New Agendas for Research” (1991) 25(3) Law & Society Review 645.

[5] D McBarnett, “The Construction of Compliance and the Challenge for Control: the Limits of Non-Compliance Research” in J Slemrod (ed), Why People Pay Taxes (1992)339.

[6] AJ Wearing and BM Headey, “The Would-be Tax Evader: a Profile” (1997) 13 Australian Tax Forum 3.

[7] YD Song and TE Yarbrough, “Tax Ethics and Taxpayer Attitudes: a Survey” [1978] Public Administration Review 442.

[8] D Yankelovich, “A Crisis of Moral Legitimacy” (Fall 1974) Dissent 0526.

[9] McBarnet, above n 5.

[10] R Kidder and C McEwen. “Taxpaying Behaviour in Social Context: A Tentative Typology of Tax Compliance and Non Compliance” in JA Roth, JT Scholz and AD Witte (eds). Taxpayer Compliance (Vol 2, 1989) 50.

[11] JA Roth, JT Scholz and AD Witte. Taxpayer Compliance (Vol 1. 1990) 178.

[12] IG Wallschutzky, “Possible Causes for Tax Evasion” (1984) 5 Journal of Economic Psychology 371.

[13] R Tomasic and B Petony, “Taxation Law Compliance and the Role of Professional Tax Advisers” (paper presented at a tax compliance workshop held at the Taxation Business and Investment Law Research Centre and KPMG Peat Marwick Hungerfords. University of NSW; August 1989); and T Nixon, “Current Problems in Tax Decision Making. Do Tax Agents Assist Voluntary Compliance?” (1998 unpublished).

[14] B Jackson and V Milleron. “Tax Preparers: Government Agents or Client Advocates?” (May 1989) 167 Journal of Accountancy 76, 82.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/JlATax/2003/5.html