Journal of Australian Taxation

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Journal of Australian Taxation |

|

TAXATION AGENTS AND TAXPAYER COMPLIANCE

By Pauline Niemirowski[*] and Alexander J Wearing[∗∗]

For over forty years an important and enduring applied taxation research question has been one of finding effective interventions to improve compliance. Attention is typically focused on taxpayers who take responsibility for preparing their own tax returns. In this second article drawn from the Australian Determinants of Australian Taxpayer Compliance study,[∗∗∗] the role of the tax agent is investigated. A sample of compliant and non-compliant taxpayers was selected according to their historical tax return profiles and risk probability and 839 responded. A group of 62 tax agents also responded. A questionnaire encompassing behaviours and values, beliefs and attitudes, competency, fairness, tax knowledge, satisfaction and lifestyle was administered by mail. The study identified several factors related to compliance, the role of tax agents, and relationship between taxpayers and tax agents. These factors included taxpayers’ experience of ATO client service, their perceptions that tax was difficult and the necessity to use a tax agent to complete tax returns correctly. The results indicated that tax agents served three key roles: providing tax advice, correct tax return preparation and lodgment, and risk management for tax minimization. An implication of these results is that the ATO should treat tax agents as an increasingly important part of the compliance process.

The workload and technological change involved in processing an ever increasing number of taxation returns led the Australian Taxation Office (“ATO”) to introduce self-assessment in 1986/87, with the consequence that taxpayers, as self-preparers, would become increasingly responsible for the correctness of their own tax returns.[1] This strategy resulted in a new focus on client service, and a more supportive treatment of salary and wage earners because the ATO in Australia recognised an additional responsibility to assist taxpayers meet their tax obligations if the new system was going to work as intended.[2] The ATO also realised the limitations of detection and negative sanctions. Tax administrators adopted the view that responsiveness (responsive service) and fairness (procedural fairness) would increase compliance and facilitate compliant self-preparation.[3] The ATO Taxpayers’ Charter and development of the ATO Compliance Model specifically addressed these two issues.[4]

In summary, the ATO has not only accepted a responsibility to be an initial arbiter of the law, but it now believes it must be seen to facilitate this process of compliance, and demonstrate empathy with taxpayers’ expectations. Flexibility in individual cases, and improved communication about the tax system, are an essential part of this undertaking. Moreover, not only must there be a motivation to comply on the part of the taxpayers, but the task of compliance must be straightforward enough to be easy to complete without error. Accordingly, in Australia, current tax reform aims for simplicity and cost effectiveness.[5]

This goal may not be easy to reach. For many taxpayers, their most frequent contact with the ATO is through use of documentation (eg Tax Pack). Unfortunately, not all taxpayers find tax documents easy to understand, despite attempts to promote accessibility via a process of simplification.[6] Generally, however, these simplification attempts have not been widely perceived as successful. For many taxpayers, documentation sent from the tax department is unrewarding and non-engaging. This could be due to the complexity of the process and level of language or the time and costs involved in processing. The avoidance reaction could also be due to fear of making errors, thus drawing the attention of the ATO and receiving penalties.[7]

Nevertheless, despite any difficulties that a taxpayer may have, there is an implicit assumption on the part of the ATO that taxpayers are rational to the extent that, with the aid of TaxPack, they are able to handle the task of preparing their tax returns. On this assumption of rationality, any mistakes may be seen as not due to incompetence, but to a lack of commitment to lodging a correct tax return. Indeed taxpayers may, if they are rational financial maximizers, be taking advantage of the opportunity of self-assessment to engage in what some may call unethical tax minimization.

The present study drew on data collected in the course of carrying out the ATO’s Determinants of Australian Tax Compliance study.[8] The Determinants study involved preparing a survey instrument that was circulated to a wide range of taxpayers, tax officers and tax agents. The full study addressed psychological, economic, compliance, social and individual aspects of the taxpayer’s environment in relation to tax. The current article focuses on taxpayers and tax agents and the relationship between them. The findings of this study confirmed that taxpayers’ compliance behaviour was in the main similar to tax agents with only a few significant differences. In part, taxpaying behaviour related to beliefs, attitudes and values, ATO client service, sense of financial competence, difficulty in meeting tax obligations, perceptions about the necessity to use tax agents, tax knowledge, and who was responsible for compliance when tax returns lodged were prepared and lodged by tax agents. This article addresses five specific issues; why taxpayers may or may not self prepare and whether they can be regarded as rational minimisers, the Baldwin Tax process Model, ATO client relationships, why taxpayers use tax agents, and the differences between taxpayers and tax agents. Of particular interest was the choice of self preparation or tax agent preparation, perceptions of a need to engage a tax agent, and the consequences of tax lodgment in relation to compliance behaviour and any difficulties in meeting tax obligations.

Even though it may be assumed by the ATO that the average taxpayer, armed with a copy of Tax Pack, should be able to complete their own tax returns, the task of completing a correct tax return may not be a simple one. There are many antecedents of tax compliance, ranging from events that occur shortly before lodgment, to events occurring in the less recent past.

Antecedents of compliance may include maintaining appropriate records and receipts for tax-deductible goods/services. This may involve storage of financial records in a safe location. Acquisition of detailed knowledge is also required about allowable expenses. Year-to-year, the personal fund of information about expenses and allowances will change, according to regulatory variations within the taxation system. Successful yearly lodgment may require an update of this personal “fund of knowledge” with new data. Most tax lodgment skills are based on previous successful “on time” completion of tax returns. On time lodgment requires that taxpayers know the appropriate submission dates and deadlines for completion. Knowledge of penalties and ATO sanctions may act as an incentive for on time completion.

For many taxpayers, successful lodgment involves drawing on a repertoire of skills that are neither well learned, nor strongly established. The infrequent (although regular) yearly cycle of tax lodgment means that even amongst compliant taxpayers the repertoire of skills is not rehearsed frequently or routinely. The difficulties involved in the preparation of a tax return may often involve a range of related maladaptive behaviours, including postponement, procrastination, prevarication, denial, delay, and hold-ups.

Furthermore, “lodgment” is not a single activity but a complex task with multiple related elements.[9] Several inter-related financial management skills are required. These include, but are not limited to, numeracy, literacy, abstract thinking, monetary formulations and reasoning. Successful lodgment requires each of these skills. Moreover, achieving lodgment requires completion in a specific sequence.

For some taxpayers however, even basic numeracy skills (addition, subtraction, multiplication and division) may prove too demanding in everyday life. In the potentially challenging context of tax lodgment some taxpayers could perceive the task as overwhelming, and avoid it completely. Hence the relative complexity of tax lodgment demands financial management skills that require continuing rehearsal throughout the tax year, a rehearsal that often does not occur.

Preliminary descriptive analyses on compliant and non-compliant taxpayers identified a pattern of aversive tax behaviour based on perceptions of taxpayers’ own tax competence, need for a tax agent and also experience of ATO client service. Steve Baldwin[10] developed this schema, and the authors refined and expanded it into a working model titled the Baldwin Tax Process Model (see results section).

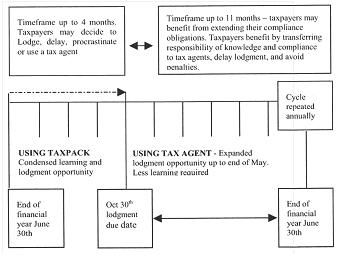

Figure 1: The Baldwin Tax Process Model (“BTP Model”)

In any one financial year, taxpayers have the option to self prepare within a fixed four month lodgment period (proximal). This requires them to undertake a sequence of behaviours to accomplish successful lodgment and compliance – collecting all relevant records, forms, receipts, carefully interpret instructions, fill out the forms, check the forms, and lodge the forms. Alternatively, taxpayers may choose to lodge their tax returns through a tax agent and extend their lodgment period (distal) as well as transfer their compliance responsibilities.

TAX RETURN LODGEMENT CYCLE

Antecedents may also include aspects of the individual’s personal experiences of other public sector services. For example each taxpayer has an accumulated personal history with various public sector organisations (eg welfare, social security, and employment). Although there is no obvious organisational connection between these different public sector agencies, individual taxpayers may perceive them as connected. Moreover, personal experience in one public sector organisation may be (inappropriately) generalised into another organisation. According to their personal history, the collective set of imported beliefs, attitudes, knowledge and values may be negative or positive. Whether these dispositions toward public sector organisations are positive or negative may determine many of the subsequent responses of individual citizens toward their taxpaying. Many of these inter-linked beliefs, attitudes, knowledge and values will directly affect their taxpaying compliance behaviour. As more public sector organisations share client knowledge to detect and penalise non-compliance, taxpayers will report that the whole public sector is typically helpful and caring or distrustful and punitive.

This analysis indicates that the successful completion of a tax return is based on complex patterns of behaviour that may date back at least eleven months before the next tax lodgment. Moreover, if a taxpayer has an incomplete tax submission history (ie a pattern of yearly non-lodgment) the important behavioural repertoire may date back several years. Hence, to achieve a shift of taxpaying behaviour from non-compliance to compliance, ingrained beliefs and practices may need to be modified. These changes may include acquisition of new financial management skills, eg keeping weekly records of work related expenditure or a logbook.

Successful tax lodgment may demand permanent change on the part of the taxpayer. At any one time, the most accurate predictor of future lodgment is previous lodgment behaviour.[11] The quality of client service relationships between the taxpayer and taxation office staff may therefore be crucial to promote and maintain change in behaviour. Where the taxpayer has an incomplete, uneven or patchy history with the taxation office, development of a new association with a tax professional/agent may promote an improved relationship with the government department.

The complexity of compliance and the need for a continuing relationship with an advisor, either from the ATO or elsewhere, may, in the mind of the taxpayer, make a tax agent necessary. For many compliant taxpayers, successful lodgment is assisted directly by the personal relationship already developed with a tax agent. Some of the most powerful antecedents of “correct lodgment” (ie on time, fully completed) are based on advice from the tax agent, which will be accustomed to shape compliance behaviour. Such behavioural “shaping” may include requests for more specific fiscal details (eg receipts, dockets, bills, proof of payment or purchases). This shaping process may also involve more specific advice to exclude (eg advice not to submit claims that are ineligible or inappropriate) or include (eg advice to submit a claim that will qualify as a deduction) specific elements of the tax submission. The tax agent may play a significant role in ensuring compliance.

A range of positive and negative consequences may flow from tax lodgment. Some of these consequences increase the probability of subsequent compliance behaviour. Other consequences decrease the probability of subsequent compliance. Both reward and punishment are used in the current taxation system. Taxpayers may perceive other types of intrinsic rewards and punishment, in addition to the tax related benefits or entitlements resulting from compliant behaviour. For example, no further action by the taxation office could be viewed as a reward, and a request for substantiation of future claims as a punishment.

All of these factors associated with reward and punishment might lead a taxpayer to seek expert advice as a means for ensuring positive consequences for the taxpayer. More particularly, the tax agent may be expected to be able to assist the taxpayer to reduce the uncertainty as to whether the outcome will be rewarding or aversive.

The aims of this study are fivefold. First, to see why taxpayers may or may not decide to self-prepare, and whether there is support for a rational maximizer model of tax compliance. Second, whether or not there is support for the BTP Model[12] (Figure 1). Third, to describe how taxpayers see the ATO and consider how that perception might affect their decision to self-prepare or use a tax agent. Fourth, to see why taxpayers use tax agents, and not simply self prepare, using ATO services to answer their queries. One might expect that because the system was designed for use by self-preparers, and tax agents are expensive, that most taxpayers would self-prepare. In fact this is not so, as according to the ATO’s IC study approximately three taxpayers in four use a tax agent.[13] Fifth, to determine whether there are any important differences between the views of taxpayers and the views of tax agents.

The original study was called the Determinants of Australian Taxpayer Compliance to reflect the research interest in the determinants of tax compliance or non-compliance. Tax agents received their questionnaires ahead of taxpayers because it was necessary to schedule distribution during a period least likely to impact on their workloads. All taxpayers received their questionnaires several weeks before their tax lodgment was due (31 October) in order to promote both awareness of their obligations and enhance response rates. A second copy of the questionnaire was sent out with a reminder letter about three weeks later, and a final reminder letter was sent a further two weeks later.

As indicated above, the data for this study was drawn from the Determinants of Australian Taxpayers Compliance study. The whole sample consisted of compliant taxpayers, non-compliant taxpayers, tax office staff, tax agents and younger taxpayers. The selection of the taxpayers was based on “reported” ATO evidence of tax compliance or non-compliance. The focus of the present study was on tax agents, compliant and non-compliant taxpayers only.

The authors developed the questionnaire in collaboration with key ATO officials who played a significant role in the drafting of tax specific questions. The questionnaire consisted of 94 behaviour, beliefs, attitudes and values (“BBAV”) questions in total, 81 BBAV questions for tax agents, and 93 for all other taxpayers. The BBAV responses were measured using a 7 point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree, plus 8 for don’t know and 9 for not applicable. The tax knowledge quiz required either a yes, no or don’t know response.

Significant steps were undertaken to guarantee the privacy and confidentiality of respondents. This included multiple de-identification and coding, invitation to participate letters, advance information that individual tax return data would be accessed and matched to survey responses, that involvement was voluntary and no ATO initiated action would result. All survey responses were received by the end of January 2001. During the three month period of survey mailouts and collection, a 24-hour hotline number was available for taxpayer enquiries. Generally, respondents’ main concern was privacy or possible ATO follow up action if they participated.

All potential taxpayer respondents were compliant in 1995. This baseline taxpayer tax compliance behaviour provided the opportunity to compare groups and identify any differences in subsequent years. For the 1995 tax financial year approximately 6,000,000 Australian non-business taxpayers were potentially eligible for selection. The research design targeted seven specific tax compliance behaviours. To be eligible for selection, only taxpayers aged 21 to 65 who were deemed compliant in 1995, and were Australian residents with no bankruptcy, final return not necessary, or deceased indicators were included. The taxpayers were selected from this final pool.

The tax risks used in the study were non-lodgment, non-payment of debt, history of audits with risk probabilities identified as either medium, high and a combination of at least two non-compliant risks. 2,800 compliant and non-compliant taxpayers, based on reported taxpaying behaviour, were selected at random to receive invitations to participate in the survey.

Selection of the taxpayers was based on “reported” ATO evidence of tax compliance or non-compliance. These groups respectively exemplified either reported tax compliance or non-compliance, where tax compliance was “ATO identified and recorded” tax compliance. Compliant taxpayers were behavioural exemplars (no risk or low risk) and also the theoretical control group against which all other groups were compared. Tax compliance was defined as “reporting all income and paying all taxes in accordance with the applicable laws, regulations, and court decisions”.[14] Non-compliance in this study was any tax lodgment or debt behaviour that did not adhere to the definition of tax compliance. “Tax evasion methods simply ignore or break the law, tax avoidance devices use the methods of law to neutralise its impact”.[15]

The tax agent sample was selected as follows. The final data set of 2,800 taxpayer survey recipients included current tax agent details. A sample of 200 tax agents was randomly drawn from the pool of tax agents who represented the 2,800 taxpayers.

Draft survey questionnaires were developed and piloted during 1998 and 1999. The topics included tax related behaviours, beliefs attitudes and values, client experiences with the ATO, individual demographics, lifestyle factors, perceptions of the seriousness of laws, levels of satisfaction with various institutions and aspects of life, and knowledge about specific taxes and their fairness. The context of the survey reflected the philosophy and principles of the ATO Compliance Model and ATO Taxpayers’ Charter. Demographic details such as gender, age, income, education level, home ownership and occupation were collected. Measures of satisfaction, seriousness of laws, knowledge of taxes, a tax quiz and fairness of taxes were included to construct a holistic view of the taxpayer environment.

The response rate for taxpayers was 34.6% and 31% for tax agents. Because of the nature of the survey, it was not possible to assume with confidence that the responses obtained were random samples of the randomly selected target populations. Accordingly, an examination of the “representativeness” of the responses was carried out on the demographic and tax characteristics of the responding taxpayers in each group. The records of responding taxpayers were compared with those for the total mail out sample for statistically significant differences in sample and whole population profiles. The response data appeared sufficiently representative to confirm confidence in the sample. It may be noted that 86% of the respondents used tax agents as compared with about 75% vis-a-vis the individual non-business taxpayer population.

As indicated above, the aims of this study are fivefold. First, to see why taxpayers may or may not self-prepare, and whether there is support for a rational maximizer model of tax compliance. Second, to see whether or not there is support for the BTP Model. Third, to describe how taxpayers see the ATO. Fourth, to see why taxpayers use tax agents, and not simply self prepare. Fifth, to determine whether there are any important differences between the views of taxpayers and the views of tax agents.

Preliminary descriptive analyses identified a pattern of significant taxpayer behaviours and perceptions that supported a tax process model. That is, non-compliant taxpayers were significantly different to compliant taxpayers. Non-compliant taxpayers exhibited certain behaviours and beliefs, attitudes and values that could explain their non-compliant behaviour. All significant items are tabled in table 1 below.

Table 1: Items Showing 24 Significant Differences Between Compliant & Non-compliant Taxpayer Responses

(Means 1-7)1= strongly disagree, 7= strongly agree * indicates reverse direction of response

|

Item

|

Items supporting the Baldwin Tax Process Model Non-compliant taxpayer

responses

|

Non-comp Mean/SD

|

Comp Mean/SD

|

|

Q2

|

In the past when I have needed help with tax matters I have gone first to

my friends

|

2.85/1.81

|

3.14/1.93

|

|

Q13

|

Before my tax return is prepared, I have readily available all the tax

information and records I need

|

5.50/1.53

|

5.79/1.27

|

|

Q16*

|

It takes too much time to find the information necessary for my tax return

4.11/1.74

|

|

3.60/1.63

|

|

Q19

|

Tax returns should be lodged on time every year

|

5.36/1.48

|

5.60/1.40

|

|

Q22

|

Compared to business, wage earners pay a greater share of their income

tax

|

5.05/1.83

|

5.44/1.52

|

|

Q25

|

All long-term tax debt should be pursued by the ATO

|

5.38/1.38

|

5.68/1.25

|

|

Q26

|

Unpaid taxes reduce the effectiveness of the Federal Government’s

operations

|

5.15/1.57

|

5.38/1.35

|

|

Q29

|

Underpaying taxes does not do anyone any harm

|

2.45/1.39

|

2.22/1.13

|

|

Q30

|

Because it takes so much time, I put off completing my tax return

|

3.77/1.90

|

3.26/1.83

|

|

Q31

|

Because it is uninteresting, I put off completing my tax return

|

3.57/1.78

|

3.29/1.78

|

|

Q32

|

Even if I do not expect a refund, I lodge my tax return as soon as

possible

|

4.48/1.80

|

4.87/1.77

|

|

Q34

|

I put off completing my tax return because I do not like dealing with

government agencies

|

3.16/1.65

|

2.86/1.48

|

|

Q35

|

When I do not expect a refund, I put off completing my tax return

|

2.94/1.58

|

2.69/1.45

|

|

Q47

|

It doe not matter if people claim a lot more in deductions than they are

entitled to

|

2.14/1.30

|

1.92/1.09

|

|

Q50

|

Tax reform would help the ATO do a better job in explaining how the tax

system works

|

4.59/1.5

|

4.82/1.26

|

|

Q55*

|

The ATO is fair and considerate with those who get audited

|

3.89/1.25

|

4.08/0.98

|

|

Q62

|

Even tax professionals find it difficult to understand the reasoning behind

tax rulings

|

4.84/1.36

|

4.62/1.31

|

|

Q67

|

In the past I have not always lodged a tax return, even when it was

necessary

|

2.08/1.46

|

1.75/1.23

|

|

Q72

|

Paying taxes is necessary so that the Federal Government can operate

effectively

|

5.49/1.41

|

5.76/1.13

|

|

Q74

|

It is everyone’s responsibility to comply with the tax laws

|

5.86/1.09

|

6.03/0.89

|

|

Q79*

|

It is better to have many taxes that are low than a few taxes that are

high

|

4.23/1.51

|

3.90/1.45

|

|

Q86

|

If I forgot to lodge my tax return one year, and did not get caught, I

might not lodge the following year because I would be too worried

about how the

ATO would deal with me

|

3.15/1.78

|

2.78/1.53

|

|

Q89

|

In Australia there is a widespread belief that that smart people can avoid

paying the correct amount of tax

|

5.34/1.49

|

5.58/1.26

|

|

Q92*

|

If the ATO set up a “fraud hotline”, I would use it to report

people who seemed to evade their tax obligations

|

3.70/1.70

|

4.02/1.62

|

Responses for both compliant and non-compliant taxpayers were generally in the same direction, but there were twenty four significant differences. A significant proportion of non-compliant taxpayers were less organized or engaged with the tax process, found tax returns more difficult and more time consuming, and were more motivated by tax refunds. Taxpayers would not report anyone who seemed to evade taxes but agreed that the ATO should pursue all outstanding tax debts and that taxes were necessary for effective government. Overall, the results indicated that non-compliant taxpayers were less tax competent. The lack of tax competence could explain their general lack of organisation and why they procrastinated or avoided their lodgment obligations, and were more likely to depend on the expertise of a tax agent. Nevertheless, both non-compliant taxpayers and compliant taxpayers transferred their responsibilities to tax agents because of the complexity and time involved with tax.

Table 2: Response Rates for Taxpayers and Tax Agents

|

|

Responses

|

Sent

|

Response rate

|

Representativeness

|

|

Taxpayers

|

839

|

2800

|

34.6%

|

Response rates were satisfactory and representativeness of the taxpayer

sample was confirmed. Ninety seven percent of the 839 responding

taxpayers used

tax agents, and only 3% were self-preparers.

|

|

Tax agents

|

62

|

200

|

31%

|

NA

|

The results and tables 3 to 9 are presented according to the five research aims

Table 3: Reasons Why Taxpayers May or May Not Self Prepare (Aim la) Attitudes, Beliefs, Behaviour & Values Relating to Tax Returns and Taxpayer Competence to Understand Tax Law

Likert scale 1 to 7. 1=strongly disagree; 7=strongly agree

|

Item number

|

Mean

|

% Agree

|

% Disagree

|

Item

|

|

|

|

|

|

Knowledge, confidence and competence

|

|

13

|

5.60

|

84

|

11

|

Before my tax return is prepared, I have readily available all the tax

information and records I need

|

|

81

|

5.08

|

60

|

3

|

Tax laws and regulations sometimes seem to contradict one another

|

|

18

|

4.48

|

51

|

28

|

I have found tax returns too difficult to do

|

|

16

|

3.93

|

38

|

40

|

It takes too much time to find the information necessary for my tax

return

|

|

17

|

2.92

|

14

|

63

|

In my opinion tax return forms are easy to complete

|

|

59

|

2.63

|

16

|

72

|

The taxation law is straightforward and clear

|

|

12

|

2.56

|

16

|

75

|

I know the tax laws well enough to prepare my own tax return

|

|

|

|

|

|

Understanding of tax law and ethics

|

|

27

|

6.14

|

93

|

2

|

It is ethical to claim for everything you are entitled to

|

|

28

|

6.04

|

93

|

3

|

It is everyone’s responsibility to pay the correct amount of

tax

|

|

|

|

|

|

Engagement

|

|

30

|

3.59

|

35

|

50

|

Because it takes so much time, I put off completing my tax return

|

|

31

|

3.48

|

30

|

51

|

Because it is uninteresting, I put off completing my tax return

|

|

|

|

|

|

Motivation to lodge a tax returns

|

|

32

|

4.62

|

57

|

43

|

Even if I do not expect a refund, I lodge my tax return as soon as

possible

|

|

33

|

3.93

|

36

|

39

|

If I think the refund will be more than $500, I complete my tax return as

soon as possible

|

|

35

|

2.85

|

14

|

86

|

When I do not expect a refund, I put off completing my tax return

|

|

|

|

|

|

Knowledge maintenance & competency

|

|

63

|

5.18

|

69

|

10

|

Changes in the tax law make it difficult to understand which deductions you

can claim

|

|

64

|

5.12

|

66

|

12

|

In my opinion, tax laws and regulations are always changing, so it is very

difficult to get a tax return exactly right

|

|

75

|

4.73

|

57

|

22

|

It is difficult to complete a tax return 100% accurate tax return

|

|

37

|

4.59

|

57

|

43

|

Filling out a tax return on my own makes me feel worried

|

|

62

|

4.76

|

51

|

11

|

Even tax professionals find it difficult to understand the reasoning behind

tax rulings

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fear of detection

|

|

70

|

4.97

|

58

|

10

|

There is a strong chance that a taxpayer will get audited by the ATO

|

|

51

|

4.84

|

63

|

16

|

I prepare my own tax return correctly because there is a strong chance I

would get caught if I didn’t

|

From Table 3, one can see why the respondents are reluctant to self-prepare, and are concerned about their mistakes being detected. Although it can be time consuming, there was no problem in getting the information ready, but the tax forms were difficult to fill in, and not easy to complete. Tax law is too difficult for many taxpayers. A majority (75%) agrees that they do not know the tax laws well enough to prepare their own tax returns. They complained that tax laws are always changing, and sometimes contradict one another. In short, it is difficult to get a tax return 100% correct; mistakes seem both inevitable and highly likely to be detected. This view was not confined to taxpayers; tax agents held the same opinion. Forty three percent of taxpayers indicated that refunds were a possible incentive to lodge tax returns sooner. Carroll[17] supported this finding. He reported that taxpayers used a “refund frame” when dealing with tax returns. Taxpayers considered the total tax paid, the current refund or debt amounts, and also compared these to the previous year’s amount.

Table 4: Rational Maximizer (Aim 1b) Selected Taxpayer Attitudes – the Rational Tax Minimizer Model

|

Item number

|

Mean

|

% Agree

|

Item

|

|

45

|

4.58

|

49

|

Even if they do not have all the receipts and records, most people claim

all their entitlements

|

|

46

|

2.83

|

12

|

It does not matter if people claim a little more in deductions than they

are entitled to

|

|

47

|

2.06

|

4

|

It does not matter if people claim a lot more in deductions than they are

entitled to

|

|

49

|

4.70

|

60

|

In Australia it is expected that everyone will only claim for deductions

that they are entitled to

|

|

52

|

2.44

|

8

|

Because the tax law does not treat everyone equally, a person is entitled

to even things up by not declaring all information correctly

|

|

65

|

4.64

|

23

|

Amounts of over claiming I might have done are insignificant compared to

the tax avoidance by wealthy people

|

For those concerned that a rational maximizer would be an ardent tax minimizer, only 49% thought that most people claimed for all entitlements even if they did not keep relevant records. The view was strongly held that although it is ethical to claim one’s entitlements, people should pay the correct amount of tax. Nevertheless, between 4 and 12% of taxpayers did consider avoidance to be not serious, and 23% rationalized any possible avoidance behaviour by saying it was insignificant when compared to what the wealthy did. Whilst taxpayers do not report personal overt tax minimization behaviours, it could be that they transfer the task of legal tax minimization to their tax agents.

Further results provided a moderate level of support for Aim 2, the BTP Model. Getting information together was not regarded as a serious problem for 40% of respondents, but there was no indication

of competence, ie whether taxpayers collected or organized it (Table 3). A 1997 ATO Media release reported that many taxpayers kept “inadequate” records, failed to declare all income and claimed incorrect deductions.[18] Considering also the tax maximizer, finding the task uninteresting affected completion for only 30% of taxpayers, and 35% of respondents procrastinated. Positive incentives such as large refunds were reported as having no effect for 36%, and the absence of incentives seemed to make no difference for 43%. Negative incentives, however, such as the possibility of punishment had a significant effect on 58 to 63% of the taxpayers’ evaluation of their situation (Table 3).

Table 5: ATO Client Relationships (Aim 3). Attitudes, Beliefs, Behaviour & Values Relating to Perceptions About Tax & the ATO

Likert scale 1 to 7. 1=strongly disagree; 7=strongly agree

|

Item number

|

Mean

|

% Agree

|

% Disagree

|

Item

|

|

39

|

4.39

|

32

|

11

|

ATO staff treat me fairly

|

|

43

|

4.38

|

32

|

11

|

ATO staff are helpful with my enquiries about tax returns

|

|

44

|

4.36

|

35

|

14

|

In my opinion, the ATO is professional in the way it treats me as a

taxpayer

|

|

11

|

4.30

|

32

|

14

|

The ATO gives me accurate advice

|

|

40

|

4.30

|

38

|

18

|

I am satisfied with the service the ATO provides

|

|

5

|

4.05

|

27

|

21

|

The ATO gives me advice without delay

|

|

55

|

3.85

|

17

|

18

|

The ATO is fair and considerate with those who get audited

|

|

3

|

3.82

|

33

|

42

|

I avoid asking the ATO for advice about my tax return

|

|

1

|

2.99

|

23

|

61

|

I have gone to the ATO first for help with tax matters

|

According to Table 5, the respondents feel positively about the ATO, but not strongly so. The ATO is seen as providing prompt and accurate advice, being fair, professional, and helpful. In general respondents pronounced themselves satisfied. All these views, however, were lukewarm. One reason for this may be that many taxpayers do not approach or seek advice from the ATO, are ignorant of its services, and therefore do not have either positive or negative views.

Table 6: Tax Agent Attitudes, Beliefs, Behaviour & Values Relating to the ATO Ranked According to Mean

Likert scale 1 to 7. 1= strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree

|

Item

|

Mean

|

% Agree

|

% Disagree

|

Item

|

|

56

|

5.11

|

79

|

18

|

Nowadays the ATO is making a big effort to try to help taxpayers understand

laws and regulations

|

|

51

|

4.35

|

55

|

34

|

I prepare my own tax return correctly because there is a strong chance I

would get caught if I didn’t

|

|

55

|

4.13

|

40

|

32

|

The ATO is fair and considerate with those who get audited

|

|

40

|

4.00

|

48

|

42

|

I am satisfied with the service the ATO provides

|

|

70

|

3.98

|

47

|

39

|

There is a strong chance that a taxpayer will get audited by the ATO

|

|

53

|

3.31

|

27

|

57

|

When the amount of avoidance is small the ATO should let it go

|

There were, however, some beliefs that were strongly held about the ATO. As indicated in table 6, 55% of tax agents reported that any mistakes in a tax returns were likely to be detected, and 47% reported that there was a strong chance that taxpayers will be audited, a rational maximizer attitude. In fact, enforcing the law was seen as a proper function of the ATO, with 57% of the tax agent respondents disagreeing that the ATO should let even a small amount of avoidance go. Perhaps because of its assessment function, taxpayers did not see the ATO as the first place to go for help. Taxpayers’ lack of skills and tax knowledge may also contribute to their reluctance to contact the ATO. Another reason could be that taxpayers prefer a one-stop remedy and the tax agent saves them contacting two resources. Nevertheless, the views of the respondents about the ATO seem positive, so on the face of it, there would seem to be little need for tax agents.

Table 7: Why Taxpayers Use a Tax Agent (Aim 4). Attitudes, Beliefs, Behaviour & Values Relating to Taxpayers Perceptions of Why They Use a Tax Professional – Ranked According to Mean

Likert scale 1 to 7. 1= strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree

|

Item

|

Mean

|

% Agree

|

% Disagree

|

Item

|

|

6

|

5.93

|

87

|

9

|

Because I do not want to make any mistakes I use a tax professional to

prepare my tax return

|

|

90

|

5.78

|

87

|

13

|

It is the responsibility of tax professionals to ensure that their clients

pay the correct amount of tax

|

|

9

|

5.77

|

86

|

7

|

Using a tax professional ensures that I claim all my entitlements

|

|

4

|

5.52

|

81

|

10

|

Whenever I use a tax professional I get good advice

|

|

7

|

5.38

|

75

|

17

|

Because I do not understand all the questions I use a tax professional to

prepare my tax return

|

|

10

|

5.09

|

71

|

9

|

Using a tax professional guarantees no errors in my tax returns

|

|

8

|

4.86

|

61

|

24

|

Because I find the tax forms to be so unclear, I get someone else to

prepare my tax return

|

|

42

|

4.74

|

53

|

16

|

A good reason to use a tax professional is because they get better service

from the ATO than ordinary taxpayers

|

An examination of table 7 suggested that the respondents found the boundary between the lawful and unlawful difficult to draw. They want to pay no more tax than they must, but want to stay within the law and prefer to remain less visible. They are happy to not only transfer lodgment to tax agents, thereby extending the time frame, and use their (or their tax agent’s) knowledge to minimize their tax, but they also unconsciously or deliberately attempt to transfer any related concerns of responsibility and accuracy about claiming all their entitlements. Taxpayers who use tax agents transfer the responsibility of correct lodgment and risk of detection to paid advisers.

It is not surprising that taxpayers turn to tax agents for assistance. They are seen to give good advice and ensure the avoidance of mistakes. Where people find the forms unclear, are not sure what entitlements to claim, and wish to ensure that there are no detectable errors, then a tax agent can help. Tax agents are also seen as getting better service from the ATO. Even so, tax agents can still find it difficult to complete a tax return. This confidence that a tax agent can complete a tax return correctly is very high. Compared to the less enthusiastic endorsement of the ATO service, tax agents are seen as able to manage the vagaries of the Tax Act.

Tax agents act as taxpayers’ advisors, risk takers and risk minimizers and as mediators and knowledge gatekeepers for the ATO. The relationship they have with taxpayer clients is based on lodging a correct tax return while achieving maximum entitlements. Whether this is to the ATO’s or clients’ advantage is not always clear. Tax agents’ relationship with clients is based on a paid service and expectation of minimum risk. A majority of tax agents reported that they were able to anticipate client tax problems and future tax problems. Their clients sometimes delayed lodging, and were not always truthful (Table 8). Clients who did not meet tax obligations were dropped by only half of the tax agents, and almost half experienced client threats to go elsewhere if they disagreed with client instructions.

Table 8: Taxpayer and Tax Agent Relationships

|

Item label

|

Tax client Relationships

|

% Yes

|

% No

|

|

E

|

Clients sometimes delay lodging

|

90

|

8

|

|

O

|

Anticipate client tax problems

|

76

|

16

|

|

C

|

Clients not always truthful

|

71

|

23

|

|

A

|

Anticipate future tax problems

|

57

|

26

|

|

B

|

Ever dropped a client who did not meet their tax obligations?

|

53

|

39

|

|

D

|

Clients threaten to go elsewhere

|

47

|

39

|

Tax agents appear to hold the role of tax arbiter and must juggle their professional and legal obligations. Tax agents currently hold the prominent role of regulator of taxpayer compliance behaviour. When asked if tax agents should not keep as clients any taxpayers who evade taxes, or whether they had dropped clients who failed to meet their tax obligations the results showed that only half of the tax agents did so (Tables 8 and 9). This lack of conformity enables taxpayers, if they wish, to shop around for an obliging tax agent who will assist them to evade their tax obligations. Taxpayers’ perceptions of their tax agents and “ideal” tax agents influence their choice of a tax agent. Taxpayers may seek a “creative accountant, aggressive tax planner”, a “cautious minimizer of tax”, or the “low risk, no fuss” type to achieve their tax goals and obligations.[19] Tax agents have obligations to meet the tax industry’s practicing standards and while these standards fulfill an educational and advisory role for practicing tax agents, those standards will become more important as the ATO and tax law “push for more due diligence on the part of tax practitioners”.[20]

Table 9: Differences Between Taxpayers and Their Tax Agents (Aim 5). A Comparison of the Means for Taxpayer and Tax Agents for Selected Items Ranked According to Difference Score

* Independent sample t-test- statistically significant differences in means to p<.05 (95% confidence level)

|

TP Item

|

Taxpayer (TP) Mean

|

TA Item

|

Tax agent (TA) Mean

|

TA-TP Difference

|

Item

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Client service relationships and expectations

|

|

43

|

4.38

|

29

|

4.92

|

0.54*

|

ATO staff are helpful when dealing with my enquiries about tax

returns

|

|

56

|

4.63

|

42

|

5.11

|

0.48*

|

Nowadays the ATO is making a big effort to help taxpayers understand laws

& regulations

|

|

39

|

4.39

|

26

|

4.71

|

0.32*

|

ATO staff treat me fairly

|

|

3

|

3.82

|

1

|

4.05

|

0.23

|

I avoid asking the ATO for advice about my tax return

|

|

55

|

3.95

|

41

|

4.13

|

0.18

|

The ATO is fair and considerate with those who get audited

|

|

44

|

4.36

|

30

|

4.50

|

0.14

|

In my opinion, the ATO is professional in the way it treats me as a

taxpayer

|

|

53

|

3.48

|

39

|

3.31

|

-0.17

|

When the amount of avoidance is small the ATO should let it go

|

|

40

|

4.30

|

27

|

4.00

|

-0.3

|

I am satisfied with the service the ATO provides

|

|

11

|

4.30

|

5

|

3.89

|

0.41*

|

The ATO gives me accurate advice

|

|

5

|

4.05

|

2

|

3.55

|

-0.5*

|

The ATO gives me advice without delay

|

|

51

|

4.96

|

37

|

4.35

|

0.61*

|

I prepare my tax return correctly as there is a strong chance I would get

caught if I didn’t

|

|

70

|

4.97

|

56

|

3.98

|

0.98*

|

There is a strong chance that a taxpayer will get audited by the ATO

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tax return behaviour

|

|

35

|

2.85

|

22

|

3.76

|

0.90*

|

When I do not expect a refund, I put off completing my tax return

|

|

33

|

3.93

|

21

|

4.48

|

0.54*

|

If I think the refund will be more than $500, I complete my tax return as

soon as possible

|

|

81

|

5.08

|

67

|

5.47

|

0.39

|

Tax laws and regulations sometimes seem to contradict one another

|

|

75

|

4.73

|

61

|

5.03

|

0.31

|

It is difficult to complete a tax return 100% accurate tax return

|

|

31

|

3.48

|

19

|

3.77

|

0.30

|

Because it is uninteresting, I put off completing my tax return

|

|

64

|

5.12

|

50

|

5.39

|

0.27

|

In my opinion, tax laws and regulations are always changing, so it is very

difficult to get a tax return exactly right

|

|

27

|

6.14

|

16

|

6.39

|

0.25

|

It is ethical to claim for everything you are entitled to

|

|

28

|

6.04

|

17

|

6.29

|

0.25

|

It is everyone’s responsibility to pay the correct amount of

tax

|

|

17

|

2.92

|

7

|

3.08

|

0.16

|

In my opinion tax return forms are easy to complete

|

|

63

|

5.18

|

49

|

5.23

|

0.05

|

Changes in the tax law make it difficult to understand which deductions you

can claim

|

|

32

|

4.62

|

20

|

3.74

|

-0.87*

|

Even if I do not expect a refund, I put off completing my tax return

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ethics and tax responsibility

|

|

90

|

5.78

|

76

|

5.32

|

-0.45*

|

It is the responsibility of tax professionals to ensure clients pay the

correct amount of tax

|

|

Na

|

na

|

80

|

5.21

|

NA

|

Tax agents should not keep as clients, taxpayers who avoid taxes

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tax Knowledge – True/False Quiz

|

|

TF1

|

.71

|

TF1

|

.87

|

.16*

|

New employees must complete an Employment Declaration within 14 days of

starting job

|

|

TF2

|

.62

|

TF2

|

.78

|

.14*

|

Employers are required to lodge Employment declarations within 28 days of

new employee start

|

|

TF3

|

.81

|

TF3

|

.61

|

-.20*

|

Everyone aged 16yrs and over earning any income should have a tax file

number

|

When we consider the tax agents we find that in general taxpayers and tax agents are in broad agreement. Where they differ, a difference might be expected because of special knowledge and perceptions of responsibility. Eighty seven percent of taxpayers agreed that it was the responsibility of tax agents to ensure that their clients paid the correct amount of tax (Table 7), but only 13% of tax agents agreed with this position. Taxpayers place tax management responsibility on the shoulders of their tax agents. The tax agents, however, are unwilling to accept this role or level of responsibility. Tax competence is based on taxpayers having a basic level of tax knowledge and tax agents having expert knowledge. The quiz items were based on those used at secondary schools for tax file number registration education. As expected, statistically there was a significant difference in level of knowledge between tax agents and taxpayers. Nevertheless, tax agents scored higher on only two of the three items.

Table 10: Aim 5 – Differences between tax agents and taxpayers Independent t-test significance p<.05

|

Item

|

Tax Agent Means

|

Taxpayer Means

|

Tax Agent SD

|

Taxpayer SD

|

t

|

df

|

Significance level

|

|

Q5

|

3.55

|

4.05

|

1.59

|

1.42

|

-2.64

|

877

|

.01

|

|

Q11

|

3.89

|

4.30

|

1.46

|

1.30

|

-2.38

|

874

|

.02

|

|

Q35

|

3.76

|

2.85

|

1.79

|

1.54

|

4.40

|

889

|

.0001

|

|

Q39

|

4.71

|

4.39

|

1.50

|

1.20

|

2.01

|

894

|

.04

|

|

Q51

|

4.35

|

4.96

|

1.98

|

1.61

|

-2.81

|

886

|

.005

|

|

Q70

|

3.98

|

4.97

|

1.69

|

1.30

|

-5.57

|

878

|

.0001

|

|

Q90

|

5.32

|

5.78

|

1.59

|

1.25

|

-2.70

|

885

|

.01

|

|

Knowledge TF1

|

.87

|

.71

|

.47

|

.53

|

2.17

|

871

|

.02

|

|

Knowledge TF2

|

.78

|

.62

|

.56

|

.54

|

2.24

|

865

|

.03

|

|

Knowledge TF3

|

.61

|

.81

|

.77

|

.48

|

-2.87

|

871

|

.004

|

As we have said, the aims of this study were fivefold. First, to see why taxpayers may or may not self-prepare, and whether there was support for a rational maximizer model of tax compliance. Second, to see whether or not there was support for the BTP Model. Third, to describe how taxpayers saw the ATO. Fourth, to see why taxpayers used tax agents, and not simply self prepare. Fifth, to determine whether there were any important differences between the views of taxpayers and the views of tax agents.

Between 95.5% and 100% of the sample reported that they intended to be compliant. This result was surprising given 59% of the taxpayers were identified, according to reported and recorded ATO tax return history as either medium or high risk. According to the Australian national tax return data system, 3.8% of taxpayers did not meet their lodgment obligations in 1999. The taxpayer sample was according to observed behaviour fairly compliant with regard to lodgment and less compliant in the debt area.

Aims 1a and 1b: Why Taxpayers May or May Not Self Prepare and Are They Rational Maximizers

Taxpayers may prefer not to self prepare because of their limited knowledge and competence, their understanding of the tax law, their engagement levels with tax related documents, the limited motivation available (refund vs penalty), and also the high demands of tax knowledge maintenance and competence (Table 3). There are also concerns about genuine mistakes and their consequences. There is little support for a “rational minimizer” view of the taxpayer. Taxpayers want to complete satisfactory tax returns, to get the refund they deserve, and to stay out of trouble.

Aim 2: The BTP Model – Self-preparing

The results (Table 3) provided moderate support for the BTP Model and can be taken to reflect taxpayers’ own standards of taxpaying behaviours, tax compliance or non-compliance, compared to those expected of them by the ATO (and the law). It is unclear whether taxpayers truly understood the ATO’s expectations and the differences between the ATO’s and their own levels of competence and tax compliance. If any low-level avoidance were not pursued by the ATO, then low level avoidance behaviour could become the new tolerance level, the acceptable taxpayer compliance behaviour. Certainly, as the BTP Model implies, preparation of a tax return is seen as complex and difficult.

Aim 3: ATO Client Relationships

The results (Tables 5 and 6) reported that aspects of the ATO client service were identified as a significant taxpayer issue. Taxpayers in particular reported only moderate levels of satisfaction. It needs to be noted that this study was conducted just prior to GST and tax reform. It is anticipated that the levels of satisfaction with client service have since been affected. Client service was associated strongly with fairness, tax being difficult, satisfaction, knowledge, and using a tax agent.

The results indicated that in the main Australian taxpayers were compliant and that there was a propensity to comply. Nevertheless, some taxpayers did indicate that they tolerated low levels of non-compliance. The factors that impacted taxpayers’ ability to maintain tax compliance collectively contributed to increased risk behaviour. These results imply that the ATO should continue its commitment to client service, increase collaborative relationships with tax agents, provide broader tax education programs that include managing financial affairs, and publicise more widely that tax debt repayment options are available. Taxpayer co-operation is dependent on their tax experiences as well as intent to comply. To sum up, the fact that so many taxpayers use tax agents provides an opportunity to increase tax compliance at very little additional cost, given that ATO structures are already in place to provide tax agents with streamlined communication and services, and that the tax agent population is significantly smaller than that of individual taxpayers. Although the tax system is built on the implicit assumption that all individual taxpayers should be able to self-prepare, in practice that is not an option that most taxpayers choose. As indicated in table 7, the main reasons for using tax agents were to avoid errors, receive entitlements, and get good advice, presumably about making correct claims.

Aim 4: Tax Agent Role – Why Taxpayers Use Tax Agents

The results in table 9 indicate the key significance of the tax agent’s role. The findings show that taxpayers believed that they had a low level of tax related knowledge and in the main depended on tax agents to assist them. There was a clear indication of the transfer of taxpayers’ tax responsibility to their agent. Tax agents in Australia are the intermediaries between the ATO and their taxpaying clients. Close to 75% (86% in the present sample) of taxpayers use a tax agent. Agents act primarily as tax return processors, but their role as principal advisors means that they also assist clients with legal tax minimization and correct reporting. Some argue that their relationship with taxpayer compliance may be viewed as “compliance in form rather than in substance, undermining rather than bolstering enforcement”.[21] Kidder and McEwen[22] call them “Compliance Brokers”. Roth, Scholz, and Witte,[23] however, suggested that “if practitioners can be encouraged to foster compliance in their clients, enforcement resources could be concentrated on the most problematic areas”. Some research has found that there is a higher risk of tax avoidance and evasion where tax professionals have prepared tax returns.[24] Baldry[25] identified a high correlation between deductions claimed and the proportion of taxpayers who lodged tax returns using a tax agent. Tomasic and Petony[26] and Nixon[27] recognised the intermediary role that tax practitioners have in the Australian taxation system. Because of their dual responsibility (tax system and client), some taxpayers might see tax agents as agents or clients of the ATO.[28] Tax agents, however, have to strive to balance the tension between unimpeachable ethical values and supporting eg tax planning schemes that may or may not be sustained by the Courts. Taxpayers, on the other hand, may perceive moral responsibility as the exclusive domain of tax advisors and they may expect tax agents to be fully accountable, and produce a 100% correct tax return and provide accurate advice.

Aim 5: Differences Between Taxpayers and Their Tax Agents.

The results (Table 10) highlighted the differences between taxpayers and tax agents. Most differences were minimal; the most significant result was that taxpayers held tax agents responsible for correct error free tax returns and that taxpayers had less than the basics of tax knowledge. Taxpayers also expected tax agents to ensure that taxpayers paid the correct amount of tax and take responsibility for the associated risks. This tension in the client relationship places tax agents in an unenviable position. They take on the responsibility for conducting an ethical and law-abiding business, and at the same time are directed to minimize their clients’ tax. How tax agents influenced final outcomes was not investigated in detail but 90% of tax agents admitted that their clients sometimes delayed lodging tax returns. The taxpayer and tax agent relationship will require closer exploration and should be the focus of future research. As far as policy implications are concerned, the results are consistent with the notion that the tax agent should be seen as an integral part of the tax collection system, able to make significant contributions to quality control and the problem of correct tax returns. The low levels of basic tax knowledge may be another reason why taxpayers transfer their tax obligations to tax agents, and also explains why taxpayers perceive tax as complex and time consuming.

The five aims of the study were: to determine why taxpayers self prepared or not, and whether they were rational tax minimisers, to test the BTP Model, to investigate ATO client relationships and the role of tax agents, and to determine the differences between taxpayers and tax agents. All aims were addressed and results provided significant insights into the relationships between the ATO and its two client bases – taxpayers and tax agents. The study identified the two key areas of tax knowledge/tax competence and the transfer of tax responsibility to tax agents. The results provide both the ATO and tax agents with insights into how they can develop client relationships that foster tax compliance.

In the main Australian non-business taxpayers were compliant and there was a propensity to comply. There was no “tax rage” exhibited by any group, but taxpayers clearly indicated that they tolerated low levels of non-compliance behaviour. Factors such as tax knowledge, tax complexity, record keeping, organisation, and the time involved impacted taxpayers’ ability to maintain compliance. These “psychological costs” collectively contributed to increased risk behaviour. The data suggest that the ATO should continue its commitment to the strategy of “listening to the community”,[29] access and equity issues, target potential risk groups and provide them customised client service. Perhaps the ATO should increase collaborative relationships with tax agents and expand specialised services such as the web based Taxagent Portal,[30] provide at risk groups broader tax education programs aimed at improving their tax competence and management of financial affairs, as well as publicise more widely that the ATO is flexible regarding tax debt repayment. Taxpayer co-operation is dependent on their tax experiences as well as intent to comply. The ATO and tax compliance would benefit from taxpayer and taxagent participation and evaluation of any new programmes developed to understand and then meet client expectations. On the other hand, taxpayers and tax agents would benefit from customised programmes aimed at improving client service, tax knowledge and competence in order to improve tax compliance.

Generally, the non-compliant taxpayer sample was not representative of a high risk population. Future research would benefit from comparing only the two extremes of tax behaviour – exemplary compliance and highest risk non-compliance. Non-compliance or compliance was preceded by factors from personal and environmental circumstances. These factors then impacted taxpayers’ capacity to meet their obligations. Avoidance of dealing with tax problems rather than deliberate tax avoidance were, in the main, a major contributor to actions defined by tax law as tax avoidance. It was not clear if high-risk taxpayers exhibited identical features because the sample size of highest risk was too small – less than 30. This limitation could be addressed by expanding the research sample to small business taxpayers. There may be insufficient high-risk individual non-business taxpayers to warrant further study unless the ATO shares data with other government agencies, and annually monitors behaviours so that it can readily identify them. The role of the taxagent and level of tax knowledge are significant factors in taxpayers’ and ATO taxpayer relationships. Research into the levels of taxpayer and taxagent knowledge is important so that the ATO can determine which areas of knowledge most impact taxagent productivity, and deter taxpayer engagement. In addition, the various tensions (procedural, legal and ethical) experienced in tax agents attempts to meet both ATO and client expectations could guide future research and ATO policy, and also reinforce tax agents’ role as knowledge brokers and compliance mediators/gatekeepers.

[*] PhD candidate, Department of Psychology, University of Adelaide.

[∗∗] Professor,

Department of Psychology, University of Melbourne.

Direct enquiries to:

ajwe@unimelb.edu.au or apolonia.niemirowski@adelaide.edu.au

[∗∗∗] The Determinants of Australian Taxpayer Compliance study was conducted by the ATO 2000/2001. This article was published with the permission of the ATO, but the opinions expressed by the authors are not necessarily the views of the ATO. The authors wish to thank Chris Mobbs of the ATO for his helpful and stimulating comments on earlier versions of this article.

[1] ATO, “Where to With Tax

Assessment?” (Michael Carmody, Commissioner of Taxation, CEDA address

Public Education Meeting,

3 July 1997, Brisbane).

http://www.ato.gov.au/print.asp?doc=/content/sp9703.htm accessed

05/09/03.

[2] ATO, above n 1.

[3] ATO, “Administering

Australia’s Tax System or ‘Walking the Tightrope’“

(Michael Carmody, Commissioner

of Taxation, Monash University, Law School

Foundation Lecture, 30 July 1998).

http://www.ato.gov.au/corporate/content.asp?doc=/content/sp9805.htm

accessed 30/09/03.

[4] ATO, “Improving Tax Compliance in the Cash Economy” (1998); V Braithwaite, “Managing Tax Compliance: the Evolution of the ATO Compliance Model” (Paper presented at the 4th International Conference on Tax Administration, April 2000, Sydney); and M D’Ascenzo, “Y2K Relationships – The ATO and You Post 2000” (2000) 34(8) Taxation in Australia 421.

[5] ATO, “The Changing Tax

Landscape” (Michael Carmody, Commissioner of Taxation, Address to the

Institute of Chartered Accountants

in Australia Networking Luncheon, May

2002).

http://www.ato.gov.au/content.asp?doc=/content/Corporate/sp200204.htm

accessed 22/05/2003; and ATO, “Tax Office Making it Easier to

Comply” (Media release Nat 03/76, 21 July 2003)

http://www.ato.com.au/print.asp?doc=/content/mr2003076.htm accessed

27/07/2003.

[6] S James and I Wallschutzky,

“Tax Law Improvement in Australia and the UK: The Need For a Strategy For

Simplification”

(2000) 18(4) Fiscal Studies 445; and ATO, “Listening

to the Community” (2000).

http://www.ato.gov.au/fsmke/ATO/ePub_30679.htm accessed

22/05/2003.

[7] A Niemirowski, AJ Wearing and S Baldwin, “Tax Related Behaviours, Beliefs, Attitudes and Values and Taxpayer Compliance in Australia” [2003] JlATax 5; (2003) 6 Journal of Australian Taxation 132.

[8] Niemirowski et al, above n 7.

[9] M McKerchar, “A Study of Complexity and Unintentional Non-compliance for Individual Non-business Taxpayers in Australia” (2002) 17 Australian Tax Forum 3.

[10] The BTP Model was constructed on the basis of working notes that Steve Baldwin left behind before his unexpected death.

[11] The Integrated Compliance Study (“IC Study”) was an ATO study of compliance risk probabilities for non-business taxpayers.

[12] This model is due to Steve Baldwin.

[13] ATO, above n 11.

[14] J Alm, B Jackson and M McKee, “Alternative Government Approaches for Increasing Tax Compliance” (1990) 90 TNT 260-42; and SB Long and JA Swingen, “Taxpayer Compliance: Setting New Agendas for Research” (1991) 25 Law and Society Review 645.

[15] D McBarnett, “The Construction of Compliance and the Challenge for Control: The Limits of Non-Compliance Research” in J Slemrod (ed), Why People Pay Taxes (1992) 339.

[16] Niemirowski et al, above n 7.

[17] JS Carroll, “How Taxpayers Think About Their Taxes” (Paper presented at the Tax Compliance and Tax Law Enforcement Conference, University of Michigan, 1990).

[18] ATO, “Get Your Tax Return Right First Time” (Media release Nat 97/23). http://www.ato.gov.au/content.asp?doc=/content/Corporate/mr9723.htm accessed 03/10/2003.

[19] Y Sakurai and V Braithwaite, “Taxpayers’ Perceptions of the Ideal Tax Advisor: Playing Safe or Saving Dollars?” (Centre for Tax System Integrity Working Paper No 5, May 2001). http://ctsi.anu.edu.au/publications.html accessed 02/10/03.

[20] J Gardner, S Willey and V Moore, “CPA’s Responsibilities in Tax Practice” (Jan 1989) 59(1) The CPA Journal 12.

[21] McBarnett, above n 8.

[22] R Kidder and C McEwen, “Taxpaying Behaviour in Social Context: A Tentative Typology of Tax Compliance and Non-compliance” in JA Roth, JT Scholz and AD Witte (eds), Taxpayer Compliance: Volume 2 Social Science Perspectives (1989) 50.

[23] JA Roth, JT Scholz and AD Witte, “Expanding the Framework of Analysis” in JA Roth, JT Scholz and AD Witte (eds), Taxpayer Compliance: Volume 1 An Agenda for Research (1990) 178.

[24] IG Wallschutzky, “Taxpayer Attitudes to Tax Avoidance and Evasion” (Research Study No 1, Australian Tax Research Foundation, 1985).

[25] J Baldry, “Personal Income Tax Deductions in Australia 1978/79-1990/91” (1994) 70(511) The Economic Record 424.

[26] R Tomasic and B Petony, “Taxation Law Compliance and the Role of Professional Tax Advisers” (Tax Compliance Workshop, Taxation Business and Investment Law Research Centre and KPMG Peat Marwick Hungerfords, August 1989).

[27] T Nixon, “Current Problems in Tax Decision Making. Do Tax Agents Assist Voluntary Compliance?” (Unpublished Paper, 1998).

[28] B Jackson and V Milleron, “Tax Preparers: Government Agents or Client Advocates?” [May 1989] Journal of Accountancy 167.

[29] ATO, “Listening to the

Community: Easier, Cheaper, More Personalised” (Michael Carmody,

Commissioner of Taxation, Address

to the American Chamber of Commerce, 14 March

2002).

http://www.ato.gov.au/corporate/content.asp?doc=/content/sp200202.htm

accessed 06/10/03.

[30] ATO, “A New Compact

With the Tax Professions” (Michael Carmody, Commissioner of Taxation,

Luncheon Address to the Taxation

Institute of Australia NSW Division, 22 October

2002, Sydney).

http://www.ato.gov.au/corporate/content.asp?doc=/content/sp200208.htm

accessed 06/10/03.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/JlATax/2003/6.html