Journal of Australian Taxation

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Journal of Australian Taxation |

|

NEGATIVE GEARING AND HOUSING AFFORDABILITY FOR FIRST HOME BUYERS

By Kim Wyatt,[∗] Jarrod McDonald[∗∗] and Mohan Nandha[∗∗∗]

Australia’s recent housing boom and associated higher property values has engendered a scenario whereby buyers need to borrow more to purchase properties. First home buyers are particularly disadvantaged in this market as they are competing against property investors who can take advantage of generous tax concessions. The purpose of this article is to compare the value of the tax advantages available to property investors against the Federal Government’s first home buyers’ grant and various State Government grants and benefits available to first home buyers. This article reveals that not only are wealthy property investors better off in the longer-term by over $100,000, but their presence in the housing market is distorting housing prices. It appears that these favourable tax breaks have negatively impacted on first home buyers by encouraging them to defer purchasing a slice of the great Australian dream-home ownership. This finding raises doubts about the efficacy of current government policy, which allows property investors to negatively gear their properties whilst future generations are kept out of the housing market.

In August 2003, the Federal Treasurer, Mr Peter Costello, requested the Productivity Commission (“Commission”) to undertake an inquiry to evaluate the affordability and availability of housing for first home buyers. Two of the aims identified by the Commission were the delineation of potential impediments to first home ownership and a concurrent feasibility and implication assessment of mechanisms to reduce or remove such impediments.

Over three hundred submissions were received by the Commission; a number of which advocated a reduction in the tax benefits available to property investors and/or an increase in the government funds available to first home buyers. One of the key findings of the Commission was that the tax benefits available to property investors may contribute to inefficient outcomes within the housing and other asset markets and should therefore be the subjected to a broader review.[1]

The continued increase in property prices appears to be putting the great Australian dream of home ownership under duress. In the six years to June 2003, Melbourne’s median housing prices increased by 114%[2] compared with a 17.5% movement in the Consumer Price Index over the same time period.[3] As Malcolm Turnbull, the Head of the Prime Minister’s Home Ownership Taskforce, has stated, such increases have made the home ownership ambition harder to attain,[4] with first time home buyers forced to borrow more in order to meet the increases in house prices.

The current activity in the housing sector can be encapsulated as either that pertaining to “owner-occupiers” or “property investors”. In definitional terms, owner-occupiers are those purchasers of property who intend to live in the purchased property, while property investors are those who intend to rent out the purchased property to tenants in return for rental income.

In regard to owner-occupiers, the most disadvantaged within this group would be the first home buyers, who frequently enter the market with little or no savings. In contrast, those owner-occupiers who are trading up their existing house, albeit with a mortgage in tow, are in a better position in that their home is likely to have kept pace with rising housing prices. The current primary incentives for first home buyers are the Federal Government first home-buyers grant and the additional grants and exemptions available from the respective State Governments. Between 1992 and 2002, the number of Australians requiring finance to purchase their first home ranged between 96,000 and 142,000 per year. The fact that this number peaked in 2001-2002 reflects the benefit of lower interest rates and the availability of the First Home Owners Grant for first home buyers.[5]

In July 2000, the Federal Government introduced a First Home Owners Grant of $7,000 available to first homeowners buying either a new or existing house. A modification to this grant was introduced in early 2001, which involved a staged additional bonus being made available to first home buyers. The first stage involved an additional bonus of $7,000 being offered to first home buyers who entered into contracts to either build or purchase a new unoccupied home between 9 March 2001 and 31 December 2001, inclusive. The second stage, which commenced on 1 January 2002, saw the bonus reduced to $3,000, while the third stage involved the phasing out of this remaining additional bonus of $3,000 on 30 June 2002.[6]

Unlike first home buyers, the other main group within the housing sector, property investors, have the facility to take advantage of the taxation system by negatively gearing their rental investments. Negative gearing, in the housing market, occurs when the income generated from rents is less than the interest incurred from the funds borrowed to acquire the property and other rental expenses. In such situations, investors are able to offset the negatively geared amount against their other taxable income, thereby reducing the amount of tax they pay to the Government. Australian Taxation Office (“ATO”) Statistics show that in 1999-2000, 54% of rental housing landlords claimed to be operating at a loss resulting in accrued tax savings in excess of $1 billion.[7]

Although capital gains on investment properties are subject to taxation, there are advantages to property investors who have held a rental property for more than one year. The advantages are as follows: (i) only half the capital gain is taxable and only at the time of sale; and (ii) these capital gains can be offset against any capital losses that the property investor may be holding from other asset sales. Moreover, in the unlikely event a capital loss was to occur at point of sale, then the property investor can offset this against any current or future capital gains they may derive from other asset sales. Owner-occupiers, however, are disadvantaged by the fact that under the current taxation system, expenses related to the running of the house cannot be claimed against other taxable income. Furthermore, this group cannot offset any incurred capital losses (if any) from the sale of their house against any other capital gains that they may have derived from other asset sales. The Victorian Council of Social Service submission to the Productivity Commission Inquiry into First Home Ownership noted that “by subsidising investors in a way home purchasers are not subsidised, negative gearing undermines the objectives of the First Home Owners Grant by gifting a competitive advantage to investors over first home buyers”.[8]

Negative gearing was accepted by the Full Federal Court in FC of T v Janmor Nominees Pty Ltd.[9] In this case the property was negatively geared and the taxpayer returned the rent as assessable income and claimed a deduction for the interest and revenue expenses which exceeded the rent. The Full Federal Court in Janmor specifically stated that no apportionment would apply to the deductions claimed and that (obiter) the arrangement would not be subject to Pt IVA of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (Cth).

In essence, the current taxation incentives, with their clear benefits to property investors, have encouraged increased uptake of rental property ownership and have contributed to the burgeoning house prices across Australia over recent years. Although it can be argued that this trend has also benefited existing homeowners, it has clearly acted as an impediment to the movement of first home buyers into the real estate market. By way of illustration, the Reserve Bank of Australia’s submission to the Productivity Commission Inquiry on First Home Ownership[10] discussed the fact that the ratio of average house price to average income has risen sharply over recent years. An examination of June quarter of 2003 data revealed that the median house price in Australia was equivalent to six times the annual average household income, up from the ratio of four times annual income reported in 1997.

Further evidence of the barriers to first-time home ownership can be seen in the Australian Bureau of Statistics (“ABS”) monthly finance figures, which revealed a 3.2% increase in loan approvals in July 2003 for owner occupied homes. It is important to note that less than 15% of these loans went to first home buyers compared to the historical average of 20-25%.[11] In fact, the 2003 level of first homebuyer loans were the lowest since the ABS first began reporting these figures in July of 1991. Property investors now account for 30% of the value of all home loans. When compared across time, the percentage of investor loans has risen by 21.6% over the past decade, compared to a 13.4% rise for owner occupied housing loans.[12]

The fact that the top marginal tax rate of 48.5%, which includes the Medicare levy, is at a relatively low taxable income level ($60,000 for 2001-2002 and $70,000 for 2004-2005) also favours property investors in Australia, as a large percentage of taxpayers are attracted to investments that will decrease the amount of tax that they pay. Negative gearing of investment properties is such an attraction. These factors illustrate that the first homebuyer is finding it very difficult to compete and is being squeezed out of the market.

Given this information, it is somewhat surprising that the Federal Government inquiry did not critically examine the impact of negative gearing on the affordability of housing for first home buyers. One possible explanation is that the issue is politically sensitive to both the major political parties. This article attempts to quantify the value of the relative tax advantages available to property investors as compared to the owner-occupiers, particularly in regard to the first homebuyer.

The next Section seeks to provide the reader with an understanding of how changes, in some market forces, over the recent years have enhanced the value of negative gearing. Section 3 quantifies, on a present value analysis, the value of the tax benefits available to property investors and compares this with government grants available to first home buyers entering the property market. Section 4 examines the evidence available from the ATO in regard to the magnitude of these tax benefits and Section 5 provides a summary of the findings.

Anecdotal evidence could suggest that informed and “upbeat” property investment seminars directed at underscoring the advantages of negative gearing have contributed to the increasing uptake of this investment strategy. Other contributing factors include falling interest rates, relaxed lending practices such as the offering of split loans, and the creation of deposit bonds.[13] While the major banks previously charged a 1% premium on investment loans, they now offer the same lending rate for both owner occupied and investment-housing loans. Consequently, housing investors have gained an added incentive to pursue this avenue of investment.

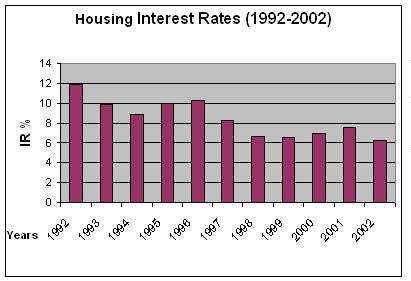

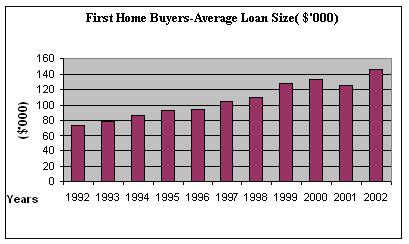

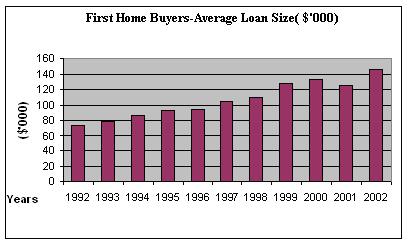

Chart 1 illustrates that housing interest rate levels at which money can be borrowed for housing have almost halved during the period between the early and late 1990s. The growth in first home buyers’ average loan size since 1992 is illustrated in Chart 2. Such loans have more than doubled over this period, thereby suggesting that first home buyers have had to borrow more in order to be able to enter the housing market.

Chart 2:[15]

The presence of low interest rates and the concomitant lower periodic repayments have resulted in individuals having a greater capacity to borrow more money. Although this is true for both first home buyers and property investors, the latter have more access to tax benefits. In a low interest rate environment, first home buyers typically require more time to accumulate the savings necessary to provide an initial deposit. Antithetically, for the property investor, the presence of low interest rates increase the worth of the tax savings generated through negative gearing. For example, consider the case of a first homebuyer who can afford to save $1,000 per month and has plans to accumulate $60,000 for an initial deposit. In a hypothetical high interest rate environment of 15% per annum, it would take approximately 45 months to accumulate $60,000. Compare this to the 54 months required to save the same deposit in a low interest rate environment of 5% per annum.

Now consider the scenario whereby an investor can save $5,000 tax per annum over a period of 30 years. The present value of this hypothetical savings stream, discounted at 15%, would be $32,830. However, in the low interest rate environment and hence low discount rate, the same stream of expected savings, discounted at 5%, would be worth $76,862. Considering that interest rates in Australia have come down from the 18% highs experienced in the 1980s to the current levels of around 6%, the enhanced worth of taxation benefits generated through negative gearing becomes even clearer.

Interestingly, and somewhat counter-intuitive to the fiscally unaware citizen, first home buyers wanting to save for an initial deposit would be better off with high interest rates, as these would decrease the time required to reach their savings goal. Obviously, upon purchase of their home, low interest rates would then be preferable. In contrast, a property investor is better off in a low interest environment, since the present value of their tax savings over time is greater.

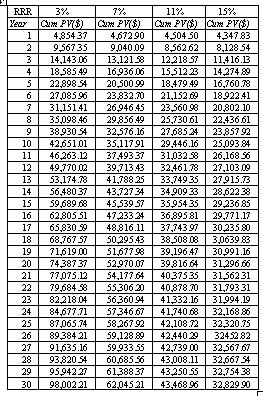

To further explicate this argument, we have calculated the Cumulative Present Value (“Cum PV”) of a property investor’s annual $5,000 tax benefit stream across various combinations of holding periods and Required Rates of Return (“RRR”). As can be seen from Table 1, a decrease in RRR from 15% (high interest rate environment) to 3% (a low interest rate environment) has the potential over a 30 year period to magnify the Cum PV by up to three times. These findings can impact on investor psychology with respect to whether or not they choose to enter the property market and can therefore impact on housing prices.

RRR= required rate of return;

Cum PV= cumulative PV for the corresponding number of years.

Australia has a very high proportion of home ownership with banks and other mortgage lenders becoming increasingly relaxed about extending loans for residential properties.[16] In 2001 over 69.5% of Australians owned or were purchasing their house.[17] Although theoretically, a typical loan can be up to 90% of the house price assuming a 10% deposit, some investors borrow more than 100% of market value, in order to cover stamp duty, borrowing costs and conveyancing costs. This latter practice can, in part, be attributed to a desire to maximise the value of tax benefits arising out of negative gearing.

The length of the loan period is another key factor in the amount of interest, and hence a determinant in the resulting taxation deductions. Two key developments in this area have been a change from full repayment loans to “interest only” loans and a relaxation in the loan term so as to maximise the payback period. It can be argued that in fact an “interest only” loan has an indefinite loan term-maturity. These developments have increased the value of the tax benefits available to property investors involved in negative gearing.

In the case of full repayment loans, the repayments are composed of two parts: principal repayment and interest payment. As repayments are made, the amount of principal (outstanding loan) decreases leading to a reduction in the interest component. As the interest component is tax deductible, the amount of tax deductions decreases with the passage of time. However, the advent of “interest only” loans has provided a mechanism by which the principal amount remains unchanged, while all repayments made to service the loan becoming eligible for tax deduction. By way of illustration, consider a 20-year term loan of $100,000 with a 6.5% per annum interest rate and annual payments. As shown in Table 2, the total interest payment for a full repayment loan is $81,512.78, but in the case of interest only loan, the total interest payment would be $130,000. This translates into an increase of $48,487.22 in the tax-deductible amount over the period of 20 years. The move, in recent years, to interest only loans has therefore increased the potential tax savings to a property investor. In fact in our example from Table 2, an additional tax benefit of $23,516.30 over 20 years is achieved for a property investor in the top (48.5%) marginal tax rate (“MTR”). Again, this mechanism has fuelled investor interest in the housing market and has increased demand for properties, which in turn has contributed to higher house prices.

∗Interest payments based on a 20 year maturity loan of $100,000; interest rate 6.5% per annum; payment of frequency annual.

∗∗Interest payments based on a $100,000 “interest only loan”.

|

Year

|

Loan

|

Repayment

|

Principal

|

Interest*

|

Interest (IOL)**

|

|

1

|

100,000.00

|

9,075.64

|

2,575.64

|

6,500.00

|

6,500.00

|

|

2

|

97,424.36

|

9,075.64

|

2,743.06

|

6,332.58

|

6,500.00

|

|

3

|

94,681.30

|

9,075.64

|

2,921.36

|

6,154.28

|

6,500.00

|

|

4

|

91,759.95

|

9,075.64

|

3,111.24

|

5,964.40

|

6,500.00

|

|

5

|

88,648.70

|

9,075.64

|

3,313.47

|

5,762.17

|

6,500.00

|

|

6

|

85,335.23

|

9,075.64

|

3,528.85

|

5,546.79

|

6,500.00

|

|

7

|

81,806.38

|

9,075.64

|

3,758.23

|

5,317.41

|

6,500.00

|

|

8

|

78,048.16

|

9,075.64

|

4,002.51

|

5,073.13

|

6,500.00

|

|

9

|

74,045.65

|

9,075.64

|

4,262.67

|

4,812.97

|

6,500.00

|

|

10

|

69,782.97

|

9,075.64

|

4,539.75

|

4,535.89

|

6,500.00

|

|

11

|

65,243.23

|

9,075.64

|

4,834.83

|

4,240.81

|

6,500.00

|

|

12

|

60,408.40

|

9,075.64

|

5,149.09

|

3,926.55

|

6,500.00

|

|

13

|

55,259.30

|

9,075.64

|

5,483.79

|

3,591.85

|

6,500.00

|

|

14

|

49,775.52

|

9,075.64

|

5,840.23

|

3,235.41

|

6,500.00

|

|

15

|

43,935.28

|

9,075.64

|

6,219.85

|

2,855.79

|

6,500.00

|

|

16

|

37,715.44

|

9,075.64

|

6,624.14

|

2,451.50

|

6,500.00

|

|

17

|

31,091.30

|

9,075.64

|

7,054.71

|

2,020.93

|

6,500.00

|

|

18

|

24,036.60

|

9,075.64

|

7,513.26

|

1,562.38

|

6,500.00

|

|

19

|

16,523.33

|

9,075.64

|

8,001.62

|

1,074.02

|

6,500.00

|

|

20

|

8,521.71

|

9,075.64

|

8,521.71

|

553.91

|

6,500.00

|

|

|

Total

|

100,000.00

|

81,512.78

|

130,000.00

|

|

The Australian Labor Party has pledged to cap the first homeowner’s grant at million dollar homes and appoint a national housing minister to increase the affordability of houses.[18]

Despite the Labor Party’s 2004 election pledge the Federal Treasurer Peter Costello was unmoved and indicated that “the government will continue to support the first home owner’s scheme and will not restrict or means test the current $7,000 grant, thereby continuing access to all first home buyers”.[19] The Democrats leader Senator Bartlett proposed that the first homeowners should be means tested,[20] whilst the Australian Greens Party called for negative gearing to be progressively phased out.[21]

Two recent developments will lead to a decrease in the benefits of negative gearing available to property investors. From July 2005, the top tax bracket of 48.5% for taxpayers will be $80,000, an increase from $60,000 in 2001. This increased tax threshold will see some taxpayers, those with taxable income of less than $80,000, having reduced tax benefits from negative gearing, although they will benefit from a tax cut in regard to their other income.[22] The Federal Government has also introduced tougher deprecation rules that will further reduce tax benefits to the property investor from July 2005 as the depreciation rates for chattels in the investment have been reduced.[23]

In early April 2004, the New South Wales Government introduced the First Home Plus Program. This program enables first home buyers buying a home for less than $500,000 to be exempt from stamp duty and mortgage duty. This results in a saving of $10,000 on a $300,000 home purchase. The program is phased out between $500,000 and $600,000.

The Western Australian Government followed the NSW Government approach and announced in their 2004 budget that stamp duty will be eliminated for first home buyers buying properties less than $220,000 (a saving of up to $8,230) or vacant land up to $100,000. [24]

First home buyers in Queensland do not have to pay stamp duty from 1 May 2004 on houses purchased below $250,000. This reform, which is expected to cost around $30 million in its first year, is only available to people over 18 and applies to properties up to $500,000 on a sliding scale. Queensland buyers who pay $300,000 for their first home will now only have to pay the State Government $2,250 in stamp duty giving them a saving of $2,000.

On Tuesday 4 May 2004, the Victorian Treasurer, Mr John Brumby, handed down the 2004-2005 Victorian State Budget. In it he made available to first home buyers over 18 years of age a bonus of $5,000 to all Victorian first home buyers who qualify for the Federal Government $7,000 grant where the purchase price of the property was under $500,000. This State offer expires on 1 July 2005.[25]

All these state initiatives represent a concerted effort to assist first home buyers to enter the housing market. In addition to the Federal Government grant of $7,000 to first home buyers, additional funding of up to $18,000 can be obtained depending on the State and the purchase price of the home. In order to compare these benefits with the tax benefits received by a property investor, an average amount of $12,000 will be used when comparing the funds available to first home buyers with the tax benefits available to property investors.

An appropriate valuation approach in this case would be firstly, to estimate the expected value of tax benefits to a property investor resulting from tax deductions over the holding period for a property and secondly, allow an adjustment for the potential Capital Gains Tax (“CGT”) disadvantage faced by the investor. This adjusted-value could then be compared with the first home buyers’ grant and other State Government benefits, being the standard $12,000 as discussed previously.

Methods for the valuation of a stream of expected cash flows are discussed in numerous texts.[26] There are three crucial components in this process, the:

| (i) | timing of cash flows; |

| (ii) | magnitude of cash flows; and |

| (iii) | opportunity cost (interest rate) for the property investors. |

Since cash flows originate from tax benefits, they are typically included as part of the end of year cash flow. However, property investors using negative gearing can apply for a variation to decrease the amount of tax deducted from their other salary income. As the risk in generating tax savings is minimal, the appropriate discount rate may be very close to the risk-free rate, as the determinants of tax savings, such as the interest on the loan, are highly predictable. The rental income received may be subject to variation as tenant vacancy rates have risen recently, although low vacancy rates in Canberra, Brisbane and Adelaide suggest that there is still a relatively tight rental market ensuring minimal risk. One way to obtain a proxy for discounting of tax savings could be to use the risk free rate earned from low risk investments, such as term deposits, government bonds and AAA corporate bonds. Another means, argued by some authors, has been to use before tax cost of debt as a good approximation for discounting the tax savings generated through interest deductions.[27] However, these arguments are based on the valuation of tax shields generated from borrowings for foreign projects. Since tax savings generated in a foreign country are likely to carry a higher risk than those associated with domestic tax savings, a rate lower than the cost of loan may be more appropriate. Thus, considering the current market rates, the appropriate discount rate could be between 4.5 and 6.5% per annum. We have taken the middle value, namely 5.5% per annum as the proxy for discounting of tax savings.

A surface appraisal would suggest that the tax treatment of capital gains resulting from the sale of a house favours owner-occupiers, since property investors face a tax loss on 50% of the capital gains after adjusting for depreciation and capital allowances and assuming a holding period of more than 12 months. However, the occurrence of this relative disadvantage to property investors is subject to many uncertainties. First, the CGT disadvantage occurs only if the property is sold, thus the investors are in a good position to avoid or minimise the CGT by selling at a point of time that is beneficial from a taxation viewpoint. For example, the potential capital gain could be delayed until the property investor’s marginal tax rate is at a lower rate or even zero. Second, the property investor may sell their property after realising a capital loss from another investment. The capital loss from the other investment could be used to totally offset any capital gain made from the sale of the first investment property, thus resulting in a zero CGT. Third, as there is no obligation for an investor to sell an investment property or a house, the CGT disadvantage may, in many cases, be purely a theoretical exercise. Finally, the achievement of a capital gain is not a certainty; it may in fact be a capital loss. Should this unlikely situation occur, investors may be better off, as the capital loss can be offset against other capital gains made in the current year or against future capital gains.

Therefore the CGT disadvantage may not be such a significant issue under the current property investment scenario in Australia and therefore we have completed our analysis showing scenarios that do not include CGT as well as scenarios that do. Thus, estimating the value of expected tax benefits from negative gearing over a long period should give a good indication of an investor’s competitive position compared to a first homebuyer.

Property investment seminars are also another example of the driving forces behind the popularity of building wealth through investment in residential property. Mostly these seminars are focused on explaining the workings of negative gearing and the resulting weekly/monthly net cost to investors. We attended a free property investment seminar where a case was presented. As shown in Appendix 1, the presenter explained that a median priced property valued at $295,000 can generate net tax deductions of $19,711 (Annual interest payments + associated expenses – rental income). Using this value as a starting point, we calculate the present value of tax benefits for different marginal tax rates over a number of periods (see Table 3). As already explained in Section 3.1, the discounted value calculations are based on a 5.5% discount rate.

∗Discount rate 5.5% per annum; all values in dollars

MTR = Marginal Tax Rate including 1.5% Medicare Levy

ATS = Annual Tax Savings based on annual net rent loss (see Appendix 1)

|

Number of Years

|

10

|

15

|

20

|

25

|

30

|

|

|

$

|

$

|

$

|

$

|

$

|

|

MTR=31.5%; ATS = $6,209

|

46,801

|

62,323

|

74,200

|

83,287

|

90,240

|

|

Impact of 5% compounded decrease

|

36,486

|

44,519

|

49,275

|

52,090

|

53,757

|

|

Impact of 2% compounded increase

|

51,817

|

71,862

|

88,795

|

103,100

|

115,184

|

|

MTR=43.5%; ATS = $8,574

|

4,628

|

86,062

|

102,463

|

115,011

|

124,612

|

|

Impact of 5% compounded decrease

|

0,383

|

61,476

|

68,043

|

71,931

|

74,233

|

|

Impact of 2% compounded increase

|

71,554

|

99,234

|

122,617

|

142,371

|

159,058

|

|

MTR=48.5%; ATS = $9,560

|

72,060

|

95,959

|

114,246

|

128,237

|

138,943

|

|

Impact of 5% compounded decrease

|

56,177

|

68,545

|

75,868

|

80,203

|

82,770

|

|

Impact of 2% compounded increase

|

79,782

|

110,646

|

136,718

|

158,743

|

177,350

|

Appendix 1 assumes a constant tax deduction of $19,711 and incorporates the flat 2.5% building capital allowance (assuming property was constructed after 15/9/1987), depreciation on chattels and amortisation of the loan borrowing costs. The 2.5% building capital allowance can be claimed on the construction cost up to a maximum of 40 years. The depreciation on chattels assuming an average rate of 10% per annum straight line would continue for 10 years whilst the $500 amortisation of the loan borrowing costs would only be claimable for the first 5 years. The accounting fee and travel costs of $500 per annum seem high. We have assumed that the $7,000 depreciation is made up of a:

| 1. | Building capital allowance claim of 2.5% per annum on a construction cost of $160,000. This would allow a claim of $4,000 per annum for the next 40 years. |

| 2. | Depreciation claim of 10% per annum on chattels worth $30,000. This would allow a claim of $3,000 per annum for the next 10 years. |

Therefore considering that there may be exaggeration in the bench mark figures supplied in Appendix 1 and the amount may decrease over time, we have evaluated for the impact of 5% compounded decrease in the annual value of tax benefits. It is evident that all of these values are significantly higher than the first home buyers’ grants/benefits of $12,000 that we are using in our comparison. Our estimates suggest that the relative advantage to wealthy investors on the top marginal tax rate of 48.5% over the longer periods may be more than one hundred thousand dollars where there is no allowance for a compounded decrease. Even for a period of only 10 years and using a 5% compounded decrease, the present value of the tax benefits to the top marginal tax rate property investor is $56,177 which is significantly more than the $12,000 first home buyers’ grants/benefits. Further, the possibility of an increase in tax benefits cannot be ruled out. For instance, it may result from an increase in interest payments due to increases in interest rates or loan refinancing. Thus, an impact of 2% compounded increase is also evaluated showing a present value of the tax benefit to the top MTR property investor of $79,782 for a 10 year period, increasing to $177,350 for a holding period of 30 years.

As discussed previously, there may be a need to consider the CGT effect on the property investor if they sell. Using the data from Appendix 1 and assuming a conservative 5% per annum increase in house prices[28] and a 3% per annum increase in the costs of conveyancing, then the CGT payable at the end of the 10th year would be $54,689 (see Table 4 for calculations).

|

Number of years

|

10

|

15

|

20

|

25

|

30

|

|

Original Cost of Property

|

$295,000

|

$295,000

|

$295,000

|

$295,000

|

$295,000

|

|

Compounded increase in house prices

|

5%

|

5%

|

5%

|

5%

|

5%

|

|

Sale Price after number of years

|

$480,524

|

$613,284

|

$782,723

|

$998,975

|

$1,274,973

|

|

Solicitor's Fee compounded at 3%pa

|

$1,277

|

$1,480

|

$1,716

|

$1,989

|

$2,306

|

|

Agent's Selling Commission at 3%

|

$14,416

|

$18,399

|

$23,482

|

$29,969

|

$38,249

|

|

Net Proceeds from Sale

|

$464,831

|

$593,405

|

$757,525

|

$967,016

|

$1,234,418

|

|

Original Cost of Property

|

$295,000

|

$295,000

|

$295,000

|

$295,000

|

$295,000

|

|

Solicitor's Fee

|

$950

|

$950

|

$950

|

$950

|

$950

|

|

Stamp Duty

|

$13,360

|

$13,360

|

$13,360

|

$13,360

|

$13,360

|

|

Depreciation/ Capital Allowance for 10yrs

|

$70,000

|

$90,000

|

$110,000

|

$130,000

|

$150,000

|

|

Cost base after Depreciation/ Capital Allowance

|

$239,310

|

$219,310

|

$199,310

|

$179,310

|

$159,310

|

|

Calculated Capital Gain

|

$225,521

|

$374,095

|

$558,215

|

$787,706

|

$1,075,108

|

|

Taxable Capital Gain (50%)

|

$112,761

|

$187,048

|

$279,108

|

$393,853

|

$537,554

|

|

Tax on Gain at 48.5%

|

$54,689

|

$90,718

|

$135,367

|

$191,019

|

$260,714

|

|

PV of Tax on Capital Gain discounted at 5.5%

|

$32,017

|

$40,636

|

$46,394

|

$50,092

|

$52,311

|

The magnitude of this taxable capital gain would put (if they were not already) the property investor into the highest MTR and therefore our calculations only show the effect of CGT on the high-income earner. Calculations have also been derived for 15, 20, 25 and 30 years. They show a PV of the CGT attributable to the property investor ranging from $32,017 for 10 years to $52,311 for 30 years. As previously discussed, the impact of a 5% compounded decrease in the annual tax benefits, the scenario of a 2% compounded increase as well as the case where there is no compounded increase or decrease have been included in our analysis incorporating this CGT effect and are reported at Table 5.

|

Number of years

|

10

|

15

|

20

|

25

|

30

|

|

Data from Table 3 for a 48.5% MTR Property Investor ($)

|

|||||

|

No compounded increase/decrease

|

72,060

|

95,959

|

114,246

|

128,237

|

138,943

|

|

Impact of 5% compounded decrease

|

56,177

|

68,545

|

75,868

|

80,203

|

82,770

|

|

Impact of 2% compounded increase

|

79,782

|

110,646

|

136,718

|

158,743

|

177,350

|

|

PV of Tax on Capital Gain from Table 4

|

32,017

|

40,636

|

46,394

|

50,092

|

52,311

|

|

PV of Tax on Capital Gain discounted at 5.5% incorporating no compounded

increase/decrease in annual tax benefits

|

40,043

|

55,323

|

67,851

|

78,146

|

86,632

|

|

PV of Tax on Capital Gain discounted at 5.5% incorporating impact of 5%

compounded decrease in annual tax benefits

|

24,160

|

27,910

|

29,474

|

30,112

|

30,460

|

|

PV of Tax on Capital Gain discounted at 5.5% incorporating impact of 2%

compounded increase in annual tax benefits

|

47,765

|

70,010

|

90,324

|

108,652

|

125,039

|

The worst cast scenario of a high 48.5% MTR property investor incorporating the CGT effect with a 5% compounded decrease in annual tax benefits still reveals a present value to the property investor of $24,160 for 10 years and $30,460 for 30 years for a house originally priced at $295,000. Again all these values are significantly higher than the first homebuyer’s grant/benefits of $12,000 we are using in our analysis. Further, if a 2% compounded increase was used, then the present value for high marginal tax rate property investors would be $47,765 for ten years and $125,039 for thirty years. Compared with the $12,000 first home buyers’ grant/benefit, the property investor in the 2% compounded increase scenario is better off in today’s figures by $35,765 and $113,039 if the property is held for ten years or thirty years respectively.

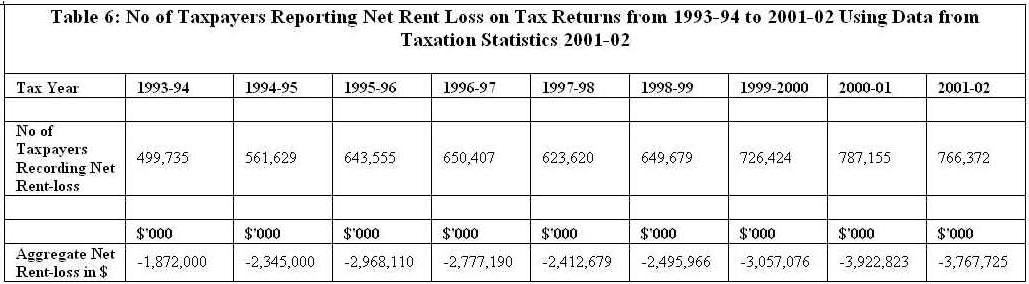

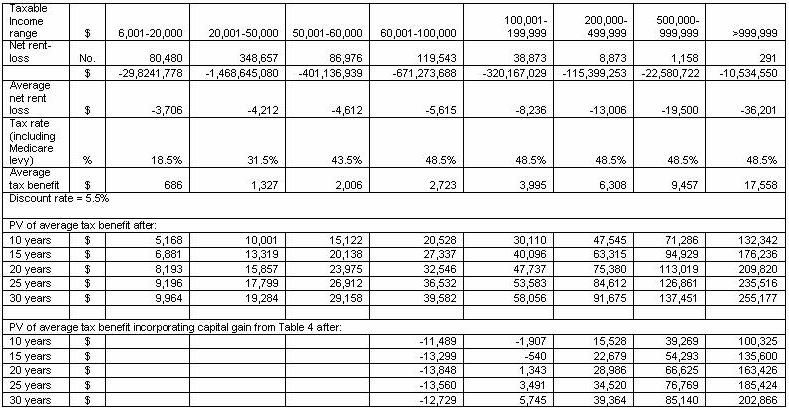

The ATO’s Taxation Statistics 2001-02[29] was employed to obtain statistics regarding the income earned and expenses incurred by property investors. Property investors are required to declare all rental income received and the tax deductions relevant to maintaining the rental property when lodging their individual tax return. This information is reported in five different categories: gross rent; interest deductions; special building write-off; other rental deductions and net rent (gross rent less the sum of other three categories). Statistics from all of these categories have been taken from Taxation Statistics 2001-02, and incorporated in the calculation of the figures reported in Table 6. The table shows an increase of 58% from 499,735 in 1993-1994 to 787,155 in 2000-2001 in the number of property investors reporting “net rent loss”. Simultaneously, the magnitude of the net rent loss has increased by 110%. Although the number of investors reporting a loss and the financial amount dropped marginally in 2001-2002, the number of taxpayers earning in excess of $60,000 who claimed a net rent loss increased from 152,090 in 2000-2001 to 168,738 in 2001-2002. The net loss claims for these taxpayers increased in aggregate from $1,056 million to $1,140 million indicating an increase in taxation benefits to property investors in the highest taxation bracket.

Typically, the tax benefit reaped by an investor with a taxable income of over $1 million is 25.6 times greater than the benefits acquired by investors in the lowest taxable income bracket. Furthermore, assuming no change in tax benefits, the discounted cash flow values presented in Table 7 suggest that the long-term value of tax benefits to high-income investors is lucrative. For example, after 20 years of the 5.5% discounted cash flow, only the investor with a taxable income of less than $20,000 has a PV less than the $12,000 first homebuyer’s grants used as a comparison. These calculations however, have not included the potential CGT in the event of a sale. Although it was argued above that this option may never eventuate, in order to present the most conservative result a CGT of $54,659 after ten years was assumed (see Table 4 and Appendix 1). The PV of the CGT ($32,017) has been included in the analysis at the bottom of Table 7. As the CGT was only calculated at the top MTR, the results are only reported for taxpayers with a taxable income greater than $60,000.

The results of these calculations reveal a present value of tax benefits to the property investor after 10 years of ($1,907), $15,528, $39,269 and $100,325 for those taxpayers on taxable incomes between $100,000 and $200,000; $200,000 to $500,000; $500,000 to $1,000,000; and greater than $1,000,000, respectively. The figures for CGT coming into effect after 15, 20, 25 and 30 years have also been presented. In particular, the present value of the average tax benefit incorporating the mentioned capital gain for a property investor with a taxable income of over $1 million is $202,866 after 30 years. This figure is hardly comparable to the $12,000 received by a first home buyer. As the figures in Table 7 reveal, the tax benefit to high-income property investors are very rewarding. In fact, using our scenario, a CGT of $209,000 would be needed after 10 years for investors in the highest income bracket before the PV of the tax benefit equated to the first home owners’ grants of $12,000. This would imply a capital gain of $862,000 on the original purchase price from our example of $295,000 – an annual increment of 14.4% per annum.

Our analysis suggests that negative gearing offers substantial tax advantages to wealthy property investors and that the first home buyers’ grant/benefits are no match for it. Although negative gearing is not the only cause of the housing affordability crisis, it is a substantial factor in pushing first home buyers out of market. Monetary measures, such as raising interest rates, are more detrimental to owner-occupiers than investors due to investors’ ability to pass on up to 48.5% of any additional costs to taxpayers through their tax deductions.

Low interest rates and the relaxation of lending practices over recent years have added value to the tax advantages associated with negative gearing. Moreover, steadily increasing housing prices and concomitant uncertainties in the capital markets have augmented strong investment growth in the housing sector. It could also be argued that the ascendancy of “get-rich-quick” gurus has stimulated speculation in the housing market. It is hard to understand policy directives that encourage negative gearing in a climate where there are enough other inducements already present within the market to promote housing investment. It may well be time for a reappraisal of investment policy within Australia in order to reduce the current inequities in relation to home ownership. A policy of social justice and fairness would suggest the need of reducing the tax benefits associated with negative gearing, thus reducing the markets’ attractiveness to investors and enabling more first home buyers to fulfill the Australian dream of owning their own home.

Appendix 1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

HERITAGE FINANCIAL GROUP

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

NEGATIVE GEARING WORKSHEET

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Costs

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Property

|

|

$295,000

|

Total Purchase Costs

|

$16,810

|

|

|||

|

Solicitor's Fees

|

$950

|

Less Deposit (if any)

|

$ -

|

|

||||

|

Stamp Duty

|

|

$13,360

|

Funds Required

|

|

$311,810

|

|

||

|

Loan Costs

|

|

$2,500

|

Interest Rate

|

|

6.30%

|

|

||

|

Outgoings

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Annual Interest

|

$19,644

|

Weekly Rental

|

|

$230

|

|

|||

|

Rates

|

|

$700

|

Annual Rental (4% Vacancy)

|

$11,500

|

|

|||

|

Body Corporate

|

$750

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Management Fees

|

$862

|

Total Outgoings

|

|

$22,711

|

pa

|

|||

|

Letting Fees

|

$460

|

Less Rental Income

|

$11,500

|

pa

|

||||

|

Insurance

|

|

$295

|

Shortfall

|

|

$11,211

|

pa

|

||

|

TOTAL OUTGOINGS

|

$22,711

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Tax Deductions

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

Shortfall Balance C/F

|

$11,211

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

Depreciation

|

|

$7,000

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

Loan Cost/Loan Term

|

$500

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

Accountancy

|

|

$500

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

Travel

|

|

|

$500

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total Tax Deductions

|

$19,711

|

|

|||

|

Tax Refund Calculation

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Salary

|

|

$50,000

|

Tax

|

|

|

$12,130

|

|

|

|

Less Tax Deductions

|

$19,711

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

New Salary

|

|

$30,289

|

New Tax

|

|

|

$5,921

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Annual Tax Saving

|

$6,209

|

|

|||

[∗] Senior Lecturer, Department of Accounting and Finance, Monash University.

[∗∗] Honours Student, Department of Accounting and Finance, Monash University.

[∗∗∗] Lecturer, Department of Accounting and Finance, Monash University. We are grateful to Fiona Newton, Joav Rav-On and the anonymous referees for their helpful comments and discussion on earlier versions of this article.

[1] Productivity Commission, First Home Ownership (Report No 28, 2004) 75.

[2] P Weekes, “Home, Sweet 70% Home”, The Age, 5 July 2003, 5.

[3] Consumer Price Index Australia (28 August 2004); available at: http://www.abs.gov.au.ezproxy.lib.monash.edu.au/Ausstats/abs@.nsf/0/3AAA540343A2B4C3CA25688D001C2819?Open.

[4] Weekes, above n 2.

[5] “Australian Social Trends: Housing – Housing and Lifestyle: First Home Buyers” (3 June 2003); available at:

[6] “Housing Feature Article – Recent Trends in Construction and First Home Buyer Finance” (10 May 2002); available at:

[7] C Colebatch, “Why Costello Should Scrap Negative Gearing”, The Age, 8 July 2003, 11.

[8] Victorian Council of Social Services (2003), Submission to the Productivity Commission into first home ownership; available at:

http://www.vcoss.org.au/submissions/First%20Home%20Ownership.doc.

[9] 87 ATC 4813.

[10] Reserve Bank of Australia, Submission to the Productivity Commission into first home ownership; available at:

[11] Lending Finance Australia (August 2003); available at:

[12] Ibid.

[13] A Wood, “We’re Urban Sprawlers, So Don’t Cramp Our Style”, The Australian, 27 April 2004, 11.

[14] “Housing: National Summary Tables” (3 June 2003); available at:

[15] Ibid.

[16] Wood, above n 13.

[17] C Murphy, “Fewer First Home Buyers, But We Are Still Ahead”, Australian Financial Review, 17 April 2004, 4.

[18] C Murphy, “Labor Promise on Housing”, Australian Financial Review, 29 June 2004, 5.

[19] AAP Newsfeed, “Fed: Costello Rules Out Review, Changes to Property Tax”, 23 June 2004.

[20] AAP Newsfeed, “Fed: Democrats Launch $5 Billion Plan for Housing”, 7 April 2004.

[21] J Kaye, “Time to Address Public Housing Crisis”, The Australian, 22 July 2004, 22.

[22] N Pedersen-McKinnon, “Negative Gearing May Lose its Shine”, Australian Financial Review, 30 June 2004, 9.

[23] D Dixon, “Negative Gearing is Here to Stay; Future Benefits Not as Good as in the Past”, The Canberra Times, 1 August 2004, 33.

[24] C Manton, “Stamp Duty Win for First Buyers”, The West Australian, 7 May 2004, 7.

[25] 2004-05 State Budget Information, 11/07/04; available at:

http://www.sro.vic.gov.au/SRO/srowebsite.nsf/taxes%20budget_2004.htm?OpenPage&charset=iso-8859-1.

[26] See, for instance, S Bishop, R Faff, B Oliver and G Twite, Corporate Finance

(5th ed, 2004).

[27] AC Shapiro, Foundations of Multinational Financial Management (4th ed, 2002) 483; and CS Eun and BG Resnick, International Financial Management (2nd ed, 2001) 423.

[28] In the Reserve Bank of Australia’s submission to the Productivity Commission inquiry on first home ownership, a rate of 5% per annum was also used for increase in property values.

[29] Australian Taxation Office, Taxation Statistics 2001-02 (July 2004).

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/JlATax/2005/4.html