Journal of Law, Information and Science

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Journal of Law, Information and Science |

|

BY DR KATE REID*

This article uses a risk management approach to analyse a number of contractual risks that affect businesses that conduct Internet commerce. Collectively, these contractual risks are referred to in this article as the risk that a business through the course of its Internet commerce dealings may become contractually bound to terms unintentionally (“contractual risk”). This contractual risk arises in five contexts in relation to Internet commerce: (i) Where a business’s marketing and promotional activities (whether through the web or by e-mail) constitutes making an “offer” rather than an “invitation to treat”; (ii) Where a business’s purported withdrawal of an “offer” to a customer is precluded because the business’s “offer” has been accepted by a customer; (iii) Where during the course of negotiating the terms of an Internet transaction a “battle of the forms” situation arises such that a customer’s terms override the business’s; (iv) Where the terms of the contract negotiated between a business and a customer are altered by erroneous transmission; and (v) Where the business’s computer software used for conducting Internet commerce is erroneously programmed or malfunctions so it makes or accepts offers in circumstances unauthorised by the business.

Risk management analysis indicates that the risk is a moderate risk, that is, failure to manage this contractual risk could expose a business to considerable loss. A business conducting Internet commerce, however, can take steps to manage this risk using risk management strategies such as those put forward in this article. At a theoretical level this article demonstrates that it is useful and legitimate to use risk management methodology in the context of legal risk. More specifically, in relation to Internet commerce, this article has practical significance as it analyses and provides risk management strategies for dealing with the one of the contractual risks associated with conducting Internet commerce.

There is a perception that Internet commerce gives rise to legal risks to which businesses would not be exposed when conducting offline commerce. Furthermore this gives rise to the belief that the additional legal risks are so great that they constitute a serious impediment to the conduct of Internet commerce. By examining some of these legal risks in detail this article contributes towards determining whether these beliefs are in fact substantiated. This article investigates whether businesses that conduct Internet commerce should be concerned with a number of contractual risks referred to here as the risk that a business through the course of its Internet commerce dealings becomes contractually bound to terms unintentionally (“contractual risk”).

This contractual risk is analysed according to risk management principles, more specifically those set out in Australian Standard 4360 Risk Management. For reasons of space it is not proposed to describe the risk management procedure advocated by Australian Standard in any detail. In general terms, Australian Standard AS/NZS 4360 Risk Management 1999 characterises the risk management process as an iterative process involving the following: (1) establishing the context, (2) identifying risks, (3) analysing the identified risks, (4) evaluating and prioritising the identified risks and accepting those risks evaluated as “acceptable”, (5) treating the remaining risks, (6) monitoring and reviewing the risk management system implemented).

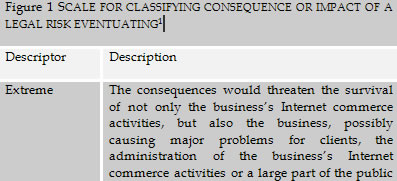

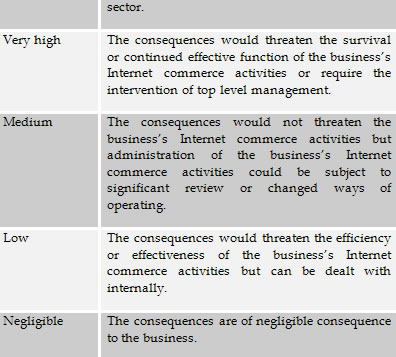

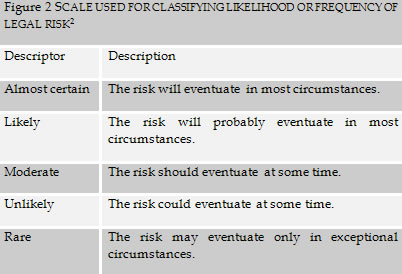

Applying risk management principles in this article involves two steps. The first step involves analysing the contractual risk by reference to three qualitative scales: a scale for classifying the consequences of a risk eventuating and a scale for classifying the likelihood of a risk eventuating. This enables the contractual risk to be further classified against a third qualitative scale for classifying the overall level of risk.

The qualitative scale used for classifying the consequence or impact of a legal risk in this article is as follows:

The qualitative scale used for classifying likelihood of a legal risk in this article is as follows:

Figure 2

SCALE USED FOR CLASSIFYING LIKELIHOOD OR FREQUENCY OF LEGAL

The scale used for classifying the level of risk in this article is as follows:

Figure 3

SCALE FOR LEVEL OF RISK[3]

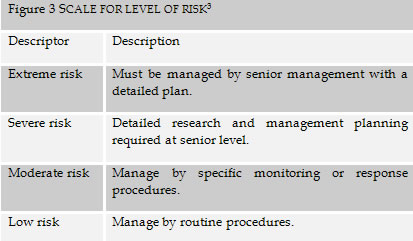

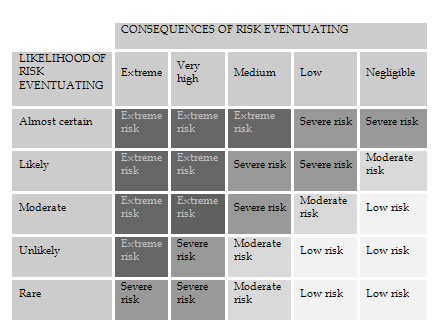

Combining the three scales used in this article for classifying consequence, likelihood and level of risk results in the following matrix:

MATRIX DEPICTING THE SCALES USED IN THIS ARTICLE

The second step involves examining what strategies could be used to manage the contractual risk and evaluating those risk management strategies. Then appropriate risk management strategies are selected.

The risk that a business becomes contractually bound to terms unintentionally arises in five contexts in relation to Internet commerce:

• Where a business’s marketing and promotional activities (whether through the web or by e-mail) constitutes making an “offer” rather than an “invitation to treat”;

• Where a business’s purported withdrawal of an “offer” to a customer is precluded because the business’s “offer” has been accepted by a customer;

• Where during the course of negotiating the terms of an Internet transaction a “battle of the forms” situation arises such that a customer’s terms override the business’s;

• Where the terms of the contract negotiated between a business and a customer are altered by erroneous transmission;

• Where the business’s computer software used for conducting Internet commerce is erroneously programmed or malfunctions so it makes or accepts offers in circumstances unauthorised by the business.

In order to determine the likelihood of risk it is necessary to consider these scenarios in some detail.

A business risks being contractually bound to terms which it cannot or would prefer not to fulfil if it fails to take into account the legal distinction drawn between making “offers” and “invitations to treat” when undertaking its marketing and promotional activities on the Internet.

An “offer”, in legal terms, is a proposal of the terms on which a business seeks to transact which, if accepted by a customer, will become contractually binding on the business. If a customer accepts an “offer” that is made on the Internet by a business (eg on a business’s web site, through e-mail or on a bulletin board) the business will be contractually bound to the terms of that “offer”. A business may therefore find that it is contractually bound to terms to which it would prefer not to be bound. For example, a business may find itself contractually bound to meet orders that, due to overwhelming demand, it cannot meet. Alternatively, where an “offer” is made on a business’s web site, and the business fails to update its web site, the business may find itself contractually bound to sell a product or service at the out of date purchase price specified on the web site.

In contrast, the term “invitation to treat” refers to a proposal, which if responded to by a customer, is not contractually binding. Rather, an “invitation to treat” is an offer to negotiate, or an offer to receive offers.[4] Thus, where a customer orders a business’s goods or services in response to a business’s “invitation to treat”, the business is entitled to accept or reject the order.

Whether a business’s marketing and promotional activities on the Internet constitute making an “offer” or an “invitation to treat” is determined by examining the objective intention of the business’s conduct.[5] Thus, a business will be considered to have made an “offer” if a reasonable person would believe that an “offer” was being made. Such “offer” will be contractually binding on a business if a customer responds to it with a genuine belief that the business has made an “offer”.

It is likely that the courts will apply the principles regulating analogous off-line activities when determining whether a business’s marketing and promotional activities on the Internet constitute making an “offer” or an “invitation to treat”. Thus, if a business’s efforts at soliciting commerce on the Internet is analogous to the issue of circulars and general advertisements (Spencer v Harding [1870] UKLawRpCP 55; (1870) LR 5 CP 561; Re Mount Tomah Blue Metals Ltd (in liq) [1963] ALR 346) or a display of a business’s goods in a store (Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain v. Boots Cash Chemists (Southern) Ltd [1953] EWCA Civ 6; [1953] 1 QB 401), it is probable that such activity will constitute making “invitations to treat”.

It should be noted, however, that it does not ensue that every brochure and catalogue, or a display of goods constitutes making an “invitation to treat”. It is still relevant to examine the objective intention of a business’s conduct. Thus, in the classic case of Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Co [1893] 1 QB 256 it was held that whilst, in general, brochures and advertisements constitute “invitations to treat” they could constitute “offers” if to a “reasonable man” they signified an intention to be contractually bound should a customer respond to them by purchasing the goods (or services) advertised.

Thus, a business’s activities on the Internet, whether they be by means of a web page, or by e-mail, will constitute making an “offer” if those activities would appear to a reasonable person to signify an intention to be contractually bound if a customer responds. Accordingly, text in a business’s web page or e-mail that states, for example, that the first two thousand sales of a business’s goods or services will enjoy a discount of 25% will probably constitute an offer. On the other hand, the fact that a business’s web page or e-mail uses the word ‘offer’ does not necessarily mean that the business is making an “offer” as the use of the word ‘offer’ is not conclusive.[6]

It is relevant to note that under the United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods 1980 (“CISG Convention”), whose provisions have been adopted as law in each State and Territory,[7] there is a presumption under Article 14(2) that when a business solicits commerce from unspecified customers such activity is considered to constitute an invitation to treat. Thus, in relation to Internet transactions governed by the CISG Convention (basically transactions with customers in countries who have adopted the Vienna Convention) a business’s activities on the Internet are likely to be presumed to be invitations to treat.

It is difficult to definitively state here what the likelihood of this scenario eventuating is. It is concluded here that this scenario could eventuate at some time and this corresponds with the descriptor unlikely.

Where a business’s marketing and promotional activities (whether by means of e-mail or a web site) constitute the making of an “offer” in legal terms, a business is entitled at law to withdraw its “offer” at any time up until acceptance of the “offer” by a customer. Depending on whether the postal rule applies to acceptances made on the Internet, however, a business may find that it is precluded from withdrawing its “offer” because the “offer” has been accepted by a customer, even when the customer’s acceptance has not actually been received by the business (eg. the customer e-mailed an acceptance, but due to a delay occurring during transmission the acceptance of a business’s “offer” was not actually received by the business at the time the business sought to withdraw its “offer”).

The general principle governing the calculation of the time at which an acceptance takes place is that acceptance takes place when it is actually received by party that makes the “offer”. Where acceptance is made by post, however, the general rule is replaced with the postal rule. The postal rule provides that acceptance will be deemed to have taken place at the time the acceptance is posted. How the courts will characterise the communication of an acceptance through the Internet will determine a business’s exposure to the risk that it cannot withdraw an “offer” it has made to a customer even though the customer’s acceptance has not actually been received. If the postal rule applies to acceptances communicated through the Internet a business would be precluded from withdrawing its “offer” once a customer had communicated acceptance of the business’s “offer” even if the acceptance had been lost during transmission.[8] Acceptances made by a business in the context of Internet commerce are likely to be effected either through conduct (for example, a business will accept a customer’s “offer” by delivering the goods or services ordered by the customer) or through communicating acceptance to the customer through the Internet (such as by e-mail, or where the customer has ordered the business’s goods or services from the business’s web site, a web page generated by the customer clicking on a button or hypertext to signify the customer’s “offer” to transact with the business). Communicating through the Internet is not always perfect and it is not unusual for an Internet communication (whether by means of e-mail or on the web) to be delayed or even lost, even when the route the communication has taken is relatively uncomplicated:

Assume that the gap between deemed dispatch and deemed receipt is as narrow as possible. This could be because neither the offeree nor the offeror uses remote servers or intermediaries or because dispatch is deemed to take place only at the departure of the message from the offeree’s Internet access provider’s server and receipt is deemed to be at the remote server of the offeror. It is still the case that there is as yet no guarantee when or if an e-mail will arrive. There is no certainty over the route of the e-mail or even that all of the e-mail will take the same route over the packet-switched network.[9]

A situation could therefore arise where a business communicates its acceptance of a customer’s “offer” through the Internet (either by e-mail or, through the business’s web site) but, because its acceptance was delayed through transmission, the acceptance was not actually received by the customer prior to the transmission by the customer of a withdrawal of “offer”. Whether a customer is nevertheless contractually bound to the Internet transaction depends on whether the postal rule governs acceptances made through the Internet.

The postal rule provides that where an acceptance is made by post, acceptance is effected at the time the acceptance is posted. If acceptances communicated through the Internet are governed by the postal rule, a business’s acceptance of a customer’s “offer” would be effective at the time the acceptance was communicated. The fact that the acceptance was delayed or not received by the customer would be irrelevant and a customer would be precluded from withdrawing the customer’s “offer”. The postal rule, however, does not usually apply when an acceptance is communicated through an instantaneous form of communication: Brinkibon Ltd v. Stahag Stahl Und Stahlwarenhandelsgesellschaft Mbh [1983] 2 AC 34.[10] In such instances, the acceptance is effected only when it has been received. Acceptances governed by the instantaneous rule include acceptances communicated by telex[11] and facsimile.[12] If the instantaneous communication rule were to apply in relation to Internet commerce, an acceptance communicated by a business by means of the business’s web page would take place when it was displayed by the customer’s web browser.

Presently only the Commonwealth has provided legislative guidance as to whether an acceptance communicated on the Internet is governed by the postal rule or the instantaneous communications rule and there is no case law that has directly considered this issue. As will be discussed in more detail below, s 14 of the Electronic Transactions Act 1999 (Cth) provides that the postal rule does not apply to Internet transactions governed by Commonwealth law. In relation to all other Internet transactions it is necessary to consider how the courts are likely to treat acceptances communicated through the Internet. Several arguments have been made in the literature for the postal rule to apply to acceptances communicated through the Internet, or at least to acceptances communicated by means of e-mail.[13] This view is based on the argument that an acceptance communicated through the Internet is more analogous to an acceptance made by letter than an acceptance communicated by means of an instantaneous form of communication and therefore it is more appropriate for the postal rule to apply[14] at least in circumstances where the recipient has access to e-mail through an Internet service provider.[15] In other words, the argument is that e-mail is not instantaneous:

Despite common belief, the process [of transmission of an e-mail] does not take place in a substantially instantaneous manner. Rather, it will typically take minutes, hours, or in some cases, days. Perhaps what creates confusion is the true substantial instantaneousness of intrasystem messages, which do not involve the Internet, or the occasional transmission of an Internet e-mail message in a substantially instantaneous manner. Or perhaps the cause of confusion is the substantially instantaneous nature of message transmission as the message passes through the wires themselves. But often overlooked are the “stops” that the message makes along the way, at the various servers and nodes that process it, breaking it up into pieces and reassembling it, or redirecting it to a less congested portion of the Internet, or holding it until other messages are received, for a simultaneous, periodic dispatch. Further, one of the stops may be inoperative, causing the message to be delayed or never received at all.[16]

The alternative view is that Internet communications, including e-mail constitute an instantaneous form of communication. Notwithstanding the opposing view expressed, particularly in relation to e-mail, it is submitted that the instantaneous communication rule is the correct rule to apply in relation to acceptances communicated on the Internet. The similarities between acceptances communicated on the Internet and acceptances communicated by means of facsimile machine are much greater than the similarities between acceptances communicated on the Internet and acceptances communicated by way of post (For example, both forms of communication are electronic and delivery is usually instantaneous although there are circumstances where delivery can be delayed due to technical problems or because the equipment for receiving a communication was not turned on or checked by the recipient). Furthermore, the argument put forward by commentators in favour of the postal rule has only been raised relation to e-mail. There has been no suggestion that the postal rule should apply to other forms of Internet communication such as a form on a business’s web page. If the courts were to find that acceptances communicated by e-mail were subject to the postal rule but acceptances communicated through the web were subject to the instantaneous communication rule, an inconsistent outcome would arise. This would be particularly so if the New Zealand Law Commission approach were taken whereby e-mails received where the recipient had a direct and immediate access to e-mail would be governed by the instantaneous rule but e-mails where the recipient accessed e-mail through an Internet service provider would be governed by the postal rule. For reasons of consistency, too the instantaneous rule should be applied to all forms of Internet communication.

Also, as indicated by Lord Wilberforce in Brinkibon and by Justice Cohen in the NSW Supreme Court case NM Superannuation Pty Ltd v Baker [1927] 7 ACSR 105 the instantaneous communication rule can accommodate instances where an acceptance has not been accessed by a recipient because, for example, the acceptance was communicated by e-mail and it was received by the recipient’s mail server outside of business hours. Lord Wilberforce in Brinkibon recognised that such instances could arise in the context of communications made by telex. He considered that the time at which acceptance takes place in such instances would depend on the intentions of the parties, by reference to business practices and in some cases a judgment as to where the risks should lie:

The senders and recipients may not be the principals to the contemplated contract. They may be servants or agents with limited authority. The message may not reach, or be intended to reach, the designated recipient immediately: messages may be sent out of office hours, or at night, with the intention, or upon the assumption, that they will be read at a later time. There may be some error or default at the recipient's end which prevents receipt at the time contemplated and believed in by the sender. The message may have been sent and/or received through machines operated by third persons. And many other variations may occur. No universal rule can cover all such cases: they must be resolved by reference to the intentions of the parties, by sound business practice and in some cases by a judgment where the risks should lie.[17]

In NM Superannuation Pty Ltd which was concerned with the time at which a notice transmitted by means of facsimile machine was received, Justice Cohen took the view that although ordinarily receipt of a communication transmitted by facsimile will be taken to be at the time the communication was received by the recipient’s facsimile machine, there may however be circumstances, such as where no person was able to receive the communication at the time the recipient’s facsimile machine received the communication where this assumption will be displaced:

In my opinion it is reasonable to assume that if a fax machine has been kept switched on then it is available for the purpose of receiving letters or other communications on it. That amounts to receipt by the trustee in that it had made and kept available the means of documents being received by it. In any case there is no reason why I should assume that the trustee through its employees or agents was not in its office at 5.22 pm on 30 June 1989 or on any other day in the ordinary course of its business. I cannot take judicial notice that people are not normally at work between 5 pm and 5.30 pm and there is no evidence which would suggest that the trustee through its representatives was not present at that time. It may well be in appropriate circumstances that evidence could be given that notwithstanding that a facsimile machine is left in operation there was nobody in the office to receive the messages until the following day but that is not the case here.[18]

Accordingly, it is concluded that the common law position in the event of a dispute as to the time at which a customer received a business’s acceptance should be that the instantaneous rule governs acceptances communicated through the Internet.

As for when an instantaneous communication is deemed to be received it is likely that the courts will be guided by Lord Wilberforce in Brinkibon and Justice Cohen in NM Superannuation and hold that, as with telexes and facsimiles, acceptance will generally be deemed to have taken place at the time when the business’s acceptance was received by the customer’s equipment that receives Internet communications (for example, in relation to acceptances made by way of e-mail, the customer’s e-mail server and in relation to web communications, the customer’s web browser). Only where a customer can bring evidence to prove that it was not possible, at the time the acceptance was received, for the customer to access the communication containing the business’s acceptance, will a court consider deeming that acceptance took place at a later time.

Section 14 of the Electronic Transactions Act 1999 (Cth) provides that the time of receipt of an Internet communication is, where the business has designated an information system for the purpose of receiving Internet communications, the time when the Internet communication enters that information system, unless otherwise agreed between the sender and the recipient of the Internet communication. Where the business has not designated an information system for the purpose of receiving Internet communications then, unless otherwise agreed between the sender and the recipient of the electronic communication, the time of receipt of the electronic communication is the time when the electronic communication comes to the attention of the recipient. Thus, the postal rule does not apply to Internet transactions governed by Commonwealth law and therefore in relation to Internet transactions governed by Commonwealth law the risk that a business’s purported withdrawal of an “offer” to a customer is precluded because the business’s “offer” had been “accepted” (but not actually received by the business) could not arise.

Further, if the Electronic Commerce Framework Bill (Vic) is enacted, the postal rule will not apply to Internet transactions governed by Victorian law. Clause 7(3) of the Electronic Commerce Framework Bill (Vic) provides a presumption that acceptance is deemed to have taken place when the Internet communication containing the acceptance has entered a computer system under the control of the business (that is, the Internet communication containing the acceptance had actually entered the computer system of the business). Should the Electronic Commerce Framework Bill (Vic) be passed, it is unlikely that, in relation to Internet transactions governed by Victorian law, this risk would eventuate, as acceptance would not be deemed to have taken place until it had entered a computer system under the control of the business (that is, the Internet communication containing the acceptance had actually entered the computer system of the business).

It is relevant to note also the effect of the United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods 1980 (“CISG Convention”) whose provisions have been adopted as law in each State and Territory.[19] Under Australian law, the provisions of the CISG Convention operate in relation to the sales of goods by Australian businesses to customers in countries who have adopted the Vienna Convention. Article 18(2) of the CISG Convention effectively provides that acceptance is received at the time it reaches the receiving party. In other words the postal rule does not apply to transactions governed by the CISG unless otherwise agreed by the transacting parties or there is usage or custom to that effect.[20] Article 24 also confirms that the postal rule does not apply in relation to acceptances governed by the CISG, providing that an acceptance is received when it is made orally to the recipient, at the time it was made, or when it is delivered by any other means to the recipient’s place of business or mailing address or in the event of neither being present, the recipient’s habitual residence.

To conclude, if a business’s marketing and promotional activities on the Internet cannot be construed as making an offer this fact situation will never arise. However, as noted earlier, it is possible that a business’s marketing and promotional activities on the Internet could constitute the making of an “offer”. It is suggested here that the common law position is that the postal rule does not apply to Internet communications. Therefore a scenario where a withdrawal of an “offer” to a customer is precluded because the business’s “offer” has been accepted by a customer is not likely to arise. Further, in relation to transactions governed by the Commonwealth Electronic Transactions Act 1999 (Cth) and the Commerce Framework Bill (Vic), if enacted, the effect will be that the postal rule will certainly not apply to transactions governed by such legislation. It is concluded therefore that the likelihood of this fact situation eventuating is rare, that is the scenario would eventuate only in exceptional circumstances.

The term “battle of the forms” refers to a situation that occurs when an offer to do business made by one party on terms, often printed on a form provided by that party, is purportedly accepted by the other party subject to qualifications, also often manifested in a form, but whose effect in law is to reject the first party’s offer and to replace the first party’s offer with a counter-offer. In effect, the relationship between the parties is reversed so that the second party becomes the party who is offering to do business, which the first party can elect to accept or reject.[21] A situation can occur, in such circumstances, where the parties believe that a contract has been formed whereas according to law there is no contract; rather the existence of two offers. Where however, the parties have proceeded to do business with each other even though their exchanges indicate conflicting views of the terms of the contract, the courts have inferred that acceptance was made by conduct[22] and accordingly the terms of that contract reflect the terms put forward in the last counter-offer: Butler Machine Tool Co Ltd v Ex-Cell-O Corp (England Ltd) [1979] 1 WLR 401. The courts have held, however, that the rule that an acceptance that does not reflect an offer constitutes a counter-offer does not apply where the purported acceptance reflects simply a paraphrase of the terms made in the offer.[23]

It should be noted that where a business contracts with an overseas customer whose country has adopted the United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods, the opportunities for a “battle of the forms to arise” are limited in relation to contracts for the sale of goods. Article 19 of CISG, which all States and Territories have adopted,[24] and which applies to all non-consumer sales of goods by Australian businesses to customers whose country has adopted the CISG, provides that an acceptance that modifies the terms of an offer of a customer will not constitute a counter-offer, provided that the qualifications of the second party do not materially alter the offer. Under the CISG, terms that alter the terms of an offer materially include terms relating to the ‘price, payment, quality and quantity of the goods, place and time of delivery, extent of one party’s liability to the other or the settlement of disputes’.[25] The rule set out in Article 19 is subject to the right of the first party to object to such an acceptance.[26] Where no objection is made by the first party the terms of the contract include the terms set out in the first party’s offer and the modifications contained in the acceptance.[27]

In conclusion, a ‘battle of the forms’ type situation is conceivable in the context of Internet commerce in relation to business-to-business Internet transactions. Internet transactions between businesses are more likely to involve negotiations as to terms than Internet transactions between a business and consumers, which are commonly conducted solely on the terms of the business. This scenario is therefore categorised as unlikely that is it could eventuate at some time.

It is possible that during the course of negotiations conducted through the Internet that one party makes an “offer” to another and the terms made in the “offer” are altered due to erroneous transmission. For example, an “offer” made by a business by means of e-mail to a customer may be altered due to an erroneous transmission of the e-mail (this could occur due to malfunction in the e-mail software or due to breakdown of transmission on the Internet). A situation could arise where an altered message received by a customer is nevertheless comprehensible as an “offer” and is consequently accepted by the customer in the belief that it represents the business’s “offer”. This raises the question: would a business in such circumstances be contractually bound to the altered terms? Should such circumstances arise, the situation could be characterised by the courts as a mutual mistake. That is, the courts would find that each party was mistaken about the other's intention, with neither realising that the other was mistaken.[28] In determining whether a contract has been formed in such circumstances, the courts will apply an objective test, by enquiring whether a reasonable observer would have concluded that the party against whom the contract is sought to be enforced had intended to enter into the Internet transaction on those terms claimed by the party seeking to enforce the contract. It is likely that in such circumstances the courts would find that there is no contract because there is no acceptance of what is offered.

In conclusion, this risk will only ever arise where a business conducts negotiations with its customers as to the terms on which it is prepared to transact. Many Internet transactions are conducted solely on terms specified by the business such as in instances where a business displays or provides a hypertext link to its terms on a web page or where a business e-mails its customer the terms on which it is prepared to transact, on the basis that failure to agree to such terms will result in the business refusing to transact with the customer. In addition, the erroneously altered communication needs to have been altered in such as way so as to appear to be making an intelligible “offer” to the receiving party. This fact situation seems unlikely to commonly arise and therefore is categorised as rare, that is the fact situation would eventuate only in exceptional circumstances.

Typically, the computer software used by businesses to conduct Internet commerce is pre-programmed to make or accept offers when certain circumstances occur such as when a customer has completed an on-line order form and provided payment details that have been authorised by the customer’s card provider. If the computer software is incorrectly or erroneously programmed to make or accept offers in circumstances that have been unauthorised by the business then the business faces the risk of being contractually bound to an Internet transaction to which it was not intended. At law it is likely that the business will be held contractually bound to any such Internet transactions that were entered into, notwithstanding that the transaction was not authorised by the business, on the basis of agency principles. This is because the offer or acceptance made by the business’s computer software is likely to be considered to constitute an offer made or accepted by an electronic agent of the business, which will be contractually binding on the business, provided that the offer or acceptance could be regarded as falling within the actual or ostensible authority of the business.[29] It is clearly not possible to definitively state what is the likelihood that a business’s computer software used for conducting Internet commerce is erroneously programmed or malfunctions so it makes or accepts offers in circumstances unauthorised by the business. It seems reasonable to conclude that this fact situation would eventuate only in exceptional circumstances and therefore it should be categorised as rare.

Of the scenarios discussed above that could give rise to the risk that a business becomes contractually bound to terms unintentionally two were categorised as unlikely: Where a business’s marketing and promotional activities (whether through the web or by e-mail) constitutes making an “offer” rather than an “invitation to treat”; Where during the course of negotiating the terms of an Internet transaction a “battle of the forms” situation arises such that a customer’s terms override the business’s.

The other three scenarios were categorised as rare: Where the terms of the contract negotiated between a business and a customer are altered by erroneous transmission; Where the business’s computer software used for conducting Internet commerce is erroneously programmed or malfunctions so it makes or accepts offers in circumstances unauthorised by the business; Where a business’s purported withdrawal of an “offer” to a customer is precluded because the business’s “offer” has been accepted by a customer.

Taking a conservative approach the most appropriate descriptor for this legal risk is unlikely.

The loss that a business would incur if this contractual risk eventuated would be the cost associated with being contractually bound to an Internet transaction on terms that the business cannot or would rather not fulfil. In such circumstances, if the business failed to fulfil its contractual obligations the business would be liable for breach of contract. Under contract law, the measure of damages payable to a plaintiff for breach of contract is the amount of money necessary to place the innocent party (plaintiff) in the position he or she would have occupied if the contract had been performed.[30] Thus, where a business is selling products or services to a consumer through the Internet the amount of damages would, at the very least, be the cost to the consumer of obtaining the products or services purchased from the business elsewhere. Where a business is engaged in business-to-business Internet commerce the amount of damages payable could be considerable as there is greater scope for a plaintiff to establish that, not only should the plaintiff be compensated for having to obtain the business’s services or products elsewhere, but that the plaintiff should be compensated for any losses incurred by the plaintiff resulting from the business’s breach of contract, such as the plaintiff’s inability to meet a deadline for a contract with a third party that relied on the defendant business meeting its contractual obligations.

If, on the other hand a business performed its contractual obligations, the consequences if this risk eventuated would be that the business could incur loss, if to perform the contractual obligation was not profitable or resulted in reduced profits. Providing a generic analysis of the consequence of this risk is difficult. It is suggested that the consequences discussed are unlikely to threaten the business’s Internet commerce activities but would cause the business’s Internet commerce activities to be subject to significant review or changed ways of operating. On a conservative analysis of the consequence of this risk, this risk constitutes a medium risk.

As discussed above, the consequence of the risk that a business becomes contractually bound to terms unintentionally depends on whether the business chooses to perform a contract it would rather not fulfil or to pay damages for breach of contract. On a conservative analysis of the consequence of this risk, this risk constitutes a medium risk. The likelihood of this risk eventuating was assessed as being unlikely.

As the consequence of this risk is medium and the likelihood of risk is unlikely the level of risk is moderate. The evaluation of this legal risk is depicted in table form on the facing page:

Step 2 first involves considering what strategies are available for managing the contractual risk.

The following risk management strategies could be used to manage this contractual risk:

The risk faced by a business of making “offers” instead of “invitations to treat” and as a result being bound to contractual terms which it cannot or would prefer not to fulfil is a risk which a business can avoid quite simply by adopting the risk control technique of scrutinising its marketing and promotional activities on the Internet and ensuring that they cannot reasonably be understood as making “offers” unless it is so intended by the business.

THE RISK THAT A BUSINESS BECOMES CONTRACTUALLY BOUND TO TERMS UNINTENTIONALLY

|

Consequence ratinga

|

Likelihood ratingb

|

Level of riskc

|

Risk priority (level #)

|

|

|

The loss that a business would incur if this risk eventuated would be the

cost associated with being contractually bound to an Internet

transaction on

terms that the business can’t or would rather not fulfil. In such

circumstances, if the business failed to fulfil

its contractual obligations the

business would be liable for breach of contract. Under contract law, the measure

of damages payable

to a plaintiff for breach of contract is the amount of money

necessary to place the innocent party (plaintiff) in the position he

or she

would have occupied if the contract had been

performed[31]. Thus, where a

business is selling products or services to a consumer through the Internet the

amount of damages would, at the very

least, be the cost to the consumer of

obtaining the products or services purchased from the business elsewhere. Where

a business

is engaged in business-to-business Internet commerce the amount of

damages payable could be considerable as there is greater scope

for a plaintiff

to establish that, not only should the plaintiff should be compensated for

having to obtain the business’s

services or products elsewhere, but that

the plaintiff should be compensated for any losses incurred by the plaintiff

resulting from

the business’s breach of contract, such as the

plaintiff’s inability to meet a deadline for a contract with a third party

that relied on the defendant business meeting its contractual obligations. If,

on the other hand a business performed its contractual

obligations, the

consequences if this risk eventuated would be that the business could incur

loss, if to perform the contractual

obligation was not profitable or resulted in

reduced profits.

|

medium

|

unlikely

|

moderate

(must be treated)

|

level 3

|

A risk control strategy is the incorporation by a business of a contractual term that is based on Article 15(a)(ii) of the UNCITRAL Model Law on Electronic Commerce, such that acceptance of a business’s “offer” is deemed to take place when the Internet communication accepting the business’s offer is retrieved by the business (regardless of whether the business has a designated information system). This would minimise the risk that a business is precluded from withdrawing an offer notwithstanding that the business has not actually received communication of acceptance of its offer.

An alternative risk control strategy is for the business to include as a term of any transaction it enters into with its customers a term that reproduces or replicates a strategy used in relation to contracts effected through Electronic Data Interchange, in particular clause 10.2 of the Tradegate ECA Model EDI Trading Agreement. This clause effectively specifies that a transaction entered into by a business and a customer is governed by the instantaneous rule.

Electronic Data Interchange (“EDI”) is a procedure by which the computers of transacting parties can exchange standardised data. A common EDI use is inventory replacement whereby orders for stock are automatically generated by a business’s computer to the computer of the business’s supplier (often via a third party) according to the number of sales of the relevant stock made by the business. To ensure that the data exchanged through EDI is “readable” by the receiving computer, the data must be structured into a standardised form.

Parties intending to transact through EDI may choose to enter into a trading partner agreement. A trading partner agreement usually sets out the obligations of each party and clarifies any legal uncertainties, including contractual uncertainties, that may be associated with contracting through EDI. Several model trading partner agreements have been developed by national and international bodies. Those provisions of the model trading partner agreements that clarify the contractual uncertainties associated with EDI may be suitable for adoption as risk management strategies by businesses conducting Internet commerce. For example, clause 10.2 of the Tradegate ECA Model EDI Trading Agreement (Short Form Agreement) provides that acceptance takes place when an EDI message constituting an offer is made available to the information system of the receiver:

Unless otherwise agreed, a contract made by EDI will be considered to be concluded at the time and the place where the EDI message constituting the acceptance of an offer is made available to the information system of the receiver.

A clause such as this, that in effect applies the instantaneous communication rule to acceptances, if incorporated by a business conducting Internet commerce in its transactions with its customers would minimise the risk that a business is precluded from withdrawing an offer notwithstanding that the business has not actually received communication of acceptance of its offer from the customer. This is because acceptance of a business’s “offer” would be deemed to take place when a customer’s acceptance of the business’s offer is made available to the information system of the business and not when the acceptance is sent by a customer. Such term could be incorporated by a business e-mailing this term (and any other term that the business wishes to incorporate) to the customer with whom the business is transacting, or, if the business is conducting commerce on the web, the term could be displayed on the business’s web page. The principles governing incorporation of standard terms, discussed later in this chapter, would also need to be considered in order to ensure that such term is contractually binding on a customer.

It should be noted that whilst a risk management strategy may be to incorporate some provisions of EDI model trading partner agreements, the use of trading partner agreements themselves to incorporate these provisions are not, in general, suitable in the context of Internet commerce. The concept of trading partner agreements, which are signed off-line before parties begin transacting with each other are not appropriate in the context of Internet commerce where a business is likely to seek to conduct commerce with customers with whom it does not necessarily have an ongoing trading relationship. Also, if trading partner agreements are required to be signed off-line this would introduce an element of delay and a business would risk losing potential customers by imposing a requirement to enter into a trading partner agreement in order to conduct Internet commerce with the business.

A risk control strategy for a business affected by this risk is to refuse to transact with a customer except under the business’s terms. For example, communication with a customer before the customer has signified acceptance of a business’s terms (eg by clicking on a button or icon with the words “accept” on the business’s web page containing the business’s terms of business) could be avoided before an order can be made by a customer. This would eliminate the possibility of pre-existing “offers” being made by a customer, giving rise to a battle of the forms situation. Alternatively, a customer can be prevented from completing an order (eg typing in or selecting order details from an order form on a web page that is then transmitted to the business) until the customer has signified acceptance of the business’s terms (eg by clicking on a button to signify acceptance of the terms displayed on the business’s web page), the rejection of which result in the customer being prevented from further progressing with the transaction.

In relation to business-to-business Internet commerce, where variations of terms are more likely to be sought by customers and acceded to by a business, a prudent risk control strategy is for the business to ensure that a mechanism is put in place such that if terms upon which the parties agree to transact can and are varied by a customer that subsequent to any variation accepted, a follow-up communication is transmitted to the customer confirming the varied term and reiterating all other terms on which the business is prepared to transact.

A risk control strategy is to require all customers’ communications with the business to be “signed” with a digital signature. For reasons of space it is not possible to discuss digital signatures in any detail here. It is relevant here to note that their use provides a means for detecting whether an Internet communication received by a party differs from that which was transmitted by the party sending the Internet communication.

Another risk control strategy is for the business to incorporate as a contractual term with its customers a term that reproduces or at least replicate the effect of Article 13(5) of the UNCITRAL Model Law on Electronic Commerce. Article 13(5) of the UNCITRAL Model Law on Electronic Commerce specifically precludes reliance on an Internet communication received by a party where that party knew or should have known that the Internet communication was erroneous:

Where a data message is that of the originator or is deemed to be that of the originator, or the addressee is entitled to act on that assumption, then, as between the originator and the addressee, the addressee is entitled to regard the data message as received as being what the originator intended to send, and to act on that assumption. The addressee is not so entitled when it knew or should have known, had it exercised reasonable care or used any agreed procedure, that the transmission resulted in any error in the data message as received.[32]

If a business incorporated terms in its transactions with its customers that had the same effect as Article 13(5) it would minimise the risk of the business being contractually bound to a term that was altered during transmission.

A risk transfer strategy is to outsource the production of the software used to conduct Internet commerce to a third party software developer or to purchase an off the shelf Internet commerce software package. Whilst this does not remove the risk that a business will be contractually bound to an Internet transaction on terms to which it did not intend to be bound by, the business may be able to recover the losses it has incurred as a consequence of wrongly programmed software from the third party developer, if the business ensures that a term of the software development or acquisition agreement provides for the recovery of losses incurred by the business as a consequence of an error or malfunction in the Internet commerce software. Furthermore, the business will need to ensure that it does not contract out of its rights to sue for negligence in the event that the software is wrongly programmed.

Again the frequency of such risk arising can be minimised through using the risk control strategy of incorporating as a contractual term with all customers a term that reproduces or at least replicates the effect of Article 13(5) of the UNCITRAL Model Law on Electronic Commerce. As noted earlier, Article 13(5) precludes reliance by a party on an Internet communication received by the party which the party knew or ought to have known was erroneous.

Step 2 then involves evaluating the risk management strategies identified and then selecting appropriate risk management strategies. According to risk management principles because the consequence of this contractual risk is medium, and the likelihood of this risk is unlikely, this risk is the type of risk that a business should retain. Risk retention involves generating funds from within a business to pay for losses as opposed to transferring the risk, such as by insurance.To retain this legal risk is also consistent with another guiding principle which is that a business should only retain risks over which it has control. However, according to risk management principles this risk is the type of risk that requires management by a business. That is, a business should consider implementing one or more of the strategies put forward in order to minimise this legal risk. So which risk management strategies should a business implement? Based on an assessment that implementation is not expensive and that implementation will significantly minimise this legal risk, a business should adopt all except two of the risk management strategies discussed. The two risk management strategies excepted are the use of digital signatures and the outsourcing of the production of the software used to conduct Internet commerce to a third party. It is not, however, suggested that these two risk management strategies are not cost effective. Rather, given that the implementation of these two strategies will involve a cost to the business, it will be necessary for a business to weigh the cost of implementing these two options against the benefits of implementing these strategies before deciding whether to adopt these risk management strategies. Depending on the circumstances of a particular business, it may or may not be appropriate to implement these two options. The risk management strategies put forward and the recommended risk management strategies are set out in table form below:

RISK MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES FOR THE RISK THAT A BUSINESS BECOMES CONTRACTUALLY BOUND TO TERMS UNINTENTIONALLY

|

RISK MANAGEMENT STRATEGY/STRATEGIES AVAILABLE

|

RISK MANAGEMENT STRATEGY/ STRATEGIES SELECTED AND REASONS FOR

SELECTION

|

|

|

|

|

Where a business’s marketing and promotional activities on the

Internet constitute making an “offer” rather than

an

“invitation to treat”

The risk control technique of scrutinising all marketing and promotional

activities on the Internet and ensuring that they cannot

reasonably be

understood as making “offers”, unless it is so intended by the

business.

Where a business’s purported withdrawal of an “offer” to

a customer is precluded because the business’s “offer”

has

been accepted by a customer

The risk control strategy of incorporating a contractual term that is based

on Article 15(a)(ii) of the UNCITRAL Model Law on Electronic Commerce,

such that acceptance of a business’s “offer” is deemed to take

place when the Internet communication accepting

the business’s offer is

retrieved by the business (regardless of whether the business has a designated

information system).

The risk control strategy of including, as a term of every transaction, a

term that reproduces or replicates a strategy used in relation

to contracts

effected through Electronic Data Interchange, such as clause 10.2 of the

Tradegate ECA Model EDI Trading Agreement.

This clause effectively specifies

that a transaction entered into by a business and a customer is governed by the

instantaneous rule.

Where during the course of negotiating the terms of an Internet transaction

a “battle of the forms” situation arises such

that the

customer’s terms override the business’s.

The risk control strategy of refusing to transact with a customer except

under the business’s terms.

The risk control strategy of preventing a customer from completing an order

(eg typing in or selecting order details from an order

form on a web page that

is then transmitted to the business) until the customer has signified acceptance

of the business’s

terms, the rejection of which result in the customer

being prevented from further progressing with the transaction.

In relation to business-to-business Internet commerce, where variations of

terms are more likely to be sought by customers and acceded

to by a business,

the risk control strategy of ensuring that a mechanism is put in place such that

if terms upon which the parties

agree to transact can and are varied by a

customer that subsequent to any variation accepted, a follow-up communication is

transmitted

to the customer confirming the varied term and reiterating all other

terms on which the business is prepared to transact.

Where the terms of the contract negotiated between the business and a

customer are altered by erroneous transmission

The risk control strategy of requiring all customers’ communications

with the business to be “signed” with a digital

signature.

The risk control strategy of incorporating as a contractual term with its

customers a term that reproduces or at least replicate the

effect of Article

13(5) of the UNCITRAL Model Law on Electronic Commerce. Article 13(5) of

the UNCITRAL Model Law on Electronic Commerce specifically precludes

reliance on an Internet communication received by a party where that party knew

or should have known that the

Internet communication was erroneous.

Where the business’s computer software used for conducting Internet

commerce is erroneously programmed or malfunctions so it

makes or accepts offers

in circumstances unauthorised by the business.

The risk transfer strategy of outsourcing the production of the software

used to conduct Internet commerce to a third party software

developer or to

purchase an off the shelf Internet commerce software package. Whilst this does

not remove the risk that a business

will be contractually bound to an Internet

transaction on terms to which it did not intend to be bound by, the business may

be able

to recover the losses it has incurred as a consequence of wrongly

programmed software from the third party developer, if the business

ensures that

a term of the software development or acquisition agreement provides for the

recovery of losses incurred by the business

as a consequence of an error or

malfunction in the Internet commerce software. Furthermore, the business will

need to ensure that

it does not contract out its rights to sue for negligence in

the event that the software is wrongly programmed.

The risk control strategy of incorporating as a contractual term with all

customers a term that reproduces or at least replicates

the effect of Article

13(5) of the UNCITRAL Model Law on Electronic Commerce. As noted earlier,

Article 13(5) precludes reliance by a party on an Internet communication

received by the party which the party

knew or ought to have known was

erroneous.

|

According to risk management principles this legal risk is the type of risk

that a business should retain and manage, as the consequence

of this risk is

medium, and the likelihood of this risk is unlikely. To retain this risk is also

consistent with the principle that

a business should only retain those risks

over which it has control.

In addition to retaining this risk, the business should take steps to

manage this legal risk. Based on an assessment that implementation

is not

expensive and that implementation will significantly minimise this legal risk, a

business should adopt all except two of the

risk management strategies put

forward. The two risk management strategies excepted are the use of digital

signatures and the outsourcing

of the production of the software used to conduct

Internet commerce to a third party. It is not, however, suggested that these two

risk management strategies are not cost effective. Rather, given that the

implementation of these two strategies will involve a cost

to the business, it

will be necessary for a business to weigh the cost of implementing these two

options against the benefits of

implementing these strategies before deciding

whether to adopt these risk management strategies.

|

The bundle of contractual risks referred to collectively here as the risk that a business through the course of its Internet commerce dealings becomes contractually bound to terms unintentionally is a moderate risk. According to risk management principles this contractual risk is the type of risk that can be retained by a business. However, in addition, this risk should be managed. This contractual risk can be managed through the implementation of a number of risk management strategies which have been set out in this article. Which strategies should be implemented by a business depends on a large degree to the circumstances of a particular business. Only two risk management strategies are likely to cause considerable expense to a business, that is the use of digital signatures and the outsourcing to a third party of the production of the software used to conduct Internet commerce. At a theoretical level this article demonstrates that it is useful to use risk management methodology in the context of legal risk. Applying risk management methodology is arguably superior to providing conventional legal advice as the methodology automatically involves a systematic approach to analysing legal risk and evaluating appropriate risk management strategies. It is hoped that legal practitioners will use risk management methodology when providing legal advice.

* Dr Kate Reid is presently working as in-house counsel for Aspect Internet Limited, an internet company based in London.

[1} Adapted from Standards Australia/Standards New Zealand Joint Technical Committee on Risk Management, “A Basic Introduction to Managing Risk using the Australian and New Zealand Risk Management Standard - AS/NZS 4360: 1999”, Master Draft as at 4/1/99 p. 25.

[2] Adapted from appendix D, AS/NZS 4360- 1995, Risk Management, Standards Australia, Homebush NSW, 1995.

[3] Adapted from Standards Australia/Standards New Zealand Joint Technical Committee on Risk Management, “A Basic Introduction to Managing Risk using the Australian and New Zealand Risk Management Standard - AS/NZS 4360: 1999”, Master Draft as at 4/1/99 p 26.

[4] Carlill v. Carbolic Smoke Ball Co, [1893] 2 QB 484.

[5] JG Starke QC, NC Seddon, MP Ellinghaus, Cheshire and Fifoot’s Law of Contract, 6th Australian Edition, Butterworths, Sydney 1992, Ch 1, p 54, para 109.

[6] Starke, Seddon, Ellinghaus, para 109.

[7] See, for example, ACT: Sale of Goods (Vienna Convention) Act 1987; NSW: Sale of Goods (Vienna Convention) Act 1986; Vic: Sale of Goods (Vienna Convention) Act 1987; WA: Sale of Goods (Vienna Convention) Act 1986; Qld: Sale of Goods (Vienna Convention) Act 1986; Tas: Sale of Goods (Vienna Convention) Act 1987; SA: Sale of Goods (Vienna Convention) Act 1986; NT: Sale of Goods (Vienna Convention) Act 1987.

[8] Under the postal rule the posting of an acceptance constitutes an effective acceptance even if the message never arrives: Household Fire & Carriage Accident Insurance Co Ltd v. Grant [1879] UKLawRpExch 37; (1879) 4 Ex D 216; Georgoulis v Mandelinic [1984] 1 NSWLR 612 at 616.

[9] Graham JH Smith et al, Internet Law and Regulation, A Specially Commissioned Report, FT Law & Tax, London, 1996, Ch 8, p 99, para 8.2.2.

[10] Entores Ltd v Miles Far East Corp [1955] EWCA Civ 3; [1955] 2 QB 327; Brinkibon Ltd v Stahag Stahl Und Stahlwarenhandelsgesellschaft Mbh [1983] 2 AC 34; Express Airways v. Port Augusta Air Services [1980] Qd R 543.

[11] Brinkibon Ltd v. Stahag Stahl Und Stahlwarenhandelsgesellschaft Mbh [1983] 2 AC 34

[12] Reese Bros v Hamon-Sobelco (1988) 5 BPR [97325], Court of Appeal (NSW) and Wogen Resources Ltd v Just Australia China Holdings Ltd and Anor, 22 November 1994, Supreme Court of Victoria, Commercial Division

[13] See for example, Paul Fasciano, “Note: Internet Electronic Mail: A Last Bastion for the Mailbox Rule”, 25 Hoftstra Law Review 971 (downloaded from Lexis-Nexis). See also Law Commission, “Electronic Commerce Part One- A guide for the Legal and Business Community”, NZLC R50, October 1998, Wellington, New Zealand, p 28 para 71 in which it was advocated that the postal rule apply to acceptances made by e-mail where the e-mail is sent through an Internet Service Provider who receives the e-mail on behalf of the recipient but that the instantaneous rule apply where the recipient has a direct and immediate access to e-mail.

[14] JG Starke QC, NC Seddon, MP Ellinghaus, Cheshire and Fifoot’s Law of Contract, 6th Australian Edition, Butterworths, Sydney 1992, Ch 1, pp 82-83, para 140.

[15] Interestingly, the Law Commission in, “Electronic Commerce Part One- A guide for the Legal and Business Community”, NZLC R50, October 1998, Wellington, New Zealand, p 28 para 71 advocated that the instantaneous rule apply where the recipient has a direct and immediate access to e-mail but where the recipient has access to e-mail through an Internet service provider then the postal rule should apply because “…those using an ISP may only communicate as quickly as their telephone access, service provider and personal inclination dictate.”

[16] Fasciano, p 1001.

[17] Brinkibon Ltd v. Stahag Stahl Und Stahlwarenhandelsgesellschaft Mbh [1983] 2 AC 34 at 42.

[18] NM Superannuation Pty Ltd v Baker [1992] 7 ACSR 105 at 114-115.

[19] See, for example, ACT: Sale of Goods (Vienna Convention) Act 1987; NSW: Sale of Goods (Vienna Convention) Act 1986; Vic: Sale of Goods (Vienna Convention) Act 1987; WA: Sale of Goods (Vienna Convention) Act 1986; Qld: Sale of Goods (Vienna Convention) Act 1986; Tas: Sale of Goods (Vienna Convention) Act 1987; SA: Sale of Goods (Vienna Convention) Act 1986; NT: Sale of Goods (Vienna Convention) Act 1987.

[20] Law Commission, "Electronic Commerce Part One- A guide for the Legal and Business Community", NZLC R50, October 1998, Wellington, New Zealand, p 28 para 72.

[21] See for example, Hyde v Wrench [1840] EngR 1054; (1840) 3 Beav 334.

[22] See for example, Brogden v Metropolitan Railway Co (1877) 2 App Cas 666.

[23] Cavallari v Premier Refrigeration Co Pty Ltd [1952] HCA 26; (1952) 85 CLR 20.

[24] Article 2 of the United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods.

[25] Article 19(3), United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods.

[26] Article 19(2), United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods.

[27] Article 19(2), United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods.

[28] JG Starke QC, NC Seddon, MP Ellinghaus, Cheshire and Fifoot’s Law of Contract, 6th Australian Edition, Butterworths, Sydney 1992, Ch 6, p 313, para 645.

[29] Law Commission, “Electronic Commerce Part One - A guide for the Legal and Business Community”, NZLC R50, October 1998, Wellington, New Zealand, pp 22-23, para 58.

[30] Robinson v Harman [1848] EngR 135; (1848) 154 ER 363 per Parke B.

[31] Robinson v Harman [1848] EngR 135; (1848) 154 ER 363 per Parke B.

[32] UNCITRAL Model Law on Electronic Commerce, Excerpt from the Report of the United Nations Commission on International Trade law on the work of its twenty-ninth session (28 May-14 June 1996) General Assembly, Fifty-first Session, Supplement No. 17 (A/51/17), http://www.un.or.at/uncitral/texts/electcom/ml-ec.htm#top.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/JlLawInfoSci/2000/11.html